- Faculty of Education and Society, Department of Culture, Language and Media, Malmö University, Malmö, Sweden

Introduction: The importance of supervisory interaction facilitated by dialogic feedback is known to create a shared understanding between supervisors and students. However, previous studies of supervisory interaction mainly focus on exploring feedback provision as an input for specific improvement rather than as a process of interaction regardless of its discursivity. Informed by learning community theory, this study explores how thesis supervision in English as an Additional Language contexts is negotiated to identify the supervisory interaction patterns and strategies.

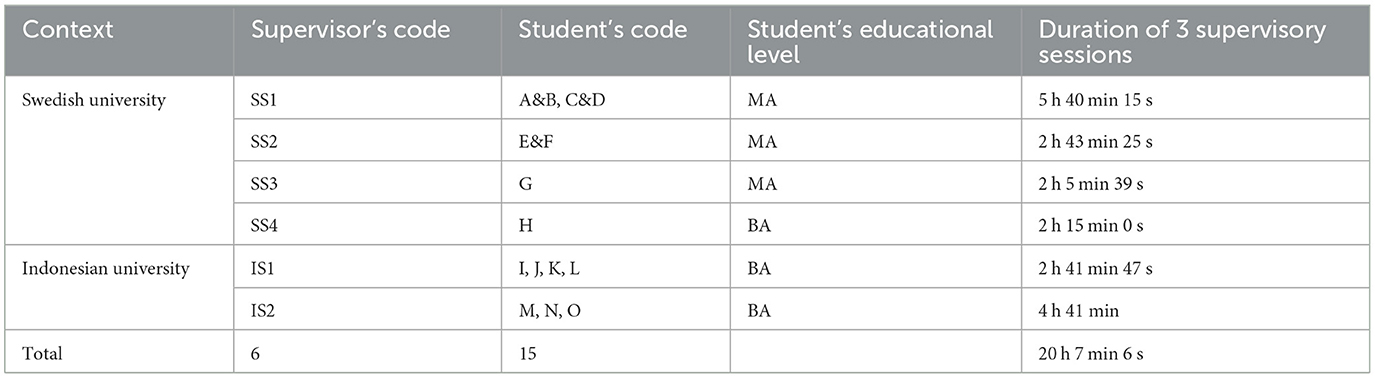

Method: This study applied a qualitative case study by involving six supervisory dyads (six supervisors and 15 students) in English- medium study programs. Thematic analysis was used to analyze 18 video-recorded supervision sessions from the beginning, the middle, and the end of the supervision process.

Findings and discussion: The findings illuminate the negotiated interaction patterns and strategies in supervisory meetings that can be organized into three themes: (1) managing correction, (2) managing scaffolding, and (3) managing students' emotional expressions. The supervisory interaction patterns tend to take the form of a common institutional talk due to the students' desire for confirmation and suggestions. Prompting strategies through exploratory questions can scaffold students' development of argumentative skills although students' deviant responses frequently lead to supervisors' further explanation. The theoretical analysis underscores that learning community theory emphasizes the development of student's academic literacy and argumentative proficiency through dialogic inquiry. Yet, effective engagement in such inquiry necessitates prerequisite academic literacy and rhetorical competencies.

Conclusion: This study highlights the need for developing student's academic literacy, research literacy, and communication skills to achieve an effective inquiry dialogue in thesis supervision.

1 Introduction

Supervision that involves social interaction and collaborative sense-making encourages positive supervisory relationships and promotes students' learning. Carrington (2004) points out that supervision as a reciprocal learning process that involves a shared understanding between both students and supervisors can reduce tension, encourage risk-taking, create openness and flexibility, and promote new ideas. Furthermore, supervision with open communication, particularly regarding the supervisor's intentions and expectations, is known to foster reciprocal trust between supervisor and student (Zhao and Mills, 2019). Trust in supervisory interactions can develop students' autonomy and decision-making (Seppälä et al., 2011) and promote their active learning participation (Schmutz et al., 2021). In contrast, the lack of supervisory interaction contributes to students' failure and is viewed as a negative experience, with less satisfaction, inadequate help, less trust, and less willingness to share sensitive information (Sköld et al., 2018). Hence, the deliberate craftsmanship of negotiation is required to achieve shared understanding in supervisory practices. Feedback is frequently used to clarify that which is unclear, negotiate meaning, and activate students' cognitive processes (see, e.g. Zhu and Carless, 2018). Ribeiro and Jiang (2020) also explain that negotiated interaction through feedback provision can develop students' linguistic and communicative skills by prompting them to ask for clarification, confirm and check comprehension, elaborate ideas, and take note of language correction. In other words, feedback (as a form of provided information) and interaction (the dynamic exchange of information) in supervision mutually shapes the achievement of collaborative sense-making between students and supervisors.

The role of feedback as an effective clarifying device in a negotiated interaction is highlighted by several studies. Through experimental research, dialogic feedback has been considered to play an important role in creating negotiated interaction. It nurtures student–supervisor relationships, enhances the learning process (Crimmins et al., 2016), and improves students' writing skills (Walton, 2020). In addition, it promotes learning performance, engages the student (Giamos et al., 2023), and develops disciplinary knowledge (Turner, 2023). However, its important role in creating negotiated interaction, research investigating how feedback is negotiated within the interactional process between students and supervisors is limited. Most research examines feedback as input for a specific effect rather than a process (Ajjawi and Boud, 2017). As Ajjawi and Boud (2017, p. 261) suggest, “analyzing feedback in situ […] may hold potential for educators to analyze their own feedback practices and educational design, including, for example, sequencing of assignments, design of interactive cover pages or prompts from teaching interventions” to stimulate students to engage in dialogue, seek feedback, and reflect on their work. Therefore, exploring how feedback provision in thesis supervisory meetings are negotiated to create shared understanding is important.

My proposition for feedback aligns with Gravett's (2022) idea that feedback cannot be seen as an isolated element but rather as a situated interaction, given that feedback interaction and student engagement are influenced by social relations, as well as materials, space, and the involved actors (students and supervisors). This article focuses on exploring negotiated interaction through feedback provision in English as an Additional Language (EAL) thesis supervision. Thesis supervision is considered a suitable context to explore how feedback interaction is negotiated moment by moment because it involves iterative feedback provision and discussion between students and supervisors which according to Murray (2011), acts not only as guidance but also as corrections to improve students' writing within a set time frame.

Within the EAL context, academic texts are intended for all readers who use and understand English regardless of their first languages and geographical positions. Therefore, exploring the negotiated interaction in EAL thesis supervision to support the academic writing process is important. As Toth and Gil-Berrio (2022) explain, the clarity of what is said, why it is said, and how it is interpreted determines the construction of meaning among students and supervisors. For this study, Indonesia and Sweden were chosen because English is an Additional Language in both contexts. The study explores the negotiated interaction in ongoing EAL thesis supervision sessions. It aims to identify the strategies and patterns of negotiated interaction between students and supervisors. The following research questions guided the study:

1. How are supervisory interactions between students and supervisors negotiated in Swedish and Indonesian thesis supervision?

2. Which strategies do supervisors and students use to communicate their arguments during supervision?

1.1 Conceptualizing negotiated interaction in thesis supervision

In this study, the concept of negotiated interaction is inspired by Tecedor (2023) and is used to explain that, in supervisory sessions, interaction is negotiated between two speakers (i.e., a student and supervisor) to establish and maintain reciprocal understanding. The negotiated interaction is a dialogue involving feedback in the form of negotiation of meaning (NoM) to attain mutual understanding or negotiation of form (NoF) to solve linguistic problems.

