- 1School of Foreign Languages, Heze University, Heze, China

- 2School of Education and English, University of Nottingham Ningbo China, Ningbo, China

Research incompetence has become a bottleneck hindering the professional development of many CETs (College English teachers) in China, and research on language teachers’ research engagement needs to be enriched. The study explores the CETs’ research engagement in the context of institutional performance evaluation reform at a Chinese non-key university. In-depth interviews of six practitioners show that the prospects of their research engagement are promising but restricted by many personal and contextual constraints. Their motivation to engage with/in research tends to be mainly external despite some gratifying internal drives. The symbiotic teaching-research nexus is not well maintained in practice, the research atmosphere needs improving, and competent research teams are expected to be established and well managed. The professional appraisal reform has initially enhanced the staff’s research enthusiasm, but the boost may wear off due to its weak implementation. The university administration should offer essential resources and relevant support to teachers struggling in their academic careers. Moreover, teachers’ agency to conduct research should be stimulated.

1 Introduction

The appeal for language practitioners’ research is acknowledged internationally to promote their teaching practices (Consoli and Dikilitaş, 2021) and professional development (Sakarkaya, 2022; Woore et al., 2020). Against the university regulatory evaluation scheme (Huang and Guo, 2019), the new higher education institution research policy has swept over more and more universities, including regional application-oriented universities (Gong and Cheng, 2021). Research engagement includes both “engagement in research (i.e., by doing it) and engagement with research (i.e., by reading and using it)” (Borg, 2010, p. 391). In general education, interest in teacher research originated from action research in the middle of the last century in the USA. It receded years later and emerged again in the UK, characterized by the teacher research movement (Barkhuizen, 2009; Borg, 2013). The study on language teachers’ conception of research and their research practice arose at the beginning of this century (Barkhuizen, 2009; Borg, 2013; Borg and Liu, 2013). Research engagement is not widespread in language teaching (Borg, 2009).

Tertiary-level EFL teachers in China account for a relatively high proportion of the world EFL population. Chinese College English teachers are those who teach non-English majors in tertiary education. Due to the increasing number of enrollments in Chinese universities, CETs make up most of the university EFL teachers in China and usually shoulder a heavy workload. College English is a compulsory subject that determines the academic and career prospects of millions of university students in China (Borg and Liu, 2013). Due to a series of documents released by the Ministry of Education in China, esp. College English Curriculum Requirements (Ministry of Education, 2020), scientific research literacy has been listed as one of five essential literacies of CETs. They have to meet high expectations from the Ministry and their institutional management; they are not only required to participate actively in the curriculum reform but also have to conduct scientific research. However, Chinese foreign language teachers’ academic literacy was relatively low (Wen, 2020), the status quo of CETs’ research engagement in China is not very promising, and teacher research is still a barren field in the territory of language teaching (Borg, 2013). Among the limited studies on research engagement in tertiary language teachers in China (E.g., Borg and Liu, 2013; Li, 2023; Wang et al., 2020;), there is a paucity of case studies within the scope of a particular higher education institution, especially the regional universities.

Under the backdrop of higher education expansion at the end of the last century in China, 240 local undergraduate universities have been successively built, each holding 10–20,000 students (Liu, 2012). The educational qualifications of the faculty in these institutions are relatively lower than those in the elite universities. Although some local ordinary universities have been appealed to transform into application-oriented institutions (Li, 2021), the staff must fulfil the academic requirements due to the long-established single evaluation standard for higher institutions from the government and move up of their institution’s ranking. The CETs in these young universities, which have been uncompetitive in academic accumulation and far from the academic frontier, need to be concerned. Their research capacity will, to some extent, affect the quality of overall education in these universities (Ni and Wu, 2023). Thus, this study is intended to explore the CETs’ research practice in these institutions to better promote teacher research and render some suggestions for research management in a similar international context.

2 Literature review

Previous literature about the research of English language teachers (ESL & EFL) mainly focuses on the fields of research perception (Alhassan and Ali, 2020; Bai and Millwater, 2011; Borg, 2009; Liu and Borg, 2014), research engagement (Barkhuizen, 2009; Borg, 2010; Borg and Alshumaimeri, 2012; Borg and Liu, 2013; Gao and Chow, 2011; Rahimi et al., 2018; Xu, 2014), research identity construction (Taylor, 2017; Xu, 2014) and research competence development (Barkhuizen, 2009; Burns and Westmacott, 2018; Taylor, 2017).

Regarding the studies on ESL and EFL teachers’ research engagement, S. Borg is a leading figure. Borg (2009) is a large-scale study based in the international context. Considering his study in 2009 failed to provide the kind of situated understanding of teacher research engagement that can inform local decision-making in a particular context, Simon Borg and Yi Liu conducted a large-scale study on the research engagement of Chinese CETs in 2013, which revealed the participants’ moderate levels of engagement in research. Teachers’ engagement with research has been investigated through the frequency and motivation of reading research, the impacts of engagement with research on teaching, and the corresponding reasons for neglecting existent publications. So is the case of engagement in research.

2.1 Engagement with research among CET in China and other contexts

Teachers’ engagement with research has been proved to be mainly occasionally or periodically (such as applying for promotion) (Borg and Liu, 2013) and confined to a limited time (Wang et al., 2020) except in the context of formal study, while the inner initiative is lacking (Borg, 2013). A “moderately to fairly strong” impact of reading research on teaching was found among the teacher educators in Borg and Alshumaimeri (2012); while such influence was perceived to be “moderate” among the teachers in Borg and Liu (2013) since some of them expect direct and practical impacts on teaching. Situated in a rather broader international context, EFL practitioners’ engagement with research has been perceived or proved to facilitate quality teaching (Tavakoli, 2015; Wyatt and Dikilitas, 2016) or aided their pedagogical decisions (Faribi et al., 2019; Kyaw, 2021; Sato and Loewen, 2019).

Except for the essential reading for promotion or research projects, teachers seldom read literature due to lack of interest and time, inaccessibility of the literature, the irrelevancy between research and teaching, and the unavailability of publications (Borg and Alshumaimeri, 2012; Borg and Liu, 2013; Heng et al., 2023; Sato and Loewen, 2019).

