- Department of Curriculum and Instruction, College of Education, Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia

This research investigates the English as a foreign language (EFL) teachers’ perception of the pros and cons of synchronous and asynchronous online learning for EFL students in Saudi Arabia. 121 EFL teachers from public schools in different regions participated in this study. A questionnaire has been used to collect this study’s main data and distributed it online to all EFL teachers in Saudi Arabia. After the statistical analysis of data, the study’s main findings revealed that the advantages of synchronous learning are helping learners reduce space barriers and saving time for learners. However, the main disadvantages of synchronous learning are the disruption of the internet: slow speed, the miscommunication of learners and getting bored through learning. The main findings for the advantages of asynchronous learning are the chances for learners to replay the lesson many times, the opportunities for learners to have more time for thinking, and the opportunities for learners to enhance autonomy and self-regulated learning. However, the disadvantages perceived by the participants were that asynchronous learning requires more responsibilities from learners in self-controlling, self-motivation, and autonomous learning skills. This study is one of the few studies investigating and comparing EFL teachers’ perceptions of synchronous and asynchronous online learning. Therefore, this research could serve the Ministry of Education by exploring the challenges that instructors face in teaching and highlighting the advantages of online teaching to increase awareness among Saudi teachers of its essential role in EFL learning.

1 Introduction

In today’s world, online learning has gained significant importance as a viable alternative to traditional in-person learning. Researchers have conducted numerous previous studies to examine the effectiveness of online learning in both modes, particularly in terms of learners’ achievement and performance during the learning process. Conflicting results in the literature appeared for the studies that compare online learning and traditional learning (Martin et al., 2021). Lim et al. (2022) have reported that many previous studies claimed the positive effects of online learning, while others claimed the negative effects of online mode. However, many studies reported there were no negative effects between traditional and online learning (Zeng and Luo, 2023; Lim et al., 2022).

In the general context, Zeng and Luo (2023) conducted a meta-analysis study to explore and compare the effect of synchronous and asynchronous modes of online learning. They performed the meta-analysis across different disciplines, and they concluded that synchronous learning has more impact on learners’ knowledge and understanding than synchronous online learning. Furthermore, they reported that asynchronous learning could have a greater impact on mathematics learning (Zeng and Luo, 2023). Zeng and Luo (2023) recommended using online learning since it facilitates learners’ learning by using different resources that suit their needs and abilities. Consequently, the results of the meta-analysis reported that asynchronous learning is more effective than synchronous learning.

Furthermore, Zhang et al. (2020) conducted a study investigating the effect of synchronous and asynchronous learning. Zhang et al. (2020) collected data from a community of inquiry, involving 170 learners. They concluded that there are significant differences between both modes of online learning in three factors: social presence and the presence of cognitive skills. In synchronous learning than in asynchronous learning. They reported that learners exhibited a lower preference for interaction in online courses, but a higher preference for completing assignments. Learners perceived that they achieved more without class interaction.

García-Machado et al. (2024) examined the students’ intrinsic motivation and compared it to their engagement and achievement. They sought to determine the impact of providing support on learners’ engagement in online learning. They conducted analyses between Mexico and Romania, concluding that there were no significant differences regarding gender and that providing support to learners did not affect their engagement and achievement. However, García-Machado et al. (2024) recommended the use of technology to support learners’ learning and meet all their needs.

In Saudi Arabia, COVID-19 in March 2020 prompted the Ministry of Education to transition to online schooling to protect public health and manage the spread of the virus (Almusharraf and Khahro, 2020). Online learning has presented several challenges due to inadequate preparation of instructors and students for these conditions (Clarin and Baluyos, 2022; Sithole et al., 2019; Smith, 2023). According to Alghamdi and Alghamdi (2021), the Ministry of Education assisted all students and instructors in managing the difficulties associated with online learning. The Saudi Ministry of Education offers both synchronous and asynchronous online learning to all Saudi students in public schools (Alghamdi and Alghamdi, 2021).

Nevertheless, during the penultimate period, an attempt was made to implement asynchronous modes of instruction for most course modules, as many educational sectors were unprepared for the synchronous electronic program that facilitates simultaneous meetings between instructors and students (Kerrigan and Andres, 2022). As a result, recordings and file transfers occur through a formal educational channel known as “Ain” (Alyousef, 2023). The Ministry of Education made efforts a few years before the pandemic to establish this channel as a supplementary education resource for students. Thus, students who require further explanation of particular teachings in any course could select the appropriate course and tune into these channels (Al-Harbi, 2022).

There are 20 channels in Ain, each offering a variety of distinct activities. Aziz Ansari et al. (2021) have mentioned that male and female educators deliver these courses and cater to kids at all levels: elementary, middle, and high school, covering all disciplines. They are provided to enrich students’ understanding of all subjects and promote self-directed learning. The primary objectives of providing these channels are to facilitate access to necessary information for learners, give access to knowledge at any time, transcend geographical limitations, and alleviate academic strain on students. Users may access these channels through smartphones and tablets (Aziz Ansari et al., 2021). Therefore, before COVID-19, Saudi students were used to asynchronous instruction. However, their readiness for synchronous learning during COVID-19 was inadequate. The Ministry of Education funded the development of the team’s application during the pandemic to facilitate synchronous learning and class completion for students and instructors (Almusharraf and Khahro, 2020).

The Saudi Ministry of Education strives to improve by including online learning as additional education for all courses. Education in Saudi Arabia has recently focused on increasing awareness of the significance of online learning. Adopting online learning as a fundamental supplementary learning option for all Saudi students is one of the most important aspects of the 2030 Saudi Vision, a future strategy for achieving the vision (Binyamin et al., 2019). Nevertheless, online learning in Saudi Arabia still needs to overcome hurdles and complications in English courses in schools (Al-Seghayer, 2019; Al-Harbi, 2022; Alzain, 2022). Therefore, it is crucial to carry out research that investigates the advantages and challenges of both synchronous and asynchronous online learning methods.

Previous studies of online learning in Saudi Arabia have investigated learners’ perceptions of the benefits and issues they encounter in Higher Education (Pusuluri et al., 2017; Al-Nofaie, 2020; Bin Dahmash, 2020, 2021; Albogami, 2022). Pusuluri et al. (2017) investigated learners’ perceptions of using online learning through the blackboard at Aljouf University. The result of the study reported that online learning provides them with various resources, creating a motivational environment in learning EFL. Bin Dahmash (2020) conducted a qualitative study to explore the King Saud University learners’ perceptions of the advantages and disadvantages of blended learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the results explored that blended learning helped enhance learners’ writing skills. However, they experienced some adverse effects because of technical issues.

Al-Nofaie (2020) also investigated Saudi university students’ perception of online learning through the blackboard during COVID-19. The main result revealed that learners prefer asynchronous learning. However, they prefer face-to-face learning over online learning. Further, Bin Dahmash (2021) explored King Saud University students’ perceptions of the benefits of synchronous and asynchronous EFL learning. She also investigated the practices that emerged from online learning. The main results were that synchronous learning could help learners communicate and receive feedback. Also, the main findings for asynchronous learning are that it could help learners learn in a relaxed environment and help reduce the difficulties for synchronous learners.

Another study by Albogami (2022) explored the EFL learners’ perspective on online learning at King Saudi University. The researcher investigated the effect of online learning on EFL learners’ enhancement of the four skills of language. The main result revealed some challenges in online learning perceived by learners; however, they prefer online learning over face-to-face learning. Further, Hashmi et al. (2021) investigated the issues EFL instructors face in Higher Education. The main results perceived by EFL instructors are positive regarding online learning; however, they reported difficulties for learners in using online learning since they need training to improve their learning. Further, the result reported that the assessment during online learning was challenging since many negative factors could affect that. The main issue is the perception of cheating in quizzes and exams. Electronic tools could help reveal the plagiarism percentage in submitting projects, tasks, and assignments, but the online exam could be critical now.

Previous researchers (Al-Nofaie, 2020; Bin Dahmash, 2020; Al-Jarf, 2020) found that although online learning has many advantages for EFL learners, face-to-face learning could help them enhance their cooperative learning in English classes. Further, Bin Dahmash (2020) found that learners prefer face-to-face learning since online learning lacks eye contact, which cannot motivate learners to interact more during their learning.

Most previous Saudi studies have investigated the benefits and difficulties of synchronous online learning in higher education and learners’ perceptions of online learning in university education. Thus, this research sheds light on the pros and cons of both online learning modes, synchronous and asynchronous, in Saudi School Education. This research aims to address the gap in EFL literature by examining teachers’ opinions of synchronous and asynchronous online learning and comparing the advantages and disadvantages of each mode.

This research is significant since it could contribute to the Saudi EFL literature by exploring the teachers’ experiences and perceptions of the most common advantages and disadvantages of synchronous and asynchronous online learning. Exploring EFL Saudi teachers’ perceptions could raise awareness of the benefits of both modes of online learning and present an overview for the Saudi Ministry of Education to suggest solutions for the reported challenges. Furthermore, this study could help Saudi policymakers to suggest regulations based on the advantages and disadvantages of designing an effective synchronous and asynchronous environment. Also, it could help the Ministry of education do training for EFL teachers and develop the online EFL environment.

Since EFL teachers are central to enhancing and developing Learning EFL in Saudi Arabia, their perspectives are essential to help enhance EFL online learning. EFL teachers must teach English and plan lessons for students learning in online classes, so they are suitable people to determine the pros and cons of synchronous and asynchronous online learning. Therefore, the researcher focused on answering the following questions.

Research questions:

1- What are the Saudi EFL teachers’ perceptions of the Pros and Cons of synchronous and asynchronous learning?

2- How do Saudi EFL teachers’ perceptions compare the Pros and Cons of synchronous and asynchronous learning?

Research hypothesis:

1- Synchronous and asynchronous learning has many Pros and Cons from the teachers’ perspectives.

2- Asynchronous learning will have more Pros than synchronous learning from the teachers’ perspectives.

2 Literature review

2.1 EFL in Saudi Arabia context

English is regarded as a foreign language in Saudi Arabia, where Arabic is the official and working language in most sectors. EFL instruction and research in Saudi Arabia are undergoing numerous phases of development and improvement. This is due to the English language’s crucial contribution to developing various national sectors. People in Saudi Arabia need to be able to speak English to work with foreigners in many fields. The Saudi Ministry of Education is trying to improve EFL instruction and learning (Althobaiti, 2020). Al-Tamimi (2019) criticized the deficiency in teaching EFL due to learners’ lack of exposure and time for interaction. To improve EFL use and practice, teachers need to create suitable environments that encourage interaction (Al-Tamimi, 2019). Online EFL classes, both synchronous and asynchronous, can provide flexibility in time and place, allowing learners to practice the language in an unthreatening environment.

