- 1Educational Leadership and Policy Studies, University of Oklahoma, Tulsa, OK, United States

- 2School of Education, University of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell, MA, United States

Introduction: Two rising innovations in educational leadership development—using an equity lens and facilitating continuous improvement (CI)—depend upon leaders developing conducive mindsets for the work. However, little research has examined how educational leaders come to develop equity-focused CI mindsets. This is important given that countervailing habits of thinking are likely to develop within leaders’ typical work environments. This paper traces the extent to which an Ed.D. program centered around a pedagogy of critical improvement science can foster shifts from typical habits of thinking towards equity-focused CI mindsets.

Methods: Data consisted of 13 assignments and semi-structured interviews of six Ed.D. students participating in two parallel and interconnected courses during their first term. The two courses culminated in a common assessment: a White Paper about their equity-focused problem of practice and how their social identities shaped their understanding and role in addressing the problem. Through coding, analytic memos, and member checking, we traced patterns and shifts in students’ thinking over time around five key domains of learning: problem identification, problem diagnosis, use of evidence, social identity, and equity leadership practices.

Results: We found emergent mindset shifts for all six participants across all learning domains. Students demonstrated new insights about problem analysis and becoming evidence-informed and user-centered, challenging their initial framing of problems through a systems approach to diagnosing problem. These insights intersected with new understandings of their social identities and practices as equity leaders as they reflected on more oppressed and privileged aspects of their identity and wrestled with new understandings that acting as equity leaders would entail disrupting power dynamics and empowering others for collective learning and action.

Discussion: The results reveal the potential of developing equity-focused CI mindsets through leadership programs that intentionally integrate methods of CI with critical analysis of one’s social identity and leadership practices amid systems of oppression.

1 Introduction

Graduate programs have long been criticized for their weak preparation of education leaders to address the critical problems in our educational system (Shulman et al., 2006; Darling-Hammond et al., 2009). Recently, a convergence of movements has opened opportunities for innovation in educational leadership development that holds promise to answer to these criticisms. Following the murder of George Floyd, the rise of the Black Lives Matter Movement, and a political backlash from the right, a movement for racial reckoning has ignited a sense of urgency to emphasize equity in leadership preparation programs (Galloway and Ishimaru, 2015; Stone-Johnson and Hayes, 2021; Young et al., 2021). In parallel, in the face of the disappointing track record of standards-based reform, a movement for continuous improvement (CI) in education has spread methods such as design-based improvement (Penuel et al., 2011; Mintrop, 2016) and improvement science (IS) (Bryk et al., 2015; Hinnant-Crawford, 2020) with the aim to equip educational leaders to act as effective organizational problem solvers.

As scholars increasingly recognize that educational equity depends upon leaders who are both committed to equity and skilled in solving problems, higher education faculty are being called upon to reimagine graduate programs to prepare leaders for equity-focused CI (Hinnant-Crawford, 2020; Eddy-Spicer and Gomez, 2022; Anderson and Davis, 2023; Gomez et al., 2023; Orr and Stosich, 2023). The Carnegie Project on the Education Doctorate (CPED), for example, promotes the transformation of education doctorate programs towards dissertations-in-practice that emphasize a focus on equity and improvement science (Perry et al., 2020) for its over 130 university members.

To productively respond to this call, scholars and program developers must wrestle with a key challenge of preparing leaders for equity-focused CI: how develop conducive mindsets to guide the work (Mintrop and Zumpe, 2019; Yurkofsky et al., 2020; Biag and Sherer, 2021; Sandoval and Van Es, 2021). Mindsets refer to habitual ways of thinking about improvement (Mintrop and Zumpe, 2019). Assuming that mindsets are situated (Brown et al., 1989), the success of equity-focused CI depends upon leaders forging habits of thinking that are counter-normative in educators’ typical work environments (Mintrop and Zumpe, 2019; Biag and Sherer, 2021; Anderson et al., 2023). Developing an equity lens calls upon leaders to adopt a critical perspective and take a stance against injustice (Theoharis, 2009; Gorski and Swalwell, 2015)—while embedded in an institution that has historically been an engine of social reproduction (Giroux, 1983). Becoming continuous improvers calls upon leaders to remedy problems through collaborative cycles of disciplined inquiry, while in a work environment that orients leaders towards quick fixes, top-down decision making, and muddling through (Mintrop and Zumpe, 2019).

If ingrained ways of thinking have arisen from these environments, leaders’ existing mindsets may be far from equity-focused CI. Thus, many leaders may have important learning to do. Scholars have articulated frameworks for what equity-centered leaders should do (Ishimaru and Galloway, 2014; Khalifa et al., 2016) and identified dispositions of “continuous improvers” (Biag and Sherer, 2021). However, little research has traced how mindsets for equity-focused CI develop.

To address this, this paper reports findings from qualitative action research within an online education doctorate program in Massachusetts, in which three of the authors are current or former program faculty. This Ed.D. program follows a signature pedagogy we call “critical improvement science” that integrates IS with a “strong equity” focus (Cochran-Smith and Keefe, 2022, 22). This paper focuses on six doctoral students who are educators in TK-12 contexts and in their first semester of a three-year program. This paper asks: In what ways do leaders in the first term of an Ed.D. program focused on critical IS experience emergent shifts towards mindsets for equity-focused CI?

2 Review of relevant literature

2.1 Conceptualizing mindsets

Mindsets describe habits of thinking (Mintrop and Zumpe, 2019) forged through cumulative learning experiences. Following French (2016), mindsets can be revealed as learners respond to specific cognitive tasks and their responses intersect with general cognitive filters and sets of beliefs. Through the lens of cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957; Fiske and Taylor, 2013) and sociocultural learning theory (Honig, 2008; Knapp, 2008), mindsets form—and can change—through social learning experiences within particular contexts (Brown et al., 1989). As people experience cognitive dissonance from new information or problematic situations, they may resolve the tension by selectively interpreting and appropriating the new information to confirm preexisting understandings. As they access new knowledge through artifacts, scaffolds, and feedback in a community of practice, they may become enabled to learn and change their underlying theories and beliefs (Lave and Wenger, 1991). Initial shifts in understanding do not necessarily sustain; prior understandings may prevail. Thus, sustained shifts in mindsets usually occur in an iterative, and less linear, fashion. New learning may lead to sustained changes in mindsets over time if new beliefs and practices are reinforced through ongoing learning experiences.

2.2 Equity-oriented CI mindsets

Below, we draw on existing research to identify key elements of equity-focused CI mindsets and the learning needs entailed in developing such mindsets, given prevailing ways of thinking invited by education leaders’ typical work environments. Until recently scholars have tended to approach CI or equity in leadership as separate lines of inquiry. Thus, we turn to each body of relevant literature in turn. First, we draw on literature about CI in education and education leaders’ problem-solving and evidence use to identify elements and challenges of developing a CI mindset. Next, we draw on literature about social justice leadership to identify elements and challenges of developing an equity mindset. Finally, we bring these insights together to identify an integrated a set of learning needs for developing equity-focused CI mindsets.

2.2.1 Developing a CI mindset

According to literature about CI in education, leaders with a CI mindset think about improvement as a process of iterative organizational problem solving that involves: (a) identifying and framing an actionable problem of practice; (b) recognizing root causes from a systems perspective; (c) understanding the experiences of the “users,” or the people who directly experience the problem; (d) devising a theory of improvement; (f) designing and implementing intervention to test this theory; and (g) learning from evidence about the process and results to inform next iterations (Bryk et al., 2015; Mintrop, 2016; Eddy-Spicer and Gomez, 2022).

A CI mindset has implications for how leaders identify problems to solve. Leaders with a CI mindset think like expert problem solvers who take the time to identify, define, and frame the problem first before deciding upon solutions to implement (Leithwood and Steinbach, 1995). This is important because the kinds of problems leaders face tend to be highly complex and “ill-structured,” meaning that it is not clear at the outset what exactly the problem is or how to solve it (Robinson, 1993; Jonassen, 2000; Pretz et al., 2003). However, most leaders do not appear to be predisposed to problem analysis. Rather, as they cope with complex organizational demands and fast-paced work environments, many educational leaders appear to think about improvement by first identifying a solution they want to implement (Bryk et al., 2015), showing up in a tendency to frame problems as the “absence of my solution” (Mintrop and Zumpe, 2019, 329).

A CI mindset also has implications for how leaders use evidence. Leaders with a CI mindset orient towards disciplined inquiry, seeking to learn from results (Biag and Sherer, 2021). However, more typically, leaders tend to follow their intuitive assumptions (Mintrop, 2016; Robinson et al., 2021) or “gut feelings” (Biag and Sherer, 2021, 16). When education leaders consult evidence, they tend to do so in confirmatory ways that reinforce their pre-existing assumptions (Farley-Ripple, 2012; Datnow and Park, 2018; Schildkamp, 2019).

Thinking about improvement as a matter of collective and iterative inquiry also has implications for how leaders approach diagnosing problems. Leaders with CI mindsets avoid jumping to conclusions or pointing fingers. Instead, they work to “see the system” (Bryk et al., 2015), or identify root causes at multiple levels of the system (Mintrop, 2016). They also consult and involve users, or the people who most directly experience the problem, in diagnosing the problem (Bryk et al., 2015; Mintrop, 2016). However, systemic and user-centered approaches to problem diagnosis appear far from the habits of thinking invited in leaders’ typical environments. The rise of high-stakes accountability policies in education have tended to orient leaders towards a focus on problems defined and diagnosed for them by external policymakers (Farley-Ripple, 2012; Jennings, 2012; Braaten et al., 2017; Lockton et al., 2020). Often, these are performance problems defined by scores on standardized tests (Schneider, 2017; Weddle, 2022) that tend to come with a ‘baked in’ diagnosis that narrowly locates educational problems in students or teachers.

All of the above has implications for how leaders understand their leadership roles. Leaders with CI mindsets see their role as leaders of learning (Copland and Knapp, 2006; Honig and Rainey, 2020) who engage in engage diverse stakeholders in identifying problems and solutions and seek to learn from the perspectives of others (Biag and Sherer, 2021). More typically, however, education leaders tend to think about their role as managerial, and this orientation has been underscored by high-stakes accountability policies (Trujillo, 2012, 2014; Anderson and Herr, 2015). In this environment, leaders may think about their role in change as telling others what to implement (Mintrop and Zumpe, 2019).