2.2 Engagement in research in China and other contexts

Borg’s (2013) large-scale investigation of Chinese CETs’ engagement in research was not promising (with 52.7% selections of “occasionally”), while Xu’s (2014) study on 4 universities reported a more frequent engagement. The scale and type of universities can be used to explain the divergence. A recent study on Chinese EFL teachers found that they research periodically to address the confusion in teaching or meet the institutional research requirement (Li, 2023). Research also finds that high-ranked practitioners are more research-engaged than the lower ones (Heng et al., 2020), doctoral degree holders are more research-productive and young teachers are potential research leaders (Henry et al., 2020).

Promotion is the most powerful external factor driven EFL prospective and in-service teachers to do research (Bai, 2018; Borg and Liu, 2013; Rahimi et al., 2021; Xu, 2014), together with the internal pursuit of professional development and pedagogical improvement (Alhassan and Ali, 2020; Borg and Liu, 2013; Rahimi et al., 2018; Sato and Loewen, 2019; Xu, 2014) and personal passion and interest (Li and Zhang, 2022; Vu, 2021). For the CETs in teaching-focused non-key universities, the pedagogical values of research seem to be restricted to the rhetorical level (Bai, 2018). Doing research just for the instrumental purpose, such as to get published for promotion rather than for the sake of tackling teaching confusion or professional development, will result in quickly finished products that are not problem-oriented and will not generate any research implications for teaching practices at all (Rahimi et al., 2021).

Research has found that quite a lot of teachers adopt a rather narrow view of the teaching-research nexus. Scientific research falls into two categories, the theoretical ones, and the applied ones (Wen, 2004). Some teachers prefer practical and applied research which are rather constructive in solving realistic problems in the classroom rather than theoretical ones. However, efficient teaching should be based on scientific rationales, both theoretical and applied research can assist teaching (Chen and Wang, 2013). Some teacher educators also find it rather challenging for them to translate their studies on higher education into direct implications benefiting teachers’ professional practice although they believe in the symbiotic relationship between teaching and research (Yuan and Lee, 2014). Nevertheless, previous studies on teachers’ perceptions and engagement in research have proved that research findings can be transformed into teachers’ pedagogical knowledge, contribute to their professional development, and in turn benefit the students (Alhassan and Ali, 2020; Borg and Alshumaimeri, 2012; Jamoom and Al-Omrani, 2021; Rahimi et al., 2018). Participants in Rahimij and Weisi (2018) report a quite favorable research engagement and admit that research engagement has positively impacted their professional teaching practice (such as enhancing their confidence and autonomy in teaching, developing their reflection competence and critical thinking, understanding their students better and improving their language learning), and promoted team cooperation. The reason may be those who have active research engagement were purposefully selected for the study. Even so, the findings also indicate that institutional support needs to be increased and assistance in instrument design and data analysis needs to be offered to teachers. Only when CETs realize the closely bonded tie between teaching and research by themselves can they positively engage in the two missions and better tackle the requirement of teaching-research integration from the institution (Ni and Wu, 2023).

Concerning constraints hindering teachers from doing research, the most typical ones are: lack of time, resources, and mentors, illiteracy in doing research (Allison and Carey, 2007; Barkhuizen, 2009; Borg and Liu, 2013; Heng et al., 2023; Sato and Loewen, 2019; Xu, 2014); heavy workload (Alhassan and Ali, 2020; Borg and Liu, 2013; Vu, 2021; Yuan and Lee, 2014); difficulty of getting published, lack of interest and motivation (Borg and Liu, 2013; Gao and Chow, 2011; Xu, 2014); the demanding features of research to teachers (Tarrayo et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020).

2.3 Research culture in China and other contexts

Academic collaboration can enhance research motivation and productivity (Heng et al., 2020; Paul and Mukhopadhyay, 2022). The inspiring work environment is conductive to the academics’ research (E.g., Way et al., 2019). A moderately positive research culture was found in previous large-scale investigations by Borg and Liu (2013). Lack of institutional research culture has been blamed for hindering teachers’ research engagement (e.g., Alhassan and Ali, 2020). There is a gap between management research expectations and the support offered to teachers (Alhassan and Ali, 2020; Borg and Alshumaimeri, 2012; Borg and Liu, 2013; Kyaw, 2021). Collaborative research and collegial discussion about research are not desirable due to the competition among colleagues (Borg and Liu, 2013). CETs’ research competence cannot meet the institutional research requirements (Liu, 2011).

2.4 The impacts of the appraisal policy reform

Under the backdrop of the contemporary university managerial revolution (Amaral et al., 2003), research productivity is increasingly vital to the university’s ranking and reputation (Morze et al., 2022). The new higher education institution research policy has swept over more and more universities and brought diverse emotional experiences to the EFL practitioners. Those teachers tend to react rather positively when their professional values and pursuits are consistent with the reform objectives, but the larger number are the pressured supporters (Tran et al., 2017; Zhang, 2021).

As for the development of research competence, institutional support, advice from competent mentors, and the teachers’ agency all play an important role (Xu, 2014). Language practitioners can be encouraged to conduct some classroom-based research in flexible forms due to the limit of their methodology reserve (Borg and Sanchez, 2015), such as action research, narrative inquiry (Johnson and Golombek, 2002), reflective practice (Mann and Walsh, 2017), etc. Teachers could start their research based on the problems confronted in their classrooms, or they may take part in an action research program guided by capable mentors, as suggested in Barkhuizen (2009), Burns and Westmacott (2018), and Taylor (2017). In-service professional training can serve as a good mediator facilitating teachers’ research engagement (Borg, 2010).

Scanning over the previous studies, besides the large-scale study on the research engagement of Chinese CETs in Borg and Liu (2013) and Chinese EFL teachers in Li (2023), Bai and Millwater (2011) is an institutional study focusing on Chinese EFL academics who teach English majors. Barkhuizen (2009) focuses on the research lives of CETs from all kinds of Chinese universities. Xu (2014) studied the EFL teachers working at four universities in China. The institutional study of CETs’ research engagement is scarce, especially situated in non-elite ordinary universities. Among the very few studies on local undergraduate universities, Ni (2022), which focuses on CETs’ conceptions of research, has found that the CETs have broadened their perceptions of research. The younger lecturers, who tend to have higher educational qualifications than the associate professors, seem to have more rigorous and comprehensive conceptions of research. However, the role of a CET has hindered their conceptions of research and negatively affected the construction of their researchers’ identities. Ni and Wu (2023) is a longitudinal study tracing a CET’s cognitive development in the teaching-research nexus. Having finally stepped out of the teaching-research contradiction, the participating teacher achieved professional development in both teaching and research and also gradually identified herself as a researcher besides a teacher. However, research on CETs’ research engagement in local undergraduate institutions is still regrettably scarce.

