- The Levinsky-Wingate Academic College, Wingate Institute, Netanya, Israel

Introduction: This study investigates the dynamics of intranational intergroup contact between Arab and Jewish students in a higher education institution in Israel. Guided by the contact hypothesis, the research examines the gap between students’ willingness for intergroup closeness and their reported actual intergroup interactions.

Methods: Using a cross-sectional survey design, quantitative data were collected from a total of 733 Arab and Jewish students at two timepoints: in 2016 (n = 419) and in 2023 (n = 314). All students were studying to become physical education teachers.

Results: The findings revealed both persistent challenges and encouraging trends in intergroup relationships. Despite reported willingness for meaningful connections, the students’ reported actual intergroup interactions remained limited. A significant increase in willingness for academic and friendship relationships was observed from 2016 to 2023, suggesting the potential for constructive change. Arab students consistently reported higher willingness for closeness and more frequent interactions than their Jewish counterparts.

Discussion: These findings underscore the importance of structured interventions in higher education settings to foster meaningful intergroup relations, amidst broader societal challenges.

1 Introduction

One of the main goals of higher education is to develop intercultural competence among students. Higher education settings offer an ideal arena for encountering individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds, with the potential to develop students’ knowledge of different cultures and to enhance intercultural relations (Guo and Jamal, 2007; Deardorff and Arasaratnam, 2017; Makarova, 2021; Krishnan and Jin, 2022; Guillén-Yparrea and Ramírez-Montoya, 2023). It has been argued that the encounters with diverse cultures during higher education studies exposes students to varied perspectives, challenging them to think critically about their own beliefs and assumptions and promoting a more open-minded and adaptable thinking process. Such skills are essential for addressing complex demands in today’s rapidly changing and increasingly globalized world (Hu and Kuh, 2003; Pike and Kuh, 2006; Auschner, 2020). Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) can thereby contribute to the development of individuals who can navigate differences, negotiate disagreements, and learn to cooperate as a means for resolving conflicts (Heleta and Deardorff, 2017; Hakvoort et al., 2022).

Whether intercultural relations emerge organically, as a byproduct of the learning process, or whether deliberate, structured interventions are indispensable to foster meaningful connections is not yet clear. With the aim of addressing this question, this paper explores intercultural interactions in the natural environment of higher education.

1.1 Natural intercultural interactions

The term ‘intercultural competence’ is a multifaceted concept that has been defined and theorized in diverse ways (Salih and Omar, 2021; Allen, 2022). Deardorff (2004) defines intercultural competence as “the ability to communicate effectively and appropriately in intercultural situations based on one’s intercultural knowledge, skills, and attitudes” (p. 194). According to Byram et al. (2001), it is “the ability to interact with ‘others’, to accept other perspectives and perceptions of the world, to mediate between different perspectives, and to be conscious of their evaluations of difference” (p. 5). Byram (1997) and Byram et al. (2001) model of Intercultural Communicative Competence includes five key components: knowledge, skills of discovery and interaction, skills of interpreting and relating, attitudes, and critical cultural awareness.

Byram et al. (2001) argues that this set of knowledge, skills, and attitudes is complemented by an individual’s set of values developed from belonging to certain social groups and as part of the society to which one belongs. According to Salih and Omar (2021), “intercultural competence comprises four domains: cognitive (knowledge-based), metacognitive (the ability to acquire and process cultural content), motivational (to show interest in effective communication interculturally), and behavioral (the ability to behave in an interculturally sensitive way)” (p. 184). They applied this theoretical concept in practice in the context of English as a foreign language in higher education. The present study draws from these concepts, but rather than apply them to groups from diverse international cultures, it applies them to diverse intranational cultural groups. Moreover, it applies them to the broader context of higher education, beyond the language classroom, and into the natural setting of the academic environment.

The literature on interactions between culturally differing groups in higher education has yielded diverse theories and mixed findings. Based on the contact hypothesis (Allport, 1954), some studies suggest that exposure to diverse cultures within the higher education setting can contribute to natural intercultural and intracultural interactions, lowering barriers between members of an ingroup with those of an outgroup. The term ‘ingroup’ refers to the social group to which the individuals perceive themselves as belonging. It is the group with which an individual identifies and feels a sense of belonging, loyalty, and solidarity. The term ‘outgroup’ refers to the social group to which the individuals do not perceive themselves as belonging. It is the group perceived as different or distinct from one’s own ingroup (Allport, 1954; Tajfel, 1970; Pettigrew and Tropp, 2006; Schmid et al., 2014; Wölfer and Hewstone, 2018). It is important to note that these terms are not inherently tied to a majority or minority status. Instead, they are relative and depend on the given context of a particular situation.

According to the contact hypothesis, under certain conditions—equal status, a common goal, cooperation for achieving the goal, and institutional support—contact between groups that are in conflict can lower negative perceptions and prejudice against members of the outgroup. Based on this concept, some claim that sharing classrooms and living spaces with individuals from different backgrounds, or engaging in collaborative projects, can foster intergroup understanding and reduce prejudice among students (Hu and Kuh, 2003; Cheng and Zhao, 2006; Bernstein and Salipante, 2017; Hendrickson, 2018; Lin and Shen, 2020). As such, exposure to diversity in academic and social contexts could be perceived as a catalyst for the development of intercultural competence among students. Cultural diversity refers to “the representation, in one social system, of people with distinctly different group affiliations of cultural significance” (Cox, 1993, p. 6). Based on this definition, cultural diversity is not just about the presence of different groups, but also about how these groups interact and coexist within a shared social space (Brox Larsen, 2021).

Pettigrew and Tropp’s (2006) meta-analysis of over 500 studies examining the effect of the contact hypothesis is commonly cited as establishing support for its validity. Among their conclusions, not all four conditions need to be met in order to have a positive influence, and in some cases, the positive outcome can be seen as a result of natural interactions between members of different groups, without the necessity of intentional interventions. This study has been reviewed in a more recent meta-analysis, which raised questions regarding the validity and reliability of the studies that were reviewed in the Pettigrew and Tropp (2006) meta-analysis and thereby raise new questions regarding the claims of positive effects as a result of contact (Paluck et al., 2019). Among the criticisms is that many of the studies examined short-term structured interventions with the intention of creating contrived situations. Moreover, the effects, which were often positive, were mainly assessed immediately following the intervention, rendering long-term effects unknown. The more recent meta-analysis, which aimed to address these limitations, confirmed the positive effects of the contact hypothesis, though qualified the extent of the influence.

Other attempts have been made to examine longer-term effects in HEIs, where students study together for a number of years. Hu and Kuh (2003), for example, examined the effects of interactional diversity experiences on domestic students. In their study, the College Student Experience Questionnaire was completed by 53,756 undergraduate students from 124 universities in the United States. Their findings indicated that experiences with interactional diversity had a consistently positive impact on various college-outcome variables including general education, personal development, science and technology, vocational preparation, and intellectual development (total gains, and diversity competence measures). Other studies have found that informal social settings within the natural campus environment (i.e., outside the classroom) provide opportunities for positive and meaningful intercultural interactions (Hu and Kuh, 2003; Cheng and Zhao, 2006; Bernstein and Salipante, 2017; Hendrickson, 2018; Lin and Shen, 2020). Others, however, found that in the natural campus environment students from diverse cultures do not necessarily engage with one another and generally choose to remain with their own ingroup (Volet and Ang, 2012; Nesdale and Todd, 2000; Dunne, 2009; Harrison and Peacock, 2010; Hou and McDowell, 2014; Lehto et al., 2014; Auschner, 2020).

In general, much of the literature on intercultural competence focuses on interactions between cross-border cultures, between domestic and international or immigrant students. However, in countries with culturally diverse communities, developing intercultural competence in higher education is crucial for enhancing relations between populations that are ethnically, socially, and/or linguistically segregated, and that are often in conflict. Interaction between students of diverse cultures who do not typically engage with one another within the same national context has been less explored. The present study has significance in narrowing the gap in knowledge on intercultural competence in the context of intranational intergroup contact.

In regions where diverse groups that are in conflict interact, the challenge to promote intercultural understanding is exacerbated. Moreover, encounters which participants feel have been imposed on them, in which they feel threatened, or of a conflictual nature can heighten prejudice and increase the distance between the groups (Al Ramiah and Hewstone, 2013; Lin and Shen, 2020). One promising tool for improving intergroup relations in such contexts is sport (Sugden and Tomlinson, 2017). In particular, sport has been shown to positively impact Jewish-Arab relations in Israel (Leitner et al., 2012; Galily et al., 2013; Leitner, 2014), though much of the research has focused on youth. Less attention has been given to its effects on young adults. A physical education teacher education (PETE) institution that trains young adults to become educators may provide an ideal setting for fostering intercultural communication among students from conflicting groups.

