- Department of Educational Science, Schwyz University of Teacher Education, Goldau, Switzerland

This conceptual article proposes a contextualized view of teachers’ professional ethos in the area of school bullying in general and regarding bias-based bullying in particular. I argue that teachers need a contextualized or embedded professional ethos to successfully address bias-based bullying and promote positive social relationships among students. Three objectives relating to the improvement of educational practices in addressing school bullying, particularly bias-based bullying, are pursued. First, with a view to professionalizing teachers, this article attempts to make tangible the abstract concept of professional ethos, a concept largely neglected in contemporary teacher education. Secondly, the contribution synthesizes current knowledge on the phenomenon of bias-based bullying in schools and the role of teachers in the bullying dynamics, highlighting the link between empirical findings and pedagogical practice. Thirdly, I propose a contextualized model as a guide how teachers’ professional ethos in the area of bias-based bullying can be developed and fostered.

1 Introduction

“My job is teaching, not parenting.” “We all had to go through this.” “A teacher cannot see everything that is going on.” “Actually, I can understand why they all pick on him. He is getting on my nerves, too.” “Well, she does have more body fat than the other girls in the class.” These are a few of the remarks primary and secondary school teachers attending my further education courses on bullying prevention have made, usually during the first few hours of coursework. As they learn more about the phenomenon, its social dynamics and contextual embeddedness as well as the role of the adults in the system, particularly teachers, their viewpoints start to shift, sometimes dramatically. Teachers start to realize that—through their very role, position, sphere of influence, and behaviour—they become “part of the game” and contribute to facilitating or preventing bullying. They begin to voice their concern that the social and organizational school environment play an important role in providing a culture and climate that is more or less conducive to bullying, thereby restraining the outreach and impact they as individual teachers can have. Many of them start to critically reflect on local school rules and power dynamics and perceive a need to promote a positive school culture and climate actively and collaboratively. Finally, some take up actual collaboration to bring about change.

How do such changes come about? We can expect that learning about the specific characteristics of the bullying dynamics, its contextual embeddedness as well as the consequences bullying has for all involved, contributed to teachers’ understanding and attitude change. Implementing the prevention programme (an extended version of BeProx; original version by Alsaker and Valkanover, 2001) also led them to change some of their teaching practices. Thus, to put it simplistically, it takes some knowledge gain, some change of attitude and teaching practices for teachers to address bullying successfully. However, how are these levels of teacher professional competence reached? How can they be interlinked in such a way as to ensure they align and do not contradict each other, as is the case, e.g., when teachers implement programme elements in a way that reflects pro-bullying rather than anti-bullying attitudes or when a teacher knows bullying is wrong but does not feel responsible to address it? What does it take for teachers to embody holistically this stance of taking bullying seriously, address it, but also pro-actively work towards promoting positive social relationships in their classrooms and schools? These and other questions led me to the concept of teacher professional ethos. In this position paper I propose a model of a contextualized view of teachers’ professional ethos in the area of school bullying in general and regarding bias-based bullying in particular. I argue that teachers need a contextualized or embedded professional ethos to successfully address bias-based bullying and promote positive social relationships among students (Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, 2021, 2024).

The basic tenets of the model proposed here are: (a) It takes more than pertinent knowledge, attitudes, and teaching methods for teachers to successfully tackle bullying, particularly bias-based bullying, this “more” pertaining to teachers’ professional ethos; (b) teachers’ professional ethos does not originate within themselves, only, nor can it be promoted by making it the individual teachers’ sole responsibility; and (c) teachers’ professional ethos needs to be conceptualized in relation to a specific domain rather than globally. A domain-specific conceptualization makes it possible to consider facets pertaining to that domain which cannot be fully recognized on a merely global level (cf. Latzko et al., 2018). The respective domain is that of social relationships at school, with bullying representing a specific area therein.

2 The role of teachers in the bullying ecology

Bullying at school is a targeted, long-standing negative behaviour against a less powerful person in a group (Olweus, 1993). It is increasingly seen as immoral in the sense that another person’s welfare is systematically harmed (Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger and Perren, 2022) and their rights are violated (Cornell and Limber, 2015; Ziemes and Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, 2019). Bias-based bullying—as one particular form—focuses on a person’s group membership as based on specific personal characteristics like ethnicity, nationality, race, culture, sexual orientation, gender, or disability and is often rooted in group-based prejudices (Earnshaw et al., 2018; Mulvey et al., 2018). In a developmental context, Earnshaw et al. (2018) refer to “youth living with socially devalued characteristics” (p. 178). Bias-based bullying represents an intergroup context; usually a member of a group with majority status targets a member of a group with minority status (cf. Palmer and Abbott, 2018). Intergroup processes like group membership and identity or adherence to group norms have been identified as relevant for understanding the reasons for children’s and adolescents changing attitudes and behaviours towards members of different groups.

An increasing body of research has documented the negative psychosocial consequences for children and youths experiencing bias-based bullying, with the gravest consequences resulting when an individual combines more than one of these personal characteristics (so-called intersectionality) (Garnett et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2020). In the school context, all forms of bullying have been shown to have a negative impact on the social and learning climate in classrooms, impede classroom management, and entail grave psychosocial, health, and academic consequences for all students involved, as documented also in reviews and meta-analyses (Kowalski et al., 2014; Moore et al., 2017; Montes et al., 2022).

Recent research has identified the critical role of adults, particularly teachers, in the bullying ecology (Burger et al., 2015; Van Aalst et al., 2022). Teachers’ perceptions, attitudes, beliefs, and related behaviours contribute to both the emergence and intensification of bullying. Teachers’ comments mentioned at the beginning of the text indicate that they can hold one-sided or even insensitive, uncaring views on bullying and particularly towards victims. Teachers who are not nor have been, involved in bullying prevention or intervention work often hold such views (Byers et al., 2011) and frequently do not intervene (Bauman and Del Rio, 2006). Among the factors preventing teachers from intervening we find, e.g., a lack of awareness, uncertainty or misunderstanding of the extent of bullying (Fekkes et al., 2004); an attitude of not seeing bullying as a problem or as normal behaviour (Hazler et al., 2001); a lack of sympathy/affection for the victim (Yoon and Kerber, 2003); a narrow view of violence neglecting relational or indirect forms (Bilz et al., 2016); or a lack of confidence that they can intervene effectively (Dedousis-Wallace et al., 2014). Regarding teachers’ reactions to bias-based bullying, the research literature is still rather limited. However, findings from mostly qualitative studies show that students experiencing bias-based bullying reported that teachers were dismissive and sometimes even contributed to the perpetuation of prejudice and bias in their classrooms (Sapouna et al., 2023, p. 284). The recent meta-analysis by van Verseveld et al. (2019) indicates that components reinforcing teachers’ attitudes, subjective norms, self-efficacy, knowledge, and skills towards bullying reduction enhance the effectiveness of anti-bullying programmes. Substantial evidence shows that systematic approaches, i.e., involving the whole school against bullying and where teacher interventions play a crucial role, are essential for successful prevention (Veenstra et al., 2014).1

