- Attallah College of Educational Studies, Chapman University, Orange, CA, United States

Introduction: This pilot case study paper demonstrates how school programming can be aligned and enhanced to better create a climate of peace on an elementary school campus by utilizing an integral peace leadership lens. Working collectively as a Peace Leadership Advisory Group, the elementary school leadership team, and the university research team helped to align existing programming and explore and implement new programming to create a comprehensive plan for bringing peace ideas together at the elementary school level.

Methods: This pilot was a single case study that utilized Participatory Action Research. Data were collected through observation, survey, and interviews with school leadership and analyzed using thematic analysis, descriptive statistics, and grounded theory methods, respectively.

Results: The pilot study revealed that the efforts to build peace on campus were successful overall, with students and staff having a positive experience with peace programming throughout the academic year.

Discussion: The findings indicate that aligning existing programming as a way to frame a culture of peace and then supplementing that programming with additional activities serves as a way to unite a campus around the idea of peace.

Introduction

Cultivating peaceful, inclusive, safe, and supportive school communities is a longstanding imperative for educators, scholars, and policymakers. Decades of school climate research around the world have demonstrated that positive perceptions of safety, relationships, teaching and learning structures, supportive institutional environments, and effective school improvement processes are significantly associated with a number of positive student and system-level outcomes, including positive youth development, risk prevention, health promotion, improvements in student learning and academic achievement, decreased dropout rates, increased graduation rates, and teacher retention (La Salle, 2018; Thapa et al., 2013). School communities that invest in programming aimed toward strengthening relationships, school safety, supportive disciplinary environments, respect for diversity, student participation, and physical environment experience the most school climate improvement (Bradshaw et al., 2021).

While there is no shortage of evidence-based practices that are linked to improving school climate, the inundation of school improvement initiatives combined with the complexities of fast-changing educational environments often results in fragmented support systems that compete for resources rather than synergize toward shared goals (McIntyre Miller and Abdou, 2018). As educators enter an era with even more challenges related to long-term global pandemic recovery efforts, a rise in normalized bigotry and intolerance, and global mental health crises, rethinking how school climate improvement efforts are conceptualized, organized, and implemented is a necessary endeavor.

Using an interdisciplinary perspective, this paper builds from the theoretical perspectives outlined in McIntyre Miller and Abdou (2018) and details the integration of peace education and peace leadership theories with school climate initiatives to enhance implementation and outcomes. We begin by describing how peace education theories and integral peace leadership (McIntyre Miller and Green, 2015; McIntyre Miller and Alomair, 2022), in particular, have the potential to align with and strengthen common initiatives in schools aimed at improving school climate. We then describe an elementary school pilot case study where researchers supported a school team in aligning and augmenting an existing social-emotional learning framework to center around principles of peace and inclusion. The paper concludes with a discussion about lessons learned throughout the process as well as recommendations for future practice.

Literature review and conceptual frameworks

In this literature review, we set the stage for this pilot case study by examining peace education and peace leadership and how this literature aligns with school climate concepts. First, we present the relevant work around peace education and then explore peace leadership.

Peace education

The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) defined peace education as the “process of promoting the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values needed to bring about behavior changes…to resolve conflict peacefully, and to create the conditions conducive to peace” (Fountain, 1999, p. 1). Peace education programs are often characterized as supportive, egalitarian, built on trust-based contact, and emphasize cultural awareness and respectful dialogue (Kester, 2012; Parker and Bickmore, 2020). Scholars in the field advocate for programs to be critical and consider inequitable social relations, issues of power, and local and marginalized voices (Bajaj, 2019).

Often, peace education programming is seen as peacebuilding, with the goal to “disrupt social hierarchies and rebuild relationships, presenting substantial opportunities among broader populations of students to have their voices heard” (Bickmore, 2011a, p. 40). Peacebuilding is a proactive and multifaceted approach that addresses systemic violence, including inter-group division, marginalization, and exploitation. Peacebuilding paradigms are focused on positive peace, which expands beyond just striving for the absence of violence (i.e., negative peace) and fosters cultures of respect, justice, inclusiveness, and harmony (Cremin and Guilherme, 2016). Savelyeva and Park (2024) argued that peace education and principles of justice must be aligned.

Peacebuilding is distinguished from peacekeeping and peacemaking, which both reflect more reactive and responsive approaches to cultivating institutional peace (Bickmore, 2011a) and are examples of negative peace. Peacekeeping, arguably the most prevalent security approach in schools, focuses on maintaining order and control through surveillance and punishment. Examples of peacekeeping approaches in schools include overreliance on punitive and exclusionary discipline practices and increased policing strategies, such as school resource officers and metal detectors. Peacemaking responses focus on problem and conflict resolution through dialogue, negotiation, and deliberation, often manifested through restorative justice initiatives, which are becoming more frequently embedded in schools (Bickmore, 2011a). Peacemaking approaches take a more democratic and power-sharing approach to conflict management by increasing student participation in problem-solving.

While all three concepts play important roles in managing violence and conflict in society and in school settings, it is important for leaders to examine the synergy of positive peace and negative peace approaches. For example, while peacekeeping may play an important role in maintaining safety during incidents or threats of violence (Bickmore, 2011a), there is often a resulting overemphasis on passive compliance, limitations on student ownership and democracy, and overuse of punitive and exclusionary discipline. In contrast, though peacemaking approaches reflect more equitable and effective problem-solving and conflict-resolution structures, they require significant time and resources and may not be feasible as primary methods of violence response and prevention. Proactive peacebuilding efforts, which are aimed at constructing sustainable, peaceful campus cultures and social changes at the universal level, are critical elements of violence prevention yet often under-resourced (Sagkal et al., 2016; Velez, 2021; Yilmaz, 2017). These will be further explored in the section below.

School initiatives aligned with peace education

With the growing recognition and empirical evidence that punitive and exclusionary school discipline practices driven by peacekeeping principles are ineffective, harmful, and disproportionately affect Black, Latinx, and disabled students (Skiba, 2002; Skiba et al., 2011), more educators and scholars are turning toward initiatives characterized by tenets of peacemaking and peacebuilding approaches. Levine and Tamburrino (2014) posited that instilling an appreciation of differences in culture, appearance, behavior, and abilities in children from a young age can reduce discriminatory actions and behaviors in the educational environment. Sagkal et al. (2012) speculated that introducing peace education programs in schools can facilitate students' interpersonal and intergroup peace and further impact future international peace. Parker and Bickmore (2020) found similar results in their study of classroom peace circles for restorative dialogue. Two such programs, positive discipline frameworks and anti-bullying initiatives, have, however, demonstrated that successful implementation may be possible.

Positive discipline frameworks

Despite historical and ongoing barriers to peacebuilding efforts, schools have made significant progress in normalizing and adopting programs and initiatives that are aligned with the positive peace principles of peace education. For example, school-wide positive behavior support (SWPBS) is a common evidence-based practice that shifts educators away from relying primarily on punishment and exclusion to manage behavior toward a focus on teaching and reinforcing social, emotional, and behavioral competencies (Santiago-Rosario et al., 2023). Similarly, social-emotional learning (SEL) initiatives have continued to expand in schools for the last several decades, with the growing empirical evidence demonstrating that explicit teaching of self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, responsible decision-making, and relationship skills are critical for student-level outcomes and peaceful schools and societies (Greenberg, 2023). While positive discipline frameworks are important in all school settings, investing in such efforts in elementary education is critical for proactive approaches to positive peace and school violence prevention.