The current study aims to contribute to the knowledge on intercultural communicative competence in higher education by focusing on the effect of intergroup contact between Arab and Jewish students in Israel within the natural college-campus environment.

1.2 The Israeli context

The population of Israel comprises a remarkably diverse population, made up of 9.2 million people. Within this demographic tapestry, 74% identify as Jewish, 22% as Arab, and 5% as other. Among the Arab community in Israel, 84% are Muslim, 9% are Christian, and 7% are Druze (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2023). The Jewish population is further diversified by secular (43.9%), traditional (32.9%) religious (11.5%) and Ultra-Orthodox (10.9%) sectors (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2023).

The broad spectrum of cultures within the Israeli population provides fertile ground for intercultural exchanges and the development of intercultural competence. However, this potential is impeded by the somewhat segregated nature of the communities and the educational system in the country (Smooha, 2010), with most communities being either predominantly Jewish or Arab. Within the Jewish population, divisions can be seen between secular, religious, and ultra-Orthodox neighborhoods; in the Arab population, distinctions can be seen between Muslim, Christian, Druze, and Bedouin communities. Moreover, educational institutions and other services predominantly cater to the specific needs of each community, limiting interactions between children and adults of different backgrounds. Language and political barriers further decrease the possibility of conducting meaningful and positive interactions between the Jewish and Arab populations.

At the backdrop of this reality, the course of life in Israel calls for encounters between individuals of the Arab and Jewish communities. The majority of encounters that do take place between these populations are unplanned, incidental and of a fleeting nature, simply transpiring as a result of Arabs and Jews living side by side and interacting with one another in various aspects of life. Some of these natural encounters take place within shared frameworks, such as hospitals, academic institutions, professional associations, or political movements (Lavie et al., 2021). Studies show that despite basic challenges that characterize relationships between members of majority and minority groups, intergroup encounters within a common framework increases the probability of more engaging and meaningful relations and the continuity of the relationship over time (West and Dovidio, 2012).

An important arena where enabling positive encounters between young adult Arab and Jewish communities can occur is higher education, where members of both communities often meet in a meaningful exchange for the first time. The assumption has been that informal encounters within natural conditions that take place between Arab and Jewish undergraduate students have a formative effect on their attitudes and perceptions of members of the other group (Lev Ari and Mula, 2017; Lev Ari and Husisi-Sabek, 2020). Yet, despite the potential of a shared HEI campus, meaningful engagements between Arab and Jewish students remain limited.

A comprehensive study involving 4,697 Arab and Jewish students across 12 HEIs revealed that while the academic environment has the potential to foster improved relations, mere coexistence within the same physical space does not necessarily lead to positive social change (Aslih et al., 2020). These findings echo previous observations of the ‘missed opportunity’ of college campuses in enhancing mutual attitudes among students from Arab and Jewish communities (Abbas et al., 2018; Sky and Arnon, 2017). Similar to literature findings on cross-border intercultural encounters, intranational group separatism can be reinforced in the ‘natural’ campus environment.

In contrast to the above findings, Gross and Maor (2020) compared between the attitudes and interpersonal relations of Arab and Jewish students in two HEIs. The first institution had low student diversity, with only 1.9% of all students being from the Arab community; the second HEI exhibited greater diversity, with Arab students accounting for 20% of the entire student body. Unlike the findings presented above, the data that were gathered by these researchers was found to support the contact hypothesis, with more positive attitudes toward students from the other group being seen in students from the institution with greater diversity:

Our findings offer empirical evidence that contact theory is indeed valid in situations of intractable conflict, as was indicated by Arab and Jewish students’ generally more positive reciprocal attitudes and interpersonal relations at a university where the percentage of Arab students is relatively large compared with at a university without such other group exposure (p.5).

The authors also found that the effect of studying in a shared setting on reducing stereotypes and prejudice was greater on the Jewish majority population than on the Arab minority group of students. It is unclear, however, whether the students who chose to study in an institution with greater diversity had more positive attitudes toward their counterparts from the other group prior to embarking on their studies or whether these developed over time, following on-campus intergroup interactions.

Nevertheless, as cross-sectional studies tend to examine students’ attitudes at a certain period of time, these may fluctuate in line with the given social and political climate. In Israel, students belong to groups that are subjected to national and ethnic rivalry and to ongoing tensions (Bar-Tal, 2007). External conditions, including threatening or violent events that occur periodically within the Jewish-Arab and Jewish-Palestinian context, heighten these feelings and deepen the sense of conflict, exacerbating negative attitudes, and decreasing the positive effects of contact (Hertz-Lazarowitz et al., 1998; Bar-Tal and Labin, 2001; Salomon, 2004, 2006, 2011; Bar-Tal et al., 2008; Hertz-Lazarowitz et al., 2010). This dynamic has also been seen in other countries with groups in conflict, such as Ireland (Kilpatrick and Leitch, 2004) and Turkey (Bagci et al., 2023).

The current study aims to examine and compare the effect of contact in the natural environment of a four-year teacher training HEI in Israel at two different timepoints in order to explore the consistency of the effect on students’ willingness for and actual intranational intergroup interactions. The first period of 2016 follows a year of increased violence often referred to as the “intifada of individuals” (Beaumont, 2016). The second examination timepoint is 2023, 18 months after the May 2021 uprisings, when Arab-Israeli riots erupted leading to violent clashes between Arab and Jewish populations in Israel (Fabian, 2022). In June 2021, an Arab party joined the government coalition for the first time in Israeli history, signifying the desire of the Arab public to become an integral part of the majority in Israel and to integrate in the political decision-making and civic policy-making processes (Lavie et al., 2021). This coalition, however, was short lived, lasting a little over a year and culminating with an increase in violence in 2022 (Fabian, 2022). (It should be noted that the second data collection took place prior to the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas War on October 7, 2023.)

To address the aims of this study, the following five research questions were delineated:

1. What was the extent of willingness for intergroup closeness and actual intergroup interactions among Arab and Jewish students within the natural HEI setting in 2016 and 2023?

2. How do willingness for intergroup closeness and actual intergroup interactions compare between the majority Jewish students and minority Arab students across both time periods?

3. What are the relationships between the dimensions of willingness for intergroup closeness and actual intergroup interactions, and how do these relationships evolve over time in the natural HEI setting?

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design

This study employed a quantitative methodology, utilizing a repeated cross-sectional survey design for conducting longitudinal analysis. The questionnaire, primarily consisting of closed-answer questions, addressed interactions between Arab and Jewish undergraduate Physical Education Teacher Education (PETE) students and their attitudes and perceptions toward one another. To ascertain changes over time, data were collected and compared at two distinct time periods, seven years apart.

Background characteristics, encompassing factors such as place of residence, admission conditions, and socioeconomic status at both timepoints, remained consistent.

2.2 Participants

The study included 733 PETE students (353 female) from a teacher education college in Israel. The participants were aged 18–35 years (M = 24.77; SD = 2.89), from all 4 years of the bachelor’s program. In 2016, data were collected from 419 participants (74 Arabs); in 2023, data were collected from 314 participants (70 Arabs). The ratio between Arab and Jewish participants (19.6 and 80.4%, respectively) is similar to that of the general population in Israel (21 and 74%, respectively) (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2023). Procedure.

After obtaining ethical approval from the authors’ affiliated Institutional Review Board (Approval No. 398/23, February 2016), a paper-and-pen version of the questionnaire was distributed to the participants. An explanation of the study objectives was provided orally, and a written introduction to the study and its objectives were presented at the beginning of the questionnaire. Anonymity was assured for all participants, and completion of the survey served as informed consent for their participation in the study (Landau and Scheffler, 2007). Students were recruited via the college’s social media platforms (Facebook pages and WhatsApp groups) and were allotted time during on-campus lessons to complete the questionnaires. As the studies at the HEI are conducted in Hebrew, and the entry requirements for all students to be accepted at the college are a proficient level of Hebrew based on national psychometric scores, both Arab and Jewish students filled out the questionnaire in Hebrew.

The study was conducted via a comprehensive large-scale questionnaire that consisted of two main sections: (1) demographic background information (28 items); and (2) attitudes of Arab and Jewish students toward one another (36 items) (Boymel et al., 2009; Jayusi, 2009; Swart et al., 2010).

