- Department of English Studies, Universitat Jaume I, Castellón, Spain

Introduction: This article presents a project-based classroom practice of transformative language teaching and learning for sustainability (TLS). Sustainable Development Goal 10 (SDG10) was approached paying close attention to the use of language in relation to (in)equality-related terms. This use of language is also defended as SDG18 in recent research in a debate about the importance of language use as a transversal sustainable development goal.

Methodology: A task-based methodology is employed to examine students’ perception on functional diversity terms and how their understanding changed throughout the practice developed in the study. Qualitative data in this study are drawn from a group of students (n = 20) who were finishing their degree in English Studies. Students participated in a task to analyze five functional diversity terms (Special Educational Needs, disability, deaf, blind, and Asperger’s). A qualitative research questionnaire asked the participants to reflect on their learning process in this task.

Results and discussion: The report of our findings shows how students developed their lexicographic and conceptual competence regarding FD terms. Results illustrate how TLS transformed students’ concepts and ideas underlying functional diversity concepts and helped promote sustainable language use.

1 Introduction

A key issue in functional diversity is accessibility. The idea of accessibility revolves around how different individuals access information and information tools as well as on making information meaningful and useful. In the case of language teaching and specifically the teaching of lexicography, this is achieved by teaching and learning how to make an informed use of lexis and the elaboration of adequate, useful definitions. Functional diversity is a social construct and in this sense, the use and definition of concepts play a relevant role in our culture. In this study, this meaningful use of language is developed through a teaching proposal approach that promotes transformative language teaching and learning for sustainability (TLS) where the key tools are the development of action competence (Sass et al., 2020) and lexicography as mediation (CEFR Mediation Strategies).

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, adopted in United Nations (2016), states the necessity of “Recognizing that disability is an evolving concept and that disability results from the interaction between persons with impairments and attitudinal and environmental barriers that hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.” This idea points out two important issues:

• Disability is an evolving concept

• The concept results from the interaction between persons with functional diversity and (a) attitudinal barriers and (b) environmental barriers

This recognition that functional diversity is an evolving concept is an important statement when we work with lexicographical sources of information. Lexicography is the practice of creating dictionaries and other lexical databases and is concerned with the study of the meaning, evolution, and function of lexical items. The fact that functional diversity (Romañach and Lobato, 2005) is an evolving concept implies that its definition must be revised and updated in all languages. If we have to consider attitudinal barriers and how these can be reduced or broken down, this will affect how functional diversity (FD)1 is defined and, in turn, definitions will influence how people understand FD. In this sense, it is important to note the importance of sustainability concepts but also where those concepts are presented and to whom they are presented (Weder, 2023; Nayak and Raval, 2024). Different cultures and societies may also have their own definition and understanding of terms related to functional disability (Alduais and Deng, 2022; Cooms, 2023; Shume, 2023). Moreover, people with FD are frequently excluded from participating as informants in the scientific literature even though they are the subject of study (Palacios et al., 2012; Rabang et al., 2023).

The framework for this article is supported by transformative language teaching for sustainability. Within this framework, action competence plays an important role as well as conceptualization as a mediation strategy.

1.1 Transformative language teaching for sustainability

As highlighted in Campoy-Cubillo (2019) and Maijala et al. (2024), in an educational setting it is important to pay attention to teachers’ knowledge of what is accessibility, how to teach it, and how it relates to their subject (also how it relates to a specific degree or specialization in university contexts). In this sense, the present article studies first what a lexicography subject could consider in relation to FD. The basic consideration should be how to define terms that are relevant in sustainability, in our case FD terms. It should also consider the cognitive process and conceptual competence involved in defining such terms (Andreou and Galantomos, 2009; Higginbotham, 1998). Second, the task designed for the classroom project intends to promote Transformative Language Teaching for Sustainability (TLS). TLS is a new didactic model to teaching promoted by the Ethical and Sustainable Language Teaching project (Eettisesti kestävä kielten opetus (EKKO)) at the University of Turku. It studies how the principles of ethics and sustainability can be built in language teaching and pre-service teacher education. Its goal is “to help teachers to find new ways to combine education for sustainable development (ESD) with language teaching”.2

Political and institutional understanding of accessibility in relation to functional diversity in education is an important part of designing an education for all systems based on quality education (Sustainable Development Goal 4) and reduced inequalities (Sustainable Development Goal 10). In the multidimensional relationship of the student with functional diversity with his/her own educational and sociocultural context (Campoy-Cubillo, 2019), one of the smallest units in the system is the classroom, where what is taught and how this is taught matters as much as attending special needs students in the classroom and the relationship among all members of the class (students and teachers).

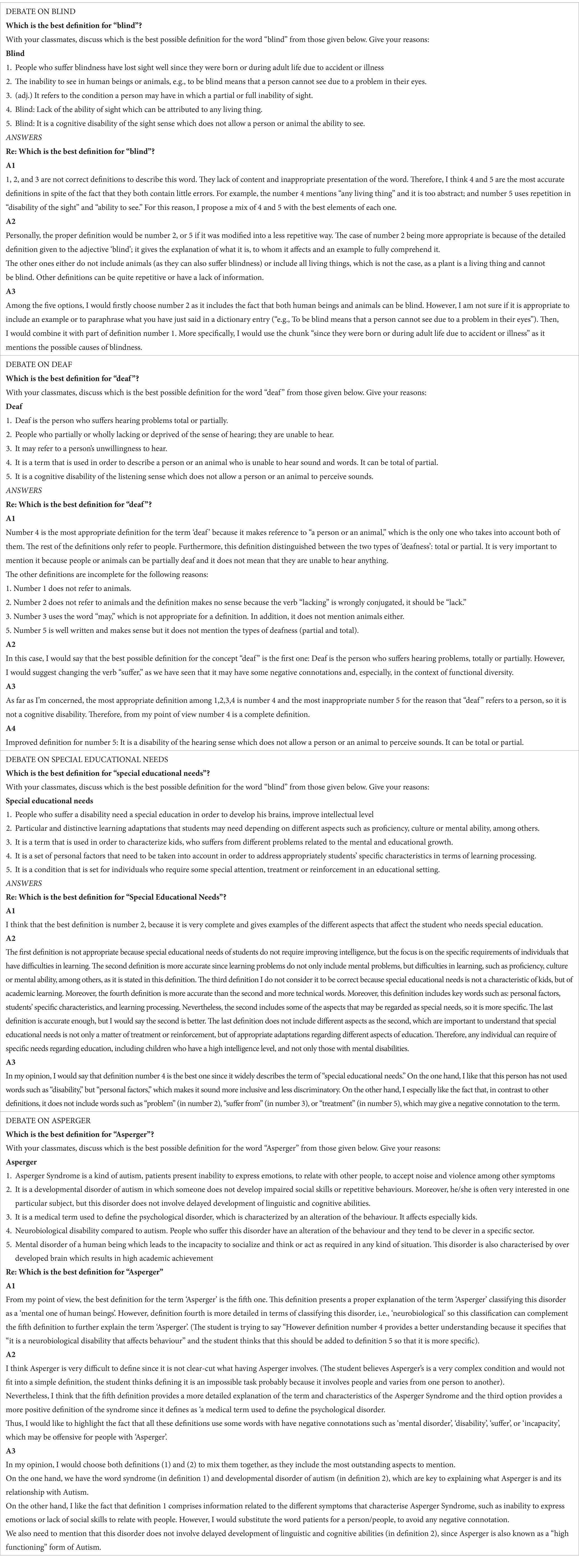

For students who want to become language teachers, it is important to fully understand the meaning of functional diversity terms and how to use them. This is, in my opinion, a fundamental step in understanding accessibility. Teachers should first know what FD terms mean and how to use them before they start thinking of creating materials for the classroom. Steps in accessibility design and implementation are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Steps towards designing and implementing accessibility. In the elaboration of this figure, the following sources have been used: Ideas and concepts as part of accessibility plans: author’s creation. Accessibility: Caldwell et al. (2008); W3C Web Accessibility Principles. Available at: https://www.w3.org/WAI/fundamentals/accessibility-principles/; Accessibility, Usability, and Inclusion, WC3 Web Accessibility Initiative. Available at: https://www.w3.org/WAI/fundamentals/accessibility-usability-inclusion/. User-friendliness: How do you ensure web accessibility and user-friendliness for diverse audiences? Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/advice/1/how-do-you-ensure-web-accessibility-user-friendliness

Thus, recognizing and comprehending concepts and ideas related to accessibility is the first step toward awareness raising in accessibility and for building strategies that are in line with how terms are defined in a given community, country, service, institution, or enterprise. In their proposal for transformative language teaching for sustainability, Maijala et al. (2024) suggest that integration, identification, and awareness-raising should conform to the teaching cycle in Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). They reinforce the relevance of their method stating that there is a lack of language teacher training in sustainability as well as a scarcity of materials. They also claim that action competence needs to be included in ESD. Action-oriented activities increase learner participation and develop important skills such as critical thinking and decision making, which are needed to take action in sustainability-related issues. According to Sass et al. (2020, p. 9):

“Someone is action competent when they are committed and passionate about solving a societal issue, have the relevant knowledge about the issue at stake as well as about democratic processes, take a critical but positive stance toward different ways for solving it, and have confidence in their own skills and capacities for changing the conditions for the better.”