Anti-bullying programs

Another way that schools work toward a culture of peace is through bullying prevention efforts, which are imperative proactive peace initiatives that should begin in elementary schools (Fraguas et al., 2021; Levine and Tamburrino, 2014; Sagkal et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2005). Whether overt or covert in nature, bullying impacts all children who can embody the roles of aggressor, target, or witness over time (Bickmore, 2011b; Levine and Tamburrino, 2014; Smith et al., 2005). Bickmore (2011b) suggested that traditional means of disciplining students (i.e., punishment and exclusion) are not successful in regulating social behaviors like discriminatory harassment and bullying and called for more “equitable and effective approaches to handling conflict, violence, and social exclusion in schools” (p. 651). Further, Bickmore (2011b) noted that schools that have demonstrated efficient implementation of anti-violence programming used a multi-pronged method, including components of social and cognitive competence, inclusion, respect, acceptance of difference, and relationship building in place of punitive approaches. This departure from narrow, corrective processes points to a more holistic peace education approach.

Despite the common goals of these various school initiatives, however, they often function as separate processes with minimal support, leaving educators feeling overwhelmed and burned out from initiative fatigue (McIntyre Miller and Abdou, 2018). As a result, programs are often not implemented with fidelity or abandoned in early stages due to lack of effectiveness or buy-in. Therefore, it is important to consider the content of peace education initiatives and the process through which they are implemented, particularly the leadership practices and frameworks that guide them. Through a multifaceted approach that emphasizes peacebuilding and peacemaking tenets across all aspects of student support, school systems can more meaningfully promote both negative and positive peace to benefit students, educators, communities, and society as a whole. The current study set forth to examine the process of integrating peace leadership frameworks to strengthen existing peace education initiatives.

Peace leadership literature

Peace leadership is an emergent field that builds from leadership studies, peace studies, conflict transformation, and peace psychology and has been defined as “the intersection of individual and collective capacity to challenge aggression and violence and build positive, inclusive social systems and structures” (McIntyre Miller, 2016, p. 223). In recent years, the peace leadership literature has included multiple theoretical lenses and empirical research (e.g., Abdou et al., 2023; Amaladas, 2018; Amaladas and Byrne, 2018; Bayard, 2022; Chinn and Falk-Rafael, 2018; Dinan, 2018; Ledbetter, 2012; McIntyre Miller and Abdou, 2018; McIntyre Miller and Alomair, 2022; McIntyre Miller et al., 2024; Schellhammer, 2016, 2018, 2022; Schockman et al., 2019). These frames set peace leadership toward the creation of a culture of peace, a process for positive change, and a way to foster community, organizational, and societal growth.

Integral peace leadership

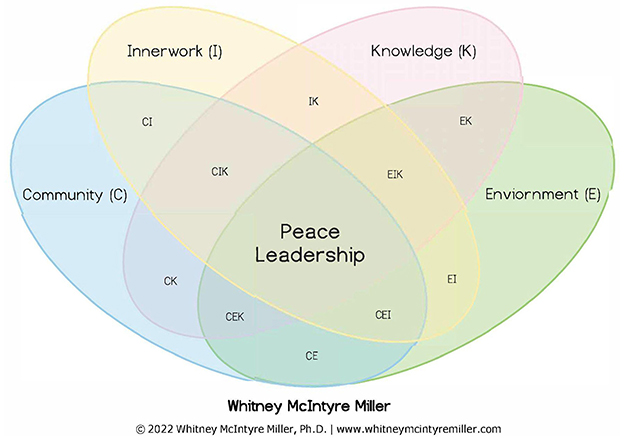

One framework of peace leadership is integral peace leadership, which reveals the holonic nature of four conceptual areas of peace leadership that are all essential in the individual and collective work of peacemaking and peacebuilding (McIntyre Miller and Green, 2015; McIntyre Miller and Alomair, 2022; McIntyre Miller et al., 2024). These four areas consist of Innerwork, Knowledge, Community, and Environment as illustrated in Figure 1. Each of these areas, taken individually and holistically, informs the ways that school leaders can work to build a culture of peace.

• The Innerwork area is that which prepares one for doing the personal work of peace, such as mindfulness, forgiveness, and empathy. This work often manifests in schools through Character Development programs, mindfulness training, and workshops.

• The Knowledge area highlights the skills and practices of interdependent connections of peace, such as conflict transformation practices, education, and peacebuilding. Within a school context, this work is often seen, as discussed in the literature above, in positive behavior interventions and social-emotional learning programs.

• The Community area is a collective space of collaborative action, such as utilizing and augmenting social capital and coalition building. Taken in a school context, the Community area is often seen in the formation of professional learning communities and home-school connections.

• The Environment area is the space for systems work, such as advocacy, networking, and structural interventions. In schools, systems thinking and distributed leadership practices are often used to bring in the Environment area (McIntyre Miller and Green, 2015; McIntyre Miller and Abdou, 2018; McIntyre Miller and Alomair, 2022).

In our preceding article (McIntyre Miller and Abdou, 2018), we set out a path to utilize the integral peace leadership framework to create peaceful school climates. Recognizing the progress and potential for many mainstream evidence-based frameworks already familiar to most educators, we posited that it may be helpful to analyze aligned initiatives and the school climate landscape through the lens of integral peace leadership, thus aligning current practices in intentional and meaningful ways. Therefore, the work at school sites is not necessarily adopting new programs but rather strengthening and reframing many commonplace behavioral, social-emotional, and equity initiatives in schools as interrelated and complementary systems that are all aimed toward cultivating peaceful schools and communities. Therefore, it is this notion of aligning school-based programmatic peace work within the framework of integral peace leadership that sets the stage for this study.

The peace project pilot

The Peace Project pilot was a single case study supported by a small internal university grant,1 which was initiated to create and sustain research collaborations with local school districts. The primary goal of the Peace Project pilot case study was to support an elementary school in identifying and aligning its existing peace-related programming and activities with the integral peace leadership framework and then enhancing these efforts through new programs, activities, and supplies. Using a Participatory Action Research (PAR) approach, the university researchers joined with the school leadership team as co-researchers to offer consultation, particularly around aligning existing initiatives, to provide resources to enhance programming and offerings, and to assess stakeholder perceptions and acceptability of these efforts.

School context

This project was a single case study conducted at an Orange County, California, suburban elementary school during the 2022–2023 school year. According to the California School Dashboard (California Department of Education, 2023), during the 2022–2023 school year, the school had just over 550 students. Of these students, 4.5% were English learners, and 15.8% were considered socioeconomically disadvantaged. Just 0.2% of the students were foster youth. Students at the school consistently score highly on both English and Mathematics assessments. The school sees just under a 10% chronic absenteeism rate and has a very low suspension rate. The school had just over 30 staff, 22 of whom were teachers. In addition, the school has an active Parent Teacher Association (PTA) that also supported the study.

Project timeline and process

In the spring of 2022, the university researchers brought the aforementioned grant opportunity to the school principal, as one of the university researchers had an existing relationship with the principal and elementary school. Therefore, the school was chosen based on convenience and a previous working relationship. Working together, the university researchers and school principal wrote the grant proposal. Upon receiving the grant, the university research team obtained Institutional Review Board approval.2 Then, the first step of study implementation was creating a Peace Leadership Advisory Group.

