- 1School of Public Health, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, United States

- 2Department of Psychology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, United States

- 3Wellbeing Initiatives, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, United States

There is a growing trend among US universities and colleges to become Health Promoting Universities (HPUs) and adopt the Okanagan Charter. This trend is based on the aspirations of these universities and colleges to infuse health into everyday operations and improve the wellbeing of people, places and the planet. As university and colleges adopt the Okanagan Charter there is little guidance on how to think about wellbeing and address the social and planet determinants of health on a university campus. In addition, there is a need to understand the strategies of HPUs and how they differ compared to current activities of schools or programs of public health and medical centers already focused on improving health and wellness. HPUs will be a driving force for campus public health and improvements in wellbeing as additional higher education institutions move in this direction.

Introduction

US college students are not well. The Healthy Minds Study Student Survey (Healthy Minds Network, 2024), an annual national survey of college students, found that 36 percent of college students had an anxiety disorder and 41 percent had depression in the 2022–2023 academic year. For many years now, universities have been trying to help students on their campuses thrive and flourish, increasing the availability of services on campuses (Abrams, 2022; Novotney, 2014). Most of these services, including mental health treatment, are directed toward individuals, which is important for that individual, but does nothing to create conditions that prevent the need for these services at the population level. With almost three quarters of students reporting moderate or severe psychological distress (American College Health Assessment, 2021), US higher education administrators worry there aren’t enough counselors to treat the high levels of students with anxiety and depression on campus (Abrams, 2022). Additionally, Meeks et al. (2021) found nearly matching rates of severe depression, anxiety, and stress among college students, staff and faculty.

In an effort to move beyond individual wellness to a greater emphasis on systems and settings, health promotion practitioners founded a US Health Promoting Campus Network (USHPCN, 2023b). The network is a regional network of the International Health Promoting Campuses Network (IHPCN) that to date includes 282 US Institutes of Higher Education, of which 32 have adopted the Okanagan Charter (OC). Each campus develops its own strategic plan and although they all are in alignment with the Charter they vary broadly across the adopters group.

Christensen and Kennedy (2023) reviewed higher education strategies to improve wellbeing and found a strong emphasis in the literature for person-level interventions such as traditional psychotherapy, suicide prevention, courses addressing coping strategies, first year transition support, and interventions to increase belonging and connectedness. There was little evidence of policy, systems, or settings wellbeing strategies in the higher education literature. There was a lack of scientific investigation and evaluation examining the impact of changes to public policies, regulations, and laws that impact the health of college students.

The health and wellbeing of university students, staff, and faculty is shaped by factors far beyond individual medical treatments and a person-level focus. This commentary presents the OC as shifting the paradigm toward creating campus environments that support wellbeing of people, place, and planet, and away from a focus on the individual level/domains; and how the OC may be operationalized to identify a broad set of campus wellbeing determinants of health and new areas of focus and attention.

The Okanagan Charter

The Okanagan Charter (2015) is an international framework developed by experts from 42 countries (Black and Stanton, 2016) to support and sustain students, staff, and faculty while integrating health and sustainable infrastructure development into the university’s core business (Dooris, 2022, p. 155). In December 2020, the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) became the first US university to adopt the Okanagan Charter (OC) as a Health Promoting University (HPU) (Thomason, 2020). December 2024, 282 institutions have joined the US Health Promoting Campuses Network (USHPCN), of which 32 have formally adopted the Okanagan Charter (USHPCN, 2023a).

The Okanagan Charter (OC) was an outcome of the 2015 International Conference on Health Promoting Universities and Colleges (2015) held at the University of British Columbia’s Okanagan campus in Kelowna, Canada. The vision for the OC is that “Health promoting universities and colleges transform the health and sustainability of our current and future societies, strengthen communities, and contribute to the wellbeing of people, places, and the planet” (emphasis added) (OC, p.3).

