- Department of Communication Sciences and Special Education, College of Education, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, United States

The foundation of effective management lies in the recognition and reinforcement of appropriate behaviors. Researchers have found that class-wide, group-contingency-based classroom management approaches can be an efficient and effective way to promote desired student behavior. For this study, we examined the effect of Tootling, a peer-mediated, group-contingency approach wherein students identify and report on their peers’ prosocial behaviors. We used an alternating treatment single-case research design to evaluate and compare the impact of student- and teacher-led Tootling on disruptive behavior and academic engagement for five elementary students. Student-led Tootling, teacher-led Tootling, and no-Tootling conditions were alternated daily following a systematically blocked, randomized schedule. After each series of the three conditions, a group-based concurrent chain preference assessment was conducted to determine students’ choice of condition. Disruptive behavior decreased for all five students during both student- and teacher-led conditions, and although data were variable, all five students increased academic engagement during student-led Tootling. Findings from the concurrent chain preference assessment revealed most students preferred the student-led Tootling condition. Social validity questionnaires indicated teachers preferred student-led Tootling and found it acceptable and feasible, and student questionnaires indicated they wanted to continue using Tootling in their classrooms. Maintenance data demonstrated all three teachers continued implementing student-led Tootling after the study’s completion. Delegating students to lead the intervention can support the integration and sustained use of Tootling in classrooms. One important next step is to evaluate the feasibility of student-led Tootling in early elementary classrooms. Replications are necessary to understand the effects of student-led Tootling in various settings and grade levels.

Introduction

Effective classroom management is essential for achieving successful student and teacher outcomes. When teachers effectively manage their classrooms, they foster high levels of engagement among students and cultivate a positive and conducive learning environment, resulting in many benefits for students and teachers (Owens et al., 2018). Students who experience well-managed classrooms exhibit improved social skills, higher rates of appropriate behavior, and enhanced academic performance (Ennis et al., 2017; McLeskey et al., 2017; Oliver et al., 2015). Teachers who use effective classroom management practices are more likely to report higher self-efficacy in regard to handling classroom challenges and facilitating learning (Bettini et al., 2016). Teachers with high self-efficacy also report lower levels of job-related stress and higher levels of job satisfaction (Caprara et al., 2003).

In the pursuit of enhancing academic engagement and mitigating disruptive behaviors, many school systems have embraced the positive behavioral interventions and supports (PBIS; Sugai and Horner, 2002) framework. The goal of PBIS is to replace or reduce the reliance on traditional punitive disciplinary measures (e.g., detentions, suspensions) with evidence-based behavioral practices focused on prevention to improve students’ social, behavioral, and academic outcomes (Sugai and Horner, 2009; Sugai et al., 2014). The PBIS framework organizes interventions into a multi-tiered continuum of supports that addresses school-wide, class-wide, and individual student behavior. The focus of Tier 1 is on the provision of universally applicable strategies, Tier 2 interventions provide additional support for some students, and Tier 3 involves the implementation of the most intensive support for a few students.

The foundation of effective classroom management at Tier 1 lies in the recognition and reinforcement of appropriate behaviors, both individual and group. Researchers have found that when teachers ignore minor behaviors and acknowledge students for appropriate behaviors, students are more likely to be academically engaged and less likely to be disruptive (Owens et al., 2018). Teachers can acknowledge students’ appropriate behaviors using various methods, spanning from less intensive (e.g., verbal praise, gestural acknowledgment) to more intensive (e.g., behavior contracts). One established and efficient approach for identifying and reinforcing appropriate behavior is through class-wide interventions. Class-wide interventions have been shown to be particularly effective in reducing low-level disruptions (Maggin et al., 2017) and are considered less intensive in terms of the time and resources required for implementation. Furthermore, class-wide reinforcement strategies align with schools’ PBIS framework, where group contingencies have emerged as a commonly used evidence-based, class-wide intervention for teachers to acknowledge and reinforce appropriate behaviors (Skinner et al., 2002).

Extensive research has demonstrated the effectiveness of group contingencies in reducing disruptive behavior and increasing on-task and academically engaged behaviors across various grade levels and educational settings (Chaffee et al., 2017; Maggin et al., 2017). One promising class-wide intervention with a group contingency is Tootling. “Tootling” is a combination of tooting your own horn and tattling (Skinner et al., 1998), but is procedurally the opposite of tattling—students write down the prosocial behaviors they saw peers engage in, turn them in to the teacher who later reads a few or all to the class, and calculates the total of appropriate tootles to see if the class met their class-wide Tootling target. Tootling creates an opportunity for peers to play a role in recognizing and supporting (i.e., reinforcing) the prosocial behaviors of their peers (Collins et al., 2018). Tootling can be an attractive option for teachers because it engages all students in the activity of performing and identifying desirable behaviors. Additionally, peers can function as a discriminative stimulus, prompting students to engage in appropriate behavior in the hope of being recognized with a Tootle.

Similar to the Good Behavior Game (GBG; Barrish et al., 1969) and Class-Wide Function-based Intervention Training (CW-FIT; Kamps et al., 2015; Wills et al., 2016), Tootling involves the delivery of several effective classroom management strategies (e.g., recognizing appropriate behavior, teaching classroom expectations, providing feedback, providing rewards as reinforcement). However, Tootling extends group contingency procedures by teaching students to be peer mediators of the behavioral intervention by identifying and recording their peers’ appropriate behaviors (Skinner et al., 2000; Cashwell et al., 2001). Although prior research has established the efficacy of Tootling, studies have not included social validity data regarding students’ perspectives and primarily analyzed the effects of Tootling procedures on the class level (i.e., Can Tootling reduce the number of disruptive behaviors occurring in a class?) rather than at the individual student level (i.e., For students who exhibit the most disruptive behaviors, can Tootling reduce the number of their disruptive behaviors?). Additionally, a logical extension of Tootling interventions yet unexplored in the literature is having peers implement the Tootling procedures and evaluate if student-led Tootling procedures can be as effective as teacher-led Tootling at reducing disruptive behaviors.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to extend the Tootling research by using Tootling as a class-wide intervention to reduce disruptive behaviors and increase the academic engagement of target students who engage in relatively high levels of disruptive behavior. Additionally, the study aimed to modify Tootling procedures and compare the effects of student-led and teacher-led Tootling procedures. We hypothesized there would be minimal differentiation between data paths, suggesting both conditions are equally effective but that student-led Tootling may be less teacher-intensive. Finally, although previous studies have assessed teachers’ acceptability of Tootling interventions (Lambert et al., 2015; Lum et al., 2017; McHugh Dillion et al., 2019), fewer studies examined the preferences of students receiving the intervention. Given these aims, our research questions were:

1. Does teacher-led, student-led, or a choice condition of Tootling implementation have an effect on elementary students’ academic engagement, disruptive behavior, and passive off-task behavior?

2. When provided the option of teacher-implemented versus student-implemented Tootling, do students and teachers prefer one method over the other?

3. To what extent do teachers and students find Tootling procedures acceptable and effective, as indicated by social validity surveys?

4. Following the withdrawal of researcher support, to what extent do teachers maintain implementation of Tootling?

Method

Participants and setting

The study took place in a rural public Title I elementary school located in the southeastern United States, with an enrollment of approximately 551 students in grades K-5. Students enrolled were 49.7% White, 22.5% Hispanic, 19.6% Black, 6.9% Multi-Racial, and 1.3% Asian/Pacific Islander. As part of the school’s PBIS system, teachers used ClassDojo (classdojo.com), where they rewarded students with points for appropriate behaviors and deducted points for inappropriate behaviors. Teachers designated specific days when students could spend points on reinforcers like pencils or lunch with a friend. Students who attained a certain number of Dojo points were eligible to participate in quarterly field trips.

The principal referred classrooms based on the number of students in the classrooms who were receiving behavioral support as part of their IEP or Tier 2 and Tier 3 behavioral interventions. Referred classroom teachers nominated students who (a) exhibited high levels of disruptive behaviors, (b) were identified as at risk for having disability as indicated by the school’s multi-tiered system of support team, or (c) were already receiving special education services and had behavior-related goals on their individualized education program (IEP). We screened nominated students. Students who engaged in disruptive behaviors for 30% or more of observed 20 s intervals during a 20 min observation were included in the study.

Classroom 1

Classroom 1, a fourth-grade general education classroom, included 8 White, 5 Black, 5 Latinx, and 4 multi-racial students. Ten students received special education services. Teacher A, a White female with a Master of Arts in Education, had 4 years of teaching experience. During Tootling, two paraprofessionals and one special education teacher were also present in the classroom providing collaborative support services to students receiving special education.

Elian, a 10-year-old multi-racial male in the fourth grade, had a diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder and received special education services under the eligibility category of Other Health Impairment. Elian had a behavior intervention plan and did not take any medication for his ADHD. According to Elian’s IEP, Elian often engaged in disruptive behaviors such as vocal outbursts and making noises with materials.

Asher, a 10-year-old Black male in the fourth grade, had a diagnosis of ADHD and a learning disability and received special education services under the category of Other Health Impairment. Asher struggled with reading and had a behavior intervention plan. Data from Asher’s IEP indicated Asher struggled to remain on task, required frequent reminders to stop playing with materials unrelated to the task, and frequently tried to sleep during instruction.

Classroom 2

Classroom 2, a fifth-grade general education classroom, included 11 White, 9 Black, and 4 Latinx students. Seven students received special education, and two were English language learners. Teacher B, a White female with a Master of Arts in Reading Education, had 19 years of teaching experience. During Tootling, a special education teacher was also present in the classroom to provide collaborative support services to students receiving special education.

Darnell, an 11-year-old Black male in the fifth grade, did not have any documented disabilities but received Tier 2 support, Check-In/Check-Out, from the teacher. Darnell engaged in disruptive behaviors, such as making noises during instruction.

Jonah, an 11-year-old White male in the fifth grade, had a diagnosis of a specific learning disability and received special education services. According to his behavior intervention plan, Jonah struggled to follow teacher directions and engaged in verbal outbursts during instruction.

Classroom 3

Classroom 3, a fifth-grade general education classroom, included 11 White, 8 Black, and 4 Latinx students. Four students received special education services, and three were English language learners. Teacher C, a White female with an Education Specialist in Teacher Leadership degree, had 14 years of teaching experience.

Xavier, a 10-year-old Black male, did not have any documented disabilities and did not receive special education services. At the time of the study, Xavier was referred for Tier 2 behavioral supports; however, no supports were put into place. According to his teacher, Xavier frequently engaged in off-task behavior by talking with his peers.

Materials

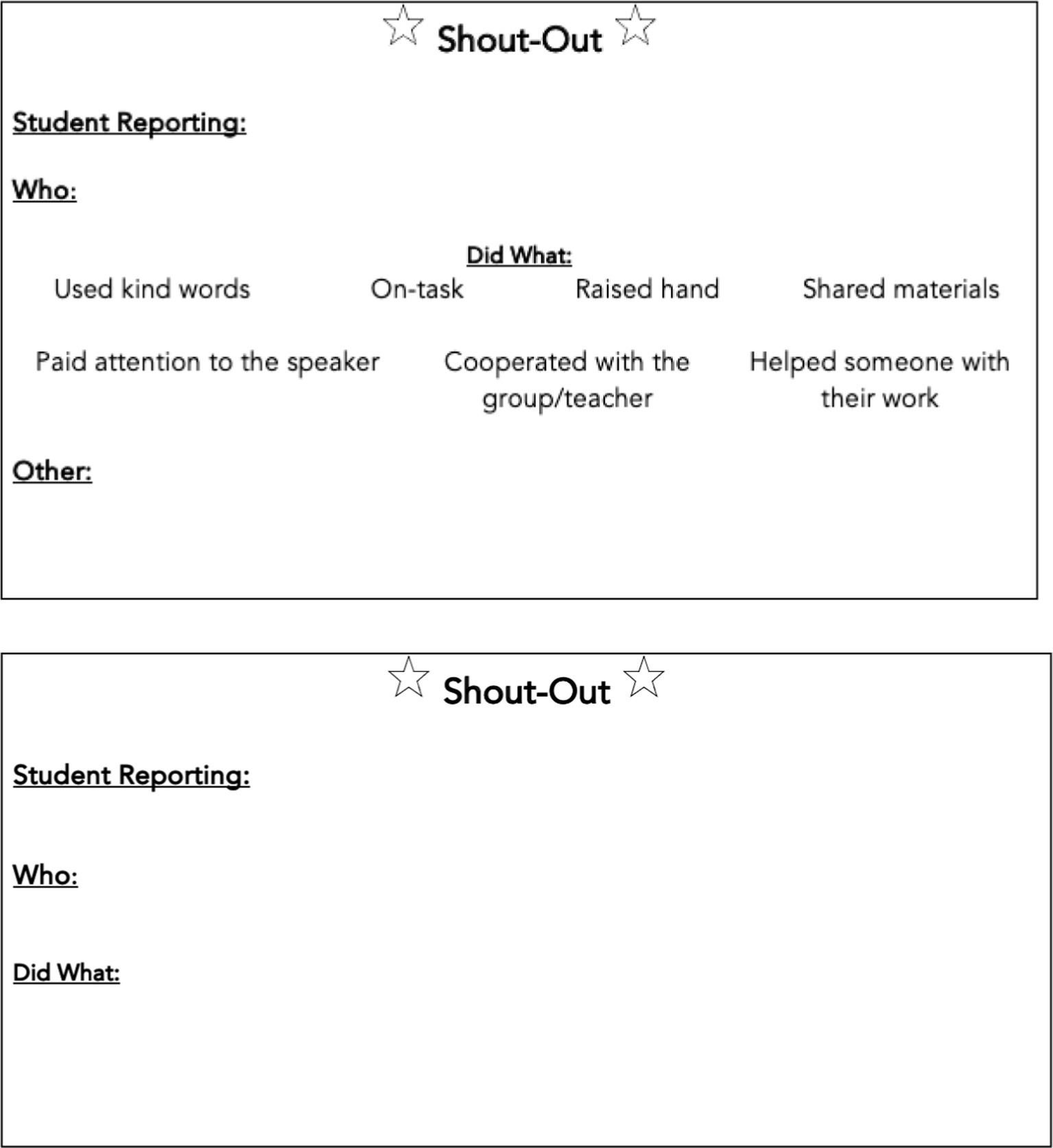

Tootling slips were printed on 4" × 6" paper (see Figure 1). Each slip included a space for students to write (a) their name, (b) the name of the student who did something Tootle-worthy, and (c) the specific positive behavior. Because many of the students in Classroom 1 had significant writing challenges, students received a modified slip with a selection of behaviors to circle (i.e., using kind words, being on-task, hand raising, sharing materials, paying attention to the speaker, cooperating with the group/teacher, and helping someone with their work). One 11 × 12 manilla envelope was used to hold completed Tootling slips, and another envelope stored blank Tootling slips.

