- 1Department of English Language and Literature, Hunan Normal University, Changsha, China

- 2Department of English Language Education, University of Nahdlatul Ulama Purwokerto, Purwokerto, Indonesia

Racial inequalities persist in education, impacting various aspects, including language teaching. Traditional English language education has often favored standard English, inadvertently marginalizing non-native English speakers and users of diverse English varieties. This perpetuation of linguistic bias reinforces White hegemony within educational systems. This article contends that Global Englishes offers a promising approach to ameliorating racial inequalities in language education. It delves into the core principles of Global Englishes, scrutinizing linguistic, sociolinguistic, and sociocultural diversity and fluidity inherent in English use and its users in our globalized world. Furthermore, it explores how the Global Englishes Language Teaching (GELT) framework can promote equality, emphasizing best practices for implementing GELT to address racial inequalities. Global Englishes advocates for a more adaptable view of language, liberating non-native speakers from native-speaker norms. Global Englishes places learner agency at the forefront, nurturing linguistic creativity, advocating for curricula that acknowledge multilingualism as the norm, and affirming learners’ linguistic repertoires without reference to native norms. It also encourages a critical approach, analyzing the impact of prevailing standard language ideologies and White native-speakerism biases within learners’ contexts. The article concludes by offering insights into future directions to address racial inequalities in education, emphasizing the importance of incorporating multiracial perspectives into educational frameworks.

1 Introduction

The 2020 global COVID-19 pandemic, originating in Wuhan, China, exacerbated anti-Asian racism worldwide (Cheng et al., 2021). Levin (2021) reported a significant increase in anti-Asian hate crimes in the United States (US), with a staggering 146 percent increase observed across 26 major US jurisdictions in 2020 alone, accounting for 10% of the country’s population. This troubling trend persisted into 2021. Similarly, in Canada, anti-Asian racism surged in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic (Zhao et al., 2022). Levin (2021) documented a shocking 532 percent increase in anti-Asian hate crimes between 2009 and 2020 in four major Canadian cities. Moreover, a study by Huynh et al. (2023) revealed that 76% of Asian American adolescents and young adults now feel less safe compared to pre-pandemic times. Racism and white supremacy have deep historical roots in most Western societies (Qingqing, 2021). However, efforts have been made to raise awareness of anti-racism in multicultural contexts, such as initiatives like Khmer Girls in Action focusing on public health solutions (Lin, 2022), transcultural interaction (Matsuzawa, 2024), and addressing biases at individual and institutional levels (Louie-Poon et al., 2022).

While the focus of this paper is on language and racism within English language teaching (ELT), it is important to acknowledge the broader context of racism’s pervasive influence, including its exacerbation during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. This broader context sets the stage for understanding how racism intersects within language practices, particularly in educational settings. Linguistic racism, as defined by scholars like May (2023), reflects the intersection of language, race, and inequality. May defines linguistic racism as the confluence of language, race/ism, and inequality, often evident in racialized discourses on language status and multilingual language use directed toward non-dominant language speakers. Traditional ELT often privileges “standard” English while marginalizing “non-native” English speakers and speakers of English varieties (Rose and Galloway, 2019). The idealized form of English, closely associated with Whiteness, plays a significant role in preserving White hegemony (Hill, 1998). This idealization perpetuates inequality and discrimination within language teaching (Lomelí, 2023).

The ideal White English speaker is heavily emphasized in the English as a Foreign Language (EFL) curriculum, with research consistently showing biased representation in the textbook favoring white people over other racial groups (Bowen and Hopper, 2023). Visuals and images often perpetuate stereotypes, portraying white people as affluent, powerful, and successful, while minorities are depicted as impoverished and powerless (Yamada, 2014). These biased representations not only shape perceptions of English-speaking countries but also reinforce racial hierarchies within ELT.

In response to these issues, ELT scholars advocate for more inclusive and equitable language teaching practices recognizing linguistic, racial, and cultural diversity (Fang and Ren, 2018). The raciolinguistic perspective, proposed by Rosa and Flores (2017), addresses racial and linguistic inequality within ELT, paving the way for frameworks like Global Englishes Language Teaching (GELT) to confront and mitigate racial disparities in language education. GELT champions linguistic and cultural pluralism, fosters critical awareness, and advances anti-racist pedagogy, offering a promising avenue for promoting equity and social justice in language education.

This article aims to enrich existing scholarship by examining the complex relationship between language and racism and elucidating the core principles of GELT. We argue that GELT offers a compelling framework to confront and mitigate racial disparities in language education, championing linguistic and cultural pluralism, fostering critical awareness, and advancing anti-racist pedagogy.

