- 1Institute for Culture and Society, Western Sydney University, Parramatta, NSW, Australia

- 2Menzies School of Health Research, Charles Darwin University, Alice Springs, NT, Australia

- 3Australian Institute of Tropical Health and Medicine, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD, Australia

- 4Centre for Alcohol Policy Research, La Trobe University, Bundoora, VIC, Australia

- 5Synapse Australia, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 6College of Healthcare Sciences, James Cook University, Cairns, QLD, Australia

- 7Menzies Health Institute Queensland, Griffith University, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 8Australian Red Cross, Townsville, QLD, Australia

- 9Justice Galbidera Way, Elders for Change, Townsville, QLD, Australia

Introduction: A majority of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in correctional centers report prior experience of traumatic brain injury (TBI) from assault. TBI education in settings outside correctional centers, such as health settings, is shown to help people living with TBI implement strategies for symptom management. The aim of this study was to understand and identify what impacts TBI education would have for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in correctional centers in Australia.

Methods: In August 2023, two Aboriginal facilitators from a national brain injury organization delivered workshops on brain injury, with a primary focus on TBI, to 15 women involved in a peer-mentor support group (Sisters for Change) at one regional correctional center in Queensland (Australia). TBI resource packages were also shared with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women at the correctional center with lived experience of TBI from family violence. Nine semi-structured interviews were conducted with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who attended the workshops and/or received the TBI information resource packages. Thematic analysis was conducted on interview transcripts as well as the written notes recorded from the workshops.

Results: The workshops supported women to develop a deeper understanding of brain anatomy, impacts of physical violence on brain function and how TBI appears in everyday life, both inside a correctional center and in the community. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women reported gaining deeper insight into, and greater compassion for, themselves and other women at the correctional center who have histories of family violence.

Conclusion: The findings underscore the need for greater consideration of how TBI education and screening pathways can contribute to the provision of appropriate and responsive supports for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in correctional centers and subsequent to their release from the correctional center.

1 Introduction

This paper is dedicated to Sisters for Change – for their leadership and advocacy to address the needs of women experiencing imprisonment

In Australia, efforts to reduce the numbers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults coming into contact with the criminal justice system is of national importance. Under the Closing the Gap Agreement, the reduction of at least 15 percent in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults experiencing imprisonment by 2031 is a key target (Australian Government, 2020). Despite this ideal, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are the fastest growing prison population in Australia (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2020). At present, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are 35 times more likely than other Australian women to experience imprisonment (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2019). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women make up about 34 percent of incarcerated women in Australia, yet only account for 3% of the national population. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women experiencing imprisonment are more often mothers and primary carers of children compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts (Australian Law Reform Commission, 2017). Therefore, imprisonment increasingly separates Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers from their children, and has lifelong consequences for families.

The overrepresentation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in Australian correctional centers is an outcome of colonial invasion and dispossession, frontier violence, and historical government child removal policies (Atkinson, 2002; Kilroy et al., 2023). In studies that examine the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women experiencing imprisonment, it has been identified common themes within women’s life histories present a collective story of trauma (Bevis et al., 2020). A combination of contact with the child protection system as children, layered loss and grief, mental illness, harmful drug and alcohol use, homelessness or unstable housing, as well as family and sexual violence have often occurred in the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women by the time they come into contact with the correctional system (Australian Law Reform Commission, 2017; Baldry et al., 2015; Bevis et al., 2020; Sullivan et al., 2019). Physical violence is also often a leading factor for the contact Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women have with the criminal justice system. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are being misidentified as the primary perpetrator, leading to their criminalization as well as using violence as self-defense or retaliation—otherwise known as violent resistance (Nancarrow, 2019; Boxall et al., 2020).

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is caused through blunt force trauma to the head, face, or neck (Menon et al., 2010) and is highly prevalent among women who intersect with the correctional system (McGinley and McMillan, 2019). Physical violence is a major cause of TBI experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women (Jamieson et al., 2008; Pointer et al., 2019) and often has lifelong consequences including changes in cognitive functioning (e.g., executive functioning, attention, memory) and somatic symptoms (e.g., headaches, fatigue) (Langlois et al., 2006). Despite this, little is known about the potential impact of TBI on the everyday lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women managing life in a correctional center (Costello and Greenwald, 2022; Lakhani et al., 2017).

1.1 Identifying and responding to traumatic brain injury in women’s correctional centers

Globally, responding to the needs of people living with disability has become a priority area in correctional systems. While it is promising that disability is growing in visibility within correctional frameworks, there is much to be done to include TBI within the formation of correctional programs, policies and processes. A review of rehabilitation programs in correctional centers found TBI is rarely considered or acknowledged, and programs are usually not modified to reflect the needs of people living with the symptoms of this serious injury (Chan et al., 2023). In Australia, identification of people with TBI experiencing imprisonment can be complicated by a lack of systematic screening protocols used in correctional centers (O’Brien, 2022). The absence of screening protocols in the correctional centers generally as well as culturally appropriate screening tools can lead to misdiagnosis, delayed medical treatment and disability supports, and the implementation of unreasonable and punitive responses to TBI symptoms (Baldry and Cunneen, 2014; Brain Injury Australia, 2018; O’Brien, 2022). Lack of knowledge and awareness among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and frontline workers, including correctional staff; lack of access to healthcare and specialists outside of urban settings; fear of child removal by authorities after reporting violence; and coercive control and ongoing risks of further violence also contribute to lack of diagnosis for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women (Fitts et al., 2022; Fitts et al., 2023a; Haag et al., 2019). Failure to consider TBI in correctional practice can compromise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women’s access to specialized supports to improve their quality of life and long-term outcomes.

In Australia, justice liaison officers through the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) are employed to help people with disability access the supports they require while they are in custody and when transitioning back to the community. They also provide education and promote a best-practice approach (Disability Royal Commission, 2021; Yates et al., 2022). Globally, there are also examples of specialized TBI support roles to deliver person-centered rehabilitation and sustainable pathways of support across health, probation and homeless services to help women manage the transition between correctional center and community (Glorney et al., 2018; Ramos et al., 2018).

1.2 Education in correctional spaces

Health education delivery is shown to have numerous important benefits for women in correctional centers (Glorney et al., 2018). Initiatives where people in correctional centers provide education, support, or advice to people in education delivery, are an acceptable source of support within the correctional environment and have been shown to have a positive impact on their participants (Bagnall et al., 2015). When women who are incarcerated are permitted to co-design programs with others (e.g., researchers), programs are more likely to improve perceptions of legitimacy, relevancy and participant buy-in (McKenzie and Wright, 2023). Reviews have also found that peer-led correctional center initiatives have resulted in the reduction of incidents between people experiencing prison and staff in correctional centers.

