- 1Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany

- 2Faculty of Humanities, Department of Educational and Social Sciences, Education and Rehabilitation of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany

- 3Rheinisch Westfälisches Berufskolleg (Vocational School for the Deaf), Essen, Germany

Introduction: Teaching English as a foreign language (EFL) to Deaf and hard-of-hearing (DHH) students is regarded as a major challenge.The aim of the study is to examine the perspectives of DHH students regarding their experiences in the EFL classroom.

Methods: Utilizing a qualitative design, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 17 former DHH students who learned English at German schools for the DHH.

Results: The findings reveal various language combinations within the EFL classroom, which entirely depend on the teacher. Several critical aspects of the EFL classes were highlighted, including the insufficient foreign sign language competences of teachers, the juxtaposition of German Sign Language (DGS) signs and spoken English, and the lack of Deaf cultural content and awareness in the teaching. Additionally, the absence of interactive engagement in the EFL classroom was noted as a significant issue. Based on the DHH students’ EFL learning experiences, both English and American Sign Language (ASL) served as foreign languages for young DHH individuals, particularly in the context of international communication and social media engagement.

Discussion: This study underscores the importance of integrating ASL into EFL classrooms to better support DHH students’ language learning needs. The findings highlight the critical role of teacher training in ASL and the necessity for standardized approaches to EFL instruction. By aligning teaching practices with students’ lived experiences and incorporating sign language, educators can foster more inclusive, effective learning environments that not only enhance academic success but also affirm students’ identities and rights.

1 Introduction

This research is based on the understanding of Deaf and hard-of-hearing (DHH) people being bimodal-multilingual learners. Bimodal multilingualism refers to the learning and use of languages in two different modalities: spoken languages, which are conveyed acoustically or in writing, and sign languages, which are expressed manually and perceived visually. While the acquisition of a spoken language is only partially possible for DHH individuals, even with technical support, sign languages are fully accessible to DHH students when offered. Signed and spoken languages show very little articulatory or perceptual overlap, and signed languages have no standardized, widely-used written systems (Becker and Jaeger, 2019). Despite empirical evidence demonstrating the benefits of sign language proficiency for processing written forms of languages (Villwock et al., 2021), the inclusion of sign language in teaching is not standard practice.

Acquiring English on an intermediate to professional level is a requirement of inclusion, as English competence opens doors to international academic and professional opportunities and enriches leisure activities. The aim of English as a foreign language (EFL) teaching is the preparation for authentic (real-world) language interactions (Berlin Senate Department for Education, Youth, and Science, 2015). In Germany, students mandatorily begin learning English in primary school across all federal states. The same applies to DHH students following the mainstream curriculum: DHH students must acquire a certain (high) level of English proficiency in order to pass nationwide standardized exams, gain entrance to tertiary education and to become - just as their hearing peers - global citizens who are able to navigate international settings of any kind (Bartz and Eitzen, 2016). Despite the importance of the subject, teaching EFL to DHH students has been broadly discussed as a major challenge for teachers (see Urbann, 2020, for an overview). For example, a specific training on how to teach English to DHH students is nonexistent. In the current teacher training programs in Germany, DHH education and the subject of English are studied separately, resulting in a lack of overlap and integrated content. Inadequate teacher education leads to frustration and a wide, inconsistent spectrum of EFL classroom practices. To gain insights into these practices through the perspective of DHH students in Germany, this qualitative interview study was conducted. The following section outlines the potential languages and language systems that may be used in EFL classrooms with DHH students. Additionally, it provides an overview on the current state of research, summarizing existing findings in the field and highlighting the relevance of this study.

2 Background

Sign languages, such as DGS, are fully fledged languages with a distinctive grammar and syntax that differ from languages in spoken and written forms. Sign languages use spatial grammar and rely on visual–spatial modality, incorporating movements of the hands, facial expressions, and body language to convey meaning [see Pfau et al. (2012) for DGS]. Specifically, sign languages used in countries with English as an official language (or a national language and lingua franca) are not identical but differ fundamentally in linguistic terms. Broadly speaking, these sign languages include American Sign Language (ASL) and the British-Australian-New Zealand Sign Language (BANZSL; Schembri et al., 2010). BANZSL is further subdivided into British Sign Language (BSL), Australian Sign Language, and New Zealand Sign Language according to the respective countries. ASL is primarily used in the United States and Canada, but also in other countries where individuals with ASL proficiency have influenced the educational landscape, such as in Guatemala or Ghana (Nyst, 2007; Parks and Parks, 2008). Also ASL has been influencing International Sign, which is not a natural language but “a set of conventions […] that some authors have said are pidgin-like “(World Federation of the Deaf and World Association of Sign Language Interpreters, 2019, 1). Looking at general teaching practices with DHH students again, sign language mixed with spoken language is also used. On the one hand there exist artificially created combined forms such as Signed Exact English (SEE) or Signed English (SE) that follow prescribed rules. Unlike ASL, these artificially created combined forms follow the English word order and grammar rules. SEE and SE are systems of manual communication by visually representing the English language. These manual communication systems are primarily used in educational settings to support the development of English literacy competencies of DHH students. On the other hand, there is contact signing [also known as Pidgin Sign(ed) English], which combines spoken English with ASL in a free and ‘natural’ form. In addition to using ASL signs, facial expressions are employed to mark different sentence types and emotions, and the signing space is utilized (Baker-Shenk and Cokely, 1996; Reilly and McIntire, 1980; Woodward, 1973). The German equivalent to contact signing is Sign Supported German. Within this system, German signs are used in conjunction with spoken German to provide additional visual information, thereby supporting or clarifying the spoken message. Both Sign Supported German and contact signing do not possess their own grammars but instead follow the grammars of the spoken or written forms of their respective languages (Steinbach et al., 2007). German Signs with English Mouthing appears as a special form that occurs in English as a foreign language teaching in Germany, where spoken English is accompanied by signs from German Sign Language. This mode of communication is not a natural language but rather a type of auxiliary system.

