- 1Queen Maud University College, Trondheim, Norway

- 2Educational Psychological Service, Melhus, Norway

Children with language disorders face different challenges in their daily school routines. Accessing tools and having resources promoting a well-structured and inclusive environment is necessary to ensure a pleasant and successful passage through primary school.

The current article seeks to highlight stimulating ideas, creating a foundation for involving everyone caring for and educating students with language disorders, particularly children with special needs. Moreover, experts need to prioritize educational initiatives aimed at language disorders, particularly emphasizing early detection, prevention, and specialized care. Balancing the need for students to get adequate attention while avoiding unequal treatment can be as difficult as dealing with a two-sided coin. Moreover, it is crucial to acknowledge that academic research should prioritize finding the best ways to support students with special needs who have language impairments. All professionals working with these students, such as speech therapists, psychopedagogical experts, and general therapists, need to focus on developing interventions and options to aid in their growth.

Introduction

The principle of inclusion is key in Norwegian education policy, and when combined with tactics such as early intervention and customized teaching, it should lead to a school system that offers equal chances for education and growth to every child and adolescent, no matter their situation or potential diagnoses (Ministry of Education and Research, 2019). Inclusion entails every child feeling they belong in the community, being free to be themselves in an inclusive environment, and growing according to their own beliefs. In order to promote inclusivity, the school needs to adjust its curriculum to cater to the diverse needs of all children. Creating an environment that is inclusive is the goal and aspiration for the school’s functions. According to the Norwegian ministry of Education and Research, enhancing the quality of regular general education is the key step in promoting and enhancing inclusive practices (Ministry of Education and Research, 2019). A suitable learning environment is crucial for the development of all students, particularly those who face challenges academically and/or socially (Wendelborg, 2015; The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2021). Having a culture of inclusion and early intervention, as well as competency, is crucial for the school to improve and for children to learn, master, and thrive in an inclusive community (Ministry of Education and Research, 2019). Children and adolescents with developmental language disorders frequently require ongoing assistance and support in the school setting. The current article will focus on how the school can assist children with developmental language disorders in their academic and social needs, while also ensuring their active involvement in an inclusive community.

The process of acquiring language starts in the mother’s womb and progresses throughout childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. Language acquisition in children’s development varies greatly among individuals. It is evident that most children successfully complete the resilient process of language development. Using language is crucial for expressing our internal thoughts, desires, objectives, and motivations, comprehending others’ messages, inquiring, issuing instructions, offering opinions, and sharing thoughts. Every day, language is utilized in multiple situations as the primary tool to navigate in society. Language is complex and its structure is not arbitrary. We adhere to certain rules. One aspect involves elements like the order of words, changes in words, and the spoken aspect of language. Another aspect involves the meaning of words, how they are connected, and their arrangement. Finally, there is the aspect of language use in conversations, social settings, and adjusting speech to fit the context. These aspects are of course the ones referred to in linguistics as, phonetics, morphology, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics.

The goal of this article is to offer understanding and information on language disorders and support in a diverse educational setting. By beginning with a summary of the definition, symptoms, causes, and diagnosis, and then going deeper into possibilities for interventions and teamwork.

Difficulties with language, speech and communication

Children who struggle with language issues typically rely on language for communicating, although they usually use less complex language compared to their peers. Simpler or incorrect grammar, verb tenses, words, expressions, filler words like “hmmm,” “ehhhh,” use of vague words like “thing” are examples of how language can be for this group (Bishop, 2020; Norbury et al., 2016). Nevertheless, children with language, speech, and communication challenges exhibit wide-ranging differences in performance, behavior, and general functioning.

