- 1Department of Education Studies, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, United States

- 2Chair of Educational Science II, University of Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany

Knowledge brokers are instrumental in improving education, including increasing equitable opportunities for all students. While many researchers have investigated the social networks between knowledge brokers and their audiences, less is known about knowledge brokers' relational ecosystems, defined as partner networks with organizations and individuals for collaboration, support, and resource exchange. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to examine the characteristics of knowledge brokers' relational ecosystems (e.g., size, strength of relationships, network closure) and how relational ecosystems support and shape knowledge creation and mobilization. This study uses egocentric social network analysis methods to analyze survey and interview data from six equity-focused and evidence-based knowledge broker organizations that create and mobilize resources to different levels of the education system, from K-12 schools to state-level policy contexts in the United States. The evidence suggests that participating knowledge brokers partnered with numerous and heterogeneous individuals and organization types, including researchers, leaders, foundations, and intermediaries. The core relational ecosystems were characterized by strong relationships, partly driven by individual team members' social networks and comprising micro-networks, and were well-connected (i.e., network closure). Furthermore, our data indicates that beyond being collaborators, partners provided infrastructure and financial resources, served as intermediaries for knowledge mobilization, provided insights into policy contexts and audiences' needs, supported knowledge brokers' capacity building, and connected knowledge brokers to people and organizations. These relationships were not one-directional, but often mutually beneficial, resulting in reciprocated relational ecosystems. Our findings suggest that it might be beneficial for knowledge brokers to strategically cultivate relational ecosystems by supporting individual team members in cultivating their social networks, adapting to evolving needs and challenges while being conscious of long-term priorities, and balancing strong ties with the (re-)engagement with new partners and different sources of information.

1 Introduction

Many schools in the United States struggle to provide high-quality education to all students, particularly schools serving under-resourced communities, resulting in opportunity gaps (Milner, 2012; Darling-Hammond, 2013). Under-resourced schools are often burdened with insufficient facilities, stringent accountability structures, and higher levels of staff churn, adding to their challenges (Darling-Hammond, 2013). However, there is potential to address complex issues such as educational inequities by bridging the persistent gap between research and practice (OECD, 2022). One promising approach to bridging research and practice is through the engagement of knowledge brokers. Knowledge brokers can support educators by learning from them about their needs and then making relevant resources accessible (Farley-Ripple et al., 2018; Rycroft-Smith, 2022). Given their additional challenges, this can be particularly useful for educators in under-resourced schools.

Knowledge brokers are increasingly influential in education, often operating outside traditional educational institutions (Haddad, 2020; Saraisky and Pizmony-Levy, 2020). Therefore, it is crucial to expand our limited understanding of their intermediary role in transforming education. External knowledge brokers are often relied upon by schools, districts, and state education agencies to help mobilize knowledge and resources into their systems to improve education and increase equitable opportunities for all students (Ainscow, 2012; Rycroft-Smith, 2022; Bélanger and Dulude, 2023). Knowledge mobilization is an exchange between researchers, policymakers, and practitioners, resulting in a relational and multidirectional process that involves collaboration and co-creation of knowledge as well as moving knowledge to where it will be most useful (Ward, 2017; MacGregor and Phipps, 2020; Lockton et al., 2022; Phipps et al., 2022), with knowledge brokers playing a critical role in this process.

Knowledge brokers are defined as individuals and organizations that transfer knowledge between entities that are not immediately connected (Weber and Yanovitzky, 2021). Knowledge refers to evidence from research, data, and practical experiences. Many researchers have investigated the relationships between knowledge brokers and their audiences and how the former mobilizes knowledge to the latter (e.g., Cooper and Shewchuk, 2015; Malin et al., 2018; van den Boom-Muilenburg et al., 2022; Caduff et al., 2023). However, despite prior research suggesting the important role of social networks (Granovetter, 1973; Lin, 2001; Carolan, 2014), less is known about knowledge brokers' relational ecosystems, defined as knowledge brokers' partner networks with organizations and individuals for collaboration, support, and resource exchange. Therefore, in this study, we emphasize and assess knowledge brokers' relational ecosystems through egocentric social network analysis (Crossley et al., 2015; Perry et al., 2018). Toward that goal, we take a social capital perspective (Bourdieu, 1986; Coleman, 1988; Lin, 2001), allowing us to shift the focus away from solely knowledge brokers to include their broader relational ecosystems and offer that knowledge mobilization is not exclusively an attribute of the knowledge brokers, but is influenced by, and distributed within a wider knowledge mobilization ecosystem. A deeper understanding of knowledge brokers' relational ecosystems will offer valuable insights into how knowledge, resources, and ideas are developed, refined, and shared, as well as who is shaping knowledge brokers' work and—indirectly—educators' and students' lived experiences. As such, this explorative study examines two research questions:

• What are the characteristics of knowledge brokers' relational ecosystems, including their (a) wider partner networks, and (b) core partner networks?

• How do knowledge brokers' networks support and shape their knowledge creation and mobilization work?

To address these research questions, we organized the remainder of this paper as follows: first, we discuss the social capital theory, which guided the data collection and analysis, before reviewing prior research on knowledge brokers, knowledge mobilization, and social networks. Next, we outline the methods and present the findings. Finally, we discuss areas to consider in improving knowledge mobilization efforts and outcomes based on these findings.

1.1 Social capital and social networks

This work is situated in the literature around social capital, defined as “resources embedded in social networks accessed and used by actors for actions” (Lin, 2001, p. 25, emphasis in original). Social capital theory suggests that actors (i.e., individuals or organizations) are situated in networks of relationships—relational ecosystems—and gain access to the resources embedded in these networks (e.g., knowledge, materials, and ideas) through these relationships (Lin, 2001).

Social networks allow us to measure social capital, as social relationships are important social capital sources (Scott, 2017). A social network is a set of actors (also called nodes) and the relationships (also called ties) among them (Wasserman and Faust, 1994). An actor's position in a social network, the network's structure, and the quantity and quality of ties determine their access to resources and capability to influence others and mobilize knowledge (Granovetter, 1973; Coleman, 1988; Gould, 1989; Burt, 1998, 2004; Lin, 2001).

The size of the network and the quality of relationships are consequential for knowledge mobilization, whereas strong and weak ties serve different purposes. For example, strong relationships (e.g., more frequently engaged) support the transfer of non-routine, timely, and complex knowledge (Brass et al., 1998; Reagans and McEvily, 2003). Conversely, weak (e.g., less frequently engaged) relationships provide access to novel ideas (Granovetter, 1973). Strong relationships are characterized by, for example, a high frequency of interactions, long-lasting relationships, high levels of trust, and multiplexity of ties (Kadushin, 2012; Carolan, 2014; Liou and Daly, 2019). Expressive or affective ties, such as friendships that are founded on care and concern for the partner's wellbeing, are high in trust and thus tend to be stronger compared to instrumental or work-oriented ties (Carolan, 2014; Casciaro, 2014). High levels of trust can also be a consequence of multiplex ties (Kadushin, 2012), whereas multiplexity is another indicator of strong ties and is defined as actors having more than one type of relationship, or organizations having multiple connection points with one another (Brass et al., 1998; Liou and Daly, 2019).

Beyond the quantity and quality of ties, a network's structure shapes the access to resources and knowledge mobilization. For example, a more interconnected network (i.e., network closure) facilitates trust, faster spread of overlapping knowledge, and innovation (Coleman, 1988; Phelps et al., 2012; Scott, 2017), whereas a less connected network provides access to diverse and non-redundant knowledge (Tortoriello et al., 2015). Network closure has also been found to be linked to increased reciprocity (i.e., relationships are reciprocated or mutual) (Daly and Finnigan, 2011; Phelps et al., 2012). Reciprocated ties tend to be more stable and equal (Carolan, 2014).

Measures of relationship quality and network structures allow us to understand the social capital embedded in knowledge brokers' relational ecosystems. Social capital theory emphasizes that understanding knowledge mobilization between knowledge brokers and their audiences is essential but insufficient and suggests the influential role of relational ecosystems in shaping and supporting knowledge mobilization efforts. Additionally, this theoretical framework is well-suited for this paper as knowledge brokers are central to knowledge mobilization networks as they, by definition, occupy the space of otherwise not immediately connected social entities (Weber and Yanovitzky, 2021).

1.2 Knowledge brokers and social networks

Knowledge brokers are central to the relational process of knowledge mobilization (Ward, 2017; Phipps et al., 2022; Rycroft-Smith, 2022). For example, educators and administrators often turn to trusted individuals and organizations who can provide resources and evidence relevant to their work (Dagenais et al., 2012; Fraser et al., 2018; Finnigan et al., 2021). As such, knowledge brokers' commitment to relationship-building activities is an integral part of their knowledge mobilization work (Yanovitzky and Weber, 2021).

It is widely recognized that individuals and organizations are part of numerous networks that provide access to social capital, including knowledge and influence (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998; Lin, 2001; Nieves and Osorio, 2013). Consequently, social network analysis has been used to explore knowledge mobilization patterns. For example, Rodway et al. (2021) used network centrality measures and tie multiplexity to show that teachers and not instructional coaches and administrators emerged as key knowledge brokers in a learning community. Other studies used social network analysis to evaluate the key players in knowledge brokering networks (Rodway, 2015; van den Boom-Muilenburg et al., 2022), identify intermediaries to influence policy and practice (Oliver, 2021), or understand educators' and schools' ties to research (Farley-Ripple and Yun, 2021). These studies demonstrate the significant impact of social networks on knowledge mobilization. Therefore, employing social network analysis is crucial for enhancing our understanding of the efforts of knowledge brokers.

While these studies solely focus on the relationships between knowledge brokers and their audiences, less is known about knowledge brokers' relational ecosystems. However, understanding these relational ecosystems is key since knowledge accessed through social networks increases one's innovation and knowledge creation capacity (Nieves and Osorio, 2013)—both integral to knowledge brokers' work (Lockton et al., 2022). This study addresses this gap in the literature by exploring the structures of knowledge brokers' relational ecosystems and how they shape and support knowledge mobilization efforts using egocentric social network analysis methods.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Participants

We purposely selected six equity-focused, evidence-based organizations that intentionally create and mobilize resources to different levels of the education system, from K-12 schools to state-level policy contexts in the United States (Lockton et al., 2022; Caduff et al., 2023). These knowledge brokers include:

• An intermediary organization working with administrators and practitioners to translate research into practice and promote successful models of educational design and decision-making.