Since the 2000s, (inter-)national empirical work and practice reports on the discourse of “teaching English to DHH students” have been presented, resulting in a broad spectrum of discussion. The methodological approaches vary greatly, which affects the validity of the publications (Kang and Scott, 2021). In certain publications, the authors describe the teaching of English with a specific group of learners, or the authors explain their own teaching approach. More generally, Ay and Şen Bartan (2022, Turkey), Stoppock (2014, Germany) and Ramos Martin-Pozo (2022, Spain), describe didactic-methodological considerations for teaching English and adaptations of curricula for DHH students, especially focussing on the English in its written form, visualizations, and using technological tools. In the German context, the focus lies on the introduction of another sign language, namely ASL, into the EFL classroom. Bartz and Eitzen (2016) discuss the opportunities and limitations of ASL as contact signs in English classes in upper secondary level at a vocational school for the DHH in Germany. Kremp (2015) reports on her enriching ASL use in English classes. Poppendieker (2011) published a paper in which she traced her didactic choices regarding English instruction at the Elbschule in Hamburg, Germany, and discussed the use of SEE in her teaching (Poppendieker, 2011, 25). Bartz and Eitzen (2016), Kremp (2015), and Poppendieker (2011) agree that from a teacher’s perspective, the use of ASL has a positive impact on students’ motivation to learn English. As a result of their experiences, the four teachers also describe their impression that the memorization of English words is increased through the use of ASL signs and that the students can learn new ASL signs quickly and with appropriate methods (for example with the help of dictionaries). According to Poppendieker (2011), the acquisition of ASL signs leads to increased communication in the classroom, making the English class become interactive.

Other research describes how English language instruction is implemented in a school setting, such as an anonymous school in Kazakhstan (Sultanbekova, 2019) or the Dharma Bhakti Dharma Pertiwi Special School in Indonesia (see Puri et al., 2019). Complementary, Ristiani (2018) describes general challenges of teaching English to DHH students in Indonesia without using the term “sign language” once. Both examples focus on a phonetic and written language approach. As an educator, the question is how to consciously choose an approach keeping in mind the diverse learner group and their individual needs and competencies. The current state of English language teaching with DHH students related to a particular for France country—was surveyed in studies by Bedoin (2011). Kontra et al. (2015a) for Hungary, by Domagała-Zyśk (2011, 2019) for Poland, by Machová (2019) for Czech Republic, by Nisha and Gill (2020) for India, by Quay (2005) for Japan, by Pritchard (2004); Poppendieker (2011) for Norway, and by Uradarević (2016) for Serbia. Bedoin’s (2011) research is based on a questionnaire survey in 104 schools, comprising 12 semi-structured interviews with teachers, and 68 classroom observations. She concludes that there is a great diversity in teaching English to DHH students in France. In addition, she describes the challenges for teachers to teach English adequately, due to the lack of professional qualifications for teaching English to DHH students or in view of the great heterogeneity of the learning groups, among other factors. In order to improve the quality of English teaching, Bedoin (2011) calls for improved training of teachers who teach foreign languages to DHH students. All teachers who participated in her study were hearing; perspectives of students on their English instruction were not collected. Following the clear formulation in the introduction of Bedoin’s article, where the author states “(t)he purpose is not to teach them a foreign sign language, such as British sign language (BSL) or American sign language (ASL), but standard written and/or spoken English” (Bedoin, 2011, 160), the use of sign language is not discussed any further. In contrast, Kontra et al.'s (2015a) survey explicitly addresses the central role of sign language for DHH students. As one of the few studies in the field that actually gathered data and evaluated responses from different perspectives, the Hungarian research team conducted a questionnaire survey (N = 105 students), interviews (N = 10 teachers and N = 7 principals), and also classroom observations. Three of the ten teachers interviewed had completed professional training in both English and teaching DHH students, four in one of the two subject areas (either English or Deaf education), and three in neither. Since auditory-verbal instruction was predominant in Hungary at the time of the survey, there was little or no use of sign language in English classes. The teachers interviewed wished to have more competencies in Hungarian sign language in order to have more lively exchanges with their students, as well as appropriate materials and methods for teaching English to DHH students to better motivate students to learn English [also see Uradarević (2016)]. Although students should have reached level A2 (“elementary”) of the “Common European Framework of Reference for Languages” in reading and writing by grade 8, teachers consider level A1 (“beginner”) to be more realistic.

European and international research more and more calls for the explicit integration of national sign languages in English classes. Along with Kontra et al.'s (2015b) call for Hungarian Sign Language, Machová (2019) makes a case for Czech Sign Language, as do Nisha and Gill (2020) for Indian Sign Language, and Quay (2005) for Japanese Sign Language (or ASL). A position contrary to these demands is taken by the Polish researcher (Domagała-Zyśk 2019). The use of Polish Sign Language should be reduced in English classes, she argues. In her numerous writings, Domagała-Zyśk does not comment on the possible inclusion of a sign language from an English-speaking country. Among other methodological impulses for teaching English to DHH students, she has developed a modification of the National School Curriculum for English as a subject for DHH students (e. g. by dropping “pronunciation” as a learning objective or adding “getting to know famous DHH people from other countries”). Although English literacy is generally important from an educational perspective, DHH students do not participate in English classes everywhere. For example, in mainstream classes in Hungary, DHH students are excluded from foreign language classes (Kontra et al., 2015a). In Serbia, special regulations apply, according to which DHH students either do not participate in English classes at all or are taught according to an adapted curriculum (Uradarević, 2016). Also in Serbia, the focus of English lessons is on written language competence, although according to the author, speech and language exercises are also carried out with the support of a speech therapist, among others, and contrastive work is done with English and Serbian. Berent (2001) also takes up the aspect of the comparison of two written languages and discusses the specific challenges with regard to the acquisition of English grammar by comparing Czech and English. That students students can successfully learn BSL was demonstrated by Pritchard (2011) in a small study [N = 29 students (experimental group: N = 15 DHH students and without additional disabilities who learned BSL; control group: N = 8 Swedish bimodal-bilingual taught DHH students without BSL skills and N = 6 hearing Norwegian students without sign language skills)].

Pritchard (2004) describes the situation of English teaching in Norway differently. In the early 2000s, BSL was introduced in grade 1, and English was not focused on any further than grade 4. In English classes, recordings of BSL-native signers were used as language models. In addition, numerous teachers in Norway were already trained in BSL through corresponding EU programs. In her positive remarks about teaching English with BSL, Pritchard emphasizes the professional quality of the teachers as a central factor for success. They should be competent in both English and BSL in order to be able to function not necessarily as linguistic role models, but primarily as competent learning facilitators. Teachers report that students are highly motivated to learn BSL, regardless of their degree of hearing loss or their preferred mode of communication. The previously mentioned Hungarian group of researchers looked at more in-depth aspects of English language teaching in the Hungarian context. As one of the research group members, Kontra (2013) retrospectively interviewed 23 DHH adults about their experiences in foreign language classes. The statements highlighted the barriers that DHH people face in language learning: An educational landscape that does not sufficiently address the needs of DHH people; a lack of appropriate teaching materials; a lack of well-trained teachers; a lack of sign language use and sign language competencies on the part of the teachers. The respondents were positive about the use of sign language (e. g. ASL) in the foreign language classroom, because it strengthens the motivation to learn the foreign language. The barriers described by Kontra (2013) were confirmed in another study by Kontra et al. (2015b). In this study, 31 DHH students were interviewed about their experiences in foreign language classrooms. The students reported needing extra help in foreign language learning and having to exert more effort, which led to low motivation to learn. In addition, many students felt that their own competence in Hungarian was not sufficient to learn another spoken language. At the same time, they considered the use of Hungarian sign language in foreign language classes as indispensable and highly motivating, which is also confirmed by Kontra and Csizér 2013; (N = 331) in an extended way for a foreign sign language and in principle by Csizér et al. (2015). This study, which surveyed 96 DHH students from eight different schools, found that DHH students tend not to consider themselves as language learners and do not develop a positive vision here. This lack of an ideal vision of a ‘desired L2 self’ complicates the foreign language learning process.