A designated small whiteboard was used to keep track of the daily Tootles and progress toward the class goal. To indicate which days were student-led days, students’ names were printed on green paper paws for the teacher to draw from to identify which student was leading Tootling for the day. White paws with the teachers’ names were used to signify the teacher-led condition days. The paw colors indicated which condition the students were receiving.

The researcher provided classroom rewards as part of the interdependent group contingency included in the Tootling intervention. Prior to introducing the intervention to students, the researcher met with classroom teachers to identify allowable rewards, which included pencils, chips, extra recess, candy, and opportunity passes (e.g., extra computer time, wearing a hat to school).

Measures

Direct observation

The primary dependent variable was disruptive behavior. Disruptive behaviors were adapted from previous studies (Lambert et al., 2015; Lum et al., 2019) and included (a) out of seat, defined as standing or walking around without permission with no part of the students’ legs or buttocks in contact with the seat, (b) inappropriate vocalizations, defined as any vocal audible noise made unrelated to the task and included shouting out, talking off-topic, singing and humming, and (c) playing with materials, defined as making noises with materials unrelated to the task or manipulating objects or materials related to the task inappropriately (e.g., throw, flip, tap or touch a peer).

The secondary dependent variable was academic engagement. Academic engagement was defined as (a) attending to teacher instructions, defined as looking at the teacher or person speaking with body and face oriented toward the speaker; (b) participating in instruction, defined as using materials necessary to complete the task, oriented toward the task, and following the instructions given to complete the task (McHugh Dillion et al., 2019).

Passive off-task was recorded as an additional secondary variable and was defined as any passive or inattentive behavior of not attending to the task at hand but did not meet the definition of disruptive behavior. Passive off-task included placing head on the desk, looking in a different direction other than the task or the individual speaking (Harry et al., 2021). These three dependent variables were mutually exclusive and encompassed the range of behaviors exhibited in the classroom.

Observations occurred three to five times per week for 20 min using 20 s momentary time sampling. Observers used the Tempus Stopwatch application (fredrikblank.com/tempus) to record the first student’s behavior at the first 10 s interval and the second student’s behavior at the second 10 s interval, observing each target student’s behavior every other 10 s interval for a total of 60 intervals. The percentage of intervals each behavior occurred was calculated by dividing the number of intervals of occurrence by the total number of observed intervals and multiplying by 100.

The first author was the primary data collector, who trained secondary observers in a 20 min session on operational definitions of target behaviors and procedures for collecting data. Observers practiced data collection with the primary observer in each classroom, independently coding a 20 min observation, discussed differences, and established an average interobserver agreement (IOA) of 93.7% (range = 89.2–98.2%) for practice sessions across target behaviors and classrooms.

IOA was collected in Classroom 1 for 50.0% of sessions, 40.9% in Classroom 2, and 31.8% in Classroom 3 and collected evenly across treatment conditions. For each observation with a secondary data collector, point-by-point agreement was calculated by adding the number of agreements between observers 1 and 2 for each interval, divided by the total of agreements plus disagreements, and multiplied by 100 (Ledford and Gast, 2018). IOA was calculated for each dependent variable for each target student. Across all students and behaviors, IOA averaged 86.8% (range = 64.7–100%). The primary data collector retrained secondary collectors following Session 11 when IOA dropped to 64.7%. Following retraining, IOA remained above 80%.

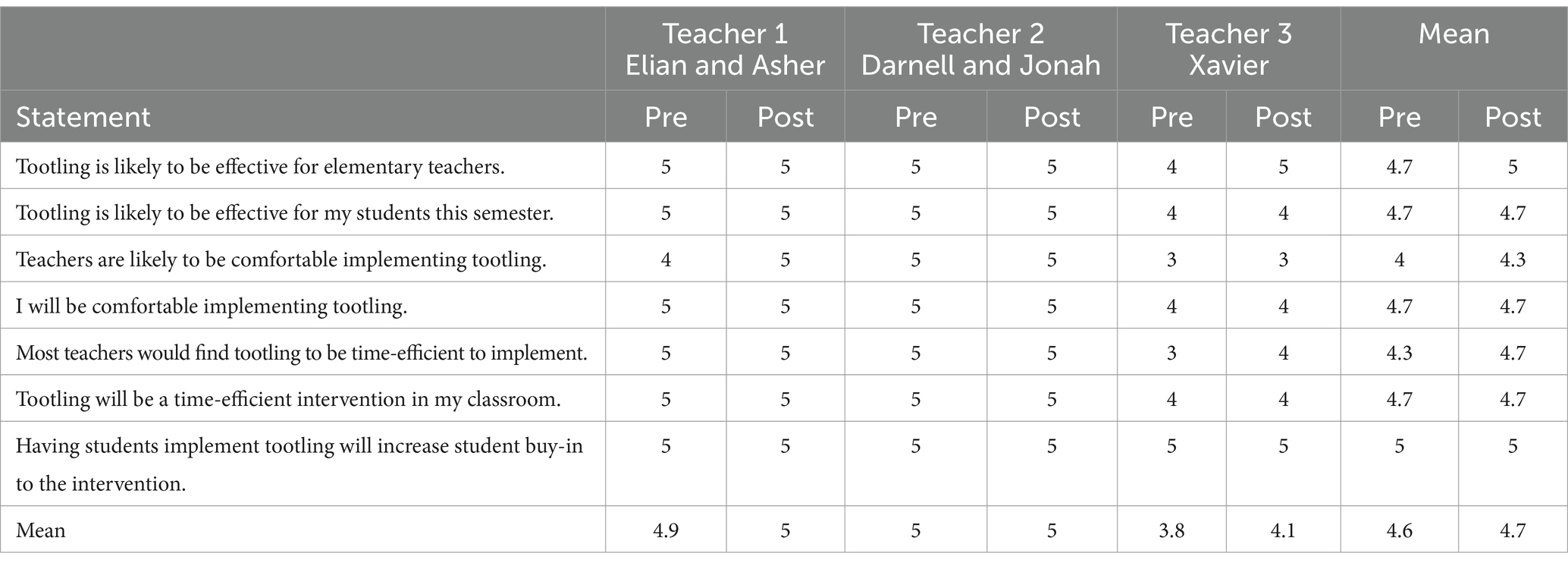

Social validity

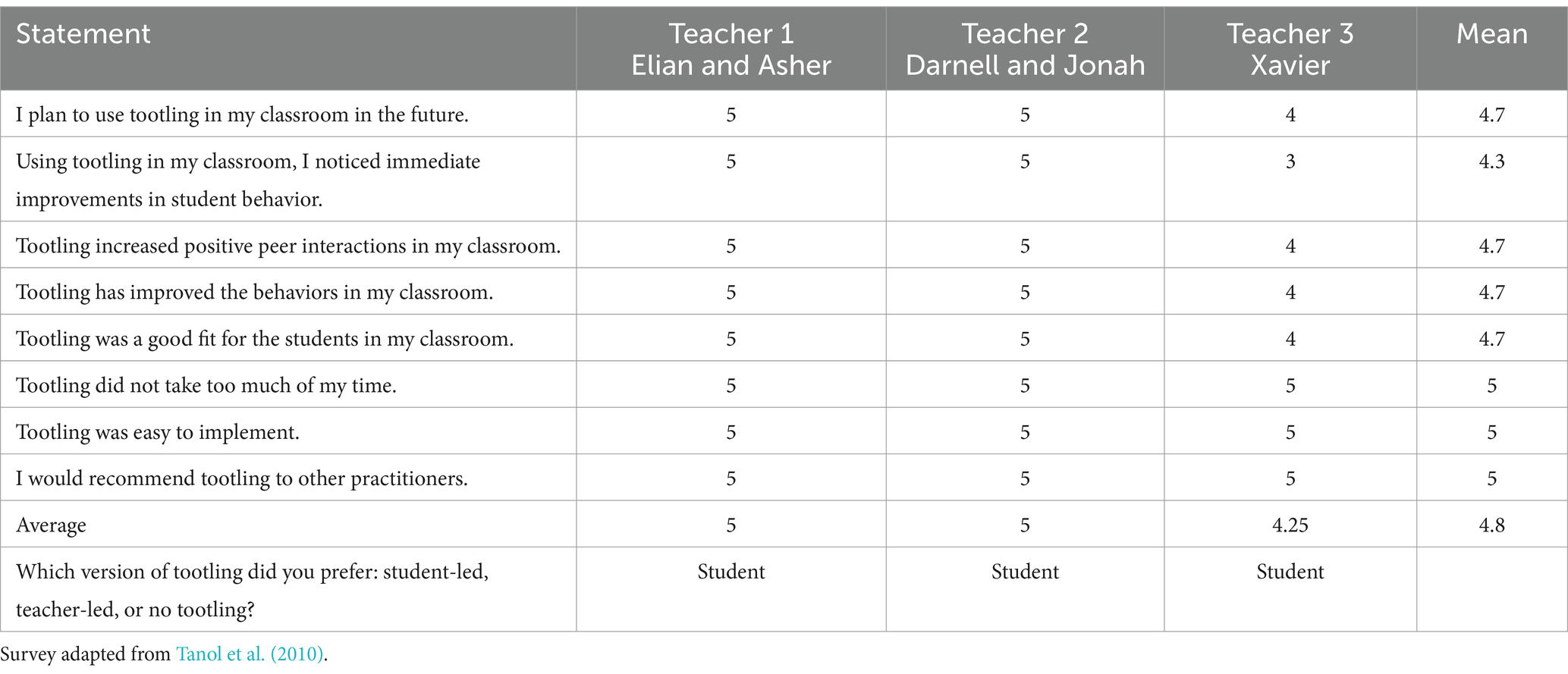

Before and after the study, teachers completed the researcher-created Tootling Efficacy Questionnaire, rating seven statements on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The statements were (a) Tootling is likely to be effective for elementary teachers, (b) Tootling is likely to be effective for my students this semester, (c) Teachers are likely to be comfortable implementing Tootling, (d) I will be comfortable implementing Tootling, (e) Most teachers would find Tootling to be time-efficient to implement, (f) Tootling will be a time-efficient intervention in my classroom, and (g) Having students implement Tootling will increase student buy-in to the intervention. Teachers also completed the Treatment Acceptability Survey for Teachers, adapted from Tanol et al. (2010), after the study. Teachers answered an open-ended question on their preferred variation of Tootling and why, then rated eight items on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree): (a) I plan to use tootling in my classroom in the future, (b) Using tootling in my classroom, I noticed immediate improvements in students’ behaviors, (c) Tootling increased positive peer interactions in my classroom, (d) Tootling has improved the behaviors in my classroom, (e) Tootling was a good fit for the students in my classroom, (f) Tootling did not take too much of my time, (g) Tootling was easy to implement, and (h) I would recommend tootling to other practitioners. Higher scores indicated higher acceptability.

