95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 19 July 2024

Sec. Leadership in Education

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1416666

This article is part of the Research Topic Educational Leadership and Sustainable Development View all 6 articles

University tutoring programs should aim to create a conducive environment for promoting pedagogical practices that align with the principles of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). However, it has been observed that teachers often face difficulties when implementing ESD in tutoring sessions, such as lack of time, students’ reluctance to share personal issues, and insufficient training and resources. This research is part of a larger project that aims to study university tutoring as a pedagogical tool to identify problems affecting students’ learning processes and provide solutions to improve the quality of teaching. As participatory and dialogical models are most appropriate for promoting ESD, a well-developed tutoring model will contribute to the creation of useful pedagogical practices to guide and improve the status quo of students. Through an exploratory-descriptive study, this paper compares two university tutoring programs in Spain and Morocco to identify the most frequent issues hindering educational leadership and sustainable development, which can impact academic success.

The research presented here is part of a larger ongoing international project involving other countries (Australia, Barbados, England, Morocco and the USA) that focuses on the importance of university tutoring as a pedagogical tool to identify conflicts and problems affecting students’ learning process to generate a shared vision committed to sustainability, as well as align practices and institutional approaches with the principles of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). The work is part of the Research Project (RED/ICE 5771–2023–2024) of Alicante University, and it tackles different actions that can be implemented to achieve the fourth Sustainable Development Goal (SDG4) of the 2030 Agenda signed by all members of the United Nations in 2015.

This study aims to analyze the most challenging issues encountered by students enrolled in the Early Childhood and Primary Education degrees at Alicante University in Spain and L2 students studying different degrees at the Euro-Mediterranean University of Fez in Morocco. Data collection is taken directly from the questions raised during university tutoring sessions in both universities. The main objective is to improve and provide a well-rounded and comprehensive support system to students. Drawing from tutors’ experiences, this research examines the issues requiring more urgent attention and guidance to respond most effectively to students’ needs. Ultimately, this case study will enable us to identify areas for improvement in the quality of learning.

The theoretical underpinnings of this study rely on previous research about the importance of university tutoring and the need to approach this topic as a multidisciplinary and complex research area. Those works have identified and corroborated that tutoring at university has three key dimensions: ‘personal-social’, ‘academic’ and ‘professional’ (Sallán et al., 2004; García Nieto et al., 2005; Lobato et al., 2005; Thomas and Hixenbaugh, 2007; McChlery and Wilkie, 2009; Wisker et al., 2013; Hagenauer and Volet, 2014a,b,c, López-Gómez, 2015, 2017; Martínez Clares et al., 2019; López-Gómez et al., 2020). Therefore, to establish a sustainability strategy for university quality learning, it is crucial to analyze the above-mentioned three dimensions and develop a vision and objectives accordingly. Tutoring programs can assist in this process by identifying specific actions, monitoring progress, and evaluating efforts and achievements. This approach will ensure that sustainability is prioritized and effectively integrated into university pedagogical practices.

Within the university framework, our research is rooted in the concept of “sustainability”. This concept enables us to identify students’ challenges and concerns, allowing institutional efforts to prioritize academic development through tutoring programs and dedicated tutors. Drawing from the work of Fernández Mora et al. (2021), sustainability involves analyzing situations with the goal of maintaining or achieving minimum levels of well-being. Consequently, the commitment of 21st-century universities extends to social sustainability, as emphasized by Escámez-Sánchez and Peris-Cancio (2021).

From a methodological point of view, the process was divided into two stages. The first stage involved creating an ad hoc questionnaire based on a qualitative content analysis of participating teachers’ experiences during the tutoring sessions. The items composing the questionnaire were organized into three blocks, following previous studies mentioned: (1) Socio-cultural, personal and health issues (physical and mental), (2) Administrative and bureaucratic processes in academic contexts, and (3) Curricular and teaching issues. All the researchers involved in the larger project collaboratively elaborated, supervised, reviewed, and agreed upon the questionnaire. Once the study is finalized, it will be registered in OER Commons to allow free access to the research community.

In the second stage, each researcher responsible for each participating country examined their context using the collaboratively created questionnaire to gather data about the issues affecting students living in different socio-economic and cultural settings. Such information allowed us to compare the diverse educational environments and reveal overlapping and diverging themes connected to the idiosyncrasies of the territories investigated. The period selected ranges from the so-called ‘post-pandemic’ period up until 2023.

Tables 1–4 were designed to provide data for qualitative analysis in a statistical study. In this phase, these tables serve as a framework for organizing significant data, enabling the identification and analysis of the most frequent and impactful issues. The data collection process involved gathering written messages via email or the tutoring program chat. Additionally, during face-to-face interactions, tutors diligently recorded the issues raised by students in a diary. This information was meticulously collected using the narrative-biographical method, ensuring reliable organization, examination, interpretation, and understanding (Rodríguez Ortiz, 2020).