An interaction is negotiated when it has a pattern which, according to Varonis and Gass (1985), comprises four elements: (1) a trigger that prompts a communication breakdown, (2) an indicator of the interlocutor's misunderstanding, lack of understanding, or no understanding, also called “deviant” or “unacceptable” utterances, (3) a response to bridge any communication gaps, and (4) a reaction to the response that solves and resumes the temporarily interrupted discourse or communication breakdown. The communication breakdown trigger can be, for example, a draft that requires feedback, concepts or terminology that need clarification or correction, sentence or paragraph level errors, or anything else that requires revision. This trigger leads to Varonis and Gass's (1985) second, third, and fourth elements, as listed above.

In Kirschner et al.'s (2008) view, NoM between students and supervisors is a socially shaped interaction to achieve “common ground” and “knowledge construction” through the clarification of personal understanding, the confirmation of alignment with interlocutors' intention, feedback provision, and a re-verification process (p. 407). Here, the NoM occurs individually (inter-dialogue between students or supervisors themselves) and collectively (intra-dialogue among students or between students and supervisors). This study aligns with Batstone's (2016) ideas that explicit guidance on how, when, and why to use the NoF, also known as “corrective feedback,” is required to facilitate students' understanding because sustained awareness of form can become overwhelming or even personally offensive (Batstone, 2016, p. 506). In contrast, the current study departs from Batstone's (2016) ideas, where NoF is considered “reactive, incidental, brief, elicited by prompts for learners to self-correct, and didactic (involving correction of linguistic errors that do not lead to comprehension difficulties)” (p. 507). In thesis supervision, both NoM and NoF can be systematically processed within the conversation. The feedback (either corrective, epistemic, suggestive, or complementary) is usually given before the supervisory meetings. In this study, the supervisors sent written or highlighted feedback to the students and asked them to reflect on it before attending the sessions.

Supervisors and students both face challenges when exchanging ideas and creating negotiated, reciprocal interaction. According to Yerushalmi (2014), the interaction in a supervisory setting involves a dynamic shift between unformulated and intuitive knowledge (gained from the turn-taking in the dialogue) and formulated and conceptualized knowledge (gained from theoretical understanding). In the supervisory meetings, students may focus on what they should do and how things should or could be done, leading to supervisors' directive suggestions and more scaffolding, which Zackariasson (2020) has also observed1. However, the negotiation does not necessarily deal with solely intuitive or formulated knowledge but rather occurs to clarify the contradiction between intuitive and formulated knowledge. Hence, the negotiated interaction in thesis supervision involves a balance between safe spaces and certain challenges to exchange ideas and take risks. It needs open dialogue, shared values, mutual respect, attentive listening, and agreed-upon ground rules to develop students' growth and risk-taking along with collective decision-making to deal with disagreement (Macpherson, 2021).

2 Theoretical framework

The central role of negotiated interaction in thesis supervision is underpinned by the dialogic teaching concept of learning community (Reznitskaya and Gregory, 2013), which focuses on “how students develop their epistemological understanding, argument skills, and disciplinary knowledge through engaging in a dialogic interaction with others” (p. 115). Based on this concept, learning occurs through a gradual and reciprocal internalization process. As students develop new abilities, they foster their argumentation skills, influence how the discussion proceeds, and introduce new prompts into the classroom discussion. In this case, the learning process and control over classroom discourse occur collaboratively between students and supervisors. According to Reznitskaya and Gregory (2013), “As class participants collectively formulate, defend, and scrutinize each other's viewpoints, they begin to appropriate general intellectual dispositions and specific linguistic skills of reasoned argumentation, which they can use whenever they need to resolve complex issues” (p. 118). Based on this concept, the interaction between students and supervisors exemplifies the collaborative engagement in inquiry dialogue that leads to thinking and supports rationality2.

Within a learning community framework, successful interaction between students and supervisor cultivates transferable knowledge and argumentation skills achieved through an inquiry dialogue approach which benefits both individual learners and the group. The essence of inquiry dialogue involves a collaborative approach to communication through collective inquiry. The inquiry dialogue outcomes expect four competences from students: (1) argumentative competence, (2) knowledge of logical structures (the principles and patterns of reasoning that govern the construction and evaluation of arguments), (3) knowledge of standard evidence (i.e., what types of evidence are appropriate and persuasive in supporting or refuting an argument), and (4) useful devices in argumentation (i.e., language structures or inquiry moves to advance understanding or add persuasive force to an argument). By engaging in a collaborative inquiry, students should obtain “more complex, nuanced, and personally meaningful disciplinary knowledge.” Reznitskaya and Gregory (2013) explain that “as members of a classroom community become more advanced in their intellectual capacities, they contribute new thought and language practices to group discussions, thus stimulating new rounds of development” (p. 121). In the present study, the concept of learning community is used to determine how the negotiated interaction through feedback provision facilitates reciprocal meaning-making between supervisors and students. This concept is useful for exploring how the EAL student–supervisor interaction helps students control the conversation, develop their argumentative competence, raise awareness of their disciplinary knowledge, and use language devices for their argumentation.

3 Research design

As a part of a larger project that used a multi-case study design (Yin, 2018), the present research focused on exploring how supervisory interaction is negotiated in the ongoing supervision sessions without generalizing. It expands on previous research on Swedish and Indonesian thesis supervisory relationships and roles (Nangimah and Walldén, 2023a), supervisors' feedback priorities, and students' reactions to feedback (Nangimah and Walldén, 2023b). Unlike previous research based on interview results, the present research involves qualitative data from videos recorded in two different cases: a supervisory dyad in Sweden and in Indonesia. A multi-case study design was used to explore the details of supervisory cases in Swedish and Indonesian universities (without any intervention) to understand negotiated supervisory interaction in its real-world context.

3.1 Data collection and materials

The data collection began in Spring 2021 by following students' thesis development that lasted one or two semesters3. Due to time and access constraints during the COVID-19 pandemic, convenience sampling (Robinson, 2014) was applied, and no face-to-face meetings or on-site observation were conducted. The criteria for participant selection were supervisor-student dyads where students wrote theses in English, supervisors had a minimum of 2 years supervisory experience, and students conducted individual empirical research for the first time. The author initially sent research invitations to research managers at six universities. After gaining research approval letters from three Indonesian universities (not needed from Swedish university), invitations were extended to supervisors, and then it was presented to both students and supervisors. A total of 12 supervisory dyads from four universities participated in the bigger project, including five from a Swedish university, five from two Indonesian private universities, and two from an Indonesian public university. The recruited participants in this study were supervisory dyads in two English-medium study programs: English for Teacher Education (for Indonesian BA levels and Swedish MA levels) and English Studies (for Swedish BA level)4. The supervisors in this article had varied supervisory experience range between 3 to 22 years. I requested supervisors to record and submit their supervision sessions, encompassing their entirety from the beginning to the end of supervision process. Participants failing to comply with this requirement (six supervisory dyads) were excluded from this article. Hence, this article focused on six supervisory dyads: four from the Swedish university and two from the Indonesian private universities. Data for this study consisted of 18 video-recorded supervision sessions from six supervisory dyads (six supervisors and 15 students). The videos covered three supervisory meetings (the beginning, the middle, and the end of the supervision process) from each supervisory dyad. Each supervisory session lasted around 40–130 min, resulting in a total of 20 h 7 min 6 s (see Table 1).

Ethical guidelines (ALLEA - All European Academies, 2017), General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) requirements (Regulation, 2016/679), and guidelines for good research practice (Swedish Research Council, 2017) have been followed in all stages of the data collection and data handling. Accordingly, all participants gave their informed consent (both spoken and written) to participate in this study, and the material has been anonymized. The four Swedish supervisors were coded as SS1–SS4, and the two Indonesian supervisors were coded as IS1 and IS2. In addition, the Swedish students were coded as Students A–H, while the Indonesian students were anonymized as Students I–O.