2 Racism and English language users

Racism is a multifaceted phenomenon that permeates discourse, knowledge systems, and social behaviors, perpetuating unequal power dynamics among groups characterized by perceived racial differences (Kubota, 2022). The intersection between language and racism has been explored across various disciplines, including social psychology, linguistic anthropology, and sociolinguistics (May, 2023). Within these frameworks, language users often encounter racism through linguistic discrimination and subordination, which are embedded within broader racialized institutional and everyday discursive practices.

Despite the increasing racial diversity of English language users, dominant racial groups tend to overshadow perspectives expressed in curricula and textbooks. EFL teaching materials frequently depict subjects from the stereotyped culture and history of White middle-class English speakers, reinforcing the association between English and Whiteness (Widodo et al., 2022). Furthermore, academic research on English as a Second Language often relies heavily on concepts and information developed by well-known White Euro-American scholars, perpetuating institutional racism through citation practices (Kubota, 2021).

White superiority is entrenched as a discursively and materially established status, leading individuals of color to inadvertently perpetuate White supremacy by remaining silent. Failure to confront White supremacy perpetuates institutional and interpersonal racism, maintaining its invisibility. However, racial identification alone does not qualify individuals as anti-racist, as demonstrated in Lomelí’s (2023) study where a White teacher struggles to disrupt White supremacy through critical pedagogies. This underscores the need for pedagogical approaches that center anti-racist perspectives and engage students in critical inquiry to challenge racial hierarchies within educational settings.

3 Global Englishes language teaching

Traditional ELT has long served as the cornerstone of language education in many educational settings, offering structured methodologies and established frameworks for language acquisition. Central to traditional ELT is the focus on linguistic accuracy and proficiency, which has proven effective in developing learners’ language skills and proficiency levels (Klee et al., 1986; Barnard et al., 2002). Moreover, traditional ELT provides a sense of familiarity and consistency for both educators and learners, with standardized curricula and assessment practices guiding the teaching and learning process (Terrell and Brown, 1981).

However, despite its efficacy in certain areas, traditional ELT has been criticized for its limited scope and Eurocentric biases. One of the key shortcomings of traditional ELT is its tendency to prioritize “standard” English and native-speaker norms, thereby marginalizing non-native English speakers and perpetuating linguistic and cultural hierarchies (Holliday, 2006). Additionally, traditional ELT often overlooks the linguistic diversity of English use worldwide, failing to adequately prepare learners for communication in global contexts (Galloway, 2013).

