- 1Institute of School Violence Prevention, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

- 2Department of Education, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

The need for effective school bullying prevention programs is more pronounced than ever. To address school bullying, Korea has operated the Youth Police Academy (YPA) since 2014. Although the School Police Officers (SPOs) in charge at YPA can provide valuable insights into the significance of school bullying prevention programs, there has been limited research in this area. The purpose of this study is to explore the relevance of school bullying prevention programs and delineate the role of YPA in preventing school bullying, based on the professional experiences and perspectives of YPA’s SPOs. We employed narrative analysis based on interviews with SPOs. The findings revealed that while the majority of SPOs experienced career crises, they overcame these challenges and developed professional perspectives on the YPA program and anti-bullying program. SPOs perceive that school bullying prevention program should focus on “resolving relationships,” “collaborative care,” and “teaching coping behaviors.” Accordingly, YPA can function as a “place of reconciliation,” “place helping students understand others’ perspectives through experiential and case-based educational approaches,” “hub for school bullying prevention education grounded in collaboration with relevant institutions and local experts,” “provider of coping information,” and an “active protector of victims.”

1 Introduction

In Korea, from December 2011 to January 2012, three students committed suicide due to school bullying. In response to these tragic incidents, the South Korean government undertook a comprehensive policy transformation on school bullying in 2012. On February 6, 2012, the “Comprehensive Measures to Eradicate School Violence” was announced, and the first national survey on the actual state of school bullying was conducted (Hong et al., 2023, p.64). According to the survey of approximately 3,790,000 students in grades 4–12, 8.5% of students reported that they have experienced school bullying in 2012 (Ministry of Education, 2013). In the 2022 national survey on the actual state of school bullying, conducted with 3,214,027 students in grades 4–12, the response rate for bullying victimization significantly decreased to 1.7% (Ministry of Education, 2022). However, despite the decrease in bullying victimization rates, the experience of suicidal and self-injurious impulses following school bullying remains serious, reaching up to 38.8% in 2023, according to a survey by the Blue Tree Foundation, a Korean NGO, which surveyed 7,242 students (The Blue Tree Foundation, 2023).

To address school bullying, the Korean government has been enforcing the “Basic Plan for School Bullying Prevention and Countermeasures” every 5 years since 2005 (Ministry of Education, 2020). Issues such as low autonomy at the school level, perfunctory bullying prevention education, and insufficient protection for victimized students were identified as urgent concerns (Ministry of Education, 2013). Therefore, the third Basic Plan focused on the development and dissemination of the “Eoullim” program (the Korean version of Kiva), activation of autonomous preventive activities in schools, development of empathy programs involving cultural and artistic activities such as theater and musicals, tailored responses based on the type of bullying, region, and school level, and the expansion of Wee Classes, school counseling facilities, through the Wee Project (Ministry of Education, 2013). However, changes in the nature of school bullying, such as the intensification of cyberbullying, insufficient support for victimized students, and limitations in fostering genuine reconciliation between students have emerged as significant challenges (Ministry of Education, 2020). Moreover, where the role of school teachers alone proves insufficient in preventing school bullying (Hikmat et al., 2024), there is a continuous need to explore how to design effective school bullying prevention education today.

Youth Police Academy (YPA) program is an experiential school bullying prevention program, which was adopted as a part of the “2014 Field-oriented School Bullying Countermeasures Plan.” The YPA program involves School Police Officers (SPOs), current police officers assigned to address school violence issues in Korea (Kim and Hwang, 2018, p.2), conducting experiential school bullying prevention education in Youth Police Academies established in various regions. The program aims to instill a sense of mission in students by combining practical experiences with police simulations. While supporting the operation of YPA program in 2022, we found that YPA program has been relatively under-discussed. Additionally, Existing discussions on the significance and effectiveness of the YPA program have been conducted without the involvement of the SPOs responsible for its implementation (Han et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2021), even though SPOs seem to develop their professional perspective on anti-bullying program.

The purpose of this study is to explore the relevance of school bullying prevention programs and delineate the role of YPA in preventing school bullying, based on the professional experiences and perspectives of YPA’s SPOs. Therefore, we employed a narrative inquiry for an in-depth exploration of the relevance of bullying prevention programs from the perspective of SPOs. Given that SPOs operating within the YPA are a highly unexplored group, it was essential to understand their characteristics and how they develop their professional identity first. To this end, we specifically address the following research questions:

1. How do School Police Officers (SPOs) form their professional identity?

2. What does school bullying prevention convey from the perspectives of SPOs in YPA?

3. What does the “Youth Police Academy” represent for the role of school bullying prevention?

2 Background

2.1 School bullying prevention program

Bullying is defined as repeated actions with the intention to harm victims by exploiting an imbalance of power (Olweus, 1992; Farrington, 1993; Farrington and Ttofi, 2009). Various school bullying prevention programs have been developed to reduce school bullying (Park, 2019). For example, the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program (OBPP) was first developed in Norway (Olweus, 1992). Finland’s KiVa program (Salmivalli and Poskiparta, 2012), the Be-Prox Program in Switzerland (Farrington and Ttofi, 2009), and Friendly Schools in Australia (Farrington and Ttofi, 2009) have also been introduced.

Farrington and Ttofi (2009) conducted a systematic review of 44 international anti-bullying programs and concluded that school-based anti-bullying programs are often effective, with bullying decreasing by 20–23% and victimization decreasing by 17–20%. Recent studies have evaluated diverse anti-bullying programs through meta-analyses (Gaffney et al., 2019a; Kennedy, 2020). These studies have shown that the effectiveness of school-based bullying prevention programs varies depending on factors such as gender, race, age, location of implementation, and school climate (Bowllan, 2010; Ttofi and Farrington, 2012; Gaffney et al., 2019b; Kennedy, 2020). Despite the significant increase in research on bullying prevention programs, much remains to be learned about how to design and implement effective intervention programs (Farrington and Ttofi, 2009). Given that most research has been conducted using systematic reviews and meta-analyses, qualitative research can provide an alternative approach to exploring effective anti-bullying programs.

2.2 Youth police academy program

The Youth Police Academy (YPA) is anti-bullying program aimed at enhancing students’ abilities to prevent school bullying by offering diverse experiential opportunities. The program takes place in local police stations transformed into experiential learning spaces and includes student-centered activities such as role-plays addressing school bullying, police career experiences, and region-specific programs. Recognized as an innovative experiential school bullying prevention initiative, the YPA provides career education through police occupation experiences (Ministry of Education, 2013; Lee et al., 2021). The program’s objectives include transforming bystanders, teaching effective coping strategies, and fostering empathy, anti-bullying attitudes, and legal compliance (Han et al., 2021).

Launched in 2014, the YPA was introduced by the Korean government to emphasize field-centered, experiential approaches to school bullying prevention, moving away from passive lecture-oriented education. In this context, the YPA pilot began in May 2014 through 19 police stations nationwide, expanding to 39 in 2016, 50 in 2018, 51 in 2019, and reaching 52 in 2020. From 2021 to 2023, it further expanded to 55 locations. The YPA operates under the joint jurisdiction of the Ministry of Education and the National Police Agency, with collaboration from regional education offices and implementing agencies (Korea Youth Policy Institute in 2014, Ewha Womans University School Violation Prevention Research Institute from 2015 to 2024). The Ministry of Education formulates the project plan and provides special grants, while regional education offices promote local Youth Police Academies to nearby schools and support the recruitment of students for the program. Implementing agencies assist in budget execution, conduct on-site consultations, and organize performance reporting meetings. The National Police Agency provides and improves the standard education model of YPA, offering education facilities, equipment, and operators. Within this cooperative framework, the practical operation of Youth Police Academy is overseen by school police officers assigned by local police stations.

Han et al. (2022) classify the YPA program into two types: the standardized program, implemented universally as a baseline across all youth police academies, and the autonomous program, adapted to the unique situations of each youth police academy. The standardized program includes “school bullying prevention education, police experience (police equipment and uniform experience, forensic investigation, simulation shooting), and school bullying prevention role-playing” (Lee et al., 2021, p. 63; Han et al., 2022). This program is typically conducted for 2–3 h. In addition to the standardized program, some youth police academies implement their own programs tailored to the characteristics of their regions. The autonomous programs encompass various educational activities, such as psychological counseling, art therapy, CCTV control center experience, mock trial experience, illegal filming prevention classes, school bullying prevention education involving parents, online forensic investigations, online psychological dramas utilizing virtual reality, virtual Youth Police Academy, awareness improvement education for socially vulnerable groups such as multicultural students and students with disabilities, and outreach youth police academy (Lee et al., 2021, p. 64; Han et al., 2022).

In summary, the Youth Police Academy program aims to provide school bullying prevention education beyond what schools can offer and seeks direct effects on school bullying prevention through experiential programs. While research exists on the effectiveness of the overall Youth Police Academy program in preventing school bullying, studies exploring the perspectives of Youth Police Academy officers, who are practitioners in the field, regarding the relevance of the program are lacking. Therefore, exploring the perceptions of Youth Police Academy officers in charge, SPOs, can provide insights into the current status of the Youth Police Academy program and guide the direction of school bullying prevention programs.

2.3 School police officer

The School Police Officers (SPOs) are current police officers assigned to schools to handle school violence problems in Korea (Kim and Hwang, 2018, p. 2). They are similar to America’s School Resource Officers (SROs), except that Korean SPOs are not armed with a gun and their role is more focused in school bullying prevention. The SPO system originated from the “School Police” policy, initially implemented in Busan in 2005. The School Police policy involved retired police officers and teachers to ensure school security. However, it gained momentum, and the “School Police Officer (SPO)” policy expanded nationwide in 2012, following the suicide incident involving middle school students in Daegu (Kim and Choo, 2017). The role of the SPOs includes ‘prevention and response activities for eradicating school bullying, building a cooperative system with schools for school bullying cases, conducting customized leadership activities and post-management for specific individuals’ (Kim & Hwang, 2018, p.5; National Police Agency, 2021). Moreover, some SPOs are additionally in charge of YPA in their region.