The supervision sessions were held in a group meeting in the Indonesian context (one supervisor with three or four students) and in one-on-one supervision sessions in the Swedish context. Six Swedish students (A–F) wrote their theses in pairs, while other students, including the Indonesian students, worked individually. Before the sessions, the students sent their drafts to the supervisors, and the supervisors returned them with either written or highlighted feedback. Several student projects were discussed during group supervisions in the Indonesian context. Each student took turns presenting their progress followed by a question-and-answer session between the supervisors and the student presenters. Each presentation and question-and-answer session lasted ~20–30 min. Students in a group supervision were expected to learn from other students' discussion and then apply it to their own writing.

3.2 Data analysis and theoretical operationalization

Thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2021) was used to identify recurring patterns from the negotiated interaction between the students and their supervisors. The thematic process was conducted with NVivo 14 software with a reflexive approach, allowing the coding process to occur organically without pre-set codes or a codebook. The first step was data familiarization by reading the transcriptions and watching the videos iteratively. The selected transcriptions considered relevant for the type of negotiated interaction were then highlighted and coded. The analysis unit was explored within turn-taking between supervisors and students that covered trigger information and responses without concerning unit per sentence. The cyclical coding process was conducted to explore the negotiation patterns. The next step was constructing and collating relevant codes that fit together into a theme, for instance, the following codes—(1) mention writing anxiety and laugh anxiously, (2) mention inaccessible writing skills and cry, and (3) mention research challenges and sigh heavily—were categorized into the theme of students' emotional responses to feedback. Thereafter, the themes were reviewed, modified, and redeveloped to determine if they were appropriate or overlapped. The themes from each supervisory dyad were refined and compared to build concurrent themes among the data set. The emerging themes were defined to identify the essence of the supervision interaction. For example, the theme for students' emotional responses to feedback was redefined as managing students' emotional expression to accurately represent what was negotiated by the students and supervisors. Other researchers were consulted to review the themes and ensure the thematic appropriateness and representativeness of the investigated data. Lastly, the themes were written and presented. For data presentation, some selected and relevant Indonesian excerpts were translated to English5.

The concept of learning community (Reznitskaya and Gregory, 2013) was used to analyze whether and how the turn-taking of supervisory interaction facilitated the development of students' argumentative skills and the students' awareness of disciplinary knowledge. It focused on how the interaction between students and supervisors enabled students to actively engage in the conversation as a form of academic socialization. One example was when supervisors negotiated unclear ideas and prompted dialogue by asking students a question. Here, the learning community concept was applied to evaluate whether the question focused on (1) students' rational development or on (2) imposing supervisors' ideas. The students' rational development was evident when the question stimulated dynamic interactions between the supervisors and students and lead to flexible turn-sharing and the co-creating of a collaborative meaning (dialogic purpose). The imposing of supervisors' ideas was evident when the question used students' responses as an instrument to further the supervisors' communication goals (monologic purpose). It considers whether the student–teacher interaction becomes institutional talk, where supervisors gatekeep the knowledge and focus on correcting students, control turn-taking and sequence organization, and have “greater rights to initiate and close sequences” of conversation to pursue their didactic intentions (Gardner, 2013, p. 593).

4 Findings

In this section, the emerging themes of negotiated interaction in Swedish and Indonesian supervisory contexts are presented in consecutive order. The study presents an overview of negotiated patterns, illustrating them with examples of interaction strategies between supervisors and students. Thematic subsections conclude each theme, elucidating overarching strategies. In the supervisory meetings, various negotiated interaction strategies are used by supervisors and students in both the Swedish and Indonesian contexts. The discussion in the Indonesian supervisory meetings was initiated by the students presenting their progress, prompting supervisors' questions. The Swedish supervisions were initiated by either the supervisors or the students. SS1 and SS4 initiated the discussion by stating their meeting agenda and expressing their main concern, whereas SS2 and SS3 let students initiate the meeting by mentioning their questions or concerns. Based on the analysis of the results, the negotiated interaction in both Swedish and Indonesian contexts are divided into three major themes: (1) managing correction, (2) managing scaffolding, and (3) managing students' emotional expressions. The negotiated interaction patterns and strategies in thesis supervision can be seen in Figure 1.

4.1 Managing correction

During the supervisory meetings, especially when discussing correction in whichever stage of the supervisory process, supervisors in both contexts point out students' mistakes, explain them, and suggest the required revision, which leads to students' various responses. Some students frequently confirm or ask for confirmation, while others tend to respond fault-finding explanation defensively. One example of an acceptance response to correction occurs in the dialogue between Swedish supervisor 4 (SS4) and student H (see Excerpt 1 in Supplementary Appendix 1). During a meeting in the middle of the supervision process, SS4 initiates the dialogue by pointing out two main concerns (scholarly ideas and stylistic problems). SS4 mentions that H “leans a lot on Freud's uncanny” to analyze a video game and H's presented ideas insinuate that H “satisfy [themself] with relating everything to Freud,” to which H responds, “Hmmm….” As H does not give a full response, SS4 further explains that the presented ideas lack other scholars' examples of “how the uncanny is worked into representations,” which makes it “isolated and lack[ing in] critical context.” SS4 also adds that H uses a lot of gaming terms that “average readers don't know” and suggests that H not use words that only the gaming community can understand. SS4 also positions as a reader and asks, “What is going on here?”, to help H to be more aware of the need for clarity in their draft. Despite that the supervisor explained the faults thoroughly, H replies with minimum responses: “Yeah. Hmm…okay” and smiles when the supervisor gives explanations and suggestions. This conversation tends to be dominated by the supervisor who convinces H by explaining what the errors are and why certain issues are problems. In addition to explaining and suggesting, SS4 uses strategies in the form of (1) showing examples of how each subculture shares a specific discourse and (2) using reader response to motivate students to revise their draft and make it more understandable for the readers. Here, the student does not use any dialogic strategy to engage the conversation other than confirm the supervisor's explanation.

While H is more agreeable to the fault-finding critique, students in the other supervisory meetings tend to be defensive. One example is from Swedish supervisor 1 (SS1) and Students A and B (see Excerpt 2 in Supplementary Appendix 1), who discuss the students' research on teachers' perspectives on students' learning motivation during COVID-19. In the beginning of supervisory process, SS1 points out ideas jump from the issue of health in the school system and how this affects learning motivation to the pandemic and the need to use a hyphen to write “COVID-19.” SS1 explains that the supervisor deletes and rewrites some sentences to show how to revise them and compliments their correction as “snappy [and] clear,” which makes the suggestion and compliment seem rather imposing. Although SS1 invites the students to think about the suggested correction by saying, “You have to review it to ensure this is exactly what you want to say,” it seems that the complimenting supervisor's own revision leads to a negative response. Student A denies the errors by saying, “We actually don't know how that part got into our draft because we discussed it and decided to remove the pandemic parts.” Student A's deflection of their errors despite that it is in the draft leads SS1 to show the evidence of errors: “This is throughout this document that you sent. There is a heavy element of the pandemic element there.” SS1 also reminds Student A by stating, “If you decide to drop it [the subject of the COVID-19 pandemic], that has an effect” to which Student A confirms, “Oh, okay.” Despite the possibility that Student A's agreement might only relate to the undeniable proof that is shown by the supervisor, SS1 redirects the dialogue by restating the students' main issue: language inconsistency that creates unclear ideas.

