- Werklund School of Education, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

Educational networks and knowledge brokering play a critical function in supporting educators to keep abreast of scholarly literature and contemporary research that inform practice and policy in schools and districts. In this article, we leverage a quality use of research-evidence framework within a design-based study to elucidate the pivotal role of knowledge brokering in how teacher leaders utilized research during their participation in a professional learning series. In a survey administered to K-9 teacher leaders in Western Canada at the end of a year-long professional learning series, participants (n = 374/500) provided their reflections about how the series supported their learning. The analysis revealed developments across individual, organizational, and system-level components. A significant contribution of this study is that meaningfully integrated research evidence in professional learning can support teacher leaders’ individual confidence in practice, confidence in collaboration at the school level, confidence in leading professional conversations at the organizational level, and confidence in staying updated with educational research at the system level fostering a culture of support and continuous improvement. Knowledge brokering is a pivotal function of relational professional learning networks and when embedded in design-based professional learning for teacher leaders, this powerful combination can contribute to quality research use and can serve to strengthen the theory-to-practice connections in educational contexts.

1 Introduction

Within the field of education, the mobilization of research insights into practical applications has been a subject of ongoing debate. While some scholars advocate for the potential of educational research to enhance teaching practices (Moss, 2013; Adler and Sfard, 2018; Godfrey and Brown, 2019), criticisms persist regarding the perceived disconnect between research and practice (Burkhardt and Schoenfeld, 2003; McKenney and Reeves, 2019). Others (Coburn et al., 2009) have argued that underpinning this perceived disconnect is an assumption that there is a relatively straight line, a linear pathway, between the research evidence and its intended use. This assumption presupposes that the evidence is clear and available for use in an instrumental manner without the need for interpretation and adaptation needed to assess its suitability for practical application by practitioners.

The processes for locating the appropriate evidence to address the problem-of-practice practitioners may be seeking to address and interpreting that evidence once it has been located are not straightforward (Coburn et al., 2009). To assist educational practitioners to navigate the perceived research-practice gap, requires those who have knowledge of how to mobilize research evidence making it useful for practice. Knowledge brokering stands out as an approach to support practitioners in their desire to create an evidence-based practice. Knowledge brokering is a term often used interchangeably with knowledge mobilization, as Rodway et al. (2021) and Gough et al. (2022) note. Both concepts encapsulate endeavours to disseminate research evidence in such a way that it will impact user’s practice.

Central to this imperative are educational professional learning networks (PLNs). These networks serve as vital conduits for knowledge exchange and collaboration within the educational community. In a participatory culture, where collaboration and shared learning are paramount, PLNs play an integral role in fostering continuous growth and development. According to Brown and Poortman (2018), PLNs encompass any group engaged in collaborative learning beyond their immediate community of practice, with a shared goal of enhancing outcomes for children. These networks offer educators, school leaders, and district leaders with valuable opportunities to interact, collaborate, and learn from peers (Jacobsen, 2006, 2010; Friesen, 2009). Crucially, PLNs also serve as platforms for knowledge brokering, facilitating access to scholarly literature and research insights to inform practice and shape educational policies. In the complex and rapidly evolving landscape of education, characterized by constant advancements and evolving pedagogical paradigms, robust PLNs are indispensable for navigating change and promoting professional growth in teachers and school and district leaders.

An exemplary embodiment of knowledge brokering within a PLN is the Galileo Educational Network Association (GENA). Founded in 1999 as an independent charitable organization, GENA, as a PLN, has emerged as a driving force for innovation and transformation within K-12 education (Paniagua and Istance, 2018). Housed within the Werklund School of Education at the University of Calgary, GENA has amassed over two decades of expertise as a knowledge brokering organization, spearheading initiatives aimed at improving and enhancing teaching and leadership practices, fostering evidence-informed practices, and facilitating collaborative engagement among teachers, school leaders, and district administrators. Described by Jacobsen (2010) as a “participatory learning ecosystem” and an exemplar of “research and images of practice for 21st-century learning, teaching, and leading” (p. 16), GENA operates as a relational PLN that has cultivated successful partnerships with a diverse array of educational organizations.

GENA’s impact transcends institutional boundaries, as evidenced by its collaborations with a diverse array of educational organizations both locally and internationally. Through its commitment to advancing leadership and learning, GENA has engaged in collaborative efforts with partners and embraced participatory forms of research and professional learning (Friesen and Brown, 2023). As researchers working with GENA, we have studied the ways GENA empowers district and school leaders, new teachers, teacher-leaders, and classroom educators, to cultivate a culture of innovation and improvement (Brown et al., 2020; Friesen and Brown, 2022b, 2023). This dedication to innovation garnered international recognition in 2018 when the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) acknowledged GENA as one of four comprehensive and complex learning networks dedicated to designing and promoting innovative pedagogies for powerful learning through professional learning and research (Paniagua and Istance, 2018).

At the heart of GENA’s approach to knowledge brokering lies design-based professional learning (DBPL). This educational network is known for pioneering a specialized method of DBPL, a process which is a research-informed and inquiry-focused with an iterative learning process encompassing design, enactment, evaluation, and redesign. DPBL initiatives provide a platform for educators to innovate, improve, share, test, and build on each other’s insights (Brown et al., 2020, 2021; Brown and Friesen, 2023, in press; Friesen and Brown, 2021, 2022a,b, 2023) through knowledge creation/building cycles (Scardamalia and Bereiter, 2022), design (Dorst, 2019), and collaborative inquiry (Timperley, 2011; Katz and Dack, 2013). Beginning and ending with teachers’ and leaders’ problems of practice, this innovative, collaborative design process supported by GENA researchers and professional learning consultants encourages the continual improvement of practice.

In this article, we delve into a collaborative partnership between a school district and GENA, examining how participants in DBPL sessions leverage research to enhance their learning and practice. Our investigation sheds light on how GENA’s leadership during the DBPL sessions empowers teacher-leaders to embrace evidence-based practices. Drawing upon empirical evidence from research involving teacher-leaders in K-9 schools, we underscore the crucial role of relational PLNs in facilitating knowledge exchange through DBPL. Furthermore, we explore the potential implications of these findings for driving policy and systemic changes in education.

Embedded within our inquiry is the application of a research-evidence framework developed by Rickinson et al. (2022), situated within a design-based study (McKenney and Reeves, 2019). This framework serves as a guiding lens through which we examine the dynamic interplay of knowledge brokering during iterative cycles of DBPL for teacher leaders. These teachers were selected to assume a leadership role in supporting instructional leadership by instructional improvement through leading professional learning and providing support to individual teachers in their respective schools. Within the school district, teachers in this role were called teacher leaders. They remained teachers with their own classrooms and were provided with time to carry out the work of mentoring and leading colleagues. These cycles, facilitated collaboratively by researchers and professional learning consultants from GENA and the school district, prioritize the integration of various forms of evidence, including insights from practice and research findings. Notably, we emphasize the pivotal role of knowledge brokering—a multifaceted process encompassing mediation, boundary-spanning, and bridging efforts—in disseminating and applying research insights within educational contexts, as observed in organizations like GENA (Rycroft-Smith, 2022).

Our purpose is to shed light on the effectiveness and implications of DBPL interventions in enriching teacher-leaders’ professional learning and practice. Guiding our inquiry in this paper is the following research question: How do teacher leaders utilize research within DBPL, supported by knowledge brokering initiatives according to Rickinson et al.’s (2022) Quality of Research Evidence Framework, to enhance their professional learning and practice?

2 Literature

The following literature helped inform our study about how advancing knowledge brokering as part of a professional learning model can support educational communities with the quality use of research. In the literature review we discuss the role of knowledge brokering and relational networks in professional learning.