1.3 Background to the study and study aim

This study forms part of a larger three-year Australian Research Council (ARC) project (DE210100639) which aims to explore how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women live with TBI from violence and how they rebuild their life and identity after the injury (Fitts et al., 2023b). This project was focused on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women to address the gaps in understanding their experiences of violence-related TBI, which is a significant gap in research that could be used to inform service delivery and practice (Costello and Greenwald, 2022). During the implementation of the larger project, women’s groups, service providers and community groups supporting the existing ARC project recommended the research team extend the project to include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women experiencing imprisonment. The research team added women’s correctional centers to directly respond to this recommendation.

At the outset of the community-based component of the larger project in 2021, the research team adapted the methodology based on feedback collected from Elders, women groups and frontline services to deliver TBI education workshops prior to formal data collection to increase low levels of knowledge and awareness of the connection between violence and TBI (Fitts et al., 2023c). Frontline community-based services nominated to promote the project to clients who met project criteria also recommended TBI education workshops to increase staff confidence and skills to discuss TBI. Drawing on this same approach, TBI workshops were delivered by Aboriginal facilitators from Synapse Australia, a national brain injury organization, over 3 days, prior to the commencement of interviews with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women at the correctional center. Sisters for Change, Elders for Change and Australian Red Cross supported the wider promotion of the project to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women at the correctional center in the Australian jurisdiction of Queensland (including authors RM and AGD).

Sisters for Change are a group of women experiencing imprisonment who are trained, supported and resourced to be peer educators, peer supports and project leaders. With 3 collaborative partnerships with the prison leadership and management teams, Sisters for Change advocate to improve health, wellbeing and safety of the prison community. Sisters for Change has implemented a range of health and wellbeing initiatives and contributed to government reviews including the review of policies, procedures and practices related to strip searching of women in Queensland prisons (Queensland Government, 2023). Sisters for Change are supported by Elders for Change and Australian Red Cross. Elders for Change, a group of local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elders, support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in contact with the court and prison systems in north Queensland as well as speak up to provide knowledge on changes required within these systems. Elders play a significant role in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities through the provision of providing guidance, wisdom, emotional wellbeing and maintaining community wellbeing (Busija et al., 2020). The aim of the study was to understand the impact of TBI knowledge-sharing with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who attended TBI workshops or received TBI resource packages.

2 Methodology

2.1 Study design and setting

This qualitative study collected information and feedback from the TBI workshops and resources through two pathways: (i) discussion with members of Sisters for Change who attended the workshops, and, (ii) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who participated in interviews for the wider research project (Fitts et al., 2023a). The study has ethics approval from the Townsville Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/QTHS/88044) and the Queensland Corrective Services research committee. In alignment with national research guidelines on working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, 2020), the larger project was guided by an advisory group consisting of almost all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women working in service delivery and advocacy roles.

2.2 Positionality statement

As researcher positioning is an essential component to conducting reflexive, ethical and quality research, the authors embedded within the research process describe their worldview and positionality (Creswell, 2014; Kennedy et al., 2022).

2.2.1 Michelle Fitts

Michelle (she/her) is a white settler and academic. She acknowledges the unearned privilege settler colonial systems and structures have afforded her and recognizes that such systems continue to maintain the power inequities between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and white settlers. Michelle is committed to supporting platforms to elevate the voices of marginalized women in research translation, policy and practice.

2.2.2 Jennifer Cullen

Jennifer is a Bidjara and Wakka Wakka woman, who holds a national and international professional profile in disability advocacy. She has worked in disability and aged care services for over three decades, is a member of the National Disability Insurance Agency’s Independent Advisory Council and is involved in a suite of research projects on complex neurocognitive disabilities, including fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) in both the community and justice settings.

2.2.3 Rachel Montgomery

Rachel was born on the lands of the Yaburara and Ngarluma peoples in Western Australia to an English dad and Pakeha mum. She grew up on the lands of Bindal and Wulgurukaba peoples in North Queensland. Her foundations for practice were informed from formal education in psychology, international and community development as well as two-decades of working in North Queensland with knowledge holders at the grass roots shaping local solutions to community needs. Rachel recognizes the power of education, inquiry and learning in transforming oppressive structures and systems in society and seeks to create opportunities for collaboration that can create transformative social justice.

2.2.4 Aunty Glenda Duffy

Aunty Glenda is a Kalkadoon Waayni woman from Northwest Queensland and the Gulf of Carpentaria Region who was raised in rural towns Cloncurry and Mount Isa and has lived in Townsville for over two decades. She has worked for 25 years in community engagement, community development and community capacity building in Aboriginal communities. With a passion for building equity for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, Aunty Glenda’s work in communities has been in the areas of community development, childcare, homelessness and community engagement protocols. She has worked extensively in both Australian and State Government agencies as well as non-government organizations.

2.3 Traumatic brain injury workshops

The workshop content was informed by existing resources Synapse Australia had developed for Aboriginal and Torres Strait communities and services working in regional and remote locations. The content of the workshops covered information about the brain, the psychological, behavioral, physical and cognitive changes that can occur with TBI, including non-fatal strangulation, and strategies to manage TBI symptoms. The content also included other forms of acquired brain injury (ABI) including FASD, drug and alcohol misuse, and stroke. As the larger research project had a focus on TBI from violence, the facilitators (including author JC) drew on case examples from work Synapse Australia had participated in with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who had experienced a TBI from family violence. All participants received hard copies of the workshop slides and TBI information booklets. The workshops were open to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous members of Sisters for Change.

2.4 Project participant criteria and recruitment

Within the workshops and prior to each interview, all members of Sisters for Change received the project flipchart that provided information in plain English about the project and its background, their role and rights as participants (including the right to withdraw from the project), how the data from their interview would be used (e.g., anonymized quotes in reports), and the potential outcomes from the project. All members from Sisters for Change also viewed two short videos in the workshops. The first video provided information about the project. The second video shared the journey of recovery after violence-related TBI from the perspective of one Aboriginal woman (Bohanna et al., 2019).