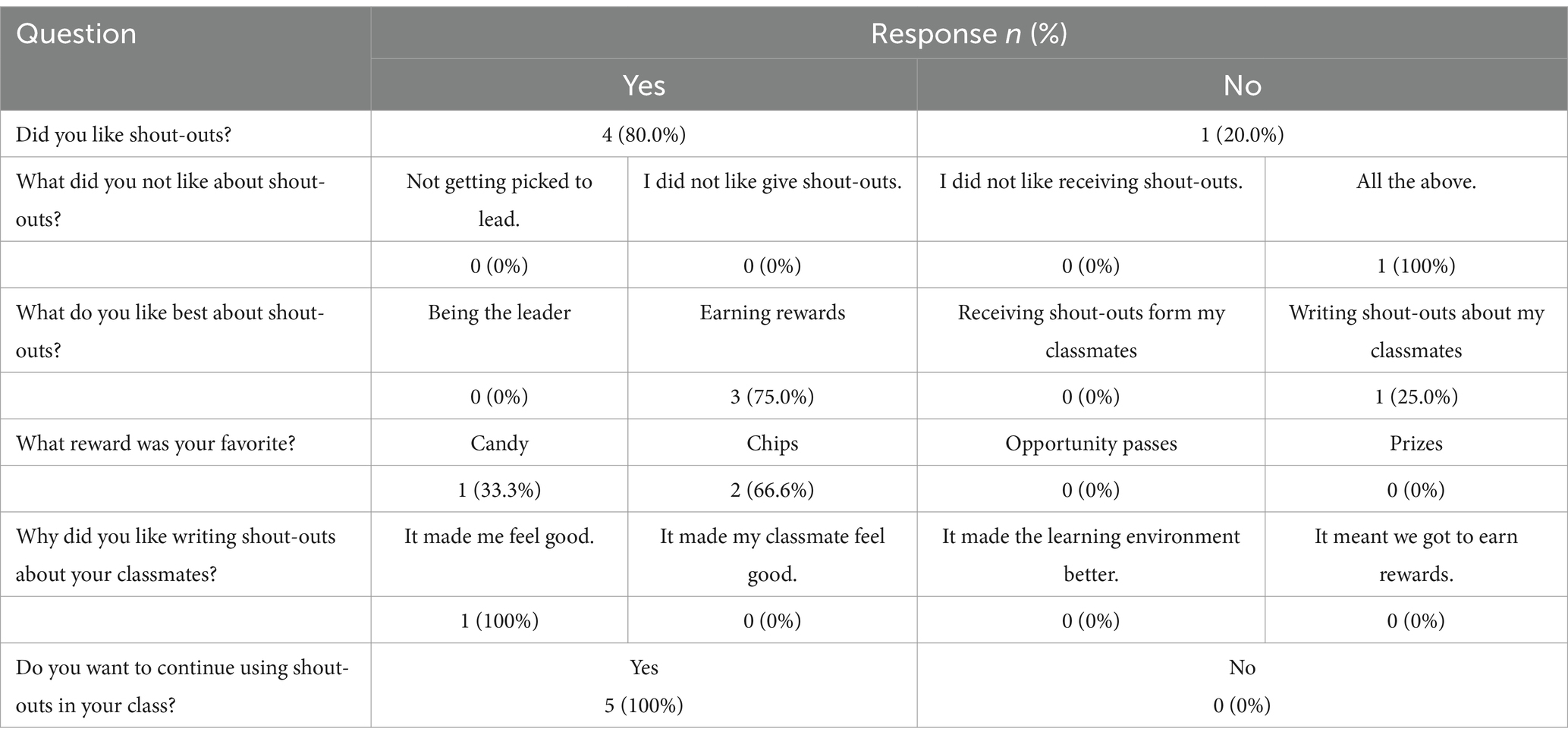

Following completion of the study, students received the researcher created multiple choice Treatment Acceptability Questionnaire for Students via Qualtrics, which began with a force-choice question, Did you like Tootling? then branched to an additional two or three questions depending on a ‘no’ or ‘yes’ response, such as What did you like/not like about Tootling? and Do you want to continue to use Tootling in your classroom?

Procedures

Teacher and student training

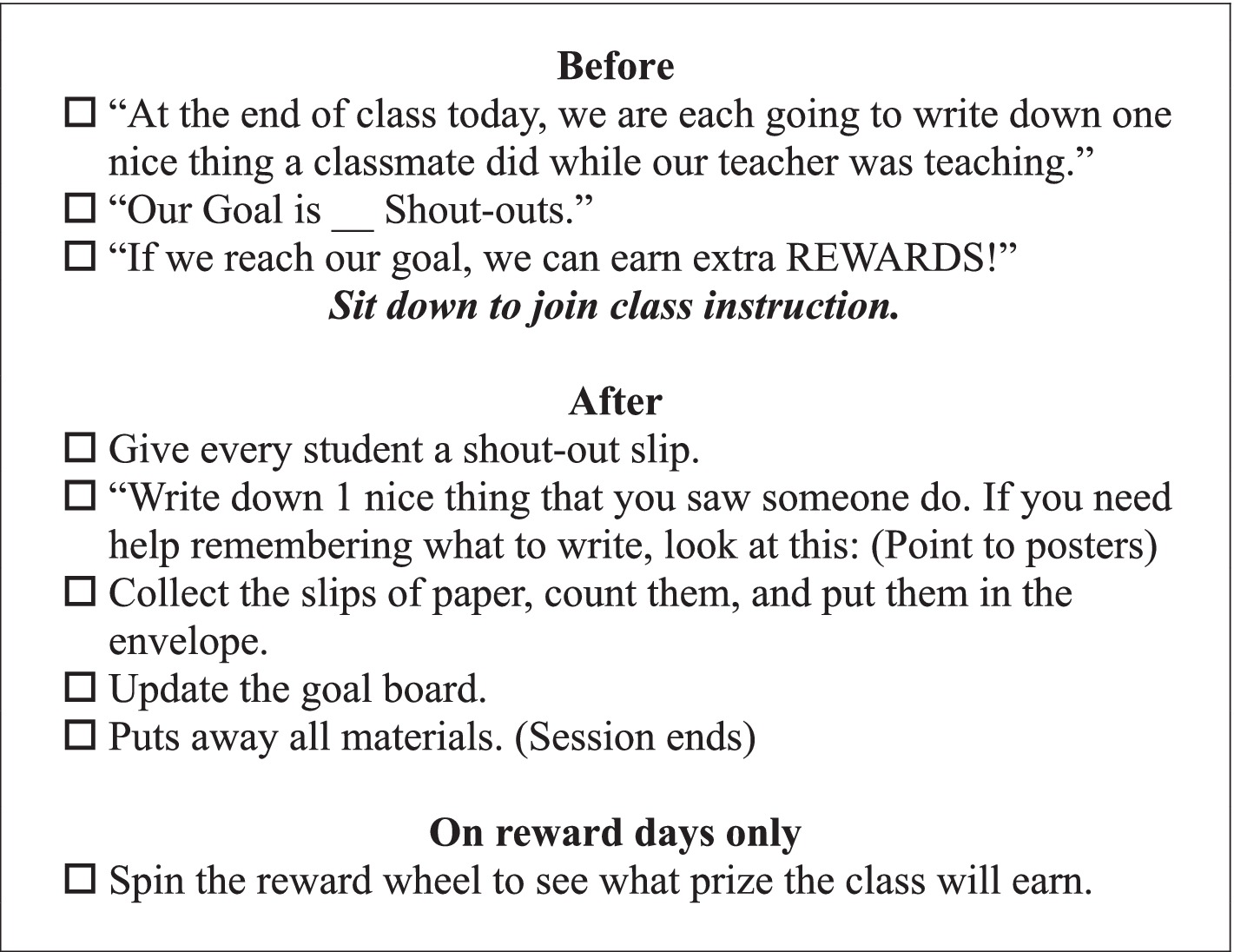

We secured all necessary university institutional review board, district, and school permissions before obtaining the principal’s classroom referrals and teachers’ student referrals, whom we then screened for eligibility (see Participants). We met with teachers to explain the procedures, identify the most problematic time of day, generate a list of potential student reinforcers, and change the name from Tootling to Shout-outs to make it more appealing to students. In Classroom 1, Tootling occurred during English language arts (ELA) and lasted 45 min; in Classroom 2, it took place during ELA and lasted 60 min; and in Classroom 3, Tootling occurred during science, lasting 40 min. We used Behavior Skills Training (Miltenberger, 2012) to instruct teachers and students on Tootling procedures. Training included information on (a) what are prosocial classroom behaviors, (b) the rules of Tootling, (c) the criteria for winning, (d) procedures for counting and recording the number of Tootles after a session, and (e) procedures for receiving the reward if the criterion is met. We modeled the Tootling procedures, two students and their teacher practiced using the script (Figure 2), and we provided praise and corrective feedback. Students then practiced writing a Tootle. The teacher randomly selected five Tootles to review, praising correct Tootles and providing corrective feedback for missing criteria.

After training, students voted on reinforcers. Items with the highest number of class and target student votes (we ensured target students’ top choices were included as options) for each class were entered into separate Picker Wheel (pickerwheel.com) online spinner to randomly select the reward students received when the class goal was met. Each day for 20 days, one of four conditions was then applied—baseline (i.e., no Tootling), student-led Tootling, teacher-led Tootling, and student choice. Each week, teachers assigned every student a “shout-out” partner. This arraignment increased the chances of target students receiving a tootle, as their partners were more likely to notice the positive behavior of a single student rather than an entire classroom. Partners reported on each other’s behavior. During all Tootling conditions, all target students received a Tootle. Tootling conditions were written on a calendar in each classroom. When students were seated and ready to begin instruction, the teacher announced the Tootling condition for that day.

Baseline

In the baseline conditions, teachers informed students they would be taking a break from Tootling that day. We directed teachers to deliver their usual instruction and maintain their existing behavior management systems (i.e., ClassDojo).

Student-led and teacher-implemented tootling

The teacher- and student-led Tootling conditions were identical, all that differed was the person leading the intervention. In the teacher-led condition, the teacher placed the white-paw on the Tootling whiteboard, signifying it was a teacher-led day. If it was a student-led day, the teacher randomly selected a green paw from the bag of student names, and the selected student would lead Tootling procedures. Students who did not want to lead said “pass,” and another student was selected.

At the beginning of ELA or science, the leader (teacher or student) read the script (Figure 2), which reminded students to look for their peers’ prosocial behaviors and reiterated the class goal to earn the reward. At the end of ELA or science, the leader distributed Tootle slips (Figure 1) and read the instructions, collected Tootles, counted them, and updated the Tootling goal progress on the whiteboard.

Next, the teacher randomly selected three Tootle slips to read aloud and praised the recipient of the Tootle and the person who Tootled. If the teacher pulled a slip that did not meet the criteria, the slip was set aside, and another slip was drawn, and that Tootle was not counted toward the class goal. Students who wrote Tootles that did not meet the criteria were given corrective feedback privately from the teacher or researcher. If the goal was met, the Tootling leader spun the Picker Wheel. The class immediately received the reward.

Goals were established prior to the study to allow students to earn the group reward approximately twice a week. Prior research demonstrated that reinforcement twice a week was sufficient to achieve desirable intervention effects (Cihak et al., 2009; Lambert et al., 2015). Class A’s weekly goal was 40 tootles, and Class B and C had a goal of 42.

For each intervention session, the researcher quality-checked the completed Tootles to ensure that the written Tootles that counted toward the reward met the criteria. On average, 95.0% of submitted Tootles across all sessions met the criteria. When classes met their goals, the teacher placed the Tootling slips in students’ folders to go home to their parents. During Tootling conditions, teachers continued using ClassDojo and introduced Tootling as an additional reward system.

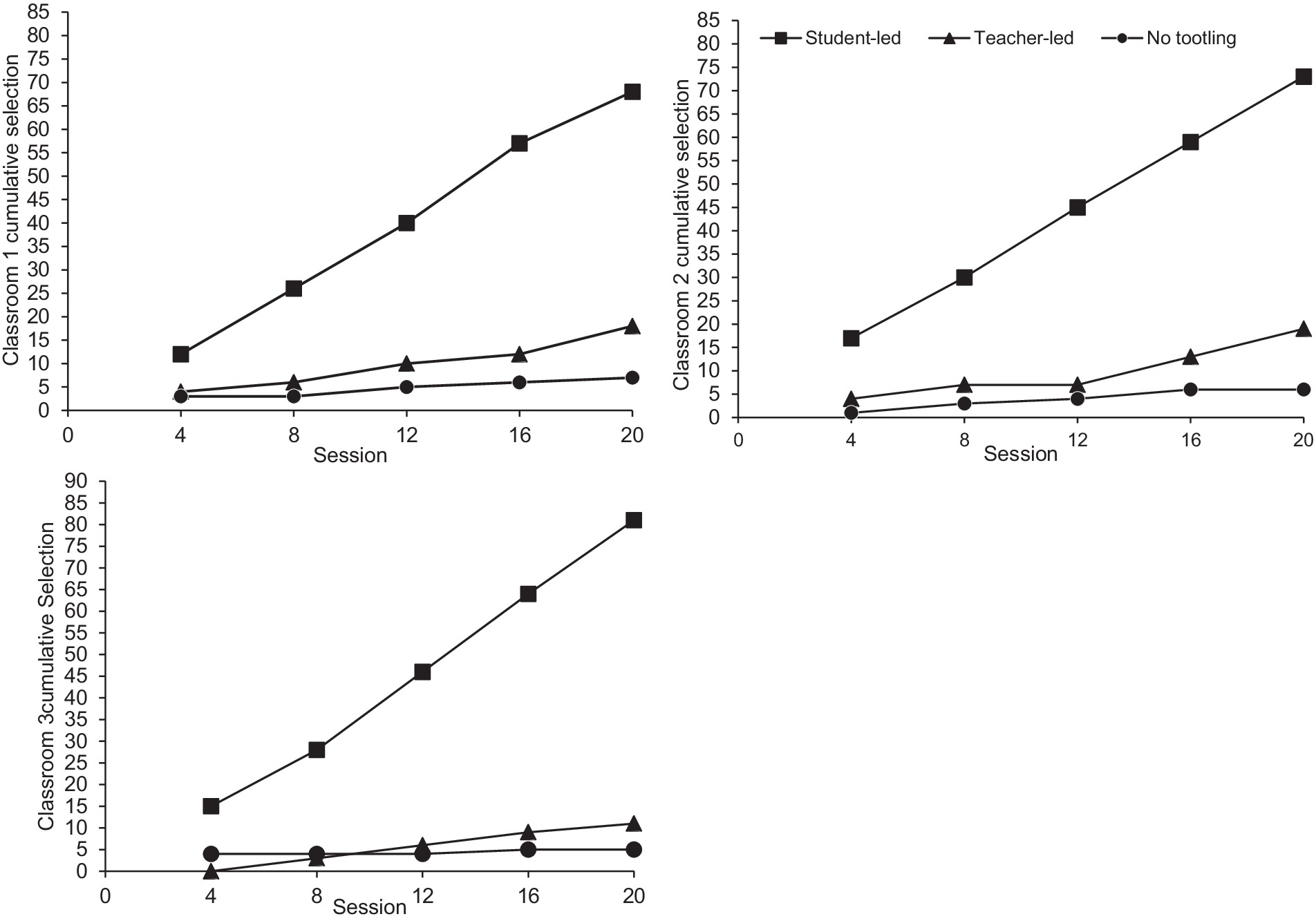

Student choice

Based on the method established by Layer et al. (2008), a group-based concurrent chain preference assessment was used to evaluate students’ preferences for Tootling procedures. Every fourth session, all students voted on which version of Tootling they preferred by selecting one colored paper square and placing it in a bag: student-led (green), teacher-led (white), or no tootling (black). Then, the researcher drew one square of paper, and the color determined the Tootling condition for that day. Randomization incentivized students with the minority selection to persist in choosing the condition they preferred (Layer et al., 2008; Peltier et al., 2022).

