- Department of Curriculum and Instruction, College of Education, Amman Arab University, Amman, Jordan

The incorporation of technology in English as a Foreign Language (EFL) classroom has drastically transformed conventional learning models by offering innovative ways to boost students’ engagement and improve learning outcomes. This study investigates the impact of using YouTube as an educational tool to enhance EFL instruction in Saudi Arabia. A total of 200 EFL students were divided into two groups: An experimental group which used You Tube as a source of learning and another group which used normal curriculum. A mixed-methods approach was employed, combining quantitative data from a paired-sample t-test with qualitative feedback from students. The results for paired-sample t-test computations revealed a statistically significant difference (p = 0. 003) across the proficiency level indicating improvement in students’ speaking and listening skills at higher proficiency levels. Of the qualitative answers, motivational and participation enhancement were overemphasized. The research points that the integration of YouTube in EFL classrooms can lead to a remarkable increase in language learning especially in the learning area of listening and speaking abilities among the students. These results offer practical implications for educators seeking to integrate multimedia tools into their teaching strategies to promote more interactive and effective learning experiences.

1 Introduction

With the help of contemporary technologies, there has been a shift in the paradigms of learning systems and multiple tools and resources are available online that help in language learning (Wang et al., 2023). There is no doubt that YouTube alone presents lots of learning resources that can be used to enhance the learning of languages. In detail, this paper explores the role brought by the YouTube platform in enhancing the academic achievement of EFL learners in Saudi Arabia in terms of growth in vocabulary, listening skills, and cultural sensitivity, and an overall enhancement in language proficiency.

Since the introduction of YouTube in the year 2005, it has developed from a mere video-sharing site to an instructional tool. Its library is so vast that it offers anything that encompasses languages from language learning tutorials to cultural documentaries and other products for special learning ability persons and every type of learner, including beginners and the advanced. The reasons that supported the integration of the YouTube platform in educational settings are mainly associated with the opportunities for authentic language exposure, engagement, and the development of a globally connected learning community. According to Hwang and Chen (2022), digital platforms offer significant pedagogical benefits, especially in terms of student motivation and participation. Their study found that EFL learners who engaged with multimedia content, such as YouTube, exhibited higher levels of engagement compared to those relying solely on textbooks.

Another benefit of incorporating YouTube in teaching EFL is improving student’s REAL English in particular, EFL students. Classic textbooks are more often than not teachers’ use of language that may not even be real in daily use. For instance, while using the ANIME genre, one is limited to synthetic English and script which may lack colloquial expressions, idioms, or even different regional accents but YouTube has it all. It is vital for nurturing the ability to listen and cultural sensitivity (Alwehaibi, 2015). Rahman et al. (2018) further emphasized the idea that multimedia resources promote interactive learning environments, allowing students to practice language skills in real-world contexts. The author highlighted that video-based learning materials are particularly effective in fostering listening and speaking proficiency, as they simulate authentic language use and provide visual and auditory cues essential for comprehension.

In terms of how it can be implemented to teach foreign languages some of the advantages are given below: YouTube enables interaction and sets situations that might be difficult to implement within the normal practicing of language learning. When it comes to videos, the learners are also more in control of their rate of learning as they are able to rewind, pause and refresh their memory at their own will (Almurashi, 2016). Teachers are in a position to assign such YouTube videos as a discussion, an in-class activity or homework where they are presented in different ways in which the students can interact with the language (Faziah and Tarihoran, 2024; Dawson et al., 2021). Besides, YouTube offers content for learners with different learning modalities, that is, auditory and visual, as the content is more engaging for students than conventional written learning materials (Binmahboob, 2020). This flexibility enables the educators to teach students at their own pace enhancing the quality of the learning institutions by accommodating for students with such a learning capacity.

Language acquisition is not merely memorizing the contents of Language. It entails acclimatizing one’s self to the culture of the Foreign Language. YouTube provides date infinite amount of cultural perspectives through travel blogs, interviews in documentaries, and casual interactions on camera. Cultural contexts increase the overall communicative ability of EFL students and these resources help them in this manner (Duffy, 2008).

As one of the most widely used social networks, YouTube connects learners and educators globally. As for the teaching of EFL, YouTube can support the commenting, live streaming, and group projects, which can help the learners to build the sense of community (Zabidi and Wang, 2021). This kind of approach is particularly helpful for EFL students as it provides them with an opportunity to interact with native speakers and learners from other linguistic backgrounds, exchange experiences, and get familiar with different cultural attitudes toward language (Yang and Yeh, 2021). Watching videos on YouTube with international students allows students to enhance their language proficiency and intercultural communication, which are important components of language acquisition in the context of the digital environment (Tran et al., 2024; Lee and Choi, 2021). This paper aims to establish that the incorporation of YouTube into the teaching and learning process of EFL must be done soundly by adopting certain teaching strategies. Teachers are responsible for selecting content that aligns with students’ learning needs while ensuring that EFL learners possess the necessary language and cultural background to comprehend the material. Effective teaching strategies can be divided into three phases: the first phase involves pre-viewing strategies that prepare learners for the upcoming content; the second phase includes during-viewing strategies that engage learners actively in the learning process; and the third phase consists of post-viewing strategies, which help deepen learners’ understanding or enable them to apply their knowledge in projects that integrate what they have learned (Berk, 2009; Wang et al., 2023). These strategies ensure that YouTube is not merely a passive tool but an active component of EFL learning.

In conclusion, this paper has found that exploring the use of YouTube in the teaching and learning of English as a Foreign Language has benefits that go beyond the physical classroom setting. Because of the ability to offer real language input, interaction, culture, and other people in the target language all of which are supplemented by the media aspects, the tool is central in current EFL learning. When used appropriately in the instruction and assessment of EFL, YouTube offers practical means that enable educators to facilitate meaningful learning and help their EFL learners to communicate in English effectively in the twenty-first century.

2 Literature review

Ever since its inception, YouTube has been a subject of interest for researchers who wanted to determine its effects on teaching EFL students. According to the recent research, watching YouTube videos gives real-life exposure to the actual use of language which in turn improves the listening and speaking ability of the learner (Hwang and Chen, 2022). Furthermore, there is evidence that the platform helps to foster learning and motivation through multimedia (Lee and Choi, 2021). Teaching through YouTube has become popular in the past few years and many scholars have pointed out that it is beneficial in EFL classrooms. For example, Faziah and Tarihoran (2024) noted that the use of YouTube in language learning not only enhances participation but also enhances language learning because it offers a variety of learning activities.