If we consider teachers’ educational role and the moral and ethical basis of their professional practice (Campbell, 2003), it is very likely that the reactions they show in the event of bullying will have a direct impact on the behaviour of their pupils (Hektner and Swenson, 2012), but also on their attitudes and beliefs. If teachers do not send a clear message that they do not accept this type of behaviour, students can only guess at their attitudes (Yoon and Kerber, 2003) and may assume that bullying is okay. This reinforces the negative behaviour, changes the group norms in favour of bullying (Salmivalli and Voeten, 2004), and thus leads to its intensification (Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger and Perren, 2022). Yet teachers are in a unique position when it comes to promoting healthy social relationships in their classrooms, both between themselves and the pupils, and between pupils (Farmer et al., 2011), and thus acting towards preventing bullying (Dawes et al., 2023). A vast body of research indicates that the quality of children’s social relationships in the classroom is linked to their academic success (e.g., the meta-analysis by Bektas et al., 2015 or the review by Berkowitz et al., 2017). The same is true for positive relationships between students and their teachers, which have also been shown to be linked to students’ social and academic adjustment, a positive classroom and school climate, and bullying prevention (e.g., the literature review by McGrath and van Bergen, 2015). Still, teachers often do not feel responsible for fostering positive social relationships between students, i.e., they do not recognize it as part of their mission. However, as Farmer et al. (2011) state, “[…] teachers have the often unspoken and perhaps unrecognized responsibility to establish an invisible hand that promotes students’ self-directed, autonomous, and developmentally productive peer experiences” (p. 249). Thus, considering teachers’ unique position and crucial role, they need relevant knowledge, associated attitudes and skills, and favourable conditions to be able to prevent and intervene against bullying. This brings us to the question of professional ethos.

3 Teachers’ professional ethos

Teachers’ professional ethos (also known as pedagogical ethos) represent a highly abstract, multidimensional, and global construct (intangible and elusive, McLaughlin, 2005), which is not normally directly visible to an outside observer. Rather, it is made visible in specific situations, for example when conflicts arise (Oser, 1998). However, teachers’ professional ethos should not be considered solely as a global and highly abstract construct. Rather, it needs to be conceptualized in the context of a specific domain to also consider domain-specific facets that cannot be fully recognized at a more general level (Latzko et al., 2018). Such a conceptualization renders teachers’ professional ethos (more) visible since the domain-specific facets also offer anchor points for the operationalization of such ethos.

The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (1993) defines ethos as “the characteristic spirit of a culture, period, community, institution, etc., as manifested in its attitudes, aspirations, etc.; the character of an individual as represented by his values and beliefs” (p. 857). For a basic definition of teachers’ professional ethos, the first two elements referring to the social and individual levels, respectively, are especially relevant. The social aspect can be related to the professional community of teachers and educators and its associated professional institutions, e.g., schools or teachers’ unions. Garz and Raven (2018) refer to a professional ethos in the social professional context, while Brezinka (1990) distinguishes a communal professional morality from an individual’s professional ethos. Whereas individual professional ethos encompasses the moral attitudes a person adopts towards their professional work and the associated tasks and obligations, community professional ethos refers to the set of moral standards that apply to all people in the profession (Brezinka, 1990, p. 17). Debates about the definition and dimensions of teachers’ professional ethos are manifold and ongoing. Based on earlier conceptual work, I define teachers’ professional ethos as “the profession-related character of an individual teacher as represented by his or her professional values and beliefs, condensed in his or her professional competencies, and manifested in his or her professional actions” (Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, 2021, p. 286). The aspect of manifestation in professional actions is particularly relevant in the context of bullying because students must also see that teachers take a stand, communicate that bullying is harmful and act accordingly. Mere lip service undermines teachers’ credibility and positive authority.

How does ethos relate to teachers’ professional role and why is it relevant in the context of social relationships at school? According to Oser (2018) ethos determines the very professionalism of teachers on a social/community/institutional and individual level and is therefore inextricably linked to the professional role of teachers, their competences, and their professional actions. The area of school social relationships represents a relevant domain of teachers’ professional ethos as social relationships underlie all teaching and learning in some way or other (Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, 2021). The dynamic, process-oriented understanding teachers have of their professional role (what Kelchtermans, 2005, refers to as professional self-understanding) can be seen as representing both the basis and outcome of ongoing professional competence development and behaviour. In the present conceptualisation, this self-understanding—encompassing self-image, professional motivation, future perspective, self-esteem, and task perception (Kelchtermans, 2005)—is seen as a less abstract stratum of teachers’ professional ethos. It is accessible through (self-)reflection and establishes a link between teachers’ goals and values (moral and non-moral), on the one hand, and their actions in concrete educational (teaching-learning) situations, on the other. This will be described in more detail below.

While there are a few studies on the role of school ethos in bullying (e.g., Modin et al., 2017), research to date does not seem to have addressed teacher professional ethos. Recent research has stressed the significance of teachers’ professional ethos for the development of positive and solid social relationships at school, but without addressing the topic of bullying. For example, Dolev and Itzkovich (2021) emphasize that teachers’ socio-emotional skills are a relevant part of teachers’ professional competence and consider them to be a necessary component of ethos. They see these skills as a necessary prerequisite in teachers of showing care and concern for pupils’ emotions. Heinrichs et al. (2021) identify showing esteem for students as one of the social–emotional competencies that form part of teachers’ professional ethos. However, the abundant research on the relevance of positive social relationships in schools for healthy development and learning (e.g., Hamre et al., 2013) does not establish a link with teachers’ professional ethos. There is yet a gap in the research literature on teachers’ professional ethos in the domain of social relationships in schools and in particular in the context of bullying. The latter is even more surprising given that moral and ethical values such as caring, respect, or responsibility not only play an important role in preventing bullying (Alsaker and Valkanover, 2001), but are also essential components of teachers’ professional ethos (Oser and Biedermann, 2018). The model of teachers’ professional ethos in the area of bullying presented in the next section is an attempt to start filling this gap on the conceptual level. It has been developed bottom-up, based on my prevention and intervention practice, been enriched by significant research findings on bullying and bias-based bullying, and further elaborated top-down by including relevant conceptualizations of teachers’ professional ethos.

