- 1College of Professional and Continuing Education, Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 2Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Department of Educational Research, Lancaster University, Lancaster, United Kingdom

Introduction: The study explores the effectiveness of teaching English literature to Hong Kong undergraduate students, particularly in a general education course titled “Fiction and Life: Understanding Human Development.” This course marked the first exposure for students to book-length fiction in English and critical response written in English, revealing the efficacy of using fictional works as content-based ESL instruction at the tertiary level in Hong Kong.

Methods: Employing a mixed-methods approach, the study included questionnaires distributed to 310 students and thematic analysis of semi-structured interview data.

Results: Findings indicate a largely positive attitude toward the reading and writing experience, suggesting benefits for ESL teaching and learning in Asia.

Discussion: The study advocates for incorporating English literature into the general education curriculum to foster a more organic and contextualized language acquisition process. This research uniquely contributes to the field by examining student perceptions in a self-financed tertiary institution context, offering new insights that have not been explored before in Hong Kong’s ESL landscape.

1 Introduction

Teaching of English literature as a means to improving English as a Second Language (ESL) learning is a pedagogy diminishing at the tertiary level across universities in Hong Kong. Although reading English literature has been associated with a variety of benefits to learning beyond improving English proficiency, such as improving student motivation, engagement, and critical-thinking skills (Vural, 2013; Rahman and Manaf, 2017), it is implemented less and less in ESL due to the increasing incorporation of machine-based, AI-assisted pedagogies, as well as the more instrumental attitude toward language learning (Shi et al., 2024). This study investigates how tertiary students perceive themselves as English learners, especially as readers and writers in English under the influence of a general education English subject focusing on reading contemporary book-length novels. It is a case study (Flyvbjerg, 2011) using a mixed-methods approach, comprised of questionnaire surveys and semi-structured interviews on English literature course titled “Fiction and Life: Understanding Human Development” for ESL students at a tertiary institution in Hong Kong. This introductory chapter sets out the rationale behind this research, detailing its aims, objectives and research questions, as well as prefacing the structure of this paper.

1.1 Rationale

This study is motivated by the importance of English to learning in Hong Kong as English is the medium of instruction across all universities. Though English literature used to be a fundamental part of the English curriculum in ESL, the rise of the communicative approach to English has seen it take a backseat compared to other methods of teaching. As a meta-analysis of teaching methods in Hong Kong (Lo and Lo, 2014) has reported, the perceived efficacy of teaching in L2 (the secondary language) has led to more use of English texts within the classroom in recent years. As students are growing increasingly reluctant to read in the digital age, incorporating imaginative literature holds notable pedagogical value within ESL instruction. Gaskins (2015) advocates adding to the typical ESL curriculum choices of short story, novel, poem and play to also include literary essays. Ghosn (2002) holds the belief that when engaging with literary works, L2 learners have the potential to expand their knowledge of the target language’s nuances, such as patterns and precise vocabulary and passionate narratives, as well as deepening cultural understanding and critical thinking, which are difficult to achieve through other text types. More recent studies emphasize integrating literature into L2 instruction as a highly effective language acquisition strategy (Tsang et al., 2020; Mart, 2021). This body of work further posits literature as having potential to meaningfully contribute to L2 students’ development of advanced linguistic competencies.

Furthermore, studies of the use of English literature as a form of content-based instruction are somewhat scant. A narrative review of existing studies carried out in Chinese secondary schools indicated the potential for English literature to improve the quality of ELT in China (Zhang, 2023), but the study was limited to secondary school students. Studies carried out about teacher beliefs about incorporating literary texts into ESL teaching note mixed results (Cheung and Hennebry-Leung, 2020), whilst research into student perceptions and experiences of the use of literature in their tertiary education has not previously been published. Therefore, there is a research gap that can be filled by the current case study. By focusing on a self-financed tertiary institution in Hong Kong, this study provides a fresh perspective on student attitudes toward literature in ESL, an area that has been underexplored.

Finally, there are critical questions regarding the approaches to teaching and learning English literature itself. There is a lack of consensus as to the effective ways of incorporating English literature into courses designed primarily to facilitate improved English proficiency (Nosratinia and Fateh, 2017). For this reason, research into students’ perceptions of learning English literature can not only testify previous research findings such as improved motivation, engagement, and critical-thinking skills (Vural, 2013; Rahman and Manaf, 2017) in the context of Hong Kong and Asia, but also provide pedagogic implications that may help improve course design and curriculum development to facilitate better English language acquisition that reaches beyond the grammatical and technical aspects. This study, therefore, offers a novel contribution by examining these pedagogical implications in a contemporary setting, providing updated insights that can inform future curriculum designs.

1.2 Aims, objectives, and research questions

The aim of this research is to inform ESL course design with regards to appropriate English literature modules. Through investigating student first-ever experiences of taking a course on fiction, it is hoped that curriculum developers may help students improve their English proficiency that is not limited to the usual quartet of listening, speaking, reading and writing but cultural understanding and critical thinking. Moreover, the study hopes to establish broader benefits of English literature education which is applicable to Hong Kong and potentially to other East Asian contexts. This study stands out by focusing on contemporary fiction, which has rarely been the focus in Hong Kong’s tertiary education, thus providing new insights into modern pedagogical strategies.

The above aims can be achieved through meeting the following objectives. First, we establish how individuals who study English literature as their general ESL course perceive it as contributing to their English proficiency. Second, we investigate how these students perceive the course as contributing toward their learning experience generally. Third, we probe into how English literature can be better harnessed within ESL contexts, including features such as assessment, pedagogy, and course design.

Based on our aim and objectives, specific research questions have been developed as follows:

• What are the views of undergraduate students in Hong Kong toward reading fiction in English?

• What do students perceive as the benefits and problems of studying fiction in English as part of their general education?

• How can curriculum developers better design English modules that use literary texts for the purposes of better English Language Teaching (ELT)?

These questions guide the design of this research.

1.3 Structure

The remainder of this paper is structured in the following manner: First, a review of the literature will examine what has been discussed regarding the use of literature in ESL contexts. Second, it will contextualize the study and reveal a gap in the literature that this study aims at filling. Thirdly, we will explain the methodology of this research, justifying the study in terms of both its theoretical position as well as practical implications the findings section reports and analyses both the quantitative survey data and the qualitative interview data, discussing these results with regards to this study’s research questions. Finally, the conclusion summarises the study and includes recommendations for curriculum design and further research.

2 Literature review

2.1 Literature and learning

A majority of research into the ways in which teaching English Literature in ESL contexts might improve learning generally is focused on its relationship with critical thinking skills. For example, one study focused on the use of English literature in teaching creativity and critical thinking skills, highlighting positive outcomes across three areas: rational thinking, purposeful thinking, and effective relation with contexts (Rahman and Manaf, 2017). Other studies focus on trying to explain how such correlations function. For example, one study posited that studying English literature functions to this end according to reader response theory (Qamar, 2016), a literary theory that views the reader as an active agent in creating meaning through engaging with literary texts (Tyson, 2006). Other studies focus on how to use English literature toward inculcating critical thinking skills in the ESL classroom, such as through taking a problem-based approach to teaching literature (Rahman et al., 2016).

There is therefore a focus across research into the topic in understanding what aspects to learning and processing skills that exposure to literature might improve. Some of these studies are located in ESL or EFL contexts, such as one that explored the use of Bloom’s taxonomy in teaching creative and critical skills through English literature in Malaysia (Rahman and Manaf, 2017). Other studies focus more broadly on the incorporation of English literature into courses and employability, suggesting that English literature is perceived to offer both intellectual challenges and practical advantages (Longstaffe, 2015). These studies broadly cohere on the perceived educational value of English literature – based on its promotion of important and transferrable learning skills – though the evidential basis supporting these connections is comparably weak.

Other studies have focused on the relationship between literature and student motivation and engagement in ESL classes. For example, one study used questionnaires to gauge the attitudes of 60 university students toward the English literature component of their ESL class, finding that the motivation to engage with the literature was linked to motivation to acquire the language skills required to comprehend the text (Awang and Kasuma, 2012). Other studies have related this increase in motivation to learning outcomes also. For instance, a study using both an experimental and control group found that self-reported motivation was higher among a group that used literature in English language teaching (ELT) than those that did not (Vural, 2013).