Overcrowded classrooms, which prevent instructors from allocating adequate time for students to exercise their communication skills, impede learners’ ability to utilize and refine EFL communication. Due to the typically large number of students in EFL classrooms, online courses may be more effective than in-person classes, where obstacles such as limited time for practice, inadequate student-to-teacher ratios, and language deficiencies may be mitigated (Bahanshal, 2013; Sriwichai, 2020). In an asynchronous online lecture, students do not need to convene simultaneously. They can access the classes at their convenience, allowing them to locate appropriate activities that improve their communication abilities (Alshumaimeri and Alhumud, 2021). On the other hand, Students in synchronous online classrooms are often grouped appropriately to facilitate increased engagement in EFL practice (Cheung, 2021).

According to Alzobiani (2020), teachers’ dominance in the classroom and the expectation that students heed their counsel constitute another significant factor in the deficiency of EFL in Saudi Arabia (Alzobiani, 2020). As a result, the teacher-student relationship in Saudi EFL is formal, which may hinder opportunities for greater interaction and communication. In Saudi Arabia, the average EFL classroom focuses more on the instructor than the students. EFL instructors must adhere to the textbook’s content and discuss every aspect, given that it encompasses all four English language skills (Ding, 2021). Laachir et al. (2022) mentioned that online EFL classes could help solve the problem of the EFL teacher being too dominant since the students are the ones who need to be in these classes. In asynchronous online courses, the learners have complete autonomy to fulfill all assigned tasks. Therefore, online courses may foster a sense of accountability among students regarding their education, as the instructor’s presence is absent (Laachir et al., 2022). As a result, it is critical to conduct research examining the benefits and drawbacks of online learning in the context of EFL to assist Saudi institutions in improving online language instruction and learning.

2.2 Synchronous online learning in EFL

Synchronous learning involves students interacting with their professors using online platforms, systems, or technical tools. Students must convene at a designated time for the instructor to provide the lesson, and students are expected to engage and collaborate with the teachers. Synchronous online learning often utilizes videoconferences, meeting software, and a learning system to provide virtual interactions between professors and students via technology. In this kind of learning, students are encouraged to engage rather than passively receive information actively. They might interact directly in a traditional classroom setting, and professors could use targeted tactics to facilitate this.

Synchronous devices are well-suited for delivering up-to-the-minute news and time-critical information, alleviating concerns about the automated aspect of technology-driven education. They create an environment for learning, promoting unity and curiosity about various ideas. Synchronous e-learning minimizes disparities and fosters fairness by mitigating power dynamics and individual traits that may impact group interactions (Riwayatiningsih and Sulistyani, 2020). Synchronous e-learning technologies include features like whiteboarding and mark-up tools that facilitate rapid and efficient learning (Mohammadi, 2023).

Previous research investigated the advantages of synchronous learning, revealing its positive impact on communication abilities, particularly speaking skills (Assaneo et al., 2019; Dao et al., 2023; Tarazi and Ortega-Martín, 2023). Vurdien (2019) research investigated the potential of videoconferencing to improve listening and speaking abilities in EFL learners. He conducted his research on thirty EFL students. They have been split into two groups: one group is having their lesson in person on-site, while the other is having their lesson online via videoconference. Research revealed that online learning via videoconference leads to better course performance than on-site learners. Online learning is more convenient than on-site learning because students may boost their confidence and improve their communication skills by engaging in written discussions with others in chat forums (Vurdien, 2019).

However, one major drawback of synchronous learning is internet disruption, especially for those residing in remote regions. This might disrupt the learning process for both instructors and students. To address these challenges, EFL instructors can use synchronous and asynchronous online learning methods (Sari and Wahyudin, 2023). Students who experience detachment might benefit from asynchronous learning resources that have been pre-recorded. Another drawback is that students may be in an online setting at home with their family, potentially impacting their focus on the course, especially if they need a dedicated research space. To deal with this challenge, parents should understand the value of online learning and encourage their children to work quietly and in suitable private spaces (Feliz et al., 2022).

2.3 Asynchronous online learning in EFL

Asynchronous online learning entails providing students access to the academic platform’s stored support materials, including classes, videos, presentations, and activities, at their convenience throughout the day (Song and Kim, 2021). In asynchronous learning, students may access recorded videos, download documents and materials, and communicate with their instructors through the academic platform anytime, providing greater flexibility in their learning if they encounter technological or internet difficulties (Dada et al., 2019). Furthermore, presentations and materials will be made available online in asynchronous learning. It is more similar to self-regulated learning, a dynamic process that assists learners in identifying goals, working toward them, and controlling the learning process. Asynchronous learning requires learners to manage the materials effectively, demonstrate awareness of their learning requirements, and inquire further as necessary (Alhazbi and Hasan, 2021).

Learners may find asynchronous learning more beneficial if the learning environment is well-designed. Watkins and Portsmore (2022) discovered that when learning asynchronously, students must sense their presence and be assisted in participating (Watkins and Portsmore, 2022). Instructors are advised to create conducive environments in asynchronous learning environments that encourage learners to interact socially and improve their emotions (Zhang and Yu, 2023). Several researchers proposed that for students to envision the educational environment when they are learning asynchronously, they must recognize that they must act as learners and that the instructor is the one who explains the lesson. Effective learners must be proficient with technologies and navigate course materials (Alhazbi and Hasan, 2021; Gambo and Shakir, 2021; Watkins and Portsmore, 2022). Moreover, according to Stewart (2020), in asynchronous learning, it is necessary to find a convenient time for students to complete the online lessons, given that they must schedule them around their daily lives (Stewart, 2020).

Asynchronous learning did, nevertheless, have several prevalent disadvantages. Learners may require clarification for certain tasks when engaging in asynchronous research due to students’ comprehension variations (Hariadi and Simanjuntak, 2020). According to Riwayatiningsih and Sulistyani (2020), in EFL, students have different levels of ability, so teachers need to use other methods to help all of them understand the task. However, in asynchronous learning, they can only do that if they record the lessons more than once and use different methods each time, which might not be possible in some situations (Riwayatiningsih and Sulistyani, 2020). Additionally, another disadvantage is that EFL instructors cannot oversee students’ progress, which would make evaluations even more challenging. Therefore, asynchronous learning may resemble inactive learning for learners due to the unidirectional nature of the interaction (Ariyanti, 2020; Putri, 2021; Rabbianty and Wafi, 2021).

3 Methodology

3.1 Questionnaire development

The researcher used several literature to create a questionnaire that asked Saudi EFL teachers to rate the pros and cons of synchronous and asynchronous EFL learning (Alibakhshi and Mohammadi, 2016; Chen and You, 2007; Lowenthal et al., 2017; Perveen, 2016; Zhang and Wu, 2022). After comprehensively reviewing the pertinent literature, the researcher formulated each questionnaire item. Drawing from her experience, the researcher identified and documented the potential benefits and drawbacks of synchronous online learning. She then composed components for asynchronous learning that apply to the learning mode within the Saudi EFL classroom context. The researcher has devised 40 items, ten for each variable, to provide an equitable analysis of the benefits and drawbacks of both modalities.

The questionnaire consists of two sections. The first section is related to demographics and includes questions regarding gender, qualification, experience, and area of residence. The second section consists of questions regarding the analysis of the research questions. The second section is divided into four sub-themes that are advantages of synchronous learning compared to asynchronous learning, Disadvantages of synchronous learning compared with asynchronous learning, Advantages of asynchronous compared with synchronous, and Disadvantages of asynchronous compared with synchronous. Each of these subthemes comprised ten interconnected components. The participants were instructed to use the Likert scale to indicate their agreement with each item. Furthermore, the researcher reviews the questionnaire with some expert academic faculty members in the field of the English language.

3.2 Questionnaire reliability

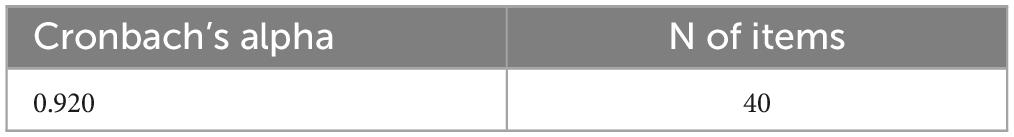

The Alpha Cronbach value attained was 0.920, as illustrated in Table 1. The Cronbach alpha value indicates the reliability of the item under consideration in the questionnaire. A higher value of internal consistency indicators signifies enhanced stability. Internal consistency reliability assesses the degree of interdependence among the items (Edwards et al., 2021). The table’s N of Items column indicates the total number of items comprising the scale, which is 40.

