- Department of Industrial Psychology, University of the Western Cape, Bellville, South Africa

Introduction: Toxicity among staff members of higher education institutions (HEIs) is often under-reported or not reported at all. Experiences of toxic leadership are deemed unmentionable within the consultative and collaborative ideals of HEIs. The underreporting of toxicity among HEI staff may stem from fear of retaliation, inadequate reporting structures, and concerns about alienation or not being taken seriously.

Method: The study explored experiences of leadership behaviours in a South African HEI to identify specific dimensions of toxic leadership behaviours. Using an interpretivist qualitative research design, the study involved analysing 39 interviews of secondary data from two datasets gathered by the research team, comprising 25 and 14 participant responses, respectively.

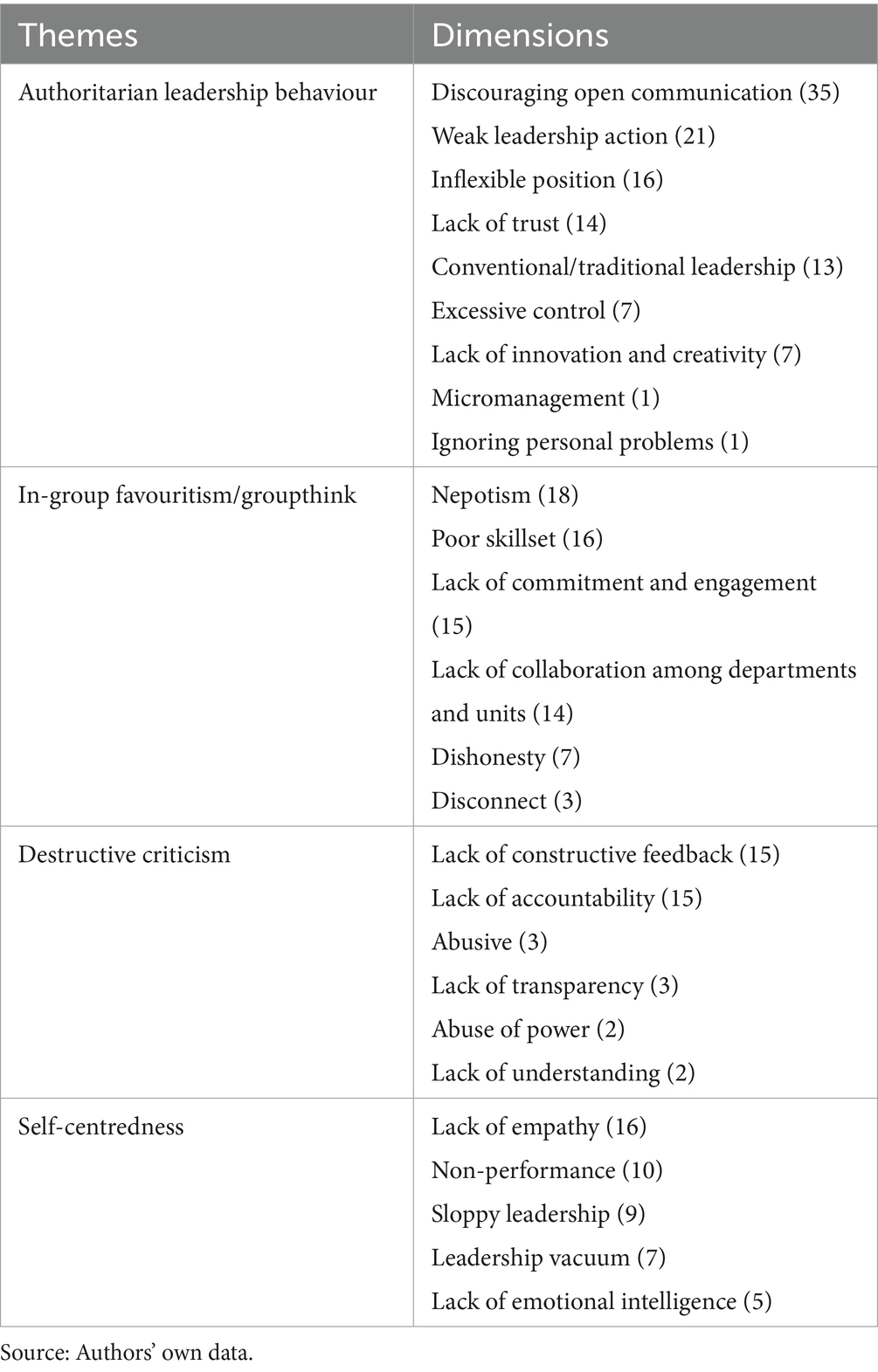

Results: The study identified four distinct themes of toxic leadership behaviour – authoritarian leadership behaviour, in-group favoritism/groupthink, destructive criticism and self-centredness – with authoritarianism being the most common behaviour displayed.

Conclusion: Presence of toxic leadership within the South African University community, emphasising the necessity for a comprehensive approach and strategy to address this behaviour.

Introduction

South African higher education institutions (HEIs) have experienced notable changes to keep up with societal shifts and global requirements (Menon and Motala, 2021). Amid these changes, the problem of toxic leadership has emerged as a worrying, albeit frequently disregarded, obstacle (Maxey and Kezar, 2015). Empirical studies have shown the factors influencing followers’ perceptions of leaders’ apologies after wrongdoing, mapping the elements of an effective apology and identifying situational moderators to better equip and empower leaders when they need to apologise (Coustas and Price, 2024). Research in the realm of corporate crisis communication is expanding and delves into examining how the development and delivery of corporate apologies affect stakeholders of a company in order to handle public image and relationships (e.g., Bentley and Ma, 2020). Research conducted by Shao et al. (2022) has explored variables that influence the perception of an effective corporate apology and the ramifications of a successful apology on the performance of the organisation and other metrics. Toxic leadership, which includes actions like oppressive supervision, the absence of openness and neglect of subordinates’ welfare, can have far-reaching negative effects on academic institutions (Lašáková et al., 2016). Toxic leaders’ traits and actions characteristically exhibit self-centred attitudes, excessive control and behaviours that negatively affect their subordinates and organisations (Snow et al., 2021; Klahn, 2023) and the relationships between an institution and its employees. Toxic leadership undermines faith, suppresses innovation and obstructs the creation of a supportive and flourishing academic atmosphere (Hyson, 2016). Because toxic leadership at South African HEIs may significantly impede the development of a thriving academic community. Understanding its dimensions and implementing effective measures to deal with toxicity are pivotal for cultivating a positive workplace atmosphere (Krasikova et al., 2013). Wherein leaders prioritise the well-being and job security of their employees to enhance innovation in the workplace (Bushuyev et al., 2023). Promoting effective leadership, fostering innovation and creating a positive work environment would play a crucial role in ensuring institutional sustainability in the higher education sector. Healthy leadership plays a fundamental role in the success of any organisation. Leaders who possess the ability to inspire and motivate their employees are instrumental in creating a positive work environment conducive to productivity and growth (Lynch, 2023). Specifically targeting the environment’s BANI (brittle, anxious, non-linear, incomprehensible) characteristics is necessary to address the challenges posed by the complex and rapidly changing nature of the modern education system (Ramaditya et al., 2023). Nurturing a healthy work environment demands addressing toxic leadership through strategies focused on leadership development and sustainable performance (Naicker and Mestry, 2016).