However, there is a lack of research focusing on the SPO’s perspective to expand the knowledge of anti-bullying programs. Research on School Police Officers can be broadly categorized into studies on their roles (Shin and Kim, 2016; Kim & Hwang, 2018, p.5; Lee and Park, 2020; National Police Agency, 2021), and those addressing issues of SPO policy, exploring improvement measures (Joe, 2016; Kim and Choo, 2017; Kim and Hwang, 2018). Specifically, identified problems in the School Police Officer system include insufficient information sharing between schools and SPOs due to the lack of a control tower, excessive workload, the absence of clear manuals leading to unclear duties, low practical professional qualifications during the recruitment process, and a lack of education (Joe, 2016; Kim and Choo, 2017; Kim and Hwang, 2018). Various improvement suggestions have been proposed to address these issues, including extending the tenure of School Police Officers to mitigate issues related to personnel movement and low professional qualifications, separating the exam system for School Police Officers from the general police exam to enhance professionalism, increasing continuous recruitment, minimizing the number of assigned schools per School Police Officer, and establishing action guidelines or manuals for School Police Officers (Kim and Choo, 2017; Kim, 2020). While existing research on school police officers provides insights into the overall school police officer system, the majority of studies focus on macroscopic analyses of the system (Kim, 2019). There is a lack of discussion regarding the realities of Youth Police Academy and the direction of school bullying prevention program, specifically concerning the school police officers responsible for YPAs. Therefore, the need for in-depth research targeting practitioners in YPAs is emphasized once again.

3 Methods

This study aims to explore the relevance of school bullying prevention programs and delineate the role of YPA in school bullying prevention from the perspective of School Police Officers in charge of the Youth Police Academy, whose voices have been relatively unexplored. To achieve this, the study employs a qualitative research method conducted as a narrative inquiry, combining framework of Clandinin and Connelly (2004) and Savickas (2012). This approach prioritizes the participants’ world, suitable for exploring their experiences and understanding their perceptions through dialogues between researchers and participants (Lee and Kang, 2011).

3.1 Participants

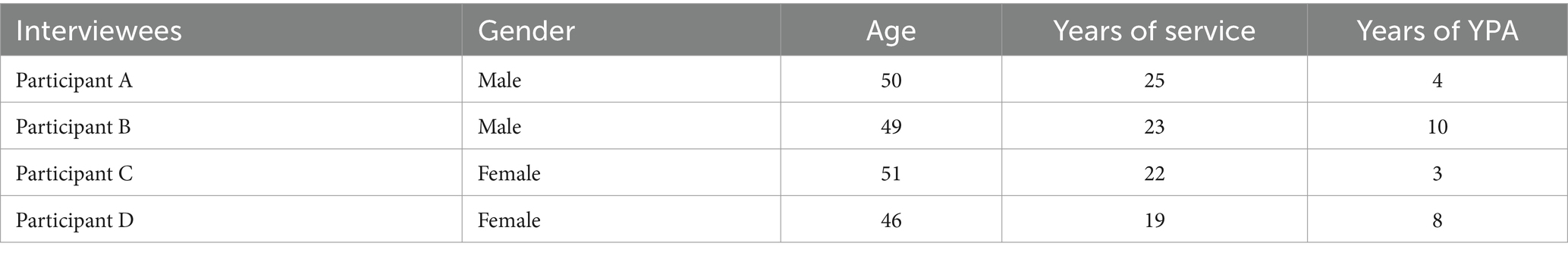

Participants are selected using purposive sampling. Purposive sampling enables the detailed exploration and understanding of the issue (Mergel et al., 2019). For precision and academic rigor, sampling criteria have to be pre-decided based on factors such as sociodemographic characteristics, specific experiences, behaviors, and roles, etc. (Mergel et al., 2019). To select SPOs with extensive experience and a deep understanding of the YPA program, we considered factors such as “over three years of YPA operation, region, gender and quality of YPA operation in the selection process.” Due to the operational characteristics of the Youth Police Academy (YPA), there are frequent changes in personnel. Therefore, we believed that at least 3 years of experience were required to form their perspective and identity, which is essential to this study. To avoid regional bias, we chose SPOs working in different regions. Gender ratio was also considered. Additionally, the authors had connections with all the SPOs through managing the YPA support project for 6 months. This involvement allowed us to receive monthly operational reports, enabling us to understand the current state of operations. Consequently, we examined SPOs based on their involvement in addition to years of operation, region, and gender. Ultimately, four Youth Police Academy SPOs were deliberately chosen. A brief summary of the background of the interviewees is presented in Table 1.

In August 2022, during on-site consultations at YPAs, researchers explained the overview and plan of the study. Subsequently, the research overview and the consent form were provided via email, ensuring voluntary agreement for research participation.

3.2 Data collection

The data used for narrative analysis were gathered through semi-structured interviews. All the questions were shared with participants before the interview, and additional questions were added if more detailed explanation was required. All interviews were conducted jointly by the authors to enhance objectivity and facilitate thorough discussion within the study. Given geographical constraints and COVID-19 considerations, interviews were individually conducted through Zoom meetings and recorded. These interviews occurred between August and October 2022, with each session lasting approximately 1 h and 30 min to 2 h per participant.

The questions in the interview were prepared based on Savickas (2012, p. 15)’s framework and the research questions. The entire instrument consists of 15 questions, divided into two sections. The first section delves into in-depth inquiries regarding the SPO’s career identity development. This part of the interview covers topics such as reasons for becoming a Youth Police Academy (YPA) officer, early experiences in YPA duties, challenges faced and how they were overcome, mid-career experiences, and fulfilling experiences. The interview questions follow a chronological order from past career experiences to recent ones, incorporating discussions on “experiences and expectations,” “actions, processes, and outcomes in various environments,” “relationships with others,” and “predictions about the future,” as suggested by Savickas et al. (2009, 248).

The second section of the interview aims to investigate the relevance of the bullying prevention program and the role of YPA in school bullying prevention. This part includes questions regarding the primary purpose of YPA, the approach and objectives in conducting school bullying prevention programs, the challenging aspects of implementing these programs, and perceptions of YPA’s role in anti-bullying efforts. The specific questions used in the interview are provided in Appendix A. Moreover, observational notes were taken during the interviews to capture nuances, pauses, expressions, gestures, and behavioral characteristics. Audio recordings were transcribed after each interview, and the transcripts were meticulously reviewed to ensure accuracy.