As an application of the “Health in All Policies” (Green et al., 2021; Browne and Rutherfurd, 2017; Marmot and Bell, 2012) approach, the shared aspirations of the universities and colleges adopting the Charter are to “infuse health into everyday operations, business practices, and academic mandates. By doing so, health promoting universities and colleges enhance the success of our institutions; create campus cultures of compassion, wellbeing, equity and social justice; improve the health of the people who live, learn, work, play and love on our campuses; and strengthen the ecological, social, and economic sustainability of our communities and wider society” (OC, p. 3).

These shared aspirations take the broadest view of health and wellbeing, making health a priority in all aspects of daily life. This distinctly societal or cultural view of health includes ecological, economic, social justice, and sustainability factors and goes far beyond defining health and wellbeing as only the physical health of individuals or groups. In the Charter, people, places, and planet serve as broad categories of health influencers and serve to demonstrate the holistic or societal view of health and its social and environmental determinants. People, places, and planet are, therefore, all-encompassing, and health is viewed as physical health or wellness for individuals (people), health and wellbeing where people live – their socioecological and built environment (places) - as well as the health and wellbeing in the broader ecosystems of the planet itself (planet).

Health promoting university

While the use of the term “Health Promoting University” has become synonymous with the Okanagan Charter, its use long precedes the development of the charter. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) publication, Health promoting universities: concept, experience and framework for action (1998), grew out of the First International Conference on Health Promoting Universities in Lancaster, England in 1996, and the WHO round table meeting on the criteria and strategies for a new European Network of Health Promoting Universities in 1997 (WHO, 2024). Fundamental to the concept of the HPU is a “top-level commitment to embedding an understanding of and commitment to sustainable health within the organization in its entirety” (emphasis added) (Tsouros et al., 1998). As further described in the preface, the HPU operates in multiple domains, with each domain providing a pathway to health and wellbeing:

• As large institutions – building a commitment to health into their organizational culture, structures, and practices;

• As major employers - promoting employee wellbeing through operational policies;

• As creative centers of learning and research - creating, synthesizing, and applying health-related knowledge and understanding;

• As educators of future generations of decision-makers – developing an understanding of sustainable health;

• As settings for student growth and maturation - enabling healthy personal and social development; and,

• As a resource for and a partner in local, national, and global communities - advocating and mediating for healthy and sustainable public policy.

This WHO publication focusing on HPUs was the foundation for the Edmonton Charter for Health Promoting Universities and Institutions of Higher Education (2005), and now--the OC.