• A teacher education and professional development organization helping practitioners improve educational design and pedagogy.

• A policy institute founded by researchers aimed at increasing educational equity through partnerships with policymakers and leaders.

• A university institute whose researchers develop research-based STEM teaching practices and create resources for educators.

• An informal STEM learning space involving a team of researchers and practitioners who share findings from their youth work with the local and broader research, policy, and practice communities.

• A foundation seeking to fund projects increasing equity in educational spaces.

These knowledge brokers shared the aim of improving education for historically underserved students (e.g., students of color, multilingual learners, socioeconomically disadvantaged students). They worked toward that goal by, for example, training teachers and leaders to disrupt inequity and transform education toward more equitable outcomes, funding projects to foster effective learning experiences for children in underserved communities, or tackling the under-representation of people of color in STEM fields by addressing barriers.

2.2 Data collection

Over 2 years, we collected data from these organizations, resulting in 55 h of interview and focus group data. For this paper, we draw on data from egocentric network surveys and interviews. Egocentric networks are networks that form around the interviewees' organizations (i.e., egos) and include other individuals and organizations (i.e., alters) with whom the egos have a relationship (i.e., tie) (Crossley et al., 2015).

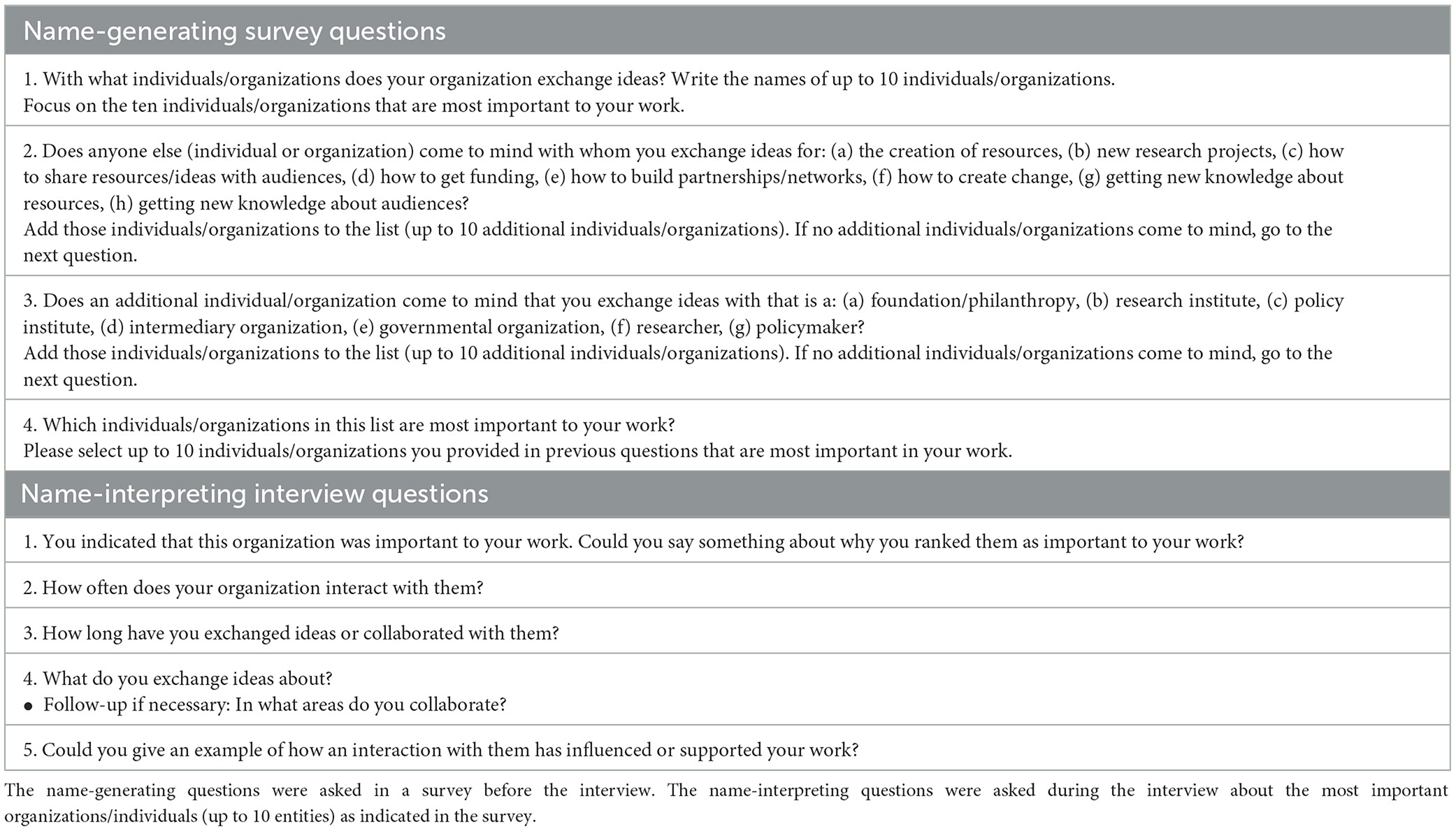

First, we conducted egocentric social network surveys with these organizations, asking them with whom they collaborated and exchanged resources (e.g., ideas, knowledge, practices). To check if the participants included everyone from their partner networks, they were asked various follow-up questions (see Table 1 for survey questions). After finalizing a list of all their partners, they were asked to select up to ten that were most important to their work. Identifying alters in this way is referred to as a name-generator survey (Perry et al., 2018).

Second, we conducted interviews with questions often referred to as name interpreters, focused on characterizing the relationships these knowledge brokers had with their top ten partners (i.e., alters), or their core relational ecosystems (Perry et al., 2018). These interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim (Merriam and Tisdell, 2016). Name-interpreting questions included the quality of the participants' relationships with the partners they listed as most important, including the strength of the relationships and ways in which the partners may have supported and influenced their work (see Table 1 for interview questions). While we asked participants about their ten most important partners, some still provided the names of more than ten organizations.

2.3 Data analysis

2.3.1 Survey data

Before analyzing the survey data, we removed all incomplete surveys. For some organizations, several members filled out the survey, which we combined for a comprehensive dataset per organization, resulting in six complete surveys. We removed all duplicates before further analysis.

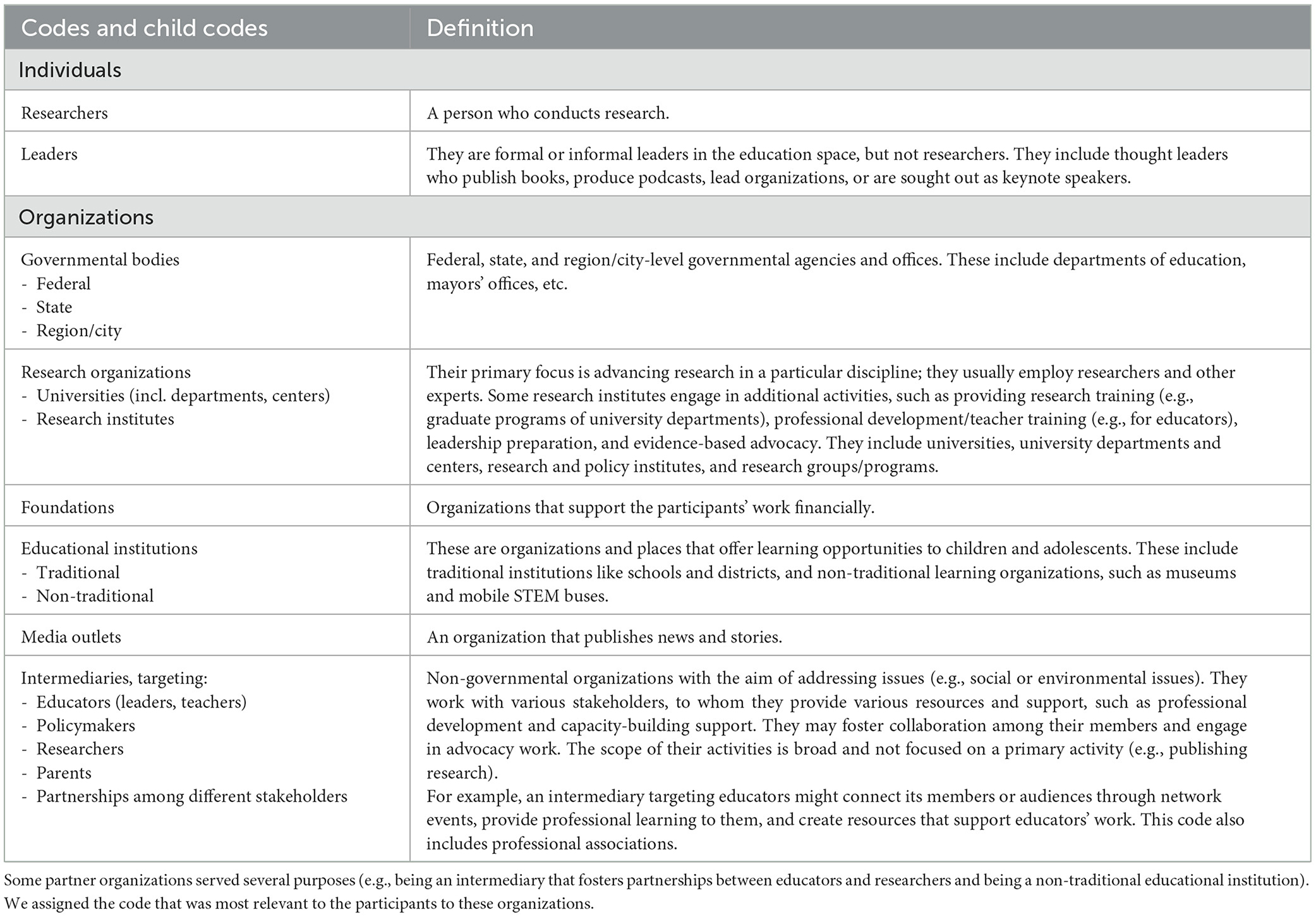

To analyze the survey data, we determined the type of organization and role of individuals through an inductively developed codebook (Table 2). Two research team members co-developed this codebook and coded all alters' organization types. During this process, they both noted questions, discussed discrepancies, and adjusted the codebook when necessary until they agreed on the codes and definitions (Miles et al., 2014; Merriam and Tisdell, 2016). Codes for individuals included (a) researchers, and (b) leaders. Codes for organizations included (c) governmental bodies, differentiated by federal, state, and region/city-level; (d) research organizations, including universities and research institutes; (e) foundations; (f) educational institutions, including traditional and non-traditional; (g) media outlets, and (h) intermediaries that we further differentiated based on their target audiences.