The TLS framework discusses how the language subject differs from other subjects: it represents the goal and, in the communicative approaches, the way to reach this goal. Language is most of the times both the medium and the content. In the case of teaching lexicography, this is particularly so, as lexical items are analyzed for communication purposes. Dictionaries provide lexical item information and not only define those items but also indicate adequate usage of the items, and present selected examples of use. They may also include pragmatic information and visual resources that may provide important additional information (Nied Curcio, 2023).

1.2 Conceptualization as a mediation strategy

Dictionaries are repositories of conceptualizations of a language, and they are concise pieces of work where each word or phrase is analyzed in detail as a dictionary entry. The most relevant part of the entry is the definition of the word or phrase which has the purpose of clarifying meaning. But there are other parts in the entry, such as usage information, pragmatic and cultural aspects, or examples of use. All these parts have a specific weight when dealing with FD terms and are relevant to fully understanding the terms and their use. In dictionaries, special care should be given to sensitive terms, such as those related to FD, and for that reason, the role of lexicographers as mediators is relevant.

When compiling a dictionary or any lexicographical resource, a good lexicographer should construct or mediate meaning and can also mediate from one language to another. This is especially so with sensitive language (Norri, 2018) and the reason why lexicographers may act as mediators of concepts and ideas (Nied Curcio, 2023; Council of Europe (CEFR), 2018). Norri (2018), for instance, examines the treatment of disability and illness terms at length in 20 dictionaries, discussing the different labels and usage notes given in their entries and how they differ as well as the influence of the person-first language in the design of the definitions.

As stated by Nied Curcio (2023, p. 202):

“Of particular concern to the lexicographer as a mediator are mediating a text, mediating communication, and effectively using mediation strategies while describing the meaning of cultural items.” (…) “The mediator—and this is also valid when preparing a lexicographic article—must first select from the vast volume of information available and then transfer it to the target person in a more condensed but still truthful/accurate form.”

1.3 Action competence and the common European framework of reference for languages (CEFR)

In this study, a pedagogical proposal to work with understanding FD concepts and ideas is presented and the results of its implementation are analyzed. Following Sinakou et al. (2019) and the CEFR, the tasks designed for this study were framed in those aspects of the CEFR guidelines that were consonant with the TLS approach, specifically those related to action competence. Those are based on the development of communicative competence, cultural competence, and sharing ideas in the form of forum discussions and reflections; project-based learning (dictionary project); discovery/investigation (reading bibliographical sources; use of corpus linguistics); and questionnaire responses (surveys). Peer interaction and student leadership (part of the TLS approach) were promoted in the form of interaction strategies and collaborative learning (concept mediation strategies) and learner-centered, autonomous learning, and reflection through the questionnaire.

It should be noted that the aim of the study and the task it reviews is not to create perfect definitions but rather to create the best possible definitions for FD terms dealt with in the study in accordance with the student’s language proficiency level and prior knowledge of the field (SEN). It is also the objective of this study to show how the proposed task is useful to improve students’ knowledge and understanding of FD terms and this is exemplified in the evolution observed in the different tasks and in their final project. A personal vision of the usefulness of the task is also given by students at the end of the semester in the final questionnaire.

2 Materials, methods, and participants

The present study is based on the implementation of a task-based lexicographical practice and the analysis of student’s progress throughout the activities performed in class.3 One of the classroom instructors compiled and anonymized student forum data, answers to assignments, and dictionary projects. An anonymous questionnaire was also used at the end of the semester. These anonymized data were then analyzed by the second instructor. Nunan’s definition of the task as: “a piece of classroom work which involves learners in comprehending, manipulating, producing or interacting in the target language while their attention is principally focused on meaning rather than on form” (Nunan, 1989, p. 10), different classroom activities were designed around functional diversity terms which main goal was to work on word meaning and use.

In order to implement this curriculum idea, 20 students who were enrolled in the Lexicology and Lexicography subject in the fourth year of their English Studies degree participated in this study. The study aimed to enhance participants’ awareness of functional diversity both as a social construct and as a reality in their professional future. It is also intended to promote appropriate linguistic choice and to make participants aware of the importance of properly defining concepts and ideas. The tasks they performed were conducted in a language laboratory that facilitated computer use as well as the possibility of removing access to Internet browsers. While performing certain tasks, students were required to use their previous knowledge and skills rather than carry out internet searches. All tasks were completed in the Moodle4 system in their subject’s virtual classroom.

This lexicographical practice is twofold: on the one hand, it is rooted in students’ previous knowledge, further developed by peer discussion in forums; on the other hand, it is reinforced by study materials and corpus use training. The study is also supported by a qualitative analysis of a final questionnaire that is divided into two sections: questions posed from a lexicographic perspective and those related to critical reflection on FD concepts. The lexicographic perspective gives us data related to the development of lexicographic and mediation competence. The second part of the questionnaire sheds light on transformational language teaching and learning issues.

Students were provided with the following lexical items: “disability,” “Special Educational Needs,” “blind,” “deaf,” and “Asperger” and had to decide which lemma they would use in their dictionaries as an entry’s headword. Proficient students were expected to understand that “Special Educational Needs” is a concept and can be given entry status. They would also consider whether having this entry is a better choice than including this phrase under the entry for “needs.” In the same way, given the lemma “Asperger,” they had to observe its usage and this could lead them to understand that “Asperger’s” or “Asperger’s syndrome” were possible headwords. They should also consider the fact that dictionary users would be more interested in knowing about what the syndrome is about rather than knowing about the pediatrician who gave the name to the syndrome (which could be an entry in an encyclopedia). Another possible choice they could make was to use Asperger as headword and include “Asperger’s syndrome” and/or “Asperger’s” as in Manuel Seco’s Diccionario del español actual, where the meanings of the lexical unit studied are distributed within the article in primary groups according to the different syntactic categories in which this unit is inscribed according to its functioning.5 Students’ mother tongue, Spanish, could be a factor leading them to choose this last option.

It should be noted that the idea of the project was to work with particular conceptualizations of the words and, in this sense, they worked with the social and medical conceptualizations of the word “disability.” The following step should have been to introduce the biopsychological model of disability. In order to do this, more material would have been needed as well as more class time which was already too tight for the project. Moreover, students worked with corpus data and the idea was that they should work with the information they found in corpora. Finding information about and understanding the biopsychological model would be really challenging. The biopsychological model cannot be easily found as part of the collocational and example analysis in the corpora students used. This is a theoretical model and is not easy to find through text analysis alone. Thus, students were given material that they could relate to the corpus findings. Introducing the biopsychological definition of disability could be part of the classroom input but outside the task proposed here.

It is important to mention that (future) teachers are mediators of values and beliefs in their classroom and to this extent, the practice developed for this study enabled students to develop mediation skills that can be very helpful in their future careers. More specifically, mediating sensitive terms such as those related to FD is a relevant professional skill for secondary school teachers. CEFR-CV mediation strategies (Stathopoulou et al., 2023) that were used for mediating concepts in the development of the task were as follows: (1) linking to previous knowledge (use questions to encourage people to activate prior knowledge; make comparisons and/or links between new and prior knowledge; provide examples and definitions), (2) adapting language, and (3) amplifying a dense text (give examples and provide labels and usage notes).

Materials used during the task implementation were online dictionaries and activities designed by the instructor, including Moodle forums and assignments as well as thematic documents informing about the five terms studied that are used by students to inform their final dictionary project. In order to inform their dictionary project, students were also trained in the use of the corpus tool Sketch Engine6 (Kilgarriff et al., 2014) by performing a few classroom activities with the tool using several of the corpora contained made accessible through the Sketch Engine. Students were also guided into corpus use by using the embedded pedagogical videos contained in the Sketch Engine webpage.

The task devised for this study differs from traditional TLS because it is completely aimed at teaching sustainability (SDG10) both in language form and content. Most ESD materials in language teaching solely present topics related to sustainability but are seldom related to transformational teaching. Sustainability topics as part of ESD usually lack the transformative profile of TLS and do not include action competencies that are related to the professional profile of students (as is the case of the pedagogical proposal presented and discussed in this article). Participants in the study: (1) defined terms in FD, (2) discussed the group definitions in forums, (3) critically analyzed the content of the defined FD terms in several lexicographical resources, (4) read materials succinctly informing about these terms containing selected excerpts dealing with these FD terms and used corpus linguistics tools for lexicographic research, (5) elaborated a dictionary project with definitions for FD terms with the experience gained from the previous steps and created dictionary entries for those terms, and (6) answered a short questionnaire to reflect on and analyze what they learned in this task.