In this situation, Student A might not understand that adding the COVID-19 pandemic in the draft becomes an essential element because they discuss learning motivation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hence, dropping it will insinuate that their research is conducted at any time other than during COVID-19 pandemic and disregard several factors that might influence teaching and learning motivation during COVID-19 pandemic. Instead of explaining the importance of “COVID-19” in creating the students' research setting, SS1 assertively restates the required revision: “You're going to have to be a bit tighter in your writing and clearer and more concise, so that we know exactly what you want to do” and then comforts the student by saying, “Don't worry about that at the moment. Let's run through what we've got in front of us and see how you feel about it, and you can consider it afterwards.” SS1 also reiterates the proof of students' error: “But in any case, COVID was there a couple of [times]. That was what I have.” Based on the conversation, the supervisor's fault-finding explanation led to a student's defensive response and the supervisor's more assertive suggestion. To convince the students to revise their draft, the supervisor focused on showing the students' the specific errors and emphasizing the need for revision.

From the situation, the supervisor focused on raising students' awareness of their mistakes and the need for correction by using several strategies: (1) showing the revision that the supervisor has made as an example and suggesting it as an alternative for students to ponder, (2) praising the supervisor's own suggested revision as a revision model, (3) showing evidence of errors and restating the need for revision to respond students' defensiveness, and (4) comforting students. While the supervisor restated the need for correction, which seems irrefutable, the students negotiated the interaction by (1) denying the fault-finding explanation, and (2) then agreeing on the need for revision after hearing the repeated explanation.

Other examples of students' defensive response toward the pointed correction can also be found in the middle of the supervisory process between Swedish Supervisor 3 (SS3) and Student G, who discuss citation errors (see Excerpt 3 in Supplementary Appendix 1). While other supervisors directly point out a mistake and follow it with explanation, SS3 questions students to get confirmation, gives correction, and explains the mistakes. When Student G makes an incorrect in-text citation to secondary resources by using “citing” instead of “in” and misuses the authors' surnames, SS3 asks, “Whose paper do you write?” and “Are you sure this is switching?” to get the student's clarification. After the students' answer, SS3 makes correction: “It should be like Chuck et al. in Bozkurt and Sharma,” to which G responds with a combination of confirmation, “Okay, in, okay,” and a defensive reply: “I've done that before with writing as well, for example, in Pintrich citing (Pintrich and Schunk, 2002).” Student G uses this retrospective approach to show that they are knowledgeable about the citation use: “I know that works because I've used that previously” and “I don't want to repeat sort of the same sentence all the time […] just to keep it varied.” Responding to the students' defense, SS3 explains citation rules: “Usually you put the paper that you read at the end. But here, it's like hmmm citing. It's either in or via or as cited by,” to which, G confirms, “Okay, yeah.” Student G asks for further clarification about whether to cite the original author: “Do I then need the reference to Chuck et al. and Golden?”, to which, SS3 says “no.”

Similar interactional patterns occur when the supervisor points out the misuse of a Chinese author's surname. When SS3 asks G whether the name has been reversed, G replies ambivalently that it is, followed by seeking clarification: “I am pretty sure, yes. Or?” to which SS3 explains the citation rule: “It's supposed to be the surname, and I'm not sure Hui Ching is a surname.” When SS3 mentions “I know. It is pretty confusing with the Chinese and Japanese names because of the inversions of their surnames,” G responds guardedly by saying, “I usually have a pretty good eye for it, though. Just not this time,” indicating that G uses excuses to save face due to confusion over a simple naming system. G's defensive response triggers SS3 to state the indisputable convention: “The rule of thumb is they don't have like two-word surnames,” to which G says, “Okay. Yeah. All right.” The turn-taking interaction in this conversation indicates that the supervisor asks for G's confirmation to perpetuate their explanation which seemingly embarrasses G. Student G's nervous laughter, and defensive excuses lead to the supervisor's more assertive strategy.

From the dialogue between G and SS3, both supervisor and student share confirmatory questions to negotiate correction while using different strategies to follow-up the fault-finding. The supervisor uses strategies that (1) suggest correction and (2) explain irrefutable citation rules and naming system. Apart from seeking clarification, the student uses two strategies: (1) retrospective responses by referring to previous works and (2) face-saving strategies. Student G might assume that “citing” is acceptable because they previously used it, and it can be used creatively. However, Student G seems unaware that “citing” to refer to indirect citation does not align with APA 7 reference style, which G needs to follow. Furthermore, G makes justifications to maintain a positive self-image as a competent student.

The recurring defensive responses to fault-finding explanation that aims for correction also occurs in the dialogue between Indonesian Supervisor 1 (IS1) and Student L, which takes place near the end of the supervision process (see Excerpt 4 in Supplementary Appendix 1). In this dialogue, L presents the thematic analysis results from interviews that focus on pre-service teachers' teaching experience. When L presents the themes, IS1 finds that L's themes have not been specifically grouped, so IS1 points out, “The theme is pre-service teachers” [instead of emotional aspect]. IS1 suggests, “Focus on the major findings first. The emergent findings are for later,” implying that the student has mixed the main and emergent findings. In this conversation, Student L deflects accountability by explaining, “But these findings are based on the previous supervision,” to which IS1 also responds defensively, “How? How? Why?”.

The conversation gets more interactive when L reminds IS1 of previous supervision: “This emotional aspect has been included for findings,” deflecting accountability. IS1 responds by correcting, “That is the story. But it has not been discussed yet, has it?”, to which L confirms, “Yeah.” IS1 further affirms the need for revision: “It also has to be discussed” and then guides the students to structure the themes. When L asks for confirmation, “What about the activity? Is it included [as a theme] or not?”, IS1 asks the confirmatory question, “Does the activity belong to a lesson plan?” to prompt L to think about it. When L does not answer the guiding questions correctly, IS1 gives the answer by saying, “It is more like teaching delivery in the classroom, right? … It means that the activity is not the main finding. The main findings are the lesson plan and emotion.” Student L agrees with “mm-hmm.” In this situation, the interaction tends to focus on correction as an end goal. In the beginning of the conversation, the student seems to take a risk by arguing and deflecting accountability. However, the student later plays it safe by asking for confirmation and confirming supervisor's explanation after receiving reiterative fault-finding explanations. The student may not know or helpless to directly answer the supervisor's “How and Why.”

From the dialogue between IS1 and L, the supervisor tends to give students correction with limited explanation. Even though SS1 mentions that the themes need to be discussed and L's draft is still in the form of story rather than discussion that covers analysis and evaluation, there is no further explanation as to how to discuss the themes. Despite the possibility that L might be unaware of how to link the themes and theory to discuss the research results, the supervisor focuses more on thematic grouping which seems to be more urgent in this dialogue. To manage correction, the supervisor uses the following strategies: (1) suggesting the student focus on main findings, (2) using counter-defensive tactics and repeated fault-finding explanations to respond to students who deflect accountability, and (3) guiding students to make their corrections by asking confirmatory questions and giving direct answers when the student gives incorrect answers. To negotiate the interaction, the student uses the following strategies: (1) deflecting accountability after fault-finding explanations and (2) asking for confirmation about suggested ideas.

Overall, the managing correction theme is negotiated by combining the fault-finding explanations, suggestions, and reciprocal confirmations between students and supervisors. The examples show that managing correction tends to lead to various responses and strategies to negotiate the interaction. When students are more agreeable with the fault-finding explanations, the interaction tends to be more of a one-way conversation, where supervisors explain and suggest revision and students give few responses. In contrast, the interaction becomes more of a two-way conversation when students defend the faults. From the dialogues, Student A distances themself from responsibility by denying their mistakes, Student G uses retrospective and face-saving strategies, and Student L deflects accountability to the supervisor whenever they encounter fault-finding explanations. The students' defensive strategies toward fault-finding explanations triggers supervisors to use more assertive suggestions to convince students. In this situation, upon showing the errors, supervisors always give explanations and suggestions with additional strategies, repeatedly mention the specific needed revision, and explain nondebatable conventions.