To answer research question 1a about the characteristics of wider relational ecosystems, we tabulated the organization type composition and size of the six egos' relational ecosystems and analyzed heterogeneity within them and ego-alter similarity (Bernardi et al., 2014; Perry et al., 2018).

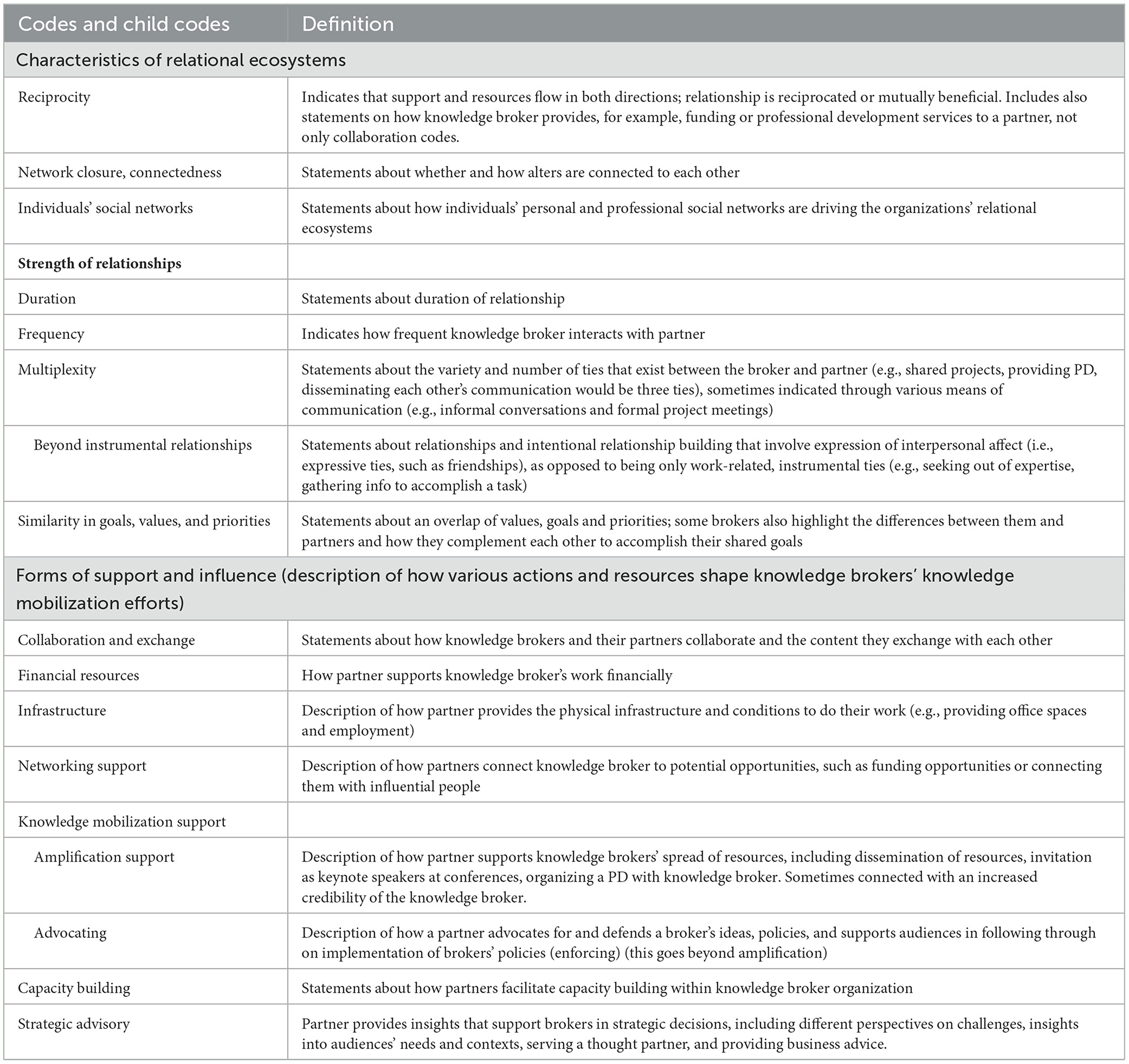

2.3.2 Interview data

To analyze the egocentric social network data of the topmost important partners, we co-developed a codebook with a set of a priori codes based on the theoretical framework, research questions, and codes that emerged progressively during the analysis process (see Table 3; Merriam and Tisdell, 2016). Using MAXQDA and following a similar process as described for the survey analysis, two research team members both coded all transcripts, noted questions, discussed discrepancies, and adjusted the codebook when necessary until they agreed on the codes and definitions (Miles et al., 2014; Merriam and Tisdell, 2016).

To answer research question 1b, we examined the egocentric networks' structures, including tie strength, organization types of their core partner networks, network closure (i.e., whether alters were connected with each other), and how the organizations' relational ecosystems were driven by individual members' professional and personal social networks (see Table 3). Analyzing the characteristics of the relational ecosystems, we coded for network closure, reciprocity, and the strength of these relationships, given the importance of network structure and strong relationships for the mobilization of complex and novel knowledge (Granovetter, 1973; Coleman, 1988; Reagans and McEvily, 2003; Scott, 2017). We measured the strength of relationships through the length of the relationships, frequency of interactions, multiplexity or variety of ties (e.g., shared projects, providing PD to the partners, reading and disseminating each other's communications), and overlap of values and goals (Bernardi et al., 2014; Perry et al., 2018).

To answer the second research question, we coded the interview responses indicating why and in what ways they considered a partner as important to their work (see Table 3). To improve the accuracy and credibility of the findings, we conducted member checks with all participants (Merriam and Tisdell, 2016). These member check meetings not only confirmed initial findings but also added more nuance and complexity.

3 Findings

3.1 Characteristics of partner networks

To answer the first research question about the characteristics of knowledge brokers' relational ecosystems, we first analyzed the survey responses to understand the wider relational ecosystems, including all partners, before focusing on the knowledge brokers' core relational ecosystems.

3.1.1 The characteristics of the wider relational ecosystem

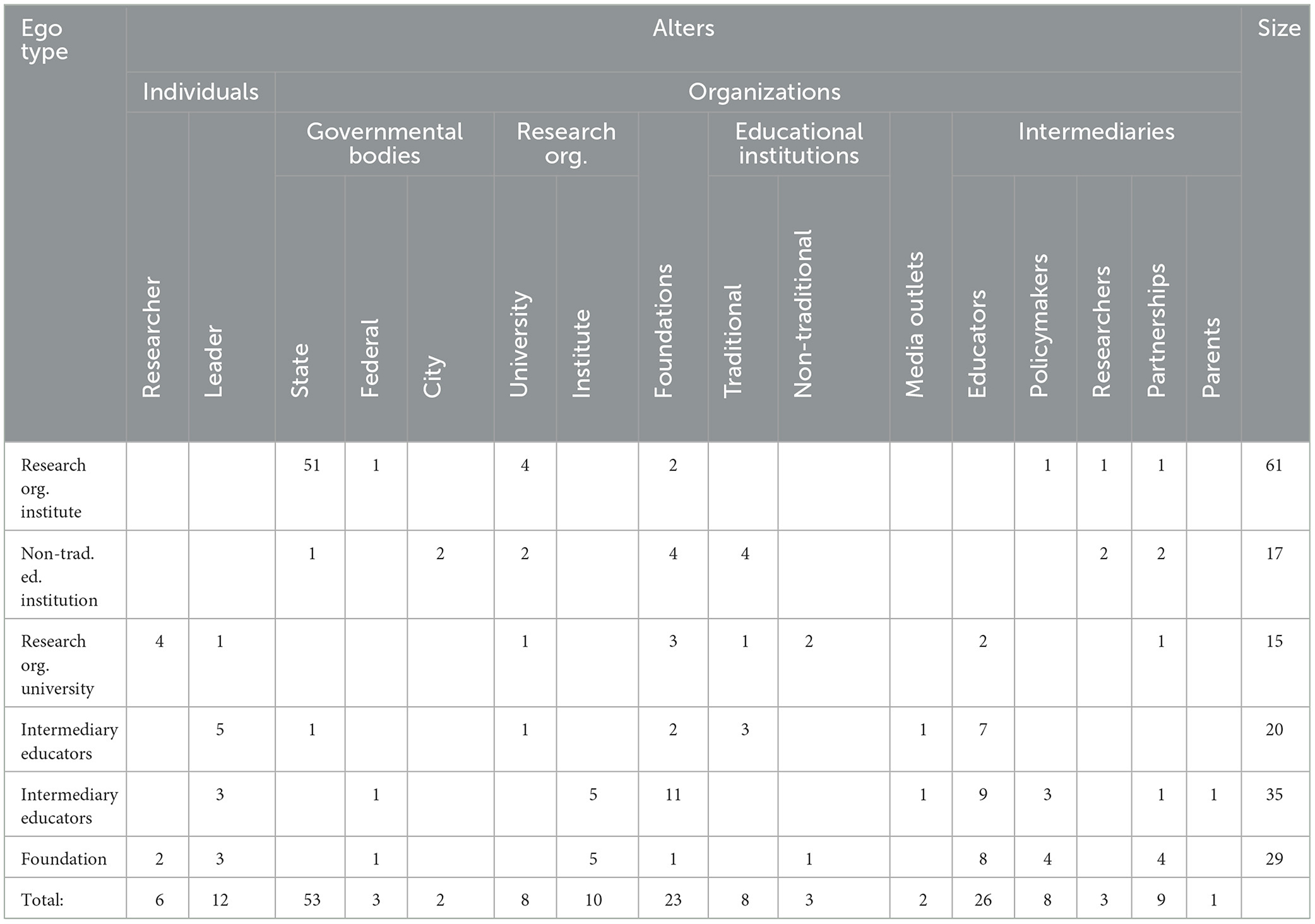

The size of the wider relational ecosystems ranged from 15 to 61 partner organizations/individuals whom knowledge brokers perceived as influential and supportive of their work (see Table 4). Of these partners in the wider relational ecosystem, knowledge brokers considered between 3 and 13 very important.