2.2.2 Developing an equity mindset

According to literature about social justice leadership, leaders with an equity mindset are equity literate (Gorski and Swalwell, 2015), harbor a critical consciousness (Jemal, 2017), and are culturally competent and responsive (Khalifa et al., 2016). Equity literate leaders make intentional efforts to recognize and redress systemic bias, discrimination, and inequity by prioritizing problems for the benefit of those currently oppressed or disadvantaged by the system (Gorski and Swalwell, 2015). Leaders with critical consciousness engage in sociopolitical analysis of structural oppression and envision actions to challenge inequities within sociopolitical environments (Diemer and Blustein, 2006; Getzlaf and Osborne, 2010; Diemer et al., 2015; Jemal, 2018). Culturally competent and responsive leaders recognize their social identity and understand how status and power dynamics afford certain identities privilege while oppressing others, shaping the distribution of opportunity (McKenzie et al., 2008; Khalifa et al., 2016).

Developing an equity mindset poses several challenges for how leaders traditionally think about improvement and their role in leading it. Firstly, while leaders with an equity mindset prioritize problems of educational inequity and recognize structural roots of these problems, power dynamics tied to racial and class hierarchies tend to orient most educators to prioritize problems that benefit more societally powerful groups (Lipman, 1998; Datnow and Park, 2018). Meanwhile, a dominant deficit ideology and discourse encourages leaders to locate educational problems in individuals, especially in students and their families (Solorzano and Yosso, 2001; Garcia and Guerra, 2004). Thus, even when leaders focus on problems that relate to inequity, the influence of dominant discourses in the framing of the problem— such as the “achievement gap”—may reproduce deficit-based and individualistic explanations of educational inequities (Au, 2016).

An equity mindset also has implications for how leaders understand their involvement in perpetuating and intervening into problems of inequity. Leaders with an equity mindset develop what Khalifa et al. (2016) described as “critical self-awareness,” continually reflecting on how the power and position of their social identity can shape which problems they perceive and how they interpret them (Khalifa et al., 2016, 1280). However, until recently, many educational leadership programs did little to promote such understanding (Rusch and Horsford, 2009). Amid an ethno-racial gap between educators and students in U.S. public schools (National Center for Education Statistics, 2020), most educational leaders tend to be White males. While people of color and immigrants often cannot avoid developing awareness of racial and ethnic identities, Whiteness is not often explicitly recognized by White people (McIntyre, 1997), and White educators tend to engage in defensive avoidance of discourse about race (King, 1991; Sleeter, 2001; McKenzie and Scheurich, 2004). A prevalent “colorblind” narrative has further silenced discussions of race and racism (Schofield, 2001; Stoll, 2014). As a result, many educational leaders have little understanding of their social identities.

Thus, an equity mindset also has important implications for how leaders understand their role. As Ishimaru and Galloway (2014) describe, equity leaders recognize agency and responsibility to not only develop themselves as individuals but to develop others and mobilize collective action. However, activism has not been found to be central to many education leaders’ role concepts. Instead, many leaders tend to view change as technical and neutral (Heifetz and Laurie, 1997) and see their role as middle managers who implement other people’s policies (Spillane et al., 2002).

2.3 Learning needs for developing equity-focused CI mindsets

The literature reviewed above helps to identify key elements of mindsets for CI or for equity, but little scholarship has brought these two perspectives together to understand how leaders develop an equity-focused CI mindset. Considering the above, developing an equity-focused CI mindset seems to call for many education leaders to learn how to: (a) prioritize problems of inequity; (b) relax attachments to predetermined solutions and understand the problem to be solved; (c) specify an actionable problem in their local context; (d) apply critical perspectives to diagnose systemic roots and challenge how problems are framed; (e) seek to learn from evidence, including from the perspectives of diverse stakeholders or “users”; (f) continuously reflect on their identity and position in relation to the problem; and (g) understand their role as activists who organize collective disciplined inquiry.

Many leadership development programs may not address the full range of these learning needs. Not all programs that teach methods of CI also explicitly focus on equity, and not all programs centered around developing equity-minded leaders support leaders to become stronger organizational problem solvers (Hinnant-Crawford, 2020; Valdez et al., 2020; Howard et al., 2023). CI can be practiced without prioritizing problems of inequity, and CI methods on their own may do little to develop critical consciousness, counter deficit-based discourses, or foster critical self-awareness. Likewise, equity-minded leaders may not necessarily know how to relax their focus on solutions to understand problems or organize disciplined inquiry.

Recently, scholars have begun to identify potential points of synergy (Peurach et al., 2022; Anderson et al., 2023; DeFilippis, 2023; Hinnant-Crawford et al., 2023; Yurkofsky et al., 2023). Considering the learning needs outlined above, developing equity-focused CI mindsets may rest upon leadership development programs that intentionally integrate an equity lens with learning and practicing CI.

2.4 Critical improvement science as a pedagogy for fostering equity-focused CI mindsets

This paper focuses on an Ed.D. program the authors developed around a signature pedagogy of critical IS that intentionally integrates CI methods with an equity focus. The pedagogy proceeds with the assumption that principles of IS are useful, but insufficient, to enable equity-oriented change (Hinnant-Crawford, 2020; Anderson et al., 2023). Ensuring an equity focus with IS requires an explicit focus on problems that center around inequity and an emphasis on understanding how problems of educational inequities are products of histories of oppression and dynamics of power, status, and culture in society. Accordingly, critical IS assumes that developing mindsets for equity-focused CI requires learning methods of problem-solving offered in IS alongside identity work to enable leaders to wrestle with the depth and complexity of improving upon problems of educational inequity. Assuming that equity-relevant problems are tied to oppressive institutional structures reproduced by routine practices, critical IS assumes that transformation requires learning that helps leaders interrogate their own identities and practices, understand the system that produces educational problems, identify an actionable problem as a focus for disciplined inquiry, and challenge their assumptions by listening to voices and experiences of people involved in the change.

3 Research design

This paper asks: In what ways do leaders in the first term of an Ed.D. program focused on critical IS experience emergent shifts towards mindsets for equity-focused CI? While we do not presume that one term of a university program leads to enduring changes in mindsets, we assume that, given the depth of learning offered and students’ self-determined choice to pursue this learning, changes in students’ thinking over time, as well as their reflections on their learning, can reveal emergent mindset shifts that have the potential to sustain as they continue their learning.

3.1 Research context: the Ed.D. program

In the Ed.D. program at the University of Massachusetts Lowell, coursework, program milestones, and dissertation research follow the signature pedagogy of critical IS. Two of the authors originally developed the Ed.D. program to address the persistent academic opportunity gaps in current schools and districts. During the Covid-19 pandemic and following the murder of George Floyd, we felt a sense of urgency to integrate an explicit equity focus across coursework and the dissertation and honed the program to better cohere around critical IS. By creating a practitioner-based Ed.D. program to support the on-going professional needs of K-12 leaders, we hope to develop equity-minded school leaders who will make a positive difference by using critical IS.

An explicit focus on equity combined with learning and applying IS methods makes this program a useful site through which to understand how leaders may develop equity-focused CI mindsets. The Ed.D. is a three-year, cohort-based online program and a member of CPED. Students are practicing professionals who range from teacher leaders to school principals, district leaders, and superintendents, as well as education advocates and consultants in education-adjacent organizations. Courses are primarily asynchronous, but the program offers weekly live sessions and requires a one-week summer residency each year, during which students and faculty come together in person for community building, cross-cohort learning, and completing qualifying exams and proposal hearings.

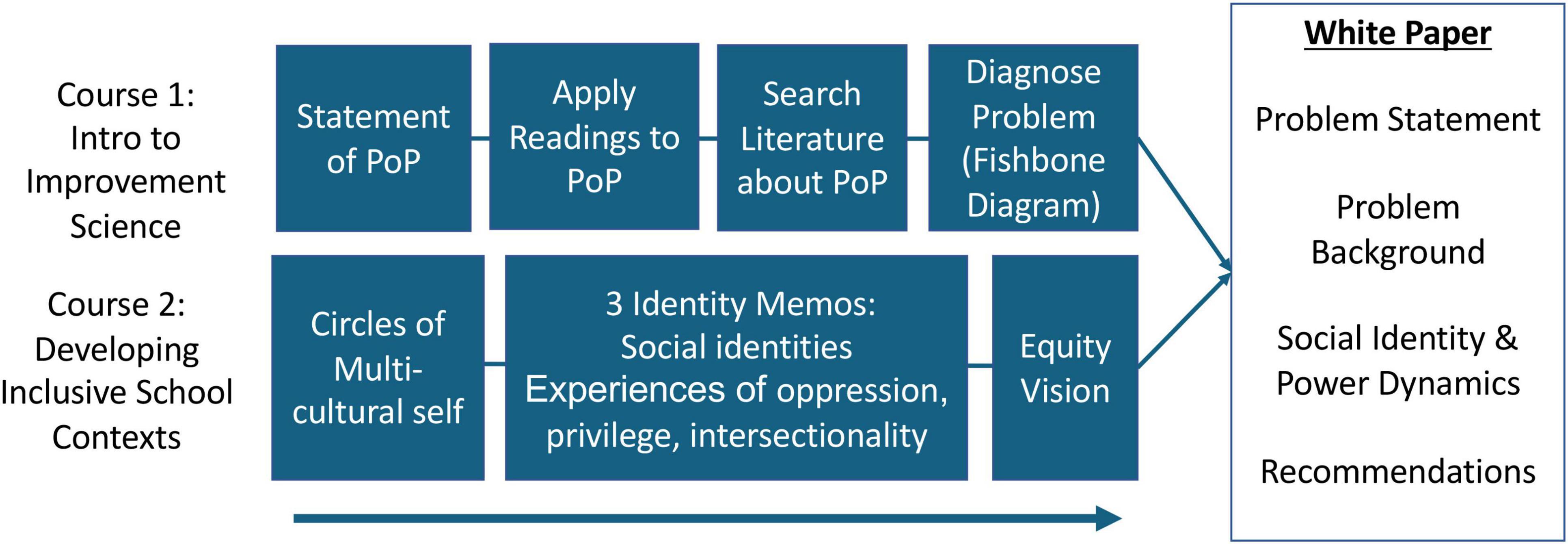

For the doctorate, students complete a dissertation-in-practice in which they identify, analyze, and use IS methods to address an equity-focused problem of practice (PoP) in their organizations. To begin this learning, students complete two aligned courses in the first term. One course introduces IS (Bryk et al., 2015; Mintrop, 2016; Hinnant-Crawford, 2020; Perry et al., 2020) and involves readings and tasks through which students identify and begin to diagnose an equity-focused problem in their own organizations. Students learn how to consult organizational data to identify an equity-relevant problem, conduct an initial literature search about the problem, identify root causes at multiple levels of the system (macro-, meso-, and micro-), and display their diagnosis on an Ishikawa fishbone diagram (Ishikawa, 1989). Students read methodological texts about conducting needs assessments (Mintrop, 2016), including conducting empathy interviews for understanding problems (Hinnant-Crawford, 2020; Nelsestuen and Smith, 2020).

