- Department of Design, Media and Educational Science, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark

The paper presents a longitudinal mixed methods study investigating tertiary humanity students’ dropout considerations, utilizing Tinto’s institutional departure model as theoretical background. The research question is: How do students’ dropout considerations take form and evolve throughout tertiary education? Methodically we have collected half-yearly register and survey data from 2,781 tertiary humanities students matriculating in 2017–2019. Additionally, we have conducted half-yearly interviews with 14 focus students that had high dropout considerations in the first survey round. Quantitative analysis of all humanity students and qualitative analysis of three case students are presented and discussed. The complementary analysis provides an in-depth understanding of the complex interplay between individual characteristics and institutional factors in shaping different students’ dropout considerations and decisions in tertiary education. We find that there is a stable share of students with low, medium, and high dropout considerations throughout time. However, although we find stable shares, we identify primary movements from high dropout considerations towards dropout, and from low dropout considerations towards completion, we also find considerable secondary movement (i.e., from low dropout considerations towards dropout). As is also confirmed in the qualitative analyses, there are significant fluctuations in some students’ dropout considerations. Dropout considerations are thus malleable and do not necessarily accumulate linearly over time to dropout. Individual students’ dropout considerations change repeatedly in interaction with their experiences, their expectations for the future as well as with current challenges in meeting academic and personal requirements. Challenges are often about a lack of alignment between expectations and experiences and how well students and the study programs’ norms and values match. We find students who seek to improve this match through personal transformations and others who try to change their study program. In both regards successfully improving the match seems to be a profitable strategy to prevent dropout.

Introduction

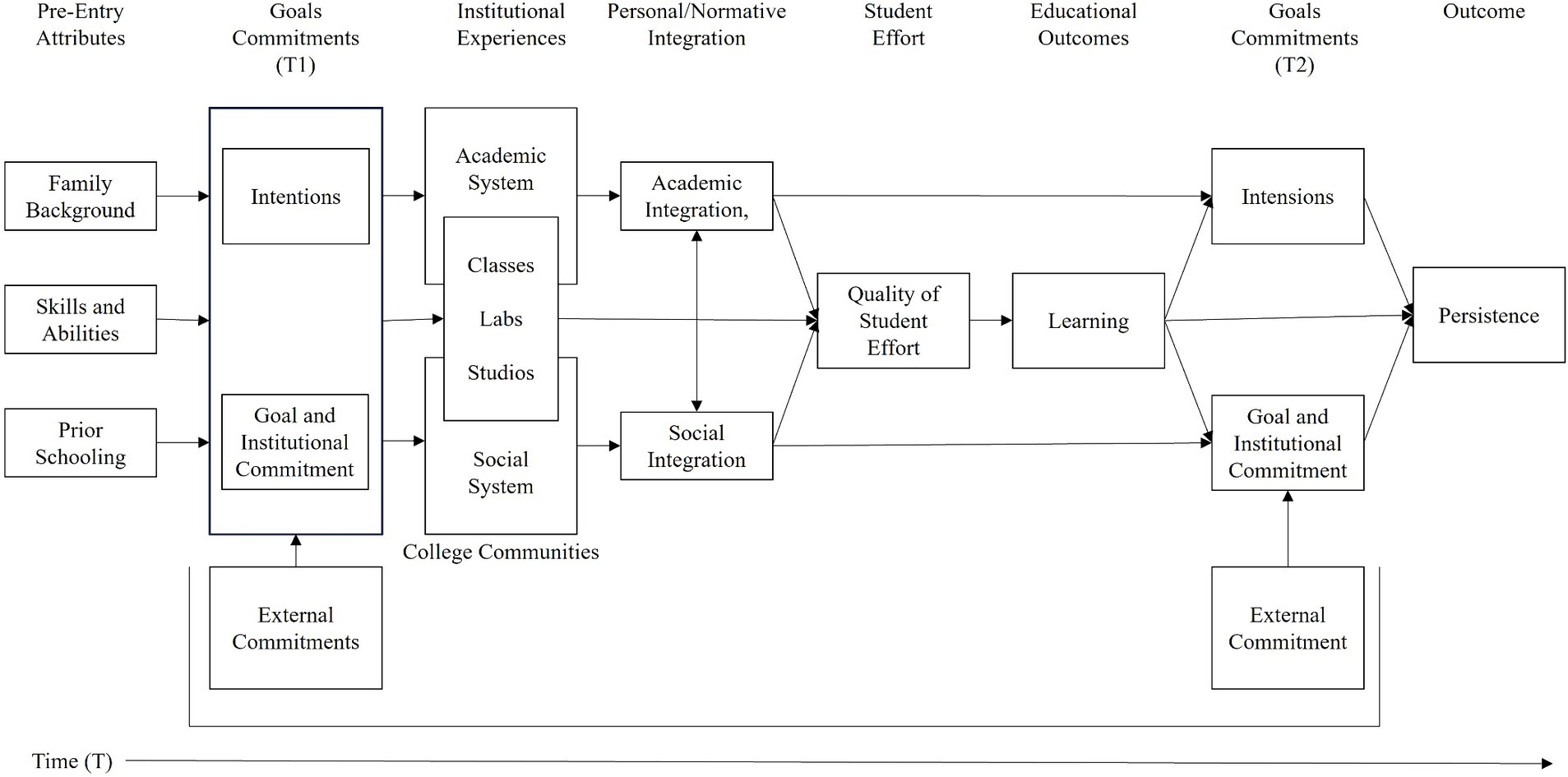

In 1975, Tinto introduced his institutional departure model as a counter-response to dropout models focusing solely on students’ psychological factors and individual characteristics (Aljohani, 2016; Gore and Metz, 2017). Tinto’s model (see Figure 1) proposed to understand dropout as a longitudinal process involving a complex matrix of interactions between the individual (including background variables such as gender, age, social background, and prior educational experiences) and an academic system with subcategories such as interaction with personnel and academic achievements and a social system with subcategories such as extracurricular activities and interactions with fellow students of the institution. The 1997 model places classroom activities (classroom, labs, studios) as straddling both the social system and the academic system, suggesting that they overlap the two systems and are keys to improving student integration or identification.

Figure 1. Modified institutional departure model (Reproduced with permission, Tinto, 1997, p. 615).

The systems continually modify the student’s academic and social integration, leading either to persistence (the choice to continue studying) or departure (the choice to drop out). This focus as well as the variables intentions and goal commitment, which in the model are proposed to mediate between the institutional meeting and persistence/departure, leave space for individuality and for dropout to be understood as the student’s active decision.

Tinto’s model has been suggested to indicate a change in paradigm in the field of dropout research and it is still today one of the most used and cited models in the field of higher education student dropout (Braxton and Hirschy, 2004, p. 89). Two of the central interrelated variables are suggested to be students’ considerations regarding or intention of dropout (Tinto, 1975) and their motivation to or intention of persistence (Tinto, 1997). These variables are also described as important mediators for dropout in a number of later dropout theories (e.g., Bean, 1983; Astin, 1984; Bean and Metzner, 1985; Eaton and Bean, 1995; St. John et al., 1996; Tierney, 1999; Sandler, 2000; Bean and Eaton, 2002). Based on this, considerations regarding or intentions of dropout are often used as an early alert proxy for dropout (Eicher et al., 2014; Truta et al., 2018). However, in a newly study on dropout among students in humanities study programs, we found dropout considerations to be a weak predictor of dropout. Although, as we show in this current article, there is a stable and high percentage of students with dropout considerations throughout the education course (between 19 and 24%), dropout considerations across semesters predict less than 10% of students’ actual dropout (Qvortrup and Lykkegaard, 2024a). Considerations about dropping out are apparently something that many students have, without it necessarily ending up with them quitting their study program. The question is then, how can we understand these considerations? In a meta-analysis of studies on human regrets, Roese and Summerville (2005) find that the two choices in life that people most often regret are their educational and career choices. Are the dropout considerations thus an expression of regret regarding the choice of education already starting during their education? Another possibility is to understand the dropout considerations not as a regret (i.e., a feeling which is linked backward to the educational choice one had made), but as a fundamental doubt linked to the future opportunities that the education provides. It is not unreasonable to assume that such a forward-oriented feeling linked to the choice of education has increased with a heightened sense of existential vulnerability and declining trust in democratic institutions (Common Worlds Research Collective, 2020). This kind of doubt is not necessarily negative, as suggested by Herrmann et al. (2015) who describe a kind of doubt among university students that is related to their academic identity and experience of meaningfulness. This doubt, they suggest, is constructive, because it causes the students to shape themselves and their identity in interaction with their social and academic environment. Furthermore, it causes them to make informed choices (Herrmann et al., 2015). This is a completely different form of student doubt than the negative one described in Hovdhaugen and Aamodt (2009), which is rooted in either administrative requirements that the student cannot handle, or in a (not always well-founded) fear of not being able to fulfill academic standards. The relevance of distinguishing between constructive and non-constructive doubt is confirmed in Hovdhaugen (2009), who shows that doubt reasoned in a lack of alignment between expectations for and experiences of the educational content in the study program, to a greater extent resulted in a change of study than doubt reasoned in other conditions, which led to dropout. However, the consequences may not be as one-sided as one risks suggesting by linking them alone to conditioning factors and results. Studies on apprentices who remain in their apprenticeship, find that dropout considerations can undermine work satisfaction and commitment (Allen et al., 2010), engagement (Halbesleben and Wheeler, 2008), and future performance (Bakker and Costa, 2014), and additionally associated with stress at work (Allen et al., 2010). Furthermore, it is suggested that the dropout considerations reflect a negative experience (Eicher et al., 2014) which may accumulate over time (Hobfoll, 2011). Because of the complexity of the character and possible consequences of dropout considerations, they are worth examining in their own right, as also suggested by Powers and Watt (2021).