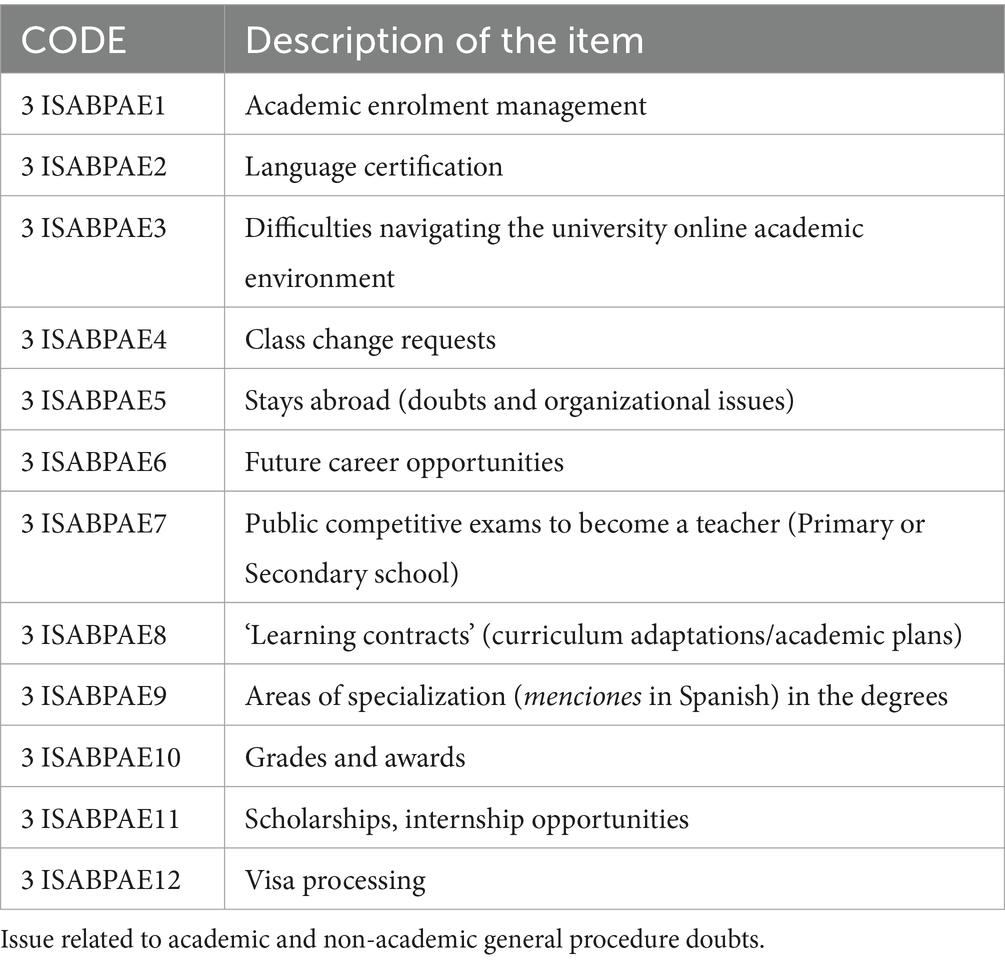

Table 3. Issues related to administrative and bureaucratic processes of academic environments (ABPAE).

Consequently, the evidence was constructed from written discursive elements. These discourses—whether conveyed through email or university platforms/chat—represent an academic tutoring practice, viewed through the lens of personal impact. This impact encompasses mental and physical health, emotional well-being, bureaucratic challenges, and inclusion within the university classroom. The data is further organized using the tables created (Tables 2–4).

Applying the Critical Discourse Analysis of Written Discourse (CDAE) proposed by Fairclough (2003), we examine discourse `with an attitude,’ focusing on the student body in both social and personal dimensions. By considering students’ experiences and opinions within the academic context, we gain valuable insights. It is essential to review written messages with an awareness of biases that may reflect varying conceptions of academic situations based on individual values, beliefs, and customs. Ignoring these nuances could lead to inconclusive findings.

Furthermore, we employed a qualitative-observational method (Eisman, 1997) to collect specific information during face-to-face tutoring sessions with students, facilitated by the tutor’s active involvement. In this research study, direct observation of students occurred during oral tutoring sessions, typically held in the tutor’s office or a designated classroom. The data was meticulously recorded and documented through a systematic examination of oral discursive elements.

Our qualitative methodological approach, rooted in Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), aimed to capture the socio-affective dimension inherent in these face-to-face interactions with mentees. During tutoring sessions, the tutor documented spoken content and observations using notes, avoiding the stress of directly recording the student. These notes were then transcribed into the relevant tables (Tables 2–4).

Our data analysis considered both written and oral discourse, focusing on the recorded items, their expression, and the student profiles. Additionally, we took into account extra-linguistic and psychological factors that accompanied the discourse, shedding light on the degree of concern, dissatisfaction, or doubts expressed.

The data collection methods and table creation were collaboratively agreed upon by the research team. The responsibility for data collection and entry into the tables rested with the tutor-teachers from both universities. The information presented in this study is part of ongoing research involving other universities (such as Barbados and Sydney). To protect student identities, the data obtained has not been explicitly linked to specific individuals. Furthermore, both universities have endorsed this research through their respective ethics committees.

The information obtained from the students has not, in any case, been expressly linked to specific subjects to preserve their identity. On the other hand, both universities have endorsed the research through the ethics committee.

We believe this study will contribute to advancing knowledge on university tutoring as a pedagogical tool for enhancing the quality of education. Its positive contribution is twofold. On the one hand, it offers a reliable analysis tool developed as an open educational resource that allows for modification and reuse, providing benefits without limiting the possibilities of others, which is in line with the guidelines set by the OECD (2008). On the other hand, it will provide a comprehensive overview of the most prominent struggles impacting higher education students in each country. More importantly, it will facilitate teachers’ reflections on the future implementations needed to improve the university tutoring practice so that educators can help students overcome their biggest burdens and thrive both academically and in other areas of their lives. Therefore, this work promotes sustainable learning based on meaningful and long-lasting teaching through effective classroom practice addressing the needs of all students.

In recent decades, López-Gómez et al. (2020) have highlighted the increasing prominence that university tutoring has gained over the years. Despite this research area having adopted different approaches, theoretical frameworks and methodologies, there has been consensus on the urgency of investigating this complex topic and its numerous perspectives.

The study presented here is grounded in the premise that students’ needs and concerns can vary based on their academic year. Our primary research objective encompasses two key aspects. First, we aim to comprehensively collect the circumstances and issues students encounter during tutoring sessions, without discriminating based on their field of study or academic level. These collected data will inform future statistical research, where we create tables to organize the items. Secondly, we focus on assessing impact by quantifying how frequently specific issues recur during tutorial hours. This statistical perspective allows us to prioritize certain items while excluding others that may not significantly contribute to the study.

Our work will enable subsequent research to evaluate the impact of these collected items across various variables, including the student’s year of study, field of study, gender, socio-cultural background, family environment, and economic status. Given the above and following previous research, we consider the sociocultural and personal aspects to be crucial, as individuals acquire their values, beliefs, customs, and traditions not only from the society where they currently live but also throughout the socialization process experienced in transcultural contexts, as seen in today’s globalised society.