3.3 Analysis

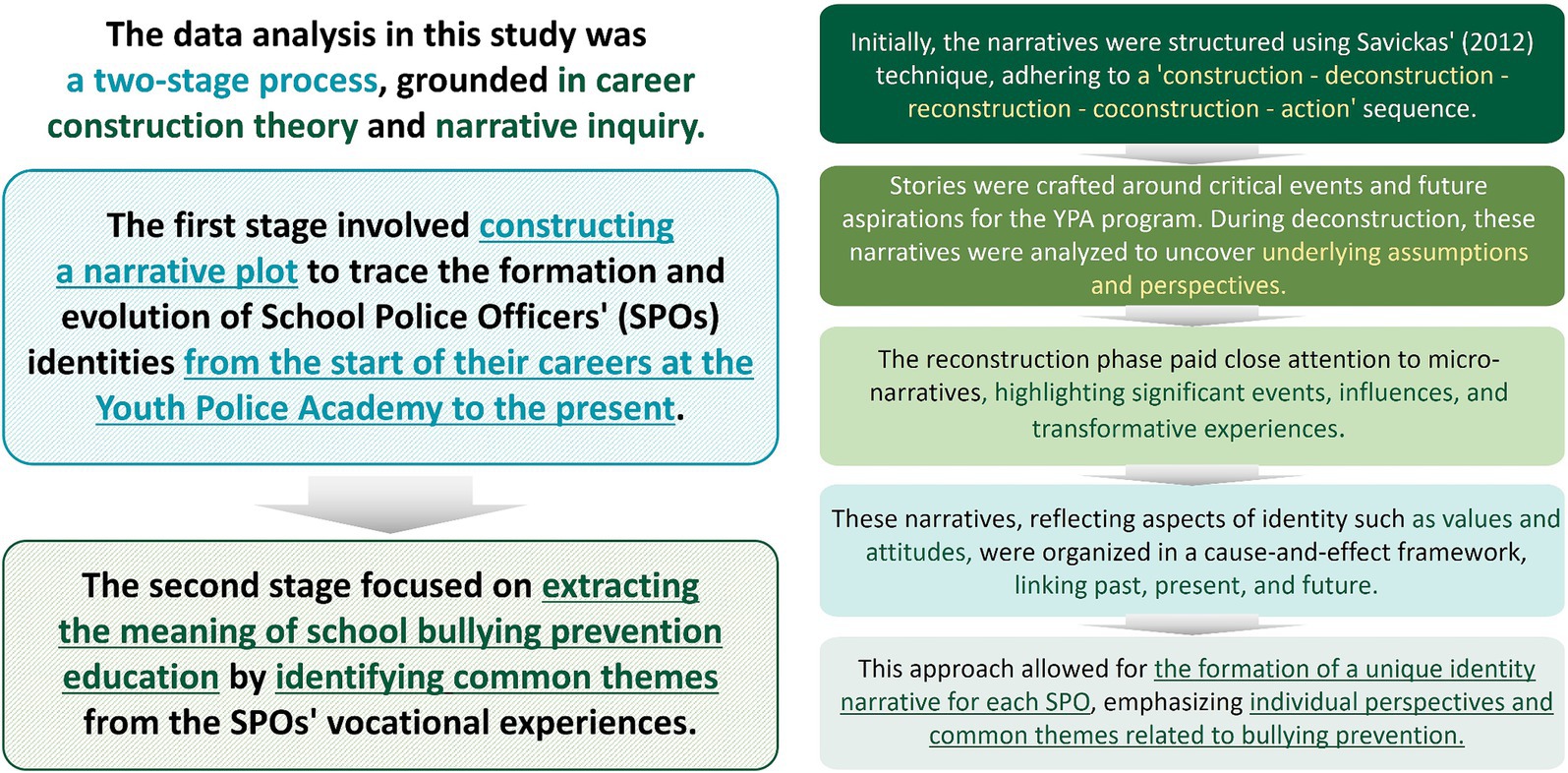

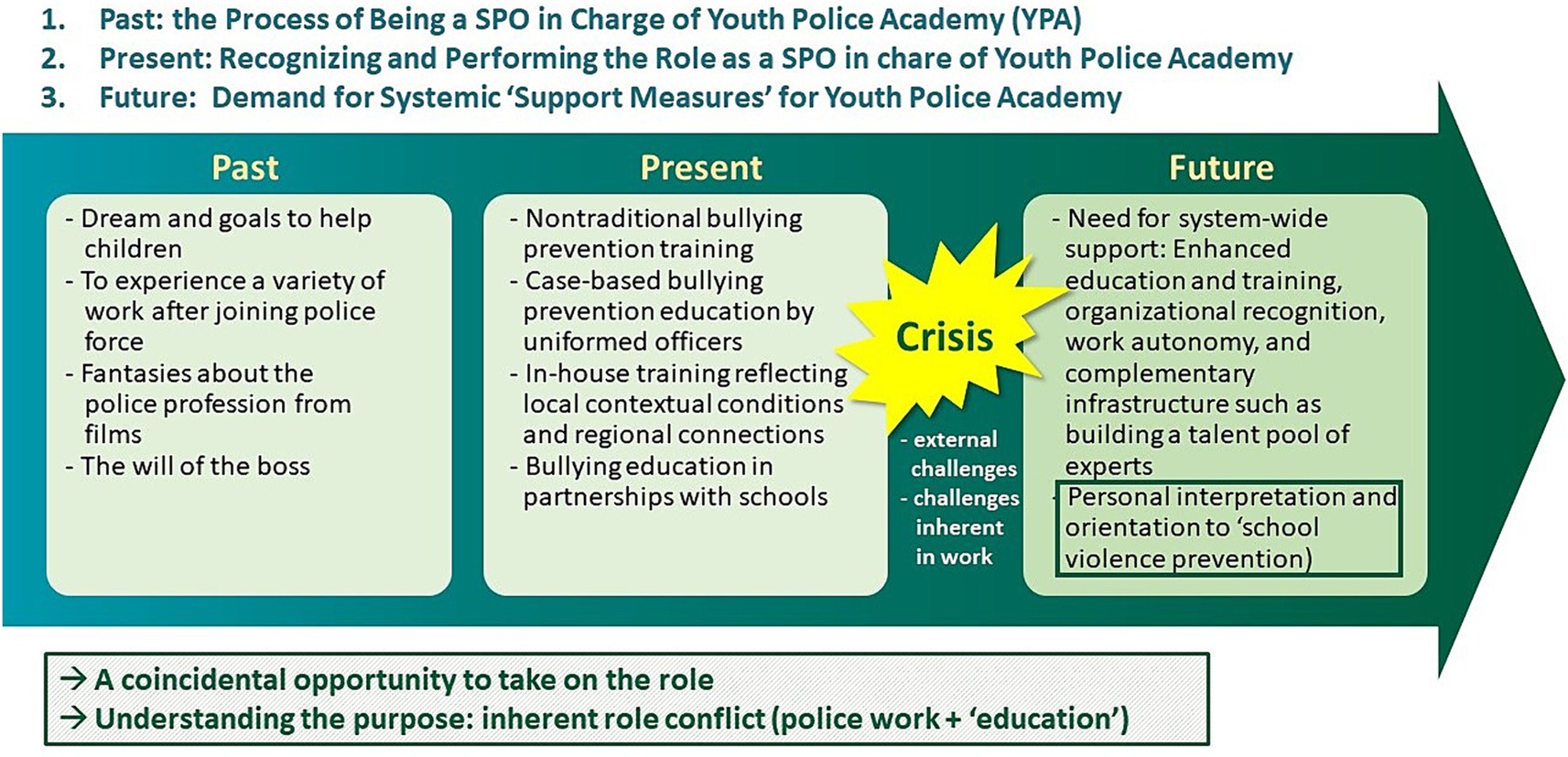

As shown in Figure 1, the data analysis unfolded in two stages, drawing on career construction theory and narrative inquiry (Clandinin and Connelly, 2004; Savickas et al., 2009; Del Corso and Rehfuss, 2011). The first stage involved constructing a narrative with a plot structure, exploring the formation and transformation of SPOs’ identities from the beginning of their careers at the Youth Police Academy to the present. The second stage aimed to derive the meaning of school bullying prevention education by identifying common themes related to the bullying prevention program formed through their vocational experiences.

In the initial step, the transcripts were organized into a narrative format following narrative analysis technique of Savickas (2012). It followed the sequence of “construction - deconstruction - reconstruction - coconstruction – action,” suggested by Savickas (2012), and this study progressed up to the reconstruction phase. Their stories were constructed, encompassing events leading to crises or confusion and the goals for a hopeful future YPA program. Subsequently, in a “deconstruction” process, researchers read the constructed narratives to identify assumptions, omissions, or inaccuracies, allowing for a new perspective on their career stories. In the “reconstruction” phase, attention was focused on micro-narratives containing specific details such as significant events, recurring episodes, important people, meaningful moments, and experiences that could bring about life changes. These detailed narratives, reflecting aspects of identity like values, attitudes, and habits, were arranged in a cause-and-effect format linking the past, present, and future. Emphasizing each individual’s “identity-related plot” or “common themes related to bullying prevention education,” a unified and unique identity narrative for each individual was created.

4 Results

4.1 The analysis of SPO’s career-identity scenario

4.1.1 From the past to the present

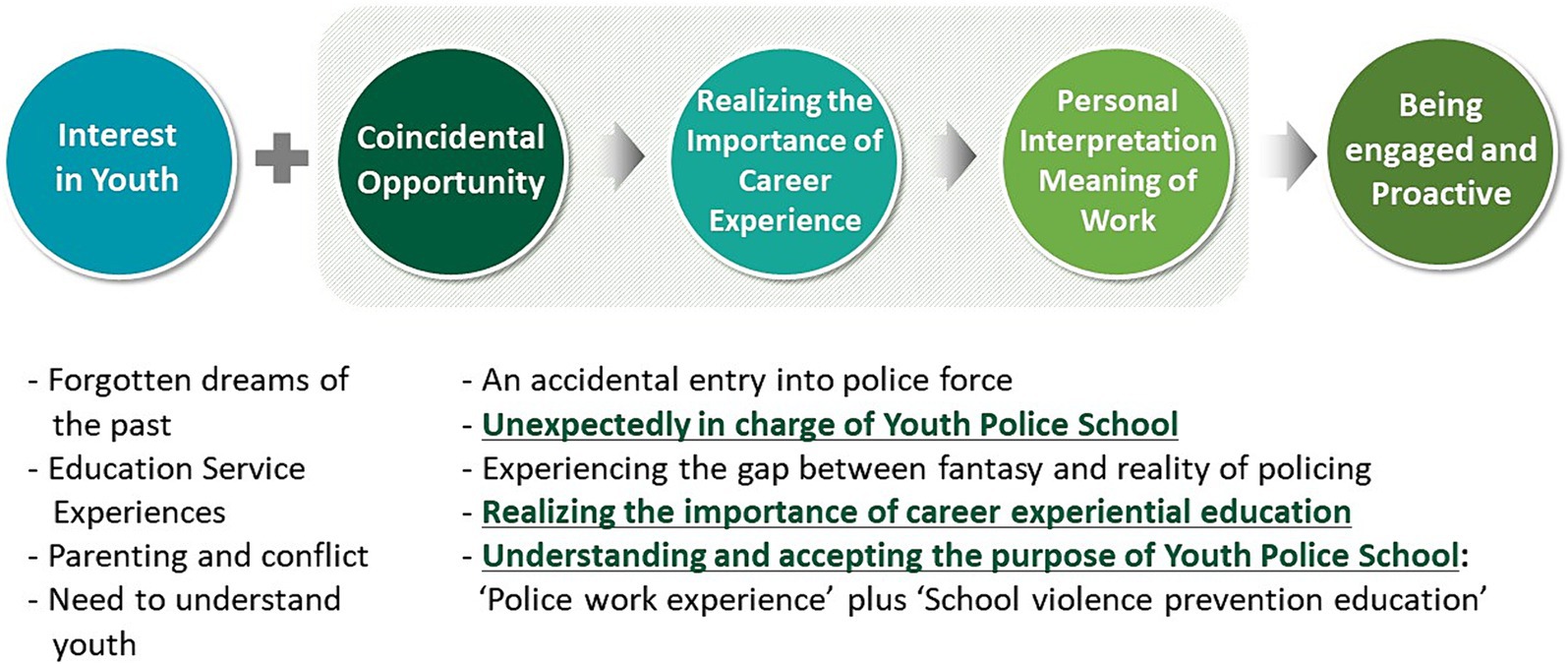

The majority of SPOs in this study entered the police service and were assigned to YPAs either through the directives of superiors or the departmental rotation system. These assignments involved them in the educational aspects of working with youth. According to the officers, there was a disparity between their “anticipated roles” in the policing profession and “the practical realities” they encountered. They viewed the YPA programs as part of their career-oriented experiential education. While some officers had an initial interest in youth education, a larger number reported challenges in engaging with this demographic. Nevertheless, most officers articulated a nuanced understanding of the YPA program’s objectives, describing it as an environment for “school bullying prevention education” and an opportunity for students to gain insight into the policing profession and cultivate their aspirations (Figure 2).