4 A model of teachers’ professional ethos in the area of school bullying

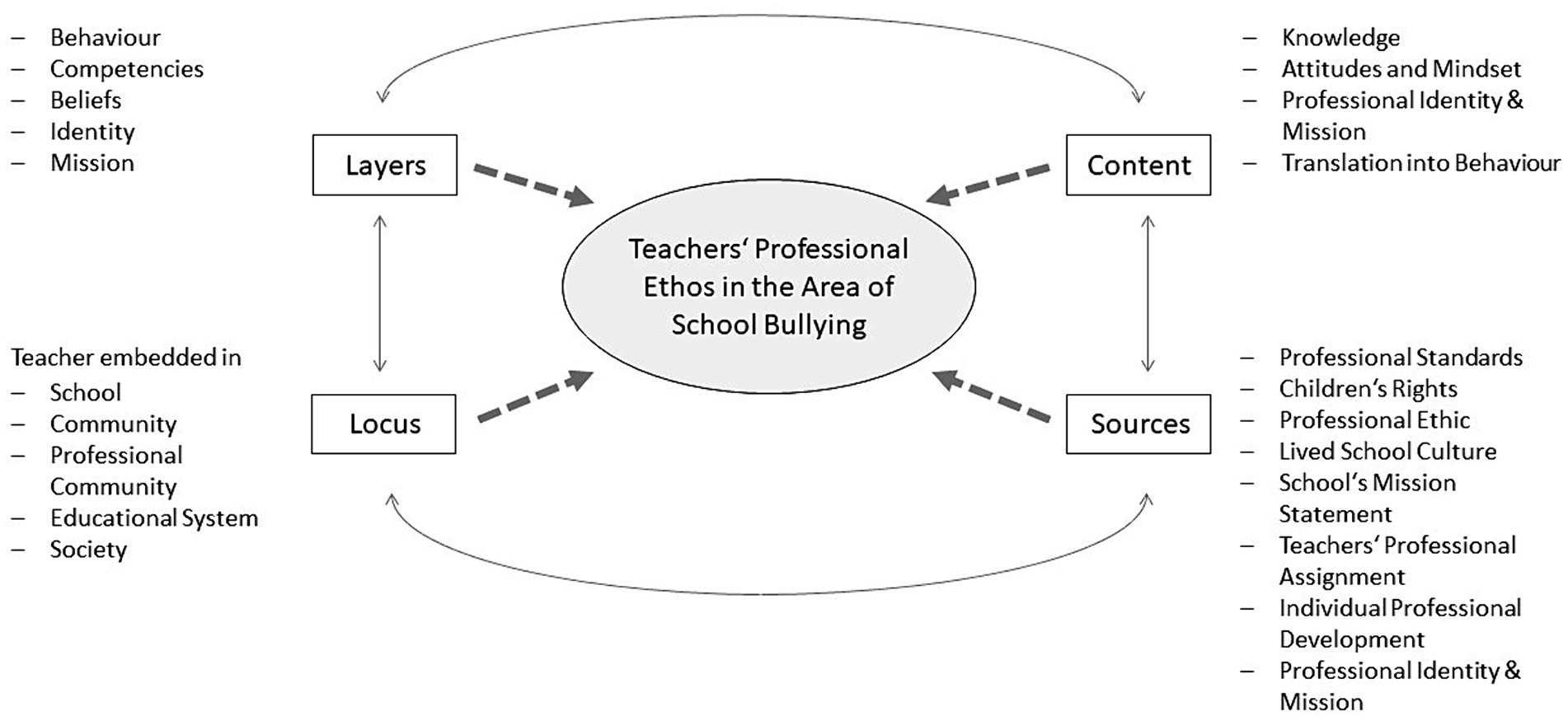

The (provisional) model presented here includes four perspectives: content, sources, layers, and locus (Figure 1). The model contains both descriptive and normative, i.e., prescriptive elements. The former are derived from established empirical findings on relevant factors contributing to the establishment and maintenance of bullying. The normative elements are based on saturated empirical findings concerning relevant factors that contribute to the effectiveness of prevention and intervention strategies in addressing bullying and/or promoting positive social relationships between students, in classrooms, and in schools.

4.1 The content of teachers’ professional ethos

Regarding the content dimension, four aspects of teachers’ professional ethos in the context of bullying can be identified: knowledge, attitudes and mindset, professional identity and mission, and implementation. These aspects form a basis for empowering teachers in the context of bullying, namely their ability, as professionals, to both have and show ethos (cf. Oser, 2018). The aspects mentioned are supposed to build on each other, with knowledge representing the foundation and implementation representing the apex. The first aspect, knowledge, refers above all to knowledge of the role social relationships play in the classroom and in school as well as the relevance of the quality of social relationships, e.g., regarding the impact of negative social relationships on the teaching-learning process and on the outcomes of that process. Teachers also need to be aware of the forms and consequences of bullying in general and of bias-based bullying in particular, especially with respect to diversity and inclusion. Teachers should have a thorough understanding of the basic characteristics of bullying, including the systematic abuse of power over time, the group dynamics, the psychosocial consequences for victims, witnesses, and perpetrators (of bullying), and the role of adults, particularly teachers and school staff. Regarding bias-based bullying, this includes also firmly grounded knowledge about the nature of prejudice and discrimination as well as about basic intergroup processes and dynamics evolving in both society and their local school context. Such knowledge is especially relevant with respect to characteristics that are devalued in teachers’ respective social and societal context, like, e.g., minority sexual orientation, obesity, disability, or minority ethnic or racial background. Further, teachers also need basic knowledge on effective prevention and intervention strategies and of the necessary conditions for their successful implementation. E.g., teachers need to adopt an ecological systems perspective (Espelage and Swearer, 2010) when managing social relationships in the classroom and at school. Such a perspective acknowledges the interconnected nature of interactions and social relationships between stakeholders on (and between) all levels of a given school and extends to the educational system as a whole. It requires teachers to understand that bullying is not made up of discrete, isolated and unrelated negative occurrences between two students, but includes the whole classroom and is related to the culture and climate of the school. A solid, evidence-based knowledge base about bullying and bias-based bullying is one of the cornerstones of teachers’ professional ethos in this area.

