- 1Department of English, Mepco Schlenk Engineering College, Sivakasi, Tamil Nadu, India

- 2Department of Interdisciplinary Studies, Akenten Appiah-Menka University of Skills Training and Entrepreneurial Development, Kumasi, Ghana

Introduction: This study aims to focus on government school students, who struggle hard to express themselves in English.

Methods: A two-group simple randomized design was used for this study, and an experimental study was carried out among 60 rural high school students. ‘Captivating activities’ (listening, speaking, reading, and writing) have been used to find the effect on learners’ communication skills. Furthermore, a pre-test and a post-test were conducted between groups, and their scores were analyzed. A paired sample t-test was carried out to identify the difference between controlled and experimental groups.

Results: The results showed that there was a significant average difference observed between the pre-test and post-test scores (t28 = 8.327, p = 0.000, p < 0.01) of the experimental group.

Discussion: As an outcome of the tested strategy, it was understood that an English-speaking environment can help students improve their language skills to some extent. It was concluded that the captivating activities (listening, speaking, reading, and writing) are effective for augmenting learners’ communication skills.

Introduction

The evolution of education has a humble beginning. Initially, parents relied on education as a form of childcare when they moved from farm life to industrial work environments. Then, the focus of education shifted toward teaching practical skills and abilities that would serve them in later life. The motto of education has evolved in various ways: it began with Education 1.0, which mainly focused on taking care of working-class kids; then, it progressed to Education 2.0, which provided a platform for developing students’ capabilities; and finally has reached Education 3.0, where teachers and resources serve as facilitators of learning. The future plan is to inspire children to learn and apply their education in ways that allow them to fully utilize their talents. The history of education originated in the 17th century. Like other professions such as farming and hunting, teaching was also considered a profession. Those who showed interest in education and teaching were recruited by local review boards comprising the hierarchies in the locality. Teaching was a trump card to join law or clergy. Horace Mann brought a reformation in education in the 19th century. Public schools came into existence, and teachers were certified depending on their specialization. Teachers in the past were trained before they were identified as teachers in society. Different schools were launched in the universities to train teachers.

The education of teachers went hand in hand with the refinement of learning pedagogy. Learning tools and techniques have changed significantly because of the digital revolution. Hands-on learning, flipped classrooms, microlearning, and diversified learning provide varied opportunities to students to excel in learning. Students in rural schools have inhibitions to communicate in English within the classroom, and this reluctance continues when they appear for placement interviews. This lack of communication does not mean that the students are slow bloomers; these students excel in their subjects but struggle to effectively convey their knowledge during interviews. They feel inferior when compared to students from matriculation, Indian Certificate of Secondary Education (ICSE), and Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) backgrounds. It is generally assumed that only a few can afford these educational boards mentioned. To be specific, the students in the urban areas have smart classes and teachers with prolific experience in technology-integrated teaching. Lack of infrastructure also remains one of the constraints for the students. Apart from these, they hardly come across an English-speaking environment.

India has implemented several educational policies and initiatives to enhance English language skills among students, particularly in rural areas. Due to the important role of English language communicative skills in India, Kasana and Saxena (2024) indicated that the Indian government has formulated and implemented several policies aimed at boosting the development of communicative skills. These include the following:

Policy for National Education (NEP) 2023: With extensive reforms, the NEP 2023 seeks to elevate India’s education system to a position of worldwide prominence. Its main goal is to foster an atmosphere of education that is inclusive, equal, and of the highest caliber at every level, from early childhood to higher education. Important elements consist of the following:

1. Multilingual approach: To support cognitive growth and cultural preservation, emphasis should be placed on education in mother tongues or regional languages up to a particular level.

2. Flexible curriculum: Giving students the freedom to choose their own educational routes in accordance with their interests and career goals.

3. Digital literacy: Using state-of-the-art technology to give everyone access to online learning resources and democratize education.

4. Industry integration: Improving postsecondary education by integrating many disciplines and bringing it into line with business needs.

Chavan (2024) also mentioned the English Language and General Awareness (ELGA) as additional policies. The ELGA is a competency-based program designed to improve kids’ English language skills. It covers the following five essential areas of English language learning: grammar, phonics, writing and speaking expression, whole words, and reading and listening comprehension.

The Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA) and Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan (RMSA) policies were mentioned by Swargiary and Roy (2014). To guarantee that no kid is left behind in terms of education, these programs aimed to close disparities in access and quality.

These efforts collectively contribute to improving English language skills among students, fostering a more inclusive and globally competitive education system in India. Even though policies have been rolled out for their implementation, learners still face challenges with communicative skills, especially those from rural areas. It is therefore important to examine what could be done to improve their communication skills. This study sought to examine whether using captivating activities in reading, writing, listening, and speaking could improve learners’ communication skills.

Rationale for the study

At present, Tamil Nadu (one of the states in India) state government has provided a privilege to government school students that the meritorious students (those who secured 75% marks) can join the college they prefer and their education expenses will be taken care of by the government of Tamil Nadu. Though the students join the college they like, they do not have enough confidence to communicate with their peers as well as with the professors. To bridge this gap, it is planned to conduct training for 8th-grade students because these students once trained can take away the key components of communication in English. So these trainees were chosen with the hope that they did not lose anything taught in the class to cover the syllabus. An attempt is made to implement the training among these students to have a track record in their language proficiency and enable them to feel at ease when they move toward their higher studies and further they gain that confidence as they step out of the campus.