Both Borg and Liu (2013) and Wang et al. (2020) called for continual empirical research in the future, “both large-scale and in the form of specific case studies of individual language teaching organizations” (Borg and Liu, 2013, p. 293), since teacher research engagement is context situated. When the new higher education institution research policy (Tran et al., 2017) has finally been expanded to the non-key local universities in China, what are their CETs’ status quo of research engagement and responses to such reform, further research is needed.

3 Methodology

3.1 Research site and research focus

University F (pseudonym) was chosen to be the research site since a new appraisal policy was issued a year ago before the study which has changed the tenure status of professional titles. Staff in each professional title are required to publish and get corresponding research projects in a three-year appraisal term.

Those who fail to meet the requirements will be demoted to the previous professional title. The CETs’ research engagement in this university and their response to such a big policy change appeal to the author to take such a study. The current research aims to answer the following questions:

(1) How do CETs in Chinese regional universities engage with research compared to their counterparts in other contexts?

(2) How do CETs in Chinese regional universities engage in research compared to those in other international contexts?

(3) How does the research culture in Chinese regional universities compare to the that in universities in other parts of the world?

(4) What are the impacts of the appraisal policy reform on the research activities and motivation of College English Teachers (CET) in China?

3.2 Participants

The College English Unit in University F is affiliated with the College of Foreign Languages. Its staff is dominated by two professional types, i.e., the lecturers and associate professors. Most of the staff are comprised of female teachers. There were no teaching assistants, professors, or PhD holders when the research was conducted. Therefore, based on the status quo of the staff, the participants were purposely selected for maximum variation (Miles and Huberman, 1994) of the professional title structure, gender distribution, and years of teaching. Interview invitations were sent to 8 teachers, 6 of them consented to take part in the interviews. They signed written informed consent and were guaranteed confidentiality and anonymity before the interview started. The demographic information about the participants (all reported under pseudonyms) can be seen in the following table (Table 1).

3.3 Instruments

Specific research approaches are employed based on the issue being addressed (Creswell and Creswell, 2018). The study attempts to explore CETs’ research engagement and the institutional academic culture in the context of performance evaluation reform, so using open-ended questions is more suitable for understanding the status quo and reaching general themes inductively. Thus, a semi-structured, in-depth interview was used to collect the data. The interview questions (See Appendix) were based on the items related to research engagement in Borg and Liu (2013) and Xu (2014). Minor revisions were made to adjust to the context of the discussion. Several questions were added based on the promotion reform in University F and the institutional policy in the College of Foreign Languages. Besides engagement, the participants’ conceptions of research were also collected. Due to space limitations, only their research engagement will be reported here.

3.4 Data collection and analysis

Forms of the interview were negotiated according to the convenience of the participants and were finally conducted either face-to-face, by social media, or over the telephone. The interview time ranged from 33 to 82 min. The interviews were conducted in Chinese, tape-recorded with the permission of the participants, and transcribed verbatim into Chinese. After the member check from the participants, all the transcripts were translated into English and then sent back to the participants once more to check for any inaccuracies during translation or alternations. Permission to make public was obtained from them after the special treatment of some parts that may disclose their identities. The interpretations in the article were also sent to them to verify authenticity and ask for their permission for use.

Qualitative content analysis (Miles and Huberman, 1994) was used to analyze the interview scripts. NVivo 12 plus was employed to help generate the codes. One hundred fifty initial codes were generated, then similar codes were classified into superior themes, and finally, themes were grouped into several categories according to the literature. The coding goes like this. For example, Juan said, “I am highly motivated and agentic, and I have been working hard these years, but I am a little frustrated since I have not achieved much until now.” This part was coded primarily as “High agency but few achievements” and then classified into the theme “The status quo of research” and then classified into the category “Engagement in research.”

4 Findings

The findings are reported in four categories according to the research questions and previous literature. Regarding engagement with research, the reading frequencies, motivation, the impact of reading on teaching or professional development, and the constraints will be reported sequentially. So is engagement in research. Teachers’ perceptions of the research atmosphere and research communities in the department are classified in the category of research culture. Lastly, the influence of the new appraisal policy is mentioned.

4.1 Engagement with research

The frequency of reading research is negatively correlated with the teaching experience and professional titles. The young lecturers are more engaged in the publications than the senior associate professors. Lian reported that reading research was done many years ago when she was applying for the associate professorship. However, as for Juan, reading research is one of her activities in every busy day besides teaching and child-care. Moreover, engagement with research is mainly “periodical” when they decide to prepare for the professional appraisal or apply for research projects. For example, Yong told me about his situation before promotion, “I had to read some books and should not idle away anymore since I have to apply for promotion, but I gave it up after I got promoted.”

As for the motivation for reading research, besides the major external one, i.e., for promotion, the sake of self-interest, individual professional development, and the concern of practical classroom problems are also mentioned. Juan reads literature to find the answers to her doubts about teaching. She is also a typical example who has found her research interests by seeking solutions to the obstacles in her professional development.

My reading originated from my interest issue. Suppose I would like to make a list of the priorities. Professional development is the priority, followed by promotion, and the third is to solve doubts in the classroom. (Juan).

Most of them claimed that extensive reading has benefited their teaching. For example, Juan stated that the strategies mentioned in the literature of discussion classrooms were later used in her class. However, Yong, whose research interest is Translation, claimed that literature reading had little influence on his teaching since the profound documents he read were beyond the basic level of college English teaching.

As for the factors blocking their reading process, “lack of time, the overwhelming teaching task, limited resources in the library, and low literature searching literacy” were mentioned.

Juan, Dan, and Hong complained about limited resources since they could not access international publications from the library database. Juan was reading international journal articles offered by her former classmate who was pursuing a Ph.D. when the interview was conducted. Dan also confided that she was lacking in the literacy of searching for documents, especially, international ones. Hong booked two domestic key journals out of her pocket for convenience’s sake.