The second aspect, attitudes and mindset, refers first of all to the moral dimensions of teaching, especially moral values such as caring, justice, truthfulness, commitment, or respect, all of which are part of the fundamental conceptions of teachers’ professional ethos (Oser and Biedermann, 2018). These moral values are conceptualized here from a universalist position in the sense of preserving the dignity, rights, and welfare of every human being irrespective of their personal identity, characteristics, attributes, or group membership. The moral dimensions of teaching are also linked to children’s rights and teachers’ attitudes towards their professional mission. Consequently, it is not enough, to know that it is important to foster positive social relationships and thus prevent prejudice, discrimination, and bullying. Positive, discrimination-free relationships and their promotion must also be fully recognized and treated as relevant professional values and appreciated as such. Professional values are perceived as meaningful, important, and achievable in the sense of personal commitment. They are anchored in teachers’ professional self-understanding and serve as orientation for professional action (Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, 2021). Moreover, attitudes and mindset are also linked to teachers’ awareness of the hierarchical nature of the student-teacher relationship which places them in a position of responsibility. Therefore, the promotion of positive relationships should not be valued solely in its own right. The promotion of positive relationships must also be implemented from this position of professional responsibility, which encompasses leadership, agency, and accountability. A link can be made here with Latzko’s (2010) conception of the positive authority of teachers.

Professional identity and mission, the third aspect, transcend teachers’ professional self-understanding by focusing on the crystallized and stable side of the way teachers perceive themselves as professionals (identity) and on their raison d’être, i.e., the reason why they became teachers in the first place (mission; cf. Korthagen and Vasalos, 2005). In their onion-shaped model of reflection, Korthagen and Vasalos (2005) identify five levels that can influence teachers’ functioning: behaviour (the outermost layer of the onion), skills, beliefs, identity, and mission (the innermost layer of the onion). It is only when reflection also involves the core levels, i.e., identity and mission, that it can verily encourage professional development and therefore transformation. In terms of the content of teachers’ professional ethos, this means that it is not enough to accumulate sufficient knowledge and develop favourable attitudes and a corresponding mindset. Teachers must also recognize and accept both their professional role as (co-) educators, and their position of (shared) responsibility and accountability in the social ecology of their classroom and school to help create a safe environment for learning and development. Hence, the position of professional responsibility, as mentioned at the level of attitudes and mindset, needs to be recognized and accepted for the promotion of positive social relationships to be implemented. Teachers must accept the dual mission of Bildung and education and be prepared to promote pupils’ personal, social, and academic development. I postulate that only if this core is involved can we be sure that teachers genuinely (and reliably) care about pupils’ welfare and well-being and are able to integrate their own personal responsibility as professionals into their daily practice of promoting positive social relationships between their pupils.

The final aspect, implementation, refers to the important fact that intention can never replace real action. Implementation can be directly linked to the concept of moral character as described in Rest’s four-component model of moral action incorporating moral sensitivity, moral judgment, moral motivation, and moral character (Narváez and Rest, 1995). Moral character refers to the fact that a person actually implements the action alternative they deem morally appropriate, even if this involves difficulties, obstacles, etc. Examples are a teacher helping one of his pupils find a pen she mislaid although this means that he will miss the bus or a teacher speaking up in the teachers’ room when a colleague makes a racist joke even though everyone else is laughing. In this sense, teachers need to take measures to prevent and intervene against aggression, discrimination, and bullying even if this involves obstacles, difficulties, and uncertainties. It is essential that teachers encourage positive social relationships between students and show care, respect, responsibility, and moral courage when bullying occurs. The three aspects presented here (knowledge, professional identity and mission, translation into behaviour) can be linked to a broader conception of teachers’ professional competence inspired, e.g., by Weinert (2001) or Baumert and Kunter (2006), where attitudes and motivation are seen as constituent elements of professional competence. However, it is not enough to reconstruct the individual side of teachers’ professional ethos in the context of bullying. Given the social-ecological nature of the phenomenon and the need for favourable contextual conditions for effective and successful prevention and intervention, additional sources and locations (localisations) of this ethos need to be taken into account.

4.2 Sources of teachers’ professional ethos

When presenting the sources of teachers’ professional ethos in the context of bullying in general and bias-based bullying in particular, I want to emphasize that such ethos does not automatically exist once a student teacher has completed their studies and enters the teaching profession. Ethos must be developed. Furthermore, in line with Huberman’s (1989) view of differential pathways in teachers’ professional development, I want to highlight the dangers of disengagement and cynicism that can result if teachers’ professional ethos is not nurtured sufficiently. This includes both individual factors on the part of teachers and contextual factors and resources at different levels of the educational system. At the individual level, teachers’ ongoing professional development and commitment is one such source. Development and commitment are complemented and co-determined by teachers’ professional identity and mission, as described in the section on content above. Professional identity and mission are mentioned separately here. First, because, they are not automatically and/or explicitly included in models of teacher professional development. Second, by representing the crystallized and stable side of how teachers see themselves as professionals and of their raison d’être, professional identity and mission provide a motivational fallback system in the context of difficulties and crises. This is essential, as a teacher’s work is fraught with inconsistencies, uncertainty, and tensions or antinomies (Helsper, 1996). In this way, identity and mission help sustain teachers’ professional ethos when they face the challenges and adversities associated with bullying prevention and intervention. Some of the key elements of effective prevention programmes as identified by Ttofi and Farrington (2011) can be directly transposed to this individual level, such as classroom management.