Maintenance

Classes moved into the maintenance phase after students experienced each of the four conditions five times. During maintenance, teachers were encouraged to continue implementing the version of Tootling most preferred by the class, as indicated by the votes taken during previous choice conditions; all teachers implemented student-led Tootling. Maintenance sessions were collected 13 and 20 days following the completion of the study without notifying teachers in advance when the researcher was coming.

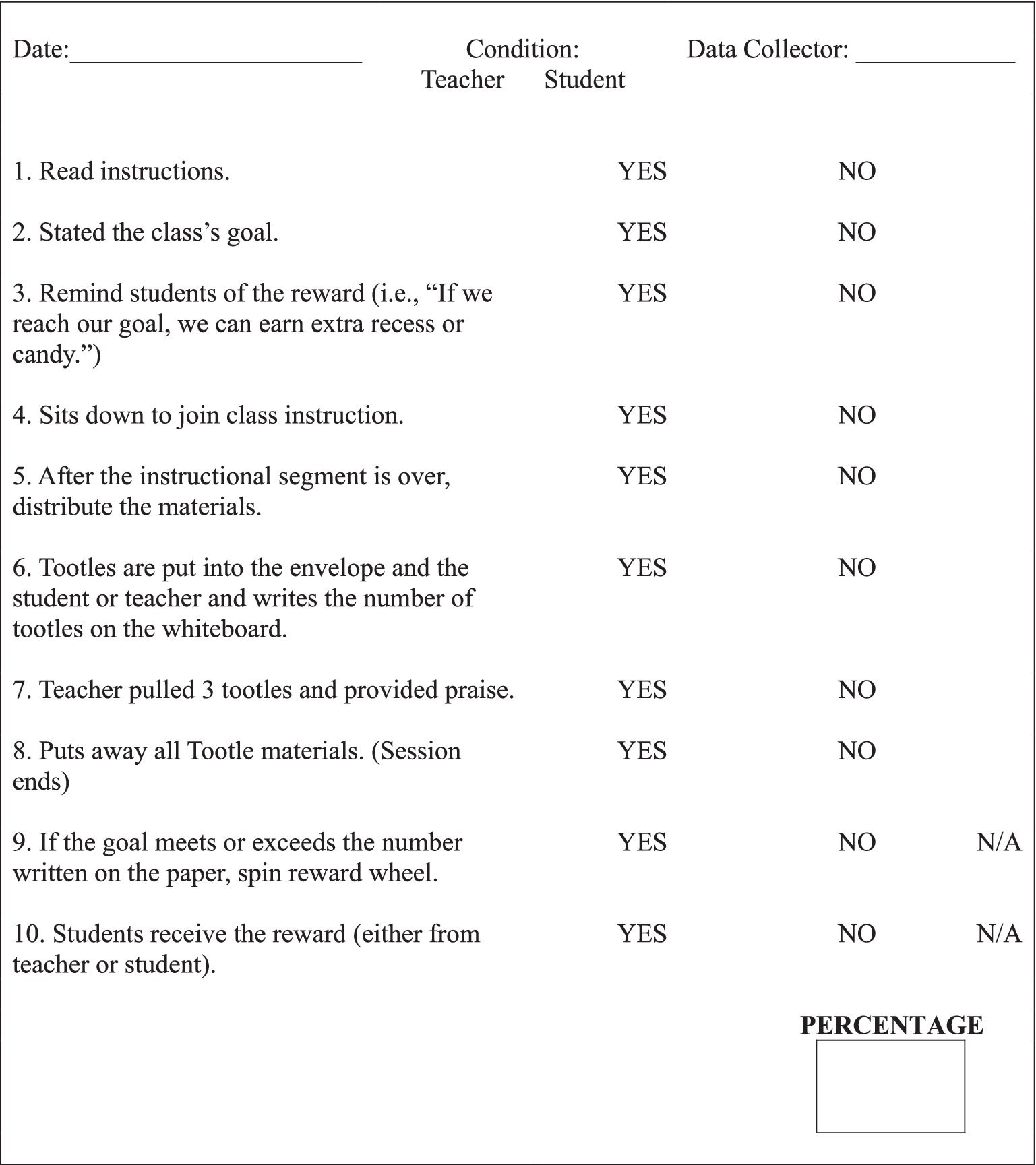

Procedural fidelity

The primary observer collected procedural fidelity data using a checklist (Figure 3) in Classroom 1 for 87.5% of intervention sessions and 81.5% of sessions in Classrooms 2 and 3, distributed evenly across all observations and including maintenance phase sessions. Procedural fidelity was calculated by totaling the number of steps marked with a “yes” divided by the total number of checklist steps and multiplied by 100. In Classroom 1, mean fidelity for teacher-led condition was 100, 98.0% for student-led (range = 87.5–100%), and 100% during the choice condition. In Classroom 2, mean fidelity for teacher-led condition was 96.7% (range = 90.0–100%), 93.6% for student-led (range = 88–100%), and 100% during the choice condition. In Classroom 3 mean fidelity for the teacher-led condition was 89.8% (range = 71.0–100%), 95.6% for student-led (range = 88.0–100%), and 100% during the choice condition. Procedural fidelity fell to 70% during Session 7 in Class 3 because the teacher did not read the script; instead, she told the class they would “do shout-outs today” and had the students pass out the Tootling materials. Following that session, we reviewed Tootling procedures with the teacher and reminded her to use the script. Following Session 7, procedural fidelity remained at 90% or higher. Procedural fidelity was only collected during intervention sessions, which reduces confidence in the outcomes when comparing baseline and treatment conditions.

A secondary observer collected procedural fidelity for 35.7% of sessions in Classroom 1 and 38.5% in Classrooms 2 and 3. IOA was calculated by adding the number of items both raters agreed on and dividing by the total number of items on the checklist, multiplied by 100 (Ledford and Gast, 2018). The mean IOA for procedural fidelity across conditions and classrooms was 100%.

Experimental design and data analytic plan

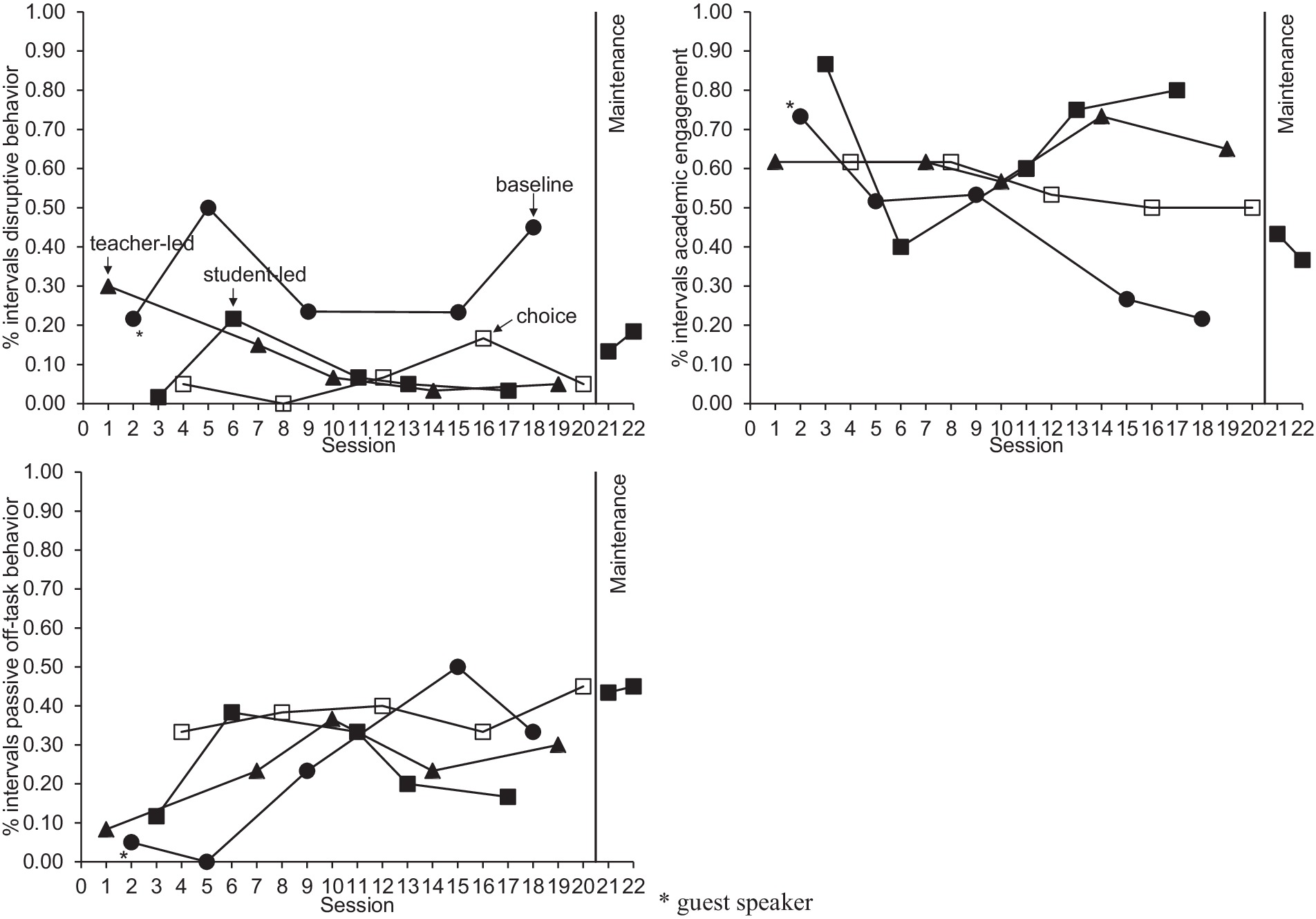

An alternating treatment single-case research design with a maintenance phase was used to compare (a) baseline (i.e., no treatment), (b) student-led Tootling, (c) teacher-led Tootling, and (d) student choice. To guard against sequence effects, we randomized the schedule of conditions, occurring once per day, in systematic blocks (each condition occurring once in a block) by using a random number generator to determine the order of the first three conditions and ending each block with student choice. Having a no-treatment series increases the confidence that changes observed in behavior can be more confidently attributed to the treatment conditions rather than extraneous factors (Skinner et al., 2022). We analyzed results using descriptive statistics and visual analysis of graphed data for level, trend, variability, immediacy of treatment effects, and separation of data paths to identify if changes in the dependent variables were a function of the different treatment conditions (Ledford and Gast, 2018). When visually analyzing the results, we compared treatment conditions to each other and to baseline. By comparing each Tootling condition, we could determine whether student-led Tootling produced differential response patterns compared to teacher-implemented.