Given the above and following previous research, we consider the sociocultural and personal aspects to be crucial, as individuals acquire their values, beliefs, customs, and traditions not only from the society where they currently live but also throughout the socialization process experienced in transcultural contexts, as seen in today’s globalized society. Similarly, we underscore the importance of the academic dimension but differentiate between administrative and bureaucratic processes in academic environments (such as enrolment, timetables, academic plans, etc.) and issues related to classroom teaching practices (such as providing simple extensions, further explaining concepts, identifying areas of improvement, etc.) as important dimensions of it.

Additionally, we contend that along these top priorities, physical and mental health issues are paramount in providing students with well-rounded support and guidance since they can represent a significant burden for learning. Although some authors mention these aspects, their true significance is not emphasized enough. However, migratory movements and ongoing health issues since the COVID-19 pandemic have made it inevitable to bring these dimensions to the forefront.

On the other hand, even though we acknowledge the significance of the professional dimension (professional interests and skills required, competitive exams, unemployment, emancipation, economic solvency, etc.), we decided not to address it as a separate dimension because it tends to affect mostly the last year or last 2 years of students’ university degree. For this reason, it has been included in the bureaucratic-administrative dimension.

In our research, we carefully considered two distinct factors. First, we examined the organizational differences between two university institutions—one public and the other private. Second, we explored the socio-cultural and economic disparities between the countries where these institutions are located. Our initial hypothesis was that these factors would lead to clear variations in concerns, needs, or doubts. However, by choosing them as the starting point, we aimed to determine whether common issues persisted despite the unique characteristics of each country. Ultimately, our goal was to identify similarities or differences in demands and issues related to tutoring sessions. In the realm of higher education, investigating university tutoring situations established between groups from different countries and with varying institutional concepts (public/private) holds significant relevance. Such cross-cultural studies allow us to construct a globalized profile of students’ needs from both academic and sociological perspectives (Aguiar, 2007), Notably, the study conducted by Llanes et al. (2021) serves as a valuable precedent. By measuring the motivation and academic satisfaction of university students with an international vision, Llanes et al. shed light on the impact of diverse socio-cultural and economic environments—specifically in Europe and Latin America. Additionally, Díaz-Camacho et al. (2022) contribute to this discourse by presenting an international systematic review of student satisfaction across 50 studies. Their work provides insights into the factors influencing student contentment within the university community, transcending geographical boundaries. Similarly, Ochnik et al. (2021) explore the mental health of university students in nine countries during the COVID-19 pandemic, emphasizing the importance of considering personal well-being alongside academic outcomes.

In summary, these studies share a common thread: they delve into mood, motivation, and personal factors that impact academic results among university students from diverse cultural backgrounds. By understanding these dynamics, we can better tailor tutoring programs to meet the unique needs of an increasingly globalized student population.

This research article aims to provide an understanding of the importance of quality tutoring programs in addressing our biggest sustainability challenges, as well as approaches to achieving quality teaching. It delves into emerging themes by examining questions and issues that students often bring up during tutoring sessions. We will present a model based on a real case study, to improve the quality of tutoring programs for future professionals and contribute to a more positive future.

Most of the research conducted on the tutoring process in the university context has employed questionnaires to analyze the perceptions of students and teachers quantitatively (López-Gómez et al., 2020). However, in this investigation, such individuals’ profiling (e.g., gender, age, nationality, etc.) or their assessment of the tutoring process is not the focus. This work, instead, is an exploratory-descriptive study aiming to qualitatively analyze teachers’ experiences during their tutoring sessions to explore salient issues concerning and affecting the learning experience of university students. It is an innovative proposal that invites educators to consider how to organize tutoring sessions to positively impact the future of students. Thus, using instructors’ experiences, the focus here is on students’ concerns and struggles that might hinder their academic performance. In consequence, although theoretically, this study builds on previous research (García Nieto et al., 2005; García, 2019; Guerrero-Ramírez et al., 2019; Klug and Peralta, 2019; Vélez et al., 2019; Di Vita et al., 2021; Vallejo and Molero, 2022), methodologically has a different orientation.

For this reason, questionnaires have not been administered to instructors or students. In turn, data obtained through teachers’ experiences during tutoring practices has formed the basis for the design of a ‘monitoring form’ (Richards, 1988; Bazhenov et al., 2015). The items composing it, as we will detail in the methodology section, have been carefully selected to accurately capture the most pressing issues that impact students’ learning process as well as potential remaining challenges, which is in line with the UN Agenda 2030. Once validated, the ‘monitoring form’ has subsequently allowed for a detailed examination of each participating country, which has enabled us to conduct a contrastive-descriptive analysis and compare our results with previous works (Dörnyei and Taguchi, 2009). Having an effective monitoring form enabled an objective and rigorous evaluation of data. Research manuscripts, reports, and monitoring forms will be deposited on OER COMMONS Open Educational Resources.

As anticipated, the methodological design chosen for this project consists of an exploratory-descriptive, with an approach based on qualitative-narrative and qualitative-observational. The study used content analysis to develop a ‘monitoring form’ aimed at understanding the factors affecting students’ performance at the university level (Creswell, 2013; Mackey and Gass, 2015; Creswell and Creswell, 2017). We have opted for a qualitative methodology because we wanted to conduct an in-depth analysis of the phenomenon in its natural context. Therefore, given its interpretative nature and the focus on understanding the meanings people assign to their experiences (Shava et al., 2021), we considered this approach the most suitable for our objective.

Building on Landín and Sánchez (2019) work, the narrative-biographical method offers a unique lens through which we can explore knowledge related to tutoring practice. Like previous work, we recognize that this method enables us to capture authentic subject knowledge derived from lived experiences. Specifically, it sheds light on the dynamics within university spaces during students’ academic journey, allowing us to grasp the genuine essence of tutoring practice.

We were not interested in counting words but in examining meanings, themes and patterns that might be manifest or latent in teachers’ reflections on their experiences during tutoring sessions. Therefore, qualitative content analysis, one of today’s most extensively employed research methods fruitfully used in the educational sphere, was deemed the most appropriate. Such a method involves a systematic coding and categorization process aiming to explore vast volumes of textual information unobtrusively to determine trends and patterns of words used, their relationships, and the structures and discourses of communication (Nunan, 1992).