Defining the approach of an HPU

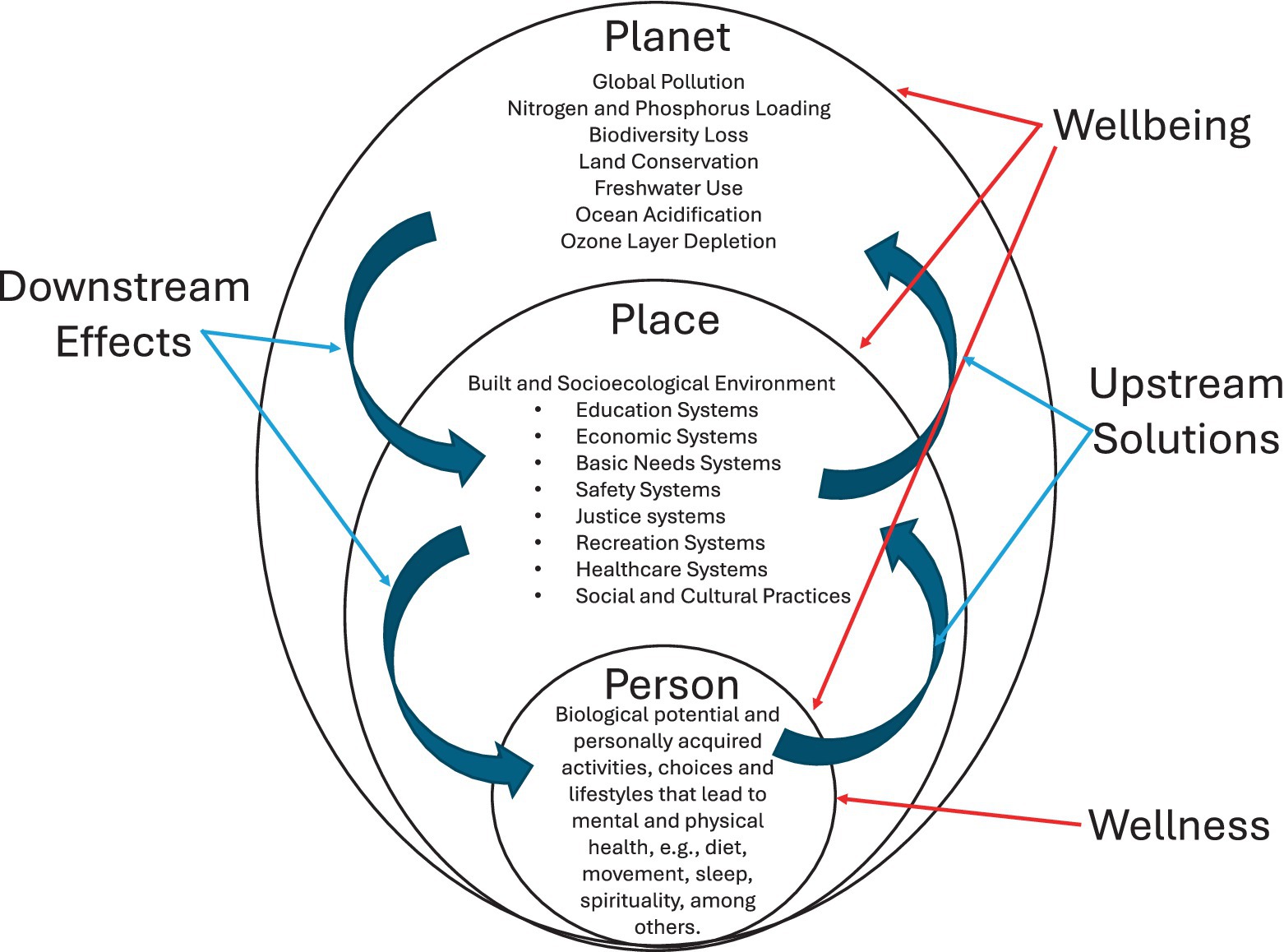

As more universities and colleges in the US adopt the OC and become HPUs, there is a need to develop common models for explaining the concepts outlined in the Okanagan Charter’s People, Places, and Planet framework, along with methods for assessing, planning, and setting wellbeing and quality of life goals. There is an interrelationship between people, places, and planet and downstream health effects and upstream health solutions conceptualized through the Charter’s wellbeing framework, which adopts an ecological model where health is determined by a dynamic and complex interaction of personal, social, and environmental factors (Hancock, 2015).

An ecological model of wellbeing on campuses and definitions

The Okanagan Charter, World Health Organization, and the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) take consistent views of what makes people healthy, the definition and scope of health, wellness, and wellbeing, and the social determinants of health (SDH). This shared viewpoint provides a common set of criteria that may be applied across diverse campus environments for assessing wellbeing, the quality of life, and for developing long-term wellbeing strategies.

Health is “a state of complete physical, social and mental wellbeing, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (WHO, 2024).” Wellness is “the active pursuit of activities, choices, and lifestyles that lead to a state of holistic health” (Global Wellness Institute, 2024). Wellness concerns the optimal health of the individual and groups, while wellbeing is a “positive state experienced by individuals and societies. Similar to health, wellbeing—according to the WHO (Health Promotion Glossary of Terms, 2021)—is a resource for daily life and is determined by social, economic, and environmental conditions that influence health outcomes and more generally determine the quality of life.” Individual health is influenced by a wide variety of pursuits typically including several dimensions of human behavior; wellbeing is a term that includes wellness or individual health, but also includes a broad set of social, environmental, and planetary determinants of health that are beyond the control of the individual alone. We cannot address human health or wellness without considering the impacts of the broader environment inclusive of the processes and systems within society and nature (Dahlgren and Whitehead, 1991).