In this article, we investigate dropout considerations among students in tertiary education programs in the humanities. Reasoned in the findings described above, there are two major purposes to this article: To understand (1) what characterizes students’ dropout considerations and (2) if students’ dropout considerations accumulate over time (cf. Hobfoll, 2011). The research question is:

How do students’ dropout considerations take form and evolve throughout tertiary education?

The research question will be answered focusing on different identified evolvements in students’ dropout considerations. The purpose of the article is not to reach general conclusions about the origin or size of students’ dropout considerations, or to produce final knowledge about which evolvements are most or least frequently occurring, but to draw a varied picture of different possible evolvements in students’ dropout considerations and point to possible psychological and structural reasons for these evolvements.

Materials and methods

To answer the research question focusing on the characteristics and evolvement of students’ dropout considerations, the article builds on a mixed method design with longitudinal survey, register, and interview data from tertiary Humanities students matriculating in 2017–2019. Data was collected every half year as long as the students were enrolled in the program. Our choice of design and methods for the study is based on a belief that the longitudinal data collection with the various methods provides the best basis for investigating how students’ dropout considerations might take form and evolve over time. When choosing a mixed method design, Greene (2008) accentuates the importance of having a strong inquiry logic, which must be underpinned by coherence and connection between the constituent parts (i.e., methods). In our case, the survey provides knowledge about fluctuations in students’ self-reported dropout considerations, while register data allows us to examine whether these dropout considerations accumulate to actual dropout. Interview data nuances our understanding of the fluctuations and of how students’ explain high and low dropout considerations, respectively. However, how and if different parts (i.e., methods) fit together must be determined not only based on the research interest, but also in the epistemological framework of the study. Epistemological paradigms offer logics of justification and frames of inquiry for selecting and discussing methodologies and methods that can help design and discuss how to best answer research questions and explain and discuss the relevance of different methodologies and methods (Carter and Little, 2007; Qvortrup and Lykkegaard, 2024b). The epistemology that has guided the choices of methodologies and methods in this article relates to the thinking of dropout in Tinto’s institutional departure model. The epistemological aspects of Tinto’s institutional departure model have resulted in the chosen design, which relates to the model being socio-psychologically rooted. We, therefore, chose methods that gave us the possibility of examining characteristics and fluctuations of the students’ dropout considerations, from both a focus on individual/psychological perspectives and social mechanisms/structures. We chose to do this by asking students in interviews to describe and explain individual experiences or perceptions, referring to social structures, and by looking at patterns in individual experiences or perceptions as these are represented in students’ survey responses. We visualize the survey and register data by using Sankey diagrams, which identify patterns across item responses and thus lead to identifiable paths. We do not claim that this is the full breath of possible paths, but we use these identified collective paths to detect themes that must be explained by something other than the individual, psychological perspective, namely social mechanisms or structures. By combining interviews with register and survey data we get a ‘diversity of views’ and get the chance to ‘change perspective’ (Greene et al., 1989; Greene, 2007; Bryman, 2016). Regarding the change in perspective, we increase both the breadth and depth of our analyses of students’ dropout considerations by moving from patterns identified across students to individual students’ experiences or perceptions. We thus seek to expand and strengthen our interpretation and the validity of the quantitative data by combining it with complementary interview data. Our approach is, quantitatively variable-oriented (with a focus on dropout consideration changes) and qualitatively case-oriented (with a focus on students’ reasons for and experiences of these changes).

The study employs data integration as participating students in the qualitative part are a subsample of the quantitative participants. Moreover, the study employs interpretation integration, as the qualitative case student are analyzed and presented as narrative joint displays referring to previous (quantitative and qualitative) presented data and results.

Register and survey data

We collected longitudinal survey and register data from all students in Humanities at the University of [anonymized for the sake of review] matriculating in 2017–2019 (N = 2,781) half-yearly until they were no longer enrolled (i.e., graduated or dropped out). Student descriptives are presented in Table 1. Register data were collected with exact dropout/completion dates and counted for the beginning and middle of each semester. However, unless students who dropped out actively contacted the university to let them know that they would not proceed their studies, there was a delay in dropout dates, as administrative dropout registration was not registered before students missed obligatory classes or exams.

Register data on students’ study progress (i.e., enrolled, leave of absence, graduated, or dropped out) were provided by the university along with mail addresses for all students. The survey was distributed electronically to the students’ study mails halfway through each semester and teachers were encouraged to set aside time in class for students to fill out the survey, to minimize overall dropout. We acknowledge that students self-reported dropout considerations in the middle of the semester might very possibly be different than dropout considerations at the beginning and/or end of the semester. We thus, do not perceive the dropout considerations that students indicate halfway through one semester as a proxy for dropout considerations for the entire semester. Instead, we perceive them as experiences situated in time, which we can compare to situational experiences at other times (halfway through previous and subsequent semesters). We do not anticipate linear development between points in time.

The response rates varied from semester to semester from 58% in the first semester to 15% in the sixth semester. The dramatic drop in response rates might be due to the COVID-19 shutdown, where students were home-taught and teachers thus were not able to set aside time for the survey during (physical) classes.

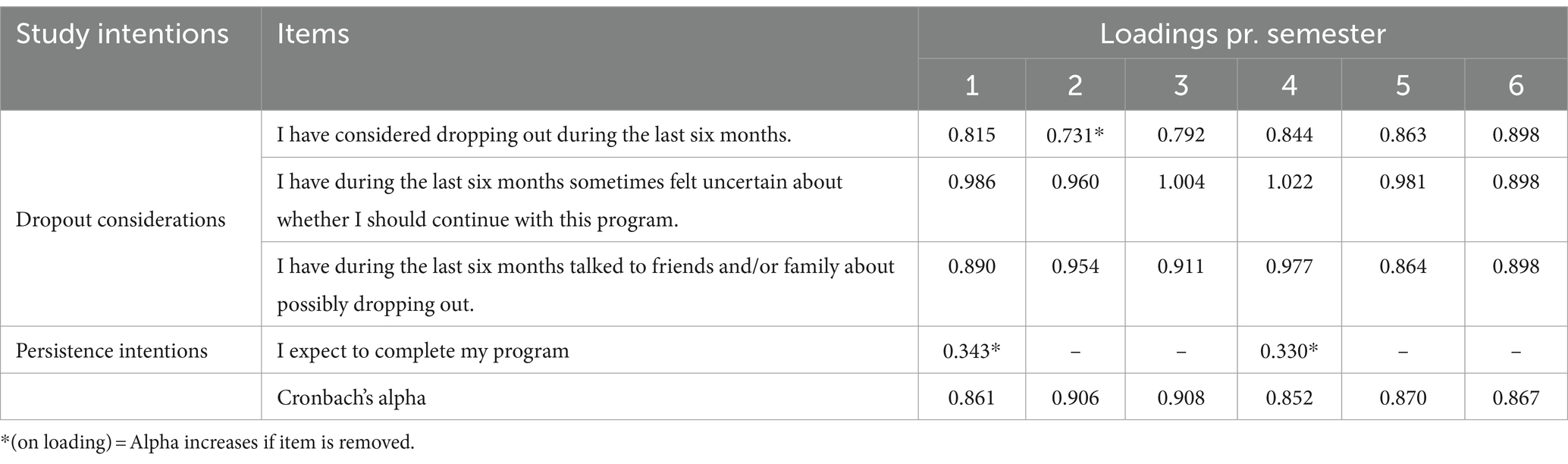

In this article, we focus on a subset of four survey items (see Table 2) related to students’ dropout considerations, answered using a five-point Likert scale. Participants were provided the option to respond “I do not know/I do not wish to answer” for all questions, and these responses were treated as missing values in the analysis.

Table 2. Item loadings and Cronbach’s alpha values for the dropout consideration factor for each semester.

Explorative factor analysis

Data were transferred to SPSS and all statistical analyses were conducted in SPSS v.28 and Excel. Data were screened for impermissible values (no values were outside the 1–5 range) and subsequently screened for missing data.

The dataset’s suitability for factor analysis was evaluated using Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (KMO > 0.5) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to openly investigate the underlying factor structure. Since the correlation test (using direct oblimin rotation) showed very small correlations, orthogonal Varimax rotation was used. Kaiser’s criterion (eigenvalues ≥1) was used to determine the number of factors, and items with loadings above 0.4 were included (Rahn, 2014). The factor reliability was tested with Cronbach’s Alpha (we use standardized α), where α > 0.6 was chosen as accepted (Ursachi et al., 2015). We performed the EFA for individual semesters (1–6) and found the same one-factor structure each time, as indicated in Table 2. Noticeably the fourth item does only load on the factor on two semesters, and for each of these semesters the loadings are below the cutoff value of 0.4 and additionally, the Cronbach’s Alpha value will increase if this item is deleted. According to Schönrock-Adema et al. (2009), a factor should contain at least three items with significant loadings and items loading on the same factor should share the same conceptual meaning. Based on this we continue our work with the three-item dropout consideration factor.

A mean value for the accepted dropout consideration factor was calculated for all students for all semesters.