3 Results

This section will first illustrate the results obtained in the different parts of the task and then present the results of the final questionnaire.

3.1 Task results

Task results correspond to the six activities (Sections 3.1.1–3.1.6) that formed part of the task. These were sequenced from the easiest to the most complex and were intended to build students’ knowledge on the terms they worked with.

3.1.1 Defining functional diversity terms as a lexicographic practice

Students were asked to work with five terms related to functional diversity. Participants were simply asked to define each word using their own knowledge and without using any dictionary or information source; that is, students used only their previous knowledge and competencies to write their definitions. Student’s computers had access to browsers blocked during the task. The first two terms, “disability” and “Special Educational Needs,” were used to introduce the topic and foster discussions on what they mean as well as different ways to refer to the same reality (e.g., handicap/disability/functional diversity).

The activity development was carried out during 5 weeks in which one of the five terms was introduced per week. They were asked to define one of the terms and the definitions were individually submitted by each student using the Assignment option in Moodle. All students answered at the same time, not being able to see other students’ definitions until the task was over.

The concepts selected for the task were as follows: disability, Special Educational Needs, blind, deaf, and Asperger’s. The following definition examples illustrate how these terms were defined, and the definitions selected represent the different ways students decided to define these words. It should be noted that what the participants say in their definitions does not necessarily coincide completely with what they intended to say as they are all learners of the English language. They may even use words because they think it “sounds better” when they use difficult or uncommon words. Therefore, we need to remember that students are not only learning about the terms they are defining but also about the English language and how to express the meaning of concepts and ideas. The definitions presented below may also respond to different senses of the words instead of the sense that is related to functional diversity. Definitions are reproduced verbatim.

3.1.1.1 Definitions for disability

S3. It is a term that defines the lack of characteristics or capabilities of a person or an object.

S1. It is a physical or mental handicap that makes it difficult for someone living a full, normal life or from holding a gainful job; incapacity.

S12. It is the lack of capability of aptitudes regarding a certain physical or psychological aspect of the human body.

S14. It is a mental or physical condition that limits a person’s movement, capacity of thinking…

S5. Lack of (physical or mental) capacity to think or act as is required in any situation.

S2. The inability to do something. It may refer to either a physical or mental condition that characterizes a person and which may prevent him or her from developing a certain action.

3.1.1.2 Definitions for special educational needs

S15. Are the specific needs in the educational sector used to teach people with any disability Educational Needs.

S9. Special educational needs encompass different tools to carry out the learning in those students that under personal circumstances cannot follow the same educational system than the others.

S6. (n.) Special educational needs represent a set of necessities or supports which some learners, during the process of learning, must have at their disposal when difficulties arise along the process.

S8. (n. pl.) It refers to the set of cognitive individual characteristics or factors of learners that may affect pedagogical instruction in classroom settings.

S12. Special educational needs: it is the amount of specific means that are used to process the information given more appropriately to disable people.

S14. It may refer to those educational aspects students need to develop in order to deal with the learning process.

3.1.1.3 Definitions for blind

S16. Adjective. It refers to the incapacity to see or perceive things through sight. For example: He needs to walk with a stick because he is blind.

S12. It is the disability to not see totally or partially.

S11. It is a term that is used in order to describe a person or an animal who has a lack of vision. It can be total of partial.

S17. A person which is not able to see.

S13. A disability that characterises people that are not able to use the sense of sight.

S6. It is an adjective that makes reference to the inability to see or watch that anyone can suffer, either people nor animals.

3.1.1.4 Definitions for deaf

S14. It may refer to a person’s unwillingness to hear.

S2. Deaf is the person who suffers hearing problems total or partially.

S13. A disability that characterizes people that are not able to use the sense of hearing.

S5. Lack of the ability of audition which can be attributed to any living thing.

S7. It is the physical inability to hear.

S4. It is a disability related to the listening in which a person is not capable to listen.

3.1.1.5 Definitions for Asperger’s

S3. It is a personality disorder that some people have which makes a person to behave or react in a particular way. The name comes from a scientist who discovered this issue.

S16. Syndrome which is characterized by a disorder of the personality of a person with respect to socializing with other people and understanding daily things.

S8. It refers to the cognitive disability regarding individual lack or problems of expression, emotion, attention or affection.

S20. Mental condition included in the Autism Spectrum Disorder which affects communication skills and social relations. People with Asperger’s usually develop very restrictive interests on specific subjects.

S15. Neurobiological disability compared to autism. People who suffer this disorder have an alteration of the behaviour and they tend to be clever in a specific sector.

S5. Mental disorder of a human being which leads to the incapacity to socialize and think or act as required in any kind of situation. This disorder is also characterized by over developed brain which results in high academic achievement.

As can be seen from the above examples, there are different degrees of understanding of the five terms. Participants also differ in their skill to define with more or less accuracy (for instance, being able to understand that SEN refers to the needs and not to the people with those needs). The level of understanding also differs from one term to the other, and it seems the group understands the concept “Asperger’s” more clearly than the other terms. This may be related to the fact that in their university there is a high number of students with Asperger’s (31.8%) as compared to other SEN students (visual difficulties 22.7% and hearing difficulties 40.9%, where only a few students are totally blind and no student with severe or profound hearing loss, and those with hearing difficulties enrolled in language programs are not students with an important hearing loss).7 Being able to relate with students with Asperger’s may have made them understand this condition more fully than others, particularly when other types of diversity do not interfere with communication among students and affect students with SEN more deeply than it may affect their relationship with their partners.

3.1.2 Forum discussions

Asking students to discuss in forums which of the (anonymized) definitions they had previously submitted were best for each defined term. The forum discussions activated for this task provided a space of debate where different participants contributed to what the others knew about functional diversity.

Once all definitions were submitted, the teacher would choose eight anonymous student definitions different in form, content, and information types and created a forum in Moodle for each term. Students were then asked to say which was, in their opinion, the best definition in the list and why. After students submitted their own definitions, forum discussions were used to compare possible term comprehension and ways to express what they wanted to define. The terms were dealt with one by one, each term had a dedicated forum. It should be noted that as the participants go on with the tasks along the course, they become more and more aware of the susceptibility of the terms being used and this creates a visible difference between the first terms defined and the last terms they worked with.

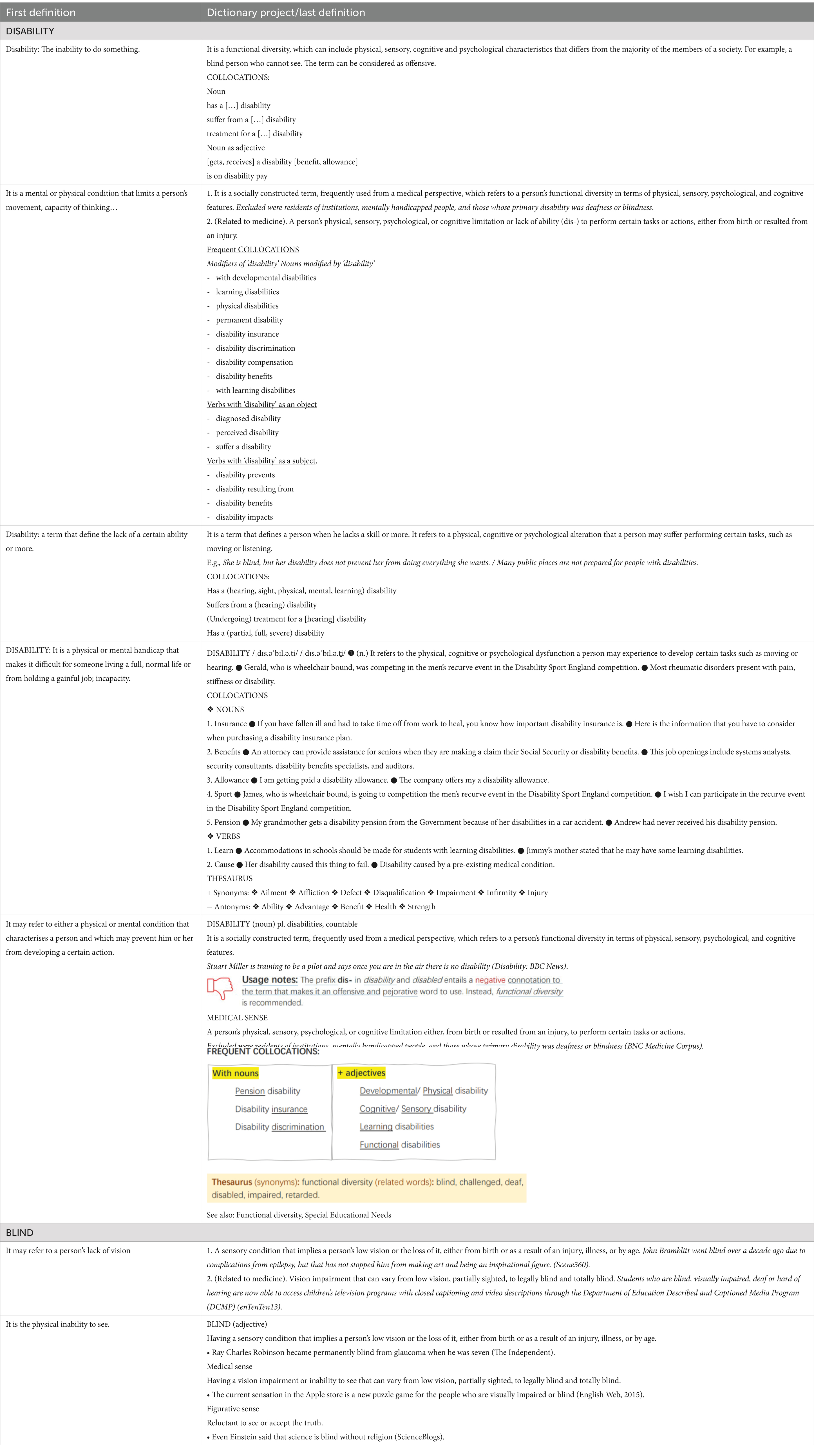

Table 1 shows part of the discussions for all terms.