At the level of the school context, both the professional community as lived in the school and the school’s philosophy and mission statement feed into teachers’ professional ethos by contributing to the lived culture of the school. Such lived culture includes all interactions and relationships at school and refers to what is experienced, done and implemented. School culture is therefore linked to action and behaviour (cf. Schoen and Teddlie, 2008) and can be linked back to showing ethos. Given that bullying prevention and intervention are more effective when a whole school approach is used, teachers’ individual awareness and their ability to have and demonstrate a sustainable ethos cannot be maintained if they remain isolated and/or are not taken seriously by their colleagues and the management. Accordingly, another of the key elements of effective prevention programmes identified by Ttofi and Farrington (2011)—namely a whole-school approach to bullying—can be related to the level of the school context. Additionally, we can also link this element to the ethos of a school. Indeed, school ethos is often related to concepts such as climate, culture, atmosphere, ambience, or ethical environment of the school (see McLaughlin, 2005, for further discussion). Dolev and Itzkovich (2021, p. 262) define school ethos as follows:

School ethos refers to observed practices and interactions of school members, both formal and informal, that reflect the prevailing cultural norms, assumptions, beliefs, aims and goals of the school in its entirety (Donnelly, 2000) and impact pedagogical practice (Husu and Tirri, 2007), school atmosphere and pedagogical outcomes (Allder, 1993).

As in Schoen and Teddlie’s (2008) conception of school culture, this definition establishes a clear link with behaviour. It aligns well with the current understanding of “translation into behaviour” as an aspect of the content of the professional ethos of individual teachers.

At the level of the professional community, sources feeding into teachers’ professional ethos include ethical professional codes, institutions of teacher education and their associated professional standards, the legally defined educational and professional assignment of teachers, and—as a superordinate international legal framework—the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child (UN General Assembly, 1989) guaranteeing, among others, children’s right to protection from violence and discrimination. The latter is also included as a source of professional ethos for teachers because it offers guidance and advice independent of the directives within individual schools, educational institutions, and communities and thus represents a universal ethical stance. By conceptualizing teachers’ professional ethos as embedded, the model accounts for the fact that teachers’ sense of mission or purpose and the related ongoing ethical professional development cannot be kept alive in isolation. This brings us to the locus and layers of teachers’ professional ethos.

4.3 Integration: locus and layers of teacher professional ethos

When we now combine the abovementioned considerations regarding the content and sources of teachers’ professional ethos in the context of bullying and bias-based bullying, we can argue that it is not sufficient to locate this ethos exclusively within an individual teacher. We need to conceptualise it as a contextualized and embedded professional ethic. Teachers are an inherent part of school, the community (professional and non-professional), and the social and communal system as a whole. Consequently, their professional ethos is embedded within the school and its framework conditions. It is also embedded in the locally prevailing, contextually bound understanding of teachers’ profession and their professional role (Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, 2021). Furthermore, their professional ethos is supported and nourished by various sources, some located within the individual, others at the surrounding levels of the school and educational system. As mentioned above, Aurin and Maurer (1990) describe teacher ethos as both an individual and a social phenomenon, while Brezinka (1990) differentiates between individual professional ethos and shared professional morality. Regardless which conception of ethos we use, the present conceptualization indicates that it is crucial to consider teachers’ professional ethos in the context of bullying as something that cannot be developed, implemented, and maintained in isolation. The best anti-bullying and anti-discrimination ethos can deteriorate and wither in adverse circumstances. This I learned from teachers who were highly interested in bullying prevention but who acted as lone fighters in their schools, striving to not give up, but often doing so.

In terms of the structure of such ethos, the onion model of Korthagen and Vasalos (2005) offers a potential starting point for its specification. Accordingly, we may assume that teachers’ professional ethos can cover (from surface to core) their behaviour, skills, beliefs, identity, and mission. Such a conception helps us to understand that the most favourable anti-bullying beliefs are not effective if they are not put into practice. Thus, in a movement from the center to the periphery, identity and mission feed beliefs, which in turn must inform skills and lead to action. At the same time, in a movement from the periphery to the center, behaviour can reflect professional skills, beliefs, identity and mission. As a result, teachers who respond quickly, sensitively, and appropriately to instances of bullying can be seen as demonstrating professional ethos. The onion model offers a promising avenue towards a more integrated conception of teachers’ professional ethos in the context of bullying and bias-based bullying. It can be related to the content, sources, and layers of such ethos, and thus allows us to consider both content and process at the same time.

5 Discussion and outlook

Teachers who have and display professional ethos in the context of bullying and bias-based bullying at school show responsibility and concern by taking action, by not looking away, by actively promoting positive social relationships particularly in the context of diversity and intersectionality, by mastering the necessary skills, and by having the necessary resources at their disposal. They care deeply. However, teachers need a safe and supportive environment in which to do so, because their ethos cannot be developed, implemented, and maintained in isolation. They also need opportunities to reflect on issues of professional ethos at school and to interact and collaborate with colleagues and school leaders. This is why I speak of a contextualized and integrated professional ethos.

An important concept in this respect is empowerment: to enable teachers to exercise their (moral-ethical) agency (cf. Bandura, 2018) by taking action. Exercising agency in bullying involves taking apparently simple measures such as pausing to take a closer look, sharing observations with colleagues, or talking to students. Agency is essential: one of the worst aspects of bullying is that the lack of reaction and action on the part of teachers and other adults in the system directly empowers those who bully and their entourage, i.e., the bystanders who directly and indirectly reinforce the abuse. The aggressors use bullying to improve their social status. They are seen as “cool” and learn that they can use aggressive means to achieve their self-centred ends. “It’s easy, it works, and it makes me feel good” is a famous response from a student who was asked why he systematically bullied another classmate (Sutton et al., 2001, p. 74). Over time, social norms in the classroom change. Bullying and picking on weaker students is normalized. Even students who previously tried to help the victim and take a stand begin to approve of these new norms and help to establish a culture conducive to harassment. Teachers who allow it to happen turn a blind eye or even consider it a normal part of school life, thereby unknowingly supporting the vicious circle of moral corrosion (Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger and Perren, 2022). It seems that these teachers neither have or at least do not show professional ethos but betray their own professionalism, probably without realising it. This betrayal causes despair among victims, witnesses, parents, and many other stakeholders and reflects negatively on the entire professional community.