The current analysis concentrates on two specific dimensions extracted from the questionnaire. The willingness for intergroup closeness dimension was examined through four scales, willingness for academic relations, willingness for friendship relations, willingness for acquaintanceship relations, and a general index (a total average of the first three scales). For this dimension, the participants were asked to rate their level of agreement with each item on a scale of a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (to a very great extent). For the actual intergroup interactions dimension, the participants were asked to rate their level of agreement with 11 items that describe interactions with students from the outgroup, on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (to a very great extent).

2.3 Data analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS v.27 for Windows. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated to assess internal consistency of each scale. Mean values are presented with standard deviations in parentheses. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) are reported for comparisons between Arab and Jewish students at each time period and for the willingness for closeness index.

In addition, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to examine the effects of nationality and study year on four closeness aspects, including academic relations, friendship relations, acquaintanceship relations, and the general closeness index. To assess whether differences exist between the various willingness for closeness indices in relation to group and year, repeated measures ANOVA were conducted, with two independent variables (year and group) and three dependent variables (academic relations, friendship relations, and acquaintanceship relations). Finally, Bonferroni corrections for multiple measurements were applied; for the independent samples, two-tailed t-tests were used to compare between the two groups.

3 Results

Results of the data analysis are presented first regarding willingness for intergroup closeness, followed by those regarding actual intergroup interactions.

3.1 Willingness for intergroup closeness

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated to assess the internal consistency of the three willingness for intergroup closeness scales. For willingness to develop academic relations, items such as “studying together for exams” and “writing a paper together” were assessed (α = 0.887). For willingness to form friendships, items such as “going out together to a social activity,” “hosting them at my house,” and “accepting them as good friends” were assessed (α = 0.893). Finally, for willingness to form acquaintances, items such as “being friends on social media,” “playing together on a sports team,” and “working together in the same workplace” were assessed (α = 0.785).

Based on these categories, three indices were constructed for the ANOVA. Additionally, a general closeness index was designed, derived from all statements in all three categories (α = 0.929). Higher values in these indices indicate a stronger desire for closeness with students from the outgroup.

As shown in Table 1, Arab students reported a significantly greater willingness for intergroup closeness compared to their Jewish peers across both time periods. This was evident in friendship [t(417) = 3.666, p < 0.001, d = 0.47; t(312) = 5.422, p < 0.001, d = 0.74] and acquaintanceship relations [t(417) = 2.095, p = 0.04, d = 0.27; t(312) = 5.902, p < 0.001, d = 0.80], as well as in the general index [t(417) = 3.239, p < 0.001, d = 0.42; t(312) = 5.971, p < 0.001, d = 0.81]. In terms of academic relations, a non-statistical difference in 2016 [t(417) = 1.537, p = 0.12, d = 0.20] and a statistically significant difference in 2023 [t(417) = 5.088, p < 0.001, d = 0.69] can be discerned between the two groups, with the higher scores among Arab students.