4.2 Engagement in research

The participants’ engagement in research differs significantly between the two professional titles. The two associate professors last engaged in research a few years ago. As for the four lecturers, Dan thinks about her research questions even during childcare. Juan devotes a lot to research: She reads literature every day and already produced two research articles recently, although they still fall short of her expectations in research. Yong gave up his ambition to study corpus due to his weak academic literacy in this field. Hong stated she belonged to those who were “strong in will, but weak in action.”

The motivation for doing research is like that of literature reading, i.e., primarily for promotion. However, interior motivation also exists, such as internal interest in a certain field, to improve academic literacy and professional development. For example, Juan felt that the college English teaching at University F was out of date and demanded a change, but first the change should start with herself, a college English teacher. Such reflection has helped her lock her research focus on language teacher professional development.

Most of them believe in the symbiotic relationship between teaching and doing research and can interpret their relations in detail. Nevertheless, when it comes to actual practice, the case is not that optimistic. That is a remarkable finding in this study. For example, Juan stated that her research practice was not used in her class yet since her writing was not high-level production. Dan also felt regretful when she discussed the common situation of her colleagues’ research engagement.

In actual practice, teaching is isolated from research. Most teachers do not try to use the research findings to guide their teaching. They leave their papers alone. What are your research findings? You may not be severe enough to think about them in your mind. It should go like this: teaching promotes research, and then research feeds teaching. However, now it seems a little separated. (Dan).

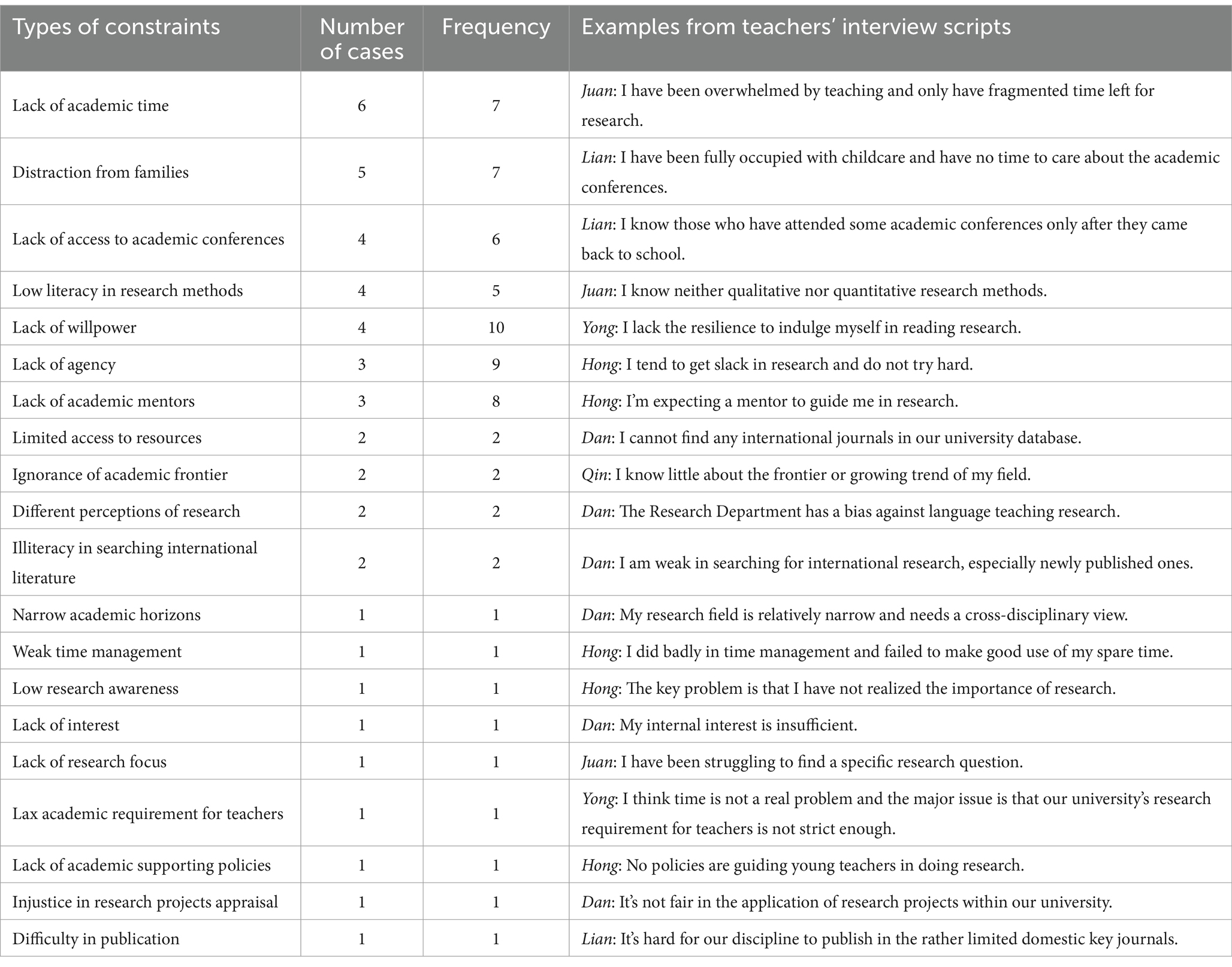

Challenges in doing research are the most densely coded part (see Table 2). As for the difficulties hindering their research engagement, the typical four factors are “lack of time,” “distraction from home,” “lack of access to academic conferences,” “illiteracy in research methods,” and “lack of willpower.” Since CETs are usually fully occupied with teaching and female practitioners also suffer from the distraction from their families, they often have no choice but to struggle for the fragmented time to do research. However, Hong mentioned that all these obstacles could be overcome if they tried to manage their time properly and had strong willpower in research. “Lack of willpower and agency” is also a frequently mentioned internal weakness by several teachers. However, there is such a teacher, i.e., Juan, who started with her doubts in professional development, explored again and again through literature reading, found her research focus and kept moving forward in such an adverse context. Her high agency may set a good example for those staff in the non-key universities.

“Low literacy in research methods” (which has been referred to five times by four teachers) is a typical barrier restricting teachers from moving forward. Juan claimed that she had not reached any significant achievement, even though she worked hard and read literature daily. The major obstacle she ever perceived was the weakness in research methods. Dan, a teacher who has mastered the quantitative research methodology, also stated that she knew little about the most advanced research methods. Even the senior teacher, Lian, complained that she did not have time to learn the research methods.