The manifestation of leadership traits, whether they lean towards destructive or positive leadership, is intrinsically linked to the contextual environment in which leadership operates. This context is primarily defined by the employment setting wherein leaders showcase their aptitude to lead in a conducive workplace atmosphere (Maximo et al., 2019). The dynamics between university administrators, university staff and governing authorities play a pivotal role in shaping the organisational culture and overall functioning of the institution (Hackett, 2017). Leaders in HEIs must maintain the delicate balance between fostering a healthy, productive work environment and addressing instances of toxic behaviour or destructive leadership that may jeopardise the welfare of employees and the institution itself (Kramer et al., 2010).

Addressing toxic leadership in HEIs necessitates a nuanced understanding of employment relations, as these relationships extend beyond contractual agreements (Goods et al., 2019). They encompass the social, ethical and legal dimensions of the academic environment, requiring careful consideration of the impact of leadership behaviours on employee well-being, organisational commitment and the broader mission of the institution (Ofori, 2008). Exploring and implementing effective strategies to mitigate toxic leadership are imperative for fostering a harmonious and productive higher education community (Oruh et al., 2021). According to Senge and Scharmer (2008), the cultivation of such a community is not a mere aspiration but an absolute necessity.

Research problem

Toxic leadership has emerged as a pressing issue within the domain of employment relations, transcending various industries and organisational settings. The manifestation of toxic leadership has elicited profound concerns due to its potentially detriment impacts on individuals and organisations. According to Almeida et al. (2022), toxic leadership behaviours encompass a spectrum of abusive, manipulative, intimidating and unethical conduct. The injurious effects of these behaviours on employees have been increasingly recognised (Mehta and Maheshwari, 2013). Extensive research has implicated exposure to toxic leadership in heightened staff turnover, reduced job satisfaction, diminished organisational commitment and adverse psychological outcomes, including anxiety, burnout, depression and disengagement (Maran et al., 2022). This problem of toxic leadership is particularly conspicuous at HEIs, where leaders are entrusted with the responsibility of fostering an environment conducive to learning, innovation and personal development and where the roles of educators, administrators and support staff extend beyond the provision of services to encompass the intellectual moulding and personal development of students and contributing to their institution’s academic mission (Hargreaves and Fink, 2012). The Sustainable Development Goals are set of 17 international goals adopted in 2015 by the United Nations to address poverty, hunger, promote good health and quality education. Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG4) aims to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education for all, promoting lifelong learning opportunities. It emphasises the transformative power of education in achieving global stability, fostering tolerance, and broadening access to opportunities (Brissett, 2023). In this context, toxic leadership not only jeopardises employee welfare but poses a substantial risk to the quality of education and research, affecting Sustainable Development Goal 4 (Quality Education), thereby hindering the achievement of the SDG objective. As the unique challenges and dynamics that operate within academic settings may deviate from those observed in other industries, this research undertook an in-depth exploration of the multifaceted issues of toxic leadership, with a specific focus on how it manifests within HEIs (Bibri, 2018). Through this focus, the study seeks to contribute to the advancement of knowledge of toxic leadership and the enhancement of leadership practices and appropriate strategies to comprehensively address it within the academic sphere and in the broader employment context.

Research objectives

The study aims to understand leadership behaviour in South African HEIs, with a specific focus on toxic leadership. The main objective is to explore and identify various dimensions of toxic leadership behaviour exhibited by management in South African higher education.

Literature review

According to Koçak and Demirhan (2023), numerous researchers and academics have developed methods and approaches to categorise and explain different experiences of what is known as toxic leadership behaviour. Toxic leadership behaviours exhibit common characteristics and are discussed from multiple perspectives in the literature (Koçak and Demirhan, 2023). Alanezi (2022) analysed toxic leadership behaviours in educational institutions, classifying them according to “human relations skills, authoritarian leadership, management skills, and professional ethics.” Green (2014) also examined toxic leadership actions in educational settings, citing egotism, ethical lapses, incompetence and neuroticism as contributing factors. Karli (2022) recognises toxic leadership conduct as actions that educators perceive as erratic, unreliable and varying according to the leader’s daily emotional state. Moreover, Oplatka (2023) defines self-centred actions, a lack of emotional understanding, making decisions in isolation and viewing the school, teachers or students purely as business associates as negative behaviours in school leaders. Kirbac (2013) opined that a toxic culture could be attributed to unfair practices, harmful communication and decision-making processes, as well as unethical behaviours demonstrated by leaders.

Schmidt (2008) identified five dimensions of toxic leadership behaviour, namely unpredictability, authoritarian leadership, narcissism, abusive supervision and self-promotion. Similarly, Fahie (2019) highlights eight dimensions and categorisations of toxic leadership in a study on the impact of toxic leadership in Irish higher education: (1) Undermining followers’ self-worth by belittling, marginalising or degrading employees; (2) Lack of honesty by being deceitful, shifting blame onto others for the leader’s mistakes, going back on promises or bending rules to achieve goals; (3) Abusive behaviour by threatening employees’ professional or personal security; (4) Social exclusion by excluding individuals from social gatherings; (5) Creating division by ostracising employees and accusing them of not being team players; (6) Favouritism by showing unfair preference; (7) Endangering followers’ safety through physical aggression or forcing employees to endure hardship; and (8) Laissez-faire style by failing to listen or respond to employee concerns, being disengaged, suppressing dissent and criticising employees for speaking up (Fahie, 2019).