2.1 Knowledge brokering

Knowledge brokering is a phrase that is not well defined and often used interchangeably with terms, such as knowledge mobilisation, knowledge translation, evidence-informed practice (Cooper, 2014; Malin and Brown, 2020; Gough et al., 2022; Rycroft-Smith, 2022). These terms are used inconsistently in the literature (Rodway et al., 2021) and some argue the terms should be reconciled under knowledge brokering (Rycroft-Smith, 2022). Sharples and Sheard (2015) contend that knowledge brokering transcends the simple dissemination of research findings; it involves a profound transformation of knowledge itself. Mosher et al. (2014) delve into this aspect, conceptualizing knowledge brokering as a dynamic process of collaborative entanglement. They highlight the intentional collision and interplay of diverse expertise and perspectives, challenging the traditional hierarchies of knowledge and knowers within educational contexts. This is consistent with Rycroft-Smith’s (2022) review of the literature, which noted that knowledge brokering in education can be characterized as “a process of transforming knowledge from research into practice by crossing or spanning boundaries” (p. 20).

Despite this terminological ambiguity, a common thread emerges; knowledge brokering involves the transformation of research knowledge into actionable practices by transcending boundaries (MacKillop et al., 2020; Rycroft-Smith, 2022). MacKillop et al. (2020) provided the following definition of knowledge brokering illustrating the important relationship between researchers and practitioners for action and change:

All activity that links decision makers with researcher, facilitating their interaction so that they are able to better understand each other’s goals and professional cultures, influence each other’s work, forge new partnerships, and promote the use of research-based evidence in decision-making. (p. 339).

There appears to be agreement that knowledge brokering in education entails not only the dissemination and transformation of research knowledge but also the cultivation of collaborative relationships and the empowerment of stakeholders to enact meaningful change. Through this holistic understanding, the true potential of knowledge brokering as a catalyst for educational improvement and innovation can be realized.

Cooper et al. (2020) highlight the ongoing discourse surrounding the roles and competencies essential for effective knowledge brokering, a discussion intricately tied to delineating its scope and devising evaluative methodologies. We argue that successful knowledge brokers necessitate a profound grasp of the educational landscape, encompassing both research and practical dimensions [as illuminated in Friesen’s (2022) discourse on pracademics] alongside insights into policy frameworks as articulated by Rycroft-Smith (2022).

Five fundamental traits characterize effective knowledge brokers: a nuanced understanding of research methodologies, a comprehensive grasp of the scholarly literature, a proven track record spanning academia and practice, adept interpersonal skills, and the capacity to distill complex information into accessible materials for end-users (Cooper, 2012). However, it is crucial to recognize that knowledge brokering is more than simply providing a research synopsis to practitioners (Sharples and Sheard, 2015). For instance, Gorard et al. (2020) found limited evidence supporting the effectiveness of teachers functioning as knowledge brokers (research leads) concerning student achievement. Interpersonal dynamics and social contexts play pivotal roles in educational knowledge brokering, often manifesting through mediation, boundary-spanning, and bridging efforts (Rycroft-Smith, 2022). As Rycroft-Smith (2022) elucidates, “one undeniable aspect is that knowledge brokering entails design across various levels” (p. 40). This burgeoning field demands further exploration, particularly regarding the evaluation of knowledge brokering initiatives in educational settings. Recognizing this imperative, Paniagua and Istance (2018) identified promising networks like GENA that effectively facilitate knowledge brokering and research dissemination within teacher and leader professional learning contexts in ways that support teachers and leaders to utilize research within their learning and practice.

2.2 Relational professional learning networks

Professional learning networks engage in networked learning activity and play a central role in fostering innovative pedagogies supported by research evidence (Paniagua and Istance, 2018). Networked learning can emerge from the relational work in professional learning contexts referred to by various terms, such as research-practice partnerships (Coburn et al., 2013; Penuel and Gallagher, 2017; Friesen and Brown, 2023), communities of practice (Lave and Wenger, 1991; Wenger, 1998, 2000), professional learning communities (Stoll et al., 2006), professional learning networks (Brown and Poortman, 2018), networked communities (Bryk et al., 2011), knowledge building communities with international partnerships (Chan et al., 2020), and tripartite partnerships between schools, universities, governments (Laferrière et al., 2010; Brown et al., 2021), to name a few. Regardless of the specific name associated with the networked learning activity, a common feature is that it is a relational activity (Rycroft-Smith, 2022). The NLEC (2021) provided the following description of networked learning that emphasizes the importance of human relationships and connections:

Networked learning involves processes of collaborative, co-operative and collective inquiry, knowledge creation and knowledgeable action, underpinned by trusting relationship, motivated by a sense of shared challenge and enabled by convivial technologies. Networked learning promotes connections: between people, between sites of learning and action, between ideas, resources and solutions, across time, space and media. (p. 319)

For example, communities of practice are relational and learning occurs through interactions and knowledge sharing among members of the community (Lave and Wenger, 1991). In research-practice partnerships with schools, literature-informed pedagogical approaches are shared with teachers and interactions are driven by collaboratively designed research projects and shared goals (Friesen and Brown, 2023). As noted by Paniagua and Istance (2018) in the OECD report, Teachers as Designers of Learning Environments, “Strategic partnerships with universities and rigorous continuous professional development programmes provide teachers with opportunities to learn and reflect with their colleagues, and also to coordinate and improve their innovative practices” (p. 30). Relational work in professional learning networks and interpersonal processes and connections are necessary for educators to meaningfully engage with research evidence (Rickinson et al., 2022).

Professional learning networks of schools are found world-wide with an aim to provide professional development for educators (Paniagua and Istance, 2018). For example, GENA is a professional learning network that has created and used DBPL in its commitment to knowledge brokering through continuous professional learning (Brown et al., 2020, 2021; Friesen and Brown, 2022a,b, 2023). Common characteristics are used to describe professional learning networks, such as mutual engagement, joint enterprise, shared repertoire (Wenger, 2000), trust (Stoll et al., 2006), knowledge building (Laferrière et al., 2010; Chan et al., 2020; Brown et al., 2021), and using networked digital technologies to foster collaboration and knowledge building (Brown et al., 2021). Despite the positive characteristics and benefits in establishing professional learning networks, there are also factors that can limit growth and sustainability such as, funding, time, insufficient dynamism, commitment, and buy-in (Paniagua and Istance, 2018).

There is a growing call to understand the implications of networked learning activities (Corbett, 2023). One such implication is that a professional learning network can help broker knowledge and bridge research evidence with practice in education to support teaching and learning in schools. Cooper (2014) described eight major functions of research brokering organizations in Canada (p. 47):

• Linkage and partnerships – facilitate connections among diverse stakeholders and supporting collaboration.

• Awareness – increasing awareness of empirical evidence on a topic.

• Accessibility – increasing accessibility to research by tailoring products to particular audiences.

• Engagement – increasing engagement with research content through making it appeal to more of our senses.

• Capacity building – facilitating professional learning and skill development around KMb

• Implementation support – consulting to provide assistance to implement KMb initiatives.

• Organizational development – assisting to build strategic KMb plans and processes or evaluating existing programs and practices.

• Policy influence – using research to galvanize policy priorities or change.

Implementing the functions of research brokering organizations and advancing knowledge creation through research partnerships and relational networks can support educational communities with quality use of research (Brown et al., 2021). However, more research is needed to understand knowledge brokering initiatives (Cooper, 2014). Our study helps fill this gap and serves to contribute to understanding about how knowledge brokering initiatives in a relational professional learning network enriches teacher professional learning and practice.