Peace leadership advisory group (PLAG)

Building from our previous (McIntyre Miller and Abdou, 2018) ideas for initiating peace leadership activities in schools, a Peace Leadership Advisory Group (PLAG) was assembled to oversee the implementation of the Peace Project. This was particularly important, as meeting the project goals of strengthening the integration of complementary peacebuilding initiatives required collaboration across multiple school leaders. The PLAG ultimately began with the writing of the grant, but then was expanded so that at the start of the project the PLAG included the university researchers, consisting of two faculty and two graduate research assistants, and the school leadership team, consisting of two teachers, the principal, and the school counselor.

Participatory action research

A Participatory Action Research (PAR) approach was adopted to prioritize collaboration and incorporation of local knowledge, in this case, the school community context, as opposed to traditional researcher-driven processes (Greenwood et al., 1993). The PLAG processes and decisions were grounded in the PAR goals of collaborative goal development, producing knowledge and action that is directly useful to the school and empowering the school team through consciousness-raising around peace leadership theory (Kidd and Kral, 2005). Therefore, the PLAG worked together as collaborators and co-researchers, rather than the university researchers entering the project with specific goals or hypotheses, allowing for a flexible and egalitarian stance to support and study the natural progression of the work.

The term PLAG will be used in this article to indicate the collective work of university researchers and the school leadership team. When a sub-group conducted independent work, that will be noted by using the term university researchers or school leadership team. Together, the PLAG designed and implemented the project's goals, activities, data collection, assessment plan, and the following research questions (Marshall et al., 2022; Mills and Birks, 2014).

1. In what ways might an elementary school align existing practices to be more focused on peacebuilding?

2. How might an elementary school use the integral peace leadership framework to augment existing programs to be more inclusive of peace practices and activities at the school?

3. How do the students and staff perceive the social validity of the project's peace practices and activities?

With the formation of the PLAG and the process and research questions in place, the team began mapping out the existing school programs throughout the academic year using a shared spreadsheet. Next, the PLAG chose monthly themes of foci based on these events and the goals set forth by the district's Wellness team, which included the school counselor. Each of these events was aligned with the chosen themes and was linked to an integral peace leadership area. Based on this information, the PLAG brainstormed ways to enhance existing programs to increase opportunities to bring the theme of peace to campus, resulting in two new initiatives. A complete overview of each theme, activity, and effort of the Peace Project is detailed in the Findings section below.

Study participants

The Peace Project was a school-wide initiative with the whole school community serving as the pilot case. While the whole school participated in the initiatives and activities, only school staff and upper-grade students were invited to participate in a survey assessing the project. These participants were selected as both upper grade students, staff, and teachers could best articulate their feedback on the project. All of these populations were invited to participate in the survey portion. School members who participated in the survey portion of the project, as described in detail below, included 180 4th and 5th grade students and 21 staff members representing administrators, teachers, and ancillary support staff. In addition, three of the school leadership team members agreed to participate in a final interview. The school team chose not to collect participant demographic information to maintain anonymity in the quantitative data collection.

Data collection and analysis

To assess the effectiveness of the project, the PLAG adopted a mixed methods approach to allow for a broader quantitative measurement of the school communities' perspectives of the project while also systematically examining the integration process and the nuanced experiences of school leaders who designed and implemented the programming. According to Leavy (2017), mixed methods research designs align with studies aiming to explain, describe, or evaluate, combining and integrating qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis. This pilot case study employed a convergent mixed method design, where the qualitative and quantitative data are collected concurrently, analyzed, and brought together to substantiate outcomes.

Therefore, the data for this study were comprised of three distinct yet interrelated types. Each was collected and analyzed separately, and then all of the analyzed data were taken together to form a comprehensive view of the pilot case. First, observational and process-oriented data from the PLAG were systematically collected and thematically analyzed to better understand how peace leadership tenets were aligned and additive. Second, quantitative data were collected from a survey that the school leadership team administered to all staff and 4th and 5th-grade students and analyzed using descriptive statistics. Finally, qualitative data were collected through school leadership team interviews and analyzed utilizing a grounded theory approach. Each of these processes will be discussed below.

Observational data collection and analysis

As the Peace Project development and evaluation process was iterative and emergent, collecting data about the process was important. Observational data were collected during meetings with the PLAG and participation in events and opportunities on campus to systematically document the action research process and implementation activities. In addition to meeting notes and on-campus participation, the university research team collected each Monday Message, a weekly school-wide newsletter that mentioned Peace Project-related activities, themes, and an overview of the previous week's activities. These data were sorted and analyzed by themes to illustrate the structure and implementation of the peace project.

Quantitative data collection and analysis

Being a pilot, the PLAG decided they were most concerned about how meaningful and acceptable the activities and initiatives were to the participating students and staff. This led the team to choose a social validity assessment as the best approach to determine the value of the Peace Project to the school community (Huntington et al., 2022). Further, as social validity is an iterative and ongoing assessment process to inform future action, developing social validity measures for the Peace Project was also identified as a valuable sustainability practice so that the school leadership team could administer the survey yearly for continuous improvement.

To that end, the PLAG created two survey versions (one for students and one for staff) to assess the social validity of the Peace Project by adapting two existing social validity questionnaires by Gallegos-Guajardo et al. (2013) and Guadalupe et al. (2015), used for program evaluations. The staff survey was developed first and then modified by the school leadership team to reflect developmentally appropriate language for administration to all 4th and 5th-grade students. The surveys consisted of 17 questions presented on a 4-point Likert-type scale, with ratings indicating (1) not at all, (2) a little/somewhat, (3) moderately, and (4) very/a lot and two open-ended questions. Both surveys were administered by the school leadership team via Google Forms. Staff surveys were sent to all teachers, administrative staff, and ancillary support, and student surveys were sent to all 4th and 5th-grade students. The anonymized data from the 21 staff participants and 180 student participants were then provided to the university research team from the school leadership team. Surveys from staff and students were analyzed using descriptive statistics to determine the frequency of responses (Leavy, 2017).

Qualitative data collection and analysis

A qualitative interview protocol consisting of eight open-ended questions was designed to elicit feedback and reflections related to Peace Project implementation. Three of the four school leadership team members, the principal, the school counselor, and one teacher, agreed to participate in a 30–45-min interview. The interviews were conducted via Zoom based on participant availability, resulting in one individual interview and one interview with two participants. Consistent with IRB requirements, the interviews were preceded by a review of the interview aims, how their responses would be used and shared, and their right to end participation at any time during the process (Leavy, 2017). Participants each signed an informed consent to participate in the research and verbally consented to audio recordings of their interviews for the express purpose of transcription and data analysis. The interview recordings were transcribed using Rev, an online audio transcription service, and transcripts were sent to each participant for member checking and approval before analysis. After an initial reading of each transcription and preliminary notetaking, the interviews were coded in NVivo utilizing grounded theory methods in order to ensure a robust coding process (Birks and Mills, 2015; Charmaz, 2014). Taken together, the data were utilized to detail and assess the Peace Project as a comprehensive pilot case study. These details and analyzes are discussed in the Findings section below.

Findings

The following section provides an overview of the findings of the Peace Project as it unfolded throughout the 2022–2023 academic year. Presented here will be a detailed discussion of aligning existing school programs to the integral peace leadership model and creating two new programs to enhance peace on campus. Each section will also share how students and staff perceive the social validity of each activity. Therefore, each sub-section of this analysis will answer all three of the proposed research questions in an integrated manner.