A second parallel course focuses on developing inclusive schools and practices. This course involves readings and tasks about the role that social identity plays in educational problems. Students read core texts about social justice education (Sensoy and DiAngelo, 2017; Gorski and Pothini, 2018) and articles about racial identity development, the role of culture in learning, and how poverty and differences in gender, sexual orientation, ability, and religion can affect educational opportunity. Course assignments invite students to reflect on their social identities, their experiences of oppression or privilege related to those identities, and how these identities relate to their leadership roles.

A joint culminating assessment for both classes is a “White Paper” in which students identify and begin to analyze their PoP through organizational data and literature, discuss how their social identities shape their role as leaders who intervene into this problem, and describe next steps they envision to further address this problem. Students receive feedback on initial drafts of each section throughout the term and turn in a final draft in the final week.

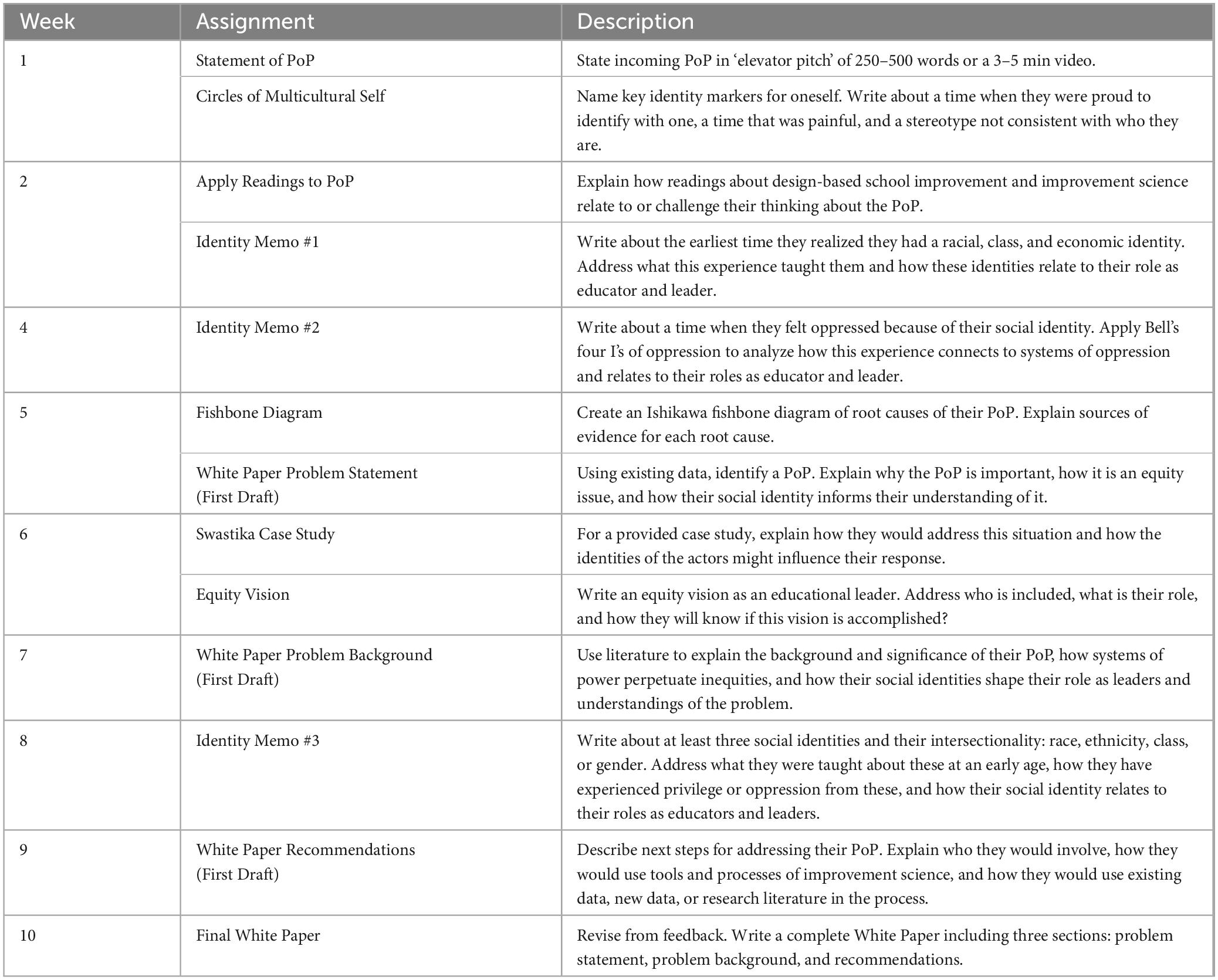

Table 1 below summarizes key assignments from the two courses. Figure 1 below illustrates how key assignments align and culminate in the common assessment, the White Paper.

3.2 Research team and positionality

The research team included three program “insiders”—two current and one former program faculty (first, second, and last authors). To support critical reflection and guard against bias, the research also included two program “outsiders”—Ph.D. students not involved in the Ed.D. program (including the third author). While faculty on the research team had close relationships with the Ed.D. students from previous courses, they were not those students’ current instructors or supervisors during this study. One faculty member identifies as an Asian American woman, and two identify as White women. One Ph.D. student identifies as a White woman, and the second as an African man.

3.3 Participants

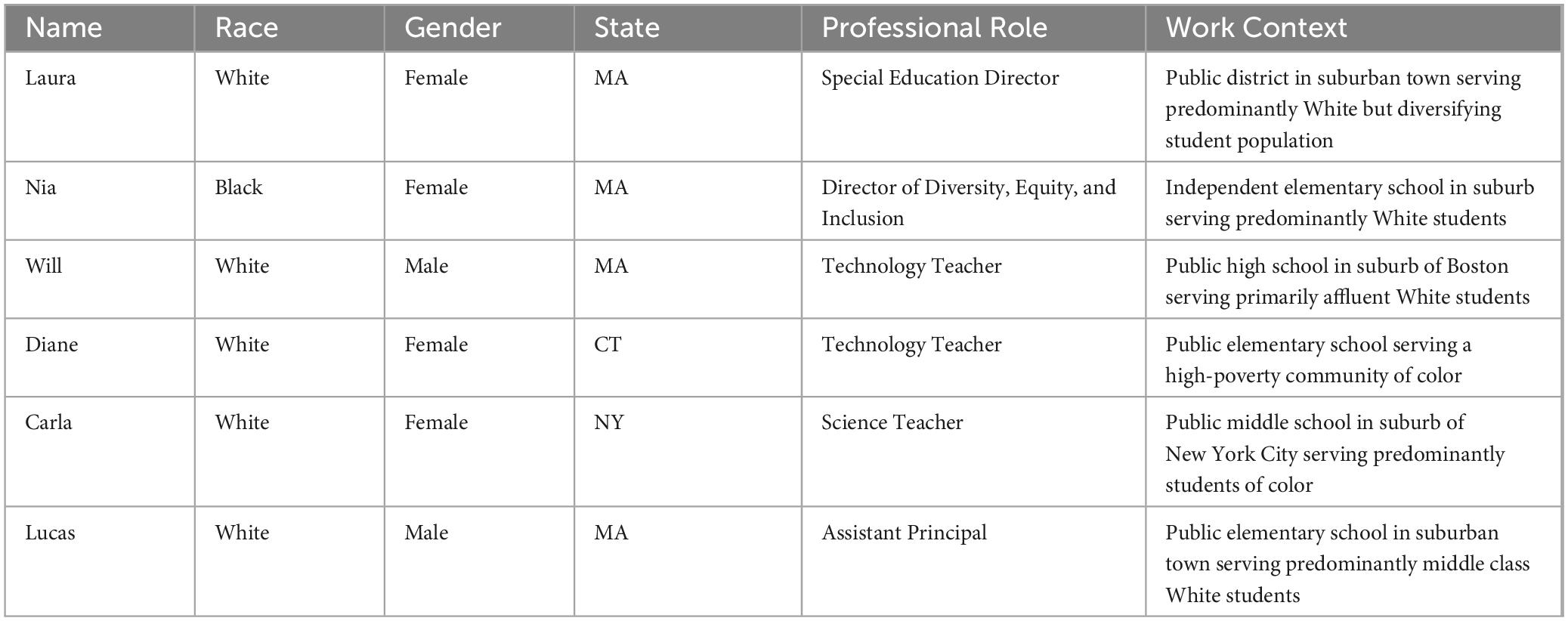

Six students in the 2022 cohort volunteered to participate. Table 2 below summarizes their demographic information and school contexts (all pseudonyms). The complete 42-member cohort self-identified as: 10 males, 32 females; 4 Asian, 2 Black, 4 Latinx, 3 multiracial, and 29 White. Eighteen enrolled in a STEM Leadership program and 29 enrolled in a general Leadership program.

3.4 Data collection

The data for this study includes 13 assignments collected from each student’s first two classes. To enable inferences into contributing factors for changes over time, student work samples include initial and final drafts of the culminating White Paper along with instructor feedback.

To incorporate students’ perspectives, we also conducted semi-structured interviews with each student in the study. The interviews provided insight into students’ perceptions about IS and equity, shifts they experienced since starting the program (if any) and their explanations for these, and their perceptions of shifts researchers identified in their work samples. The interview protocol is provided in the Supplementary material. The interviews allowed deeper inference into shifts that occurred and contributing factors and allowed for member checking of researchers’ interpretations. For ethical reasons and to reduce bias, the interviews were conducted by the two Ph.D. students.