“Lack of a mentor” is also mentioned by several participants. They wish there were such a person who could guide them forward but could not find one in their workplace. When asked about someone who has impacted their research journey, most still referred to their supervisors or former teachers while pursuing their master’s degrees rather than an experienced colleague nearby who could assist them.

Both Dan and Juan complained about their limited literature-searching literacy, especially the international ones. Juan felt rather frustrated since sometimes she was at a loss about the literature to read but started from the most preliminary ones. Another prominent doubt mentioned by Dan and Juan was that the Research Office in their university had a bias against language teaching research. Their research project proposals failed several times to move beyond the university campus because their research territories were restricted to teaching, even some of their studies could not even be classified as teaching research at all.

My project was rejected because they (the management in the Research Office) said my research was so close to teaching and did not have the sense of authentic research. They will not care about your project at all even if you have lots of relevant previous studies. I have been puzzled for a long time since research cannot be separated from teaching. Our research focus originates from the practical problems in teaching, is not it? However, they think those studies having no relation to teaching are research. I want to change my research focus, but it is challenging since it has been my research interest for many years. (Dan).

I wonder why they perceive teacher professional development as teaching research. (Juan).

4.3 Research culture

There is a lack of research atmosphere in the College English Unit. Teachers seldom discuss research with each other. Those who want to pursue research cannot get access to the assistance and relevant resources they need. Both Juan and Dan confided that only a few of their colleagues were pursuing their research and most others were doing “research” for the sake of gaining research projects or publishing papers. Juan even stated that most of the staff’s research engagement was not authentic research at all. She also suggested that they should try to do something down to earth and reap the professional titles as the natural result. However, some have sensed something different recently, i.e., a positive tendency was growing among the Unit due to the encouragement of the faculty administration and university academic requirements. E.g.,

Recently, I have seen quite a few teachers searching for literature and preparing for their publications. (Yong).

There are no real research communities; most teachers do research individually, and they only cooperate with others when applying for research projects in which an academic team is required as customary. As for the reasons, Dan stated that she had already adapted to work individually and had not found such an efficient research mate who was also willing to cooperate. Juan said she had not fixed her research focus yet and was not ready to cooperate with a partner. Yong stated that due to the limited academic competence of the faculty, large-scale research that demanded team cooperation was still on the way.

Although the college’s vice president appealed to all the staff to set up several scientific research teams to enhance research literacy, they did not work well and achieve the due function at all. The required seminars in each team were held only once just after their establishment. The president meant well, and the staff’s research awareness has been awakened. However, several factors resulted in its inefficiency, such as each member’s weak willpower and limited research foundation, poor organization, and lack of time and communication. The team leaders’ academic competence also needs to be improved. What is more, the team members’ inadequate research experience may also be blamed, although they joined a certain team according to their supposed research interests, just as the comments of Juan and Hong:

As the leader of my team, I’m not capable at all. Even if I am interested in some topics, I have no idea how to lead the team forward. I am unclear about what kinds of literature I should assign them to read and what kind of work to do for each member. (Juan).

Many teachers do not research at all and have not found their research interests yet. Therefore, they just wait there for the arrangements since they are not clear on what to do at all. (Hong).

4.4 The impacts of the appraisal policy reform

The interviews were conducted 1 year later after the promotion reform. The effects on the staff can be seen at this moment. The interview scripts show that both positive and negative influences coexist. The positive factors can be summarized as motivational effects and positive guidance. For example, Yong, Juan, and Hong all viewed it as a motivation in another way. Some of them initially felt slightly anxious but gradually accepted it and decided to strive to meet it. Such as Juan’s statement,

Although it did bring me some pressure, the reform is beneficial to some degree and is a kind of motivation in another way, since I have been doing something myself. (Juan).

The appraisal reform did put some pressure on the staff, especially on senior teachers who are less energetic than their young peers and associate professors who have left their academics uncultivated for many years. E.g.,

I am stressed out since it is hard to catch up with the field after years of neglect. Moreover, the publication requirement is so heavy, esp., for our discipline. Getting our paper published in a few key journals is challenging and takes much work. Could we be treated especially just as that of the staff in the faculties of music, arts, and physical education? (Lian).

It (the policy) does not consider teachers’ research ability. I’m afraid some teachers may muddle through it if they are under too much pressure. (Yong).

However, Dan blamed the unfairness in the preliminary appraisal of provincial research projects within the campus and the new promotion policy for young teachers to apply for associate professorships.

The new requirement for promotion to the associate professorship is very high and there is not much vacancy left. One year has passed since the promotion reform, and some associate professors who were promoted three years ago received their periodical appraisal. However, they passed it by joining others’ provincial projects. The reform seems more relaxed with them, but the young teachers still have a long way to go. (Dan).

5 Discussion

5.1 Engagement with research

Teachers’ periodical engagement with research resonates with previous findings in Borg and Liu (2013) and differs from that in Xu (2014). Promotion has been proven as the most typical factor motivating their literature reading. Nevertheless, some teachers, despite being few, who read publications driven by their internal interests and professional development, just as has been proven by Faribi et al. (2019), Kyaw (2021), and Sato and Loewen (2019).

Different from Borg and Liu (2013), most participants reported a positive influence of reading literature on teaching and can put it into detail or offer an exact example, which resonates with findings in Rahimi et al. (2018). The reason may arise from the appeal for university teachers to do research in China in the past decade. Teachers’ awareness of the teaching-research nexus has been enhanced. Similar to some teachers’ perceptions in Borg and Liu (2013) and Bai (2018), some teachers expect a direct influence of research on teaching, especially, those whose research interests are not around applied linguistics. Teachers’ narrow perceptions of teaching-research nexus should be warned and expanded (Chen and Wang, 2013). More work should be done to bridge the gap between academics’ research and practitioners’ teaching and professional development (Yuan and Lee, 2014).

Despite having been mentioned in some of the previous literature (e.g., Alhassan and Ali, 2020; Kyaw, 2021; Sato and Loewen, 2019), limited access to frontier publications and illiteracy in searching international literature are indeed typical barriers to teachers in local universities. This can be proved by the variety of their reading, which is mainly restricted to domestic publications. University F’s limited research funds and emergent research infrastructure may be part of the reason for this. The university administrators should increase the investment in international databases and the CETs can get access to the shared resources and improve their digital literacy by actively joining some research communities offline or online.