As aforementioned, the first step of the project was to identify existing peace-related programming and activities at the school and then align them to integral peace leadership practice, which addressed research question one. Table 1 presents a complete overview of each theme, activity, and effort of the Peace Project. This table shows the ways in which the House meetings, Wellness themes, monthly focus, PRIDE theme, peace leadership practices, and Peace Project work progressed over the length of the project. These activities were the basis of the project for the academic year and were the focus of the end-of-the-year surveys and interviews for programmatic assessment, which addressed the second and third research questions.

Identification and alignment of existing programming and activities

The first task of the research team was to identify and organize the existing peace-related programming at the school. Activities and programming already in operation existed in multiple categories: the House system, the PBIS-based PRIDE system, and the district-level Wellness program. The sections that follow detail each of these initiatives and assessment of each by teachers, staff, and students who participated in the surveys.

House system

Developed several years prior to the Peace Project, the House system at the school involves sorting all TK-5 students and all staff into one of four Houses, similar to the popular book series Harry Potter. These Houses serve as a way to create mixed-grade teams in which students spend their whole tenure at the school. The Houses serve to foster relationships across grades, include Big and Little Buddy student mentorship opportunities, and provides spaces for friendly competitions between Houses. In the 2022–2023 school year, the Houses participated in three fundraiser competitions for local organizations, activities for both Peace and Kindness Weeks and a beach clean-up. Houses earn points for their participation in competitions and other school events and activities. Due to the mixed grade connections and the fundraising projects that reach beyond the school, the House system was mapped as supporting both the Community and Environment areas of the integral peace leadership framework.

According to the social validity survey, 61.9% of staff found the House challenges to be very valuable toward promoting prosocial behavior, empathy, relationship building, and stress/anger management in their student populations, while 28.6% found them to be moderately valuable, and 9.5% felt they were somewhat valuable. As one of the school leadership team members stated in their interview, “[Our] House system… helps create community, but we definitely wanted more stuff around mental Wellness, inclusion, things like that. So, [the research team] did a good job of helping us figure out how to theme our months.”

Similarly, 54.1% of surveyed students indicated that they enjoyed the House challenges a lot, 33.1% moderately enjoyed them, and 10.5% somewhat enjoyed them. Only 1.7% of the surveyed students did not enjoy the House challenges at all. Surveyed students expressed their thoughts on the house system and related themes, with one student stating, “The House system is the best. I love spending time with our little buddies and everyone in our House.” In considering improvements related to the House system, one student suggested having “the House meetings [last] longer for the older kids and [have] more stuff in the meetings.” Others recommended “new ways to earn house points” and “have donuts.”

Monthly focus and wellness themes

The monthly focus areas were identified in two ways. First, the PLAG identified common monthly foci in the American public, including awareness days and months, such as Black History Month and Women's History Month. Next, the research team connected with the school counselor to get the list of district-identified Wellness themes. These Wellness themes served not only as overarching ideas for the month but were brought into the classroom through specific monthly lessons taught by the school counselor. Therefore, the awareness months tracked onto the Knowledge and Environment area of the integral peace leadership framework, while the Wellness themes concentrated primarily in the Innerwork and Community areas.

When asked how valuable the school counselor-led Wellness/SEL lessons were toward the promotion of students' prosocial behavior, empathy, relationship building, and stress/anger management, 85.7% of surveyed staff indicated these were very valuable, 9.5% found them to be moderately valuable, and 4.8% stated they were somewhat valuable. One surveyed staff member commented, “I appreciate the monthly lessons in our classrooms and/or the Wellness Space. Students [can] hear relatable scenarios and discuss meaningful topics with strategies and skills to use, which is such a valuable skill set in life.” Another staff member shared, “The Wellness lessons and Wellness Counselor absolutely make the biggest impact.”

Similarly, 55.8% of surveyed students felt the School Counselor-led Wellness/SEL lessons were enjoyable components of Wellness and Peace on campus, 25.2% felt they were moderately enjoyable, and 14.4% somewhat enjoyable. Only 3.9% found them not to be enjoyable. A surveyed student stated, “I appreciate the SEL since it actually relates to a lot of things or problems in life.”

To reinforce the monthly focus and Wellness themes, the monthly school-wide Monday Messages newsletter provided an overview of the peace-related activities taking place on campus and in the community. 33.3% of surveyed staff found the monthly Monday Message with Wellness and Peace initiatives very valuable toward promoting prosocial behavior, empathy, relationship building, and stress/anger management. 33.3% found the Monday Message moderately valuable, 28.6% somewhat valuable, and 4.8% not at all valuable.

During their interviews, the school leadership team members noted that teachers were beginning to incorporate the monthly themes into their curriculum thanks to the school counselor's classroom visits and that students had begun to embody those lessons. As one team leader stated in the interview,

“I know [the school counselor] was really a big spear header for this; she…went into the classrooms and was teaching some of the language and concepts. I see some of the kiddos using some of the language that came out of things that she shared. I think that's a big thing.”

The school leadership team members interviewed felt that the relatability of these monthly activities, readings, and lessons gave students a feeling of inclusion within the school community, where their voices were amplified. One interviewed school leader also stated that the activities, readings, and lessons allowed students to personally relate to the monthly themes, “Finding something that's happening in our schools, whether it's the teachers teaching it or the kids talking about it; that one thing that's like, oh, I can relate to that, or I can take that away.”

PRIDE areas

In establishing itself as a Positive Behavioral Interventions Systems (PBIS) school, the school leadership team created the idea of school PRIDE, which stands for Positive words and actions, Responsibility, Integrity, Displaying kindness, and Earning and giving respect. The school's PRIDE motto encourages students to engage in these behaviors in the classroom, at assemblies, on the playground, and throughout school. Students learn about PRIDE from their teachers, at assemblies, and from signs throughout the school. When students show PRIDE, they receive a special written ticket of commendation, and their House gets points toward ongoing competitions. PRIDE awards are also given out quarterly in each class; therefore, one student in each class earns, per quarter, an award based on one of the areas of PRIDE. For the purposes of this project, the PLAG aligned the school's PRIDE areas with the monthly themes and activities to see where each element of PBIS was found throughout the year. Due to the focus on behavior for the self and for others, the PRIDE area was mapped onto the Innerwork and Community areas of the integral peace leadership framework.

The surveys assessed PRIDE through the existing and new programming conducted as part of the Peace Project. Overall, 57.1% of surveyed staff felt existing and new activities aligned a lot, 33.3% felt they were moderately aligned, and 9.5% felt they were somewhat aligned. Relatedly, 35.9% of surveyed students felt that the existing and new initiatives aligned with the school's pre-existing PRIDE concept a lot, 39.8% felt it moderately aligned, and 21% somewhat aligned. Only 2.8% felt they did not align at all.

Assemblies

Finally, in the work of aligning existing programming and activities, the research team worked with the existing PTA Assemblies Chair to ensure that school-wide assemblies were related to peace themes. This work resulted in two school-wide assemblies. The first was an anti-bullying-themed BMX assembly that had been previously offered and was quite popular with the students and the staff. This assembly was held in October to align with anti-bullying month. As this assembly focused on the behaviors individuals and groups can do to prevent bullying, it was mapped in the Innerwork and Community integral peace leadership areas.

The second assembly was focused on bringing Guide Dogs of America dogs to campus so that students could learn about their work with people with disabilities and also meet the dogs. This assembly grew from December's disability awareness theme, but the guide dogs visited the school in January. With the goal of educating students about people with disabilities, the role of dogs in the care, and the larger role the organization has in disability work, this assembly was mapped on the Knowledge and Environment areas of the integral peace leadership framework.