3.5 Data analysis

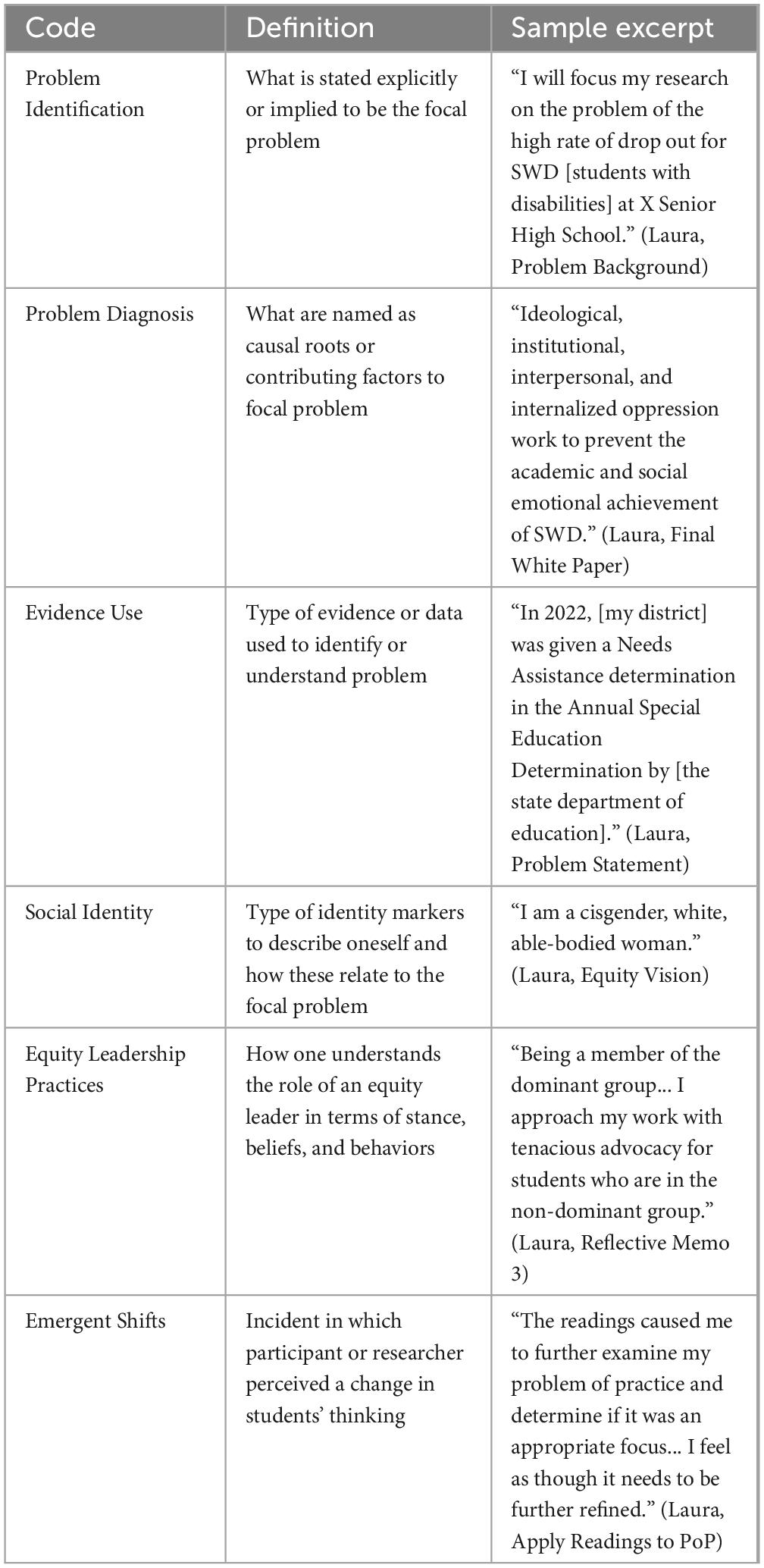

Following the conceptualization introduced earlier, we assumed that shifts in mindsets emerge as students grapple with new ideas in relation to their prior beliefs and experiences. Because equity-oriented learning asks students to wrestle with their beliefs in relation to their positionalities and identities, we assumed that shifts in mindsets could entail a unique journey for each student. Thus, we began data analysis by treating each student as a case, and then identified cross-case patterns. Using (Dedoose, 2018), to all data for each student, we applied a priori codes based on learning needs drawn from the literature review and tied to domains of learning addressed in the first courses, as shown in Table 3: problem identification; evidence use; problem diagnosis; social identity; and equity leadership practice.

All authors participated in developing and applying codes to the work samples and interviews for one student. The team met to compare and discuss overlaps and discrepancies to arrive at a shared understanding. For the remaining cases, one insider and one outsider on the research team coded each case and met regularly to discuss and compare their analyses to arrive at shared understandings and identify emergent findings. For each student case, we developed matrices by code and chronologically over the ten weeks of the summer to identify prevailing patterns, observable shifts in students’ thinking in each domain, and contributing insights. We triangulated patterns from the work samples with the interviews to determine the most important shifts and contributing factors, refining the matrices and constructing analytical memos for each case. As a member check, we shared a case summary with each participant and asked for their input. No participants requested revisions. In a final analysis stage, we examined cross-case patterns with cross-case matrices and analytic memos.

3.6 Limitations and delimitations

This exploratory study draws upon a small convenience sample from one Ed.D. program. As such, it is not intended to produce generalizable findings. While students’ interactions on discussion forums and live online sessions likely shaped their learning experiences, for ethical reasons, we could not include discussion forums and live sessions as data sources because not all students in the cohort participated in the research. Also, we did not think it ethical to study students for whom we were currently serving as instructors. Therefore, our insights about contributing influences on students’ thinking are limited to what we could infer from their assignments, instructor comments on the assignments, revisions they made, and interviews. We hope that deep analysis of individual students’ responses to a set of instructional tasks, their reflections during interviews, and new learning that became apparent as a result can provide insights into how mindsets for equity-focused CI develop, given how little is known in this area. We also hope that our findings can inform quality improvements to our Ed.D. program and other programs working on similar learning goals.

4 Results

Through an interplay of reflecting upon their identities and learning how to define and diagnose a PoP, critical IS enabled emergent shifts towards equity-focused CI mindsets for students in this study. At the program’s start, these students demonstrated a more traditional mindset. They assumed that equity-focused improvement was a straightforward matter of convincing other people to implement their chosen solutions. They tended to view their assumptions about the problem, and their social position in relation to the problem, as unproblematic. By the end of the term, students began to see equity-focused improvement as a much more collective, complex, and uncertain learning journey. As they became challenged to recognize deficit thinking and how their own position and power could perpetuate problems of inequity, they began to relax their attachments to solutions, explore the problem, and think how to involve the people experiencing the problem in the process. As they were challenged to learn from evidence and identify systemic roots of problems of inequity, they began to let go of an urge for a quick fix and enter into productive struggle, recognizing they were only at the beginning of a longer inquiry process.

Across the term, shifts in students’ thinking became apparent as course material and tasks, interactions with peers, and instructor feedback continually pressed them to apply new learning to their PoPs and their leadership roles. Mindset shifts became evident through new learning across five learning domains: problem identification, use of evidence, problem diagnosis, social identity, and leadership identity. In the domain of problem identification, students started with tendencies to jump to solutions and focus on broad equity issues. New learning prompted them to relax their focus on solutions and instead work on clarifying and specifying an actionable problem. Shifts in how students identified the problem emerged in connection with shifts in how they used evidence. At the start, students tended to rely on evidence from the outside—from the accountability system or research literature—to confirm their preexisting assumptions about the problem or the solution. By the end of the first term, they came to believe that defining a problem of practice would require more internal evidence and other perspectives beyond their own—especially the perspectives of people who most directly experience the problem—and to open themselves up to refine or change their focal problem or change ideas in response to this evidence. Shifts in problem identification and evidence use connected to shifts in their approach diagnosing problems. They started with a tendency to locate their problem in one level of the system—mostly, in students. By the end of the term, they began to “see the system” of institutional, organizational, interpersonal, and intrapersonal causal factors, leading them to question their initial ways of framing the problem and the appropriateness of their original solution ideas.

New insights about the complexity of their problems intersected with new understandings about their own social identities. When first prompted to describe their identity, students tended to name neutral and socially legitimated identity markers that distanced them from being involved in the problem. As they applied new learning to their personal experiences of privilege or oppression, they began to identify more vulnerable and stigmatized aspects of their identities.

All of the above learning culminated in shifts in how students thought about the practice of equity leadership. Students started out thinking of equity leadership as a matter of developing their own awareness, acting as individual advocates, and giving directives to others. Through learning about IS in combination with systems of oppression and social difference, students started to shift towards a view of equity leadership as participatory and collective. They began to realize their role was not to tell others what to do but rather to lead a collective learning process that involved and empowered others—especially those whose voices have historically been silenced—to shape the direction of the change. With increasing critical self-awareness, they also started to realize that they were not neutral parties but active agents in a system of oppression and power whose beliefs and actions could perpetuate or ameliorate their PoPs.

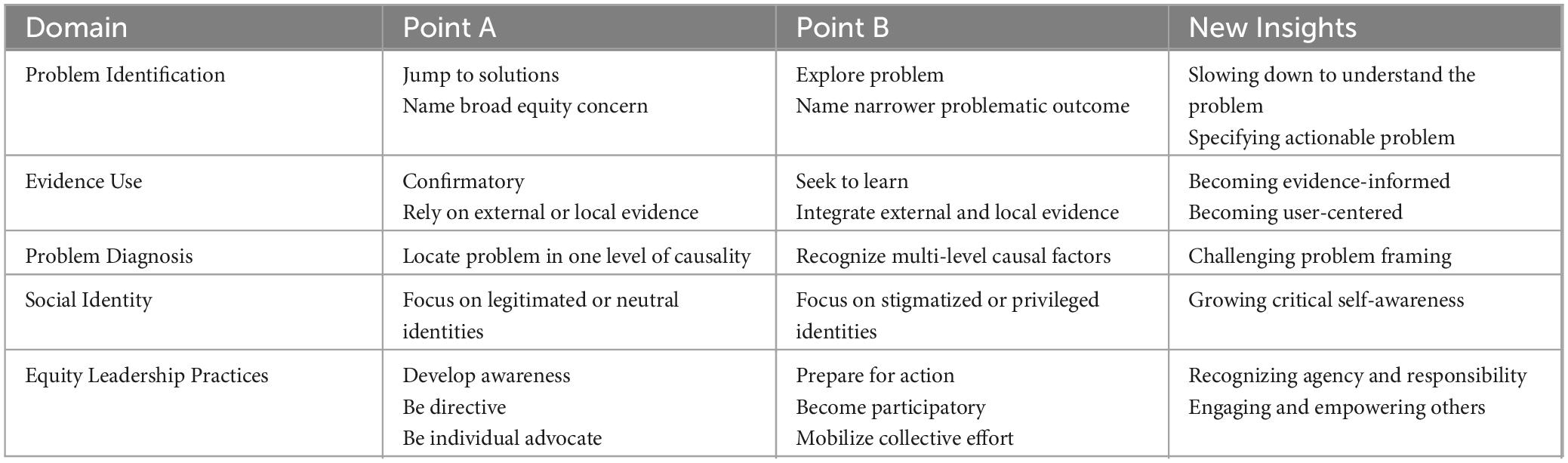

Table 4 summarizes these cross-student patterns in each domain. “Point A” describes a prevailing pattern evident early in the term, and “Point B” describes a prevalent pattern evident later in the term. In the right column, we describe new insights that students gained through their experiences in the Ed.D. program that we inferred to contribute to these shifts.

The language of Point A to B helps to make visible where students stretched into new ways of thinking and tried on new ideas. This approach risks to portray development as a linear process that results in stable new mindsets. On the contrary, we assume that developing new mindsets is an iterative and ongoing learning process. To demonstrate how our findings emerge from the unique learning journeys of each student, below we present the learning journeys of three individual students. Through these cases and analyses that follow, we trace changes in the thinking of Lucas, Diane, and Laura, whose shifts are representative of patterns across all participants. Results for the remaining three students are displayed in the Supplementary Tables B1–B3.