The conceptualization presented here is a work in progress and not yet fully developed theoretically. At present, we can conceptualise teachers’ professional ethos in the context of bullying in general and bias-based bullying in particular as follows: it belongs to the domain of social relationships at school and represents a multidimensional construct. It encompasses the dimensions of content, source, layers, and locus, each of which comprises several aspects. The relationships between and within the dimensions need to be further clarified and subjected to empirical scrutiny. The same holds for its structure. Moreover, a clearer distinction between global (general) and specific (bullying-related) aspects and elements needs to be developed, especially regarding the specifics of bias-based bullying. This is relevant for promoting the professional development of teachers, both at the individual and the team and school levels, in the context of initial as well as in-service training. We need a better understanding of the very core of teachers’ professional ethos and the way it shows itself in all areas of teaching. Another issue to be addressed in the future relates to the notion of a whole-education approach in bullying (O’Higgins Norman et al., 2022) and how this is linked to promoting teachers’ but also schools’ professional ethos. We cannot put the “ethos burden” on teachers’ shoulders only. Due to the systemic nature of all education, ethical considerations regarding the kind of schools we want, the kind of social relationships and experiences we desire for our children, and the way we wish our societies to live diversity need to underlie our (re-)construction of educational systems. Laws, policies, regulations, and the like are helpful instruments. But they need to be used sensitively and responsibly by the respective stakeholders within the system, particularly principals and teachers.

From a perspective of teacher professionalization, the position assumed here fulfils at least three functions. First, it makes tangible the highly abstract concept of professional ethos, largely neglected in teacher education, and understands ethos as embedded within the systemic context of the school and educational system. Second, it summarizes current research on the phenomenon of bullying and the teacher’s role in the dynamic and thus establishes a link to evidence-based or evidence-informed practice (cf. Nevo and Slonim-Nevo, 2011; Farley-Ripple et al., 2018). Thirdly, at the level of initial and in-service training, it proposes a contextualized, system-oriented model which can function as an orientation for developing and fostering teachers’ professional ethos. It focuses on (future) teachers as core agents in the proactive promotion of positive classroom and school social relationships. Teachers must be empowered towards using targeted, effective, and sustainable programmes aimed at preventing bullying and bias-based bullying and at promoting positive social relationships as part of a collaborative effort to foster the school’s development. This last objective is not yet included in the current form of the model.

The model presented provides a basis for more in-depth, practice-oriented research on bullying prevention. For example, research can investigate what constitutes a teacher’s professional self-understanding in terms of promoting positive social relationships in the classroom and at school, and how this affects their attitudes and behaviour in everyday teaching practice. Such an approach makes it possible to operationalize different components of professional ethos and relate them to each other. In connection with this—and to counteract an individualized view—it is essential to study issues of fit between the teacher and the school context. E.g., the fit between teachers’ professional identity and the experienced school culture can be studied to determine how this fit relates to the frequency and intensity of bias-based bullying and other social behaviour (aggressive and prosocial). In this way, important knowledge can be gained for the development (or adaptation) of bullying prevention programmes. Finally, the model can be used as a basis for communication between teachers (and other stakeholders in the educational system) on the one hand and researchers on the other hand to jointly identify core issues regarding the needs of educational practice in the context of bias-based bullying, subsequent research, and the translation into initial teacher education, career long development and teaching practice.

Author’s note

This text is the result of ongoing conceptual work and builds on my earlier conceptualizations of teachers’ professional ethos in the area of school bullying. Earlier versions can be found in Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger (2021, 2024).

Author contributions

EG-H: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^However, while schools are increasingly competent in addressing general bullying incidents, policies used do not target bias and stigma, and the whole-school prevention programmes implemented are not tailored to bias-based bullying nor have they proven to be effective in reducing such bullying (Ramirez et al., 2023).

References

Alsaker, F. D., and Valkanover, S. (2001). “Early diagnosis and prevention of victimization in kin-dergarten” in Peer harassment in school. eds. J. Juvonen and S. Graham (New York, NY: Guilford), 175–195.

Aurin, K., and Maurer, M. (1990). Das Lehrerethos bedarf der Aufhellung durch empirisch-analytische Untersuchungen. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, Bildungspolitik und pädagogische Praxis 82, 31–36.

Bandura, A. (2018). Toward a psychology of human agency: pathways and reflections. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 13, 130–136. doi: 10.1177/1745691617699280

Bauman, S., and Del Rio, A. (2006). Preservice teachers’ responses to bullying scenarios: comparing physical, verbal, and relational bullying. J. Educ. Psychol. 98, 219–231. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.219

Baumert, J., and Kunter, M. (2006). Stichwort: Professionelle Kompetenz von Lehrkräften. Z. Erzieh. 9, 469–520. doi: 10.1007/s11618-006-0165-2

Bektas, F., Çogaltay, N., Karadag, E., and Ay, Y. (2015). School culture and academic achievement of students: a meta-analysis study. Anthropologist 21, 482–488. doi: 10.1080/09720073.2015.11891837

Berkowitz, R., Moore, H., Astor, R. A., and Benbenishty, R. (2017). A research synthesis of the associations between socioeconomic background, inequality, school climate, and academic achievement. Rev. Educ. Res. 87, 425–469. doi: 10.3102/0034654316669821

Bilz, L., Steger, J., Fischer, S. M., Schubarth, W., and Kunze, U. (2016). Ist das schon Gewalt? Zur Bedeutung des Gewaltverständnisses von Lehrkräften für ihren Umgang mit Mobbing und für das Handeln von Schülerinnen und Schülern. Zeitschrift Für Pädagogik 62, 841–860. doi: 10.25656/01:16893

Brezinka, W. (1990). Die Tätigkeit des Lehrers erfordert eine verbindliche Berufsmoral. Die Deutsche Schule: DDS; Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, Bildungspolitik und pädagogische Praxis 82, 17–21.

