- 1Education Futures, University of South Australia, Adelaide, SA, Australia

- 2College of Education, Psychology, and Social Work, Flinders University, Bedford Park, SA, Australia

- 3Faculty of Education, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

This research investigated the details and effects of a short online Professional Learning Program designed to develop teacher education students’ knowledge about how to promote self-regulated learning (SRL) in the classroom. The Program was based on a new framework for how teachers can promote SRL, the SRL Teacher Promotion Framework (SRL-TPF), which focused on the promotion of SRL strategies, students’ knowledge about learning, and students’ metacognition. It consisted of seven modules describing the different SRL promotion types and SRL capabilities and ways to promote them through teacher talk and action. Modules included written information and video examples taken from observations of real classrooms, which were used to illustrate the transfer of SRL theory to instructional practice. Each module concluded with several assessment items. During the Program the participants, 91 teacher education students, were asked to use a simplified scoring system based on the SRL-TPF to code lesson transcripts taken from classroom observations. The results showed that by the end of the program over 85% of the participants were able to provide teacher instructions that included explicit SRL promotion and/or promoted students’ SRL knowledge. Our study contributes to research findings on teacher education students’ knowledge of SRL, their promotion of SRL to students, and the contribution of short duration SRL professional development.

1 Introduction

Self-regulated learning (SRL) is a significant conceptual framework that has been developed within the education research literature for several decades (Bjork et al., 2013; Panadero, 2017). Typically, SRL is defined as “the process of systematically organizing one’s thoughts, feelings, and actions to attain one’s goals” (Usher and Schunk, 2018, p. 19) in relation to learning. An SRL framework focuses on actions learners can initiate and control while involved in learning. As noted by Winne and Hadwin (1998) there is a focus in the SRL framework on the actions of the self to organize the regulating of learning. Bjork et al. (2013, p. 436) noted that the construct of SRL “implies that the student wants to regulate his or her learning” and therefore actions learners undertake to manage their learning require attention by themselves and their teachers, particularly in relation to the ways in which students approach and work on their learning (Butler, 2021).

SRL definitions make clear that it is multidimensional (Boekaerts, 1997; Panadero, 2017; Pintrich, 2000; Winne, 2011; Zimmerman, 2008).

Lawson et al. (2023) recently identified seven categories of regulative activity types—regulation influenced by beliefs about learning, by emotion, by motivation, by cognition, by metacognition, regulation of the learning environment, and regulation emerging from social interaction This paper focuses on several of these regulative activity types – in particular—knowledge and beliefs about learning, motivation and emotion, cognition, metacognition, and resource management.

A recent meta-analysis of the correlates of under-achievement reinforces the importance of SRL for effective learning (Fong et al., 2023). A meta-analysis of studies by Dignath et al. (2023, p. 32) on interventions focused on the monitoring element of metacognition concluded that “learners who are encouraged to engage in some form of monitoring show improved performance, strategy use, and motivation with respect to their learning.” However, other research suggests that students may not have access to a variety of effective SRL tactics and strategies (Azevedo et al., 2008; Pintrich, 2000). Winne (2014) suggested that this situation was likely due to the infrequent teaching of these strategies in regular classrooms.

The positive effects of the dedicated SRL strategy interventions suggest that many of the students taking part in these interventions either were previously not aware of the strategies or were not aware of when or how to use the strategies effectively. This also implies that it is likely that explicit attention to these strategies by teachers would also show positive effects for such students. However, there is evidence that teacher attention to these student needs may be less widespread than desirable.

Findings in observational research involving elementary and middle school teachers in the United States by Moely et al. (1992), Spruce and Bol (2015), and Hamman et al. (2000) all showed infrequent teaching of SRL strategies. The same pattern of findings emerged in research on German primary and secondary teachers who showed very little direct instruction of SRL strategies, with instances of promotion being mostly implicit and focused on cognitive strategies (Dignath and Büttner, 2018). Similarly, Vosniadou et al. (2024) found very little promotion of explicit strategies as well as of knowledge and beliefs about learning and about SRL in Australian secondary school classrooms.

In this paper we argue for the explicit and detailed promotion of SRL strategies, knowledge about SRL, and metacognition. The rationale for explicit and detailed teacher promotion of knowledge about SRL and SRL strategies is clear. If students are expected to take effective control of their learning, then they need to know how to exercise such control. And if students’ knowledge of SRL is not well-developed then teachers have clear opportunities in lessons to explicitly promote such knowledge. However, as noted above, findings from research examining teacher promotion of SRL has shown that such explicit and detailed SRL promotion is not widespread. In reviews of this research Dignath and Mevarech (2021) and Dignath and Veenman (2021) concluded that although research did provide examples of indirect strategy promotion by teachers who arranged supportive classroom environments, the explicit promotion of SRL strategies is relatively infrequent. Although studies have shown that practising teachers and teacher education students can be supported to set up more explicit strategy promotion (Askell-Williams et al., 2011; Gillies and Khan, 2009), this has not become common practice in classrooms, and other studies have shown little positive impact of SRL professional development on teachers’ SRL promotion (Heirweg et al., 2021; McKeown et al., 2019).

This pattern of research findings suggests that because promotion of SRL strategies by practising teachers during lessons is critical for students’ learning, teacher education programs should ensure that the participants involved in these programs have both good knowledge of SRL and know how to effectively assess and explicitly promote this knowledge in the students they will teach. During both their teaching practicums and their subsequent teaching these teacher education students will benefit if they know how to assist their students to develop and use effective knowledge of how to manage their learning (English and Kitsantas, 2013; Michalsky and Schechter, 2013; Peeters et al., 2014).

In response to the need for more explicit promotion of SRL strategies by teachers, the need for more, and different, professional development has been a focus for researchers working with teachers and teacher education students. Part of this recent concern has been to give greater attention to the different types of SRL promotion identified in recent research noted above. This need for greater emphasis on explicit promotion of SRL strategies was one of the motivations for the design of the professional development delivered in this study.

The design of the Program described below was based on the arguments above that promotion of SRL strategies during lessons is critical for students, and SRL professional development is needed by teachers for increased SRL knowledge, self-efficacy and subsequent self-regulated teaching (SRT) in classrooms. This implies that teacher education programs should ensure that the education students involved have good knowledge of SRL and know how to effectively assess and promote this knowledge in their teaching practices for the students they will teach.

However, other research raises doubts about the extent to which many teacher education students have achieved such standards of preparation. Research such as that by Panadero (2017) and Moos and Ringdal (2012) have recognized that a lack of SRL training during teacher education may be contributory factors in teachers’ classroom neglect of SRL in their classrooms. In related research Ohst et al. (2015) characterized the German pre-service education students they observed as having fragmentary, disorganized and sometimes inaccurate knowledge about learning. Endedijk et al. (2012) also suggested that programs of teacher education rarely involve adequate stimulation of the development of good quality SRL knowledge, suggesting that such a situation can arise because teaching practicum assignments do not place sufficient emphasis on the SRL knowledge and skill of the teacher education students, but focus more on the actions of the pupils they will teach.

More encouraging is the research showing that teacher education students can be helped to develop greater knowledge about SRL and how to promote it when teaching (Michalsky and Schechter, 2013). The need for this development has been supported by Arcoverde et al. (2020) and Kramarski and Kohen (2017). Michalsky and Schechter (2018) examined the effect on pre-service teachers of instructional situations that involved learning from both problematic and successful experiences. They found that these multifaceted situations led to greater preservice teachers’ promotion of SRL to students than others that did not involve both successful and problematic situations. These studies have pointed to the need for further research on more extensive teaching about SRL to teacher education students and the assessment of effects on the participants’ observed SRL knowledge and use of that knowledge.

One major objective of this study was to provide teacher education students with a professional learning program on the nature of SRL, which included provision of knowledge about ways to effectively promote SRL strategy use in lessons and of ways to promote student metacognition in the classroom (Zepeda and Nokes-Malach, 2021). Despite the findings of meta-analytic research on the importance of metacognitive reflection (Dignath et al., 2008; Dignath and Büttner, 2008; Hattie et al., 1996), its promotion has not been included in frameworks that investigate the direct promotion of SRL, except in the form of the teaching of metacognitive strategies.

The length and context of professional development programs in this area were also issues that emerged in reviewing past research. Peeters et al. (2014) recommended professional development occur using a school-wide approach with all staff contributing to an environment supporting students’ SRL. In many situations, including that of teacher education students who may be on placements in schools for only relatively brief periods, such an approach may not be feasible. Even with a school-wide approach, a one-year school-wide study by Heirweg et al. (2021) showed little positive impact on teachers’ self-efficacy for promoting SRL or on their students’ achievement. Kramarski and Heaysman (2021) proposed that one-year was perhaps insufficient time for desired change and that the teachers involved in Heirweg et al.’s (2021) study lacked skills to transfer the SRL professional development knowledge from general to domain-specific needs. In addition, Kramarski and Heaysman (2021) noted a lack of attention to the need for explicit strategy promotion in the Heirweg et al. (2021), study and in similar professional development research.