Lipman-Blumen (2005) and Heppell (2011: 29) described toxic leaders as individuals whose destructive behaviours and dysfunctional personal qualities have a serious and enduring harmful effect on the individuals, families, organisations, communities and even entire societies they lead. Lipman-Blumen (2011) identified ambition, ego, arrogance, immorality, avarice, insensitivity and the absence of integrity as key personal traits of toxic leaders. A later study by Yavaş (2016) also emphasised egocentrism as a central component of toxic leadership, along with negative mood, lack of appreciation, instability, uncertainty and autocratic management. The literature on toxic leadership supports categorisation based on the impact of toxic leadership behaviours. These behaviours encompass various dimensions including destructiveness (Einarsen et al., 2007), disregard for subordinate well-being and harmful or abusive behaviour (Tepper, 2000; Wilson-Starks, 2003; Lipman-Blumen, 2005). Other discussed aspects include micromanagement, authoritarianism (Lipman-Blumen, 2005), commanding behaviour, narcissistic tendencies (Reed, 2004; Lipman-Blumen, 2005), lack of integrity, divisiveness, unpredictability and self-promotion (Schmidt, 2008).

A recent study by Herbst and Roux (2023) explores the impact of toxic leadership on the gender gap in senior management roles in South African universities. Female participants reported experiencing significant levels of toxic leadership, highlighting the challenges women face in leadership positions in the higher education sector. The traits and behaviours of toxic leaders revealed in the study align with extant literature on toxic leadership, indicating potentially serious and long-lasting negative effects on women in universities in South Africa, including the implication that toxic leadership hinders the advancement of women employed in HEIs (Herbst and Roux, 2023).

It is important to note that the categorisation of toxicity does not necessarily include intent. Toxic leadership may include behaviours of the leader that were not intended to cause harm, such as insensitivity, thoughtlessness or lack of competence, but that are negatively experienced by followers (Einarsen et al., 2007). Moreover, in the present study, toxic leadership is viewed from the perspective of the recipient. Hence, the outcomes of the leader’s behaviours are more relevant than the leader’s intent. This approach emphasises that the outcomes of a leader’s behaviours are more relevant than the leader’s intent. By focusing on how the leader’s actions affect the individuals on the receiving end, this perspective underscores the importance of the impact of toxic leadership on staff members, regardless of the leader’s intentions or motivations. This shift in focus allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the detrimental effects of toxic leadership within higher education institutions.

Research methodology

Classic Grounded Theory is a qualitative research methodology that generates theories from data through continuous comparison, theoretical sampling, coding, memo writing, and identifying a core category, emphasising theory emergence rather than preconceptions (Nathaniel, 2019). Within the realm of classic grounded theory (Nathaniel, 2022), the research methodology employed in this study involves analysing qualitative secondary data obtained from interviews with leaders in a reputable academic institution in South Africa’s higher education sector. The methodology used in the analysis comprised data source and selection, and data analysis techniques (qualitative content analysis, and thematic analysis).

Data source and selection: The existing data was obtained from two distinct studies conducted by the research team that explored leadership experiences in a South African public HEI. In total, the research team conducted interviews with 39 participants and the collected data resulted in a total of 39 datasets that were analysed. The first study (n = 25) included in-person, semi-structured interviews within three leadership strata at the university: executive management (5 participants), senior management (10 participants), and middle management (10 participants). Participants were selected based on several criteria, including availability, willingness to participate, effective communication skills and relevant knowledge and experience, as recommended by Magilvy and Thomas (2009).

The second study (n = 14) involved semi-structured interviews with 10 female participants and 4 male participants, 6 of whom held the position of associate professor and 8 were full professors. These participants represented 5 faculties and 11 departments. To ensure maximum participation and an even distribution of population characteristics, stratified random sampling was employed (Bryman, 2012). This was followed by snowball sampling, where initial contacts reached out to relevant participants to expand the research to gather diverse viewpoints (Mertens and Ginsberg, 2009).

The first study focused on contemporary leadership behaviour and its impact on leadership effectiveness in a public university in South Africa. The study identified leadership characteristics and influencing factors of effective leadership in a VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous) environment, based on existing literature. It investigated these characteristics and factors to understand how they are experienced in practice to answer the research questions: “What are the behaviours and characteristics of effective leaders within HEIs in a VUCA environment?” and “Which factors influence effective leadership behaviours?” The investigation aimed to gather comprehensive information from the participants to understand their experiences of leadership behaviour at an HEI.

The objective of the second study was to explore and extract senior academics’ subjective experiences of both negative and positive leadership behaviours to respond to the research question: “What are senior academics’ experiences of leadership behaviours at an HEI in South Africa?” This study aimed to gain an understanding of the experiences of top-level management at the institution.

The selection of these two studies was motivated by the pursuit of datasets characterised by superior quality and their capacity to yield comprehension of leadership experiences within the South African higher education sector (Enslin, 2023). Since the participants align with the defined criteria, the selection represents a strategic approach to secure data that is not only dependable but also pertinent to the overarching research objectives (Ravitch and Carl, 2019). This data constitutes an invaluable resource shedding light on facets of leadership in the South African higher education context, thus enhancing the overall quality and significance of the research outcomes.

Data analysis techniques

Qualitative content analysis: The research utilised a qualitative content analysis approach to analyse the interview transcripts and gain insights into the research questions. The analysis interpreted the written research data based on language characteristics and followed a naturalistic paradigm (Selvi, 2019). This process extracts descriptive knowledge about the phenomena under investigation. A systematic methodology was employed to code, categorise, theme and evaluate the data to identify patterns (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005; Assarroudi et al., 2018). This approach helped to uncover meaningful relationships and insights related to the research questions.

Furthermore, the research project used content analysis guided by both inductive and deductive approaches. Inductive analysis generates meaning from the transcribed interview texts by moving from manifest to latent content (Magilvy and Thomas, 2009; Erlingsson and Brysiewicz, 2017). The inductive approach allows for open-ended exploration, while the deductive approach validates findings against established theories and concepts of leadership behaviour within HEIs. The study utilised Atlas.ti (version 23) software for the qualitative content analysis. This software offers advanced features and functionalities that streamline the research process, including data management, coding and visualisation of qualitative data. The use of Atlas.ti improved the efficiency and user-friendliness of the qualitative content analysis, ultimately contributing to high-quality research findings.