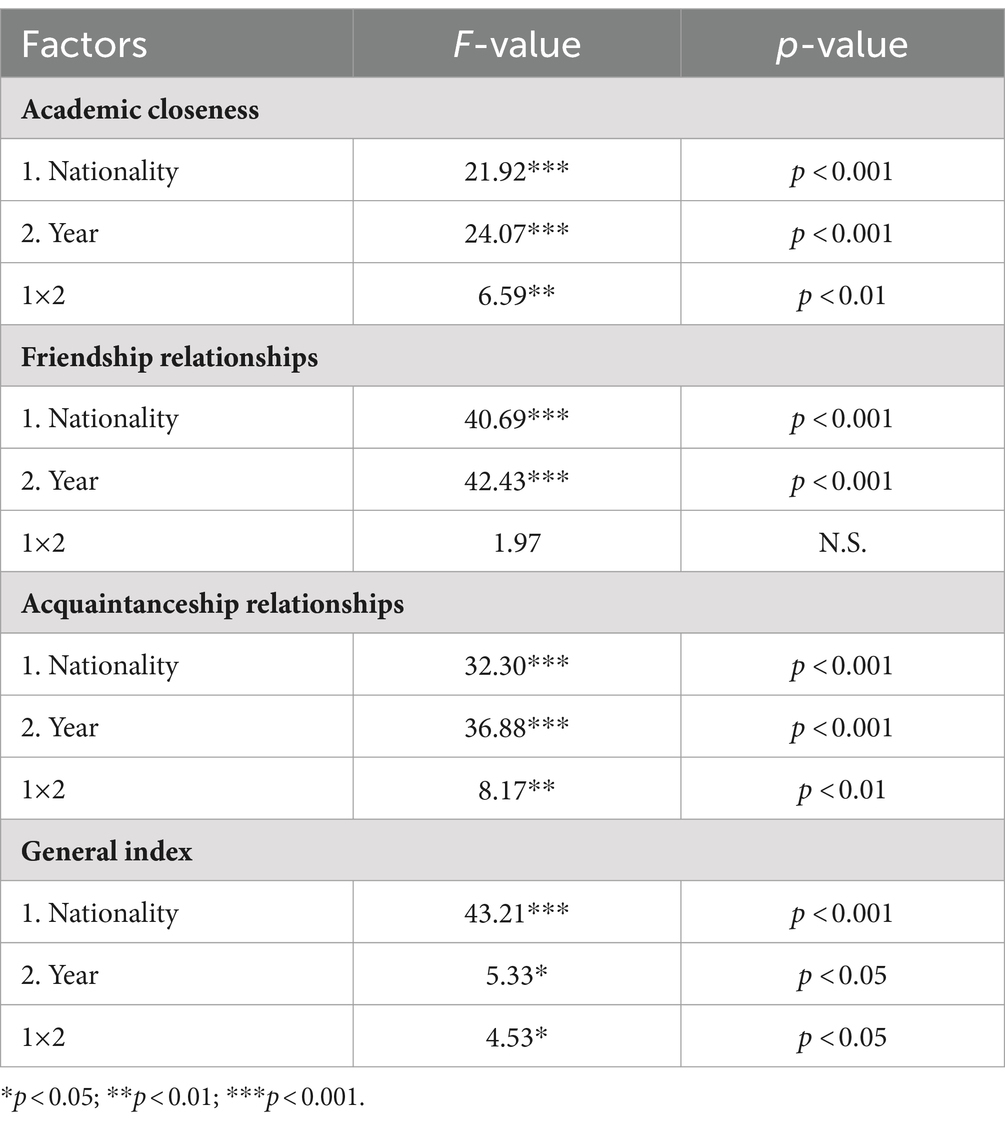

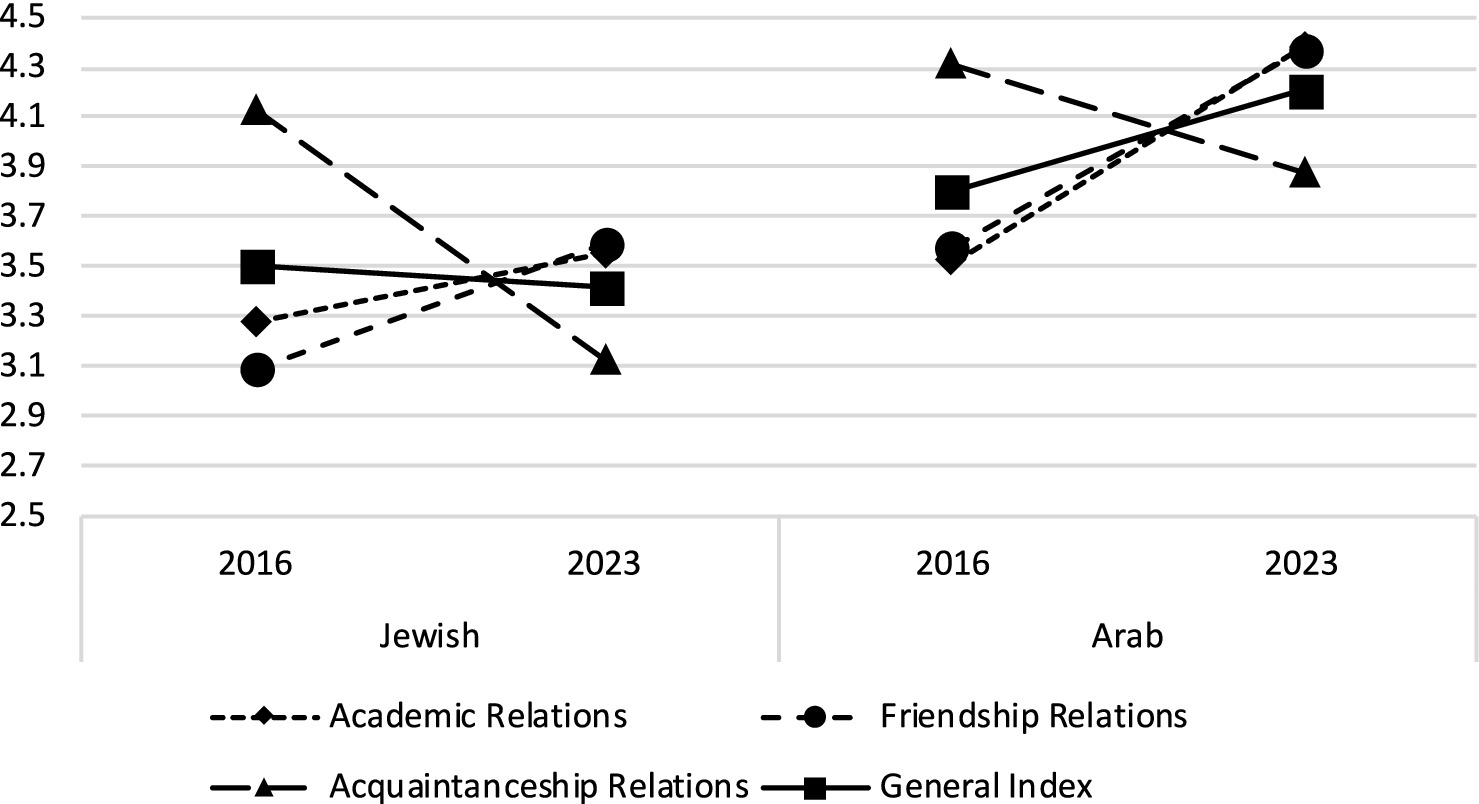

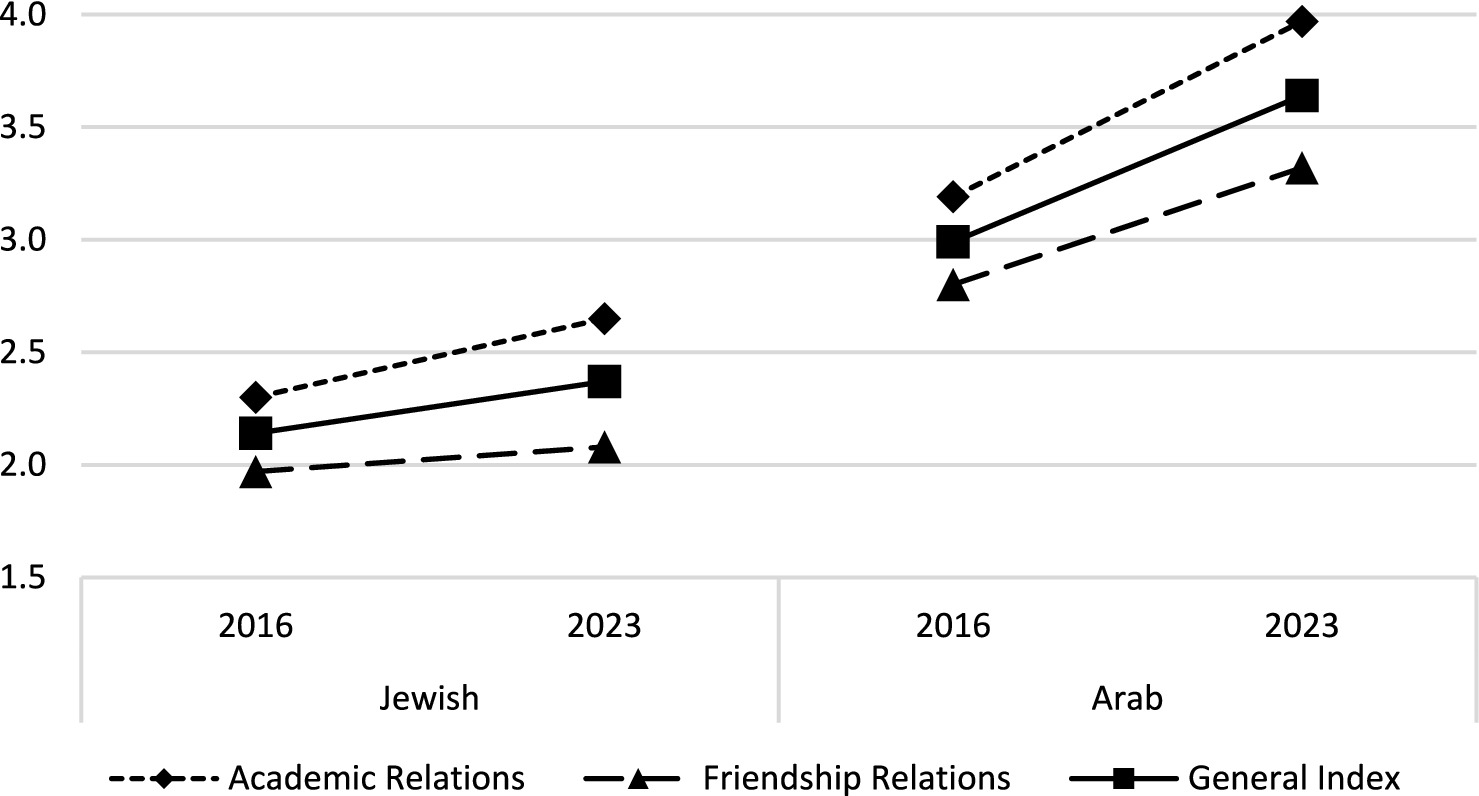

To assess whether differences exist between the four indices of willingness for intergroup closeness in relation to group and year, repeated measures ANOVA were conducted. As can be seen in Table 2 and Figure 1 a significant effect [F(2,716) = 32.85, p < 0.001] was found. However, an interaction was only seen for year [F(2,716) = 131.50, p < 0.001], not for group or for group X year.

Post-hoc analysis was performed using t-tests in order to explore each group separately. When examining the willingness for closeness among Arab students toward their Jewish peers, a significant increase was seen in willingness for academic relations [t(142) = 5.466, p < 0.001, d = 0.91], friendship relations [t(142) = 5.256, p < 0.001, d = 0.88], and the general index [t(142) = 3.166, p < 0.001, d = 0.53] from 2016 to 2023. However, a decrease was seen in willingness for acquaintance relations [t(142) = 2.449, p = 0.02, d = 0.41]. Still, in 2023, all indices among the Arab participants were relatively high, standing above 4.

When examining willingness for closeness among Jewish students toward their Arab peers, a significant increase was also seen in willingness for academic relations [t(587) = 2.544, p = 0.01, d = 0.21] and friendship relations [t(587) = 5.515, p < 0.001, d = 0.46], yet these increases were smaller than those seen in the Arab participants. Regarding willingness for acquaintanceship relations [t(587) = 9.722, p < 0.001, d = 0.81], a significant decrease was seen, yet to a greater degree than that of their Arab peers. In terms of the general index, the score remains constant between the two time periods [t(587) = 0.123, p = 0.90, d = 0.01]. In general, the scores for willingness for intergroup closeness were in the 3–3.5 mid-range.

Interestingly, the score for willingness for acquaintanceship relations is the highest of all other parameters for both groups in 2016, yet the lowest of all parameters for both groups in 2023.

3.2 Actual intergroup interactions

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated to assess the internal consistency of the actual intergroup closeness scales. To identify factors, Varimax-type factor analysis was performed, resulting in one factor explaining 85% of the variance. The first category, academic interactions, encompassed items such as “sitting together in class,” “studying together for tests,” “working on a team together,” and “working together on assignments” (α = 0.818). The second category, friendship interactions, included the items “preparing meals together,” “spending free time together,” “visiting at each other’s homes,” “sharing personal information,” “calling each other just to chat,” “helping each other with various things,” and “being friends on social media” (α = 0.894). Additionally, a general index of interactions with members of the outgroup was designed, derived from all statements in this category (α = 0.916). Higher values in these indices indicate greater interactions with students from the outgroup.