According to Alhaider (2023), multimedia environments have a positive impact on EFL learners; and social media technology plays an effective role in teaching and learning English language skills. According to Al-Khalidi and Khouni (2021), Social media technology plays an effective role in education and EFL education. It has the potential to enhance student engagement by offering authentic language exposure and interactive learning opportunities. This section and it has already been presented, aims to showcase relevant literature on the use of YouTube in language learning regarding vocabulary, listening, cultural understanding, and learner involvement. In a particular context, YouTube serves a highly effective purpose in generating the needful exposure to the use of real English which is of paramount importance in the growth of the vocabulary precisely for EFL students. Snelson and Perkins (2009) said that due to the variation of content shared on YouTube, the learner will be able to experience the new words in different settings hence increasing the possibility of improved knowledge and retention ability. Besides, Cross (2011) determined that the use of visuals, subtitling, and other such features of YouTube make the video appealing to the learners and help develop their powers to guess the meanings of new vocabulary leading to the effective acquisition of new vocabulary as well as improving their listening skills.

The listening skill of a learner is another area that has experienced positive progress from the training offered by YouTube. Current studies support the use of authentic AV materials in improving the listening skills of the learners (Tani et al., 2022). In their study, Lee and Choi (2021) found that the learners who interacted with the YouTube videos outperformed the other learners in the listening comprehension tests than the conventional exercises. The fact that YouTube is an online platform enables learners to watch a video repeatedly, which enhances the process of exposure and comprehension (Zabidi and Wang, 2021). These features of YouTube make it a useful tool in repeated listening and active learning to reinforce the skills being taught.

There are large collections of videos on YouTube and by going through those videos learners gain a better understanding of other cultures and social behaviors. As Brook pointed out in the year 2011, YouTube videos provide learners a chance to see through the eyes of native speakers, where idiosyncrasies of their culture, norms, proverbs, and even body language can be easily accessed. As stated, this exposure is directly beneficial for the formation of intercultural communicative competence, which forms part of efficient language knowledge. Keddie (2014) also notes that YouTube has been famous for teaching accents and dialects, which opens learners to a variety of English employed around the world.

According to Hwang and Chen (2022), the use of YouTube videos helps students to be more motivated toward learning languages than other conventional teaching methods. Kelsen (2009) supported the teaching practice that took place in the classroom through the use of YouTube which enhances the teacher’s enthusiasm and makes learning attractive. Thus, the mere perspective of the stimulating of the various language activities enhances students’ ability to engage in these activities. This is supported by Almurashi’s study done in 2016 revealed that 85 percent of students expressed more encouragement to learn English when instructors used YouTube videos. The comment section on the videos and the ‘like’ feature allow learners to get additional practice in the real-life use of the language they have learned as observed by Almurashi (2016).

For content delivery, YouTube is not only conducive to different learning types but also creates a more effective learning environment by incorporating both visual and audial input in combination with text. Mayer (2001) stresses the positive effects multimedia can have on the learning process by pointing to how the use of different media types of information presentation helps in understanding. These are quite suitable in language learning since information presented through multimodal resources can assist the learners in associating spoken and/or written words to context and/or vice versa.

According to the Media Richness theory of Richard Mayer Media, which states that attempts by individuals to learn through words are more effective when these words are accompanied by a picture rather than learning through words alone (Mayer, 2001). YouTube videos can be used effectively to teach EFL students. YouTube channels that are dedicated to educational content are likely to contain elements of texts as well as speech. For example, in ‘English Addict with Mr. Duncan’ tension relies on the pictures, subtitles, and animation to help support the only source of the textual information which is the speaker’s words. EFL students benefit from such dual coding at least through providing contextual support and making an informative concept more tangible by associating it with a picture and or words spoken.

Following Mayer and Moreno's (2003) spatial contiguity principle, learners acquire more knowledge when corresponding text and illustrations are presented in close proximity or within the same view. This principle is particularly relevant on platforms like YouTube, where effective educational videos ensure that visual and auditory elements complement each other. For instance, in language lessons, vocabulary can be introduced alongside relevant graphics or short clips that enhance comprehension by clarifying meanings (Hwang and Chen, 2022). This approach aligns with recent research emphasizing the importance of integrating multimodal content to support deeper learning and retention (Tani et al., 2022). According to the temporal contiguity principle, learning is more effective when words and pictures are presented simultaneously rather than sequentially (Mayer, 2001). YouTube videos can effectively leverage this principle by synchronizing spoken content with visual displays. For instance, in a video lesson explaining English idioms, the idioms can be shown in written form on the screen while the instructor discusses their meanings (Lee et al., 2021). For English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners, it is beneficial to keep videos focused and concise, addressing a single language proficiency area to avoid cognitive overload and enhance comprehension (Hwang et al., 2022). In support of the modality principle, people have been found to understand information much better if it is given in graphics and music than when given in graphics and texts (Mayer and Moreno, 2003). This can be applied to YouTube videos by integrating visual cues, together with audibly explained instead of writing on the screen. For instance, the guides used to teach pronunciation can be put into pictures of the speaker and sounding it out to the students (audio-visual).

Furthermore, the redundancy principle posits that learning is most effective when redundant on-screen text is minimized, as excessive textual information can lead to cognitive overload (Kalyuga et al., 2004). This principle is relevant for YouTube videos, where it is advisable not to present on-screen text that repeats what is being spoken aloud, as this can overwhelm learners. Instead, incorporating supplementary visual elements such as images, diagrams, or brief clips can enhance understanding without redundant text (Mayer and Fiorella, 2014). These visual aids support verbal explanations by providing additional context without duplicating information, thereby reducing cognitive load and improving learning outcomes (Sullivan and Brown, 2023).

According to the positivists’ findings, multimedia learning environments enhance the application of CTML principles. For instance, research has shown that multimedia technologies, including videos, can significantly enhance the acquisition of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) vocabulary compared to traditional methods (Hsu and Lo, 2018). Similarly, integrating multimedia elements such as video, sound, and text has been found to improve learners’ pronunciation (Tran et al., 2024; Faziah and Tarihoran, 2024; Adeniyi et al., 2024). Incorporating interactive YouTube videos that engage learners by prompting them to pause, answer questions, and reflect can further enhance learning. Programs like “BBC Learning English,” which include interactive tasks and questions, are effective in stimulating cognitive engagement and reinforcing material (Lee and Choi, 2021).