Communicative skills remain an essential aspect of students’ learning. This is because communication is crucial in everyday life. The ability to communicate well requires that one articulates his/her thoughts clearly. However, many more students in India have great difficulty in communicative skills especially in rural areas. According to Chermakani et al. (2023), learning English has been called a nightmare for many people, particularly in nations such as India where it is not the national language. The reason for this is because most students have trouble developing their communicative competence skills in English, which is their second language (SL). The truth is that to interact with others and communicate effectively, a person must have communicative competence. Learners in remote areas are less likely to be exposed to English as a First Additional Language (EFAL), according to Moresebetoa (2016). They need more fundamental instruction in writing and reading. They might use this to connect with their coworkers who are quiet and reveal the strategies in developing communicative skills.

As a result of the role of communicative skills in the learning of students, researchers have devoted a lot of time to investigating strategies in improving learners’ communicative skills in reading, speaking, and writing. Merzoug and Benyagoub (2021), for example, used web-based technologies to increase students’ communicative competence. Computer-based strategies were employed. In addition, Imane (2016) investigated how well speaking communicative exercises work to enhance speaking abilities. His research was restricted to speaking abilities only. Budiman et al. (2023) looked at the best ways to help these students acquire the reading skills required for success in school in a different study. Nget et al. (2020) employed task-based instruction (TBI) to examine the impact of TBI on the English-speaking abilities of ninth graders. The goal of Silva-Valencia et al. (2021) and Jeisica (2018) was to investigate the effects of communicative language teaching methods on high school students’ speaking skill development.

In addition, Alshahrani (2019) sought to improve vocabulary abilities through the use of memorization techniques, reading tactics, and tale book reading strategies. Writing techniques and the Cover, Copy, Compare (CCC) method improved spelling abilities. To enhance students’ oral skills, Toro et al. (2018) investigated how the communicative language teaching approach was applied in English classrooms as well as the tools and tactics that teachers employed. The study of Toro et al. (2018) like many other studies focused on only one aspect of communication.

It is revealed that each of the strategies used enhanced the particular communicative skills that the study focused on. The issue is that all the students focused on only one aspect of communicative skills. This study thus sought to include all four aspects of communicative skills in a single study. This is because all the aspects of communicative skills need to be studied for a better understanding and description of learners’ communicative skills development. The captivating activities used in this study included reading, writing, speaking, and listening skills.

Objective of the study

Communication acts as a trump card for an individual to be triumphant in his career. The motto of this investigation is to upskill the proficiency of rural students in Tamil Nadu. This method enabled the students, who were impoverished and did not face English-speaking ambience, to stay assertive in their communication. These captivating activities that were provided helped them to alleviate the obstacles in learning the second language, English. For that, a study was carried out among high school students of the State Board stream (8th standard). These students when they move to their higher classes apply the knowledge they acquired and can enhance their communicative skills in the job market. Promotion of communicative skills will hone their academic achievements.

Research hypotheses

H01: There is no statistically significant difference in communication skills between learners who receive the captivating activities and learners who did not.

Literature review

According to Pearson (2019), higher education altered all facets from the learners and teaching models to the challenges and educators alike. Education becomes accessible to the downtrodden to an extent to help their family members financially. Certain challenges, especially financial challenges, pose a serious threat to the government to match their perspective with private educational sectors. Teachers, as facilitators, need to equip themselves with tools and techniques that address the needs of today’s students. The quality of education has a direct involvement in the development of society and the impact on technology. Singh (2011) said that India needed higher educated people who were skilled to drive our economy forward. Skilled students could survive anywhere across the globe and bring laurels to our nation. Joseph and Windchief (2015) designed a model called Nahongvita—a model that would intersect the roles of home environments, academic environments, community, and history to empower American Indian students from rural communities to succeed in higher education. It empowered students to utilize their own experience to define “home” and “home communities.”

Goldman (2019) pinpointed the barriers that were faced by rural students in learning. On-campus resources, family support, finding a place to belong in college, and self-efficacy proved to be important access and persistence factors for students. These challenges affect their learning and, by extension, affect their English language learning. For instance, lack of access to English language resources affects the learning and development of their English language proficiency. In government schools, ICT tools are not used effectively; furthermore, regional dialect influenced the learners more and acted as barriers for them. In addition, the classroom setting could not cope with English language practice opportunities and eventually students have affective filter variables (low motivation, high anxiety, and low self-esteem) while using the L2 language. Resta (2002) highlighted the UNESCO report which significances the ICT-enabled teaching and learning. Education demanded more knowledge from teachers in terms of technology. It made learning more attractive than our conservative education system. Li (2023) found out that rural resilience was pivotal in maintaining rural stability and people’s living standards in the face of risks and unexpected challenges. He had suggested ways to improve rural resilience. Yang et al. (2021) stressed the significance of rural revitalization to promote its growth. Local government was also expected to contribute its role to uplift the downtrodden for the development of the nation.

