- 1School of Business, Eastern Institute of Technology (EIT) – Te Pūkenga, Auckland Campus, Auckland, New Zealand

- 2School of Health Science, Eastern Institute of Technology (EIT) – Te Pūkenga, Auckland Campus, Auckland, New Zealand

1 Introduction

Equal and inclusive education is one of the target areas of SDG-4. This intends to eliminate disparities in educational systems by ensuring equal and equitable access to education for all especially for the vulnerable, including indigenous population (SDG Tracker, 2018). Educational aspirations are essentially reflected in SDG-4 which aims to promise inclusive, equal, and equitable quality education and promote opportunities for lifelong learning for everyone by 2030 (Demirbag, 2021). Educational strategies and approaches rely on academic knowledge from many fields such as facilitation, communication, information technology, psychology, sociology, and digital technology in combination with applied teaching and learning practice and successful implementation (An and Oliver, 2021).

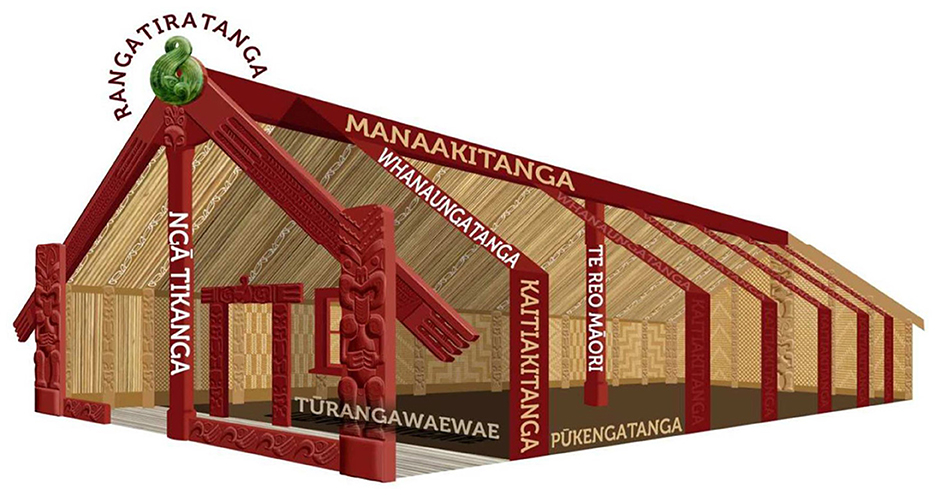

Several strategies have been incorporated to achieve SDG-4 in educational policy and framework to engage Māori learners in all levels of education in Aotearoa New Zealand (Ministry of Education, 2022). Indigenous inclusion has been established as a common approach in Aotearoa New Zealand (Hoskins and Jones, 2022). Te Hono o Te Kahurangi framework was established by NZQA for evaluating programmes, courses, and other components, from a Kaupapa Māori perspective. This emanates from the wider framework of Te Whare Ako (study/learning) that addresses teaching and learning practice. As per NZQA's quality assurance guidelines, institutes of tertiary education shall opt for Te Hono o Te Kahurangi framework if the educational organization uses Kaupapa Māori and/or teaches Mātauranga Māori, to engage learners using Māori approaches and values (NZQA, 2017). Te Whare Ako (the house of learning) establishes a framework that underpins concepts of Ako (teaching and learning) and Kaupapa Māori (Māori principles and values) such as rangatiratanga (chieftainship), manaakitanga (respect and care), whānaungatanga (relationships), pūkengatanga (skills and knowledge) intertwined with contemporary inclusive education approaches (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Te Whare Ako (Māori house of learning) (NZQA, 2017).

The notion of Ako encompasses a dynamic teaching and learning relationship wherein educators do not only impart knowledge, but also actively engage in learning from their students. This approach emphasizes that educators' methods are informed by current research, characterized by purposeful and introspective actions. Ako is founded on

the principle of reciprocity and acknowledges the inseparable connections between the learner, whānau, and their community (Te Kete Ipurangi, 2009). Te Whare Ako framework provides specific directions to utilize Te Reo Māori (Māori language) and Pāngarau Tirewa Mātāmua (numeracy support resources) from Te Tirewa Marautanga (curriculum resources), which is the updated version of Te Marautanga o Aotearoa. These guidelines will provide applied resources to the educational institutions in New Zealand to utilize from the start of the year 2024 (Ministry of Education, 2023).

This article reviews efforts from non-Māori teaching staff in various postgraduate programmes at EIT – Te-Pūkenga to incorporate Te Whare Ako component of Te Hono o Te Kahurangi framework and kaupapa principles into their teaching practice, including challenges, practical examples, and lessons learned.