…the youth police academy is this project the Education Ministry and the Police Agency cooked up together. It's a school, right? So, it can't just focus on police stuff or just school stuff—it's got to do both. Personally, I'm not trained in giving advice or anything, and I'm no expert in teaching kids about avoiding trouble. There was a time I kept wondering if this was really the way to go. Now, when folks from the education department or other places drop by, I just say, "Hey, we've got this place thanks to a team-up between the education folks and the police. It's all about keeping violence out of schools and giving kids a peek into the police world, maybe even inspire them a bit" (Participant D).

4.1.2 Present: fulfilling roles and overcoming crisis

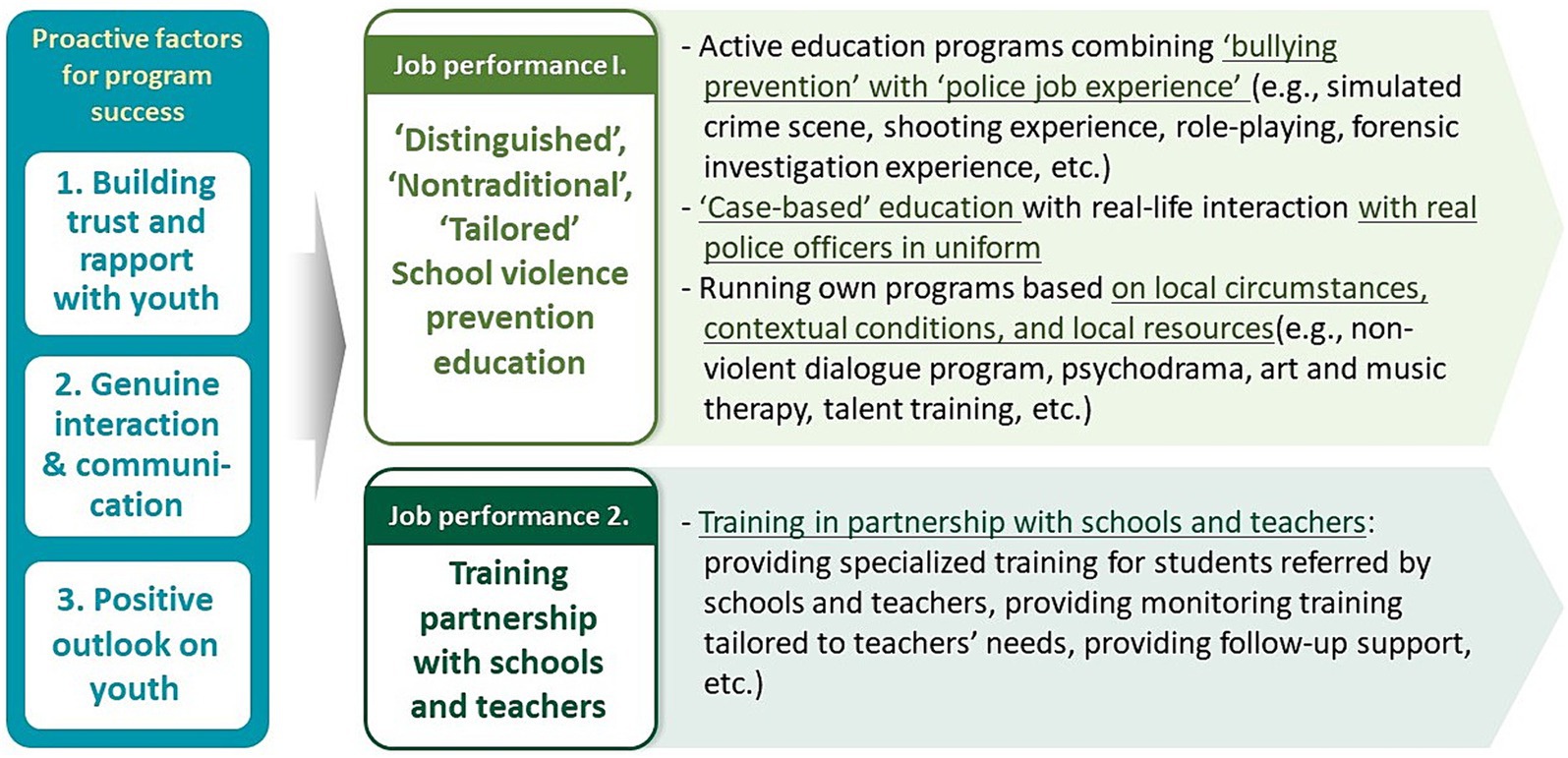

The experiences of SPOs participating in this study can be divided into two main scenarios: “Role Performance” and “Experiences of Crisis and Overcoming during Role Performance.” Regarding the former, officers, lacking an educational background, reported efforts to overcome the discomfort of interacting with youth. They observed that establishing “sincere interactions,” “communication,” and “a positive trust relationship with the youth” was essential for effective preventive approaches. Despite initial trial and error, facing problematic students with an attitude of “I cannot talk to you” proved unhelpful. They noted that without offering warmth and understanding akin to that of a counselor, teacher, or parent, students would not open up. Thus, building trust is seen as a prerequisite for the effective implementation of school bullying prevention programs (Figure 3).

The school bullying prevention education at Youth Police Academy is noted for its “unique, hands-on approach,” differentiating it from traditional, passive methods like mass lectures or video sessions commonly seen in schools. SPOs focus on showcasing realistic police procedures—everything from “the initial response to a report,” “Miranda rights notifications,” to demonstrating “the use of equipment like batons and tasers.” They also involve students in interactive activities such as role-playing the parts of perpetrator, victim, and bystander, and forensic science exercises like sketching crime scenes and fingerprinting. These methods are designed to enhance student engagement and offer a customized learning experience. Additionally, YPA uses its autonomy to tailor programs to the local context, utilizing community experts and resources for a more relevant and effective educational impact.

School bullying prevention education at YPA, led by SPOs, appears distinct from standard school programs at first glance. However, SPOs closely collaborate with schools and teachers, tailoring programs for students identified by teachers as needing special attention due to serious issues like school violence or non-compliance. Teachers often seek SPOs’ assistance for students with repetitive problematic behaviors. SPOs aim to offer customized education by coordinating with teachers beforehand and provide continuous support and monitoring after the program. This collaborative effort between YPA and schools demonstrates a complementary approach to prevention education, integrating specialized police-led initiatives with the educational curriculum for a more effective outcome.

The students who come to us aren't just any students; they've been involved in more serious incidents. They're the ones the schools can't handle anymore and send our way. This allows us to focus our education on similar cases…I think the police academy offers a unique setting for school bullying prevention education…Before planning a program, I talk with the teachers. If they say there's a lack of harmony among the students, we might use art therapy or something similar…And after the special education program, I always follow up with the student's homeroom teacher for feedback (Participant D).

In the professional identity analysis of SPOs, a critical discussion centers on “crisis” and “overcoming.” SPOs face challenges originating from both “extrinsic” factors—such as excessive workloads, lack of workplace recognition, insufficient supervisory interest, limited autonomy, and outdated infrastructure—and “intrinsic” factors related to their dual role in policing and education. This dual role often leads to role conflict and the difficulty of achieving visible outcomes in school bullying prevention, complicating their tasks further. Moreover, without a background in educational theory, SPOs struggle to build relationships with youth and address their issues effectively. Consequently, these challenges necessitate SPOs to articulate their own interpretations and significances of their roles amidst these crises.