For example, Harris et al. (2012) also undertook domain-specific school-based professional development across a period of four to six weeks, and found increased teachers’ SRL self-efficacy and SRL instructional use but less effect on learner outcomes. Conversely, McKeown et al. (2019) drawing from Harris et al., completed a mixed method professional development study, involving two professional development days, in class teaching observations, and support, with a domain-specific randomized trial resulting in positive outcomes for teacher participants and their students. Both Harris et al. (2012) and McKeown et al. (2019) utilized evidence-based professional development of self-regulated strategy (SRSD) in the writing genre yet the outcomes for learners were different. Harris et al. (2012) found that although SRSD led to improvements in genre specific writing elements the overall writing quality did not improve. McKeown et al. (2019) participants however reported positive changes in learners’ writing self-concept, ability, and actions. The lack of a clear pattern in the Harris and McKeown et al. sets of findings suggests that extended time on its own is not associated with effective outcomes for professional development programs and raises the possibility that shorter programs that attend to factors such as explicit promotion of SRL strategies and knowledge should be investigated to see if they could generate positive effects.

Indeed, a recent model of professional development for SRL has proposed the delivery of shorter programs. Kramarski and Heaysman’s (2021) conceptual framework developed Zimmerman’s (2008) three phases of SRL into a spiraled three-step professional development program, differentiating teachers’ as both self-regulated learners and self-regulated teachers, with a final stage focused on the influence of teachers’ self-regulated teaching (SRT) for students’ SRL. This paper draws on Kramarski and Heaysman’s (2021) first stage, teachers’ learning about SRL, and the final stage, teachers promoting SRL for students. We identify the final stage by using the term self-regulated teaching (SRT) in this paper. Each of their study’s phases incorporated self-questioning prompts and generic SRL strategies in the specific domains of, mathematics or language. Their 30-h professional development program incorporating explicit instruction, collaborative learning, role playing, reflection on beliefs and practices, and teaching SRL to students, yielded positive outcomes with teachers SRT improved and their students’ academic results increased.

An objective of the present research was also to provide teacher education students with an even shorter professional learning program, which still provided rich information about the nature of SRL and included an emphasis on the need for explicit SRL promotion and discussion of how such promotion could be done. With respect to length of the program we focused on a duration that might more easily be incorporated into existing teacher education courses.

We also followed the suggestions by Kramarski and Heaysman (2021) that a program of relatively short duration could consider elements of both self-regulated learning and self-regulated teaching. Our focus in this paper has been concerned with both elements. First, we investigated the extent to which teacher education students can develop their own knowledge about SRL, specifically knowing about specific SRL promotion types. Secondly, we focused on how they could modify the design of teaching tasks so that these could be more effective in stimulating SRT activity. Our assessments of test items requiring participants to increase the SRLTP in teacher statements also considered evidence that participants could demonstrate their knowledge of ways in which they could promote SRL to students.

1.1 The present research

The Program presented to participants in this study used innovative methods to create an awareness of the discourse and actions teachers can use in the classroom to help students develop their knowledge of SRL and, SRL strategies. This was done by requiring them to use a scoring guide based on the SRL Teacher Promotion Framework (SRL-TPF) to code a lesson transcript taken from a classroom observation. We reasoned that this activity would make the teacher education students more aware of the specific instructions teachers give students during lessons and how these instances of teacher talk can influence students’ SRL knowledge, beliefs, and learning actions.

The Program was based on the recommendations of the SRL-TPF developed in previous work (Vosniadou et al., 2024) for the direct promotion of SRL in the classroom. The SRL-TPF drew from several theoretical approaches to SRL to analyze classroom teaching and learning approaches (Boekaerts and Cascallar, 2006; Efklides, 2011; Pintrich, 2000; Schunk and Greene, 2017; Winne and Hadwin, 1998; Zimmerman, 2008). More specifically it built on Dignath and Veenman’s (2021) work and the Assessing How Teachers Enhance Self-Regulated Learning (ATES) guide to the analyzing of types of SRL promotion (Dignath-van Ewijk et al., 2013; Dignath and Büttner, 2018; Dignath et al., 2022). For the present study we used a simplified version of the ATES focusing on the three types of SRL promotion and four capabilities shown in Table 1.

As in the ATES guide, the SRL-TPF differentiated explicit from implicit strategy instruction. Explicit strategy instruction was recognized when teachers made their intention to teach a strategy clear to students and described the strategy in detail, using the word strategy or providing a name for it. It is important for teachers to name the strategy they teach because this helps students attend to the details of the strategy, remember it, and increases the likelihood that students will transfer its use to other situations (Brown et al., 1981; Dignath and Büttner, 2018; Veenman, 2013). Implicit strategy instruction involved the instruction of a procedure without using the word ‘strategy’ to describe it or without naming or identifying what was being described as a strategy. In these cases, the teacher was not explicitly making students aware of the strategy.

In addition, the Program introduced two more types of SRL promotion, the promotion of knowledge and beliefs about learning, and metacognitive reflection and support. Previous research approaches have not investigated how teachers promote students’ knowledge about SRL through providing students with information about how learning happens, and they have not identified that having a repertoire of learning strategies is an important SRL promotion type. Talking to students about mathematics anxiety, for example, can help them understand what such anxiety is and how it influences mathematics performance. It can also help them to better understand some of their own negative academic emotions and help them to find ways to control them (Carey et al., 2019; Szucs and Mammarella, 2020).

A third type of SRL promotion identified in the SRL-TPF was metacognitive reflection and metacognitive support. Despite the findings of meta-analytic research on the importance of metacognitive reflection (Dignath et al., 2008; Dignath and Büttner, 2008; Hattie et al., 1996), its promotion has not been previously included in frameworks that investigate the direct promotion of SRL, although it has been included in observation protocols that investigate support of metacognition (Zepeda and Nokes-Malach, 2021). In the SRL-TPF, we used the term Metacognitive reflection to refer to instances during which teachers encourage students to reflect on their knowledge and/or strategies (Brown, 1987; Schraw, 1998; Schraw and Moshman, 1995; Zepeda and Nokes-Malach, 2021). Metacognitive support, on the other hand, was used to refer to instances when teachers reminded students, or helped them think about, their existing knowledge of learning or learning strategies that might be relevant.

The SRL-TPF also considered whether the strategies or knowledge being promoted were domain-general or domain-specific. Knowledge and strategies are domain-specific when they are helpful in one subject area but not in another. For example, knowledge about how to subtract or divide and relevant subtraction or division strategies are useful in mathematics but not in English, as opposed to information and strategies about how to appreciate a poetic device, which might be helpful in English but not mathematics. Domain-specific learning strategies were included in the present framework because their explicit promotion has been associated with learning gains in the subject areas (Brown et al., 1981; Dignath et al., 2008). However, they are not intrinsically related to SRL the way domain-general learning strategies are. Strategies are domain-general when they span across different subject disciplines. They form a widely applicable body of knowledge about how to learn that has been built up by educators, psychologists, cognitive scientists, and neuroscientists and on which learners rely to monitor and control their learning across subject areas. It is important to distinguish domain-general from domain-specific strategies for a better understanding of teacher practices related to SRL.

Regarding SRL capabilities, the SRL-TPF distinguished amongst cognitive, metacognitive, motivational/emotional and resource management capabilities. Cognitive capabilities refer to the knowledge and strategies employed by learners to support information processing during learning. Strategies supporting cognitive capabilities include focusing attention, task analysis, imagery, elaboration, storage, paraphrasing, and rehearsal (Askell-Williams et al., 2011; Paris and Paris, 2001; Vosniadou et al., 2021; Winne, 2017).

Metacognitive capabilities refer to the knowledge and strategies used by learners to plan, monitor, and evaluate their learning. Strategies supporting metacognitive capabilities include planning, checking, and reflecting on one’s learning process and progress (Askell-Williams et al., 2011; Efklides, 2011; Nückles et al., 2009).

Motivational/emotional capabilities refer to the knowledge and strategies used by learners to regulate their motivation for learning. Strategies supporting motivational and emotional capabilities include appropriate goal setting, learning orientation, controllable attributional effort, and emotional regulation (Efklides, 2017; Winne, 2017).

Resource management capabilities draw on knowledge, beliefs, and strategies to manage one’s social and physical environment for learning optimization. Strategies supporting resource management capabilities included recognizing and seeking help when needed, organizing space, resources, and time management for required learning (Pintrich, 2000; Vandevelde et al., 2013).

Three research questions are addressed by this study. These research questions respond to the previously discussed needs for teachers and education candidates to be knowledgeable about SRL and approaches supporting SRT in classrooms for students’ development of SRL skills.

