94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 25 July 2024

Sec. Mental Health and Wellbeing in Education

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1398937

This research aims to explore the acculturative stressors experienced by Chinese international students in the UK and investigates their views on intercultural mentoring programs offered at UK universities. To achieve these objectives, the study utilizes primarily qualitative data gathered from 12 semi-structured interviews, exploring Chinese international students’ wellbeing and their perceptions about intercultural mentoring programs. The findings indicate that the wellbeing of Chinese international students was influenced by a range of macro and micro acculturative stressors, including academic integration, language barriers, social integration, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Contrary to expectations, the study reveals that perceived cultural differences between China and the UK, as well as homesickness, were not the main sources of stress for Chinese international students. Regarding intercultural mentoring programs, this research finds that their introduction by UK universities represents a positive effort to enhance intercultural competence and overall wellbeing of international students. Nevertheless, the research has identified four main issues requiring consideration: mentor qualifications, limited mentor availability, effective mentor-mentee pairing, and ethical challenges.

As the trend of globalization and internationalization continues to advance, pursuing higher education abroad has become a sought-after experience among young adults, and universities, such as those in the UK, have become more diverse than ever before (Gill, 2007; Phua et al., 2017). Over the past decade, the number of Chinese international students in the UK keeps rising, from 89,540 in 2014 to 120,385 in 2018 (Higher Education Statistics Agency, 2020). However, studying abroad is a process fraught with many challenges and adversities, and the mental health and wellbeing issues experienced by international students, including those from China, have attracted attention (Alharbi and Smith, 2019). According to Shadowen et al. (2019), for example, common mental symptoms caused by acculturation problems include anxiety, depression, alienation, fear of making mistakes, as well as high levels of anger. Frustration and feelings of powerlessness, often lead to intense “anger” among overseas students (Lee and Rice, 2007, p. 400). The outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic early in 2020 further worsened the plight (Holmes et al., 2020).

Mental health and wellbeing are interconnected yet complex concepts. Wellbeing is often defined as “the combination of feeling good and functioning well” (Ruggeri et al., 2020, p. 1). Mentoring is considered a valuable strategy for assisting inexperienced students in addressing health and wellbeing problems, and fostering holistic development (Hobson and Malderez, 2013). Intercultural mentoring, also known as international peer-mentoring, refers to mentoring programs implemented by universities to help international students establish a sense of belonging in an unfamiliar social and cultural environment (Caligiuri et al., 2020). However, empirical evidence on how intercultural mentoring impacts international students’ wellbeing remains limited. To explore the potential of intercultural mentoring, the research first examines major mental stressors that can influence Chinese international students’ health and wellbeing in the UK. It then explores how Chinese international students in the UK perceive intercultural mentoring as a stress coping strategy, especially after the outbreak of COVID-19.

In early studies, acculturation has been conceptualized as a unidirectional process that sojourners, mostly immigrants, go through to assimilate into the host culture (Berry, 1997). This unidimensional model treats acculturation as an attempt to relinquish one’s heritage culture (Cao et al., 2017). However, as international education gained popularity, acculturation has been regarded as a bidimensional or even multidimensional concept (Searle and Ward, 1990). For example, Berry (2005, p. 698) defined it as “the dual process of cultural and psychological change that takes place as a result of contact between two or more cultural groups and their individual members.” Acculturation, like a coin with two sides, can potentially drive personal growth (Berry, 2005). However, lacking systematic support, international students sojourning in an unfamiliar sociocultural and educational environment are often frustrated by stressful life events and suffer from mental health problems (Zhang and Goodson, 2011).

The consequences of acculturation include psychological outcomes and behavioral adaptation (e.g., Searle and Ward, 1990; Schwartz et al., 2010; Berry, 2017). A sojourner’s psychological outcomes, known as internal adjustment, contrast with behavioral adaptation, which is external. Behavioral adaptation shows how competent a sojourner is in managing their social life in the host culture. Not all individuals or groups go through acculturation at the same pace or in the same way. Individuals vary in their approaches to adjusting to the host culture (Berry, 1980). Further, according to Berry (2006), personal characteristics, acculturation attitudes, coping resources and strategies are all key variables that could influence one’s internal adjustment. Sojourners’ external adjustment is closely associated with their degree of contact, cultural knowledge, and positive inter-group attitudes, and all these factors are facilitated through social learning mechanisms, as Berry (2006) argues.

The factors that can lead to varying levels of acculturative stress are termed acculturative stressors (Pan et al., 2007). Upon a review of the literature related to acculturative stressors (e.g., Spencer-Oatey and Xiong, 2006; Pan et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2012; Cao et al., 2016), this research has identified five stressors encountered by Chinese international students during their acculturation process, namely, perceived cultural distance, social integration, academic integration, language barriers, and homesickness. Additionally, this study identifies the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) as an emerging acculturative stressor, of which the impact on the health and wellbeing of international students remains poorly understood, despite extensive research on the general population (e.g., Spatafora et al., 2022). Here arises the first research question of the study: How do the main acculturative stressors impede Chinese international students’ health and wellbeing throughout their intercultural adaptation in the UK? Below we provide an overview of the impacts the key stressors have on the health and wellbeing of international students, and Chinese international students in particular.

Perceived cultural distance refers to the perceived differences between two cultures in terms of social norms, beliefs, religions, values, and habits (Geeraert and Demoulin, 2013). Hofstede’s model assesses cultural distance across six dimensions: power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism and collectivism, masculinity and femininity, long-term orientation and short-term normative orientation, as well as indulgence and restraint (Hofstede, 2011). Empirical evidence suggests that greater cultural distance increases difficulties for sojourners in the host culture (Galchenko and Van de Vijver, 2007). The individualism-collectivism dimension, frequently cited in studies of East-West cultural differences, is among the most researched (Yeh and Inose, 2003; Li et al., 2018). For instance, in collectivist societies like China, individuals prioritize group goals, values, and benefits over personal needs, while in Western societies where individualism dominates, personal uniqueness is emphasized (Matsumoto et al., 2008). The conflict between cultural values that sojourners experience has been found to be a key challenge to their mental health and wellbeing (Berry, 1997).

Social integration refers to how well intercultural travelers develop and maintain interpersonal relations in the host culture (Galchenko and Van de Vijver, 2007). Because international students are new to the host society, they have reduced ability to navigate through the local life. Unfamiliarity often prevents international students from getting socially integrated within the receiving community (Newsome and Cooper, 2016). International students have three distinct social networks: co-national network, multi-national network, and host-national network, but the first network is the most common and the most well-maintained (Schartner, 2015). This phenomenon, known as “developing close-knit compatriot social network,” has been well-documented by accumulating research (Cao et al., 2016).

Academic integration is defined as the degree to which international students adapt to the educational environment of their host country (Cao et al., 2016). Demanding coursework and high academic expectations frequently result in an overwhelming workload that exacerbates academic pressure and poses challenges for Chinese international students to manage (Cao et al., 2021). Intense academic pressure can put international students under a constant emotional strain, thus making them live a stressful and unbalanced life (Yamada et al., 2014). Many researchers, such as Barron (2006), have observed that the teaching style preferences of many international students are different. Yan and Berliner (2009) reported that Chinese international students have verbal passiveness and habitual silence in class. Wu (2015) also found it was difficult for Chinese students to make themselves adjusted to an educational environment that emphasizes independent learning, critical thinking, and less supervision.