The selected forum answers show how students focused on a number of interesting questions. First and most important, they paid attention to the extent to which the group’s definitions clearly explained the text. Second, they paid attention to the accuracy of the definitions (whether the information was correct) and to the fullness of the definitions (whether they lacked information). Third, they suggested improvements to the definitions and started thinking about how much more information they would include in their dictionary projects. Hence, they paid attention to grammar and grammatical categories and language choice and also suggested the inclusion of usage notes.

3.1.3 Analysis of terms in online lexicographical resources

Students examined and analyzed the content of the defined FD terms in a number of lexicographical resources, namely, three online dictionaries that provided different definitions and treatment of the terms. Differences in format and how to present information as well as amount and quality of the information presented in dictionary entries were important to further enhance students’ comprehension of FD terms and the ways information about concepts can be presented. The selected works to contrast FD term definitions were as follows:

• Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English.8

• Merriam Webster Dictionary.9

• Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary.10

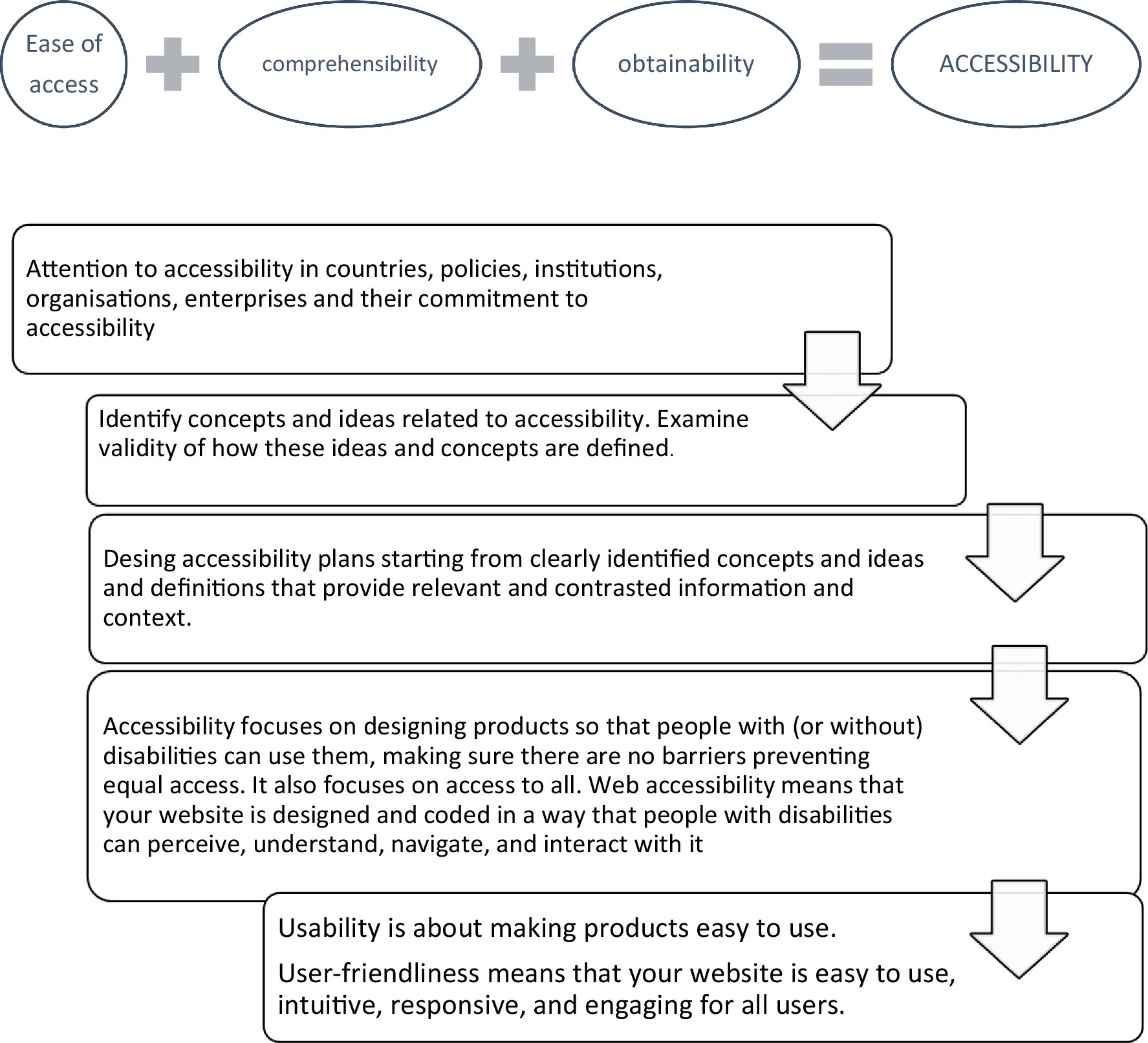

The different entries for disability, Special Educational Needs, blind, deaf, and Asperger’s were simply contrasted in the three dictionaries, and students closely examined how information was presented and the amount and type of information presented. Figure 2 exemplifies how one of these terms, disability, is presented in the dictionary entries:

Figure 2. Dictionary sample content used to work on FD terms. (A) Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary. (B) Merriam Webster Dictionary. (C) Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English.

Not all information contained in these dictionaries is included in this figure, but the figure shows dictionary features that may be compared. For example, the definition in the Oxford dictionary talks about “a physical or mental condition” and includes “learning disability” as a separate phrase and entry. The Longman dictionary defines disability as “a physical or mental condition” and suggests as possible frequent phrases “learning/physical/mental etc. disability.” The Merriam-Webster definition talks about “a physical, mental, cognitive, or developmental condition” and includes “intellectual disability” and “learning disability” as separate phrases and entries. Additionally, the Oxford dictionary includes a usage note (Which word?) with extensive information on the differences of the terms disabled/handicapped and provides further information on the uses of learning disability vs. learning difficulty in American and British English. Finally, Oxford and Longman dictionaries differ in the way they present the topics that are linked with the entry for disability. While Oxford addresses the entry reader to Disability as a topic and presents a list of searchable words in the dictionary including terms such as blind, blindness, sign language, and learning disability, the Longman Dictionary links the disability entry with Disability and Illness as a topic. This takes the dictionary user to a very varied list of searchable entries including for instance: specimen, hard of hearing, self-examination, coma, bellyache, dialysis, bruise, blood transfusion, sexually transmitted disease, disorder, or palsy. These terms are visualized in a cloud of words where letter size indicates term frequency.

The word disability in two of the dictionaries is related to the topic of illness, thus giving a medical view of the term. The Oxford Dictionary, however, provides more useful related terms by relating it to disability terms only, taking a social approach to the term.

3.1.4 Reading excerpts on FD terms

Reading materials prepared by the instructor were selected excerpts from different sources used as samples to know more about those terms. These materials were intended to represent specialized source materials used for lexicographic consultation but are by no means exhaustive. They were created for the students to understand that for specialized terms they need to look up specialized sources of information. These materials were intended to be comprehensible input in the sense that the selection of excerpts was made to provide additional information on the terms but at the same time students read excerpts instead of the full text to reduce their learning load. The aim of these documents was thus to be informative, but the length of the texts was reduced to meaningful excerpts with the aim that students would not lose their motivation to read the texts, which could in all instances be accessed in full in case they wanted to read the whole text for each excerpt. A sample of this material for the term “disability” is shown in Appendix 1.