2.3 The role of relational professional learning networks in building teachers’ self-confidence

Currently, there is a paucity of educational literature explaining what confidence entails or how it can be fostered (MacLellan, 2014). The literature on teacher confidence within relational professional learning networks is just emerging. However, Trust et al. (2016), Prenger et al. (2021), and Friesen and Brown (2022b) have reported on the positive impacts of these networks on teacher confidence. Additionally, Timperley and Twyford (2022) discusses the role of relational professional learning networks in fostering adaptive expertise among teachers.

Relational professional learning networks are vital in fostering teacher self-confidence. These networks provide emotional support, enhance domain knowledge, and offer a platform for reflective practice (Trust et al., 2016; Prenger et al., 2021; Friesen and Brown, 2022a,b). Through collaboration and shared experiences, educators can engage more deeply with their professional learning, enabling them to apply their learning to improve educational outcomes (Campbell et al., 2016; Prenger et al., 2021; Friesen and Brown, 2022a,b, 2023).

Le Fevre et al. (2020) emphasizes that effective professional learning should change both leader and teacher practices in ways that positively impact student achievement, engagement, and well-being. This approach, termed continuing professional learning, shifts the focus from an adult-centered to a student-centered evaluation of professional learning. Within these forms of professional learning, teachers collaboratively examine evidence of student needs, design instructional strategies, and enact these interventions to address students’ learning needs. Relevant evidence is found in the practices of teachers, the responses of their students, and the artifacts they produce (Le Fevre et al., 2020). Design-based professional learning created by GENA addresses the key features of continuing professional learning noted by Le Fevre et al. (2020), Brown et al. (2020), and Friesen and Brown (2022a,b, 2023).

Research is emerging highlighting the important role relational professional learning networks play in fostering teacher confidence. They provide the necessary support structures for emotional wellbeing, domain knowledge enhancement, and reflective practice. This comprehensive support enables teachers to engage more fully with effective professional learning such as DBPL and apply their learning to enhance educational outcomes.

2.4 Quality use of research evidence framework

Research evidence is generally described as quality research products that follow standards and are considered reliable or trustworthy. For example, the Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA) (2023) developed in 2012, and now a worldwide initiative for improving understanding and evaluation of scholarly outputs, supports using a variety of outputs and criteria for evaluating the research evidence. Rickinson et al. (2022) contend that “while there is well-developed literature around understanding and appraising the quality of research” (p. 134), the process of utilizing and integrating quality research in practice is less understood.

The Quality Use of Research Evidence (QURE) framework provides a valuable conceptualization of what quality use of research evidence means in relation to education and can be used to understand approaches for quality use of research evidence in education (Rickinson et al., 2022). The QURE framework was informed by a cross-sector systematic review and narrative synthesis of 112 publications across four disciplines: health, social care, education, and policy. The authors define quality use of research evidence in education as follows: “the thoughtful engagement with and implementation of appropriate research evidence, supported by a blend of individual and organizational enabling components within a complex system” (Rickinson et al., 2022, p. 141).

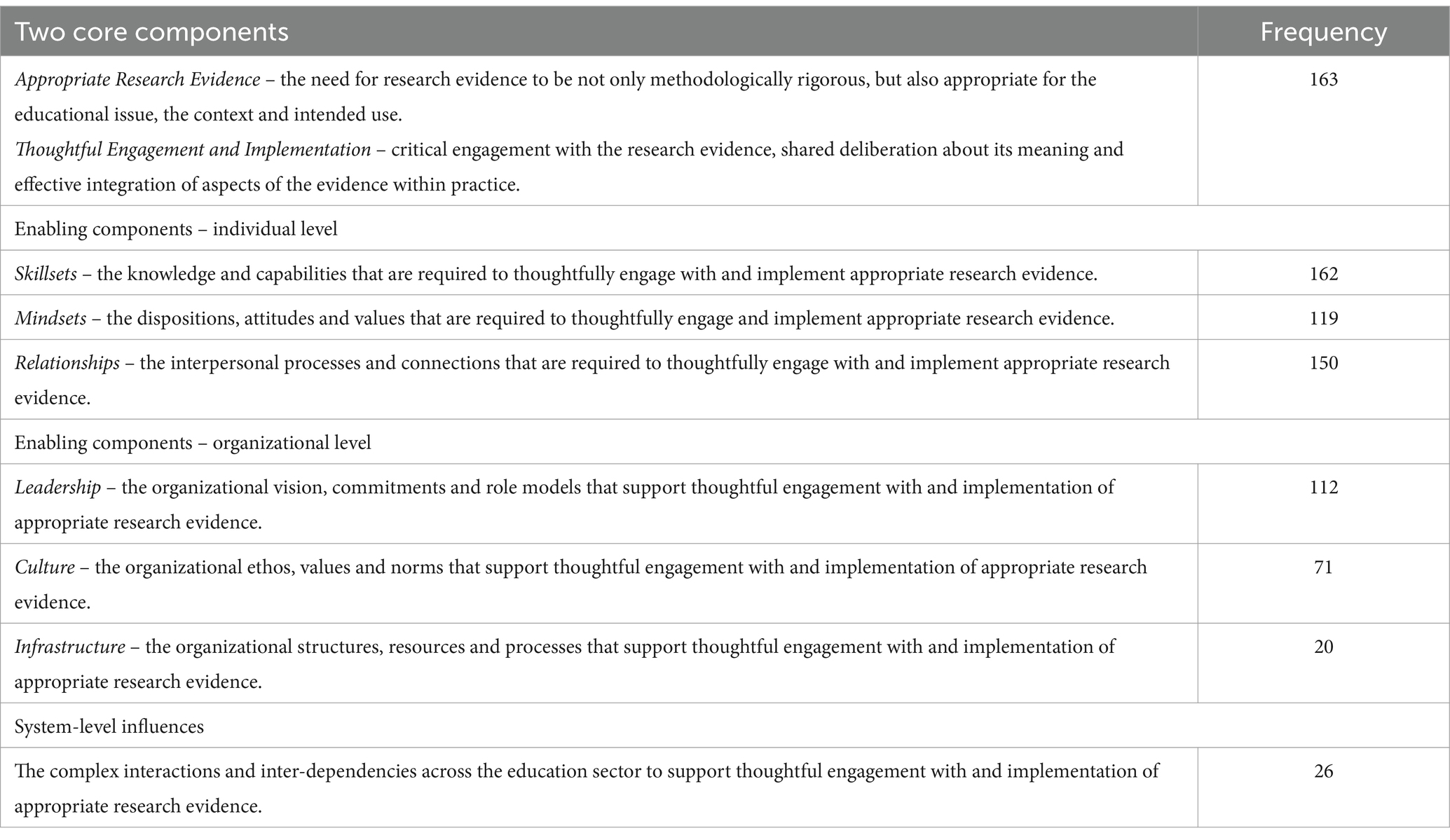

At the heart of the QURE framework lie two core components: the selection of quality research evidence and the thoughtful engagement and implementation of this evidence as shown in Figure 1. This conceptualization underscores the importance of not only accessing high-quality research but also actively engaging with it in practice. Furthermore, QURE identifies enabling components at both individual and organizational levels that facilitate quality use of research evidence. Enabling components of quality evidence at an individual level include skillsets, mindsets, and relationships. Enabling components at the organizational level are shaped by system-level influences and include leadership, culture, and infrastructure.

Figure 1. Quality use of research evidence framework visual (Rickinson et al., 2022). Note: Version reproduced with permission.