Descriptive statistics and visualisation

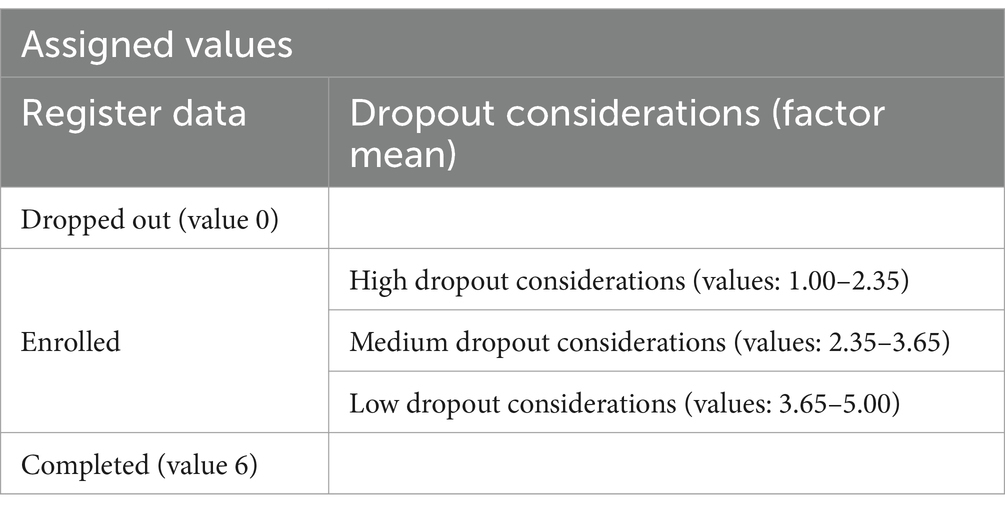

Dropout considerations (values 1–5) were analytically divided into three groups of low, medium, and high dropout considerations, as represented in Table 3. For each semester, students who had dropped out were given the value 0 (from the register data) and likewise, students who had completed their studies were given the value 6 (from the register data).

We quantified the share of students with low, medium, and high dropout considerations, respectively, as well as the share of students who had dropped out from or completed their program in each semester.

From the total population of 2,781 students, 141 students had completed surveys for all semesters while they were still enrolled in their program. We used Sankey diagrams to visualize these students’ fluctuations between low, medium, and high dropout considerations and towards either dropout or completion across the data collection points. Sankey diagrams are particularly suitable to illustrate flows and have previously been proven appropriate to visualize educational trajectories (Sadler et al., 2012; Lykkegaard and Ulriksen, 2019).

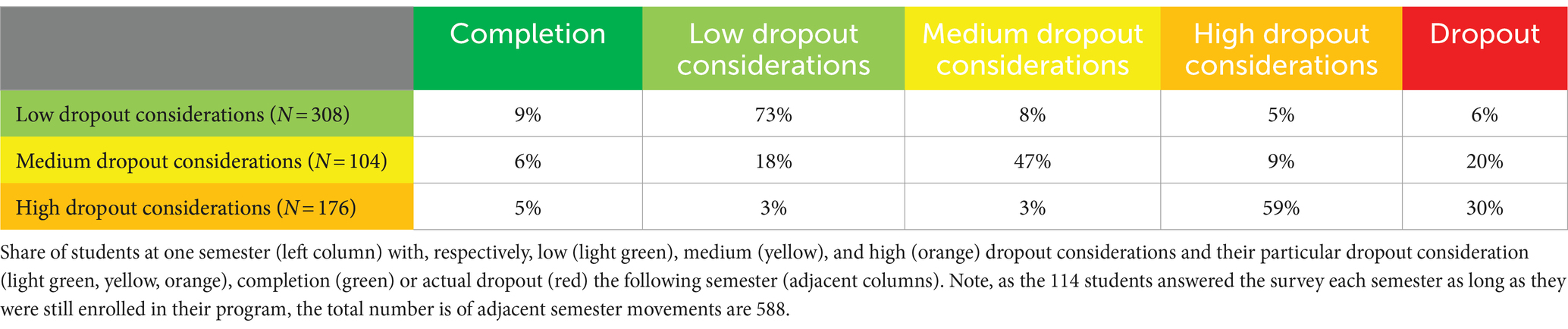

Finally, we quantified the total movements between adjacent semesters from low, medium, and high dropout considerations respectively, and towards low, medium, and high dropout considerations as well as towards actual dropout and completion.

Interviews

A sample of 14 students was selected from the first survey round based on their belonging to the group of students with high dropout considerations and because they had ticked off a box in the survey permitting them to be contacted for follow-up interviews. We chose students with initially high dropout considerations, as we wanted to enhance the possibility that some of the interviewed students would end up dropping out during our study (Hobfoll, 2011). Students’ dropout considerations were longitudinally investigated by half-yearly qualitative, semi-structured individual interviews throughout tertiary education until they graduated, dropped out, or did not respond to any more requests from the researchers. The first interview was conducted at the students’ school, the following interviews were conducted by phone while students were at home. In total 62 interviews were conducted, which each lasted between 10 and 50 min (20 min on average). The first interviews were the longest. Each interview was conducted by the first author and followed the thread and theme from the previous interview regarding students’ study experiences and accounts of their dropout considerations. All the qualitative interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

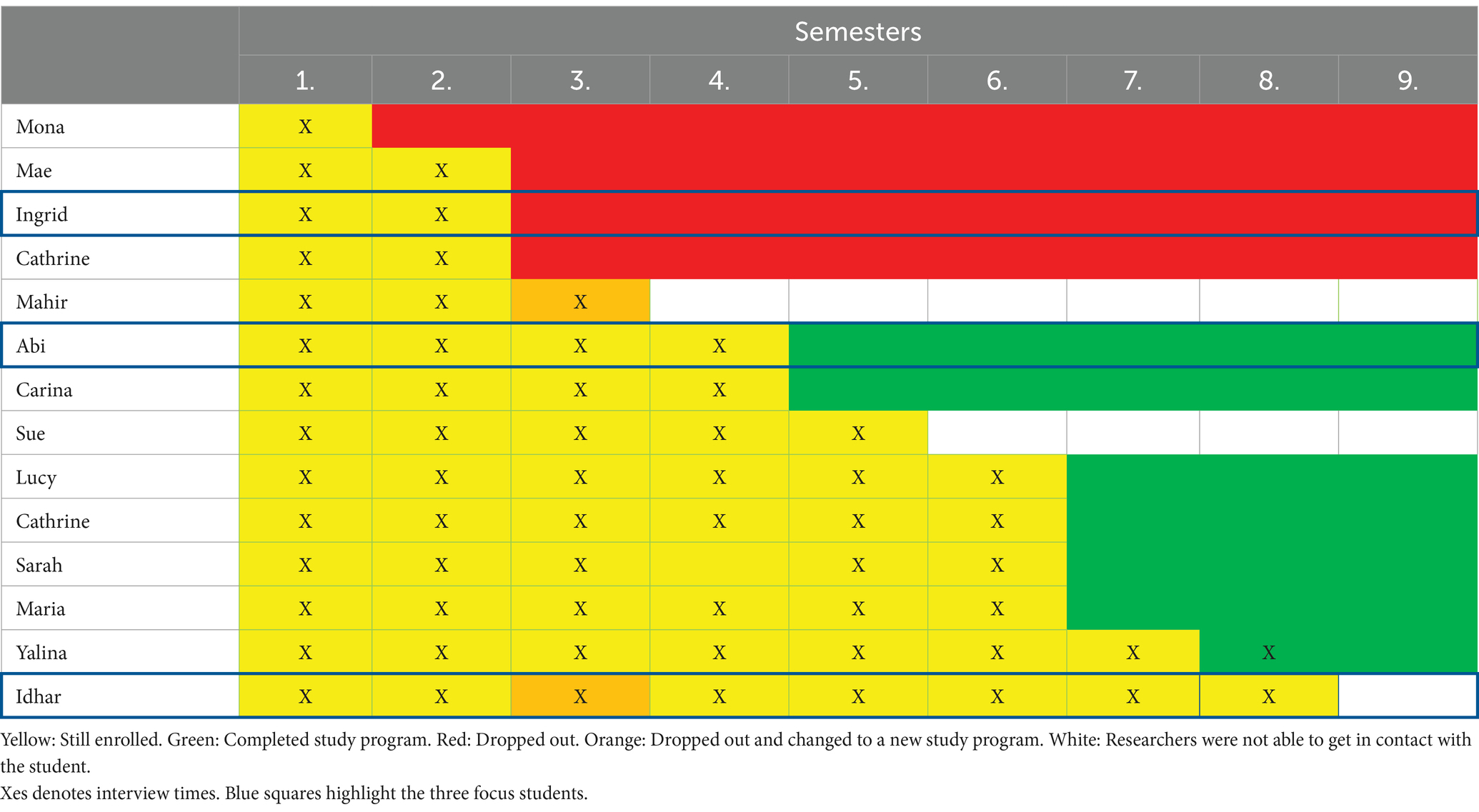

For the present analysis, we selected three case students based on maximum variation (Flyvbjerg, 2004) with one case student who completes her program, one student who drops out of her program, and finally one student who changes to another program which she completes.

Qualitative analysis

In the interview transcripts, the first author extracted the sections where the students explicitly or implicitly referred to their dropout considerations, and—true to Tinto’s Model—their experiences of the social environment, the academic environment, and classroom activities. From these extracts, the first author wrote three case stories. The stories were then analyzed one by one by the second author (with no prior knowledge of or relationship with the students) based on the theoretical framework presented in the introduction focusing on the three students’ reasons for having or not having dropout considerations, on the students’ forward/backward reasoning, on the influence of administrative and academic requirements on dropout considerations, and alignment between study expectations and experiences. Finally, the first author, with her year-long relationship with the students—validated these analyses, and we jointly wrote case presentations, illustrating the anonymized students’ tertiary educational stories and referring back to the quantitative data and between the case students’ stories.