As the larger research project was focused on the experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, only Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander members of Sisters for Change were able to self-nominate to participate in an interview for the larger research project (Fitts et al., 2023a). To participate in an interview, women were required to: (1) identify as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander; (2) be aged 18+; and (3) have experienced TBI sustained from family violence. There is not one consistent definition used to define a TBI. The inclusion criteria for the project are therefore broad to include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who have experienced different TBI severity levels including an injury severe enough to cause neurological symptoms (including sensitivity to light, headache, and nausea), loss of consciousness, post-traumatic amnesia or an injury verified on a computerized tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The broad criteria also account for low levels of TBI diagnosis and reduced accessibility to health care and specialist services following a TBI for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women living in regional and remote communities (Fitts et al., 2022). Following the workshops, peer-support members from Sisters for Change disseminated information packs including the slides, information booklets as well as the research project flipchart to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women at the correctional center about TBI and the research project. Sisters for Change members spoke to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women at the correctional centre over multiple meetings to discuss the content of the slides and information. All participants received a participant information sheet and provided written consent.

2.5 Data collection

In total, nine women participated in face-to-face semi-structured interviews. Of the nine interview participants, six Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women attended the workshops. A further three Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women received the information resources. Each woman completed multiple interview meetings with at least one member of the research team (including author MF). This was to accommodate the effects of cognitive fatigue associated with TBI, as well as enable each woman to review and revise interview transcripts and written notes recorded in earlier meetings and expand further on earlier topics or explore new topics. The semi-structured interview schedule asked Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women about living with TBI from violence, their experiences accessing healthcare and community-based services to address their needs related to TBI and family violence, their views on the TBI workshop, as well as recommendations for improving services in the community and correctional-center settings for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women living with TBI caused through violence. The interview guide included non-standardized prompts to provide clarification of the emerging concepts in the interviews (Patton, 1990). The majority of interviews were conducted by the in a private room in the education building of the correctional center. A small number of interviews were conducted in a private room at the visitors’ center. Individual interview meetings with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women ranged in time between 30 and 120 min. The way interviews were recorded was determined by participant preference: some were recorded using a voice recorder and written notes, and others were recorded through written notes only. Two Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women declined to participate in the project. One woman advised she had a forthcoming parole hearing and felt that should she participate in the project; it could affect the outcome of the hearing. Written notes were also taken by the research team throughout the workshops to collect key points discussed by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and non-Indigenous women from Sisters for Change (Swain and King, 2022). At the end of each session, the written notes were discussed with the group to ensure comments were captured accurately.

2.6 Data analysis

Recorded interviews were transcribed and stored as individual Microsoft Word documents with individual participant numbers. Written notes were also transcribed into Microsoft Word documents. All interviews were coded by the first author and analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis. This inductive and descriptive approach to qualitative analysis reveals thematic patterns of meaning and allows for the consideration of the context and subjectiveness of each person’s experiences by asking the researcher to put themselves in the position of the participant and to interpret the interviews from their perspective (Terry et al., 2017). This method prioritizes the voices of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who participated in the study and acknowledges the social and cultural contexts in which they experience TBI and service-system supports (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Clarke and Braun, 2017). In the first phase of analysis, the transcripts were read and re-read by the first author to increase familiarity of the data. After the familiarization stage, the second phase involved the first author making handwritten notes on the transcripts in order to generate an initial list of ideas and early concepts. The third phase involved the production of the initial codes. These initial codes were discussed between the authors and Sister for Change, and, where agreement was reached, were then organized into groups and initial themes. Themes conceptualized as “strong” or “dense” were those expressed by numerous people independently across the data or by an individual in the workshop feedback who elicited strong agreement from others (Braun and Clarke, 2022). The next phase involved reviewing the data coded under each theme to determine if there was a formed and logical pattern. The knowledge from the data-analysis meetings was incorporated into the coding and final naming of the themes.

3 Findings

The data were organized into two themes: (1) “It’s been like a spiritual awakening for me”: A journey of understanding, insight, compassion, and healing, and, (2) “Now we are able to identify and care for these women”: Mobilizing the expertise of women in prison to empower systemic change. In the following sections, quotes from the interviews and workshop feedback are used to support the findings. To protect the identities of women, pseudonyms are used after each quote.

3.1 “It’s been like a spiritual awakening for me”: a journey of understanding, insight, compassion, and healing

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women participants reported that they had developed a new awareness of self, with this being the first time they had received in-depth education on TBI and the short-and long-term impacts of physical violence on the brain:

I think a lot of girls have been quite impressed about what they’ve been taught and what we’ve learnt. It’s given us a little bit of an insight on things too. I think just, for me, just to know that with domestic violence and being knocked around the head and all that sort of stuff, it does affect you. (Lisa, Indigenous, attended the workshop)

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who had experienced TBI self-identified with a range of commonly reported cognitive changes following this injury, including difficulty with sequencing, controlling emotions, focusing and concentrating, and retaining information. As one woman explained:

Talking about the education, everything stood out to me. Slow to react. It’s everywhere in here. Some of things they [workshop facilitators] say and how they [the women] react, I can connect with that. (Marlee, Indigenous, attended the workshop)

The workshops provided Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women with a safe space to share stories about the occurrence and impact of TBI in their own life and to make meaning of the lasting impact their injuries had on them as well as their relationships with their family and children. Discussion about the cognitive implications of TBI also had a profound impact on those women who felt they had not fulfilled their full potential in education and employment. One Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander woman described how TBI impacted day-to-day activities in the correctional center setting:

For me, you know how, the repeat, the things repeat; normally, someone with no brain injury can, so we stack trolleys for the hospital every day, so I’ve got the same trolleys, four trolleys, five trolleys every day, I pack the same trolleys every day, and I still don’t know exactly what goes on those trolleys; I’ve got to read a spreadsheet. Whereas somebody with no brain injury would know without reading that spreadsheet exactly what’s got to go on the trolleys. (Rebecca, Indigenous, attended the workshop)

Some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women recognized that the impacts of TBI could be applied to other women in their lives who had experienced violence in relationships including mothers, aunties, and friends. During the education workshop and in the days following, some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women described a deeper understanding and insight of, and empathy for, the behaviors displayed by other women in the correctional center environment that they suspected arose from a TBI. These included difficulties with reading and interpreting social cues, including understanding personal space; emotional dysregulation; organization; and taking on new information and thinking. Sarah provides the example of her observation of repetitive behaviors:

Thinking about women who ask the same questions over and over again. They ask me, “Have you seen this”? Then later they ask, “Have you seen this”? This really gets on my nerves, and I get wild. But now I’m thinking, she might have brain injury. (Sarah, Indigenous, received resource pack)