QURE recognizes the need for flexibility and adaptability in the utilization of research evidence. Education contexts vary widely, and what constitutes “appropriate” evidence to bring forward for use may differ based on factors such as student demographics, curriculum goals, and available resources. The framework encourages practitioners to critically assess research evidence in relation to their specific context and needs. Moreover, QURE promotes a culture of continuous improvement in evidence-based practice. It acknowledges that effective use of research evidence requires ongoing reflection, learning, and refinement of approaches. Practitioners are encouraged to engage in continuing professional learning, collaborate with colleagues, and stay abreast of emerging research findings to enhance their use of evidence over time.

In addition to its focus on individual and organizational enabling components, QURE emphasizes the importance of equity and inclusion in the utilization of research evidence. It encourages practitioners to consider how research findings may impact diverse student populations and to actively address issues of access, representation, and cultural relevance in their evidence-based practices. By promoting an inclusive approach to evidence use, QURE aims to enhance educational outcomes for all learners. Furthermore, the QURE framework highlights the value of collaboration and knowledge sharing among stakeholders within the education ecosystem. It encourages partnerships between researchers, educators, policymakers, and other relevant stakeholders to foster a collective understanding of research evidence and its implications for practice. By facilitating collaboration and knowledge exchange, QURE seeks to bridge the gap between research and practice and promote evidence-informed decision-making at all levels of the education system.

3 Materials and methods

In this article, we employ a research-evidence framework (Rickinson et al., 2022) within a design-based study (McKenney and Reeves, 2019) to delve into the dynamic interplay of knowledge brokering during iterative cycles of DBPL for teacher leaders. These cycles were facilitated by a collaborative effort involving researchers and consultants from GENA alongside consultants from the school district. DBPL, renowned for its potential as a professional learning intervention, underscores the importance of integrating diverse forms of evidence, including practice-based insights and research findings (McKenney and Reeves, 2019). Of particular interest in our investigation is the pivotal role of knowledge brokering—a multifaceted process that encompasses mediation, boundary-spanning, and bridging efforts in disseminating and applying research insights within educational contexts (Rycroft-Smith, 2022). We asked the teacher leaders to respond to two open-ended questions: 1. In what ways has the professional learning series supported your learning? 2. In what ways has attending these sessions prepared you for leadership?

Neither of these questions asked the teacher leaders to respond explicitly to the research evidence that was used in the professional learning sessions. In designing the questions we were interested in determining the effectiveness of the professional learning is supporting the teacher leaders’ efforts to improve their own practice and of their colleagues. In reading through their comments, we were amazed at how many of the participants referred to the ways they used the research that was used in the sessions. Those that did not mention the research that was used, also did not make any comments about the research.

There were no comments made that the research that was used did not support their practice. Rather, participants spoke about other aspects of the learning series. The absence of negative comments might be attributed to the specific focus of our questions, which did not prompt participants to critique the research evidence directly. Upon an initial review of the comments, we decided to conduct a thorough analysis of the questionnaire comments using Rickinson et al. (2022) QURE framework to understand how teacher leaders in informal roles within a large urban school district interacted with research within the DBPL series. This interaction, bolstered by knowledge brokering initiatives, helped illuminate the effectiveness and implications of such interventions in enriching teacher professional learning and practice.

Research ethics approval was granted for this study by the research team through the University research ethics board and through the school district approval process. In a survey that also included an open-ended questionnaire administered to teacher leaders at the end of a year-long professional learning series. All 500 teacher leaders were invited to complete the survey during their final DBPL session. Of these 374 agreed to participate and complete the survey for purposes of this study. The teacher leader participants in the professional learning sessions (n = 374/500) provided their reflections about how the cycles of DBPL supported their learning. The results from the survey have been published (Chu et al., 2022; Friesen and Brown, 2023) and are not included. In this article, we subjected the open-ended questionnaire data to content analysis to determine how teacher leaders utilized research within DBPL, supported by knowledge brokering initiatives and guided by Rickinson et al.’s (2022) QURE framework (see Figure 1), to enhance their professional learning and practice. We used content analysis to analyze and interpret the teacher leaders’ reflections recorded in the open-ended questionnaire. Codes were developed a priori using Rickinson et al.’s (2022) QURE framework. While there are numerous forms of analysis that can be used to accomplish this, what sets content analysis apart from other forms of analysis is its unique focus on “making replicable and valid inferences from texts (or other meaningful matter) to the contexts of their use” (Krippendorff, 2019, p. 24). In our study, we utilized content analysis to analyze the content of 374 open-ended reflective responses in the questionnaires.

All 374 participant responses were imported into NVivo for analysis. The responses were coded according to the QURE framework outlined by Rickinson et al. (2022) (see Figure 1). We combined the first two core components, the selection of quality research evidence and the thoughtful engagement and implementation of this evidence, into a single code, recognizing their interconnected nature and mutual reinforcement. For the enabling components at the individual level, we utilized codes representing skillsets, mindsets, and relationships. Similarly, organizational components were coded based on leadership, culture, and infrastructure. Additionally, we analyzed the data considering system-level influences. Subsequently, we grouped and organized the coded data to identify relationships and patterns.

4 Results

While 374 participants completed the survey, 285 participant open-ended reflective responses directly addressed one or more of the core or enabling components of QURE. We found this quite remarkable as this was an open-ended response to the professional learning series. Participants were not asked about the QURE framework; however, our analysis indicates that many participant comments aligned with the components of quality use of research evidence in education (QURE). Table 1 provides the frequency of the number of participants who discussed research in relationship to the components in QURE.

In the following section, we address the central inquiry of this study: How do teacher leaders utilize research within DBPL, supported by knowledge brokering initiatives according to Rickinson et al.’s (2022) Quality of Research Evidence Framework, to enhance their professional learning and practice? To illuminate each facet of this inquiry, we present carefully chosen excerpts from participant open-ended reflective responses, each offering detailed insights into specific components. Participants’ responses are identified by an “S” (survey respondent) followed by a unique numerical identifier.

4.1 Core components

Data analysis uncovered a dedication among participants to integrate quality research evidence into their professional practice within the context of DBPL. Participants consistently emphasized the importance of incorporating “current research-based practices” and “research evidence” to enhance their instructional coaching work and teaching practice. This highlights their recognition of the value of methodologically rigorous evidence that directly addresses educational challenges. Moreover, participants demonstrated a keen understanding of the need for evidence to be contextually relevant and aligned with their intended use, as evidenced by their emphasis on integrating current research and research-based design frameworks into their practice.

Their commitment to integrating research evidence for practical application was further evident in their acknowledgment of the research’s suitability for DBPL sessions and its relevance for dissemination with colleagues. For instance, participant S15 highlighted the role of GENA’s consultants in providing a “curated bibliography of exemplary research to bring back to my colleagues.” This sentiment was echoed by others who found the research both theoretically informative and pragmatically useful, as S182 articulated, the sessions “provided theory and background to work and practical tools to use to work with colleagues in improving teaching and learning.” The timeliness of the research evidence was also noted as critical, with participant S248 appreciating, “the professional learning around the most current research” and the practical application through “homework” assignments that enhanced learning within their PLC. Additionally, participants recognized the pedagogical robustness of the selected research literature, with S281 valuing the integration of current research literature with pedagogically sound practices which enriched their professional learning repository.

The professional learning series not only enhanced participants’ confidence in leading discussions and teams but also underscored their active engagement with research evidence and its implementation in their roles as learning leaders. Overall, the findings illustrate participants’ commitment to the judicious use of evidence within the educational context, emphasizing the importance of thoughtful engagement and implementation. These findings underscore the necessity for DBPL knowledge brokers to align with the QURE framework’s dual core components, emphasizing the provision of relevant research evidence and its meaningful integration into practice.