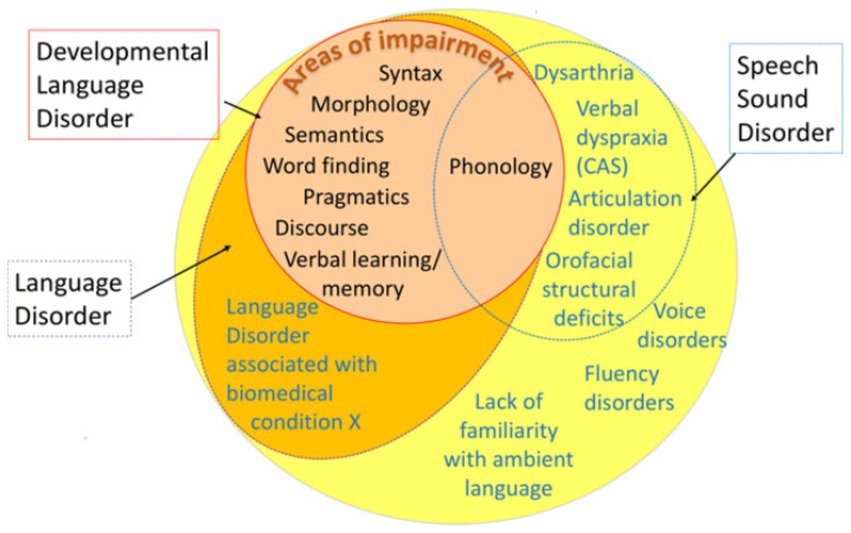

In order for us to effectively communicate, address challenges, access services, conduct research, and implement appropriate measures, it is essential that we all use consistent terminology and categorization. Hence, an important collective research project, known as CATALISE Norway and corresponding to the previous English CATALISE study, was conducted in Norway (Kristoffersen et al., 2021). The research examined terminology used for children and young individuals who have challenges with speech, language and communication, based on consensus between professionals with different disciplinary backgrounds (Bishop et al., 2017; Kristoffersen et al., 2021). Figure 1 displays a summary of the findings from the English CATALISE research that have been affirmed for use in the Norwegian context.

Figure 1. Speech, language and communication needs (Bishop et al., 2017).

The figure above shows that there are three distinctive groups that have been classified. These categories include developmental language disorder (DLD), speech sound disorder, and language disorder linked to a biomedical condition X due to genetic or neurological reasons. The categories can share common areas of difficulty, but the underlying causes of the impairments vary greatly. This indicates that challenges related to language, speech, and communication are multifactorial, and it is important to consider the different factors in play when implementing interventions (Bishop et al., 2017).

There are many and various opinions and approaches on how to comprehend, structure, classify, study, and address language disorders in children. The CATALISE Norway research recommends labeling children with ongoing language difficulties beyond the age of four or five as having a language disorder, if this significantly affects their access to education, enrollment in school or kindergarten, and society at large (Kristoffersen et al., 2021). The terms used in the Norwegian version of the model harmonize with the English model, British language terms and terms found in international classification systems like The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The ICD is currently utilized in Norway and serves as the foundation for diagnosing patients in the healthcare system.

In this present article, the terminology agreed upon by the consensus will be used. We will also discuss briefly language disorders associated with a medical condition X, since it is crucial for educators to be aware of these conditions and their comorbidity with language disorders. The primary emphasis of the article will be on developmental language disorder, its impacts, and strategies in the educational setting.

Language disorder associated with biomedical condition X

Language is way more complex than we think; and is one of the key elements for functioning (Schaeffer et al., 2023).

It is common for language disorders to co-occur or have comorbidities with other challenging potential diagnoses. These challenges that exist simultaneously comprise of brain injury, childhood onset of acquired epileptic aphasia, progressive nerve conditions, cerebral palsy, speech restrictions due to sensorineural hearing loss, genetic disorders like Down syndrome, children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and intellectual disabilities. When a child presents with both a biomedical condition and language disorders, they require assistance and treatment for both the language disorders and the unique features of the biomedical condition (Bishop et al., 2017).

Frequent co-occurrence or comorbidity of language disorders and other learning challenges in reading and math domains is common (Chieffo et al., 2023). The academic skills of the individual are significantly below what is expected for their age, causing a major impact on their performance in school or work, as well as in their daily activities or functioning in general.

The comorbidity of DLD and other conditions is an emerged subject. The research on the subject is increasing quickly, but there is still a lot left to do (Snowling et al., 2020, 2021). This idea of having multiple conditions at the same time in individuals with DLD is not a new idea (Matson and Goldin, 2013). An example of a common comorbid condition is the one found in children with ADHD (Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder). ADHD is classified as a neurodevelopmental disorder in both DSM-5 and ICD11 (Gomez et al., 2023). The diagnosis should utilize the criteria outlined in DSM-5 (helsedirektoratet.no). Children diagnosed with ADHD perform much lower in tests assessing overall language abilities, including comprehension, production, and pragmatic language skills. It is advisable to evaluate language function in individuals with ADHD, and interventions to support language function are frequently applicable.

Additionally, several studies within the field of Psychology have frequently documented a high correlation between SLD and emotional issues. Recent research shows that children with DLD suffer from noticeably higher levels of emotional distress when compared to their peers without DLD (Chieffo et al., 2023; Beitchman and Young, 1997; Bryan et al., 2004).

Developmental language disorder (DLD)—occurrence, cause and symptoms

About 7% of children are affected by developmental language disorder, often referred to as DLD (Norbury et al., 2016). It is a long-lasting and severe challenge that impacts the process of learning language from the start, continues during childhood and adolescence, and can lead to enduring consequences in adulthood. Hence, identifying and addressing issues early on is extremely vital.

The linguistic issues cannot be attributed to the pace of growth or a specific biomedical cause, therefore the causal connections remain ambiguous. Different theories suggest that failures in auditory processing speed, verbal short-term memory, implicit procedural learning, and statistical learning, as well as grammatical skills, could be potential factors. Today, it is widely agreed that there is no single root cause, but rather multiple risk factors that combine to have an impact (Torkildsen et al., 2021). Children and adolescents with Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) exhibit varying levels of non-verbal skills, with DLD possible at any non-verbal cognitive level as long as there is not a mental developmental disability (Norbury et al., 2016). Recent research validates the significance of genetic burden; Approximately half to 70 % of children with DLD have a relative who also has the disorder. Moreover, alterations have been discovered in the FOXP2 gene, identified as the language gene (Snijders Blok et al., 2021).