Despite a lack of clear empirical evidence supporting the connections between English literature and the development or enhancement of relevant learning skills, the apparent basis for improvement to student motivation may provide in itself reason to study the effects of English literature education upon language students. Through undertaking studies of student perspectives, it may be possible to infer if the assumed effects on motivation are present in a specific cultural context, such as in Hong Kong. Such a rationale is at the foundation of the primary research undertaken below.

2.2 English literature and English skills

Much of the literature measuring the efficacy of teaching English literature toward improving English language skills is outdated, with a paucity of studies carried out in the twenty-first century. A commentary on using literature for teaching English published in 2001 notes that using literature in the classroom was falling out of vogue due to its perceived uselessness toward incorporating a communicative approach to teaching English (McKay, 2001). However, older experimental studies did note apparent success in incorporating literature into ELT (Spack, 1985; Sage, 1987; Oster, 1989; Gajdusek, 1998). This suggests that more up-to-date studies are required.

More recent studies have noted some advantages to using literature-based ESL. One study advocated using content-based literature instruction in the secondary-school ESL classroom to promote literacy development, supposedly providing language models and integrated language skills for learners (Custudio and Sutton, 1998). However, the study relied on significantly older literature and was largely focused on the how of incorporating literature, much of which itself lacked a clear basis in empirical research. Generally speaking, recent research on the role of literature in the English language classroom is sparse with regards to measured outcomes.

Some studies, however, have focused on student attitudes toward literature within ESL classrooms. For instance, a study carried out in Malaysia found that students were overall positive about the use of literature within the ESL classroom, though that they were more negative about the methods used by teachers centring around comprehension tasks (Ghazali et al., 2009). One thesis on the topic examined both teachers’ and students’ attitudes toward the uses of literature in the ESL classroom, finding that students and teachers were both negative toward the use of literature, preferring communicative activities (Baba, 2008). Conversely, a survey of 53 ESL students found that textual type made a significant degree of difference in terms of student attitudes toward literature within ELT, explicating this in terms of student interest, motivation and engagement with specific texts or types of text (Tevdovska, 2016). This is informative given that it suggests that cultural and even personal factors (e.g., genre preference) might impact the efficacy of literature incorporation into ELT in terms of contributing toward motivation and engagement.

With regards to how English literature ought to be taught to these ends, the efficacy of content-based instruction (CBI) has been evaluated by some studies. Some studies have found positive outcomes to using this approach. For example, a literature review of the use of CBI In ESL contexts found that CBI was generally associated with positive learning outcomes when compared with other methods of instruction (Karim and Rahman, 2016). Other studies note no noticeable benefit from using CBI as compared with other methods of teaching literature. For example, one study carried out with 90 ESL learners at the tertiary level compared CBI with collaborative strategic reading (CSR) and found that there was no significant difference in outcomes between the two groups (Nosratinia and Fateh, 2017). This potentially undermines the empirical basis for the utility of incorporating literature into ELT. However, given that the focus in these studies was on content-based instruction rather than English literature specifically, it may be that the types of content and tasks associated with literature improve outcomes through alternative mechanisms. The potential utility of literature in ELT thus remains an open question.

2.3 Research within Hong Kong

Some studies have lamented the decline of English literature in the English curriculum of Hong Kong since the 1980s. For example, Evans (1996) noted that the shift toward communicative language teaching had seen the status of English literature reduced in the curriculum of Hong Kong due to the perceived importance of using English to communicate within the classroom. Consequently, studies have noted that the role of English literature toward English language education has not been widely researched within Hong Kong (Poon, 2009). There is thus apparently a tendency to reintroduce literature to ELT in Hong Kong.

As stated above, much of the research carried out within this context is now outdated. For instance, one study carried out some 25 years ago criticized a focus on using abridged classical novels in English literature for ESL in Hong Kong, recommending instead that more contemporary literature be used to engage students (Kooy and Chiu, 1998). The high-school English curriculum it refers to has advanced significantly since this time, rendering many of its comments about curriculum design and practice irrelevant within the present context. With reference to student attitudes, the most recent investigation into tertiary students’ attitudes toward English literature was carried out in Hirvela and Boyle (1988), indicating a need for more recent research.

There has, however, been some recent research within the context of Hong Kong as to the relationships between teaching English literature and acquiring English as a second language. One study, for example, examined ESL teachers’ beliefs and practices of teaching literary texts (Cheung and Hennebry-Leung, 2020). Using lesson observations and unstructured interviews, the study found that there was inconsistency in the ways in which teacher beliefs about the role of English literature in English acquisition correlated with their beliefs, highlighting the role of emotion as impacting teacher cognition. However, as the study largely measured teacher beliefs and was focused on the relationship between cognition and practice, its relevance to students’ views and experiences is limited.

2.4 Research gap

As the above literature review has demonstrated, there is a gap in the literature with regards to understanding student attitudes toward the use of literature in English language teaching at the tertiary level in Hong Kong. In general, a shift toward CLT has been accompanied by less perceived utility for literature within ELT, meaning that it has served less as a focus of research. The studies that do exist report mixed results for student attitudes toward English literature for English language learning and likewise mixed reports on the efficacy of its delivery through content-based instruction. A dearth of research within the context of Hong Kong generally invites further research into understanding how students perceive the incorporation of literature into ESL courses in Hong Kong universities. This study uniquely contributes by examining student attitudes in a contemporary context, with a specific focus on modern fiction, providing new and relevant insights into the integration of literature in ESL education.

2.5 Theoretical framework

This study is carried out from within a social constructionist theoretical framework. Social constructionism holds that meaning – such as that comprised within student beliefs and attitudes – is influenced by institutional norms; by the same token, institutional norms are themselves products of social practices rooted in actor beliefs (Witkin, 2012). Individuals thereby make meaning out of reality through their interactions with social reality (Shotter and Gergen, 1994). In this way, what individuals believe about English literature’s educational value will be strongly influenced by their interactions with English literary education itself, such as through ESL courses.

In terms of guiding research design, social constructionism admits a subjectivist ontology on account of its rooting of human behavior in their internal beliefs (O’Reilly, 2009). Consequently, accounting for empirical trends – such as self-reported beliefs – can be developed through trying to understand how experiences, perceptions and beliefs motivate these behaviors. As such, social constructionism is often associated with qualitative research (Alvesson, 2009). However, there is no theoretical commitment to undertaking qualitative research borne out of the ontological or epistemological commitments of a social constructionist framework (Holstein and Gubrium, 2008). As such, this study was designed on the basis of a flexible theoretical framework with respect to research methods.

3 Methodology

3.1 Research design

The decision to utilize mixed-methods research was influenced by practical, as well as theoretical, considerations. There are a number of advantages to using a mixed-methods approach in this study. For one, they can be useful in terms of triangulating results (Ivankova et al., 2006). Pursuing either qualitative or quantitative methods in isolation may lack comparable rigor (Mertens and Hesse-Biber, 2012). Additionally, factors such as researcher bias in qualitative research may be offset through including quantitative analysis in a study design (Noble and Smith, 2015). In the context of this case study, although we were able to gather a considerable number of valid survey replies, we still decided to conduct more in-depths interviews with individual students as their first-hand experience of their first encounter with English literature per se was deemed valuable. This case study is novel due to its focus on a self-financed institution and the first-time offering of a contemporary fiction course to a diverse student body, providing a unique intersection of L2 acquisition and content-based instruction.

There are a number of further benefits to using both qualitative and quantitative approaches. Firstly, quantitative methods are useful for identifying broad trends across a large set of data (Yilmaz, 2013), making them well-suited to understanding how students generally feel about English literature education. However, reducing data for quantitative analysis can also lose some of the nuance and detail contained in participant perspectives (Carter and Little, 2007). For this reason, qualitative data and analysis may be conducive toward better understanding why individuals have responded to take an English literature module in the ways that they report. Therefore, this study utilises a mixed-methods approach to analysis, allowing for the trends observed through quantitative analysis to be expanded upon through qualitative analysis of interview data.

The case study is unique and worth investigation due to the following reason: it was the first time a course on contemporary fiction in English was offered to all undergraduate students at the tertiary institution, with a wide range of disciplines such as tourism, engineering, professional communication and finances. The majority of the students had learned English as a communication instrument that is irrelevant to their academic training. Hence, this literature course might have brought new insight into their language learning experience. Morever, this course posits itself at a unique intersection of L2 acquisition and content-based instruction that is not commonly applied in self-financed institutions in Hong Kong. To investigate its efficacies might be useful for future language education in Hong Kong that is more cultural sensitive and human-centred.