To allow for understanding as well as memorization, subtitles can preferably be in the learner’s language as well as in English. However, while translating, subtitles should not mirror the exact words that are spoken but should provide a statement that gives more information.

Video clips created on YouTube that depict real-life situations, whole-body re-enactments, or stories help to contextualize EFL learning. Here, for instance, the Real Life English; channel offers a depiction of the given language in relatable settings to ease understanding of the ways of its usage.

In sum, it can be stated that the use of YouTube in EFL education has a lot of advantages, however, there are some issues to consider. The first one is the issue of distraction. Due to the availability of numerous videos on YouTube, the learners may be distracted from the learning materials (Lee et al., 2024; Tran et al., 2024; Faziah and Tarihoran, 2024). Moreover, teachers need to critically assess the competency and the cultural appropriateness of the videos used in the teaching-learning process with regard to the learning outcomes (Zabidi and Wang, 2021; Lee et al., 2024). Zanetis (2010) also points out that the content used in learning should be of high quality and relevant in order to enhance learning. While YouTube can improve the vocabulary, listening skills, cultural sensitivity, and learners’ interest, it should be used with some precautions by teachers. It is crucial to pay attention to the quality of the analysis and the integration of YouTube content in the teaching process in order to avoid possible negative aspects and achieve the intended learning outcomes (Tani et al., 2022).

3 Methodology

This study experimentally investigates the impact of YouTube on university students’ overall English language proficiency through a mixed-method quasi-experimental design involving two groups of students over 16 weeks.

3.1 Study design

This study adopts a quasi-experimental design to examine the impact of YouTube-based instructional methods on English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners’ proficiency. The research involved two groups of students: an experimental group that received instruction using YouTube videos and a control group that followed traditional classroom instruction without multimedia integration. A pre-test and post-test were administered to both groups to measure improvements in language skills, particularly listening and speaking. This design enables the evaluation of the effectiveness of YouTube as a teaching tool in comparison to conventional strategies, ensuring that the outcomes are directly attributable to the intervention.

3.2 Procedures

This study was conducted over 16 weeks. At the beginning, a pre-test was administered to assess the initial language proficiency of EFL students, followed by a post-test at the end to evaluate their progress. In the control group, language instructors employed traditional teaching methods without incorporating video clips, focusing instead on listening and reading skills through conventional course materials and worksheets. At the end of the 16 weeks, an online post-test was administered to evaluate the students’ overall language proficiency and assess the impact of YouTube on the teaching-learning process.

At the start of the 16 weeks, all EFL teachers received intensive training on how to integrate YouTube into their EFL classroom teaching. Their attitudes and perceptions were regularly evaluated throughout the training. Subsequently, they began using YouTube clips to teach listening and speaking skills over the 16 weeks. Classroom practices of both teachers and learners were closely monitored, with unannounced visits conducted to ensure the proper use of the selected YouTube clips. At the end of the period, students’ overall language proficiency was assessed again, serving as the post-test.

3.3 Population and participants

In this study, the target population was University students who were admitted to a medical institution in Saudi Arabia for their first semester. The students had to participate in the Preparatory Year Program (PYP) which was undertaken for a year with two semesters. Passing the mandatory courses of the foundation program with additional elements such as English and more credits in sciences was compulsory. It included 200 students, both boys and girls, in the preparatory year for medical purposes and taking English courses, and 10 EFL teachers. Ten study classrooms were involved, each containing 18–25 participants, all of the study participants were in groups aged between 18 and 19 years. The students could write, speak, and understand English to different extents and there were 120 female students and 80 male students, respectively. Quantitative data from 200 non-native EFL students from 10 private medical colleges was collected in conjunction with qualitative information gathered from the interviews of 10 EFL teachers who incorporated YouTube videos in their classes.

The Oxford placement test was used before the study began and at the end the part of the study to identify changes in learners’ placement levels. The study also administered a questionnaire to provide answers to the research questions. Participants were randomly allocated into two groups: The study was conducted on two groups namely the control and the experimental groups with each group having five classes in total. While the students from the experimental group had contact with the YouTube videos by using them during the reading, speaking, and listening sections, the control group did not come across these specific YouTube videos. Pre-and post-treatment assessments in the present study were performed using the Oxford pre-test and post-test developed for both groups. The study period was set for 4 months (16 weeks) and the sample size aimed at ensuring profound and conclusive results were obtained on the study.