DLD shows as challenges with comprehension as expression of language. Each individual exhibits difficulties in unique ways. The challenges may vary according to the individual’s growth. There is a wide range of variability in terms of the linguistic areas impacted and the extent of these difficulties (severity level). Challenges in language include syntax, morphology, semantics, word-finding, pragmatics, discourse, verbal learning, memory and phonology. This implies that individuals with DLD struggle more to comprehend, analyze, and retain complex sentences. A limited vocabulary and challenges in grasping abstract ideas make it necessary to invest a significant amount of effort in comprehending relationships and links between written texts and other linguistic data (Throneburg et al., 2000). One might encounter difficulties in narrating a story and staying “stuck” with a specific subject, providing pertinent details to the audience or seeking clarification when there is confusion. This might result in that the children with DLD can potentially be less talkative during class, when talking to friends, and when working together on group projects (Krishnan et al., 2021).

The challenges experienced by a person with DLD may also be specific to language. For instance, Norwegian children usually have difficulties with verb conjugation, utilize fewer complex grammatical structures in sentence construction, struggle with sentence repetition, and experience more instances of omitting words or parts of words (Torkildsen et al., 2021). Multilingual children may also exhibit lower verbal and reading comprehension abilities in the language used at school compared to monolingual students (Torkildsen et al., 2021). In individuals who speak multiple languages, Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) will usually be present in all their languages. Being multilingual does not lead to a higher risk of DLD, but it can often make it harder to detect DLD (Torkildsen et al., 2021).

Possible consequences of language disorders: a vulnerable situation

Developmental language disorder (DLD) results in a marked and enduring functional impairment. Children who struggle with language at the beginning of their school journey are more likely to face challenges in reading and academic performance compared to their classmates. This may also impact their social interactions, as well as their future educational and career opportunities (Hagen et al., 2017). There is not much proof that the gap reduces with time according to Bishop et al. (2017).

Difficulties with language can impact various aspects of children’s lives. It is not rare to experience social and emotional challenges. Some people might experience feelings of frustration, rejection, low self-esteem, isolation, nervousness, sadness, and diminished social abilities. This can manifest in behavior, such as when the child is fidgety, inattentive, unmotivated, and occasionally misbehaving.

School absenteeism that is not by choice is seen as a sign linked to various diagnoses like language disorders, social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, specific phobias, major depression, oppositional defiant disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and adjustment disorder (Kawsar et al., 2023). Often, children experience physical symptoms that require assessment by a doctor to rule out any potential underlying medical issues. Children who have school refusal are frequently scared to attend school, scared to the point where they are reluctant to depart from their home (Kawsar et al., 2023; Lingenfelter and Hartung, 2015; Kearney and Albano, 2004).

School absenteeism is not a formal diagnosis, involuntary school absence poses challenges for children, families, and school staff, while school refusal is a specific issue to address. Not going to school has major impacts on children’s social, emotional, and academic growth in both the short and long term. Identifying problems early and offering interventions to avoid more issues is crucial. A team effort involving caregivers, educators, parents, and mental health professionals is essential for evaluating and managing school refusal.

The Janus face of inclusion—dilemma the school faces in its provision and inclusion for students with disabilities

Nordahl et al. (2018) and Ministry of Education and Research (2019) reported that numerous children and youth requiring special assistance are not receiving the necessary support. They are frequently removed from the class setting to be given a separate opportunity, whether it be one-on-one with an adult or in smaller groups. Students who have special educational needs frequently encounter adults lacking the necessary skills. The Children’s Ombudsman discovered in its study on special education for primary school students that many do not benefit from the education, have a poorer school environment, and are excluded from participating in their education (The Children’s Ombudsman’s professional report “Without goals and meaning?” 2017, p. 7). Hence, the primary objective is to enhance the quality of education in schools to facilitate students’ learning, mastery, and growth within an inclusive environment (Ministry of Education and Research, 2019; Nordahl et al., 2018). Norwegian research on inclusion has given specific attention to academic inclusion (Keles et al., 2022).

Children and young people come to school with different experiences, prior knowledge, attitudes and needs, and some pupils need special accommodation. § 11–1 of the Education Act specifies that school education must be adapted to the individual pupil’s abilities and requirements, while § 11–6 gives pupils who do not or cannot get satisfactory benefit from the ordinary provision, the right to individually adjusted education (Education Act, 2024). The proportion of pupils receiving special education has remained stable at just under 8% in recent years. In the school year 2022–2023, 7.8% of all pupils received special education (The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2022).