4.2 Managing scaffolding

Apart from managing correction, supervisors negotiate provided feedback to manage scaffolding to help students to co-construct their argumentation and engage in discussion. Supervisors ask analytical questions and follow them by providing suggestions and explanations. Despite the expected analytical reasonings, students' responses to these questions vary. They can be in the form of brief reasonings, elaborative explanations, doubtful expression with requests for clarification, and even deviant cases where students laugh, confirm, or keep silent rather than provide analytical responses.

The first example of managing scaffolding theme is with the dialogue between Indonesian Supervisor 2 (IS2) and Student N at the beginning of supervisory process (see Excerpt 5 in Supplementary Appendix 1). They discuss N's intention to investigate whether the modules used by private tutoring institution that offers service for national exam preparation cover higher order of thinking skills (HoTs) elements or not. When N initiates the dialogue by presenting their research objective, the supervisor uses different questions to invite N to engage in conversation and develop their reasoning. Here, IS2 prompts questions to trigger N's analytical reasoning as to why the module is considered to have HoTs by asking, “Why do you say ‘HoTs'? Why do you think that?” However, N appears unfamiliar with how to argue convincingly by explaining, “Students are trained to practice using HoTs exercise. Their thinking becomes more [pause] this is the way of thinking, maybe,” to which IS2 follows up, “Is it?” to help N shapes their argument. Student N nervously laughs and gives another superficial reason: “Because usually HoTs questions are more difficult than LoTs. So, they [students] seem to have to analyze the problem as well,” indicating that N has not fully addressed the question of why the module covers HoTs. When N assumes that “a lot of texts use HoTs patterns or increases HoTS,” IS2 assertively suggests, “It needs to be clarified, […] proven, […] and N must have examples.”

Instead of explaining the importance of approaching research with an open mind without preconceived notions or biases, IS2 suggests examples to convince readers, “Trust me, SBMPTN uses HoTs. […] This is what it looks like when using HoTs.” IS2 presumably notices that N is getting overwhelmed by consecutive exploratory questions when N mumbles “Okay,” to which IS2 comforts N by saying, “It's actually good, very interesting topic.” In this conversation, the exploratory questions are intended to facilitate N to develop their analytical reasonings. However, those questions overwhelmed the student. Student N may need more time to answer the questions comprehensively because some questions need further investigation or deeper conceptual understanding. Hence, some questions remained unanswered (e.g., “What is it called? Is it an effective strategy to succeed SBMPTN? Is the strategy for getting admitted through SBMPTN by mastering HoTs?”).

The dialogue between IS2 and N indicates that the scaffolding is negotiated through prompt questions and suggestive comments. IS2 applies strategies by (1) prompting questions, (2) explaining the need to prove a hypothesis, (3) suggesting convincing readers about the research ideas, and (4) comforting students. The provision of prompted questions led to the students' superficial reasonings but overwhelmed them when they missed answering several questions. To negotiate the interaction, Student N used the following strategies: (1) providing short reasoning, (2) asking for clarification, and (3) confirming the questions.

Another example of managing scaffolding through questions is in the dialogue between SS3 and Student G at the beginning of the supervisory process (see Excerpt 6 in Supplementary Appendix 1). Student G intends to investigate teachers' remote teaching practices during the COVID-19 pandemic, yet the reasoning in the Introduction is still unclear. When SS3 questions the way G presents ideas, the student explains the intention to “elaborate on the ELT” and “what the lack of definition in the Swedish context,” remove the commented parts and “hadn't [re-]organized it since.” Student G's responses seemingly indicate reasonable answers, to which SS3 further questions, “What do you think about these contextual parameters?” to encourage G to provide an opinion, to which G explains,

I didn't put just put it as a placeholder title, really. […] what I'm essentially doing in that segment is providing context how has Sweden reacted to this. […] That study essentially goes into […] teacher preparedness, […] the essential tools they needed, and what they sort of an evaluation on what they thought worked well, and what didn't work well. […] So, it's a very good article for me to use in the analysis like that. Specifically, as it relates to the two sub-questions.

Student G's reasonings to provide research context and use the article as a relevant source are seemingly reasonable, to which SS3 moves on to another question: “What about COVID and education in Sweden?” In this situation, G indicates a deviant response by saying, “Yeah” to the question because G does not provide the expected reasons for why adding COVID-19 and education in Sweden are important ideas for their draft. It leads to an intervening conversation, where the supervisor suggests revisions by pointing out, “You basically need to unpack those [ideas]” and use analogy,

I have this sword. I have this mace. I have this arrow. I'm going to use this sword to kill this general. And for that general, I need to shoot that with the arrow. But then you are presenting the weapons first here (SS3).

The supervisor uses the gaming analogy of weapons to trigger G to comprehend those weapons refer to different concepts and that every concept that will be used in the analysis section must be explained in the Introduction. It seems that G understands this analogy by confirming SS3. In this conversation, the scaffolding is managed through different questions, and the supervisor intervenes with suggestions when the student's responses lack depth. SS3 combines the following strategies: (1) asking confirming and probing questions to invite the student's reasoning, (2) restating the need for revision, and (3) using analogy to contextualize the suggestions. To respond the supervisor's scaffolding, the student uses the following strategies: (1) providing stance and reasoning when they are sure about the answer to the questions and (2) confirming when in agreement, but when unsure, resort to deviant answers.

Another recurring theme in managing scaffolding occurs in the middle of a supervisory process that involves Swedish Supervisor 2 (SS2) and Students E and F (see Excerpt 7 in Supplementary Appendix 1). When they discuss the preliminary finding whether Swales' CARS template is used to structure the Introduction section for the degree project, SS2 praises the students' work: “I'm really interested in the analysis you've done” and asks, “How do you work with this text?” Student E replies by stating that both E and F discuss how they collaborate to find different rhetorical moves in the investigated text. Student E then seeks clarification: “Have they even had the same template?” to which, SS2 explains that the university “ha[s] given people the template, but the supervisors have not really yet accepted it as such.”

In the conversation, a recurring pattern emerges wherein the supervisor shifts from posing exploratory questions to intervening in the interaction with suggestions and explanations whenever students show misunderstanding or a lack awareness of the answers. For instance, after hearing the clarification of the provided template, E assumes that the investigated text possibly shared typical rhetorical moves due to the existence of template: “If we're talking academic conventions, I mean, there is a lot of discuss[ion] there. Definitely.” As a response, SS2 explains, “If you look at the introductions in the articles, they are all different too really, but they're still this kind of and structure present.” SS2's response indicates that, despite the provided template, there is still a possibility to find different Introduction styles with certain rhetorical moves.

SS2 further asks, “What amount of scaffolding is acceptable to still be able to be independent?”, to which E gives the minimum response, “Yeah,” indicating that E is unsure of the answer. When E enthusiastically shares their research planning, “I would personally love to go into the teaching implications of this,” SS2 replies “hmmm,” signaling that SS2 may consider that E is only interested in pedagogical implications without actually planning on examining it in the investigated texts. SS2 thus suggests that students reflect on their previous work by asking, “Do you have your own examensarbete [bachelor thesis]? Maybe that could be something you can look at?”, to which F responds hesitantly, “It feels like opening Pandora's box.” When F further expresses their intention to examine teaching implication: “I'm very intrigued [sic: about the] pedagogical implications” because “the authors for the [investigated] papers understand the convention,” SS2 seems to notice the students have misunderstanding and explains, “I really must emphasize that the pedagogical implication of what you're doing now is at the heart of your project […] We don't teach [sic: Swales'] moves either. We come to move on the PhD level.” Here, SS2 highlights that Swales' moves are taught at the PhD level, not master's level—the level of Degree Project that the students are investigating. Although it is impossible to understand teaching practices by investigating rhetorical moves in Degree Project, it is unclear why SS2 does not explain that students require different research designs other than document analysis.