4.2 Individual-level enabling components

The analysis of the DBPL series at the individual level revealed significant developments in skillsets, mindsets, and relationships among participants, aligning with Rickinson et al.’s (2022) framework. Participants reported notable enhancements in their application of research to improve and strengthen their teacher leadership practices, emphasizing skill development, mindset evolution, and relationship building. For instance, S21 expressed that their practice improved through exposure to new ideas and previously unknown research: “I improved my practice with new ideas and learning about authors/books/research I was not aware of before the sessions.” Similarly, S32 noted the expansion of their professional skill set: “I further developed my own repertoire of skills to help build teacher capacity related to the design-based research, the teaching effectiveness framework, rich task design, and assessment.” These testimonials highlight tangible improvements resulting from the DBPL sessions, particularly in participants’ application of research to their teaching practices.

Furthermore, the introduction of research by GENA served as a catalyst for challenging assumptions and fostering critical reflection. S24 shared: “I was introduced to current research around formative assessment, leading learning, and best practices. It’s made me challenge some assumptions about my own teaching skills and reflect critically on areas for improvement” (S24). These quotes underscore the impact of research integration within DBPL, prompting participants to engage in critical reflection and adopt evidence-based practices.

The improvement in instructional leadership was underscored by S248, who felt more equipped to guide with research-based strategies, enhancing student engagement and achievement: “I feel that I am better able to provide instructional leadership with research-based strategies. Helping teachers analyze their own practice and take steps toward designing rich, engaging and worthwhile tasks for students will ultimately help improve student achievement.” It was evident that the introduction of research by GENA within the DBPL series not only prompted participants to challenge assumptions and engage in critical reflection but also empowered teacher leaders as instructional leaders with research-based strategies to enhance student engagement and achievement.

A notable shift in mindset was evident as participants re-evaluated their approaches and embraced a designer and collaborator view of instructional leadership. For example, S183 revealed a holistic re-evaluation of their approach:

[DBPL] has encouraged me to re-evaluate my practice, adapt my practice, change my mindset, rethink what I do every day, share new found knowledge with colleagues, communicate the way I plan, work more collaboratively with colleagues and interact with my students and their families in new ways.

Similarly, S338 highlighted the professional learning series’ role in fostering a designer and collaborator view of instructional leaders was also highlighted as shown in the following excerpt:

This series has helped me become more aware of the research behind professional learning and the authors that are influencing the work. I have become a more capable designer of effective tasks, a better collaborator with colleagues and a more skilled facilitator of professional learning. (S338)

These excerpts illustrate participants’ transformation toward a more collaborative and reflective approach to leadership.

Additionally, DBPL presented opportunities for participants to learn and excel in leadership roles such as lead teacher and peer coach, and to network across the district. Participant S51 discussed the development of relationships with colleagues within the district through the DBPL experience, stating:

Through collaboration and conversations with colleagues outside my building, I have developed a stronger system perspective. I have also developed a clearer understanding of effective leadership competencies that would support my work with my colleagues in moving their practice forward. It has also pointed me to educational authors that could provide further professional development for me. (S51)

This highlights the role of DBPL in fostering professional networking and enhancing leadership capacities among participants.

Moreover, participants conveyed an increased confidence in their skills, mindset, and relationships as educators and leaders, stemming from the research-oriented DBPL experience. This sentiment is encapsulated by S4’s reflection: “I feel like I am effectively able to lead a PLC discussion and that I am more knowledgeable about current educational research.” These participant reflections underscore the importance of attitudes and values conducive to engaging with research evidence, as well as the significance of interpersonal processes and connections in educational leadership and teaching practice at the individual level.

Overall, the findings strongly affirm the enabling components of skillsets, mindsets, and relationships, emphasizing the acquisition of knowledge, effective communication, self-reflection, collaboration, and adaptability to research findings. Participant responses underscore the importance of attitudes and values conducive to engaging with research evidence, as well as the significance of interpersonal processes and connections in educational leadership and teaching practice at the individual level.

4.3 Organizational level enabling components

The DBPL series not only facilitated significant individual-level developments in skillsets, mindsets, and relationships among participants but also fostered enabling components at the organizational level within the schools and school district, particularly in leadership. Through the integration of research-based strategies and collaborative learning experiences, participants reported heightened confidence in their roles as educators and leaders. This structured approach to leadership within schools was underscored by participant S26, who remarked, “…provided intentional learning opportunities focused on best practices based on current research. The homework created a guided process in leading evidence-based conversations in my own school” (S26). Moreover, leadership effectiveness was further bolstered by the alignment of research with school and district goals, as articulated by S78:

This series has supported me in planning for teacher learning at my school. I am better able to link research to the work we are taking up at school and to invite teachers to consider their work differently than they have before. This has increased my capacity to help plan school goals and how we can organize to help bring teachers to their next step.

These insights from participants highlight not only the nurturing of leadership capabilities but also the fostering of a supportive cultural ethos and the provision of necessary infrastructure for meaningful engagement with research evidence within the organizational context.

The DBPL series played a pivotal role in cultivating a culture of continuous improvement, placing research at the center of educational practice, and nudging it toward becoming a norm within the school district. One participant noted the impact of this focus: “This [DBPL] keeps concepts and new research at the forefront and encourages trying new things until the following meeting” (S70). The emphasis on research was also seen as enhancing educational practice, with S58 observing:

Through deeper investigation of the principles of the TEF [Teaching Effectiveness Framework], strategies to support my coaching practice, PLC protocols, and the most current research and literature in these areas, I have a much stronger understanding backed up by practical experience to impact teacher practice.

From the participants’ perspective, the DBPL series served as a catalyst for advancing a culture of continuous improvement and elevating the role of research in educational practice, ultimately reshaping norms within the school district.

Infrastructure was mentioned as a vital support in this continuous improvement process, providing time and space for critical engagement with research as S71 detailed: “I have been given time to think and converse about sound research and how it applies to my teaching. It has encouraged me to think critically about my practice and to continuously improve.” Furthermore, this infrastructure was seen as instrumental in developing a system wide culture of continuous improvement. S150 expressed appreciation for how research underpins educational values and practices:

Research is key to the WHY of what we implement and what we value. I appreciate having current research brought forward to support the work I do and to push the work forward. These learning series are also helping to create a system wide culture of continuous improvement whereby there is a common language developing. As I create PD for participating teachers, I can build upon the shared experience that is being brought back to many schools. It also helps me to articulate with stakeholders outside of [district], the values we hold.

The recognition of infrastructure as a crucial support in fostering continuous improvement underscores its pivotal role in providing the necessary time and space for engaging with research and promoting critical reflection on teacher leaders’ practices. Moreover, participants indicated this infrastructure contributes significantly to the development of a system-wide culture of continuous improvement, as evidenced by its ability to align educational values and practices with current research findings, ultimately shaping a shared language and fostering collaboration across schools.

Leadership, a cultural shift toward continual improvement, and supportive infrastructure were integral to the DBPL’s success. The components collectively fostered an environment where continuous improvement was not only valued but became expected practice as S165 and S78 articulate: “Has given me a clearer idea of how to support the continuous improvement of teachers in my school. Has shown me the importance of creating a culture where continuous improvement is the norm” (S165) and “the sessions have positively highlighted that the [district] values continuous improvement in its teachers and current research in education. I am very grateful to have participated in this learning series” (S78). The integration of leadership, cultural transformation toward continual improvement, and supportive infrastructure proved instrumental to the success of the DBPL initiatives, establishing an environment where continuous improvement was not only valued but also expected practice, as affirmed by the participants.