Results

Research question no. 1—effects of tootling on behavior

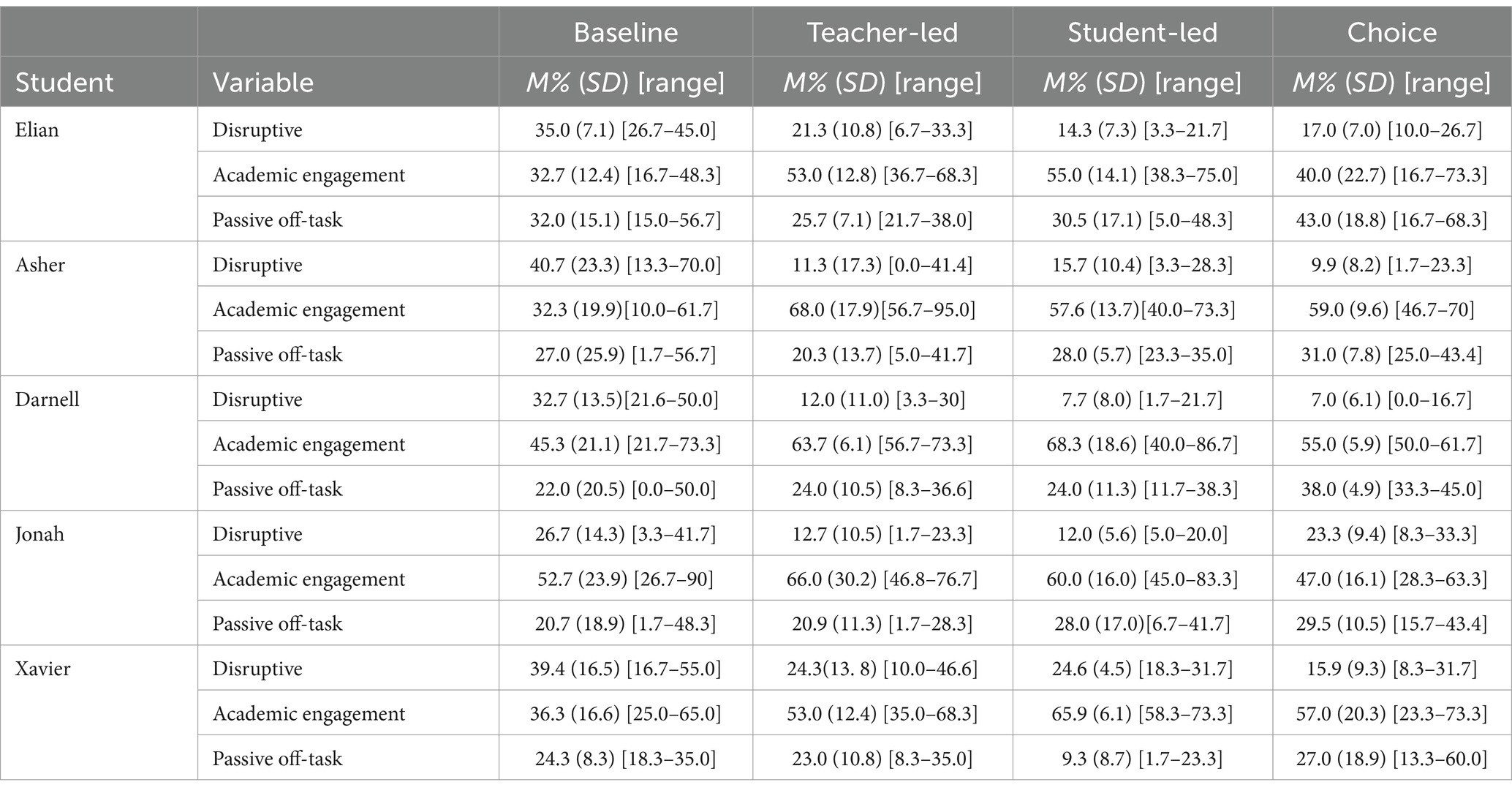

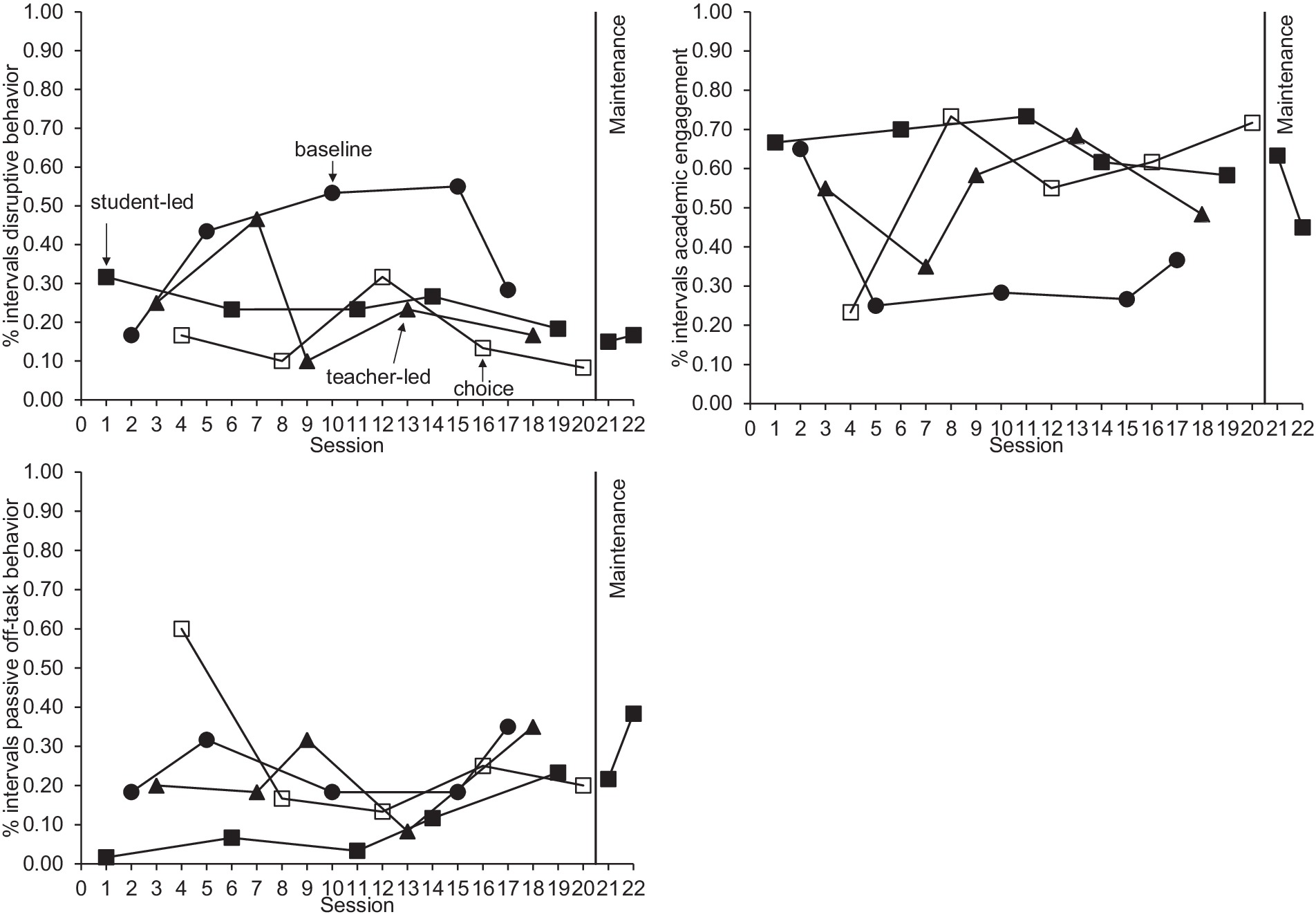

An overall decrease in disruptive behavior occurred across student-led, teacher-led, and student-choice Tootling conditions, while the effects of treatment conditions on academic engagement varied. Tootling did not impact passive off-task behavior. Given the high votes during the student-choice condition, student-led was pulled 100% of the time. The means and ranges of dependent variables across all five participants are presented in Table 1.

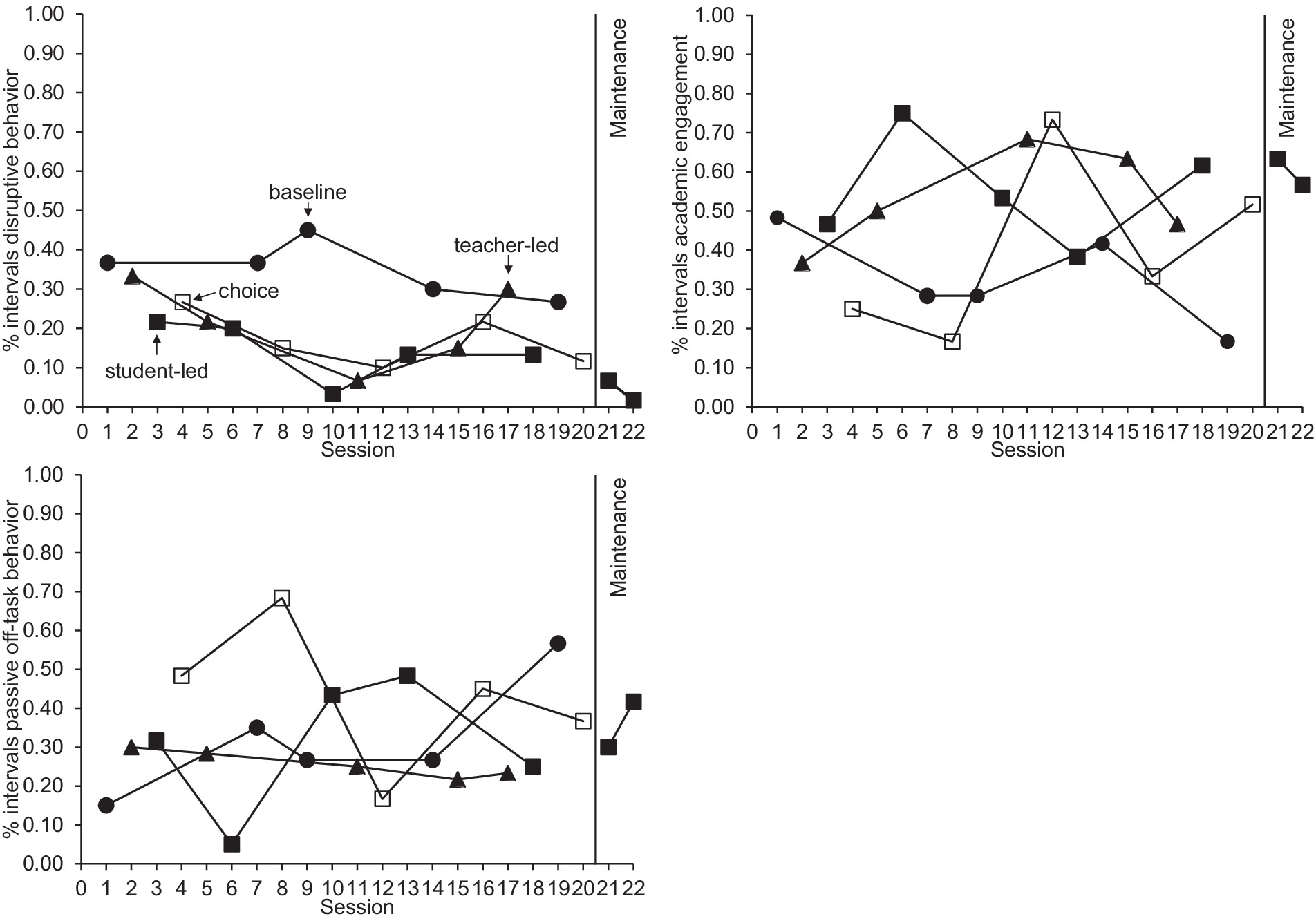

Elian

Disruptive behavior

Elian displayed the highest mean disruptive behavior of 35.1% of intervals (range = 26.7–45.0%) in baseline with a slightly declining trend. Upon introduction of teacher-led Tootling, there was a slight decrease in disruptive behavior, followed by larger decreases in the next four conditions (student-led, teacher-led, and choice), which had a similar level and trend (see Figure 4). Student-led Tootling demonstrated the lowest average disruptive behavior (see Table 1) of 14.3% of intervals (range = 3.3–21.7%), followed closely by the choice condition of 17.0% (range = 10.0–26.7%), where student-led Tootling was always drawn from the bag of student votes. No clear pattern emerged between treatment conditions; however, the student-led condition was marginally more effective. During the student-led maintenance phase, disruptive behavior remained low. Overall, a functional relation between disruptive behavior and Tootling was established by a clear separation between baseline and all Tootling condition data paths.

Academic engagement

Academic engagement across all sessions was highly variable (see Figure 4). Baseline averaged 32.7% (range = 16.7–48.3%) of intervals with a decreasing trend, while all Tootling conditions averaged higher with slightly increasing trends (see Table 1), and the student-led condition averaged highest at 55.0% of intervals (range = 38.3–75.0%). A functional relation was established between teacher- and student-led conditions and disruptive behavior but not choice, where no clear differentiation in data paths emerged. Maintenance data in student-led conditions were slightly higher than in previous student-led Tootling conditions.

Passive off-task

During baseline, Elian engaged in an average of 32.0% of intervals (range = 15.0–56.7%) passive off-task behavior with an increasing trend. A downward trend was observed during teacher-led Tootling, averaging 25.7% (range = 21.7–38.0%). Behavior patterns were highly variable and not clearly separate from baseline in both the student-led and choice conditions (see Figure 4 and Table 1), preventing the establishment of a functional relation. Maintenance data in the student-led condition was comparable to treatment data.

Asher

Disruptive behavior

Similar to Elian, Asher displayed more disruptive behavior in baseline compared to Tootling conditions (choice had the lowest average, see Table 1), with a clear separation (see Figure 5) resulting in a functional relation. Data taken during one student-led maintenance phase session (the student was absent for one maintenance session) was slightly higher than the overall average student-led condition.

Academic engagement

In contrast to Elian, Asher displayed a more distinct separation between baseline academic engagement and all Tootling conditions (see Figure 5 and Table 1), with teacher-led being the highest, resulting in a functional relation. During student-led maintenance, data were similar to previous student-led sessions.

Passive off-task

Passive off-task behavior exhibited similar variability to Elian (see Figure 5) with only teach-led Tootling averaging less than baseline (see Table 1) and no functional relation established. Student-led maintenance sessions were comparable to previous student-led conditions.