From the dialogue between SS2 and Students E and F, the supervisor uses some strategies to manage their scaffolding by (1) praising students' work to motivate students' response, (2) asking questions to invite students' reasoning and give suggestions, and (3) providing explanations to address students' misunderstandings. To respond the supervisor's strategies to manage scaffolding, students (1) explain what they have done, (2) ask for clarification, and (3) provide reasonings about what they are planning to do. The different uses of questions as suggestions and prompts for information along with compliments seems helpful for creating a more relaxed and two-way conversation.

Overall, managing scaffolding through probing questions seems helpful to invite students' engagement. When students are sure of the answer, they give their stance and the reasons for their choices and plans. However, deviant cases frequently occur when students do not give the expected answers. Supervisors in both contexts frequently use the following consecutive strategies: (1) asking confirmatory questions or praising students' work, (2) prompting exploratory questions to invite deeper reasonings, (3) suggesting revision, (4) providing explanations to answer students' clarification requests and responding to students' minimum or deviant responses, which typically occurs due to students' doubtful answers, and (5) comforting students. Regarding students' strategies to negotiate scaffolding, students mostly (1) express their reasons and stance, (2) confirm the explanation, (3) ask for clarification, and (4) give minimum responses to exploratory questions to get further explanation. Despite using different expressions, students' responses signal the need for more scaffolding to formulate coherent rationales and to understand the fundamental principle of research, given that they show epistemological naivety and deviant responses.

4.3 Managing students' emotional expressions

While managing correction and managing scaffolding are initiated either by the students or the supervisors, managing students' emotional expressions is frequently prompted by the students' confession of emotional distress for various reasons. For instance, students experience stress due to unfamiliarity with academic conventions or are overwhelmed by the thesis process. These emotional expressions occur throughout the supervisory process and are expressed in the form of nervous laughter, crying, and confessions of anxiety or nervousness. Some students express having writing anxiety and confusion regarding the research focus in the early phase of the supervisory process, particularly when they discuss research questions, while other students convey challenges in the middle of the supervisory process, particularly when they encounter problems creating research instruments or analyzing data. In the last phase of the supervision process, students experience difficulty with drawing conclusions from their research analysis. In situations where students' emotional reactions are visible, the supervisors use different strategies. In this section, I present students' emotional expressions due to unfamiliarity with academic conventions, followed by students' emotional expressions due to feeling overwhelmed to illustrate how various strategies are used.

Students' emotional expressions due to unfamiliarity with academic convention is managed through various strategies. In one example (see Excerpt 8 in Supplementary Appendix 1), student O is nervous and expresses concern: “I will not be able to think of its implication for education […] I'm confused and a bit nervous writing it,” to which the supervisor, IS2, tries to calm the student by explaining, “Please do not think about the education implication. That's later on.” IS2 addresses O's problem as “overthinking” and instead encourages them to

Just write. Where will O end up? We don't know. Of course, we have the research question, but we don't know what we will find. […] We have no knowledge whatsoever of what or where we are heading. So, go on and keep searching. What is the message of this analysis? That is the question you need to answer during the thesis defense.

IS2 reassures the student and encourages them to keep going. To manage students' emotional response due to their unfamiliarity of academic conventions, expressed here as nervous laughter, IS2 uses the famous author JK Rowling to show that writing is a journey where one will figure out the goal while one is writing. When the student's response is to laugh nervously, IS2 continues to encourage the student to keep writing by using their personal experience as an example: “When I wrote my doctoral thesis, it was started with random ideas. In the beginning, I wrote every thought: random and ridiculous. I fell here and there until, okay, I find my own base.” In addition to referring to their personal experience, IS2 continues to encourage the student by reminding them that “You will not be able to write if you seek perfection.” In this situation, where the student is emotional due to their unfamiliarity with academic conventions, the supervisor uses two strategies besides explaining and encouraging: (1) using an example that they think that the student recognizes (JK Rowling) and (2) using their own personal experiences as a way to demonstrate that it is possible. In this discussion, the student (1) gives a minimal response and (2) asks for clarification.

Another example of managing students' emotional expressions due to unfamiliarity with academic convention can be seen in the dialogue between IS1 and Student K, which takes place at the end of the supervision process (see Excerpt 9 in Supplementary Appendix 1). The supervisor (IS1) asks Student K, “If someone asks you, what are your findings? Can you list it in three points?”, K laughs nervously and ask for clarification, “finding?”, indicating K's unfamiliarity with the possibility of creating a take-away message from the research findings. In this conversation, K has challenges drawing conclusions by retelling a story in the Conclusion, to which IS1 keeps reminding, “You're no longer retelling the story here. Summarize it. Do not talk in detail. […] Don't retell the story.” IS1's repeated advice to not retell the story in the Conclusion leads to K laughing nervously and K confesses, “I don't know. I'm confused now [laughs nervously]. I'll think about it,” to which IS1 keeps advising not to retell the story. IS1 also checks K's understanding: “Do you know what the differences are [between concluding and retelling the story]?”, but it becomes explicit feedback provision because K seeks confirmation: “Is it summarizing the statement?” Thereafter, instead of explaining how to draw conclusions, IS1 gives a concrete example: “The statement will be the cultural adaptation process needs, for example, emotional adaptation, too.” IS1 invites K to think about other examples: “Can you think of other examples? What are they?”, to which K gives the deviant response, “Okay,” rather than give examples of closure statements for conclusions.

From this dialogue, IS1 manages the student's emotional responses expressed as nervous laughter and confessions by using the following strategies: (1) asking students to form a take-away message, (2) raising student's awareness of writing conventions by prohibiting story retelling, (3) providing a concrete example, and (4) inviting students to give examples. The student then uses the strategies of (1) asking for clarification and (2) giving a minimum response to get further explanation.

From both dialogues, it is clear that supervisors have different strategies to manage students' unfamiliarity with academic conventions. These might relate to the phase of supervision, where more space to explore is given in the beginning of the supervisory process. Limited space to explore is given to students near the end of the supervisory process. Here, IS2 navigates the student's emotional challenges in the beginning of supervision process with less imposing ideas. IS2 approaches the students' unfamiliarity with academic conventions by (1) raising the students' unawareness of the problem, (2) socializing that academic writing is a systematic yet creative process, and (3) explaining that writing confusion is a common thing that can be solved by using free writing strategies to jot down ideas and create progress. In contrast, IS1 navigates the student's emotional expressions by (1) raising the students' awareness of writing conventions by asking them to summarize the findings and prohibiting repetition in the Conclusion, (2) asking for confirmation about their understanding of the conventions, and (3) providing concrete suggestion. Despite the strategies that supervisors use to manage the students' emotional expressions, both students have similar strategies by (1) giving minimum responses and (2) asking for clarification.

Apart from experiencing unfamiliarity with academic conventions, the students express emotions due to feeling overwhelmed. One example is from the dialogue between Swedish Supervisor 1 (SS1) and Students A and B, where the students still have unclear ideas before going to the thesis defense (see Excerpt 10 in Supplementary Appendix 1). When Student A sighs deeply and expresses, “I don't know where I'm going, but my brain doesn't communicate to my hands,” SS1 explains the core of academic writing: “It has to be simple […], clear” where “a reader […] should potentially be able to jump in any part,” and the readers may not read the whole draft. Here, SS1 directs students toward problem-solving strategies for addressing unclear ideas rather than validate their emotions. SS1 also emphasizes the need for increased effort, stating, “You've had lots of work before tomorrow” eliciting silence from the students in response.