We will proceed to explain in detail the two phases of this study. The first one is devoted to explaining the design process of the ‘monitoring form’. The second one is specifically related to the case study presented here, which aims to compare the biggest challenges faced by students from Alicante University (Spain) and the Euro-Mediterranean University of Fez (Morocco) since the COVID-19 pandemic until 2023. Importantly, the case study also served as a way to validate the trustworthiness questionnaire.

The monitoring form is a written document that each research member completed to document specific information. There are three primary reasons for monitoring: (1) to set targets and standards, (2) to identify deviations from expected results and make necessary adjustments, and (3) to provide feedback to stakeholders on areas that need improvement.

Bazhenov et al. (2015) analyze the components of tutoring monitoring as a management tool for higher education institutions to identify issues and explore the potential applications of monitoring for future research. The study reveals that while there are many studies on tutoring and monitoring techniques have also been widely used in education for a long time, insufficient attention has been paid to the direct impact of both to investigate the quality of education. Therefore, the use of monitoring as a methodological tool for assessing higher education quality should take into account the existing conditions and must be correctly used to improve the education process and its outcomes. It is important to note that monitoring is not a universal tool, but if used appropriately, it can significantly enhance the effectiveness of education quality.

The design was a collaborative daunting task that took a significant amount of time and involved different stages in which raw data was divided into manageable units through several iterations. For the items, data was gathered from teachers’ reflections on their experiences during tutoring sessions. These reflections were collected in the form of diaries or written annotations. To collect data, we used direct observation and narrative methods, as we explained, given that those techniques involve delving deeply into social and academic situations with an active role and continuous data evaluation assessment (McMillan and Schumacher, 2005). Such a technique enabled us to record the issues reported by students as they expressed them, which helped to minimize possible errors or inaccuracies. Thus, data were collected considering two factors:

− Information was obtained from the tutor’s diary, which in some cases also included students’ questions sent via email or in the tutoring space of some university websites.

− Specific queries raised by the students during the tutoring sessions were described and reported verbatim.

For the preparation of the questionnaire, we followed and adapted McMillan and Schumacher (2005) research presented (Table 5). By selecting students who are most frequently raised questions and defining the method and place to collect them, we have guaranteed the validity and reliability of the study. Usually, validity can be reflected from two aspects: findings and instruments (Paltridge and Phakiti, 2018). For the validity of findings, internal and external validity should be considered, as Paltridge and Phakiti explain (2018). These types of validity involve different aspects in research design, in our case, we focus on participant characteristics and profile, data collection and the instrumentation, as well as the external validity that it is refers to the extent to which results from a study can be applied to other context or groups (Mackey and Gass, 2015).

Table 6 show the results of the validity investigation in the research. Only 69.78 and 65.53% (n = 224 and n = 154) of the tracking sheets examined can be validity instruments used in the topics proposed in the tutoring, with those reported most frequently being those in the category CTE (n = 85, 26, 48% and n = 65, 20.25%). The monitoring forms classified in the ABPAE category do not require much concern for validity testing because they are not plenty (n = 13, 4.04% and n = 8, 2.49%). No studies categorized under other classifications demonstrated need about validity testing. For this reason, they were excluded from these tables. Among them, concerns about the professional future or the end-of-study projects of the degree.

As mentioned, we aimed to reveal unique themes illustrating the diversity of obstacles impacting students’ academic performance with a sustainable object. The qualitative approach typically employs inductive reasoning, where themes and categories emerge from the data through the researcher’s careful examination and constant comparison. However, as Creswell (2015) argues, qualitative content analysis is a flexible method that can use inductive reasoning but also deductive or a combination of both in data analysis (Hernández de la Torre and González Miguel, 2020).

From the different approaches, we used direct content analysis Hsieh and Shannon (2005), a deductive approach involving initial coding based on previous research findings. This approach facilitated a more structured research process and provided indications about the major concerns of students or the relationships among them. It also helped us determine the initial coding scheme or relationships between codes, as noted by Mayring (2000). Thus, teachers’ reflections were written using the following predetermined categories: (1) Sociocultural, personal and health-related (physical and mental) issues; (2) Administrative and bureaucratic processes in academic contexts; and (3) Curricular and teaching-related issues.

As we also anticipated in the preliminary considerations section, some categories were taken from previous studies, while the research group added others. Once collected, the data was reviewed thoroughly by each participating researcher, allowing for the identification of relevant sections of texts to be classified into categories as well as initial themes, which then guided the development of a preliminary coding system as Creswell and Poth (2016) and Saldaña (2013) explained.

During the analysis, teachers’ notes were thoroughly reviewed, and all the highlighted passages were coded based on predetermined categories. Any text that could not be classified with the initial coding scheme was given a new code. Uncoded data was analyzed later to determine if it represented a new category or subcategory of an existing code. The coding process involved applying the coding system to all collected data. Each piece of data was analyzed line-by-line with codes assigned to relevant sections of text. This process was iterative, allowing for the refinement of codes as new insights emerged (Saldaña, 2013). The coded data was then analyzed to identify relationships, patterns, and themes among the codes. This analysis aimed to uncover deeper meanings and implications within the data, providing the basis for developing the questionnaire (Dörnyei and Taguchi, 2009; Saldaña, 2013; Mackey and Gass, 2015).

The direct approach to content analysis is beneficial in supporting and expanding existing theories as Weber (1990) advised. However, it also has some limitations, as researchers may have a strong bias when approaching the data. To overcome these limitations and achieve credibility, Graneheim and Lundman (2004) suggest strategies such as member checking, showing representative quotations, or peer debriefing. In our case, each author conducted their own content analysis. We then compared our codes, themes, and analyses to ensure consistency. To increase the consistency, reliability, and validity of the questionnaire, we conducted several rounds of coding, theme definition, and classification together until we reached a consensus.