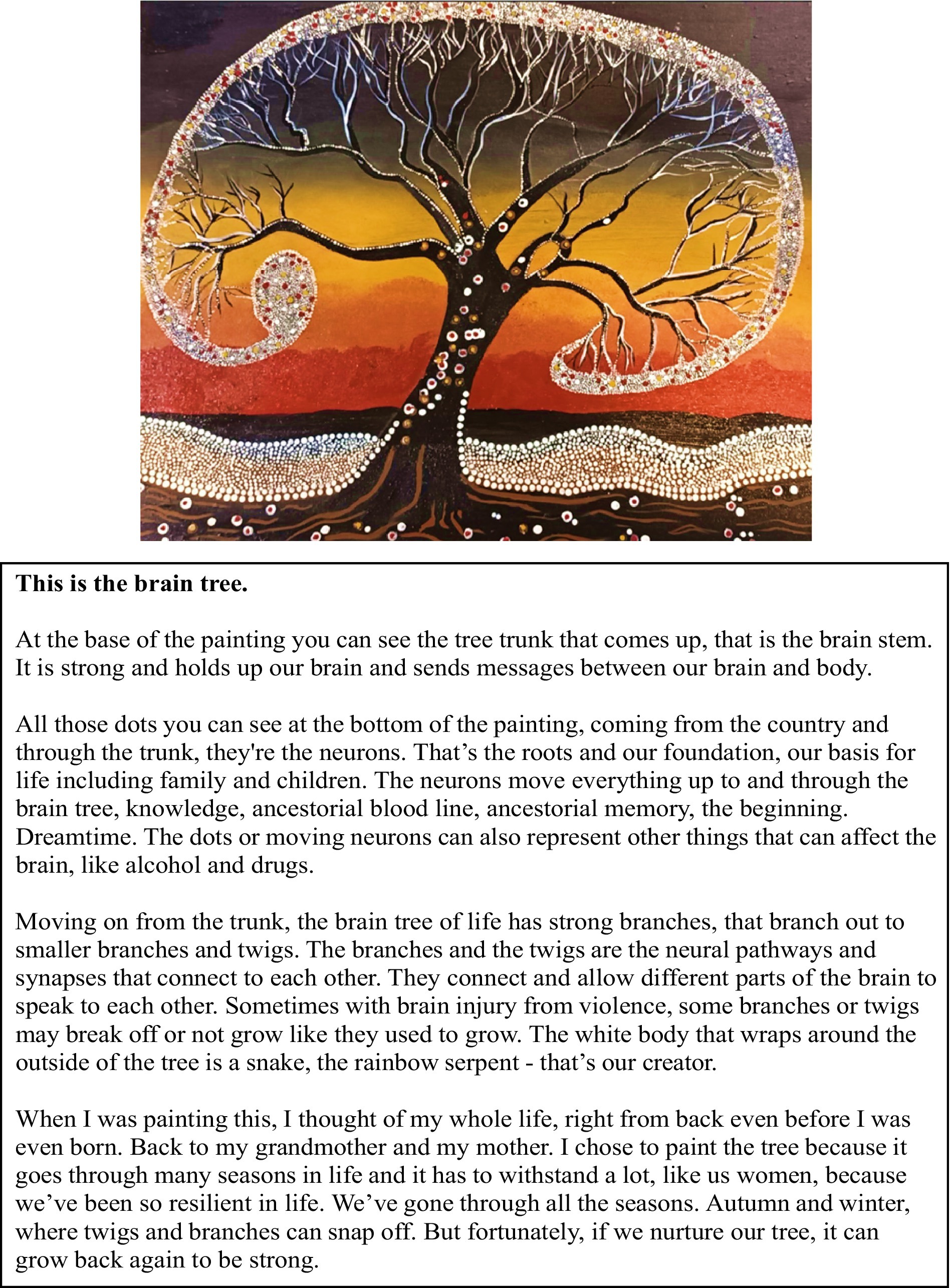

Rebecca described the workshops as being “a spiritual awakening for me.” Following the workshop, she created a piece of art, titled Brain Tree of Life (see Figure 1).

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women said that the increase in health literacy surrounding brain anatomy and its role in managing emotional regulation increased their understanding of the importance of caring and protecting the brain from harm:

I didn’t really realize how significant it [the brain] was. I didn’t realize about the brain and how important it is. (Jayne, Indigenous, attended the workshop)

Non-Indigenous women who participated in the workshops also expressed that the content of the workshops strengthened their understanding of long-lasting harms to the brain and how TBI presented in their lives or the lives of other women they knew.

Many of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who attended the education workshops reported that they had missed large proportions of their primary and secondary education. Most of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women described histories marked by loss and grief, family dysfunction, unstable living arrangements, and homelessness. All these factors compromised educational opportunities and outcomes, including school attendance. Content and discussion of various causes of ABI was critically important as this was reflective of the lives of many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who described having experienced other forms of brain injury outside of TBI. This approach enabled women with lived experience of TBI to consider how TBI interacted with other forms brain injury.

3.2 “Now we are able to identify and care for these women”: mobilizing the expertise of women in prison to empower systemic change

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women participants reported that a high proportion of women in the correctional centre had experienced multiple TBIs: “I know a lot of us here have brain injury—repetitive, short-term memory problems.” The education also generated conversations and sharing of information between women in the correctional center. They described the “curiosity” from other women at the center once there was awareness that the workshops had been delivered. As described by Lauren, other women at the correctional center were unaware of the lasting impacts of violence on the brain:

I’ve taken it back there, and with my cell mate and just a few other girls in the unit, just reading about it. A lot of girls don’t—I don’t know if they don’t know how to reach out for help or they don’t know where to go for help, but some girls were very interested in it, because a lot of them, they don’t realize they have brain injury until it’s brought to their attention. Even some girls in my [program], they say that their mind’s blank and things like that and it’s things that I’ve read, like brain injury, and a lot of girls just don’t know. It’s sad. (Lauren, Indigenous, attended the workshop)

Sisters for Change had previously been trained by government organizations on other health conditions with similar sensitivities and complexities that enabled them to be peer educators inside the correctional center. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women envisaged that the education and accrued insight into the signs of TBI and how it appears in both community and correctional center settings could be offered to all women at the correctional center: “I’m really honored to be a part of this program. I hope what I have learnt can be done in here for other women.” (Rebecca, Indigenous, attended the workshop).

Within the workshops, there was discussion about screening, assessment and diagnosis of TBI. A standardized approach to screening for TBI in correctional center settings was viewed by all women as important in raising awareness among women at the correctional center about the lasting impacts repeated TBIs have on the brain. Screening was also viewed as critical for identifying women with TBI in the correctional center setting to support them with appropriate referrals and supports in both the correctional center setting and post-discharge, including the NDIS.