1. How well did the participants understand (a) the information about SRL; (b) the distinction between the different SRL promotion types; (c) the distinction between the different SRL capabilities; and (d) distinguishing domain-specific from domain-general SRL promotion?

2. In what areas were participants successful and unsuccessful in their use of the SRL-TPF to code a lesson transcript?

3. How well did participants apply their knowledge of the SRL-TPF to provide high SRL instruction to students?

4. Was the SRL intervention associated with a change in participants’ confidence in teaching SRL to students?

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Participants

The participants were 91 teacher-education students from two Australian universities, with a median age of 27.8 years. Seventy-seven participants were undertaking a Masters’ degree and indicated they had previous teaching experience, the majority with less than 5 years’ experience. The remaining 14 participants indicated they had no teaching experience and were undertaking a Bachelor of Education (n = 10) or Master of Education (n = 4). The majority of participants (63.7%) could not recall covering Program material in any of their Education courses or professional development. Participants level of teaching experiences or prior engagement with SRL was not considered in data analysis. Participants were recruited through direct email and course announcement appeals. The research was undertaken with approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee of each university. All participants signed an online consent prior to accessing the Program.

2.2 Procedure

Verbal and written poster announcements for the study were made in teacher education courses at two universities. Interested teacher education students scanned a QR code to read the letter of introduction and plain language statement explaining the study. If the teacher education student wanted to participate in the study, they proceeded to sign an online consent form and complete one pre Program item. Program login instructions were sent following signed consent. Participants then completed the Program, consisting of 7 sequential modules at a time or times convenient to them, and multiple logins being possible. Participants could complete the Program in less than 4 h. Participants were excluded from the study if they failed to complete all seven modules and enter at least one response in the post and delayed items. Each module, described in detail in the following section, included activities that could only be attempted on one occasion. At the end of the seven modules, participants completed one post test item and provided Program feedback. Approximately four to six after Program completion participants responded to a delayed item. Participants received a certificate of completion and $30AUD in gift cards.

2.3 Materials

2.3.1 Pre, post and delayed items

One 4-point-scale item identifying participants’ SRT confidence was asked pre, post and approximately 6 weeks following participants’ completion of the Program. The post-test included two additional multiple choices and two free text items seeking feedback on the Program.

One 4-point-scale question was completed by participants to measure their confidence teaching SRL to students. It asked how confident are you that you can teach SRL to your students?

Participants responded to one two-point-scale item related to the program’s usefulness and relevance and one three-point-scale item asking; Have you covered the material in this program in any of your Education topics/courses or professional development courses. Following each scaled item participants had an opportunity to provide further details through a brief description.

2.3.2 The modules

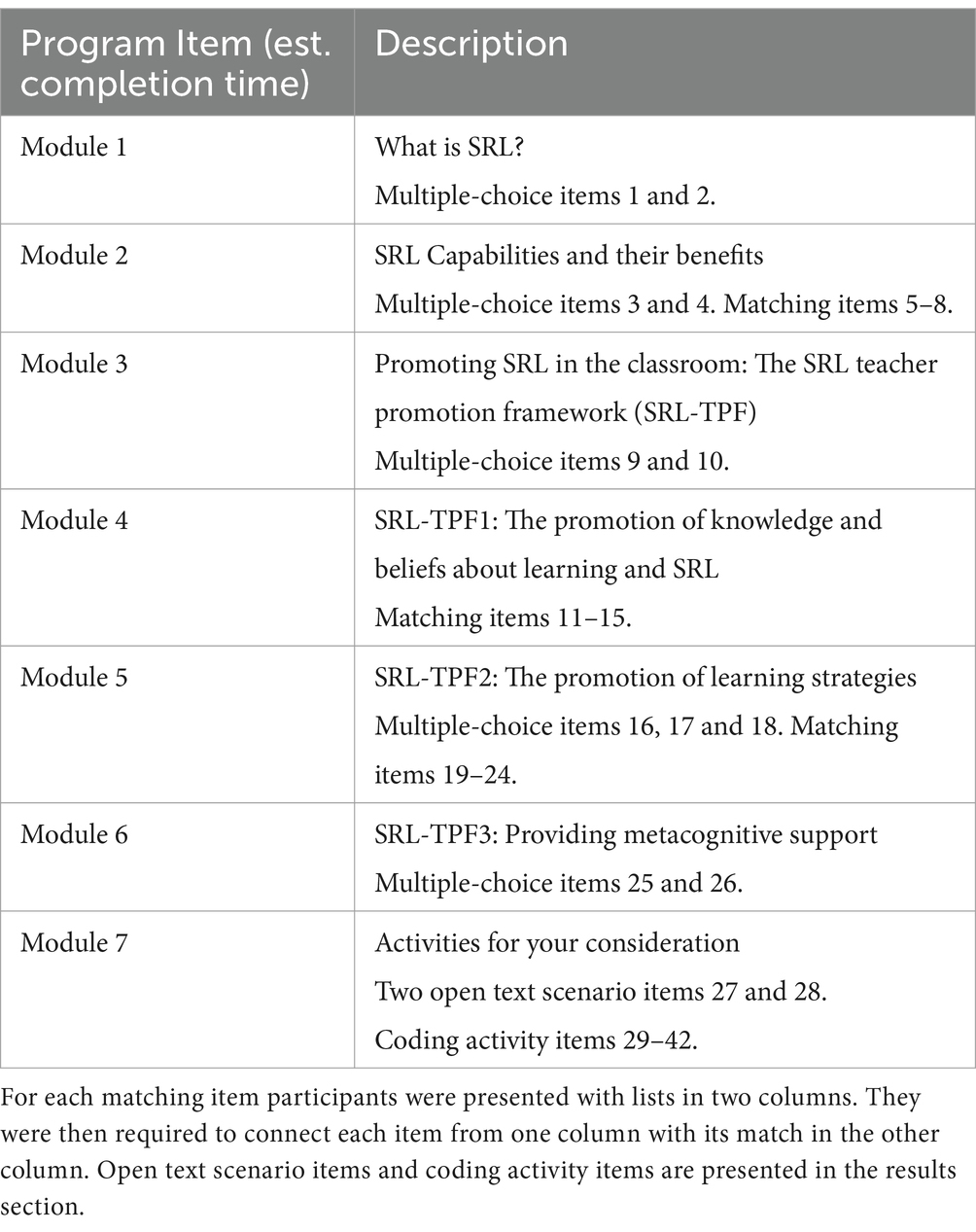

Table 2 describes the contents of the seven modules. Each module included written examples, and three of the seven modules included video examples that illustrated the transfer of SRL theory to classroom contexts. All examples in the modules, including the video excerpts, were taken from observations of real classrooms. Video excerpts showed teachers in standard Australian classrooms instructing students on undertaking specific activities, such as mathematics rules or activating prior knowledge. All modules included activities testing participants’ comprehension of the module’s content. In the final module a lesson transcript was provided for participants to code using the SRL-TPF, and participants used their knowledge of SRL promotion from the Program to complete two scenario activities that required them to transform low SRL scenarios into high SRL scenarios. Participant responses to the module activities were examined to determine whether they could effectively use and apply the SRL-TPF to the excerpts of teacher talk and actions included in the Modules.

Module 1 (approximately 20 min) introduced participants to SRL by defining SRL, outlining its importance to teachers and students, and introducing four SRL capabilities.

Module 2 (approximately 30 min) introduced definitions of implicit and explicit strategy instruction and description of knowledge and beliefs about learning and the benefits of SRL capabilities (cognitive, metacognitive, motivational/emotional, and resource management). Each SRL capability type was defined with written examples for how they might be observed in beginning SRL and skilled SRL learners. For example, cognitive capabilities may be observed in a beginning SRL learner becoming distracted when doing tasks and needing assistance to refocus on the task, whereas a skillful SRL learner finds ways to control their attention and refocus when distracted. The benefits of SRL for academic performance were described, along with explanation of the significance of teacher promotion of SRL capabilities.

Modules 3 to 6 were dedicated to the SRL-TPF and its use. Module 3 (approximately 30 min) explained how SRL capability development in learners may be supported through teachers’ explicit attention to the words and actions they used in their class lessons to directly or indirectly promote SRL. The forms of SRL promotion and SRL capabilities (Table 1) were explained with connection to examples from lessons.

Module 4 (approximately 30 min) focused on the promotion of knowledge and beliefs about learning characteristic of self-regulatory activity, including the belief that learning activity can be regulated or managed by the learner. For example, utilizing cognitive modeling or explicitly discussing SRL strategies such as resource management and motivational strategies. Videos and written examples of classroom practices and implementation approaches for SRL were provided to participants. Videos of teaching from prior research in Australian classrooms were used in discussion of classroom implementation of SRL activities and promotion.