Language barriers refer to the language proficiency and communication problems that prevent sojourners from achieving intercultural adaptation (Masgoret and Ward, 2006). Andrade (2006) found that language incompetence has become a primary factor that prevents international students from making sociocultural and academic adjustment. Spencer-Oatey and Xiong (2006) observed that Chinese international students in the UK struggle to comprehend English jokes and humor. Elliot et al. (2016) highlighted that language barriers not only affect academic discourse but also impact social interactions, thereby restricting student engagement in diverse settings. Wang et al. (2012) discovered that Chinese students face greater language problems than their EU counterparts in intercultural adaptation, attributing this disparity to the communicative focus of EU education versus the examination-oriented approach in China.

Homesickness can be defined as a psychological reaction to the absence of attachment objects and the separation from home (Stroebe et al., 2015). When living far away from their homeland, international students often feel emotionally isolated and distressed by a feeling of homesickness. Compared to other acculturative stressors (which are primarily sociocultural factors), homesickness is a negative mental status that directly influences sojourners’ wellbeing and psychological health. Homesickness can bring many other negative feelings to sojourners, such as depression, loneliness, anxiety, sadness, alienation, and hopelessness (Constantine et al., 2005; Ward et al., 2020).

After the strike of COVID-19, university students in the UK had to be kept out of campus and received temporary “home-schooling” in an attempt to mitigate the spread of this full-blown pandemic. When international students were kept isolated from campus life, they would feel heightened boredom and loneliness (Ma and Miller, 2020; Watermeyer et al., 2021). Some students managed to return to their home countries, while others were trapped in their accommodation, unable to move freely due to the lockdown restrictions, grappling with isolation and uncertainty (Lai et al., 2020; McGivern and Shepherd, 2022). Moreover, Chinese international students’ anxiety and stress also came from epidemic-related rumours and prejudice (Ma and Miller, 2020), further compounded by the social stigma associated with face mask wearing (Xiao et al., 2020). The rumors associated with COVID-19 virus have seriously damaged Chinese international students’ self-esteem and jeopardized their mental health (Wilson, 2020).

Mentoring is a transactional relationship developed to facilitate learning (Jones and Brown, 2011). In this process, an experienced mentor serves as a facilitator of knowledge, assisting mentees in bridging the gap between their current reality and aspirations, fostering self-improvement and development (Hobson and Malderez, 2013). In the higher education sector of the U.K., several universities employ mentoring as a strategy to support the transition of newcomers (see, e.g., Hargreaves, 2010; Gannon and Maher, 2012; Collings et al., 2014, 2015).

Empirical studies shows that mentoring programs significantly enhance students’ self-esteem, boost their satisfaction and commitment to university, as well as promote greater civic engagement (Sanchez et al., 2006; Weiler et al., 2013). Mentoring manifests in diverse forms across educational settings. Although one-on-one mentoring proved to be the most effective way for universities to improve students’ intercultural competence, universities are faced with scalability and cost challenges because competent faculty members lack the time to offer one-on-one mentoring to students. Peer mentoring is a viable, cost-effective and sustainable alternative available to educational institutions (Dangeni et al., 2023). Peer mentoring refers to the programs in which senior students (mentors) are paired with new students (mentees) to foster the rapid acquisition of specific skills by the newcomers (Vickers et al., 2017). On campus, mentors may volunteer their services, but many are compensated with rewards, financial remuneration, academic credit, or an honorarium (O’Brien et al., 2012; Weiler et al., 2013). However, as mentioned above, intercultural mentoring has received limited scholarly attention. Therefore, it is time to investigate how helpful mentoring programs are perceived to be in helping international students alleviate their acculturative stress and adjust to university life in the host country. The second research question of the study is therefore: How do Chinese international students view intercultural mentoring programs (IMP) as a stress coping strategy?

Thomas (2017) posited researchers who follow the paradigm of interpretivism consider that social phenomena can be understood and interpreted through investigating the thoughts, ideas, perceptions, feelings, and actions of individuals within a certain context. Although most studies investigating acculturative stress experienced by international students are quantitative and they make valuable contributions, qualitative research is vital to understand the how questions and the experiences and perceptions of the individuals interviewed. Specifically, this qualitative case studies (Crowel et al., 2011) explores in depth the complex issues of acculturative stress experienced by Chinese international students in the UK. Using semi-structured interviews and drawings of emotions, this research design is well-suited to capture detailed student narratives and contextual nuances. It offers insights into the complex ways in which the students experience and manage acculturative stress, while revealing the rich, layered interactions among stressors, coping strategies, and contextual factors that quantitative methods might overlook.

This case study (Yin, 2009) focuses on Chinese international students in a university located in the South of England in the UK. Due to the constraints imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic and related social distancing measures, a snowball sampling method based on the following pre-defined criteria was employed. First, the research targeted Chinese international postgraduate students in a one-year program at the case university, where the condensed study period heightens the importance of peer mentoring in contrast to the longer periods typical of undergraduate and doctoral studies. Second, the candidates were those without long-term (over six months) overseas living or studying experience prior to their postgraduate enrolment. Third, since male and female students may perceive stress in different ways and use different preferred methods and strategies to deal with stress (Bonneville-Roussy et al., 2017), efforts were made in this research to balance the number of male and female participants. Last, considering that students of different majors may have different adaptation challenges and strategies (May and Casazza, 2012), participants were equally recruited from three major disciplines: Business, Engineering and Life Sciences, and Social Sciences and Humanities. A total of 12 Chinese international students were recruited as interviewees, with four students in each group. The demographic features of interviewees are presented in Table 1.

The primary data collection method employed in this study was semi-structured interviewing, a widely used technique in qualitative research designs. Each interview commenced with a brief introduction to reiterate the research background and significance. The interviews were conducted following a pre-designed schedule, which included questions regarding participants’ demographic information, wellbeing status, acculturative stressors, and perceptions on intercultural peer mentoring.

In addition to interviews, emotions drawing was used to explore the emotional fluctuations experienced by Chinese international students. In this method, participants were asked to draw an emotional line representing their emotional fluctuations over a specified period. This drawing method has previously been applied in studies with elementary or kindergarten children to capture emotional flows (Harrison et al., 2007). Compared to traditional methods like numerical scales or verbal labels, emotions drawing enables participants to freely express their feelings at each stage without the constraints of numbers or specific words. Therefore, researchers such as Kearney and Hyle (2004) and Bagnoli (2009) acknowledged drawings can better capture participants’ emotions and experiences than the language itself. However, few studies in the field of acculturation research have employed this approach. During the interviews, 12 Chinese international students were invited to draw emotional timelines. This provided a straightforward way to understand when participants felt emotionally “UP” or “DOWN.” Additionally, after each interview, the participants were encouraged to draw one picture to show which stressor influenced them the most. In total, six such drawings were collected and are presented in the next chapter.

The collected data were processed and analyses via thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006), with the assistance of NVivo. Thematic analysis, as Thomas (2017) described, is a commonly used interview data analysis strategy to identify recurring themes within a dataset. The tape-recorded interviews were transcribed and subsequently translated into English. A series of themes were developed to represent acculturative stressors, which are presented in Table 2.