3.1.5 Corpus analysis

The final activity was programmed to train students on how to find information using corpora in the Sketch Engine tool to design their dictionary entries. A linguistic corpus may be defined as a collection of digitalized texts that users of that corpus may interrogate through the use of corpus tools in order to gain knowledge about words and their linguistic patterns. One of the uses of corpora, particularly with philology or translation students, is its pedagogical use (Lőrincz, 2024; O’keeffe et al., 2007; McEnery and Xiao, 2011) where learners explore digital texts and learn about word and pattern usage, while gaining in-depth knowledge on word meaning due to the analysis of corpus concordances in the form of key word in context (KWIC or strings of text where a key word appears) and by accessing to the paragraph or text the concordance comes from. Collocational pattern information (recurrent use of word combinations) also aids comprehension of a word or phrase, as typical collocations expose the co-text and ideas related to a specific term.

Within pedagogical corpus linguistics, this study aligns with what Ma et al. (2022, p. 7) suggest as ways forward in corpus-based language pedagogy (CBLP) when they talk about “integrating corpus technology with their pedagogical reasoning into their teaching.” In this sense, the study combines CBLP with concept understanding to raise awareness of what is functional diversity and how people talk about and understand it.

Corpus use with the help of the Sketch Engine tool provided students with an ample repertoire of real examples that could be used to understand term usage and exemplify terms in their dictionary projects. The concordance tool yielded typical word combinations with the selected terms, such as “learning disability,” “partially deaf,” or “Asperger’s spectrum.” These combinations show different realities and situations students had to consider for their final dictionary projects. It also allowed for the comparison of the use of terms like “disorder” and “disability” where they could see how the typical attributes for “disorder” were diagnosis, syndrome, and illness, while the attributes related to “disability” were burden, impairment, inability, barrier, or limitation. As part of corpus analysis students used both General and Specialized corpora, showing a preference for the enTenTen corpus (English web corpus) as representative of speech used by the majority of speakers. Participants had to take into consideration statistical data in corpus investigation results (word combination significance and frequency).

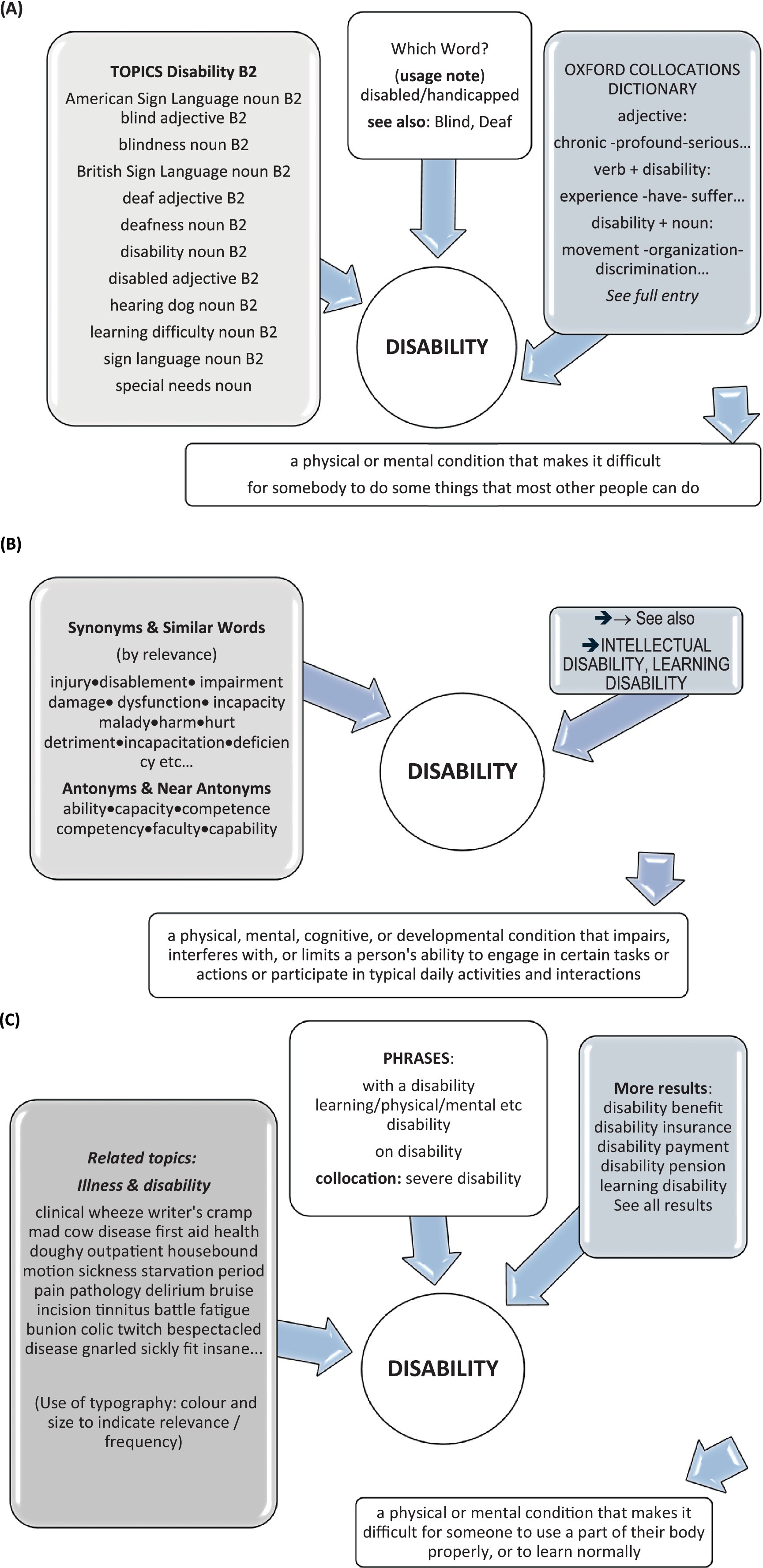

3.1.6 Dictionary project

Students had to compile a small dictionary (containing 45 entries) with the help of corpora, using the Sketch Engine tool. For the five chosen terms, apart from corpora use they had all the material developed and discussed in the previous activities. In this project, they elaborated definitions for FD terms and created dictionary entries for those terms. This section compares the final entry in the dictionary project (Section 3.1.5.) with the first definition they created in the first activity (Section 3.1.1) which was writing their own definition using their previous knowledge without using any source. In the case of the project they had a lot of information they could rely on, and this logically yields more complete definitions. However, the interesting part of the comparison is their choice of information for the dictionary entries and how much they changed their initial definition of the terms. To this end, Table 2 provides a comparison11 of the first and last definitions of the task. This table shows how students implemented what they learnt throughout the task with different degrees of success. This means that the change of words in their dictionary project may not be the best one but still show some awareness that the previous wording was not adequate. It may also be the case that the change of word implies no improvement. As an example, one student changed word choice from “handicap,” “normal life,” “incapacity” to “dysfunction,” “develop certain tasks.” Another example presents a change from “physical inability” to “sensory condition that implies physical inability.” They may also provide more informed definitions, for example, from “a person’s lack of vision” to “person’s low vision or the loss of it, either from birth or as a result of an injury, illness, or by age” also specifying that blindness “can vary from low vision, partially sighted, to legally blind and totally blind.” Generally speaking, students also became aware of the different contexts where the terms were used, such as medical contexts or educational contexts, as well as idiomatic or figurative use of the terms.

3.2 Questionnaire results

Appendix 2 shows the questionnaire that was used at the end of the semester after students had gone through all the activities proposed in the task. This section comments on and exemplifies different aspects of this classroom experience representing the answers of the whole group. The questionnaire has two parts: the first part contains questions from a lexicographic perspective, interrogating participants on their task completion and practice in designing entries for special educational needs terms; the second part deals with a reflection on FD concepts and how this may relate to their professional future. The coding of responses means student (S) and the number they were given in the anonymization process. Responses from all students are chosen for one answer to a question or another and are representative in content (i.e., one answer has been chosen and there were five answers providing the same information)

Q1. You have been working with special needs vocabulary. What have you learnt about this topic that you didn't know before?

S6. Regarding special needs vocabulary, I have learnt how to express myself correctly when dealing with specific terms regarding this type of vocabulary, which may require, in some way, consideration and acceptance. Since terms within this topic need to be defined in the most accurate and proper way, how to choose proper words for doing so without sounding neither disrespectful nor rude, has to be considered and developed in the most conscious manner.

Thus, leading with this kind of vocabulary in our final projects (dictionaries) may have influenced us to be more considered and conscious when writing or expressing ourselves and knowing how to do it in its most precise and polite way.

S11. I learnt how to explain myself in a neutral way, because everything that I supposed it was “normal” it can offensive for another one maybe. Neutral definitions.

S14. While working with the topic of special needs I have discovered a huge amount of terms related to the field that I have never considered before. In fact, I realized that some of them have negative connotations and for that reason, people with that particular disabilities tend to create new ones that involve more positive connotations. Moreover, I found out that there are many related terms for just one single concept, that made me understand the lexical complexity of the topic.