In prior work with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities (McIntyre et al., 2024), the partner organization had developed the Guddi Way Screen, a culturally appropriate, non-diagnostic screening tool for TBI. Several aspects of the Guddi Way Screen were appealing to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Firstly, the screening tool was purposefully developed as a non-diagnostic tool, therefore removing the risk that the outcomes generated following completion of the tool could be used in detrimental ways against women outside of the original purpose for completing the tool. A common example discussed was TBI screening and diagnostic reports being weaponised by some Government systems, such as the child protection system. The Guddi Way Screen is administered by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and allows the opportunity to build cultural rapport and trust for the disclosure of the woman’s story and history as part of the screening process. Furthermore, another aspect of the screening tool that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women valued was the protocol for sharing of the needs assessment results. Ownership of the Guddi Way Screen results remains with women, with decisions surrounding what services have access to the results made by women themselves:

We have girls in here who have been diagnosed for their court matters. That paperwork has then been seen by child safety, used by child safety workers, for kids to be removed. It’s not right. This screening tool you’re talking about, giving us the report first and having control over who sees it. That gives me the power to say, ‘yes, you can see it or no, this is my story’. (Julie, Indigenous, attended the workshop)

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women participants suggested that Elders, rather than staff employed through the correctional system, were most appropriate to facilitate TBI screening and suggested that Elders could be trained to administer the Guddi Way Screen.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women also suggested that rehabilitation program-delivery methods should be re-envisaged due to difficulties they and other women at the correctional center have with autobiographical memory as well as retaining new information. As described by Valerie, an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander woman, who met with a Sisters for Change member on multiple occasions to discuss the TBI education pack from the workshop, TBI education provided greater awareness of why she required the support from a family member when completing a rehabilitation program at the correctional center:

I had to leave that class and come into Red Cross and sit down with my [family member] because I can’t remember a lot of things and take my stuff to work so I could present because I just couldn’t remember, but my [family member], she remembered some things, but yeah, I was just stuck with it and I had to say look, I can’t remember a lot of things from growing up, and just since being in a domestic violence relationship and just trauma from growing up and stuff, I couldn’t remember anything, and I just had to, my sister had to help me do it, and I said that to them [program facilitators]. (Valerie, Indigenous, received resource pack)

In the workshops and interviews, women recommended educational resources and training on symptoms of TBI and how these present in the correctional center setting should also be delivered to staff working in the correctional centres and community corrections:

We could put together information packs for women which could help when people are getting out of the prison—they can give these packs to their parole officer. (Natalie, non-Indigenous, attended the workshop)

Training for officers, program staff, and support workers needed. (Josie, Indigenous, attended the workshop)

All the caseworkers at probation and parole need to do this [training]. (Chelsea, non-Indigenous, attended the workshop)

Both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and non-Indigenous women who attended the workshops reported that it was also broadly critical for there to be support services who understanding TBI for women to connect with before and after release to support them to maintain reporting and other requirements of their parole conditions.

Inclusion of TBI in offender management policies was perceived as having the ability to change how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women being penalized for failure to attend appointments with community corrections or to fulfill all their probation and parole conditions:

We need to connect with outside services who can help because it’s hard to link women up with services once they’re out. It should be happening in here. That’s why there are women coming back within six weeks. (Diane, Indigenous, attended the workshop)

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and non-Indigenous women also recommended that the education and screening protocols should also be extended to male correctional centers for men experiencing imprisonment to access.

4 Discussion

TBI has been experienced by the majority of people in contact with the criminal justice system (McGinley and McMillan, 2019). With research suggesting women experience TBI and its impacts in ways that reflect gendered differences in the patterns and frequency of violence, this study provides a unique insight into the views of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women about how correctional setting environments and policies can be more TBI-informed and responsive for women experiencing imprisonment. The content of the TBI education program reflected the lived realities of many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who have experienced gendered-based violence from men including repeated TBI and non-fatal strangulation, as well as long-term alcohol and drug use (Sullivan et al., 2019; Wilson et al., 2017). Similar to studies in other settings, TBI education plays a critical role for people living with this injury to make informed decisions about self-management of TBI symptoms (Glorney et al., 2018; Hart et al., 2018). Due to the gaps in education and information in the emergency department, TBI workshops were the first time Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in this study received in-depth information on brain anatomy, functioning, TBI symptoms, and strategies to manage symptoms. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women may often be diverted from the critical points of access to this knowledge—such as healthcare or hospital access for medical assessment and treatment—due to risks of further violence, deep fears about being referred to child-protection systems for reporting injuries from family violence and managing poverty and homelessness (Fitts et al., 2023c). When Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women do attend emergency departments, the fast pace and noise of the environment can affect their capacity to understand and retain information shared by health professionals (Fitts et al., 2024; Wills and Fitts, 2024). Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who experience imprisonment have childhood experiences of moving homes frequently and foster care, resulting in inconsistent access to education in school, which leaves a lasting impression on learning and health literacy (Bevis et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2017).

The positive impacts of the workshops have not been limited to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. While Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women were the focus of the larger research project, the TBI education was also beneficial for non-Indigenous women who also disclosed their personal lived experiences of violence-related TBI or had family members or friends who had experienced the injury. This suggests targeted approaches can have universal benefits that generate a ripple effect within the correctional center environment for all women.