Upstream/downstream thinking for person, places, and planet

Personal health is affected by nonmodifiable factors such as age, race, and genotype, and by modifiable factors such as lifestyle, behaviors, and choices (Erwin and Brownson, 2017). Factors in the immediate environment – SDH and the built and natural environment – also have powerful impacts on personal health as does the state of the planet (Dahlgren and Whitehead, 1991). The Dahlgren and Whitehead model—a top 50 key achievement of the past 50 years according to UK Economics and Social Science research—offers three domains that parallel Campus Determinants Model (CDM) (Dahlgren and Whitehead, 2021) but our model adds upstream solutions and downstream effects and delineates systems that impact place and planet, while also differentiating wellbeing from wellness.

The WHO reports that SDH account for between 30 and 55% of health outcomes (WHO, 2024), an estimate that comes from studies including (McGinnis and Foege, 1993; Schroeder, 2007; Braveman and Gottlieb, 2014). In addition, estimates show that contributions to population health outcomes from sectors outside health exceeds the contribution from the health sector (WHO, 2024).

An upstream and downstream metaphor, though imperfect, can be used to illustrate health, wellness, and wellbeing within a people, places, and planet context. The objective of the metaphor is to show that personal health or wellness AND an individual’s personal sense of wellbeing are influenced by a variety of factors in the social, built, and planetary health environment upstream from individuals or groups. Thus, change, evolution, and events occurring in places and planet have downstream effects on personal health and impact a general sense of personal wellbeing (see Figure 1).

Individual wellness strategies are difficult given a certain set of circumstances within the setting in which the person lives, learns, works, and plays. One example of this in higher education is the diet of college students. College students’ diets are not just shaped by personal choice or nutrition knowledge but also convenience, affordability, access, and social and cultural history and practices (Sogari et al., 2018; Kopels et al., 2024; Lee et al., 2023). Upstream approaches to improve the diets of college students seek to modify the systems and settings that impact diet beyond the personal habits of a student.

Many campuses have been deemed food desserts, particularly during evening and holiday hours (Meneely and Heckert, 2018; Vilme et al., 2020). This impacts employees and students who reside on campus but return from work after the cafeteria has closed and will likely have limited options to get a healthy meal. As university leadership examine the setting and the systems impacting student behavior and outcomes, they can modify the setting in ways that enable students to increase control over their health and its determinants (Tam et al., 2017). When healthy vending or healthier grab-and-go options are available 24 h a day at affordable prices, students can choose healthier options when the cafeteria is closed (American Osteopathic Association, 2018). Issues upstream such as the cafeteria hours, in this example, are affecting optimal personal health.

There are also a number of planetary health issues that are impacting our food and its availability (Haines, 2016). Planetary health focus areas may feel beyond the reach or scope of university administrators, but HPUs value and strive toward sustainability practices that promote planetary health—critical not just for students, staff, and faculty, but for all society members—even while their core business is not necessarily to solve complex planetary health issues. This ecological view embedded in the Okanagan Charter outlines how effective solutions and positive health outcomes often lie upstream.

Discussion

The Okanagan Charter action framework and key principles for action encourage a settings and systems approach, embedded in the core business of the university, working to address downstream effects with upstream solutions. Long-term, population-wide personal wellness solutions lie in addressing the broader concept of wellbeing – Person, Place, and Planet, and not just focusing on strategies such as personal nutrition, exercise, and stress management.

Figure 1 is an ecological model of a campus environment and the connections and influencers on wellness and wellbeing. It may be customized for any university or college campus and used for prioritization and planning. College campuses and their surrounding communities often have unique social and environmental determinants of health and wellbeing and, therefore, priorities addressed within the Charter framework may vary. Identifying the people, place, and planet determinants for any particular campus is about making decisions concerning local conditions and needs. Furthermore, the Okanagan Charter does not mandate or even specify the determinants of health to be placed under the people, places, and planet categories, but rather suggests each campus and community is different and may identify unique determinants and set distinctive priorities based on circumstances and resources. Our perspective is that applying the OC framework is a paradigm shift toward creating campus environments that support the wellbeing of people, place, and planet, and away from a focus on the individual level/domains. This shift is depicted in our Campus Determinants Model, in which wellbeing goes beyond the individual and encompasses the interconnectedness of the individual, place, and planet.