The students show more engagement when SS1 raises the possibility of withholding approval for the thesis defense: “I really don't want to have to be in a situation where I can't give a go ahead.” The students might feel stress or anxiety, so Student A praises SS1's feedback by saying, “We understand that, and that's why basically we're very thankful that we could have a meeting today.” Student A also tries to reassure the supervisor that they understand what they should do: “When we have read it […] it became more clearer for us. […] We know what we're supposed to have there,” which is agreed by B who says, “Structural [correction on organization] help[s] us a lot.” The students' nervous laughter prompts SS1 to say, “Work as hard as you can guys […] think realistically as well about the situation when you see the product.” Here, the supervisor uses the following strategies: (1) explaining what students should do and (2) encouraging students to work harder because they have limited time. While the supervisor focuses more on the need for students to revise their drafts and show more effort, the students respond by (1) praising the supervisor's feedback and (2) ensuring that they understand what revision they need to do.

Another recurring example of the students' feeling overwhelmed during the writing process occurs to Students E and F in the middle of the supervisory process (see Excerpt 11 in Supplementary Appendix 1). When discussing preliminary findings with SS2, both students cry. When Student E expresses their stress from not being able to “access their good potential in writing” and cries, SS2 shifts from validating the students' challenges in “doing something new” in “less than 10 weeks” to repeatedly complimenting the students as being “clever,” explaining that their draft is “good,” like “a rough diamond,” and “shaping up very well.” The students do not react to SS2 referring to their draft as a rough diamond, possibly considering it hyperbole. However, the students actively respond to the supervisor's confirmation that they are still “processing, digesting, and working on new stuff,” possibly indicating that they want more reassurance and to feel understood. In addition to validating the students' challenges and praising their work, SS2 also encourages them to “be realistic and be kind to themselves,” reminding them that “writing is not easy” and “will not go exactly the same way” as they have experienced before—another validation that their process is challenging. It seems that SS2's validation and encouragement increased the students' confidence, as the students motivate each other for being clever problem solvers, like the famous detectives Sherlock Holmes and John Watson, indicating that they can solve the problems. This dialogue shows how students might get overwhelmed because they need to learn and apply thematic analysis to analyze papers based on a specific linguistic model—a new experience for them. They also have limited time to finish their thesis. Also, their research is a part of their supervisors' larger project, which may lead to more confusion and responsibility. To manage students' emotional expressions such as crying, the supervisor uses the following strategies: (1) validating students' challenges, (2) complimenting students' work, and (3) reminding students that the writing process is challenging. In this dialogue, the students possibly seek encouragement and validation since they only respond to the supervisor with “Yeah.” Later, the students encourage each other after receiving repeated encouragement from the supervisor.

Similar challenges of feeling overwhelmed occur in the supervisory session between Swedish Supervisor 4 (SS4) and Student H, which takes place at the end of the supervisory process (see Excerpt 12 in Supplementary Appendix 1). In this dialogue, the supervisor (SS4) makes the transition from straightforwardly confirming the student's problems to validating the student's emotional expression and encouraging them. In the beginning, SS4 explains the problem: “I felt that this was the weakest part” without addressing the student's emotion when H expresses unhappiness with their draft. SS4 changes strategy to that of encouragement after hearing H sigh heavily and say, “I was a bit stressed by the amount [of words] as well,” mentioning that the word limit “totally affect[s] your grade” and “I struggled a lot with the conclusion.” H's expressions trigger SS4 to calm H, telling the student “not to worry with the word limits.” SS4 then suggests that H “reconsider the conclusion and not worry about too many pages” and encourages: “you could make conclusion much more pointy and much more brave.”

The supervisor mentions the possibility to be the expert in a video game by enthusiastically saying “at some poin[t], it will be Professor [mentioning H's full name] after you finished a PhD in game studies,” to which H asks, “You think I'm gonna pass?” In this situation, Student H focuses more on passing the thesis defense regardless of SS4's encouragement, to which SS4 changes the strategy: “Passing is not the problem. […] If people don't see it the way I see it, the person who's grading you, then maybe you won't get the top grade.” SS4's response refers to the grading assessment, which requires students to create clear drafts. The supervisor might feel disheartened, which is evident from a heavy sigh after hearing the student focus on the grade, thus shifting from giving enthusiastic encouragement to referring to their dependence on the examiner's decision. Student H then replies aloofly with nervous laughter: “I'm not going to be offended if I don't get a high grade” and adds, “I struggled a lot, and I'm really proud that I was able to at least write something despite the pandemic and being less than motivated to do it,” SS4 repeatedly confirms and praises Student H's efforts:

I think you've worked hard, and I think that you've worked well. […] I appreciate what you've done. I do. I think you've done well, H. I think that you should be proud of yourself, and you're actually contributing to new knowledge.

It seems that both H and SS4 change strategies to negotiate their messages. When H does not get emotional support, H expresses their unhappiness, to which SS4 repeatedly calms and encourages them. H also shows disengagement when SS4 mentions the grading authority. SS4 then responds by offering encouragement, giving emotional validation, and pointing out required revisions. Based on the dialogue, the supervisor manages the student's emotional expressions by (1) calming the student, (2) suggesting the student focus on the draft content rather than the word limit, (3) affirming the student's ability to create good conclusions, (4) encouraging the student to be optimistic and (5) referring to the need to create clear drafts. When the supervisor focuses on encouraging H, the student negotiates their emotions by (1) expressing emotional distress to receive validation and (2) asking for reassurance that they will get the degree.

Overall, the management of students' emotional expressions in this study presents a nuanced challenge, where supervisors balance boosting students' confidence and validating their feelings with emphasizing the need for revision. Recurring examples illustrate how students seek reassurance and emotional validation amid their unfamiliarity with academic conventions and sense of being overwhelmed, which requires a delicate approach. Students express their emotions mainly through nervous laughter and confessing that they feel anxious or confused. Instances of feeling overwhelmed, including crying, necessitate targeted encouragement where the supervisor specifically uses the supervisory sessions to address the students' emotional expressions.

Although the students in both contexts ask for confirmation, the supervisors use different strategies to manage their emotions. For instance, SS1 and IS1 consistently mention revisions, while SS4 addresses discrepancies in the student's goals. SS2, SS4, and IS2 adopt a nurturing approach by (1) validating challenges and (2) providing encouragement, whereas others (3) focus on problem-solving and (4) detach themselves from validating the students' emotional expressions. These emotional expressions may stem from internal factors such as writing anxiety and unfamiliarity with academic conventions or external factors like time constraints (for Swedish students) and publication demands (for Indonesian students). In this study, the Swedish students faced a tighter 10-week thesis deadline compared to the Indonesian students' more flexible timeline (32 weeks). However, the Indonesian students faced more pressure to publish in peer-reviewed journals as the degree requirement.

5 Discussion

This study explores how supervisory interactions between students and supervisors are negotiated through feedback provision in EAL supervisory contexts to identify the patterns and strategies of negotiated interaction between students and supervisors in Swedish and Indonesian thesis supervisory meetings. To further understand the use of patterns and strategies of negotiated interaction in supervisory meetings to help students develop argumentation, the learning community is discussed.

5.1 Negotiated interaction patterns and strategies

In response to the first research question about how the supervisory interaction is negotiated, the findings show that the interaction can be categorized into three major themes: (1) managing correction, (2) managing scaffolding, and (3) managing students' emotional expressions. In line with Varonis and Gass's (1985) ideas of negotiated interaction patterns, the supervisory interactions in this study were triggered by students' unclear ideas in the thesis drafts (Swedish context) or the presentations during supervisory sessions (Indonesian context) that prompted responses to achieve shared understanding. Some of supervisors' questions in this study remain unanswered—a situation which Varonis and Gass (1985) might consider a communication breakdown or a deviant case, given that the students did not provide the expected answers. However, the students' deviant responses led to supervisors' further explanations or suggestions, indicating that “the deviant” can trigger communication and become a strategy that leads to scaffolding rather than a “breakdown” in communication. In line with Yerushalmi's (2014) study, students and supervisors in the current study also reciprocally exercise their knowledge, even though the students' formulated knowledge is presumably challenged more than their intuitive knowledge during the supervisory sessions. This is because the conversation is situated in the academic context, particularly when students have less developed academic and research literacies.