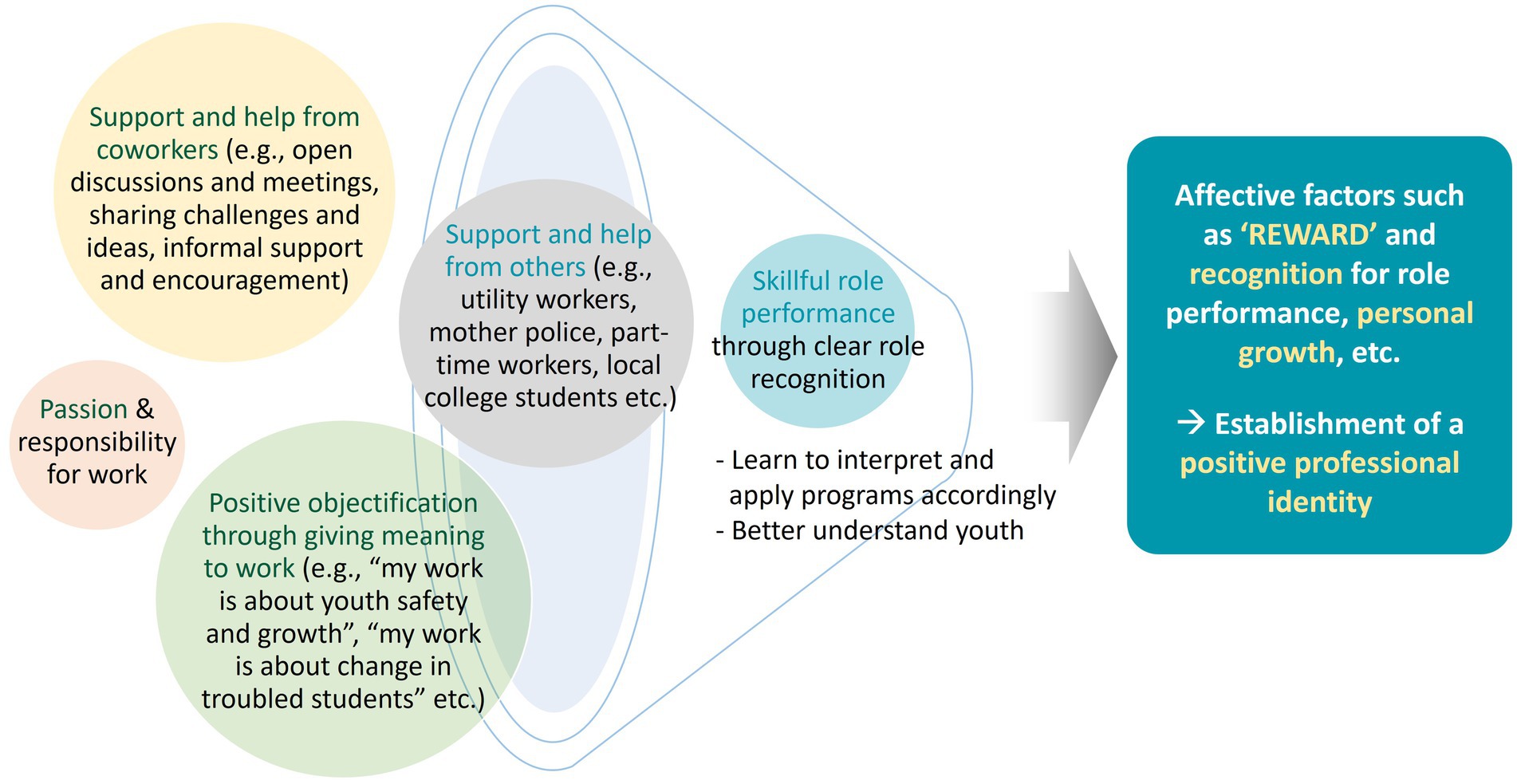

In addressing these crises, various factors contribute to a process that results in emotional rewards such as a sense of fulfillment, recognition of the importance of their role, personal growth, and ultimately, the development of a positive professional identity (Figure 4). Among the influential factors, “supportive colleagues” stand out as pivotal, with open discussions, sharing of challenges, and informal support serving as key motivators for SPOs to persist in their roles at Youth Police Academy. Additionally, “personal significance attributed to the job” plays a crucial role; recognizing the importance of contributing to the safety and development of youth and the value of assisting and inducing change in troubled students. This clear role awareness and attributed meaning not only enhance genuine understanding of and engagement with youth but also positively impact job performance.

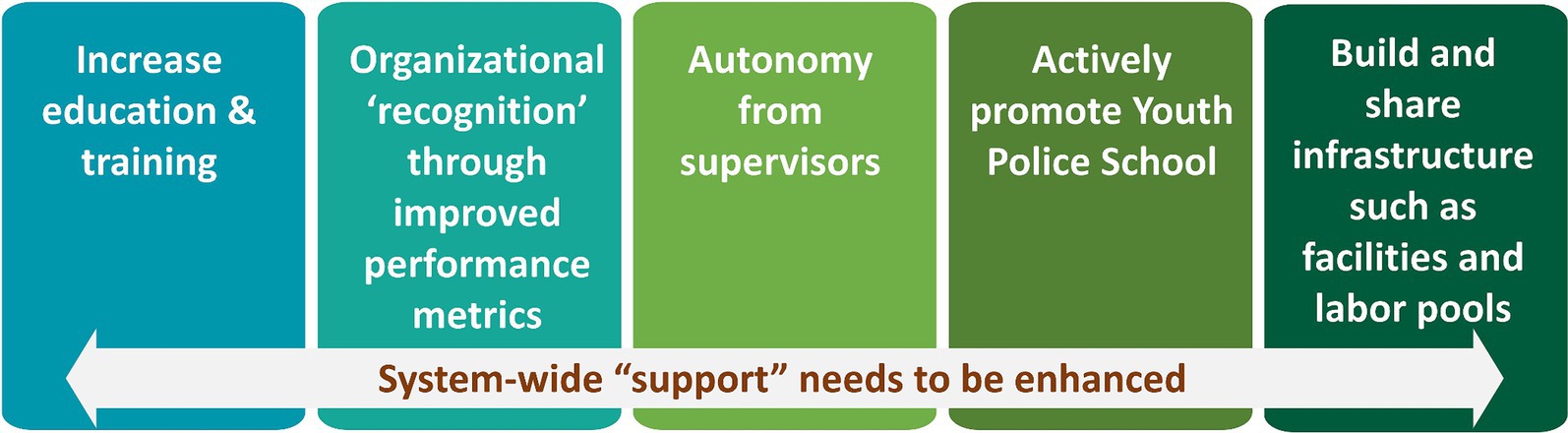

4.1.3 The future: notes on future improvement

Based on their experiences, the perspectives of those involved in the role execution and the future of the Youth Police Academy system can be summarized into five key areas, aligning with the demand for policy support for such programs (Figure 5). These areas also reflect the institutional requests necessary for the sustainable operation of SPOs and YPA policies. First, there is a need for sufficient training and development programs to reduce the time required for initial job adaptation and to acquire the know-how for operating customized programs tailored to the specific needs of different regions and students.

Secondly, consideration for recognition and reward within the police organization for those involved in the YPA operations are important. Relying solely on personal passion and fulfillment is insufficient given the significant gap between the “values pursued” and “realistic limitations,” potentially affecting the performance of SPO roles. Thirdly, to directly offer high-quality programs to students, SPOs need to explore and acquire necessary know-how and skills by trying various activities or visiting different institutions. This necessitates secured “autonomy” from superiors, emphasizing the need for SPOs to proactively engage in diverse experiences to enhance their program delivery.

Next, the importance of publicizing the YPA system is highlighted. It is essential to communicate that YPA is not a police station but a space for youth, where students can freely discuss concerns and victimization issues, understanding it as a place where they can seek assistance. Lastly, there is a call for infrastructure development, including facilities and staffing. While there is a common recognition of these improvement needs, the underlying motivation for continuing in this role lies in personal fulfillment and the intrinsic value assigned to the work itself. Therefore, while institutional support should address external aspects, more critically, efforts should be directed toward providing intrinsic rewards such as recognition of the work’s importance, ensuring SPOs can fully engage with their roles. Summarizing the analysis of career-identity scenarios for past, present, and future can be seen in Figure 6.

“…space is limited, facilities are outdated, and instructors are hard to find. These are the common difficulties, or maybe there’s not enough attention from the command,…and about the including the work and performance of the Youth Police Academy in the evaluation metrics. I emphasized this a lot in the beginning, but I think I’m enjoying it so much now that my deputy looks at me and says I look like I’ve put my neck on the line for this” (Participant D).