Of the staff surveyed, 52.4% felt that the BMX assembly was valuable toward promoting students' prosocial behavior, empathy, relationship building, and stress/anger management, while 19% found it moderately valuable, and 28.6% felt it was somewhat valuable. As one of the interviewed school team leaders stated, “We [had] BMX guys come, and they were talking about bullying and things like that, so that was kind of cool.” Of the students surveyed, 66.3% found the BMX assembly to be a very enjoyable Wellness and peace-promoting activity, 18.8% found it to be moderately enjoyable, and 9.4% somewhat enjoyable. Only 5% expressed that it was not at all enjoyable. One surveyed student's suggestion was “To get the BMX people here again to boost up PRIDE.”

Summary of existing programming and activities

Taken together, the program alignment activities set the groundwork for the PLAG to reflect on the areas of integral peace leadership that were already present in the existing activities and programming at the school in order to begin thinking about how to meaningfully integrate new offerings and endeavors of school leadership. The members of the school leadership team who were interviewed believed that intentionally integrating the existing initiatives on campus raised awareness around the current themes of mental wellness, inclusion, and community-building. Peace themes also tied in with off-campus community service projects, reinforcing ideas presented to students on campus. In fact, all areas of integral peace leadership were present through each of the existing initiatives. Innerwork was found in the Wellness themes, PRIDE activities, and Assemblies. Knowledge was found in the Monthly themes and Assemblies. Community was found in the House system, Wellness themes, PRIDE activities, and Assemblies. Finally, Environment was found in the House systems, Monthly themes, and Assemblies.

The school leaders interviewed viewed this building upon current programming as a positive point for staff participation. Rather than overwhelming teachers with completely new programming, it was important to the school leaders interviewed that components of the Peace Project could be infused into their existing workflow. As one interviewed school leader stated, “What we were trying to do is to take those peace opportunities and embed them into stuff that we were already doing, so it didn't feel like a thing that was separate.” Another added, “It felt like something awesome rather than another chore.”

The school leaders interviewed, however, also described a need for more explicit and intentional messaging to promote greater awareness of the connection between Peace Project themes and school activities, especially among the student body. School leaders interviewed expressed that given the school's pre-existing campus community-building activities, it might be difficult for students to differentiate between these and new Peace Project initiatives. As one mentioned, “I don't think the kids really understood when we were setting up the calendar for some of the community service projects. We weren't like, oh, this is tied to peace. I don't feel like we emphasized that.” Therefore, while the overall results of aligning existing programs and activities to the Peace Project goals were positive, there are areas for improvement, particularly in articulating how existing programming and activities connect to the work of peace.

New programming and activities

The second goal of the Peace Project, after identifying and aligning existing programming, was identifying ways that the school could augment its offerings to increase the visibility and actions around peace at the school. The mapping done in the first step indicated that three existing programs and activities were present in the integral peace leadership areas of Innerwork, Community, and Environment, whereas only two existing programs and activities occurred in the integral peace leadership area of Knowledge. Therefore, it became clear that additional enhancement was needed in the Knowledge area. In order to accomplish this, the PLAG decided to create two peace libraries on campus to increase awareness and knowledge around the various areas of peace leadership and peacebuilding. Based on the school leadership team's desire to also enhance further belonging and Community at the school, the Peace Project also initiated a Start with Hello campaign (Sandy Hook Promise, 2024). Both of these initiatives will be described in detail, as well as their visibility and social validity among teachers, staff, and students who participated in the surveys.

Peace libraries and wellness center

The research and school leadership team wanted the ideas of peace and peace leadership to be more readily available for students on campus. To that end, the PLAG developed a list of nearly 60 books that were purchased with the grant funding. These books were appropriate across grades and linked both to peace in general and to the monthly and Wellness themes agreed upon as part of the project. The Peace Libraries were set up in two places: the campus' brand-new district-sponsored Wellness space and the school's existing library and media center. Students were welcome to read any of the books when they were in either space. Each of the books was stamped with a custom Peace Project stamp to identify them as being part of the project. The grant also purchased custom Peace Project pencils to have available for students.

When asked about their awareness of the availability of books ordered for the Peace Libraries on campus, 47% of surveyed staff stated they were very aware, 19% were moderately aware, and 23.8% were somewhat aware. Just 9.5% were not aware at all. Of the staff surveyed, 33.3% found these books made available through the grant to be valuable in promoting students' prosocial behavior, empathy, relationship building, and stress/anger management, 52.4% found them to be moderately valuable, and 14.3% found them to be somewhat valuable.

Of the students surveyed, 29.8% reported being very aware that books about peace, self-confidence, and kindness were available to read in the Wellness Space, 28.7% were moderately aware, and 29.3% were somewhat aware. 11.6% of students surveyed were not aware at all. 14.9% of surveyed students who accessed these peace books found them to be very enjoyable, 32.6% moderately enjoyable, and 33.1% somewhat enjoyable. Of the students surveyed, 18.8% did not find the books to be an enjoyable peace and Wellness activity. One student shared their thoughts on the benefit of reading the books: “I feel like we can read more books in Wellness lessons. It makes me feel relaxed and makes me want to be even more kind to everyone.”

In addition to asking about the Peace Library in the Wellness Center, the survey also asked about the value of the Wellness Center itself, as it was a new space on campus that year and provided an open space for students to come during recess or lunch and take a break, color, read a peace book, or talk to a friend. Of the students surveyed, 54.1% found the Wellness space on campus to be a very enjoyable component of promoting Wellness and peace on campus, 33.1% found it moderately enjoyable, 10.5% found it somewhat enjoyable, and just 1.7% found the Wellness space not at all enjoyable. One student shared, “The Wellness space was a place to calm down, relax, reset and restart.” Another expressed a similar sentiment,

“I think the Wellness room is a great space to just forget everything and hang out if you are having a bad day. I also think [the counselor's] lessons really helped me understand how to act when something or someone makes me mad or stressed.”

When asked about the perceived value of the Wellness space toward promoting prosocial behavior, empathy, relationship building, and stress/anger management in students, 61.9% of surveyed staff found it to be very valuable, 28.6% found it moderately valuable, and 9.5% found the Wellness space to be somewhat valuable.

Intentional environments like the Wellness Center and Peace Library underscored the project themes for students. Along with these physical spaces, the school leaders interviewed mentioned tangible items related to the peace initiatives as valuable in reinforcing concepts taught in the classroom. They shared that staff used the Peace Library literature during read-aloud activities and as recommendations for future student reading. As one school leader stated during their interview,

“When [the school counselor] would come in and do her activities or lessons, she would start with the book, and it was nice for the kids to know, if you want to look at this book again, we have the library in the Wellness Center. I would see the kids actually going to seek out those books. It was nice to have a tangible item instead of just an experience.”

Further, the peace literature was effective in expanding students' worldviews by introducing them to stories about people outside of their typical interests. These books often served as vehicles for ongoing discussion. One interviewed school team leader said,

“There was this whole conversation about, yes, as a fourth-grade boy, you can read books about women. That's okay. It was very interesting, something that I would've never thought would've started a conversation. I never even thought a kid would've thought twice about reading a book about Amelia Earhart, but it caused this huge ruckus for a couple days. It was a cool conversation for me to have with them and the teacher ended up following up with it too. You can read books about whatever you want. It doesn't mean anything. Just read books about amazing people.”