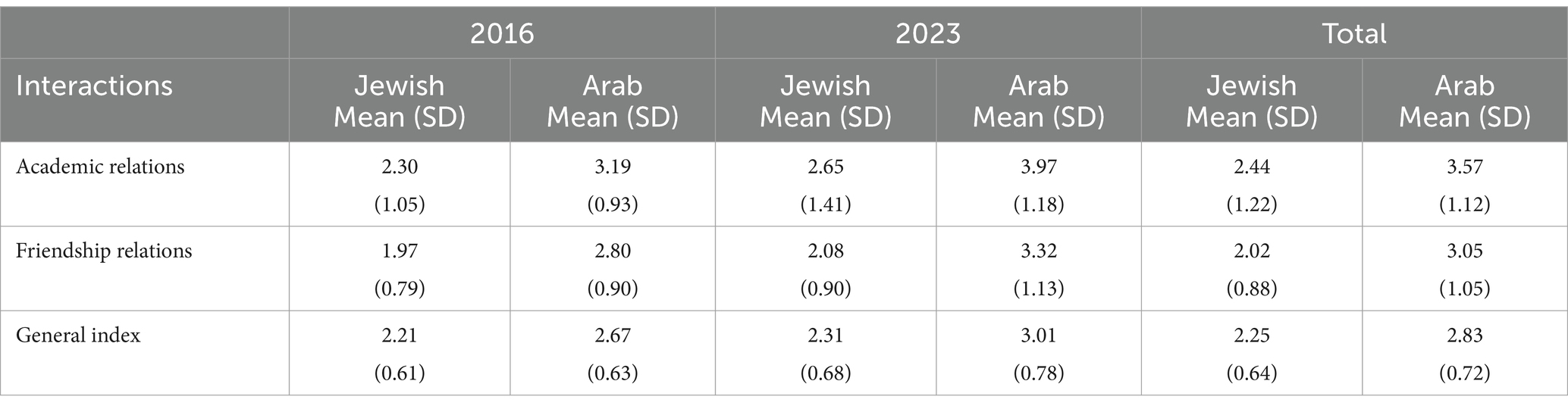

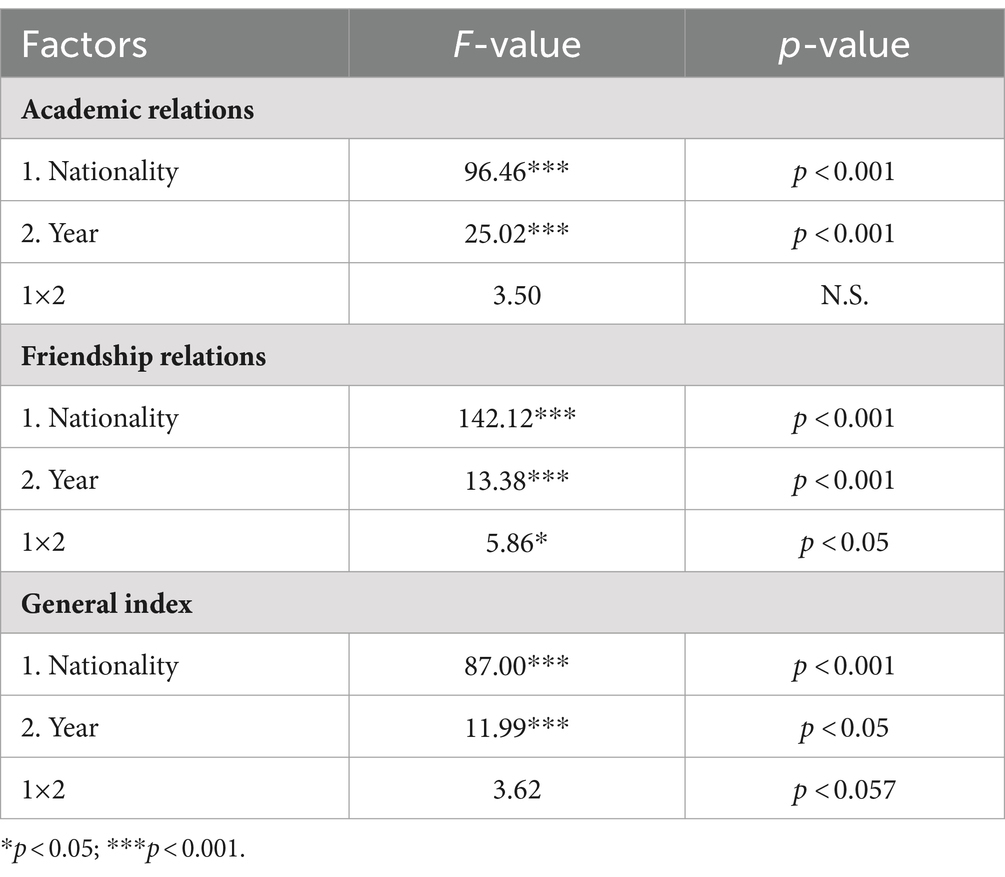

As shown in Tables 3, 4 and illustrated in Figure 2, the results reveal highly statistically significant differences between Arab and Jewish students in both time periods and across all parameters. Arab students reported significantly greater degrees of actual intergroup interactions, including academic relation [t(417) = 6.744, p < 0.001, d = 0.86; t(312) = 7.145, p < 0.001, d = 0.97], friendship relations [t(417) = 7.995, p < 0.001, d = 1.02; t(312) = 9.569, p < 0.001, d = 1.30], and the general interaction index [t(417) = 5.852, p < 0.001, d = 0.75; t(312) = 7.340, p < 0.001, d = 1.00], compared to their Jewish peers, and at both timepoints. It is noteworthy that no scores were greater than 4 for all parameters and for both groups, with scores among the Jewish participants remaining lower than 3 (Table 3 and Figure 2).

Post-hoc analysis was performed using t-tests in order to explore each group separately. When examining reports of actual intergroup interactions among Arab students with their Jewish peers, statistically significant increases were seen in academic relations [t(142) = 4.418, p < 0.001, d = 0.74], friendship relations [t(142) = 3.062, p < 0.001, d = 0.51], and the general index [t(142) = 2.884, p < 0.001, d = 0.48]. The highest scores were seen in academic relations, in both timepoints, reaching almost 4 in 2023 (Table 4).

When examining actual intergroup interactions among Jewish students, a significant increase was also seen in academic relations [t(587) = 3.452, p < 0.001, d = 0.29], which scored highest in comparison to the other parameters, and in both time periods. A non-statistically significant increase was seen in friendship relations [t(587) = 1.570, p = 0.12, d = 0.13] and in the general index [t(587) = 1.868, p = 0.06, d = 0.16]. However, overall, the data indicate relatively low scores for actual intergroup interactions, well below 3 in all parameters.

Table 4 illustrates the results of the analysis of interactions with the outgroup, with nationality and year as independent variables and each interaction aspect as dependent variables. The F-values represent the significance of the main effects and interaction effects, with “**” indicating highly significant results and denoting significance at the 0.05 level.

4 Discussion

The current study explored the potential for developing intercultural competence through intranational intergroup contact between Arab and Jewish students within the natural environment of the college campus. The research questions were addressed by assessing parameters of willingness for intergroup closeness and actual intergroup interactions between Arab and Jewish undergraduate PETE students. Based on the contact hypothesis, which has demonstrated positive effects in reducing prejudice and improving intergroup attitudes (Tropp and Pettigrew, 2005; Pettigrew and Tropp, 2006; Al Ramiah and Hewstone, 2013; Paluck et al., 2019), the study aimed to examine the effect of such ongoing contact on relations between students from populations that are subjected to ongoing conflict and tension (Bar-Tal, 2007). Moreover, to examine the consistency of these parameters, or possible changes over time due to external factors, they were examined at two distinct time periods (2016 and 2023), that were characterized by violent events and heightened tension between Arab and Jewish populations in Israel (Lavie et al., 2021; Fabian, 2022).

4.1 The gap between willingness for intergroup closeness and actual intergroup interactions within the natural HEI environment

Research on the impact of natural HEI environments on intergroup and intercultural interactions reveals mixed results. Some studies highlight limited engagement and a tendency toward segregation, with students often forming monocultural groups both in and out of the classroom (Auschner, 2020; Harrison and Peacock, 2010; Dunne, 2009). This segregation extends beyond the academic environment, with domestic and international students frequently maintaining separate social groups (Nesdale and Todd, 2000; Volet and Ang, 2012). Over time, students’ willingness to engage in intercultural encounters may decline, resulting in more negative attitudes (Lehto et al., 2014).

Conversely, other research suggests that informal social settings within HEIs, such as extracurricular activities and shared living spaces, can foster positive intercultural interactions and enhance cultural intelligence (Cheng and Zhao, 2006; Hendrickson, 2018; Lin and Shen, 2020).

The current study supports this mixed picture, finding that while students express a strong desire for intergroup closeness, actual interactions remain limited. This gap suggests that while the campus environment has the potential to encourage positive intergroup relations, its full potential often goes unrealized, contributing to the inconsistent findings in the literature.