The wider relational ecosystems were diverse in terms of partner organization type and included foundations, governmental agencies at the city, state, and federal level (e.g., departments of education), research organizations (universities, university departments, and policy institutes), educational institutions, media outlets, intermediaries targeting diverse stakeholders (e.g., educators, policymakers, parents), and individuals with influence and expertise in the knowledge brokers' spaces (researchers, leaders). Organizations were named more frequently than individual researchers and leaders.

Each participant cultivated a heterogeneous relational ecosystem, comprising various organization types (e.g., foundations, intermediaries, government) and individuals with different roles. Some participants predominantly partnered with one specific organization type, indicating a less heterogeneous relational ecosystem. For example, an intermediary organization named 11 foundations as part of their relational ecosystem (Table 4), while the foundation collaborated with eight intermediaries focusing on educators. Moreover, some brokers did not specify any partners of the same organization type, indicating no ego-alter similarity. For example, the research institute did not list any researchers or other research institutes as network partners, and intermediaries targeting researchers were only mentioned once. Conversely, the relational ecosystems of the two intermediaries targeting educators provided evidence for ego-alter similarity and included other intermediaries focused on educators.

In summary, these findings indicate that knowledge brokers had ties with a variety of heterogeneous organization types and individuals, comprising different parts of the education system and beyond. They underscore access to partners offering complementary resources and services tailored to knowledge brokers' needs and objectives. As such, these wider relational ecosystems set the stage for the entrance of novel and unique knowledge into the system (Granovetter, 1973).

3.1.2 The characteristics of the core relational ecosystems

As aforementioned, knowledge brokers named between three and 13 partners as being most important, which we consider as their core relational ecosystem. When describing the relational ecosystems among the most important partners, three characteristics stood out: (a) the relationships tended to be strong based on the duration of relationship, frequency of interaction, variety of ties (including affective/expressive and instrumental ties), as well as the similarity in goals, values, and priorities, (b) the relational ecosystems were driven by individuals' social networks, and (c) the relational ecosystems were well-connected beyond the relationship with the knowledge brokers (i.e., network closure). In the following paragraphs, we describe these characteristics more in-depth.

3.1.2.1 Strength of relationships

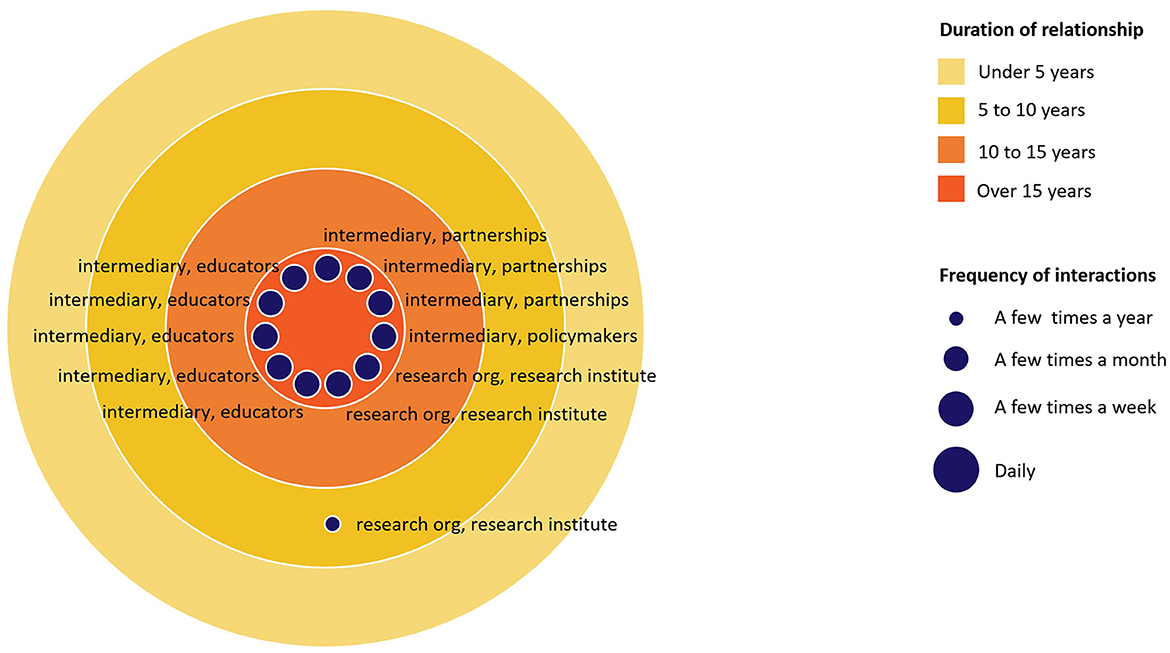

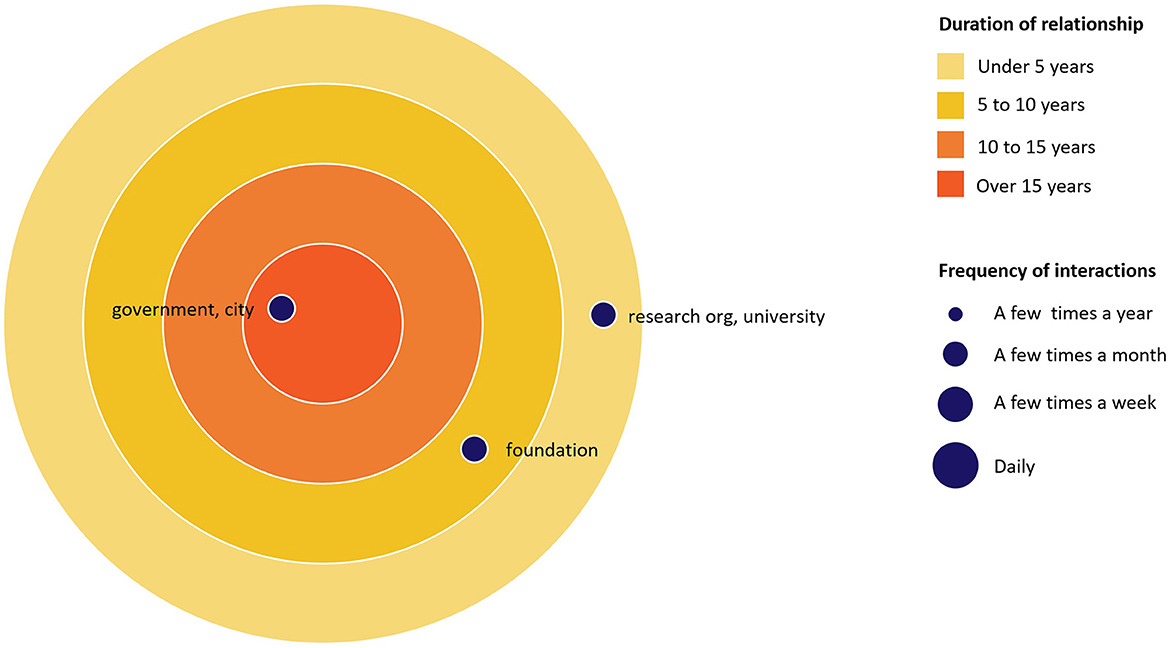

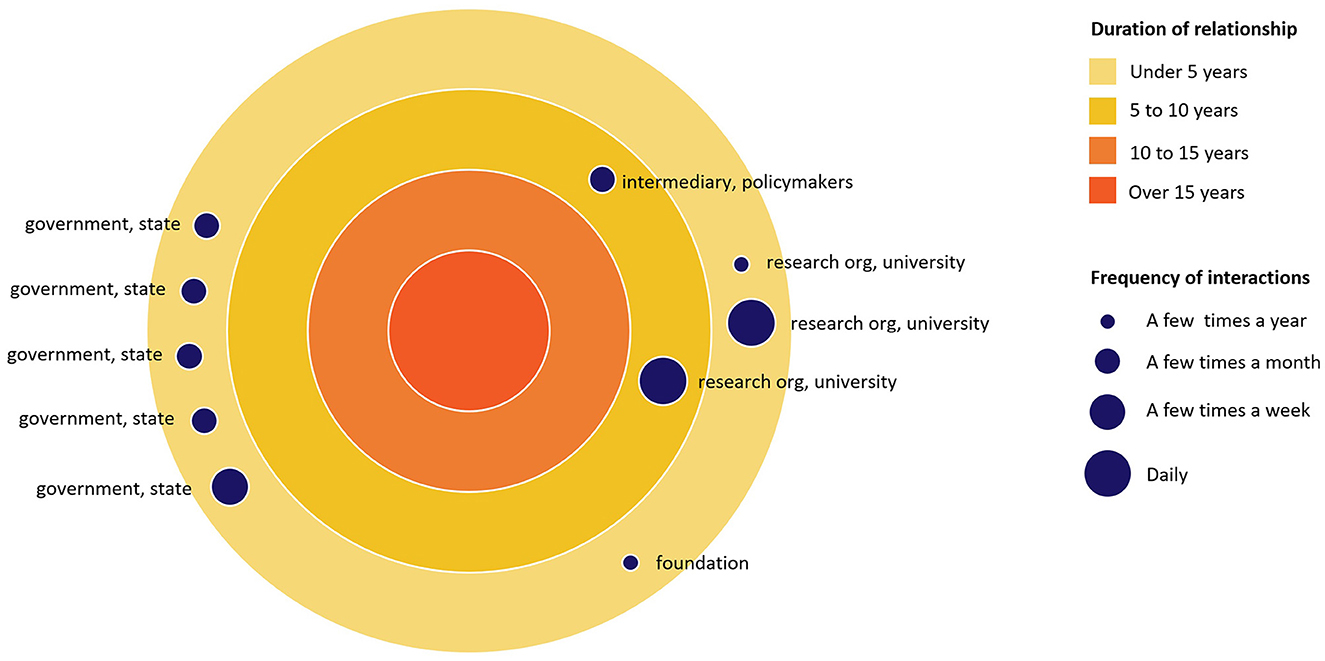

The relationships between the knowledge brokers and the individuals/organizations in their relational ecosystems were described as strong based on the duration of the relationship, frequency of interactions, variety of ties (including affective/expressive and instrumental ties), as well as the similarity in goals, values, and priorities. The next few paragraphs will discuss these indicators for strong ties in more detail. While some partnerships were described as strong for all indicators, other partnerships were considered strong on only one or two. Figures 1–3 show exemplary partner networks and the strength of their relationships measured as the duration of relationships and the frequency of interactions.