When reflecting on the Peace Library, the school leaders interviewed suggested that offering more tangible items, like the newly offered peace-themed pencils, would be effective in garnering student interest in attending peace-related activities and events. As one put it,

“I think more kids come to activities when they get something out of it, and then in the end, the hope is that they're getting a lot more out of it than the pencil, but they show up because of the pencil.”

Start with Hello

The school also decided to begin its own Start with Hello campaign. Started by Sandy Hook Promise, which emerged from the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, this campaign exists to bring kindness to school campuses and make people feel included and welcome (Sandy Hook Promise, 2024). This project promotes kindness and a welcoming nature by ensuring that students are greeted on Start with Hello days by staff and students wearing Start with Hello shirts and welcoming them to campus with something as simple as hello.

The grant allowed the team to purchase Start with Hello t-shirts for all of the school's teachers, staff, and administrators and began implementing a Start with Hello day on the first Monday of each month. The PTA also facilitated the purchase of t-shirts for any students wishing to also wear a shirt on Start with Hello days. The PTA had over 100 shirts purchased during this first year. In order to increase the profile of the Start with Hello day, grant funds were also used to purchase large yard signs that were placed throughout the school. As one of the school leaders reflected in their interview,

“This year we bought lots of yard signs, and even parents, [would] be like, ‘did you say hello? Make sure to say hello.' So, they're catching on. That one tiny thing can really impact the kid next to you without costing any money.”

Of the staff surveyed, 61.9% assessed the Start with Hello campaign as very valuable to the promotion of students' prosocial behavior, empathy, relationship building, and stress/anger management; 19% found it moderately valuable; and 19% somewhat valuable. One of the school leaders, through their interview, shared that,

“I feel like it is supporting every student because what's happening is little by little, as the teachers are catching onto it, they're going out of their way to say to the kids in the morning, why am I wearing this shirt? What is it all about? You can say hi to somebody and have no idea what that kid is going through… by simply saying, you can be my friend today, and someone cares about you could change everything.”

In addition to the staff, 36.5% of surveyed students expressed that the Start with Hello campaign was an enjoyable activity for promoting Wellness and peace on campus, 32.6% found it moderately enjoyable, and 22.7% somewhat enjoyable. Only 7.7% of the students surveyed found it not enjoyable at all. Surveyed students commented on the positive impacts of the Start with Hello campaign: “I feel like the Start with Hello will help new students feel more confident in themselves.” “This could help a lot of kids who need that hello.”

Perceptions on the Peace Project as a whole

Perceptions on the number of peace-related activities that took place over the 2022–2023 school year, 42.9% of surveyed staff stated that the amount of Peace Project activities and materials was very appropriate, 47.6% said the amount was moderately appropriate, and 9.5% reported the amount as somewhat appropriate for the school year. Further, 36.5% of surveyed students reported that these activities increased their awareness of peacebuilding on campus a lot, 38.1% reported a moderate increase in awareness, 16.6% stated that the activities somewhat increased their awareness, and 8.3% reported no increase in awareness. Overall, the school leaders interviewed agreed with the survey results, felt the Peace Project had a positive impact on the campus community, and are hopeful that these effects will continue to grow. As one stated,

“If we can keep teaching that kindness piece [to students] and we can see that [kindness is] happening or somebody stepping in saying, hey dude, calm down, that's not kind, then I think it's a win. Even if it's five kids, those five kids are going to impact five kids next year and five kids the next year. It's that ripple effect.”

When reflecting on observed program impacts, the school leaders interviewed mentioned observing increased mindfulness, respect for others, acceptance and celebration of differences, and broader perspective-taking in the student body. Moreover, one team leader stated during their interview that the project exposed students to perspectives that might differ from what they have learned in the home, influencing new ways to interact with others. She said,

“Sometimes, unfortunately, they're learning things that just aren't appropriate, or it's just their home structure and what they're being told. In a way, it's not their fault at this age because they don't know any different. I think it's just learning that it's okay to be different and to not put other people down when something isn't like what they're used to or what they deem as normal.”

Aligned with this reflection, when asked about the impact of the year's wellness instruction and peace-related activities, 42.9% of surveyed staff felt it was very helpful toward creating and/or maintaining a campus environment of diversity, equity, and inclusion, 23.8% felt it was moderately helpful, and 33.3% felt it was somewhat helpful. Of the students surveyed, 40.3% reported the year's instruction and activities as very helpful in creating or maintaining a campus environment that promoted kindness, being an upstander, inclusion, diversity, and peace; 37.6% found it moderately helpful; and 17.7% somewhat helpful. Only 3.9% of surveyed students found it not helpful at all.

When reflecting on how the Peace Project might be improved in the future, one school leader shared that including more people in the decision-making process would provide opportunities for feedback from teachers who are representative of a broader range of grades, closing the gap in programming needs for students from kindergarten to 5th. Additionally, this school leader stated that consulting additional stakeholders during the project's implementation process would add meaning to the project for everyone involved and increase overall understanding of the project's aims and impacts: “I think if there's more people involved and they understand the philosophy behind it and why decisions were made, I think that's going to help and create that change.”

The school leaders interviewed also cited flexibility as both a positive aspect of the project and a challenge. They discussed challenges with balancing the autonomy provided to the school staff in selecting activities for their students, with a desire for more explicit guidance on what the research team envisioned for the project overall. The timing of the Peace Project also coincided with leadership staffing changes at the school site. As one leader stated,

“I was trying to get to know this campus and what it's all about and get the vibe of the teachers and the staff. So, we appreciated the freedom [the research team] gave us to be able to say what's going to be best for this site rather than [being prescriptive].”

When asked about additional ideas for potential future Peace Project activities, one school leader interviewed shared that focusing on student leadership would be beneficial in cultivating a positive campus climate. She stated,

“Having resources to teach [the students] how to be leaders, to take initiative and help with conflicts that they're seeing on the yard because they're really in the trenches and they see things and know things that are happening more than we do.”

The findings presented in this section demonstrate that, as a whole, the Peace Project was successful in aligning existing programs under the lens of peace and building new projects and activities to augment that work. Survey respondents and the school leadership team were able to share the impact of this work on the campus culture and share ideas for improvements in the future. These findings will be discussed in detail in the next section.

Discussion and implications

Using a PLAG approach, this single case pilot study utilized an integral peace leadership framework to integrate existing school programs and activities with new offerings through the collaborative work of a team of university researchers and elementary school leaders. The broader goals of this work, ultimately, were to examine and augment the school's existing school climate efforts around peace. These efforts were examined through observational data of the planning and implementation processes and interviews and survey data gathered to gauge the social validity perceptions of staff and student stakeholders. This data were collected with the aim of answering the study research questions, and findings will be discussed in terms of research questions in the sections that follow.

Examination of multiple types and sources of data provided a rich perspective into how multiple school climate initiatives that typically function in isolation can be meaningfully connected and integrated around a common purpose, which was identified as peacebuilding in the current case study. Utilizing integral peace leadership tenets and practices allowed the PLAG to systematically examine, integrate, and enhance the school's peacebuilding structures for greater visibility and intentionality across multiple stakeholders. This case study demonstrates how integral peace leadership can serve as an organizational framework to support and strengthen existing peacebuilding potential as an alternative to the initiative overload and fatigue that many educators experience (McIntyre Miller and Abdou, 2018). These findings will now be further discussed by research question.