3.3 Participants

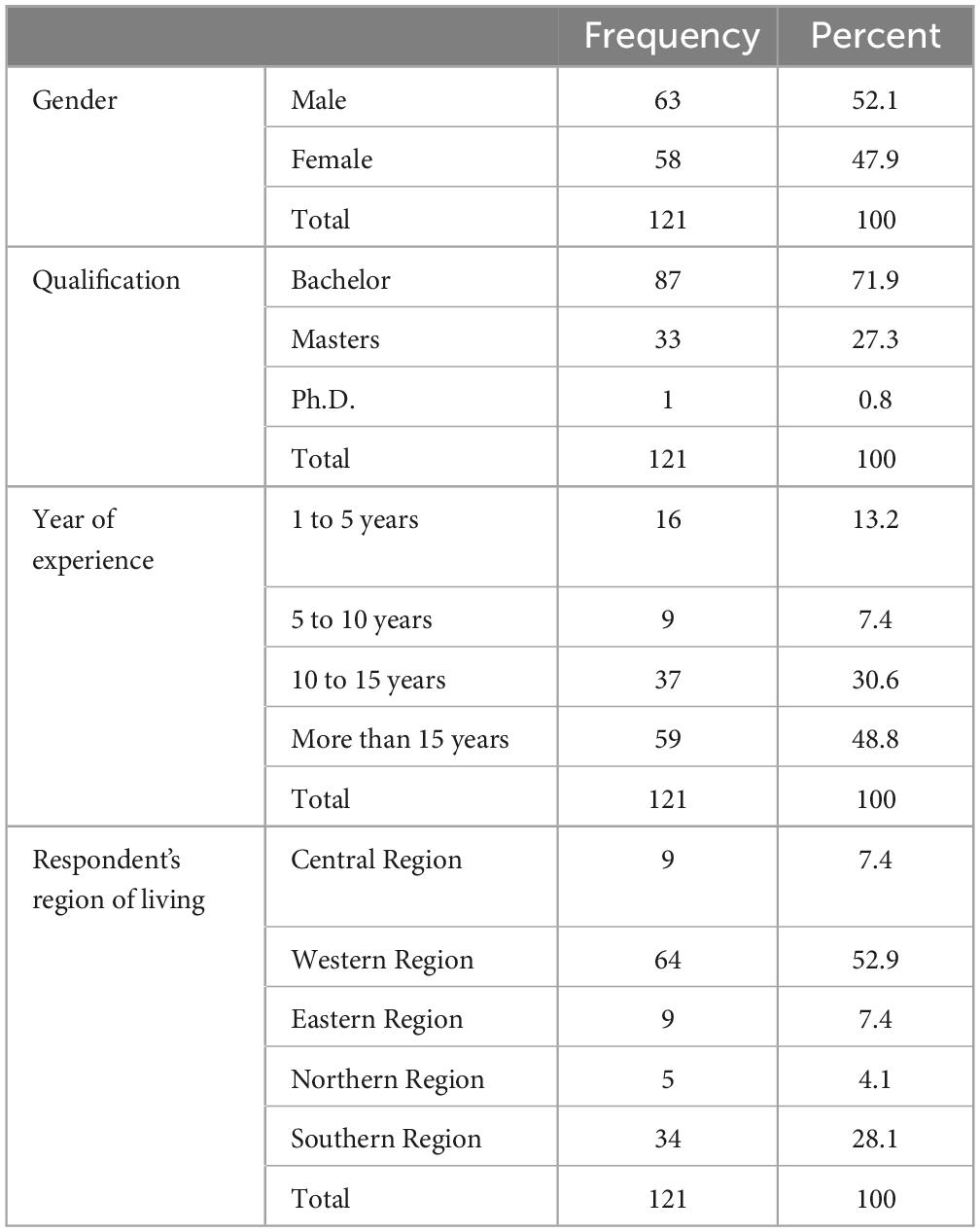

The number of participating EFL Saudi teachers was 121, male and female, from different regions in Saudi Arabia. The following table will clarify the study participants.

3.4 Demographic analysis of the participated teachers’ in this study

Table 2, as given above, shows the demographic stats of this research. Based on the statistics, the sample consisted of 52.1% male respondents and 47.9% female respondents. This implies that the distribution of genders among the participants was relatively balanced. As per qualification statistics, Most of the EFL teachers in the group (71.9% of those who responded) had at least a bachelor’s degree; only 0.8% had a Ph.D. The remaining 27.3% had a master’s degree. This discovery indicates that many respondents held higher degrees and professional certifications relevant to education.

In addition, according to demographic data, 7.4% of respondents indicated they had between five and ten years of experience, whereas 13.2% of respondents claimed to have between one and five years of experience. The proportion of respondents with 10 to 15 years of experience was substantial, at 30.6%. The majority of respondents, 48.8%, indicated they possessed over 15 years of experience.

The demographic analysis shows that 52.9% of the largest respondents lived in the Western Region. With 28.1% of participants, the Southern Region was the second most well-represented region. 7.4% of the respondents came from the Central and Eastern Regions, which had comparable percentages. Only 4.1% of participants were from the Northern Region, with the least participation overall. These results suggest that EFL teachers from different areas of Saudi Arabia were included in the research, with a clear preference for the Western and Southern regions. The geographical diversity enhances the complexity and generalizability of the research’s findings in the Saudi EFL setting.

3.5 Data collection process

The researcher got approval to conduct the research from the ethical committee at Umm AL-Qura University. The data collection procedure commenced in January 2023 and continued through February 2023 after the research confirmed the questionnaire’s suitability and dependability for gathering information for this research. People who teach EFL in Saudi schools were given the questionnaire. The questionnaire was sent to the instructors through social media, e.g., WhatsApp. The major requirement for EFL instructors to participate in the research is that they teach English in public schools. The total number of EFL instructors who participated in this research comprised 121 participants. All the individuals enrolled in the study are Saudi educators who instruct English language courses in public institutions.

3.6 Data analysis

The questionnaire data were subjected to statistical analysis by the researcher. The software primarily utilized was Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) 22.0. The researcher employed the Descriptive Statistics program (frequencies, means, percentages, and standard deviations) to elucidate the instructors’ online learning experiences in synchronous and asynchronous modes.