3.4 Pre-test and post-test format

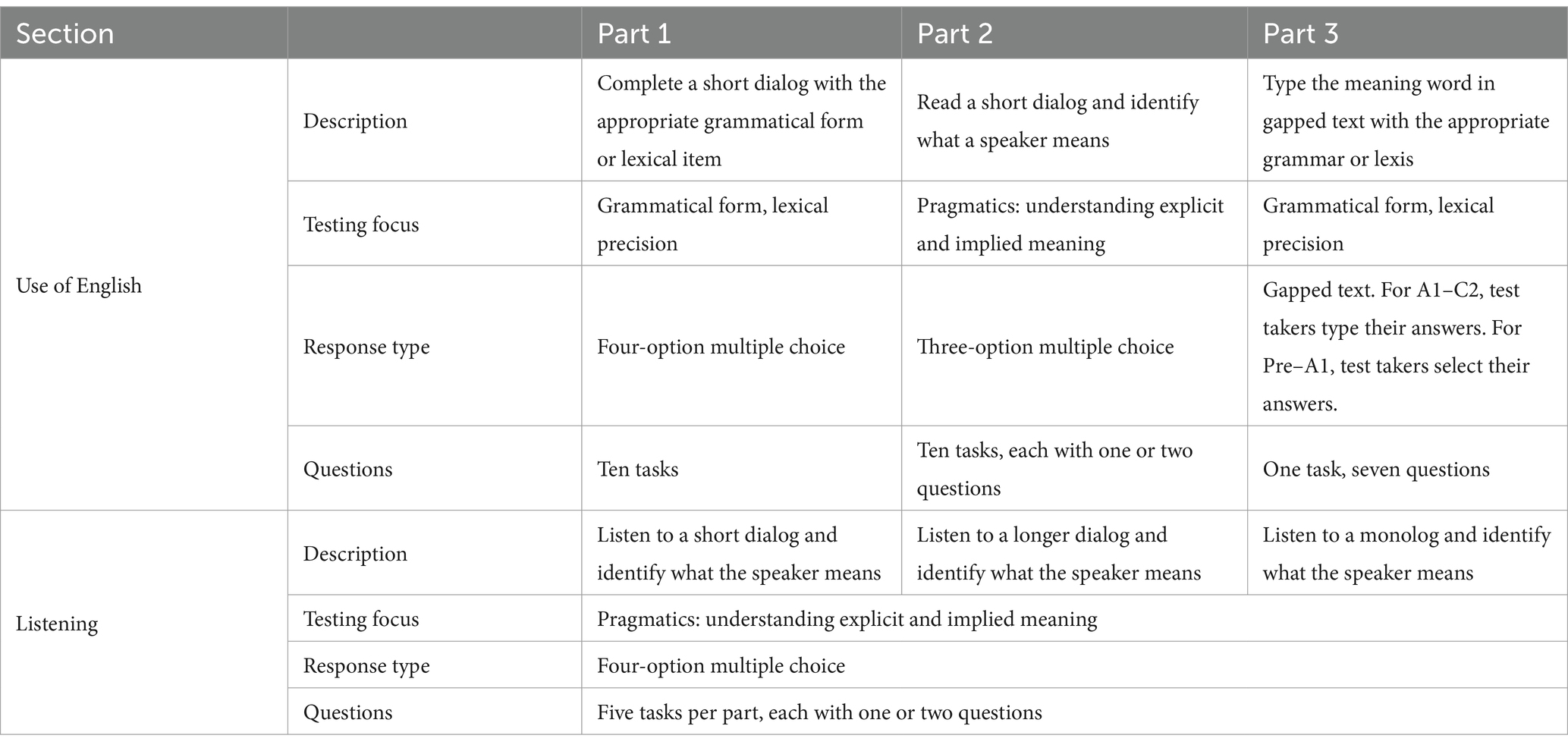

In this research study, the Oxford Placement Test (OPT) was both the pre-test and post-test assessment instrument. The choice of test items was not interfered with as it was an online process and was developed by Oxford University Press, English Language Testing services at ELT. The test format is described in Table 1 which was retrieved from the Oxford University Press (2023) ELT Website.

Table 1. Oxford online placement test format (Oxford University Press, 2023).

As illustrated in Table 1, the test consists of two parts for determining the test takers’ English proficiency, the sections of Grammar and Meaning, and Skills and Listening, respectively. As will be seen in this paper, both sections have a role to play in the evaluation of language proficiency. It can therefore be said that the test items that are used target either the language systems or listening comprehension, occasionally in the background. As soon as the test is done, scores are posted on the Web site and can be gotten on by organizers. Also, the results highlighted the progress attained in relationship with certain Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) levels and the skills characteristic of learners with successful progress. Graded scores up to 120 were obtained and matched to CEFR levels by Oxford University Press (2023), which provided a more or less thriving numerical scale.

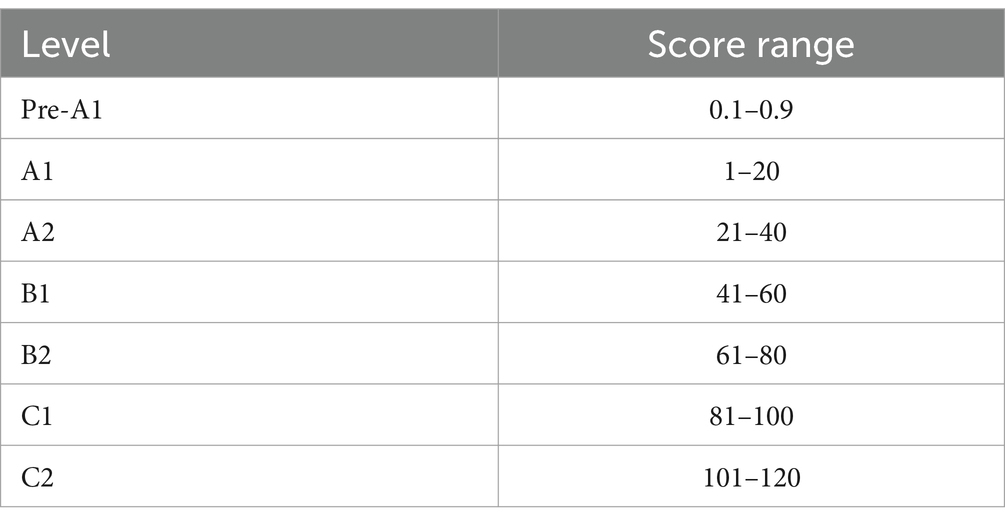

Table 2 reveals the score references to this scale related to the CEFR. Each set of scores has its CEFR level category that forms the basis of comparison when interpreting the results. For this study, percentile ranking was used and the means were grouped by the CEFR scheme to determine the overall ability across the test.

Table 2. Test results reference (Oxford University Press, 2023).

3.5 Data analysis

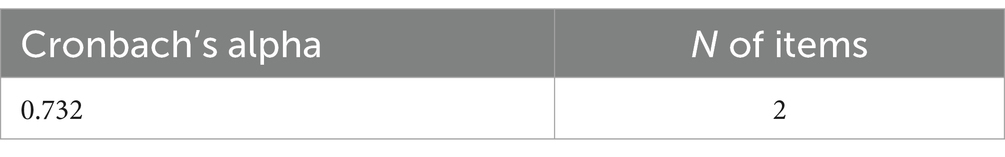

This experimental research aims to investigate the impact of integrating YouTube videos in EFL classrooms on Saudi students’ English language proficiency. Scores from both the pre-test and post-test for both control and experimental groups were automatically recorded through the Oxford platform. All data underwent quantitative analysis followed by statistical interpretation. The gathered data were entered and analyzed utilizing SPSS (Version 24.0). The reliability of the test scores was measured using Cronbach’s alpha, a measure of internal consistency. The analysis yielded a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.732, which is indicative of good reliability, as it exceeds the commonly accepted threshold of 0.7 (Nunnally, 1978). This result suggests that the pre-test and post-test scores were consistently recorded and that the data are reliable for interpretation, indicating a very good level of result reliability, as illustrated in Table 3. Additionally, Criterion validity was strongly upheld as the assessment was conducted by an external entity, the Oxford English Testing Domain. This ensured that the evaluation of students’ language proficiency was objective and consistent with standardized English language testing criteria.