Caleb et al. (2019) said that the present education system transformation needs to set itself on par with education systems abroad. Recent government policies of National Skill development such as Start-up India and Skill India were the engines of economic growth and social development of any country. The transition would equip the standard of the workers along with their living standards. He also says that India needed a flexible education and training system that would provide a foundation for learning secondary and tertiary education to develop the required competencies. Aiyar et al. (2021) opined that the structural transformation of rural India is influenced by urban culture. Flair for urban posh life in the midst of technology lured the attention of rural folks.

Nandy et al. (2021) took a survey to analyze how India’s Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) was the largest public works-based rural livelihood program in the world. One of the important policy objectives of the Scheme was to curb rural out-migration by guaranteeing demand-driven employment opportunities for 100 days in a year in rural areas. Based on the findings, the study drew several policy implications and discussed key policy imperatives toward expanding the scale and scope of the public works scheme. Educating the rural folks was the key factor for the upliftment of the rural community. Das and Biswas (2021) identified the high- and low-performing states in India and analyzed their performance over the years, especially after the introduction of the Right to Education (RTE) Act, 2009. It also discussed the factors that had positive or negative impacts on the learning outcomes. The analysis unveiled retrogression of the quality parameter over the years. The policies had emphasized on steady expansion in enrollment without paying the required attention to the standards of learning. The compromise on the quality of primary education diminished the splendor of India’s achievement in education.

The Public Report on Basic Education (PROBE) suggests that ‘quality education’ requires adequate facilities, responsible teachers, an active classroom, and an engaging curriculum (Tiwari, 2019). These were simply not met at present. She also nailed that India’s economic expansion was supposed to create opportunities for millions to rise out of poverty, acquire education, and get good jobs, but after India liberalized its economy in 1991 after decades of socialism, it failed to reform its heavily regulated education system. Patel (2018) stated that technology is influential in various aspects in the field of education. E-learning is an effective tool for the development of the educational sector in India. E-learning is a learning utilizing electronic technologies to access educational curriculum outside of a traditional classroom. In most cases, it refers to a course, program, or degree delivered completely online. He stressed the concept of e-learning and analyzed its types for effective learning. Nookathoti (2022) highlighted that education has the innate responsibility of escorting societies forward. It has the ability to transform society across space and time. It also enables an individual to communicate effectively. Hence, the field of education and dissemination of knowledge is very much a pivotal entity in the evolution of human civilization. No country in the globe over centuries could afford to flourish on the paths of growth and development while ignoring the crucial role of education. In countries such as India, there has been a perpetual struggle over the decades to overcome the perils of colonization and social stigmatization reflective in terms of poverty, unemployment, and illiteracy. To overcome these bottlenecks, ‘knowledge dissemination’ must spearhead the change. Apart from other funding inadequacies and infrastructural lacunae, the education sector in India had also been grappling with certain innate contradicting and counterproductive structures.

Choithani et al. (2021) drew on extensive primary data collected at two sites in West Bengal and Bihar, along with a comprehensive analysis of population census and GIS data, to investigate livelihood transformations and household wellbeing. There was a pressing need for pro-active government policies that stimulate local economic restructuring and livelihood opportunities and, as long as these local economies are insufficiently developed, that facilitate circular labor migration. Sridhar (2020) claimed that quality and access to education were the major concerns in rural schools as there were fewer committed teachers and a lack of proper textbooks and learning materials in the schools. Though Government schools existed, when compared to private schools, their quality was a major issue. He described the pitiable plight of rural schools in India. “Some government schools in rural India were overly packed with students, leading to a distorted teacher–student ratio. In one such remote village in Arunachal Pradesh, there were more than 300 students in class X which makes nearly 100 students in each classroom. In such a situation, it was impossible for teachers to pay full attention toward each and every student, even if they were willing to help. Meganathan (2011, 2022) said that with the advent of liberalization of the Indian economy in the 1990s and the growth of private institutions in education, the role and place of English had been redefined. Klonner and Oldiges (2022) recommended suggestion that public employment programs hold significant potential for reducing poverty and insuring households against various adverse implications of seasonal income shortfalls—when properly implemented. From the light of the literature review, it is identified the gap that existed in the present education system in upskilling students and recognized effective methods to be adopted to improve the quality of the students in the job market.

Methodology

A two-group simple randomized design was used in this study. The investigators carried out an experimental study with sixty rural government high school students using captivating activities, in which the medium of instruction is English. A total of sixty students were randomly divided into two groups, namely, the controlled group and the experimental group. These two groups acted as samples for the activities that were given to them. Earlier, a pre-test was conducted between the controlled and experimental groups.

The experimental group students were trained through ‘captivating activities’ focusing on LSRW skills. For listening, the training began with an audio track that was meant specially for learning pronunciation. Next, the videos were taped in an Indian accent, and then, TED talks by Indian speakers were also played to test the listening skills of the trainees. Initially, the trainees were asked to identify the difference in the pronunciation. Then in due course, videos that were meant for kids, such as stories in Britain and American accents, were played.