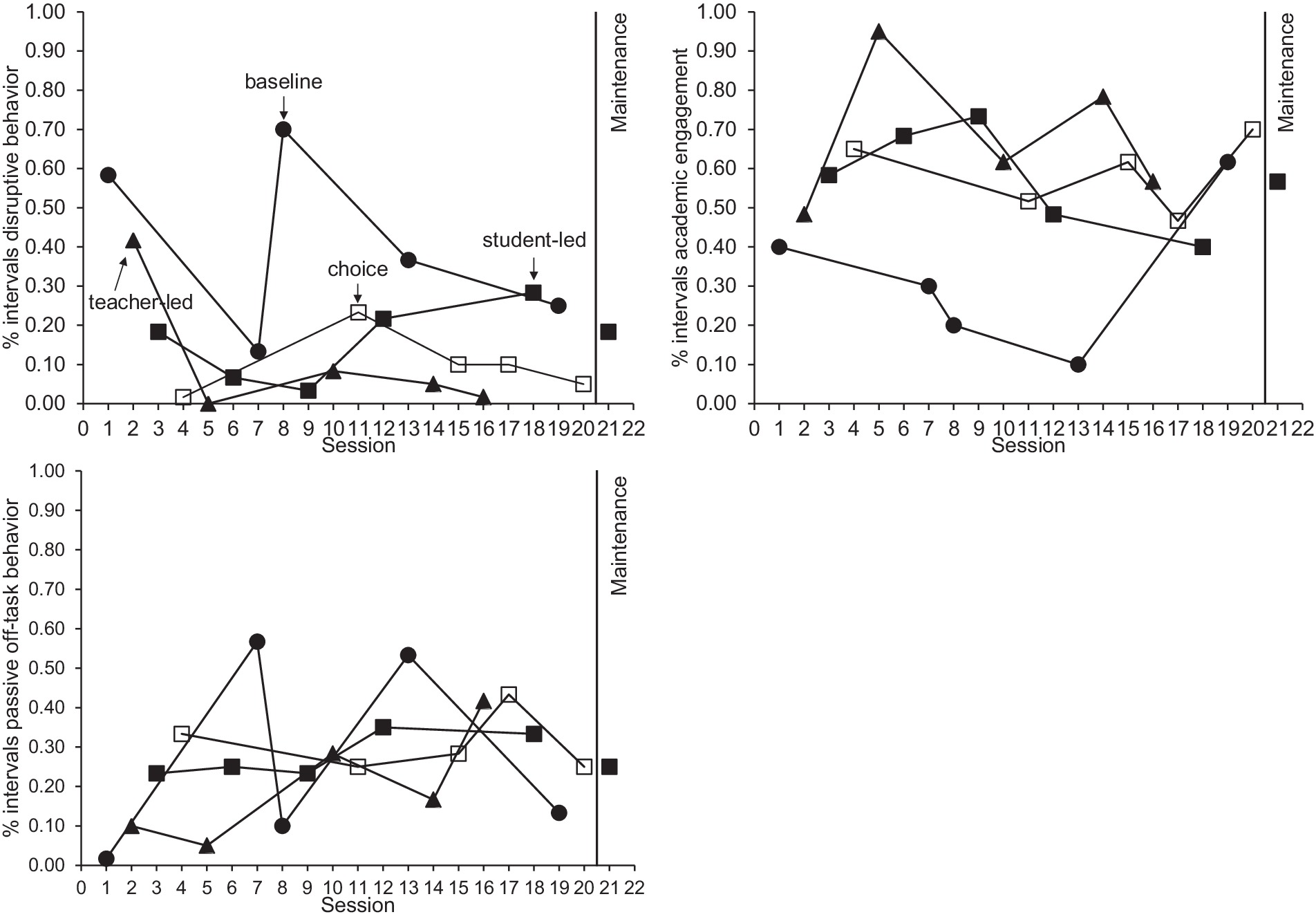

Darnell

Disruptive behavior

Darnell’s disruptive behavior was similar to Elian and Asher’s, higher in baseline and clearly separated from Tootling conditions (see Figure 6), establishing a functional relation, with choice having the lowest average (see Table 1). Although student-led maintenance data suggest an upward trend, disruptive behavior remained lower than baseline.

Figure 6. Darnell’s rates of disruptive behavior, academic engagement, and passive off-task behavior.

Academic engagement

Academic engagement for Darnell was higher in Tootling conditions compared to baseline establishing a functional relation. Teacher-led Tootling had the highest academic engagement, but data points were minimally differentiated from student-led and choice. Student-led maintenance data indicated lower levels of academic engagement than previous student-led Tootling conditions.

Passive off-task

Passive engagement varied across all sessions for Darnell with no clear differentiation between conditions, no functional relation, and averaged higher across all treatment conditions compared with baseline. An increase in passive off-task behavior was exhibited in the student-led maintenance sessions.

Jonah

Disruptive behavior

Disruptive behavior for Jonah averaged higher during baseline compared to Tootling conditions (see Table 1), with choice similar to baseline. Student- and teacher-led Tootling were separated from baseline (see Figure 7) and established a functional relation. Disruptive behavior remained low and stable during student-led maintenance sessions.

Academic engagement

Academic engagement for Jonah was highly variable, similar to Elian. A functional relation was established between student- and teacher-led Tootling but not choice conditions, averaging slightly higher in the teacher-led condition. Data variability in the student-led condition continued during the maintenance phase.

Passive off-task

Jonah’s passive off-task behavior varied significantly across all sessions and conditions similar to Darnell’s, with no clear differentiation in data paths. It averaged higher across all treatment conditions compared with baseline, and no functional relation was established. Data collected during the maintenance phase continued to demonstrate variability in passive off-task behavior.

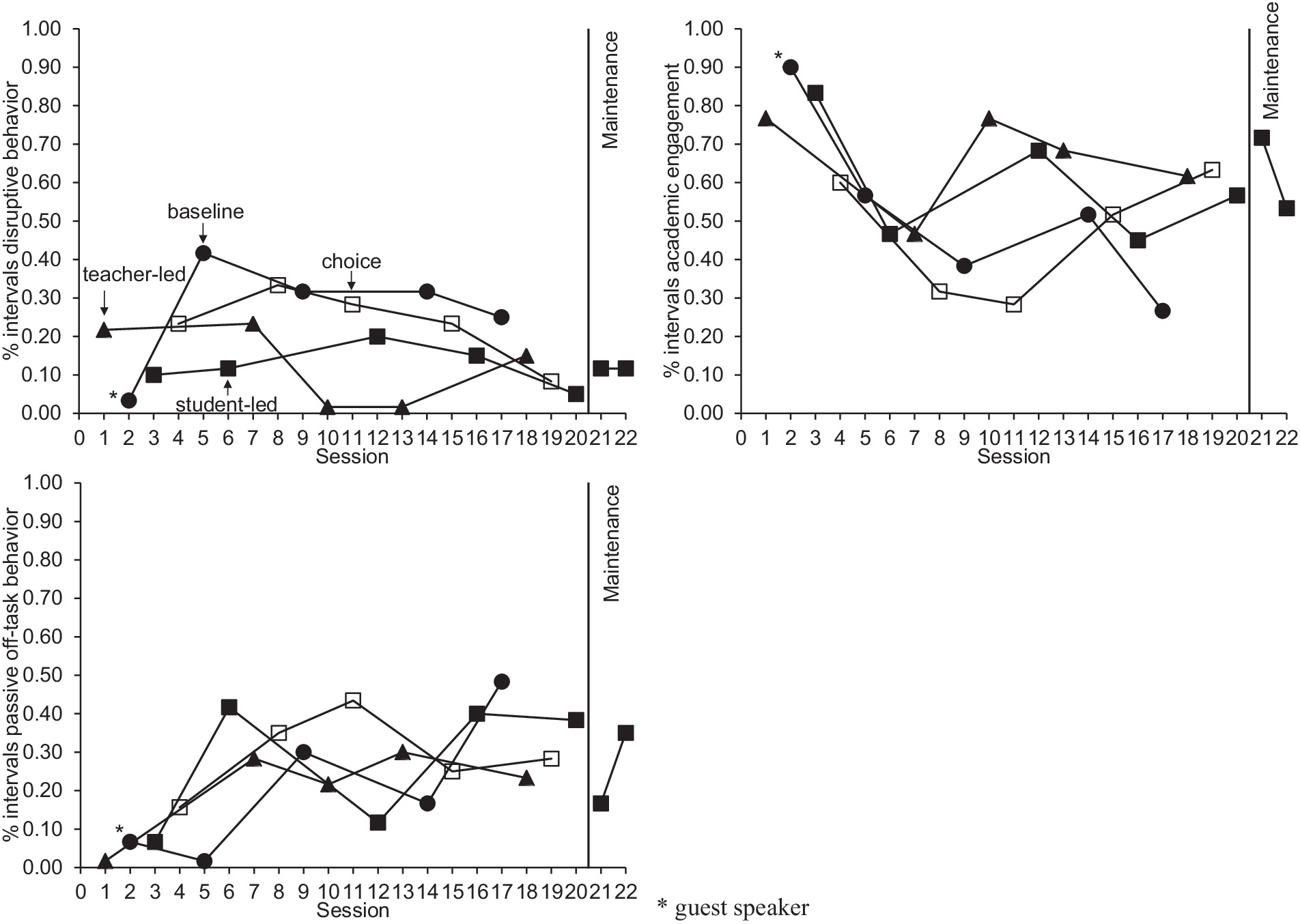

Xavier

Disruptive behavior

Similar to Elian, Xavier’s baseline disruptive behavior was consistently higher than all Tootling conditions (see Figure 8), clearly separated, and established a functional relation. The choice condition demonstrated the lowest average level of disruptive behavior (see Table 1). Disruptive behavior remained low and stable during student-led maintenance sessions.

Figure 8. Xavier’s rates of disruptive behavior, academic engagement, and passive off-task behavior.

Academic engagement

Xavier’s academic engagement was similar to Asher’s, low during baseline and clearly separated from Tootling conditions, establishing a functional relation. In the student-led Tootling condition, academic engagement was highest (see Table 1) with a slight downward trend, then more variable and slightly lower during maintenance sessions.

Passive off-task

Xavier’s passive off-task behavior was more stable than other students across conditions, with minimal differentiation between control and teacher-led conditions and more off-task behavior in choice compared to control (see Figure 8). The least amount of off-task behavior was in the student-led Tootling condition (see Table 1), visually separated from baseline and the only condition establishing a functional relation, with an upward trend that continued during the maintenance phase.

Research question no. 2—preferred tootling condition

All students from all three classrooms strongly preferred the student-led condition (see Figure 9). In terms of target students, Elian and Darnell always voted for student-led, Asher voted twice and Jonah voted once for teacher-led but otherwise voted for student-led, and Xavier voted once for no Tootling, once for student-led, and the remaining three times for teacher-led Tootling. On the Treatment Acceptability Survey for Teachers open-ended question, all three teachers expressed a preference for student-led tootling. Teacher 1 wrote, “I like giving the students ownership in our classroom and learning to be active listeners with their peers.” Teacher 2 noted, “Any opportunity to give ownership and responsibility to students is wonderful. It also took the responsibility of remembering from me because students would remind me.” Teacher 3 indicated, “Students seemed to enjoy being in charge.”

Research question no. 3—social validity

Average scores on the Tootling Efficacy Questionnaire administered to teachers before and after the study (Table 2) marginally improved, indicating the intervention met or exceeded expectations. Teacher 1 pre- and post-assessment scores averaged 4.9 and 5.0 out of 5, while Teacher 2 scored the maximum mean of 5.0 for pre- and post-test. In contrast, Teacher 3’s scores improved from pre (M = 3.8) to post (M = 4.1).

Teachers’ mean post-study scores on the Treatment Acceptability Survey for Teachers (Table 3) was 4.8 out of 5, suggesting teachers strongly agreed Tootling was an acceptable and effective intervention for their classrooms. Teachers 1 and 2 “strongly agreed” with all statements, whereas Teacher 3 agreed or strongly agreed to all but “Using tootling in my classroom, I noticed immediate improvements in student behavior.”

Four out of five target students’ results on the post-study Treatment Acceptability Questionnaire (Table 4) indicated they liked the Tootling intervention. Three of those four indicated the best thing was earning rewards and choosing chips and candy. One student indicated the best thing about shout-outs (Tootles) was writing shout-outs about his classmates because it made him feel good. All five target students wanted to continue to use shout-outs in their classrooms.

In terms of the 63 non-target students, across the classrooms, 95.2% (n = 60) liked shout-outs (Table 5). The vast majority of these (n = 37, 61.7%) chose earning rewards as what they liked best about shout-outs, with chips being the most popular choice of reward (n = 20, 54.1%) followed by opportunity passes (n = 8, 21.6%), candy (n = 5, 13.5%), and prizes (n = 4, 10.8%). Twelve students (20.0%) chose receiving shout-outs from their peers because “it made them feel happy” (n = 4, 33.3%), “it made them feel like they were doing well in class” (n = 5, 41.7%), or they liked that their parents got to see the shout-outs in their folder (n = 3, 25.0%). Ten students (16.7%) chose writing shout-outs about their classmates because it made them feel good (n = 3, 30.0%) or it made their classmates feel good (n = 6, 60%; one student left this blank). One student (1.7%) chose being the leader because this role allowed them to read the script and run the game. Only two of 63 students (3.2%) expressed a desire to discontinue the use of shout-outs, while almost all students (n = 61, 96.8%) wanted to continue using them in their classrooms.