The DBPL series played a pivotal role in cultivating a culture of continuous improvement within the school district, embodying the essence of research-driven educational practice. Participants attested to the series’ impact on advancing leadership capabilities, fostering a supportive cultural ethos, and providing the essential infrastructure for engaging with research evidence meaningfully. Notably, the emphasis on leadership, cultural transformation toward continual improvement, and supportive infrastructure collectively established an environment where continuous growth was not only valued but also expected. This integration of components proved instrumental to the success of the DBPL initiatives, instilling a shared commitment to ongoing improvement and driving positive change in educational practices. Through these efforts, the series not only elevated the role of research within the district but also reshaped norms, ultimately contributing to the enhancement of teaching and leading experiences for teacher-leaders.

4.4 System-level influences

The DBPL’s alignment with overarching system goals was readily acknowledged by participants who identified clear interconnections between DBPL activities and system-wide initiatives. The integrative nature of DBPL within the broader system goals, was succinctly captured by S112, who remarked:

The collaborative nature of the sessions and hearing about current research supporting practice helps me see that as a system we are leading this work. It helps me see the overall picture of what is working in the system and beyond our school.

Similarly, S300 highlighted the sessions’ role in providing clarity regarding system priorities: “The sessions have provided me with a clear perspective of the system’s goals for the board.”

Furthermore, participants recognized knowledge brokering within DBPL as a conduit for comprehending the intricacies of the system. S35 likened the sessions to staying attuned to the pulse of academic research on teaching and learning, stating: “These sessions are akin to keeping one’s finger on the pulse of academic research on teaching and learning. Further, knowing what goes on in these sessions provides me with insight into what goes on in system leadership meetings.” The sessions also illuminated the connection between research and strategic decision-making within the district, as articulated by S250: “These sessions have given excellent insight into the research and the researcher names behind many of the decisions made in the [district]. I love knowing and learning.” Overall, the DBPL sessions provided a networked learning opportunity grounded in knowledge brokering and proved instrumental in fostering an understanding of system-level priorities and the research underpinning decision-making processes, thereby supporting the enabling components at both the organizational and individual levels.

5 Discussion

The results of our study resonate with and extend the existing literature on knowledge brokering, relational professional learning networks, and the QURE framework, shedding light on the intricate interplay between these concepts within the context of DBPL.

In examining the results from our research, several key ideas and findings emerge concerning relational professional learning networks, knowledge brokering, and the application of the Quality Use of Research Evidence (QURE) framework within the context of Design-Based Professional Learning (DBPL). The results indicated that using research embedded in the DBPL series contributed to teacher-leaders’ confidence, underscoring the significance of attending to the QURE framework in professional learning. The following statements outline the different levels of confidence experienced by teachers as a result of attending to research evidence for use embedded in the DBPL series. These levels include individual confidence in practice, confidence in collaboration at the school level, confidence in leading professional conversations at the organizational level, and confidence in staying updated with educational research at the system level.

1. (Individual level) Confidence that their practice was research-informed and how this confidence helped with their own teaching practice;

2. (School level) Confidence when working as a collaborator with fellow teacher leaders at the sessions and how this confidence helped develop an expanded professional network of colleagues;

3. (Organizational level) Confidence when returning to their schools following the sessions and leading professional conversations with colleagues and how this confidence helped teacher leaders provide leadership at their respective schools;

4. (System level) Confidence in keeping abreast of educational research and how this became a professional expectation in the district and part of a culture of support and continuous improvement.

Our results also suggest there appears to be overlap of some components in the Rickinson et al. (2022) framework. In particular, participants’ reflections on infrastructure at the organizational level make reference to both the organizational and system levels. There also appears to be an overlap between individual level enabling components and the organizational level enabling components. These overlaps may be because our participants were teacher leaders responsible for leading instructional improvements in their schools. Our observation of the overlaps in Rickinson et al.’s (2022) framework suggests that further research is needed for individuals with teaching and leading responsibilities.

The relational nature of professional learning networks emerged as central in our study, consistent with the principles of communities of practice and networked learning (Lave and Wenger, 1991; Bryk et al., 2011). The central role of the professional learning network should not be underestimated in fostering teachers’ confidence and facilitating collaboration within a broader network, contributing to the development of a culture of support and continuous improvement. Participants described how collaborative interactions within Design-Based Professional Learning (DBPL) sessions facilitated the exchange of knowledge and expertise, fostering a sense of mutual engagement and shared learning. This aligns with the literature highlighting the importance of trust, shared enterprise, and distributed leadership within relational networks (Stoll et al., 2006; Corbett, 2023). Furthermore, our findings suggest that professional learning needs to be purposefully designed by knowledge brokers who not only span and bridge efforts—in disseminating and applying research insights within educational contexts but also have a profound grasp of the educational landscape, encompassing both research and practical dimensions (as illuminated in Friesen’s 2022 discourse on pracademics). Additionally, insights into policy frameworks are crucial for effective knowledge brokerage (Rycroft-Smith, 2022) and identified as one of the functions of research brokering organizations (Cooper, 2014).

The importance of knowledge brokering is underscored by its role in facilitating the integration of research use within practice (Mosher et al., 2014; Rycroft-Smith, 2022). Participants’ recognition of the role of knowledge brokers in providing curated bibliographies of research underscores the significance of intermediary support and initiatives (Cooper, 2014; Gough et al., 2022). This finding resonates with Sharples and Sheard’s (2015) notion that knowledge brokering involves a profound transformation of knowledge itself, emphasizing the collaborative and dynamic nature of the process. Within the context of DBPL, participants demonstrated a significant commitment to integrating quality research evidence into their professional practices (Rickinson et al., 2022). They emphasized the importance of incorporating current research-based practices to enhance instructional coaching work and teaching practices. This commitment was evident in participants’ recognition of the value of methodologically rigorous evidence that directly addresses educational challenges, as well as their understanding of the need for evidence to be contextually relevant and aligned with their intended use. These results align with Rickinson et al. (2022), who indicate that the QURE framework can be seen as an invitation to reflect honestly on current approaches to talking about, enhancing, and practicing evidence use” [italics in original] (p. 145).

At the individual level, participants reported significant developments in skillsets, mindsets, and relationships as a result of participating in the DBPL series. They noted enhancements in their application of research to improve and strengthen their teacher leadership practices, including skill development, mindset evolution, and relationship building. These results align with the principles of networked learning and communities of practice, emphasizing the collaborative nature of professional learning and the importance of shared knowledge and expertise (Lave and Wenger, 1991; Bryk et al., 2011). Furthermore, the role of knowledge brokering in facilitating critical reflection and challenging assumptions among participants highlights the dynamic nature of the learning process, as emphasized by Sharples and Sheard (2015). The introduction of research by knowledge brokers served as a catalyst for challenging assumptions and fostering critical reflection among participants. Participants also reported increased confidence in their skills, mindset, and relationships as educators and leaders, stemming from the research-oriented DBPL experience.

The organizational-level effects of DBPL were also evident, particularly in leadership development and cultural transformation within schools. Through the integration of research-based strategies and collaborative learning experiences, participants reported heightened confidence in their roles as educators and leaders. Participants’ heightened confidence in their roles as educators and leaders underscores the significance of system-level influences in shaping the quality use of research evidence (Rickinson et al., 2022). The professional learning series also played a pivotal role in cultivating a culture of continuous improvement within the school district, placing research at the center of educational practice and reshaping norms within the district. Leadership, cultural transformation toward continual improvement, and supportive infrastructure were integral to the success of the DBPL initiatives, establishing an environment where continuous growth was valued and expected. This result is consistent with Rickinson et al. (2022), who indicate, “high quality of use of research evidence does not happen in a vacuum. It is sophisticated work that requires not only professional educators but also supportive organisations and systems” (p. 146). The integration of leadership, cultural transformation, and supportive infrastructure within DBPL initiatives emphasizes the importance of organizational contexts in fostering evidence-informed practice and continuous improvement (Rickinson et al., 2022).