4.1 Lucas

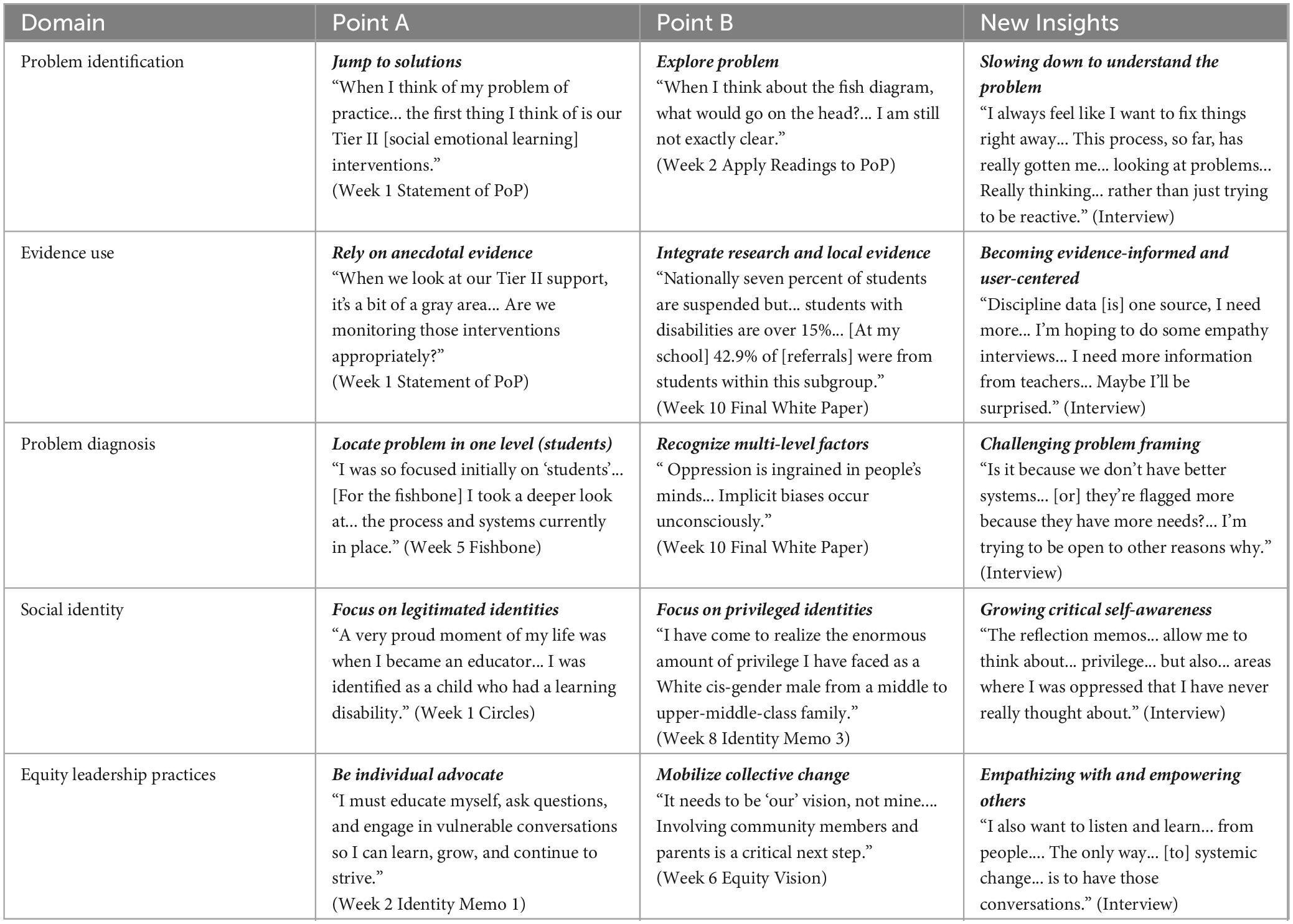

Lucas is a White male Assistant Principal in a suburban town in Massachusetts serving predominantly White and affluent students. He is focused on improving social emotional interventions for students at his school. As shown in Table 5, new learning through critical IS enabled Lucas to challenge his initial understanding of the problem and his role as an equity leader.

4.1.1 Problem identification: from jumping to solutions to exploring the problem

When first prompted to identify a PoP, Lucas focused on a concern with how his school was implementing a program of social emotional supports. “When I think of my problem of practice… the first thing I think of is our Tier II [social emotional learning] SEL interventions… My overall problem of practice, I am thinking, would be: teachers and staff effectively determining and monitoring Tier II SEL interventions” (Week 1 Statement of PoP).

As Lucas engaged with course material, he began to question this solution-driven approach to improvement. As he read about how to identify a PoP and create an fishbone diagram, he began to realize that he needed to do more to clarify the problem: “I was originally thinking my problem was the tracking of Tier II SEL interventions… However, when I think about the fish diagram, what would go on the head of the fish?… I am still not exactly clear… I am learning this process will support me” (Week 2 Apply Readings to PoP). As Lucas explained in the interview, his initial impulse to focus on solutions reflected his more typical way of thinking about improvement—to act quickly to “fix” things. Learning about IS prompted him to realize the need to slow down to clarify the problem: “As an administrator and as an educator, I always feel like I wanna fix things right away… This process, so far, has really gotten me… looking at problems… really thinking… rather than just trying to be reactive and fix it.”

4.1.2 Evidence use: from anecdotes to becoming evidence-informed and user-centered

When Lucas first identified a problem with Tier II interventions, he assumed this was a problem based on anecdotal impressions: “When we look at our Tier II support, it’s a bit of a gray area… Are we monitoring those interventions appropriately?” (Week 1 Statement of PoP). As assignments and instructors prompted Lucas to ground his problem in literature and organizational data, he moved past the “gray area” to recognize a more specific problem: disproportionate use of exclusionary discipline for students with disabilities. His integration of research and local evidence revealed this as a national and local problem: “Nationally seven percent of students are suspended, but it is estimated that students with disabilities are over 15%… [At my school] 42.9% of the total [referrals] were from students within this subgroup” (Week 10 Final White Paper).

As Lucas learned more about IS, he realized that he needed additional evidence from perspectives beyond his own to establish a PoP. In his final White Paper, he described a plan to collect evidence about what ‘users’ in his organization perceived through empathy interviews and surveys with teachers and students. As he explained in the interview, he recognized a need to relax his predetermined ideas about what might be the problem and instead learn from evidence and users:

I’m hoping to do some empathy interviews… I think I need more information from teachers… Maybe I’ll be surprised.

While this shift in thinking was not absolute—Lucas continued to describe Tier II interventions and referrals as his problem of practice—he began to question his assumptions and realized the need to open himself to learn from others’ perspectives.

4.1.3 Problem diagnosis: from one to multiple levels and challenging problem framing

Midway through the term, Lucas learned about deficit ideologies and was prompted to construct a fishbone diagram with factors at micro-, meso-, and macro-levels. As he worked on this assignment and shared it with his peers and instructors for feedback, he started to realize that his initial way of identifying the problem was to locate it in students. He wrote, “After talking to my writing partners and discussing my initial problem of practice with [my instructor], I was able to discuss and look at my problem from a different lens/perspective. I was so focused initially on ‘students’ as the problem… [For the fishbone] I took a deeper look at… staff involvement, and the process and systems currently in place” (Week 5 Fishbone). As he worked to identify meso- and macro-level factors, he began to wrestle with how the problem of disproportionate referrals for students with disabilities was tied to deeper taken-for-granted beliefs, ingrained routines, and institutional structures that perpetuate educational inequity. By the end of the term, rather than perceiving a technical problem of “implementing Tier II interventions,” he began to consider that the problem of disproportionate referrals may be due to a combination of organizational practices and relational dynamics tied to power dynamics and implicit biases: “Students in schools who fit into dominant groups versus minority groups may be treated disproportionately… Oppression is ingrained in people’s minds… Implicit biases occur unconsciously” (Week 10 Final White Paper). This expanded diagnosis of the problem signaled shifts in how he would change it. Merely implementing student interventions would be insufficient. The change process needed to address routine attitudes and beliefs through which educators perceived students with disabilities.

4.1.4 Social identity: from legitimated to privileged identities and critical self-awareness

As Lucas began to expand his thinking about his problem, course tasks and instruction also pressed him to become more aware of his social identity. When first prompted to describe his identity, Lucas focused on neutral and legitimated identity markers as an “educator” with formal labels “as a child who had been identified with a learning disability.” As course assignments and readings pushed Lucas to reflect on race, class, and gender identities, he began to think more about his experiences of privilege, evident in his identity memo towards the end of the term: “Before engaging in this program, I didn’t think much about my identity… I have come to realize the enormous amount of privilege I have faced as a White cis-gender male from a middle to upper-middle-class family shielded me from taking a deep look at who I am.”

4.1.5 Equity leadership practices: from individual advocate to mobilizing collective effort

For Lucas, learning to recognize how his identity connected to systems of power was especially impactful on how he thought about educational change and his role in it. Lucas entered the program with strong commitment to making the educational system more just. However, when first prompted to describe what it meant to be a leader for educational equity, he described it as a matter of his individual actions to develop his awareness of difference and foster an inclusive environment. “As an educator and leader, I must educate myself, ask questions, and engage in vulnerable conversations so I can learn, grow, and continue to strive to create a warm and inclusive school community” (Week 2 Identity Memo 1).

As Lucas became challenged to think more deeply about his PoP and his social identity, he started to recognize how his privilege could limit his understanding and view of the problem. As he applied this new insight to his leadership role in an equity vision midway through the term, he began to see equity leadership as more than individual awareness and effort but as developing, empowering, and mobilizing others for change: “Within a school, it needs to be ‘our’ vision, not mine… All voices must be heard… Involving community members and parents is a critical next step.” By the end of the term, as he reflected on his intersectional identities and developed a deeper understanding of his PoP, he described a growing awareness that acting as an equity leader required intentionally listening to and learning from people with different perspectives and experiences from himself and opening himself up to being vulnerable and ‘wrong.’ As he explained in the interview:

I’ve talked a lot about my disability because I feel like it’s the one part of my identity that that I’ve used to help in my role… I do not know how it’s like to be to be a student that had financial difficulties or wasn’t a nondominant race… but I also want to listen and learn… I think really the only way that we can really make … some of that systemic change… is to have those conversations… You have to fail forward.