S20. It became interesting to me how vocabulary related to this does yet have negative connotations at many of its instances. I find the main issue to be the misinformation people have on many of these terms. It is easier to address, for instance, Asperger syndrome as a disability or an illness rather than speaking of diversity. We do have as well terms such as “disorder” which, despite seeming more formal, are still perceived to contain a negative connotation and, as such, influence on the perception of special needs or “neurodiversity.” Should we at some point assimilate that “disorder” does not necessarily mean “disadvantage,” the integration of people with special needs will be easier. It is not only about the conditions of certain people themselves, but it is as well about what connotation do we provide to the language used, for what promoting contexts in which these words’ usage is further positive will result in a great help. Nevertheless (and adding my two cents as a diagnosed “aspie”), trying to simply positivize certain meanings will have a surrealistic impact on the collectives these address as well as for the words connotations themselves.

Q2. Separate forums were designed to work with the terms: Asperger’s, blind, deaf, disability, and special needs. How does lexicography help you understand these concepts better?

S4. They have helped me as I could see the other companions’ responses to the forum, so I could learn directly from them as well as from the definitions firstly provided in the forum.

S6. Lexicography helps us to understand these concepts better by word choice, although how the sentence and these words are introduced in the sentence structure play a big role here. Choosing the best word option to express ourselves would not be useful as long as we do not fit it correctly into the sentence. By participating in these forums and discussing with other classmates which was the best option for a word’s definition, made us notice different mistakes that maybe by our own could not, or maybe, by considering different aspects of each definition, a new one made by the combination of others could be made up, or a new definition by taking ideas of what had been read in other definitions.

S8. The participation in the forums has allowed us to share different opinions and points of view and question the word choices and etymology of each word, providing opportunities to improve this definition using inclusive language. I think that these forums have been an excellent activity to activate our critical thinking, encouraging to question the different words used in society.

S12. Lexicography helped to understand those concepts better as we had to elaborate our own definitions for each of them, by selecting the most appropriate aspects to include. Moreover, we needed to provide examples, collocations, a thesaurus, related terms, usage notes, and phraseology, among others. Therefore, we have acquired lot of knowledge of each word and also of the use of particular online resources in order to find the information.

S18. I was familiar with the terms blind and deaf, as mostly everybody I guess, but I did not exactly know what was Asperger or how exactly can disability be defined. I think that learning their meaning has made me develop a more inclusive mentality, especially in the classroom area, where we will be dealing with young people.

Q3. Which part of your entry for each of these terms helped you the most to add sociocultural information?

S2. The part where I gave some examples. Examples from the real world form part of the contextualizing process that makes us aware of the real world. The notes in which we have to add extra information to clarify or avoid misunderstandings. And then the definition, as we tried to be accurate and faithful to what these terms actually mean.

S5. The parts of examples, usage and phraseology are the ones which are more socioculturally related, since they include different usages of the same word in context. For example, informal usage, or idioms.

S8. I think usage note in an entry, which can be in a different section or included in the definition, may serve to add information regarding subtle differences concerning sociocultural information.

S9. In my case, the section of creating the definition was the most enriching for me because I had a limited knowing about these words, so thanks to this project I learnt much more information.

S10. Disability for sure. As the time goes by, the definition of disability and the word itself has been changing. Hence, the language is necessary that it gets adapted to the society.

S11. Probably the socio-cultural information is added to the senses and collocations. Collocations are very important since they add connotations to the meaning of the word.

Q4. Which part of your entry do you think will help the users of your dictionary to employ the term correctly in any (sociocultural) situation?

S2. In my view, the part of my entry that will help the users of my dictionary to employ the term correctly is the definition part. Moreover, the example part is also relevant in order to contextualize the term, complement and clarify the definition.

S3. The notes which provides relevant information and also proper examples of each definitions.

S4. The collocations part, I think it is the most complete, as it helps to understand the many ways in which a word can be combined.

S10. I think the section of the examples is very helpful because the term is already included in different contexts to show people how to use it.

Q5. Explain which information types you designed to complement the information given in the definition for one of these entries and try to explain what you used each of these information types for.

S9. All the dictionary entries contain the definition, thesaurus, useful collocations and usage in order to provide more information regarding their usage. Additionally, some entries such as in the word “blind” or “deaf” I included the section “Phraseology” which provides information regarding metaphors or idioms frequently used with this term. Thus, this section gives extra information about their usage.

S15. I designed some usage notes since they give the reader lots of advice helping them to avoid making some of the most common mistakes of usage. For example, in the entry for the term ‘deaf,’ I added a usage note to make the distinction between ‘deaf and ‘Deaf’. Deaf people (with capitalized D) refers to dead persons belonging to this community.

Q6. Consider your practice in designing entries for special needs terms. In which ways is lexicography useful for a philologist? How does it make you more professional? Does it give you a new perspective to understand the world?

S4. As human beings, we use language in our community in order to communicate and satisfy so our needs. The language that we employ should be inclusive, that makes us to take into consideration everything which is the reason why we have to treat the language carefully. By not adding a term, we are in a way excluding some minor groups in the society that have the right to be visible. For this, I consider that philologists have to know lexicography not only to be more professional in order to be more accurate or formal but also more human in reflecting the society in his totality and taking into account the diversity there exists.

S9. Lexicography has allowed me to delve into the words, their usage, construction, connotations and the effects words have in the society, competencies needed for a philologist. Thus, this course has helped me to understand how powerful words are and to question every word I see. Thus, I am more conscious regarding the importance of the word choices made, the negative connotations a word may have and the effects of words when interacting in society.

S13. My practice with special needs vocabulary was necessary for my upbringing as philologist since I took conscious of the serious and important task of defining tricky words that seem not to be ordinary. I also appreciate the professional look of lexicography. Being familiarized more often with dictionaries makes the student more aware of the dangers of using vocabulary. In fact, the usage of dictionaries is positive for the development of a student who will need skills related to the words. For this reason, it gives a new perspective to understand the world as examples like special needs vocabulary help to understand the current situation of different groups of people who may suffer discrimination or unfair episodes due to misunderstandings.”

S14. Lexicography is very useful for a philologist as it just not only provides us with information about definitions, but it also helps us to translate, understand different topics in detail, acquire knowledge of how to use a particular term, find very specific types of information, work with professional online programs and understand that words and meanings are very important in our lives. Therefore, lexicography has made us more professional philologists. In fact, it has given me a new perspective to understand the world as now I am more conscious about the real use of language, the different meanings that we can create when communicating and the importance of words in society and life.

S18. In my opinion, this subject has made me understand that lexicography is a key aspect for a philologist, something I wasn’t aware of before. I think so because learning exactly how to use a certain word, in which contexts to use a word or another, or how to define it if we are teaching and a student has a doubt, is very important for us. Besides, getting to know different words, especially those related with special needs, has made me have a broader perspective of the world, and understand different situations I wasn’t aware of.

Question 7 to 11 relate to the transformative language for sustainability (TLS) part of the project, the reflection on what was learnt regarding FD concepts and how we use them to communicate.

Q7. Were you acquainted with the term “functional diversity” prior to this course? Will you be incorporating it in your vocabulary from now on as an alternative to disability?

S7. I did not know so many things I have learnt this course, which are highly important, that at least if I cannot remember that term when talking about it, I for sure, will be more conscious and careful with my words and the message I want to transmit. But it has been a pleasure being able to improve my speech by knowing more and new words.

S9. Although I had heard before the term “functional diversity” in educational contexts, I have not been aware of the importance of word choices and the different connotations a word or expression can have.

S14. I have discovered the term functional diversity during the sociolinguistics subject as we had to find information about the language used in society and we found a very useful example in a poster regarding people with functional diversity. However, in lexicography I have developed my knowledge on the term and of course, I am going to incorporate it as an alternative to disability because I consider that, as it is a concept created by people who suffer that problem, they would prefer the rest of the society to employ it rather than the previous one (disability) as it can involve some negative connotations.

S15. No, I was not acquainted enough with the term functional diversity prior to this course. From now on I will make use of this word as an alternative to disability since the term functional diversity, which is a social term that embraces each individual’s complex and diverse way of being, behaving, and functioning from a physical, psychological and cognitive perspective promotes respect and social acceptance of those who are seen as ‘disabled’ people.

Q8. Knowing that the term disability is a socially constructed concept, do you think your perception towards it has changed?

S1. Yes, I do. As I said before, I was aware of some of these terms but in my language. These concepts are socially constructed concepts that we accept as correct. After this course, my perception has changed, I have introduced new concepts and added new vocabulary, which is very useful today.

S15. The term disability seems to be not rationally defined but socially construed since ‘disability’ is determined by the social meanings people attach to a particular physical or mental impairment. My perception of the term ‘disability’ has changed since working with the topic of special needs made me evaluate, criticize and reflect upon the term ‘disability’. Nowadays, the term ‘disability’ is seen as something ‘abnormal’, ‘bad’, ‘problematic’, as a ‘tragedy’, in few words, using the term ‘disability’ discriminates this community. Therefore, people should stop treating people with special needs as less than human, and stop seeing them as ‘abnormal’ or ‘problematic’ people.