Literature on contact between intranational groups in conflict highlights significant challenges. In multicultural societies, such contact often leads to discomfort and suppressed emotions, potentially exacerbating tensions (Al Ramiah and Hewstone, 2013; Lin and Shen, 2020). Despite these challenges, contact has been shown to increase willingness for reconciliation and enhance trust, forgiveness, and empathy, particularly in conflict zones like Northern Ireland, Rwanda, Sri Lanka, and Israel (Al Ramiah and Hewstone, 2013). In particular, sport which offers opportunities for contact, has been found to be an effective tool in conflict mitigation and increased willingness for reconciliation.

In the current study, the limited interactions between Arab and Jewish students may reflect similar challenges, possibly stemming from discomfort or intercultural anxiety, as identified in previous research.

Nevertheless, the significantly higher willingness for intergroup closeness seen in the current study may indicate a positive effect of shared on-campus social settings, instilling in the students a desire to establish more meaningful relations with one another. Partially in support of the literature, the findings of this study suggest that the natural on-campus setting shared by both groups instils in Arab and Jewish students a willingness for intergroup closeness and a desire for more significant relations, yet without more structured interventions, the potential for actual meaningful intergroup interactions remains limited. These findings support the conclusions reached by Aslih et al. (2020), who surveyed over 4,000 students in 12 HEIs in Israel. The researchers found that the academic space holds the potential for increasing willingness for closeness and fostering positive interactions between Arab and Jewish students, but this potential requires institutional agency. These implications resonate with the literature on cross-border and intergroup contact in HEIs, which has also concluded that institutional commitment is needed for fostering intergroup relations among students by creating a campus environment that facilitates intercultural cohesion (Pettigrew and Tropp, 2006; Groeppel-Klein et al., 2010; Kudo et al., 2017; Paluck et al., 2019; Jokikokko, 2021; Makarova, 2021).

4.2 Increased willingness for intergroup closeness and actual intergroup interactions

When comparing between the two examined time periods, the findings are encouraging, as significant increases were seen among participants from both Arab and Jewish students in their willingness for academic and friendship intergroup relations from 2016 to 2023. In terms of actual intergroup interactions, significant increases were found in academic and social relations among Arab students; in their Jewish peers, a significant increase was found in academic relations and a non-significant increase was seen in friendship relations from 2016 to 2023.

Among all the dimensions investigated, the only dimension that showed a decline was willingness for acquaintanceship relations, which showed the highest scores in 2016 among both groups, yet interestingly becomes the parameter with the lowest scores in 2023 among both groups. This change is unclear, but may indicate a shift toward deeper academic and friendship relations, rather than a focus on superficial acquaintance-level connections. As argued in the literature, feelings and attitudes between groups, especially those that are in conflict, are impacted by external conditions and can change accordingly (Hertz-Lazarowitz et al., 1998; Bar-Tal and Labin, 2001; Kilpatrick and Leitch, 2004; Salomon, 2004, 2006, 2011; Bar-Tal et al., 2008; Hertz-Lazarowitz et al., 2010; De Dreu et al., 2022). Both time periods that were examined in the current study were wrought with instability and violence. Some even argue that Israeli society underwent growing disintegration and segregation, with a greater split becoming visible between different political groups (Hitman, 2021). At the same time, several changes transpired, indicative of growing integration. For example, in the political arena, although short lived, an Arab party, with the declared aims of enhancing the everyday life of Arab citizens in Israel through a focus on their integration in mainstream Israeli society, became part of a coalition government for the first time in Israel’s history (Lavie et al., 2021). Moreover, in the cultural arena, a growing number of Arab citizens have become celebrated media heroes in mainstream culture, including music, sports, film, art, and news coverage, inter alia (Smooha, 2010) and an increasing number of Jewish Israelis are showing interest in and engaging with Arab culture (Erez and Karkabi, 2019).

In terms of education, the percentage of Arab students in HEIs in Israel from the 2015–2016 academic year to the 2020–2021 academic year increased. For undergraduate studies, numbers increased from 15.2 to 19.3%, and in master’s and PhD degrees, numbers increased from 11.4 to 15.9% and from 5.7 to 8%, respectively (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2021). In 2016, The Israeli Hope in Academia Organization was established by former Israeli President Reuven Rivlin, with the aim of fostering and promoting partnerships between different sectors of Israeli society (Edmond de Rothschild Foundation, n.d.). In addition, the Ministry of Education established the Headquarters for Civic Education and Life in Partnership, with a three-year (2016–2019) plan, aimed at decreasing prejudice and fostering positive relations between the various sectors of Israeli society (Headquarters for Civic Education and Coexistence, Ministry of Education, 2016). A circular letter issued by the Ministry of Education for the 2021–2022 academic year for all educational institutions in Israel, presented guidelines for reducing prejudice and promoting life in partnership (Circular Letter, Ministry of Education, 2021). Another possible factor that may have heightened the desire for integration could be the effect of cooperation that was seen between all sectors following the Covid-19 outbreak; for example, in health care institutions, where personnel from all sectors of Israeli society united efforts to treat patients and save lives throughout the pandemic (El-Batsch, 2020).

These changes in Israeli society may have externally impacted students’ views over the seven-year interim between the two examined periods. Such external conditions, that are unrelated to the HEI setting, could explain the overall increase in willingness for closeness and in actual intergroup interactions seen in 2023 compared to 2016. On the other hand, the violence and distrust between the Arab and Jewish communities following the May Uprisings in 2021 cannot be ignored. Still, the general discourse on integration in Israel, combined with cooperation in all areas of life, may have countered and mitigated the sense of conflict, particularly among students of education (the participants of the current study). As noted earlier, it must be noted that data for this study were collected prior to the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas War, thereby reflecting the perceptions of students prior to these events. The effects of intergroup contact on Arab and Jewish students in HEIs following the war warrants additional investigation to be compared with those in the periods examined in the current paper.

4.3 Effects of contact on students from minority and majority groups

When comparing between the Jewish majority and the Arab minority students at the HEI in this study, results indicated that Arab participants reported a greater willingness for intergroup closeness, as expressed by their higher scores of willingness for academic, friendship and acquaintanceship relations in both time periods. They also reported more frequent actual academic and friendship interactions in both time periods. These findings support former studies that found more positive attitudes among the minority group toward the majority group than vice versa (Bastian et al., 2012; Tsang, 2022). Yet they are in contrast to those found by Tropp and Pettigrew (2005) who found that the relation between contact and prejudice was weaker among minority groups. They are also in contrast to Kanas et al. (2015) who found greater positive effects of interreligious contact on the Muslim majority group than on the Christian minority group in Indonesia.

Differences in findings may be context-based and related to the specific groups in conflict and environmental circumstances. Gross and Maor (2020) who conducted a study in a similar context and circumstances as this paper, found lower levels of prejudice and stereotypes among both Arab and Jewish students at a university in Israel that offers greater intergroup contact compared to a university with lower intergroup contact, in keeping with the current study. Yet their findings diverge from ours, as higher levels of stereotypical beliefs were found among the Arab minority group. On the other hand, our findings are in line with Aslih et al. (2020), who also found higher motivation for intergroup closeness, a higher extent of academic interactions, and a larger number of friends reported by the Arab students compared to their Jewish peers. Finally, the findings of the current study also support those of Lev Ari and Mula (2017) and Lev Ari and Husisi-Sabek (2020) indicating a higher degree of willingness for closeness among the Arab minority compared to their Jewish peers in the majority group. As such, the effect of contact on minority and majority groups requires further investigation, to better understand the relations between the groups.

4.4 Limitations

The findings of this study contribute to the literature on the impact of contact between students from minority and majority groups on their willingness for closeness and their actual interactions with members of the outgroup. However, a number of research limitations should be addressed. First, although one of the research aims was to compare between students from different academic years, an uneven distribution of participants by year prevented such investigation, including comparisons between the two data-collection timepoints. Despite this challenge, the repeated cross-sectional survey design facilitated a longitudinal analysis of changes in the examined parameters over time, thereby providing important new insights. Additionally, the survey method relied on the students’ self-reporting, which entails potential limitations related to social desirability and response bias, particularly among respondents from minority groups and from more collectivistic cultural backgrounds (Johnson and Van De Vijver, 2003; Knoll, 2013). As such, caution is warranted in interpreting intergroup differences. Nevertheless, the observed changes over time and variations within the investigated parameters suggest the construct’s validity.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, our study sheds light on the dynamics of intranational intergroup contact between Arab and Jewish students within the college campus environment. The findings highlight the persistent gap between the students’ expressed willingness for closeness and their actual interactions. This indicates the presence of a genuine desire for meaningful relations that may not fully manifest simply through intergroup contact and engagement. The study also reveals encouraging trends over time, with significant increases in willingness for academic and friendship relations among both Arab and Jewish students from 2016 to 2023. Despite societal turmoil and tensions, these positive shifts suggest a potential for constructive change in intergroup relations. In addition, the decline in reported willingness for acquaintanceship relations, coupled with the rise in more substantial academic and friendship relations, may imply a shift in priorities among students, reflecting a preference for deeper, more meaningful interactions.