We decided to compare Spain and Morocco because of two main factors: (1) their geographical proximity and important Moroccan community living in Spain as well as the bilateral relations between both nations (Amirah Fernández, 2015; Zebda, 2021) and (2) the growing cross-cultural interchange since 1913, as explained in the recent publication El mundo estudia español. As a result of the increasing cultural exchanges, a Moroccan Board of Education was constituted to coordinate the different bodies involved in the promotion of the Spanish language and culture in the country. Such an educational action lasted until the independence of Morocco in 1956, and after a period of inactivity, it resumed its activity in the 80s (Lluch Andrés and Pilar Narros, 2022). Thus, different students’ degrees and ages were chosen as variables to better observe the impact of the tutoring process. For data analysis and comparison, we use MAXQDA (Rädiker and Kuckartz, 2021; López et al., 2022), professional software for qualitative and mixed methods data analysis.

We employed the questionnaire (see Tables 1–4) to collect data from two universities, namely the Faculty of Education of the University of Alicante (Spain) and the Euro-Mediterranean University of Fez (Morocco), during the academic year 2020–2022. The Euro-Mediterranean University of Fez is a small government-dependent private university located in Fez, founded in 2012, with an enrolment of 2,006 students. On the other hand, the Universidad de Alicante, founded in 1979, is a very large public university located in San Vicente del Raspeig with 25,063 students enrolled (latest data available in Multirank University Compare) and is one of 76 universities included in U-Multirank for Spain. The total number of tutors is 444 students (328 from Alicante and 116 from Morocco), and only 18 to 20% of them actively participate in tutoring programs, which is the data collected. The gender of the informants is not explicitly considered.

In Spain, the study involved first and third-year students who were enrolled in the degree programs of Primary Education and Early Childhood Education. Most of the participants (85%) were aged between 17 and 24, while 12% were between 24 and 35, and the remaining 3% were over 35 years of age. All the students were born in Spain, thus there were no foreign students in the study. Spanish was the vehicular language of all participants, while Valencian and English languages were compulsory depending on the degree.

In Morocco, we considered students of Spanish as an additional language. They have French and Arabic as their native language. In this educational context, Spanish is compulsory for all university students, from the first year to the last year of a master’s degree. Participants were studying Spanish as part of a variety of degrees, including engineering, tourism, design, political science, and economics. Their ages ranged between 17 and 25 years, with 10% of them being students from France, Ukraine, Haiti, Tunisia, and sub-Saharan Africa.

In Tables 1, 2, the information refers to sociocultural, personal (family) and health-related (physical and mental) issues impacting students. Within this dimension, depression, stress, and anxiety were the most prominent areas. Problems of restlessness, mental blocking and poor emotional management also stand out as areas of interest in the tutoring space. Regarding the sociocultural and personal aspects, family situations (especially illness or death of a family member) and the impossibility of balancing work and family life were the most recurrent problems.

In the Table 3, which deals with administrative and bureaucratic processes in academic contexts, showed that enrolment processes and language certification issues are critical for students. In this context, for instance, having a high level of the Valencian language is a requirement to sit the competitive examinations needed to become a teacher in the Valencian Community. Consultations on career opportunities, competitive exams, and areas of specialization, ‘menciones’ in Spanish Degrees (Arruti Gómez and Paños Castro, 2019), are recurring, highlighting the need for guidance in planning their academic careers. The bureaucracy of stays abroad, information on scholarships and internship opportunities are also highlighted as areas in which students seek guidance. Thus, tutoring seems to be seen as a great space to discuss career prospects and help students align their academic choices with their professional goals. Such findings reveal the crucial role of university tutoring (Sutherland, 2009) in facilitating these processes and promoting enriching experiences for academic (Billett and Henderson, 2011) and professional development.

Finally, the third dimension explores curricular and teaching-related issues (Table 4). Results highlighted problems with assessment, difficulties navigating the university web page and finding the right and relevant information, as well as concerns about the Final degree projects and Final master projects. Data also indicated that students face challenges in various aspects of the curriculum and classroom environment (Alismail and McGuire, 2015). Lack of social and cultural identity is not presented as a significant concern. Additionally, problems with teachers, classmates and the methodology used are aspects for which students seek support and mentoring.

Students’ perceptions of university tutoring (Grey and Osborne, 2020) as a space to mainly tackle academic issues related to the classroom, coupled with the lack of information about its purpose, indicate the pressing need for educators to improve communication with students on the scope and benefits of tutoring. After analyzing the data collected, it was found that students at the University of Alicante have specific needs. Unlike in other participating contexts of the broader project (forthcoming), issues related to visa processes, housing, cultural integration, sexual orientation, xenophobia, or problems of isolation due to racism are not reported in Spain.

In the case of Morocco, within the first dimension, although students attending tutoring sessions reported physical health problems, this percentage is relatively low compared to mental health problems, highlighting the importance for teachers to address anxiety and stress issues during this mentoring space. Moreover, complex familiar and personal situations, such as family conflicts, economic problems, and concerns about the illness of loved ones or death, are also observed. Additionally, several students reported feelings of lack of integration or social acceptance, uprooting, rejection, or isolation because of their social or cultural identity or sexual orientation. These factors underscore the need for university tutoring to focus not only on academic aspects but also on students’ socio-cultural and personal realities, providing well-rounded support and guidance.

The second dimension dedicated to the administrative and bureaucratic processes related to students’ academic life (Arbaoui and Oubouali, 2020) also identified questions about language certification (Fernández, 2021). However, for a large part of the student population, the management of stays abroad is a major concern, indicating the need for guidance in logistical and academic aspects related to these international experiences. Consultations on internship and career and scholarship opportunities are also frequent, underlining the importance of targeting issues related to vocational counseling and the connection between academic formation, career prospects and access to academic development opportunities during the tutoring sessions.

Finally, data from the third dimension revealed student’s challenges in their academic and curricular environment. Students demanded clarification on the methodological aspects of Spanish as an additional language subject, and they also reported problems with exams, including mental block and anxiety. Thus, in this context, university tutoring should adopt a proactive and personalized approach, considering the diversity of the disciplines represented in the university and respecting the cultural particularities of Moroccan students, such as sensitivity to issues of sexual orientation and gender.