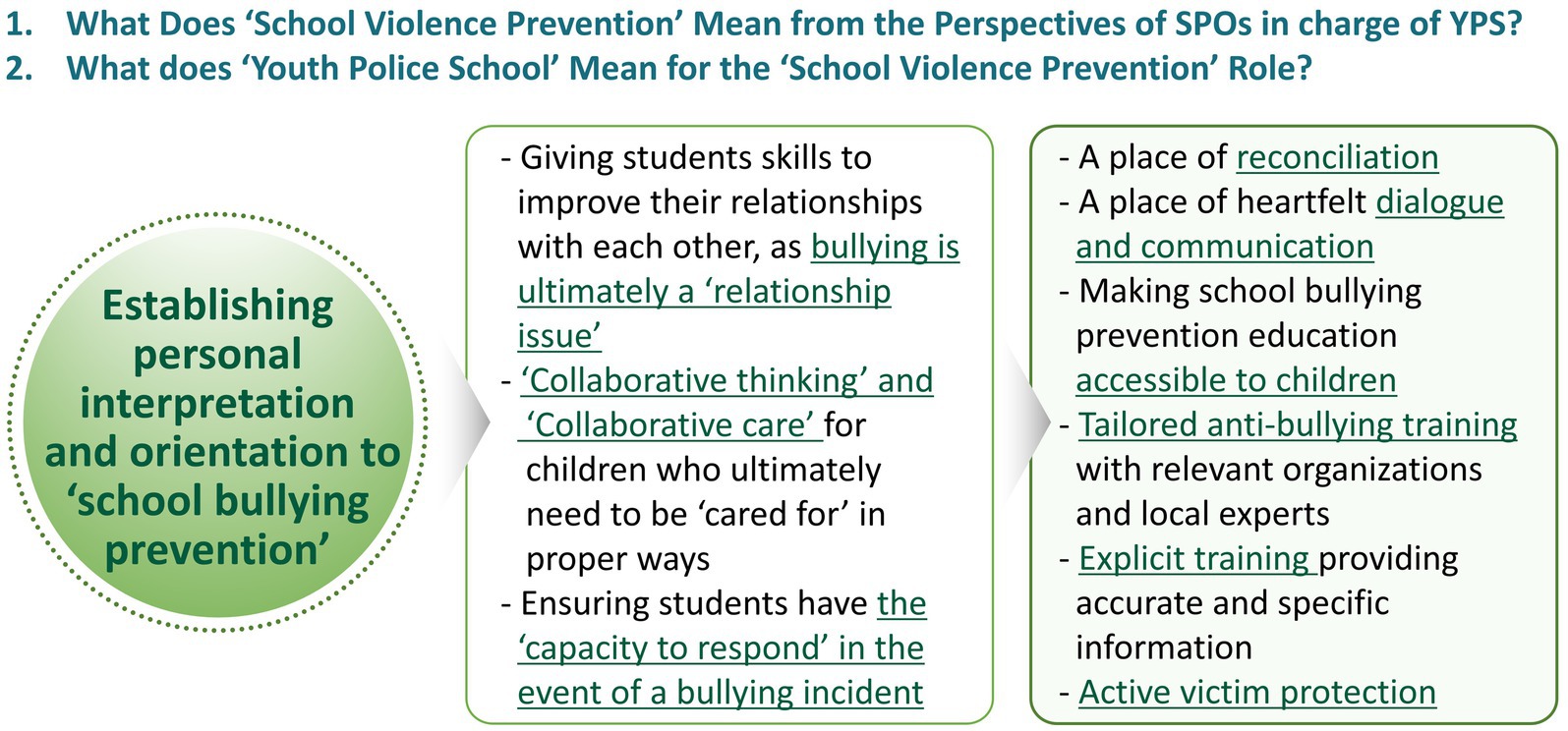

4.2 The relevance of ‘school bullying prevention’ through the narratives of SPOs

4.2.1 What does school bullying prevention convey from the perspectives of SPOs in YPA?

The exploration of the School Police Officers’ (SPOs) professional identity scenarios provides insight into their subjective perceptions of what the task of “preventing school bullying” should entail and what “school bullying prevention” conveys. From the perspective of SPOs overseeing Youth Police Academy, the interpretation of “school bullying prevention” aligns closely with their primary objective of role fulfillment. According to the findings of this study, this can be broadly categorized into three key areas. First, school bullying is fundamentally seen as an issue of “relationships” among students. The focus is on how to equip students with the skills to “resolve” relationship problems when they arise or how to proceed when resolution is not achievable. This highlights the importance of improving “inter-student relationships” is central to preventing school bullying and emphasizes the need to instill relational skills in students.

It is all about the relationship between students, so it’s a matter of how do you break that down, or do you give them the skills to break it down, and then what do you do when it doesn’t work, and I think the key to preventing bullying is teaching those skills and making sure they learn them (Participant A).

Secondly, school bullying prevention is viewed as a process of “collaborative concern” and “collaborative care,” where the standpoint of the youth is considered, and their thoughts and worries are addressed together. This perspective arises from recognizing the low effectiveness of traditional, formal lecture-based or uniform video-based prevention education. The SPOs involved in this study emphasized an approachable method, particularly for students exhibiting severe problematic behaviors or situations, suggesting such students might have greater deficits or a need for more attention. This approach highlights viewing “growing children” with a perspective focused on their issues, listening to their “needs,” and engaging in “shared problem-solving,” embodying the role of socially responsible adults.

"…we need to constantly think about what the biggest issues for teenagers are right now. We should try to adapt educational programs to their level, and we need to work together. Through investigations, we can learn about the kids' home environments and understand what they're most worried about. By identifying these concerns, we can provide education that meets their needs. Our job is to help each troubled kid make a change. Whether they've caused trouble or not, they are part of our society and our future, so the role of adults is really important. I believe we all need to work together" (Participant C).

Lastly, the ultimate goal of school bullying prevention education is seen as equipping students with the capabilities to handle incidents of school bullying should they arise. This involves fostering actionable coping behaviors in the face of school bullying situations, emphasizing the importance of knowing and understanding how to respond, including how to deal with the aftermath of being victimized. This perspective underscores the significance of preparedness and response as the essence and direction of school bullying prevention education.

I think prevention is all about making sure that when they do encounter bullying, they have ‘coping behaviors’… Anyone can be victimized unwillingly, if they are, they need to be able to think about what to do next…and that’s why when I teach bullying prevention, I also emphasize coping behaviors” (Participant D).

4.2.2 What does “youth police academy” represent for the role of “school bullying prevention?”

Following the exploration above, the primary research questions this study aims to address concern the role that YPA can play in executing the “school bullying prevention” tasks outlined, and the significance these programs hold in achieving such objectives. According to the findings of this study, this can be categorized into five key areas, as follows:

Firstly, intra-student conflicts are inevitable and not all necessitate categorization as school bullying. When conflicts arise outside the purview of school bullying, there is a consensus that students require opportunities and spaces for “reconciliation” rather than formal “reports” or “complaints.” Under the current protocols for handling school bullying, initiating a report can lead to “separation measures” for involved students, complicating the school’s role as a mediator until official resolutions are determined by the School Violence Committee. This situation highlights the necessity for mechanisms within the educational framework that prioritize reconciliation over punitive actions, allowing schools to facilitate understanding and resolution among students more effectively.

I offer a youth police academy as a 'place of reconciliation’…Because there are some students who might not feel comfortable going to the police station, and there are some students who might not feel comfortable going to school because they might get in trouble if the school finds out about it. It’s not a police station, it’s not a school, so it’s a really good space (Participant B).

Secondly, school bullying prevention education should be regarded as part of the broader educational effort, necessitating approaches that align with students’ perspectives. The SPOs involved in this study recognized that employing role-plays or psychodramas, which focus on relatable, real-life issues, provides an effective experiential and case-based educational approach. Through these experiences, students who have been aggressors learn the importance of apology, victims understand the value of seeking help rather than fearing retaliation, and bystanders realize the significance of taking active protective measures. This experiential prevention education underscores the importance of YPA as facilities where such meaningful educational activities can take place.

“Through some form of psychodrama or role-playing, be a bully, a victim, or a bystander… talking and discussing things most troubling to us.” So I think that's the most effective way to approach bullying prevention education, is to make it something that I can say and feel and do, not just listen to it, because kids don't listen to it with their ears (Participant C).

Thirdly, there is an awareness of the role of YPA as hubs for school bullying prevention education, grounded in collaboration with relevant institutions and local experts. This role includes connecting with families, schools, and community resources, and facilitating access to counselors or social welfare services based on students’ needs. This perspective is based on the insight that student issues are not isolated to individuals but often stem from a lack of communication and interaction with parents at home or a deficiency in social support. Consequently, some YPA focus particularly on parent education and family engagement programs within their array of offerings, recognizing the complex roots of student issues and the broad spectrum of support required to address them effectively.

“I’m experiencing bullying”, then I put them in touch with the school’s SPO, or I put them in touch with the counselor and see what support they need… (Participant B).

I think if you have to educate parents in the category of school bullying, you could use the police academy or something like that. I think it would be good if parent education or family experiences could be included in the police academy program, so that parents and children can have time together (Participant C).

Fourthly, a fundamental approach to school bullying prevention education lies in ‘explicit education’, which provides precise and detailed information about the types of school bullying, specific reporting, and protection methods. There is a strong belief that SPOs are well-suited to fulfill this role. Additionally, there is a recognition that YPA should serve as a “safe haven” which victims can feel comfortable reporting incidents and understand their rights to protection. This approach also encompasses educating students on how to handle potential dangers and harm that could occur on school premises, emphasizing that imparting knowledge on these topics constitutes a form of preventive education.

To hear specific ways to report, specific ways to protect yourself, to think, “Oh, I can trust this place, I can trust the police, they can help me!”…Awareness that it is okay to report and that they will be protected.…I think that prevention education should let them know that there's a place where they can talk about it, where they're safe, where they're not going to be retaliated against for reporting it…"You're safe here,"…"It's okay to report it, it's not wrong to report it,"…"You're protected here. Prevention education, "You're safe here, you're protected here. You're protected under the law, you're protected by the police" (Participant B).

Lastly, one of the significant roles that institutions like YPA can play in the realm of school bullying prevention and response is ‘active victim protection’. This encompasses not only preventing further instances of school bullying or secondary victimization but also aiding in the recovery of victims’ damages. This recognition extends to the understanding that effective school bullying prevention education involves not just verbal assurances of protection but also the actual fulfillment of these promises by SPOs, embodying their role as protectors and supporters in tangible ways. The relevance of ‘School Bullying Prevention’ through the narratives of SPOs is summarized in Figure 7.

It’s all about the victims, it’s all about restoring the victim, and we’re the only organization that goes out and meets them… I think if you make a promise, you have to keep it. I think it would be good if there was some effort to create an atmosphere or monitor it so that there is no retaliation. What's the point of making a promise if you don't keep it (Participant B).

5 Discussion

In South Korea, the School Police Officer system was established in 2011 after a tragic incident of a middle school student’s suicide due to school bullying, and the role of “dedicated school bullying investigator” was introduced to enforce a stricter approach to handling school bullying. Addressing school bullying, a persistently challenging issue, has lacked clear answers regarding the effective design and goals of prevention education (Hong, 2023). This study delves into the professional experiences and perspectives of SPOs, whose main duty is “preventing school bullying,” to uncover the relevance of “school bullying prevention” and explore the role of YPAs in school bullying prevention through qualitative analysis, providing key findings and implications.

The main findings indicate that SPOs perceive school bullying prevention as fundamentally centered on improving student relationships and teaching conflict resolution skills. They advocate for a collaborative care approach, addressing students’ concerns through approachable methods rather than traditional lectures. The YPA plays a crucial role by providing reconciliation spaces, engaging students with experiential education like role-plays, and serving as hubs for collaboration with families and community resources. This perspective of SPOs is, to some extent, reflected not only in the well-known Olweus Bullying Prevention Program in Norway (Olweus and Limber, 2010), but also in the Friendly Schools Project in Australia (Cross et al., 2004, 2018) and the Sheffield Project in the United Kingdom (Smith et al., 2004). Additionally, YPA offers explicit education on bullying types and reporting methods while actively protecting victims and ensuring follow-through on promises of safety and support. These insights underline the significance of building trust and sincere interactions with students, recognizing the limitations of traditional educational methods, and the need for a comprehensive, supportive framework involving collaboration between schools, families, and community resources.