For the speaking activity, students were asked to come up with the names of the vegetables that they consume every day. For instance, they were familiar with certain veggies such as tomato, potato, and brinjal, whereas they were not aware of cluster beans, saber beans, yam, shallots, and so on. However, they were aware of onions but not of shallots. They insisted on accumulating as many vocabularies as possible and making it active to retain their proficiency. When vocabularies were kept alive, they remained active; otherwise, they became passive. This was the reason why students struggled to pick up words when they spoke. This concept had to be instilled in the young minds to know the value of vocabulary enrichment. Then, they were asked to list out the names of the things that they saw in the classroom with the right pronunciation. Accumulation of vocabulary happens even from kindergarten, but the significance of reciting nursery rhymes has been forgotten. Each rhyme has its own special vocabulary to synthesize these vocabularies in their day-to-day life. Lack of awareness in learning rhymes led to blind recitation of rhymes by non-native speakers of English.

Reading is one of the receptive skills that fine-tune an individual speaker. The trainees were asked to read content from a newspaper, preferably the snippets of their own choice. It may be sports, politics, editorials, or news about celluloid characters. Reading demands self-interest, which cannot be enforced. A devoted reader comes out with a fruitful outcome after the completion of reading a book of his own choice. This message is ingrained in the young minds for their future success. The students were asked to read silently so that their focus on the content would be in-depth. Eventually, this helped them to avoid reading for the second time to comprehend. As far as writing is concerned, the trainees were asked to ponder over the listening and writing and transfer their understanding from pen to paper. In all the training, they were advocated as well as encouraged by the trainers to express themselves without fear and inhibition because this was the primary step for them to self-check their capability. The baby steps that they take serve as a launching pad for them to chisel their LSRW skills. Writing is a penance to get a boon called proficiency in speaking. So the trainees were motivated to write without caring much about grammar and semantics.

After a fortnight of training, the select students who had undergone training, in addition to their curriculum during the special hours (after school hours), took up a test based on the captivating activities that they were trained in. The result was analyzed based on the performance before and after the training. Eventually, the post-test was conducted between the controlled and experimental groups, and it was analyzed.

Analysis

The data collected in the pre-test and post-test between groups were analyzed using statistical tools, such as mean, standard deviation, and paired sample t-test. On the whole, 30 participants were involved in the pre-test and post-test for the controlled and experimental groups; moreover, the group segregations were carried out randomly.