3.2 Participants

In designing the research study, it was important to ensure that a sufficient number of participants were studied and that their responses would prove representative of the target group (ESL students in Hong Kong). Students were considered admissible to the study if they had completed recently a module that had incorporated English literature into English language teaching to a sufficient degree. In order to ensure that sufficient experience of this had been gained, it was decided to limit students to those undertaking a new course on fiction in Semester Two, 2022–23. This required using purposive sampling in order to reach out to the limited number of students who had recently completed – or were about to complete – such a module.

All students undertaking the subject intended to fulfil English reading and writing requirements stipulated by the university. The module delivered English language teaching with regards not to subject-specific knowledge but related to the Humanities and Social Sciences, studying human development through the lens of contemporary fiction. Students were exposed to a wide range of perspectives and theories across psychology, philosophy and the social sciences related to human nature, human relationships and personal development. The module’s aims in terms of knowledge include literacy, higher-order thinking, and lifelong learning, with intended learning outcomes related to the development of analytical abilities, oral presentation, critical analysis, knowledge of human development, and English reading and writing skills.

The module was designed according to the principles of content-based instruction, and students were encouraged to read set literary texts before participating in close readings of excerpts in class as well as reflection on the content itself. Beyond this, the ELT methodology involved active learning, such as class discussions, computer-mediated activities, and interactive learning. In terms of assessment, the programme used various methods, including continuous assessment, group projects, and individual essays and reflections.

Email addresses for prospective students were collected and then they were presented with a scoping questionnaire to complete to ensure that they were eligible for the study. Once this had been completed, informed consent was obtained before the students were able to complete the online questionnaire. All eligible students were initially approached to participate in the survey, with 114 students successfully completing the survey to a sufficient standard. These participants were 64 per cent male and 36 per cent female, whilst 85 per cent of students were first-years at the university. Among these students, 15 agreed to be contacted ahead of a further interview, with 12 interviews with students eventually being conducted. Students were all Hong Kong locals, aged 19 to 23, and were split evenly in terms of gender.

3.3 Research instruments

As mentioned in the introduction, this study uses both questionnaire and interview as its primary data. Surveys are a suitable method for gathering vast amounts of data usable in quantitative analysis (Bielick, 2016). However, whilst useful for gathering data that may be reduced down for statistical analysis, they are comparatively poor at producing information that is sufficient for qualitative analysis (Jansen, 2010), due in part to the lack of nuance involved in short-form responses and numerical data (Bolderston, 2012). Consequently, questionnaires were selected for gathering data for quantitative analysis only. The questionnaire was designed to use closed or scalar responses such as Likert-type scales that could provide easily reducible data for subsequent statistical analysis (see Appendix A).

Interviews were selected as a method of data collection as detailed interviews can yield meaningful findings regarding a participant’s experiences and beliefs (Gill et al., 2008). Unlike the survey questions, which used closed, scalar responses, the questions designed for the interview were largely open-ended to encourage more natural responses (Rapley, 2001) (see Appendix B). This was selected due to the comparatively high level of detail that are given in open-ended questions as compared with closed questions (Allen, 2017). Additionally, more open questions allow for the participant to have freedom in terms of the content of their answers, which is not the case with more closed questions. This can potentially remove the potential for questions biasing the response of participants (Clark et al., 2019).

Likewise, a semi-structured interviewing technique was employed in order to ensure that responses were sufficiently detailed without leading participants in the content of their answers (Zhang and Wildemuth, 2017). An overly structured approach to questioning prevents interviewers from prompting respondents for more detail or to elaborate on points of relevance (Magaldi and Berler, 2020), whilst an entirely unstructured approach does not ensure that questions and answers are relevant to the study’s research questions (Burgess, 1982). For these reasons, a semi-structured approach to interviewing was decided upon.

3.4 Data analysis

The survey data was collated using online surveys, from which digitized responses in an Excel file could be automatically generated. This was then subject to analysis using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), from which various quantitative analyses could be undertaken (Salcedo and McCormick, 2020). Descriptive analysis was carried out to report the findings of the survey, as well as using the student’s t-test to look for correlations between trends in the data. The findings of this are reported in the chapter below.

Qualitative analysis of the interview data was carried out, utilising a thematic approach to interview data analysis. Thematic analysis is a straightforward way of analysing interview data that uses the inductive generation of codes to track prevalent themes across a set of data (Attride-Stirling, 2001):

Thematic analysis is a method for analysing qualitative data that entails searching across a data set to identify, analyse, and report repeated patterns. It is a method for describing data, but it also involves interpretation in the processes of selecting codes and constructing themes. A distinguishing feature of thematic analysis is its flexibility to be used within a wide range of theoretical and epistemological frameworks, and to be applied to a wide range of study questions, designs, and sample sizes (Kiger and Varpio, 2020, p. 2).

Thematic analysis thus allows particularly prevalent or emphatic themes to be assigned to selections of primary data, from which a broader set of themes and findings may be derived (Charmaz, 2003).

Following this, manual coding of the interview data saw chunks of data being assigned thematic codes by the researchers, which were then compiled into more representative themes across the interviews as a group (Braun and Clarke, 2006). This was undertaken through utilising an inductive approach to coding so as not to prejudge the content of the responses given (Boyatzis, 1998). These themes were then sorted into themes and subthemes that structure the appropriate section of the findings chapter below.

3.5 Ethical considerations

A number of ethical considerations were taken into account when planning this study. First, permissions from the institution were sought and approved. Second, informed consent was sought prior to carrying out any research with participants, in line with the ethical necessity of making participants aware of how their data may be used (Oliver, 2010). Third, provisions were made for the anonymisation of any information identifying participants, such as personal names, the name of the module, and that of the institution (Saunders et al., 2015). Beyond this, the researchers took care to ensure that their own identity and beliefs did not skew their interpretation and analysis of results, assuming as neutral stance a stance as possible with regards to the outcome of research.

3.6 Processes

From February to May 2023, questionnaires were dispatched to 310 students who had completed an English Literature course for ESL module at a university in Hong Kong. Students were asked a number of questions about their perceptions of the module and its contributions toward a variety of factors related to their own learning or learning in general (see Supplementary Material). Of all students approached, 114 students responded with sufficiently complete questionnaires. However, the sample size was not large enough to use random sampling given the limited number of students completing this module.

The questionnaire included a question about their amenability to participating in an interview for the study. Interviews took place with 12 students who had participated in the survey, conducted on a face-to-face basis and using audio-recording software to record the interviews. These recordings were stored in password protected files and were transcribed using digital software and then manually corrected by the researcher. After this point, the original recordings were deleted in accordance with data protection (see below). The transcriptions were then prepared for analysis.

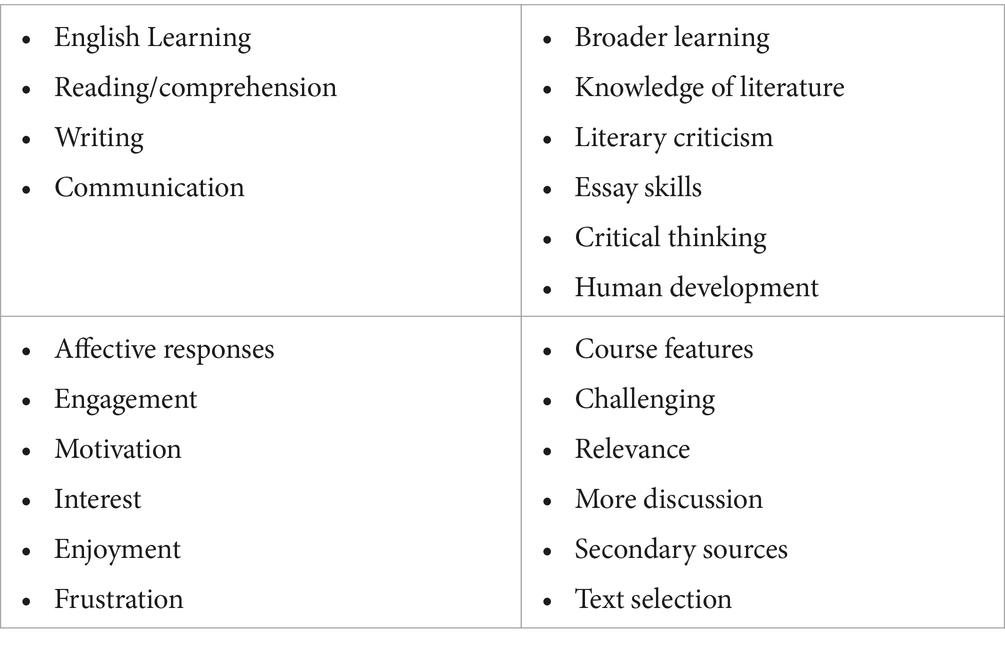

Analysis of the transcripts was carried out according to the following protocol. Manual annotation of the transcripts was used to add notes regarding potentially relevant themes before refining these notes into themes representative for that participant. These were then compiled into a broader table of themes (see Table 1), cutting those themes that were outliers or relatively low emphasis in favor of those more prevalent or emphatic. These themes were then used to structure the finding of the section on the study’s qualitative findings (5.2).