Despite the critical descriptions of the current state of English language teaching, from which impulses for the design of English language teaching have been derived, there are hardly any empirical studies to date which examine the effectiveness of English language teaching, for example with regard to the learning level of the students (Kang and Scott, 2021). Pritchard (2004), for example, surveys students’ BSL competences and provides arguments for its use, but concrete statements on students’ English competences are missing. In addition, it is noticeable that most publications are written by hearing experts without openly reflecting this perspective. Publications that include the perspective of DHH people call for the use of a sign language from an English speaking country in EFL classes because it is assumed that it can increase students’ motivation to learn English and enable spontaneous international communication (for example Poppendieker, 2011; Kontra and Csizér, 2013; Csizér et al., 2015; Csizér and Kontra, 2020). Fister (2017) states in her research that there is indeed no difference between hearing and DHH students of English in their motivational approach to learning English as a global language. However, the aspect of international communities that use International Sign or written English might be a contributing factor for DHH students that need further assessment in the future. For the sake of completeness, it should be briefly mentioned that some teaching methods were also evaluated. However, without much value for the EFL teaching itself, as they confirm the usage of established methods to teach DHH students in general: Their evaluation of teaching methods in the EFL classroom with DHH students indicates that visual support enhances vocabulary teaching effectiveness (Birinci and Sarıçoban, 2021), while subtitles and videos also prove to be effective (Baranowska, 2022).

In summary, the existing research findings include only a very limited number of research projects in the field of bimodal-multilingual EFL teaching. Also, there is a lack of comprehensive, country-specific research on EFL teaching practices to DHH students. While research by Kontra et al. (2015a) in Hungary and Bedoin (2011) in France offers valuable insights, a more comprehensive understanding of the diverse needs of DHH students in various educational settings, such as Germany, is essential. This study aims to examine the perspectives of DHH bimodal-multilingual students in German EFL classrooms.

3 Our study

To explore the perspectives of DHH students on their experiences in the EFL classroom at schools for the DHH in Germany, three research questions were investigated:

1. How do DHH students perceive the communication in the EFL classroom?

2. What do students perceive as challenges in the EFL classroom?

3. How do DHH students relate to English and sign languages from English-speaking countries?

3.1 Methods

To answer the research questions, semi-structured interviews were conducted and analyzed using qualitative content analysis according to Kuckartz and Rädiker (2022). The selection criteria and composition of the sample as well as the process of data collection and data analysis are described in the following.