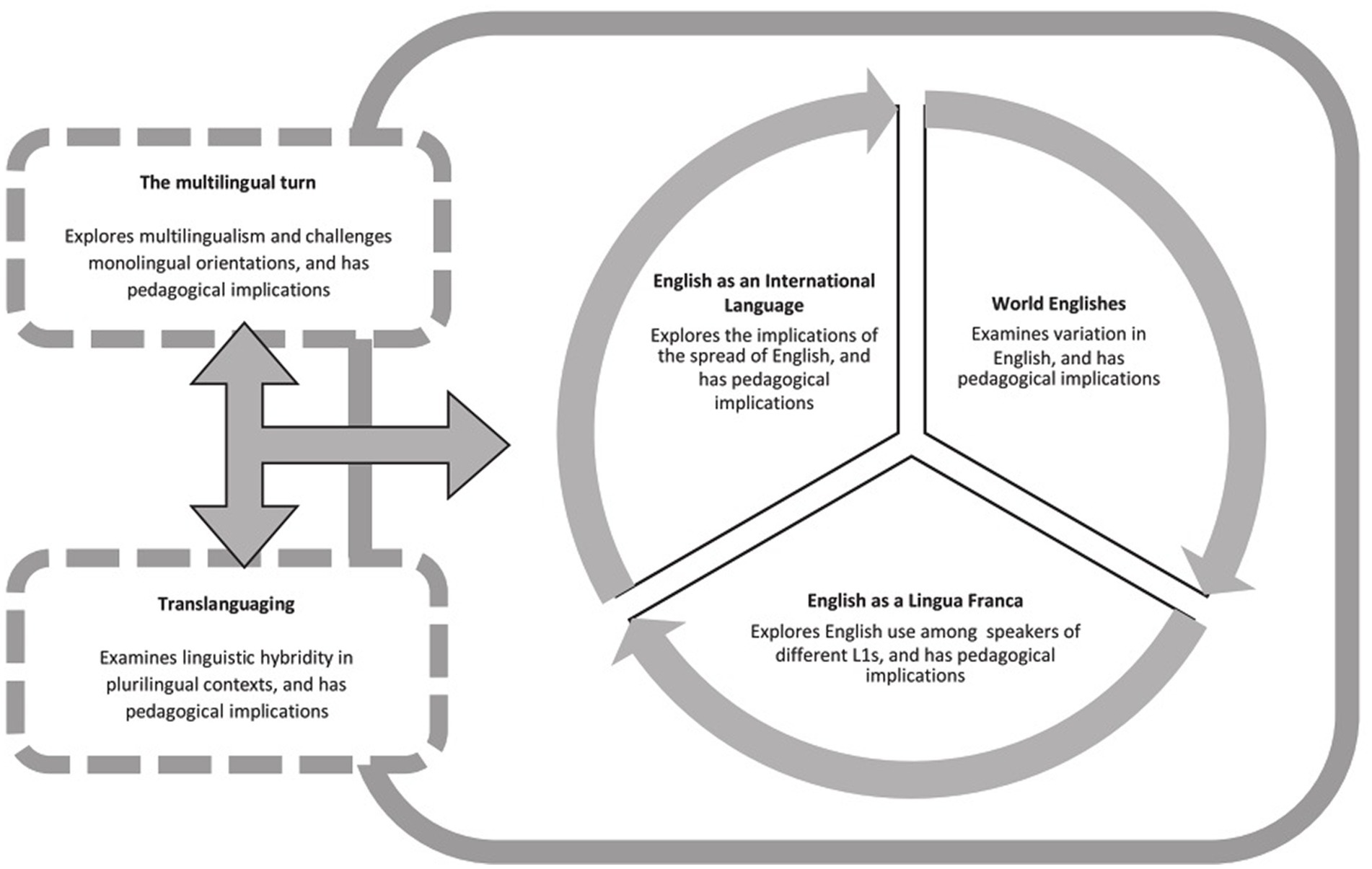

In contrast, Global Englishes offers a more inclusive and culturally responsive approach to English language education. Global Englishes recognizes the linguistic and cultural diversity of English users and emphasizes the importance of communicative competence in intercultural contexts (Galloway and Rose, 2015). By incorporating principles of World Englishes (WE), English as a Lingua Franca (ELF), English as an international language (EIL), and translanguaging, Global Englishes promotes language variation and fluidity, empowering learners to engage meaningfully with diverse linguistic communities.

Furthermore, discussions surrounding racism in ELT emphasize the importance of anti-racist practices in fostering understanding among individuals from diverse linguistic, cultural, and racial backgrounds. Initiating anti-racist education at the elementary school level is crucial (Daly, 2023). While openly addressing racism may be discouraged in society, anti-racist educational initiatives should transcend mere rhetoric and challenge power dynamics, privilege, and ideologies of dominance and subordination (Schieble et al., 2023). In this context, Global Englishes emerges as a promising anti-racist pedagogy, offering an inclusive framework that examines the linguistic, sociolinguistic, and sociocultural diversity and fluidity of English use and its users in a globalized world (Rose and Galloway, 2019, p. 4).

In summary, while traditional ELT has its merits, particularly in terms of language proficiency development and instructional consistency, GELT offers a more progressive and equitable approach to English language education. By embracing linguistic diversity and promoting intercultural communicative competence, GELT provides learners with the skills and knowledge needed to navigate the complexities of communication in a globalized world (Rose et al., 2021). Collaborative efforts across these fields are unified under the umbrella term of Global Englishes, as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Global Englishes: an inclusive paradigm. Source: Rose and Galloway (2019, p. 12).

4 Discussion

4.1 Global Englishes language teaching framework for anti-racist education

ELT is increasingly being constructed under Global Englishes principles, aimed at equipping students with intercultural communicative competence, pluricentricity, and negotiation skills in diverse contexts. The GELT framework, pioneered by Galloway (2013) advocates for: (1) integrating exposure to WE and ELF in language curricula; (2) promoting respect for multilingualism in ELT; (3) raising awareness of Global Englishes; (4) incorporating ELF strategies into language curricula; (5) emphasizing respect for diverse cultures and identities in ELT; and (6) reforming English teacher hiring practices in the ELT industry (Galloway and Rose, 2015, p. 430).