Conclusion

It is the view of the authors that the current needs of university students demand a framework that provides opportunities beyond personal development. The OC has the flexibility to serve a wide variety of higher education institutions and their specific needs over time. Operationalizing the OC results in a paradigm shift toward creating campus environments that holistically support the wellbeing of people, places, and the planet. We call for more research to be done on the OC adoption and HPU impacts.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

PG: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. RK: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. PE: Writing – review & editing. WR: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abrams, Z. (2022). Student mental health is in crisis. Campuses are rethinking their approach. Monit. Psychol. 53:60.

American College Health Assessment. (2021). Available at: https://www.acha.org/

Black, T., and Stanton, A. (2016). Final report on the development of the Okanagan Charter: An international charter for health promoting universities & colleges [R]. doi: 10.14288/1.0372504

Braveman, P., and Gottlieb, L. (2014). The social determinants of health: it’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public health reports. 129 (Suppl 2), 19–31. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291S206

Browne, G. R., &. Rutherfurd, ID, (2017). The case for ‘environment in all policies’: lessons from the ‘health in all policies’ approach in public health.” Environ. Health Perspect. 125 149–154. doi: 10.1289/EHP294

Christensen, B. K., and Kennedy, R. E. (2023). “Wellbeing in higher education” in Toward an integrated science of wellbeing. eds. E. Rieger, R. Costanza, I. Kubiszewski, and P. Dugdale (New York: Oxford University Press).

Dahlgren, G, and Whitehead, M. (1991). Policies and strategies to promote equity in health. Background document to WHO - Strategy paper for Europe Stockholm, Sweden: Institute for Futures Studies

Dahlgren, G., and Whitehead, M. (2021). The Dahlgren-Whitehead model of health determinants: 30 years on and still chasing rainbows. Public Health 199, 20–24. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.08.009

Dooris, M. (2022). Health-promoting higher education. In Handbook of Settings-Based Health Promotion. eds. S. Kokko and M Baybutt (Cham: Springer). 151–165.

Erwin, P. C., and Brownson, R. C. (2017). Scutchfield and Keck's principles of public health practice. 4th Edn. Boston: Cengage.

Global Wellness Institute. (2024). What is wellness? Available at: https://globalwellnessinstitute.org/what-is-wellness/ (Accessed May 6, 2024).

Green, L., Ashton, K., Bellis, M. A., Clemens, T., and Douglas, M. (2021). ‘Health in all policies’—a key driver for health and well-being in a post-COVID-19 pandemic world. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:9468. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18189468

Haines, A. (2016). Addressing challenges to human health in the Anthropocene epoch-an overview of the findings of the Rockefeller/lancet commission on planetary health. Public Health Rev. 37:14. doi: 10.1186/s40985-016-0029-0

Hancock, T. (2015). Population health promotion 2.0: an eco-social approach to public health in the Anthropocene. Can. J. Public Health 106, 252–255. doi: 10.17269/cjph.106.5161

Health Promotion Glossary of Terms. Geneva: World Health Organization; (2021). 44. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240038349

Healthy Minds Network (2024). Healthy minds study among colleges and universities, year 2022–2023 [Healthy Minds Student Survey]. Healthy Minds Network, University of Michigan, University of California Los Angeles, Boston University, and Wayne State University. Available at: https://healthymindsnetwork.org/research/data-for-researchers

International Conference on Health Promoting Universities and Colleges. Okanagan Charter: An international Charter for health promoting universities and colleges. (2015). https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/53926/items/1.0132754 (Accessed May 6, 2024).