Furthermore, as Arab students consistently reported higher willingness for closeness and more frequent actual interactions than their Jewish counterparts, these findings contribute to the ongoing discourse on the impact of contact on minority and majority groups, emphasizing the context-specific nature of intergroup relations and urging further investigation.

The study is in line with existing literature on the potential of natural settings, such as HEIs, for fostering positive intergroup engagement. However, it also highlights the limitations of such encounters in achieving more profound connections without the assistance of structured interventions. Additionally, external conditions, marked by socio-political changes and integration initiatives in Israeli society, appear to influence intergroup dynamics on campus, offering a glimpse of hope even in the face of broader societal challenges. Yet, as the study was conducted prior to the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas War, the implications of these events on relations between Arab and Jewish students in HEIs in Israel require continued monitoring and examination.

Based on the findings of this study, HEIs play an important role in presenting students with opportunities for actual interactions, cultivating meaningful intergroup relations between Arab and Jewish students in Israel.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Levinsky-Wingate Academic College Review Board (Approval No. 398/23, February 2016). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BS: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SB: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. MA: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors disclose receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the President’s Fund of the Levinsky-Wingate Academic College.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbas, F., Greenberg-Raanan, M., and Maayan, Y. (2018). Sense of belonging to the academic institution among Arab students survey. Inter-Agency Task Force. Available at: https://www.iataskforce.org/resources/view/1660 (Accessed March 5, 2023).

Al Ramiah, A., and Hewstone, M. (2013). Intergroup contact as a tool for reducing, resolving, and preventing intergroup conflict: evidence, limitations, and potential. Am. Psychol. 68, 527–542. doi: 10.1037/a0032603

Allen, T. J. (2022). Assessing intercultural competence using situational judgement tests: reports from an EMI course in Japan. Open J. Soc. Sci. 10, 405–427. doi: 10.4236/jss.2022.1013029

Aslih, S., Eldar, L., Hasson, Y., and Halperin, A. (2020). Maximizing the potential of the Jewish-Arab encounter in academia. aChord Center, Abraham Initiatives Research Report.

Auschner, E. (2020). “Fostering intercultural competence in higher education: designing intercultural group work for the classroom” in Examining social change and social responsibility in higher education. ed. S. L. Niblett Johnson (Hershey, PA: IGI Global), 116–226.

Bagci, S. C., Baysu, G., Tercan, M., and Turnuklu, A. (2023). Dealing with increasing negativity toward refugees: a latent growth curve study of positive and negative intergroup contact and approach-avoidance tendencies. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 49, 1466–1478. doi: 10.1177/01461672221110325

Bar-Tal, D. (2007). Living with the conflict: A social psychological analysis of Jewish society in Israel: A snapshot. Jerusalem: Carmel.

Bar-Tal, D., Halperin, E., Sharvit, K., Rosler, N., and Raviv, E. (2008). Ongoing occupation: social-psychological aspects of an occupying society. Israeli Sociol. 9, 386–357.

Bar-Tal, D., and Labin, D. (2001). The effect of a major event on stereotyping: terrorist attacks in Israel and Israeli adolescents' perceptions of Palestinians, Jordanians and Arabs. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 31, 1–17.

Bastian, B., Lusher, D., and Ata, A. (2012). Contact, evaluation and social distance: differentiating majority and minority effects. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 36, 100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.02.005

Beaumont, P. (2016). Israel-Palestine: outlook bleak as wave of violence passes six-month mark. The Guardian, March 31, 2016.

Bernstein, R. S., and Salipante, P. (2017). Intercultural comfort through social practices: exploring conditions for cultural learning. Front. Educ. 2:31. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2017.00031

Boymel, Y., Zaevi, I., and Tutari, M. (2009). What do Jewish and Arab students learn from each other? Tivon: Oranim College.

Brox Larsen, A. (2021). Perceptions of Cultural Diversity among Pre-service Teachers. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 67, 212–224. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2021.2006300

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Cleveldon: Multicultural Matters.

Byram, M., Nichols, A., and Stevens, D. (2001). Developing intercultural competence in practice. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, Ltd.

Central Bureau of Statistics (2021). Selected data for the opening of the academic year. Available at: https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/mediarelease/doclib/2021/338/06_21_338t3.pdf (Accessed January 28, 2024).

Central Bureau of Statistics (2023). Population statistics. Available at: https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/publications/doclib/2023/2.shnatonpopulation/st02_01.pdf (Accessed August 17, 2024).

Cheng, D. X., and Zhao, C. (2006). Cultivating multicultural competence through active participation: extracurricular activities and multicultural learning. NASPA J. 43, 13–38. doi: 10.2202/1949-6605.1721

Circular Letter, Ministry of Education. (2021). Available at: https://apps.education.gov.il/mankal/Horaa.aspx?siduri=473 (Accessed January 28, 2024).

Cox, T. (1993). Cultural diversity in organizations: theory, research and practice. San Francisco: BerrettKoehler.

De Dreu, C. K. W., Gross, J., and Reddmann, L. (2022). Environmental stress increases out-group aggression and intergroup conflict in humans. Phil. Trans. Royal Soci. B 377:20210147. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2021.0147

Deardorff, D. K. (2004). The identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of international education at institutions of higher education in the United States. Unpublished Dissertation. Raleigh, NC: North Carolina State University.

Deardorff, D. K., and Arasaratnam, L. A. (2017). Intercultural competence in higher education: International approaches, assessment and application. London: Routledge.

Dunne, C. (2009). Host students’ perspectives of intercultural contact in an Irish university. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 13, 222–239. doi: 10.1177/1028315308329787

Edmond de Rothschild Foundation. (n.d.). Available at: https://www.edrf.org.il/en/programs/israeli-hope-in-academia/ (Accessed January 28, 2024).

El-Batsch, M. (2020). Arab and Jewish medics together on frontline of Israel’s virus fight. The Times of Israel, March 31, 2020. Available at: https://www.timesofisrael.com/arab-and-jewish-medics-together-on-frontline-of-israels-virus-fight/ (Accessed January 28, 2024).

Erez, O., and Karkabi, N. (2019). Sounding Arabic: Postvernacular modes of performing the Arabic language in popular music by Israeli Jews. Popular Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fabian, E. (2022). 2022 among the deadliest years in recent memory for Israelis and Palestinians. The Times of Israel, December 13, 2022. Available at: https://www.timesofisrael.com/2022-shaping-up-to-be-deadliest-for-israelis-and-palestinians-in-years/#:~:text=With%20a%20series%20of%20deadly,Israelis%20and%20Palestinians%20in%20years (Accessed January 28, 2024).

Galily, Y., Leitner, M. J., and Shimon, P. (2013). Coexistence and sport, the Israeli Jordanian, and Israeli youth towards one another. J. Comp. Res. Anthropol. Sociol. 4, 181–194.

Groeppel-Klein, A., Germelmann, C. C., and Glaum, M. (2010). Intercultural interaction needs more than mere exposure: searching for drivers of student interaction at border universities. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 34, 253–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.02.003

Gross, Z., and Maor, R. (2020). Is contact theory still valid in acute asymmetrical violent conflict? A case study of Israeli Jewish and Arab students in higher education. Peace Conf. 211–215. doi: 10.1037/pac0000440

Guillén-Yparrea, N., and Ramírez-Montoya, M. S. (2023). Intercultural competencies in higher education: a systematic review from 2016 to 2021. Cogent. Education 10, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2023.2167360

Guo, S., and Jamal, S. (2007). Nurturing cultural diversity in higher education: a critical review of selected models. CSSHE SCÉES 37, 27–49. www.ingentaconnect.com/content/csshe/cjhe

Hakvoort, I., Lindahl, J., and Lundström, A. (2022). Research from 1996 to 2019 on approaches to address conflicts in schools: a bibliometric review of publication activity and research topics. J. Peace Educ. 19, 129–157. doi: 10.1080/17400201.2022.2104234

Harrison, N., and Peacock, P. (2010). Cultural distance, mindfulness and passive xenophobia: using integrated threat theory to explore home higher education students’ perspectives on internationalisation at home. Br. Educ. Res. J. 36, 222–239. doi: 10.1080/01411920903191047

Headquarters for Civic Education and Coexistence, Ministry of Education. (2016). Available at: https://pop.education.gov.il/headquarters-civil-education-coexistence/tolerance-prevention-racism/ (Accessed January 28, 2024).