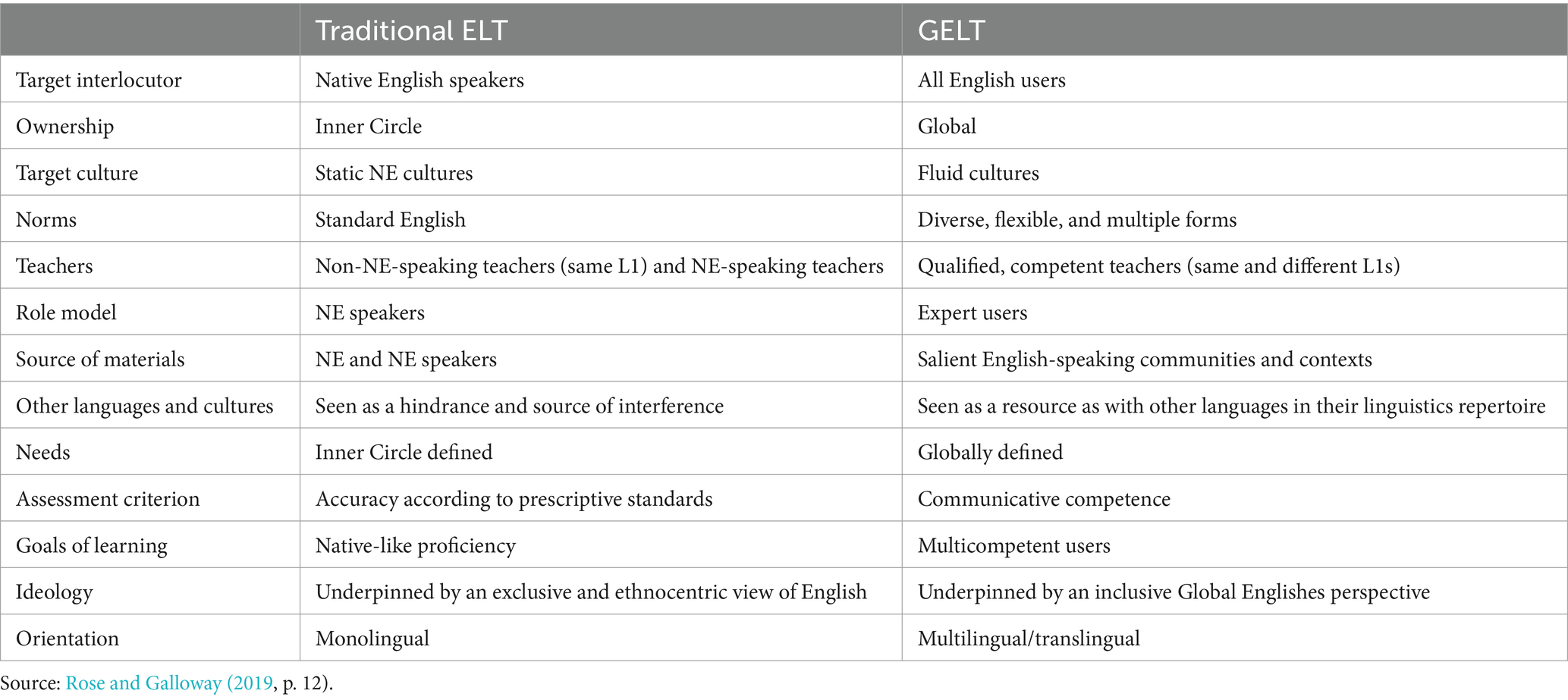

Drawing inspiration from previous conceptualizations such as Jenkins (2006) EFL vs. ELF framework, as well as the work of Canagarajah (2004) and Seidlhofer (2004), the framework aimed to provide a comprehensive and user-friendly approach to addressing the evolving landscape of English language education. Over time, the framework has undergone refinements to incorporate new concepts and proposals, with Rose and Galloway (2019) making minor adjustments to better reflect current research and perspectives (Table 1).

In traditional ELT practices, preference is often given to native English speakers as the target interlocutor. Research by Takahashi (2013) on Japanese female travelers in Australia highlighted the association between learning English and romanticizing Western identity, mobility, and desires for Western male partners. This underscores the interconnectedness of learner (racial) identities and linguistic aspirations, emphasizing the need for a deeper understanding of these connections in language instruction (Von Esch et al., 2020). Similarly, Stanley (2013) conducted ethnographic research in China, revealing how White native English speakers’ symbolic position was perceived in contrast to the patriotic identification of Chineseness among learners. White instructors are often expected to perform their Whiteness in such contexts. However, in alignment with Global Englishes principles, contemporary English learners must engage with a global community of diverse language users, cultures, and races (Jeong et al., 2021). Therefore, instructional methods should equip learners with the skills and awareness necessary for effective communication in diverse contexts (Rose and Galloway, 2019). Digital discourse, characterized by interactive written communication in online spaces, has emerged as a potent tool for raising awareness among English language learners about the complexities of language use in diverse settings (Higgs, 2020; Schaefer, 2022).