Intentionally identifying peace

The school's current peace-related practices were identified and aligned with integral peace leadership as an initial step in the development of the Peace Project, addressing the study's first question: How might an elementary school align existing practices to be more focused on peacebuilding? Existing programming included in the project was the House system, district-wide Wellness programming, and the PBIS-based PRIDE system.

The House system

The House system provided opportunities for students to work as part of a team while engaging in community service, fundraising, and peer buddy pairing. Both staff and students indicated positive perceptions of the House system, citing community building, promotion of prosocial behavior, and opportunities for peer socialization as beneficial to promoting peace on campus. The House system survey outcomes align with the integral peace leadership framework areas of Innerwork, demonstrated by the perceived increase of the students' pro-social behavior, Community through the community-building activities of the House system, and Environment with opportunities for networking and peer socialization via buddy pairing.

Additionally, the characteristics of the House system align with the social-emotional learning (SEL) and school-wide positive behavior support (SWPBS) frameworks identified in the literature as key to creating and maintaining peaceful schools and communities (Greenberg, 2023; Santiago-Rosario et al., 2023). Therefore, the idea of providing a space outside of typical classroom organization where children can meet, get to know each other, and work together on community-based projects was seen to practice social-emotional skills, thus enhancing a culture of peace at the school.

Monthly and Wellness themes

Existing Wellness monthly themes were aligned with integral peace leadership components, incorporated into classroom curriculum and activities, and delivered by the school's Wellness counselor. Wellness themes included bullying, mindfulness, and making connections. Additionally, monthly themes mirroring current subjects prominent in American society, such as Indigenous People's Month, Black History Month, and Disability Awareness Month, were added to the existing monthly foci and served as overarching themes for activities. Also, the school's PRIDE areas were aligned with each monthly theme, underscoring activities and programming.

In tandem, the monthly themes and foci were perceived by staff as contributing to feelings of inclusion and community among the student body, with students exemplifying concepts and language used in Wellness counselor-led lessons. Furthermore, staff and students reported that new programming aligned with the school's PRIDE areas and promoted a positive campus environment. Therefore, the findings reveal that having a focus on programming each month allows both staff and students to make connections between what is happening at the school and their overall learning and make connections to how this aligns with peace, drawing attention to the value of difference (Levine and Tamburrino, 2014).

These practices aligned with Innerwork of integral peace leadership in that students were learning more about themselves and in the Community area, as they were learning more about others and doing so in interactive, connected spaces. The lessons provided by the Wellness Counselor did enhance Knowledge practices for students but were only offered in the classrooms once a month. Providing the opportunity to organize existing programming around these themes makes the work at the school around peace clearer to those in the school community. Being intentional in naming the work and organizing it around key themes was helpful in creating that sense of awareness across the school. It is important to note, however, that the Monday Messages, intended to notify the larger school community of these themes, was seen as one of the least useful tools, and therefore, finding new and innovative ways to communicate monthly themes may help strengthen the connections between monthly foci and the Peace Project overall.

Integrating peace programming and practices

Interview and survey data spoke to the programs, activities, and supporting materials that brought a peace focus to the campus and addressed the second study question: How might an elementary school use the integral peace leadership framework to augment existing programs to be more inclusive of peace practices and activities at the school? After understanding and aligning existing programming, the PLAG utilized the principles and practices of integral peace leadership to determine what areas of programming might be augmented to ensure that all areas of peace leadership were being developed at the school. The Knowledge area was identified as a key area with limited existing work, as students were introduced to key learning concepts just once a month. To address this, the PLAG added two Peace Libraries and included pencils and a book stamp to remind students of these spaces and their connection to the school's peace work.

One of the other goals of the school was to further a sense of a peaceful community, even though Community practices were being addressed in various existing offerings. Therefore, the second programmatic effort raised by utilizing integral peace leadership as a framework for the campus was the Start with Hello campaign initiative, including t-shirts and yard signs. These efforts helped to build both Innerwork practices, with goals of helping students feel more included and welcomed on campus, and Community by creating one day a month where everyone worked together to ensure every person on campus was welcomed and felt they belonged. Surveyed staff and students indicated that these efforts increased awareness of peacebuilding on campus, which, as the literature shows, is key to addressing violence and building peaceful school campuses (Bickmore, 2011a,b).

A recurring theme of inclusion emerged from staff survey comments and interviews related to acceptance of differences, kindness, and anti-bullying. Additionally, an expressed desire to highlight diversity, equity, and inclusion in curriculum, instruction, and materials was echoed by several staff members. This reflects the need for appreciation of differences (Levine and Tamburrino, 2014) and ways to facilitate interpersonal and intergroup growth (Sagkal et al., 2012). The inclusion of the Peace Libraries and Start with Hello campaign were an effort to build programming around these areas. Results showed that this was successful overall but that there was a desire to continue building on the newly integrated peace practices by increasing the availability of materials and greater frequency of activities on campus. Utilizing the integral peace leadership framework proved to be a valuable tool to ensure that programming is diverse and intentionally addresses the need to bring ideas of peace to an elementary school campus.

Stakeholder experiences

Upon concluding the 2022–2023 school year, staff and students reflected on their experiences with the Peace Project, from the initial assessment of existing campus Wellness practices to the alignment of existing practices with peace-focused activities and, finally, the implementation of new programs. The end-of-the-year survey and school leadership team interviews served to answer the third research question: How do the students and staff perceive the social validity of the project's peace practices and activities?

Quantitative analysis presented generally positive staff and student responses to the Peace Project, with qualitative data revealing a further desire for collaboration as a significant theme. Staff conveyed recognition of the connections between Peace Project efforts and positive behavioral outcomes, for example, highlighting the monthly Wellness SEL lessons in classrooms as a platform for meaningful discussions and a vehicle for promoting crucial life skills. Similarly, students described multiple benefits experienced because of the Peace Project, including increased knowledge about peers, learning self-love and kindness toward others, regulating anger and stress through mindfulness, and ensuring all students feel acknowledged and connected, each of which aligned with the peacebuilding (Bickmore, 2011a), positive support behavioral support systems (Santiago-Rosario et al., 2023) and SEL (Greenberg, 2023) literature. The increase in positive actions toward others helps challenge the bullying climate in schools (Bickmore, 2011b; Levine and Tamburrino, 2014; Sagkal et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2005).

The expressed desire for cooperative change-making efforts was articulated through suggestions to consult with multiple stakeholder groups to ascertain learning needs, requests for increased communication about new activities, initiatives, and materials toward increasing awareness of the Peace Project aims, and relationship-building among stakeholders. As the Peace Project moves forward out of the pilot stage, it would be beneficial to expand the leadership team and ensure that even more voices share thoughts and ideas about program needs. Involving a greater number of stakeholders expands both the Community space of the work and ensures that the variety of system and structure representatives at the school, as seen through an Environment lens, are included.

Limitations and implications for future research

This pilot case study was conducted with one elementary school in Southern California. During the study, one of the leadership team members was new to the school, and another took a medical leave during part of the school year. Therefore, some challenges may not have been present with a well-established and consistently present team. Despite these challenges, the team was supportive of the research, and the research team made themselves available to ensure all planned events and activities occurred. Also, as seen from the demographic information, this school does not face some of the challenges that other schools with more diverse populations and socioeconomic status may face. This potentially made implementation and stakeholder engagement easier than in other cases.