Contrary to the positive correlation in Borg and Alshumaimeri (2012) and Borg and Liu (2013), teachers’ frequency of reading research is negatively correlated with teaching experience and professional titles. This may be because many associate professors in non-key universities give up their efforts to climb to the uppermost level of professional titles since it is so challenging. Another reason originates from University F’s tenure policy for years.

5.2 Engagement in research

Teachers’ frequency and motivation for doing research is in line with that of reading research, mainly periodically and for promotion, which is consistent with the interpretation of the interview data in Borg and Liu (2013) and the findings in Gao and Chow (2011), and Li (2023), the institutional requirement was the most prominent reason for doing research. The limited research engagement and the corresponding restrictions resonate with the case in other underdeveloped Asia countries, e.g., the case of Cambodia in Heng et al. (2023). Although most teachers perceive a close relationship between reading research and teaching, their engagement in research is driven by external factors. That is why they publish for the sake of publication. However, some young lecturers have already developed reform awareness and want to make a change in CETs’ professional development. Their higher academic literacy and more frequent research engagement than the associate professors are contrastive to those of Heng et al. (2020). The reason may be that young teachers have received full-time postgraduate education and are more competent in research in regional universities. It also proves the effects of individual practitioner’s agency in managing personal, workplace, and sociocultural influences (Xu, 2014).

Different from engagement with research, teachers’ perception of the influence of their research production on teaching is not that promising. Maybe due to all kinds of contextual and individual constraints, the CETs in non-key universities still have a long way to go to improve the quality of their research, especially, in terms of scientificity and practicality.

Besides the objective obstacles, such as “lack of time” and “distraction from home,” which have been proved by Borg and Liu (2013), Heng et al. (2023), Sato and Loewen (2019), and Xu (2014), internal factor, such as “lack of will power” is also reported as a major point hindering their academic career, which is an essential discovery in this study. The reason may originate from University F’s tenure appraisal policy for decades. Moreover, another difficulty, “illiteracy in research methods,” which has been discussed by Barkhuizen (2009) and Wang et al. (2020), may be due to the educational background of the staff among whom there are no PhD holders, and they are not able to access systematic academic training and the academic conferences. That is why they are still struggling on the periphery of academics, although some are working rather hard. Non-key universities’ limited research funds may be further blamed. Language practitioners’ action research and narrative inquiry, which are not so methodologically challenging (Borg and Sanchez, 2015), can be better ways to initiate preliminary studies.

“Lack of mentor” may be a severe difficulty in the context of local undergraduate universities since most participants still recall the help of their former supervisors, teachers, and even PhD students far away, rather than the nearby assistants or institutional support. Another discovery is that language teaching research is discriminated against by the administration in the office of academic research at the university. It is different from the previous findings in Borg and Liu (2013), i.e., the divergent perception of research between teachers and the institution: Whether research needed to be published or not. It furthermore proves that beyond personal factors, sociocultural contexts also have a profound impact on language teachers’ research engagement (Borg and Liu, 2013).

5.3 Research culture

Despite being on the track of gradually improving, the research atmosphere at University F has yet to be positive. The institutional academic requirement for teachers does not match the corresponding support (Alhassan and Ali, 2020; Kyaw, 2021). Research is not frequently discussed, and research teams exist only superficially. The finding echoes that of Borg and Alshumaimeri (2012), and Borg and Liu (2013), but the reason is slightly different. Most teachers fail to devote themselves to research and have not fixed their research territories yet. They read and write just for the sake of publications or research projects. Such a research culture fails the scientific teams organized by the vice president, who are full of expectations. It will lead to a vicious publication cycle that will not benefit teaching (e.g., Rahimi et al., 2021). However, a few young teachers try to bury themselves in research and may grow to play a leading role in the faculty. Thus, a promising future is just around the corner.

5.4 The impacts of the appraisal policy reform

The appraisal policy reform may come later to University F than its key counterparts. It pressured the staff, especially senior associate professors, just as some participants complained, i.e., the reform did not consider the staff’s academic literacy (Liu, 2011) and the institutional types. Just as the emotional classification in Tran et al. (2017), the teachers who initiated their research intrinsically supported the policy more positively without suffering too much anxiety. However, a rather loose manner was adopted in the actual implementation, esp. the criterion of performance evaluation for the associator professors. It is challenging to be promoted to a higher rank, but keeping the rank is not as challenging as stated. It echoes Xu (2014) that punishing was less than rewarding. Compared with the “publish or perish” policy in leading universities, it is relatively humane for teachers, while the motivation force may be watered down simultaneously. Moreover, the institutional appraising policies still need some adjustment to be fair and rational towards those struggling young teachers for the position of associate professorship. Moreover, language practitioners’ academic research can start from the study of teaching, but the regional universities’ prejudice against teaching research may serve as another block to the staff’s professional development and the institution’s research productivity.

6 Conclusion

CETs’ research engagement in non-key universities is gradually turning around. However, there are considerable constraints, such as lack of time, resources, guidance, research interests, willpower, illiteracy in methodology, and the dim prospects of language teaching research. They tend to engage themselves with or in research driven by utilitarianism and fail to integrate teaching with research due to their narrow perception of the teaching-research nexus and limited research literacy. Restrained by weak academic accumulation on the whole and rank evaluation competition, a promising research culture is still on the way.

The administrators in charge of scientific research in the College English Unit should regularly invite teacher educators or competent academics from other research-oriented universities to give relevant academic training in research skills to the in-service teachers. Teachers’ continuous professional development should be a standard and sustainable state. Prospective and competent teacher researchers can be encouraged to set up effective research teams and navigate the other teachers to engage with research and gradually fix their research interests. Some individual difficulties, such as illiteracy in searching literature, can be solved through discussion and literature sharing among a rather constructive research community. Action research can be encouraged to focus on the current problems confronted in teaching. Non-key universities’ research reform should be promoted step by step based on a thorough investigation of the current status quo of the staff’s research engagement. Teachers’ viewpoints should be collected beforehand.