3.2 Sample

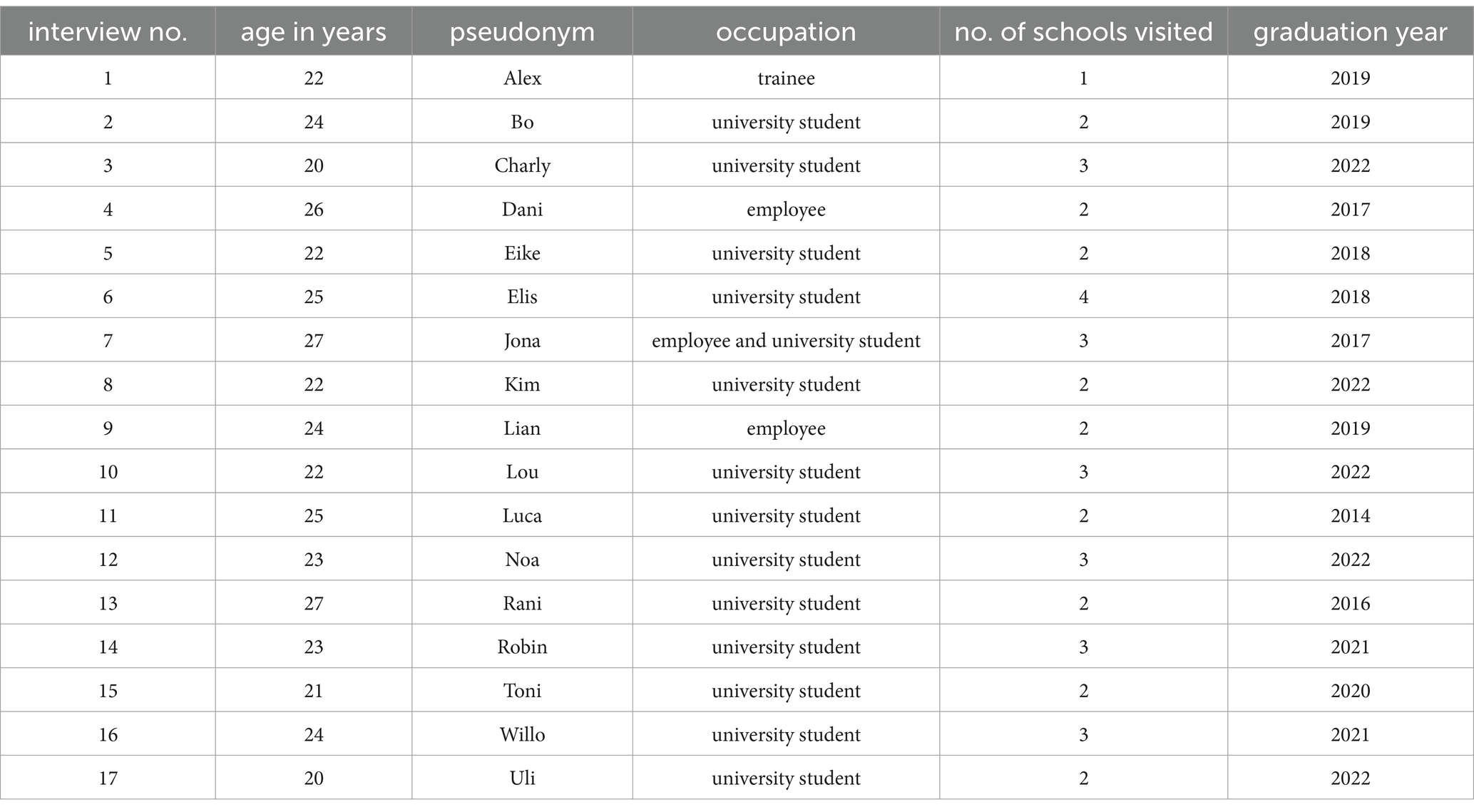

The study’s sample selection criteria were carefully defined to ensure relevance and representativeness. Participants were required to meet the following four criteria: (1) Their everyday mode of communication is DGS, (2) they are at least 18 years old, (3) they left a school for the DHH in Germany not earlier than in 2014, (4) they attended schools for the DHH in Germany for at least ten years. The sample was recruited via Deaf community gatekeepers, e. g. associations of DHH young people. 17 young adults, who met the inclusion criteria and gave their informed consent to the study were included. They were between 20 and 27 years old and came from different federal states in Germany. Altogether, they went to 18 different schools for the DHH in Germany, which corresponds to almost a third of the schools for the DHH in Germany. All but two of the participants were university students. The following table shows the composition of the interview study sample in alphabetical order of the pseudonyms (Table 1).

3.3 Data collection

In the process of data collection, semi-structured interviews were chosen (Supplementary material). Due to pragmatic reasons (the interviewees came from different places in Germany) the interviews were conducted and recorded via the software Zoom. The interviews took place in DGS and were led by one of the authors, a native German signer with expertise in empirical interviewing. This person attended schools for the DHH in Germany herself, where she also learned English, following “DEAF-SAME” (Kusters and Friedner, 2015, x). DEAF SAME “emphasizes at the feeling of deaf similitude and […] is grounded in experiential ways of being in the world as deaf people with (what are assumed) to be shared […] experiences” (Kusters and Friedner, 2015). The basis of the interviews was an interview guideline that had been tested in a preliminary pilot study. This interview guideline can be viewed in the Supplementary material of this article. After a greeting, informed consent and the collection of some contextual data about the interviewee, the interview developed along the following three blocks of questions, among others: communication in the EFL classroom, criticism of the EFL classroom practices, the meaning of English and a sign language from an English speaking country to the former students. These blocks were assigned to the three research questions. All DGS interviews were translated into German by a professional sign language interpreter. The German translations were subsequently transcribed and cross-verified with the signed originals by two researchers of the team, both fluent in DGS and German, one of whom was the interviewer herself, to ensure accuracy and prevent translation errors.

3.4 Data analysis

The analysis of the collected contextual data about the interviewees were conducted in tabular form. Before the qualitative analysis of the material, pseudonyms were assigned, and the names of schools, places, and teachers were removed from the transcripts to protect the sensitive data of the participants and shift the focus from the individuals providing the data to the content of the data itself. After that all interviews were summarized in preparation for the content analysis.The qualitative content analysis of the interview transcripts was carried out using MAXQDA 2022 (VERBI Software, 2021). In accordance with the analysis approach of Kuckartz and Rädiker (2022), the category system was initially derived from the research questions and further refined through an inductive analysis of the data material. For each category, a definition and coding rules were recorded in a coding guide, which ensured the uniform assignment of text passages to the categories within the research team. The original text excerpts were first reproduced in their own words (paraphrase). The wealth of statements per category was abstracted by summarizing them into superordinate statements or partial findings (generalization), from which the main findings were then derived. The development of the category system was based on 4 of the 17 interviews, which corresponds to 23.5% of the data material. The other data sets were then coded, whereby the category system was constantly checked and further subcategories were added. The number of subcategories vary according to the complexity of the main category. For example, the main category ‘criticism of English lessons’ has 16 subcategories, whereas the main category ‘importance of languages’ has only 3 subcategories. A tabular overview of the main 4 categories and subcategories can be found in the Supplementary material. Consensual coding was employed throughout the whole process, involving four individuals who worked in alternating tandems to ensure reliability and validity in the coding process. All four researchers are fluent in both German Sign Language and German. In cases of divergent coding within a tandem, the original material was reviewed, and a consensus was reached among all four researchers.

3.5 Results

The results’ presentation is structured according to the three research questions. Firstly, how DHH students perceive the communication in the EFL classroom.

3.5.1 Various language combinations appear, exclusively depending on the teacher

Overall, the participants described nine different language combinations that are used in the EFL classroom. Besides written English, different sign languages were used: British Sign Language, American Sign Language and German Sign Language. Eike’s description of the continuous change between languages which depended mainly on the teacher was exemplary: “But there we alternated between BSL and ASL, depending on the teacher (…). The written language also alternated between British English and American English.” Also, the interview partners reported that German and English were spoken in the EFL classroom. Besides these two language modalities, mixed forms were also part of the teaching: Signed Exact English, Sign Supported German and German Sign Language with English mouthing. This leads to very diverse EFL teaching practices in which the use of languages depends exclusively on the teacher. The most common form of communication was a combination of German signs with English mouthing. The former students described this combination as highly confusing, for example Dani: “[…] to have German or the German gesture with English mouthing I did not get anything together at all. I did not understand anything.” What the former students recalled as positive and beneficial throughout was the use of ASL. For example, Bo described the ASL experience as follows: “[…] and then Ms. X came to our class. And she signed ASL. And we sat there and could not believe it. And I just thought to myself: Yes, that’s it.” Despite the language and modality employed by the teacher, the former students naturally gravitated toward using the sign language that felt most intuitive and accessible to them for communication amongst themselves, as elucidated by Rani: “But among ourselves, I think we handled it in DGS and I think if it [classroom language] had been ASL, we probably could have used ASL as well. But we did not adopt this language mix-up among ourselves.”

Secondly, the question what DHH students perceive as challenges in the EFL classroom was addressed.

3.5.2 Insufficient ASL/BSL competences of teachers

In addition to broader criticisms like monotony in the EFL classroom and the pressure to excel, the interviewees mainly criticized the missing or inadequate ASL/BSL competences of their teachers. Elis formulated to the point: “And then, of course, it also requires teachers who can understand everything and that is the difficulty. So, I had teachers who of course did not fully understand me. Therefore, I did not sign fully in ASL, I had to adapt my language level to the teachers’ skills, the language I used had to be limited and these limited language skills were then assessed. In my opinion, that’s absolutely not okay. That’s transgressive in my opinion.”

3.5.3 Juxtaposition of DGS signs and spoken English

Moreover, the former DHH students consistently mentioned concerns about the haphazard and bewildering language mixture employed by teachers, particularly the juxtaposition of DGS signs and spoken English. This confusing language mix hindered comprehension and learning, resulting in demotivation and limited access to foreign language resources. Consequently, students, such as Willo, struggled to acquire language skills effectively. “[…] I simply could not understand everything, that English was spoken and German was signed and I could not get it all together afterwards. And I just sat frustrated at school and had to learn somehow.”