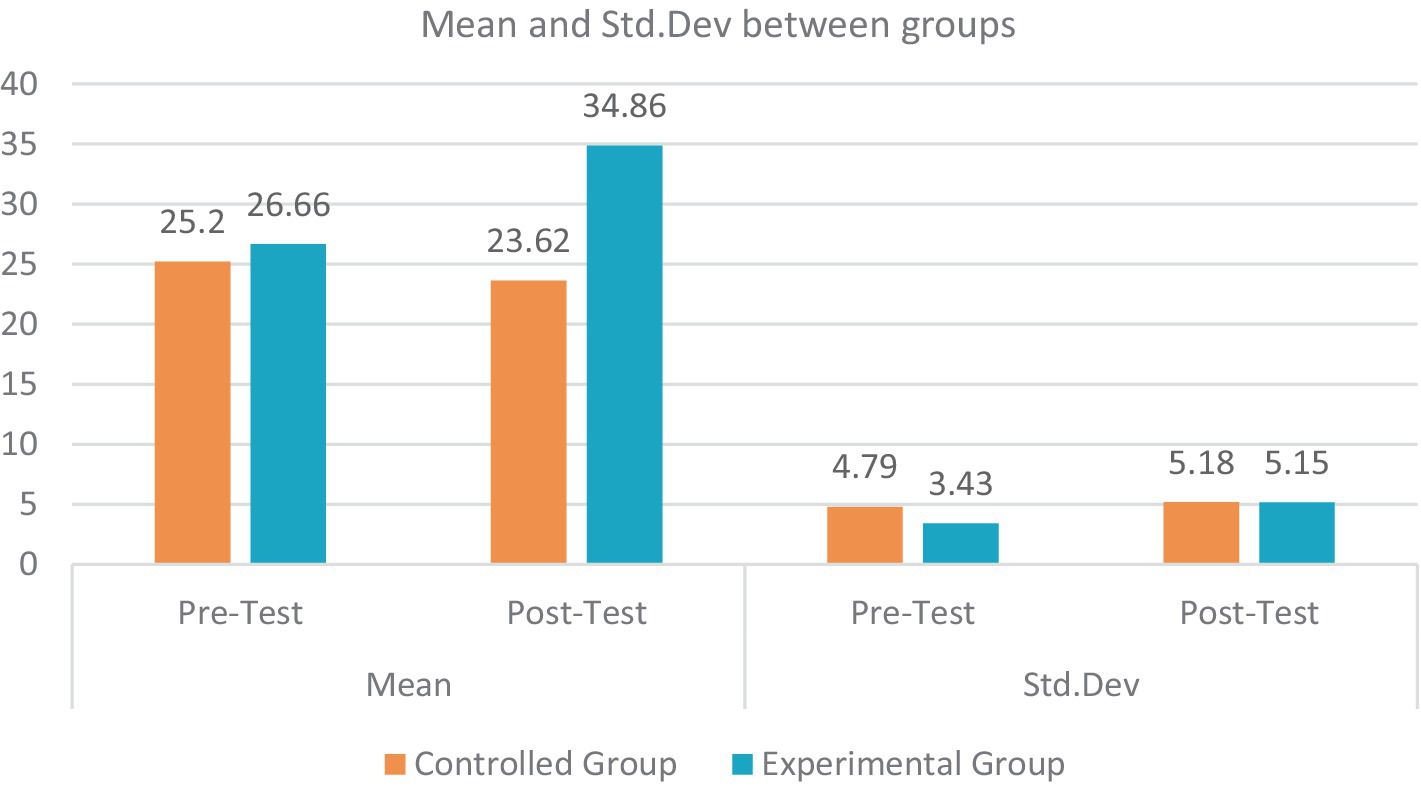

Figure 1 shows the mean and standard deviation of the controlled group and experimental group. For the controlled group, the mean values for the pre-tests and post-tests were 25.2 (Std.Dev = 4.79) and 23.62 (Std.Dev = 5.18), respectively. Similarly, for the experimental group, the mean values for pre-tests and post-tests were 26.66 (Std.Dev = 3.43) and 34.86 (Std.Dev = 5.15), respectively. It showed that the post-test values of the experimental group were increased slightly. To know the eloquent differences, a paired sample t-test was carried out between the controlled group and experimental group, and the results are as follows:

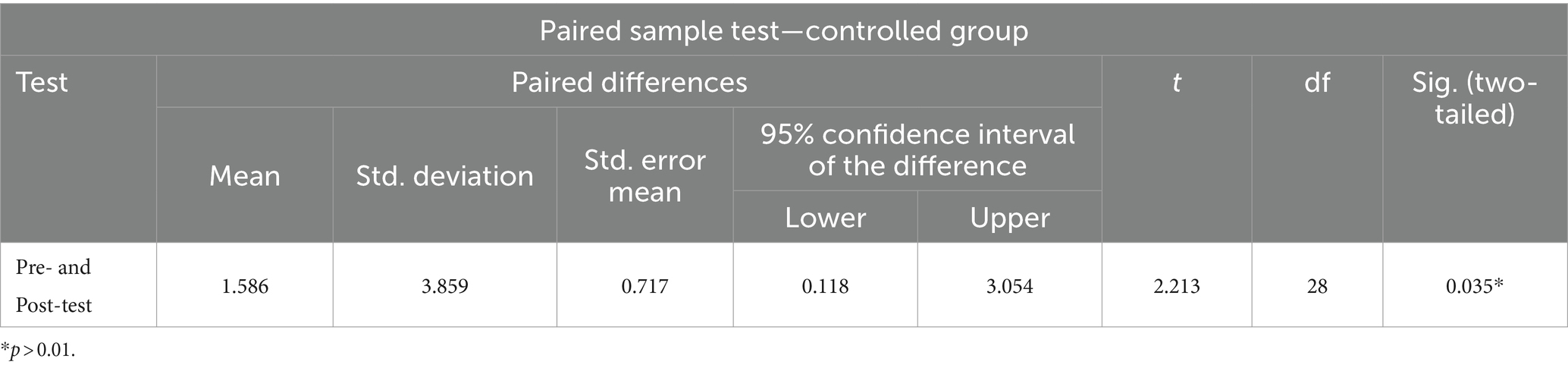

From Table 1, it is identified that the pre-test scores and post-test scores of the controlled group were not positively correlated; moreover, there were no significant average differences observed between the pre-test and post-test scores (t28 = 2.213, p = 0.035, p > 0.01). In addition, the pre-test and post-test scores were more or less similar (95% confidence interval [0.118, 3.054]).