4.1.6 Summary of Lucas’s shifts

Lucas started with a more typical educational leader mindset—assuming that equity-focused improvement proceeded by through implementation of his preferred interventions, approaching the work as an individual whose role was to help others implement solutions. As he learned and applied principles of IS, Lucas recognized the need to better understand the problem before jumping to solutions. As he explored the problem while learning about systems of oppression, he realized the need to not only become more evidence-informed but also to seek and involve users’ perspectives. A new understanding of the problem and a different role for himself in addressing it began to come into view. Rather than a technical problem of ‘implementing Tier II interventions,’ he began to consider the need to address organizational and relational practices through which educators perceived and responded to the needs of students with disabilities. Rather than “fixing” the implementation of a program, Lucas started to see equity-oriented CI as requiring critical dialogue and ongoing learning to address deeper assumptions and mobilize a collective learning process. He also began to recognize that his role as leader in the change process would entail being a learner, too.

4.2 Laura

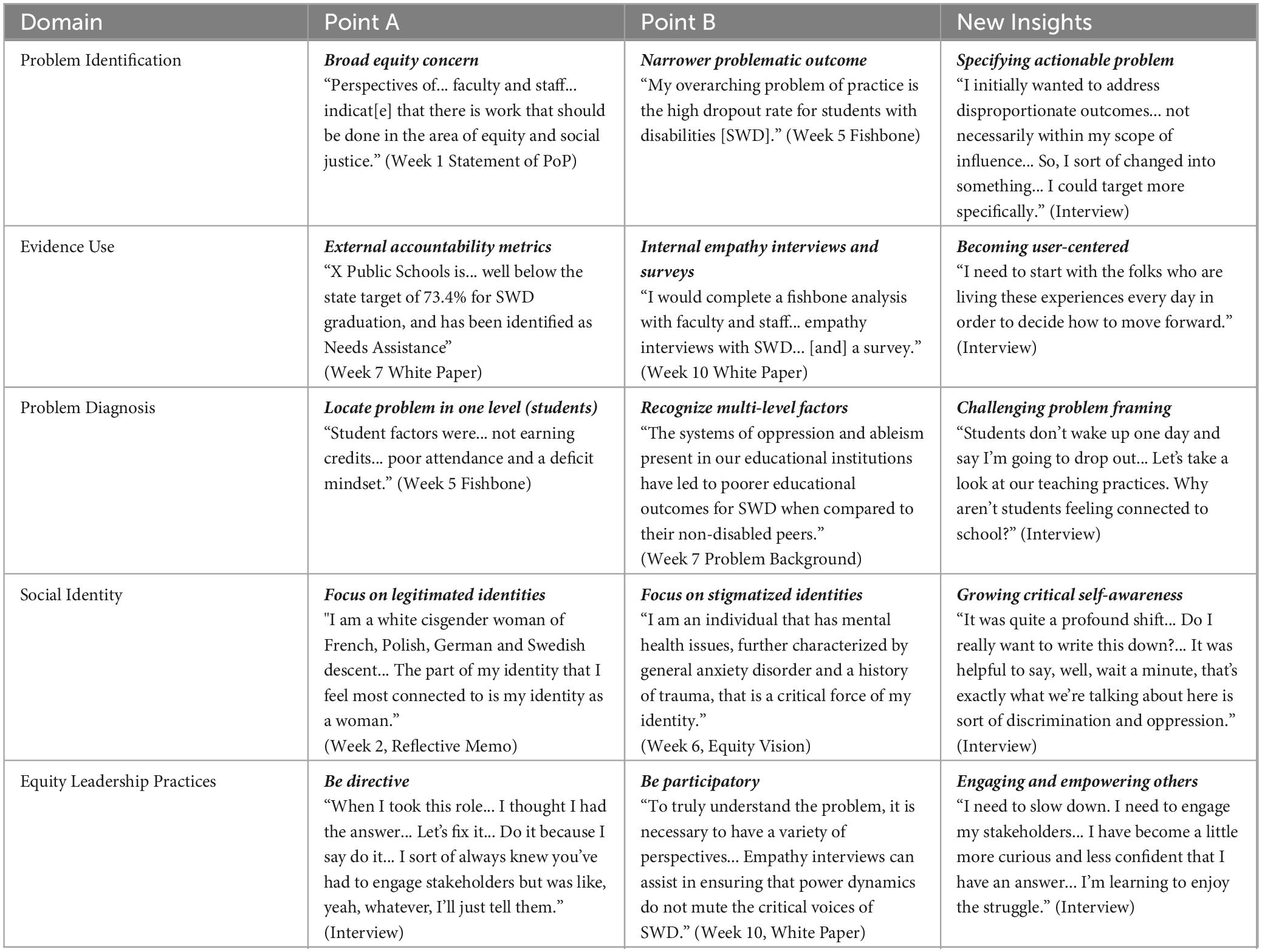

Laura is a White female Special Education (SPED) Director in a small suburban town in Massachusetts. Her district serves a predominantly White but diversifying student population, of which about one-fifth qualify for special education services. As shown in Table 6, through the learning in the program over the first term, Laura’s thinking evolved about her PoP and how to address it, signaling emergent shifts towards an equity-focused improvement mindset.

4.2.1 Problem identification: from broad concern to specifying an actionable problem

When first asked to identify an equity-focused PoP, Laura described a broad concern:

Perspectives of… faculty and staff regarding the district’s equity and inclusion… do not mirror those of the minority ethnic, racial student and family population, indicating that there is work that should be done in the area of equity and social justice (Week 1, Statement of PoP).

As she engaged in course tasks and readings, she soon saw a need to narrow her problem focus: “I am mindful that the PoP should be actionable and have a narrow scope” (Week 2, Apply Readings to PoP). Midway through the term, she named the problem this way: “My overarching problem of practice is the high dropout rate for students with disabilities (SWD) (Week 5 Fishbone).” As she explained in the interview, she saw this as a more promising problem ‘of practice’ because it connected to her concern for equity and inclusion but was within her sphere of influence in her role in the district: “I initially wanted to address disproportionate outcomes for students of color… not necessarily within my scope of influence… So, I sort of changed into something that… I could target more specifically… and that has been a real issue in the research for students in the non-dominant group.”

4.2.2 Evidence use: from external accountability to users’ perspectives

To identify a problem with “within my scope of influence,” Laura initially turned to evidence from the external accountability system. Laura’s more “actionable” problem had been identified for the district by the state: “X Public Schools is… well below the state target of 73% for SWD graduation and has been identified as Needs Assistance” (Week 7, White Paper Problem Background). As she received instructor feedback and learned more about methods of IS, she saw a need to expand beyond a reliance upon the accountability system and collect evidence that she had not previously considered: empathy interviews with students about what leads to “drop out.” As she wrote in her final White Paper, she planned to conduct one-to-one empathy interviews with students with disabilities to “ensur[e] that power dynamics do not mute [their] critical voices.” As she explained in the interview, she realized, “I need to start with the folks who are living these experiences every day in order to decide how to move forward.”

4.2.3 Problem diagnosis: from student deficits to organizational practices

As Laura begn to shift her understanding of how to use evidence, she began questioning how the external accountability system framed the problem. While searching literature to identify root causes of “drop out” at macro-, meso-, and micro-levels, she also learned about systems of oppression tied to different social identities. She began to consider how cultural assumptions of ableism might be creating alienating experiences for students with disabilities. As she learned about deficit ideology, a new awareness of macro-level roots of her problem prompted Laura to consider how the phrase “drop out” located the problem in students. While working to connect macro- and meso-level factors in the school and district, she found a more useful framing: “school connectedness.” As she explained in the interview, this new framing helped to change the focus away from “fixing” students towards identifying and changing problematic organizational practices:

Grade 10 and 11 students don’t wake up one day and say I’m going to drop out today. It typically started farther back in their educational career… For example, let’s take a look at our teaching practices. Why aren’t students feeling connected to school? What do they have to say about our teaching practices? What do they have to say about sort of ableist assumptions or perspectives?

4.2.4 Social identity: from legitimated to stigmatized identities and critical self-awareness

Emergent shifts in Laura’s understanding of the problem occurred alongside new understandings of her social identity. When first prompted to write about her identity, she described herself this way: “I am a white cisgender woman of French, Polish, German and Swedish descent… Perhaps the part of my identify that I feel most connected to is my identity as a woman” (Week 2 Reflective Memo). These were markers that she saw as unproblematic and neutral in relation to her problem. As course tasks pushed her to reflect on personal experiences of oppression, bias, and privilege, she began to wrestle with a more vulnerable and hidden aspect of her identity, connected to experiences of trauma and stigma: “I am an individual that has mental health issues, further characterized by general anxiety disorder and a history of trauma, that is a critical force of my identity (Week 6 Equity Vision).” In the interview, Laura described this as an important learning:

It was quite a profound shift… It was difficult, too. Like, do I really want to write this down?… The teacher might think X or I’m incapable, and it was helpful to say, well, wait a minute, that’s exactly what we’re talking about here is sort of discrimination and oppression… As I understood the intersectionality of different components of my privilege, I really started to develop an understanding of my leadership and who I was and how that impacts my daily actions.

Ascribing mental health challenges to her identity allowed Laura to connect to a concrete experience of stigma. As instructors encouraged Laura to apply this new awareness of her identity to her PoP, she began to more deeply understand how invisible forces of power—such as stigma and privilege—can shape every element of a CI process. The experience of vulnerability, and her own emotional struggle with it, helped Laura begin to better understand the operation of deeper roots of the problem tied to structural and systemic forces that are often not readily observable. As she wrote in her final White Paper, “My experiences, social identity, and intersectionality drive me to look beyond the surface as an educator. While there may be seemingly obvious observations about a student’s social identity, we often are not aware of other pieces of their identity that are not readily observed. These pieces may have a profound impact on them as individuals.”

4.2.5 Equity leadership practices: from directive to participatory

Changes in how Laura thought about her PoP and identity combined to reshape how she saw her role as an equity leader. From her position as a central office leader, she began the program believing that being an equity leader meant acting in a directive way—somewhat top-down. As she explained in the interview:

I’m a problem-solution person and when I took this role, I tried all sorts of solutions. I thought I had the answer… Let’s just fix it… Here’s my plan. Do it because I say do it and do it because I’m telling you there’s a problem.

Over the first term, she described a “huge change” in her understanding of her leadership role. From course readings, assignments, and instructor feedback, she began questioning her tendency towards quick decisions to implement ‘her’ solutions. As she explained in the interview, “Like if you knew what you were gonna do, jumping right in, what’s the point of engaging in this program?… The professor said that in one of the first classes and I was like, ‘Well, what do you mean? I already have this. I’m already gonna do X.’ And now I’m like, ‘What was I even thinking? That makes no sense.”’ Laura started to realize that she needed to, as she expressed it, “slow down”—to think through the problem and solution more carefully and to take the time to do this collaboratively with stakeholders. Equity leadership, she was realizing, required her to become less directive and more participatory. She explained in the interview:

I need to slow down. I need to engage my stakeholders… Yes, I sort of always knew you’ve had to engage stakeholders but was like, yeah, whatever, I’ll just tell them. [But] I really need stakeholder buy-in. I really need the perspective of stakeholders, parents, educators, service providers, community members, administrators… I have become a little more curious and less confident that I have an answer… I’m learning to enjoy the struggle.