4.1 Implications for policy and practice and future directions

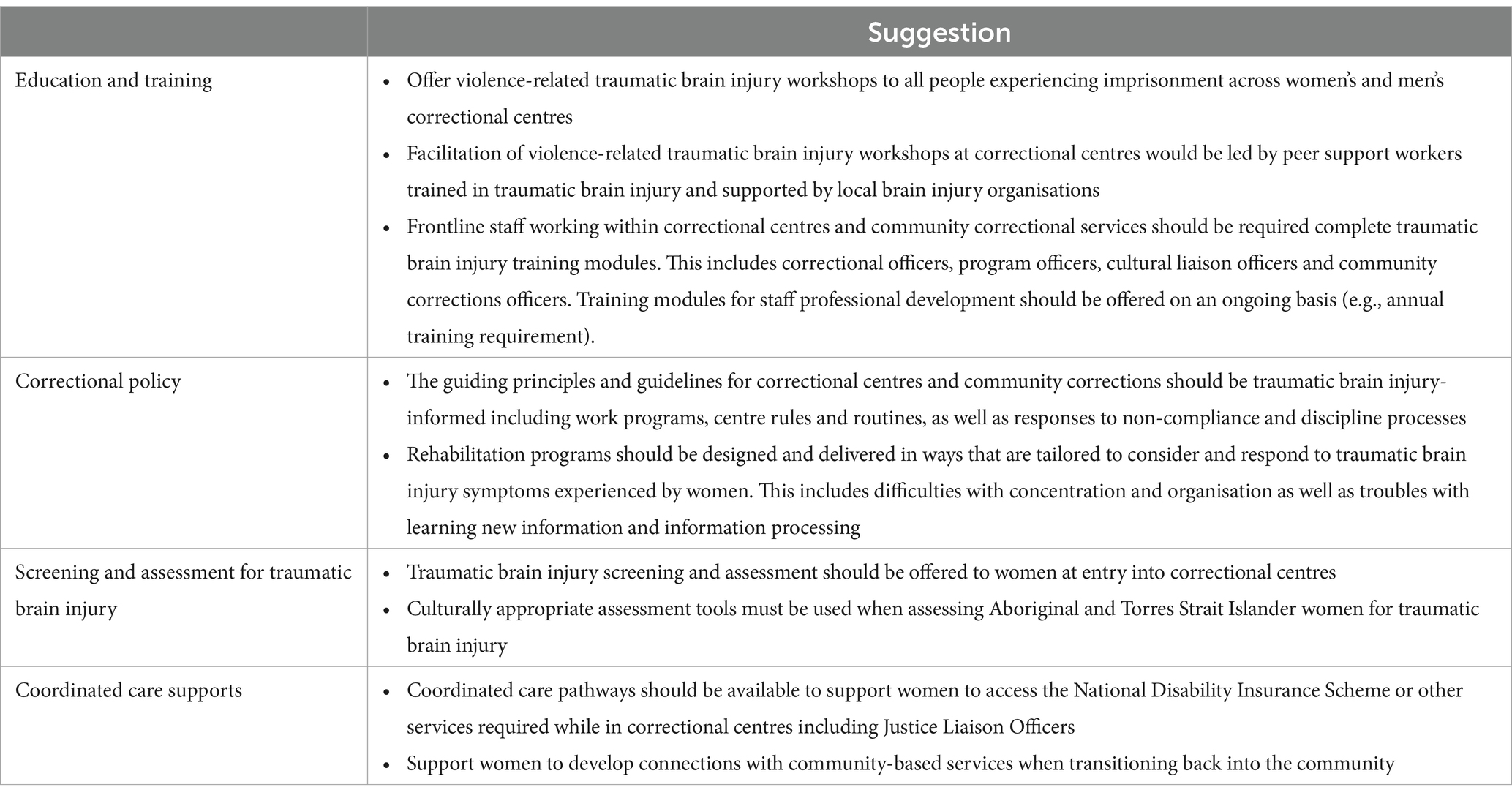

The study generated a range of measures that would embed TBI into the correctional setting in practical ways (see Table 1). As recommended by women in this study and elsewhere (O’Brien, 2022), a standardized process to pre-screen women for TBI upon entry into correctional centers would identify Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who require TBI assessment and related supports (Minnesota Department of Human Services, 2015). Screening for TBI in correctional centers could also generate evidence that can help inform investment in programs and services for TBI in correctional centers (Chan et al., 2023). TBI screening and assessment protocols developed must reflect the elements valued by women in this study including women holding ownership over assessment outcomes and who has access to this information. It is critically important TBI assessment outcomes are not weaponized against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers and do not impact the chances women have for reunification with their children (Boyle et al., 2022). Rather, information obtained from cognitive assessments must be used as a way of informing structure and other strategies to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women to have active relationships with the children.

Table 1. Strategy suggestions to include traumatic brain injury within correctional policy and practice.

As the experience of TBI is common among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and men experiencing imprisonment (Lakhani et al., 2017), expansion of TBI education to all people experiencing imprisonment and the frontline correctional workforce was considered to be a practical measure that would lead to deeper understanding of how TBI symptoms present in the correctional setting. TBI education that can effectively build knowledge, and capacity to identify the signs and symptoms as well as respond in appropriate ways could lead to reduced negative interactions between correctional officers and women with TBI experiencing imprisonment and decreased use of consequences for what are effectively behaviors from TBI (Chan et al., 2023). For example, correctional officer case notes and reports are used to inform decisions around a woman’s eligibility for parole, changes to security clearance, programs or incentive schemes. Therefore, a series of correctional officer case notes that describe argumentative and problematic behaviors as well as failure to follow instructions can have serious consequences for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women with TBI from violence.

Efforts to build TBI support within correctional center was also identified including through training women to be peer mentors to disseminate TBI information to other women. Sisters for Change members who participated in the TBI education sessions are now the knowledge holders of how behaviors and symptoms of TBI may manifest within the correctional center environment. As knowledge holders the women have the leadership capacity to work alongside the correctional staff to modify and/or adjust rehabilitation programs and work situations to take into account individual responses to the impacts of TBI. Integration of TBI into both program delivery approaches and assessments with TBI is critically important as common long-lasting changes in comprehension, reason, judgment, learning or memory can negatively impact successful completion of programs. Justice liaison officers in Australian correctional centers also have a critically important role to play. While there have been mixed views on their effectiveness (Disability Royal Commission, 2021; Yates et al., 2022), justice liaison officers could also assist Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women living with TBI coordinate access to the NDIS or other services.

4.2 Future directions and research

Since the completion of the project, Sisters for Change continue to circulate TBI information in the correctional center including providing information and educational resources to women entering the correctional center and requests from women at the correctional center continue to be received to complete the TBI screening tool (McIntyre et al., 2024). These lasting impacts of the workshops and project reflect a genuine partnership, where women felt they were opting into a process that was safe and beneficial for them and their long-term recovery. Moving forward, additional research to understand the longer-term impacts of TBI education for women whose voices are represented within this paper as well as for the frontline correctional workforce could provide further insight into how education can change the culture of the correctional setting. We encourage research that can help to dismantle settler colonial, oppressive systems, re-center the voices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elders and women and provide evidence to inform policy direction and practices that can effectively reduce the contact Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women with violence-related TBI have with the criminal justice system.

4.3 Limitations

There are several limitations that must be acknowledged when considering the findings of this study. First, not all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women with lived experience of TBI from family violence participated in the workshops. While this study has identified the initial benefits of TBI education for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, further co-designed research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women is needed to develop appropriate pathways of sharing TBI education in the correctional center setting. Second, the study included one single correctional center. Third, the project lead who completed all interviews with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women is a white settler, and this may have affected what information and the depth of information shared in interviews by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women.