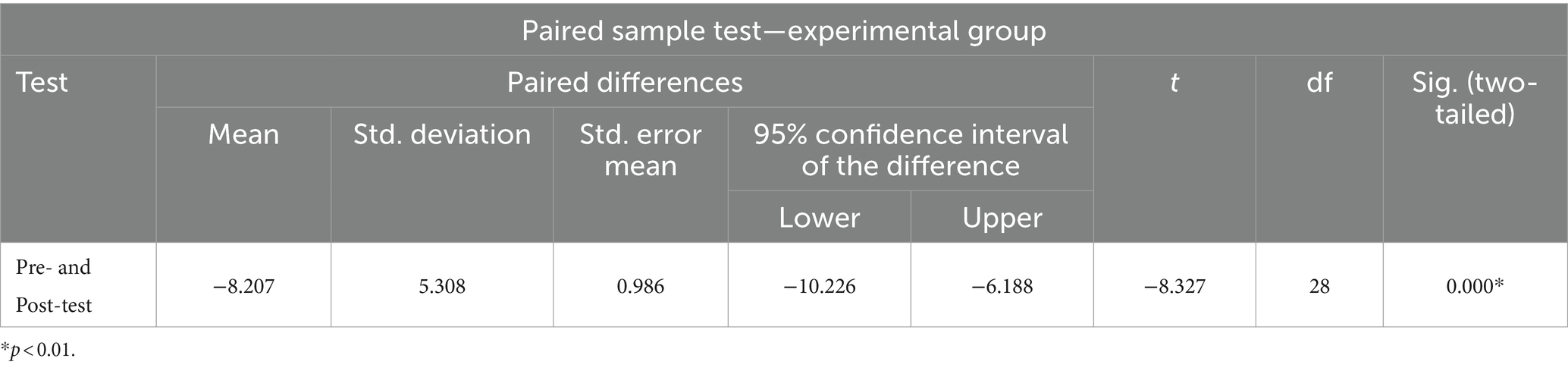

From Table 2, it is observed that the pre-test scores and post-test scores of the experimental group were positively correlated; moreover, there was a significant average difference observed between the pre-test and post-test scores (t28 = 8.327, p = 0.000, p < 0.01). In addition, post-test scores were 8.207 points higher than pre-test scores (95% confidence interval [−10.226, −6.188]).

Discussion

Captivating activities covering LSRW that were planned for a short period of time in the selected schools had created a seismic ripple effect among the students to acquire the language. It was foolproof evidence for the investigators that the same training when offered as a part of the curriculum would show a change in the learning aspects of the students. Memorizing components and grammar exercises could be replaced with exercises that kindled the interest of the students so that the students tried to make an effort on their own to enrich their proficiency. Young students are willing to learn because they are like clay, so they can be molded in any form. However, the facilitators—teachers—should come forward to upskill and refresh themselves often. Eventually, the teachers might also be encouraged to attend workshops and orientation programs with an open mindset. Steinert et al. (2019) said that faculty development programs could enhance the teachers’ identity that could be used in professional development. Language when taught as a subject created a mind block for the students. They had a mind block and aversion toward that language. As a result, they failed to show improvement. The controlled group of students was encouraged by the trainers to apply grammatical rules consistently in all their writing across subjects. They were also trained to concentrate on listening to improve their pronunciation, as supported by the studies of Merzoug and Benyagoub (2021) and Imane (2016).

The importance of reading was highlighted to them to improve their speaking and writing skills. Lack of vocabulary prevented students from expressing their ideas. Until they feel that they have command over language, they should not stop being learners. A learner of all times can always excel. Once students gained mastery over a language, they could proceed further with their academics to gain subject knowledge.

In India, particularly in Tamil Nadu, government schools followed the same curriculum that was designed common for all students irrespective of their potential. They did not have any provision to select a subject of their choice until they completed their secondary class (tenth standard). Rote learning was practiced from their Kindergarten to their higher secondary classes. Ramadan (2016) said that “rote learning handicaps thinking and creation.” A few boards of education tried to change this age-old practice and set their own pattern to trigger the individual capability of students and enhance their potential. Though this was a daring step taken up by many schools, the caliber of the students is quite stunning. The liberty that they enjoy in learning the subject of their choice induces their passion to explore and learn a varied arena of knowledge. Is it possible to implement choice-based learning in government schools? It is not a million-dollar question. The education system we use currently is an age-old system initiated by Thomas Babington Macaulay. His Minute on Indian Education, issued in February 1835, was primarily responsible for the introduction of Western institutional education to India.

Insufficient resources in public schools and high rates of teacher absenteeism were the root cause for the rapid growth of private (unaided) schooling in India, particularly in urban areas. Private schools were divided into two types: recognized and unrecognized schools. Government ‘recognition’ was an official stamp of approval, and for this, a private school was required to fulfill several conditions, though hardly any private schools that got ‘recognition’ actually fulfilled all the conditions of recognition. Indian schools were no less than factories. The emergence of large numbers of unrecognized primary schools suggested that schools and parents did not take government recognition as a stamp of quality. The pitiable plight of the government-run schools remains the same even after ages. Central, State, and local bodies have taken steps to provide solutions to redress the issue. Even then the quality of education struggled to be improved. This research study focuses on the enhancement of the quality of learning through some captivating activities to acquire proficiency in English among the selected school students. Languages should not be taught. The positive effect of captivating activities on proficiency in the English language was also reported in the studies of Nget et al. (2020) and Silva-Valencia et al. (2021).

On the other hand, it should be acquired. Instead of conducting activities, the syllabus can be revised with activity-based contents in the textbook itself. In addition, teachers (the resource providers) too can involve themselves to the core to extract the hidden talents of the rural students. Initially, the efforts may be time-consuming, but once the students start picking up interest in language acquisition, they will not stop practicing by themselves. Facilitators and teachers can induce the curiosity of the learners to go in search of language acquisition before they enter the institutions for higher education.

Findings

Students who underwent training with captivating activities based on LSRW showed a change in their performance in the post-training test. There was progress in their communication skills. The training molded their LSRW skills, and they gained the confidence to address them. So they faced the test without much disturbance and were able to solve the questions without stress. It was obvious that students who attended only regular class hours could not cope with the performance of the selected students. Assimilation of the concept related to grammar and applying and using nuances of the English language in real life was literally a challenge for the students who did not have an English-speaking environment.