Table 1. Results of thematic analysis of interviews with 12 students undertaking a literature for ESL module at a Hong Kong university.

4 Findings

4.1 Findings from the questionnaires

The questionnaires presented to the participants included a number of closed questions with ‘yes’ or ‘no’ responses to general questions about the course. These responses were broadly positive regarding the perceived enjoyability and educational benefits of the course. For example, 92.1 per cent of respondents stated that they found the course both ‘interesting and engaging’, indicating that student engagement was high. A further 87.7 per cent indicated that they felt the course was a valuable use of their time also, indicating generally positive evaluations in terms of their investment into it. This is reflected in the perceived educational benefits of the course.

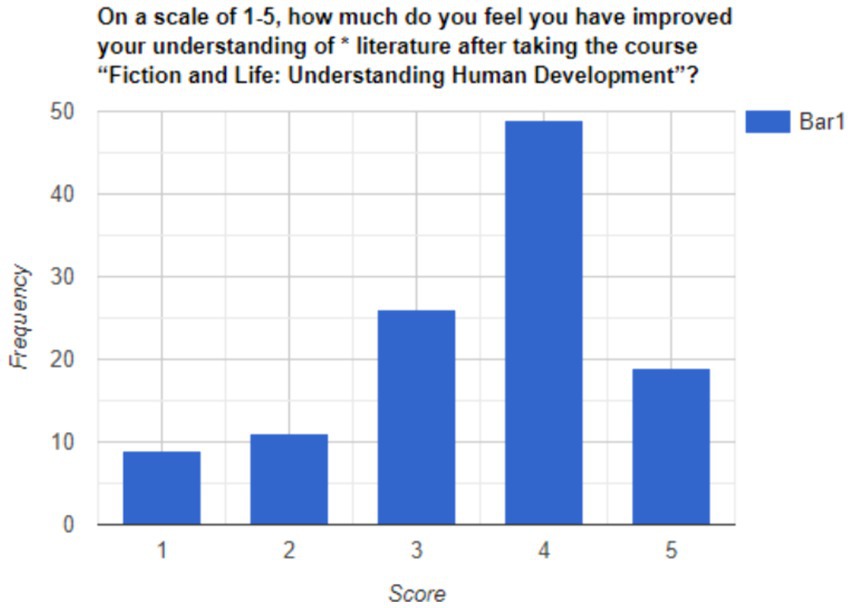

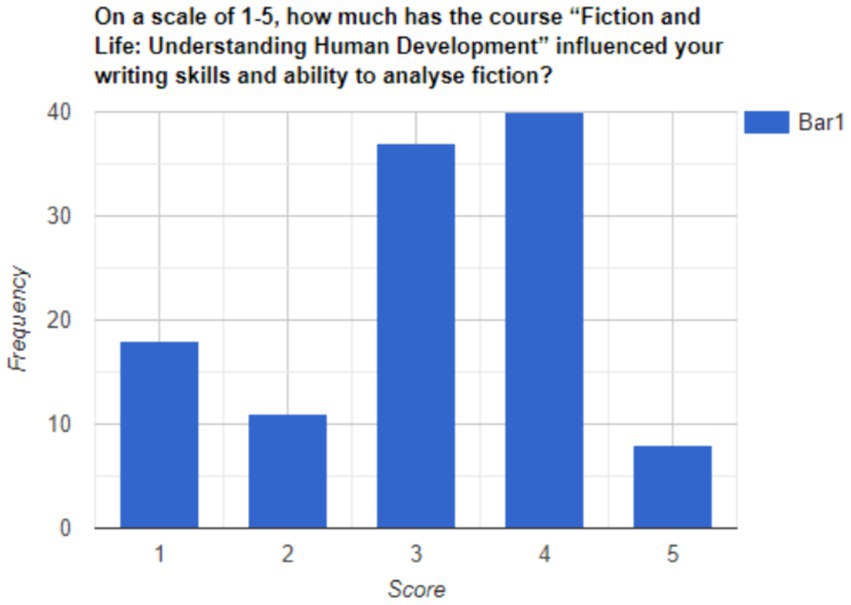

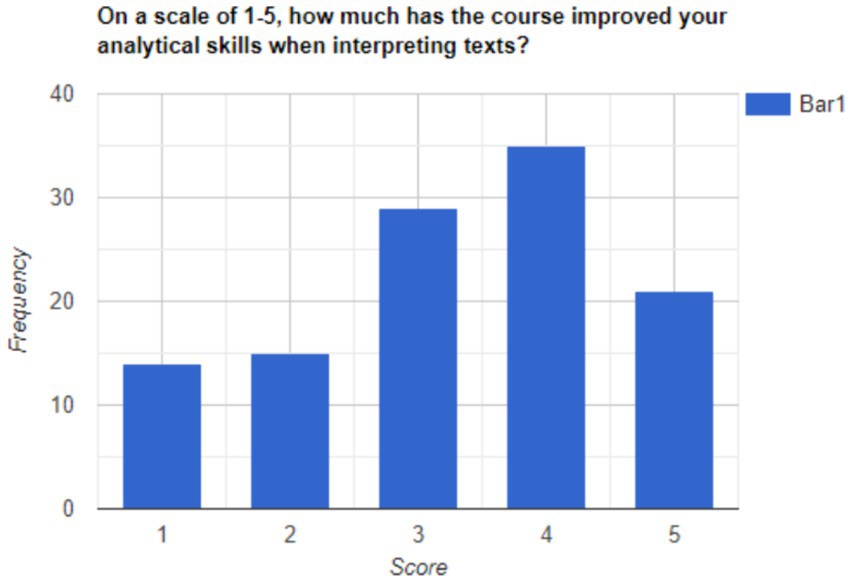

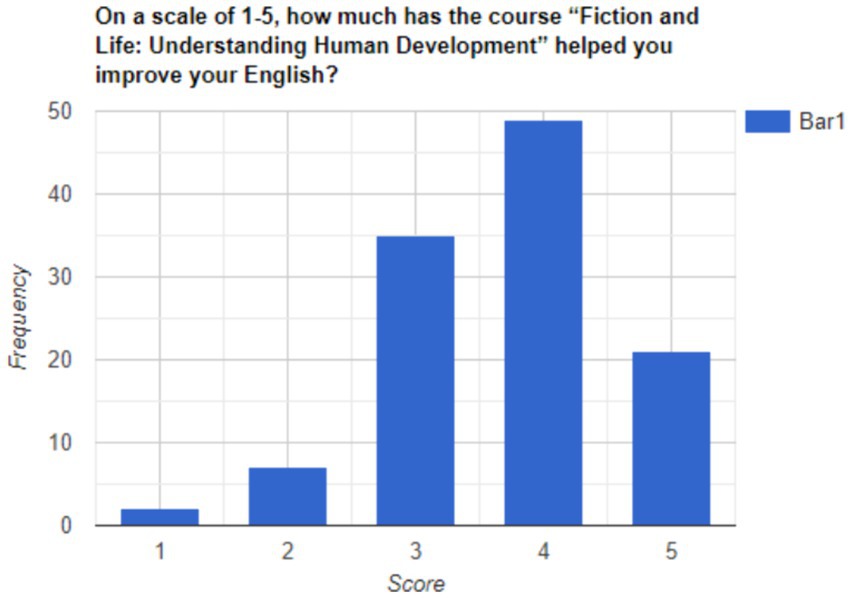

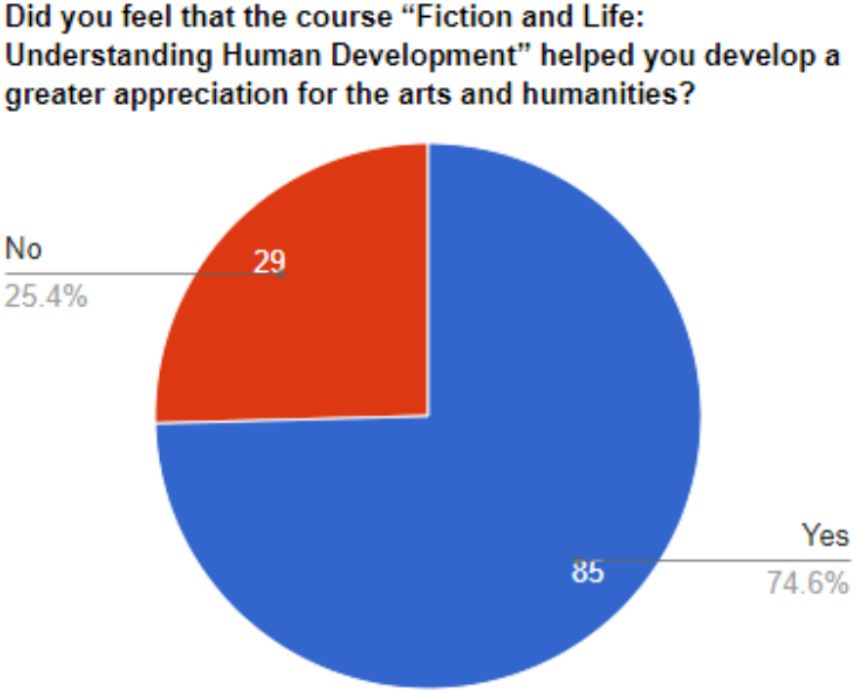

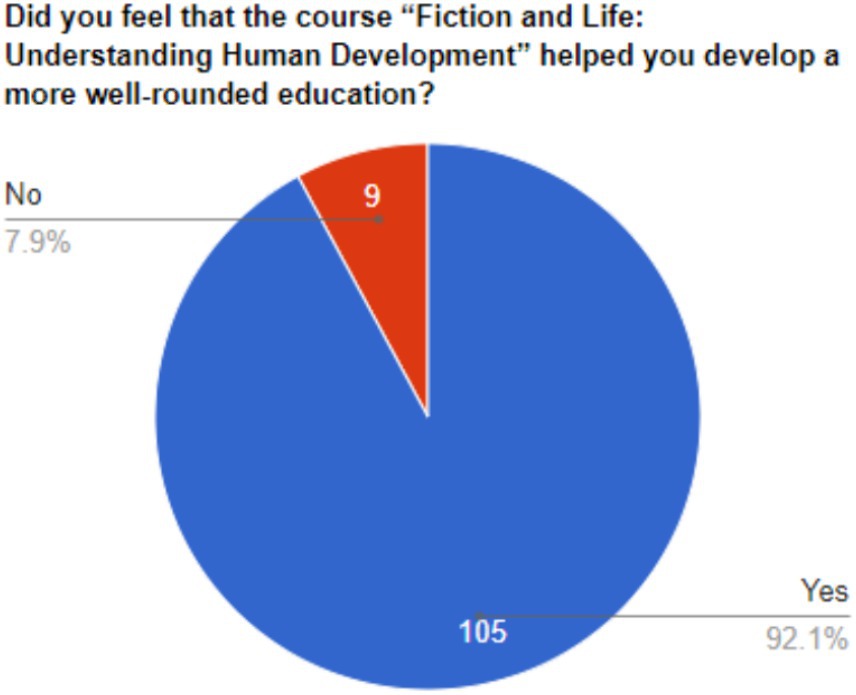

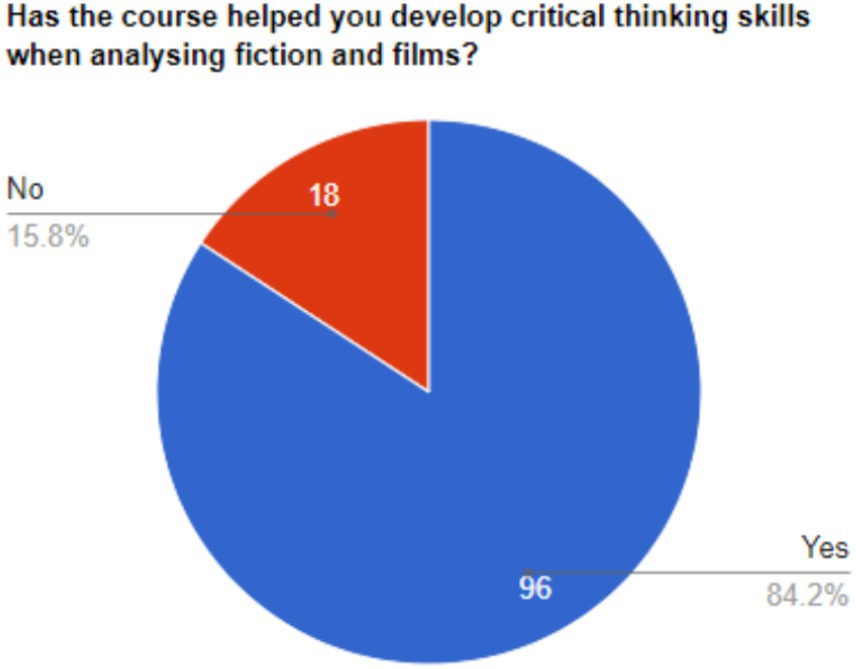

Figures 1–4 indicate that students broadly had positive perceptions of the educational value of the programme. A majority of the students responded positively to all questions regarding the educational value of the programme. Some 82.5 per cent of students felt that the programme had improved their understanding of fiction, whilst a similar proportion felt that it had helped develop their critical thinking skills for use in analysing fiction and film. Interestingly, whilst only 74.6 per cent of students stated that they felt that the module had improved their appreciation for arts and humanities, 92.1 per cent stated that they felt it had given them a more rounded education. Results were also positive in terms of questions relating to English skills, with 75.4 per cent of students stating that they felt their abilities to converse in English had improved, whilst 95.6 per cent felt that their ability to write in English had improved. This distinction perhaps reflects the weighting of written assessments as compared to group work and class contributions within the study’s assessment.

Figure 2. Proportion of students who felt programme had helped them develop appreciation for arts and humanities.

Figure 3. Proportion of students who felt programme had helped them develop a more rounded education.

Figure 4. Proportion of students who felt programme had developed their critical thinking skills for analysing fiction and films.

A number of scalar responses were also recorded across the survey data. Figures 5–8 report some of the findings to questions regarding students’ perception of the educational benefits of the programme. On a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 representing no improvement and 5 representing great improvements, students gave an average score of 3.5 for how they perceived improvements to their own comprehension of literature. By way of comparison, students reported a mean score of 3.1 when asked about improvements to their ability to critically analyze film and television, with double the number reporting no improvement at all. This was broadly in line with the results to the closed questions asked on the same topics. Comparatively, students gave a mean score of 3.3 when asked about improvements to their analytical ability to analyze texts. Scores for perceived improvements to English skills were highest, with a mean score of 3.7 reported across the participants.

Using t-tests to compare the scores given for various questions, correlations between various trends could be looked for. For example, students were asked to rank their prior knowledge of English literature prior to taking the course. When conducting two-tailed t-tests against scores for literature comprehension, critical analysis skills, and English skills, no statistically significant correlation in either direction was noted; however, a positive correlation was noted with perceived improvements to analytical skills for interpreting texts (R2 = 0.671). This indicates that prior knowledge of literature was only correlated with skills specifically related to the analysis or interpretation of literature rather than to English skills or textual comprehension.

Students were also asked about their motivation to learn more about literature as a result of the course. Here, the lone correlation that was statistically significant was between improved motivation to learn and improved English skills (r = 0.705, p = 0.043). This suggests that students who felt more motivated by the course may have seen the greater benefits in improvements to their English. Unfortunately, the study did not take pre-intervention scores, so the extent of these improvements is difficult to judge. In addition to this, there was a correlation also between rating literature as aligning with one’s interests and improvements to English skills (r = 0.657, p = 0.039). This suggests again that engagement may be strongly linked to the benefits to English learning brought about through incorporating literary content into ELT.

4.2 Interviews

Interviews with 12 participants in the study were undertaken following the questionnaires and were subjected to thematic analysis. Participants were asked a range of questions regarding their experience of the programme, the answers to which were coded into four themes comprised each of several subthemes (Table 1). These themes structure the subsections of this analysis.

4.2.1 English learning

The 12 participants in the interviews described benefits to their learning from their participation in the programme. Improvements in reading and comprehension were described by many of those interviewed. Some attributed this to the sheer volume of reading required, with Participant B stating, ‘I had never read an English text half as long as The Kite Runner and this really forced me to search the meanings to a lot of words and to understand things like conjugation that I wasn’t familiar with’. Others highlighted that it was being asked to engage with literature specifically that was useful. Participant F, for example, pointed out the use of nonstandard English in To Kill a Mockingbird and how this had improved their comprehension of colloquial American English. Participant L stated that engaging in close reading with difficult texts helped them to ‘read between the lines’ when reading English, adding that texts such as Atonement prompted deeper understanding through challenging the reader to look for subtext and hidden meanings.

The participants unanimously stated that the course had helped improve their written English. Here, both more exposure to written English as well as being tasked with extended writing assessments were cited as instrumental to their improvements. Participant H described how their experience of assessments had improved their written English:

I have obviously written in English much before, but I think the hardest thing is to write an essay that is academic and for it to not sound childish. So, I was having to also read essays, like, how do they word that, and should I word it? [laughs] So it’s not really ‘oh, you are reading a lot of words’, but also, I have now to really think about how I express myself in writing. (Participant H).

Even participants who described their written English as of a very high standard prior to the course felt that the high standards for academic rigor improved their ability to write in English.

In terms of communication, the responses were more mixed from the participants. Some participants felt that communication was not really the focus of the module, interpreting it as more focused on reading and writing. Others such as Participant D stated that they felt their English had improved as a result of ‘searching for English words’ when participating in class discussions about texts. However, Participant G noted that classmates tended to speak in L2 when conducting group work, suggesting that this assessment was not designed sufficiently to improve communication in English.

4.2.2 Broader learning

The participants in the study described their knowledge of the content as having increased significantly as a result of the module. Participant A stated that, ‘I do not know if this is the point, but I feel I can better understand literature now’ and others felt also that their skills related to comprehending literature had improved. Some students felt that they were more confident in analysing and critiquing literature than before, whilst some students noted that they gained new interests in topics related to Politics and Social Sciences. As above, students also mentioned their increased ability to compose high-level essays in English, and some cited their essay writing skills as generally improved as a result.

When questioned specifically about critical thinking skills, the students gave mixed responses as to how far they felt their skills had been developed through the module. Participant I offered an opinion shared by many of the other participants:

I do not know how far my critical thinking has improved in general, but my critical thinking in English has definitely improved. I’m able to better sort of… deconstruct sentences, to understand what meanings may be contained other than what is immediately there. (Participant I).

Other participants noted that their engagement with English literary texts were now deeper than before, with Participant B noting that Chinese and English symbolism in literature often followed different patterns: ‘I’ve started reading poetry by Zhai Yongming and I can see that there are big differences between what symbols like ‘night’ and the colour ‘black’ mean between Western and Chinese poetry’. However, most participants did not characterize their critical thinking as improving beyond subject-specific knowledge or relating specifically to the English language.

4.2.3 Affective responses

The participants discussed their affective responses to the programme. As was revealed by the quantitative analysis, the students generally spoke of their interest in the module’s content, describing their engagement with it as related to this interest. Some even linked this to a greater motivation to learn English:

I know now if I want to enjoy more literature, I have to improve my English because it’s not as good in Cantonese or Mandarin. You lose some meaning so it’s better to read original. (Participant K).

One thing is that I’m reading more English books now and I can feel my understanding of English literature is growing. […]I can now understand more complex language than before. (Participant E).

This indicates perhaps a causal mechanism by which a heightened interest in English literature motivates students to improve their English comprehension.

In general, most of the students did indicate that they enjoyed the module, with some even noting their surprise at how much they enjoyed it. However, a couple of participants did note frustration with it. One stated that the ‘level of English was too difficult’ for them to make much headway with the literature assigned, whilst another stated that they did not see the point to the programme:

I really think I only want to learn English for my area, so that I can do my job. I do not know how learning about something like racism or sex is meant to help me. I think these are interesting books to some but not to me. (Participant J).

Whilst these were minority views, it is notable that such students noted that a lack of engagement with the material reduced their enjoyment of the module overall, as well as their perception of what they learnt from it.

4.2.4 Course features

The participants discussed the course features with regards to what they felt was conducive to their English learning. Most participants stated that the module was challenging, and a majority of those felt that this prompted them to improve their skills in order to keep up with its demands. Some students, however, stated that they felt that they would have benefited from having access to more L1 (first-language) secondary sources with regards to interpreting the texts. One participant stated, for example, that secondary texts on literary criticism in English were ‘too dense’ for them to engage with meaningfully.

A feature that seemed to heavily impact the degree of enjoyment of a programme or a unit of it was how far the students engaged with the set texts and their themes. Some wished that they had more say in selecting texts that they felt were relevant to them, stating that some of the themes did not carry much relevance to contemporary issues within Hong Kong. One, for instance, stated that they would have liked the opportunity to have more freedom in what text they analyzed for their assessment.

Finally, some students felt like they would have benefited from more discussion and group interaction. Whilst there was a fair amount of technology used in the programme, Participant G, for instance, felt that it could have been more interactive in its implementation: ‘Compared with other classes, I just feel that we spent more time reading and listening than using English’. This view was shared by a sizeable minority of the students interviewed.

5 Discussion

The above analyses of survey and interview data reveal some interesting findings, provoking further discussion. For one, the questionnaires and interviews alike indicate that students largely had positive feedback regarding the module and felt that they benefited from the programme. The majority of the students found the course both interesting and engaging. This corroborates research carried out outside of this context that suggests that students broadly welcome the incorporation of literature into ELT (Kumar, 2023).

RQ1: What are the views of undergraduate students in Hong Kong toward reading fiction in English?

Students expressed generally positive views toward reading fiction in English. As highlighted in the survey data, 92.1% of respondents found the course interesting and engaging, and 87.7% felt it was a valuable use of their time. These findings indicate a positive reception to the integration of fiction in their curriculum. The interviews further revealed that students appreciated the challenge and depth that fiction provided, with many noting improvements in their comprehension and analytical skills. This enthusiasm for the course content directly addresses RQ1 by demonstrating that students view reading fiction in English positively and recognize its educational value.

RQ2: What do students perceive as the benefits and problems of studying fiction in English as part of their general education?

The perceived benefits of studying fiction in English include improved English skills, particularly in reading comprehension and writing. For instance, 95.6% of students felt that their ability to write in English had improved, and 75.4% noted enhancements in their conversational English skills. These benefits were further elaborated in the interviews, where students discussed how the course helped them engage with complex texts and improved their critical thinking in English. However, some students also identified problems, such as the difficulty level of the texts and a desire for more interactive and discussion-based learning opportunities. These mixed perceptions address RQ2 by outlining both the strengths and challenges students face when engaging with fiction in English as part of their education.

RQ3: How can curriculum developers better design English modules that use literary texts for the purposes of better English Language Teaching (ELT)?

The findings suggest several ways to improve the design of English modules that incorporate literary texts. One recommendation is to ensure that texts are relevant and engaging for students, potentially allowing them to select texts that interest them to enhance engagement and motivation. Additionally, increasing the amount of interactive group work and discussions in English can help improve conversational skills and deepen comprehension. The students’ feedback on the need for more accessible secondary sources in L1 to aid understanding of complex literary criticism texts also highlights an area for improvement. These insights directly address RQ3 by providing actionable recommendations for curriculum developers to enhance the effectiveness of literary texts in ELT.

Students also felt that they benefited in terms of their English skills, particularly comprehension and writing more so than communication skills. Figures 1–4 above indicate that students had a positive perception of the educational value of the programme, reporting also improvements in their understanding of fiction, their critical thinking skills, and their appreciation for the arts and humanities. These findings align with those of studies into teacher perspectives on the application of literature to ELT carried out in Hong Kong (Cheung and Hennebry-Leung, 2020).

However, it seems also as though there was inadequate opportunity for discussions in class and that group work was largely carried out in L1 rather than English. This suggests that changes could be made to the course design in order to encourage more L2 discussion of texts, such as heavier weighting in favor of class contributions. Previous studies have examined ways in which L1 usage might be reduced and L2 usage increased in ESL classrooms (Davies, 2011), and such strategies may be considered for application here. For example, Chan and Walsh (2024) note that English as a medium of instruction (EMI) ought to be increased in line with interactional competence (IC) over the course of a programme.

Quantitative analysis revealed correlations between motivation and some learning outcomes, particularly related to English language skills. This was corroborated by the interviews with students, which indicated that a desire to read English literature motivated the improvement of English skills. Here, engagement with the texts appears to be important. Students interviewed who engaged less with the texts or their themes also seemed to be less forthcoming about the gains to learning they made across the module. Unfortunately, the survey did not measure level of engagement with set texts, so correlations with motivation here cannot be checked.

However, multiple other studies have explored correlations between motivation and learning outcomes in English language learning (Seven, 2020, pp. 62–71). Studies highlight the importance of fostering motivation among students to ensure good levels of motivation and thus also good learning outcomes (Mirza, 2021; Lo et al., 2024). This is included within studies carried out in China, that highlight also the importance of motivation to improving student learning outcomes in ESL (Meng, 2021). The finding that students enjoyed the literature and felt it was positive with respect to learning outcomes thus is encouraging when it comes to building connections between the approach, motivations and learning outcomes.

With regards to improvements in critical thinking skills, whilst the quantitative analysis revealed that students believed their critical thinking skills to have improved, the thematic analysis demonstrated that this was largely conceived of in terms of skills related to English comprehension and literary interpretation and analysis. Students felt themselves better able to decode complex English text and also better able to offer interpretations of symbolism and meaning in literature, but did not necessarily perceive themselves as undergoing improvements in critical thinking skills generally. Across the interviews, students were generally not forthcoming as to the wider educational benefits of the module, though felt very strongly that they had benefited in their wider education across the survey.

Extant studies in the relationship of literature to critical thinking skills appear to align with these findings. For instance, one study carried out in India found that English literature was conducive to improving rational thinking, purposive thinking, and effective relation with contexts (Rahman and Manaf, 2017). Such correlations were accounted for according to reader response theory (Qamar, 2016). It may be that the challenging aspects to literature – either in terms of literal interpretation or perhaps literary interpretation (i.e., symbolism, imagery, metaphor, etc.) – might play a role in improving critical thinking. It is thus unclear whether this relationship might be induced by the linguistic or literary features of the text and their analysis. A greater focus on methods of implementation and teaching in future studies may prove useful for separating between those two mechanisms and their effects.

The interviews are useful in contextualising why certain trends appear to have arisen in the questionnaires. The most significant finding is perhaps the relationship between engagement with texts and themes, motivation to learn English, and subsequent improved English learning outcomes. Whilst a causal mechanism cannot be established due to the non-experimental design of the study, there is a clear logic here that engaging students with literature seems to encourage English learning at a higher level of linguistic complexity.

In summary, the research questions guided the analysis of the findings, ensuring that each aspect of the students’ experiences was thoroughly examined. The positive views toward reading fiction (RQ1), the benefits and problems identified (RQ2), and the recommendations for curriculum design (RQ3) are all clearly supported by the data collected through surveys and interviews. By explicitly linking the discussion points to the research questions, the study provides a comprehensive understanding of the role of fiction in English language education at the tertiary level in Hong Kong.

Theoretically, this might work similar to how teaching English literature has been connected with literacy when learning English as a first language. Although synthetic phonics are now in vogue across many English-speaking education systems (Chew, 2018), studies have repeatedly suggested that exposure to English literature can improve literacy among even very young children (Morrow, 1992). In the same way, it may be theorized that exploration of literature through demanding a higher-level of English competency of the English-language learner might be responsible for gains in English proficiency. This is considered in the recommendations offered below.

6 Conclusion

In conclusion, the quantitative analysis of survey data revealed trends in students’ attitudes toward content-based instruction in an ESL course on fictional works. Students were generally motivated to engage with literary content, enjoyed the module, and noted improvements in their English learning and literary criticism skills. Thematic analysis of interviews indicated that students are positive about the module’s challenges, though they expressed a desire for more group work and texts more relevant to their real lives.

Based on these findings, several recommendations can be made to improve content-based literature programs for ELT:Written assessments involving challenging literature are in fact beneficial for improving English learning outcomes. However, accessible secondary sources in L1 can help students overcome the high-level academic English used in L2 literary criticism texts. Interactive work needs better design to ensure sufficient communication in the classroom. Weighting classroom contributions more heavily in assessments may encourage more L2 discussions of texts. Engaging students with texts and themes relevant to their lives may motivate them to learn English better. More importantly, allowing students to select their own English literary texts for assessments may enhance engagement and motivation.

The study’s contributions suggest how content-based instruction programs using English literature can facilitate ELT. The connections between engagement with texts and motivation to learn English are supported by correlations with greater self-perceived learning outcomes. This suggests that modules should prioritize student engagement and acknowledge individual differences in what engages students. Additionally, the relationship between perceived difficulty, learning improvements, subject-specific learning, and the acquisition of critical thinking skills relating to literary analysis are notable.

However, the study has limitations. The mechanisms proposed are speculative based on observed correlations and student remarks. Without a pre-intervention questionnaire or control group, it is impossible to definitively link student engagement with learning outcomes. Future research should employ experimental designs to test these hypotheses. Additionally, the questions in the questionnaires and interviews were insufficiently specific to pinpoint the exact nature of the educational benefits reported by students. Future research should include more specific questions to test various types of educational benefits beyond motivation and critical thinking.

Despite these limitations, this study is a first step toward understanding the utility of English literature in CBI for ELT in Hong Kong. The research indicates a potential place for incorporating more English literature in the tertiary curriculum to challenge students, improve their comprehension of complex English, and enhance academic English skills among adult learners.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the PolyU CPCE Ethics Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

NL: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. HS: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the PolyU CPCECPR Teaching and Research Excellence Fund.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1395168/full#supplementary-material

References

Allen, M. (2017). “Survey: open-ended questions” in The SAGE encyclopedia of communication research methods. ed. M. Allen (London: Sage).

Attride-Stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: an analytical tool for qualitative research. Commiss. Health Improv. 1, 385–405. doi: 10.1177/146879410100100307

Awang, Z., and Kasuma, A. (2012). A study on secondary school students’ perceptions of their motivation and attitude towards learning the English literature component. Skudai: Universiti Teknologi Malaysia.

Baba, W. (2008). An investigation into Teachers’ and Students’ attitudes towards literature and its uses in ESL classrooms. Leicester: Thesis at the University of Leicester.

Bielick, S. (2016). “Surveys and Questionnaires” in The BERA/SAGE handbook of educational research. eds. D. Wyse, N. Selwyn, E. Smith, and L. Suter (London: Sage).

Bolderston, A. (2012). Conductive a research interview. J. Med. Imag. Rad. Sci. 43, 66–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jmir.2011.12.002

Boyatzis, R. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. London: Sage.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Burgess, R. (1982). “The unstructured interview as a conversation” in Field research: A Sourcebok and field manual. ed. R. G. Burgess (London: Routledge).

Carter, S., and Little, M. (2007). Justifying knowledge, justifying method, taking action: epistemologies, methodologies, and methods in qualitative research. Qual. Health Res. 17, 1316–1328. doi: 10.1177/1049732307306927

Chan, J., and Walsh, S. (2024). English learning and use in Hong Kong’s bilingual education: implications for L2 learners’ development of interactional competence. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 34, 183–205. doi: 10.1111/ijal.12486

Charmaz, K. (2003). “Grounded theory: objectivist and constructivist methods” in Strategies for qualitative inquiry. eds. N. Denzin and Y. Lincoln (Thousand Oaks: Sage), 249–291.

Cheung, A., and Hennebry-Leung, M. (2020). Exploring an ESL teachers’ beliefs and practices of teaching literary texts: a case study in Hong Kong. Lang. Teach. Res. 27, 181–206. doi: 10.1177/1362168820933447

Chew, J. (2018). Phonics developments in England from 1998 to 2018 : Reading Reform Foundation. Available at: https://rrf.org.uk/2018/07/30/phonics-developments-in-england-from-1998-to-2018-by-jenny-chew/

Clark, T., Foster, L., and Bryman, A. (2019). How to do your social research project or dissertation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Custudio, B., and Sutton, M. (1998). Literature-based ESL for secondary school students. TESOL J. 7, 19–23.

Davies, M. (2011). Increasing students’ L2 usage: An analysis of teacher talk time and student talk time. Birmingham: University of Birmingham.