Following are some of the examples/reflections from non-Māori teaching staff that they practice in their teaching environment:

2 Rangatiratanga (chieftainship)

As per NZQA (2018), rangatiratanga focuses on autonomy, but other approaches to incorporating rangatiratanga into teaching practice include a range of chiefly characteristics, including leadership, and integrity (Te Momo, 2011; Hawkins, 2017).

One of the ways to integrate mātauranga Māori into the teaching is by incorporating the Rauru Whakarare Evaluation Framework (Feekery and Jeffrey, 2019) into the teaching of information literacy. This creates an opportunity for providing a different perspective on evaluation criteria, allowing students the space to reflect on their own personal and cultural attitudes toward concepts like credibility and authority, and to gain a tangata whenua perspective on what might make information more or less credible and authoritative. This also connects with rangatiratanga through the chiefly attribute of integrity, or pono (truthfulness) and tikanga (correctness).

Reflecting on rangatiratanga defined as “autonomy realized through the enactment of a Māori world-view in response to the aspirations and driving motivators of ākonga, whanau, hapu, and where relevant, the Māori community and sector stakeholders” (NZQA, 2018, p. 6) helped to understand more clearly what staff can do to create opportunities for learners to develop their own autonomy, as academics, professionals, and members of the other communities they belong to.

At EIT, the prevailing approach to teaching, which involves active learning in groups, and often wide latitude in the topics that students work on, provides many opportunities for developing rangatiratanga. This approach implicitly recognizes the rangatiratanga of each student, in the form of their mana, knowledge, and experience, by creating an environment where students learn from each other. In addition, we offer a number of opportunities outside of the classroom for students to develop chiefly characteristics. Two examples of which are a public speaking programme modeled on Toastmasters, and a peer mentoring programme (Lopez, 2020). The public speaking programme is voluntary but popular, and gives students opportunities to exercise autonomy in selecting speaking topics, practice leadership roles in organizing and running meetings, and of course develop their ability to speak in public and influence an audience, which itself is an important chiefly attribute (Te Momo, 2011).

3 Manaakitanga (respect/care) and whānaungatanga (relationships)

The foundations of teaching are manaakitanga and whānaungtanga. Mead (2003, p. 120) sees manaakitanga as “hospitality that extends to all social occasions.” Making sure that students feel welcome and that someone cares about them is manaakitanga that also enhances the wellbeing of students. Since, students are away from their families and friends and in a new country: it is a very human way of treating people and most likely a common practice amongst tertiary staff to offer what they see as respectful pastoral care to their students. In this they practice manaakitanga, whether they are conscious of this or not (NZQA, 2017).

Whānaungatanga is another relevant principle for Māori and non-Māori practitioners (NZQA, 2017). A brief interpretation of whānaungatanga is that it “empowers and connects people to each other and the wider community” (Aranga and Ferguson, 2016, p. 4). As a kinship-based society, whānaungatanga is a “fundamental principle” of Māori society and extended “beyond actual whakapapa relationships and included relationships to non-kin persons who became like kin through shared experiences” (Mead, 2003, p. 28). “For example, caring for people means relationships are formed consequently resulting in oneness of spirit, mind and body. In an educational environment, educators/teachers are always connecting with their students and their whānau (family)” (Aranga and Ferguson, 2016, p. 5).

In practice, this includes the use of group work and social activities increase bonds amongst students as well as fostering a feeling of belonging to a group or a class. Beyond group activities designed for learning, teaching and support staff can implement social activities such as holding a shared lunch, having a picnic, practicing waiata (song), or organizing some other fun activities such as sports, art, outings, and coffee and chat sessions. These can be initiated by students too and this also enhances whānaungatanga within the class or across the campus. Where students are on multiple campuses, it is also useful to enhance whānaungatanga through teaching staff to physically visit students at these sites, even though regular teaching for these students may be online.

The following ways were used to model Manaakitanga and Whanaungatanga in classroom:

• Students were asked to present a Pēpeha (self-introduction in Māori) at the beginning of the course and sometimes with a short Whakatauki (proverb or sayings) at the beginning of a workshop. Non-Māori students, respect this as a nice and respectful way to begin the workshop. Māori greetings and even the language of students from other countries is used when taking attendance in order to respect their own cultures too.

• In larger 'whole class' settings Manaakitanga and Whanaungatanga are modeled by encouraging respect and inclusiveness for each other. The right of each student to speak in class about the weekly topics were respected and this shows appreciation and value for each participants' input.