Module 5 (approximately 40 min) drew attention to the promotion of learning strategies to enhance learning through domain-general and domain-specific strategies and provided further examples of implicit and explicit strategy promotion. Videos and written examples of classroom practices were included to support participants’ recognition of these concepts in classroom contexts.

The focus for module 6 (approximately 30 min) was on metacognitive reflection and metacognitive support through prompting students to use their existing knowledge and beliefs in ways that require the evaluation of their thinking. Teacher-talk statements, a video of classroom practices, and a lesson transcript excerpt were presented to support conceptual application to classroom contexts.

Module 7 (approximately 60 min) provided four classroom scenarios demonstrating opportunities for teachers to adjust their instructional language to increase promotion of SRL capabilities in students. Participants were then presented with two low SRL scenarios and tasked with rewriting these to transform them into high SRL scenario examples.

2.4 Module assessment items

Multiple-choice questions, matching activities, coding activities, and an open text activity were used to test participants comprehension of Program modules. Table 2 shows the placement of comprehension items within the Program. Throughout the Program there were 11 multiple-choice items, 15 matching activities, one two-part open text activity, and one coding activity.

2.5 Data coding

Multiple-choice, coding and matching items received a score of 1 when correct and 0 when incorrect. Module open text items were scored on a scale of 0 to 5 and 0 to 6 using a coding guide. Two researchers rated a sample of open text item responses and discussed issues arising from their coding trials. Where necessary coding definitions were revised, and further coding trials were run until substantial agreement was achieved (84% with a Cohen’s k of 0.68). Coding was then completed by one researcher. The post multiple choice items were scored 1 when answered yes and 2 when answered no, and open text items were coded by one researcher.

3 Results

3.1 Research question 1: how well did the participants understand (a) the information about SRL; (b) the distinction between the different SRL promotion types; (c) the distinction between the different SRL capabilities; and (d) distinguishing domain-specific from domain-general SRL promotion?

Results from assessment items undertaken following engagement with information provided in modules 1 and 3 of the SRL-TPF showed most participants had a sound understanding of SRL. Module 1 focused on defining SRL and module 3 focused on SRL promotion. 82.8% of participants demonstrated understanding of SRL and almost all participants understood the significance of SRL promotion by correctly identifying how teachers could promote students’ SRL. Overall participants’ understanding of SRL information provided in the SRL-TPF was strong with the average response across 4 items being 90.65%.

3.1.1 Distinguishing different SRL promotion types

Participants were mostly successful (80.77%) in identifying distinctions between implicit and explicit SRL promotion and identifying statements supporting students’ metacognitive reflection with an average of 80.77% correct in three test items. Almost all participants correctly identified when a provided statement was an example of explicit strategy promotion (93.9%) and most correctly distinguished the statement that was not an example of metacognitive support and reflection (70.7%). A statement with no connection to SRL promotion was correctly recognized by 83.5% of participants. However, when asked to match a statement to an SRL strategy they were mostly (52.7%) incorrect in recognizing the statement as being metacognitive.

3.1.2 Distinguishing different SRL capabilities

Participants were tested multiple times on their understanding of the distinctions between SRL capabilities. When presented with two short descriptions of teacher actions participants were mostly successful (81.3%) in distinguishing SRL capabilities. Almost all participants, average 96.23%, were successful in matching the SRL capability with its definition in three test items. When presented with teacher talk statements, however, participants difficulties in understanding the distinction between different SRL capabilities was evident; in seven test items the average correct responses was 81.29%. Resource management (91.9%) and motivational/emotional (85.35%) capabilities were most easily identified by participants while identification of cognitive capabilities (60%) and metacognitive capabilities (74.7%) proved the most challenging for participants.

3.1.3 Distinguishing domain-specific from domain-general SRL promotion

Participants understanding of domain-general and domain-specific SRL learning strategies was tested in two items in Module 5. Most participants correctly distinguished the domain-general statement (85.9%) but when tasked with identifying a domain-specific statement, from a series of four provided statements, significantly less participants were able to do so correctly (61.6%). These results indicate further attention is needed within the Program to support participants’ understanding and recognition of domain-specific and domain-general strategy promotion.

3.2 Research question 2: in what areas were participants successful and unsuccessful in their use of the SRL-TPF to code lesson transcripts?

A coding activity in Module 7 presented participants with a mathematics lesson transcript consisting of teacher and student talk. The transcript was structured into seven sections, each section requiring participants to code for SRL strategy and SRL capability. To support participants who were not mathematics teachers the transcript did not focus on specific mathematical procedures. The average percentage of participant correct responses across the seven sections for SRL strategy was 51.1% and 54.1% for SRL capability.

Considering the participants’ SRL strategy responses, most successfully identified explicit strategies with results in the two test items ranging from 79.8% to 61.6% correct. Implicit strategies were correctly identified by 62.6% in one test item. Metacognitive support was tested in three items with most correctly identifying it in 2 items 60.6% (average) and only 11.1% correct in 1 item. Knowledge and beliefs promotion was not successfully identified as an SRL strategy by most participants with only 21.2% correctly identifying this SRL strategy in the lesson coding activity.

SRL motivational/emotional capability was the most successfully coded section of the lesson transcript with 83.8% of participants correct. Resource management was successfully coded by 69.7% of participants and most participants, 56.6%, correctly coded metacognitive capability. Cognitive capability was tested on 4 occasions with the average correct responses by participants being 42.1%, and responses ranging from a low of 23.2% to a high of 58.2%.

3.3 Research question 3: how well did participants apply their knowledge of the SRL-TPF to provide high SRL instruction to students?