S16. No, I still think the same. By having a disability, you are no less than someone who does not.

S18. Yes, my perspective has totally changed since I believed that the term disability was not a socially constructed concept and therefore was the appropriate one to refer to functionally diverse people. Now, I am mindful of this fact Therefore, now I am more interested in looking for words which could be the same and that increases my motivation for learning more vocabulary.

Q9. Language matters. How we refer to people affects the way they are seen by others and the way in which they feel about themselves. Do you think that being mindful of this fact will prevail in choosing how to address people with functional diversity? What can you say about this as a philologist?

S1. Definitely. Language does not only define words but also people. In other words, language tells what we really are. We could state that being mindful of this fact we have the chance to address functionally diverse people in a way they could feel respected and comfortable. As a philologist, we must support that people feel respected and give people the opportunity to find theses term to make humans beings proud of themselves.

S3. We have to be careful of how we use language since many times we qualify and that makes us highlight the positive and negative aspects of things or people. It may be done unconsciously for something cultural, but it would be good if we could realize what we say and what we do not say as well, if we make it with objects it is not a big deal but with people is a different story because its emotional stability is at stake and his integrity as a person as well.

S16. Yes, I think this will affect for the best how we refer to people with functional diversity, since we will be able to put ourselves in their place. As a future philologist I think that change is in us and not in the way we give a word a different meaning.

S17. Yes, I think this will affect for the best how we refer to people with functional diversity, since we will be able to put ourselves in their place. As a future philologist I think that change is in us and not in the way we give a word a different meaning.

Q10. Societal attitudes towards people with disability in history have been predominantly negative, conveyed by means of language that portrays them as negative, as a problem. Is it right to think that a disability is an attribute of an individual that refers to the “lack of (dis-)” something?

S12. No, it is not true that disability is part of him or her but it cannot be labeled as disabled only because “lacks of something,” people are more than a simple label. However, this label affected considerably people who suffer from functional diversity, and they are misjudged by the lack of something and they are isolated from the society.

S13. I think it is right since we cannot change the patterns of nature. Vocabulary is needed to describe this kind of processes within nature, therefore words like disability are correctly used to explain a feature (or lack of feature).

S18. It is important to think about what we are saying before we say it since it can heart someone [hurt]. Therefore, societal attitudes towards disabled people are negative and people should be aware of it. In many cases, a disability does not necessarily mean that a person lacks of something. Instead, it can mean that the person has not developed an ability to the extent of the rest. Therefore, it is not right to think that the word disability refers to the lack of an ability since the meaning is not that one.

S19. People with disabilities have always been treated differently from the rest, especially years ago. But nowadays in most countries a person with a disability is treated just like a person who is not.

Q11. Teaching diversity to students has hitherto included individual differences along the dimensions of race, ethnicity, and gender. Do you think it is important to incorporate teaching functional diversity in the school curriculum? Why?

S4. Yes, educational settings have to be accommodated and allow blind people have the same opportunities as the others. What might be an impairment at first sight for us, might not be an impairment for them as they have adjusted to their reality and we have to make the effort to adapt our system for them as well. Therefore, materials have to be accommodated, furniture, equipment, the mainstream classmates have to be aware, etc.

S8. Try to organize classes-physical classes that is—to be as comfortable as possible for that student, make sure the sound can be heard properly for the student to be able to follow the class. Organize the subjects so they all include a huge percentage of the skill the blind student will need the most to improve. Try to include practices more inclined to the need the student might have, more related to listening and speaking and, those related to reading and writing should allow the student to have more time taking into account the difficulties the student might find regarding time. Include the student into discussions. Find all the material a blind student might need and offer it to him.

S15. In general, the university, the department, teacher, classmates, staff and so on should accommodate this students’ environment in order to make he/she feel included in society and make he/she feel comfortable. In this sense, it is important to change the medium used, e.g., braille, large print, audiotape, electronic text and oral testing/scribing use are recommended. Moreover, verbal descriptions of visual aids, raised-line drawings and tactile models of graphic materials should be provided to this blind student.

S19. In my opinion, I think that a person with a disability has to be treated equally to other people. In this case, a blind person can perfectly follow a class since much can be learned with the ear. Where if you could have difficulties, and therefore have some help, it is when doing work, individually or in groups, or when doing exams.

4 Discussion and conclusion

This study has presented a way to introduce functional diversity terms in the classroom as part of transformative language teaching for sustainability. As expected in a TLS practice, students actively participated in the study and the fact that many of the activities were challenging led them to engage in discussions and be motivated to improve their knowledge and use of the English language as well as the knowledge of ideas around sustainability concepts (FD terms). The different activities contained in the task proved to have a useful sequence design as they involved students little by little, from the simplest task of defining with their own words and knowledge to the forum discussions and further elaboration of full dictionary entries. This also enabled them to mediate concepts with other members of the class and in their final project. The definition practice throughout the task and the consultation of specialized readings and linguistic database resources showed them ways to be informed about words, their meaning, and their use. They also allowed for consultation regarding the sources of examples taken from corpora (whether the source was a political or an educational text, for example). The fact that all activities were put in common created a collaborative atmosphere where students learned from each other and were all able to gain new conceptual and linguistic knowledge while developing their know-how skills. The forums were valuable to the extent that they made students become aware of how clear they are (or not) when they speak and write (in this case definitions), how much they know about specific terms and the ways in which information can be expanded in a definition. The role of usage notes and information on collocations was clearly perceived as very useful to increase their knowledge about terms and how to use them. This expansion would finally reach an optimum level in their final dictionary project with different degrees of efficiency. They were also able to contrast how the five analyzed terms were dealt with in the three online dictionaries they examined further developing their critical thinking skills. The specialized readings immersed the students in a deeper understanding of the terms while being informed of other social and cultural aspects they might be unaware of.

The results from the questionnaire also point in the direction that students felt they had become more proficient in understanding and explaining concepts (mediating concepts) as well as being able to manage definitions from a respectful perspective becoming conscious of the importance of properly defining sensitive terms. Participants increased their lexical range and depth as is shown in their task results and the answers to the questionnaire. The practice as a whole has also made them become aware of professional competencies developed in the subject of lexicography, as they felt they are now more accurate in the way they define and have also gained abilities in using corpus tools that will provide them the opportunity to keep investigating linguistic issues in their future as professionals. The answers to the second part of the questionnaire suggest that they have amplified their understanding of diversity and made them provide strong opinions on how educational institutions should deal with diverse students.

This is the sense that is given to the proposal of defining and developing a new SDG, SDG18, where language and communication for all is revealed as an urgent need to achieve a paradigm shift in the direction of language and communication oriented toward sustainable social change. This understanding of the use of language in general, and the use of the English language in particular has an important role in achieving the SDGs (United Nations, 2015). Recent research points in this direction in studies that reveal new ways to understand the world that are related to language use, interpretation, and communication (Burenhult, 2023; Buts et al., 2023; Nayak and Raval, 2024; Servaes and Yusha’u, 2023; Yusha’u and Servaes, 2023).

5 Limitations of the study

This study is a step toward finding ways to deal with functional diversity in the university classroom through TLS. It should be noted that only 20 students participated in the study and that the same experience with a different and/or larger group of students could have different results. Eagerness to participate in the experience is also not necessarily the same with different groups and not all students give full explanations and responses when confronted with questionnaires. In this sense, this particular group of students was exceptional and provided the researcher with valuable insights regarding the proposed task.

The aim of the study was not to reach perfect definitions, the tasks developed in class were intended to be a starting point for making students understand the complexity of terms while giving them tools to better understand them. This study has methodological limitations as it is a classroom qualitative experience and it is not based on experimental quantitative methodologies. In this sense, organizing similar classroom experiences using different educational theories and methods could provide more information on how to deal with diversity in educational settings. The study presented here is a qualitative analysis and as such is limited by the quantity and in this case the diversity of the data. The small number of participants limits the representativeness of the data collected in the study. Further research replicating similar classroom formulas and studies with a higher number of participants could lead to statistical analysis of results that could be relevant to build upon this proposal.

6 Further research

Further research can be implemented with other sustainability-related terms in relation to the SDGs and contemplating the SDG18 of communication as an interdisciplinary field needed to enact all other goals. The same task procedures may be followed with different SDG terms, different participants, and larger numbers of participants with different geographical provenance. Lexicographical approaches to FD terms from a theoretical perspective (Norri, 2018; Rice and Zorn, 2021; Nied Curcio, 2023) may also yield the foundation for classroom practices. The same happens with translation and with interpretation studies, such as Buts et al., 2023; Cooms, 2023; Lomas, 2016.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

MC-C: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This publication is part of the I+D+i Project PReLemma, PReLemma, Parameters for more accessible multilingual lexical resources funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation. «Proyectos de Generación de Conocimiento» (PID2022-137210OB-I00).