4 Pūkengatanga (skills and knowledge)

Pūkengatanga is the way Māori people learn and transfer skills and Knowledge and “involves the achievement of progressive milestones and skills, enabling individuals to reach their goals and their potential” (Ministry of Health, 2020, p. 27). Pūkengatanga means including explicit learning milestones within the course and learning activities. This supports Māori and other indigenous learners and helps them to keep motivated and see the value and results of what they learn each week. This requires time at the beginning of each topic or unit explaining explicitly why and how participants are learning each skill or piece of knowledge and how it will be useful and valuable in their lives and careers.

5 Te Reo and Tikanga Māori (Māori language and protocols)

Māori principles such as focus on community and relationships, respect for the environment, and valuing the collective over the individual, are embedded in a postgraduate classroom for non-Māori (international) learners through a variety of strategies. Māori perspectives and ways of knowing are built into the curriculum, building relationships with Māori community members and incorporating their knowledge and perspectives, and creating a classroom environment that is inclusive and respectful of diverse cultures which is a prime target area to achieving SDG-4. Additionally, incorporating Māori language and cultural practices, such as karakia (prayers at the start and end of the session) or waiata (Māori songs), also help to incorporate Te Reo and Tikanga Māori in the classroom teaching and learning environment. It is important to be respectful of the Māori culture, seek guidance from Māori teachers and community members, and be open to learning and adapting to new ways of teaching.

The postgraduate health science course is integrated with Mātauranga Māori in various ways, including Māori pedagogical approaches to learning based on Kaupapa Māori. Mātauranga Māori also incorporates Te Reo Māori and Tikanga Māori (Māori language and protocols) and are connected to Hauora Māori based on New Zealand's Māori Health Strategy, “He Korowai Oranga sets the overarching framework that guides the Government and the health and disability sector to achieve the best health outcomes for Māori” (Ministry of Health, 2020). Several components and resources are included that have a strong focus on Te Reo Māori or environment and spaces for learning that are conducive to and nurturing of Mātauranga Māori. Māori customs and values are embedded across all the courses of health science programme. Te Reo Māori and Tikanga Māori are used in relation to Hauora Māori and in health and wellbeing context.

In the learning and teaching environment, sustainability in health and wellbeing is a top priority as required by SDG-3 that ensures healthy lives and promotes wellbeing at all ages (United Nations, 2023). Wai ora (healthy environments), Whānau Ora (healthy families), and Mauri Ora (healthy individuals) are the basic principles valued and practiced in the classroom activities and discussions to understand the New Zealand health framework (Ministry of Health, 2020). Learners are always encouraged to lead their courses of study and assessment tasks by providing them freedom to inform the peers and lead the group work by their previous industry and health qualification and experience. This gives learners the best possible knowledge and information to support them to make informed choices, leading the events, negotiating the rules, determining the outcomes.

The majority of classroom activities and learning is based on Te Pae Māori (healthy future for Māori) foundation of New Zealand Health System and Framework. Many specialized terms and products are used throughout the programme from Te Reo Māori. Māori views on health and wellbeing are incorporated in teaching and learning by a holistic approach that encompasses four key elements - wairua (spiritual), hinengaro (psychological) tinana (physical) and whānau (extended family). Karakia offered at the start and end of the sessions (blessing or prayer) has an essential part in protecting and maintaining these four key elements of health and wellbeing.

Learners get a chance to learn about the Māori health concepts and their importance in overall health and wellbeing, such as Taha Tinana (Physical Health), Taha Wairua (Spiritual Health), Taha Whanau (Family Health) and Taha Hiningaro (Mental Health). The learners also encouraged to participate in an online session to achieve a certificate course on “Foundations in Cultural Competency and Health Literacy” by Mauri Ora Health Education Research (MAURIORA, 2022).

6 Conclusion

Non-Māori teachers' reflection on best practices of how Te Hono o Te Kahurangi could be implemented in tertiary teaching to help achieving achieve SDG-4 in Aotearoa New Zealand is presented in this article. The specific actions depend on the needs, capacities, and resources of each institution. Incorporating Māori perspectives and knowledge into teaching and learning requires embedding them into course aims, learning outcomes, teaching material as well as assessment tasks. Incorporating Māori language, history, culture, and values into course content is very complex. As well as having guest lectures or workshops led by Māori experts or community members, curriculum design and lessons plans must be supported by relevant experts, which in this case were our Mātauranga Māori Advisers. Cultural competency and safety training, especially for non-Māori faculty and students on how to respectfully engage with the Māori culture and context will help create an inclusive environment for all.

Another way of engaging non-Māori learners could include providing opportunities for them to engage in volunteer work, internships, or other experiences that connect them with Māori communities, such as cultural immersion programs. Embedding the concepts of sustainability and environmental protection in a range of courses and learning activities, with a focus on Māori culture and traditional knowledge will not only help achieving the integration of Matauranga Māori in teaching and learning, it will also help toward achieving the sustainable development goals, in general, and SDG-4, in particular.