English classrooms in rural schools are teacher-centric, and this has to be changed to a learner-centric one. They lack confidence and lack the spirit of involvement in the former approach. Chaitanya and Ramana (2013) suggested that collaborative action research (CAR) methodology is employed by the researchers with the objective of overcoming the existing problems using role play as a tool. Role play is used effectively as a tool as it supports students’ participation and enriches their social skills. Similarly, Goel and Chauhan (2020) stated that “appropriate activities can be improvised around the text to encourage the students to think critically and creatively and develop their listening, speaking, reading, and writing abilities.” The teachers who worked in the government schools were not aware of the importance of second language learning. They felt comfortable with their mother tongue, and this led to the marginalization of English as a second language. The approach of the teachers should change. Teachers in rural areas should undergo orientation every year to know about the changing scenario in higher education and placement requirements. Though the medium of instruction was English for English Medium students in Government schools, they did not follow that strictly. If this ambiance changed, students will not encounter the obstacle of expressing their ideas coherently and confidently. John (2018), Jeisica (2018), Alshahrani (2019), and Toro et al. (2018) opined that “students’ active involvement in classroom activities can promote language learning.” In this experimental study, it showed that there was a significant difference observed between groups (t28 = 8.327, p = 0.000, p < 0.01).

Future scope

In this study, the researchers have limited their research to the communication skills of state board school children. Students pursuing their education in Government schools in particular were taken into account. The study can be conducted extensively among matriculation students and the CBSE board regarding soft skills and employability skills. Future investigations could focus on comparing placement skills among engineering students and arts college students. The same training using captivating activities can be given to students bi-annually for effective life-long learning.

Limitations

The research was carried out only in a government school exclusively for the students who were in eighth grade. In addition, only a limited number of students were trained and tested. Students pursuing their education in the state board alone were tested. Teachers concerned were not provided any awareness about the study.

Conclusion

The efforts that the investigators had taken while conducting the study with the controlled group were effective and constructive. In addition, the students from downtrodden backgrounds were able to express their opinions toward the training that they had undergone. They were not perfect in their expressions, but on day one, the experience that the researchers had encountered with the controlled group was totally different. The students who said that they were not able to follow the instructions initially then transformed themselves to be good listeners. They were able to communicate in bits and pieces, but confidently they shared their opinion. The researchers conclude that if all facilitators make concerted efforts to support every student, success is assured. This cannot be possible without steps taken by the facilitators as well as the authorities concerned, who try to implement various schemes for the deprived. The paucity of finance is a hindrance for under-privileged children to take up a paid course and equip themselves. Therefore, efforts that the government makes should be feasible and friendly for the stakeholders to be utilized so that they can have an efficient learning process even in government schools.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

RB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. SL: Data curation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AG: Software, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the government school and the participants for their kind cooperation in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aiyar, A., Rahman, A., and Pingali, P. (2021). India’s rural transformation and rising obesity burden. World Dev. 138:105258. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105258

Alshahrani, H. A. (2019). Strategies to improve English vocabulary and spelling in the classroom for ELL, ESL, EO and LD students. Int. J. Modern Educ. Stud. 3, 65–81. doi: 10.51383/ijonmes.2019.41

Budiman, B., Putra Ishak, J. I., Rohani, R., and Lalu, L. M. H. (2023). Enhancing English language proficiency: strategies for improving student skills. J. Scient. Res. Educ. Technol. 2, 1118–1123. doi: 10.58526/jsret.v2i3.205

Caleb, M. F., Kumar, A. C., and Madhav, A. K. (2019). Government's policies of commercializing rural education-a new perspective towards educating rural youths. Asian J. Manag. 10, 19–24. doi: 10.5958/2321-5763.2019.00004.0

Chaitanya, E. K., and Ramana, K. V. (2013). Role play-an integrated approach to enhance language skills (LSRW) of the ESL learners-a collaborative action research report. Lang. India 13, 23–35.

Chavan, R. (2024). New education policy of India – How it is transforming India’s education landscape. India: Leadership Boulevard Private Limited.

Chermakani, G., Loganathan, S., Rajasekaran, E. S. P., Sujetha, V. M., and Stephesn, O. B. V. (2023). Language learning using muted or wordless videos - A creativity-based edutainment learning forum. e-mentor, 2, 22–30. doi: 10.15219/em99.1608

Choithani, C., van Duijne, R. J., and Nijman, J. (2021). Changing livelihoods at India’s rural–urban transition. World Dev. 146:105617. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105617

Das, S., and Biswas, A. K. (2021). Quality and determinants of primary education in rural India. Indian J. Hum. Dev. 15, 323–333. doi: 10.1177/097370302110368

Goel, N., and Chauhan, S. (2020). Using drama techniques in language learning: teachers’ perception. Impact: international journal of research in humanities. Arts Literat. 8, 61–66.

Goldman, A. M. (2019). Interpreting rural students’ stories of access to a flagship university. Rural Educ. 40, 34–46. doi: 10.35608/ruraled.v40i1.530

Imane, K. K. (2016). Enhancing EFL learners’ speaking skill through effective communicative activities and strategies the case of first year EFL students. Algeria: University Of Tlemcen.