3.5.4 Teachers’ lack of ASL grammar competences

Following this point, the former students also critically highlighted the teachers’ lack of ASL grammar competences, as Lou mentioned in an exemplary way: “Well, the teachers just used this Sign Supported German. That’s why many of them simply did not know about the grammar in ASL.” Although the students criticized the teachers for their perceived lack of competences, they also expressed gratitude for the effort made to learn ASL and incorporate it into their teaching: “And then a new teacher came to our school as a trainee teacher and took over our class and she familiarized herself with ASL and also used ASL quite a lot. She had been learning it somehow for three and a half years and had worked her way into it. It wasn’t full-fledged, but at least it was more than before.” Building upon this criticism the interviewees demanded DHH students to be taught in full-fledged ASL in the EFL classroom.

3.5.5 Lack of Deaf cultural content and awareness

In addition to the absence of foreign sign language skills, the lack of Deaf cultural content in the lessons and the teachers’ insufficient Deaf cultural awareness were also critically noted: “And that you do not just take language and not just hearing culture. I’ve always had the impression that only hearing people were given a closer look at English-speaking culture and I think as a Deaf person you identify more with Deaf persons and Deaf culture. And that was completely missing.”

3.5.6 Substituting spoken English

In general, the use of spoken language within the EFL classroom was perceived as meaningless by the former DHH students. Most interviewees only considered the use of spoken English of some importance when it came to the issue of spoken language exams and how their school and English teacher(s) dealt with this particular challenge. Some interview partners reported they were sometimes only offered oral exams or listening comprehension exercises. Besides oral exams and listening comprehension exercises, some students, especially the ones with general qualification for university entrance, had chat exams instead of oral exams in their last years of school and highly criticized this exam form as well, e. g. Bo: “At X school we had chat exams. These exams were incredibly criticized. Because the person sitting opposite us, which means the person we chatted with, was drawn by lot. […] So we were given these tasks. We always dealt with the topics a bit beforehand. We were then allowed to write a text. So it was just a chat. Then at some point the time was up. Then we sent it to one person. And I did not know who it was. This person was sitting in another room and was sent my text. And then I was supposed to take on a role based on a task. Be it the boss, be it the salesperson. Be it person XY. So I looked at the text. And my counterpart was also given a role. And we were supposed to enter into a dialog, but in chat form. […] And that’s what the exam looked like. The bad thing about it was that, on the one hand, the program, so let us say I typed something and I realized: Oh, no, it’s wrong at the beginning. Then I had to delete everything I had typed so far to correct it. […] Maybe you were somehow unlucky with your partner, who either did not feel like it or could not do it. […] And that always meant that there was no other solution. But actually, there probably needs to be a new solution somehow. But then every student would have to have the privilege of learning ASL.”

3.5.7 Missing interaction

Besides the former students’ descriptions of chat exams, the missing meaningfulness and frustration was evident within other instances regarding their EFL classroom experiences, such as missing interaction, as Bo mentioned: “It was only ever written on the blackboard or on the worksheet. And if it was wrong, it was explained to us. So there was never any interaction question, answer, question, answer. None at all. Zero. Always just tasks that we had to complete. Then it was explained why that was the case. Why this tense is used. Why -ed or -ing is used now and so on. This was explained to us in DGS. There was no interaction.”

The challenges perceived by DHH students regarding their English classes highlight several key issues. Firstly, there is dissatisfaction with the insufficient ASL/BSL competencies of teachers, leading to limited linguistic expression and frustration among students. Additionally, concerns arise from the haphazard mixing of DGS signs with spoken English, making comprehension challenging for students. Moreover, the lack of ASL grammar competences among teachers impedes effective instruction, although efforts to incorporate ASL are acknowledged. Furthermore, the absence of Deaf cultural content in lessons and the inadequate awareness of Deaf culture by teachers are noted, leaving students feeling excluded. The use of spoken language within the EFL classroom is deemed meaningless by former DHH students, who criticize chat exams and the lack of meaningful interaction in lessons. These findings underscore the need for improved teacher training and curriculum development to better support the linguistic and cultural needs of DHH students in English language education. Thirdly, the question was addressed how DHH students relate to English and sign languages from English-speaking countries.

3.5.8 Crucial importance of English and ASL as foreign languages

Generally speaking, both the acquisition of English and specifically ASL as a foreign sign language were highly important to DHH students. English and ASL served as gateways to the world, facilitating access to communication, education, and society for DHH students. Bo clarified: “[…] to communicate with people today without any problems in English […] that is so pleasant. It’s so valuable to have this broad access. I had some access to the English language before. But to have a much broader one now [with ASL] and to be able to communicate is really nice.” Representatively for most of the interviewed former students, Charly described English as “[…] beautiful. So my perspective on the English language is simple, it’s a world language. It’s omnipresent in my everyday life. As I said, on my phone, on my laptop and even now in my studies, I would say half of it is in English and so it’s just second nature. So I say that I can only express certain things in English and certain things only in German.”

3.5.9 Rare use of English in daily lives and predominantly use on social media platforms

Despite the significant importance of ASL and English, it appears that not all interviewees utilize it regularly in their daily lives. Nine participants mentioned that they either never or rarely use English in their everyday activities. Rani explained: “Sure, when I’m on vacation I have to be able to read English, I have to be able to write English, but otherwise I do not really use it at all. What did I learn it for? No, I mean, of course it’s a world language and when I see my parents who cannot speak it at all, it’s not wrong. But at the moment, in everyday life, I do not use it at all.” One context in which many interviewees predominantly used written English was on social media platforms or when communicating with international friends, as Luca reasoned: “Because I have friends all over the world where I have to chat in English.” The interviewees not only actively engage in using English on social media platforms but also passively encounter it when reading posts. Jona stated: “I follow quite a few accounts that post in English on Instagram.” Some interview partners also highlighted the advantages of written English for studying at university, reading books, at work, watching movies, and traveling.

3.5.10 International contacts through international sign and ASL

International Sign and ASL was mentioned particularly for social contacts and friendships, but also for participation in cultural events and social media engagements to stay up to date. As Luca stated: “And at the moment, when media is distributed around the world, it is also distributed in ASL or International Sign. And that’s why you actually see it every day.”

The acquisition of English and ASL was deemed highly important by DHH students, serving as vital tools for communication, education, and societal integration. As Uli succinctly stated: “Language means freedom to me.” Participants emphasized the value of English as a global language, facilitating broad access to information and communication channels. However, it was noted that not all interviewees regularly utilize English in their daily lives, with many primarily encountering it on social media platforms or when communicating with international friends. Conversely, International Sign and ASL were highlighted as crucial for social contacts, friendships, and participation in cultural events, reflecting their significance in fostering international connections and staying engaged with global media.