Figure 1. Topmost important partners of a knowledge broker, including duration of relationship and frequency of interactions. Besides the duration of relationships and frequency of interactions, the figure does not display additional dimensions of tie strength (i.e., multiplexity, similarity). Also, the ties among alters are not included, and the network closure is not shown.

Figure 2. Same as Figure 1 but for another knowledge broker.

Figure 3. Same as Figure 1 but for another knowledge broker.

3.1.2.1.1 Duration of relationships

All participating knowledge brokers drew on long-standing relationships with many partners. The duration of these supporting relationships was described as, for example, “for years, … for decades,” “it's been around for 17 years,” and “six years or more.” The interviews suggest that these relationships had grown and evolved over the years, often going back to the beginnings of the knowledge broker organization or even preceding it. Participants described that these partnerships existed “since the very beginning,” “since before [the organization] existed,” or for “almost [their] entire career.” However, some of the most important partnerships were newer and had existed for < 5 years, such as “the range of two years” and “about three years.” These statements indicate that the importance of a partnership was not determined solely by the duration of the relationship.

3.1.2.1.2 Frequency of Interactions

The knowledge brokers frequently exchanged ideas with and were supported by many of their partners, sometimes “almost daily” or “once a month.” The frequency of interactions was described as variable over time, with “sort of ebbs and flows.” For example, one knowledge broker interacted with one partner “four days a week or so... sometimes more than that,” indicating variability over time. However, the frequency of interactions varied between partners. One participant stated that they interacted “once every other week at least” with one partner but only “once a month,” “every other month,” and “four times a year” with other partners. This finding suggests that, similar to the duration of relationships, high frequency was only one indicator among several for important partnerships.

3.1.2.1.3 Multiplexity

Knowledge brokers usually had “multiple types of relationships and connections” to individual partners. As such, knowledge brokers interacted with these entities in “a couple of ways.” One knowledge broker summarized the multiplexity of their relationship with one partner as “it's pretty enmeshed” as they interacted with this organization “in multiple ways in multiple settings.”

The relational ecosystems were informed by formal and informal, as well as affective and instrumental relationships. For example, one participant explained they interacted with their partners formally via “email, and … at big national conferences.” Other formal interactions entailed meetings with “the program officer” or “portfolio manager,” being on the partner organization's advisory board, “compliance visits,” working on projects together, or even being employed by both organizations. These interactions and relationships could be described as “more formal” and instrumental for the knowledge brokers' work.

Other relationships were “more informal” and affective, including “a number of good, like collegial connections.” One participant mentioned that a colleague “is friends with some program officers” of the partner organization. Also, some professional relationships have developed into “personal connections,” indicating that some of these relationships included affective ties, going beyond instrumental work relationships. In sum, many knowledge brokers maintained their relationships through various communication channels and multiple ties, indicating multiplex partnerships that went beyond formal and instrumental relationships to include informal interactions and affective relationships.

3.1.2.1.4 Similarity in goals, values, and priorities

Finally, knowledge brokers often described an overlap with their partners' goals, values, and priorities. Partners in the relational ecosystem were described as “like-minded,” “trying to accomplish similar goals,” and “mission-aligned in many ways.” Some partners' work was described as “so overlapping” with the knowledge brokers' work, and they had “some goals in common,” resulting in knowledge brokers and their partners “do[ing] some parallel work.” Another characterized the partner's research as “adjacent to a lot of what we do.” In addition to the overlap of goals and priorities, similarities in approaches were mentioned frequently. For example, one participant described the methodology of a partner as “a different spin on the same thing.” In contrast, one participant mentioned that they achieve “similar outcomes” and “similar impact” as their partners, although they're “going with different methods.”

In sum, the results suggest that core relational ecosystems are often characterized by strong ties between knowledge brokers and partners. The strength of these relationships is demonstrated through their duration, high frequency of interactions, variety of ties, and the pursuit of common goals. The findings also indicate that these knowledge mobilization ecosystems go beyond formal relationships and include various informal and personal exchanges. These strong relationships support the conditions for meaningful partnerships and mutual support to improve knowledge mobilization, as well as suggest an extensive exchange of knowledge, ideas, and support between the knowledge brokers and their partners. However, having many strong connections potentially results in the replication of existing knowledge and structures, and constrains the flow of new and alternative ideas despite having a variety of heterogeneous relationships.

3.1.2.2 Individuals' social networks driving organizations' relational ecosystems

Knowledge brokers' organizational relational ecosystems were frequently driven by individual members' personal and professional social networks, which went beyond the aforementioned friendships and affective relationships. Participants mentioned that their colleagues “might have a different answer” when discussing who shaped their work or that the list of partners they provided was “skewed” based on their perspectives. Other participants emphasized the “caveat” that if we asked someone else in their organization, they could “guarantee … this list [would] be different” or that “a different person … would have just put in different organizations, people's names, etc.” There was also some counter evidence for relational ecosystems being driven by individuals, and some highlighted that they were “hesitant to define some of those [relationships] as overly personal,” given that they associated some of these relationships more with a partner organization than their individual members. Still, the evidence suggested that these social networks were informed by individual members' roles and foci within the organization, and their past employment and education.

Interviewees' roles in their organization shaped who they perceived as important to their knowledge mobilization work. One participant explained they were “answering … more from a research and evaluation perspective than a program perspective.” Another participant mentioned that they were thinking about organizations that were “important to … the communications network or … other communications folks.” Participants' professional social networks were shaped by their focus, such as leadership, afterschool programming, or STEM education: “In our three areas of work, we have different organizations that are important to us.” Other participants described “micro-networks … working toward the same larger goal” or team members focusing on “different segments,” such as “system leaders, … school leaders, or… policy-related folks.” Each micro-network and segment was related to the professional networks of the team members responsible for those. Collectively, these micro-networks made up the organizations' relational ecosystems.

Furthermore, individuals built and maintained their personal and professional social networks over the years, sometimes even prior to working with the knowledge broker organization. For instance, one organization's relational ecosystem was “heavily driven by the relationships” of one senior person who had “built [those] over the years.” These processes resulted in teams being “a collection of professionals who do have a variety of … strong relationships.” As a consequence of relational ecosystems being driven by individuals' social networks, relational ecosystems were also portrayed as dynamic, with employee turnover resulting in shifts. One individual described how “the person who did [her] role before [her]” had other priorities regarding “media relations,” affecting who would have been named as essential partners.

To strengthen their organization's relational ecosystem, some organizations purposefully employed individuals given their prior relationships. Their goal was to leverage a team member's strong relationships for their work. One knowledge broker explained that they “hired people” from one of their partners “to cement that connected relationship.” Another participant described how many of their team members were “coming into those roles with a level of credibility, relationships, and influence around a particular segment of the ecosystem.” This was one reason for “why they were hired … and are bringing a lot of value” to their work and role.

In brief, these results indicate that while there are strong relationships among knowledge broker organizations and their partners, some of these relationships were built on individuals' personal and professional social networks. As such, relational ecosystems could be described as dependent on individuals remaining a part of their organization and potentially dynamic rather than stable.

3.1.2.3 Network closure

While this study set out to examine the knowledge brokers' relationships, interviewees also described how their partners were connected to each other: “They're connected beyond our world,” and “these folks are interacting with each other with or without us.” These collaborations were often described as organically developing: “If they're working with one of these folks, they're probably going to start getting connected to the others fairly quickly.” Some of the knowledge brokers' domains were small, with not many organizations working in the same space, which facilitated relationship building: “There are a small number of organizations really doing this kind of work that I do think people have real genuine relationships across organizations as individuals and then also organization to organization collectively.” As a result, knowledge brokers' relational ecosystems were often well-connected with “an overlap of the network between” the knowledge brokers and their partners' “orbits.”

While some knowledge brokers' “hope [was] that people are like connecting organically, like not just through” them, others' mission was more proactive, centered around “creating a really strong community.” One knowledge broker described their work as “building a network, not a wheel,” and that they were “conscious … to not have [their organization] as the central hub,” but instead them being “just one of the nodes in the network.” By bringing their partners together, the knowledge brokers actively contributed to the well-connectedness of partners. Among other things, knowledge brokers organized an “annual meeting just with these partners” to “bring them all together,” or to create a “network of schools … facilitating the teaching and learning” for better student outcomes. Others leveraged conferences to host their “own community gatherings” and create a “place to engage with [their] own community members,” while again others ran a research practice partnership to increase equity.

In sum, knowledge brokers were part of well-connected relational ecosystems while also playing a crucial role in community building. This dedication to fostering a strong, interconnected community underscores the importance of knowledge brokers' work. The core relational ecosystems' strong relationships and connectedness created conditions for collaboration, support, and mutual influence in knowledge creation and mobilization.

3.2 Partners' influence on and support for knowledge creation and mobilization

To address the second research question, this section presents evidence from the interviews, illustrating how the relational ecosystems supported and shaped knowledge brokers' knowledge creation and mobilization. The participants described several reasons why these partners were essential to their work. Their partners supported and shaped their knowledge creation and mobilization by (a) being collaborators, (b) providing infrastructure and financial resources, (c) serving as intermediaries for the knowledge mobilization and increasing knowledge brokers' reach, (d) giving insights into policy contexts and their audiences' needs, (e) supporting knowledge brokers' capacity building, and (f) connecting knowledge brokers to people and organizations. Frequently, these reasons for the partners' importance were interrelated, and partners were meaningful in multiple overlapping ways. The following paragraphs describe these various forms of support.