To further enrich the understanding gained from the interview data, the drawings provided by participants were analyzed. Each drawing was examined alongside its corresponding interview transcript, facilitating the identification of key stressors illustrated visually and their connections to the themes identified from the verbal data. Moreover, analysis of the fluctuations in the participants’ timelines revealed their emotional variations during the first 10 months after arriving in the UK. Pronounced changes were indicative of intense cultural shock, and sharp deviations coinciding with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic underscored its profound impact on the interviewees’ emotional wellbeing and overall experiences.

Conducted under strict adherence to British Educational Research Association (2018) guidelines, this study received ethical approval from the case university’s ethics review board (Ethics number: M1920-142), ensuring compliance with high ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all participants through detailed information sheets and consent forms, which fully briefed them on the research’s aims, methods, and their rights, including the right to withdraw at any time without repercussions (Cohen et al., 2018). To safeguard privacy and confidentiality, measures such as data encryption and anonymization were implemented (Bryman, 2016). As an insider researcher, the first author maintained a reflexive approach throughout the study, actively interrogating their own biases, seeking diverse perspectives, and working closely with the supervisor to ensure the ethical integrity and trustworthiness of the research (Dwyer and Buckle, 2009). Given the specific challenges presented by the COVID-19 pandemic, detailed risk assessments were carried out to identify and mitigate any potential harm to the participants often viewed as a vulnerable group. This ensures that the research respects and protects their wellbeing at all stages.

Culture shock is one of the main stressors that influences the psychological wellbeing of international students during cross-cultural transitions (Zhou et al., 2008; Smith and Khawaja, 2011). As shown by the emotional timelines drawn by interviewed Chinese international students, five out of 12 interviewees experienced a period of wellbeing decline after arriving at their university, as indicated by a sharp downward trend. Four interviewees experienced significant wellbeing declines following a short period of initial excitement, exhibiting an up-down trend. These emotional fluctuations are presented in Figure 1.

Participant 12 explained it as follows:

“… it was still hard for me to adapt to the host culture after I arrived. However, I gradually realised that it didn’t really matter whether I could follow the sociocultural norms here … That’s the reason why I felt better after a period of depression.”

Hofstede’s model examines cultural distance across six dimensions. In this study, interviewees were asked to describe their views on the cultural differences between Chinese culture and the host (British) culture, as summarized in Table 3.

The answers given by the interviewees supported the cultural distance framework, particularly in terms of individualism–collectivism and power distance dimensions. Pronounced cultural differences were perceived by Chinese international students, who reported that these differences notably contributed to acculturative stress, particularly upon their arrival. Conflicts between individualistic and collectivistic values were particularly stark between Chinese and British cultures. Additionally, differences in power distance contributed to the Chinese students feeling uneasy in British society (see Figure 2). Adjustment issues became evident as the students tried to settle in, with some experiencing psychological health problems, including diminished feelings of social belonging, increased anxiety, and depressive symptoms. Despite considerable differences in power distance, individualism, long-term orientation, and indulgence between Chinese and British cultures, Chinese international students typically adapted to the host culture within a short period. Overall, while perceived cultural distance serves as an acculturative stressor, it does not significantly affect the wellbeing of international students over time.

To investigate how well the interviewees integrated into British society, this research categorized the theme of social integration into three subthemes: discrimination, orientation, and social network expansion.

International students, often from ethnic minority groups, seek higher education in unfamiliar cultural settings. Discrimination based on ethnicity and race is common in intercultural interactions. Chinese international students, as a minority group in the UK, are found to be influenced by discrimination. The discrimination experienced by Chinese international students originates from two main sources: language barriers and the COVID-19 pandemic, both significant acculturative stressors. The most common discriminatory behaviors include avoidance and ignoring. Physical assaults and verbal abuses are less frequently reported. Exposed to direct or indirect discrimination, Chinese international students regularly suffer from adverse mental health outcomes, including low self-esteem, depression, and anxiety. Participant 1 described a scenario in which she and another Chinese student faced discrimination during a peer evaluation:

“There were five peer partners in our group, but the boy refused to give feedback to my friend and me, even though we insisted on asking him to do so.”

None of the 12 interviewees perceived OR as an acculturative stressor. However, the findings revealed that Chinese international students rarely received social support from host country nationals. Instead, they predominantly depended on their co-national network to access essential information (e.g., shopping and dining locations). For instance, Participant 9 stated that ‘developing a close-knit compatriot social network’ facilitated her rapid adaptation to local life:

“I joined many group chats via different social networking apps, such as WeChat. Whenever I want to get some information, I can ask other Chinese international students for help.”

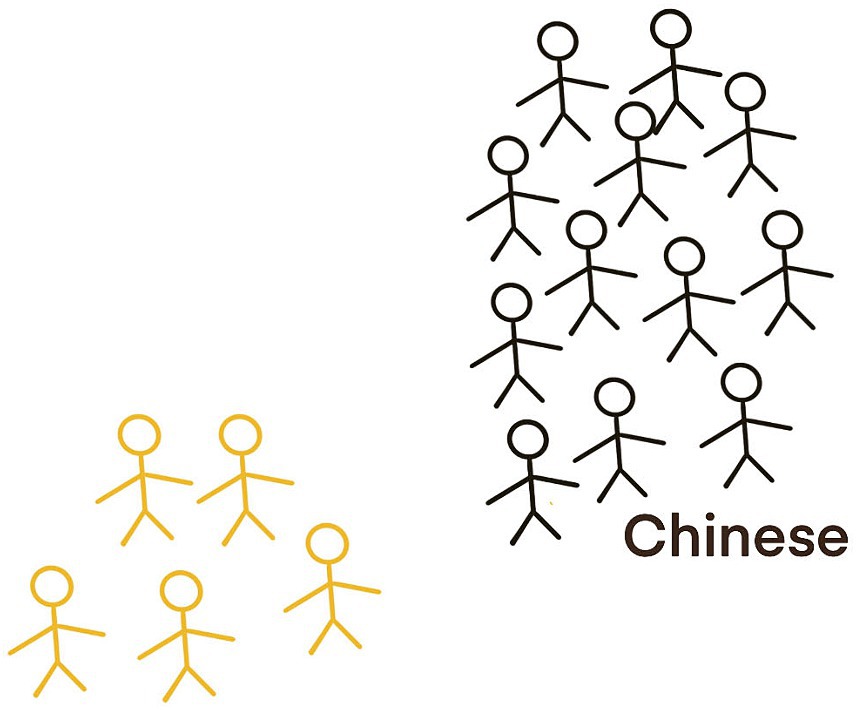

As shown in Table 4, when asked “How do you feel socializing with local people?”, the interviewees commented that it is extremely difficult for most Chinese international students to develop and maintain social connectedness and interaction with host country nationals. One participant drew a picture to illustrate the phenomenon of “developing a close-knit compatriot social network” among Chinese international students in the UK (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. A picture drawn by participant 9 (showing the phenomenon of “developing a close-knit compatriot social network” among Chinese international students in the UK).

However, the research found that the interviewed Chinese international students did not consider their inability to maintain close relationships with host country nationals as a primary stressor. This result contradicts previous empirical studies, which have demonstrated that the social support international students receive from locals is a key predictor of their psychological and sociocultural adjustment (Yeh and Inose, 2003; Zhang and Goodson, 2011).