Results

Results are presented in two subsections. The first section presents the fluctuations in the students’ dropout considerations over time (quantitative), and the second presents the three case students’ individual (qualitative) dropout considerations stories and our analysis hereof.

Fluctuations in dropout considerations

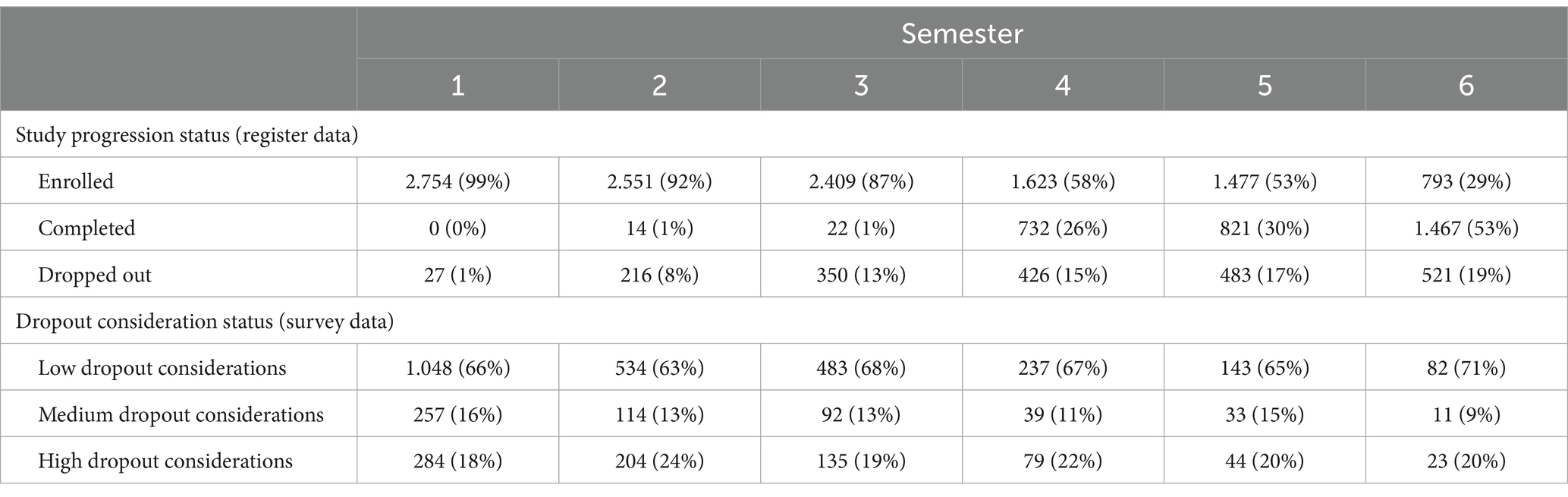

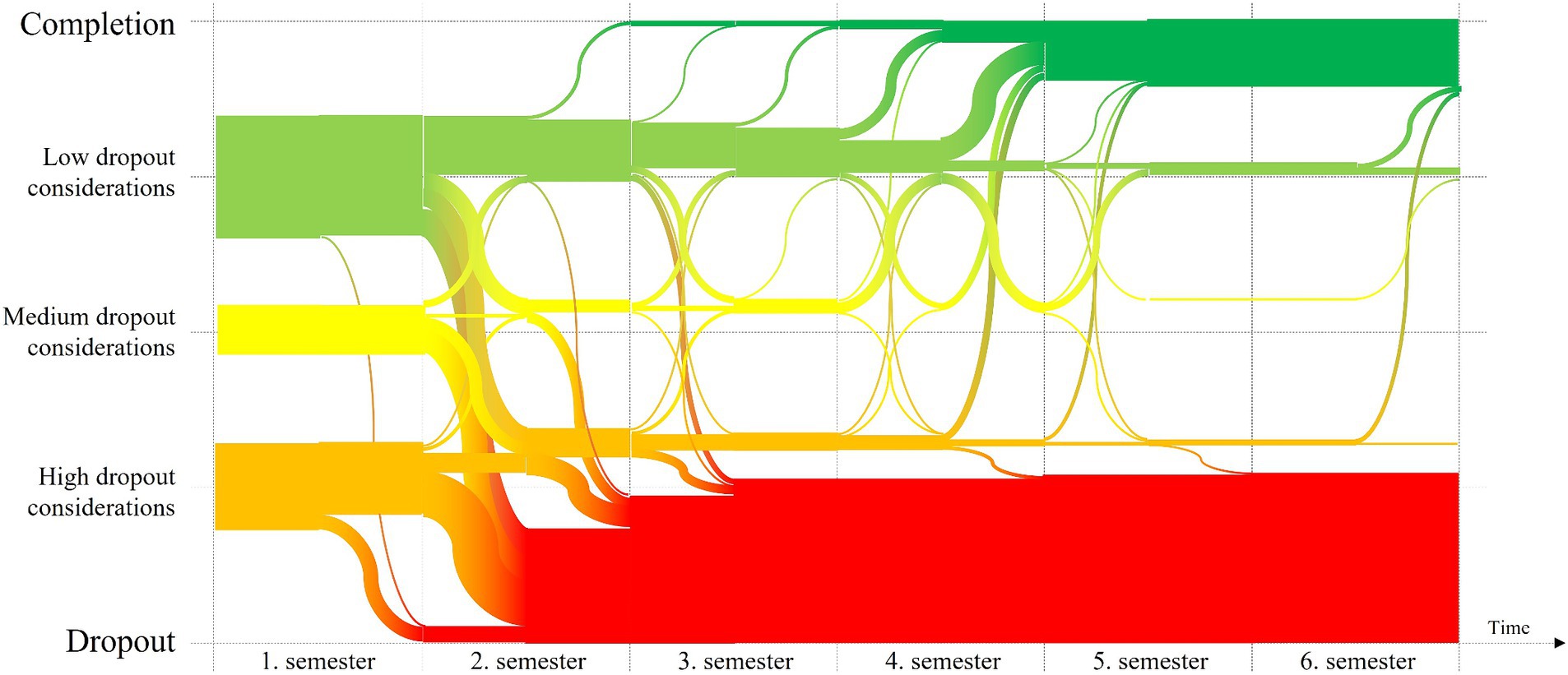

Table 4 illustrates that the share of students indicating to have low, medium, and high dropout considerations remains stable across the semester (63–71%, 9–15%, and 18–24% respectively). This stability is noticeably consistent among the enrolled students throughout a period where more and more students either drop out or complete their study program. This could indicate that some students accumulate their dropout considerations and drop out, after which approximately the same share of new students start accumulating dropout considerations without accumulating to drop out. However, the Sankey diagram in Figure 2, tells a different story, contributing to challenge the suggestion of Hobfoll (2011) that students’ dropout considerations accumulate over time.

Figure 2. Sankey diagram showing fluctuations in students’ dropout considerations. The horizontal dimension presents time and the vertical dimension presents the distribution of students (N = 141) at each semester in five different groups: Dropout (red), high dropout considerations (orange), medium dropout considerations (yellow), low dropout considerations (light green), or study completion (dark green). The colored bands illustrate the flows between the five groups. The widths of the individual bands are proportional to the share of students in it.

Figure 2, visualizes fluctuations in students’ dropout considerations between low, medium, and high dropouts. The horizontal dimension shows time with the six semesters indicated at the bottom. The surveys were answered in the middle of the semester whereas the register data were accumulated and plotted for the beginning and middle of the semester. The vertical dimension presents the distribution of the 141 students in five different groups according to dropout, dropout considerations (high, medium, low), or study completion at each semester. The colored bands illustrate the identified flows between the five groups. The widths of the individual colored bands are proportional to the share of the 141 students in it. The proportion of students identified to have “low dropout rates” is thus the wide light green band at the left top thinning out across time (moving right). This band includes both students who continually indicated low dropout considerations and those who came from medium (i.e., the yellow band) or high (i.e., the orange band) dropout considerations.

The range of different identified patterns/fluctuations represented in Figure 2 emphasizes the dynamics in students’ dropout considerations. Although there seems to be a primary movement from high dropout considerations (orange) towards dropout (red) and from low dropout considerations (light green) towards completion (dark green), there are also considerable secondary movements, e.g., from low dropout considerations (light green) towards dropout (red)—see second and third semesters in Figure 2. Likewise, there are noticeable movements from high dropout considerations (orange) toward study completion (dark green) in the fourth and sixth semesters. It is important to note, that we cannot assume linearity in dropout considerations from one measurement point to the next. Underneath the identified patterns—primary as well as secondary movements—there might be additional oscillations.

Table 5 illustrates a summed view of the students’ identified movements from low, medium, or high dropout considerations in one semester to their dropout considerations, dropout, or completion in the next semester. The dropout rate is highest for students with high dropout considerations (30%) and the completion rate is highest for students with low dropout considerations (9%), however, there is also considerable dropout for students with low dropout considerations (6%) and likewise noticeable completion rates for students with high dropout considerations (5%). With this table, it is therefore firmly established that dropout cannot, at least not for all students, be understood as a result of linear accumulated dropout considerations. We have groups of students for whom the fluctuations in dropout considerations follow a completely different non-accumulating pattern. Perhaps some of these students’ high dropout considerations are of the positive type that we referenced Herrmann et al. (2015) to describe. For other students, particularly those with low dropout considerations that drop out, the mechanism must be completely different and rapidly changing. Regarding the students, whose dropout considerations do accumulate towards dropout, based on Table 5 and Figure 2, we can conclude that the accumulations occur at different speeds (orange to red, yellow to red, and green to red in consecutive semesters).