Heleta, S., and Deardorff, D. K. (2017). “The role of higher education institutions in developing intercultural competence in peace-building in the aftermath of violent conflict” in Intercultural competence in higher education: International approaches, assessment and application. eds. D. K. Deardorff and L. A. Arasaratnam-Smith (London: Routledge), 53–64.

Hendrickson, B. (2018). Intercultural connectors: explaining the influence of extra-curricular activities and tutor programs on international student friendship network development. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 63, 1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2017.11.002

Hertz-Lazarowitz, R., Azaiza, P., Farah, E., Peretz, T., and Zelniker, T. (2010). Perceptions and attitudes of Jewish and Arab students towards the University of Haifa as a binational institution: a comparative survey before and after the second Lebanon war (2006-2007). Stud. Admin. Organiz. Educ. 31, 135–181.

Hertz-Lazarowitz, R., Kupermintz, H., and Lang, J. (1998). “Arab-Jewish student encounters: the Beit-Hagefen co-existence program” in Handbook of interethnic coexistence. ed. E. Weiner (New York: Continuum Publishers), 565–585.

Hitman, G. (2021). More divided than united: Israeli social protest during COVID-19 pandemic of 2020. Cogent. Soc. Sci. 7, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2021.1994203

Hou, J., and McDowell, L. (2014). Learning together? Experiences on a China–U.K. articulation program in engineering. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 18, 224–240. doi: 10.1177/1028315313497591

Hu, S., and Kuh, G. D. (2003). Diversity experiences and college student learning and personal development. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 44, 320–334. doi: 10.1353/csd.2003.0026

Jayusi, V. (2009). Restoring the attitudes of peace education participants through the guidance of peers. Haifa: University of Haifa.

Johnson, T.P., and Van De Vijver, F. (2003). Social desirability in cross-cultural research. 195–204. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235660939 (Accessed November 7, 2023).

Jokikokko, K. (2021). Challenges and possibilities for creating genuinely intercultural higher education learning communities. J. Praxis High. Educ. 26–51. doi: 10.47989/kpdc111

Kanas, A., Scheepers, P., and Sterkens, C. (2015). Interreligious contact, perceived group threat, and perceived discrimination: predicting negative attitudes among religious minorities and majorities in Indonesia. Soc. Psychol. Q. 78, 102–126. doi: 10.1177/0190272514564790

Kilpatrick, R., and Leitch, R. (2004). Teachers' and pupils' educational experiences and school-based responses to the conflict in Northern Ireland. J. Soc. Issues 60, 563–586. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-4537.2004.00372.x

Knoll, B. R. (2013). Assessing the effect of social desirability on nativism attitude responses. Soc. Sci. Res. 42, 1587–1598. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2013.07.012

Krishnan, L. A., and Jin, L. (2022). Long-term impact of study abroad on intercultural development. Perspect 7, 560–573. doi: 10.1044/2021_persp-21-00128

Kudo, K., Volet, S., and Whitsed, C. (2017). Intercultural relationship development at university: a systematic literature review from an ecological and person-in-context perspective. Educ. Res. Rev. 99–116. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2017.01.001

Lavie, E., Elran, M., Shahbari, I., Sawaed, K., and Essa, J. (2021). Jewish-Arab relations in Israel. INSS Insight, 1474.

Lehto, X. Y., Cai, L. A., Fu, X., and Chen, Y. (2014). Intercultural interactions outside the classroom: narratives on a US campus. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 55. doi: 10.1353/csd.2014.0083

Leitner, M.J. (2014). Peacebuilding through sports in post-conflict Israel/Palestine.Sport and development. Available at: www.sportanddev.org

Leitner, M. J., Galily, Y., and Shimon, P. (2012). The effects of Peres Center for Peace sports programs on the attitudes of Arab and Jewish Israeli youth. Leader. Policy Quart. 1, 109–121.

Lev Ari, L., and Husisi-Sabek, R. (2020). Getting to know “them” changed my opinion: intercultural competence among Jewish and Arab graduate students. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 41, 844–857. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2019.1657433

Lev Ari, L., and Mula, W. (2017). ‘Us and them’: towards intercultural competence among Jewish and Arab graduate students at Israeli colleges of education. High. Educ. 74, 979–996. doi: 10.1007/s10734-016-0088-7

Lin, X., and Shen, G. O. P. (2020). How formal and informal intercultural contacts in universities influence students’ cultural intelligence? Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 21, 245–259. doi: 10.1007/s12564-019-09615-y

Makarova, E. (2021). Pursuing goals of sustainable development and internationalization in higher education context. In E3S Web of Conferences 296. EDP Sciences. 837–853.

Nesdale, D., and Todd, P. (2000). Effect of contact on intercultural acceptance: a field study. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 24, 341–360. doi: 10.1016/S0147-1767(00)00005-5

Paluck, E. L., Green, S. A., and Green, D. P. (2019). The contact hypothesis re-evaluated. Behav. Pub. Policy 3, 129–158. doi: 10.1017/bpp.2018.25

Pettigrew, T. F., and Tropp, L. R. (2006). A Meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 90, 751–783. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751

Pike, G. R., and Kuh, G. D. (2006). Relationships among structural diversity, informal peer interactions and perceptions of the campus environment. Rev. High. Educ. 29, 425–450. doi: 10.1353/rhe.2006.0037

Salih, A. A., and Omar, L. I. (2021). Globalized English and users’ intercultural awareness: implications for internationalization of higher education. Citizen. Soci. Econ. Educ. 20, 181–196. doi: 10.1177/20471734211037660

Salomon, G. (2004). Does peace education make a difference? Peace Conflict 10, 257–274. doi: 10.1207/s15327949pac1003_3

Salomon, G. (2006). Does peace education really make a difference? Peace Conflict 12, 37–48. doi: 10.1207/s15327949pac1201_3

Salomon, G. (2011). Four major challenges facing peace education in regions of intractable conflict. Peace Conflict 17, 46–59. doi: 10.1080/10781919.2010.495001

Schmid, K., Hewstone, M., Küpper, B., Zick, A., and Tausch, N. (2014). Reducing aggressive intergroup action tendencies: effects of intergroup contact via perceived intergroup threat. Aggress. Behav. 40, 250–262. doi: 10.1002/ab.21516

Sky, B., and Arnon, M. (2017). Closing the ethnical gap: A case study from the physical education realm. Unpublished research study.

Smooha, S. (2010). Arab-Jewish relations in Israel: alienation and rapprochement. Peaceworks. Available at: www.usip.org (Accessed August 15, 2023).

Sugden, J., and Tomlinson, A. (2017). Sport and peace-building in divided societies: playing with enemies. Routledge.

Swart, H., Hewstone, M., Christ, O., and Voci, A. (2010). The impact of crossgroup friendships in South Africa: affective mediators and multigroup comparisons. J. Soc. Issues 66, 309–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2010.01647.x

Tropp, L. R., and Pettigrew, T. F. (2005). Relationships between intergroup contact and prejudice among minority and majority status groups. Psychol. Sci. 16, 951–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01643.x

Tsang, A. (2022). Comparing and contrasting intra- and inter-cultural relations and perceptions among mainstream and minority students in multicultural classrooms in higher education. Intercult. Educ. 33, 99–113. doi: 10.1080/14675986.2021.2016637

Volet, S. E., and Ang, G. (2012). Culturally mixed groups on international campuses: an opportunity for inter-cultural learning. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 21, 5–23. doi: 10.1080/0729436980170101

West, T. V., and Dovidio, J. F. (2012). “Intergroup contact across time: beyond initial contact” in Advances in intergroup contact. eds. G. Hodson and M. Hewstone (London: Psychology Press), 152–175.

Keywords: intranational relations, intergroup interactions, intercultural competence, higher education, Arab-Jewish relations, contact hypothesis, social dynamics, conflict resolution

Citation: Sindiani M, Hellerstein D, Sky B, Ben Zaken S and Arnon M (2024) Subtle yet encouraging developments: exploring intergroup relations between Arab and Jewish college students over seven years. Front. Educ. 9:1403926. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1403926

Edited by:

Lamis Omar, Dhofar University, OmanReviewed by:

Abdelrahman Salih, Dhofar University, OmanMichael Leitner, California State University, Chico, United States

Copyright © 2024 Sindiani, Hellerstein, Sky, Ben Zaken and Arnon. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mahmood Sindiani, bWFobW9vZHNAbC13LmFjLmls

Mahmood Sindiani

Mahmood Sindiani Devora Hellerstein

Devora Hellerstein Bosmat Sky

Bosmat Sky Michal Arnon

Michal Arnon