The supervisory interactions in Swedish and Indonesian contexts seem to follow Tecedor's (2023) ideas of negotiated interaction. The supervisory meetings are intended to negotiate of meaning (NoM) and negotiate of form (NoF). The examples demonstrate that the supervisors in both contexts frequently prompt explorative questions to address NoM, which focuses on the macro level (i.e., idea development, take-aways from the research, and narrative perspectives) and point out language use to address NoF. However, students frequently give superficial rather than the expected in-depth answers that address NoM and have problems with micro level, leading the conversation to focus more on this level (i.e., jumping ideas, citation errors, conclusion inference, and the use of specific terms such as “COVID-19”). One supervisor even revised students' sentence-level errors and showed these to the students as an example of how to revise.

In response to the second research question about negotiation strategy in thesis supervision, this study demonstrate that supervisors and students use different strategies. To address supervisory needs, the supervisors in both contexts used several strategies to manage correction by (1) explaining faults, (2) providing suggestions, (3) giving examples as models, and (4) highlighting the reader-response approach to show students how to create clearer drafts. The supervisors also employed assertive suggestions to deal with students who became defensive, which are frequently in the form of (5) showing evidence of errors, (6) explaining irrefutable rules, (7) using counter-defensive tactics, and (8) repeating the need for revision. To manage scaffolding, the supervisors commonly (1) used questions to prompt discussion, elicit students' reasonings, and in some cases, offered suggestions. Supervisors also provided (2) explanations and (3) suggestions in response to students' clarification requests, minimum responses, and deviant responses. In terms of managing students' emotional expressions due to unfamiliarity with academic conventions and feeling overwhelmed, supervisors used either detached or nurturing strategies. When using a detached strategy, the supervisors mainly focused on (1) providing a problem-solving explanation and (2) encouraging students to revise their drafts and to put in more effort without validating students' emotional expressions. A nurturing strategy was also used when supervisors (3) validated students' emotional expressions and then (4) encouraged them iteratively and (5) prompted them to write clearer drafts.

Although the supervisory interaction shared discursiveness, the students showed dependence on the supervisors' clarifications, which also occurs in Zackariasson's (2020) research results where students seek guidance on what they should do and how things should or could be done. The students mainly asked for clarification and confirmed the supervisors' suggestions, to which supervisors frequently dominated the conversation. This occurs when supervisors focus on corrections to which students might not know how to respond. In this study, the managing correction theme was negotiated through more intense pressure to revise the drafts rather than manage scaffolding intended to help students develop their argumentative skills. Furthermore, managing correction and scaffolding themes involve active negotiation that fosters a two-way conversation. In contrast, managing students' emotional expressions tends to be less interactive than managing correction and managing scaffolding. The different patterns of negotiated interaction are necessitated to address students' strategies. Some students mainly agree to supervisors' explanations and suggestions, while others frequently respond defensively to fault-finding by (1) denying the errors, (2) deflecting accountability, (3) using retrospective responses, and (4) saving face, which leads to supervisors' more assertive suggestions—create a two-way conversation.

Batstone (2016) explains that corrective feedback can be overwhelming or personally offensive. In the present study, the students' defensive responses to fault-finding are neither novel nor unexpected. Notwithstanding the defensive response tendency, students use different strategies to respond to exploratory questions to negotiate managing scaffolding. They frequently (5) offer detailed reasonings and perspectives when confident in their understanding, (6) seek clarification, and (7) provide minimal responses when uncertain, leading to deviant responses, which is a useful strategy for seeking further explanation. Zhao and Mills (2019) explain that supervision with open communication can foster reciprocal trust between supervisors and students. In the current study, the interaction was carried out with open communication where students seemingly trusted the supervisors enough to share their distress. They usually (8) expressed emotional distress to gain emotional validation and reassurance regarding the challenging thesis process, (9) provided minimal responses and (10) sought confirmation to negotiate their emotional expression. This study supports Ribeiro and Jiang's (2020) and Zhu and Carless' (2018) studies in that the use of feedback in student–supervisor interaction facilitates students to ask for clarification, confirm and check comprehension, elaborate ideas, and notice language correction.

5.2 Negotiated interaction through the lens of the learning community

The learning community theory (Reznitskaya and Gregory, 2013) asserts that dialogic inquiry enables students to develop their epistemological understanding, argumentative skills, and disciplinary knowledge through two-way interaction with others. Based on this understanding, the learning process, including supervisory interaction, is expected to cultivate transferable knowledge and argumentation skills that involves gradual and reciprocal internalization processes. In the present study, the supervisory interactions in both contexts seemingly aimed for developing dialogic inquiry by asking students questions either to manage correction or scaffold. Although the conversations focused on improving the students' drafts, they nevertheless used transferrable skills for different situations. During the supervisory process, the supervisors mostly invited students to engage in discussion, argue in clear academic writing, develop a logical structure for reasoning, provide evidence to support the argument(s), and use argumentative devices appropriately.

However, some students' responses indicate that their lack of academic literacy, research literacy, and ability to effectively communicate their research led them to feeling overwhelmed. Students are likely unable to reason critically because they are unfamiliar with research conduct and academic conventions, both for writing theses and negotiating feedback. Many have no previous experience in conducting individual empirical research and have not developed advanced intellectual capacities to engage in “more complex, nuanced, and meaningful disciplinary knowledge” (Reznitskaya and Gregory, 2013, p. 121). The examples show that students have problems such as formatting in-text citations properly, drawing conclusions, stating clear and analytical ideas, conducting thematic analyses, and showing an understanding of fundamental research principles. Although learning community aims to develop students' argumentative skills, the application of dialogic inquiry requires a high degree of literacy from the students in order to formulate and exercise their reasonings. Accordingly, the results show that students require more tools to navigate their argumentation.

Considering that an internalization process is required to develop students' argumentative skills, the supervisors' tendency to focus on correction and minor details, especially when managing correction, seems insufficient for giving the students' autonomy and providing them with an opportunity to challenge themselves. Feedback provision traditionally points out the strengths and weaknesses of student texts to prompt discussion between students and supervisors (Murray, 2011). It becomes more complex practice when students depend on supervisors' explanations and suggestions, thus turning the supervisory interaction into an institutional talk where supervisors lead the turn-taking to navigate their didactic intentions. This type of institutional talk also has been explained by Gardner (2013).

The results show that supervisors frequently gatekeep the information exchanges. The supervisors tend to ask students questions to investigate students' learning process rather than seek their incidental response as in common conversation. This suggests that this strategy may be common within the student–supervisor relationship as it is explained by Gardner (2013), particularly when students have limited research experience. In addition, the supervisors' help appears to be needed more for ensuring that their students revise their drafts and graduate on time than developing verbal argumentative skills during the supervisory sessions. This is inferred from the supervisors who tend to give concrete examples and explicit feedback on the micro level (i.e., reformulating sentences, correcting citation use, and restructuring themes). The findings suggest that the application of learning community concepts become more intricate when students and supervisors have divergent supervisory objectives and encounter time constraints for honing argumentative skills. Effective dialogic inquiry may be hindered when students rely excessively on supervisors. Therefore, the learning community must address the challenge of fostering macro-level argumentation development while still attending to micro-level corrections.