The native speaker is given a disproportionate amount of importance, which can be traced back to an underlying concept that the Inner Circle possesses ownership of the English language. This is even though significantly more people speak English outside of the Inner Circle than inside, a fact that is only likely to grow more apparent in the years to come. This further emphasizes the need to encourage a perception in the classroom that English belongs to a global community, rather than its traditional origins as the language of the Whiteness, or more broadly of those living in nations descendant from the former British Empire. Within a GELT perspective, the owners of English are seen as being as fluid as the language they speak, moving beyond outdated notions that geographic borders and nation-based states “contain” language and speakers (Rose and Galloway, 2019). Similarly, digital multimodal composition can bolster the ownership of the English language beyond the inner circle countries (Higgs and Kim, 2022).

Consideration of the target culture in which the language will be used is paramount, particularly in light of evolving representations of ownership and target interlocutors. Traditional ELT often reinforces fixed racial and cultural stereotypes (Yamada, 2014). However, the GELT framework encourages learners to recognize that cultures are dynamic and continually evolving with each language interaction. This awareness is especially crucial in lingua franca environments, where speakers bring diverse expectations and experiences to the speech community. McBride et al. (2023) conducted a study using humanizing pedagogy, utilizing Google Maps to expose students to various cultures of English users worldwide. This approach highlights the fluid and complex interaction between language and culture in lingua franca encounters, emphasizing the importance of intercultural and racial awareness and the necessity to move away from essentialist conceptualizations.

The norms underlying language teaching are deeply entrenched and resistant to change, rooted in standard language ideology that posits the existence of a fixed, correct version of the language. Standard English is often linked with colonial power and Whiteness, serving to maintain White hegemony. GELT aligns with criticisms of static language views (Widdowson, 2012), advocating for exposure to diverse forms of the language throughout students’ education. This diversity can be achieved through exposure to various English varieties (Galloway and Numajiri, 2020) and awareness-raising initiatives (Galloway, 2013; Rose and Galloway, 2017). Educational technologies also play a role in accommodating this fluidity and diversity. Tan and Md Yunus (2023) introduced a platform allowing English users to utilize online networks to foster social exchanges and raise awareness of the global ownership of English.

In traditional ELT, the idealized image of an English speaker often corresponds with Whiteness (Yamada, 2014), leading to racism through the association of “native English speaker” with “White.” This phenomenon, termed “native-speakerism” by Holliday (2006), results in disparate treatment of English users based on their perceived native-speaker status, with native speakers typically receiving preferential treatment over non-native speakers, thereby perpetuating racial inequality. Addressing this issue, Kim and Higgs (2023) utilized technology to bridge racial and cultural gaps between educators and learners, employing digital platforms to promote anti-racist education. Ultimately, the GELT framework emphasizes the importance of positioning qualified, expert users as ideal role models for learners, reflecting worldwide ownership of the language and fostering stronger connections between learners and the language.

Despite the prevalence of non-native English speakers as EFL instructors globally (Sung, 2011), research by Rivers and Ross (2013) indicates a preference among Japanese students for White native-speaking language teachers. Ruecker and Ives (2015) examined 59 websites advertising language schools in several East Asian countries, revealing entrenched biases portraying English teachers as predominantly young, White native speakers from select nations with majority White populations. Additionally, Jenks’ (2018) research in South Korea shed light on the intricate practices perpetuating a culture of “White normativity” within the industry, particularly evident in teacher identity, which sustains racial discrimination across local classroom methodologies and national hiring protocols. Consequently, the ELT profession stands out as one where discrimination against the majority is rife (Rose and Galloway, 2019).

Addressing this issue necessitates the positioning of competent teachers as the epitome of ideal English instructors, regardless of their native English speaker status. This is intricately tied to the representation of authentic role models in the English language teaching domain. While native speakers are often perceived as authoritative language practitioners, students frequently find them to be inadequate role models as they embody an ideal that seems unattainable for language acquisition (Rose and Galloway, 2019). This assertion resonates with Schieble et al.’s (2023) findings, wherein students critically examine the instructional methodologies and native-speaker ideologies. The study underscores the importance of embracing translanguaging ideology to foster critical discourse. Additionally, Emilia and Hamied’s (2022) ethnographic study revealed that translanguaging practices benefited the learners’ cognitive, social, and psychological aspects which tackled linguistic racism in the Indonesian context.