4 Findings

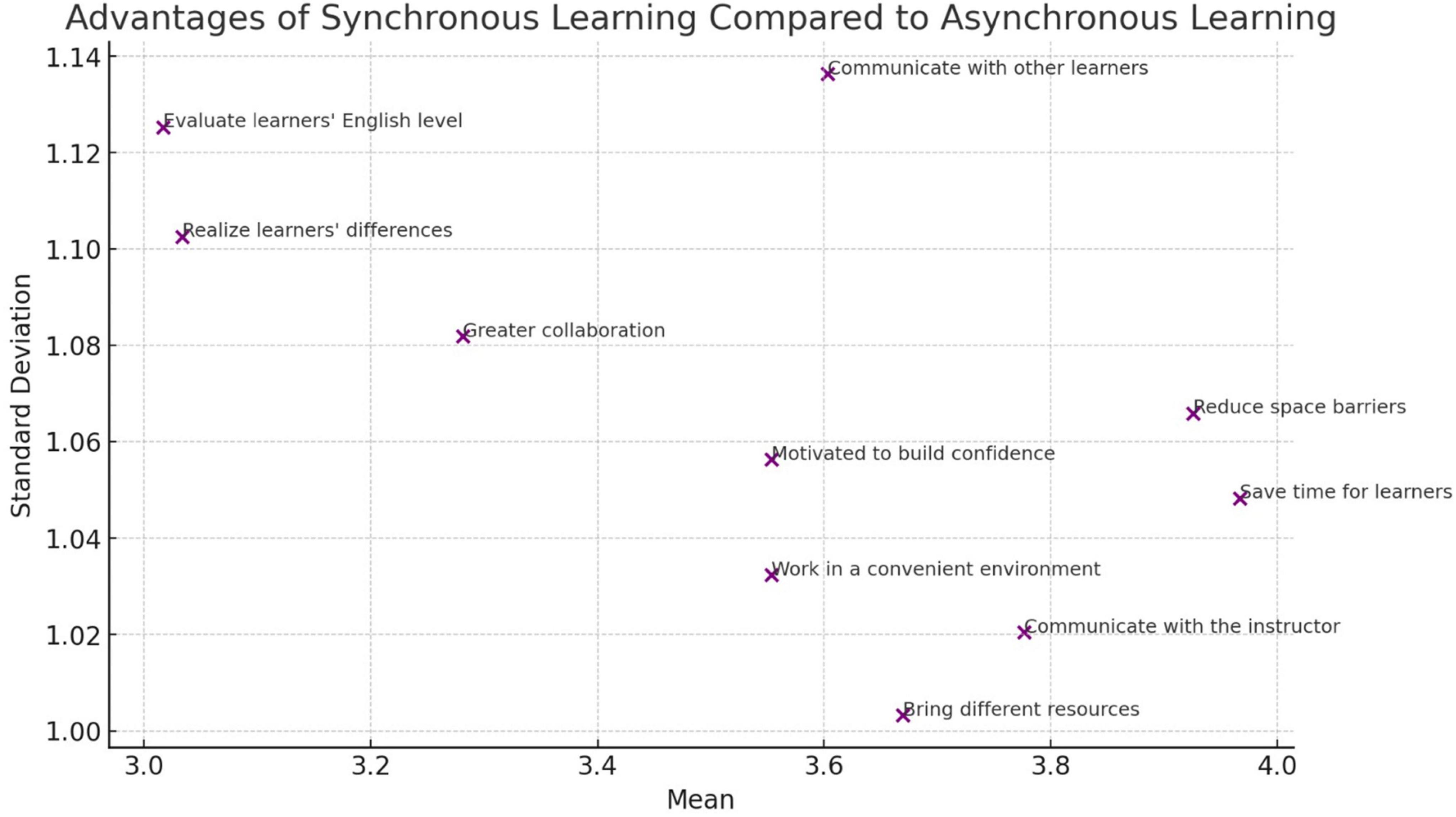

4.1 Advantages of synchronous learning compared to asynchronous learning

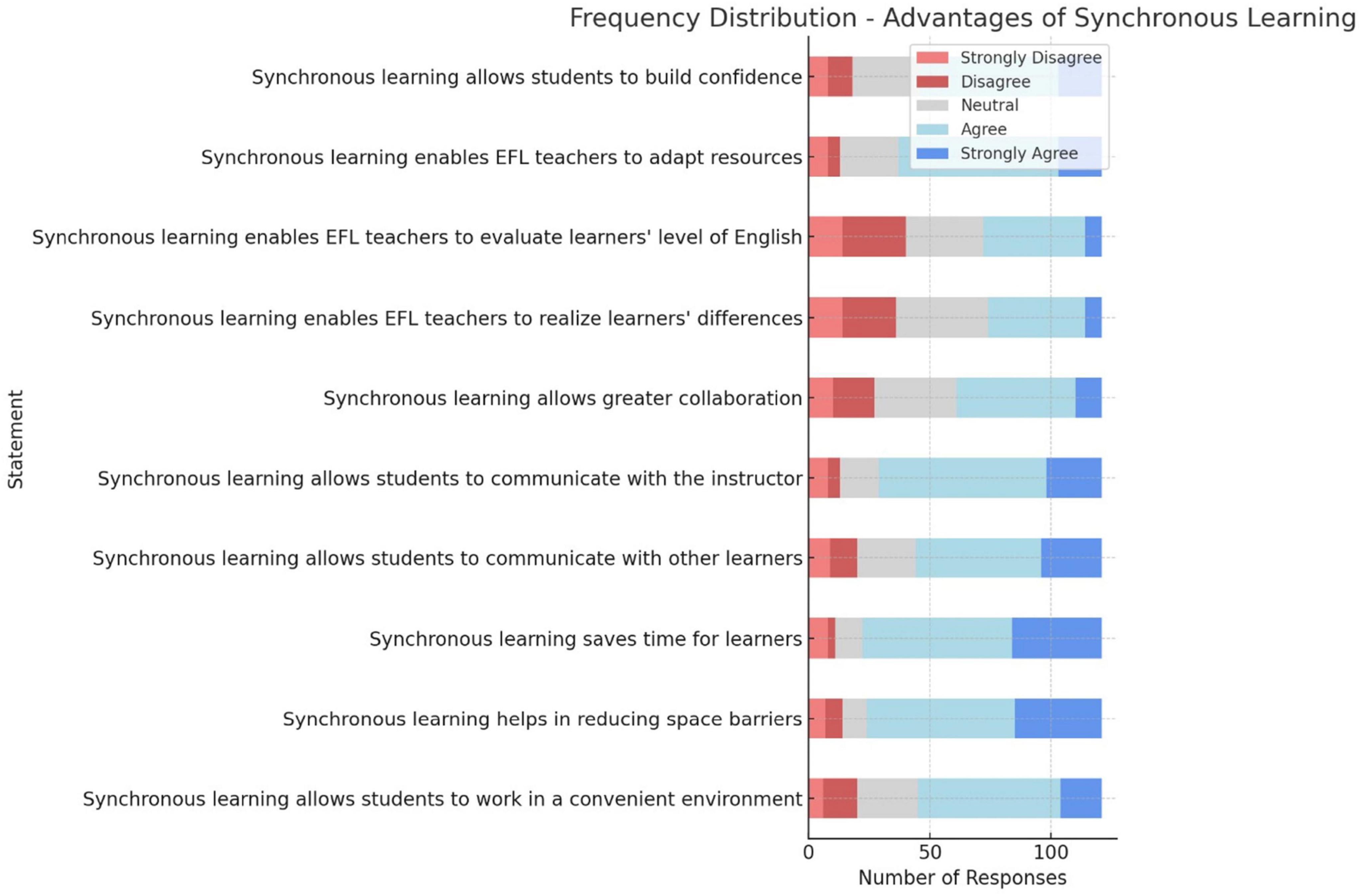

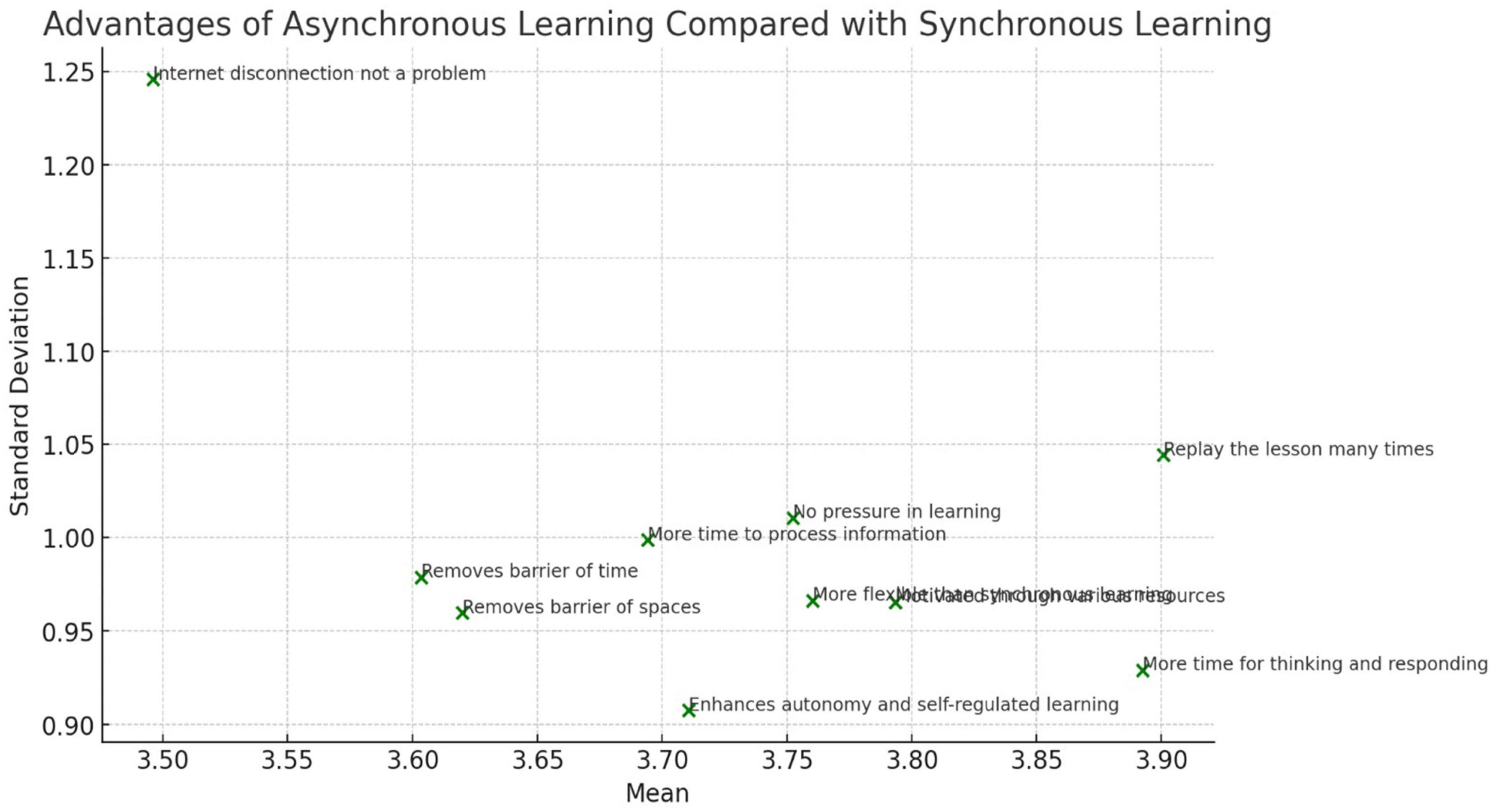

The comparative descriptive statistics of the benefits of synchronous learning over asynchronous learning are shown in Figures 1, 2. The standard deviation tells us about the variety or dispersion of the replies, while the mean values provide the average rating each respondent gave each item. The results show that respondents’ perceptions of the benefits of synchronous learning have high levels of agreement. The statement “Synchronous learning helps in saving time for learners since learners could log on at home or outside” had the highest mean score (mean = 3.9669), indicating that participants were aware of the convenience of accessing educational resources from multiple locations. Similar to the previous statement, “Synchronous learning allows students to communicate with the instructor” (mean = 3.7769) obtained a comparatively high mean score, demonstrating the value recognized in direct communication with the instructor.

Figure 1. Descriptive statistics of advantages of synchronous learning compared to asynchronous learning.

Other questions with moderate mean scores, like “Synchronous learning allows greater collaboration more than asynchronous mode” (mean = 3.2810) and “Synchronous learning enables EFL teachers to bring different resources to adapt students’ needs” (mean = 3.6694), suggested that respondents understood how collaborative and resourceful synchronous learning is. Lastly, the fact items like “Synchronous learning enables EFL teachers to realize the learners’ differences” (mean = 3.0331) and “Synchronous learning enables EFL teachers to evaluate learners’ level of English” (mean = 3.0165) received lower mean scores suggest that respondents perceived these benefits to a lesser extent.

4.2 Disadvantages of synchronous learning compared with asynchronous learning

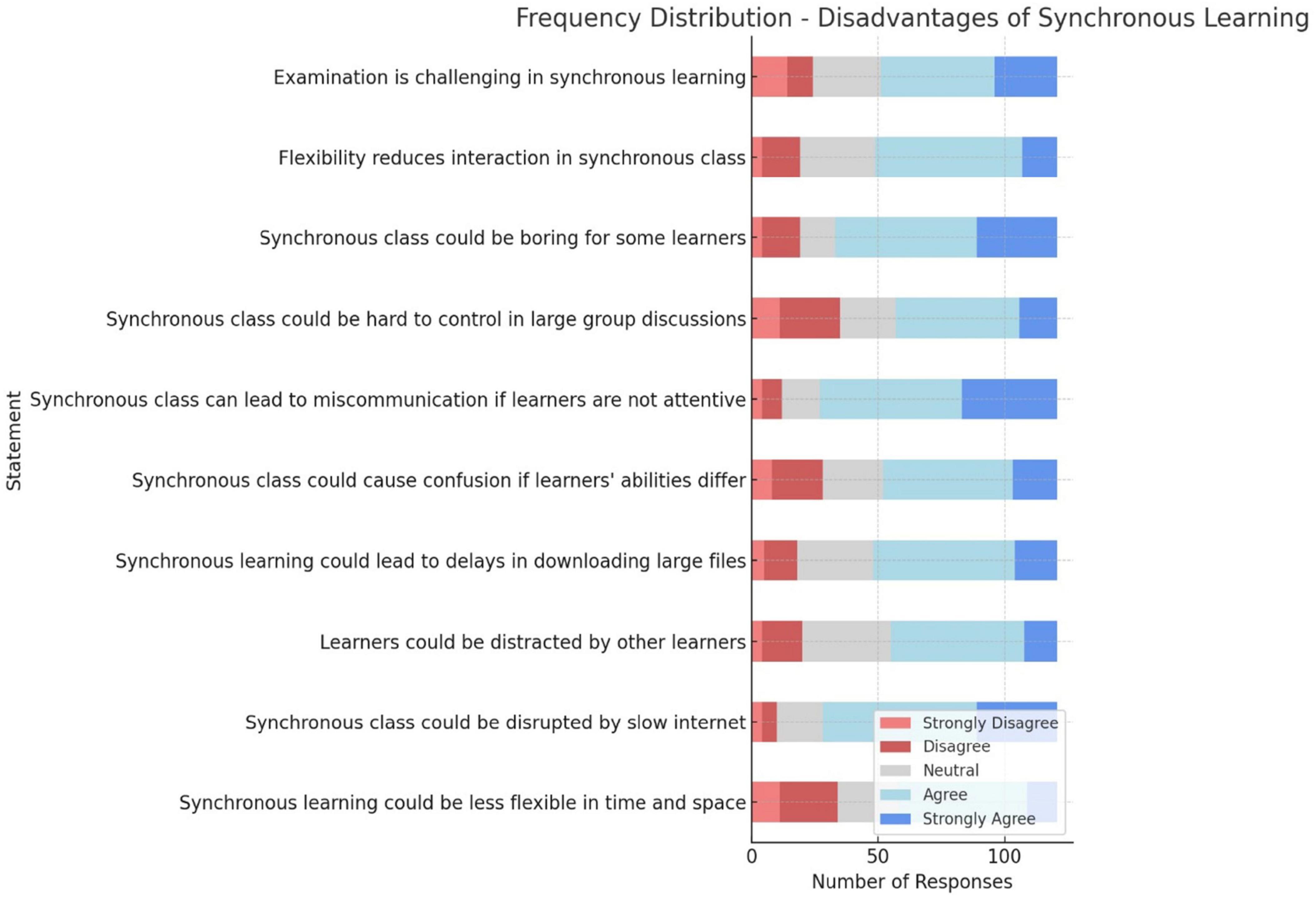

The descriptive statistics of synchronous learning’s disadvantages compared to asynchronous learning are shown in Figures 3, 4. The standard deviation measures the variability or dispersion of the replies, whereas the mean values provide the average ratings given by the respondents for each item. The results show that respondents’ levels of agreement with the listed drawbacks of synchronous learning were moderate. The statement “The slow speed of the internet can disrupt synchronous class” had the highest mean score (mean = 3.9174), indicating that participants were aware of the potential technological difficulties that could impair the smooth operation of synchronous classes.