Overall, the Euro-Mediterranean University in Fez presents a complex landscape in which tutoring becomes a vital pedagogical tool for addressing the highly diverse students’ needs. From mental health support to guidance in administrative processes and academic development, university tutoring emerges as key to improving the student learning experience and the quality of education in this educational setting. By adapting to the cultural idiosyncrasies of Moroccan students, tutoring can contribute significantly to the achievement of the goals of the 2030 Agenda in the field of education.

The comparison of the data collected through the questionnaires in both universities reveals similarities and differences in the university students’ needs and experiences. The student profile is quite similar in both institutions; however, in Spain, it presents a broader age range, including 10% of students aged 24 and more than 35 years, which suggests a wide diversity of life experiences.

Concerns about mental health issues are prevalent among students in both countries, reporting problems of depression, stress, and anxiety in the two universities. However, in Morocco, the two latter are more prominent. In addition, family issues, difficulties in balancing work and family life, and economic problems are identified as factors affecting students in both institutions. At the personal level, in the Moroccan educational context, we found cases of students presenting problems of uprooting, lack of integration with their peers and distrust. Additionally, unlike in Spain, problems of social and cultural identity as well as sexual orientation also manifest themselves in Morocco, leading to students’ feelings of rejection and isolation. These data highlight the critical need for tutoring interventions that address not only academic aspects but also the sociocultural and personal complexities that impact student well-being.

In terms of administrative and bureaucratic processes, difficulties during the enrolment process and language certification are common concerns in both institutions, but there are notable differences in the areas that interest students the most. At the University of Alicante, there is a strong demand for career guidance, while students from the Euro-Mediterranean University of Fez show a greater interest in managing stays abroad. In the curricular and teaching dimension, students reported facing similar challenges, such as difficulties with assessments, navigating the university web page and problems with teachers. However, the most significant concern for students in Morocco is the insecurity of speaking in public due to mental block and stress resulting from a lack of confidence or fear of looking foolish. Students in Spain, on the contrary, are more concerned about the difficulties with the classroom methodology, explanations, or lesson planning. These differences indicate the necessity of specific tutoring interventions tailored to each institution’s unique needs and cultural particularities.

In short, while there are evident similarities in mental health concerns, administrative processes and academic challenges, the differences reflect the particularities of each university context and its socio-cultural environments. The implementation of tutoring strategies adapted to the particularities of each institution can contribute significantly to the improvement of students’ learning processes and the quality of education at the university. These strategies, aligned with the principles of the 2030 Agenda, must comprehensively and sustainable address the diverse needs of students according to their local contexts, thus fostering a more inclusive university that prioritizes not only academic growth but also student wellbeing.

The two initial goals presented at the outset of this research have been accomplished. On the one hand, we have offered a reliable analysis tool based on university teachers’ experiences during tutoring sessions in two countries (Morocco and Spain), for those interested in exploring the role of university tutoring in student academic and personal sustainable growth.

On the other hand, we have presented a case study involving Spain and Morocco, which offers an overview of the current situation of university tutoring in these two geographically close but socio-culturally different countries, as well as their degrees.

Findings have shown that university tutoring is crucial to addressing sustainability and quality in the academic context because facilitating approaches trigger social, personal, administrative and bureaucratic processes and improves the curriculum and students’ learning experience. Results also pinpoint specific areas of intervention to strengthen the tutoring function and contribute to improving the quality of education in university settings, in alignment with the fourth goal of the 2030 Agenda (Franco et al., 2019; Ruiz-Mallén and Heras, 2020; Chankseliani and McCowan, 2021; Fia et al., 2023).

The case study report confirms that research on tutoring must be underpinned by a solid theoretical framework and methodological design. Researchers must carefully think and agree on the methodology, the variables and the approach that best fits the research objectives to obtain reliable data. This study also corroborates the need to explore three dimensions of tutoring to measure the quality and sustainability of the university experience: academic, sociocultural, and psychological. Moreover, institutions conducting this kind of research must have a tutoring system in which students play an active role and instructors are fully committed to enhancing both academic and tutoring tasks.

The study found that some problems faced by students are closely linked to the culture, society, and idiosyncrasies of their respective countries. However, other issues affecting students from both Spanish and Moroccan universities are attributed to a globalized and post-academic world. While the generalisability of these results is subject to a larger sample, they provide valuable insights for future research. Nevertheless, to establish whether the conclusions drawn in this study apply to a wider context, considerably further work is required in other areas of each participating country and other regions globally. Additionally, it is crucial to consider the possibility of other significant factors that may not have been considered or have yet to emerge in this research.

Overall, students come to tutoring sessions seeking help and guidance, making it a mentoring space to solve situations that often are unrelated to academic problems but stem from personal issues. However, this does not imply that all students trust the system or understand its purpose. In fact, results correspond with the difficulties existing in socio-cultural and academic contexts at large. Similarly, they usually align with the moment of the student’s academic career (either the first or last year of university) and the general conflicts occurring in each of these years.

Therefore, echoing Zabalza and Beraza (2003) and other authors (White and LaBelle, 2019; Hsu and Goldsmith, 2021), we argue that instructors must understand their role, which is no other than to guide and accompany students through their university learning journey rather than act as mere sources of information or knowledge transmitters. Instructors must be mediators who approach students not to solve their problems but to assist them in navigating them while facilitating the completion of their academic tasks. Overall, we emphasize the importance of teachers’ critical reflection on the quality tutoring action (Guerrero-Ramírez et al., 2019), a topic that, although not new, does not have a standardized, homogeneous and sustainable model for its study. This could explain the different students’ perceptions of the purpose and usefulness of university tutoring sessions based on their previous experiences with these spaces.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will not be made available because both universities did not consent to share the data for data protection purposes.

The study involving human participants had to undergo ethical review and approval to comply with legislative and institutional university requirements. Written informed consent from the legal guardian of the participants was not necessary for this type of study, as per national legislation and institutional requirements.

MVZ: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. MO-J: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. PGG: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. LS-C: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

The authors declare that financial support was received from University of Alicante for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Aguiar, D. I. (2007). La globalizacion mundial, la formación del profesional de la sociedad que viene, y el perfil requerido para el docente y el egresado universitario. Argentina: Universidad Nacional de La Plata.