4.2.6 Summary of Laura’s shifts

When Laura started the program, her mindset about equity-focused change entailed quickly attaching a broad issue to a solution that she “knew” would “fix” it and telling people what to implement. Through the learning of the program, she realized the importance of specifying an actionable problem and that doing this was not so simple as adopting a problem posed by the external accountability system, especially as she realized how the system tended perpetuate deficit ideology. Instead, she started to see that specifying an actionable PoP required collecting and analyzing internal evidence—from the perspectives of users inside of the organization —and wrestling with deeper forces of oppression at the root of problems. Thus, she started to realize, problems of inequity cannot be addressed with “quick fixes” in which people are told what to “implement.” Instead, improving upon problems of inequity required constant reflection on her own assumptions and “slowing down” to learn from those who directly experience the problems —before you can understand what the problem is or how to improve upon it. These emergent shifts in her thinking signaled the potential for a quite different change process and leadership style that involved “learning to enjoy the struggle.”

4.3 Diane

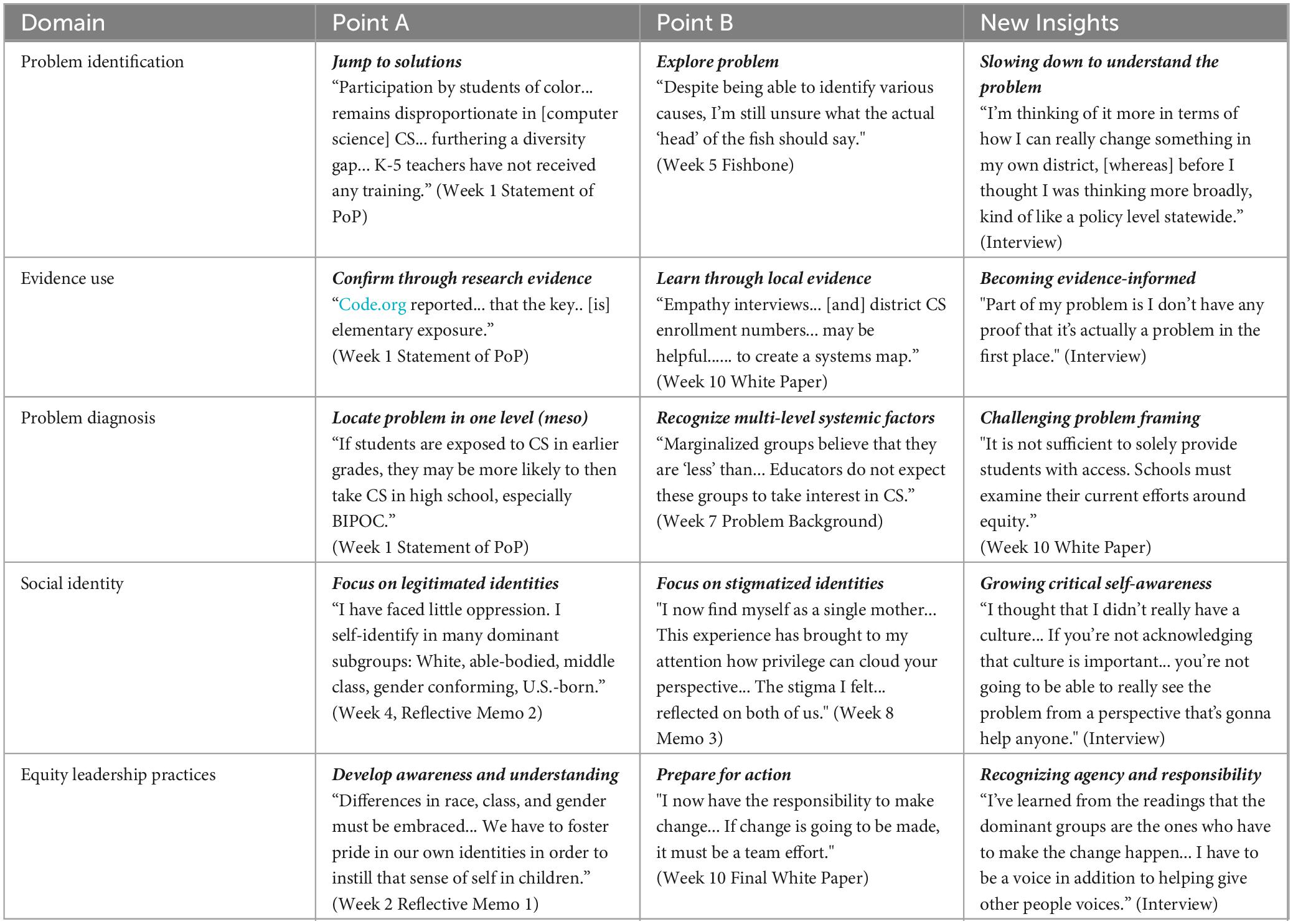

Diane is a White female technology teacher with over fifteen years of experience, working in a public elementary school in a district serving a high-poverty community of color in Connecticut. Diane started out with a concern for inequitable access to computer science (CS) education for students of color and females. As shown in Table 7 below, learning from the program pressed her to become challenge her assumptions, expanding her understanding of the issue’s depth and her role in it.

4.3.1 Problem identification: from jumping to solutions to exploring the problem

At the start of the program, when first asked to describe her PoP, Diane expressed it this way:

Participation by students of color… remains disproportionate in [computer science] CS… furthering a diversity gap… The majority of [state] K-5 teachers have not received any training in the subject… We need better teacher training and coaching (Week 1 Statement of PoP).

Thus, Diane initially thought that improving educational equity started by identifying a broad concern—“a diversity gap in CS” access—quickly attached to a known solution of teacher training.

Over the term, as she read about IS and received feedback from instructors, Diane realized that what she had initially stated might be an important problem in the field of education—but it was not (yet) a problem ‘of practice.’ She started to realize this when prompted to create a fishbone diagram: “Despite being able to identify various causes, I’m still unsure what the actual ‘head’ of the fish should say” (Week 5 Fishbone). As Diane explained in the interview, she had initially assumed that a PoP referred to a broad state-wide policy issue. By the end of the term, she had come to understand that a PoP required her to identify a practice or process to target for change within her district: “I’m thinking of it more in terms of how I can really change something in my own district, [whereas] before I thought I was thinking more broadly, kind of like a policy level statewide.”

4.3.2 Evidence use: from confirming through literature to learning from local evidence

In her initial approach to problem identification, Diane relied heavily upon external evidence in the literature to identify a system wide policy problem: “A 2020 Gallup study estimates that only 21% of elementary schools across the country offer a computer science class… Code.org reported… that the key.. [is] elementary exposure” (Week 1 Statement of PoP). As she began to learn that identifying a PoP would require her to consider local evidence, she ran into a barrier: as an elementary school teacher, she did not have ready access to organizational data. As she explained in the interview: “Part of my problem is I don’t have any proof that [inequitable CS course access] is actually a problem… I wouldn’t [normally] have access [to that data] for my district.”

Although Diane was not able to gain access to or collect this data during the first term, through learning and reflecting on IS and the importance of being evidence-informed and user-centered, her thinking about how to identify a PoP—and the kind of evidence she needed to do so—began to shift. She conceived of plans to access and collect school data and conduct empathy interviews “to create a systems map to help guide my next steps” (Week 10 Final White Paper).

4.3.3 Social identity: from legitimated to stigmatized identities and critical self-awareness

Diane’s emerging insights about how to identify a PoP occurred alongside shifts in how she thought about her social identity. When first asked to describe her identity, she described herself as a member of “many dominant subgroups… White, able-bodied, middle class, gender-conforming, U.S.-born.” As she was prompted to reflect upon her experiences of bias and oppression, she began to focus on a more stigmatized aspect of her identity, which she often felt too ashamed to admit:

I now find myself as a single mother… This experience has brought to my attention how privilege can cloud your perspective… The stigma I felt [from my husband’s mental health struggles] reflected on both of us, and I tried my best to keep it known from friends and co-workers (Week 8 Memo 3).

During the interview, she explained how new insights about herself helped her understand the depth of change forces needed to improve upon problems of educational equity:

For a long time I thought that I didn’t really have a culture… I’ve realized through a lot of the work that.. if you’re not acknowledging that culture is important… you’re not going to be able to really see the problem from a perspective that’s gonna help anyone.

4.3.4 Problem diagnosis: from one to multiple levels, challenging problem framing

Course readings and assignments about culture and identity began to challenge Diane’s thinking about what might be causing the problem of inequitable CS access. At first, her intuitive understanding was that the problem was rooted in unenforced policy mandates and a lack of teacher training. As she worked to identify root cause factors at micro-, meso-, and macro-levels and reflected on more stigmatized and vulnerable aspects of her identity, she began to rethink her framing of the problem of disparities in CS access. It may not be a technical problem of disobeyed policy mandates and absent training programs. The problem may be rooted in deeper relational and cultural dynamics, as she wrote in her final White Paper:

Institutional, ideological, internal, and interpersonal oppression deeply undermines the abilities of diverse populations in computing…. It is not sufficient to solely provide students with access. Schools must examine their current efforts around equity, and question how their practices will directly impact families (Final White Paper).

4.3.5 Equity leadership practices: from awareness to action

New learning across the domains above culminated in in shifts in how Diane saw her role as an equity-focused educational leader. Early on, Diane described herself as a teacher who worked to individually develop her self-awareness and foster self-pride in her classroom: “Differences in race, class, and gender must be embraced by ourselves as educators… We have to foster pride in our own identities in order to instill that sense of self in children” (Week 2 Memo 1). By the end of the term, Diane began to realize that equity leadership involved not merely awareness but “responsibility to make change” (Week 10 Final White Paper). As she moved past thinking of mprovement as investigating broad policy concerns from a distance towards preparing to take action on a local PoP, she began to newly recognize herself as someone with power. As she explained in the interview, she had come to realize that being an equity leader meant recognizing her position in a dominant status and using her power to empower others:

I’ve learned from the readings that the dominant groups are the ones who have to make the change happen, right? So, I have to take part in making that change… I have to be a voice in addition to helping give other people voices.

Diane was becoming able to problematize her initial ways of thinking about equity leadership as mere awareness and intellectualizing. While Diane’s new insights do not mean that she has completely transcended a deficit orientation, she began to realize that being an equity leader meant recognizing her own power and responsibility to act and to think about how to use her power to amplify and respond to the voices of the marginalized.