As illustrated in Table 5, all 12 interviewees acknowledged that academic integration as a main source of stress. Under the theme of academic integration, there are a list of different codes designed to represent different sub-categories of stressors, including teaching styles, high expectations, heavy workloads, and writing obstacles.

The differences in teaching styles between British and Chinese universities are considered to be a major obstacle that may impede Chinese international students from achieving academic adaptation in their postgraduate studies. The current study found that student-centered teaching methods, such as interactive teaching, cooperation-based teaching, inquiry-based teaching, and discovery learning, are commonly utilized in the university being researched. By contrast, teacher-centered lecturing is the main source of knowledge at most Chinese universities. Chinese students accustomed to traditional teacher-centered teaching styles may find it challenging to adapt to postgraduate programs that prioritize self-directed learning and the cultivation of individual initiative. As participant 7 noted:

“At my undergraduate university (in China), we seldom challenged our teachers. They give and we just took. We did not have too many group projects then, so all we needed to do was listen to the lecturer.”

Failing to meet their high self-expectations is another source of stress for many Chinese international students. All the 12 research participants were required to self-assess to what extent they were satisfied with their academic performance (i.e., to what extent they had achieved their academic expectations) in this research. The participants’ satisfaction with their academic performance was measured using a 5-point Likert scale, with options ranging from “extremely dissatisfied” (1) to “extremely satisfied” (5). The mean score of the 12 self-assessments was 3.00, suggesting that the interviewees, on average, held a moderate level of satisfaction regarding their academic achievements up to the point of the interview. Table 5 presents the specific reasons and comments given by the interviewees.

In this study, seven out of 12 interviewees mentioned that heavy academic workloads, including team projects, pre-readings, quizzes, or online forum discussions, are a significant source of stress that constantly threatened their mental health. Participant 12 explained that:

“During the lockdown period, we had to stay at home and start distance learning. We had so much group work, and you know it is so time-consuming to do group work online. I remember I used to spend more than 2 hours each day on video calls. It was physically and mentally exhausting.”

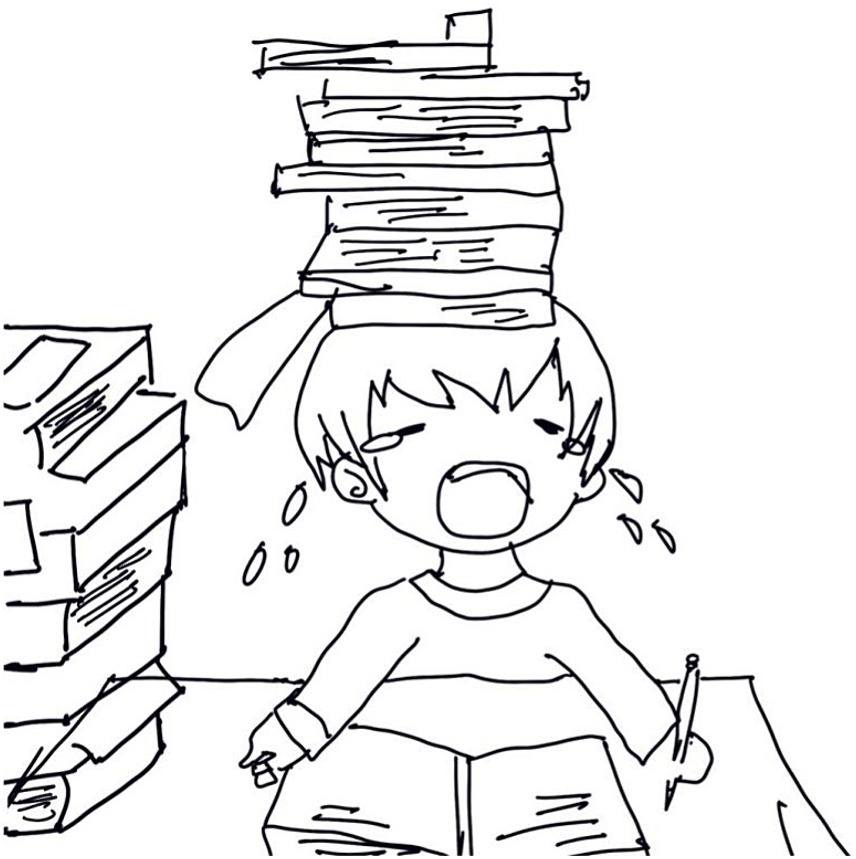

Spending a lot of time on pre-readings is also a common problem for Chinese international students. One participant drew a picture to show the heavy workloads of Chinese international students in the UK (see Figure 4). Participants 1, 3 and 6 all explained this issue in great detail. For example, Participant 6 mentioned:

Figure 4. A picture drawn by participant 4 (showing the heavy workloads of Chinese international students in the UK).

“I have to read relevant materials in Chinese before I start learning something… However, reading in English is such a struggle for me. I prefer to use Google Translator to do some translations… but, you know, I still need to read the English version sometimes because translations are not always reliable. It takes me so much time!”

Many Chinese students recognize academic writing as a substantial stressor, a finding consistent with previous studies on the non-native challenges encountered by English as a Foreign Language (EFL) students. For example, EFL students had difficulties in structuring because of their insufficient genre-specific writing skills (Bitchener and Basturkmen, 2006; Singh, 2015; Komba, 2016). Another prevalent non-native challenge that EFL students often face is the use of appropriate academic style (Bakhou and Bouhania, 2020). In the current research, one of the most significant academic writing challenges that most Chinese international students face is the lack of critical thinking. Three interviewees acknowledged this issue:

“The teachers always say, ‘Don’t be too descriptive’, but I just don’t know how to be critical in many cases.” (Participant 3)

“The most serious problem is I have no idea how to be critical in writing. I don't know what is expected of me.” (Participant 9)

“We were not taught to be critical at Chinese universities.” (Participant 10)

Although the issue ‘How to write academically in English’ has been identified as a stressor, four interviewees mentioned that the pre-sessional program they had undertaken helped them overcome this trouble.

“I appreciate that I participated in the pre-sessional programs. It was really helpful because the courses not only helped us improve language proficiency but also taught us how to write an academic paper!” (Participant 5)

Perceived language discrimination is a source of stress for Chinese international students, as they felt ignored and disrespected when talking in English or found language problems challenging due to language barriers. As indicated in section 5.1.2 and reported by five interviewees:

“I found the students from the UK or other European countries tend to avoid forming groups with Chinese students. I guess they might think communication is a problem.” (Participant 10)

“I don’t like my accent, and I am afraid they will laugh at me.” (Participant 4)

“Our teachers don’t speak too fast in class, but other people (off campus) don’t really care about whether you can understand or not.” (Participant 5)

Language proficiency is not synonymous with communication competence (Masgoret and Ward, 2006). Even though an international student speaks English fluently, it does not necessarily mean they are linguistically competent in real communication. A typical problem is that Chinese international students may not understand the meaning between the lines due to cultural differences. As Participant 5 observed:

“I can understand what they say but can’t understand what they mean. Whenever I had communication problems with locals, I would feel depressed, anxious and inferior.”

Lastly, language incompetence, as a persistent stressor that cannot be resolved in a short period, exerts a lasting negative influence on the wellbeing of Chinese international students.