3.2.1 Collaboration and exchange

Knowledge brokers collaborated and exchanged resources and ideas with members of their relational ecosystems. Many participants reported that they “[were] collaborating” with their partners or had “some projects with them.” Some described the collaboration in broad terms as “joint work” or that they “work[ed] really closely with [the partner],” whereas others reported collaborations related to specific events, such as “a webinar” or “a joint event” to bring educators together and share ideas, and products. One knowledge broker described working with their partners to develop evidence-based resources that “can be helpful to solve problems.” Other product collaborations included releasing “a paper together,” collaborating “to write a proposal,” and “jointly submit[ting] submissions for conferences.” These collaborations were not always public but “some sort of behind-the-scenes collaboration.”

Additionally, all participants exchanged resources, ideas, and information with all their partners. Knowledge brokers described such exchanges as “a lot of sharing of ideas” and “like shop talk.” As one participant put it: “So they share information about their state context and where their work is. And then, I share sort of information about policy-related issues.” Other knowledge brokers and their partners “compare[d] and contrast[ed]” their processes to see if they could “improve each other's” efforts. While some partners wanted to be in the know about knowledge brokers' work (e.g., “She wants to know what's going on, … kind of, we report on.”), other knowledge brokers sought their partners for specific information and “go to [the partner], and they'll share that.” The content of exchanges included “really interesting literature,” “curriculum, exemplar projects, interview content, etc.,” and evolved around research: “We're really communicating with them mostly around the research.” Knowledge brokers valued these insightful exchanges with their partners as contributing to their personal growth. One participant said, “I'm really able to have kind of professional learning exchanges.” In sum, these interviews indicate that knowledge brokers and their partners had routinized access to the other party's ideas, knowledge, and resources. Knowledge brokers highlighted in the interviews the importance and impact of these collaborations and exchanges for their knowledge creation and mobilization efforts.

3.2.2 Infrastructure and financial resources

Knowledge brokers' relational ecosystem provided them with the infrastructure and resources for knowledge creation and mobilization. While some knowledge brokers described their relational ecosystem as “a supportive, critical piece of infrastructure,” others explained that partners provided “infrastructure,” including “HR and IT and office space and access to colleagues.”

All knowledge brokers in the study acknowledged the crucial role of partners, particularly foundations, in providing financial support. Some partners were among knowledge brokers' “earliest funders” or “have been in their funding stream for different projects for a while now,” indicating consistent and sustainable financial support. In some cases, the knowledge broker organization was “kind of a main institution that [partners] fund,” while in others, partners funded specific projects or programs: “We get funding from them for one of our largest teacher professional development programs.” In brief, the relational ecosystem of knowledge brokers facilitated knowledge creation and mobilization by providing both infrastructure, such as HR and IT resources, and financial backing, often spanning multiple years.

3.2.3 Knowledge mobilization support

Relational ecosystems also supported knowledge brokers' knowledge mobilization efforts by providing opportunities to disseminate resources, amplifying their resources, sometimes even advocating for their causes, and consequently bolstering knowledge brokers' credibility. Through the relational ecosystems, knowledge brokers' work got “a lot of attention,” and people took “it seriously in the field.” One participant described that “being able to collaborate with the [partner]” not only increased the “power of spread” but also gave their organization “more credibility.” In other words, knowledge brokers' reach widened through their relational ecosystems.

Some partners provided opportunities or “platforms” for knowledge brokers to disseminate their ideas and widen their reach, such as sharing “best practices” at a “webinar” and “speak[ing] on a blog.” Partner organizations also invited knowledge brokers to their “conference,” which knowledge brokers considered “useful for pretty much any kind of connection and sharing of ideas,” or even invited them as a “speaker” for a “keynote.” Such events provided knowledge brokers with a “platform” to share ideas with their target audiences.

Furthermore, partners amplified knowledge brokers' resources, ideas, and findings. For example, partners would “retweet” research and best practices “or put it in their newsletter,” and as such, they “elevate[d] things” and “advertise[d]” knowledge brokers' resources. In doing so, partners with an extensive network and reach were particularly beneficial for mobilizing resources, including people who were “very visible” and “people like listen to hear what [they] were going to say,” or partners with “a network of like 60,000 alumni who get a newsletter and very large following on social media.” Consequently, some partners were “key to every part of [brokers'] communication strategy.” One participant described their organization could not “get to all of the principals … or all the students in the country …, but these associations, they have national conferences, they have newsletters, they have active social feeds.” In other words, by partnering with these partners, knowledge brokers could leverage their communication channels and increase their reach.

While relational ecosystems provided opportunities to disseminate and platforms to amplify, some partners went further, advocated for knowledge brokers' causes, and defended the knowledge broker's ideas by “being out there and being that supporter.” Knowledge brokers also described how their partners “started, …, getting more vocal about what we know from research about” equity in education, “and they're doing … an even bigger job getting the word out.” In sum, relational ecosystems bolstered knowledge brokers' efforts by providing platforms for dissemination and amplifying their resources, widening their reach and credibility. Partners not only facilitated dissemination through, for example, webinars, conferences, and social media, but also advocated for brokers' causes.

3.2.4 Strategic advisory

Partners served as critical strategic advisors for knowledge brokers by providing insights into policy contexts and the needs of their fields and audiences. Knowledge brokers were not passive recipients of their partners' expertise but actively and iteratively leveraged these relationships to enhance their knowledge creation and mobilization. They sought out their partners' advice, “reach[ed] out when [they] need[ed] advice,” “vet[ted] ideas with them,” and used their relationships as “a gut check on [their] work.” The “transparent, helpful feedback” knowledge brokers received from their partners was instrumental in their understanding of “pressing equity issues” and subsequently adjusting their strategies and materials. Knowledge brokers in this study strategically made “sure [they had] people in this space who [could] be responsive to the questions that arise” but also “pushed [them] with questions.” Consequently, several participants described how they had “a lot of rich spaces” that “help[ed] push [their] thinking even further,” demonstrating the active role of partners in shaping knowledge brokers' knowledge creation and mobilization.

Some of the knowledge brokers' partners were influential and leading in the education space, making their input even more relevant. By listening to their pioneering partners, knowledge brokers got “a sense of what's bubbling up, what they consider important, what they feel is missing.” For instance, one knowledge broker explained that their national funding agency partner served “like a proxy for the policy context around science, teaching, and learning.” This knowledge broker read the national agency's official communications and used these as a “signal about what people [were] talking about in terms of teaching and learning and science.” The same knowledge broker looked at other influential, more local organizations they perceived as “important shaper[s] of policy,” which is why they tried “to be responsive to them.” Others highlighted how their partners gave them “an idea in different parts of the country, culturally, … how people are approaching … ideas around education, and how children learn … and the politics of it.” Finally, one knowledge broker collaborated with their partner “to understand state-level issues related to [equity-relevant] policy and practice” to then “identify gaps or areas where evidence-based resources can be helpful to solve problems.” Knowledge brokers not only sought out their partners to get a better sense of the landscape but also to receive feedback on specific resources. For example, knowledge brokers sought out their partners to have “frank conversations” about whether a resource is “resonating” or get a thought leader “to read [anything] before it gets published.” In brief, the partners' insights guided the knowledge brokers in using their limited resources and time to make a meaningful contribution.

While some of these advisory relationships between knowledge brokers and their partners developed organically, others were formally implemented. This was especially true when the partner was a foundation that funded knowledge brokers' projects. For example, one funded project “include[ed] an advisory board that will bring together … research and state leader experts to advise [their] continued work.” This structured approach to advisory relationships underscores the role of partners in guiding knowledge creation and mobilization.

3.2.5 Capacity building

Partners, as integral parts of the relational ecosystems, actively supported capacity building within the knowledge broker organizations. They shared valuable insights on how to “improve processes,” “methods to achieving impact,” or how to achieve “business health.” Knowledge transfer also included “some really interesting literature,” that were relevant to their knowledge creation and mobilization.

Other partners provided professional development opportunities—sometimes more informal “professional learning exchanges,” and other times more formal: “They do webinars or Zoom things … or meetings at their offices… so I can get professional development.” Some of these professional learning experiences went beyond mere capacity building but had a lasting impact. For example, one participant described how one of their partners “did the earliest professional learning” he participated in at their intermediary organization. During this professional development, they realized that their organization would “be doing the same thing [as their partner] with slightly different vocabulary.”

In sum, partners facilitated capacity building within knowledge broker organizations through knowledge transfer and process improvement. Additionally, they offered professional development opportunities, ranging from informal exchanges to structured webinars and training, which not only enhanced skills but also contributed to long-lasting changes.

3.2.6 Networking support and connecting to opportunities

Knowledge brokers' relational ecosystems connected them to other organizations and people, supporting them in further expanding their networks and opportunities. Participants described how partners were “connecting [them] to people” and “potentially serving as a connector.” For example, partners organized convenings “that bring folks together across projects” and brought knowledge brokers together with other experts. Knowledge brokers who led a research practice partnership also described how partners “brought in a colleague … into [their] partnership,” contributing to the continued expansion of their network. Some foundations even funded and supported networks to improve equity in education, deliberately strengthening and widening knowledge brokers' relational ecosystems. One participant summarized these processes as “relationships leading to more relationships.”

By connecting knowledge brokers to people and organizations, partners also created new opportunities for them. For example, one participant described how their partner organization had “a policy arm, so they've kind of connected [them] with some opportunities to influence policy.” Other knowledge brokers received support in the “recruitment” of students for their mentorship programs, or partners were helpful in understanding where and how financial support could be gained. Again, another knowledge broker had “been connected to” a “lab school” through their partner. In brief, participants described how their relational ecosystems supported them in expanding their networks, and consequently creating and leveraging new opportunities for their work.

Answering the second research question, the findings above can be summarized as knowledge brokers benefitting from and their work being shaped in various ways through their relational ecosystems, including having meaningful collaborations and exchanges, receiving financial resources, widening knowledge brokers' dissemination reach, receiving strategic advice, capacity building, and being connected to even more people and opportunities. Taken together with the evidence for strong relationships, these ways of support and exchange of ideas indicate that the knowledge brokers experienced high levels of trust (i.e., strong ties) with their partners, which is a precondition for being thought partners and seeking advice.