GELT advocates for a broader incorporation of global English language sources in instructional materials, reflecting the diverse uses of English worldwide. It emphasizes the necessity of accurately portraying students’ future English language needs in textbooks through a comprehensive needs analysis to ensure that classroom materials align with long-term language requirements. Moreover, there is a pressing need to scrutinize the depiction of speakers of languages other than English in curriculum images and materials. Additionally, incorporating familiar subjects like sporting events and popular movies, along with diverse instructional resources such as readings, activities, and images from textbooks, is essential. Kubota (2021) also suggests expanding the scope of materials and topics to encompass current newsworthy events such as Black Lives Matter, the COVID-19 pandemic, and immigration laws.

In the realm of language instruction, traditional ELT often enforces an English-only policy alongside students’ scrutiny of each other’s language usage. McKinney’s (2016) ethnographic research in four South African schools unveils how standard English ideology, English-only directives, and White hegemony intertwine, forming what she terms “anglonormativity.” McKinney illustrates how practices like teacher and student discussions regarding pronunciation standards and acceptable English vocabulary usage, alongside the stigmatization of Black English varieties, marginalize students from non-dominant backgrounds by portraying them as deficient in certain language skills. Contrary to these norms, GELT challenges regulations mandating exclusive English usage. It regards learners’ first language or mother tongue not as an impediment but as a valuable resource for learning. Similarly, GELT recognizes the importance of incorporating learners’ native culture into the instructional framework.

Traditional ELT, deeply entrenched in standard language ideology typically associated with White native speakers, perpetuates inequalities within language learning. An example of this inequity is evident when a native speaker’s deviation from standard English, such as saying “two coffees” instead of “two cups of coffee,” is often hailed as innovation (Galloway and Rose, 2014), while the same deviation from a non-native speaker is frequently labeled as an error. Contrary to this approach, the underlying ideology of GELT, as argued by Rose and Galloway (2019), aligns with the inclusive paradigm of Global Englishes, which embraces the diverse forms of English used worldwide. They posit that Global Englishes has the potential to disrupt existing paradigms within English language teaching.

English has evolved into a global lingua franca, transcending its origins as the language of a minority of native speakers to become a globally owned language. It serves as a bridge among individuals from diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds, many of whom are expanding their multilingual repertoire. Its usage spans various contexts and purposes, often blending with other languages to facilitate successful communication. This dynamic nature has led to its characterization as a contact language, a lingua franca, and a language in flux. The GELT framework embraces the linguistic, sociolinguistic, and sociocultural diversity and fluidity of English use, examining its implications for various societal aspects, including TESOL curricula and teaching practices, toward a more equitable language education.

5 Conclusion

The extensive literature exploring standard language ideology, the concept of the “ideal” native speaker, and the pervasive influence of White hegemony in English underscores the deep-rooted presence of White supremacy within contemporary epistemology, educational subjects, and instructional methodologies. GELT emerges as a pivotal response to these entrenched inequalities, offering the potential to redress racial disparities in education. By embracing a critical pedagogy approach and recognizing the rich diversity of Englishes worldwide, GELT stands poised to foster linguistic and cultural inclusivity within the classroom. The literature review underscores how the traditional native-speaker paradigm in language instruction perpetuates racial biases and marginalizes non-native speakers. Thus, it becomes imperative to acknowledge and celebrate the linguistic pluralism inherent in English and transition toward a more inclusive and equitable language teaching approach. While challenges persist in implementing GELT within educational settings, this paper contends that GELT serves as a valuable framework for confronting racial inequalities in language education and nurturing a socially just learning environment. Consequently, the adoption and implementation of GELT, coupled with a commitment to critical anti-racism, necessitate ongoing learning and practice by educators and teacher educators characterized by openness, resilience, and unwavering vigilance.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Author contributions

DY: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AB: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the Hunan Provincial Key Laboratory “Artificial Intelligence and Precise International Communication.”

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Barnard, R., Richards, J. C., and Rodgers, T. S. (2002). Approaches and methods in language teaching. TESOL Q. 36:636. doi: 10.2307/3588247

Bowen, N. E. J. A., and Hopper, D. (2023). The representation of race in English language learning textbooks: inclusivity and equality in images. TESOL Q. 57, 1013–1040. doi: 10.1002/tesq.3169

Canagarajah, A. S. (2004) Reclaiming the local in language policy and practice. New York: Routledge.