Thematic data analysis: By reading and reviewing the transcribed interviews multiple times, we developed a more profound and comprehensive understanding of the phenomena being investigated, as suggested by Elo and Kyngäs (2008). Research findings and existing theories were utilised to establish formative themes. Data was objectively and accurately analysed with the aid of existing theories (Mayring, 2000). The data was analysed by transcribing written interviews and identifying meaningful units. The meaningful units were then summarised and assigned preliminary codes (Mayring, 2000; Assarroudi et al., 2018). The preliminary codes were grouped and categorised based on their similarities, differences and meanings. The results of this process were defined as ‘generic categories’ (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008). A comparison was conducted between the generic and main categories to establish a conceptual and logical connection between the two. This process facilitated the incorporation of generic categories into existing main categories (Zhang and Wildemuth, 2009). A comprehensive description of the data analysis and enumeration of research findings ensured a logical and systematic representation of the research outcomes (Elo and Kyngäs, 2008; Assarroudi et al., 2018).

Ethical considerations

The institution’s ethics review board approved the use of secondary data and both datasets used in the study received ethical clearance. The participants consented to the use of their anonymised data, including for further research projects and analysis. We followed best practices for data anonymisation to prevent inadvertent identification of individuals (Hayanga, 2021) and confirmed ownership and rights associated with pre-existing data, respecting any data use restrictions. Robust security measures were implemented to prevent unauthorised access or data leaks, preserving the integrity of the research. The study complied with laws and regulations relevant to data protection and privacy throughout the research process (Tyler, 2022).

Findings

After analysing the secondary data sets, we uncovered a variety of toxic leadership behaviours exhibited by members of university management. We identified 30 dimensions of these traits, which were then grouped into four main themes. The frequency counts of these themes (displayed in order of frequency) and the thematic codes assigned are shown in Table 1.

Theme 1: Authoritarian leadership behaviours

Authoritarian leadership is a style of leadership in which the leader or manager makes decisions and gives directives with little or no input from subordinates (Klahn and Male, 2022). In this leadership style, the leader maintains strict control over the decision-making process and expects subordinates to follow their instructions without question (Alanezi, 2022). The authoritarian leadership style, characterised by demanding strict obedience and discouraging open communication (Inman, 2023), emerged as a prominent form of toxic leadership behaviour. These leaders tend to make decisions unilaterally and may not seek input from team members, as evidenced by the experiences shared by participants. Many qualified colleagues were overlooked for positions due to the conventional/traditional leadership approaches and inflexible positions adopted by senior management.

The faculty and the hierarchy were supposed to consider and discuss with the candidates. And there was never any discussion, it was just given to my colleague, so that was...that was not open, that wasn’t transparent. – Participant 7, male, seven years’ tenure.

Another participant highlighted how excessive control by leaders limited their autonomy and stifled innovation and creativity.

If I look at how I can actually spend my budget, those decisions have already been made, and I’m just saying yes, yes, yes. I’ve got no autonomy to change how I spend my budget. – Participant 21, male, 15 years’ tenure.

The frustration with discouraging open communication was echoed by Participant 24, who felt that their opinions and perspectives were not considered, and the process lacked consensus-seeking, pointing towards weak leadership action:

I do not think that there’s even been decisions made where input was requested, like I never had the opportunity to give input. My consensus was never [sought]…It’s very easy to maybe just have a survey and get people’s opinion on something. Because it just as an employee it just does not feel like it’s consensus-seeking from my perspective. – Participant 24, female, eight years’ tenure.

Discouraging open communication emerged as the most frequently cited form of toxic leadership behaviour, with 35 occurrences in the transcripts.

The Head of Department gets information from the Management Committee meeting that’s not shared in any other way, okay, apart from the faculty board minutes, but you get that six months later, and that’s too late, so you are not privy to the conversations that’s happening about where the [institution] is going. – Participant 1, male, 13 years’ tenure.

Within theme 1, participants identified several toxic leadership behaviours, such as excessive control, conventional/traditional leadership, lack of trust, lack of innovation and creativity, inflexible positions, ignoring personal problems, weak leadership action and discouraging open communication. The participants emphasised their inability to make independent decisions and the obligation for all decision-making to be carried out by the university leadership within the hierarchical structure of the HEI. These excerpts from the interview transcripts represent the most frequently occurring descriptions of experiences related to toxic leadership characteristics in South African HEIs.

Theme 2: In-group favouritism/groupthink

In-group favouritism refers to the tendency of leaders or decision-makers to show favouritism and support to those within their inner circle while being less receptive to outside opinions or challenges. Groupthink, on the other hand, occurs when members of a close-knit group prioritise harmony and consensus over critical thinking and open discussion (Klahn and Male, 2022). Both these behaviours can hinder effective leadership and decision-making (Horak and Suseno, 2023).

In-group favouritism and groupthink emerged as fundamental characteristics of toxic leadership attitudes (Kizrak and Öztürk, 2023) in our data. Participants reported that leaders frequently provided more assistance to members of their own group, demonstrating a lack of commitment and engagement towards others. The data suggests that many current leaders come from the most powerful or influential groups of the past, implying that the current leadership is largely composed of individuals who were also part of the previously dominant group:

So, a lot of the current leadership come from the dominant clique of the past. – Participant 6, male, 12 years’ tenure.

Nepotism, including cronyism, may lead to the use of malpractices to distribute resources and recruit inappropriate people (Tekiner and Aydın, 2016). The transcripts revealed numerous attestations to the practice of nepotism among the ranks of leadership, with this code showing the highest frequency count of 18 occurrences of aspects of nepotism:

There’s a severe imbalance between the way that my colleague has been able to manipulate getting extra staff assigned to his group and getting the Dean to give him posts…he’s been able to persuade the Dean and the Head of Department to give permanent academic posts to several of his students, whereas, despite my requests over many years for a similar consideration, the head of the department and the Dean have never considered that…and I do think that allows an element of nepotism. – Participant 7, male, 13 years’ tenure.

Another experience of toxic leadership behaviour in the area of in-group favouritism was the formation of cliques among leaders who got along well with each other but struggled to manage challenges from subordinates. This often created a lack of collaboration between departments and units:

I have the feeling that there’s a leadership clique who...who get on very well with each other, um, and who do not react very well to when their assumptions are being challenged. If you are willing to engage in that game and not be too confrontational, and make sure that you, um, frame your questions and objections in the politest, least threatening way possible, then it’s possible to get quite far. – Participant 2, female, nine years’ tenure.

While this in-group approach could lead to progress within the group or clique, it may also impact the institution’s effectiveness by perpetuating a toxic environment.