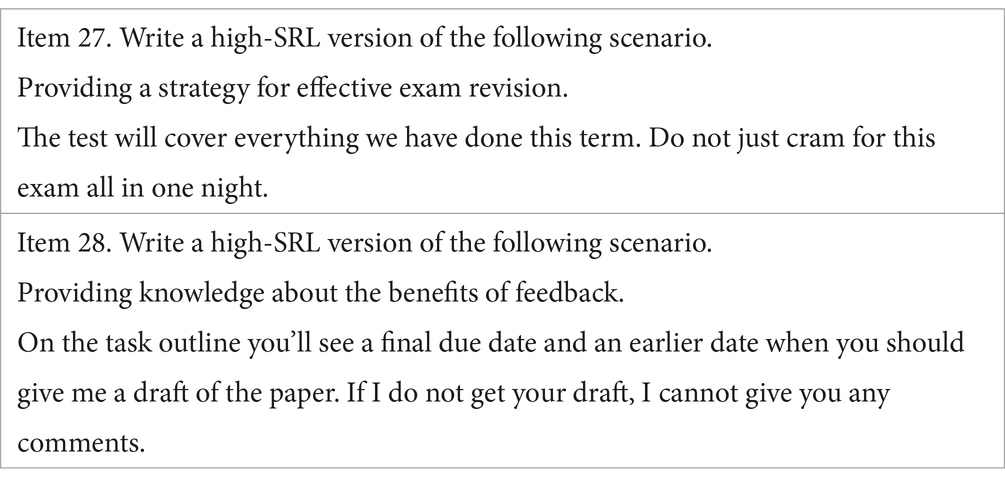

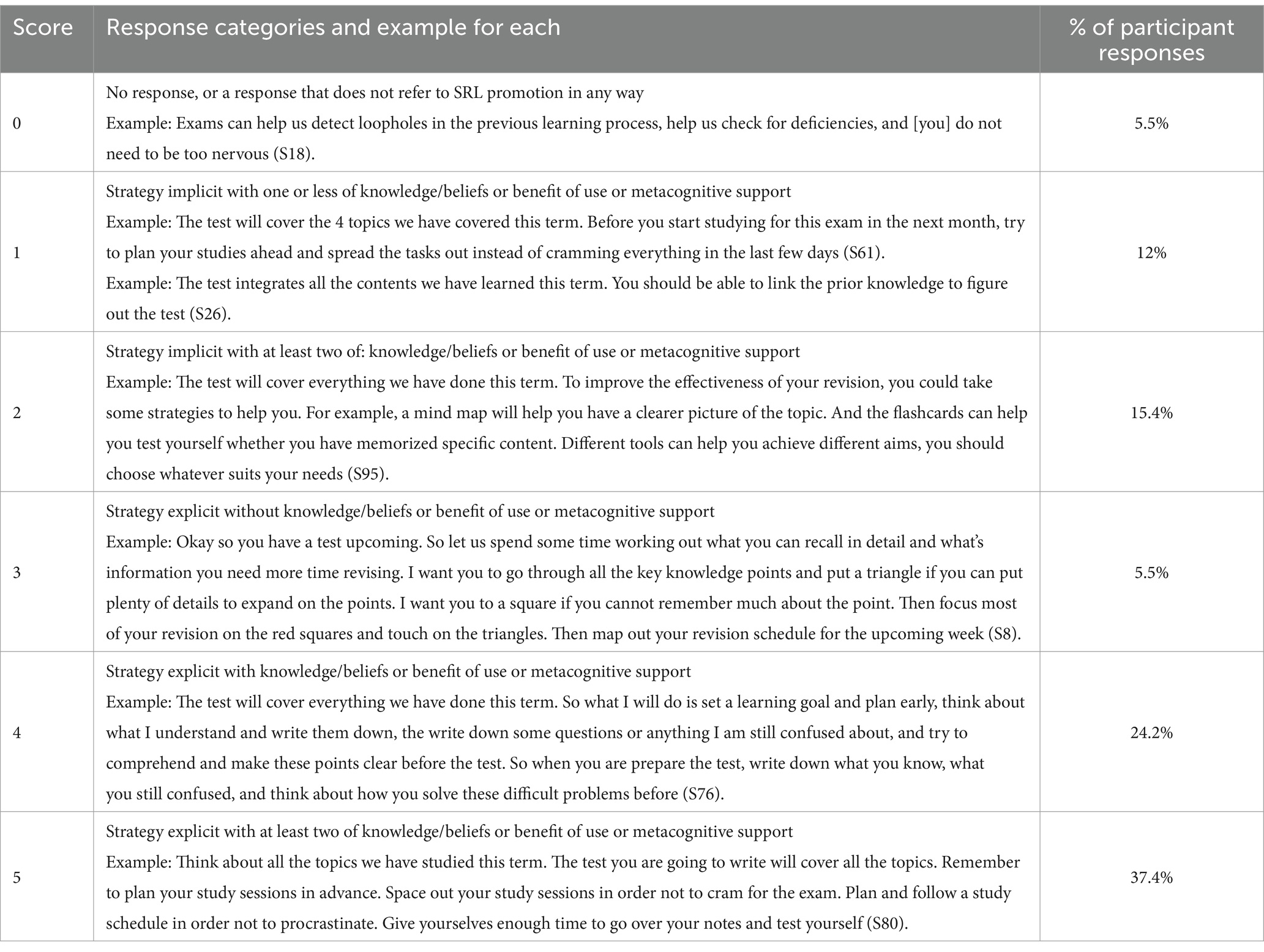

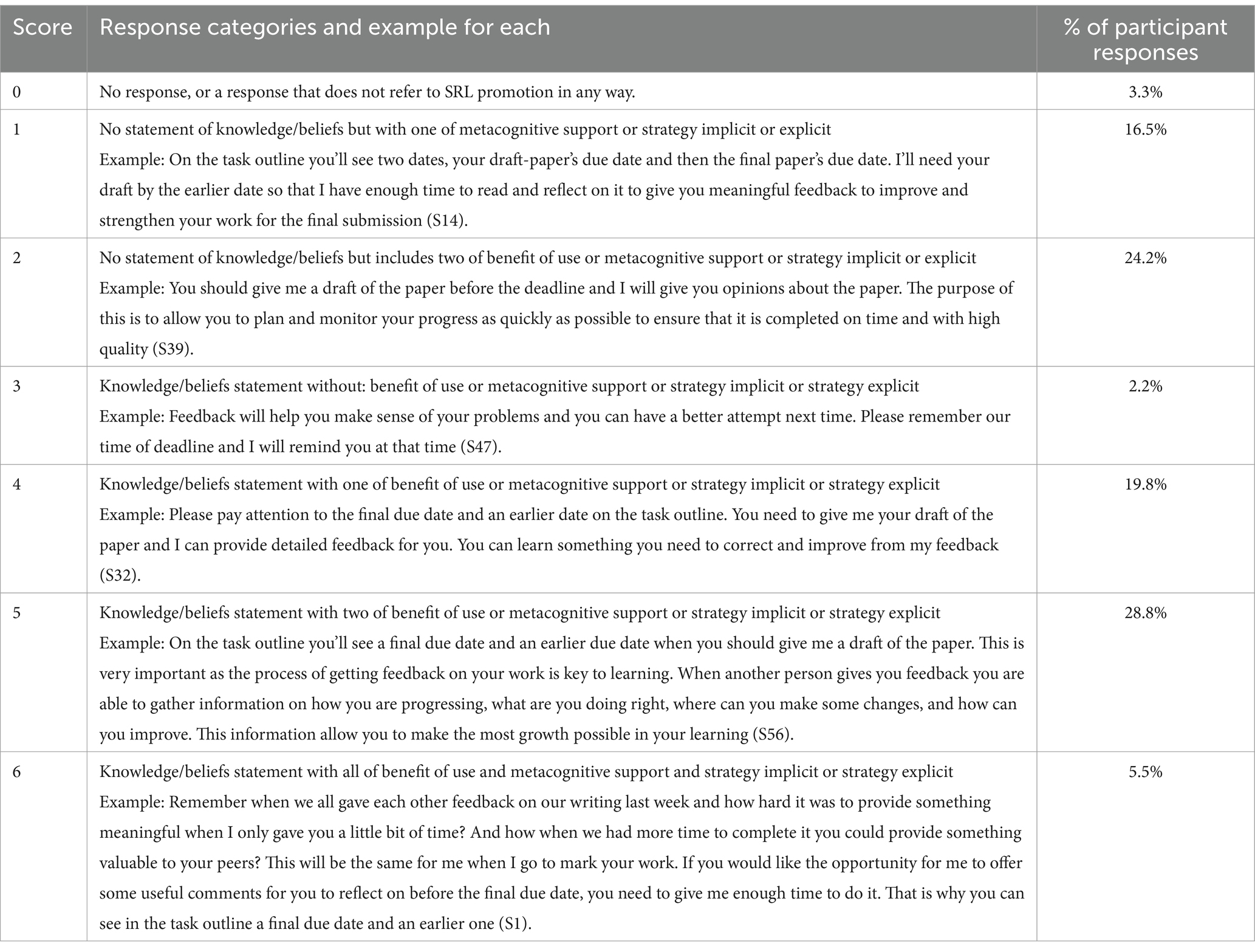

Participants were tasked with writing a high-SRL version for each of two provided low-SRL scenarios. As shown in Table 3 the first SRL statement related to an exam revision task with participants instructed to promote a strategy for effective exam revision in their response. The second statement instructed participants to provide a high-SRL version providing knowledge about the benefits of feedback.

Responses were scored using the SRL-TPF on a 0–5 scale for item 27 and a 0–6 scale for item 28 with zero being scored where there was no response, or a response that did not refer to SRL promotion in any way. Tables 4, 5 show the classification for each score in each activity was varied slightly to recognize the different SRL focus; strategy instruction for the first activity and knowledge and beliefs about learning for the second activity. Examples for each response score are also shown in Tables 4, 5 along with the overall percentage of responses for each score.

Responses to the first scenario (item 27), which required the respondents to provide an explicit strategy for exam revision, showed 67% of the participants provided statements with an explicit SRL strategy, a score of 3 or higher, thus demonstrating an ability to promote high SRL strategies in the classroom (Table 4). Apart from 5.5% of the participants who did not provide an adequate response, the remaining (27.5%) included implicit strategy promotion in their responses.

The second scenario asked participants to provide a high SRL statement promoting knowledge about the benefits of feedback. Just over half of the participants (56%) demonstrated high-SRL strategy promotion, receiving a score of 3 or higher, by incorporating a statement about knowledge and beliefs about learning by using feedback in their response (Table 5). A further 24.2% of participants promoted SRL by including two SRL promotion types, receiving a score of 2, but did not address knowledge and beliefs about learning by using feedback in their response.

Overall most participants did increase the level of SRL promotion in each scenario. In both items most participants utilized the specific SRL promotion type sought. Further, approximately one quarter of participants increased the SRL level of the low SRL statement but did not use the specific SRL promotion type sought in each item.

3.4 Research question 4: was the SRL intervention associated with a change in participants’ confidence in teaching SRL to students?

Participants were asked to rate their confidence on a 4-point scale for teaching SRL to students prior to commencing the Program, immediately after, and then approximately 6 weeks after completing the Program. Results showed a significant increase in participants’ confidence about their capacity for teaching SRL to students immediately following the Program with 87.8% moderately to very confident compared to 39.2% prior to completing the Program. On the delayed item given 4 to 6 weeks after, almost the same percentage (86.8%) were moderately to very confident in teaching SRL to students.

The Program supported participants’ confidence about teaching SRL students. For some participants this was their first exposure to SRL; “this was the first time I heard about SRL” (S54). Participants appreciated the SRL knowledge gained, and examples provided. “The course was informative and helpful especially its examples of how to teach SRL explicitly” (S12). “It provides a detailed framework knowledge about SRL which is really helpful for me to adjust my class and adopt more SRL strategies” (S91). A comment by participant S25 that they “learnt some new strategies and ways to approach facilitating SRL in the classroom” shows their confidence to transfer Program knowledge to SRT classroom practices.