Special education and adapted education should help ensure that children get the help they need, and that they experience a good learning environment both academically and socially. There are still many children who do not get the help they need, get help too late or are met with too low expectations (Ministry of Education and Research, 2019). Many children express that they experience a lack of connection between regular education and special education, while at the same time they are shut out of the community and are not allowed to participate in activities together with the class (Barneombudet, 2017). A state-appointed expert group that evaluated the provision for children and young people in need of special accommodation concluded that the special education system is not very functional and exclusionary (Nordahl et al., 2018).

There are some complex connections between the inclusion and strengthening of the ordinary provision on the one hand, and children’s rights and needs for special educational assistance on the other. This dynamic balance between inclusion and special educational measures is often described as a field of tension or a dilemma (Solli, 2010). The challenges the school faces when it comes to including children with disabilities have also been metaphorically described as “Janus-faced” (Fylling, 1998), which denotes the presence of two conflicting aspects. In the same way that Janus has two faces that look in different directions, the term highlights the dilemma of handling both special educational measures and inclusion for pupils who need special accommodation in school (Solli, 2010). Despite their intention to provide equal opportunities for children with special needs, special educational measures can inadvertently create barriers that hinder their sense of belonging in the community (Fylling, 1998; Nordahl et al., 2018; Solli, 2010). On the one hand, special educational assistance can thus contribute to strengthening children and young people’s individual development and learning, which can promote social participation and community. On the other hand, special educational assistance can lead to stigmatization and limit children and young people’s participation in the ordinary provision (Nordahl et al., 2018).

Belonging and participation academically and socially—an inclusive approach

All children have the right to be heard in matters that concern them and the child’s best interests must be a fundamental consideration cf. the Convention on the Rights of the Child Article 3 and 12, the Basic Law §104 and the Administration Act §17. Children and young people have the right to be heard in matters that concern them, regardless of age or circumstances. The starting point is to hear the child directly, but the child can also be heard through objective people, parents, through letters and other things. The children’s point of view must be given due weight in accordance with age and maturity (The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2017, p. 4; Education Act, 2024). Here, the emphasis is on the child in the singular and specific form (Eriksen and Germeten, 2012). In other words, it is necessary to start from what the student himself needs to thrive, develop, and learn. In other words, an individual perspective must be obtained where the child’s own needs are at the center (Eriksen, 2019). In the assessment of the child’s best interests, the child’s own perception must be the central one. The assessment must be properly carried out and rooted in specialist literature, research and the child’s view (The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2017, p. 5). Inclusion is also often regarded as a subjective positive experience of belonging and professional mastery in social communities (Uthus, 2020). An inclusive approach for children with language difficulties at school involves a number of different strategies, such as compensatory measures for language disorders, measures linked to areas of language difficulties, measures for coexisting difficulties and measures linked to biomedical conditions.

There is no single best approach (Leonard, 2014). Measures for children with language disorders should be based on a broad survey of the child’s linguistic and cognitive strengths and weaknesses. Standardized tests should be supplemented with observations of the child in their natural surroundings and interviews with carers and educators (Torkildsen et al., 2021). The measures should focus on the skills that have the greatest functional relevance (that is, practical importance for communication) in the student’s everyday school and daily life. Many intervention studies do not only focus on work with particular linguistic structures or words, but also more general skills such as linguistic interaction with others and strategies to master the difficulties.

Different measures can be implicit or explicit. Implicit methods are very useful for indirect work, collaboration. The teachers and other adults around the student are then guided in being good language models (Stehle Wallace et al., 2022). Children who have mild to moderate difficulties can have an effect from indirect measures (the work is led by a speech therapist and carried out by a non-speech therapist) as long as the educational staff/teachers receive close support, training and guidance (Ebbels et al., 2019). Implicit and direct measures are often mixed in practice. Children with DLD also need individual and specialized measures, explicit measures (speech therapist) or special educators with expertise in language disorders. The speech therapist/special education teacher must have time to work directly with them and must collaborate with their families and educational institutions for an effect on function. The collaboration is important in various phases: concern phase, mapping and investigation, facilitation and measures, evaluation and assessment.

For children with DLD, it is particularly important that teachers have knowledge of language development, and the connection between language and social–emotional skills and the influence on the pupil’s actions, adaptability, professional development and mental health. For example, knowing that a language disorder is a risk factor for reading and writing development and that, in the long term, it can have consequences for the ability to use written information and text to acquire other subjects, can contribute to both a better understanding of the student’s world, what can be expected and what needs are the basis for an adapted arrangement. It is about creating a class and learning environment that sees the academic and linguistic learning goals in context, uses a reasoned choice of working methods and forms and is communicatively adapted to the students’ different language skills (Hulme et al., 2020; Tarvainen et al., 2021). In concrete terms, this means that the teacher adapts his own language, for example by speaking clearly and slowly and waiting for an answer or reaction. This is to take into account that the student may need more time to process the linguistically given information or questions. Long and complex instructions and tasks can be broken down and possibly visualized to make it easier to understand. The use of visual support for learning material, tasks and class activities is linked to the linguistic information provided in the teaching. Arrangements should also be made for repetition of subject matter and assignments. These are examples of adapted arrangements that can create prerequisites for the student’s professional and social affiliation and participation in teaching.