Case students’ tertiary educational stories

Table 6 shows the educational status over time of the 14 focus students participating. The color shows whether the students are enrolled (yellow), dropped out (red), or have completed their study program (green). The focus students—who all had high dropout consideration in the first semester—were interviewed half-yearly (marked by X’es in the table) throughout tertiary education until they graduated (8 students), dropped out (4 students), or did not respond to requests from the researchers (white—2 students). Two students quit their original study program and entered a new program. The semester where they started a new program is marked by orange in the table. The three selected case students whose individual educational trajectories and dropout consideration stories will be presented in the following are indicated in the table with blue squares around. The case students are thus selected to illustrate a student who dropped out of the study, a student who completed the study, and a student who dropped out of the first study program and started a second program.

Ingrid

Ingrid is a middle-aged woman, who has been working as a youth care worker with vulnerable children for several years.

"Well, I really loved my job, but the working conditions have deteriorated so much that sometimes I can't even look myself in the mirror and hardly stand behind what we do at work. So, I felt I had to pull the plug. And I can't have any influence in the position I'm in now. So, I had many considerations about if I wanted to have an impact and make a difference, bring something else into the field of work I have, primarily with neglected children, then I needed to have different knowledge and a different title to put on it, to be able to do something else." (First interview)

Ingrid’s reason for starting her tertiary study (masters’ program) can be understood with reference to the distinction we made in the introduction between feelings referring backward (regrets) and feelings referring forwards (opportunities). Ingrid justifies her choice of study by referring backward (she loved her job but had to leave because of the working conditions). However, the quote shows that she is also influenced by forward-oriented feelings, as she sees future opportunities (different knowledge and a different title). However, it becomes clear that the forward-oriented feelings do not necessarily have a clear direction, as she is unsure of what exactly she will use the education for: “I’ve been toying with the idea of doing something else for the past three years. Not specifically what it should be, but I could feel that I needed something different in terms of work.” (First interview). Her lengthy process of deciding to quit her job has resulted in great motivation for her new tertiary education. The motivation is furthermore based on already positive experiences with successfully pursuing some other tertiary education and looking forward to more. However, when Ingrid started her studies, she felt overwhelmed:

"I was very surprised, and I felt completely thrown off. I thought, 'You can't be so stupid and clueless that you don't understand this.' I was really knocked down. I can't exactly say what it was that knocked me down, but it was as if my entire identity was being torn apart in some way." (First interview)

Ingrid herself sees one reason for her feeling that her identity is being torn apart is the academic level (cf. Hovdhaugen and Aamodt, 2009, academic requirements):

"Because I could feel it in the academic field, and we even started quite slowly, I think, looking back now, but I could feel that having to sit down and engage with reading a text and then understand it afterward, and try to extract from it with the knowledge I had back then, it was a big task." (First interview)

In addition to the difficulties in meeting administrative and academic requirements (suggested by Hovdhaugen and Aamodt, 2009), Ingrid believes that her age also affects her experience of the academic requirements: “And I can also feel that I’m not quite young anymore. My age also plays a role. I do not have the same reading speed anymore, and I do not have the same working memory when it comes to approaching new things.” (First interview). Ingrid additionally points out some personal issues. She had to work full-time alongside studying because she could not take leave from her job. This is uncommon in Denmark, where the government provides financial support (“SU”) for education. She would also like to “have time for her family” and she believes that “It can be difficult to fit it in compared to starting a study at the age of 20”:

"And this whole thing about losing… Not having anything stable, not having this structure around it, it has taken me some time to build it up." (First interview)

In addition to the academic requirements, Ingrid thus faces personal requirements within two sub-categories: financial and family care, referring to her resources, costs, and values. The academic and personal requirements jointly fueled Ingrid’s dropout considerations:

"It's been a really tough start. And I've also been close to quitting and thought that I shouldn't expose myself to this […] My goal was that I would try until the fall break [the semester starts in September and the fall break is in October]. I said that I had to do that, otherwise, you simply can't just quit. But until the fall break was my goal, and then it had to bear or break, whatever was going to happen then. Also, if I found out whether I could even learn this. And if I can figure out how to write in this way. And I have now realized that I can. It just takes time for me. It takes time for me to read, understand, and use it academically. […] And when I had written it [exam assignment during the fall break], been through it, and passed it, I could feel that I had the courage for more. Because I've always found this incredibly exciting. It's incredibly exciting to be enriched by different knowledge and knowledge from completely different angles than the ones I encounter in my work practice and in my social circle. It gives me a lot to encounter knowledge in this way." (First interview)

Thus, Ingrid’s dropout considerations were fueled by negative experiences, as described in Hovdhaugen and Aamodt (2009). However, as the above quote shows, the dropout considerations also seem to be counteracted or diminished by positive experiences. Ingrid has the experience that she has cracked the academic code. At times she seems surprised and impressed by her knowledge and her new study approach. She says, “And sometimes I can hear myself saying ‘how do you know that’?’, ‘what is it based on?’. I have suddenly started to be much more critical regarding what I read. In what I am asked to do, and in the way I approach things.” (First interview). At this point, she no longer had dropout considerations:

"No, because then I took the next step, which was until Christmas. I have taken it very gradually to keep myself up saying, this is what I need to do right now. My considerations about it are that I cannot have both a full-time job and study on the side. And I don't want to do that to myself. I don't want to do both things halfway. So, I have to make a decision soon about what I'll do. And it's simply because I can only get SU [student grant], and I can't live off that. I must realize that I simply can't. I don't want to have to sell my house and everything for that…" (First interview)

Ingrid’s experience of being able to master requirements added to her personal transformation:

"It has taken me a long time to set aside my youth care worker title and get used to the student title. This thing about being a student. I might be a youth care worker, but right now, I am a student, and this is where I am, and this is what I have to deal with." (First interview)

However, the dropout considerations returned, and at the end of the first semester, she says “But I can feel now that the study has taken a turn because I am currently experiencing that it has become really difficult. It’s because there is a lot of literature in English, and it requires even more of me to deal with it.” Once again, she has given herself a new deadline. She said: “Now I have at least tried to finish it until Easter [halfway through the second semester] where there will be a change again.” (First interview). By the time of the second interview, Ingrid says:

"Well, the way it's gone is that shortly after we talked, I think it's at that point I go on sick leave. Or at least I become ill. And I am sent to the hospital for a check, with the aim of diagnosing cancer in my stomach and then subsequently cancer in my throat." […] After about a month and a half in the diagnostic process, fortunately, cancer is not found. Something else is found, but it is not life-threatening in any way. But after that period, there is an exam, and I would say that's when I really hit rock bottom." (Second interview)

"And then I couldn't bear the idea that I had to be in it […] So, the study is on hold because I haven't enrolled in classes here after. And I haven't done that because then I completely fell out of the system. And I could see that I couldn't catch up within the standard time that the study is set for." (Second interview)

Ingrid therefore drops out. She says:

"It was very much about the content. And what can one say about the teaching or the teachers, it has been very different […] I think I became unsure of those times when we had subjects where we had multiple teachers. And where those teachers disagreed on how the teaching should be." (Second interview)

"I guess it was me who didn't really fit into it. And I had become too old. And it was also nonsense that such an old woman like me should engage in it. That's how you can quickly belittle yourself." (Second interview)

Ingrid describes difficulties in figuring out and managing what she was supposed to do. She, on the one hand, finds herself unfit for studying. On the other hand, she still finds the study program interesting.

"Right now, I'm thinking that, for one thing, I really miss reading a lot. I miss incredibly much this thing with the knowledge […] And it's incredibly interesting at the same time as it's also insanely challenging. And I could feel that it had been many years since I had been in a classroom. […] I hope that I can find a solution and come back to it [the study]. Because I really think it was really fantastic." (Second interview)

Through the course of our study, Ingrid experienced many fluctuations in her dropout considerations. It was by no means a cumulative one-directional movement that made her dropout, it was ups and downs, and in the end, she explains her dropout with a heavy personal experience. However, we cannot help wondering, whether this experience also in some way set her free from her academic struggles.

Table 5 and Figure 2 illustrated movements and fluctuations based on our survey and register data, we saw how some students’ dropout considerations followed a non-straightforward movement. Ingrid illustrates, such non-straightforward movements. Her story additionally show that these movements can take place over rather short time intervals. In the following, we present Abi’s story and the movements in her dropout considerations.

Abi

Abi is a newly graduated journalist, and after spending 6 months searching for jobs and feeling that she lacked some academic knowledge to convey, she applied for a two-year master’s degree program:

"I could sense that it was something I thought could be exciting. But I just think that what happened quite quickly when I started the program was, I didn't feel like it lived up to what was described about it." (First interview)

What Abi describes early on in her study, is an example of the lack of alignment between expectations for and experiences of the educational content in the study program, as described by Hovdhaugen (2009). Abi justifies her expectancy-experience frustrations by the fact that she was not familiar with the way of working at universities. This issue is discussed by Abi throughout her studies:

“There are some things I notice because my education was so practical compared to those who are used to studying at home. You read, you attend lectures, then back home.” (First interview)

“And it also became very clear to me during the method project because then I chose to ally myself with someone who was quite academic and who came from the history study. And there were just so many things that she knew as a matter of course about how things should be structured, and so there were many of the things I had written that she asked me to make more academic because I’m brought up in a completely different way. Things should ideally be as understandable as possible. Where sometimes it can seem like almost the opposite is what you aim for in those assignments.” (Third interview)

According to Hovdhaugen (2009), dropout considerations reasoned in expectancy-experience misalignment might lead to a change of program (instead of dropout). For Abi, however, her decisiveness, caused her to stay in the program.