Cheng, H. L., Kim, H. Y., Reynolds (Taewon Choi), J. D., Tsong, Y., and Joel Wong, Y. (2021). COVID-19 anti-Asian racism: a tripartite model of collective psychosocial resilience. Am. Psychol. 76, 627–642. doi: 10.1037/amp0000808

Daly, A. (2023). Race talk tensions: practicing racial literacy in a fourth-grade classroom. Engl. Teach. 22, 61–78. doi: 10.1108/ETPC-02-2022-0028

Emilia, E., and Hamied, F. A. (2022). Translanguaging practices in a tertiary EFL context in Indonesia. TEFLIN J. 33, 47–74. doi: 10.15639/teflinjournal.v33i1/47-74

Fang, F., and Ren, W. (2018). Developing students’ awareness of Global Englishes. ELT J. 72, 384–394. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccy012

Galloway, N. (2013). Global Englishes and English language teaching (ELT) - bridging the gap between theory and practice in a Japanese context. System 41, 786–803. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2013.07.019

Galloway, N., and Numajiri, T. (2020). Global Englishes language teaching: bottom-up curriculum implementation. TESOL Q. 54, 118–145. doi: 10.1002/tesq.547

Galloway, N., and Rose, H. (2014). Using listening journals to raise awareness of Global Englishes in ELT. ELT J. 68, 386–396. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccu021

Higgs, J. (2020). Digital discourse in classrooms: language arts teachers’ reported perceptions and implementation. Res. Teach. Engl. 55, 32–55. doi: 10.58680/rte202030900

Higgs, J. M., and Kim, G. M. H. (2022). Interpreting old texts with new tools: digital multimodal composition for a high school reading assignment. English Teach. 21, 128–142. doi: 10.1108/ETPC-07-2020-0079

Hill, J. H. (1998). Language, race, and white public space. Am. Anthropol. 100, 680–689. doi: 10.1525/aa.1998.100.3.680

Huynh, J., Chien, J., Nguyen, A. T., Honda, D., Cho, E. E. Y., Xiong, M., et al. (2023). The mental health of Asian American adolescents and young adults amid the rise of anti-Asian racism. Front. Public Health 10:958517. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.958517

Jenkins, J. (2006). Points of view and blind spots: ELF and SLA. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 16, 137–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-4192.2006.00111.x

Jenks, C. J. (2018). Race and ethnicity in English language teaching. Applied Linguistics. 42, 192–195. doi: 10.1093/applin/amy043

Jeong, H., Elgemark, A., and Thorén, B. (2021). Swedish youths as listeners of Global Englishes speakers with diverse accents: listener intelligibility, listener comprehensibility, Accentedness perception, and accentedness acceptance. Front. Educ. 6:651908. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.651908

Kim, G. M. H., and Higgs, J. (2023). Exploring equity issues with technology in secondary literacy education. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 32, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/1475939X.2022.2150288

Klee, C. A., Richards, J. C., and Rodgers, T. S. (1986). Approaches and methods in language teaching. Mod. Lang. J. 70:420. doi: 10.2307/326829

Kubota, R. (2021). Critical antiracist pedagogy in ELT. ELT J. 75, 237–246. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccab015

Kubota, R. (2022). Racialised teaching of English in Asian contexts: introduction. Lang. Cult. Curr. 36, 1–6. doi: 10.1080/07908318.2022.2048000

Levin, B. (2021). Report to the nation: anti-Asian prejudice and hate crime. Available at: dataspace.princeton.edu.

Lin, M. (2022). Khmer girls in action and healing justice: expanding understandings of anti-Asian racism and public health solutions. Front. Public Health 10:956308. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.956308

Lomelí, K. (2023). The work of growing young people con Cariño: a reconstructive lens on one white teacher’s anti-racist approach to teaching immigrant-origin Latinx students. English Teach. 22, 45–60. doi: 10.1108/ETPC-03-2022-0040

Louie-Poon, S., Idrees, S., Plesuk, T., Hilario, C., and Scott, S. D. (2022). Racism and the mental health of east Asian diasporas in North America: a scoping review. J. Ment. Health 31, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2022.2069715

Matsuzawa, S. (2024). Confronting Japan’s anti-Asian racism: the transformation of the Beheiren Movement’s identity during the Vietnam war. Sociol. Inq. 94, 472–490. doi: 10.1111/soin.12594

May, S. (2023). Linguistic racism: origins and implications. Ethnicities 23, 651–661. doi: 10.1177/14687968231193072

McBride, C., Smith, A., and Kalir, J. H. (2023). Tinkering toward teacher learning: a case for critical playful literacies in teacher education. English Teach. 22, 221–233. doi: 10.1108/ETPC-08-2022-0114

McKinney, C. (2016) Language and power in post-colonial schooling: ideologies in practice. New York: Routledge.