Partnership between families and school

Going to school is not exclusively only about learning the academic curriculum but it is more than just that. The history of the link between parental input and child language development is intricate, delivering interventions in partnership with parents is crucial because the family serves as the child’s main source of strength and support (Law et al., 2019a; Law et al., 2019b; de López et al., 2021).

Several studies have reported a huge lack of collaborative work between the parents and the school or pedagogues /specialists working with their child with language difficulties. Partnership is defined by a shared understanding, a relationship based on respect and trust, collaborative decision-making, and inclusive processes that consider family beliefs, needs, and preferences (An and Palisano, 2014), and this implies that there is a need of common understanding or being on the “same page” that is necessary for the child’s best interests, academically, psychologically, socially, emotionally, etc.

Children with language disorders are at risk of developing reading and writing difficulties. They may not be interested in books and the written language in the first place because the linguistic information is difficult to understand, process and talk about. This can also lead to lower motivation to learn to read and write. It will be essential here both to work with motivation, reading comprehension and to facilitate mastery.

Interdisciplinary collaboration

According to Bronfenbrenner’s developmental ecology perspective, the emphasis is on the individual’s growth within their environment (e.g., school, family, hobbies), and a system-focused approach in decision-making and implementation will feel instinctive. A model of intervention that involves ‘the team around the student’ to assist with the student’s language and communication growth could provide a thorough and meaningful approach tailored to the student’s needs in their daily school routine. However, disciplinary differences with regard to the conceptualization, assessment and treatment of DLD prevail (Gallagher et al., 2019).

Everyone’s contribution in securing this offer is valued here as well. Success of this approach hinges on the need for opportunities to contemplate, assess, and engage in discussions.

It is necessary to have time and chances to come together and interact in order to develop shared skills and have transparent discussions about duties, positions, assistance, and a customized approach that addresses students’ requirements and promotes academic, social, and perceived inclusivity. It is crucial that teachers are backed by the school system and management, the professional community within the school and external partners, and are provided with the chance to gain specialized knowledge and skills (Glover et al., 2015).

Augmentative and alternative communication in the school experience

Some children DLD struggle with conventional communication and need an extra visual support like in the case of alternative and augmentative communication (AAC). AAC refers to communicating through methods other than verbal speech. AAC is a form of self-expression and serves as a valid communication method (Statped, 2021). Many individuals will acquire verbal communication skills at some point, while others will rely on alternative methods such as AAC for their entire lives. Furthermore, even individuals with strong verbal skills will find value in having communication presented visually (The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2022) as also stated earlier.

Everyday school can be emotionally draining for children with language difficulties. It can of course affect their learning and cognitive development but also their social life, the way they are included among their peers and of course the friendships that they can establish (Østvik et al., 2017). Here, AAC can be a great opportunity for children with DLD to be heard and be and feel included in the school settings. Inclusion involves acknowledging and catering to diverse needs, allowing students the chance to engage in the community (Aas et al., 2024). Inclusion is more than just external groups, as noted by Befring et al. (2019), who highlights that it also involves the student’s personal perception of the community. In modern management documents, the idea of inclusion holds a prominent position (Haug, 2021). Globally, the Salamanca Declaration holds a key role as an agreement supported by the United Nations (UN). The agreement has been endorsed by 92 nations, Norway included (UNESCO, 1994; Uthus, 2020). The agreement entails including all rivers in regular education. The basic idea of an inclusive school is that all children, despite any challenges or distinctions they may have, should be able to learn together whenever feasible. This inclusive school idea and the use of AAC is statutory in §11–1 and § 11–12 Education act (Education Act, 2024).

Enhanced chances for shared experiences and interactions with non-disabled peers may help AAC effectively support the inclusive education of students with complex communication needs. Studies are still being conducted to find the best ways to help students with complex communication needs communicate effectively without compromising their full inclusion in school (Iacono et al., 2022).

Compensatory measures

The following measures are recommended to ensure the best possible learning environment for children with DLD:

• When providing verbal information: provide clear directions, allow time for comprehension, and recapitulate crucial details.

• Written material should be simplified with the use of visuals and icons, include definitions for terms, and have questions placed alongside the text.

• Support information processing: utilize mind maps with the entire class, create visual plans and recipes, and collaborate on making graphs and posters together.

• Review the new vocabulary for upcoming subjects, implement the terms in the learning journey.

• Different forms of visual aids such as images, real-life examples, videos, word lists, color-coded systems, symbols, charts, and drawings are used to help students better grasp and create language.

• Auditory assistance: repeating information orally/using audio, checking for background noise.

• Engage prior knowledge: Recognize the relevance of previous knowledge to fully comprehend the learning material being presented.