“So, there’s also something in my upbringing, in that I would feel it as a personal failure if I dropped out of something I had committed to and started. In terms of my future, for example, I have a father who really wants to further his education, he’s a vocational teacher, and it’s really difficult for him to do anything because he doesn’t have a higher education than that. There’s also something in that, that regardless of whether I feel like I can use it for much right now, I think it’s really nice to have that master’s degree with me. And I also went into this education with the premise that it's just a year in the classroom, and then I would have this internship in the third semester, and then the master thesis for another half year, and that’s it. So now I’m also so far along, so I think I’ll stick with it. If I get an internship placement, that is, I’ve been applying a bit now.” (First interview)

Here we see, just like with Ingrid, that the way Abi handles her dropout considerations is based on feelings referring backward, both to her own experiences of not being allowed to fail, but also to experiences from her father’s lack of success. However, she also briefly mentions some forward-oriented feelings with the wording that it’s nice to have that master’s degree with me. But to realize the opportunities described as part of the forward-oriented feelings, there is a hard battle to be fought. Fortunately, Abi has a genuine interest in the field:

“But somehow, what’s at the core of the study, that is still what I find interesting.” (First interview)

However, her decisiveness and interest does not stop her from momentarily being filled with dropout considerations:

"But here in January, for example, when we had this week-long exam, and when I otherwise had time off, I was looking at job postings a lot. Because it takes something to hold onto someone like me, because I know that I have an education that I could just go out and use for something. In principle, I could just go out and enter the job market now." (Second interview)

Abi’s considerations about dropping out largely revolve around the study program or what Tinto (1975) terms the academic system. She did not feel that she was sufficiently challenged academically:

“I attend the classes and I study my material. I want it to make sense to me. But then you sit, for example, in this class yesterday, and I feel like it's the same thing that was covered last week. And it's also because they have to consider that we come from so many different places, but some things are really spoon-fed. Where you think, we can probably move on to something else now." (First interview)

In addition to the academic level, Abi thought the program lacked depth, that it tried to cover too broad a spectrum, and she says that she often “misses the point” of the texts they read and therefore questions their relevance. Interestingly, Ingrid’s experiences of lack of understanding lead her to criticize herself (lack of skills), while Abi directs the problem at the study program. It seems that the former inward orientation increases dropout considerations, while the latter outward orientation decreases them.

A final outward critique from Abi, has to do with her being dissatisfied with the teachers, and her dropout considerations are therefore also reasoned in Tinto’s (1997) category ‘Classroom activities’. Abi has been openly critical of the teachers since the first semester, and this criticism continues throughout the rest of the interviews:

"I actually think we had some really bad teachers." (First semester)

"I mean, I also think I've said this many times during our interviews, that they are indeed very academically skilled teachers. It's just that some of them are so academic that they also forget to be good at conveying information. And that's probably because they primarily prefer to be researchers rather than teachers. But they do know a lot about what they're teaching." (Fourth interview)

When Abi addresses the problematic issues she sees in her study program, she is repeatedly told that it will get better in the next semester, that it will then make sense e.g.: “we were constantly told by our tutor that this teacher is a bit special, but after the fall break, it will get better.” (First interview), but that is not her experience. Thus, the consequences of a lack of alignment between expectations and experiences described in the introduction referring to Hovdhaugen (2009), apply not only to Abi before and after the start of her study, but also during it. Abi is not comfortable leaving the gap between expectations and experiences open, perhaps because she does not believe that it will be possible to close the gap she is experiencing. Abi finds it unsatisfactory that things do not “make sense” in the present:

"And that's what made me really dissatisfied in the first semester. You must get a feel for everything but don't know what to grasp. And then you sat there until January and had to do a week-long exam and write an assignment, and maybe it was only then that you had time to understand the theories you needed for the assignment." (Second interview)

Abi does what she can to close the gap between expectations and experiences and make sense of the theories herself. As part of this sense-making, she decides that she wants to do an internship as part of her education in the third semester. However, she cannot find any information about it anywhere. She knocks down doors until she succeeds in arranging an information meeting for herself and for her classmates:

"There wasn't meant to be an info meeting, no. Which has come about because I could sense that there were many who were interested in hearing about this internship. But it's a cumbersome process, and it's something you have to be passionate about to get through." (Second interview)

As illustrated in the above quote, Abi constantly encounters challenges, but as we saw earlier, she does not turn the problems inwards to the same extent as Ingrid, she turns them outwards and acts. All in all, Abi’s frustrations several times make her react and try to change things in her program and classes. Other times, it makes her sit quietly in class:

"I find it difficult to constantly… Well, this bad atmosphere that's actually in the class about the teaching… You can't just complain without doing something about it either. But it's also very unclear what to do about it. So, I probably try to keep quiet sometimes." (First interview)

As is obvious from the above quote, Abi cares about the atmosphere in her class, however, she was not initially that socially invested in her class, and she does not believe that her class’s social environment is that good. However, Abi shares how she strategically chose her study group partners. Particularly the girl, already mentioned, who came from a completely different background than her.

"I had singled out her who I knew was really sharp in those, you know, overarching academic things from uni, and then we also found a third person." (Fourth interview)

And a bit to her surprise, Abi ends up getting quite close with her study group. “The two I wrote the method project with, I’ve become quite good friends with them.” (Third interview). However, when it came to her earlier dropout considerations, Abi used only her family, boyfriend, and friends outside the university to discuss this:

"My boyfriend also listens to a lot. And one of his friends, who is actually doing a Ph.D. […] I've actually talked to him quite a bit because he says he just loves studying and thinks it's great. He really keeps saying that I should drop out. He thinks I should drop it and that you shouldn't do something you're not happy with. But I actually had a successful experience with this [latest] exam. And it was really nice to get grades on that because I had kind of set it as a goal, that if it didn't go well with that, then I actually didn't understand at all what we were doing in this study program, and then I shouldn't be here. But it went well." (Second semester)

Hovdhaugen and Aamodt (2009) describe how a (not always well-founded) fear of not being able to fulfill academic standards, might increase dropout considerations (like for Ingrid), however, for Abi the positive experience of being able to fulfill requirements helped reduce dropout considerations.

During the second semester, Abi got the internship placement she wanted, which helped things fall even more into place for her. “The whole second semester was actually also in the light of knowing that I was going to intern in the third semester,” and when asked about her dropout considerations in the third semester, she responds: “No no no, we are finishing it now, unless it completely messes up in the master thesis, of course.” Abi did a so-called product-based master thesis. Again, she struggled to find information on how such a thesis could or should be constructed:

"And I can sense from my teachers that it's not because they have a lot of experience with these product theses either. But I think maybe it's up to me to figure out how to put it together." (Third interview)

"However, in terms of my concern about figuring out what I can use the program for, there must be something I can figure out because I got an A for the thesis." (Fourth interview)

It is a great success for Abi to overcome the challenges she has been through. The reason for her expectancy-experience gap and continuous challenges and dropout considerations not cumulating to actual dropout, might be, that she, unlike Ingrid, attributes these challenges outwards and thus, does not need to face challenging personal transformation.

In the following, we present our third case student, Idhar. She too is experiencing challenges and has dropout considerations. For Idhar the challenges led her to change her study program.

Idhar

Idhar is a young woman, who is very motivated to continue studying and to attend a university study after upper secondary school. However, she has had a hard time figuring out what bachelor’s program to choose:

"And my grades aren't very high, so I couldn't just apply to any program that I had in mind. Before I even applied to any programs, I wanted to study to become a social worker, even though it's not at the university. Also, because it suits me more. But I couldn't because of my grades. So, I had to see what else I was interested in." (First interview)

After upper secondary school, she applied for different bachelor programs, but did not get into her first choice: “But then I was accepted into another one, and I thought I would give it a chance because now I had chosen it as my second priority” (first interview). Idhar had expectations for the educational content and level of this program and when asked, she said that the academic level was very appropriate, but that she did not like the teaching that much:

“[In a specific class], I think everyone there is about to fall asleep. It's very heavy. It's like you get a million new terms thrown at you, and you just have to learn it at that point when you're reading it […] It's more because you want to discuss because maybe you have some other viewpoints. But I can't really do that because it's not the place for it.” (First interview)

Idhar experiences a gap between her expectations for and experiences with Tinto’s (1997) category ‘Classroom activities’. We wonder whether this classroom expectancy-experience gap was what later resulted in Idhar’s change of study, as Hovdhaugen (2009) argues, that doubt reasoned in expectancy-experience misalignment of the educational content, to a greater extent results in a change of study than doubt reasoned in other conditions. In any case, Idhar has had many dropout considerations right from the start of the program.