Burger, C., Strohmeier, D., Sproeber, N., Bauman, S., and Rigby, K. (2015). How teachers respond to school bullying: an examination of self-reported intervention strategy use, moderator effects, and concurrent use of multiple strategies. Teach. Teach. Educ. 51, 191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2015.07.004

Byers, D. L., Caltabiano, N., and Caltabiano, M. (2011). Teachers’ attitudes toward overt and covert bullying, and perceived efficacy to intervene. Australian. J. Teach. Educ. 36:8. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2011v36n11.1

Campbell, E. (2003). Moral lessons: the ethical role of teachers. Educ. Res. Eval. 9, 25–50. doi: 10.1076/edre.9.1.25.13550

Cornell, D., and Limber, S. P. (2015). Law and policy on the concept of bullying at school. Am. Psychol. 70, 333–343. doi: 10.1037/a0038558

Dawes, M., Starrett, A., Norwalk, K., Hamm, J., and Farmer, T. (2023). Student, classroom, and teacher factors associated with teachers’ attunement to bullies and victims. Soc. Dev. 32, 922–943. doi: 10.1111/sode.12669

Dedousis-Wallace, A., Shute, R., Varlow, M., Murrihy, R., and Kidman, T. (2014). Predictors of teacher intervention in indirect bullying at school and outcome of a professional development presentation for teachers. Educ. Psychol. 34, 862–875. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2013.785385

Dolev, N., and Itzkovich, Y. (2021). “Incorporating the development of social-emotional skills into the ethos of teachers and schools—practical and theoretical aspects” in The international handbook of teacher thos: Strengthening teachers, supporting learners. eds. F. Oser, K. Heinrichs, J. Bauer, and T. Lovat (New York: Springer International Publishing), 261–278.

Earnshaw, V. A., Reisner, S. L., Menino, D., Poteat, V. P., Bogart, L. M., Barnes, T. N., et al. (2018). Stigma-based bullying interventions: a systematic review. Dev. Rev. 48, 178–200. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2018.02.001

Espelage, D. L., and Swearer, S. M. (2010). “A social-ecological model for bullying prevention and intervention: understanding the impact of adults in the social ecology of youngsters” in Handbook of bullying in schools: An international perspective. eds. D. L. Espelage and S. M. Swearer (London: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group), 61–72.

Farley-Ripple, E., May, H., Karpyn, A., Tilley, K., and McDonough, K. (2018). Rethinking connections between research and practice in education: a conceptual framework. Educ. Res. 47, 235–245. doi: 10.3102/0013189X18761042

Farmer, T. W., McAuliffe Lines, M., and Hamm, J. V. (2011). Revealing the invisible hand: the role of teachers in children's peer experiences. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 32, 247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2011.04.006

Fekkes, M., Pijpers, F. I. M., and Verloove-Vanhorick, S. P. (2004). Bullying: who does what, when and where? Involvement of children, teachers and parents in bullying behavior. Health Educ. Res. 20, 81–91. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg100

Garnett, B. R., Masyn, K. E., Austin, S. B., Miller, M., Williams, D. R., and Viswanath, K. (2014). The intersectionality of discrimination attributes and bullying among youth: an applied latent class analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 43, 1225–1239. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0073-8

Garz, D., and Raven, U. (2018). “‘Stellvertretend die Welt der Lernenden deuten’. Professionalisierungstheoretische Überlegungen zum Lehrberuf” in Das professionelle Ethos von Lehrerinnen und Lehrern. Perspektiven und Anwendungen. eds. H. Schärer and M. Zutavern (Münster: Waxmann), 43–55.

Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E. (2021). “Beyond attitudes and teaching methods: the role of teacher professional ethos in tackling bullying” in The international handbook of teacher ethos—Strengthening teachers, supporting learners. eds. F. Oser, K. Heinrichs, J. Bauer, and T. Lovat (New York: Springer Nature), 279–294.

Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E. (2024). “Les enseignants ont-ils besoin de compétences socio-morales? Le rôle de l’éthique professionnelle dans le contexte du harcèlement” in Transformer les pratiques en éducation: Quelles recherches pour quels apports? eds. T. Coppe, A. Baye, and B. Galand (Louvain-la-Neuve: Presses universitaires de Louvain), 103–116.

Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E., and Perren, S. (2022). “The moral dimensions of bullying at school: a social-ecological process perspective” in Handbook of moral development. eds. M. Killen and J. Smetana. 3rd ed (London: Routledge), 437–453.

Hamre, B. K., Pianta, R. C., Downer, J. T., DeCoster, J., Mashburn, A. J., Jones, S. M., et al. (2013). Teaching through interactions: testing a developmental framework of teacher effectiveness in over 4,000 classrooms. Elem. Sch. J. 113, 461–487. doi: 10.1086/669616

Hazler, R., Miller, D., Carney, J., and Green, S. (2001). Adult recognition of school bullying situations. Educ. Res. 43, 133–146. doi: 10.1080/00131880110051137

Heinrichs, K., Ziegler, S., and Warwas, J. (2021). “Teacher ethos as intention to implement appreciation in teacher-student relations: a closer look at underlying values and behavioral indicators” in The international handbook of teacher ethos: Strengthening teachers, supporting learners. eds. F. Oser, K. Heinrichs, J. Bauer, and T. Lovat (London: Springer International Publishing), 237–260.

Hektner, J. M., and Swenson, C. A. (2012). Links from teacher beliefs to peer victimization and bystander intervention: tests of mediating processes. J. Early Adolesc. 32, 516–536. doi: 10.1177/0272431611402502

Helsper, W. (1996). “Antinomien des Lehrerhandelns in modernisierten pädagogischen Kulturen. Paradoxe Verwendungsweisen von Autonomie und Selbstverantwortlichkeit” in Pädagogische Professionalität. Untersuchungen zum Typus pädagogischen Handelns. eds. A. Combe and W. Helsper (Berlin: Suhrkamp), 521–569.

Huberman, M. (1989). The professional life cycle of teachers. Teach. Coll. Rec. 91, 31–57. doi: 10.1177/016146818909100107

Husu, J., and Tirri, K. (2007). Developing whole school pedagogical values – A case of going through the ethos of «good schooling». Teaching and Teacher Education, 23, 390–401. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2006.12.015

Kelchtermans, G. (2005). Teachers’ emotions in educational reforms: self-understanding, vulnerable commitment and micropolitical literacy. Teach. Teach. Educ. 21, 995–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2005.06.009

Korthagen, F., and Vasalos, A. (2005). Levels in reflection: core reflection as a means to enhance professional growth. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 11, 47–71. doi: 10.1080/1354060042000337093

Kowalski, R. M., Giumetti, G. W., Schroeder, A. N., and Lattanner, M. R. (2014). Bullying in the digital age: a critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychol. Bull. 140, 1073–1137. doi: 10.1037/a0035618

Latzko, B. (2010). “Moral education in school: teachers’ authority and students’ autonomy” in Moral courage and the normative professionalism of teach-ers. eds. C. Klaassen and N. Maslovaty (Leiden: Brill Sense), 91–102.