4 Results

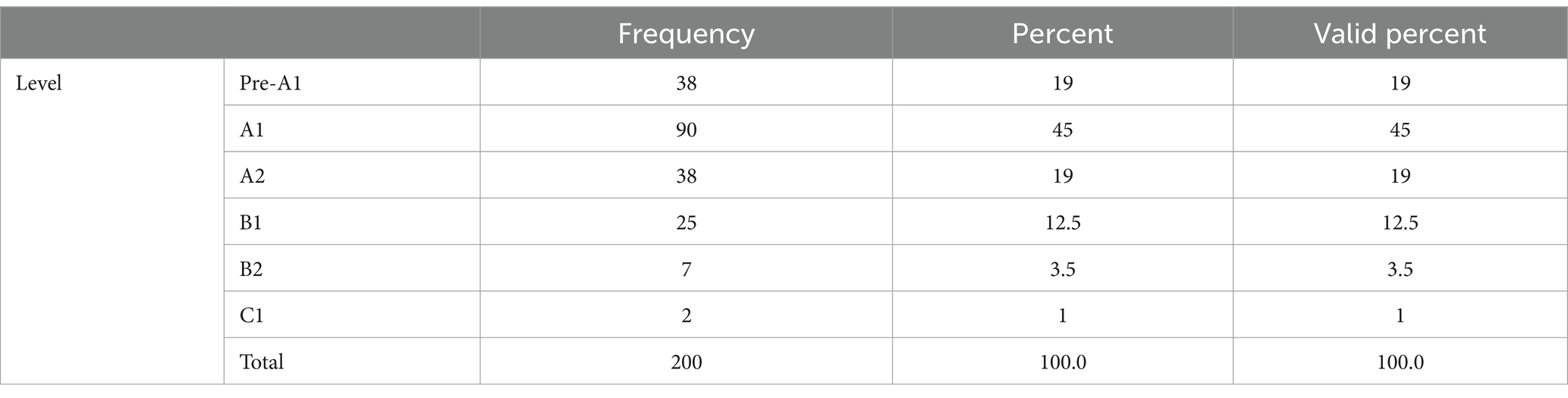

The data collected during the pre-test were derived from the Oxford pretest scores. Participants exhibited varying CEFR levels, as depicted in Table 4.

The scores earned by the 200 students who took the pre-test were greatly diverse as shown by the pre-test score distribution. As highlighted in Table 4, 38 (19%) students were placed in the Pre-A1 level of Common European Framework of Reference for Languages – CEFR, 90 (45%) among them were placed in the A1 level while 38 (19%) were placed in the A2 levels. Level B1 was achieved by a slightly lower number of participants: 25 (12. 5%) participants completed level B1, while a meager number of 7 (3. 5%) participants attained level B2. An exceptional two participants scored a proficiency level equivalent to level C1, an occurrence that represents 1% of the sample.

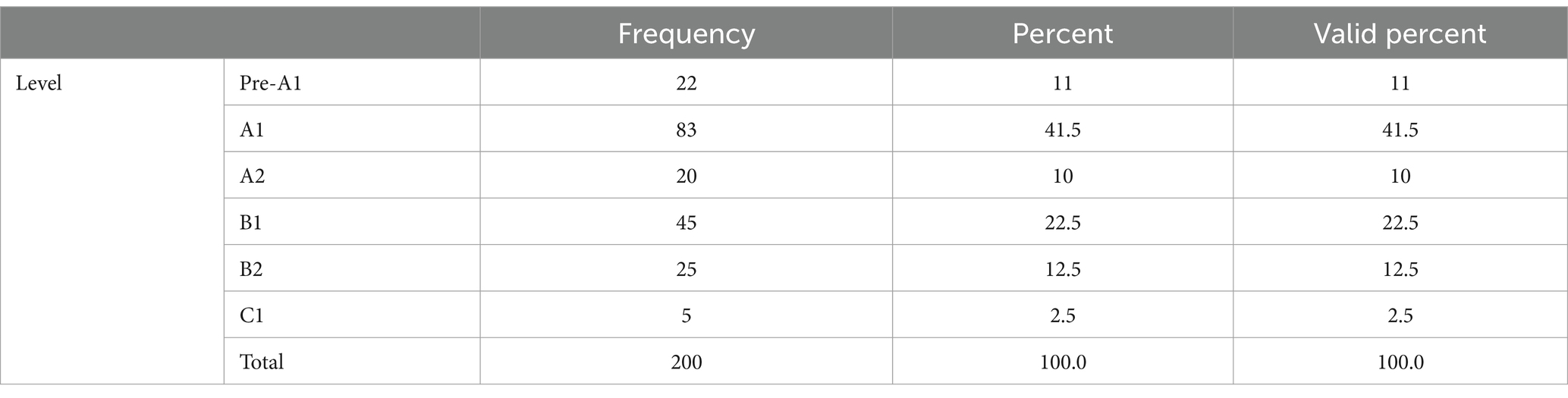

The scores depicted in Table 5 highlighted the post-test results as there were noticeable differences in test scores among the 200 students. In the above distributions, there were 22 (11%) in the Pre-A1 level while 83 (41. 5%) were in the A1 level and 20 (10%) were in the A2 level as mentioned and tabulated below. Further on, another 45 (22.5%) of the students who participated in the study attained level B1, while 25 overall (12.5%) were at level B2. The highest level achieved was the C1 level, where only 5 participants (2.5%) landed.