4.3.6 Summary of Diane’s shifts

At first, Diane assumed that her research would focus on understanding a broad policy problem from the distance of scholarly literature. As she faced an expectation to use her research to take action to improve upon a problem of inequity in her context, she began to realize she could not rely upon the literature alone. She needed to local data—to establish if the problem existed and its causal factors. As she practiced using a systems and structural view to diagnose the root causes of the policy problem, she realized that her initial intuitive assumptions about the solution were too simplistic. Her emerging realization of the complexity of change needed intersected with a new awareness of her own identity and how power played a role in perpetuating inequity. This had implications for how she saw herself as a leader in the process. She would need to stretch outside her comfort zone—of being an aware and inclusive teacher—to organize more ambitious collective change. This meant considering how to leverage her power to act and “give voice” to those not in positions of power, while remaining humble and self-reflective.

5 Discussion

While existing scholarship has articulated elements of mindsets entailed for equity-focused leadership (Ishimaru and Galloway, 2014; Khalifa et al., 2016) or leadership for CI (Mintrop, 2016; Dixon and Palmer, 2020; Biag and Sherer, 2021), previous research has seldom examined how to link equity to CI leadership and the kinds of learning experiences that may enable leaders to develop mindsets for equity-focused CI.

To address this, this study set out to understand the extent to which an Ed.D. program focused on critical IS—an integration of equity and IS—might foster equity-focused CI mindsets. This pedagogy assumes that disrupting persistent inequities in schooling requires both the action-oriented and problem solving mindsets of CI but also leaders’ prioritization of and structural analysis of problems of educational inequity (Gorski, 2011)—so as to conceive of change processes that take aim at how power, resources, and opportunity are distributed.

We designed this pedagogy, and our study of it, around the assumption that equity-focused CI entails counter-institutional orientations and leaders have likely developed countervailing habits of mind that need to be shifted or unlearned. We found evidence that the learning from the first term of courses designed around critical IS enabled emerging shifts in leaders’ thinking towards mindsets for equity-focused CI. These findings point to the potential of a leadership program that integrates an explicit focus on equity with IS (Hinnant-Crawford, 2020).

The results have implications for understanding how mindsets shift and recommendations for leadership development programs. Firstly, it was the interplay of learning about CI and about equity that created deeper learning experiences that enabled emergent shifts in students’ mindsets. Two parallel courses—one about methods of CI and another about culture and identity—that used a common culminating assessment appeared to be impactful program features. These findings suggest synergy: learning about equity furthered students’ problem-solving competence for CI and learning about CI supported development of an equity lens. In other words, linking students’ initial problem identification and diagnosis to learning about the foundations of cultural competence and identity work proved generative. Inviting leaders at the beginning of their doctoral and improvement journeys to become aware of their social identities and reflect upon their positionality in a system of power, at the same time as they learned about methods of IS, enabled recognition of how experiences of privilege, oppression, and bias can shape the problems they prioritize and their ways of understanding them. These new understandings of their social identities intersected in important ways with how leaders diagnosed and framed their problems and the depth of change they aspired to. For students embedded in a system that invites a managerial orientation towards change and implementation of quick and technical solutions, pairing the learning of IS with critical identity work invited students to question their assumptions about their leadership role and wrestle with the complexity of how to redress problems of educational inequity.

Secondly, applied learning appeared important for fostering emergent shifts in mindsets. Existing research has shown that how problems are initially defined and framed can create a path dependency in how leaders think about improvement (Mintrop and Zumpe, 2019). In this study, we found that pressing leaders in their first term to identify an equity-focused PoP and to continually apply their learning about IS, culture, and identity to that problem enabled students to engage with, problematize, and begin to revise their existing assumptions. An applied approach also enabled faculty to recognize students’ incoming assumptions and utilize the class context to provide feedback and critical questions to help students question existing assumptions.

The findings also reveal some unresolved teaching and learning challenges, suggesting implications for future research and program adaptations. Firstly, to identify an equity-focused PoP is to wrestle with tensions in problem scope. Leaders need to be able to both think about problems broadly—to recognize enduring equity issues in our system and their structural contexts—while also thinking about problems more specifically and concretely—to identify a narrower actionable problem ‘of practice’ in their contexts. For our participants, one term in a doctoral program was sufficient to productively struggle with, but not resolve, this tension. Future research could help conceptualize this tension and theorize potential learning tasks and processes through which students might navigate it to identify an equity-focused PoP that is the right grain size for disciplined inquiry.

Another teaching and learning dilemma lay in the sources of evidence students used to initially identify PoPs. We asked students to identify a PoP by first giving an elevator pitch and then examining available local organizational data and research literature. These moves had the intentions to help students surface and then move past intuitive assumptions to become more evidence-informed and invite context specificity into their thinking. While students read about steps to consult users in their organizations—such as through empathy interviews—they would not be supported to practice these methods until later in the program. In the first term, by requiring students to seek out readily available organizational data, we may have encouraged them to rely on administrative data and external accountability metrics that tended to reinforce deficit ideologies in their early problem framing. Adding to this, having a requirement to search literature soon after initially identifying a problem may have encouraged students to perceive that defining and diagnosing a PoP is a matter best handled by external authorities, such as policymakers and researchers, rather than by educators and the communities that they serve.

In these ways, the program asked students to first tap into the thinking that the current system invites—and then, in short order, challenge it to try to unlearn these ways of thinking. While this may have been generative to some extent, this tight timeline of learning and unlearning also may have limited the depth of their learning. To avoid the potential of reinforcing typical leadership mindsets, leadership programs and future research might explore the potential for whether leaders may initially define and frame their problems in more practice-focused and user-centered ways if they begin their improvement journeys with empathy interviews and other local needs assessments that focus them on the internal perspectives and processes in their organizations (Mintrop, 2016).

Finally, the findings call for further exploration for how to support doctoral students to engage in collaborative inquiry. Collaboration, rather than unilateral decision making or isolation, is core to any critical IS process. Solving educational inequities will require a joint effort from educational leaders, scholars, and the communities they serve. As a cohort-based model with a summer residency, our Ed.D. program provided some structures to ensure that the educational leaders learn in communities of practice. In the first term, reading and tasks that raise awareness of leaders’ needs to engage users and diverse community members in identifying and diagnosing the problem enabled emerging shifts in how leaders understood their role. However, currently, the program does not do much to support leaders to apply this understanding in the first term. Deeper mindset shifts may be enabled if students are pressed to collaborate with others in their organizations earlier on in their improvement journeys during initial efforts to identify and diagnose a PoP.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of the need to protect participants’ privacy. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to ZWxpemFiZXRoLmEuenVtcGUtMUBvdS5lZHU=.

Ethics statement

The requirement of ethical approval was waived by the University of Massachusetts Lowell Institutional Review Board for the studies involving humans because the University of Massachusetts Lowell Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

EZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing−original draft, Writing−review and editing. PU: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing−original draft, Writing−review and editing. AH: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing−original draft, Writing−review and editing. SS: Formal analysis, Validation, Writing−original draft, Writing−review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the Financial support for publication was provided by the University of Oklahoma Libraries’ Open Access Fund.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our doctoral students who gave their time to participate in the study and review the results and who allowed us to more deeply understand their learning. We would also like to thank Derrick Dzormeku for assistance in collecting data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1426126/full#supplementary-material

References

Anderson, E., and Davis, S. (2023). Coaching for equity-oriented continuous improvement: Facilitating change. J. Educ. Change 25, 341–368.

Anderson, E., Cunningham, K. M., and ddy-Spicer, D. H. E. (2023). Leading continuous improvement in schools: Enacting leadership standards to advance educational quality and equity. Milton Park: Taylor & Francis.

Anderson, G., and Herr, K. (2015). New public management and the new professionalism in education: Framing the issue. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 23:84. doi: 10.14507/epaa.v23.2222

Au, W. (2016). Meritocracy 2.0: High-stakes, standardized testing as a racial project of neoliberal multiculturalism. Educ. Policy 30, 39–62.

Biag, M., and Sherer, D. (2021). Getting better at getting better: Improvement dispositions in education. Teach. Coll. Rec. 123:2598.

Braaten, M., Bradford, C., Kirchgasler, K. L., and Barocas, S. F. (2017). How data use for accountability undermines equitable science education. J. Educ. Admin. 55, 427–446. doi: 10.1108/JEA-09-2016-0099

Brown, J., Collins, A., and Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educ. Res. 18, 32–42.

Bryk, A., Gomez, L. M., Grunow, A., and LeMahieu, P. G. (2015). Learning to improve: How America’s schools can get better at getting better. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Cochran-Smith, M., and Keefe, E. S. (2022). Strong equity: Repositioning teacher education for social change. Teach. Coll. Rec. 124, 9–41. doi: 10.1177/01614681221087304

Copland, M., and Knapp, M. S. (2006). Connecting leadership with learning: A framework for reflection, planning, and action. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Darling-Hammond, L., Meyerson, D., LaPointe, M., and Orr, M. T. (2009). Preparing principals for a changing world: Lessons from effective school leadership programs. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Datnow, A., and Park, V. (2018). Opening or closing doors for students? Equity and data use in schools. J. Educ. Change 19, 131–152. doi: 10.1007/s10833-018-9323-6

Dedoose (2018). Web Application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC.

DeFilippis, K. (2023). “Towards synergistic critical race improvement science,” in Continuous improvement: A leadership process for school improvement, eds Erin Anderson D. Sonya Hayes (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, Inc), 3–16.

Diemer, M., and Blustein, D. L. (2006). Critical consciousness and career development among urban youth. J. Vocat. Behav. 68, 220–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2005.07.001

Diemer, M., McWhirter, E., Ozer, E. J., and Rapa, L. J. (2015). Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of critical consciousness. Urban Rev. 47, 809–823. doi: 10.1007/s11256-015-0336-7

Dixon, C. J., and Palmer, S. N. (2020). Transforming educational systems toward continuous improvement: A reflection guide for K–12 executive leaders. Princeton, NJ: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Eddy-Spicer, D., and Gomez, L. M. (2022). “Accomplishing meaningful equity,” in The foundational handbook on improvement research in education, eds J. P. Donald, J. L. Russell, L. Cohen-Vogel, and W. R. Penuel (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield), 89–110.

Farley-Ripple, E. (2012). Research use in school district central office decision making: A case study. Educ. Manag. Admin. Leadersh. 40, 786–806. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1423-5

Fiske, S., and Taylor, S. E. (2013). Social cognition: From brains to culture, 2nd Edn. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

French, R. (2016). The fuzziness of mindsets: Divergent conceptualizations and characterizations of mindset theory and praxis. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 24, 673–691.

Galloway, M. K., and Ishimaru, A. M. (2015). Radical recentering: Equity in educational leadership standards. Educ. Adm. Q. 51, 372–408.

Garcia, S., and Guerra, P. L. (2004). Deconstructing deficit thinking: Working with educators to create more equitable learning environments. Educ. Urban Soc. 36, 150–168.