Latzko, B., Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E., Pässler, A.-C., and Hesse, I. (2018). Food security as a domain of teachers’ professional ethos?! MENON J. Educ. Res. 3, 125–136.

McGrath, K. F., and van Bergen, P. (2015). Who, when, why and to what end? Students at risk of negative student–teacher relationships and their outcomes. Educ. Res. Rev. 14, 1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2014.12.001

McLaughlin, T. (2005). The educative importance of ethos. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 53, 306–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8527.2005.00297.x

Modin, B., Låftman, S. B., and Östberg, V. (2017). Teacher rated school ethos and student reported bullying—a multilevel study of upper secondary schools in Stockholm, Sweden. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14:1565. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14121565

Montes, Á., Sanmarco, J., Novo, M., Cea, B., and Arce, R. (2022). Estimating the psychological harm consequence of bullying victimization: a meta-analytic review for forensic evaluation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:13852. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192113852

Moore, S. E., Norman, R. E., Suetani, S., Thomas, H. J., Sly, P. D., and Scott, J. G. (2017). Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Psychiatry 7, 60–76. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v7.i1.60

Mulvey, K. L., Hoffman, A. J., Gönültaş, S., Hope, E. C., and Cooper, S. M. (2018). Understanding experiences with bullying and bias-based bullying: what matters and for whom? Psychol. Violence 8, 702–711. doi: 10.1037/vio0000206

Narváez, D., and Rest, J. (1995). “The four components of acting morally” in Moral development: An introduction. eds. W. M. Kurtines and J. L. Gewirtz (Boston: Allyn and Bacon), 385–399.

Nevo, I., and Slonim-Nevo, V. (2011). The myth of evidence-based practice: towards evidence-informed practice. Br. J. Soc. Work. 41, 1176–1197. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcq149

New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (1993). Ethos. In the new shorter Oxford English dictionary. 4th Edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

O’Higgins Norman, J., Berger, J., Yoneyama, S., and Cross, D. (2022). School bullying: Moving beyond a single school response to a whole education approach. Pastoral Care Edu. 40, 328–341. doi: 10.1080/02643944.2022.2095419

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishers.

Oser, F. (2018). “Unterrichten ohne Ethos” in Das professionelle Ethos von Lehrerinnen und Lehrern. Perspektiven und Anwendungen. eds. H. Schärer and M. Zutavern (Waxmann: Münster), 57–72.

Oser, F., and Biedermann, H. (2018). The professional ethos of teachers. Is only a procedural discourse approach a suitable model? In A. Weinberger and H. Biedermann, J-L. Patry & S. Weyringer (Eds.), Professionals’ ethos and education for responsibility. Brill, Leiden.

Palmer, S. B., and Abbott, N. (2018). Bystander responses to bias-based bullying in schools: a developmental intergroup approach. Child Dev. Perspect. 12, 39–44. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12253

Ramirez, M. R., Gower, A. L., Brown, C., Nam, Y.-S., and Eisenberg, M. E. (2023). How do schools respond to biased-based bullying? A qualitative study of management and prevention strategies in schools. Sch. Ment. Heal. 15, 508–518. doi: 10.1007/s12310-022-09565-8

Salmivalli, C., and Voeten, M. (2004). Connections between attitudes, group norms, and behaviour in bullying situations. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 28, 246–258. doi: 10.1080/01650250344000488

Sapouna, M., Amicis, L. D., and Vezzali, L. (2023). Bullying victimization due to racial, ethnic, citizenship and/or religious status: a systematic review. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 8, 261–296. doi: 10.1007/s40894-022-00197-2

Schoen, T., and Teddlie, C. (2008). A new model of school culture: a response to a call for conceptual clarity. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 19, 129–153. doi: 10.1080/09243450802095278

Sutton, J., Smith, P. K., and Swettenham, J. (2001). “It's easy, it works, and it makes me feel good”: a response to Arsenio and Lemerise. Soc. Dev. 10, 74–78. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00149

Ttofi, M. M., and Farrington, D. P. (2011). Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying: a systematic and meta-analytic review. J. Exp. Criminol. 7, 27–56. doi: 10.1007/s11292-010-9109-1

Van Aalst, D. A. E., Huitsing, G., and Veenstra, R. (2022). A systematic review on primary school teachers’ characteristics and behaviors in identifying, preventing, and reducing bullying. Int. J. Bull. Prevent. 6, 124–137. doi: 10.1007/s42380-022-00145-7

Van Verseveld, M. D. A., Fukkink, R. G., Fekkes, M., and Oostdam, R. J. (2019). Effects of antibullying programs on teachers’ interventions in bullying situations. A meta-analysis. Psychol. Sch. 56, 1522–1539. doi: 10.1002/pits.22283

Veenstra, R., Lindenberg, S., Huitsing, G., Sainio, M., and Salmivalli, C. (2014). The role of teachers in bullying: the relation between antibullying attitudes, efficacy, and efforts to reduce bullying. J. Educ. Psychol. 106, 1135–1143. doi: 10.1037/a0036110

Weinert, F. E. (2001). “Concept of competence: a conceptual clarification” in Defining and selecting key competencies. eds. D. S. Rychen and L. H. Salganik (Göttingen: Hogrefe & Huber Publishers), 45–65.

Xu, M., Macrynikola, N., Waseem, M., and Miranda, R. (2020). Racial and ethnic differences in bullying: review and implications for intervention. Aggress. Violent Behav. 50:101340. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2019.101340

Yoon, J. S., and Kerber, K. (2003). Bullying: elementary teachers’ attitudes and intervention strategies. Res. Educ. 69, 27–35. doi: 10.7227/RIE.69.3

Keywords: teachers, teachers’ professional ethos, bias-based bullying, school bullying, teacher professional development, ecological systems perspective

Citation: Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger E (2024) Teachers need socio-moral competencies to successfully address bias-based bullying: The case for promoting professional ethos. Front. Educ. 9:1406932. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1406932

Edited by:

Maria Sapouna, University of the West of Scotland, United KingdomReviewed by:

Ioannis Dimakos, University of Patras, GreeceConcetta Esposito, University of Naples Federico II, Italy

Elisabeth Davies, University of the West of Scotland, United Kingdom, in collaboration with reviewer CE

Copyright © 2024 Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eveline Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, ZXZlbGluZS5ndXR6d2lsbGVyQHBoc3ouY2g=

Eveline Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger

Eveline Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger