- Department of Education and Agricultural Sciences and the Department of Educational Practice and Research, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, United States

This paper examines the transformative potential of integrating humanities into STEM education using interdisciplinary approaches, AI, and Model Eliciting Activities (MEAs). The integration is motivated by the increasing complexity of global challenges, such as climate change, which demand solutions that extend beyond traditional STEM boundaries and incorporate ethical, cultural, and societal considerations. This study profiles a multi-year, NSF-funded project focused on enhancing STEM literacy among underrepresented minority students through agricultural sciences-based MEAs that address key societal challenges in health, energy, urban green spaces, and food security. The paper details the curriculum’s design principles, emphasizing real-world, culturally relevant contexts. Results indicate that while quantitative measures show limited significant changes in interest and motivation, qualitative findings highlight increased student engagement, especially regarding real-world issues. The study underscores the importance of structural and interactional components, such as culturally relevant pedagogy, for successful curriculum implementation. Future research is recommended to explore broader applications of this model across diverse educational settings, aiming to refine interdisciplinary educational frameworks that equip students with technical skills and ethical awareness to navigate societal challenges responsibly. This case study provides a framework for educators seeking to implement interdisciplinary approaches that prepare students to address complex global challenges by integrating technical skills with ethical and cultural understanding.

1 Introduction

Integrating interdisciplinary approaches into curricula has become increasingly important in the rapidly evolving landscape of global education. This necessity stems from the complex challenges faced by society today, which demand solutions that transcend traditional academic boundaries (Reiter, 2017; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018). For instance, climate change is a global crisis that cannot be solved by environmental science alone; it requires understanding economics, public policy, ethics, and cultural contexts (Schipper et al., 2021). By integrating STEM education with the humanities, students can explore the multifaceted impacts of climate change, such as the ethical implications of resource distribution and the social justice issues related to vulnerable populations affected by environmental degradation. This interdisciplinary approach recognizes that the challenges of the 21st century require solutions informed by a deep understanding of cultural, social, and historical contexts (Balsamo, 2011).

The rationale behind this integration is not merely to enrich the educational experience but to prepare students to navigate and contribute to a world where technology, society, and ethical considerations are inextricably linked. For example, in healthcare, artificial intelligence (AI)-driven solutions can optimize patient care, but without ethical reasoning, these technologies might lead to inequitable access to medical resources or compromise patient privacy. An interdisciplinary approach ensures that students understand the human impact of these technological advancements and develop solutions that prioritize equity and ethical considerations. The urgent need for such an approach in education is underscored by the rapid pace of technological innovation and the growing complexity of global challenges. Traditional STEM education often lacks the broader context that enables students to understand the societal and environmental implications of their work. For example, engineers designing smart cities must consider technological efficiency and urban planning decisions’ cultural and social impacts on diverse communities. Incorporating humanities into STEM education is not just an enhancement but a necessity. It ensures that students are proficient in technical skills and equipped with the critical thinking and ethical reasoning needed to apply these skills responsibly in the real world (Bybee, 2010).

Integrating humanities into STEM education can be significantly enhanced by leveraging AI alongside model eliciting activities (MEAs). MEAs are inherently interdisciplinary, client-driven problems that help students connect across different subjects while applying mathematical concepts to real-world problems (Zawojewski et al., 2008; Hamilton et al., 2008; Lesh and Doerr, 2003). Six principles (see section II) guide the design of MEAs (Zawojewski et al., 2008). By grounding learning in real-world data, MEAs foster deep conceptual understanding and enhance students’ problem-solving abilities (Zawojewski et al., 2008; Hamilton et al., 2008; Lesh and Doerr, 2003). For instance, students might use MEAs to develop models for managing water resources in arid regions, requiring them to consider the technical aspects of water distribution and the ethical implications for local communities and ecosystems. AI brings unprecedented possibilities for personalized learning, dynamic problem-solving, and exploring complex ethical issues, making it an essential tool for interdisciplinary education (Luckin et al., 2016; Wu and Yu, 2024). When combined, AI and MEAs can offer a powerful educational approach that is intellectually stimulating, reflective, and grounded in ethical considerations.

A holistic educational approach that weaves ethical reasoning and cultural insights into STEM education is crucial for developing well-rounded individuals who can lead with empathy, innovation, and responsibility. This approach goes beyond mere knowledge acquisition, encouraging students to consider the broader impacts of their work and seek sustainable, equitable, and beneficial solutions to society. By integrating humanities with STEM, enhanced by the innovative use of AI and MEAs, educators can cultivate a generation of students skilled in technology and possess the ethical reasoning and cultural understanding necessary to use technology for the greater good. This paper profiles the work generated by a large, multi-year National Science Foundation grant-funded project. It provides a roadmap for educators seeking to implement a transformative educational model of integrating humanities and STEM education leveraged by AI and MEAs.

The case presented outlines a model for a pedagogical approach that leveraged the contexts of STEM and agricultural sciences, the humanities, and mathematical modeling to support weaving humanities into STEM education, suggesting ways to incorporate AI. The subsequent sections explore the background and rationale, the case and learning environment, a discussion, acknowledgment of constraints and limitations, and, finally, a conclusion.

2 Background and rationale for the educational activity innovation

Given the need for interdisciplinary problem-solving, MEAs were chosen as a pedagogical tool to integrate humanities into STEM education. MEAs are realistic, client-driven, inherently interdisciplinary problems requiring students to develop a mathematical model to solve a problem or represent a situation (Zawojewski et al., 2008; Hamilton et al., 2008; Lesh and Doerr, 2003). MEA pedagogical practice grew throughout the 80s and 90s in middle school as a means for mathematics education researchers to observe the development of student problem-solving competencies and the growth of mathematical cognition (Zawojewski et al., 2008; Hamilton et al., 2008; Lesh and Doerr, 2003). During the early 2000s, Diefes-Dux and colleagues introduce MEAs to post-secondary engineering education as a means of enhancing first-year engineering students’ problem-solving skills (Zawojewski et al., 2008; English, 2006, 2009; Lesh and Zawojewski, 2007).

Researchers have used MEAs in the classroom to investigate K-12 and first-year college students’ thinking and learning (Hamilton et al., 2008; Lesh and Doerr, 2003). MEAs have been used in the classroom by researchers and educational practitioners to identify highly gifted and creative students (Chamberlin and Moon, 2005; Coxbill et al., 2013; Hamilton et al., 2008). Researchers and practitioners have also used MEAs in the classroom to assess students’ working conceptual knowledge and help students develop problem-scoping skills to solve mathematical modeling problems (Clark et al., 2023; Bostic et al., 2020; English, 2006, 2009; Glancy and Moore, 2018; Hamilton et al., 2008). Moore et al. (2006) used four different MEAs to assess team effectiveness during complex mathematical modeling tasks.

2.1 Mathematical modeling briefly defined

Mathematical modeling is a type of modeling that uses mathematics to represent, mimic, or predict the behavior of real-world processes. The role of mathematization in modeling is fundamental to how students consider mathematics valuable and essential for immediate application in their everyday lives. Math modeling is crucial to learning mathematics and interdisciplinary learning across various disciplines (Lesh and Doerr, 2003). Translating a real-world problem into a predictive mathematical form is the essence of mathematical modeling. Doing so clarifies the problem by identifying the significant variables, making predictive approximations, and demonstrating a deeper understanding of the problem based on fundamental theories. Mathematical modeling can also support learning mathematics by increasing motivation, comprehension, and retention. The mathematician Henry Pollak, a strong advocate of incorporating modeling into the mathematics curriculum at all levels of education, argued that all students must learn mathematical modeling to use mathematics in their daily lives, as citizens, and in the workforce (Cirillo et al., 2016).

2.2 Artificial intelligence in education

Artificial intelligence is rapidly reshaping the pedagogical landscape, offering novel pathways to connect technological advancements with societal contexts in education. AI’s capability to adapt learning experiences to the needs of individual students presents unprecedented opportunities for personalized education, enabling a learning environment where content and pace are tailored to each learner’s strengths, weaknesses, and preferences (Luckin et al., 2016; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2019). This adaptation enhances learner engagement and promotes a more profound comprehension across various disciplines, crucially linking technology with societal implications (Luckin et al., 2016; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2019). AI’s application in the classroom extends to dynamic problem-solving and exploring complex ethical scenarios, making it an invaluable resource for interdisciplinary education. AI-driven platforms can simulate real-world problems, create virtual labs, and present scenario-based learning experiences that challenge students to apply interdisciplinary knowledge to solve pressing issues. This immersive approach develops technical skills and cultivates critical thinking, ethical reasoning, and an appreciation for the societal dimensions of technological innovations (Luckin et al., 2016; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2019). Integrating AI into teaching and learning processes enables educators to prepare students to be proficient in technology and the critical and ethical thinking skills necessary to responsibly navigate the challenges and opportunities of the digital age (Luckin et al., 2016; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2019). AI enhances problem-solving capabilities in the classroom by providing tools that foster an environment of inquiry and innovation (Luckin et al., 2016; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2019; Lin et al., 2023). Using intelligent tutoring systems, AI can offer personalized guidance and feedback, enabling students to navigate complex problem sets and conceptual difficulties with greater autonomy (Luckin et al., 2016; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2019; Lin et al., 2023). These systems adapt to the learner’s progress in real-time, presenting challenges optimally aligned with their current skill level and learning goals (Koedinger and Corbett, 2006).

Furthermore, AI can analyze vast datasets to identify patterns and insights imperceptible to the human eye, offering students novel perspectives and strategies for tackling problems (Baker and Siemens, 2014). This capability enriches the problem-solving process and encourages a mindset of exploration and experimentation (Dede, 2009). By leveraging AI’s analytical prowess, educators can inspire a deeper engagement with the material, motivating students to push the boundaries of their understanding and apply their knowledge in innovative ways. The result is a learning experience about finding the correct answers and cultivating the skills and creativity necessary to navigate an increasingly complex world.

Artificial intelligence integration in education, particularly through chatbot use, has shown significant promise in enhancing educational outcomes, as evidenced by recent research studies. A notable example is the meta-analysis conducted by Wu and Yu (2024), which provides compelling evidence of the educational gains achievable through chatbot utilization, highlighting substantial effects on learning. This aligns with the findings of Rahman and Watanobe (2023), who emphasized AI’s potential to benefit teachers and students by augmenting the educational process. Furthermore, Wollny et al. (2021) contribute to the growing body of literature by demonstrating that AI use not only improves student skills and motivation but also leads to noteworthy improvements in learning outcomes. These studies underscore the importance of AI chatbots in the educational sector, suggesting that educators should consider how best to leverage this technology to maximize its benefits. The implications of such research are profound, urging educators to reflect on and integrate AI tools strategically within their pedagogical practices to enhance the quality of education and student engagement.

2.3 Humanities and STEM education

Integrating humanities into the STEM educational framework represents a paradigm shift toward a more rounded and ethically grounded approach to learning. Humanities, encompassing various disciplines such as literature, history, philosophy, and arts, offer profound insights into human experience, culture, values, and ethical reasoning. When woven into STEM education, the humanities enrich the learning experience by grounding technological and scientific advancements within a broader societal and ethical context. This interdisciplinary approach facilitates the development of critical thinking, ethical reasoning, and a deeper understanding of the human condition, which are essential for addressing the complex challenges of today’s technology-driven world (Balsamo, 2011; Bybee, 2010; National Research Council and Mathematics Learning Study Committee, 2001). Historically, STEM fields have been perceived as distinct from the humanities, focusing primarily on technical proficiency and empirical inquiry. However, as technological advancements increasingly impact every aspect of society, the need for a holistic educational model that prepares students to think critically about these advancements’ ethical implications and societal impacts has become apparent. Humanities disciplines play a crucial role in this context by providing the tools to critically analyze historical trends, cultural differences, and ethical dilemmas, thereby preparing students to navigate and contribute to a world where technology, society, and ethical considerations are inextricably linked (Balsamo, 2011; National Research Council and Mathematics Learning Study Committee, 2001). By integrating humanities into STEM education, students are equipped with technical skills and the ability to consider the broader impacts of their work, fostering a generation of professionals who are as committed to ethical and societal well-being as they are to innovation and progress.

3 The pedagogical framework

3.1 MEA design

Six principles guide the design of MEAs (Zawojewski et al., 2008; Hamilton et al., 2008; Lesh and Doerr, 2003). These design principles require that all MEAs include: (1) the reality principle which requires the activity to be positioned in a realistic context where students are encouraged to make sense of the problem or situation based on extensions of their own personal knowledge and experiences; (2) self-assessment which ensures that the statement of the problem contains the criteria for appropriate self-assessment of alternative solutions; (3) a simple prototype ensures that the problem or situation is as simple as possible while ensuring the need for a significant model; (4) the model construction principle ensures the activity requires constructing, explaining, manipulating, predicting, or controlling a significant structural system; (5) the model generalization principle ask is the model sharable and reusable, and (6) model documentation ensures that the students are required to create some form of documentation that will reveal explicitly how they are thinking about the problem (Hamilton et al., 2008).

3.2 The guiding standards

The Common Core State Standards (CCSS) and the Standards for Mathematical Practice (SMP) are two components of a comprehensive framework designed to improve educational outcomes in the United States, particularly in mathematics education (Common Core State Standards Initiative, 2024). These standards worked together to ensure students gained specific mathematical content knowledge and developed critical thinking, problem-solving skills, and a deep understanding of mathematical concepts. The SMP describes eight practices that educators should develop in their students, including problem-solving, reasoning abstractly and quantitatively, constructing viable arguments, modeling with mathematics, using appropriate tools strategically, attending to precision, making use of structure, and expressing regularity in repeated reasoning. While the CCSS focuses on the “what” of mathematics, the SMP focuses on the “how” of mathematics. The CCSS lays the foundation for what students need to know, while the SMP shapes how students approach, understand, and apply their mathematical knowledge.

3.3 The learning objectives

The MEAs were used as tools to promote contextualized learning and conceptual understanding by eliciting students to (a) interpret data meaningfully to draw accurate conclusions and insights, (b) develop mathematical models utilizing multiple representations to describe and predict real-world phenomena, (c) enhance critical thinking skills by engaging in the iterative engineering problem-solving design process, (d) collaborate effectively with peers to solve complex problems through teamwork and shared expertise, (e) improve written and verbal reporting skills by practicing clear and effective communication of ideas and results, and (f) build self-efficacy in solving real-world problems through hands-on experience and reflective practice.

4 The learning environment

4.1 The case study overview

This case study profiles the work carried out under a multi-year project funded by the National Science Foundation, Enhancing Minority Middle School Students’ Knowledge, Literacy, and Motivation in STEM Using Contextual Agricultural Life Sciences (AgLS) Learning Experiences. The project aimed to design, develop, and field-test novel integrated STEM learning experiences using agricultural sciences (AgS) contexts. The project leverages the integration of STEM and AgS within a humanities context to design, develop, and implement novel MEAs (Clark et al., 2023). Seven AgS MEAs were designed, developed, and field-tested during three academic years as part of the larger project. This innovative curriculum aimed to (a) increase the number of marginalized elementary school students prepared for secondary STEM courses and postsecondary majors in STEM and (b) contribute to a culturally relevant integrated STEM curriculum. The AgS MEAs were standards-based, grounded in culturally relevant pedagogy principles (Ladson-Billings, 2009), and contextualized through community connections and local STEM industry partnerships.

Culturally relevant pedagogy “empowers students intellectually, socially, emotionally, and politically using cultural referents to impart knowledge, skills, and attitudes” (Ladson-Billings, 2009, p. 16–17). A culturally relevant pedagogy framework encompasses three tenets: academic achievement, cultural competence, and sociopolitical consciousness (Ladson-Billings, 2009). Furthermore, research indicates that culturally relevant pedagogy is vital in facilitating marginalized students’ success in mathematics and science in K-12 education (Lesh et al., 2000; Lesh and Harel, 2003; Lesh and Doerr, 2003). Culturally relevant pedagogy was especially critical when developing students’ awareness of and connection to STEM careers and local community problems. Culturally relevant pedagogy was incorporated into the design, development, and implementation of the AgS MEAs through the three C’s of culturally relevant pedagogy. The three C’s are defined as culture, community, and career. Agricultural sciences MEAs were the first MEAs to incorporate the three C’s into MEA design, development, and implementation (Clark et al., 2023; Bostic et al., 2020). The three Cs approach to culturally relevant pedagogy was carried out throughout the AgLS MEA classroom instruction by providing teacher development sessions before and after each AgLS MEA implementation. The teacher development sessions increased teachers’ knowledge, skill, and confidence in facilitating cultural and community-relevant learning activities tied to real-world situations. Providing teachers with resources to partner with local community organizations, local colleges and universities, and local STEM networks empowered teachers with the confidence to implement culturally relevant pedagogy in their classrooms.

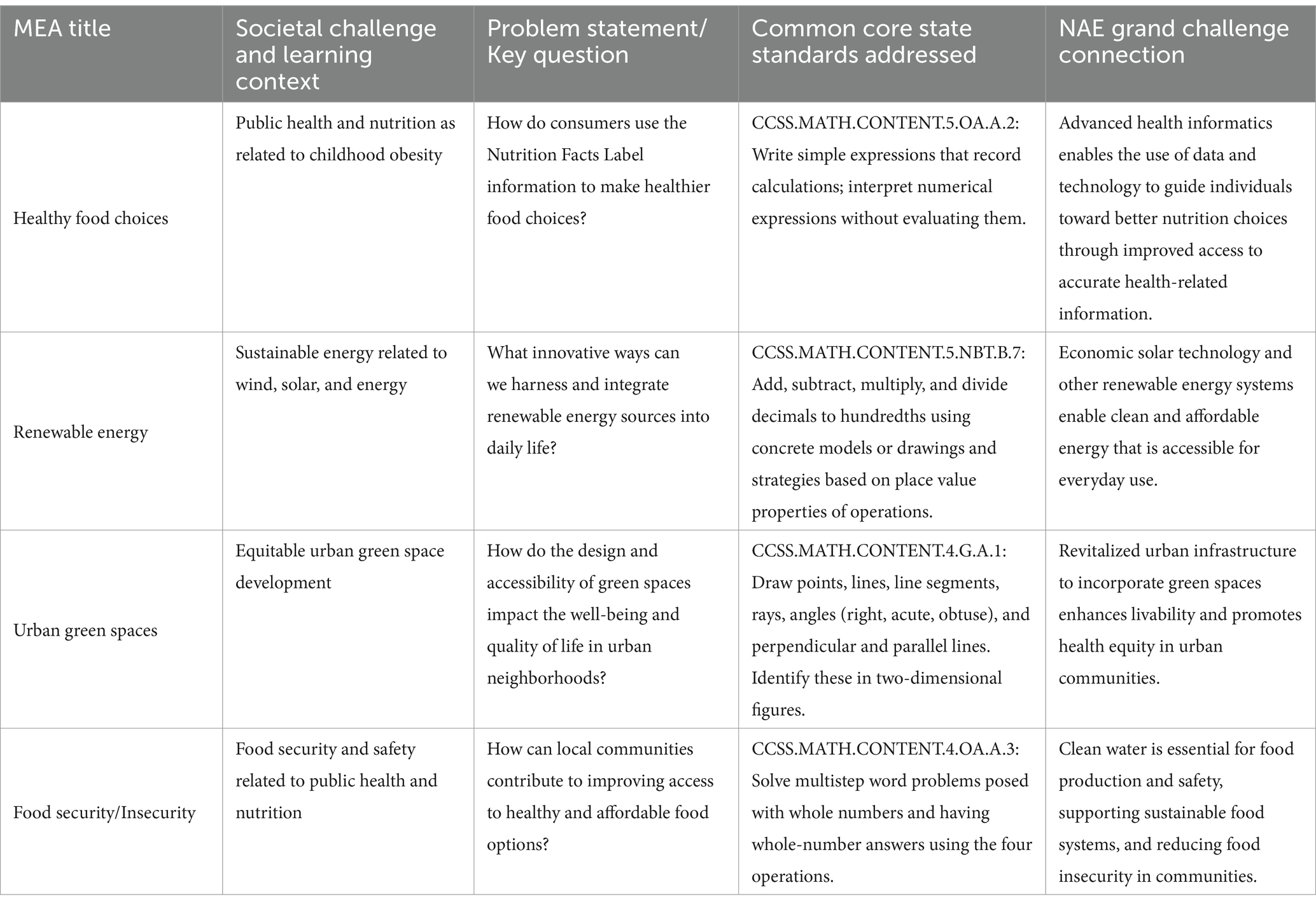

The agricultural sciences MEAs were the first-ever developed AgS-focused MEAs. The AgS MEAs were designed, developed, and field-tested using an iterative, cyclical design approach (Clark et al., 2023). Each AgS MEA underwent an engineering design process of implementation, testing, and redesign process (Clark et al., 2023; Bostic et al., 2020). All AgS MEAs adhered to the models and modeling perspective and associative principles (Clark, 2021; Lesh and Doerr, 2003) and aligned with both Common Core State Standards Initiative (CCSSI) (2010) and Next Generation Science Standards Lead States (2013). The AgS MEA topics addressed four major societal challenges: (1) health and human diet, (2) food security/insecurity, (3) alternative energy, and (4) equitable green space utilization. The AgS-related societal challenges facilitated myriad solutions requiring students to reflect on their everyday lives to connect challenges and resources in students’ local communities. The topics of AgS also provided a vibrant venue for real-world contexts to engage students in problem-solving that reflected culturally relevant pedagogy. Content experts guided the AgS MEA curriculum to ensure that the curriculum was culturally relevant, connected to the community, aligned with state content standards, and developmentally appropriate for elementary school students.

These MEAs aim to address real-world problems, drawing on the grand challenges identified by the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) that are crucial for sustaining life on Earth in the 21st century (Clark et al., 2023). The NAE challenges related to the MEAs discussed in this study include advanced health informatics, solar technology advancements, urban infrastructure restoration, and sustainable clean water sources for a global population projected to exceed 9 billion by 2050. The grand challenges necessitate solutions that transcend traditional STEM disciplines, requiring the integration of broader societal and ethical contexts. Disciplines such as literature, history, philosophy, and the arts become vital in addressing these complex issues, providing insights into human values, culture, and ethics. The MEAs developed emphasize this interdisciplinary approach, focusing on societal problems related to food science, environmental science, engineering design, and public health. By embedding these challenges within a humanities framework, the MEAs highlight the importance of understanding human values and cultural contexts in solving complex societal challenges. These MEAs are not only standards-based but also grounded in the principles of culturally relevant pedagogy (Clark, 2021). The MEAs are contextualized through connections to local communities and partnerships with local STEM industries. This approach ensures that the learning experiences are academically rigorous, meaningful, and relevant to the students’ lives and communities. Table 1 lists the four MEA topic area titles, societal challenges, key questions addressed, Common Core State Standard potentially addressed, and the connection of NAE grand challenge.

Table 1. Model eliciting activities (MEAs) aligned with societal challenges and educational standards.

4.2 Setting

The MEAs were implemented in a primary school with an environmental focus (a magnet school), serving students aged 5–12 in a large urban district in the central United States. According to the US Department of Education, magnet schools offer distinctive educational programs emphasizing mathematics, science, technology, visual and performing arts, or humanities (U.S. Department of Education, 2004). The school aimed to integrate environmental and AgS into an elementary education curriculum. To help achieve this mission, researchers associated with the project supported the school in preparing for and receiving STEM certification through the Indiana Department of Education in 2020. The school’s student body was 85% Black/African American, 8% Hispanic/Latinx, 6% White/Caucasian, and 1% Asian American, with 61% receiving free or reduced lunch assistance. It is important to note that a long-term goal of the larger project was to increase the number of underrepresented middle school students prepared for advanced-level secondary STEM courses. Mentioning the racial and ethnic makeup of the school provides a basis for broader discussions on how educational practices can be adapted or understood in different international contexts, recognizing the diverse populations served globally.

4.3 Participants

The study involved 67 students (n = 67), 31 in fifth grade (46.3%) and 36 in sixth grade (53.7%). The participating students were distributed across four classrooms: fifth- and sixth-graders. Four teachers participated in the field testing of the MEAs over two academic years. The teachers had varying levels of experience, ranging from two to over 15 years, and their subject expertise included English language arts (ELA), mathematics, and science. One week before each MEA implementation, teacher participants attended a 45-min development session. The goal of the development sessions was to (a) conduct an explanatory demonstration of the MEA, (b) engage teachers in a reflective discussion about the MEA implementation, and (c) engage teachers in conversations about students’ motivation, culturally relevant pedagogy, community engagement, and STEM career exploration. Teacher participants received a stipend and instructional supplies for participating in the study.

4.4 The intervention

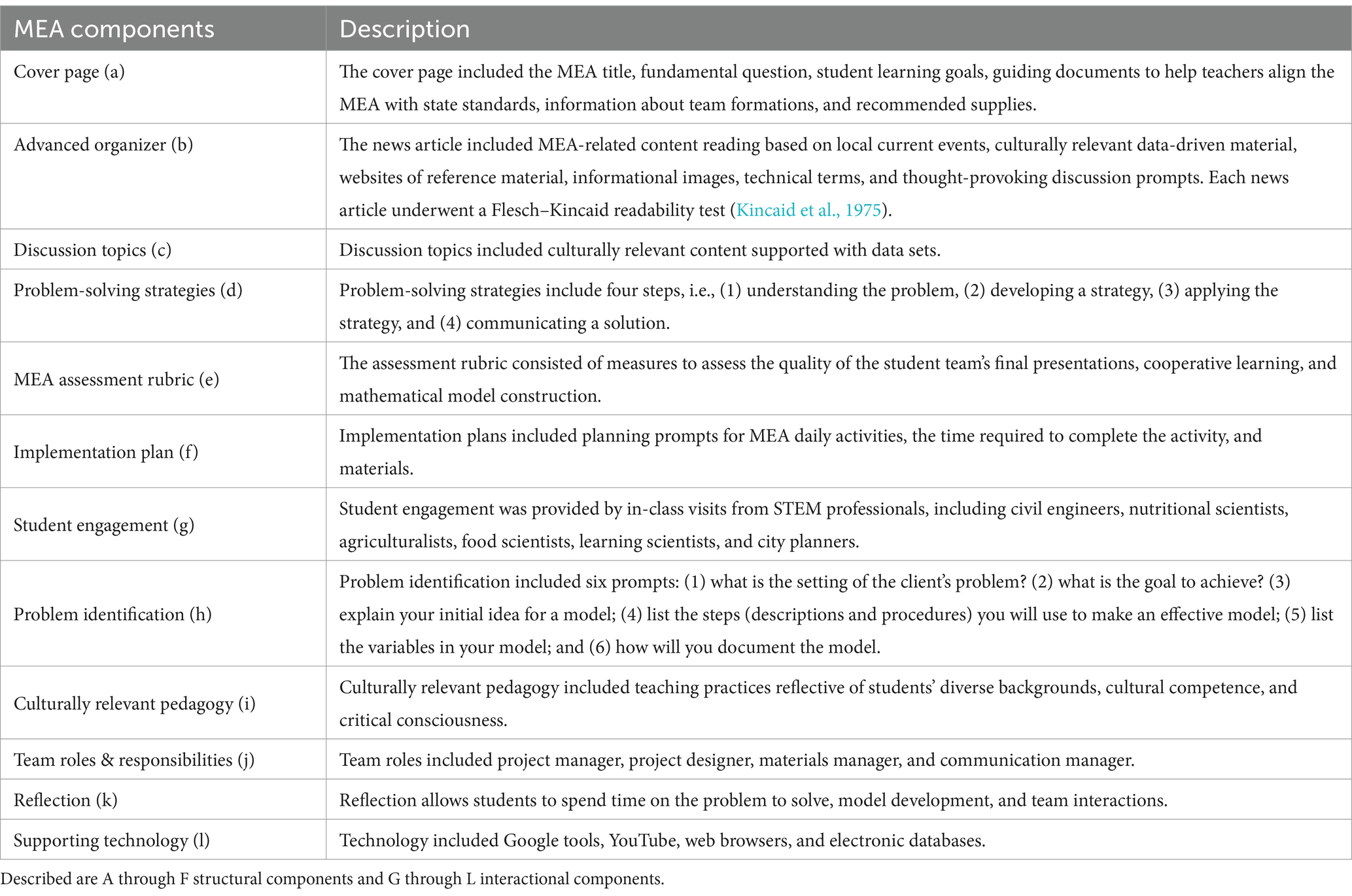

The AgS MEAs were the first-ever developed AgS-focused MEAs. The AgS MEAs were designed, developed, and field-tested using an iterative, cyclical design approach (Clark, 2021; Clark et al., 2023). Each MEA underwent an engineering design process of implementation, testing, and redesign (Clark, 2021; Clark et al., 2023). All MEAs adhered to the models and modeling perspective and associative principles (Lesh and Doerr, 2003) and aligned with both Common Core State Standards Initiative (CCSSI) (2010) and Next Generation Science Standards Lead States (2013). The MEA topics addressed four major societal challenges: (1) health and human diet, (2) food security/insecurity, (3) alternative energy, and (4) equitable green spaces. The AgS-related-related societal challenges facilitated a myriad of solutions requiring students to reflect on their everyday lives to connect challenges and resources in students’ local communities. The AgS topics also provided a vibrant venue for real-world contexts to engage students in problem-solving that reflected culturally relevant pedagogy. Content experts guided the MEA development to ensure the curriculum was culturally relevant, connected to the community, aligned with state content standards, and developmentally appropriate for elementary school students. The structural and interactional components of the MEAs are described in Table 2.

4.5 Methods and procedures

The case presented here reports two interrelated studies (Clark, 2021; Clark et al., 2023) utilizing qualitative and quantitative research methods. In what follows, each study’s processes and procedures are discussed.

4.6 Study 1

Guided by Self-Determination Theory (SDT), study 1 focused on identifying the contextual factors that either facilitate or hinder students’ motivation to engage with and learn STEM subjects (Deci and Ryan, 1982, 2012; Niemiec and Ryan, 2009; Ryan and Deci, 2000). SDT posits that motivation, particularly intrinsic motivation, can be either enhanced or undermined by contextual factors (Deci and Ryan, 1982, 2012; Niemiec and Ryan, 2009; Ryan and Deci, 2000). Intrinsic motivation, the innate drive to engage in activities for their inherent satisfaction, is central to fostering sustained engagement and learning (Deci and Ryan, 1982; Ryan and Deci, 2000). SDT identifies three basic psychological needs that are essential for stimulating and sustaining intrinsic motivation, especially in educational settings (Niemiec and Ryan, 2009; Ryan and Deci, 2000): competence (Harter, 1978), relatedness (Baumeister and Leary, 1995; Reis, 1994), and autonomy (Deci and Ryan, 2010; DeCharms, 1972). Competence refers to students’ confidence in their ability to master content, relatedness pertains to their sense of belonging and connection with others, and autonomy involves the perception of having control over one’s learning activities. When these needs are unmet, students are likely to experience disengagement and adverse learning outcomes (Niemiec and Ryan, 2009). Conversely, when these needs are supported, they are associated with increased motivation, academic engagement, and improved learning outcomes (Niemiec and Ryan, 2009).

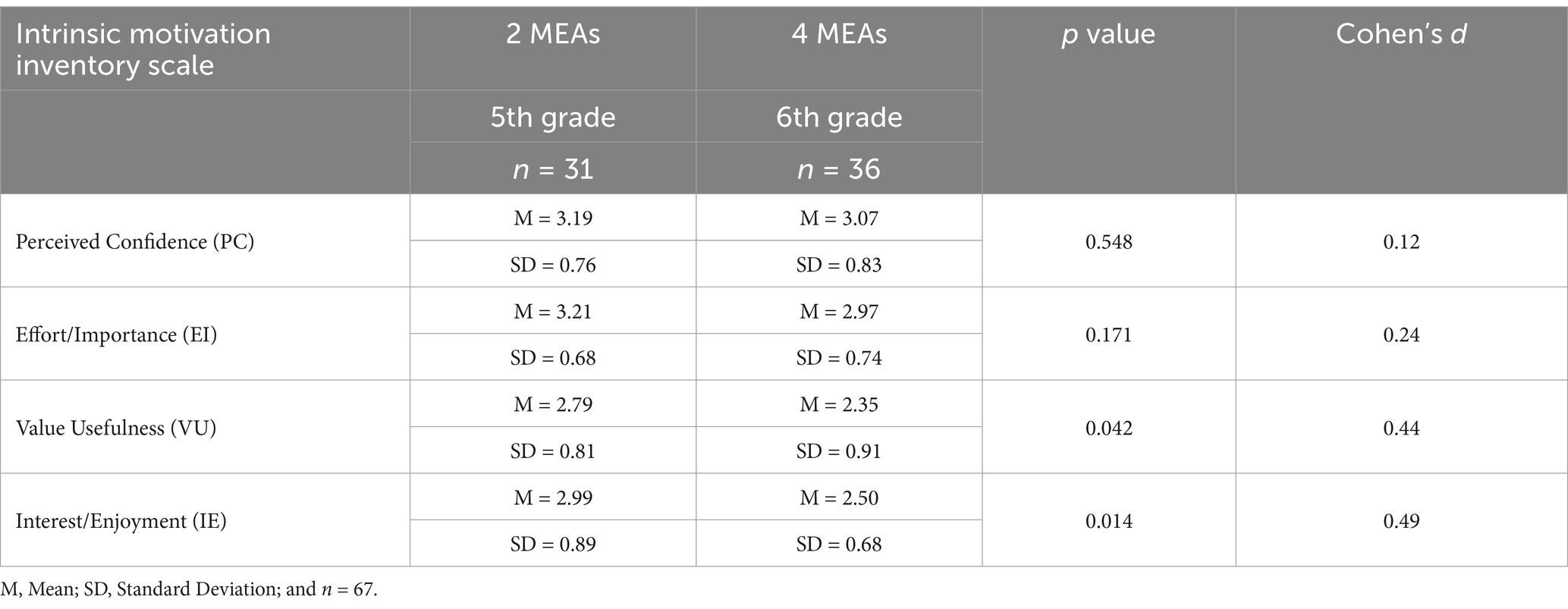

The primary research question guiding the study was: Does student motivation to engage and learn in STEM activities change after completing MEAs? Two established instruments were adapted for this study, i.e., the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI; Deci and Ryan, 1982; Ryan et al., 1991) and the Agricultural, Food, and Natural Resources (AFNR) instrument (Scherer, 2016). Both instruments were assessed using the Flesch–Kincaid readability test to ensure their appropriateness for the targeted grade level (Kincaid et al., 1975).

The IMI, which evaluates students’ subjective experiences related to specific activities, was modified to include four subscales: perceived competence (PC), effort/importance (EI), value/usefulness (VU), and interest/enjoyment (IE). These subscales measured students’ interest and motivation for participating in STEM activities. The modified IMI questionnaire consisted of 21 items. Five items were included in each PC, EI, and VU subscale, while six comprised the IE subscale. Responses were rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = Not at all agree to 4 = Mostly agree, reflecting the extent of agreement with each statement. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for internal consistency were 0.87, 0.79, 0.87, and 0.71, respectively.

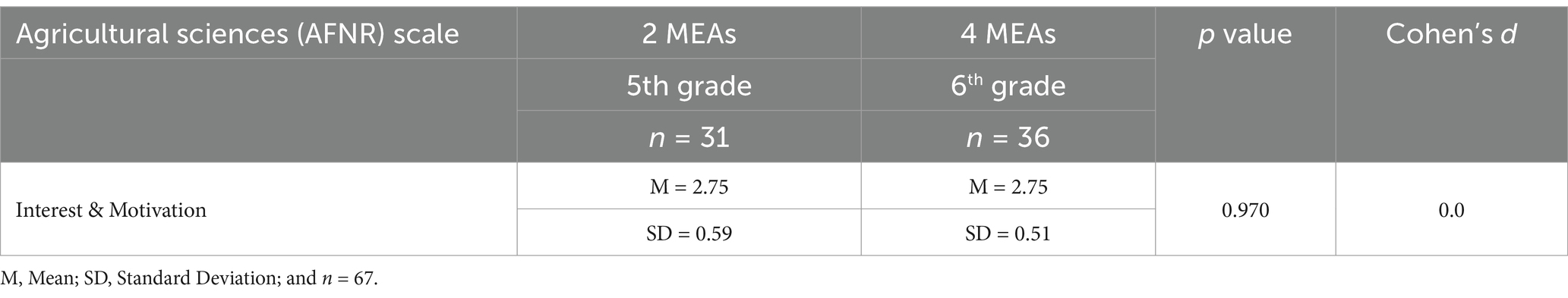

The AFNR instrument, originally developed to assess youth interest and motivation in learning agricultural content, was similarly modified to focus on interest and motivation in agricultural sciences. The resulting questionnaire also contained 21 items, with responses on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = Strongly disagree to 4 = Strongly agree, indicating participants’ agreement with each statement. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for internal consistency was 0.89.

Demographic and questionnaire data were collected from the fifth and sixth grade classrooms before the MEAs were implemented during each of the two academic school years. IMI data were collected one day after the completion of the MEA implementation for each of the two academic school years. Two graduate student researchers administered each questionnaire. While one graduate student researcher distributed the questionnaire to each student, the other researcher explained the questionnaire to the student participants, question by question, to ensure that students understood each question.

Data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS©) version 20. First, reliability coefficient scores were calculated for the four scales. The four scales measuring interest and motivation were perceived confidence (PC), effort/importance (EI), value usefulness (VU), and interest/enjoyment (IE). Second, frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations were calculated for the four IMI scales. Third, independent t-tests were conducted to assess students’ interest and motivation differences across all four scales between students who experienced two MEAs (fifth graders) versus four MEAs (sixth graders). The assumption of normality was examined for each t-test and met.

The primary research question sought to determine student motivation in STEM learning experiences between students who experienced two MEAs [fifth graders versus four MEAs (sixth graders)]. The summated means and standard deviations were calculated for participants’ responses to the IMI scale, items measuring perceived confidence (PC), effort/importance (EI), value usefulness (VU), and interest/enjoyment (IE). Table 3 displays the summated means and standard deviations along with the independent t-test scores for each of the four constructs measured (i.e., PC, EI, VU, and IE).

Results of the independent t-tests indicated no significant difference in mean scores for Perceived Confidence [fifth grade mean = 3.19, SD = 0.76 and sixth grade mean = 3.07, SD = 0.83; t(65) = −0.605, p ≥ 0.05]. The Perceived Confidence scale revealed a trivial effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.12). There was no significant difference in mean scores for Effort/Importance [fifth grade mean = 3.21, SD = 0.68 and sixth grade mean = 2.97, SD = 0.74; t(65) = −1.37, p ≥ 0.05]. The Effort/Importance scale revealed a small effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.24). However, there was a significant difference in mean scores for Value Usefulness [fifth grade mean = 2.79, SD = 0.81 and sixth grade mean = 2.35, SD = 0.91; t(65) = −2.06, p ≤ 0.05]. The Value Usefulness scale revealed a moderate effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.44). There was also a significant difference in mean scores for Interest/Enjoyment [fifth grade mean = 2.99, SD = 0.89 and sixth grade mean = 2.50, SD = 0.68; t(65) = −2.57, p ≤ 0.05]. The Interest/Enjoyment scale revealed a moderate effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.49).

Results of the independent t-test indicated no significant difference in mean scores for interest and motivation in agricultural sciences [fifth grade mean score = 2.75, SD = 0.59 and sixth grade mean score = 2.75, SD = 0.51; t(65) = 0.037, p ≥ 0.05]. The agricultural sciences (AFNR) questionnaire scale revealed a trivial effect size, Cohen’s d = 0.0. Table 4 displays the summated scores and t-test results.

4.7 Study 2

The second study employed the Innovation Implementation Framework (Gale et al., 2020; Century and Cassata, 2014, 2016; Century et al., 2012; Clark et al., 2023) to explore the critical structural and interactional components necessary for effectively implementing STEM, agricultural sciences MEAs.

The guiding research question for this study was: What are the structural and interactional components of an integrated STEM curriculum? The Innovation Implementation Framework (Gale et al., 2020; Century and Cassata, 2014, 2016; Century et al., 2012) guided the semi-structured interviews and focus groups conducted to capture teachers’ discourse on their experiences with implementing the MEAs. The Innovation Implementation framework identifies two primary categories of components essential for contextualized curriculum implementation (Century and Cassata, 2014): structural and interactional. Structural components refer to the crucial organizational elements for curriculum implementation, such as design and support systems. Interactional components involve the behaviors, interactions, and practices during the curriculum’s enactment. These components focus on the pedagogical actions expected of teachers and the engagement activities designed for students within the curriculum intervention (Century and Cassata, 2014).

Results from study 2 identified six structural and six interactional implementation components. The structural components identified included (a) a cover page, (b) an advanced organizer/news article, (c) discussion topics, (d) problem-solving strategies, (e) an MEA assessment rubric, and (f) an implementation plan. The interactional components consist of (g) student mentorship, (h) problem identification, (i) culturally relevant pedagogy, (j) team roles and responsibilities, (k) reflection, and (l) supporting technology. Table 2 details the structural and interactional components identified as critical for MEA implementation when integrating STEM and humanities.

5 Discussion

The case study discussed in this paper highlights the transformative potential of integrating humanities into STEM education through the strategic use of mathematical modeling and AI. This approach is not merely an enhancement of traditional educational models but a necessary evolution to meet the demands of the 21st century. By leveraging interdisciplinary approaches, particularly the integration of humanities into STEM, students can develop a more comprehensive understanding of the complex challenges they will face in their careers and as global citizens.

The qualitative results from Study 2 reveal the depth of engagement and critical thinking that this interdisciplinary model fosters. Through semi-structured interviews and focus groups, teachers reported that students engaged meaningfully with real-world problems, particularly in MEAs focused on agricultural and environmental sciences. These topics, embedded with cultural and ethical considerations, prompted students to consider the social implications of their technical work. For instance, during the MEA on renewable energy, students explored the broader impacts of clean energy solutions, including accessibility issues for diverse communities. Teachers noted that these discussions encouraged students to view STEM as a means to address societal problems, fostering a sense of responsibility and purpose in their learning.

Moreover, the qualitative data revealed that culturally relevant pedagogy was essential for increasing student motivation and ownership over their learning. By grounding MEAs in local, community-relevant contexts, the curriculum allowed students to see the relevance of STEM to their own lives and communities. The culturally relevant pedagogy framework centered around the Three Cs (culture, community, and career) was particularly effective in fostering a sense of belonging and engagement. Teachers observed that students were more motivated and proactive in activities that connected directly to their communities, especially in MEAs focused on food security and equitable green spaces. This insight aligns with Self-Determination Theory (SDT), as students experienced increased autonomy, competence, and relatedness, critical to sustained engagement and learning.

The supporting technologies used in the case study, such as Google tools, YouTube, various web browsers, and electronic databases, provided students and teachers with essential resources to access, share, and organize information. These tools were foundational in facilitating the research, collaboration, and documentation processes within MEAs. However, the success of these technologies points to the significant potential for incorporating more advanced AI-driven tools into future MEA implementations. For example, adaptive feedback systems and scenario-based simulations could allow students to explore complex ethical scenarios at their own pace, fostering critical thinking and ethical reasoning. Such AI-driven tools could enhance the curriculum’s ability to tailor learning experiences to individual needs and create immersive, ethically focused problem-solving scenarios, further supporting this model’s interdisciplinary, human-centered learning objectives.

Teachers also highlighted several structural and interactional components critical for successful MEA implementation. Structural elements, such as advanced organizers and assessment rubrics, provided a clear framework for interdisciplinary problem-solving. Interactional components, including mentorship and structured problem identification, encouraged collaboration and reflective thinking. Teachers emphasized that these components supported academic learning and facilitated social–emotional growth by promoting empathy, teamwork, and problem-solving skills. The integration of AI tools, when possible, could add further depth to this approach by enabling dynamic, personalized learning environments. AI-driven platforms could offer real-time feedback and adjust to each student’s unique pace and understanding, allowing deeper engagement with ethical and cultural considerations.

The quantitative results from Study 1 showed limited statistically significant changes in student interest and motivation. These findings indicate the need for alternative assessment tools to capture shifts in attitudes, perceptions, and critical thinking that traditional metrics may not adequately reflect.

In summary, the qualitative data from Study 2 affirm that integrating humanities into STEM education through MEAs and AI is a feasible and impactful model, especially when culturally relevant contexts and ethical considerations are embedded into the curriculum. This approach cultivates technically proficient students who are also empathetic, ethically aware, and prepared to address today’s world’s complex, interdisciplinary challenges.

6 Acknowledgment of constraints

This study acknowledges several constraints that could impact the generalizability and interpretation of its findings. Firstly, the limited duration of the intervention and the relatively small sample size, primarily drawn from a single educational setting, may not fully represent the diversity of educational landscapes. This limitation raises concerns about how the findings can be applied to other contexts, particularly those with different demographic, cultural, or socioeconomic characteristics. Additionally, the quantitative measures used to assess changes in student interest and motivation may not fully capture the depth and complexity of the interdisciplinary impact. This reliance on quantitative data might overlook subtle shifts in student perceptions and engagement that could be better understood through qualitative approaches. Potential biases, such as the influence of the specific school environment or the teachers’ lack of familiarity with interdisciplinary methods, could also affect the outcomes and should be considered when interpreting the results.

Future research should address these limitations by conducting longitudinal studies with larger, more diverse demographic samples to understand better the long-term effects and broader applicability of integrating humanities into STEM education through AI and MEAs. Such studies could also explore potential biases or confounding variables, such as variations in technological access, teacher training, and curriculum adaptation, which could influence the effectiveness of this educational model. By examining these factors, future research can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the challenges and opportunities associated with scaling this approach across different educational settings and age groups, ultimately contributing to more equitable and effective implementation.

7 Conclusion

In conclusion, the integration of humanities into STEM education, supported by mathematical modeling and AI, represents a powerful approach to developing well-rounded individuals capable of addressing the complex challenges of the modern world. This interdisciplinary model prepares students to think critically and ethically about the impact of technology on society, ensuring that they are proficient in technical skills and equipped with the cultural and ethical awareness necessary to use these skills responsibly. As educators seek to implement this model, it will be essential to continue refining both the pedagogical frameworks and assessment methods to realize the full potential of this approach.

The integration of Humanities into STEM education, supported by AI and MEAs, represents a pivotal advancement in educational strategies to prepare students for the complexities of the contemporary world. The case presented here highlights the profound benefits of such an interdisciplinary approach, which enhances academic performance and cultivates critical thinking, ethical reasoning, and a broader understanding of societal impacts. By fostering these skills, the curriculum equips students to navigate and contribute thoughtfully to a world where technology, society, and ethical considerations are increasingly intertwined. Despite its challenges, the successful implementation of this educational model underscores the urgent need for education systems to evolve, reflecting the multifaceted nature of modern societal challenges.

Educators, policymakers, and stakeholders can consider the practical implications, objectives, and lessons learned from the case presented here to facilitate the widespread adoption of interdisciplinary education. Integrating AI and MEAs into the curriculum personalizes learning experiences and brings to light the potential of technology to enhance educational outcomes across disciplines. As we continue to explore and refine these approaches, the goal remains clear: to develop an educational framework that not only imparts knowledge but also instills a sense of responsibility, empathy, and ethical awareness, preparing students to make meaningful contributions to society and to address global challenges with innovative and responsible solutions.

Data availability statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are not publicly available due to confidentiality agreements/legal restrictions, further inquiries can be directed to the author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Purdue University Institutional Review Board (IRB). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants or participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

QC: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Baker, R., and Siemens, G. (2014). Learning analytics and educational data mining. Cambridge Handbook of the Leaning Sciences, 253–272. doi: 10.1017/9781108888295.016

Balsamo, A. (2011). Designing Culture: The Technological Imagination at Work. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press.

Baumeister, R. F., and Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 117:497. doi: 10.4324/9781351153683-3

Bostic, J., Clark, Q. M., Vo, T., Esters, L. T., and Knobloch, N. A. (2020). A design process for developing agricultural life science-focused model eliciting activities. Sch. Sci. Math. J. 121, 13–24. doi: 10.1111/ssm.12444

Century, J., and Cassata, A. (2016). Implementation research. Rev. Res. Educ. 40, 169–215. doi: 10.3102/0091732X16665332

Century, J., and Cassata, A. (2014). “Conceptual foundations for measuring the implementation of educational innovations” in Treatment Integrity: A Foundation for Evidence-Based Practice in Applied Psychology. eds. L. M. Hagermoser Sanetti and T. R. Kratochwill (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 81–108.

Century, J., Cassata, A., Rudnick, M., and Freeman, C. (2012). Measuring enactment of innovations and the factors that affect implementation and sustainability: moving toward common language and shared conceptual understanding. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 39, 343–361. doi: 10.1007/s11414-012-9287-x

Chamberlin, S. A., and Moon, S. M. (2005). Model-eliciting activities as a tool to develop and identify creatively gifted mathematicians. J. Second. Gift. Educ. 17, 37–47. doi: 10.4219/jsge-2005-393

Cirillo, M., Pelesko, J., Felton-Koestler, M., and Rubel, L. (2016). “Perspectives on modeling in school mathematics” in Annual Perspectives in Mathematics Education (APME) 2016: Mathematics Modeling and Modeling with Mathematics, 249–261.

Clark, Q. M. (2021). Design, implementation, and assessment of mathematical modeling of agriculturally based stem activities at the elementary grade level. Doctoral dissertation. Purdue University.

Clark, Q. M., Capobianco, B. M., and Esters, L. T. (2023). Identification of essential integrated STEM curriculum implementation components. J. Agric. Educ. 64, 43–61. doi: 10.5032/jae.v64i3.60

Common Core State Standards Initiative. (2010). Common core standards for mathematics. Available online at: https://learning.ccsso.org/common-core-state-standards-initiative

Common Core State Standards Initiative. (2024). Common core state standards for mathematics. Washington, DC: National Governors Association Center for Best Practices and Council of Chief State School Officers. Available online at: https://www.thecorestandards.org/

Coxbill, E., Chamberlin, S. A., and Weatherford, J. (2013). Using model-eliciting activities as a tool to identify and develop mathematically creative students. J. Educ. Gift. 36, 176–197. doi: 10.1177/0162353213480433

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (1982). Intrinsic motivation to teach: Possibilities and obstacles in our colleges and universities. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 1982, 27–35. doi: 10.1002/tl.37219821005

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2010). Intrinsic Motivation. The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology, 1–2. doi: 10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0467

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2012). “Self-determination theory,” in Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology. eds. P. A. M. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, and E. T. Higgins (Sage Publications Ltd), 416–436.

DeCharms, R. (1972). Personal causation training in the schools 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2, 95–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1972.tb01266.x

Dede, C. (2009). Immersive interfaces for engagement and learning. Science 323, 66–69. doi: 10.1126/science.1167311

English, L. (2006). Mathematical modeling in the primary school: Children's construction of a consumer guide. Educ. Stud. Math. 63, 303–323. doi: 10.1007/s10649-005-9013-1

English, L. (2009). Promoting interdisciplinarity through mathematical modeling. ZDM Int. J. Math. Educ. 41, 161–181. doi: 10.1007/s11858-008-0101-z

Gale, J., Alemdar, M., Lingle, J., and Newton, S. (2020). Exploring critical components of an integrated STEM curriculum: an application of the innovation implementation framework. Int. J. STEM Educ. 7:5. doi: 10.1186/s40594-020-0204-1

Glancy, M. A. W., and Moore, T. J. (2018). Model-eliciting activities to develop problem-scoping skills at different levels. Paper presentation. American Society of Engineering Education 125th Annual Meeting, Salt Lake City, UT, United States.

Hamilton, E., Lesh, R., Lester, F., and Brilleslyper, M. (2008). Model eliciting activities (MEAs) as a bridge between engineering education research and mathematics education research. Adv. Eng. Educ. 1:2.

Harter, S. (1978). Effectance motivation reconsidered: Toward a developmental model. Hum. Dev. 21, 34–64. doi: 10.1159/000271574

Kincaid, J. P., Fishburne Jr, R. P., Rogers, R. L., and Chissom, B. S. (1975). Derivation of new readability formulas (automated readability index, fog count, and Flesch reading ease formula) for navy enlisted personnel. Naval Technical Training Command Millington TN Research Branch. Retrieved from https://stars.library.ucf.edu/istlibrary/56/.

Koedinger, K. R., and Corbett, A. (2006). “Cognitive tutors: technology bringing learning sciences to the classroom” in The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences. ed. R. K. Sawyer (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press), 61–77.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2009). The Dreamkeepers: Successful Teachers of African American Children. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Lesh, R., and Doerr, H. M. (2003). Beyond Constructivism: Models and Modeling Perspectives on Mathematics Problem Solving, Learning, and Teaching. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Lesh, R., and Harel, G. (2003). Problem-solving, modeling, and local conceptual development. Math. Think. Learn. 5, 157–189. doi: 10.1080/10986065.2003.9679998

Lesh, R., Hoover, M., Hole, B., Kelly, A., and Post, T. R. (2000). “Principles for developing thought-revealing activities for students and teachers” in Research Design in Mathematics and Science Education (Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.), 591–646.

Lesh, R., and Zawojewski, J. (2007). “Problem-solving and modeling” in Second Handbook of Research on Mathematics Teaching and Learning. ed. F. K. Lester Jr. (Reston, VA: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics), 763–804.

Lin, C. C., Huang, A. Y., and Lu, O. H. (2023). Artificial intelligence in intelligent tutoring systems toward sustainable education: a systematic review. Smart Learn. Environ. 10:41. doi: 10.1186/s40561-023-00260-y

Luckin, R., Holmes, W., Griffiths, M., and Forcier, L. B. (2016). Intelligence Unleashed: An Argument for AI in Education. Strand, London: Pearson.

Moore, T. J., and Diefes-Dux, H., & Imbrie, P. K. (2006). “Assessment of team effectiveness during complex mathematical modeling tasks” in Proceedings. Frontiers in Education. 36th Annual Conference. pp. 1–6.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2018). The integration of the humanities and arts with sciences, engineering, and medicine in higher education: Branches from the same tree. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

National Research Council and Mathematics Learning Study Committee (2001). Adding it up: Helping Children Learn Mathematics. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Next Generation Science Standards Lead States (2013). Next generation science standards: For states, by states. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Niemiec, C. P., and Ryan, R. M. (2009). Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom: Applying self-determination theory to educational practice. Theory Res. Educ. 7, 133–144. doi: 10.1177/1477878509104318

Rahman, M. M., and Watanobe, Y. (2023). ChatGPT for education and research: opportunities, threats, and strategies. Appl. Sci. 13:5783. doi: 10.3390/app13095783

Reis, H. T. (1994). “Domains of experience: Investigating relationship processes from three perspectives,” in Theoretical Frameworks for Personal Relationships, 87–110. Retrieved from https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1994-97484-005.

Reiter, C. M. (2017). 21st century education: The importance of the humanities in primary education in the age of STEM. Senior thesis. Dominican University of California.

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55:68. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Ryan, R. M., Koestner, R., and Deci, E. L. (1991). Ego-involved persistence: When free-choice behavior is not intrinsically motivated. Motiv. Emot. 15, 185–205.

Scherer, A. K. (2016). High school students' motivations and views of agriculture and agricultural careers upon completion of a pre-college program (Master's thesis, Purdue University). Available online at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_theses/998

Schipper, E. L. F., Dubash, N. K., and Mulugetta, Y. (2021). Climate change research and the search for solutions: rethinking interdisciplinarity. Clim. Change 168:18. doi: 10.1007/s10584-021-03237-3

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (2019). Artificial intelligence in education: Challenges and opportunities for sustainable development. Available at: https://gcedclearinghouse.org/sites/default/files/resources/190175eng.pdf

U.S. Department of Education (2004). Office of Innovation and Improvement, Innovations in Education: Creating Successful magnet Schools Programs. Retrieved from http://www.ed.gov/admins/comm/choice/magnet/.

Wollny, S., Schneider, J., Di Mitri, D., Weidlich, J., Rittberger, M., and Drachsler, H. (2021). Are we there yet?—a systematic literature review on Chatbots in education. Front. Artificial Intellig. 4:654924. doi: 10.3389/frai.2021.654924

Wu, R., and Yu, Z. (2024). DoAIchatbots improve students learning outcomes? Evidence from a meta‐analysis. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 55, 10–33. doi: 10.1111/bjet.13334

Zawojewski, J. S., Diefes-Dux, H. A., and Bowman, K. J. (2008). Models and modeling in engineering education. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

Keywords: STEM, humanities, artificial intelligence, model-eliciting activities, mathematical modeling, ethics, interdisciplinary, personalized learning

Citation: Clark QM (2025) A pedagogical approach: toward leveraging mathematical modeling and AI to support integrating humanities into STEM education. Front. Educ. 9:1396104. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1396104

Edited by:

Diane Peters, Kettering University, United StatesReviewed by:

Mehmet Başaran, University of Gaziantep, TürkiyeYvette E. Pearson, The University of Texas at Dallas, United States

Copyright © 2025 Clark. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Quintana M. Clark, cXVpbmN5LmNsYXJrQG9yZWdvbnN0YXRlLmVkdQ==

Quintana M. Clark

Quintana M. Clark