4 Discussion

Developing knowledge and understanding of SRL conceptual frameworks is essential for teachers’ and teacher education students’ ability to transfer concepts into practice (Woolfolk and Murphy, 2001). SRL professional development for teachers and teacher education students has been found to positively impact participants’ self-efficacy in relation to SRL understanding and SRT practices, and learner outcomes benefit when this is the case (Arcoverde et al., 2020; Kohen and Kramarski, 2017; Michalsky and Schechter, 2013; Peeters et al., 2014; Perry et al., 2006). Our research aimed to develop a Program that would improve teacher education students’ knowledge about SRL and about how to promote SRL in the classroom through SRT practices.

The Program was based on a novel conceptual framework for SRL promotion, the SRL-TPF, that distinguished three promotion types – SRL knowledge, SRL strategies and specific SRL capabilities. An innovation of the Program was the positioning of participants to use a scoring guide based on the SRL-TPF to critically examine a lesson transcript. A goal was to increase participants’ awareness and confidence about how teachers’ discourse and actions through SRT practices can support the development of students’ SRL capabilities. Results from the post test demonstrated achievement of this goal with a 44.7% (n = 47) increase in participant’s confidence about teaching SRL to students. Further, our program was noticeably short when compared with other professional development programs for teacher education students. In a synopsis of SRL professional development studies, Ciga et al. (2015) identified only two, of 12, that considered the professional development impact on student teachers’ learning. These two were the longest interventions, each running for 6 months, with both reporting the significance of mentoring discussions and modeling in developing student teachers’ metacognitive awareness and teaching practices. Our Program did not include mentoring discussions and the only modeling provided was in the form of several videos of classroom SRL practices. Since Ciga et al.’s (2015) review we are aware of two subsequent SRL studies, in addition to ours, that were specifically designed for student teachers SRL professional development. One, a study by Kramarski and Kohen (2017) involved 28-h, across 14 weeks, and found specific prompts supported preservice teachers’ as self-aware SRLs and noticing of students’ SRL, and that preservice teachers self-regulated teaching actions were supported through lesson design with a focus on SRT. Another, Arcoverde et al.’s (2020) 30-h SRL theory and activities intervention, ran across 5 weeks, and found improvements in teacher education students’ SRL skills and self-efficacy. Our Program, able to be completed in less than a day, was significantly shorter than both Arcoverde et al. (2020) and Kramarski and Kohen (2017).

One of the points of interest with our study was whether it was possible to achieve positive effects on participants’ knowledge of SRL and capacity to promote SRL in the classroom without the need for intensive school-wide programs such as those mentioned above or those shown to be effective in research on writing (McKeown et al., 2019). Our results indicate that a very short Program may support and develop participants’ SRL knowledge and confidence with classroom SRL promotion through SRT. The Program design concluded with activities positioning participants to code a lesson transcript positioning themselves as teachers providing high SRL instruction. Participants were required to apply their knowledge about SRL to analyze a classroom scenario for a teacher’s promotion of SRL to students. Both concluding Program activities have some alignment with research undertaken and proposed by Kramarski and Heaysman (2021, p. 298) “to make SRL processes more explicit…hope[ing] to promote the successful implementation of SRL and SRT in schools.” Our Program demonstrates that teacher education students SRL knowledge and confidence for SRL teaching practices can be supported in professional development programs of far shorter duration than those previously reported.

The findings regarding Research Question 1 show that most participants (90.65%) were successful in understanding the SRL information presented in the SRL-TPF. They correctly defined SRL and distinguished the difference between SRL and self-directed learning. Further, participants showed understanding for identifying SRL promotion in the classroom scenarios and the distinctions among the different SRL capabilities. The data for correct identification of SRL capabilities is more mixed for cognitive and metacognitive capabilities. It appears that the participants understood the importance of SRL and its promotion in general terms, could recognize the definitions of types of promotion and of SRL capabilities and had stronger understanding about resource management and motivational/emotional capabilities than they did of cognitive and metacognitive capabilities. The participants also had stronger understanding of explicit promotion than of implicit promotion and did not show strong understanding of instances of knowledge and beliefs about learning.

Regarding Research Question 2, the coding activity was more difficult for participants than their responses in the comprehension questions. Although participants had previously coded teacher statements for SRL strategy and SRL capability identification with high accuracy in matching activities, this was the first time they were exposed to more complex statements with both strategy and capability elements in the one assessment item. Asking the participants to code data from a lesson transcript required them to not just decide about one item (SRL strategy) but to maintain in memory the details of another (SRL capability) and the coding scheme. This likely increased the load on working memory substantially with several students noting the difficulty of this activity; “I found the last [coding] exercise really difficulty if would be great to have more assistance on how to differentiate between the different SRL promotions and capabilities” (S58). This activity, reinforced by participant feedback, showed that the participants’ recognition of types of SRL strategy promotion and which SRL capabilities were being promoted would benefit from more detailed and extensive attention within the Program. Providing more time and practice would likely develop participants’ understanding of classroom complexities for both SRL strategy promotion and SRL capabilities. Regardless of the failure to obtain 100% accuracy in the use of the scoring system, the coding exercise was important in sensitizing the participants to the kinds of teacher discourse that happens in the classroom relating to the promotion of SRL knowledge and strategies.

Results for Research Question 3 showed that when asked to generate statements related to a strategy promotion 67% of participants provided explicit SRL strategy instruction and of these 37.4% incorporated more than one SRL promotion type in their responses. In this task, these teacher education students successfully transferred Program content knowledge to teaching activities. Thus, many participants successfully transferred general SRL strategies from the Program to increase SRL promotion in classroom scenarios. Our results indicate that it was possible to incorporate both knowledge about SRL and teacher-focused SRT promoting students’ SRL as proposed and undertaken in research by Kramarski and Heaysman (2021).

Research question 4 provided evidence of the Program’s influence on participants’ confidence promoting SRL to students (87.8%). Approximately four to six weeks following Program completion these positive results remained quite stable (86.6%). These results are encouraging given only 36.3% of participants identified engagement with the Program’s SRL content prior to its completion.As a novel conceptual framework, alongside evidence of participants’ confidence for teaching SRL to students through engagement with a very short Program, we recognize its achievements and opportunities for improvements. Participants knowledge, understanding, and distinction of metacognition and cognition and the subsequent promotion of both to students through classroom teaching is an area that would benefit from further development. These and other areas of SRL and SRT knowledge are discussed in the limitations and future research section below.

4.1 Limitations and future directions

Our results provide evidence of participants’ understanding and recognition of SRL strategies and capabilities following a short professional learning program. We believe, as has been consistently shown in other research with interventions focused on one or more SRL strategy, that participants will have positive effects from Program engagement (Butler, 2021; Dignath et al., 2023; Perels et al., 2009). By developing participants’ SRL and SRT knowledge we expect an increase in participants’ self-efficacy for SRL promotion and consequently the likelihood of SRT promotion in their future classroom teaching practices (Butler, 2021; Karlen et al., 2020).

While our Program was not experimental and we acknowledge assessment items may not enable participants’ deeper level of understandings to be identified, our results indicated important areas for redesign of professional learning programs for both teacher education students and practicing teachers. Our results point to a need for giving higher levels of support, and more opportunities, to teacher candidates and teachers in applying knowledge about SRL and its promotion in practical situations within the classes. A possible future extension of the program developed for this study would be to incorporate such practical applications to classroom contexts. In this respect the designers of teacher education programs could provide opportunities for consideration of SRL strategies and their promotion in both courses concerned with the nature of learning, in courses focusing on the teaching of specific areas of the curriculum, and in courses designed to help students prepare and design tasks for use in their teaching practicums. In Australia, such inclusion would contribute toward meeting the federal and state governments explicit requirement for initial teacher education courses to include content regarding the science of learning (AITSL, 2023) and could be expected to transfer to teacher education students’ classroom practices during professional placement experiences. Objective measures, such as observations, of the Program’s effectiveness promoting SRL for SRT could then be implemented. The pattern of our results also may be relevant to programs on SRL that have involved practicing teachers and which have found that teachers have not continued to take up the ideas in their classroom practice (e.g., Nibali, 2017). Presentation of the ideas and development of understanding of these ideas do not appear to guarantee their practical application in lesson design or classroom practice. Recognition of this element as a necessary addition to professional learning programs is needed.

We believe our research is the first to use the SRL-TPF, or a similar coding tool, as an expanded measure of participants’ understanding of SRL theory in practice. Coding a lesson transcript showed that participants were mostly successful. However, future research that requires participants to code lesson activity or statements should increase scaffolding within the task. We further recommend providing immediate feedback for transcript sections to support learners self-monitoring and correction. Immediate feedback would be expected to support participants’ subsequent coding and monitoring of learning as has been shown in Vosniadou et al. (2024).