5 Conclusion

Against the backdrop of a rapidly rising women’s correctional center population, there is a high number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in correctional centers who have experienced TBI from violence in Australia. This study has identified that TBI education and training are critical aspects of ensuring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women can develop a deeper understanding of the impact of the injury on themselves and build their capability to implement strategies to manage both short-and long-term symptoms. Providing education around TBI to both women and frontline correctional staff has the potential to lead to policies that provide safer responses for both women and frontline correctional staff. Adapting a whole of correctional system approach to TBI screening, referrals, and supports is essential to ensure adequate responses to the needs of women with TBI. Collaborative efforts to build TBI awareness in correctional centers can have a positive impact on both the health and wellbeing of women and the correctional-center environment.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are not publicly available due to identifying information that could compromise research participant privacy and/or consent. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to bWljaGVsbGUuZml0dHNAbWVuemllcy5lZHUuYXU=.

Ethics statement

This study involving humans was approved by the Townsville Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/QTHS/88044). The study was also approved by the Queensland Corrective Services Research and Evaluation committee. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MF: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. JC: Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. RM: Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. AD: Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Australian Research Council via a Discovery Early Career Research Award for M. Fitts (#210100639). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Australian Research Council.

Acknowledgments

The authors of the paper recognize Sisters for Change members as co-authors of this paper. Sisters for Change participated in the interpretation of data, were involved in drafting and revising the manuscript and provided approval for publication of the content and agreed to be accountable as a co-author of the manuscript. Due to the conflicting confidentiality conditions of Queensland Corrective Services and the journal’s authorship guidelines, they were not able to be formally listed as a co-author. Thank you to all the women who participated for being generous with their time and information shared for this project. We are grateful for the ongoing support we have received from Sisters for Change. We thank Karen Soldatic and Yasmin Johnson (Western Sydney University) and Shehana Friday (Synapse Australia) for their involvement in the education and co-facilitation of interviews as well as research support. Thank you to Queensland Corrective Services staff and management for their support of the research project. The views reflected in this article are those of the authors only and do not reflect the funder, the Australian Research Council, nor the views or policies of Queensland Corrective Services.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Atkinson, J. (2002). Trauma trails, recreating song lines: The transgenerational effects of trauma in indigenous Australia. North Melbourne, Victoria: Spinifex Press.

Australian Government. (2020). Closing the gap targets and outcomes. Available at: https://www.closingthegap.gov.au/national-agreement/targets.

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. (2020). AIATSIS code of ethics for aboriginal and Torres Strait islander research. Available at: https://aiatsis.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-10/aiatsis-code-ethics.pdf.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2019). The health of Australia’s prisoners. Available at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/prisoners/health-australiaprisoners-2018/contents/table-of-contents.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2020). The health and welfare of women in Australia’s prisons. Available at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/32d3a8dceb84-4a3b-90dc-79a1aba0efc6/aihw-phe-281.pdf.aspx?inline=true.

Australian Law Reform Commission. (2017). Pathways to justice—Inquiry into the incarceration rate of aboriginal and Torres Strait islander peoples (final report no 133). Available at: https://www.alrc.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/final_report_133_amended1.pdf.

Bagnall, A.-M., South, J., Hulme, C., Woodall, J., Vinall-Collier, K., Raine, G., et al. (2015). A systematic review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of peer education and peer support in prisons. BMC Public Health 15:Article 290. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1584-x

Baldry, E., and Cunneen, C. (2014). Imprisoned indigenous women and the shadow of colonial patriarchy. Aust. N. Z. J. Criminol. 47, 276–298. doi: 10.1177/000486581350335

Baldry, E., McCausland, R., Dowse, L., and McEntyre, E. (2015). A predictable and preventable path: Aboriginal people with mental and cognitive disabilities in the criminal justice system. Available at: https://www.mhdcd.unsw.edu.au/.

Bevis, M., Atkinson, J., McCarthy, L., and Sweet, M. (2020). Kungas’ trauma experiences and effects on behaviour in Central Australia (Research report, 03/2020). Sydney: ANROWS.

Bohanna, I., Fitts, M., Bird, K., Fleming, J., Gilroy, J., Clough, A., et al. (2019). The potential of a narrative and creative arts approach to enhance transition outcomes for indigenous Australians following traumatic brain injury. Brain Impairment 20, 160–170. doi: 10.1017/BrImp.2019.25

Boxall, H., Dowling, C., and Morgan, A. (2020). Female perpetrated domestic violence: prevalence of self-defensive and retaliatory violence. Trends Issues Crime Crim. Justice 584, 1–17. doi: 10.52922/ti04176

Boyle, Q., Illes, J., Simonetto, D., and van Donkelaar, P. (2022). Ethicolegal considerations of screening for brain injury in women who have experienced intimate partner violence. J. Law Biosci. 9:l1-lsac023. doi: 10.1093/jlb/lsac023

Brain Injury Australia. The prevalence of acquired head injury among victims and perpetrators of family violence. (2018). Available at: https://www.braininjuryaustralia.org.au/wp-content/uploads/BRAININJURYAUSTRALIAfamilyviolencebraininjuryFINAL.pdf.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2022). Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qual. Psychol. 9, 3–26. doi: 10.1037/qup0000196

Busija, L., Cinelli, R., Toombs, M. R., Easton, C., Hampton, R., Holdsworth, K., et al. (2020). The role of elders in the wellbeing of a contemporary Australian aboriginal and Torres Strait islander community. The Gerontologist 60, 513–524. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny140

Chan, V., Estrella, M. J., Syed, S., Lopez, A., Shah, R., Colclough, Z., et al. (2023). Rehabilitation among individuals with traumatic brain injury who intersect with the criminal justice system: a scoping review. Front. Neurol. 13:1052294. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.1052294

Clarke, V., and Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 12, 297–298. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613

Costello, K., and Greenwald, B. D. (2022). Update on domestic violence and traumatic brain injury: a narrative review. Brain Sci. 12:122. doi: 10.3390/brainsci12010122

Creswell, J. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Disability Royal Commission. (2021). Transcript of proceedings. Available at: https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/system/files/2021-08/Transcript%20Day%202%20-%20Public%20hearing%2015%2C%20Brisbane_0.pdf.