Kopels, M. C., Shattuck, E. C., Rocha, J., and Roulette, C. J. (2024). Investigating the linkages between food insecurity, psychological distress, and poor sleep outcomes among U.S. college students. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 36, –e24032. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.24032

Lee, Y. M., Sozen, E., and Wen, H. (2023). A qualitative study of food choice behaviors among college students with food allergies in the U.S. Br. Food J. 125, 1732–1752. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-10-2021-1077

Marmot, M., and Bell, R. (2012). Fair society, healthy lives. Public Health 126, S4–S10. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2012.05.014

McGinnis, J. M., and Foege, W. H. (1993). Actual causes of death in the United States. JAMA, 270, 2207–2212.

Meeks, K., Peak, A. S., and Dreihaus, A. (2021). Depression, anxiety, and stress among students, faculty, and staff. J. Am. Coll. Health. 71. 1–7. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2021.1891913

Meneely, D., and Heckert, M. (2018). Conceptualizing college campuses as food deserts. American Association of Geographers 2018 Annual Meeting. Available at: https://aag.secure-abstracts.com/AAG%20Annual%20Meeting%202018/abstracts-gallery/731

Novotney, A. (2014). Students under pressure. Washington DC: American Psychological Association. Available at: https://www.apa.org/monitor/2014/09/cover-pressure (Accessed May 6, 2024).

Okanagan Charter. An international Charter for health promoting universities and colleges. (2015). Available at: https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/53926/items/1.0132754 (Accessed May 6, 2024).

Schroeder, S. A. (2007). We can do better—Improving the health of the American people. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 1221–1228.

Sogari, G., Velez-Argumedo, C., Gómez, M. I., and Mora, C. (2018). College students and eating habits: a study using an ecological model for healthy behavior. Nutrients 10:1823. doi: 10.3390/nu10121823

Tam, R., Yassa, B., Parker, H., O'Connor, H., and Allman-Farinelli, M. (2017). University students’ on-campus food purchasing behaviors, preferences, and opinions on food availability. Nutrition 37, 7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2016.07.007

Thomason, S. (2020). UAB becomes first Health Promoting University in the United States. 2020, December 15). Birmingham, Alabama: UAB News. Available at: https://www.uab.edu/news/campus/item/11756-uab-becomes-first-health-promoting-university-in-the-united-states

Tsouros, A. D., Dowding, G., Thompson, J., and Dooris, M. (1998). Health promoting universities: Concept, experience and framework for action. Target 14. Regional Office for Europe: World Health Organization. Available at: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/108095

USHPCN. (2023a). USHPCN Summit – Centering Equity While Moving Through Wellness to Wellbeing. Available at: http://ushpcn.org/events/2023-summit/ (Accessed May 6, 2023).

USHPCN. (2023b). Network. Available at: http://ushpcn.org/network/ (Accessed May 6, 2023).

Vilme, H., Paul, C. J., Duke, N. N., Campbell, S. D., Sauls, D., Muiruri, C., et al. (2020). Using geographic information systems to characterize food environments around historically black colleges and universities: Implications for nutrition interventions. J. Am. Coll. Health. 70, 818–823. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2020.1767113

WHO. (2024). Social determinants of health. Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1 (Accessed May 6, 2023).

Keywords: health promoting university, student health, Okanagan Charter, wellbeing, campus health, systems and settings approach, people, place, and planet, healthy campus

Citation: Ginter PM, Kennedy R, Erwin PC and Reed W (2024) The Okanagan Charter to improve wellbeing in higher education: shifting the paradigm. Front. Educ. 9:1443937. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1443937

Edited by:

Jeanne Grace, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South AfricaReviewed by:

Claudia Hildebrand, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, GermanyCopyright © 2024 Ginter, Kennedy, Erwin and Reed. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wendy Reed, d2VuZEB1YWIuZWR1

Peter M. Ginter1

Peter M. Ginter1 Rebecca Kennedy

Rebecca Kennedy Paul C. Erwin

Paul C. Erwin Wendy Reed

Wendy Reed