Further, our findings provide empirical support for the components of the QURE framework proposed by Rickinson et al. (2022). The framework offers a comprehensive lens through which to understand the multifaceted nature of the integration of research evidence in educational contexts, encompassing individual, school, organizational, and leadership dimensions. By aligning with the QURE framework, professional learning initiatives can effectively promote the thoughtful engagement and implementation of research evidence, ultimately enhancing educational outcomes.

In summary, our study contributes to a deeper understanding of the complex dynamics at play in DBPL initiatives and their implications for evidence-informed practice in education. At the individual level, participants’ increased confidence in research-informed practice reflects the enabling components of skillsets, mindsets, and relationships. Moreover, the organizational-level effects of DBPL, such as leadership development and cultural transformation, underscore the significance of system-level influences in shaping the quality use of research evidence. Highlighting the importance of relational professional learning networks, knowledge brokering, and the QURE framework, offers a comprehensive lens through which to understand the multifaceted nature of research integration in educational contexts, encompassing the individual, school, organizational, and leadership dimensions. Our results offer valuable insights for practitioners, research brokering organizations, policymakers, and researchers seeking to promote effective professional learning and continuous improvement in educational settings.

6 Conclusion

The results of this study underscore the impact of DBPL in fostering a culture of continuous improvement and the quality use of research evidence in educational settings. Through the lens of the QURE framework, our analysis revealed significant developments across individual, organizational, and system-level components.

At the individual level, participants exhibited enhanced confidence in research-informed practice, reflecting advancements in skillsets, mindsets, and relationships. The DBPL series served as a catalyst for professional growth, empowering educators to integrate current research evidence into their teaching practices and leadership roles. Notably, participants reported expanded professional networks and a shift toward a collaborative and reflective approach to instructional leadership.

Organizational-level effects highlighted the critical role of leadership, cultural ethos, and infrastructure in facilitating the integration of research evidence into educational practice. DBPL initiatives nurtured leadership capabilities fostered a culture of continuous improvement and provided essential support structures for meaningful engagement with research. Leadership emerged as a key driver in aligning research with school objectives and promoting a systemic approach to evidence-based decision-making.

Furthermore, the DBPL series demonstrated alignment with broader system goals, emphasizing the interconnectedness between DBPL activities and district-wide initiatives. Knowledge brokering emerged as a pivotal component, facilitating the dissemination and application of research insights within the educational landscape. By fostering an understanding of system-level priorities and promoting collaborative learning networks, DBPL contributed to a culture of support and continuous improvement across the district.

Overall, the findings highlight the importance of purposefully designed professional learning experiences that prioritize the integration of research evidence and the cultivation of collaborative networks. Moving forward, continued investment in DBPL initiatives and the QURE framework can further advance the quality use of research evidence in education, ultimately enhancing teaching practices, leadership effectiveness, and student outcomes. As educational landscapes evolve, DBPL remains a promising approach to engage in research brokering functions, empower educators and drive positive change within educational systems.

7 Future directions

Moving forward, further research is needed to explore the long-term impacts of DBPL and knowledge brokering initiatives on teacher leaders’ practice and student outcomes. Additionally, refining evaluative methodologies for assessing the quality use of research evidence in education remains a crucial area of investigation. Theoretical implications of our findings warrant deeper exploration, particularly regarding their alignment with existing theories in the field of education. Practically, our results have implications for the design and implementation of professional learning initiatives and policy decisions in educational settings. Overall, this study advances the dialogue on knowledge brokering, relational professional learning networks, and the QURE framework, offering practical insights into how these concepts can be effectively leveraged to enhance teacher leader professional learning and ultimately improve educational outcomes.

8 Limitations

This study primarily focuses on the perspectives and experiences of teacher leader participants directly involved in DBPL in one Canadian school district. While this provides valuable insights into the impact of DBPL on research integration in education, it overlooks the perspectives of other stakeholders such as students and administrators. A more comprehensive assessment involving diverse stakeholders could offer a more nuanced understanding of the program’s effects and its broader implications within the educational ecosystem.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because while the quantitative data could be made available, the qualitative data will not be made available. Anonymity and confidentiality were guaranteed in the research ethics. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to c2ZyaWVzZW5AdWNhbGdhcnkuY2E=.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Conjoint Faculties Ethics Review Board, University of Calgary. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

SF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding supported by the school district for design-based professional learning and research.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the school district and teachers involved in the study and members of the Galileo Educational Network.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adler, J., and Sfard, A. (2018). Research for educational change: Transforming researchers' insights into improvement in mathematics teaching and learning. New York, NY: Routledge.

Brown, B., and Friesen, S. (in press). Teacher leaders’ and school administrators’ interconnecting activity systems: A source of system improvement. in Understanding teacher leadership in education change: An international perspective. Eds. P. Liu and L. Mee (Routledge).

Brown, B., and Friesen, S. (2023). An examination of teacher leaders and a shared leadership approach: Contributions to school improvement in a school district. Asia Paci. J. Educ. Educ. 38, 249–273. doi: 10.21315/apjee2023.38.2.13

Brown, B., Friesen, S., Beck, J., and Roberts, V. (2020). Supporting new teachers as designers of learning. Educ. Sci. 10, 1–14. doi: 10.3390/educsci10080207

Brown, B., Friesen, S., Mosher, R., Chu, M.-W., and Linton, K. (2021). Adapting to a design-based professional learning intervention. EDeR. 5. doi: 10.15460/eder.5.2.1658

Brown, C., and Poortman, C. (Eds.) (2018). Networks for learning: Effective collaboration for teacher, school and system improvement. New York, NY: Routledge.

Bryk, A. S., Gomez, L. M., and Grunow, A. (2011). “Getting ideas into action: building networked improvement communities in education” in Frontiers in sociology of education. ed. M. T. Hallinan (Netherlands: Springer), 127–162.

Burkhardt, H., and Schoenfeld, A. H. (2003). Improving educational research: toward a more useful, more influential, and better-funded enterprise. Educ. Res. 32, 3–14. doi: 10.3102/0013189X032009003

Campbell, C., Osmond-Johnson, P., Faubert, B., Zeichner, K., Hobbs-Johnson, A., Brown, S., et al. (2016). The state of educators’ professional learning in Canada. Oxford, OH: Learning Forward.

Chan, C., Lai, K.-W., Bielzczyc, K., Tan, S.-C., Ma, L., Scardamalia, M., et al. (2020). “Knowledge building/knowledge creation in the school, classroom, and beyond” in Learners and learning contexts: New alignments for the digital age. eds. P. Fisser and M. Phillips, 101–108. Available at: https://edusummit2019.fse.ulaval.ca/files/edusummit2019_ebook.pdf

Chu, M-W, Brown, B, and Friesen, S. (2022). Psychometric properties of the design-based professional learning for teachers survey. Prof. Develop. Educ. 48, 594–610. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2019.1709219

Coburn, C. E., Penuel, W. R., and Geil, K. E. (2013). Research-practice partnerships: A strategy for leveraging research for educational improvement in school districts. Cambridge, MA: William T. Grant Foundation. Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED568396.

Coburn, C., Honig, M., and Stein, M. (2009). “What’s the evidence on districts’ use of evidence?” in The role of research in educational improvement. eds. J. Bransford, D. Stipek, N. J. Vye, L. Gomez, and D. Lam (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Educational Press), 67–86.