Evans, S. (1996). The context of English language education the case of Hong Kong. RELC J. 27, 30–55. doi: 10.1177/003368829602700203

Flyvbjerg, B. (2011). Case study. Sage Handbook Qual. Res. eds. N. Denzin and Y. Lincoln. 4th ed. (SAGE Publications, Inc), 301–316.

Gaskins, J. (2015). The literary essay and the ESL student: a case study. J. Aesthetic Educ. 49, 99–106. doi: 10.5406/jaesteduc.49.2.0099

Ghazali, S., Setia, R., Muthusamy, C., and Jusoff, K. (2009). ESL Students’ attitude towards texts and teaching methods used in literature classes. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2, 51–56. doi: 10.5539/elt.v2n4p51

Ghosn, I. K. (2002). Four good reasons to use literature in primary school ELT. ELT J. 56, 172–179. doi: 10.1093/elt/56.2.172

Gill, P., Stewart, K., Treasure, E., and Chadwick, B. (2008). Methods of data collection in qualitative research: interviews and focus groups. Br. Dent. J. 204, 291–295. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2008.192

Hirvela, A., and Boyle, J. (1988). Literature courses and student attitudes. ELT J. 42, 179–184. doi: 10.1093/elt/42.3.179

Holstein, J., and Gubrium, J. (2008). Handbook of constructionist research. New York: Guildford Press.

Ivankova, N., Creswell, J., and Stick, S. (2006). Using mixed-methods sequential explanatory design: From theory to practice. Field Methods 18, 3–20. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05282260

Jansen, H. (2010). The logic of qualitative survey research and its position in the field of social research methods. FQS. Soc. Res. 11.

Karim, A., and Rahman, M. (2016). Revisiting the content-based instruction in language teaching in relation with CLIL: implementation and outcome. Int. J. App. Ling. Eng. Lit. 5, 254–264. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.5n.7p.254

Kiger, M., and Varpio, L. (2020). Thematic analysis of qualitative data. Med. Teach. 42, 846–854. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030

Kooy, M., and Chiu, A. (1998). Language, literature, and learning in the ESL classroom. Engl. J. 88, 78–84. doi: 10.58680/ej1998375

Kumar, A. (2023). The use of literature in ELT classroom: an effective approach. IOSR J. Human. Soc. Sci. 28, 53–58. doi: 10.9790/0837-2812075358

Lo, N. P. K., Bremner, P. A. M., and Forbes-McKay, K. E. (2024). Influences on student motivation and independent learning skills: cross-cultural differences between Hong Kong and the United Kingdom. Front. Educ. 8:4357. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1334357

Lo, Y., and Lo, E. (2014). A Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of English-medium education in Hong Kong. Rev. Educ. Res. 84, 47–73. doi: 10.3102/0034654313499615

Longstaffe, S. (2015). “Employability and the English literature degree” in English studies: The state of the discipline, past, present, and future. eds. N. Gildea, H. Goodwyn, M. Kitching, and H. Tyson (London: Springer), 83–99.

Magaldi, D., and Berler, M. (2020). “Semi-structured interviews” in Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences. eds. V. Zeigler-Hill and T. Shackelford (London: Springer), 4825–4830.

Mart, Ç. T. (2021). Literature-based instruction: a worthwhile approach for the mastery of a second language. 3L: language. Ling. Lit. 27, 49–61. doi: 10.17576/3L-2021-2702-04

McKay, S. (2001). “Literature as content for ESL/EFL” in Teaching English as a second or foreign language. ed. N. Celce-Murcia (London: Heinle & Heinle), 319–332.

Meng, Y. (2021). Fostering EFL/ESL Students’ state motivation: the role of teacher-student rapport. Front. Psychol. 12:12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.754797

Mertens, D., and Hesse-Biber, S. (2012). Triangulation and mixed methods research: provocative positions. J. Mixed Methods Res. 6, 75–79. doi: 10.1177/1558689812437100

Mirza, S. (2021). Role of motivation in English language learning: a real challenge. Creat. Launch. 6, 224–229. doi: 10.53032/tcl.2021.6.4.33

Morrow, L. (1992). The impact of a literature-based program on literacy achievement, use of literature, and attitudes of children from minority backgrounds. Read. Res. Q. 27, 250–275. doi: 10.2307/747794

Noble, H., and Smith, J. (2015). Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research. Evid. Based Nurs. 18, 34–35. doi: 10.1136/eb-2015-102054

Nosratinia, M., and Fateh, N. (2017). The comparative effect of collaborative strategic Reading and content-based instruction on EFL Learners’ Reading comprehension. Int. J. App. Ling. Eng. Lit. 6:165. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.6n.6p.165

Oster, J. (1989). Seeing with different eyes: another view of literature in the ESL class. TESOL Q. 23, 85–103. doi: 10.2307/3587509

Poon, A. (2009). A review of research in English language education in Hong Kong in the past 25 years: reflections and the way forward. Educ. Res. J. 24, 7–40.

Qamar, F. (2016). Effectiveness of critical thinking skills for English literature study with reader response theory: review of literature. J. Arts Hum. 5:37. doi: 10.18533/journal.v5i6.961

Rahman, M., Azmi, M., Wahab, Z., Abdullah, A., and Azmi, N. (2016). The impacts of ‘Problem-based learning’ approach in enhancing critical thinking skills to teaching literature. Int. J. Appl. Ling. Eng. Lit. 5, 249–258. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.5n.6p.249

Rahman, S., and Manaf, N. (2017). A critical analysis of Bloom’s taxonomy in teaching creative and critical thinking skills in Malaysia through English literature. Engl. Lang. Teach. 10, 245–256. doi: 10.5539/elt.v10n9p245

Rapley, T. (2001). The art(fulness) of open-ended interviewing: some considerations on analysing interviews. Qual. Res. 1, 303–323. doi: 10.1177/146879410100100303

Saunders, B., Kitzinger, J., and Kitzinger, C. (2015). Anonymising interview data: challenges and compromise in practice. Qual. Res. 15, 616–632. doi: 10.1177/1468794114550439

Seven, M. (2020). Motivation in language learning and teaching. Afr. Educ. Res. J. 8, 62–71. doi: 10.30918/AERJ.8S2.20.033

Shi, H., Chan, K., Wu, C., and Cheung, L. (2024). Enhancing students’ L2 writing skills online: a case study of an introductory English literature course for ESL students. Journal of China Computer-Assisted Language Learning. doi: 10.1515/jccall-2023-0033

Shotter, J., and Gergen, K. (1994). “Social construction: knowledge, self, others, and continuing the conversation” in Communication yearbook. ed. S. Deetz (Thousand Oaks: Sage), 3–33.

Spack, R. (1985). Literature, Reading, writing, and ESL: bridging the gaps. TESOL Q. 19, 703–725. doi: 10.2307/35-86672

Tevdovska, E. (2016). Literature in ELT setting: students attitudes and preferences towards literary texts. PRO 232, 161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.10.041

Tsang, A., Paran, A., and Lau, W. (2020). The language and non-la+nguage benefits of literature in foreign language education: an exploratory study of learners’ views. Lang. Teach. Res. 27, 1120–1141. doi: 10.1177/1362168820972345

Vural, H. (2013). Use of literature to enhance motivation in ELT classes. Mevlana Int. J. Educ. 3, 15–23. doi: 10.13054/mije.13.44.3.4

Witkin, S. (2012). “An introduction to social constructions” in Social construction and social work practice: Interpretations and innovations. ed. S. Witkin (New York: Columbia University Press), 13–37.

Yilmaz, K. (2013). Comparison of quantitative and qualitative research traditions: epistemological, theoretical, and methodological differences. Eur. J. Educ. 48, 311–325. doi: 10.1111/ejed.12014

Zhang, Y. (2023). Can English language teaching in China be improved by the incorporation of English literature? Glasgow: Thesis at University of Glasgow.

Keywords: English education, assessment, literature, content-based language instruction, student perceptions

Citation: Lo N and Shi H (2024) The perceptions of undergraduate students toward reading contemporary fiction in English: a case study of content-based ESL instruction at a self-financed tertiary institution in Hong Kong. Front. Educ. 9:1395168. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1395168

Edited by:

Wei Xu, City University of Macau, Macao SAR, ChinaReviewed by:

Kleopatra Nikolopoulou, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, GreeceWen Gong, Lingnan Normal University, China

Copyright © 2024 Lo and Shi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Noble Lo, bm9ibGUubG9AY3BjZS1wb2x5dS5lZHUuaGs=

Noble Lo

Noble Lo Huiwen Shi

Huiwen Shi