Based on the findings above, the following implications can be drawn and discussed.

5.1 What “Youth” need

Youth Police Academy, created by a partnership between the Ministry of Education and the National Police Agency, fill a unique niche between schools and police stations. These schools aim to do more than just career exploration; they are tasked with providing education on preventing school bullying, a new role for police officers. This dual purpose might lead to role conflicts since officers typically do not have experience in teaching youth. Nevertheless, they work to fulfill this role, viewing Youth Police Schools as venues where students learn about both school bullying prevention and the policing profession. According to Hoyle (1995), five criteria for defining a profession could be outlined as follows: social function, specialized knowledge, autonomy, professional values, and professional organization. In this context, both SPOs and teachers share the critical social function of “preventing school bullying.” This role not only aims to induce positive changes in individual students, but also serves the broader public interest. This comparison highlights that the pivotal issue is not “who” should undertake this responsibility, but rather that the core of school bullying prevention education should be the “students,” who are the subjects rather than the agents of such educational efforts. Consequently, it underscores that school bullying prevention education should be fundamentally student-centered.

5.2 “Collaboration” based on genuine concern for youth

Assuming that the focus of preventive education discussions is on “students,” the approach to preventive education must fundamentally stem from “genuine concern for youth.” This concern, however, should not remain a matter of individual serendipitous realization but needs to translate into “collaborative efforts.” Assigned SPOs often find themselves in this role by chance, realizing that the nature of their work significantly differs from traditional police duties. These officers frequently encounter unexpected fulfillment and pride through their interactions with specific students. Though “this serendipitous engagement” has shaped their professional identity up to the present, this understanding that “students” and “a genuine concern for youth” should be at the center of all the efforts highlights the necessity of reducing serendipity through coordinated efforts, especially among the Ministry of Education, the Police Agency, educational offices, frontline schools, and family (Cross et al., 2018). Therefore, the role of the institutional frameworks should be to minimize the elements of chance faced by individual SPOs by fostering consistent and socially integrated approaches to school bullying prevention education (Farrington and Ttofi, 2009; Ministry of Education, 2020).

5.3 Institutional efforts that need to be “proactive”

A key conclusion and implication drawn from this study is answering what the ultimate form of school bullying prevention education should look like. The approach observed in YPAs distinguishes itself by being “proactive.” The YPA currently functions as a standalone facility providing school bullying prevention education and police career experience opportunities for youth who visit the site. However, considering the circumstances and challenges faced by many school bullying victims who may find it difficult to seek out such services, it is insufficient to merely wait for these students to come to the facility. As highlighted by the participating SPOs in this study, there is a need for a more aggressive or proactive approach, such as “going directly to nearby areas, informing them that we are here to help and what kind of assistance we can provide.” Furthermore, by offering “customized” assistance through collaboration with various agencies and experts, it acts as a hub for youth protection. This proactive stance sets it apart from traditional methods, emphasizing direct engagement and tailored support, aligning with the current government’s goal to enhance personalized support for victims (Ministry of Education, 2020). Ultimately, the meaning of “proactivity” in this context is that school bullying prevention and response are not separate dimensions but are closely interconnected. Proactive response measures are essentially proactive prevention, and active victim protection is a crucial component of school bullying prevention.

5.4 What “Youth Protection Systems” provide

Based on the aforementioned discussions, there emerges a critical need to move away from a provider-centric perspective and focus instead on collaborative and proactive support addressing the needs of youth. Notably, South Korea ranks lowest in the OECD in terms of child and adolescent life satisfaction, with suicide being the leading cause of death among teenagers (Statistics Korea, 2022; Chungcheong Today, 2024). Conflicts with peers, lack of support, school bullying, social exclusion, depression, and academic stress in a highly competitive environment have been identified as a major causes of youth suicide in Korean context. Therefore, establishing a comprehensive support system for youth protection is urgently needed (Park et al., 2010; Health Chosun, 2023). In particular, discussions on school bullying, a major cause of youth suicide, reached a peak in 2023, leading to stricter measures against perpetrators of school bullying (Choi and Hong, 2023).

Various social conflicts, such as “the Day of Public Education Suspension” and the controversy over the repeal of the Student Rights Ordinance, brought school conflicts to the forefront of societal issues. Additionally, discussions on establishing rapid response systems like ‘SOS Lifeline’ and “Youth Hotline 1388” highlighted the need for societal awareness and collaborative solutions to youth problems (Hanshin University Newspaper, 2023). However, despite the increasing social and academic attention to school bullying, and previous policy efforts suggesting the establishment of a robust youth safety net system, the intensification of judicial intervention in schools and the inadequacy of conflict resolution capabilities became more prominent than ever. As school bullying is now recognized as a societal problem extending beyond school boundaries (Hong, 2023), a key agenda item for the Presidential Commission on National integration in the socio-cultural sector in 2024, has been “conflict resolution within schools.” As noted by one SPO participating in this study, it is easy to assume that a system and safety net are in place, but the reality, according to field worker, seems quite different and cannot be ignored.

Taking into account all the previous discussions, the aforementioned considerations ultimately lead to a discourse on the transformation of paradigms in the prevention and response to school bullying. This discourse advocates for a shift from “reactive measures” to “proactive prevention,” emphasizing the necessity of “educational resolutions within schools” rather than judicial interventions. It further underscores the importance of establishing “evidence-based systems for collaborative intervention,” rather than relying on the capabilities of individual teachers or SPOs to address incidents of bullying. Within this evolving paradigm, the roles of SPOs and the very concept of school bullying prevention are subject to potential redefinition and require reassessment to align with these new directions.

5.5 Limitations and suggestions for future research

Our methodology contains fundamental limitations. Researchers extensively engaged in reflexivity processes during sampling, interviews, data collection, and the analysis and interpretation of the data. We pre-determined the sampling criteria and disclosed questionnaires and quotes to ensure credibility and validity (Mergel et al., 2019). However, there are still possibilities of the authors’ influences and biases intervening in qualitative research. Nevertheless, as narrative inquiry is designed to understand experiences rather than create singular representations (Clandinin and Rosiek, 2019), this study provides meaningful potential directions and perspectives without overly generalizing its findings.

There may be differences in the relevance of school bullying prevention program due to variations in the SPO system, school environment, and education policies between Korea and other countries. Therefore, a thorough analysis and comparative study on national SPO system, school environment, and school bullying prevention policies are required. Furthermore, there is a pressing need to explore “system-level evidence-based recommendations” that can be practically applied within institutional framework, such as curriculum design (Cross et al., 2004, 187). Especially in Korean context, in which the response systems to school bullying have a legalistic nature, leading to controversies over the judicialization of school environments (Hong and Choi, 2023). Therefore, there is a need for a comprehensive exploration of educational solutions to address these issues effectively.

Author contributions

MH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2021S1A5C2A03088726).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants of this study for providing their valuable time and informative responses.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bowllan, N. M. (2010). The role of the clinical nurse specialist: Transprofessional collaboration in the implementation of a school-wide bullying prevention program. Clin. Nurse Spec. 24:103. doi: 10.1097/01.NUR.0000348960.97366.6e

Choi, J., and Hong, M. Y. (2023). Exploring the perceptions of the policy responses to perpetrators of school violence and policy directions. Korean J. Youth Stud. 30, 125–155. doi: 10.21509/KJYS.2023.12.30.12.125

Chungcheong Today (2024). Our Future': Chungnam education as a sanctuary for the mental health of youth. Available online at: https://www.cctoday.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=2196505

Clandinin, D. J., and Connelly, F. M. (2004). Narrative Inquiry: Experience and Story in Qualitative Research. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Clandinin, D. J., and Rosiek, J. (2019). “Mapping a landscape of narrative inquiry: borderland spaces and tensions” in Journeys in Narrative Inquiry (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge), 228–264.

Cross, D., Hall, M., Hamilton, G., Pintabona, Y., and Erceg, E. (2004). “Australia: the friendly schools project” in Bullying in Schools: How Successful Can Interventions Be? eds. P. K. Smith, D. Pepler, and K. Rigby (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 187–210.

Cross, D., Shaw, T., Epstein, M., Pearce, N., Barnes, A., Burns, S., et al. (2018). Impact of the friendly schools whole-school intervention on transition to secondary school and adolescent bullying behaviour. Eur. J. Educ. 53, 495–513. doi: 10.1111/ejed.12307

Del Corso, J., and Rehfuss, M. C. (2011). The role of narrative in career construction theory. J. Vocat. Behav. 79, 334–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2011.04.003

Farrington, D. P. (1993). “Understanding and preventing bullying” in Crime and Justice. ed. M. Tonry , vol. 17 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 381–458.

Farrington, D. P., and Ttofi, M. M. (2009). School-based programs to reduce bullying and victimization. Campbell Syst. Rev. 5, i–148. doi: 10.4073/csr.2009.6

Gaffney, H., Farrington, D. P., and Ttofi, M. M. (2019a). Examining the effectiveness of school-bullying intervention programs globally: a meta-analysis. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 1, 14–31. doi: 10.1007/s42380-019-0007-4

Gaffney, H., Ttofi, M. M., and Farrington, D. P. (2019b). Evaluating the effectiveness of school-bullying prevention programs: an updated meta-analytical review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 45, 111–133. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2018.07.001

Han, Y. K., Shin, T. S., Song, A., Lee, Y., and Ahn, H. J. (2022). Report on the results of the 2021 Youth Police Academy Support Project. Ewha Womans University Institute for School Violence Prevention.