3.3 Relational ecosystems were comprised of reciprocal relationships

The previous section illuminated the diverse forms of support that knowledge brokers derived from relational ecosystems. However, these relationships were not one-directional, nor did they solely benefit the participating knowledge brokers. Instead, the relationships between knowledge brokers and their partners were often mutually beneficial, with support and influence flowing in both directions. In other words, knowledge brokers not only received support but also provided support to their partners, resulting in “mutually beneficial relationship[s],” which in turn, resulted in reciprocated relational ecosystems.

For several knowledge brokers, mutually beneficial relationships were at the core of their work of creating change. For example, one knowledge broker underscored that their work involved research practice partnerships, with the aim of creating a space “meeting the needs and supporting all of the folks who are partners within it.” Another participant described their relationships with partners as “balanced,” with both parties “helping” each other. Knowledge brokers stressed that they did “not need to be the expert of all things,” and that “liberal sharing, borrowing, and building off of each other” was necessary for “true systemic … and large-scale change.” Another participant expressed that “people at [their organization] would be probably upset if they felt that their relationships were … one-directional. I don't know anything other than reciprocal.”

Just as knowledge brokers received various forms of support from their partners, they also provided support that served “different purposes.” Some of these mutually beneficial relationships were characterized by the partners “generally … exchanging ideas both ways,” as previously described. Other forms of support were part of the knowledge brokers' mission, such as the foundation funding research projects. Additionally, knowledge brokers “donated [their] time to help” their partners, including providing professional development, giving keynotes at conferences, sharing research results, advertising the partners' work, connecting partners with valuable contacts and “resources and information that would be helpful for their work.” One participant even described partners actively seeking their support, “reach[ing] out and ask[ing] for introductions.” In summary, many of these relationships were mutually beneficial.

4 Discussion

Knowledge brokers can be instrumental in improving education and increasing equitable opportunities for all students, as suggested by previous studies (Ainscow, 2012; Bélanger and Dulude, 2023). To date, research has primarily focused on how knowledge brokers mobilize knowledge and resources to leaders and educators to improve education (e.g., Malin et al., 2018; Rycroft-Smith, 2022; Shewchuk and Farley-Ripple, 2022), which is a necessary but insufficient condition to understanding the creation and movement of knowledge. Less is known about the knowledge brokers' relational ecosystems, defined as their partner networks, which we argue may provide essential insights. Given the importance of knowledge brokers for knowledge mobilization, it is crucial to better understand their relational ecosystems, including the support they receive and how partners shape their priorities, methods, and knowledge products. Therefore, this study focused on exploring knowledge brokers' relational ecosystems.

This study used egocentric social network analysis to analyze survey and interview data to better understand the relational ecosystems of knowledge brokers, and as such their social capital (Scott, 2017). To answer the first research question about the characteristics of these relational ecosystems, we first analyzed the complete partner network based on the survey data. The evidence suggests that participating knowledge brokers partnered with numerous and heterogeneous individuals and organization types, including researchers, leaders, foundations, and intermediaries. This finding indicates access to complementary resources and supports tailored to knowledge brokers' needs and objectives. Second, we examined the knowledge brokers' core relational ecosystem based on interview data. Core relational ecosystems ranged in size between three and 13 partners whom the knowledge brokers considered most important. These core relational ecosystems were characterized by strong relationships, partly driven by individual team members' social networks and comprising micro-networks, and were well-connected (i.e., network closure). This new understanding of the quality of ties and structures of relational ecosystems is crucial as they shape the transfer of knowledge, including the speed of spread, type of knowledge, and stability of relationships (Granovetter, 1973; Coleman, 1988; Reagans and McEvily, 2003; Scott, 2017). For example, the evidence for strong partner ties suggests that knowledge brokers could access non-routine, timely, and complex knowledge, whereas some of this knowledge might be redundant given that some partners' relational ecosystems were so well-connected (Brass et al., 1998; Reagans and McEvily, 2003; Phelps et al., 2012; Tortoriello et al., 2015; Scott, 2017).

Answering the second research question on how the relational ecosystem shaped and supported knowledge brokers' knowledge creation and mobilization, our data indicates that beyond being collaborators, partners provided infrastructure and financial resources, served as intermediaries for knowledge mobilization, provided insights into policy contexts and their audiences' needs, supported knowledge brokers' capacity building, and connected knowledge brokers to people and organizations. These relationships were not one-directional, but often mutually beneficial, with support and influence flowing in both directions, resulting in reciprocated relational ecosystems. Aligned with Nieves and Osorio (2013) study, our findings suggest that these relational ecosystems supported and improved knowledge brokers' knowledge creation and mobilization.

4.1 Key themes and implications for practice and policy

Beyond answering our research questions, this study yielded a few counterintuitive findings, tensions, and salient takeaways with implications for policy and practice.

4.1.1 Long-lasting reciprocated relationships despite dynamic nature of relational ecosystems

This study provides evidence for many long-standing organizational relationships characterizing relational ecosystems and simultaneously emphasizes their dynamic nature—a seemingly counterintuitive finding. For instance, the evidence suggests a constant flux in partners, frequency of interaction, and forms of support, challenging the notion of stability in the relational ecosystem as suggested by the accounts of many long-lasting relationships. This indicates that relationships can be both stable and dynamic: knowledge brokers might engage with their partners for a long time (i.e., stability); however, these relationships evolve in, for example, the frequency of interaction, focus of collaboration, or forms of support due to, inter alia, changing priorities and personnel (i.e., dynamism).

Additionally, the relational ecosystems of knowledge brokers were not solely influenced by their priorities, needs, and personnel. They were intricately embedded in interconnected relational ecosystems, where partners' priorities, needs, and personnel also played a significant role in shaping the relationship, as did the knowledge brokers. The evidence for many mutually beneficial or reciprocated relationships highlights the importance of the support knowledge brokers provide to their partners, which is equally significant as the support the partners offer. This idea of individual actions and social relationships being situated within and shaped by social networks is often referred to as embeddedness (Granovetter, 1985; Kilduff and Brass, 2010), which has also been studied in educational settings (Coburn et al., 2013).

Given this dynamic, knowledge brokers must proactively and strategically cultivate relational ecosystems and adapt them to evolving needs and challenges while being conscious of long-term goals. Strategically cultivating the relational ecosystem is crucial, as relationships typically require time investment, and only a limited number of relationships can be maintained. As priorities shift and organizations undergo churn, both the knowledge brokers and their partners must recognize and respond to changing relational needs. Knowledge brokers can achieve this by maintaining long-lasting partnerships while actively engaging new partners to expand the relational ecosystem. Toward that goal, knowledge brokers should remain responsive to evolving needs and continue to support both their own goals and those of their partners, thereby enhancing the overall effectiveness and sustainability of their relational ecosystems.

4.1.2 Human relationships foundational for relational ecosystems

Besides the relational ecosystems' dynamic nature, this study emphasizes the inherent personal and human qualities of relational ecosystems. Evidence for relational ecosystems being partly driven by individuals, affective ties, and comprised of micro-networks emphasizes the human component of organizational networks: human connections are the foundation of organizations' relational ecosystems. Inter-personal ties have previously been recognized as further inter-organizational ties (Granovetter, 1973; Breiger, 1974; Krackhardt, 2003), with implications for organizations, particularly knowledge broker organizations engaged in deeply relational knowledge mobilization efforts. Such organizations might thrive when they put their individual members' social networks first, and the organizational relational ecosystem second.

Consequently, organizations engaged in knowledge mobilization work might benefit when team members actively build, maintain, and nourish their personal networks, and are well-served by creating conditions that allow their team members to cultivate these relationships. This might include supporting them in attending conferences, creating time and space for networking activities, and encouraging collaboration across various organizations and platforms. By fostering such an environment, organizations can support their team members' personal networks and, in turn, enhance their relational ecosystems, leading to perhaps more effective knowledge mobilization and ultimately improving organizational outcomes.

4.1.3 Diverse priorities drive diverse relational ecosystems

While each knowledge broker cultivated a relational ecosystem with a diverse set of partners (e.g., foundations, media outlets, researchers) that provided various forms of support, the composition of their networks differed across the knowledge brokers. Some knowledge brokers partnered with organizations of the same type (i.e., some ego-alter similarity), whereas others did not specify any partners of the same organization type (i.e., no ego-alter similarity). This suggests that different knowledge brokers might nurture relational ecosystems based on their priorities, needs, and organization types. Consequently, it is conceivable that some knowledge brokers required complementary organizations to support their knowledge mobilization efforts, while others sought out similar organization types for concerted efforts. Alternatively, these differing degrees in ego-alter similarity might be the result of different opportunities to form ties. For example, while one knowledge broker might connect with their partners at an academic conference, another knowledge broker might connect with partners through geographic proximity and working in the same district.

Either way, knowledge brokers might benefit from creating a strategy to build and maintain their relational ecosystems, seeking out partners based on their priorities, and attending events that allow them to foster their relational ecosystems.

4.1.4 Balancing strong ties and enmeshment

Our findings suggest that these knowledge brokers drew on a wider relational ecosystem with heterogeneous partners and a core relational ecosystem characterized by strong and reciprocated ties embedded in a well-connected social network (i.e., network closure). These strong ties allowed knowledge brokers to receive support and engage in exchanges that improved their knowledge creation and mobilization efforts, indicating high levels of trust developed over time (Daly, 2009). However, despite having these heterogeneous relationships, these strong ties may create an “enmeshed” ecosystem in which new information is not likely to enter. In other words, knowledge brokers' greatest strength (i.e., strong ties with diverse partners) may also be their greatest limitation.

This finding is closely connected to what Burt (2017) described as networks with high levels of constraint. He differentiated between internal and external constraint. Internal or in-group constraint refers to well-connected networks (i.e., closure) within an organization, which improves the organization's communication and coordination and allows them to “take advantage of brokerage beyond the group” (Burt, 2017, p. 49). Conversely, organizations with high levels of external constraint have contacts that are well-connected beyond the group, making their knowledge often redundant (Burt, 2017).

This finding suggests that brokers need to actively (re-)engage with new partners and different sources of information to maximize and leverage a more powerful relational ecosystem. While having the ability to draw on the support of a robust set of partners was a strength, there might also be some drawbacks, including potentially not having access to novel ideas or working in an echo chamber.