"But when I started, I felt a bit already on the first day that it wasn't really for me after all. It just wasn't what I had expected. I don't know how to explain it. But I just feel that it was very different from what I had anticipated. So, I was actually quite disappointed. And then I thought, 'okay, it's only the first day, you just have to give it a chance.' And now I'm in the second semester, and I still feel the same way." (Second interview)

Even though Idhar from day one did not feel a match with her current study program, she stayed in it for a while. This was for her (like Abi) a question of not being a quitter:

"[I'm thinking] that I want to give it a chance. Because I don't want to be someone who just drops out right away without giving it a chance. You can't really judge it from one day or a few weeks. So, I thought I just had to try to see how it would go. And if it doesn't start to become more interesting over time. It could be that it just seemed a bit dry at the beginning. But now I've concluded that I'll probably switch to something else when I get the chance." (First semester)

The studies described in the introduction found that increasing or cumulative dropout considerations might lead to reduced work satisfaction, commitment, engagement, and stress (Halbesleben and Wheeler, 2008; Allen et al., 2010). However, Idhar manages to accept her position and it seems that something different than assumed from these studies is happening. She keeps her learning motivation high, despite her likewise high dropout considerations:

"Even if it's not interesting or something I'll need in the future, I feel that all knowledge is good knowledge. Because then I know those things. Because it may be that I'll need it at another time, or if we need something similar in the new program. Then I already know it. So, it's not like I've completely tuned out and just shown up and sat and listened to nothing. Because many asked if I wasn't wasting my time. But then I replied that I don't feel like I am because I'm still learning something. Maybe it's not what I'll be studying in the future, but I can still use it in some way at some point." (First interview)

Idhar feels that her current study does not fit her, and thus we also here identify aspects of the need for inward or outward changes to reach a match. Idhar does not engage in inward personal transformation, as we saw Ingrid did. She does not either work to change the program to create a better match, as we saw Abi do. For Idhar, the mismatch increases, which increases her dropout considerations but still does not lead to dropout. Idhar decided to stay in the program for a full year until she could apply for and start the new study program. Hovdhaugen (2009) suggests that expectancy-experience gaps can lead to students changing programs. However, Idhar’s decision to stay at the old program for a year is more difficult to explain. For Idhar, there might be a sociocultural reason behind this. For a long time, she did not share with her parents that she wanted to drop out and start a new study program, and when she did, it took some time for her parents to understand her decision. From her description of this, one gets the feeling that when Idhar emphasizes her not being a quitter, it can be related to her parents’ concerns about wasting time, getting into—what we refer to as—a cumulative trajectory toward dropping out, and not taking advantages of the opportunities they did not have:

"And then my mom asked how it was going with my studies, and I replied that it was fine, but that I still don't know if it's what I want. And she had a little trouble understanding it because she wondered why I had chosen it. Because parents are just like that, if you choose something, then it's also the only thing you have to do for the rest of your life." (First interview)

“My sisters, they've been quite indifferent. I mean, they can't really see the problem in changing program, but my mom had a bit of a hard time understanding it because, for her, she felt like I had just wasted a year on nothing. And also, because she thinks that since I'm changing program now, I'll probably get tired of it at some point and want to change again and stuff like that." (Third interview)

"I think it's a general thing with Arab parents. Because, for example, many who come to Denmark don't have such great chances of getting an education and then maybe there have just been some linguistic barriers and such. And then they just want you to achieve what they didn't achieve." (Fifth interview)

Idhar ends up changing to another program and she is initially very happy about it. She excitedly talks about her new program, and links her excitedness closely to aspects of the social system in Tinto’s (1975) model:

"So, I'm very pleasantly surprised, but I also think that the social aspect has a lot to do with it because, in the last couple of years of lower secondary school and throughout upper secondary school, I just haven't really been in any classes where I felt like I belonged. Or where I fit in […] There are a lot of people on this program who are just like me." (Third interview)

As she approaches the end of her bachelor’s degree, when she begins to look forward to a master’s degree, she cannot imagine that it will be as good socially in a subsequent master’s program, as it is in her current bachelor’s program: “I actually think it will be a little more difficult.” (Eighth interview). Idhar also experiences that the good social environment (and the small class size) influences the teaching of her new program.

"I also think it plays a role, the relatively small size, it's very small so we're not very many. So, it also provides an opportunity to talk to everyone across the class.” (Fourth interview)

Idhar is also very enthusiastic about the academic system (cf. Tinto, 1975) in her new study program;

"And I don't really feel like I've had that, what can you say, that eagerness or that enthusiasm for classes before. Or just for showing up at all. So, I can definitely feel that it has made a really big difference to go to a place that you're happy with and to have good people around you whom you also talk to and can share your frustrations with regarding the study and exams, and so on. So, I just think that it's really important that you're satisfied with what you're doing because it also affects everything else." (Fifth interview)

As she progresses further into the program, she experiences that there is a big difference in the quality of the teaching she receives.

"So, basically, I really think it has been very varied, depending on what semester you've been on, so, I would definitely say, well, that there are some teachers who have been much more equipped for the job than others." (Eighth interview)

Her overall experience of the classes depends a lot on the fluctuating teacher quality, and for Idhar, Tinto’s (1997) category of classroom activities seems to be decisive for the development of dropout considerations.

Thus, although Idhar was very enthusiastic about her new program, with time her enthusiasm began to fade.

"The first year, and the first semester of the second year, I think, has been the most exciting part of the study. We had some insanely good classes there, and also some really sharp teachers, so yeah, well, then I was convinced that this was the path I wanted to take because it also paved the way for what I was considering in terms of career and so on." (Eighth interview)

"Because I had just lost the enthusiasm, these last two semesters actually here on the bachelor's." (Eighth interview)

Even though Idhar is starting to feel a bit weary of her program, it is important for her to complete not just the bachelor’s degree but also to pursue a master’s degree afterward.

"I really want to finish it. Otherwise, I'll have to listen to a lot of annoying comments again [laughs]. No, well, initially, I really want to complete my bachelor's, and then maybe I'll do something else until I want to start on the master's." (Fifth interview)

Idhar begins a master’s degree directly after her bachelor’s degree. She does not explain why she does not end up ‘doing something else’ before matriculating a masters’ program. We wonder, again, if it for Idhar is for sociocultural reasons. Anyhow, we will conclude her story, with a general observation she makes about societal expectations regarding education:

“For example, when you're in primary school or upper secondary school and you're about to apply for tertiary education or talk about it. I feel like society has this idea that if you choose a program, you should just finish it quickly, right after completing upper secondary school. I think it's mainly because we're in such a hurry. Even though I'm only 21 and about to start my second year at university […] Well, there's just no room for taking your time, you know? The educational opportunities are abundant, so it's not like you could ever fall behind. People are studying, even some in their 40s who are still studying to complete upper secondary school. So, it's never too late. I just think it's a general mentality we have.” (Fifth interview)

Idhar experiences a lack of harmony between what for her is a dominating idea in society, namely that educational trajectories must proceed linearly and pacey through unproblematic transitions, and her desire to take her time to engage in and reconsider her studies. Idhar’s concluding remark is an excellent starting point for summing up the article’s interest in understanding students’ dropout considerations and whether they contribute to developing or challenging young people’s educational self-images.

Limitations

The presented findings rely on students’ self-reported dropout considerations, collected through surveys and interviews, and relates these to actual dropout and study completion data from institutional register data. While self-reported data is essential for understanding individual dropout considerations, it inherently introduces the possibility of social desirability bias. We thus acknowledge that the students interviewed may not have disclosed all the reasons for their dropout considerations. However, we hope that our prolonged engagement with the students helped mitigate some initial social desirability bias, enhancing the credibility of the data as suggested by Lincoln and Guba (1985).

Our study aimed to investigate how students’ dropout considerations fluctuate over time and to point to possible psychological and structural reasons for these evolvements, rather than provide generalizable conclusions about the prevalence or origins of these considerations. This aim affects the generalizability of the article’s results, as findings are situational and may differ if conducted in a different context. For example, it may influence Danish students’ dropout considerations significantly that they receive public support (SU) for tertiary education regardless of social standing, which is not necessarily the case in other countries. Additionally, both the demographic composition of our sample, i.e., the share of minority students (see Table 1), and the mix of bachelor’s and master’s students, could impact the results. As the purpose of the article was to draw a varied picture of different possible evolutions in students’ dropout considerations and point to possible psychological and structural reasons for these evolutions, we found it relevant to include a variety of student types. However, it is important to note that the selected students may not represent the full spectrum of student experiences and dropout consideration fluctuations. Adding to this, we might also have arrived at a different understanding of dropout considerations, if we had not chosen solely students with initially high dropout considerations for the qualitative part of our study. Finally, the timing of our surveys—conducted halfway through the semester—may have influenced the findings, and different results might have emerged if we had surveyed students at the start or end of the semester. In sum, our study has several contextual limitations, and we encourage future research to validate, extend, or challenge our findings in other contexts.

Discussion

When focusing on the entire student group, we find that there is a stable share of students with low, medium, and high dropout considerations throughout time. In that sense, it could be explained with the suggestion of Herrmann et al. (2015), that doubt is a faithful—thus stable—study companion. However, although we find stable shares of low, medium, and high dropout considerations, we also find that this is not an expression of stability in the individual student’s dropout considerations, nor does it mean that students’ dropout considerations accumulate linearly over time. Both the quantitative and qualitative studies make clear that there are significant fluctuations in some students’ dropout considerations. Based on this, the study confirms both the article’s hypothesis that dropout considerations are malleable and the relevance of Tinto’s (1975) suggestion to include time as an interacting variable when it comes to understanding student development in relation to dropout and persistence, respectively.

Our detected dropout considerations fluctuations challenge Hobfoll’s (2011) suggestion that students’ dropout considerations accumulate over time. Although there seem to be primary movements from high dropout considerations towards dropout, and from low dropout considerations towards completion, there are also considerable secondary movements (i.e., from high dropout considerations to completion). Instead of a cumulative development, it is rather the case that the individual student’s dropout considerations change repeatedly in interaction with the students’ previous experiences, expectations for the future as well as changes in the student’s academic and personal circumstances.