Theme 2 highlights leadership behaviours that promote in-group favouritism and groupthink, such as lack of collaboration across departments, dishonesty, inadequate skills, disconnection and low commitment and engagement. Most participants’ comments underscored the existence of toxic leadership practices associated with in-group favouritism and groupthink in the South African higher education system, wherein cliques are formed and used to advance its members whenever there is a promotion or higher position available in the institutions or to close ranks when presented with challenges to their privileged positions.

Theme 3: Destructive criticism

Destructive criticism is one of many destructive characteristics that toxic leaders exhibit (Batchelor et al., 2023), wherein toxic leaders intentionally and systematically behave in ways that violate the interests of the organisation’s members and stakeholders (Holzer et al., 2021). Destructive criticism from a toxic leader can undermine an individual’s sense of dignity, self-worth and effectiveness, leading to exploitative, destructive, demeaning and devaluing work experiences (Snow et al., 2021). Destructive criticism, defined as feedback or comments that are unhelpful and meant to undermine someone (Lakeman et al., 2022), has emerged as a significant form of toxic leadership behaviour. Its prevalence reflects a culture of caretaking within a closed social environment where dissent and criticism are viewed with suspicion or as threatening. This suggests a lack of transparency and a lack of accountability on the part of the leaders:

We call it a culture of caretaking, but always within this very, umm...closed social bubble, and in the context where dissent and criticism were met with suspicion. – Participant 2, male, 11 years’ tenure.

Participants also reported instances where leaders used various means to dominate a discourse such as talking excessively, becoming forceful and attempting to silence the voices of staff through “noise.” This reflects an abuse of power and a lack of understanding:

The leaders sometimes if they talk too much, they become forceful; rather the leaders they impose destructive noise to block the constructive voice from the lower rank staff. So, this is very important to me. – Participant 3, female, 14 years’ tenure.

The experiences shared by participants reflected concerns about whether individuals experiencing abusive behaviours were being utilised appropriately or if their well-being was considered. This led to insecurity and staff “playing games” in attempts to enhance their individual circumstances:

It’s about whether you are really being used and abused, or actually, are they also considering your well-being? So, because of that, people start playing games to…to try and improve their individual situations. – Participant 6, male, nine years’ tenure.

Numerous participants expressed frustration about the lack of constructive feedback from their leaders. The lack of constructive feedback was mentioned 15 times in the transcripts under the theme of destructive criticism:

Unable to get feedback, you know, it’s like, the only feedback that I got is negative. But even the negative feedback as well, it’s not recorded whereby you are able to see where you can improve on it. – Participant 25, male, 11 years’ tenure.

Participant 25’s experience not only indicated a lack of constructive feedback but also a lack of accountability by the leader for the personal and professional growth of employees.

Theme 3 centred on participants’ views on the nature of destructive criticism, which is recognised as a form of toxic leadership behaviour characterised by negative traits such as the abuse of power, abusive language, lack of transparency, accountability and understanding (Balayn et al., 2021). This kind of criticism is detrimental to the recipient, often driven by emotions, personal in nature and negatively impacts team cohesion and the individual receiving the criticism (Makwana, 2019).

Theme 4: Self-centredness

Self-centred toxic leadership behaviour is similar to selfishness and refers to leaders who prioritise their own needs, desires and interests while disregarding the needs and problems of others (Hossain, 2023). This type of leadership has no concern for subordinates and the organisation and leads to negative effects (Lynch, 2023). The self-centred leader tends to be egotistical, arrogant and lacks empathy towards others (Koçak and Demirhan, 2023). Participants’ experiences revealed instances where employees experienced a lack of empathy and sloppy leadership behaviour from their line managers:

…there were times that I think once for eight weeks, I did not speak to my Head of Department once. So, there was no [P1] ‘how are you doing? Are you okay?’ – Participant 1, male, 12 years’ tenure.

Participant 2 confirmed similar experiences of a leadership vacuum and lack of emotional intelligence in leaders:

At the moment we feel very much that we sort of have to muddle through on our own. – Participant 2, male, 15 years’ tenure.

Several participants remarked on the lack of empathy from the leaders, which was a recurring code under the theme of self-centredness with a frequency count of 16:

You see, okay, I think it’s all about them. I question whether they can self-regulate, I question whether they can be empathetic, I question whether they are great motivators. Because sometimes the way they respond is questionable. – Participant 19, male, 12 years’ tenure.

Participant 5 suggested that individuals, including leaders, have their own needs for growth and sometimes may lack emotional intelligence in their attempts to advance their own interests:

Yes, and they disrupt things and, um...I do not know, it’s...I think each person sort of has an agenda. They have their own agenda, their own need for growth, and if that means that you have got to stop someone else, and you take over. – Participant 5, male, eight years’ tenure.

Participants highlighted how sloppy leadership within the university failed to prioritise the well-being of staff. The leaders who prioritised power over their consideration of employees were criticised:

Yes, to a certain...yes, it does suit those that are in power. Umm...and there’s no actual...well-being considered. They do not really consider the well-being of their staff. – Participant 6, female, nine years’ tenure.

Participant 25 extended the critique of leaders’ self-centredness by highlighting the education focus of the institution, not only in terms of being student-centred but on behaviours or practices that “enrich” the staff and university leadership:

If I had to put it that way, instead of the core business of why we are here, for students, it’s not student centred and so on and so forth but you know it’s to enrich each other definitely. So that is the second component that I would probably say, and it leaves things to be questionable. – Participant 25, male, seven years’ tenure.

Within theme 4, several participants shared their observations regarding leaders who exhibit self-centred behaviours, which were considered toxic, not only for the well-being of subordinates but damaging to the institution’s performance and its mission.

Discussion

The research aimed to explore and identify different dimensions of toxic leadership behaviour experienced in South African HEIs. The findings revealed disturbing insights into the prevalence of toxic leadership traits exhibited by executive and senior managers in South African HEIs. The four main themes identified—authoritarian leadership behaviour, in-group favouritism/groupthink, destructive criticism and self-centredness—paint a concerning picture of the leadership culture in these universities.

According to the extant literature, authoritarian leadership is a commonly observed leadership behaviour among leaders in HEIs (Akanji et al., 2020). This was confirmed in the current study as the most prevalent form of toxic leadership, as reported by the highest number of participants, is authoritarian leadership. Several participants cited authoritarian characteristics exhibited by university leaders such as micromanagement, excessive control, traditional leadership approaches, lack of trust, lack of innovation and creativity, inflexibility, disregard for personal problems, discouragement of open communication and weak leadership actions (Benwahhoud, 2023). Authoritarianism not only undermines the autonomy and decision-making abilities of staff but also fosters an atmosphere of fear and disengagement.