Our Program involved participants from two Australian universities and did not explicitly address or target teacher education students personal SRL practices, such as the SRL skills they utilize, or involve mentoring, something that has been shown to influence teachers’ confidence with implementation of SRT. While generally effective in supporting the comprehension of SRL capabilities and promotion, it would be of interest in future research to examine the effect of increasing connection of the Program content to wider populations of teacher education students and incorporate personal and classroom practices as recommended by Endedijk et al. (2012). Seeking feedback from participants would benefit future developments of the Program. Strengthening the direct relationship between the theory and personal practices during preparation programs may be expected to further increase the level of SRL promotion in their teaching practice and subsequent teaching.

5 Conclusion

The research developed and evaluated a short online Program to help teacher education students learn about SRL and how to promote SRL to students through SRT. The Program was based on the SRL-TPF which pays attention not only to the explicit teaching of SRL strategies, but also to participants’ promotion of knowledge and beliefs about SRL and the promotion of metacognitive reflection and support. Our research focused on education students’ ability to use our SRL-TPF, including the coding guide and provide high SRL instruction to students in teachers’ SRT. Results showed the Program was mostly effective in helping teacher education students develop detailed knowledge of SRL capabilities, types of SRL promotion and the application of the SRL-TPF to identify SRL strategies and capabilities within a transcribed lesson. The study contributes research findings addressing two components of SRT – knowledge of SRL and knowledge for promoting SRL in students – in SRL professional development of short duration with beliefs about SRL included. In addition, the pattern of our findings points to key issues that should inform the design of future programs of professional learning on SRL and its promotion for teacher education and practicing teachers.

Data availability statement

Datasets are available on request: The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Flinders University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project# 8320) and the University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (Project# 195.4516.1). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

HS: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. ML: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. L-AN-K: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation. SK: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation. SV: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. CM: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. LG: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. EW: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Investigation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was support by the Australian Research Council under Discovery Grant DP190102366 Teaching how to learn: promoting self-regulated learning in STEM classes.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the teacher education students who facilitated this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

AITSL . (2023). Addendum: accreditation of initial teacher education programs in Australia: standards and procedures. Available at: https://www.aitsl.edu.au/deliver-ite-programs/standards-and-procedures (Accessed May 8, 2024).

Arcoverde, Â. R. D. R., Boruchovitch, E., Acee, T. W., and Góes, N. M. (2020). Self-regulated learning of Brazilian students in a teacher education program in Piaui: the impact of a self-regulation intervention. Front. Educ. 5. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.571150

Askell-Williams, H., Lawson, M. J., and Skrzypiec, G. (2011). Scaffolding cognitive and metacognitive strategy instruction in regular class lessons. Instr. Sci. 40, 413–443.

Azevedo, R., Moos, D. C., Greene, J. A., Winters, F. I., and Cromley, J. G. (2008). Why is externally-facilitated regulated learning more effective than self-regulated learning with hypermedia? Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 56, 45–72. doi: 10.1007/s11423-007-9067-0

Bjork, R. A., Dunlosky, J., and Kornell, N. (2013). Self-regulated learning: beliefs, techniques, and illusions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 64, 417–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143823

Boekaerts, M. (1997). Self-regulated learning: a new concept embraced by researchers, policy makers, educators, teachers, and students. Learn. Instr. 7, 161–186. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4752(96)00015-1

Boekaerts, M., and Cascallar, E. (2006). How far have we moved toward the integration of theory and practice in self-regulation? Educational Psychology Review, 18, 199–210. doi: 10.1007/s10648-006-9013-4

Brown, A. L. (1987). “Metacognition, executive control, self-regulation, and other more mysterious mechanisms” in Metacognition, motivation, and understanding. eds. F. E. Weinert and R. H. Kluwe (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum), 65–116.

Brown, A. L., Campione, J. C., and Day, J. D. (1981). Learning to learn: on training students to learn from texts. Educ. Res. 10, 14–21. doi: 10.3102/0013189X010002014

Butler, D. L. (2021). Enabling educators to become more effective supporters of SRL: commentary on a special issue. Metacogn. Learn. 16, 667–684. doi: 10.1007/s11409-021-09282-8

Carey, E., Devine, A., Hill, F., Dowker, A., McLellan, R., and ZSzucs, D. (2019). Understanding mathematics anxiety: investigating the experiences of UK primary and secondary school students. doi: 10.17863/CAM.37744

Ciga, E., Garcia, E., Rueda, M. I., Tillema, H., and Sanchez, E. (2015). “Self-regulated learning and professional development: how to help student teachers encourage pupils to use a self-regulated goal-setting process” in Mentoring for learning. ed. H. Tillema (The Netherlands: Sense Publishing), 257–282.

Dignath, C., Buettner, G., and Langfeldt, H.-P. (2008). How can primary school students learn self-regulated learning strategies most effectively? A meta-analysis on self-regulation training programmes. Educ. Res. Rev. 3, 101–129. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2008.02.003

Dignath, C., and Büttner, G. (2008). Components of fostering self-regulated learning among students. A meta-analysis on intervention studies at primary and secondary school level. Metacogn. Learn. 3, 231–264. doi: 10.1007/s11409-008-9029-x

Dignath, C., and Büttner, G. (2018). Teachers’ direct and indirect promotion of self-regulated learning in primary and secondary school mathematics classes–insights from video-based classroom observations and teacher interviews. Metacogn. Learn. 13, 127–157. doi: 10.1007/s11409-018-9181-x

Dignath, C., Ewijk, R, V., Perels, F., and Fabriz, S. (2023). Let learners monitor the learning content and their learning behavior! A meta-analysis on the effectiveness of tools to foster monitoring. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 35:2. doi: 10.1007/s10648-023-09718-4

Dignath, C., and Mevarech, Z. (2021). Introduction to special issue mind the gap between research and practice in the area of teachers' support of metacognition and SRL. Metacogn. Learn. 16, 517–521. doi: 10.1007/s11409-021-09285-5

Dignath, C., Rimm-Kaufman, S., van Ewijk, R., and Kunter, M. (2022). Teachers’ beliefs about inclusive education and insights on what contributes to those beliefs: a meta-analytical study. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 34, 2609–2660. doi: 10.1007/s10648-022-09695-0

Dignath, C., and Veenman, M. V. J. (2021). The role of direct strategy instruction and indirect activation of self-regulated learning—evidence from classroom observation studies. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 33, 489–533. doi: 10.1007/s10648-020-09534-0

Dignath-van Ewijk, C., Dickhäuser, O., and Büttner, G. (2013). Assessing how teachers enhance self-regulated learning: a multiperspective approach. J. Cogn. Educ. Psychol. 12, 338–358. doi: 10.1891/1945-8959.12.3.338

Efklides, A. (2011). Interactions of metacognition with motivation and affect in self-regulated learning: the MASRL model. Educ. Psychol. 46, 6–25. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2011.538645

Efklides, A . (2017). Affect, epistemic emotions, metacognition, and self-regulated learning. Teachers College Record (1970). 119:13. doi: 10.1177/016146811711901302

Endedijk, M. D., Vermunt, J. D., Verloop, N., and Brekelmans, M. (2012). The nature of student teachers' regulation of learning in teacher education. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 82, 469–491. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8279.2011.02040.x

English, M. C., and Kitsantas, A. (2013). Supporting student self-regulated learning in problem-and project-based learning. Interdis. J. Problem Based Learn. 7:2. doi: 10.7771/1541-5015.1339

Fong, C. J., Patall, E. A., Snyder, K. E., Hoff, M. A., Jones, S. J., and Zuniga-Ortega, R. E. (2023). Academic underachievement and self-conceptual, motivational, and self-regulatory factors: a meta-analytic review of 80 years of research. Educ. Res. Rev. 41:100566. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2023.100566

Gillies, R. M., and Khan, A. (2009). Promoting reasoned argumentation, problem-solving and learning during small-group work. Cambridge Journal of Rducation, 39, 7–27. doi: 10.1080/03057640802701945

Hamman, D., Berthelot, J., Saia, J., and Crowley, E. (2000). Teachers' coaching of learning and its relation to students' strategic learning. J. Educ. Psychol. 92, 342–348. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.92.2.342

Harris, K. R., Lane, K. L., Graham, S., Driscoll, S. A., Sandmel, K., Brindle, M., et al. (2012). Practice-based professional development for self-regulated strategies development in writing: a randomized controlled study. J. Teach. Educ. 63, 103–119. doi: 10.1177/0022487111429005

Hattie, J., Biggs, J., and Purdie, N. (1996). Effects of learning skills interventions on student learning: a meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 66, 99–136. doi: 10.3102/00346543066002099

Heirweg, S., De Smul, M., Merchie, E., Devos, G., and Van Keer, H. (2021). The long road from teacher professional development to student improvement: a school-wide professionalization on self-regulated learning in primary education. Res. Pap. Educ. 37, 929–953. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2021.1905703

Karlen, Y., Hertel, S., and Hirt, C. N. (2020). Teachers’ professional competences in self-regulated learning: an approach to integrate teachers’ competences as self-regulated learners and as agents of self-regulated learning in a holistic manner. Front. Educ. 5. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00159

Kohen, Z., and Kramarski, B. (2017). “Promoting mathematics teachers’ pedagogical metacognition: a theoretical-practical model and case study” in Cognition, metacognition, and culture in STEM education. eds. Y. J. Dori, Z. R. Mevarech, and D. R. Baker, vol. 24 (Switzerland: Springer International Publishing), 279–305.