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Mª Teresa Fuentes Morán and Jesús Torres del Rey for funding acquisition of the financial support for the project leading to this publication. I would also like to thank my colleague Montserrat Esbrí-Blasco for clearing and annotating data to ensure anonymity and for her continuous, unfailing support.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1450096/full#supplementary-material

APPENDIX 1 | Text on disability (reading resource, part of the learning task).

APPENDIX 2 | Questionnaire on functional diversity tasks.

Footnotes

1. ^Functional diversity is defined by Palacios et al. (2012, p. 122) as: “Functional diversity implies different ways (neither better nor worse; neither more capacity, nor less) to live daily; it expresses the creativity of those who must do daily things in a different way of what is considered standard, because they require non-conventional tools (both human and technical). It expresses potential creativity of the group in a positive way; as long as all negative connotations, still associated to the conception of functional diversity as illness, are abandoned. In this case, the body is no longer a submission and control object, and becomes a potential innovation device, in a transformation, advance and improvement platform, that improves society.”

2. ^https://sites.utu.fi/ekko/

3. ^Students were informed that: The confidentiality of the information provided in this study is fully guaranteed. The results of the study will be stored and protected with the security measures required by current legislation (Ley Orgánica 3/2018, de 5 de diciembre, de Protección de Datos Personales y garantía de los derechos digitales; modificación BOE núm.110, del 9/5/2023). No personal data allowing your identification will be accessible to any person of the study or outside of it, nor may they be disclosed by any means, hence keeping at all times your confidentiality.

5. ^https://www.fbbva.es/diccionario/Asperger/

6. ^http://www.sketchengine.eu; https://data.europa.eu/en/publications/use-cases/sketch-engine

7. ^The nomenclature used in this paragraph is employed by the University Diversity and Disability Unit.

9. ^https://www.merriam-webster.com/

10. ^https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/

11. ^Participants were given a number in the anonymized documents that allowed for this comparison without revealing their identities.

References

Alduais, A., and Deng, M. (2022). Conceptualising, defining and providing special education in China: stakeholder perspectives. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs, 22, 352–367.

Andreou, G., and Galantomos, I. (2009). Conceptual competence as a component of second language fluency. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 38, 587–591. doi: 10.1007/s10936-009-9122-6

Burenhult, N. (2023). Sustainability and semantic diversity: a view from the Malayan rainforest. Top. Cogn. Sci. 15, 546–559. doi: 10.1111/tops.12654

Buts, J., Pięta, H., Ivaska, L., and Hadley, J. (2023). Indirect translation and sustainable development. Transl. Spaces 12, 167–176. doi: 10.1075/ts.00031.but

Caldwell, B., Cooper, M., Reid, L. G., Vanderheiden, G., Chisholm, W., Slatin, J., et al. (2008). Web content accessibility guidelines (WCAG) 2.0. WWW Consortium (W3C) 290, 5–12.

Campoy-Cubillo, M. C. (2019). “Multidimensional networks for functional diversity in higher education: the case of second language education” in Second language acquisition-pedagogies, practices and perspectives. ed. C. Savvidou (London: Intech Open).

Cooms, S. (2023). Decolonising disability: weaving a Quandamooka conceptualisation of disability and care. Disabil. Soc., 1–24. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2023.2287409

Council of Europe (CEFR) . (2018). Common European framework of reference for languages: learning, teaching, assessment. Companion volume with new descriptors. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe (Modern Languages Division).

Kilgarriff, A., Baisa, V., Bušta, J., Jakubíček, M., Kovář, V., Michelfeit, J., et al. (2014). The sketch engine: ten years on. Lexicography 1, 7–36. doi: 10.1007/s40607-014-0009-9

Lomas, T. (2016). Towards a positive cross-cultural lexicography: enriching our emotional landscape through 216 ‘untranslatable’ words pertaining to well-being. J. Posit. Psychol. 11, 546–558. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2015.1127993

Lőrincz, M. L. (2024). Language teaching challenges through the lens of corpus linguistics. TEFLIN J. 35, 40–65. doi: 10.15639/teflinjournal.v35i1/40-65

Ma, Q., Yuan, R. E., Cheung, L. M. E., and Yang, J. (2022). Teacher paths for developing corpus-based language pedagogy: a case study. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 37, 461–492. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2022.2040537

Maijala, M., Gericke, N., Kuusalu, S. R., Heikkola, L. M., Mutta, M., Mäntylä, K., et al. (2024). Conceptualising transformative language teaching for sustainability and why it is needed. Environ. Educ. Res. 30, 377–396. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2023.2167941

McEnery, T., and Xiao, R. (2011). “What corpora can offer in language teaching and learning” in Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (vol. 2). ed. E. Hinkel (London: Routledge), 364–380.

Nayak, P. S., and Raval, R. J. (2024). Fostering global sustainability: the role of English language in development. Educ. Admin. Theory Pract. 30, 1782–1785. doi: 10.53555/kuey.v30i1.6589

Nied Curcio, M. (2023). Lexicography, culture and mediation. Or why a good lexicographer must also be a good cultural mediator. Lexikos 33, 95–106.

Norri, J. (2018). Definitions of some sensitive medical words in dictionaries of English. Int. J. Lexicogr. 31, 253–273.

Nunan, D. (1989). Designing tasks for the communicative classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

O’keeffe, A., McCarthy, M., and Carter, R. (2007). From corpus to classroom: language use and language teaching. Cambridge University Press..

Palacios, A., Romañach, J., Vázquez Ferreira, M. A., and Ferrante, C. (2012). Functional diversity, bioethics and sociological theory: a new approach to disability. Intersticios Rev. Sociol. Pensamiento Crítico 6, 115–130.

Rabang, N. J., West, A. E., Kurtz, E., Warne, J., and Hiratsuka, V. Y. (2023). Disability decolonized: indigenous peoples enacting self-determination. Dev. Disabil. Network J. 3, 132–145. doi: 10.59620/2694-1104.1069

Rice, D. R., and Zorn, C. (2021). Corpus-based dictionaries for sentiment analysis of specialized vocabularies. Political Sci. Res. Methods 9, 20–35. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2019.10

Romañach, J., and Lobato, M. (2005). “Functional diversity, a new term in the struggle for dignity in the diversity of the human being” in Independent Living Forum (vol. 10) (Valencia, Spain: European Network on Independent Living).

Sass, W., Boeve-de Pauw, J., Olsson, D., Gericke, N., De Maeyer, S., and Van Petegem, P. (2020). Redefining action competence: the case of sustainable development. J. Environ. Educ. 51, 292–305. doi: 10.1080/00958964.2020.1765132

Servaes, J., and Yusha'u, M. J. (Eds.) (2023). SDG18 communication for all: The missing link between SDGs and global agendas. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Shume, T. J. (2023). Conceptualising disability: a critical discourse analysis of a teacher education textbook. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 27, 257–272. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2020.1839796

Sinakou, E., Donche, V., Boeve-de Pauw, J., and Van Petegem, P. (2019). Designing powerful learning environments in education for sustainable development: a conceptual framework. Sustain. For. 11:5994. doi: 10.3390/su11215994

Stathopoulou, M., Gauci, P., Liontou, M., and Melo-Pfeifer, S. (2023). Mediation in teaching, Learning and Assessment (METLA): A teaching guide for language educators. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe.

United Nations . (2015). Sustainable development goals (SDGs) and disability. Available at: https://social.desa.un.org/issues/disability/sustainable-development-goals-sdgs-and-disability (Accessed June 28, 2024).

United Nations . (2016). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. ADOPTED12 December 2006 by sixty-first session of the general assembly by resolution a/RES/61/106. Office of the High Commissioner for human rights (OHCHR) 1996–2024. Accessed at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-persons-disabilities (Accessed June 16, 2024).

Weder, F. (2023). Cultivation of sustainability in a discourse of change: perspectives on communication for sustainability as new “norm” and principle of action in socio-ecological transformation processes. J. Lang. Politics 22, 577–600. doi: 10.1075/jlp.22122.wed

Keywords: functional diversity (FD), accessibility, education for sustainable development (ESD), transformative language teaching for sustainability (TLS), lexicography, language learning and teaching (LLT), action competence (AC), SDG10

Citation: Campoy-Cubillo MC (2025) Learning outcomes of project-based learning activities on access to functional diversity terms. Front. Educ. 9:1450096. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1450096

Edited by:

Ewa Domagala-Zysk, The John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin, PolandReviewed by:

Anna Zamkowska, Casimir Pulaski Radom University, PolandMagdalena Olempska-Wysocka, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poland

Copyright © 2025 Campoy-Cubillo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mari Carmen Campoy-Cubillo, Y2FtcG95QHVqaS5lcw==

Mari Carmen Campoy-Cubillo

Mari Carmen Campoy-Cubillo