Figure 3. Descriptive statistics of disadvantages of synchronous learning compared with asynchronous learning.

The statements “Synchronous class could lead to miscommunication if learners are not paying attention” (mean = 3.9587) and “Synchronous class could be boring for some learners since it requires more attention from them” (mean = 3.8017) both obtained relatively high mean scores. These findings show that participants recognized the possibility of misunderstandings and the necessity of paying closer attention during synchronous learning sessions.

Additionally, moderate mean scores were given to questions like “Synchronous learning could delay or make it difficult to download or play large files” (mean = 3.5537) and “Synchronous class could cause confusion and waste of time if we have differences in learners’ abilities” (mean = 3.4215), indicating that respondents were aware of the synchronous learning’s technical and pedagogical difficulties. Other things with reasonably high mean scores include items like “Examination is challenging in synchronous learning” (mean = 3.4711) and “The flexibility of Synchronous class reduces the interaction in class” (mean = 3.5207), which received relatively lower mean scores, indicating that respondents perceived these drawbacks to a lesser extent.

4.3 Advantages of asynchronous learning compared with synchronous learning

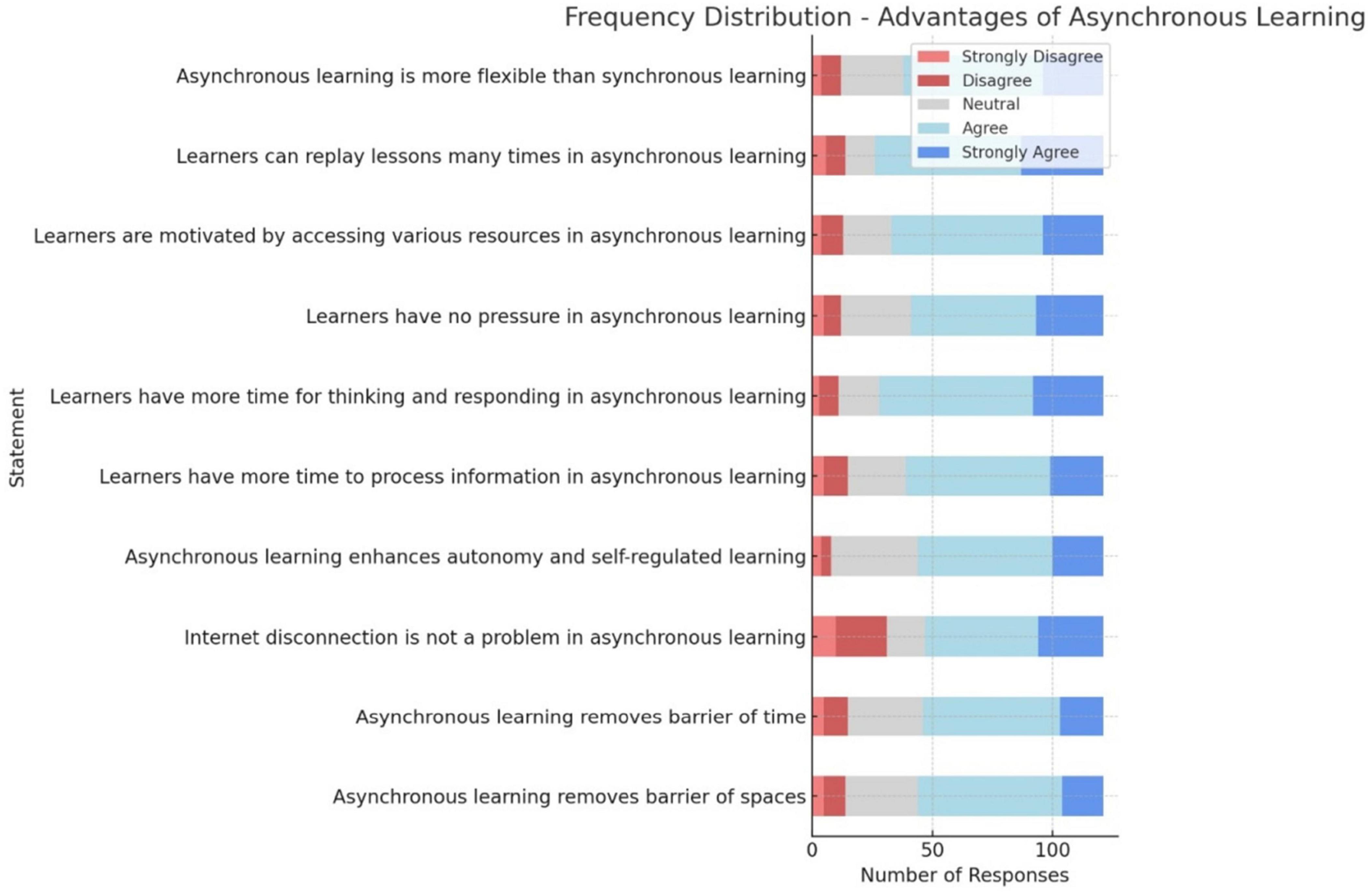

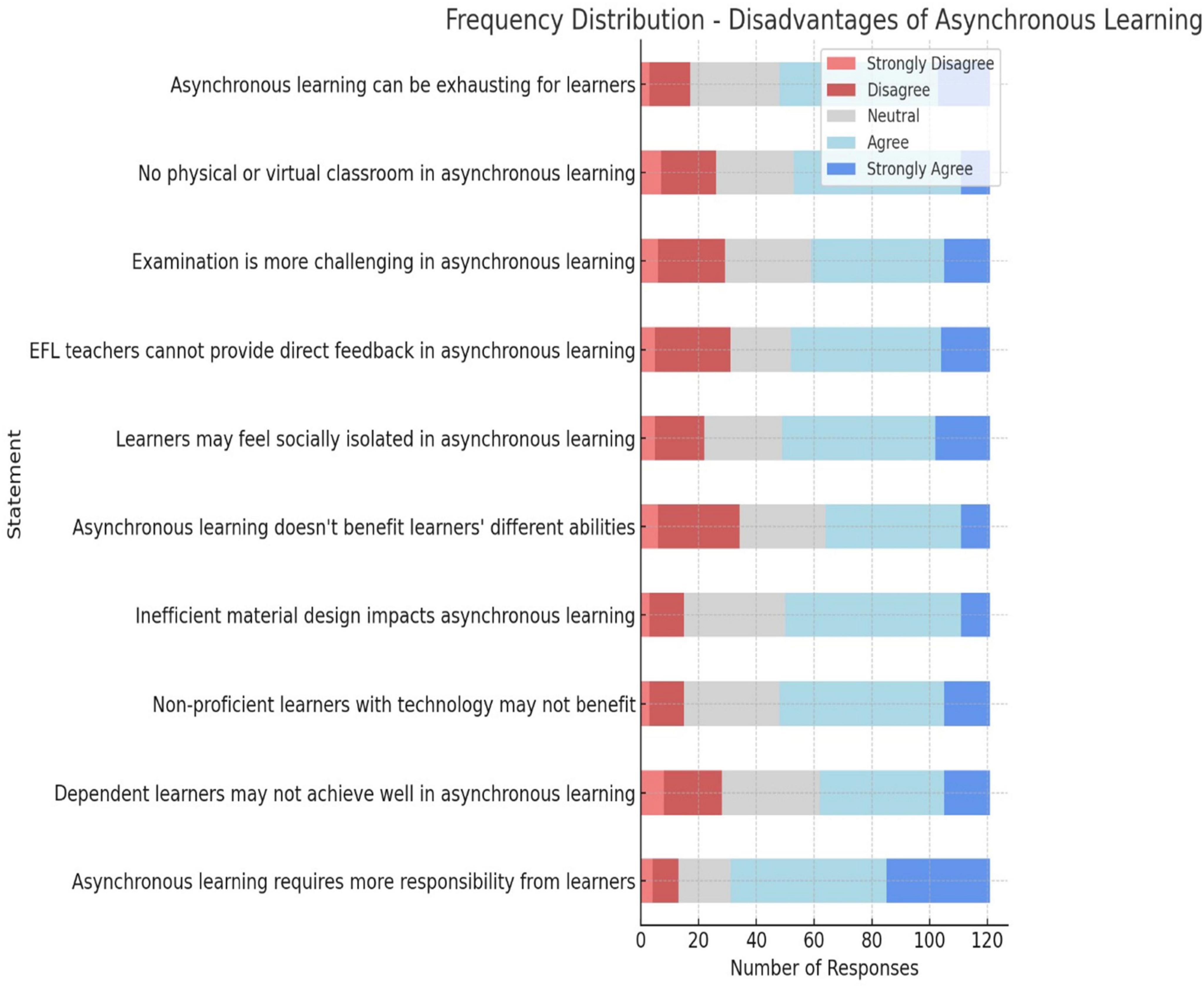

The rescan in Figures 5, 6 implies that respondents were aware of several benefits of asynchronous learning. The response “Learners can replay the lesson many times in asynchronous learning” had the highest mean score (mean = 3.9008), showing that participants valued the flexibility to examine and revisit course content at their leisure. The statements “Learners have more time for thinking and responding in asynchronous learning” (mean = 3.8926) and “Asynchronous learning enhances autonomy and self-regulated learning” (mean = 3.7107) also earned relatively high mean scores. These findings imply that participants valued asynchronous learning’s capacity to foster autonomous thought, self-directed learning, and engagement.