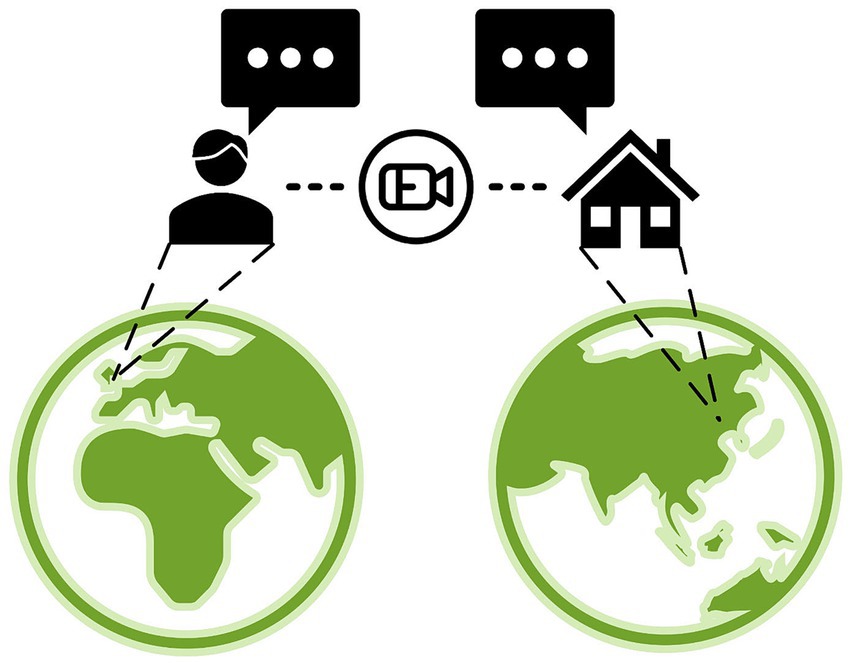

Interestingly, 11 out of the 12 interviewees in this study reported that their physical and psychological wellbeing was not influenced by homesickness, thus they did not regard homesickness as a significant acculturative stressor. Their responses to the question ‘How do you feel about being far from home?’ are summarized in Table 6. Furthermore, Participant 11 used a picture to show how ICTs helped international students communicate with their families (see Figure 5), just as the high school students benefited from the use of mobile phones in China (Xiao, 2020).

Figure 5. A picture drawn by participant 11 (showing how ICTs helped international students communicate with their families).

This contradicts the finding of Thurber and Walton (2012) who claimed that international students could be mentally influenced by homesickness. This was mainly because the interviewees had frequent social interactions with their home-country networks via social networking websites or apps, which is considered an effective way for international students to deal with homesickness (Pang, 2018). In fact, although homesickness is undoubtedly a negative psychological state (Stroebe et al., 2016), it does not necessarily mean it is a source of acculturative stress, i.e., acculturative stressor. Stroebe et al. (2015) explained that homesickness, in its mild form, can help sojourners develop their coping skills and motivate them to maintain relationships with significant others. Only when sojourners suffer from severe or intense homesickness can they feel the negative mental and physical consequences caused by this painful and debilitating emotion (Thurber and Walton, 2012; Billedo et al., 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic first broke out in China at the beginning of 2020. Extant research literature reports that this unprecedented public health crisis has exerted a significant negative influence on the wellbeing of Chinese international students. The impact of COVID-19 on their wellbeing is evident in the emotional lines they have drawn (see Figure 6), which show a dramatic decline after the outbreak. Three main codes were constructed to represent the primary sources of stress: social isolation, crisis uncertainty, and virus-related discrimination.

Over the past several months, due to the outbreak of the virus and the subsequent social distancing rules, university students in the UK were required to leave campus and engaged in temporary “online learning” in an attempt to mitigate the spread of this full-blown pandemic. The resulting social isolation meant that some Chinese international students lacked face-to-face interactions with their friends and had limited opportunities for entertainment activities, leading to feelings of loneliness and depression. Participant 3 mentioned:

“COVID-19 influenced me a lot. Had everything been well (no pandemic), I could have made more friends here, and had much fun with them, like going travelling and participating in more interesting club activities. But now we can do nothing.”

Because of the uncertainty surrounding the crisis, many Chinese international students decided to return home to continue their studies online. However, under China’s latest COVID-19 prevention and control policies, all Chinese airlines were required to reduce the number of international flights. Facing this situation, many students had no choice but to abandon their plans, due to the insufficient number of available flights. This problem further exacerbated the anxiety among international students, as explained by Participant 2:

“I want to go back home, but I just couldn’t. I cannot afford the expensive flight tickets. Even though I had money, it is so difficult to book a flight now.”

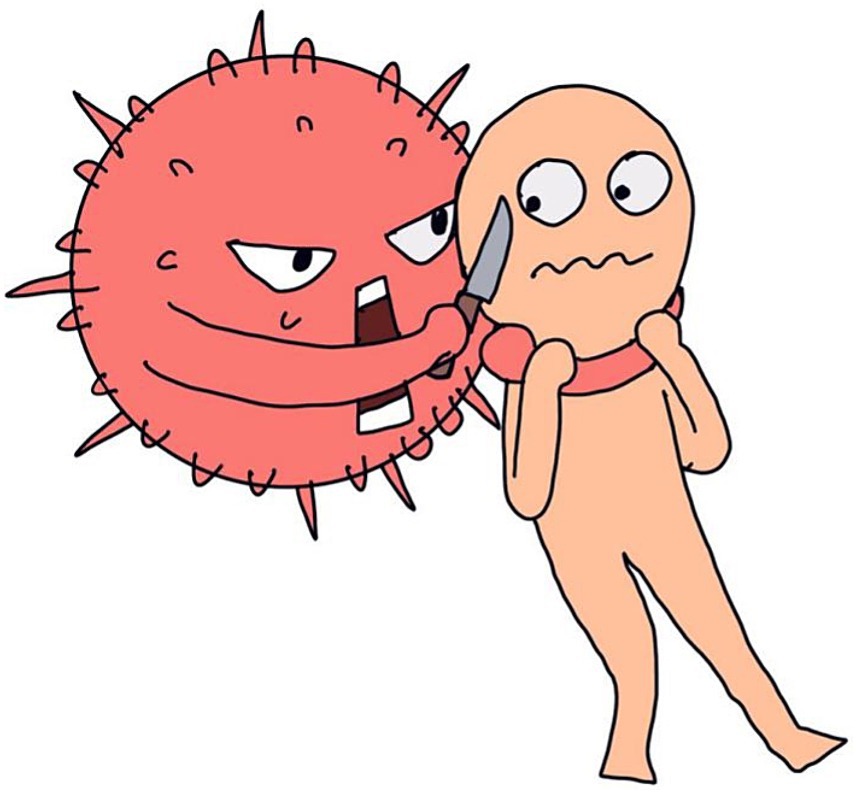

Under such circumstances, most Chinese international students had to remain in the UK and adapt to the uncertainty caused by the crisis. One participant expressed his concerns and fear of the pandemic-related uncertainty through drawing (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. A picture drawn by participant 6 (showing Chinese international students’ fear of pandemic uncertainty).

“I dare not leave my apartment. If I am affected, what should I do? I don’t want to die here (with a joking tone).”

“At first, when I saw the number of affected people increase dramatically in China, I felt worried about my parents. Now, when I see British people not wearing face masks, I’m worried about myself!”