Research question no. 4—continued use of tootling

Thirteen days and 21 days following the removal of researcher support, maintenance data were collected; student-led Tootling was being implemented in all classrooms. Maintenance fidelity averaged either 100% (Classrooms 1 and 2) or 88.0% (Classroom 3). On the second day of maintenance in Classroom 3, the teacher did not read the shout-outs, and the students did not update the goal because they were late for lunch. However, the teacher indicated that it would happen after lunch. Classroom 1 changed its goal from 40 to 62 and Classroom 2 changed from 42 to 50, as indicated by Tootling whiteboards. Students in Classroom 1 told the researcher they earned chips the prior week, Classroom 2’s teacher said they did shout-outs three times the previous week, and students in Classroom 3 told the researcher they earned a reward on Monday.

Discussion

This study used an alternating treatment single-case design to evaluate the effects of student-led Tootling as a class-wide intervention aimed at reducing disruptive behaviors among students with or at risk for disabilities. The first research question focused on comparing and evaluating the effects of teacher-led, student-led, and a choice condition of a Tootling implementation. The second set of research questions explored students’ and teachers’ acceptability of preferences for Tootling.

Effects of tootling conditions

A visual analysis of all five target students indicated both teacher-led and student-led (including choice) conditions decreased the percentage of intervals target students engaged in disruptive behavior. Further, the results from teacher- and student-led Tootling are consistent with previous studies evaluating the effects of Tootling on disruptive behavior (Cihak et al., 2009; Lipscomb et al., 2018; McHugh et al., 2016). These findings contribute evidence that Tootling can be effective in reducing disruptive behaviors of upper elementary school students.

Both teacher-led and student-led Tootling conditions notably increased the percentage of time all five participants were academically engaged. Although increased levels were observed in mean levels of academic engagement time during the student-and teacher-led conditions compared to baseline, visual analysis revealed considerable variability in the data across all participants and should be viewed cautiously.

For example, during the initial two treatment sessions, Darnell and Asher displayed vastly different levels of academic engagement. Darnell’s academic engagement was 86.6% in the first student-led session and 40% in the second student-led session. Levels of academic engagement stabilized following Session 9. Asher’s level of academic engagement during the first teacher-led session was 48.3%, increasing to 95% during the second teacher-led session, with patterns of variability evident across all treatment conditions. Similar patterns of highs and lows of academic engagement were observed for Elian, Jonah, and Xavier.

Previous studies reported substantial increases and less variability in levels of academic engagement; however, data for those studies were analyzed at the class level rather than at the individual level and did not use an alternating treatments design (Chaffee et al., 2020; Harry et al., 2021; Lum et al., 2017; Lum et al., 2019). Only one other study measured the impact of Tootling on individual students’ academic engagement, which also reported high variability in individual students’ levels of academic engagement (McHugh et al., 2016). Class-level data were collected by observing groups of students using individual-fixed or individual-random methods (Briesch et al., 2014) where a different student in the class was observed during each interval, and an overall percentage of observed intervals was calculated for each session, representing the level of academic engagement across the entire classroom (Chaffee et al., 2020; Harry et al., 2021; Lum et al., 2017). Observing a different individual for each interval may lead to a student being observed only 5 to 6 times and does not reveal how Tootling impacts students who are regularly disengaged, which was the target question for this study.

A comparison between student-led and teacher-led conditions across all participants revealed a 3.4% difference in means, suggesting no meaningful difference in treatment effects. The similar results for the two conditions were not surprising, given the procedures and behavioral mechanisms for each condition were the same regardless of who was leading the intervention. That is, the leader stated the criterion to the class (antecedent), and when the criterion was met (student prosocial behaviors), delayed positive reinforcement (consequence) was provided to students. These results align with previous research comparing the effects of teacher- and student-led GBG, where student-led sessions decreased behavior as much as teacher-led implementations of the game (Donaldson et al., 2018; Peltier et al., 2022). Findings from this study add to a growing body of research demonstrating the viability of student-led, class-wide behavioral interventions.

Both teacher-led and student-led conditions were effective in increasing academic engagement for Elian, Darnell, and Jonah. When comparing the student-led to the teacher-led conditions across these three participants, there was only a 4.1% difference between the means, suggesting no meaningful difference in treatment effects. In other words, one condition was not more effective than the other; academic engagement improved from baseline for both teacher- and student-led implementations.

However, for Asher, the teacher-led condition was more effective in increasing his academic engagement. The mean difference between baseline and the teacher-led conditions was 35.7% compared to the mean difference between baseline and the student-led conditions of 25.4%. Thus, Asher was more engaged during the teacher-led conditions. Conversely, the student-led condition was more effective in increasing academic engagement for Xavier. The mean difference between the baseline and the teacher-led condition was 16.7% compared to 29.7% in the student-led condition. Xavier was more engaged during student-led sessions.

This is the first study to explore the impact of student-led behavioral interventions on academic engagement. Tootling may effectively increase the classroom average of academic engagement (Chaffee et al., 2020; Lum et al., 2017), but its impact on individual students is less understood. Given the mixed results observed, further research is needed to better understand the effects of student-led Tootling on students’ academic engagement.

Student choice

The effectiveness of student choice of condition in reducing disruptive behavior varied across participants. Student choice was not more effective in decreasing disruptive behavior for Elian, Asher, and Darnell. Analysis revealed that for those students, the choice condition—when the class was allowed to choose who led the Tootling procedure for the day—produced similar results as the student- and teacher-led conditions when there was no choice. The similarity in results between the choice and treatment conditions aligns with the findings of Peltier et al. (2022) when they added a choice condition to the implementation of the GBG and rates of disruptive behavior did not differ relative to teacher- and student-led conditions.

Jonah and Xavier’s rates of behavior during choice were not consistent with teacher- and student-led conditions. Specifically, Jonah’s behavior during choice was similar to baseline levels of disruptive behavior. Conversely, Xavier experienced a meaningful reduction in disruptive behavior during choice compared to baseline, teacher-led, and student-led conditions. These results are inconsistent with prior research on choice and class-wide behavioral intervention implementation (e.g., Donaldson et al., 2018; Peltier et al., 2022).

Given that having a choice about who was leading the intervention either did not produce an additional value-added improvement in behavior beyond that of the intervention itself (n = 3) or it produced a modest, positive effect (n = 1), adding choice to an intervention does not appear harmful, but may not be a particularly potent component. The reduced efficacy of the intervention when a choice was added for one student, though, should be noted. The mixed results of the choice condition point to the potential of further investigation into the efficacy of student choice for Tootling conditions on the disruptive behavior of individual students.

Social validity

Students overwhelmingly preferred student-led Tootling, as evidenced by consistent results from the concurrent chain preference assessments (i.e., voting). Both target and non-target students displayed a clear preference for Tootling over no Tootling, with most preferring the student-led condition. Preference for and high acceptability of Tootling aligns with previous studies measuring student preferences (Harry et al., 2021; McHugh et al., 2016) and that measured student preferences for the GBG (Peltier et al., 2022). This study was the first to explore reasons for students’ preferences for Tootling. Although most students indicated earning rewards as a top reason, others identified receiving tootles from peers and writing tootles for their peers as the best parts of the intervention. This suggests that for many students, reinforcement was not only provided through the reward contingency but also through the writing and receiving of Tootles. Future research can employ similar social validity methods to gather real-time data (i.e., voting) and explore why students prefer certain interventions.

Though all three teachers expressed a preference for student-led Tootling, Donaldson et al. (2018) and Peltier et al. (2022) found teacher preferences for who led the GBG were mixed: some teachers preferred teacher-led, some preferred both versions, and others had no specific preference. Peltier et al. reported teachers perceived teacher-led GBG as more effective and felt students did not take the game seriously when led by another student.

Two factors may have influenced the difference between prior research and the current study. First, previous studies on student-led GBG were in kindergarten (Donaldson et al., 2018) and first and second grade (Peltier et al., 2022) compared to the current study’s upper elementary students who probably required less support. Second, the GBG is more complex than student-led Tootling (e.g., in the GBG, one must concurrently observe students and assign points).

Surveys

All three teachers found Tootling acceptable and effective. Teacher 3 rated her perception of its effectiveness slightly lower than Teachers 1 and 2. Specifically, on the pre-assessment, she gave lower scores in response to the prompt: “Tootling is likely to be effective for my students this semester, and I am comfortable implementing Tootling.” It is possible Teacher 3’s confidence in implementing Tootling contributed to her skepticism about the effectiveness of Tootling in decreasing disruptive behaviors. In general, teachers’ reported acceptability and perceived effectiveness of Tootling align with previous research, which has consistently documented teachers rate Tootling as highly acceptable for their classrooms (Cihak et al., 2009; Lambert et al., 2015; McHugh et al., 2016) but that teachers did not strongly agree on the intervention effects (McHugh Dillion et al., 2019). Further research is needed to understand the discrepancies observed between teachers’ acceptability of Tootling and their perceptions of intervention effects.

Maintained implementation of tootling

Following the withdrawal of researcher support, teachers continued using student-led Tootling with high fidelity, further evidence of the social validity of student-led Tootling. Findings from this study align with those of Lambert et al. (2015), who found teachers continued to use tootling during follow-up. However, they contrast with Lum et al. (2017), where all three participating teachers expressed they would continue to use tootling, yet none did during follow-up.

Implications

Findings from this study demonstrated that student-led Tootling resulted in decreased disruptive behavior similar to teacher-led Tootling with only a nominal differences, suggesting student-led Tootling is an effective classroom-wide behavioral intervention teachers can use to decrease the disruptive behaviors of individual students with or at risk for disabilities. Additionally, all five participants increased their academic engagement during student-led and teacher-led Tootling (although academic engagement was reduced during the choice condition for one student, Jonah). Additionally, allowing students to take responsibility for the intervention supports the feasibility and sustaining of student-led Tootling in the classroom, addressing a common limitation of many behavioral interventions (Chaffee et al., 2020; Lum et al., 2017). During the maintenance phase, teachers noted students reminded teachers about Tootling, leading to students being assigned roles in managing weekly Tootling procedures. In elementary classrooms, it is common for teachers to delegate class jobs to students. Teachers implementing student-led Tootling can adopt the same method of assigning a class job to integrate Tootling in their classrooms.

Student-led Tootling may be particularly appealing to teachers with students needing Tier 2 behavioral support in PBIS schools (Sailor et al., 2009). Not only is Tootling effective at the class-wide level (Harry et al., 2021; Lambert et al., 2015. McHugh Dillion et al., 2019), but the findings of this study suggest student-led Tooting can be used to support students who require behavior supports in addition to the Tier 1 supports already put into place. The implementation of student-led Tootling reduced the disruptive behaviors of Darnell and Xavier, both of whom were referred for Tier 2 behavioral support. Student-led Tootling required few teacher resources (i.e., time and energy) compared with using individualized behavior charts, and encouraged the class to work toward a shared goal and avoid the need to single out individual students.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the researcher did not collect procedural fidelity during baseline conditions. Although anecdotal reports indicated the absence of Tootling during baseline conditions and the researcher applied control variables (i.e., same time of day, same subject), the absence of procedural fidelity collection during baseline means there is no evidence to confirm the similarity of baseline conditions. This reduces our confidence in functional relations and increases the risk of bias (Ledford and Gast, 2018).

Another limitation of this study is on several occasions, the teacher in Class 1 supported the students’ implementation of Tootling, and only some students were fully independent in leading each session. The number of prompts and the intensity of the support for those students were not measured. Without measuring the level of support provided, there is a risk of not fully understanding the extent to which students were independent and competent in leading the Tootling sessions.

Finally, although any Tootling slip a student received during the game was placed in the student’s folder that was sent home, the researcher did not collect data on the fidelity of the implementation of this procedure. As a result, it is not known if parents received the Tootling slips. However, three students noted in the social validity questionnaire they liked that their parents saw their Tootling slips. If parents consistently received Tootling slips, students may have received additional reinforcement for the behavior, which could have been an influential variable in student behavior (Fabiano et al., 2010). Understanding the impact of parents receiving Tootling slips can boost parent involvement in Tootling procedures and is a potential area for future research.

Directions for future research

Further investigations into the implementation of student-led Tootling could yield valuable insights into optimal methods for implementation in classrooms that include students with or at risk for disabilities. One important next step would be to evaluate the feasibility of student-led Tootling in early elementary classrooms. This study included upper-elementary school students, and both teachers and students preferred the student-led version. Replications are necessary to determine the effects and feasibility of student-led Tootling in various settings and grade levels to measure student and teacher preferences.

Another avenue for future research would be to measure the effects of Tootling on teacher behavior. Anecdotally, there was a notable increase in teacher praise in classrooms upon introducing Tootling sessions. Teachers would pause instruction to acknowledge and praise students demonstrating “shout-out worthy” behaviors. Future research could investigate whether implementing student-led Tootling increases teachers’ praise rates compared with baseline. High rates of teacher praise are associated with lower rates of off-task behaviors (Floress et al., 2018) and decreased disruptive behavior (Caldarella et al., 2023). Moreover, high rates of teacher praise correlate with higher rates of student engagement, especially for those at risk for disabilities (Caldarella et al., 2019). Examining how Tootling influences teacher behavior could bolster its efficacy as an intervention if the secondary effects increase teachers’ praise. If there is no discernable change, training teachers to identify appropriate behaviors could become an important training component of tootling.

Despite the observed decrease in disruptive behavior and increases in academic engagement resulting from Tootling, teachers do not always perceive the intervention as effective. A potential avenue for future research could involve examining the impact of presenting the data to teachers throughout the study. Providing teachers with formative data on intervention outcomes may enhance their perception of intervention effectiveness and increase their confidence in its implementation (Han and Weiss, 2005). As a result, this could improve the sustainability and fidelity of the intervention in classroom settings (Criss et al., 2022).