Additionally, moderate mean scores were given to questions like “Asynchronous learning removes the barrier of time more than synchronous learning” (mean = 3.6033) and “Asynchronous learning removes the barrier of spaces more than synchronous learning,” indicating that respondents were aware of the flexibility and convenience of asynchronous learning concerning time and location. Furthermore, the responses to items like “The Internet disconnection would not be a real problem in asynchronous learning” (mean = 3.4959) and “Learners have no pressure in asynchronous learning” (mean = 3.7521), on the other hand, had slightly lower mean scores, indicating that respondents thought less highly of these benefits.

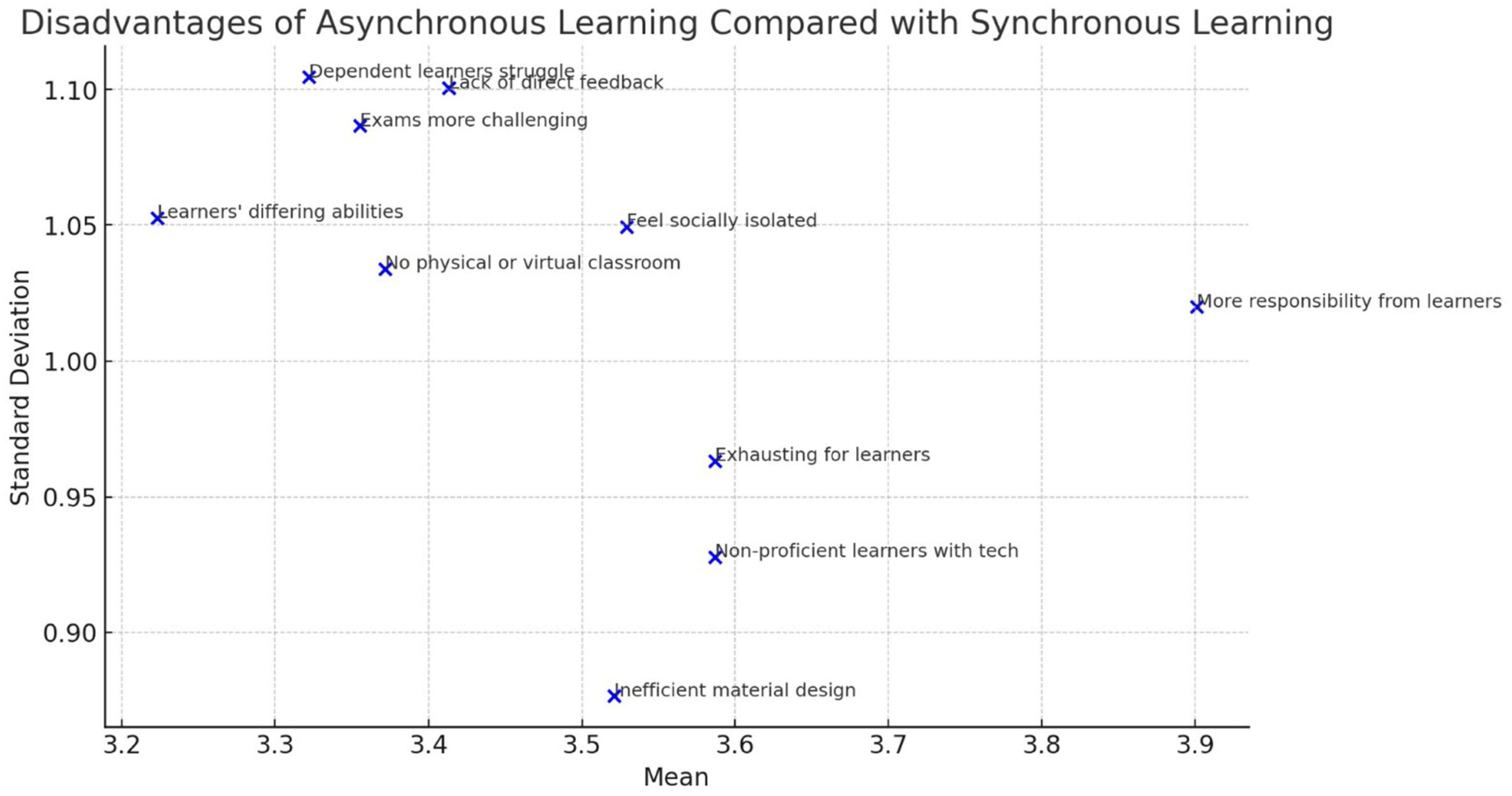

4.4 Disadvantages of asynchronous learning compared with synchronous learning

According to the results in Figures 7, 8, respondents were aware of several drawbacks of asynchronous learning. The response “Asynchronous learning could require more responsibility from learners” had the highest mean score (mean = 3.9008), indicating that participants thought asynchronous learning environments required them to have self-control, self-motivation, and autonomous learning skills. The statements “Non-proficient learners of using technology would not reach the aimed benefits of the lesson in Asynchronous learning” (mean = 3.5868) and “Asynchronous learning could be exhausting for learners since it needs higher concentration” (mean = 3.5868) also received relatively high mean scores. According to these findings, respondents were aware of the potential difficulties with technological competence and the greater need for concentration and focus in asynchronous learning.

Figure 7. Descriptive statistics of disadvantages of asynchronous learning compared with synchronous learning.

Additionally, moderate mean scores were given to statements like “Asynchronous learning cannot be beneficial for learners’ different abilities” (mean = 3.2231) and “Dependent learners would not be able to achieve well in Asynchronous learning” (mean = 3.3223), indicating that respondents were aware of the potential challenges faced by students who depend on more structured and guided instruction or who have different learning needs. In contrast, responses to items like “EFL teachers could not provide direct feedback for learners in asynchronous learning” (mean = 3.4132) and “Examination is more challenging in asynchronous learning” (mean = 3.3554) had slightly lower mean scores, indicating that respondents thought these drawbacks were felt to a lesser degree.

4.5 Comparison of the main findings of the pros and cons between synchronous and asynchronous learning

The comparative descriptive statistics of the benefits of synchronous learning versus asynchronous learning show that respondents agree on these items. “Synchronous learning helps in saving time for learners since learners could log on at home or outside” (mean = 3.9669), suggesting that most participants preferred synchronous learning due to its flexibility in location. The item “Learners can replay the lesson many times in asynchronous learning” (mean = 3.9008) showed the advantages of asynchronous learning. Thus, synchronous and asynchronous learning was considered flexible, but asynchronous learning was more relaxed.

In terms of learning gains, instructors see both styles differently. The item “Synchronous learning allows students to communicate with the instructor” had a high mean score (3.7769). However, “Learners have more time for thinking and responding in asynchronous learning” (mean = 3.8926) received strong agreement. Synchronous learning allows greater teacher-student engagement, whereas asynchronous learning allows more time for knowledge processing. Also, “Synchronous learning allows greater collaboration more than asynchronous mode” (mean = 3.2810) had high agreement, while “Asynchronous learning enhances autonomy and self-regulated learning” (mean = 3.7107) did not. These results suggest that participants valued synchronous learning for its collaborative nature and asynchronous learning for its emphasis on autonomous thought and self-directed learning.

However, synchronous and asynchronous learning have common disadvantages that were widely agreed upon, such as synchronous mode-related issues. “Synchronous class could be boring for some learners since it requires more attention from them” (mean = 3.5868). “Asynchronous learning could require more responsibility from learners” (mean 3.9008), “Non-proficient learners of using technology would not reach the aimed benefits of the lesson in Asynchronous learning” (mean 2.5868), “Dependent learners would not be able to achieve well in Asynchronous learning” (mean 0.3223), and “Asynchronous learning could be exhausting for learners since it needs higher concentration” (mean 0.5868). These items about the disadvantages of both modes show that instructors thought students needed to be more responsible in synchronous and asynchronous learning, especially in asynchronous learning, where they had to self-regulate.

In particular, asynchronous learning may necessitate that students assume greater accountability, which is regarded as a disadvantage due to the possibility that they lack the necessary competencies. Thus, the online learning process, especially in asynchronous mode, could be adversely affected if students are not prepared to assume complete accountability for their education. Therefore, EFL instructors are under significant pressure to educate students about the importance of taking responsibility for online education. Additionally, among the disadvantages of both modes, “Examination is challenging in synchronous learning” (mean = 3.4711) and “Examination is more challenging in asynchronous learning” (mean = 3.3554) share some similarities. Both statements received a high level of agreement, suggesting that online learning for examinations may be difficult in general but that it may be especially difficult in asynchronous learning.

Moreover, the contrast items of the disadvantages of synchronous learning and asynchronous learning are the items “The slow speed of the internet can disrupt synchronous class” (mean = 3.9174), for synchronous learning, while for asynchronous learning the items like “The Internet disconnection would not be a real problem in asynchronous learning” (mean = 3.4959). Thus, both modes of online learning could be affected to some degree by the internet connection; however, in asynchronous learning, disconnection would not greatly affect the learning process because of the high level of flexibility in the time of learning and taking the classes.

5 Discussion

The result of this study revealed that, although synchronous learning could be flexible for learners, asynchronous learning could be more flexible concerning timing and location. Previous Saudi studies shared similar results even though they were conducted for higher education (Al-Nofaie, 2020; Al-Jarf, 2020). They found that EFL learners prefer asynchronous learning due to its flexibility. Another Saudi study conducted by Fageeh and Mekheimer (2013) seems to have a similar result since they found that EFL learners have a positive attitude toward asynchronous online learning because of its flexibility in learning, which reflects positively on their language improvement.

Another study’s main result is that synchronous learning allows teacher-student interaction, which may not exist in asynchronous learning. Thus, the study’s results reported that teachers valued synchronous learning for its collaborative and interactive nature. These findings are in agreement with other previous Saudi studies (Bukhari and Basaffar, 2019; Al-Nofaie, 2020; Bin Dahmash, 2020, 2021; Hashmi et al., 2021; Albogami, 2022; Al-Jarf, 2020). They found that learners perceived synchronous learning could help them communicate with the instructor to get quick feedback for their learning. Kohnke and Moorhouse (2022) mentioned that synchronous learning gives students immediate input and improves their ability to communicate with others, which helps them feel supported while they learn a language. Like face-to-face learning, online synchronous learning can help students avoid evil thoughts and understand how they affect their learning (Kohnke and Moorhouse, 2022). Nevertheless, the absence of instant instructor feedback in asynchronous learning results in students needing to be more aware of their progress (Dada et al., 2019).