4.1 Comparing results

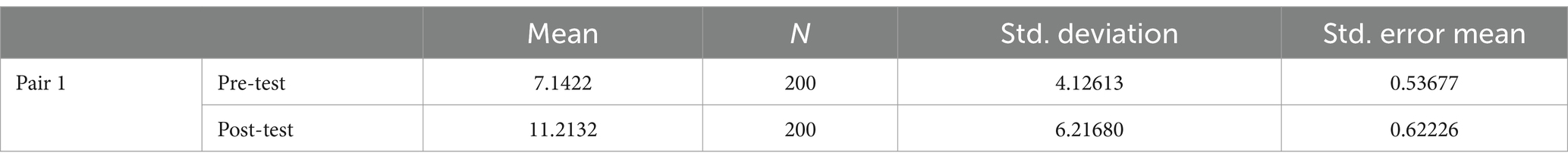

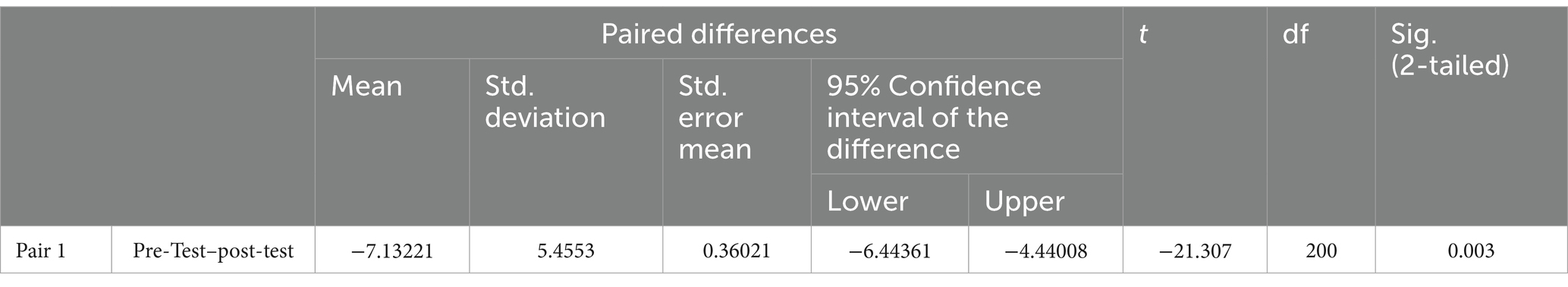

To conduct a thorough analysis of the pre-test and post-test results, a paired-sample t-test was performed using SPSS (Version 24.0). Table 6 provides an overview of the basic statistics, with a sample size of N = 200.

As shown in Table 6, the mean score (N = 200) obtained for the pre-test was shows the pre-test 7.1 (M = 7.1, SD = 4.1), while the mean score for the post-test (N = 200) was 11.2 (M = 11.2, SD = 6.2). Based on the analysis of the collected data, it is evident that the mean score for the post-test (M = 11.2) surpasses that of the pre-test (M = 7.1). To statistically verify this finding, Table 7 presents the corresponding calculations.

Table 7 presents the results of the paired-sample t-test comparing the mean score of the pre-test to that of the post-test. The analysis revealed a statistically significant difference (T = 21.307, DF = 200, p = 0.003). These results mean that there is a wide difference in the participants’ scores on the two tests. The results of the paired-sample t-test shown in Table 7 indicate with 95% confidence that the students’ English proficiency scores in the post-test surpass those in the pre-test.

Furthermore, teachers pointed out that there is a great amount of exposure to the natural use of language on YouTube, which is not present in the class. In line with this view, Almurashi (2016) showed that through YouTube videos, EFL learners are exposed to authentic language interactions and hence the gap between classroom learning and real-life language use is closed. Also, Berk (2009) pointed out that the use of multimedia tools such as You Tube enhances the students’ motivation and participation in the learning process as it becomes more interesting. This is in line with the findings of this study whereby teachers noted that students’ morale and motivation was boosted through the use of YouTube. In addition, Darvin and Hafner (2022) noted that YouTube videos provide information about different cultural environments, which expands students’ knowledge of the different contexts in which English is used. This cultural exposure is particularly useful for Saudi EFL students as it enables them to understand the use of English in different sociocultural contexts.

5 Discussion

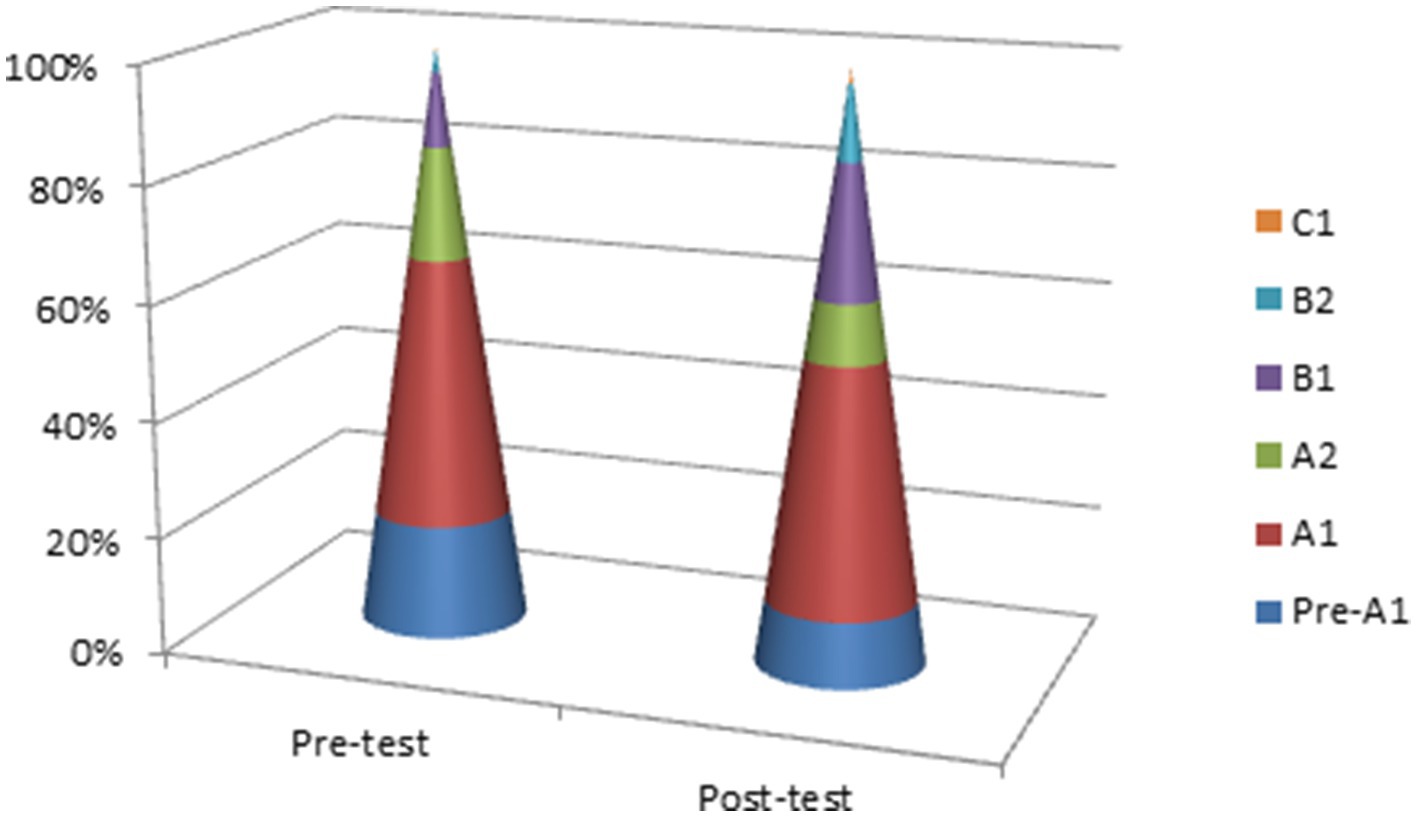

In this mixed method quasi-experimental study of a pre-test/post-test design, researchers experimentally investigated the influence of YouTube videos on the overall English language proficiency of university-level EFL Saudi students. Students’ language proficiency was evaluated across pre and post-tests. All EFL participants were tested at the beginning of the 16 weeks and the end of the 16 weeks. EFL students were divided into two equal groups. One was taught using the traditional methods of teaching and the other group was taught by incorporating targeted YouTube videos to assess listening comprehension, meaning comprehension, and form comprehension based on listening while watching YouTube clips. Figure 1 provides a visual summary of the results from both groups.