Qingqing, L. (2021) Western racism against China reflects white supremacy. Available at: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202103/1217093.shtml.

Rivers, D. J., and Ross, A. S. (2013). Idealized English teachers: the implicit influence of race in Japan. J. Lang. Ident. Educ. 12, 321–339. doi: 10.1080/15348458.2013.835575

Rosa, J., and Flores, N. (2017). Unsettling race and language: toward a raciolinguistic perspective. Lang. Soc. 46, 621–647. doi: 10.1017/S0047404517000562

Rose, H., and Galloway, N. (2017). Debating standard language ideology in the classroom: using the “speak good English movement” to raise awareness of Global Englishes. RELC J. 48, 294–301. doi: 10.1177/0033688216684281

Rose, H., and Galloway, N. (2019). Global Englishes for language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rose, H., McKinley, J., and Galloway, N. (2021). Global Englishes and language teaching: a review of pedagogical research. Lang. Teach. 54, 157–189. doi: 10.1017/S0261444820000518

Ruecker, T., and Ives, L. (2015). White native English speakers needed: the rhetorical construction of privilege in online teacher recruitment spaces. TESOL Q. 49, 733–756. doi: 10.1002/tesq.195

Schaefer, S. J. (2022). Global Englishes and the semiotics of German radio—encouraging the Listener’s visual imagination through Translingual and Transmodal practices. Front. Commun. 7:780195. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.780195

Schieble, M., Vetter, A., and Monét Martin, K. (2023). Shifting language ideologies and pedagogies to be anti-racist: a reconstructive discourse analysis of one ELA teacher inquiry group. English Teach. 22, 96–111. doi: 10.1108/ETPC-03-2022-0033

Seidlhofer, B. (2004). Research perspectives on teaching English as a lingua franca. Annu. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 24, 209–239. doi: 10.1017/s0267190504000145

Stanley, P. (2013) A critical ethnography of ‘westerners’ teaching English in China: shanghaied in Shanghai. ELT J. 67, 508–510. doi: 10.1093/elt/cct047

Sung, C. C. M. (2011). Race and native speakers in ELT: parents’ perspectives in Hong Kong. English Today 27, 25–29. doi: 10.1017/s0266078411000344

Takahashi, K. (2013) Language learning, gender and desire: Japanese women on the move. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Tan, S. Y., and Md Yunus, M. (2023). Sustaining English language education with social networking sites (SNSs): a systematic review. Sustainability 15:5710. doi: 10.3390/su15075710

Terrell, T. D., and Brown, H. D. (1981). Principles of language learning and teaching. Language 57:781. doi: 10.2307/414380

Von Esch, K. S., Motha, S., and Kubota, R. (2020). Race and language teaching. Lang. Teach. 53, 391–421. doi: 10.1017/S0261444820000269

Widdowson, H. G. (2012). ELF and the inconvenience of established concepts. JELF 1, 5–26. doi: 10.1515/jelf-2012-0002

Widodo, H. P., Fang, F., and Elyas, T. (2022). Designing English language materials from the perspective of Global Englishes. Asian Engl. 24, 186–198. doi: 10.1080/13488678.2022.2062540

Yamada, M. (2014) The role of English teaching in modern Japan: diversity and multiculturalism through English language education in a globalized era. London: Routledge.

Keywords: Global Englishes, language teaching, anti-racist education, racial inequalities, linguistic racism, linguistic diversity, GELT framework, standard language ideologies

Citation: Yunhua D and Budiman A (2024) Embracing linguistic diversity: Global Englishes language teaching for anti-racist education. Front. Educ. 9:1413778. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1413778

Edited by:

Denchai Prabjandee, Burapha University, ThailandReviewed by:

Pariwat Imsa-ard, Thammasat University, ThailandKrich Rajprasit, Srinakharinwirot University, Thailand

Takuya Numajiri, University of Fukui, Japan

Copyright © 2024 Yunhua and Budiman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Asep Budiman, YnVkaW1hbkBodW5udS5lZHUuY24=

Deng Yunhua1

Deng Yunhua1 Asep Budiman

Asep Budiman