• Arrangement, foreseeability: visual daily schedule and session plan, well-defined routines.

• Regulate speed, duration, quantity: It is crucial to allocate sufficient time for instructing students with language disorders. They frequently require you to speak slower, yet still in a natural manner. Ensure that the child comprehends the information by asking follow-up questions and engaging in dialog to confirm understanding.

• Children who have language disorders might also require additional time to respond. Allow them the necessary amount of time to reply.

• Multiple repetitions are crucial for students with language disorders to grasp concepts and linguistic expressions effectively and securely. Repetitions can be performed in various ways and engage multiple senses, such as verbally restating and summarizing key details in various scenarios

• Adjusting complexity: Being conscious of your language proficiency level is crucial when communicating.

• Considering alternative communication alternatives to frame a pleasant learning environment for the children who struggle with verbal communication.

• Try to engage the parents and families and give them a voice. Their perception of their child’s challenges is very important and they can see things from angles that the professionals do not see.

Conclusion

The present school accepts children aged 6 to 16 years old irrespective of personal, biological, social, or cultural factors.

To guarantee appropriate growth for children with language disorders in regular schools, it is essential to obtain the resources and strategies that encourage their full integration, create supportive environments, and consider both their challenges and strengths in educational activities. Establishing and organizing structured environments with established daily routines is considered important. Visual cues improve comprehension of the environment, supplementing verbal communication.

The above theoretical reflection aims to bring attention to thought-provoking ideas, establishing a basis for engaging all individuals involved in the care and education of students with language disorders, specifically children with special needs. Furthermore, specialists must focus on the educational efforts dedicated to language disorders, with a focus on early identification, prevention, and specialized treatment.

Children with language disorders should be made to feel included in their peer group and should engage fully in both academic and social events provided by the school. The incorporation and standardization of education for these students should consider assistance and adjustment.

Finding the right balance for students to receive necessary attention without experiencing unequal treatment can be challenging, like a two-sided coin (Janus face).

Last but not least, it is important to recognize that the focus of academic research on language impairments in students with special needs should begin with determining how to provide the most effective support for these children. Every discipline that interacts with these students (including speech language therapists, psychopedagogical professionals, and general therapists) should concentrate on creating interventions and options to support their development.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SC: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. HW: Writing – review & editing. JL: Writing – review & editing. AV: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aas, H. K., Uthus, M., and Løhre, A. (2024). Inclusive education for students with challenging behaviour: development of teachers’ beliefs and ideas for adaptations through lesson study. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 39, 64–78. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2023.2191107

An, M., and Palisano, R. J. (2014). Family–professional collaboration in pediatric rehabilitation: a practice model. Disabil. Rehabil. 36, 434–440. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2013.797510

Barneombudet. (2017). Barneombudets fagrapport 2017. Uten mål og mening? Elever med spesialundervisning i grunnskolen. Available at: https://www.barneombudet.no/uploads/documents/Publikasjoner/Fagrapporter/Utenmal-og-mening.pdf (Accessed May 12, 2024).

Befring, E. B., Næss, K. A. B., and Tangen, R. (eds.), (2019). Spesialpedagogikk. [Special education]. Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

Beitchman, J. H., and Young, A. R. (1997). Learning disorders with a special emphasis on reading disorders: a review of the past 10 years. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 36, 1020–1032. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199708000-00009

Bishop, D. V. (2020). Developmental language disorder: the term is not confined to monolingual children. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups 5:572. doi: 10.1044/2020_PERSP-20-00061

Bishop, D. V., Snowling, M. J., Thompson, P. A., and Greenhalgh, T.CATALISE-2 consortium (2017). Phase 2 of CATALISE: a multinational and multidiciplinary Delphi censensus study of problems with language development: terminology. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 58, 1068–1080. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12721

Bryan, T., Burstein, K., and Ergul, C. (2004). The social-emotional side of learning disabilities: a science-based presentation of the state of the art. Learn. Disabil. Q. 27, 45–51. doi: 10.2307/1593631

Chieffo, D. P. R., Arcangeli, V., Moriconi, F., Marfoli, A., Lino, F., Vannuccini, S., et al. (2023). Specific learning disorders (SLD) and behavior impairment: comorbidity or specific profile? Child. Aust. 10:1356. doi: 10.3390/children10081356

de López, J., Kristine, M., Lyons, R., Novogrodsky, R., Baena, S., Feilberg, J., et al. (2021). Cross-country parental perspectives of LDs. ASHA journals. Journal contribution. doi: 10.23641/asha.14109881.v1

Ebbels, S. H., McCartney, E., Slonims, V., Dockrell, J. E., and Norbury, C. F. (2019). Evidence-pathways to intervention for children with language disorders. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 54, 3–19. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12387

Education Act. (2024). Lov om grunnskoleopplæringa og den vidaregåande opplæringa (opplæringslova). (LOV-2024-03-08-9). Lovdata. Available at: |https://lovdata.no/dokument/LTI/lov/2023-06-09-30

Eriksen, E. (2019). Prinsippet om barn(et)s beste i barnehage(kon)tekster UiT Norges arktiske universitet]. UiT Norges arktiske universitet. Available at: https://munin.uit.no/bitstream/handle/10037/19835/thesis.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

Eriksen, E., and Germeten, S. (2012). Barnevern i barnehage og skole: møte mellom barn, foreldre og profesjoner. Cappelen Damm akademisk.