During the pandemic, crisis uncertainty posed a serious threat to the wellbeing of Chinese international students, proving to be one of the main stressors.

As indicated in section 5.1.2, Chinese international students have been subjected to serious virus-related discrimination at the early stage of the pandemic, because China was blamed for the COVID-19 outbreak. Moreover, the cultural conflicts on the use of face masks further intensified Chinese international students’ anxiety. They found that wearing face masks had become a stigmatized act in British society, which put them under considerable pressure. Participant 8 explained the cultural conflict in this way:

“My roommate told me that many British people considered only the affected should wear masks. It is an abnormal behavior for healthy people to wear face masks. If they saw you wearing a mask, they might treat you like a patient. This sounds strange to me.”

Consequently, seven students reported experiencing discrimination when wearing masks in public. The interpretation of stigma associated with wearing face masks among Chinese international students is illustrated by one of the interviewees (see Figure 8).

In this research, all 12 interviewees acknowledged that it is a positive attempt for UK universities to help international students improve their intercultural competence and maintain mental health via IMP. The reasons why the interviewees supported such a program are twofold:

On the one hand, there is no “one size fits all” approach that can be effective with all international students. Compared to some formal learning approaches, mentoring can be more effective because of its flexibility. To achieve better results, mentors can draw on different sources of information so that their support to mentees will be more customized and effective. On the other hand, mentoring often constitutes a reciprocal and potentially life-altering relationship that not only helps mentees out of trouble but also inspires mutual growth and development. Mentees can reduce the negative impact of acculturative stressors with the help of their mentors, while mentors can gain diverse experiences and achieve self-improvements through organizing mentoring activities.

During this research, when asked whether they would like to join the program and become a mentor, all 12 interviewees gave a positive answer:

“This mentoring experience can help me enhance my communication competence and hone my interpersonal skills.” (Participant 8)

“I would say yes because I think this experience will bring me a sense of achievement.” (Participant 3)

“Becoming a mentor allows me to make more friends here.” (Participant 6)

Based on these findings, the research concludes that establishing an intercultural mentoring program would be a rational and positive endeavor for UK universities.

Although all interviewees supported the proposal to establish the IMP, they identified several potential challenges that could emerge following the program’s implementation. To address these issues, corresponding suggestions were provided as each problem was identified (Table 7).

In terms of the research design, this study has the following three limitations: First, the study’s data were solely collected from a single university, located in a small Southern England city, the university likely presents a social environment that is distinct from those in other cities. Similarly, universities may differ in their expectations of Chinese international students. Consequently, while the findings provide deep insights into the context of a single university, which is the focus of a case study design, they may not be directly applicable to other institutions with different environmental or academic dynamics. Future research would enhance the generalizability of such findings by including a more diverse range of university settings. Second, it was likely that the research findings were influenced by insider bias. Although the researcher, as an insider, has a good understanding of Chinese international students’ acculturative experience and can thus provide some privileged insights into the investigated topic, the “insider bias” is still considered as a research limitation, although we made transparent such potential bias throughout the research. Third, the use of a Likert scale to assess self-reported academic satisfaction among Chinese international students presents a methodological limitation. The cultural inclination toward modesty may have influenced participants’ responses, leading to scores that do not accurately reflect their true satisfaction levels. For instance, a score of “3” could signify high satisfaction for some students but dissatisfaction for others. This variance highlights the complexity of interpreting self-reported data. Future research should incorporate mixed methods to better capture and understand the complex experiences of these students.

This research collected primarily qualitative data from semi-structured interviews and emotions drawing to explore how Chinese international students from a single UK university managed to overcome acculturative stress that they had experienced after arriving in the host country, as well as how they perceived the potential of intercultural peer mentoring programs at UK universities. Findings indicate that academic integration, language barriers, social integration, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic constitute the primary macro stressors. Contrary to expectations, perceived cultural differences and homesickness were not identified as significant stressors. Despite great differences between Chinese and British cultures across various dimensions, the research found that Chinese international students were able to adapt to the host culture within a relatively short period of time. Moreover, the rapid development of information and communication technologies (ICTs) has facilitated Chinese international students’ maintenance of social networks, thereby mitigating the psychological distress associated with mild homesickness.

This study also examined how the students perceived intercultural mentoring programs at UK universities. Introducing such programs may constitute an effective approach to enhancing the intercultural competence and wellbeing of international students. However, this research has identified four primary issues that warrant careful consideration: (1) mentor qualifications, (2) limited mentor availability, (3) effective mentor-mentee pairing, and (4) ethical challenges. To address these identified issues, the research provides a series of recommendations. First, to enhance the quality of mentoring activities, it is recommended that universities establish a quality control system. Second, to increase mentor availability, the research suggests that universities should offer incentives to attract more mentors and explore diverse mentoring channels. Third, to promote effective mentor-mentee pairing, the research proposes the development of a structured mentor-mentee pairing system. Finally, to mitigate potential ethical challenges, it is advised that mentors and mentees sign a contract outlining clear ground rules before commencing mentoring activities.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Research Ethics and Governance, University of Exeter. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

XJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZX: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors would like to thank Professor Lindsay Hetherington at the School of Education, University of Exeter, for her constructive feedback on earlier drafts of the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1398937/full#supplementary-material

Alharbi, E., and Smith, A. (2019). Studying-away strategies: a three-wave longitudinal study of the wellbeing of international students in the United Kingdom. Eur. Educ. Res. 2, 59–77. doi: 10.31757/euer.215

Andrade, M. S. (2006). International students in English-speaking universities: adjustment factors. J. Res. Int. Educ. 5, 131–154. doi: 10.1177/1475240906065589

Bagnoli, A. (2009). Beyond the standard interview: the use of graphic elicitation and arts-based methods. Qual. Res. 9, 547–570. doi: 10.1177/1468794109343625

Bakhou, B., and Bouhania, B. (2020). A qualitative inquiry into the difficulties experienced by Algerian EFL master students in thesis writing: ‘language is not the only problem’. Arab World English J. 11, 243–257. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3649316

Barron, P. (2006). Stormy outlook? Domestic students’ impressions of international students at an Australian university. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 6, 5–22. doi: 10.1300/J172v06n02_02

Berry, J. W. (1980). “Acculturation as varieties of adaptation,” in Acculturation: Theory, models and some new findings. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 9–25.

Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Appl. Psychol. 46, 5–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01087.x

Berry, J. W. (2005). Acculturation: living successfully in two cultures. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 29, 697–712. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.07.013

Berry, J. W. (2006). Stress perspectives on acculturation. The Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology 1, 43–56. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511489891.007

Berry, J. W. (2017). Theories and models of acculturation. The Oxford handbook of acculturation and health 10, 15–28. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190215217.013.2

Billedo, C. J., Kerkhof, P., and Finkenauer, C. (2020). More facebook, less homesick? Investigating the short-term and long-term reciprocal relations of interactions, homesickness, and adjustment among international students. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 75, 118–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2020.01.004

Bitchener, J., and Basturkmen, H. (2006). Perceptions of the difficulties of postgraduate L2 thesis students writing the discussion section. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 5, 4–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2005.10.002

Bonneville-Roussy, A., Evans, P., Verner-Filion, J., Vallerand, R. J., and Bouffard, T. (2017). Motivation and coping with the stress of assessment: gender differences in outcomes for university students. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 48, 28–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.08.003

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

British Educational Research Association (2018). Ethical guidelines for educational research. 4th edi Edn. London. Available at: https://www.bera.ac.uk/researchers-resources/publications/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018.