Cooper, A. (2014). Knowledge mobilization in education across Canada: a cross-case analysis of 44 research brokering organisations. Evid. Policy 10, 29–59. doi: 10.1332/174426413X662806

Cooper, A.-M. (2012). Knowledge mobilization intermediaries in education: a cross-case analysis of 44 Canadian organizations [thesis]. 1–32. Available at: https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/32688

Cooper, A., Shewchuk, S., and MacGregor, S. (2020). A developmental evaluation of research-practice-partnerships and their impacts. Int. J. Educ. Policy Leadersh. 16, 1–32. doi: 10.22230/ijepl.2020v16n9a967

Corbett, F. C. (2023). Leadership on a blockchain: What Asia can teach us about networked leadership. 1st Edn. New York, NY: Routledge.

Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA) . (2023). Available at: https://sfdora.org/

Friesen, S. (2009). Galileo Educational Network: Creating, researching, and supporting 21st Century Learning, Education Canada, 49, 7–9.

Friesen, S. (2022). Dwelling in liminal spaces: Twin moments of the same reality. Journal of Professional Capital and Community. 7, 71–82. doi: 10.1108/JPCC-11-2020-0095

Friesen, S., and Brown, B. (2021). Advancing knowledge creation in education through tripartite partnerships. Can. J. Lear. Tech. 47. doi: 10.21432/cjlt28052

Friesen, S., and Brown, B. (2022a). Design-based professional learning: A promising approach to continuous professional learning. Inter. J. Lead. Learn. 22, 218–251. doi: 10.29173/ijll10

Friesen, S., and Brown, B. (2022b). Teacher leaders: Developing collective responsibility through design-based professional learning. Teach. Educ. 33, 254–271. doi: 10.1080/10476210.2020.1856805

Friesen, S., and Brown, B. (2023). Engaging in educational research-practice partnerships: Guided strategies and applied case studies for scholars in the field. Routledge.

Godfrey, D., and Brown, C. (Eds.) (2019). An eco-system for research-engaged schools: Reforming education through research. New York, NY: Routledge.

Gorard, S., See, B. H., and Siddiqui, N. (2020). What is the evidence on the best way to get evidence into use in education? Rev. Educ. 8, 570–610. doi: 10.1002/rev3.3200

Gough, D., Maidment, C., and Sharples, J. (2022). Enabling knowledge brokerage intermediaries to be evidence-informed. Evid. Policy 18, 746–760. doi: 10.1332/174426421X16353477842207

Jacobsen, M. (2006). Learning technology in continuing professional development: The Galileo network. Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen Press.

Jacobsen, M. (2010). Teaching in a participatory digital world. Educ. Can. 50, 13–17. Available at: https://www.edcan.ca/articles/teaching-in-a-participatory-digital-world/

Katz, S., and Dack, L. A. (2013). Intentional interruption: Breaking down learning barriers to transform professional practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Krippendorff, K. (2019). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Laferrière, T., Montane, M., Gros, B., Alvarez, I., Bernaus, M., Breuleux, A., et al. (2010). Partnerships for knowledge building: an emerging model. Can. J. Learn. Technol. 36, 1–20. doi: 10.21432/T2R59Z

Lave, J., and Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Le Fevre, D., Timperley, H., Twyford, K., and Ell, F. (2020). Leading powerful professional learning: Responding to complexity with adaptive expertise. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

MacKillop, E., Quarmby, S., and Downe, J. (2020). Does knowledge brokering facilitate evidence-based policy? A review of existing knowledge and an agenda for future research. Policy Polit. 48, 335–353. doi: 10.1332/030557319X15740848311069

MacLellan, E. (2014). How might teachers enable self-confidence? A review study. Educ. Rev. 66, 59–74. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2013.768601

Malin, J., and Brown, C. (2020). The role of knowledge brokers in education: Connecting the dots between research and practice. New York, NY: Routledge.

McKenney, S. E., and Reeves, T. C. (2019). Conducting educational design research. 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Routledge.

Mosher, J., Anucha, U., Appiah, H., and Levesque, S. (2014). From research to action: four theories and their implications for knowledge mobilization. Scholarly Res. Commun. 5, 1–17. doi: 10.22230/src.2014v5n3a161

Moss, G. (2013). Research, policy and knowledge flows in education: what counts as knowledge. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 8, 237–248. doi: 10.1080/21582041.2013.767466

NLEC (2021). Networked learning: inviting redefinition. Postdigital Sci. Educ. 3, 312–325. doi: 10.1007/s42438-020-00167-8

Paniagua, A., and Istance, D. (2018). Teachers as designers of learning environments: The importance of innovative pedagogies. Available at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/teachers-as-designers-of-learning-environments_9789264085374-en

Penuel, W. R., and Gallagher, D. J. (2017). Creating research-practice partnerships in education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Prenger, R., Poortman, C., and Handelzalts, A. (2021). Professional learning networks: from teacher learning to school improvement? J. Educ. Chang. 22, 13–52. doi: 10.1007/s10833-020-09383-2

Rickinson, M., Cirkony, C., Walsh, L., Gleeson, J., Cutler, B., and Salisbury, M. (2022). A framework for understanding the quality of evidence use in education. Educ. Res. 64, 133–158. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2022.2054452

Rodway, J., MacGregor, S., Daly, A., Liou, Y.-H., Yonezawa, S., and Pollock, M. (2021). A network case of knowledge brokering. J. Prof. Cap. Community 6, 148–163. doi: 10.1108/JPCC-11-2020-0089

Rycroft-Smith, L. (2022). Knowledge brokering to bridge the research-practice gap in education: where are we now? Rev. Educ. 10:e3341. doi: 10.1002/rev3.3341

Scardamalia, M., and Bereiter, C. (2022). “Knowledge building and knowledge creation” in The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences. ed. R. K. Sawyer . 3rd ed (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 385–405.

Sharples, J., and Sheard, M. (2015). Developing an evidence-informed support service for schools – reflections on a UK model. Evid. Policy 11, 577–587. doi: 10.1332/174426415X14222958889404

Stoll, L., Bolam, R., McMahon, A., Wallace, M., and Thomas, S. (2006). Professional learning communities: a review of the literature. J. Educ. Chang. 7, 221–258. doi: 10.1007/s10833-006-0001-8

Timperley, H. S. (2011). Realizing the power of professional learning. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

Timperley, H. S., and Twyford, K. (2022). Adaptive expertise in educational leadership: embracing complexity in leading today’s schools. Aust. Educ. Leader 44, 8–12. Available at: https://www.acel.org.au/ACEL/ACELWEB/Publications/AEL/2022/1/Lead_Article_1.aspx

Trust, T., Krutka, D., and Carpenter, J. (2016). “Together we are better”: professional learning networks for teachers. Comput. Educ. 102, 15–34. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2016.06.007

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, xv, 318.

Keywords: evidence-informed, policy and practice, knowledge brokerage, networks, research use, professional learning

Citation: Friesen S and Brown B (2024) Knowledge brokering pivotal in professional learning: quality use of research contributes to teacher-leaders’ confidence. Front. Educ. 9:1430357. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1430357

Edited by:

Elizabeth Farley-Ripple, University of Delaware, United StatesReviewed by:

Simon N. Leonard, University of South Australia, AustraliaJoel Malin, Miami University, United States

Anita Caduff, University of California, San Diego, United States

Copyright © 2024 Friesen and Brown. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sharon Friesen, c2ZyaWVzZW5AdWNhbGdhcnkuY2E=

Sharon Friesen

Sharon Friesen Barbara Brown

Barbara Brown