Alismail, H. A., and McGuire, P. (2015). 21st century standards and curriculum: current research and practice. J. Educ. Pract. 6, 150–154.

Arbaoui, S. E., and Oubouali, Y. (2020). Implementación de sistemas de control de gestión en organizaciones del sector público: el caso de las universidades marroquíes. Rev. Contrôle Comptab. Audit 4:4.

Arruti Gómez, A., and Paños Castro, J. (2019). Análisis de las menciones del grado en Educación Primaria desde la perspectiva de la competencia emprendedora. Rev. Complut. Educ. 30, 17–33. doi: 10.5209/RCED.55448

Babbie, E., and Mouton, J. (2001). The Practice of social research. Cape Town: South Africa Oxford University Press.

Bazhenov, R., Bazhenova, N., Khilchenko, L., and Romanova, M. (2015). Components of education quality monitoring: problems and prospects. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 214, 103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.600

Billett, S., and Henderson, A. J. (Eds.). (2011). Developing learning professionals: integrating experiences in university and practice settings (Vol. 7). Springer Science & Business Media.

Chankseliani, M., and McCowan, T. (2021). Higher education and the sustainable development goals. High. Educ. 81, 1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10734-020-00652-w

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W. (2015). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. London: Pearson.

Creswell, J. W., and Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage publications.

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage publications.

Díaz-Camacho, R., Rivera, J., Encalada, I., and Romani, Ú. (2022). La satisfacción estudiantil en la educación virtual: una revisión sistemática internacional. Rev. Cienc. Soc. Humanid. 16, 177–193. doi: 10.1590/scielopreprints.2796

Di Vita, A., Daura, F., and Montserrat, M. I. (2021). La tutoría universitaria entre Latinoamérica y Europa: el caso de la Universidad Austral (Argentina) y el de la Universidad de Estudios de Palermo (Italia). Revis. Panam. Pedag. 31:2123. doi: 10.21555/rpp.v0i31.2123

Dörnyei, Z., and Taguchi, T. (2009). Questionnaires in second language research: Construction, administration, and processing. New York: Routledge.

Eisman, L. B. (1997). La investigación observacional. Métodos de investigación en psicopedagogía. Spain: McGraw Hill.

Escámez-Sánchez, J., and Peris-Cancio, J. A. (2021). La universidad del siglo XXI y la sostenibilidad social. Spain: Tirant Humanidades.

Fernández, M. B. (2021). Evolución de la política lingüística de Marruecos en el siglo XXI. Vienna, Austria: Universität Wien.

Fernández Mora, V. D. J., García Moro, F. J., and Gadea, W. F. (2021). Universidad y sostenibilidad. Límites y posibilidades de cambio social. Rev. Educ. Super. 50, 1–26. doi: 10.36857/resu.2021.199.1797

Fia, M., Ghasemzadeh, K., and Paletta, A. (2023). Cómo las instituciones de educación superior hacen lo que predican en la agenda 2030: una revisión sistemática de la literatura. Polít. Educ. Superior 36, 599–632. doi: 10.1057/s41307-022-00277-x

Franco, I., Saito, O., Vaughter, P., Whereat, J., Kanie, N., and Takemoto, K. (2019). Educación superior para el desarrollo sostenible: aplicar los objetivos globales en políticas, currículos y prácticas. Cienc. Sostenibil. 14, 1621–1642. doi: 10.1007/s11625-018-0628-4

García, J. L. A. (2019). La tutoría universitaria como práctica docente: fundamentos y métodos para el desarrollo de planes de acción tutorial en la universidad. Pro-Posições 30:38. doi: 10.1590/1980-6248-2017-0038

García Nieto, N., Asensio Muñoz, I., Carballo Santaolalla, R., García García, M., and Guardia González, S. (2005). La tutoría universitaria ante el proceso de armonización europea. Rev. Educ. 337, 189–210.

Graneheim, U. H., and Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ. Today 24, 105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

Grey, D., and Osborne, C. (2020). Percepciones y principios de la tutoría personal. Revis. Educ. Superior Continua 44, 285–299. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2018.1536258

Guerrero-Ramírez, J., Fuster-Guillén, D., Gálvez-Suarez, E., Ocaña-Fernández, Y., and Aguinaga-Villegas, D. (2019). Componentes predominantes de la acción tutorial en estudiantes universitarios. Propós. Represent. 7, 304–324. doi: 10.20511/pyr2019.v7n2.300

Hagenauer, G., and Volet, S. E. (2014a). Teacher–student relationship at university: an important yet under-researched field. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 40, 370–388. doi: 10.1080/03054985.2014.921613

Hagenauer, G., and Volet, S. E. (2014b). ‘I don’t hide my feelings, even though I try to’: insight into teacher educator emotion display. Aust. Educ. Res. 41, 261–281. doi: 10.1007/s13384-013-0129-5

Hagenauer, G., and Volet, S. E. (2014c). ‘I don’t think I could, you know, just teach without any emotion’: exploring the nature and origin of university teachers’ emotions. Res. Pap. Educ. 29, 240–262. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2012.754929

Hernández de la Torre, E., and González Miguel, S. (2020). Análisis de datos cualitativos a través del sistema de tablas y matrices en investigación educativa. Rev. Electron. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 23, 115–132. doi: 10.6018/reifop.435021

Hsieh, H. F., and Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 15, 1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

Hsu, J. L., and Goldsmith, G. R. (2021). Instructor strategies to alleviate stress and anxiety among college and university STEM students. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 20:es1. doi: 10.1187/cbe.20-08-0189

Klug, M. A., and Peralta, N. S. (2019). Tutorías universitarias. Percepciones de estudiantes y personal tutor sobre su uso y funcionamiento. Rev. Electr. Educare 23, 319–341. doi: 10.15359/ree.23-1.16

Landín Miranda, M. D. R., and Sánchez Trejo, S. I. (2019). El método biográfico-narrativo: una herramienta para la investigación educativa. Educacion 28, 227–242. doi: 10.18800/educacion.201901.011