4.2 Limitations and implications for research

This study has several limitations due to its design and data collection. To begin with, the results are not generalizable as the number of knowledge brokers was limited. We purposely selected six equity-focused, evidence-based knowledge broker organizations that intentionally created and mobilized resources to different levels of the education system. As such, they are not representative of all knowledge brokers in the education space. Second, the descriptions of relational ecosystems are based on individual team members' perceptions and accounts. Our findings indicate that these perspectives can be quite different, depending on a team member's role, perspective, and experience. Third, the data, by its nature, is limited and might be prone to recall bias. Also, the egocentric approach does not allow employing the full set of network concepts and techniques (Wasserman and Faust, 1994; Borgatti et al., 2018). For example, the network closure measure is only a proxy for how well-connected the relational ecosystems actually are, and a sociocentric network approach would yield more reliable results. Fourth, the interviews showed that networks are affected by temporal fluctuations, both in terms of the intensity of the exchange and the type of cooperation. It should therefore be borne in mind that the available data are momentary impressions. Finally, the interview data relate to knowledge brokers' most important partners, or their core relational ecosystem; and the data we collected for the wider relational ecosystem was limited.

By focusing on evidence-based, equity-focused knowledge brokers, this study took an optimistic perspective on knowledge brokers' work, assuming good intentions and a positive impact. However, knowledge brokers are not a panacea for bridging the gap between research, policy, and practice. Also, knowledge brokering is not a neutral activity; knowledge brokers can act in political and racialized ways. Their objectives and agenda often shape, among other things, the knowledge they share, their relational ecosystems, and the audiences they target, sometimes resulting in harmful outcomes.

Despite these limitations, this study provides a “refinement of understanding” (Stake, 1995, p. 7) and avenues for future research. For example, future studies should try to include more perspectives from within the knowledge broker organizations to obtain the most differentiated picture of the relational ecosystems possible. Also, it would be conceivable to interview the partner organizations, conduct a sociocentric social network analysis study, or obtain comprehensive data on the wider partner networks, as these approaches would enable a deeper understanding of the networks. Future studies should also consider the development of relational ecosystems and accompany knowledge brokers over a longer period in a longitudinal study. Nevertheless, this study is the first to give insight into knowledge brokers' relational ecosystems and provides a comprehensive understanding aligned with theoretical expectations.

5 Conclusion

This study is the first to shift the focus away from knowledge brokers' audiences to their relational ecosystems, demonstrating that these partner networks provide essential support and shape the knowledge brokers' efforts. This suggests an important refocus on the scholarship around knowledge brokers. By doing so, it provides further evidence for the importance of social capital and social networks in knowledge mobilization (e.g., Farley-Ripple and Yun, 2021; Weber and Yanovitzky, 2021; Rycroft-Smith, 2022). The findings offer a deeper understanding of key processes, people, and ideas involved in transforming education, including sometimes distant and unseen organizations and individuals in the broader knowledge mobilization ecosystem, suggesting a potential hidden influence in creating and mobilizing knowledge.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data is confidential; authors do not have the right to share the data.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of California San Diego, Office of IRB Administration. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The Ethics Committee/Institutional Review Board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin because the IRB review board determined that formal written consent was not required for this study given that participants were already participating in an overlapping research and development project that included a signed document outlining research participation. However, verbal consent was obtained before each interview even though the IRB review board did not require this.

Author contributions

AC: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Supervision. LRB: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft. ML: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. MR: Writing – review & editing. AJD: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (INV-031977). The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ainscow, M. (2012). Moving knowledge around: strategies for fostering equity within educational systems. J. Educ. Change 13, 289–310. doi: 10.1007/s10833-012-9182-5

Bélanger, N., and Dulude, E. (2023). Investigating the challenges and opportunities of a bilingual equity knowledge brokering network: a critical and reflective perspective from university partners. Policy Fut. Educ. 21, 58–74. doi: 10.1177/14782103211041484

Bernardi, L., Keim, S., and Klärner, A. (2014). “Social networks, social influence, and fertility in Germany: challenges and benefits of applying a parallel mixed methods design,” in Mixed Methods Social Networks Research. Design and Applications, eds. S. Domínguez, and B. Hollstein (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 65–89.

Borgatti, S. P., Everett, M. G., and Johnson, J. C. (2018). Analyzing Social Networks, 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). “The forms of capital,” in Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, eds. J. G. Richardson (New York, NY: Greenwood Press).

Brass, D. J., Butterfield, K. D., and Skaggs, B. C. (1998). Relationships and unethical behavior: a social network perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 23, 14–31. doi: 10.2307/259097

Breiger, R. L. (1974). The duality of persons and groups. Soc. Forces 53, 181–190. doi: 10.2307/2576011

Burt, R. S. (1998). The gender of social capital. Ration. Soc. 10, 5–46. doi: 10.1177/104346398010001001

Burt, R. S. (2004). Structural holes and good ideas. Am. J. Sociol. 110, 349–399. doi: 10.1086/421787

Burt, R. S. (2017). “Structural holes versus network closure as social capital,” in Social Capital. Theory and Research, eds. N. Lin, K. Cook, and R. S. Burt (Routledge), 31–56.

Caduff, A., Lockton, M., Daly, A. J., and Rehm, M. (2023). Beyond sharing knowledge: knowledge brokers' strategies to build capacity in education systems. J. Prof. Capit. Commun. 8, 109–124. doi: 10.1108/JPCC-10-2022-0058

Carolan, B. V. (2014). Social Network Analysis and Education: Theory, Methods & Applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Casciaro, T. (2014). “Affect in organizational networks,” in Contemporary Perspectives on Organizational Social Networks, Vol. 40, eds. D. J. Brass, G. Labianca, A. Mehra, D. S. Halgin, and S. P. Borgatti (Leeds: Emerald Group Publishing Limited), 219–238. doi: 10.1108/S0733-558X(2014)0000040011

Coburn, C. E., Mata, W. S., and Choi, L. (2013). The embeddedness of teachers' social networks: evidence from a study of mathematics reform. Sociol. Educ. 86, 311–342. doi: 10.1177/0038040713501147

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 94, S95–S120. doi: 10.1086/228943

Cooper, A., and Shewchuk, S. (2015). Knowledge brokers in education: how intermediary organizations are bridging the gap between research, policy and practice internationally. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 23, 118–118. doi: 10.14507/epaa.v23.2355

Crossley, N., Bellotti, E., Edwards, G., Everett, M. G., Koskinen, J., and Tranmer, M. (2015). Social Network Analysis for Ego-Nets. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Dagenais, C., Lysenko, L., Abrami, P., Bernard, R., Ramdé, J., and Janosz, M. (2012). Use of research-based information by school practitioners and determinants of use: a review of empirical research. Evid Policy 8, 285–309. doi: 10.1332/174426412X654031

Daly, A. J. (2009). Rigid response in an age of accountability: the potential of leadership and trust. Educ. Administr. Q. 45, 168–216. doi: 10.1177/0013161X08330499

Daly, A. J., and Finnigan, K. S. (2011). The ebb and flow of social network ties between district leaders under high-stakes accountability. Am. Educ. Res. J. 48, 39–79. doi: 10.3102/0002831210368990

Darling-Hammond, L. (2013). “Inequality and school resources: what it will take to close the opportunity gap,” in Closing the Opportunity Gap: What America Must do to Give Every Child an Even Chance, eds. P. L. Carter, and K. G. Welner (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 77–97.

Farley-Ripple, E. N., May, H., Karpyn, A., Tilley, K., and McDonough, K. (2018). Rethinking connections between research and practice in education: a conceptual framework. Educ. Res. 47, 235–245. doi: 10.3102/0013189X18761042

Farley-Ripple, E. N., and Yun, J.-Y. (2021). “An ego-network approach to understanding educator and school ties to research: from basic statistics to profiles of capacity,” in Networks, Knowledge Brokers, and the Public Policymaking Process, eds. M. S. Weber, and I. Yanovitzky (Springer International Publishing), 155–181.

Finnigan, K. S., Daly, A. J., Caduff, A., and Leal, C. C. (2021). “Broken bridges: the role of brokers in connecting educational leaders around research evidence,” in Networks, Knowledge Brokers, and the Public Policymaking Process, eds. M. S. Weber, and I. Yanovitzky (Springer International Publishing), 129–153.

Fraser, C., Herman, J., Elgie, S., and Childs, R. A. (2018). How school leaders search for and use evidence. Educ. Res. 60, 390–409. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2018.1533791

Gould, R. V. (1989). Power and social structure in community elites. Soc. Forces 68:531. doi: 10.2307/2579259

Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol. 78, 1360–1380. doi: 10.1086/225469

Granovetter, M. S. (1985). Economic action and social structure: the problem of embeddedness. Am. J. Sociol. 91, 481–510. doi: 10.1086/228311

Haddad, N. (2020). Foundation-sponsored networks: brokerage roles of higher education intermediary organizations. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 28, 122–122. doi: 10.14507/epaa.28.4501

Kadushin, C. (2012). Understanding Social Networks. Theories, Concepts, and Findings. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kilduff, M., and Brass, D. J. (2010). Organizational social network research: core ideas and key debates. Acad. Manag. Ann. 4, 317–357. doi: 10.5465/19416520.2010.494827

Krackhardt (2003). “The strength of strong ties: The importance of philos in organizations,” in Networks in the Knowledge Economy, eds. R. Cross, A. Parker, and L. Sasson (Oxford University Press), 82–108.

Lin, N. (2001). Social Capital. A Theory of Social Structure and Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Liou, Y.-H., and Daly, A. J. (2019). The lead igniter: a longitudinal examination of influence and energy through networks, efficacy, and climate. Educ. Administr. Q. 55, 363–403. doi: 10.1177/0013161X18799464

Lockton, M., Caduff, A., Rehm, M., and Daly, A. J. (2022). Refocusing the lens on knowledge mobilization: an exploration of knowledge brokers in practice and policy. J. Educ. Policy Manag. 7, 001–028. doi: 10.53106/251889252022060007001

MacGregor, S., and Phipps, D. (2020). How a networked approach to building capacity in knowledge mobilization supports research impact. Int. J. Educ. Policy Leadersh. 16, 1–20. doi: 10.22230/ijepl.2020v16n6a949