Further, synchronous learning facilitates student-teacher and peer-to-peer interaction, enabling concurrent idea exchange and learning improvement. This could help students who must use more language and practice (Cheung, 2021; Shoepe et al., 2020; Sulistyani, 2020). Similarly, Memari (2020) conducted a study that investigated the benefits of online learning for Iranian EFL learners. Although the context of the study is different from the present study, they reach a similar finding, in which he found synchronous learning can enhance learners’ productivity. In contrast, asynchronous learning can improve their recognition of the language. However, this finding differs from Alhaider (2023) study; it has been reported that learners perceived online synchronous learning could help them communicate in writing more than speaking skills. Also, Al-Qahtani (2019) revealed that one of the results of his study was that learners complained of a lack of interaction in online synchronous learning.

Another study’s main result is that synchronous and asynchronous learning have common disadvantages that were widely agreed upon. Learners need to be more responsible for their synchronous learning, while learners need to be more responsible for their asynchronous learning. This finding could be similar to studies conducted by Bin Dahmash (2020, 2021) since these studies revealed that learners’ perceived online learning increases their commitment. However, they take it as an advantage to help them to enhance their self-reliance skills. Further, previous researchers (Bukhari and Basaffar, 2019; Albogami, 2022) reported that one of the advantages of online learning is enhancing learners’ accountability. A possible reason for the different results from these studies is that they have been conducted on university students; therefore, taking accountability in learning is recommended in higher education.

Further, the main advantage of asynchronous learning is that it allows learners to be autonomous and enhance their self-regulated learning. This result is similar to other’ previous findings (Al-Jarf, 2020; Albogami, 2022) since their studies revealed that learners’ are aware of and value asynchronous learning since it requires them to improve their self-regulated skills. Thus, the online learning process, especially in asynchronous mode, could be adversely affected if students are not prepared to assume complete accountability for their education (Albogami, 2022). Additionally, students’ autonomy, self-control, and self-research abilities can be enhanced through online learning, enabling them to be more aware of their education and make efficient use of their free time.

Additionally, the research revealed that synchronous learning can help EFL students feel less anxious by creating a safe space free of criticism. However, learners may find it difficult and demanding to concentrate on academic tasks when utilizing online learning (Fawaz et al., 2022). Despite this, it may benefit shy learners since it promotes greater engagement and involvement. The results show that synchronous learning might work better for students who like to learn in a more relaxed setting (Zhong et al., 2022). This finding is similar to Bin Dahmash (2020, 2021) since she found that one of the challenges of synchronous learning is the lack of eye contact between the instructors and students. Other previous studies confirmed the challenges of online class management and concentration during online learning (Alhaider, 2023; Al-Qahtani, 2019).

According to Martin et al. (2021), one of the benefits of asynchronous learning over synchronous learning is that it permits students to access and review materials at any time. This approach’s lack of time constraints enhances its flexibility beyond synchronous learning (Martin et al., 2021). Additionally, asynchronous learning improves students’ comprehension of material (Galikyan and Admiraal, 2019). This study reported that one of the main advantages of asynchronous learning is that learners can replay the lesson more than one time, and this finding is similar to previous studies (Bin Dahmash, 2021; Alhaider, 2023). As a result, it is advisable to utilize synchronous and asynchronous learning modalities for various language proficiency levels. Synchronous learning is better suited for those requiring support and communication, whereas asynchronous learning is more appropriate for those with linguistic issues requiring more time (Ogbonna et al., 2019).

Further, another significant result of synchronous and asynchronous learning is the difficulties of conducting examinations, especially in asynchronous learning. This finding seems to be similar to other previous findings (Al-Nofaie, 2020; Bin Dahmash, 2020, 2021; Hashmi et al., 2021) since they claimed that it is challenging to evaluate and examine learners in synchronous and asynchronous online learning. The main negative issue related to the examination is cheating in exams, so instructors cannot effectively evaluate learners. Although electronic tools could help report the percentage of plagiarism in submitting projects, tasks, and assignments, the online exam could be challenging to control.

Moreover, the contrasting results of both online learning modes could be affected to some degree by the internet connection; however, in asynchronous learning, disconnection would not significantly affect the learning process because of the high flexibility in learning and taking the classes. Internet disruption negatively affects the learning process since learners must be online simultaneously with the instructor. These findings are in agreement with other previous studies (Al-Nofaie, 2020; Bin Dahmash, 2020, 2021; Hashmi et al., 2021; Albogami, 2022) since they found that asynchronous learning could help in reducing the challenges of technical issues that happen during synchronous learning.

6 Limitations and future implications

The research’s limitations include the fact that it has only been performed in Saudi Arabia and did not revolve around other diverse contexts. Furthermore, the research only examines EFL teachers’ perceptions and does not include learners’ perceptions. Another significant limitation of the research is its exclusive use of questionnaire methods and its quantitative reporting of data. In comparison to the analysis of students, which involved a larger number of participants, the number of teachers in the study could be considered relatively low. A final limitation is the research timeframe and the technological constraints that might affect the findings.

Therefore, based on the result of this study and the limitations encountered, this research recommends conducting future studies that are concerned with a comparative study between different ages and experiences of teachers, since this could be an effective factor for applying online learning in Saudi schools. Regarding H1 of this research, future studies should focus on comparing results from different regions, given the influence of geographic area and social and cultural factors on teachers’ perceptions of learning. Finally, a further longitudinal study could support and develop teaching and learning online in Saudi Arabia. Regarding H1, more researches are needed to investigate learners’ achievements in EFL through the asynchronous mode of online learning.

This research can guide Saudi Arabian educators in designing a curriculum that effectively incorporates synchronous and asynchronous learning modes in EFL settings. It would also help the institution invest in its technological infrastructure to control technical drawbacks. Furthermore, it helps the policymaker’s professional development programs educate teachers with online teaching skills.

7 Conclusion

The research shows that EFL instructors’ views on synchronous and asynchronous online learning are mostly identical. Synchronous learning has advantages such as time efficiency and online accessibility, although it also presents challenges such as technological glitches and difficulties in maintaining focus. Asynchronous learning provides flexibility, allows numerous topic reviews, and promotes learner autonomy. However, it also comes with challenges, such as increased student accountability, self-regulation, and motivation. Although the move to online learning during the COVID-19 outbreak has been seen as advantageous, language learners may benefit more from a mix of the two forms. Synchronous learning provides immediate interaction and quick responses, but it might be inflexible and limited by technology, resulting in less involvement. Asynchronous learning offers flexibility regarding time and location, more independence, extended processing periods, and access to various instructional materials. Nonetheless, instructors continue encountering challenges when utilizing both approaches, potentially attributable to a lack of readiness. More research must determine how teachers feel about the pros and cons of using synchronous and asynchronous online learning for EFL classes.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the author, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Umm AL-Qura University Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

NA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author declares that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank all participants of EFL teachers in Saudi Arabia for cooperating to participate in this research.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Albogami, M. M. (2022). Do online classes help EFL Learners improve their english language skills? A qualitative study at a Saudi university. Arab World English J. 2, 281–289. doi: 10.24093/awej/covid2.18

Alghamdi, A., and Alghamdi, M. (2021). Online learning during corona virus epidemic in Saudi Arabia: Students’ Attitudes and complications. Online Learn. 12:464. doi: 10.3390/children9081170

Alhaider, S. M. (2023). Teaching and learning the four English skills before and during the COVID-19 era: Perceptions of EFL faculty and students in Saudi higher education. Asian Pac. J. Second Foreign Lang. Educ. 8, 1–19.

Al-Harbi, A. M. (2022). Reading skills among EFL learners in Saudi Arabia: A review of challenges and solutions. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 15, 204–208.

Alhazbi, S., and Hasan, M. A. (2021). The role of self-regulation in remote emergency learning: Comparing synchronous and asynchronous online learning. Sustainability 13:11070.

Alibakhshi, G., and Mohammadi, M. J. (2016). Synchronous and asynchronous multimedia and Iranian EFL learners’ learning of collocations. Appl. Res. English Lang. 5, 237–254.

Al-Jarf, R. (2020). Distance learning and undergraduate Saudi students’ agency during the Covid-19 pandemic. Bull. Transil. Univers. Braşov 13:2.

Almusharraf, N., and Khahro, S. (2020). Students’ satisfaction with online learning experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 15, 246–267.

Al-Nofaie, H. (2020). Saudi university students’ perceptions towards virtual education during Covid-19 pandemic: A case study of language learning via Blackboard. Arab World English J. 11, 4–20. doi: 10.24093/awej/vol11no3.1

Al-Qahtani, M. H. (2019). Teachers’ and Students’ perceptions of virtual classes and the effectiveness of virtual classes in enhancing communication skills. Arab World English J. 1, 223–240. doi: 10.24093/awej/efl1.16

Al-Seghayer, K. (2019). Unique challenges Saudi EFL learners face. Res. English Lang. Teach. 7, 490–515.

Alshumaimeri, Y. A., and Alhumud, A. M. (2021). EFL students’ perceptions of the effectiveness of virtual classrooms in enhancing communication skills. English Lang. Teach. 14, 80–96.

Al-Tamimi, R. (2019). Policies and issues in teaching English to Arab EFL learners: A Saudi Arabian perspective. Arab World English J. 10, 68–76.

Althobaiti, H. (2020). The significance of learning english in Saudi Arabia. J. Crit. Res. Lang. Lit. 1, 20–24.

Alyousef, M. (2023). Saudi Arabian Elementary teachers’ perceptions of ELearn technology during COVID-19 pandemic. Nashville, TN: Tennessee State University.

Alzain, E. (2022). Online EFL learning experience in saudi universities during COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. English Lang. Lit. Res. 11, 109–125.

Alzobiani, I. (2020). The qualities of effective teachers as perceived by Saudi students and teachers. English Lang. Teach. 13, 32–47.

Ariyanti, A. (2020). EFL students’ challenges towards home learning policy during the COVID-19 outbreak. IJELTAL 5, 167–175.

Assaneo, M. F., Ripollés, P., Orpella, J., Lin, W. M., de Diego-Balaguer, R., and Poeppel, D. (2019). Spontaneous synchronisation to speech reveals neural mechanisms facilitating language learning. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 627–632.