Fylling, I. (1998). Forvaltningsregime og skolepraksis. Tildeling og bruk av ressurser i grunnskolens spesialundervisning. Spesialpedagogikk 6, 3–11.

Gallagher, A. L., Murphy, C. A., Conway, P., and Perry, A. (2019). Consequential differences in perspectives and practices concerning children with developmental language disorders: an integrative review. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 54, 529–552. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12469

Glover, A., McCormack, J., and Smith-Tamaray, M. (2015). Collaboration between teachers and speech and language therapists: services for primary school children with speech, language and communication needs. Child Language Teach. Therapy 31, 363–382. doi: 10.1177/0265659015603779

Gomez, R., Chen, W., and Houghton, S. (2023). Differences between DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 revisions of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a commentary on implications and opportunities. World J. Psychiatry 13, 138–143. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v13.i5.138

Hagen, Å. M., Melby‐Lervåg, M., and Lervåg, A. (2017). Improving language comprehension in preschool children with language difficulties: A cluster randomized trial. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 58, 1132–1140.

Haug, P. (2021). Inclusion in Norwegian schools: Pupils\u0027 experiences of their learning environment. In Policy, provision and practice for Special Educational Needs and Disability. (Routledge), 103–119.

Hulme, C., Snowling, M. J., West, G., Lervåg, A., and Melby-Lervåg, M. (2020). Children’s language skills can be improved: lessons from psychological science for educational policy. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 29, 372–377. doi: 10.1177/0963721420923684

Iacono, T., Goldbart, J., Douglas, S. N., and Garcia-Melgar, A. (2022). A scoping review and appraisal of AAC research in inclusive school settings. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 34, 963–985. doi: 10.1007/s10882-022-09835-y

Kawsar, M. D. S., Yilanli, M., and Marwaha, R. (2023). School refusal. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls publishing.

Kearney, C. A., and Albano, A. M. (2004). The functional profiles of school refusal behavior. Diagnostic aspects. Behav Modif. 28, 147–161. doi: 10.1177/0145445503259263

Keles, S., Ten Braak, D., and Munthe, E. (2022). Inclusion of students with special education needs in Nordic countries: a systematic scoping review. Scand. J. Educ. Res., 68, 431–434. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2022.2148277

Krishnan, S., Asaridou, S. S., Cler, G. J., Smith, H. J., Willis, H. E., Healy, M. P., et al. (2021). Functional organisation for verb generation in children with developmental language disorder. NeuroImage 226:117599. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117599

Kristoffersen, K.E., Rygvold, A-L, Klem, M., Valand, S.B., Asbjørnsen, A., and Næss, K-A. (2021). Terminologi for vansker med språk hos barn og unge – en konsensusstudie. Norsk tidsskrift for logopedi 3/2001, s. 6–23.

Law, J., Levickis, P., Rodríguez-Ortiz, I. R., Matić, A., Lyons, R., Messarra, C., et al. (2019b). Working with the parents and families of children with developmental language disorders: An international perspective. J. Commun. Disord. 82:105922. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2019.105922

Law, J., McKean, C., and Murphy, C. A. (2019a). Managing children with developmental language disorder: Theory and practice across Europe and beyond. Routledge.

Leonard, L. B. (2014). Children with specific language impairment and their contribution to the study of language development. J. Child Lang. 41, 38–47.

Lingenfelter, N., and Hartung, S. (2015). School refusal behavior. NASN Sch. Nurse 30, 269–273. doi: 10.1177/1942602X15570115

Matson, J. L., and Goldin, R. L. (2013). Comorbidity and autism: trends, topics and future directions. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 7, 1228–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2013.07.003

Ministry of Education and Research. (2019). Kunnskapsdepartementet. Meld. St. 6(2019–2020). Tett på - tidlig innsats og inkluderende fellesskap i barnehage,skole og SFO. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld.-st.-6-20192020/id2677025/?ch=10

Norbury, C. F., Gooch, D., Wray, C., Baird, G., Charman, T., Simonoff, E., et al. (2016). The impact of nonverbal ability on prevalence and clinical presentation of language disorder: evidence from a population study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 57, 1247–1257. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12573

Nordahl, T., Persson, B., Dyssegaard, C. B., Hennestad, B. W., Wang, M. V., Martinsen, J., et al. (2018). Inkluderende fellesskap for barn og unge. Fagbokforlaget.