As the school moves into its second year of the Peace Project, it will be interesting to understand what programs and ideas introduced to the school, such as the Peace Library and the Start with Hello campaign, remain a part of regular programming and which ideas and activities might change or be re-envisioned. Therefore, taking a longitudinal approach to understanding the Peace Project at this school would be an interesting way to understand the potentially lasting effects of implementing programming with an integral peace leadership lens to influence elementary school culture. As this programming continues to evolve, evaluating its impact using formal school climate assessments, such as the California Healthy Kids Survey (2024) and companion measures, will be an important future direction of this work to examine the effectiveness of this type of peace education initiative. It would be interesting, as well, to understand how integral peace leadership alignment and programming work at other schools in various settings and with various demographics. We hope that others might expand this work to bring strong, peaceful cultures and climates to our schools.

Conclusion

This pilot case study was a chance to understand how integral peace leadership could be utilized to understand existing elementary school peace programming and how that programming might be enhanced to bring a better culture of peace to a school campus. Working collectively with the school leadership team, the university research team helped to align existing programming and explore and implement new programming to create a comprehensive plan for bringing peace ideas together at the elementary school level. Both staff and students found the efforts to build peace on campus to be, overall, successful and a positive experience. There was increased understanding and a sense of peace and peacebuilding on campus. While this is an initial pilot case study, the findings indicate that aligning existing programming to frame a culture of peace and then supplementing that programming with additional activities can unite a campus around the idea of peace.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Chapman University Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

WM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CC: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Chapman University funded this project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^This project was funded by Chapman University Attallah College of Educational Studies Solutions Grant.

2. ^IRB Approval number 23-9 from Chapman University.

References

Abdou, A. S., Brady, J., Griffiths, A. J., Burrola, A., and Vue, J. (2023). Restorative schools: a consultation case study for moving from theory to practice. J. Educ. Psychol. Consultat. 33, 1–28. doi: 10.1080/10474412.2023.2192205

Amaladas, S. (2018). “The intentional leadership of Mohandas Gandhi,” in Peace Leadership: The Quest for Connectedness, eds. S. Amaladas, and S. Byrne (London: Routledge), 46–61.

Bajaj, M. (2019). Conceptualising critical peace education for conflict settings. Educ. Conflict Rev. 2, 65–69.

Bayard, A. (2022). “We must talk before we walk: a pathway to reconciliation on the journey to positive peace,” in Evolution of Peace Leadership and Practical Implications, eds. E. Schellhammer (Hershey: IGI Publishing), 78–100.

Bickmore, K. (2011b). Policies and programming for safer schools: Are ‘anti-bullying' approaches impeding education for peacebuilding? Educ. Policy 25, 648–687. doi: 10.1177/0895904810374849

Birks, M., and Mills, J. (2015). Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Bradshaw, C. P., Cohen, J., Espelage, D. L., and Nation, M. (2021). Addressing school safety through comprehensive school climate approaches. School Psychol. Rev. 50, 221–236. doi: 10.1080/2372966X.2021.1926321

California Department of Education (2023). School Performance Overview: Rossmoor Elementary. California: California School Dashboard. Available at: https://www.caschooldashboard.org/reports/30739246029086/2023

California Healthy Kids Survey (2024). The Surveys. Available at: https://calschls.org/about/the-surveys/

Chinn, P. L., and Falk-Rafael, A. (2018). “Critical caring as a requisite for peace leadership,” in Peace Leadership: The Quest for Connectedness, eds. S. Amaladas, & S. Byrne (London: Routledge), 195–211. doi: 10.4324/9781315642680-13

Cremin, H., and Guilherme, A. (2016). Violence in schools: perspectives (and hope) from Galtung and Buber. Educ. Philos. Theory 48, 1123–1137. doi: 10.1080/00131857.2015.1102038

Dinan, A. (2018). “Conscious peace leadership: examining the leadership of Mandela and Sri Aurobindo,” in Peace Leadership: The Quest for Connectedness, eds. S. Amaladas, and S. Byrne (London: Routledge), 107–121.

Fountain, S. (1999). “Peace education in UNICEF (Working Paper),” in UNICEF Programme Division. Available at: https://inee.org/sites/default/files/resources/UNICEF_Peace_Education_1999_en_0.pdf

Fraguas, D., Díaz-Caneja, C. M., Ayora, M., et al. (2021). Assessment of school anti-bullying interventions: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Pediatr.175, 44–55. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3541

Gallegos-Guajardo, J., Ruvalcaba-Romero, N. A., Garza-Tamez, M., and Villegas-Guinea, D. (2013). Social validity evaluation of the FRIENDS for Life program with Mexican children. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 1, 158–169. doi: 10.11114/jets.v1i1.90

Greenberg, M. T. (2023). Evidence for Social and Emotional Learning in Schools. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

Greenwood, D. J., Whyte, W. F., and Harkavy, I. (1993). Participatory action research as a process and as a goal. Hum. Relat. 46, 175–192. doi: 10.1177/001872679304600203

Guadalupe, A. T., Martínez Basurto, L. M., Lozada Garcia, R., and Ordaz, V. G. (2015). Social validity by parents of special education programs based on the ecological risk/resilience model. Acta Colombiana de Psicología 18, 151–161. doi: 10.14718/ACP.2015.18.2.13

Huntington, R. N., Badgett, N. M., Rosenberg, N. E., Greeny, K., Bravo, A., Bristol, R. M., et al. (2022). Social validity in behavioral research: a selective review. Perspect. Behav. Sci. 46, 201–215. doi: 10.1007/s40614-022-00364-9

Kidd, S. A., and Kral, M. J. (2005). Practicing participatory action research. J. Couns. Psychol. 52, 187–195. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.187

La Salle, T. P. (2018). International perspectives of school climate. Sch. Psychol. Int. 39, 559–567. doi: 10.1177/0143034318808336

Leavy, P. (2017). Research Design: Quantitative, Qualitative, Mixed Methods, Arts-Based, and Community-Based Participatory Research Approaches. New York, NY: Guilford Press. doi: 10.1111/fcsr.12276

Ledbetter, B. (2012). Dialectics of leadership for peace: toward a moral model of resistance. J. Leaders. Account. Ethics 9, 1–24.

Levine, E., and Tamburrino, M. (2014). Bullying among young children: strategies for prevention. Early Childhood Educ. J. 42, 71–278. doi: 10.1007/s10643-013-0600-y

Marshall, C., Rossman, G. B., and Blanco, G. L. (2022). Designing Qualitative Research (7th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

McIntyre Miller, W. (2016). Toward a scholarship of peace leadership. Int. J. Public Leadersh. 12, 216–226. doi: 10.1108/IJPL-04-2016-0013

McIntyre Miller, W., and Abdou, A. (2018). Cultivating a professional culture of peace and inclusion: conceptualizing practical applications of peace leadership in schools. Front. Educ. 53:56 doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00056

McIntyre Miller, W., and Alomair, M. O. (2022). Understanding integral peace leadership in practice: lessons and learnings from women peacemaker narratives. Peace Conflict: J. Peace Psychol. 28, 437–448. doi: 10.1037/pac0000618

McIntyre Miller, W., and Green, Z. G. (2015). “An integral perspective of peace leadership,” in Integral Leadership Review, 15. Available at: http://integralleadershipreview.com/12903-47-an-integral-perspective-of-peace-leadership/

McIntyre Miller, W., Hilt, L., Atwi, R., and Irwin, N. (2024). Developing peace leadership in community spaces: lessons from the Peace Practice Alliance. J. Peace Educ. 1–28. doi: 10.1080/17400201.2024.2399093