The prevalence of in-group favouritism and groupthink is particularly alarming. The reports of nepotism, lack of collaboration between departments and the formation of insular leadership cliques suggest a deeply entrenched culture of cronyism and exclusion. The prevalence of these behaviours in our study shows that cliques and in-group thinking are not only practised but tolerated. This not only breeds resentment and distrust among staff but also perpetuates a cycle of mediocrity, as promotions and opportunities are awarded based on allegiances rather than merit. Furthermore, such behaviours cause high levels of stress for those who are not part of the in-group and may lead to performance problems.

The theme of destructive criticism highlights a troubling lack of transparency, accountability and constructive feedback within these institutions. Leaders who resort to the abuse of power and abusive language and exhibit a general lack of empathy towards staff create a demoralising and counterproductive work environment. Such behaviour not only undermines the dignity and self-worth of employees but also hinders their personal and professional growth. Studies show that exposure to stressful and risky circumstances can lead to destructive leadership behaviours, even in individuals who would not typically exhibit such behaviours (Fors Brandebo, 2020). These behaviours can have negative personal impacts on the leaders, their organisations (through the negative perceptions of others) and their subordinates (such as worsened health and decreased job satisfaction; Padilla et al., 2007; Schyns and Schilling, 2013).

Finally, the findings revealed that participants highlighted leaders’ self-centred behaviours, which were characterised by a lack of empathy and emotional intelligence, as well as issues with performance, leadership sloppiness and a noticeable lack of leadership presence (Paltu and Brouwers, 2020). The experience of self-centred leadership may negatively impact the quality of social exchanges between the leaders and employees, resulting in work alienation (Hawass, 2022). Leaders who prioritise their interests and agendas over those of the institution and its stakeholders create a toxic environment that is detrimental to the core mission of higher education. These findings emphasise the importance of effective and efficient leadership to a flourishing academic community in HEIs (Ramaditya et al., 2023).

Conclusion

We investigate the experiences of high-ranking employees in relation to toxic leadership in HEIs. While participants identified various dimensions of toxic leadership behaviour among the HEI leadership, it should be noted that not all leaders in this HEI or HEIs in South Africa generally display toxic leadership behaviour. Indeed, some participants referred to leaders who exhibit non-toxic leadership behaviour. For example, P13 stated: “I think it’s a bit of a mixed bag. I think some of the executive leadership are excellent. And I think, some are not….” However, the presence of toxic leadership behaviour can adversely affect organisational performance and employee well-being (Oruh et al., 2021).

The findings suggest that toxic leadership behaviours are deeply entrenched within the culture of the South African university, with the far-reaching consequences of such behaviours not only affecting the morale and well-being of staff but also the overall quality of education, research and the institution’s reputation. An urgent and concerted effort to root out toxic leadership practices is called for. Implementing measures such as leadership training, accountability mechanisms and fostering a culture of open communication and collaboration may help mitigate toxicity (Klahn, 2023; Lynch, 2023). Additionally, overtly promoting diversity and inclusion at all levels of leadership could help break down the insular cliques and cronyism that enable (and require) toxic behaviours to thrive.

Ultimately, addressing toxic leadership in South African universities is not only a matter of institutional health but also a societal imperative. HEIs play a vital role in shaping the future of the country through providing high-quality education (aligned to the UN Sustainable Development Goal 4), and their leadership cohorts should exemplify and live the values of integrity, empathy and excellence that all these institutions strive to impart.

Data availability statement

The data analysed in this study is subject to the following licences/restrictions: the data will be provided when requested because it is university data with its policy. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to b29sYWJpeWlAdXdjLmFjLnph.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of the Western Cape. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

OO: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MP: Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. CV: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Akanji, B., Mordi, C., Ituma, A., Adisa, T. A., and Ajonbadi, H. (2020). The influence of organisational culture on leadership style in higher education institutions. Pers. Rev. 49, 709–732. doi: 10.1108/PR-08-2018-0280

Alanezi, A. (2022). Toxic leadership behaviours of school principals: a qualitative study. Educ. Stud. 1–15, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2022.2059343

Almeida, J. G., Den Hartog, D. N., De Hoogh, A. H., Franco, V. R., and Porto, J. B. (2022). Harmful leader behaviours: toward an increased understanding of how different forms of unethical leader behaviour can harm subordinates. J. Bus. Ethics 180, 215–244. doi: 10.1007/s10551-021-04864-7

Assarroudi, A., Heshmati Nabavi, F., Armat, M. R., Ebadi, A., and Vaismoradi, M. (2018). Directed qualitative content analysis: the description and elaboration of its underpinning methods and data analysis process. J. Res. Nurs. 23, 42–55. doi: 10.1177/1744987117741667

Balayn, A., Yang, J., Szlavik, Z., and Bozzon, A. (2021). Automatic identification of harmful, aggressive, abusive, and offensive language on the web: a survey of technical biases informed by psychology literature. ACM Transactions on Social Computing (TSC) 4, 1–56. doi: 10.1145/3479158

Batchelor, J. H., Whelpley, C. E., Davis, M. M., Burch, G. F., and Barber, D. III (2023). Toxic leadership, destructive leadership, and identity leadership: what are the relationships and does follower personality matter? Business Ethics and Leadership 7, 128–148. doi: 10.21272/bel.7(2).128-148.2023

Bentley, J. M., and Ma, L. (2020). Testing perceptions of organizational apologies after a data breach crisis. Public Relat. Rev. 46:101975. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2020.101975

Benwahhoud, N (2023). A change in performance when working under two different leaders. Doctoral thesis, University of the Cumberlands.

Bibri, S. E. (2018). A foundational framework for smart sustainable city development: theoretical, disciplinary, and discursive dimensions and their synergies. Sustain. Cities Soc. 38, 758–794. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2017.12.032

Bushuyev, S., Bushuyeva, N., Murzabekova, S., and Khusainova, M. (2023). Innovative development of educational systems in the BANI environment. Scientific J. Astana IT University 14, 104–115. doi: 10.37943/14YNSZ2227

Coustas, C., and Price, G. (2024). Factors influencing followers’ perceptions of the effectiveness of their leaders’ apologies. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 50:12. doi: 10.4102/sajip.v50i0.2170

Einarsen, S., Aasland, M. S., and Skogstad, A. (2007). Destructive leadership behaviour: a definition and conceptual model. Leadersh. Q. 18, 207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.03.002

Elo, S., and Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 62, 107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

Enslin, E . (2023). The conceptualisation, development and validation of a south African organisational leadership scale. Doctoral thesis, University of South Africa.

Erlingsson, C., and Brysiewicz, P. (2017). A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. African J. Emerg. Med. African Federation for Emergency Med. 7, 93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.afjem.2017.08.001

Fahie, D. (2019). The lived experience of toxic leadership in Irish higher education. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 13, 341–355. doi: 10.1108/IJWHM-07-2019-0096

Fors Brandebo, M. (2020). Destructive leadership in crisis management. Leadersh. Org. Dev. J. 41, 567–580. doi: 10.1108/LODJ-02-2019-0089

Goods, C., Veen, A., and Barratt, T. (2019). “Is your gig any good?” Analysing job quality in the Australian platform-based food-delivery sector. J. Ind. Relat. 61, 502–527. doi: 10.1177/0022185618817069

Green, J. E. (2014). Toxic leadership in educational organizations. Educ. Leadership Rev. 15, 18–33.

Hackett, E. J. (2017). “Science as a vocation in the 1990s: the changing organizational culture of academic science” in Research ethics. ed. K. D. Pimple (London: Routledge), 253–291.

Hawass, H. H. (2022). Self-cantered leadership and work alienation: a negative social exchange perspective. Delta University Scientific J. 5, 387–404. doi: 10.21608/dusj.2022.275553

Hayanga, B. A. (2021). The effectiveness and suitability of interventions for social isolation and loneliness for older people from minoritised ethnic groups living in the UK (Doctoral dissertation, UCL (University College London)).

Heppell, T. (2011). Toxic leadership: applying the Lipman-Blumen model to political leadership. Representation 47, 241–249. doi: 10.1080/00344893.2011.596422

Herbst, T. H., and Roux, T. (2023). Toxic leadership: a slow poison killing women leaders in higher education in South Africa? High Educ. Pol. 36, 164–189. doi: 10.1057/s41307-021-00250-0

Holzer, J., Lüftenegger, M., Korlat, S., Pelikan, E., Salmela-Aro, K., Spiel, C., et al. (2021). Higher education in times of COVID-19: university students’ basic need satisfaction, self-regulated learning, and well-being. Aera Open 7:233285842110031. doi: 10.1177/23328584211003164

Horak, S., and Suseno, Y. (2023). Informal networks, informal institutions, and social exclusion in the workplace: insights from subsidiaries of multinational corporations in Korea. J. Bus. Ethics 186, 633–655. doi: 10.1007/s10551-022-05244-5

Hossain, M. S. (2023). Sociological foundations of education: Review and perspectives. Bilaspur, India: Booksclinic.

Hsieh, H. F., and Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualia. Health Res. 15, 77–1288.

Hyson, CM . (2016). Relationship between destructive leadership behaviors and employee turnover. Doctoral thesis, Walden University.

Inman, KM . (2023). Biblical leadership: Combatting authoritarianism. Doctoral thesis, Liberty University, Lynchburg, Virginia.

Karli, B . (2022). Okul müdürlerinin toksik liderlik davranışına ilişkin öğretmen görüşleri [Teachers' opinions on toxic leadership behaviour of school principals]. Master’s dissertation, Istanbul Sabahattin Zaim University, Türkeyi.

Kizrak, M., and Öztürk, A. (2023). “Counterproductive aspects of teamwork” in Dark sides of organizational life: Hostility, rivalry, gossip, envy and other difficult behaviors. eds. H. C. Sözen and H. N. Basım (London: Routledge).

Klahn, B. (2023). “Perspective chapter: toxic leadership in higher education—what we know, how it is handled” in Higher education–reflections from the field. eds. L. Waller and S. K. Waller, vol. 5 (London: IntechOpen).

Klahn, B., and Male, T. (2022). Toxic leadership and academics’ work engagement in higher education: a cross-sectional study from Chile. Educ. Manag. Admin. Leadership 52, 757–773. doi: 10.1177/17411432221084474

Koçak, S., and Demirhan, G. (2023). The effects of toxic leadership on teachers and schools. Int. J. Educ. Technol. Scientific Res. 8, 1907–1948. doi: 10.35826/ijetsar.648

Kramer, M., Schmalenberg, C., and Maguire, P. (2010). Nine structures and leadership practices are essential for a magnetic (healthy) work environment. Nurs. Adm. Q. 34, 4–17. doi: 10.1097/naq.0b013e3181c95ef4

Krasikova, D. V., Green, S. G., and LeBreton, J. M. (2013). Destructive leadership: a theoretical review, integration, and future research agenda. J. Manag. 39, 1308–1338. doi: 10.1177/0149206312471388

Lakeman, R., Coutts, R., Hutchinson, M., Lee, M., Massey, D., Nasrawi, D., et al. (2022). Appearance, insults, allegations, blame and threats: an analysis of anonymous non-constructive student evaluation of teaching in Australia. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 47, 1245–1258. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2021.2012643

Lašáková, A., Remišová, A., and Kirchmayer, Z. (2016). “Key findings on unethical leadership in Slovakia” in Proceedings of the 1st international conference contemporary issues in theory and practice of management (CITPM 2016), 21–22 April. eds. M. Okręglicka, I. Gorzeń-Mitka, A. Lemańska-Majdzik, M. Sipa, and A. Skibiński (Poland: Częstochowa).

Lipman-Blumen, J . (2005). The allure of toxic leaders: why followers rarely escape their clutches. Ivey BusinessJournalJanuary/February:1–8. Available at: https://iveybusinessjournal.com/publication/the-allure-of-toxic-leaders-why-followers-rarely escape-their-clutches (accessed 15 May 2024).

Lipman-Blumen, J. (2011). Toxic leadership: a rejoinder. Representation 47, 331–342. doi: 10.1080/00344893.2011.596444

Lynch, M. (2023). The 8 toxic leadership traits. Advocate Newsletter. Available at: https://www.bing.com/search?q=Lynch+M+%282023%29+The+8+toxic+leadership+traits.+The+Advocate+Newsletter.&form=ANNTH1&refig=96A365EF59614B3885F292EB4A1CEF68&pc=U531#.

Magilvy, J. K., and Thomas, E. (2009). A first qualitative project: qualitative descriptive design for novice researchers: scientific inquiry. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 14, 298–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2009.00212.x

Makwana, N. (2019). Disaster and its impact on mental health: a narrative review. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 8, 3090–3095. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_893_19

Maran, A. D., Magnavita, N., and Garbarino, S. (2022). Identifying organizational stressors that could be a source of discomfort in police officers: a thematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:3720. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19063720

Maxey, D., and Kezar, A. (2015). Revealing opportunities and obstacles for changing non-tenure-track faculty practices: an examination of stakeholders' awareness of institutional contradictions. J. High. Educ. 86, 564–594. doi: 10.1353/jhe.2015.0022

Maximo, N., Stander, M. W., and Coxen, L. (2019). Authentic leadership and work engagement: the indirect effects of psychological safety and trust in supervisors. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 45, 1–11. doi: 10.4102/sajip.v45i0.1612

Mayring, P. (2000). Qualitative content analysis. Forum Qual. Sozialforschung [Forum: Qual. Soc. Res.] 1, 1–10. doi: 10.17169/fqs-1.2.1089

Mehta, S., and Maheshwari, G. C. (2013). Consequence of toxic leadership on employee job satisfaction and organizational commitment. J. Contemp. Manag. Res. 8, 1–23.

Menon, K., and Motala, S. (2021). Pandemic leadership in higher education: new horizons, risks and complexities. Educ. Change 25, 1–19. doi: 10.25159/1947-9417/8880

Mertens, D. M., and Ginsberg, P. E. (2009). The handbook of social research ethics. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Naicker, S. R., and Mestry, R. (2016). Leadership development: a lever for system-wide educational change. S. Afr. J. Educ. 36, 1–12. doi: 10.15700/saje.v36n4a1336

Nathaniel, A. (2019). How classic grounded theorists teach the method. Grounded Theory Review 18, 13–28.

Nathaniel, A. K. (2022). When and how to use extant literature in classic grounded theory. American J. Qual. Res. 6, 45–59. doi: 10.29333/ajqr/12441

Ofori, G. (2008). Leadership for the future construction industry: agenda for authentic leadership. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 26, 620–630. doi: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2007.09.010

Oplatka, I. (2023). Studying negative aspects in educational leadership: the benefits of qualitative methodologies. Res. Educ. Admin. Leadership 8, 549–574. doi: 10.30828/real.1330936

Oruh, E. S., Mordi, C., Dibia, C. H., and Ajonbadi, H. A. (2021). Exploring compassionate managerial leadership style in reducing employee stress level during COVID-19 crisis: the case of Nigeria. Employee Relations: Int. J. 43, 1362–1381. doi: 10.1108/ER-06-2020-0302

Padilla, A., Hogan, R., and Kaiser, R. B. (2007). The toxic triangle: destructive leaders, susceptible followers, and conducive environments. Leadersh. Q. 18, 176–194. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.03.001

Paltu, A., and Brouwers, M. (2020). Toxic leadership: effects on job satisfaction, commitment, turnover intention and organisational culture within the south African manufacturing industry. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 18:a1338. doi: 10.4102/sajhrm.v18i0.1338

Ramaditya, M., Effendi, S., and Syahrani, N. A. (2023). Does toxic leadership, employee welfare, job insecurity, and work incivility have an impact on employee innovative performance at private universities in LLDIKTI III area? Jurnal Aplikasi Bisnis dan Manajemen (JABM) 9, 830–842. doi: 10.17358/jabm.9.3.830

Ravitch, S. M., and Carl, N. M. (2019). Qualitative research: Bridging the conceptual, theoretical, and methodological. 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Schmidt, A. A. (2008). Development and validation of the toxic leadership scale. Thesis submitted to the faculty of the graduate school of the university of Maryland, college park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of master of science.

Schyns, B., and Schilling, J. (2013). How bad are the effects of bad leaders? A meta-analysis of destructive leadership and its outcomes. Leadersh. Q. 24, 138–158. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.09.001

Selvi, A. F. (2019). “Qualitative content analysis” in The Routledge handbook of research methods in applied linguistics (London: Routledge), 440–452.

Senge, P. M., and Scharmer, C. O. (2008). “Community action research: learning as a community of practitioners, consultants and researchers” in Handbook of action research: The concise. eds. P. Reason and H. Bradbury. paperback ed (London: Sage), 195–206.

Shao, W., Moffett, J. W., Quach, S., Surachartkumtonkun, J., Thaichon, P., Weaven, S. K., et al. (2022). Toward a theory of corporate apology: mechanisms, contingencies, and strategies. Eur. J. Mark. 56, 3418–3452. doi: 10.1108/EJM-02-2021-0069

Snow, N., Hickey, N., Blom, N., O’Mahony, L., and Mannix-McNamara, P. (2021). An exploration of leadership in post-primary schools: the emergence of toxic leadership. For. Soc. 11:54. doi: 10.3390/soc11020054

Tekiner, M. A., and Aydın, R. (2016). Analysis of relationship between favoritism and officer motivation: evidence from Turkish police force. Inquiry: Sarajevo J. Soc. Sci. 2, 122–123.

Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Acad. Manag. J. 43, 178–190. doi: 10.2307/1556375

Tyler, A. R. (2022). Can we still archive? Privacy and social science data archiving after the GDPR (doctoral dissertation).

Yavaş, A. (2016). Sectoral differences in the perception of toxic leadership. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 229, 267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.07.137

Keywords: toxic leadership, higher education institution, authoritarian leadership, in-group favouritism/groupthink, destructive criticism, self-centredness

Citation: Olabiyi OJ, Du Plessis M and Van Vuuren CJ (2024) Unveiling the toxic leadership culture in south African universities: authoritarian behaviour, cronyism and self-serving practices. Front. Educ. 9:1446935. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1446935

Edited by:

Mayra Urrea-Solano, University of Alicante, SpainReviewed by:

Gina L. Peyton, Nova Southeastern University, United StatesMarcina Singh, University of Johannesburg, South Africa

Copyright © 2024 Olabiyi, Du Plessis and Van Vuuren. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Olaniyi J. Olabiyi, b29sYWJpeWlAdXdjLmFjLnph

Olaniyi J. Olabiyi

Olaniyi J. Olabiyi Marieta Du Plessis

Marieta Du Plessis Carel Jansen Van Vuuren

Carel Jansen Van Vuuren