Jeisica, J. (2018). Enhancing students’ speaking skill using communicative language teaching method. J. English Lang. Literat. Teach. 3, 12–29. doi: 10.36412/jellt.v3i01.738

John, D. (2018). Learning LSRW skills through active student-involvement: screening an edited film. Teach. English Technol. 18, 115–128.

Joseph, D. H., and Windchief, S. R. (2015). Nahongvita: a conceptual model to support rural American Indian youth in pursuit of higher education. J. Am. Indian Educ. 54, 76–97. doi: 10.1353/jaie.2015.a835505

Kasana, A., and Saxena, S. (2024). The National Education Policy 2023: India's pathway to global educational prominence. IRJHIS 5, 198–208.

Klonner, S., and Oldiges, C. (2022). The welfare effects of India’s rural employment guarantee. J. Dev. Econ. 157:102848. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2022.102848

Li, Y. (2023). A systematic review of rural resilience. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 15, 66–77. doi: 10.1108/CAER-03-2022-0048

Meganathan, R. (2011). Language policy in education and the role of English in India: From library language to language of empowerment.

Meganathan, R. (2022). “Language Conundrum: English Language and Exclusivity in India’s Higher Education” in Critical Sites of Inclusion in India’s Higher Education. Ed. P. Sengupta (Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan).

Merzoug, I., and Benyagoub, L. (2021). Improving EFL Learners’ Communicative Competence Using Web-based Materials (Doctoral dissertation, Ahmed Draia University–Adrar).

Moresebetoa, P. (2016). Learners’ challenges in reading and writing in English first additional language in the intermediate phase in Mankweng circuit. Mankweng: University of Limpopo.

Nandy, A., Tiwari, C., and Kundu, S. (2021). India’s rural employment guarantee scheme–how does it influence seasonal rural out-migration decisions? J. Policy Model 43, 1181–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.jpolmod.2021.09.001

Nchabeleng, B. K. (2022). An investigation of the challenges experienced on the development of listening and speaking skills: A case of two selected high schools in Mahwelereng circuit, Limpopo Province. Mankweng: University of Limpopo.

Nget, S., Pansri, O., and Poohongthong, C. (2020). The effect of task-based instruction in improving the English-speaking skills of ninth-graders. Learn J. 13, 208–224.

Nookathoti, T. (2022). The dichotomy in India’s education system–a macro level analysis. Educ. Philos. Theory 54, 606–618. doi: 10.1080/00131857.2021.1897568

Patel, S. A. (2018). India’s emerging economy: E-learning: Challenges & opportunities in rural India : ACUMEN.

Pearson, W. (2019). Persistence of adult students. J. Contin. High. Educ. 67, 13–23. doi: 10.1080/07377363.2019.1627166

Policy for National Education (NEP) (2023). Information and communication technologies in teacher education: A planning guide. Available at: https://dsel.education.gov.in/sites/default/files/guidelines/ncf_2023.pdf

Resta (2002). Information and communication technologies in teacher education: A planning guide. Paris: UNESCO.

Silva-Valencia, J. C., Villacís-Villacís, W., and Hidalgo-Camacho, C. (2021) Speaking skills development through communicative language teaching techniques. Conference: 3rd international academic conference on education, teaching and learning, London, UK.

Singh, J. D. (2011). Higher education in India–issues, challenges and suggestions. High. Educ. 1, 93–103.

Sridhar, S.. (2020). Review study on importance of rural education in India. In Proceedings of Cloud based Technical Symposium, International Journal of Innovative Technology and Research (pp. 17–20).

Steinert, Y., O’Sullivan, P. S., and Irby, D. M. (2019). Strengthening teachers’ professional identities through faculty development. Acad. Med. 94, 963–968. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002695

Swargiary, K., and Roy, K. (2014). Systematic Review of the Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan: Evaluating Access, Quality, Inclusivity, Digital Education, and Implementation Challenges. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4879121 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4879121 (Accessed June 01, 2024).

Toro, V., Camacho-Minuche, G., Pinza-Tapia, E., and Fabian Paredes, F. (2018). The use of the communicative language teaching approach to improve students’ oral skills. Engl. Lang. Teach. 12, 110–118. doi: 10.5539/elt.v12n1p110

Keywords: communicative skills, rural students, captivating activities, language, pedagogy

Citation: Boobalan R, Loganathan S and Gyamfi A (2024) Augmentation of communicative skills among rural high school students in India. Front. Educ. 9:1413643. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1413643

Edited by:

Reza Zabihi, University of Neyshabur, IranReviewed by:

Balwant Singh, Partap College of Education, IndiaNeni Hermita, Riau University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2024 Boobalan, Loganathan and Gyamfi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Abraham Gyamfi, YWJyYWhhbWd5YW1maTg0QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†ORCID: Rathika Boobalan, orcid.org/0000-0002-1606-571X

Saranraj Loganathan, orcid.org/0000-0003-0918-4849

Abraham Gyamfi, orcid.org/0000-0002-3189-1825

Rathika Boobalan1†

Rathika Boobalan1† Saranraj Loganathan

Saranraj Loganathan Abraham Gyamfi

Abraham Gyamfi