The article is without limitations. Firstly, a theoretical perspective is lacking. Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory can be used in the upcoming studies to explore the interaction of personal and contextual factors affecting the tertiary language practitioners’ research engagement and productivity. Secondly, the interviews with associate professors yielded less robust data than those with lecturers. Their long-deserted research engagement may be a possible reason, but the author’s inexperience in eliciting further explanation may be blamed. Moreover, another limitation of the present study lies in the relatively small sample size, with only six participants being included in the analysis. Future research may invite a more extensive and diverse sample to promote the validity and generalizability of the findings.

Future research can also be focused on how to motivate language practitioners’ agency and initiatives to engage with and in research, such as to enhance their cognition in the teaching-research nexus and establish their identity as researchers besides teaching technicians. Only in this way can CETs be actively involved in problem-driven research and generate constructive pedagogical implications. Moreover, the research perceptions of the management in the Research Office at local universities are expected to be explored and promoted.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was signed by the participants respectively, and they were guaranteed confidentiality and anonymity before the interview started.

Author contributions

HN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to those teachers who took part in this study.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alhassan, A., and Ali, H. (2020). EFL teacher research engagement: towards a research-pedagogy nexus. Cogent Arts Human 7:1840732. doi: 10.1080/23311983.2020.1840732

Allison, D., and Carey, J. (2007). What do university language teachers say about language teaching research? TESL Canada J. 24, 61–81. doi: 10.18806/tesl.v24i2.139

Amaral, A., Fulton, O., and Larsen, I. M. (2003). “A managerial revolution?” in The higher education managerial revolution. eds. A. Amaral, V. L. Meek, and I. M. Larsen (Dordrecth: Kluwer Academic Publishers), 275–296.

Bai, L. (2018). Language teachers’ beliefs about research: a comparative study of English teachers from two tertiary education institutions in China. System 72, 114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2017.11.004

Bai, L., and Millwater, J. (2011). Chinese TEFL academics’ perceptions about research: an institutional case study. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 30, 233–246. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2010.512913

Barkhuizen, G. (2009). Topics, aims, and constraints in English teacher research: a Chinese case study. TESOL Q. 43, 113–125. doi: 10.1002/j.1545-7249.2009.tb00231.x

Borg, S. (2009). English language teachers’ conception of research. Appl. Linguis. 30, 358–388. doi: 10.1093/applin/amp007

Borg, S. (2010). Language teacher research engagement. Lang. Teach. 43, 391–429. doi: 10.1017/S0261444810000170

Borg, S. (2013). Teacher research in language teaching: A critical analysis. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Borg, S., and Alshumaimeri, Y. (2012). University teacher educators’ research engagement: perspectives from Saudi Arabia. Teach. Teach. Educ. 28, 347–356. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2011.10.011

Borg, S., and Liu, Y. (2013). Chinese college English teachers’ research engagement. TESOL Q. 47, 270–299. doi: 10.1002/tesq.56

Borg, S., and Sanchez, H. S. (2015). “Key issues in doing and supporting language teacher research,” in International perspectives on teacher research. eds. S. Borg and H. S. Sanchez (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK), 1–13.

Burns, A., and Westmacott, A. (2018). Teacher to researcher: reflections on a new action research program for university EFL teachers. Profile 20, 15–23. doi: 10.15446/profile.v20n1.66236

Chen, H., and Wang, H. (2013). Investigation and analysis of college English teachers’ attitude towards research. Foreign Lang. Teach. 270, 25–29. doi: 10.13458/j.cnki.flatt.003910

Consoli, S., and Dikilitaş, K. (2021). Research engagement in language education. Educ. Action Res. 29, 347–357. doi: 10.1080/09650792.2021.1933860

Creswell, J. W., and Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Faribi, M., Derakhshan, A., and Robati, M. (2019). Iranian English language teachers’ Conceptions toward research. Iran. J. Educ. Sociol. 2, 1–11.

Gao, X., and Chow, A. (2011). Primary school English teachers’ research engagement. ELT J. 66, 224–232. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccr046

Gong, K., and Cheng, J. (2021). How to construct appropriate teacher evaluation system in application-oriented universities: a case study of the teacher evaluation system of Williams College. Stud. Foreign Educ. 48, 3–20.

Heng, K., Hamid, M. O., and Khan, A. (2020). Factors influencing academics’ research engagement and productivity: a developing countries perspective. Issues Educ. Res. 30, 965–987.

Heng, K., Hamid, M. O., and Khan, A. (2023). Research engagement of academics in the global south: the case of Cambodian academics. Global. Soc. Educ. 21, 322–337. doi: 10.1080/14767724.2022.2040355

Henry, C., Md Ghani, N. A., Hamid, U. M. A., and Bakar, A. N. (2020). Factors contributing towards research productivity in higher education. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 9, 203–211. doi: 10.11591/ijere.v9i1.20420

Huang, Y., and Guo, M. (2019). Facing disadvantages: the changing professional identities of college English teachers in a managerial context. System 82, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2019.02.014

Jamoom, O., and Al-Omrani, M. (2021). EFL university teachers’ engagement in research: reasons and obstacles. Int. J. Linguist. Transl. Stud. 2, 135–146. doi: 10.36892/ijlts.v2i1.121

Johnson, K. E., and Golombek, P. R. (2002). “Inquiry into experience: Teachers’ personal and professional growth,” in Teachers’ narrative inquiry as professional development. eds. Johnson, K. E., and Golombek, P. R. (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press).

Kyaw, M. T. (2021). Factors influencing teacher educators’ research engagement in the reform process of teacher education institutions in Myanmar. SAGE Open 11:215824402110613. doi: 10.1177/21582440211061349

Li, J. (2021). New Directions of Local Higher Education Policy: Insights from China. Singapore: Springer Nature.

Li, Y. (2023). Teachers’ motivation, self-efficacy, and research engagement: A study of university EFL teachers at the time of curriculum reform in China [Doctoral dissertation, University of Auckland]. ResearchSpace @ Auckland.

Li, Y., and Zhang, L. J. (2022). Influence of mentorship and the working environment on English as a foreign language teachers’ research productivity: the mediation role of research motivation and self-efficacy. Front. Psychol. 13, 1–17. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.906932

Liu, Y. (2011). Professional identity construction of college English teachers: A narrative perspective. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

Liu, Y. (2012). An investigation of 100 universities: the development of the “new universities in China”. Modern Univ. Educ. 1, 18–23.