Fitts, M., Cullen, J., and Barney, J. (2023a). Barriers preventing indigenous women with violence-related head injuries from accessing services in Australia. Aust. Soc. Work. 76, 406–419. doi: 10.1080/0312407X.2023.2210115

Fitts, M. S., Cullen, J., Kingston, G., Johnson, Y., Wills, E., and Soldatic, K. (2023b). Understanding the lives of Australian indigenous women with acquired head injury through family violence: a qualitative study protocol. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20:1607. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20021607

Fitts, M. S., Cullen, J., Kingston, G., Johnson, Y., Wills, E., and Soldatic, K. (2023c). Using research feedback loops to implement a disability case study with indigenous communities and service providers in regional and remote Australia. Health Sociol. Rev. 32, 94–109. doi: 10.1080/14461242.2023.2173018

Fitts, M. S., Cullen, J., Kingston, G., Wills, E., and Soldatic, K. (2022). “I don’t think it’s on anyone’s radar”: the workforce and system barriers to healthcare for indigenous women following a traumatic brain injury acquired through violence in remote Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:14744. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192214744

Fitts, M. S., Johnson, Y., and Soldatic, K. (2024). The emergency department response to indigenous women experiencing traumatic brain injury from family violence: insights from interviews with hospital staff in regional Australia. J. Fam. Violence. doi: 10.1007/s10896-023-00678-5

Glorney, E., Jablonska, A., Wright, S., Meek, R., Hardwick, N., and Williams, W. H. (2018). Brain injury Linkworker service evaluation study: technical report. University of London. Available at: https://pure.royalholloway.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/33210988/Brain_Injury_Linkworker_Service_Evaluation_Study_Technical_Report.pdf.

Haag, H. L., Sokoloff, S., MacGregor, N., Broekstra, S., Cullen, N., and Colantonio, A. (2019). Battered and brain injured: assessing knowledge of traumatic brain injury among intimate partner violence service providers. J. Women's Health 28, 990–996. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7299

Hart, T., Driver, S., Sander, A., Pappadis, M., Dams-O’Connor, K., Bocage, C., et al. (2018). Traumatic brain injury education for adult patients and families: a scoping review. Brain Inj. 32, 1295–1306. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2018.1493226

Jamieson, L. M., Harrison, J. E., and Berry, J. G. (2008). Hospitalisation for head injury due to assault among indigenous and non-indigenous Australians, July 1999 – June 2005. Med. J. Aust. 188, 576–579. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01793.x

Kennedy, M., Maddox, R., Booth, K., Maidment, S., Chamberlain, C., and Bessarab, D. (2022). Decolonising qualitative research with respectful, reciprocal, and responsible research practice: A narrative review of the application of yarning method in qualitative Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research. Int. J. Equity Health. 21, 1–134. doi: 10.1186/s12939-022-01738-w

Kilroy, D., Lean, T., and Davis, A. Y. (2023). “Abolition as a decolonial project” in The Routledge international handbook on decolonizing justice, vol. 1. 1st ed (New York: Routledge), 227–234.

Lakhani, A., Townsend, C., and Bishara, J. (2017). Traumatic brain injury amongst indigenous people: a systematic review. Brain Inj. 31, 1718–1730. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2017.1374468

Langlois, J. A., Rutland-Brown, W., and Wald, M. M. (2006). The epidemiology and impact of traumatic brain injury: a brief overview. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 21, 375–378. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200609000-00001

McGinley, A., and McMillan, T. (2019). The prevalence, characteristics, and impact of head injury in female prisoners: a systematic PRISMA review. Brain Inj. 33, 1581–1591. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2019.1658223

McIntyre, M., Cullen, J., Turner, C., Bohanna, I., and Rixon, K. The development of a cognitive screening protocol for aboriginal and/or Torres Strait islander peoples: the Guddi way screen. Brain Inj. 25:IB23058. doi: 10.1071/IB23058

McKenzie, G., and Wright, K. A. (2023). The effects of peer inclusion in the design and implementation of university prison programming: a participatory action research, randomized vignette study. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 47, 30–36. doi: 10.1037/prj0000555

Menon, D. K., Schwab, K., Wright, D. W., and Maas, A. I. (2010). Position statement: definition of traumatic brain injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 91, 1637–1640. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.05.017

Minnesota Department of Human Services. (2015). TBI in Minnesota correctional facilities: Systems change for successful return to community. Available at: https://mn.gov/doc/assets/TBI_White_Paper_MN_DOC-DHS_tcm1089-272843.pdf.

Nancarrow, H. (2019). Unintended consequences of domestic violence law: Gendered aspirations and racialised realities. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

O’Brien, M. T. (2022). Brain injury and prison: over-representation, prevention and reform. Aust. J. Hum. Rights 28, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/1323238X.2022.2093462

Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications Ltd.

Pointer, S., Harrison, J., and Avefua, S. (2019). Hospitalised injury among aboriginal and Torres Strait islander people 2011–12 to 2015–16. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Available at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/injury/hospitalised-injury-among-aboriginal-and-torres-st/contents/table-of-contents.

Queensland Government. (2023). Stripped of our dignity. Available at: https://www.qhrc.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/45187/QHRC_StrippedOfOurDignity_FullReport.pdf.

Ramos, S. D. S., Oddy, M., Liddement, J., and Fortescue, D. (2018). Brain injury and offending: the development and field testing of a Linkworker intervention. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 62, 1854–1868. doi: 10.1177/0306624X17708351

Sullivan, E. A., Kendall, S., Chang, S., Baldry, E., Zeki, R., Gilles, M., et al. (2019). Aboriginal mothers in prison in Australia: a study of social, emotional and physical wellbeing. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 43, 241–247. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12892

Swain, J., and King, B. (2022). Using informal conversations in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods 21:160940692210850. doi: 10.1177/16094069221085056

Terry, G., Hayfield, N., Clarke, V., and Braun, V. (2017). “Thematic analysis” in The Sage handbook of qualitative research in psychology. eds. C. Willig and W. S. Rogers (United Kingdom: SAGE Publications Ltd.), 17–37.

Wills, E., and Fitts, M. (2024). Listening to the voices of aboriginal and Torres Strait islander women in regional and remote Australia about traumatic brain injury from family violence: a qualitative study. Health Expect. 27:e14125. doi: 10.1111/hex.14125

Wilson, M., Jones, J., Butler, T., Simpson, P., Gilles, M., Baldry, E., et al. (2017). Violence in the lives of incarcerated aboriginal mothers in Western Australia. SAGE Open 7:215824401668681. doi: 10.1177/2158244016686814

Keywords: education, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, women, traumatic brain injury, violence, peer mentors

Citation: Fitts MS, Cullen J, Montgomery R and Duffy AG (2024) “It’s been like a spiritual awakening for me”: the impacts of traumatic brain injury education with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in the Australian correctional system. Front. Educ. 9:1406413. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1406413

Edited by:

Monique R. Pappadis, University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, United StatesReviewed by:

Angela Ciccia, Case Western Reserve University, United StatesHope Kent, University of Exeter, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2024 Fitts, Cullen, Montgomery and Duffy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Michelle S. Fitts, bWljaGVsbGUuZml0dHNAbWVuemllcy5lZHUuYXU=

Michelle S. Fitts

Michelle S. Fitts Jennifer Cullen5,6,7

Jennifer Cullen5,6,7