Like Hovdhaugen and Aamodt (2009) we find a relationship between uncertainty regarding the ability to meet administrative and academic requirements and dropout considerations. Conversely, we also find that considerations about dropping out may be fueled by students’ feelings of not being sufficiently challenged academically. The reason for experiencing academic shortcomings can thus be linked both internally to the students themselves and externally to the academic program. Furthermore, to the academic requirements, we add personal requirements as drivers of dropout considerations. We find personal requirements linked to dropout considerations in both the form of financial requirements and family care (which are linked to the student’s resources, costs, and values). For both academic and personal requirements, we find that the challenges are often about a lack of alignment between expectations and experiences, as described by Hovdhaugen (2009).

We suggest that the gaps between expectancies and experiences could be explained by how well students and the study programs’ norms and values go along (i.e., academic language as a norm, valuing that teaching must make sense in the moment, describing oneself as not being a quitter, etc.). This is what Eccles et al. (1997) describe as a person-environment fit. From previous studies of educational person-environment fits, we know that a lack of fit can affect students’ well-being, motivation, interest, behavior, academic performance, and future job opportunities (Eccles et al., 1997; Tuominen-Soini et al., 2012; Holmegaard et al., 2014; OECD, 2022). Thus, the outward or inward changes to improve person-environment fit, which we see some students in our study engage in, might be a profitable strategy. It is interesting that we not only find that dropout considerations can be nurtured by negative experiences, as suggested Hovdhaugen and Aamodt (2009), but can also be reduced by positive experiences.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available for privacy reasons. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

EL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AQ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aljohani, O. (2016). A comprehensive review of the major studies and theoretical models of student retention in higher education. High. Educ. Stud. 6, 1–18. doi: 10.5539/hes.v6n2p1

Allen, D. G., Bryant, P. C., and Vardaman, J. M. (2010). Retaining talent: replacing misconceptions with evidence-based strategies. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 24, 48–64. doi: 10.5465/AMP.2010.51827775

Astin, A. (1984). Student involvement: A development theory for higher educations graduate school of educations. Los Angeles, CA: University of California.

Bakker, A. B., and Costa, P. L. (2014). Chronic job burnout and daily functioning: a theoretical analysis. Burn. Res. 1, 112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.burn.2014.04.003

Bean, J. P. (1983). The application of a model of turnover in work organizations to the student attrition process. Rev. High. Educ. 6, 129–148. doi: 10.1353/rhe.1983.0026

Bean, J. P., and Eaton, S. B. (2002). “A psychological model of college student retention” in Reworking the student departure puzzle, vol. 1. ed. J. M. Braxton (Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press), 48–61.

Bean, J. P., and Metzner, B. S. (1985). A conceptual model of nontraditional undergraduate student attrition. Rev. Educ. Res. 55, 485–540. doi: 10.3102/00346543055004485

Braxton, J., and Hirschy, A. S. (2004). “Reconceptualizing antecedents of social integration in student departure” in Retention and student success in higher education. eds. I. M. Yorke and B. Longden (Maidenhead, Berkshire, England: McGraw-Hill Education (UK)), 89–103.

Carter, S. M., and Little, M. (2007). Justifying knowledge, justifying method, taking action: epistemologies, methodologies, and methods in qualitative research. Qual. Health Res. 17, 1316–1328. doi: 10.1177/1049732307306927

Common Worlds Research Collective . (2020). Learning to become with the world. Education for future survival.

Eaton, S. B., and Bean, J. P. (1995). An approach/avoidance behavioral model of college student attrition. Res. High. Educ. 36, 617–645. doi: 10.1007/BF02208248

Eccles, J. S., Midgley, C., Wigfield, A., Buchanan, C. M., Reuman, D., Flanagan, C., et al. (1997). Development during adolescence: The impact of stage–environment fit on young adolescents' experiences in schools and in families (1993). Adolescents and Their Families 74–85.

Eicher, V., Staerklé, C., and Clémence, A. (2014). I want to quit education: a longitudinal study of stress and optimism as predictors of school dropout intention. J. Adolesc. 37, 1021–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.07.007

Flyvbjerg, B. (2004). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Sosiologisk tidsskrift 12, 117–142. doi: 10.18261/ISSN1504-2928-2004-02-02

Gore, P., and Metz, A. J. (2017). “First year experience programs, promoting successful student transition” in Encyclopedia of international higher education systems and institutions. eds. J. C. Shin and P. Teixeira (Netherlands: Springer), 1–6.

Greene, J. C. (2008). Is mixed methods social inquiry a distinctive methodology? J. Mixed Methods Res. 2, 7–22. doi: 10.1177/1558689807309969

Greene, J. C., Caracelli, V. J., and Graham, W. F. (1989). Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 11, 255–274. doi: 10.3102/01623737011003255

Halbesleben, J. R., and Wheeler, A. R. (2008). The relative roles of engagement and embeddedness in predicting job performance and intention to leave. Work Stress 22, 242–256. doi: 10.1080/02678370802383962

Herrmann, K. J., Troelsen, R., and Bager-Elsborg, A. (2015). Med tvivlen som følgesvend: En analyse af omfang af og kilder til studietvivl blandt studerende. Dansk Universitetspædagogisk Tidsskrift 10, 56–71. doi: 10.7146/dut.v10i19.20738

Hobfoll, S. E. (2011). “Conservation of resources theory: its implication for stress, health, and resilience” in The Oxford handbook of stress, health, and coping. ed. S. Folkman , vol. 127 (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 147.

Holmegaard, H. T., Madsen, L. M., and Ulriksen, L. (2014). A journey of negotiation and belonging: understanding students’ transitions to science and engineering in higher education. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 9, 755–786. doi: 10.1007/s11422-013-9542-3

Hovdhaugen, E. (2009). Transfer and dropout: different forms of student departure in Norway. Stud. High. Educ. 34, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/03075070802457009

Hovdhaugen, E., and Aamodt, P. O. (2009). Learning environment: relevant or not to students' decision to leave university? Qual. High. Educ. 15, 177–189. doi: 10.1080/13538320902995808

Lykkegaard, E., and Ulriksen, L. (2019). In and out of the STEM pipeline–a longitudinal study of a misleading metaphor. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 41, 1600–1625. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2019.1622054

Qvortrup, A., and Lykkegaard, E. (2024a) The malleability of higher education study environment factors and their influence on humanities students’ dropout – validating an instrument, Education Sciences. (in review).

Qvortrup, A., and Lykkegaard, E (2024b) Justifying methodologies in educational research: Epistemological paradigms as logics of justification and frames of inquiry. [in review].

Powers, T. E., and Watt, H. M. (2021). Understanding why apprentices consider dropping out: longitudinal prediction of apprentices’ workplace interest and anxiety. Empir. Res. Vocat. Educ. Train. 13:9. doi: 10.1186/s40461-020-00106-8

Roese, N. J., and Summerville, A. (2005). What we regret most… And why. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 31, 1273–1285. doi: 10.1177/0146167205274693

Sadler, P. M., Sonnert, G., Hazari, Z., and Tai, R. (2012). Stability and volatility of STEM career interest in high school: a gender study. Sci. Educ. 96, 411–427. doi: 10.1002/sce.21007

Sandler, M. E. (2000). Career decision-making self-efficacy, perceived stress, and an integrated model of student persistence: a structural model of finances, attitudes, behavior, and career development. Res. High. Educ. 41, 537–580. doi: 10.1023/A:1007032525530

Schönrock-Adema, J., Heijne-Penninga, M., Van Hell, E. A., and Cohen-Schotanus, J. (2009). Necessary steps in factor analysis: enhancing validation studies of educational instruments. The PHEEM applied to clerks as an example. Med. Teach. 31, e226–e232. doi: 10.1080/01421590802516756

St. John, E. P., Paulsen, M. B., and Starkey, J. B. (1996). The nexus between college choice and persistence. Res. High. Educ. 37, 175–220. doi: 10.1007/BF01730115

Tierney, W. G. (1999). Models of minority college-going and retention: cultural integrity versus cultural suicide. J. Negro Educ. 68, 80–91. doi: 10.2307/2668211

Tinto, V. (1975). Dropout from higher education: a theoretical synthesis of recent research. Rev. Educ. Res. 45, 89–125. doi: 10.3102/00346543045001089

Tinto, V. (1997). Classrooms as communities: exploring the educational character of student persistence. J. High. Educ. 68, 599–623. doi: 10.1080/00221546.1997.11779003

Truta, C., Parv, L., and Topala, I. (2018). Academic engagement and intention to drop out: levers for sustainability in higher education. Sustain. For. 10:4637. doi: 10.3390/su10124637

Tuominen-Soini, H., Salmela-Aro, K., and Niemivirta, M. (2012). Achievement goal orientations and academic well-being across the transition to upper secondary education. Learn. Individ. Differ. 22, 290–305. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2012.01.002

Keywords: tertiary education, Tinto’s institutional departure model, dropout considerations, expectancies and experiences, mixed methods, longitudinal studies

Citation: Lykkegaard E and Qvortrup A (2024) Longitudinal mixed-methods analysis of tertiary students’ dropout considerations. Front. Educ. 9:1399714. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1399714

Edited by:

Judith Schoonenboom, University of Vienna, AustriaReviewed by:

Gail Augustine, Walden University, United StatesAugustin Kelava, University of Tübingen, Germany

Luise Heusel, University of Tübingen, Germany, in collaboration with reviewer AK

Copyright © 2024 Lykkegaard and Qvortrup. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eva Lykkegaard, ZXZhbEBzZHUuZGs=

Eva Lykkegaard

Eva Lykkegaard Ane Qvortrup

Ane Qvortrup