Østvik, J., Ytterhus, B., and Balandin, S. (2017). Friendship between children using augmentative and alternative communication and peers: a systematic literature review. J. Intellect. Develop. Disabil. 42, 403–415. doi: 10.3109/13668250.2016.1247949

Schaeffer, J., Abd El-Raziq, M., Castroviejo, E., Durrleman, S., Ferré, S., Grama, I., et al. (2023). Language in autism: domains, profiles and co-occurring conditions. J. Neural Transm. 130, 433–457.

Snijders Blok, L., Vino, A., Den Hoed, J., Underhill, H. R., Monteil, D., Li, H., et al. (2021). Heterozygous variants that disturb the transcriptional repressor activity of FOXP4 cause a developmental disorder with speech/language delays and multiple congenital abnormalities. Genet. Med. 23, 534–542. doi: 10.1038/s41436-020-01016-6

Snowling, M. J., Hayiou-Thomas, M. E., Nash, H. M., and Hulme, C. (2020). Dyslexia and developmental language disorder: comorbid disorders with distinct effects on reading comprehension. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 61, 672–680. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13140

Snowling, M. J., Moll, K., and Hulme, C. (2021). Language difficulties are a shared risk factor for both reading disorder and mathematics disorder. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 202:105009. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2020.105009

Solli, K.-A. (2010). Inkludering og spesialpedagogiske tiltak - motsetninger eller to sider av samme sak? Tidsskriftet FoU i praksis 4, 27–45.

Statped. (2021). Hva er alternativ og supplerende kommunikasjon (ASK)?. Available at: https://www.statped.no/ask/hva-er-alternativ-og-supplerende-kommunikasjon-ask/ (Accessed May 21, 2024).

Stehle Wallace, E., Senter, R., Peterson, N., Dunn, K. T., and Chow, J. (2022). How to establish a language-rich environment through a collaborative SLP–teacher partnership. Teach. Except. Child. 54, 166–176. doi: 10.1177/0040059921990690

Tarvainen, S., Launonen, K., and Stolt, S. (2021). Oral language comprehension interventions in school-age children and adolescents with developmental language disorder: a systematic scoping review. Autism & developmental language impairments 6:239694152110104. doi: 10.1177/23969415211010423

The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training (2017). [Utdanningsdirektoratet] Veiledning til bruka av barnekonvensjonen i saksbehandlingen. Available at: https://www.udir.no/globalassets/filer/regelverk/rundskriv/veiledning-til-bruk-av-barnekonvensjonen.pdf (Accessed May 12, 2024).

The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training (2021). [Utdanningsdirektoratet.] Veilederen Spesialundervisning. Available at: https://www.udir.no/laring-og-trivsel/spesialpedagogikk/spesialundervisning/Spesialundervisning/ (Accessed May 12, 2024).

The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training (2022). [Utdanningsdirektoratet] Fakta om grunnskolen 2022-2023. Available at: https://www.udir.no/tall-og-forskning/statistikk/statistikk-grunnskole/analyser/fakta-om-grunnskolen/ (Accessed May 12, 2024).

Throneburg, R. N., Calvert, L. K., Sturm, J. J., Paramboukas, A. A., and Paul, P. J. (2000). A comparison of service delivery models: effects on curricular vocabulary skills in the school setting. Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 9, 10–20. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360.0901.10

Torkildsen, J. K., Tamnes, C. K., Karlsen, J., Hjetland, H. N., Hagtvet, B. E., Braeken, J., et al. (2021). The concurrent and longitudinal relationship between narrative skills and other language skills in children. First Lang. 41, 555–572. doi: 10.1177/0142723721995688

UNESCO. (1994). The Salamanca Statement and Framework for action on special needs education: adopted by the World Conference on Special Needs Education; Access and Quality. Salamanca, Spain: Unesco.

Wendelborg (2015). Barnehagetilbudet til barn med særlige behov. Undersøkelse av tilbudet til barn med særlige behov under opplæringspliktig alder. Available at: https://samforsk.brage.unit.no/samforsk-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/2373848/Barnehagetilbudet%2btil%2bbarn%2bmed%2bs%25C3%25A6rlige%2bbehov%2b-WEB.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y (Accessed May 12, 2024).

Keywords: language disorders, school, communication, inclusion, children

Citation: Chahboun S, Wahl HT, Langner J and Vaags A (2024) Developmental language disorders and special educational needs: consideration of inclusion in the Norwegian school context. Front. Educ. 9:1436298. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1436298

Edited by:

Dionísia Aparecida Cusin Lamônica, University of São Paulo, BrazilReviewed by:

Debora Maria Befi-Lopes, University of São Paulo, BrazilGrace Cristina Ferreira-Donati, Adastra Desenvolvimento e Comportamento Humano, Brazil

Copyright © 2024 Chahboun, Wahl, Langner and Vaags. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sobh Chahboun, c2NoQGRtbWgubm8=

Sobh Chahboun

Sobh Chahboun Hilde T. Wahl2

Hilde T. Wahl2