3.6 Discussion

In this section, the findings are contextualized within the existing body of research and limitations of the present study are revealed. Most of the studies available to date are general descriptions of English language teaching in a country or in a school. Thus, only few studies have collected data to which reference can be made here. Only in the studies conducted by Kontra (2013) and Kontra et al. (2015b), the perspective of DHH EFL learners were analyzed. In all three studies the insufficient training of teachers was criticized and the use of a foreign sign language in the classroom was positively mentioned. In contrast to findings of the study by Csizér et al. (2015), the former DHH students in this study strongly identified as language learners and highlighted the importance of learning English and ASL as foreign languages in school. They regard these languages as gateways to the world, providing access to communication, education, and society, aligning with the aim of EFL teaching posed by the Berlin Senate Department for Education, Youth, and Science (2015). However, according to the interviewees in this study, who described a lack of interaction in their EFL learning experiences, this objective is not being met.

Other aspects that were emphasized in previous studies are missing concepts and great diversity in teaching English to DHH students as described by Bedoin (2011). Bedoin’s findings are congruent with the experiences of the participants in this study, who describe a total of nine different language combinations whose use depends exclusively on the respective teacher and their respective language skills. The call by Kontra et al. (2015b), Machová (2019), Nisha and Gill (2020) and Quay (2005) for the explicit integration of the national sign language in EFL teaching does not coincide with the experiences of the former students in this study. They tend to cite the integration of national sign language, in this case DGS, as a point of criticism, particularly in combination with spoken English. In alignment with Pritchard (2004); Bedoin (2011), who highlights the professional quality of teachers as a crucial factor for success in foreign language teaching, this study also identifies the insufficient language skills of teachers in ASL as a major point of criticism.

Given that BANZSL and ASL are two distinct language systems, the question which sign language should be integrated into English instruction in (German) schools for the DHH is far more complex than the debate over the preference for British or American English in the EFL classroom with hearing students. Within the discussion about which sign language should be used, one stated advantage of using BSL in the EFL classroom with DHH students is the geographical proximity of Germany and the United Kingdom, which could theoretically make it easy to establish language contact in face-to-face encounters. The geographical proximity compared to the United States also theoretically enables foreign teachers to be trained in BSL, e. g. with a diploma from the Council for Advancement of Communication with deaf people (Pritchard, 2004, 2011). In addition, there is a greater linguistic contrast between BSL and DGS, which can be used didactically (Poppendieker, 2011), for example, the finger alphabet in BSL is two-handed, in ASL as in DGS it is one-handed. The similarity of the finger alphabets of DGS and ASL can also be seen as an advantage and argument in favor of ASL. Furthermore, ASL dominates social media and is therefore attractive to DHH students. Like Bartz and Eitzen (2016), Kremp (2015), and Poppendieker (2011), who highlight the positive impact of ASL on DHH students’ motivation in EFL classrooms from a teacher’s perspective, the results of this study further support this assertion from the perspective of the DHH students themselves. ASL also shows a high proximity to International Sign, which is regarded as an argument for its use in the EFL classroom with DHH students (Landesfachkonferenz Englisch HK NRW, 2019). Thus, teaching practice in Germany has effectively surpassed the academic discourse, resulting in only a few schools where BSL is officially used in the EFL classroom with DHH students.

3.7 Limitations

The study has two main limitations. Firstly, the interview data were translated from DGS into German and then after analysis selectively translated into English for this article to incorporate quotations. Although the translations were conducted by professional translators and subsequently reviewed by the research team, it cannot be ruled out that linguistic nuances from the DGS may have been lost in this two-step translation process. These nuances may be attributed to the different linguistic modalities of signed and written languages. Secondly, the predominantly academic background of the participants limits the diversity of experiences represented in the study. Future research should strive to include a more diverse range of educational backgrounds, including vocational and non-traditional learning environments, to capture a broader spectrum of language learning experiences (see ‘implications for further research’).

3.8 Implications

The results of the study have implications for both EFL classrooms with DHH students and future research.

3.8.1 Implications for the EFL classroom with DHH students

In the EFL classroom, the integration of ASL is paramount for fostering effective communication and language acquisition among DHH students. However, to achieve this goal, future teacher training programs must undergo significant adaptation. Teacher education programs need to incorporate ASL practices and specific didactics to equip educators with the necessary skills and knowledge to effectively teach EFL using sign language. Furthermore, it is essential for all schools for the DHH to adopt a standardized EFL concept that includes ASL. This standardized approach will ensure consistency and coherence in language instruction across different educational settings, ultimately benefiting students by providing them with a cohesive learning experience. Moreover, it is crucial to tailor EFL instruction to the lived realities of DHH students by actively listening to and incorporating their desires and needs, for example the need for a more inclusive approach in EFL classrooms that recognizes and integrates Deaf culture alongside the hearing English culture traditionally emphasized. By taking into account students’ preferences and feedback, educators can create a more inclusive and engaging learning environment that empowers students to succeed academically and develop proficiency in English and ASL.

In summary, the integration of ASL in EFL classrooms, coupled with comprehensive teacher training and the adoption of standardized EFL concepts, is essential for meeting the linguistic and educational needs of DHH students. By aligning teaching practices with students’ lived experiences and aspirations, educators can foster a supportive and empowering learning environment that facilitates language acquisition and promotes academic success. Ultimately, this would lead to a transformation of the EFL classroom into an “ASLFL” classroom. In addition to offering insights for EFL classrooms with DHH students, this study also suggests directions for future research.

3.8.2 Implications for future research

Future research should address several key areas to enhance understanding of EFL learning among DHH individuals. Firstly, including DHH students who communicate preferably in spoken language is essential, as their experiences and perspectives may differ significantly from those DHH students who prefer to communicate in sign language. This inclusion would provide a more comprehensive view of language learning challenges within the broader DHH community. Second, incorporating Deaf+ students, who may have additional disabilities or challenges beyond deafness, is crucial. Their exclusion overlooks important insights into the intersectionality of language learning and disability. Including Deaf+ students would provide valuable perspectives on the unique barriers they face in acquiring foreign languages. Third, the current focus on students with DGS as their main language limits the generalizability of the findings. Future research should include a more diverse range of language backgrounds to explore potential variations in language learning experiences and strategies among DHH students from different linguistic backgrounds, including family education and early childhood education. Fourth, a longitudinal study is required to evaluate the outcomes of systematically incorporating ASL into English instruction. Additionally, while student perspectives are valuable, understanding practices in EFL classrooms also requires input from teachers. Interviewing educators and observing their instructional methods would provide a more holistic view of the challenges and opportunities in teaching EFL to DHH students. Future studies should also focus on measuring the objective benefits of the additional use of ASL in the EFL classroom, for example by taking into account their academic achievements in EFL classes and/or co-activation of ASL and English of DHH young language learners. Addressing these areas in future research will contribute to a more nuanced understanding of language learning among DHH individuals and inform the development of more inclusive and effective educational practices.