Han, Y. K., Song, A., and Um, S. J. (2021). Implementation and evaluation of the youth police academy school bullying prevention program in South Korea. Int. J. Educ. Res. 110:101881. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2021.101881

Hanshin University Newspaper (2023). [Issue 600] The unabated youth suicide rate and South Korea's uncertain future. Available online at https://him.hs.ac.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=67

Health Chosun (2023). Increasing youth suicide rates. What drives them to death? Available online at: https://health.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2023/01/04/2023010402192.html

Hikmat, R., Suryani, S., Yosep, I., Hernawaty, T., Widianti, E., Rafiyah, I., et al. (2024). School program integrated with nursing intervention for reducing bullying behavior among students: a narrative review. Environ. Soc. Psychol. 9, 1–10. doi: 10.54517/esp.v9i3.2109

Hong, M. Y. (2023). Designing and implementing a school violence policy model for unit schools based on the restorative whole-school approach (RWSA): an academic examination. Educ. Rev. 52, 66–102. doi: 10.23119/er.2023..52.66

Hong, M. Y., and Choi, J. (2023). Discourse analysis: unpacking ‘zero-tolerance’ in global school violence policies. CNU J. Educ. Stud. 44, 69–110. doi: 10.18612/cnujes.2023.44.3.69

Hong, M. Y., Han, Y. K., Chang, W. K., and Kim, H. Y. (2023). Exploring the changes in school violence tendency in Korea during COVID-19 period: centered on victim experiences. J. Res. Educ. 36, 59–90. doi: 10.24299/kier.2023.363.59

Hoyle, E. (1995). “Changing concepts of a profession” in Managing Teachers as professionals in Schools. eds. H. Busher and R. Saran (London: Kogan Page).

Joe, H. S. (2016). Study on the countermeasures of the police for the prevention of school violence. Kor. Assoc. Police Welfare Stud. 4, 57–76.

Kennedy, R. S. (2020). Gender differences in outcomes of bullying prevention programs: a meta-analysis. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 119:105506. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105506

Kim, S. H. (2019). An analysis of research trends in Korean school police researches. J. Kor. Soc. Priv. Secur. 183, 29–54.

Kim, S. S. (2020). A study on the influence of domestic factors on the violent behavior of school violence—based on the police's countermeasures. Kor. Nat. Secur. Public Safe. Assoc. 11, 143–166. doi: 10.36847/knspsa.2020.11.6

Kim, B. S., and Choo, B. J. (2017). A study on the improvement of police system for school police officer-on Delphi technique of SPO in Daegu Kyungbuk region. Kor. Assoc. Public Saf. Crim. Justice 26, 9–34. doi: 10.21181/KJPC.2017.26.3.9

Kim, S., and Hwang, J. S. (2018). Analysis of actual condition and issues of school police officer system operation. Polit. Educ. 25, 1–20. doi: 10.52183/KSPE.2018.25.4.1

Lee, Y. H., Han, Y. K., and Chu, J. (2021). An analysis of the effectiveness of youth police academy for experiential school violence program. J. Educ. Cult. 27, 57–76.

Lee, E. S., and Kang, Y. T. (2011). A qualitative study of Christian alternative school graduates on their perceptions of the educational performance. Kor. Soc Study Christ Religi Educ 26, 481–515.

Lee, C. M., and Park, H. J. (2020). Active policing to solve school violence. J. Hum. Rights Law Educ. 13, 113–142. doi: 10.35881/HLER.2020.13.3.5

Mergel, I., Edelmann, N., and Haug, N. (2019). Defining digital transformation: results from expert interviews. Gov. Inf. Q. 36:101385. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2019.06.002

Ministry of Education (2013). Joint effort of related ministries: Announcement of 'Field-centered school bullying prevention strategy. Available at: https://www.moe.go.kr/boardCnts/viewRenew.do?boardID=294&boardSeq=49444&lev=0&searchType=null&statusYN=C&page=1&s=moe&m=020402&opType=N (Accessed May 29, 2024).

Ministry of Education (2020). The 4th basic plan for school bullying prevention and countermeasures (2020–2024). Available online at: https://www.moe.go.kr/boardCnts/viewRenew.do?boardID=316&lev=0&statusYN=W&s=moe&m=0302&opType=N&boardSeq=83086 (Accessed May 29, 2024).

Ministry of Education (2022). 2022–2021 survey on the actual state of school violence. Available online at: https://www.moe.go.kr/boardCnts/viewRenew.do?boardID=294&boardSeq=92500&lev=0&searchType=null&statusYN=W&page=1&s=moe&m=020402&opType=N (Accessed May 29, 2024).

National Police Agency (2021). Police encyclopedia. Available online at: https://www.police.go.kr/www/open/publice/publice06_2021.jsp (Accessed May 29, 2024).

Olweus, D. (1992). “Bullying among school children: intervention and prevention” in Aggression and Violence Throughout the Lifespan. eds. R. D. Peters, R. J. McMahon, and V. L. Quinsey (London: Sage), 100–125.

Olweus, D., and Limber, S. P. (2010). Bullying in school: evaluation and dissemination of the Olweus bullying prevention program. Am. J. Orthop. 80, 124–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01015.x

Park, S. W. (2019). A study on applying school violence prevention education by analyzing excellent cases of school violence prevention in domestic and foreign schools. J. Learn. Center. Curricul. Instruct. 19, 653–676. doi: 10.22251/jlcci.2019.19.13.653

Park, J., Park, C., Seo, H., and Yeom, Y. (2010). Collection of Korean child well-being index and its international comparison with other OECD countries. Kor. J. Sociol. 44, 121–154.

Salmivalli, C., and Poskiparta, E. (2012). Making bullying prevention a priority in Finnish schools: the KiVa antibullying program. New Dir. Youth Dev. 2012, 41–53. doi: 10.1002/yd.20006

Savickas, M. L. (2012). Life design: a paradigm for career intervention in the 21st century. J. Couns. Dev. 90, 13–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-6676.2012.00002.x

Savickas, M. L., Nota, L., Rossier, J., Dauwalder, J. P., Duarte, M. E., Guichard, J., et al. (2009). Life designing: a paradigm for career construction in the 21st century. J. Vocat. Behav. 75, 239–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2009.04.004

Shin, K. W., and Kim, J. O. (2016). A study on the role of police for school violence prevention. J. Public Policy Stud. 32, 1–17.

Smith, P. K., Sharp, S., Eslea, M., and Thompson, D. (2004). “England: the Sheffield project” in Bullying in Schools: How Successful Can Interventions Be? eds. P. K. Smith, D. Pepler, and K. Rigby (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press), 187–210.

Statistics Korea (2022). Quality of Life of Children and Adolescents 2022. Available online at: https://kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10301150000&bid=246&act=view&list_no=422751 (Accessed June 8, 2024).

The Blue Tree Foundation (2023). Announcement of Nationwide Survey and Measures on School Bullying and Cyberbullying in 2023. Available at: https://btf.or.kr/board/board_bagic/board_list.asp?scrID=0000000106&pageNum=2&subNum=2&ssubNum=1 (Accessed May 29, 2024).

Ttofi, M. M., and Farrington, D. P. (2012). Bullying prevention programs: the importance of peer intervention, disciplinary methods and age variations. J. Exp. Criminol. 8, 443–462. doi: 10.1007/s11292-012-9161-0

Appendix

Appendix A: Interview Questionnaire and Objectives

Part I: Career Identity

1. Please tell us about your background and what led you to become a police officer.

2. What motivated you to become an officer in charge of the Youth Police Academy (YPA)?

3. Describe your early experiences related to your YPA duties. (Consider your experiences related to your work, relationships with fellow officers, supervisors, students, and any systemic issues within the program.)

4. How did you address the challenges you faced in your role?

5. When did you feel that you had become familiar with your YPA duties or developed a sense of expertise?

6. Describe your mid-career experiences in YPA. (Consider changes in your attitude, goals, relationships with colleagues and supervisors, interactions with students, and how you addressed systemic issues.)

7. When did you put the most effort into revitalizing the YPA program and building relationships with students?

8. Do you have any memorable and meaningful experiences from your time as a YPA officer?

9. When did you find your YPA duties most challenging, and how did you cope with these challenges?

10. What support do you think is necessary for the effective operation of the YPA?

Part II: Relevance of the school bullying prevention program and the role of YPA in preventing school bullying

11. What do you think is the primary purpose of the Youth Police Academy?

12. What is your approach and objective in conducting school bullying prevention program?

13. What are the most challenging aspects of implementing school bullying prevention program?

14. How do you evaluate the role of the Youth Police Academy in school bullying prevention, and what role should it play?

Conclusion

Do you have any additional comments regarding this study and the interview?

Objectives of each question (Connection with research questions).

Keywords: Youth Police Academy, school police officer, school bullying, school bullying prevention, student behavior policy

Citation: Hong MY and Goo J (2024) The significance of school bullying prevention program: a narrative inquiry from the perspective of a school police officer at a Youth Police Academy in Korea. Front. Educ. 9:1408275. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1408275

Edited by:

Mahwish Kamran, Iqra University, PakistanReviewed by:

María-Mercedes Yeomans-Cabrera, Universidad de las Américas, ChileAna Patrícia Almeida, Universidade Aberta, Portugal

Ken Brien, University of New Brunswick, Canada

Copyright © 2024 Hong and Goo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mi Yung Hong, bWl5b3VuZ2huZ0BnbWFpbC5jb20=

Mi Yung Hong

Mi Yung Hong Jiyeon Goo

Jiyeon Goo