Brown, C. E. (2016). Ethical issues when graduate students act as mentors. Ethics Behav. 26, 688–702. doi: 10.1080/10508422.2016.1155151

Caligiuri, P., DuBois, C. L., Lundby, K., and Sinclair, E. A. (2020). Fostering international students’ sense of belonging and perceived social support through a semester-long experiential activity. Res. Comp. Int. Educ. 15, 357–370. doi: 10.1177/1745499920954311

Cao, C., Zhu, D. C., and Meng, Q. (2016). An exploratory study of inter-relationships of acculturative stressors among Chinese students from six European union (EU) countries. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 55, 8–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2016.08.003

Cao, C., Zhu, C., and Meng, Q. (2017). Predicting Chinese international students’ acculturation strategies from socio‐demographic variables and social ties. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 20, 85–96. doi: 10.1111/ajsp.12171

Cao, C., Zhu, C., and Meng, Q. (2021). Chinese international students’ coping strategies, social support resources in response to academic stressors: does heritage culture or host context matter? Curr. Psychol. 40, 242–252. doi: 10.1007/s12144-018-9929-0

Collings, R., Swanson, V., and Watkins, R. (2014). The impact of peer mentoring on levels of student wellbeing, integration and retention: a controlled comparative evaluation of residential students in UK higher education. High. Educ. 68, 927–942. doi: 10.1007/s10734-014-9752-y

Collings, R., Swanson, V., and Watkins, R. (2015). Peer mentoring during the transition to university: assessing the usage of a formal scheme within the UK. Stud. High. Educ. 41, 1995–2010. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2015.1007939

Constantine, M. G., Anderson, G. M., Berkel, L. A., Caldwell, L. D., and Utsey, S. O. (2005). Examining the cultural adjustment experiences of African international college students: a qualitative analysis. J. Couns. Psychol. 52, 57–66. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.1.57

Cope, P., Cuthbertson, P., and Stoddart, B. (2000). Situated learning in the practice placement. J. Adv. Nurs. 31, 850–856. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01343.x

Crowel, S., Cresswell, K., Robertson, A., Guro, H. U. B. Y., Avery, A., and Sheikh, A. (2011). The case study approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 11, 1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

Dangeni,, He, R., and Tripornchaisak, N. (2023). “Peer mentoring: A potential route to researcher independence,” in Developing researcher independence through the hidden curriculum. eds. D. L. Elliot, S. S. E. Bengtsen, and K. Guccione (Cham, Palgrave Macmillan: Springer International Publishing), 41–51.

Dwyer, S. C., and Buckle, J. L. (2009). The space between: on being an insider-outsider in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods 8, 54–63. doi: 10.1177/160940690900800105

Elliot, D. L., Reid, K., and Baumfield, V. (2016). Beyond the amusement, puzzlement and challenges: An enquiry into international students’ academic acculturation. Stud. High. Educ. 41, 2198–2217. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2015.1029903

Galchenko, I., and Van De Vijver, F. J. (2007). The role of perceived cultural distance in the acculturation of exchange students in Russia. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 31, 181–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2006.03.004

Gannon, J. M., and Maher, A. (2012). Developing tomorrow's talent: the case of an undergraduate mentoring programme. Educ. Train. 54, 440–455. doi: 10.1108/00400911211254244

Geeraert, N., and Demoulin, S. (2013). Acculturative stress or resilience? A longitudinal multilevel analysis of sojourners’ stress and self-esteem. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 44, 1241–1262. doi: 10.1177/0022022113478656

Gill, S. (2007). Overseas students’ intercultural adaptation as intercultural learning: a transformative framework. Compare 37, 167–183. doi: 10.1080/03057920601165512

Gray, M. A., and Smith, L. N. (2000). The qualities of an effective mentor from the student nurse’s perspective: findings from a longitudinal qualitative study. J. Adv. Nurs. 32, 1542–1549. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01606.x

Hargreaves, E. (2010). Knowledge construction and personal relationship: insights about a UK University mentoring and coaching service. Mentor. Tutor. 18, 107–120. doi: 10.1080/13611261003678861

Harrison, L. J., Clarke, L., and Ungerer, J. A. (2007). Children's drawings provide a new perspective on teacher–child relationship quality and school adjustment. Early Child. Res. Q. 22, 55–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2006.10.003

Higher Education Statistics Agency (2020) Where do HE students come from?. Higher Education Statistics Agency. Available at: https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/students/where-from (Accessed June 9, 2020).

Hobson, A. J., and Malderez, A. (2013). Judgementoring and other threats to realizing the potential of school-based mentoring in teacher education. Int. J. Mentor. Coach. Educ. 2, 89–108. doi: 10.1108/IJMCE-03-2013-0019

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture. 2. doi: 10.9707/2307-0919.1014

Holmes, E. A., O'Connor, R. C., Perry, V. H., Tracey, I., Wessely, S., Arseneault, L., et al. (2020). Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 7, 547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1

Jones, R., and Brown, D. (2011). The mentoring relationship as a complex adaptive system: finding a model for our experience. Mentor. Tutor. 19, 401–418. doi: 10.1080/13611267.2011.622077

Kearney, K. S., and Hyle, A. E. (2004). Drawing out emotions: the use of participant-produced drawings in qualitative inquiry. Qual. Res. 4, 361–382. doi: 10.1177/1468794104047234

Komba, S. C. (2016). Challenges of writing theses and dissertations among postgraduate students in Tanzanian higher learning institutions. Int. J. Res. 5, 71–80. doi: 10.5861/ijrse.2015.1280

Lai, A. Y. K., Lee, L., Wang, M. P., Feng, Y., Lai, T. T. K., Ho, L. M., et al. (2020). Mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on international university students, related stressors, and coping strategies. Front. Psychiatry 11:584240. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.584240

Lee, J. J., and Rice, C. (2007). Welcome to America? International student perceptions of discrimination. High. Educ. 53, 381–409. doi: 10.1007/s10734-005-4508-3

Li, J. B., Vazsonyi, A. T., and Dou, K. (2018). Is individualism-collectivism associated with self-control? Evidence from Chinese and US samples. PLoS One 13:e0208541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208541

Ma, H., and Miller, C. (2020). Trapped in a double bind: Chinese overseas student anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Commun. 36, 1598–1605. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2020.1775439

Masgoret, A. M., and Ward, C. (2006). Culture learning approach to acculturation. The Cambridge Handbook of Acculturation Psychology 58–77. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511489891.008

Matsumoto, D., Yoo, S. H., and Nakagawa, S. (2008). Culture, emotion regulation, and adjustment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 94, 925–937. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.6.925

May, R. W., and Casazza, S. P. (2012). Academic major as a perceived stress indicator: extending stress management intervention. Coll. Stud. J. 46:264–274.