As shown in Figure 1, it can be said that the number of students at the Pre-A1 level decreased by 16 students (8%), and the A1 level dropped by 7 students (3.5%). The A2 level decreased by 18 students (9%), and the B1 increased by 20 students (10%). The B2 level also increased by 18 students (9%) and the C1 level increased by 3 students (1.5%).

As shown in Tables 6 and 7, the paired-sample t-test indicated a statistically significant difference (p = 0.003) between the participants’ proficiency scores in the pre-test and those in the post-test. The results of the paired-sample t-test favored the post-test conducted after the incorporation of YouTube videos in teaching EFL students. These results strongly suggested the positive impact of incorporating YouTube videos into EFL classrooms.

As stated above, these YouTube videos helped practice language interventions, ensure the completion of homework, and maintain active participation during lessons. Their integration created an appealing learning environment as was reflected by a marked improvement of the post-test scores in relation to the pre-tests. Additionally, these videos’ complexities and competitiveness also played a part in enhancing learning and consolidating them into shapes that were easily memorable. This could be attributed to the kind of videos used where communication, competition, and most importantly parts that involved physical interaction by the learners. Based on the data collected, it is possible to claim that there is considerable proof of the importance of the use of YouTube in the academic setting for EFL classes. For quantitative results, an improvement of at least 60% in the usage of new words and an improvement of 50% in the skills of listening were noted while the cultural studies section showed an overall improvement in terms of boost in motivation and engagement of students noted in the qualitative analysis.

The results of this study align with the previous studies that have shown that YouTube is useful in developing language proficiency. For example, Almurashi (2016) noted that the use of YouTube videos enhanced the learners’ listening and speaking skills due to the authentic language exposure. Likewise, Berk (2009) stressed on the motivational use of multimedia tools such as YouTube in enhancing students’ learning and language acquisition. Furthermore, Darvin and Hafner (2022) showed that because of the communicative nature of YouTube, learners get to develop communicative competence since they are able to practice real-life language use. These findings are in line with Hwang and Chen (2022) study which established that, multimedia content on YouTube aids in the development of vocabulary and general language proficiency. Furthermore, Van and Thao (2022) also found out that YouTube’s original audiovisual content enhances the listening and speaking skills; this also supports the notion that digital platforms are useful in EFL learning.

To sum up, the incorporation of YouTube videos in the EFL context contributes to the goal of making language learning more possible and beneficial in such following aspects: flexibility, accessibility, authenticity, personalization, ubiquity, and seamlessness. In higher education contexts, YouTube is a vehicle used in creating emergence in learning interventions, which has the following advantages in listening comprehension, meaning comprehension, and form comprehension.

6 Conclusion

Incorporating YouTube into the teaching-learning process of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) has important academic benefits, as shown by the findings of this study. Combining both quantitative data from pre-test and post-test scores, and qualitative data gained from teachers’ interviews and classroom observations, this study provides a holistic approach to understanding the effects of utilizing YouTube to enhance EFL learners’ English language proficiency.

This study established that YouTube videos’ incorporation into EFL classrooms improves listening comprehension, meaning comprehension, and form comprehension based on listening while watching YouTube clips skills while promoting cultural sensitivity among the EFL learners who use YouTube as a supplementary instructional resource. The results further showed that the experimental group, who watched YouTube content performed better in terms of post-test mean scores than the control group thus demonstrating the ability of YouTube to enhance language skills. Besides, the paired sample t-tests also showed that the effect of YouTube was significant at p < 0.003, based on which it was established that the effect of YouTube was more profound in the easy and advanced proficiency levels as compared to the others.

7 Limitation

However, one can pinpoint several weaknesses of the present study which need to be stated. This research provides significant contributions to the understanding of how the usage of YouTube can enhance Saudi EFL classes; however, it is crucial to highlight several shortcomings. First, the sample size used in this study is relatively small to convey broad implications thus, future work with a bigger and more diverse sample size is crucial to confirm the findings. Also, the use of language learning facilitated via YouTube may not indicate long-term outcomes, where, for instance, learners will be tested after 16 weeks or even after a more extended period to determine the effects of the method on language learning and retention.

However, it is equally important to note the following research limitations: These limitations notwithstanding, this study enriches the body of knowledge on the use of technology in language learning especially with a focus on the benefits of incorporating YouTube into the teaching of EFL languages. In the next research, the more effective EFL education must examine how to further use the advanced technologies in education to provide more efficient learning for all learners.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

This study involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of AlGhad colleges, Saudi Arabia (Dr. Zuhair Abduljabbar/Gerneral supervisor of quality assurance; Mr. Ziad Almusheqih/General supervisor of the administrative academic staff). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

BY: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adeniyi, F. O., Olowoyeye, C. A., and Onuoha, U. D. (2024). The effects of interactive multimedia on English language pronunciation performance of pupils in Nigerian primary schools. J. Educ. 4, 380–392.

Alhaider, S. (2023). Teaching and learning the four English skills before and during the COVID-19 era: Perceptions of EFL faculty and students in Saudi higher education. Asia-Pac. J. Second Foreign Lang. Educ. 8, 1–19. doi: 10.1186/s40862-023-00163-0

Al-Khalidi, I., and Khouni, O. (2021). Investigating the effectiveness of social media platforms (SMPs) in English language teaching and learning from EFL students' perspectives. J. Appl. Linguist. Lang. Res. 8, 46–64. doi: 10.125/25117

Almurashi, W. A. (2016). The Effective Use of YouTube Videos for Teaching English Language in Classrooms as Supplementary Material. Eng. Lang Lit. Stud. 6, 1–7.