Liu, Y., and Borg, S. (2014). Tensions in teachers’ conceptions of research: insights from college English teaching in China. Chinese J. Appl. Linguist. 37, 273–291. doi: 10.1515/cjal-2014-0018

Mann, S., and Walsh, S. (2017). Reflective practice in English language teaching: Research-based principles and practices. Abingdon: Routledge.

Ministry of Education (2020). College English curriculum requirements. Beijing: Higher Education Press.

Morze, N. V., Buinytska, O. P., and Smirnova, V. A. (2022). Designing a rating system based on competencies for the analysis of the university teachers’ research activities. CEUR Workshop Proceed. 9, 139–153. doi: 10.55056/cte.109

Ni, H. (2022). College English teachers’ conceptions of research: an institutional case study from China. Teach. Educ. Curric. Stud. 7, 118–124. doi: 10.11648/j.tecs.20220704.11

Ni, H., and Wu, X. (2023). Research or teaching? That is the problem: a narrative inquiry into a Chinese EFL teacher’s cognitive development in the teaching-research nexus. Front. Psychol. 14:1018122. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1018122

Paul, P., and Mukhopadhyay, K. (2022). Measuring research productivity of marketing scholars and marketing departments. Mark. Educ. Rev. 32, 357–367. doi: 10.1080/10528008.2021.2024077

Rahimi, M., Yousoffi, N., and Moradkhani, S. (2018). Research practice in higher education: views of postgraduate students and university professors in English language teaching. Cogent Educ. 5:1560859. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2018.1560859

Rahimi, M., Yousoffi, N., and Moradkhani, S. (2021). The setbacks for research practice in higher education: a perspective from English language teaching in Iran. Iran. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 9, 109–127. doi: 10.30466/ijltr.2021.121048

Rahimij, M., and Weisi, H. (2018). The impact of research practice on professional teaching practice: exploring EFL teachers’ perception. Cogent Educ. 5:1480340. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2018.1480340

Sakarkaya, V. (2022). What triggers teacher research engagement and sustainability in a higher education context in Turkey? Participatory Educ. Res. 9, 325–342. doi: 10.17275/per.22.43.9.2

Sato, M., and Loewen, S. (2019). Do teachers care about research? The research–pedagogy dialogue. ELT J. 73, 1–10. doi: 10.1093/elt/ccy048

Tarrayo, V. N., Hernandez, P. J. S., and Claustro, J. M. A. S. (2021). Research engagement by English language teachers in a Philippine university: insights from a qualitative study. Asia Pac. Soc. Sci. Rev. 21, 74–85. doi: 10.59588/2350-8329.1387

Tavakoli, P. (2015). Connecting research and practice in TESOL: a community of practice perspective. RELC J. 46, 37–52. doi: 10.1177/0033688215572005

Taylor, L. A. (2017). How teachers become teacher researchers: narrative as a tool for teacher identity construction. Teach. Teach. Educ. 61, 16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.09.008

Tran, A., Burns, A., and Ollerhead, S. (2017). ELT lecturers’ experiences of a new research policy: exploring emotion and academic identity. System 67, 65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2017.04.014

Vu, M. T. (2021). Between two worlds? Research engagement dilemmas of university English language teachers in Vietnam. RELC J. 52, 574–587. doi: 10.1177/0033688219884782

Wang, B., Zhang, Y., and Zhang, L. (2020). On the status quo of college English teachers’ scientific research and influencing factors. Testing Eval. 3, 102–109.

Way, S. F., Morgan, A. C., Larremore, D. B., and Clauset, A. (2019). Productivity, prominence, and the effects of academic environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 10729–10733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1817431116

Wen, Q. (2004). Applied linguistics: Research methods and thesis writing. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

Wen, Q. (2020). Accelerating the internationalization of Chinese applied linguistic theories: reflections and suggestions. Modern Foreign Lang. 43, 585–559.

Woore, R., Mutton, T., and Molway, L. (2020). ‘It’s definitely part of who I am in the role’. Developing teachers’ research engagement through a subject-specific master’s programme. Teach. Dev. 24, 88–107. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2019.1693421

Wyatt, M., and Dikilitas, K. (2016). English language teachers becoming more efficacious through research engagement at their Turkish university. Educ. Act. Res. 24, 550–570. doi: 10.1080/09650792.2015.1076731

Xu, Y. (2014). Becoming researchers: a narrative study of Chinese university EFL teachers’ research practice and their professional identity construction. Lang. Teach. Res. 18, 242–259. doi: 10.1177/1362168813505943

Yuan, R., and Lee, I. (2014). Understanding language teacher educators’ professional experiences: an exploratory study in Hong Kong. Asia Pac. Educ. Res. 23, 143–149. doi: 10.1007/s40299-013-0117-6

Zhang, L. J. (2021). Curriculum innovation in language teacher education: reflections on 31 years of the PGDELT programme for teacher continuing professional development. Chin. J. Appl. Linguist. 44, 435–450. doi: 10.1515/CJAL-2021-0028

Appendix

Interview questions:

1. Could you please tell me what your research interest is?

2. Could you please describe a typical work day of yours?

3. When and how did you start doing research? Can you tell me a story about it or how you struggle in this process?

4. How often do you read research and why? What kind of publications do you read? What is your main motivation for reading research? What challenges have you confronted in reading research?

5. How often do you do research and why? What is your main motivation for doing research? What challenges have you confronted in this process?

6. Are there any critical incidents or significant others that have influenced your research practice? If so, what and who are they?

7. What do you think of the relationship between teaching and research?

8. What kinds of effects have the new appraisal reform brought to you? What do you think of the research requirements set for each professional group?

9. What do you think of those research teams initiated in your faculty last year? Have they exerted the expected functions?

10. What do you think of the research atmosphere in your College English Unit? Would you like to do research individually or cooperate with others?

Keywords: research engagement, college English teachers, research culture, teaching-research nexus, teacher professional development

Citation: Ni H (2024) “I am strong in will but weak in action”: college English teachers’ research engagement in a Chinese regional university. Front. Educ. 9:1397786. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1397786

Edited by:

Thiyagu K., Central University of Kerala, IndiaReviewed by:

Olusiji Lasekan, Temuco Catholic University, ChileElena Mirela Samfira, University of Life Sciences “King Mihai I” from Timisoara, Romania

Copyright © 2024 Ni. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hui Ni, bmlodWlAaGV6ZXUuZWR1LmNu

Hui Ni

Hui Ni