Author contributions

GS: Writing—editing & review, Writing—original draft, Visualization, Resources, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. SM: Writing—editing & review, Writing—original draft, Visualization, Resources, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. OM: Writing—editing & review, Writing—original draft, Visualization, Resources, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. SS: Writing—editing & review, Writing—original draft, Visualization, Resources, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

An, T., and Oliver, M. (2021). What in the world is educational technology? Rethinking the field from the perspective of the philosophy of technology. Learn. Media Technol. 46, 6–19. doi: 10.1080/17439884.2020.1810066

Aranga, M., and Ferguson, S. (2016). “Emancipation of the dispossessed through education,” in Education and Development Conference, 5–7 March 2016 Bangkok Thailand.

Demirbag, I. S. (2021). Book review: guidelines on the development of open educational resources policies. The Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 22, 261–263. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v22i2.5513

Feekery, A., and Jeffrey, C. (2019). A uniquely Aotearoa-informed approach to evaluating information using the Rauru Whakarare Evaluation Framework. Set Res. Inf. Teach. 2, 3–10. doi: 10.18296/set.0138

Hawkins, C. (2017). How does a Māori leadership model fit within current leadership contexts in early childhood education in New Zealand and what are the implications to implementing a rangatiratanga model in mainstream early childhood education? He Kupu 5, 20–26.

Hoskins, T., and Jones, A. (2022). Indigenous Inclusion and Indigenising the University. New Zealand J. Educ. Stu. 57, 305–320. doi: 10.1007/s40841-022-00264-1

Lopez, D. (2020). “Designing the peer mentoring model for international students,” in Proceedings of the 11th Annual CITRENZ Conference, 2020, 40.

MAURIORA. (2022). Cultural Competency and Cultural Safety. Available online at: https://members.mauriora.co.nz/course/cultural-competency-and-cultural-safety/

Ministry of Education (2022). Inclusive Education. Available online at: https://www.education.govt.nz/school/student-support/inclusive-education/ (accessed August 8, 2022).

Ministry of Education. (2023). Early Use of Curriculum Learning Areas and New Core Teaching Requirements. Available online at: https://www.education.govt.nz/news/early-use-of-curriculum-learning-areas-and-new-core-teaching-requirements/#implementation (accessed August 21, 2023).

Ministry of Health (2020). He Korowai Oranga Framework. Available online at: https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/populations/maori-health/he-korowai-oranga

NZQA (2017). Guidelines for Te Hono o Te Kahurangi Evaluative Quality Assurance. Available online at: https://www.nzqa.govt.nz/maori-and-pasifika/te-hono-o-te-kahurangi/guidelines/

NZQA (2018). Guidelines for Te Hono o Te Kahurangi Evaluative Quality Assurance. Available online at: https://www.nzqa.govt.nz/assets/Maori/Te-Hono-o-te-Kahurangi/Te-Hono-o-Te-Kahurangi-2018-Guidelines.pdf

SDG Tracker (2018). Measuring Progress Towards the Sustainable Development Goals. Onterey Park, CA: SDG Tracker.

Te Kete Ipurangi (2009). Te Reo Māori in English Medium Schools. Available online at: https://tereomaori.tki.org.nz/Curriculum-guidelines/Teaching-and-learning-te-reo-Maori/Aspects-of-planning/The-concept-of-ako

Te Momo, F. (2011). Whakanekeneke Rangatira: Evolving leadership. MAI Review, 2011, 1–4. Available online at: http://www.review.mai.ac.nz/mrindex/MR/article/view/437.html

Keywords: Te Whare Ako, Te Hono o Te Kahurangi framework, SDG-4, Mātauranga Māori, Kaupapa Māori

Citation: Shadbolt G, McAdam S, McCaffrey O and Shahid SM (2024) Embedding Te Whare Ako and Te Hono o Te Kahurangi to achieve SDG-4 in tertiary education in Aotearoa New Zealand. Front. Educ. 9:1400099. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1400099

Received: 13 March 2024; Accepted: 04 April 2024;

Published: 24 April 2024.

Edited by:

Ferdinand Oswald, The University of Auckland, New ZealandReviewed by:

Anthony James Hōete, The University of Auckland, New ZealandCopyright © 2024 Shadbolt, McAdam, McCaffrey and Shahid. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Syed M. Shahid, c3NoYWhpZEBlaXQuYWMubno=

Glen Shadbolt

Glen Shadbolt Stuart McAdam1

Stuart McAdam1 Syed M. Shahid

Syed M. Shahid