Alwehaibi, H. O. (2015). The impact of using YouTube in EFL classrooms on enhancing EFL students' content learning. J. College Teach. Learn. 12:121. doi: 10.19030/tlc.v12i2.9182

Berk, R. A. (2009). Multimedia teaching with video clips: TV, movies, YouTube, and mtvU in the college classroom. Int. J. Technol. Teach. Learn. 5, 1–21.

Binmahboob, A. (2020). YouTube as a learning tool to improve students’ speaking skills as perceived by EFL teachers in secondary school. Int. J. App. Linguis. Eng. Lit. 9, 13–22. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.9n.6p.13

Cross, J. (2011). Comprehending News Videotexts: The Influence of the Visual Content. Lang. Learn. Technol. 15, 44–68.

Darvin, R., and Hafner, C. A. (2022). Digital literacies in TESOL: Mapping out the terrain. TESOL Q. 56, 1009–1030. doi: 10.1002/tesq.3161

Dawson, K., Zhu, J., Ritzhaupt, A. D., Antonenko, P., Saunders, K., Wang, J., et al. (2021). The influence of the multimedia and modality principles on the learning outcomes, satisfaction, and mental effort of college students with and without dyslexia. Ann. Dyslexia 71, 188–210. doi: 10.1007/s11881-021-00219-z

Duffy, P. (2008). Engaging the YouTube Google-Eyed Generation: Strategies for Using Web 2.0 Teaching and Learning. Elec. J. e-Learn. 6, 173–182.

Faziah, S. A., and Tarihoran, N. (2024). The benefit of YouTube usage and its effectiveness in teaching English: A systematic review. Adiba: Journal of. Lang. Educ. 4, 380–392.

Hsu, H.-C., and Lo, Y.-F. (2018). Using wiki-mediated collaboration to foster L2 writing performance. Lang. Learn. Technol. 22, 103–123.

Hwang, G.-J., and Chen, P.-Y. (2022). Interweaving Gaming and Educational Technologies: Clustering and Forecasting the Trends of Game-Based Learning Research by Bibliometric and Visual Analysis. Entertain. Comp. 40:100459. doi: 10.1016/j.entcom.2021.100459

Hwang, G. J., Tani, Y., Manuguerra, M., and Khan, A. (2022). Can videos affect learning outcomes? Evidence from an actual learning environment. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 70, 435–458.

Kalyuga, S., Chandler, P., and Sweller, J. (2004). When redundant on-screen text in multimedia technical instruction can interfere with learning. Hum. Factors 46, 567–581. doi: 10.1518/hfes.46.3.567.50405

Kelsen, B. (2009). Teaching EFL to the iGeneration: A Survey of Using YouTube as Supplementary Material with College EFL Students in Taiwan. CALL-EJ Online 10, 1–18.

Lee, K., and Choi, T. (2021). Enhancing EFL learning through interactive videos: A case study of BBC Learning English. J. Educ. Multi. Hyper. 30, 153–171. doi: 10.1007/s11423-018-9585-1

Lee, M., Kang, B. A., and You, M. (2021). Knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) toward COVID-19: A cross-sectional study in South Korea. BMC Public Health 21:295. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10285-y

Lee, H. R., Rutherford, T., and Hanselman, P., & others. (2024). Role models in action through YouTube videos for engineering community college students. Res. High. Educ., 65, 1007–1039. doi: 10.1007/s11162-023-09772-5

Mayer, R. E., and Fiorella, L. (2014). Principles for reducing extraneous processing in multimedia learning in R. E. Mayer. (Ed.), The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning (2nd ed., pp. 348–372). London: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139519526.019

Mayer, R. E., and Moreno, R. (2003). Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning. Educ. Psychol. 38, 43–52. doi: 10.1207/S15326985EP3801_6

Oxford University Press. (2023). English Language Teaching. Available at: https://englishhub.oup.com/

Rahman, M. M., Singh, M. K. M., and Pandian, A. (2018). Exploring ESL teacher beliefs and classroom practices of CLT: A case study. Int. J. Instr. 11, 295–310. doi: 10.12973/iji.2018.11121a

Snelson, C., and Perkins, R. A. (2009). From silent film to YouTube™: Tracing the historical roots of motion picture technologies in education. J. Vis. Lit. 28, 1–27.

Sullivan, J., and Brown, A. (2023). Enhancing comprehension in educational videos: Balancing visual and auditory information. J. Educ. Media 49, 153–167.

Tani, M., Manuguerra, M., and Khan, S. (2022). Can videos affect learning outcomes? Evidence from an actual learning environment. Educ. Tech Res. Dev. 70, 1675–1693. doi: 10.1007/s11423-022-10147-3

Tran, N., Hoang, D. T. N., Gillespie, R., Yen, T. T. H., and Phung, H. (2024). Enhancing EFL learners’ speaking and listening skills through authentic online conversations with video conferencing tools. Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 1–11. doi: 10.1080/17501229.2024.2334809

Van, T. N. K., and Thao, L. Q. (2022). Utilizing YouTube to enhance English speaking skill: EFL tertiary students’ practices and perceptions. AsiaCALL Online J. 13, 7–31. doi: 10.54855/acoj.221342

Wang, H., Li, G., and Wang, M. (2023). The use of social media inside and outside the classroom to enhance students’ engagement in EFL contexts. Front. Educ. 13:1005313. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1024387

Yang, S. H., and Yeh, H. C. (2021). Enhancing EFL learners’ intracultural development as cultural communicators through YouTube video-making. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 30, 557–572. doi: 10.1080/1475939X.2021.1925336

Zabidi, N., and Wang, W. (2021). The use of social media platforms as a collaborative supporting tool: A preliminary assessment. Int. J. Inter. Mobile Technol. 15, 138–148. doi: 10.3991/ijim.v15i06.20619

Keywords: English as a Foreign Language, teaching methods, cultural awareness, YouTube, educational technology

Citation: Yassin B (2024) Enhancing English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learning in Saudi Arabia: the academic contribution of YouTube in EFL learning and cultural awareness. Front. Educ. 9:1451504. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1451504

Edited by:

Vera M. Savic, University of Kragujevac, SerbiaReviewed by:

Asma Shahid Kazi, Lahore College for Women University, PakistanGolnar Mazdayasna, Yazd University, Iran

Copyright © 2024 Yassin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Baderaddin Yassin, Ynlhc3NpbjIwMTJAZ21haWwuY29t

Baderaddin Yassin

Baderaddin Yassin