4 Conclusion

Since DHH students learn EFL in many countries around the world, the issue of EFL teaching to DHH has become a topic of international discussion. Across various educational systems – within schools, across regions, and between nations – there exists significant diversity in how English is taught as a foreign language. This variation in teaching was also reflected in the present study. The findings of this study revealed the diverse language combinations used in EFL classrooms, which are largely dependent on individual teachers’ approaches. While a blend of German signs with English mouthing emerged as the most prevalent yet bewildering mode of communication, ASL stood out as the most advantageous form. Further key issues identified include the limited proficiency of teachers in foreign sign languages, specifically ASL, and the absence of Deaf cultural content and awareness in instruction. The lack of interactive and engaging teaching methods was highlighted as a significant barrier to effective learning. In light of their described challenges, the participants elaborated a clear vision of what they perceive as perfect EFL teaching: ASL should be included to enhance the students’ foreign language output and interaction within the classroom. Moreover, participants emphasized the importance of creating a supportive learning environment that celebrates Deaf culture and values the unique experiences and perspectives of DHH students in order to utilize intrinsic learner motivation.

Drawing from the experiences of DHH students, this study emphasizes the critical importance of professional training for teachers in ASL, which would lead to the emergence of ASLFL classes. ASLFL classes would replace the current well-intentioned but auto-didactical practice of some teachers who have already embarked on the ASL journey. The former students we interviewed appreciated teaching in ASL and requested that it be used more frequently because they regard sign language as a crucial part of themselves, as Bo stated: “And for me, sign language is the access for everyone. Both in terms of family bonding, in terms of identity issues, in terms of education. So, for me, [sign] language is really everything. Without [sign] language, I probably would not be the person I am today. I would not have my friends. I would not have been in school the way I was. I would have faced a lot of barriers in my everyday life and I do not think I would have the quality of life that I have today.” This quote highlights the crucial importance of investing in foreign language acquisition via a high quality EFL and ASLFL teaching for DHH students. It is not merely an educational endeavor but a fundamental human right (United Nations, 2006).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

KU: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Invest‑igation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KG: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MK: Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was partially supported by the Fund for the Promotion of Young Researchers of the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Germany. The article processing charge was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – 491192747 and the Open Access Publication Fund of Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants who were willing to share their experiences in their EFL classrooms.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1447191/full#supplementary-material

References

Ay, S., and Şen Bartan, Ö. (2022). English language teaching model proposal for Deaf and hard of hearing students. RumeliDE Dil Ve Edebiyat Araştırmaları Dergisi 26, 1082–1097. doi: 10.29000/rumelide.1076386

Baker-Shenk, C., and Cokely, D. (1996). American sign language. A Teacher’s resource text on grammar and culture. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Baranowska, K. (2022). Exposure to English as a foreign language through subtitled videos: the impact of subtitles and modality on cognitive load, comprehension, and vocabulary acquisition. System 92:102295.

Bartz, M., and Eitzen, B. (2016). Chancen und Grenzen des Einsatzes von American Sign Language (ASL) im Englischunterricht in der Sekundarstufe II – Erfahrungen und wissenschaftliche Erkenntnisse. Hörgeschädigtenpädagogik 5, 193–199.

Becker, C., and Jaeger, H. (2019). Deutsche Gebärdensprache. Mehrsprachigkeit mit Laut- und Gebärdensprache. Tübingen: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag.

Bedoin, D. (2011). English teachers of deaf and hard-of-hearing students in French schools: needs, barriers and strategies. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 26, 159–175. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2011.563605

Berent, G. P. (2001). “English for deaf students: assessing and addressing learners' grammar development” in International seminar on teaching English to Deaf and hard-of-hearing students at secondary and tertiary levels of education: Proceedings. ed. D. Janáková (Prague, Czech Republic: Charles University, The Karolinum Press), 124–134.

Berlin Senate Department for Education, Youth, and Science . (2015). Teil C Moderne Fremdsprachen, Jahrgangsstufen 1–10. Available at: https://bildungsserver.berlin-brandenburg.de/fileadmin/bbb/unterricht/rahmenlehrplaene/Rahmenlehrplanprojekt/amtliche_Fassung/Teil_C_Mod_Fremdsprachen_2015_11_16_web.pdf (Accessed July 7, 2024).

Birinci, F. G., and Sarıçoban, A. (2021). The effectiveness of visual materials in teaching vocabulary to deaf students of EFL. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies 17, 628–645. doi: 10.52462/jlls.43

Csizér, K., and Kontra, E. H. (2020). Foreign language learning characteristics of deaf and severely hard-of-hearing students. Mod. Lang. J. 104, 233–249. doi: 10.1111/modl.12630

Csizér, K., Kontra, E. H., and Piniel, K. (2015). An investigation of the self-related concepts and foreign language motivation of young Deaf and hard-of-hearing learners in Hungary. Studies Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 5, 229–249. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2015.5.2.3

Domagała-Zyśk, E. (2011). “Students with severe hearing impairment as competent learners of English as a foreign language” in Proceedings of the international conference universal learning design (Brno: Masaryk University), 61–68.

Domagała-Zyśk, E. (2019). “Teaching Deaf and hard of hearing students English as a foreign language in inclusive and integrated primary schools in Poland” in The child with hearing impairment. Implications for theory and practice. eds. A. Zwierzchowska, I. Sosnowska-Wieczorek, and K. Morawski (Katowice: Akademia Wychowania Fizycznego).

Fister, I. (2017). Ich will, also kann ich! ‘Eine quantitative Vergleichsstudie über die Motivation beim Englischlernen von Kindern mit und ohne Hörschädigung. Das Zeichen 107, 442–453.

Kang, K. Y., and Scott, J. A. (2021). The experiences of and teaching strategies for Deaf and hard of hearing foreign language learners. Am. Ann. Deaf 165, 527–547. doi: 10.1353/aad.2021.0005

Kontra, E. H. (2013). “Language learning against the odds: retrospective accounts by deaf adults” in English as a foreign language for Deaf and hard-of-hearing persons in Europe – State of the art and future challenges. ed. E. Domagała-Zyśk (Wydawnictwo KUL), 93–111.