Finally, future exploration should examine ways to involve parents in Tootling procedures. Regular parent involvement and consistent communication can increase positive school outcomes like improved attendance rates and student achievement (Owens et al., 2012; Murray et al., 2015). Parent and teacher communication is particularly important for students with or at risk for disabilities who engage in challenging behavior. For those students, teacher communication with parents may often be about negative behaviors such as missing assignments or rule infractions. Tootles can be a form of positive notes home and contribute to better parent-teacher relations and communication (Goldman et al., 2019; Howell et al., 2014). Three students liked that their parents saw their Tootling slip in their folder in this study, and future research could investigate ways to track if parents saw tootles and measure the impact.

Conclusion

Teacher- and student-led Tootling can be an effective behavioral support used to decrease the disruptive behavior of students with or at risk for disabilities. Findings from this study demonstrated that student-led Tootling was as effective as teacher-led Tootling in decreasing disruptive behaviors and increasing the academic engagement of individual students. Both students and teachers expressed a preference for student-led Tootling, and teachers continued to use student-led Tootling after the study.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Georgia Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

JT: Conceptualization, Project Administration, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The research described in this article was supported in part by Grant H325190003 from the Office of Special Education Programs, U.S. Department of Education. Nothing in the article necessarily reflects the positions or policies of the federal government, and no official endorsement by it should be inferred.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Barrish, H. H., Saunders, M. S., and Wolf, M. M. (1969). Good behavior game: effects of individual contingencies for group consequences on disruptive behavior in a classroom. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2, 119–124. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1969.2-119

Bettini, E. A., Crockett, J., Brownell, M. T., and Merrill, K. (2016). Relationships between working conditions and special educators’ instruction. J. Spec. Educ. 50, 178–190. doi: 10.1177/0022466916644425

Briesch, A. M., Hemphill, E. M., Volpe, R. J., and Daniels, B. (2014). An evaluation of observational methods for measuring response to classwide intervention. Sch. Psychol. Q. 30, 37–49. doi: 10.1037/spq0000065

Caldarella, P., Larsen, R. A. A., Williams, L., and Wills, H. P. (2023). Effects of middle school teachers’ praise-to-reprimand ratios on students’ classroom behavior. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 25, 28–40. doi: 10.1177/10983007211035185

Caldarella, P., Larsen, R. A. A., Williams, L., Wills, H. P., and Wehby, J. H. (2019). Teacher praise-to-reprimand ratios: behavioral response of students at risk for EBD compared with typically developing peers. Educ. Treat. Child. 42, 447–468. doi: 10.1353/etc.2019.0021

Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Borgogni, L., and Steca, P. (2003). Efficacy beliefs as determinants of teachers' job satisfaction. J. Educ. Psychol. 95, 821–832. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.95.4.821

Cashwell, T. H., Skinner, C. H., and Smith, E. S. (2001). Increasing second-grade students’ reports of peers’ prosocial behaviors via direct instruction, group reinforcement, and progress feedback: a replication and extension. Educ. Treat. Child. 24, 161–175. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42899652

Chaffee, R. K., Briesch, A. M., Johnson, A. H., and Volpe, R. J. (2017). A meta-analysis of class-wide interventions for support student behavior. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 46, 149–164. doi: 10.17105/SPR-2017-0015.V46-2

Chaffee, R. K., Briesch, A. M., Volpe, R. J., Johnson, A. H., and Dudley, L. (2020). Effects of a class-wide positive peer reporting intervention on middle school student behavior. Behav. Disord. 45, 224–237. doi: 10.1177/0198742919881112

Cihak, D. F., Kirk, E. R., and Boon, R. T. (2009). Effects of classwide positive peer "tootling" to reduce the disruptive classroom behaviors of elementary students with and without disabilities. J. Behav. Educ. 18, 267–278. doi: 10.1007/s10864-009-9091-8

Collins, T. A., Murphy, J. M., and Heidelburg, K. (2018). “Promoting supportive peer relationships using peer reporting interventions” in Promoting prosocial behaviors in children through games and play: Making social emotional learning fun. eds. R. Hawkins and L. Nabors (Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers), 63–83.

Criss, C. J., Konrad, M., Alber-Morgan, S. R., and Brock, M. E. (2022). A systematic review of goal setting and performance feedback to improve teacher practice. J. Behav. Educ. 33, 275–296. doi: 10.1007/s10864-022-09494-1

Donaldson, J. M., Matter, A. L., and Wiskow, K. M. (2018). Feasibility of and teacher preference for student-led implementation of the good behavior game in early elementary classrooms. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 51, 118–129. doi: 10.1002/jaba.432

Ennis, R. P., Royer, D. J., Lane, K. L., and Griffith, C. E. (2017). A systematic review of precorrection in PK-12 settings. Educ. Treat. Child. 40, 465–495. doi: 10.1353/etc.2017.0021

Fabiano, G. A., Vujnovic, R. K., Pelham, W. E., Waschbusch, D. A., Massetti, G. M., Pariseau, M. E., et al. (2010). Enhancing the effectiveness of special education programming for children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder using a daily report card. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 39, 219–239. doi: 10.1080/02796015.2010.12087775

Floress, M. T., Jenkins, L. N., Reinke, W. M., and McKown, L. (2018). General education teachers’ natural rates of praise: a preliminary investigation. Behav. Disord. 43, 411–422. doi: 10.1177/0198742917709472

Goldman, S. E., Sanderson, K. A., Lloyd, B. P., and Barton, E. E. (2019). Effects of school-home communication with parent-implemented reinforcement on off-task behavior for students with ASD. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 57, 95–111. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-57.2.95

Han, S. S., and Weiss, B. (2005). Sustainability of teacher implementation of school-based mental health programs. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 33, 665–679. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-7646-2

Harry, S. W., Tingstrom, D. H., Dufrene, B. A., Hart, E. H., Radley, K. C., Lum, J. D., et al. (2021). The effects of tootling combined with public posting in high school classrooms. J. Behav. Educ. 32, 565–584. doi: 10.1007/s10864-021-09462-1

Howell, A., Caldarella, P., Korth, B., and Young, K. R. (2014). Exploring the social validity of teacher praise notes in elementary school. J. Classr. Interact. 49, 22–32.

Kamps, D., Wills, H., Bannister, H., Heitzman-Powell, L., Kottwitz, E., Hansen, B., et al. (2015). Class-wide function-related interventions teams “CW-FIT” efficacy trial outcomes. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 17, 134–145. doi: 10.1177/1098300714565244

Lambert, A. M., Tingstrom, D. H., Sterling, H. E., Dufrene, B. A., and Lynne, S. (2015). Effects of tootling on classwide disruptive and appropriate behavior of upper-elementary students. Behav. Modif. 39, 413–430. doi: 10.1177/0145445514566506

Layer, S. A., Hanley, G. P., Heal, N. A., and Tiger, J. H. (2008). Determining individual preschoolers’ preferences in a group arrangement. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 41, 25–37. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-25

Ledford, J. R., and Gast, D. L. (2018). Single-case research methodology: Applications in special education and behavioral sciences. New York, NY: Routledge.

Lipscomb, A. H., Anderson, M., and Gadke, D. L. (2018). Comparing the effects of ClassDojo with and without tootling intervention in a postsecondary special education classroom setting. Psychol. Sch. 55, 1287–1301. doi: 10.1002/pits.22185

Lum, J. D. K., Radley, K. C., Tingstrom, D. H., Dufrene, B. A., Olmi, D. J., and Wright, S. J. (2019). Tootling with a randomized independent group contingency to improve high school classwide behavior. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 21, 93–105. doi: 10.1177/1098300718792663

Lum, J. D. K., Tingstrom, D. H., Dufrene, B. A., Radley, K. C., and Lynne, S. (2017). Effects of tootling on classwide disruptive and academically engaged behavior of general-education high school students. Psychol. Sch. 54, 370–384. doi: 10.1002/pits.22002

Maggin, D. M., Pustejovsky, J. E., and Johnson, A. H. (2017). A meta-analysis of school-based group contingency interventions for students with challenging behavior: an update. Remedial Spec. Educ. 38, 353–370. doi: 10.1177/0741932517716900

McHugh Dillion, M. B., Radley, K. C., Tingstrom, D. H., Dart, E. H., and Barry, C. T. (2019). The effects of tootling via classdojo on student behavior in elementary classrooms. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 48, 18–30. doi: 10.17105/SPR-2017-0090.V48-1

McHugh, M. B., Tingstrom, D. H., Radley, K. C., Barry, C. T., and Walker, K. M. (2016). Effects of tootling on classwide and individual disruptive and academically engaged behavior of lower-elementary students. Behav. Interv. 31, 332–354. doi: 10.1002/bin.1447

McLeskey, J., Barringer, M.-D., Billingsley, B., Brownell, M., Jackson, D., Kennedy, M., et al. (2017). High-leverage practices in special education. Arlington, VA: Council for Exceptional Children & CEEDAR Center.

Miltenberger, R. G. (2012). Behavior modification: Principles and procedures. 5th Edn. Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning.

Murray, E., McFarland-Piazza, L., and Harrison, L. J. (2015). Changing patterns of parent–teacher communication and parent involvement from preschool to school. Early Child Dev. Care 185, 1031–1052. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2014.975223

Oliver, R. M., Wehby, J. H., and Nelson, J. R. (2015). Helping teachers maintain classroom management practices using a self-monitoring checklist. Teach. Teach. Educ. 51, 113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2015.06.007

Owens, J. S., Holdaway, A. S., Smith, J., Evans, S. W., Himawan, L. K., Mixon, C. S., et al. (2018). Rates of common classroom behavior management strategies and their associations with challenging student behavior in elementary school. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 26, 156–169. doi: 10.1177/1063426617712501

Owens, J. S., Holdaway, A. S., Zoromski, A. K., Evans, S. W., Himawan, L. K., Girio-Herrera, E., et al. (2012). Incremental benefits of a daily report card intervention over time for youth with disruptive behavior. Behav. Ther. 43, 848–861. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2012.02.002

Peltier, W., Newell, K. L., Linton, E., Holmes, S. C., and Donaldson, J. M. (2022). Effects of and preference for student- and teacher-implemented good behavior game in early elementary classes. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 56, 216–230. doi: 10.1002/jaba.957

Sailor, W., Dunlap, G., Sugai, G., Horner, R. H., and Bradley, R. (2009). Handbook of positive behavior support. New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media, LLC.

Skinner, C. H., Cashwell, T. H., and Skinner, A. L. (2000). Increasing tootling: the effects of a peer-monitored group contingency program on students' reports of peers' prosocial behaviors. Psychol. Sch. 37, 263–270. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6807(200005)37:3<263::AID-PITS6>3.0.CO;2-C

Skinner, C. H., McClurg, V., Crewdson, M., Coleman, M. B., Bennett, J., Fowler, K., et al. (2022). Alternating treatments designs: Interpretation challenges and design solutions for validating and comparing interventions. Phsyc. Schools. 59, 678–697. doi: 10.1002/pits.22638

Skinner, C. H., Skinner, A. L., and Cashwell, T. H. (1998). “Tootling, not tattling.” in Paper presented at the 26th annual meeting of the mid south educational research association, New Orleans, LA.

Skinner, C. H., Wallace, M. A., and Neddenriep, C. E. (2002). Academic remediation: educational application of research on assignment preference and choice. Child Family Behav. Ther. 24, 51–65. doi: 10.1300/J019v24n01_04

Sugai, G., and Horner, R. (2002). The evolution of discipline practices: school-wide positive behavior supports. Child Family Behav. Ther. 24, 23–50. doi: 10.1300/J019v24n01_03

Sugai, G., and Horner, R. H. (2009). Response to intervention and school-wide positive behavior supports: integration of multi-tiered system approaches. Exceptionality 17, 223–237. doi: 10.1080/09362830903235375

Sugai, G., Simonsen, B., Bradshaw, C., Horner, R., and Lewis, T. (2014). “Delivering high quality school wide positive behavior support in inclusive schools” in Handbook of research and practice for inclusive schools. eds. J. McLeskey, N. L. Waldron, F. Spooner, and B. Algozzine (New York, NY: Routledge), 306–321.

Tanol, G., Johnson, L., McComas, J., and Cote, E. (2010). Responding to rule violations or rule following: a comparison of two versions of the good behavior game with kindergarten students. J. Sch. Psychol. 48, 337–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2010.06.001

Keywords: tootling, alternating treatments, peer praise, intervention, behavior

Citation: Thoele JM and Sayeski KL (2024) The effects of student- and teacher-led tootling on student disruptive behavior. Front. Educ. 9:1449306. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1449306

Edited by:

Robin Parks Ennis, University of Alabama, United StatesReviewed by:

Justin Lane, University of Kentucky, United StatesWendy Peia Oakes, Arizona State University, United States

Carrie Brandon, Arizona State University, United States, in collaboration with reviewer WO

Copyright © 2024 Thoele and Sayeski. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jillian M. Thoele, amlsbGlhbi10aG9lbGVAdWlvd2EuZWR1

†Present address: Jillian M. Thoele, Department of Teaching and Learning, College of Education, North Lindquist Center, The University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, United States

Jillian M. Thoele

Jillian M. Thoele Kristin L. Sayeski

Kristin L. Sayeski