Kramarski, B., and Heaysman, O. (2021). A conceptual framework and a professional development model for supporting teachers triple SRL SRT processes and promoting students academic outcomes. Educ. Psychol. 56, 298–311. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2021.1985502

Kramarski, B., and Kohen, Z. (2017). Promoting preservice teachers’ dual self-regulation roles as learners and as teachers: effects of generic vs. specific prompts. Metacogn. Learn. 12, 157–191. doi: 10.1007/s11409-016-9164-8

Lawson, M. J., Scott, W., Stephenson, H., Van Deur, P., and Wyra, M. (2023). The levels of cognitive engagement of lesson tasks designed by teacher education students and their use of knowledge of self-regulated learning in explanations for task design. Teaching and Teacher Education. 125. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2023.104043

McKeown, D., Brindle, M., Harris, K. R., Sandmel, K., Steinbrecher, T. D., Graham, S., et al. (2019). Teachers' voices: perceptions of effective professional development and classwide implementation of self-regulated strategy development in writing. Am. Educ. Res. J. 56, 753–791. doi: 10.3102/0002831218804146

Michalsky, T., and Schechter, C. (2013). Preservice teachers' capacity to teach self-regulated learning: integrating learning from problems and learning from successes. Teach. Teach. Educ. 30, 60–73. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2012.10.009

Michalsky, T., and Schechter, C. (2018). Teachers' self-regulated learning lesson design: integrating learning from problems and successes. Teach. Educ. 53, 101–123. doi: 10.1080/08878730.2017.1399187

Moely, B. E., Hart, S. S., Leal, L., Santulli, K. A., Rao, N., Johnson, T., et al. (1992). Teacher's role in facilitating memory and study strategy development in the elementary school classroom. Child Dev. 63:653. doi: 10.2307/1131353

Moos, D. C., and Ringdal, A. (2012). Self-regulated learning in the classroom: a literature review on the teacher’s role. Educ. Res. Int. 2012, 1–15. doi: 10.1155/2012/423284

Nibali, N. (2017). Teaching self-regulated learning: Teacher perspective on the opportunities and challenges [conference presentation]. Australian Association for Research in education (AARE), Canberra, Australia.

Nückles, M., Hübner, S., and Renkl, A. (2009). Enhancing self-regulated learning by writing learning protocols. Learn. Instr. 19, 259–271. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2008.05.002

Ohst, A., Glogger, I., Nückles, M., and Renkl, A. (2015). Helping preservice teachers with inaccurate and fragmentary prior knowledge to acquire conceptual understanding of psychological principles. Psychol. Learn. Teach. 14, 5–25. doi: 10.1177/1475725714564925

Panadero, E. (2017). A review of self-regulated learning: six models and four directions for research. Front. Psychol. 8. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00422

Paris, S., and Paris, A. (2001). Classroom applications of research on self-regulated learning. Educ. Psychol. 36, 89–101. doi: 10.1207/S15326985EP3602_4

Peeters, J., De Backer, F., Reina, V. R., Kindekens, A., Buffel, T., and Lombaerts, K. (2014). The role of teachers’ self-regulatory capacities in the implementation of self-regulated learning practices. Procedia Soci. Behav. Sci. 116, 1963–1970. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.504

Perels, F., Dignath, C., and Schmitz, B. (2009). Is it possible to improve mathematical achievement by means of self-regulation strategies? Evaluation of an intervention in regular math classes. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 24, 17–31. doi: 10.1007/BF03173472

Perry, N., Phillips, L., and Hutchinson, L. (2006). Mentoring student teachers to support self-regulated learning. Elem. Sch. J. 106, 237–254. doi: 10.1086/501485

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). “The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning” in Handbook of self-regulation. eds. M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, and M. Zeidner (San Diego, CA: Elsevier Inc.), 451–502.

Schraw, G. (1998). Promoting general metacognitive awareness. Instr. Sci. 26. doi: 10.1023/A:1003044231033

Schraw, G., and Moshman, D. (1995). Metacognitive theories. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 7, 351–371. doi: 10.1007/BF02212307

Schunk, D. H., and Greene, J. (Eds.). (2017). Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance (2nd ed.). Taylor and Francis.

Spruce, R., and Bol, L. (2015). Teacher beliefs, knowledge, and practice of self-regulated learning. Metacogn. Learn. 10, 245–277. doi: 10.1007/s11409-014-9124-0

Usher, E. L., and Schunk, D. H. (2018). “Social cognitive theoretical perspective of self-regulation” in Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance. eds. D. H. Schunk and A. Greene. 2nd ed (New York: Routledge), 19–35.

Vandevelde, S., Van Keer, H., and Rosseel, Y. (2013). Measuring the complexity of upper primary school children’s self-regulated learning: A multi-component approach. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 38, 407–425. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2013.09.002

Veenman, M. V. J. (2013). “Assessing metacognitive skills in computerized learning environments,” in International handbook of education, eds. R. Azevedo and V. Aleven (New York: Springer), 57–168.

Vosniadou, S., Bodner, E., Stephenson, H., Jeffries, D., Lawson, M. J., Darmawan, I. N., et al. (2024). The promotion of self-regulated learning in the classroom: a theoretical framework and an observation study. Metacognition and Learning. doi: 10.1007/s11409-024-09374-1

Vosniadou, S., Darmawan, I., Lawson, M. J., Van Deur, P., Jeffries, D., and Wyra, M. (2021). Beliefs about the self-regulation of learning predict cognitive and metacognitive strategies and academic performance in pre-service teachers. Metacognition and Learning. doi: 10.1007/s11409-020-09258-0

Winne, P. H. (2011). “A cognitive and metacognitive analysis of self-regulated learning” in Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance. eds. B. J. Zimmerman and D. H. Schunk (New York: Routledge), 15–32.

Winne, P. H. (2014). Issues in researching self-regulated learning as patterns of events. Metacogn. Learn. 9, 229–237. doi: 10.1007/s11409-014-9113-3

Winne, P. H. (2017). “Cognition and metacognition within self-regulated learning” in Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance. eds. D. H. Schunk and J. A. Greene (New York: Routledge), 36–48.

Winne, P. H., and Hadwin, A. F. (1998). “Studying as self-regulated learning” in Metacognition in educational theory and practice. eds. D. Hacker, J. Dunlosky, and A. Graesser (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum), 277–304.

Woolfolk, H. A., and Murphy, P. K. (2001). “Teaching educational psychology to the implicit mind” in Understanding and teaching the intuitive mind: Student and teacher learning. eds. B. Torff and R. J. Sternberg (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates).

Zepeda, C. D., and Nokes-Malach, T. J. (2021). Metacognitive study strategies in a college course and their relation to exam performance. Mem. Cogn. 49, 480–497. doi: 10.3758/s13421-020-01106-5

Keywords: self-regulated learning promotion, teacher education student, SRL strategies, SRL capabilities, knowledge and beliefs about learning

Citation: Stephenson H, Lawson MJ, Nguyen-Khoa L-A, Kang SHK, Vosniadou S, Murdoch C, Graham L and White E (2024) Helping teacher education students’ understanding of self-regulated learning and how to promote self-regulated learning in the classroom. Front. Educ. 9:1451314. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1451314

Edited by:

Slavica Šimić Šašić, University of Zadar, CroatiaReviewed by:

Nina Pavlin-Bernardić, University of Zagreb, CroatiaMarjeta Šarić, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia

Copyright © 2024 Stephenson, Lawson, Nguyen-Khoa, Kang, Vosniadou, Murdoch, Graham and White. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Helen Stephenson, aGVsZW4uc3RlcGhlbnNvbkB1bmlzYS5lZHUuYXU=

Helen Stephenson

Helen Stephenson Michael J. Lawson

Michael J. Lawson Lan-Anh Nguyen-Khoa

Lan-Anh Nguyen-Khoa Sean H. K. Kang

Sean H. K. Kang Stella Vosniadou

Stella Vosniadou Carolyn Murdoch3

Carolyn Murdoch3 Lorraine Graham

Lorraine Graham Emily White

Emily White