Llanes, J., Méndez Ulrich, J. L., and Montané López, A. (2021). Motivación y satisfacción académica de los estudiantes de educación: una visión internacional. Educacion 24, 45–68. doi: 10.5944/educxx1.26491

Lluch Andrés, A., and Pilar Narros, E. (2022). El mundo estudia español 2022, Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional. Available at: https://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/mc/redele/el-mundo-estudia-espa-ol/2022.html

Lobato, C., Del Castillo, L., and Arbizu, F. (2005). Las representaciones de la tutoría universitaria en Profesores y estudiantes: estudio de un caso internacional. J. Psychol. Psychol. Theory 5, 145–164. doi: 10.5944/educxx1.7.1.333

López, C., de Lerma, G. M., and Botija Yagüe, M. M. (2022). MAXQDA y su aplicación a las Ciencias Sociales: un estudio de caso comparado sobre vulnerabilidad urbana. Alternativas 29, 48–83. doi: 10.14198/ALTERN.19435

López-Gómez, E. (2015). La tutoría en el EEES: Propuesta, Valoración de un Modelo Integral. Madrid, Spain: UNED.

López-Gómez, E. (2017). El Concepto y las finalidades de la Tutoría Universitaria: Una Consulta a Expertos. [the concept and purposes of university tutoring: a consultation with experts]. Rev. Esp. Orientac. Psicopedag. 28, 61–78. doi: 10.5944/reop.vol.28.num.2.2017.20119

López-Gómez, E., Levi-Orta, G., Medina Rivilla, A., and Ramos-Méndez, E. (2020). Dimensions of university tutoring: a psychometric study. J. Furth. High. Educ. 44, 609–627. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2019.1571174

Mackey, A., and Gass, S. M. (2015). Second language research: Methodology and design. New York: Routledge.

Martínez Clares, M. P., Pérez Cusó, F. J., and González Morga, N. (2019). ¿ Qué necesita el alumnado de la tutoría universitaria?: validación de un instrumento de medida a través de un análisis multivariante. Educacion XX1 22, 189–213. doi: 10.5944/educxx1.21302

Mayring, P. (2000). Qualitative content analysis. Available at: http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1089/2385

McChlery, S., and Wilkie, J. (2009). Pastoral support to undergraduates in higher education. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 8, 23–36. doi: 10.3794/ijme.81.220

McMillan, J. H., and Schumacher, S. (2005). Investigación educativa: una introducción conceptual. London: Pearson.

Ochnik, D., Rogowska, A. M., Kuśnierz, C., Jakubiak, M., Schütz, A., Held, M. J., et al. (2021). Mental health prevalence and predictors among university students in nine countries during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-national study. Sci. Rep. 11:18644. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-97697-3

Paltridge, B., and Phakiti, A. (2018). Research methods in applied linguistics: a practical resource. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Rädiker, S., and Kuckartz, U. (2021). Análisis de datos cualitativos con MAXQDA: Texto, audio, video. BoD -Books on Demand. MAXQDA Press.

Richards, C. E. (1988). Indicators and three types of educational monitoring systems: implications for design. Phi Delta Kappan 69, 495–499.

Rodríguez Ortiz, A. M. (2020). La narrativa como un método para la construcción y expresión del conocimiento en la investigación didáctica. Sophia 16, 183–195. doi: 10.18634/sophiaj.16v.2i.965

Ruiz-Mallén, I., and Heras, M. (2020). What sustainability? higher education institutions’ pathways to reach the agenda 2030 goals. Sostenibilidad 12:1290. doi: 10.3390/su12041290

Sallán, J. G., Condom, M. F., Ramos, C. G., and Vilamitjana, D. Q. (2004). La tutoría académica en el escenario europeo de la Educación Superior. RIFOP 49, 61–78.

Shava, G. N., Hleza, S., Tlou, F., Shonhiwa, F., and Mathonsi, E. (2021). Qualitative content analysis, utility, usability and processes in educational research. Int. J. Res. Innov. Soc. Sci. 5, 2454–6186.

Sutherland, K. A. (2009). Fomentar el rol de los tutores de pregrado en la comunidad docente universitaria. Mentor. Tutoring 17, 147–164. doi: 10.1080/13611260902860091

Thomas, L., and Hixenbaugh, P. (2007). Personal tutoring in higher education. Stoke-on-Trent, UK: Trentham books.

Vallejo, A. P., and Molero, D. (2022). Aspectos condicionantes de la tutoría universitaria. Un estudio comparado. Rev. Investig. Educ. 40, 33–49. doi: 10.6018/rie.373741

Vélez, M. E. M., Cedeño, L. A. D., and Vélez, N. J. J. (2019). Las tutorías universitarias como fortalecimiento al currículo pre-profesional de los estudiantes de la educación general básica. Didascalia 10, 119–134.

White, A., and LaBelle, S. (2019). A qualitative investigation of instructors’ perceived communicative roles in students’ mental health management. Commun. Educ. 68, 133–155. doi: 10.1080/03634523.2019.1571620

Wisker, G., Exley, K., Antoniou, M., and Ridley, P. (2013). Working one-to-one with students: Supervising, coaching, mentoring, and personal tutoring. New York: Routledge.

Zabalza, M. Á., and Beraza, M. Á. Z. (2003). Competencias docentes del profesorado universitario: calidad y desarrollo profesional. Madrid: Narcea.

Keywords: university tutoring, 2030 agenda, sustainable development, United Nations, quality education, higher education, sustainable, development goal fourth

Citation: Villarrubia Zúñiga MS, Ortiz-Jiménez M, González García P and Suárez-Campos L (2024) Evaluation of sustainability in university tutoring programs for educational leadership: a case study. Front. Educ. 9:1416666. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1416666

Received: 12 April 2024; Accepted: 01 July 2024;

Published: 19 July 2024.

Edited by:

Gisela Cebrián, University of Rovira i Virgili, SpainReviewed by:

Giovanna Barzano, Universities and Research, ItalyCopyright © 2024 Villarrubia Zúñiga, Ortiz-Jiménez, González García and Suárez-Campos. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: María Soledad Villarrubia Zúñiga, bWFyaXNvbHZpbGxhcnJ1YmlhQHVhLmVz

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.