McGivern, P., and Shepherd, J. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on UK university students: understanding the interconnection of issues experienced during lockdown. Power Educ. 14, 218–227. doi: 10.1177/17577438221104227

Newsome, L. K., and Cooper, P. (2016). International students’ cultural and social experiences in a British University: “Such a hard life [it] is here”. J. Int. Stud. 6, 195–215. doi: 10.32674/jis.v6i1.488

O’Brien, M., Llamas, M., and Stevens, E. (2012). Lessons learned from four years of peer mentoring in a tiered group program within education. JANZSSA 40, 7–15. doi: 10.3316/informit.T2024042200000391159039187

Pan, J. Y., Wong, D. F. K., Joubert, L., and Chan, C. L. W. (2007). Acculturative stressor and meaning of life as predictors of negative affect in acculturation: a cross-cultural comparative study between Chinese international students in Australia and Hong Kong. Aust. N. Zeal. J. Psychiatr. 41, 740–750. doi: 10.1080/00048670701517942

Pang, H. (2018). Understanding the effects of WeChat on perceived social capital and psychological well-being among Chinese international college students in Germany. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 70, 288–304. doi: 10.1108/AJIM-01-2018-0003

Phua, D. Y., Meaney, M. J., Khor, C. C., Lau, I. Y., and Hong, Y. Y. (2017). Effects of bonding with parents and home culture on intercultural adaptations and the moderating role of genes. Behav. Brain Res. 325, 223–236. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2017.02.012

Ruggeri, K., Garcia-Garzon, E., Maguire, Á., Matz, S., and Huppert, F. A. (2020). Well-being is more than happiness and life satisfaction: a multidimensional analysis of 21 countries. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 18, 192–116. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01423-y

Sanchez, R. J., Bauer, T. N., and Paronto, M. E. (2006). Peer-mentoring freshmen: implications for satisfaction, commitment, and retention to graduation. Acad. Manag. Learn. Edu. 5, 25–37. doi: 10.5465/amle.2006.20388382

Schartner, A. (2015). ‘You cannot talk with all of the strangers in a pub’: a longitudinal case study of international postgraduate students’ social ties at a British university. High. Educ. 69, 225–241. doi: 10.1007/s10734-014-9771-8

Schwartz, S. J., Unger, J. B., Zamboanga, B. L., and Szapocznik, J. (2010). Rethinking the concept of acculturation: implications for theory and research. Am. Psychol. 65, 237–251. doi: 10.1037/a0019330

Searle, W., and Ward, C. (1990). The prediction of psychological and sociocultural adjustment during cross-cultural transitions. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 14, 449–464. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(90)90030-Z

Shadowen, N. L., Williamson, A. A., Guerra, N. G., Ammigan, R., and Drexler, M. L. (2019). Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms among international students: implications for university support offices. J. Int. Stud. 9, 129–149. doi: 10.32674/jis.v9i1.277

Singh, M. K. M. (2015). International graduate students’ academic writing practices in Malaysia: challenges and solutions. J. Int. Stud. 5, 12–22. doi: 10.32674/jis.v5i1.439

Smith, R. A., and Khawaja, N. G. (2011). A review of the acculturation experiences of international students. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 35, 699–713. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.08.004

Spatafora, F., Matos Fialho, P. M., Busse, H., Helmer, S. M., Zeeb, H., Stock, C., et al. (2022). Fear of infection and depressive symptoms among German university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: results of COVID-19 international student well-being study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:1659. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031659

Spencer-Oatey, H., and Xiong, Z. (2006). Chinese students’ psychological and sociocultural adjustments to Britain: an empirical study. Lang. Cult. Curric. 19, 37–53. doi: 10.1080/07908310608668753

Stroebe, M., Schut, H., and Nauta, M. (2015). Homesickness: a systematic review of the scientific literature. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 19, 157–171. doi: 10.1037/gpr0000037

Stroebe, M., Schut, H., and Nauta, M. H. (2016). Is homesickness a mini-grief? Development of a dual process model. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 4, 344–358. doi: 10.1177/2167702615585302

Thomas, G. (2017). How to do your research project: a guide for students. SAGE. Available at: http://digital.casalini.it/9781529784299 (Accessed: June 07, 2020).

Thurber, C. A., and Walton, E. A. (2012). Homesickness and adjustment in university students. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 60, 415–419. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2012.673520

Vickers, M., McCarthy, F., and Zammit, K. (2017). Peer mentoring and intercultural understanding: support for refugee-background and immigrant students beginning university study. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 60, 198–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2017.04.015

Wang, K. T., Heppner, P. P., Fu, C. C., Zhao, R., Li, F., and Chuang, C. C. (2012). Profiles of acculturative adjustment patterns among Chinese international students. J. Couns. Psychol. 59, 424–436. doi: 10.1037/a0028532

Ward, C., Bochner, S., and Furnham, A. (2020). The psychology of culture shock. Hove, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Watermeyer, R., Crick, T., Knight, C., and Goodall, J. (2021). COVID-19 and digital disruption in UK universities: afflictions and affordances of emergency online migration. High. Educ. 81, 623–641. doi: 10.1007/s10734-020-00561-y

Weiler, L., Haddock, S., Zimmerman, T. S., Krafchick, J., Henry, K., and Rudisill, S. (2013). Benefits derived by college students from mentoring at-risk youth in a service-learning course. Am. J. Community Psychol. 52, 236–248. doi: 10.1007/s10464-013-9589-z

Wilson, K. (2020). Man-made virus rumors debunked. Available at: https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202004/22/WS5e9fb641a3105d50a3d1801d.html (Accessed: April 22, 2020).

Wu, Q. (2015). Re-examining the “Chinese learner”: a case study of mainland Chinese students’ learning experiences at British universities. High. Educ. 70, 753–766. doi: 10.1007/s10734-015-9865-y

Xiao, Z. (2020). Mobile phones as life and thought companions. Research Papers in Education 35, 511–528. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2019.1601757

Xiao, Z., Henley, W., Boyle, C., Gao, Y., and Dillon, J. (2020). The face mask and the embodiment of stigma. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/fp7z8

Yamada, Y., Klugar, M., Ivanova, K., and Oborna, I. (2014). Psychological distress and academic self-perception among international medical students: the role of peer social support. BMC Med. Educ. 14, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12909-014-0256-3

Yan, K., and Berliner, D. C. (2009). Chinese international students' academic stressors in the United States. Coll. Stud. J. 43, 939–960.

Yeh, C. J., and Inose, M. (2003). International students’ reported English fluency, social support satisfaction, and social connectedness as predictors of acculturative stress. Couns. Psychol. Q. 16, 15–28. doi: 10.1080/0951507031000114058

Yin, R. K. (2009). “Case study research: design and methods/Robert K,” Yin. Applied social research methods series, 5th ed. London: Sage Publications. 282.

Zhang, J., and Goodson, P. (2011). Predictors of international students’ psychosocial adjustment to life in the United States: a systematic review. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 35, 139–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.11.011

Keywords: acculturative stressors, Chinese international students, COVID-19, intercultural mentoring, wellbeing, stress coping strategy

Citation: Jiang X and Xiao Z (2024) “Struggling like fish out of water”: a qualitative case study of Chinese international students’ acculturative stress in the UK. Front. Educ. 9:1398937. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1398937

Received: 11 March 2024; Accepted: 20 June 2024;

Published: 25 July 2024.

Edited by:

Jonathan Glazzard, University of Hull, United KingdomReviewed by:

Mark Vicars, Victoria University, AustraliaCopyright © 2024 Jiang and Xiao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaoming Jiang, eGoyMTY2OUBlc3NleC5hYy51aw==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.