Aziz Ansari, K., Farooqi, F. A., Khan, S., Alhareky, M., Trinidad, M. A., and Abidi, T. (2021). Perception on online teaching and learning among health sciences students in higher education institutions during the COVID-19 lockdown–ways to improve teaching and learning in Saudi colleges and universities. F1000Research 10:177.

Bahanshal, D. A. (2013). The Effect of large classes on english teaching and learning in Saudi secondary schools. English Lang. Teach. 6, 49–59.

Bin Dahmash, N. (2020). I couldn’t join the session’: Benefits and challenges of blended learning amid COVID-19 from EFL students. Int. J. English Linguist. 10, 221–230. doi: 10.5539/ijel.v10n5p221

Bin Dahmash, N. (2021). ‘We were scared of catching the virus’: Practices of Saudi college students during the COVID-19 crisis. Int. J. English Linguist. 11, 152–165. doi: 10.5539/ijel.v11n1p152

Binyamin, S., Rutter, M., and Smith, S. (2019). Extending the technology acceptance model to understand students’ use of learning management systems in Saudi higher education. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 14, 4–21.

Bukhari, S. S. F., and Basaffar, F. M. (2019). EFL learners’ perception about integrating blended learning in ELT. Arab World English J. 5, 190–205. doi: 10.24093/awej/call5.14

Chen, W., and You, M. (2007). “The differences between the influences of synchronous and asynchronous modes on collaborative learning project of industrial design,” in Proceedings of the 2nd international conference, OCSC 2007, held as part of HCI international 2007: Online communities and social computing, (Beijing), 22–27.

Cheung, A. (2021). Synchronous online teaching, a blessing or a curse? Insights from EFL primary students’ interaction during online English lessons. System 100:102566.

Clarin, A. S., and Baluyos, E. L. (2022). Challenges encountered in the implementation of online distance learning. EduLine 2, 33–46.

Dada, E. G., Alkali, A. H., and Oyewola, D. O. (2019). An investigation into the effectiveness of asynchronous and synchronous e-learning mode on students’ academic performance in national open university (NOUN), Maiduguri centre. Int. J. Modern Educ. Comp. Sci. 11, 54–64.

Dao, P., Bui, T. L. D., Nguyen, D. T. T., and Nguyen, M. X. N. C. (2023). Synchronous online English language teaching for young learners: Insights from public primary school teachers in an EFL context. Comp. Assist. Lang. Learn. 58, 1–30.

Ding, J. (2021). Exploring effective teacher-student interpersonal interaction strategies in English as a foreign language listening and speaking class. Front. Psychol. 12:765496. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.765496

Edwards, A. A., Joyner, K. J., and Schatschneider, C. (2021). A simulation research on the performance of different reliability estimation methods. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 81, 1089–1117.

Fageeh, A. I., and Mekheimer, M. A. (2013). Effects of blackboard on EFL academic writing and attitudes. JALT CALL J. 9, 169–196.

Fawaz, M., Al Nakhal, M., and Itani, M. (2022). COVID-19 quarantine stressors and management among Lebanese students: A qualitative research. Curr. Psychol. 41, 7628–7635.

Feliz, S., Ricoy, M.-C., Buedo, J.-A., and Feliz-Murias, T. (2022). Students’ E-learning domestic space in higher education in the new normal. Sustainability 14:7787.

Galikyan, I., and Admiraal, W. (2019). Students’ engagement in asynchronous online discussion: The relationship between cognitive presence, learner prominence, and academic performance. Internet High. Educ. 43:100692.

Gambo, Y., and Shakir, M. Z. (2021). Review on self-regulated learning in smart learning environment. Smart Learn. Environ. 8, 1–14.

García-Machado, J., Martínez, A., Dospinescu, N., and Dospinescu, O. (2024). How the support that students receive during online learning influences their academic performance. Educ. Inform. Technol. 56, 1–25. doi: 10.1007/s10639-024-12639-6

Hariadi, I. G., and Simanjuntak, D. C. (2020). Exploring the experience of EFL students engaged in asynchronous e-learning. Acad. J. Perspect. Educ. Lang. Lit. 8, 72–86.

Hashmi, U. M., Rajab, H., and Ali Shah, S. R. (2021). ELT during lockdown: A new Frontier in online learning in the saudi context. Int. J. English Linguist. 11, 44–53. doi: 10.5539/ijel.v11n1p44

Kerrigan, J., and Andres, D. (2022). Technology-enhanced communities of practice in an asynchronous graduate course. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 50, 473–487.

Kohnke, L., and Moorhouse, B. L. (2022). Facilitating synchronous online language learning through Zoom. Relc J. 53, 296–301.

Laachir, A., El Karfa, A., and Ismaili Alaoui, A. (2022). Investigating Foreign language anxiety among moroccan EFL university students in face-to-face and distance learning modes. Arab World English J. 13, 196–214.

Lim, C. L., She, L., and Hassan, N. (2022). The impact of live lectures and Pre-recorded videos on students’ online learning satisfaction and academic achievement in a Malaysian Private University. Int. J. Inform. Educ. Technol. 12, 874–880. doi: 10.18178/ijiet.2022.12.9.1696

Lowenthal, P., Dunlap, J., and Snelson, C. (2017). Live synchronous web meetings in asynchronous online courses: Reconceptualizing virtual office hours. Online Learn. J. 21:2598.

Martin, F., Sun, T., Turk, M., and Ritzhaupt, A. D. (2021). A meta-analysis on the effects of synchronous online learning on cognitive and affective educational outcomes. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distribut. Learn. 22, 205–242.

Memari, M. (2020). Synchronous and asynchronous electronic learning and EFL learners’ learning of grammar. Iran. J. Appl. Lang. Res. 12, 89–114.

Mohammadi, G. (2023). Teachers’ CALL professional development in synchronous, asynchronous, and bichronous online learning through project-oriented tasks: Developing CALL pedagogical knowledge. J. Comput. Educ. 85, 1–22.

Ogbonna, C. G., Ibezim, N. E., and Obi, C. A. (2019). Synchronous versus asynchronous e-learning in teaching word processing: An experimental approach. South Afr. J. Educ. 39, 1–15.

Perveen, A. (2016). Synchronous and asynchronous e-language learning: A case research of virtual university of Pakistan. Open Praxis 8, 21–39.

Pusuluri, S., Mahasneh, A., and Alsayer, B. (2017). The application of blackboard in the English courses at Al Jouf University: Perceptions of students. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 7, 106–111. doi: 10.17507/tpls.0702.03

Putri, E. R. (2021). EFL teachers’ challenges for online learning in rural areas. UNNES TEFLIN Natl. Semin. 4, 402–409.

Rabbianty, E. N., and Wafi, A. (2021). Maximizing the use of whatsapp in english remote learning to promote students’engagement at madura. LET Linguist. Lit. English Teach. J. 11, 42–60.

Riwayatiningsih, R., and Sulistyani, S. (2020). The implementation of synchronous and asynchronous e-language learning in EFL setting: A case research. J. Basis 7, 309–318.

Sari, I. N., and Wahyudin, D. (2023). Effectiveness of implementing synchronous and asynchronous blended E-learning in stunting prevention and treatment training programs. JTP J. Teknol. Pendidikan 25, 101–106.

Shoepe, T. C., McManus, J. F., August, S. E., Mattos, N. L., Vollucci, T. C., and Sparks, P. R. (2020). Instructor prompts and student engagement in synchronous online nutrition classes. Am. J. Dist. Educ. 34, 194–210.

Sithole, A., Mupinga, D. M., Kibirige, J. S., Manyanga, F., and Bucklein, B. K. (2019). Expectations, challenges and suggestions for faculty teaching online courses in higher education. Int. J. Online Pedag. Course Des. 9, 62–77.

Smith, E. (2023). Challenges encountered in the implementation of online distance learning in African countries. Int. J. Online Dist. Learn. 4, 1–11.

Song, D., and Kim, D. (2021). Effects of self-regulation scaffolding on online participation and learning outcomes. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 53, 249–263.

Sriwichai, C. (2020). Students’ readiness and problems in learning english through blended learning environment. Asian J. Educ. Train. 6, 23–34.

Stewart, S. (2020). Student engagement in both synchronous and asynchronous online learning. Thriving as an online K-12 educator: Essential practices from the field. Milton Park: Routledge, 55.

Sulistyani, S. (2020). Modeling online classroom interaction to support student language learning. Ideas 8, 446–457.

Tarazi, A., and Ortega-Martín, J. L. (2023). Enhancing EFL students’ engagement in online synchronous classes: The role of the Mentimeter platform. Front. Psychol. 14:1127520. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1127520

Vurdien, R. (2019). Videoconferencing: Developing students’ communicative competence. J. Foreign Lang. Educ. Technol. 4, 269–298.

Watkins, J., and Portsmore, M. (2022). Designing for framing in online teacher education: Supporting teachers’ attending to student thinking in video discussions of classroom engineering. J. Teach. Educ. 73, 352–365.

Zeng, H., and Luo, J. (2023). Effectiveness of synchronous and asynchronous online learning: A meta-analysis. Interact. Learn. Environ. 85, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2023.2197953

Zhang, K., and Wu, H. (2022). Synchronous online learning during COVID-19: Chinese university EFL students’. Perspect Sage Open 12:21582440221094821.

Zhang, T., and Yu, S. (2023). Effects of asynchronous interaction on positive emotional experiences of learners during online learning. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 18:48.

Zhang, X., Pi, Z., Li, C., and Hu, W. (2020). Intrinsic motivation enhances online group creativity via promoting members’ effort, not interaction. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 52:606618. doi: 10.1111/bjet.13045

Keywords: synchronous, asynchronous, online learning, EFL teachers, advantages, disadvantages

Citation: Alfares N (2024) Is synchronous online learning more beneficial than asynchronous online learning in a Saudi EFL setting: teachers’ perspectives. Front. Educ. 9:1454892. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1454892

Received: 25 June 2024; Accepted: 11 October 2024;

Published: 24 October 2024.

Edited by:

Octavian Dospinescu, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University, RomaniaReviewed by:

Ni Komang Arie Suwastini, Ganesha University of Education, IndonesiaCarla Morais, University of Porto, Portugal

Copyright © 2024 Alfares. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nurah Alfares, bnNmYXJlc0B1cXUuZWR1LnNh

Nurah Alfares

Nurah Alfares