Kontra, E. H., and Csizér, K. (2013). An investigation into the relationship of foreign language learning motivation and sign language use among Deaf and hard of hearing Hungarians. Int. Rev. Appl. Linguist. Lang. Teach. 51, 1–22. doi: 10.1515/iral-2013-0001

Kontra, E. H., Csizér, K., and Piniel, K. (2015a). “Teaching and learning foreign languages in Hungarian schools for the hearing impaired: a Nationwide study” in Proceedings of ICED (Athens, Greece). 6–9; Available at: http://www.deaf.elemedu.upat ras.gr/index.php/iced-2015-proceedings (Accessed April 3, 2019).

Kontra, E. H., Csizér, K., and Piniel, K. (2015b). The challenge for Deaf and hard-of-hearing students to learn foreign languages in special needs schools. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 30, 141–155. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2014.986905

Kuckartz, U., and Rädiker, S. (2022). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung. 5th Edn: Beltz Juventa.

Kusters, A. M. J., and Friedner, M. I. (2015). “Introduction: deaf-same and difference in international deaf spaces and encounters” in It's a small world: International deaf spaces and encounters (ix-xxix). eds. M. Friedner and A. Kusters (Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press).

Landesfachkonferenz Englisch HK NRW (2019). Überarbeitetes Positionspapier der Landesfachkonferenz Englisch HK NRW.

Machová, P. (2019). “Teaching English to students with hearing impairments” in English language teaching through the Lens of experience. eds. C. Haase and N. Orlova (Cambridge Scholars Publishing), 223–238.

Nisha, M. V., and Gill, J. C. R. (2020). English language teaching approaches to Deaf and hard-of-hearing students in India. Journal of Xi’an University of Architecture & Technology 12, 1992–2001.

Parks, E., and Parks, J. (2008). Sociolinguistic Survey Report of the Deaf Community of Guatemala. SIL International. Available at: https://www.sil.org/system/files/reapdata/89/77/67/89776777358059644860474457686870926463/silesr2008_016.pdf. (Accessed June 10, 2020).

Pfau, R., Steinbach, M., and Woll, B. (2012). Sign language: An international handbook : Walter de Gruyter.

Poppendieker, R. (2011). Englischunterricht im bilingualen Konzept. Diskussionsrunde: Bilingualer Englischunterricht mit ASL, BSL oder DGS. DFGS Forum 19, 24–27.

Pritchard, P. (2004). TEFL for deaf pupils in Norwegian bilingual schools: Can deaf primary school pupils acquire a foreign sign language? Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Pritchard, P. (2011). Using a sign language in the teaching of english to deaf pupils. DFGS Forum. 19, 12–23.

Puri, I. R., Rodiatun, R., and Susanto, S. (2019). An analysis of learning English vocabulary for hearing impaired students at bhakti dharma Pertiwi special school 2017/2018. J. Eng. Educ. Stud. 2, 60–66. doi: 10.30653/005.201921.36

Quay, S. (2005). Education reforms and English teaching for the deaf in Japan. Deafness Educ. Int. 7, 139–153. doi: 10.1179/146431505790560338

Ramos Martin-Pozo, M . (2022). Teaching English as a foreign language to hearing impaired students: a teaching proposal. Available at: https://crea.ujaen.es/bitstream/10953.1/13548/1/Ramos_MartnPozo_Mara_TFM_Ingls.pdf (Accessed May 15, 2024).

Reilly, J., and McIntire, M. L. (1980). American sign language and pidgin sign English: What’s the difference? Sign Lang. Stud. 27, 151–192. doi: 10.1353/sls.1980.0021

Ristiani, A. (2018). Challenges in teaching English for the deaf students. Elite 3, 16–20. doi: 10.32528/ellite.v3i1.1773

Schembri, A., Cormier, K., Johnston, T., McKee, D., McKee, R., and Woll, B. (2010). “Sociolinguistic variation in British, Australian and New Zealand sign languages” in Sign Languages. ed. D. Brentari (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 476–498.

Steinbach, M., Albert, R., Girnth, H., Hohenberger, A., Kümmerling-Meibauer, B., Meibauer, J., et al. (2007). “Gebärdensprache” in Schnittstellen der germanistischen Linguistik. ed. J. B. Metzler (Stuttgart, Mezler), 137–185.

Stoppock, A. (2014). “Didaktisch-methodische Überlegungen zum Englischunterricht für Schüler mit einer Hörschädigung in der Grundschule” in Im Dialog der Disziplinen. Englischdidaktik – Förderpädagogik – Inklusion. eds. R. Bartosch and A. Rohde (Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier), 115–130.

Sultanbekova, A. (2019). Teaching English as a foreign language to Deaf and hard-of-hearing stu- dents at one school in Kazakhstan. Kasachstan: Nazarbayev University Graduate School of Education.

United Nations (2006). Conventions of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-persons-disabilities (Accessed May 15, 2024).

Uradarević, I. (2016). “Teaching English to Deaf and hard-of-hearing students in Serbia: a personal account” in English as a foreign language for Deaf and hard-of-hearing persons: Challenges and strategies. eds. E. Domagała-Zyśk and E. H. Kontra (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholar Publishing), 91–108.

Urbann, K. (2020). (Gebärden-)sprache im Englischunterricht. Erläuterungen zum Forschungsstand und Kernfragen der aktuellen Praxis. Das Zeichen 116, 474–485.

Villwock, A., Wilkinson, E., Piñar, P., and Morford, J. P. (2021). “Language development in deaf bilinguals: deaf middle school students co-activate written English and American sign language during lexical processing” in Cognition, vol. 211, 104642.

Woodward, J. C. (1973). Some characteristics of pidgin sign English. Sign Language Studies 3, 39–46. doi: 10.1353/sls.1973.0006

World Federation of the Deaf and World Association of Sign Language Interpreters (2019): Frequently Asked Questions about International Sign. Available at: https://wfdeaf.org/news/resources/faq-international-sign/ (Accessed July 7, 2024).

Keywords: Deaf, foreign language, teaching, interview, sign language, students

Citation: Urbann K, Gross K, Gervers A and Kellner M (2024) “Language means freedom to me” perspectives of Deaf and hard-of-hearing students on their experiences in the English as a foreign language classroom. Front. Educ. 9:1447191. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1447191

Edited by:

Ewa Domagala- Zysk, The John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin, PolandReviewed by:

Ingela Holmström, Stockholm University, SwedenKatarzyna Bienkowska, The Maria Grzegorzewska University, Poland

Copyright © 2024 Urbann, Gross, Gervers and Kellner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Katharina Urbann, a2F0aGFyaW5hLnVyYmFubkBodS1iZXJsaW4uZGU=

Katharina Urbann

Katharina Urbann Kristin Gross

Kristin Gross Alina Gervers

Alina Gervers Melanie Kellner

Melanie Kellner