- 1Department of School Education, Government of Punjab, Kasur, Pakistan

- 2Faculty of Education and Humanities, UNITAR International University, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia

- 3Faculty of Business, UNITAR International University, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia

1 Introduction

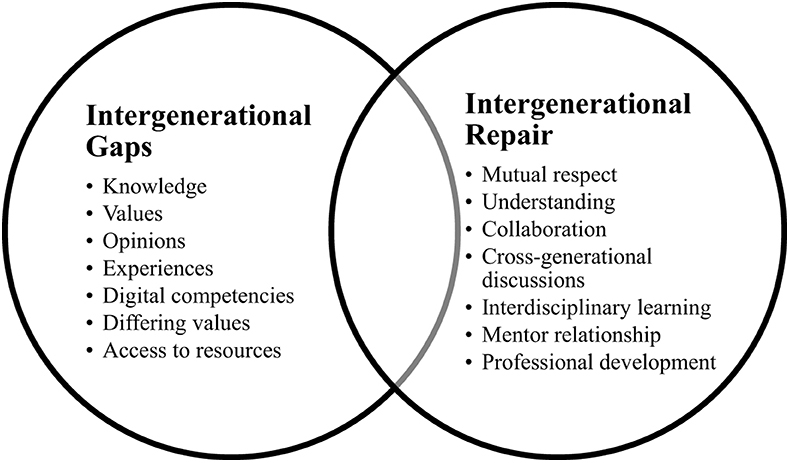

Education is a fundamental entitlement crucial to individual development, upward social movement, and financial wellbeing. Structural inequalities in the educational system in various nations lead to inequities and sustain inequality (Woodman, 2022). The intergenerational gap refers to differences in knowledge, values, opinions, and experiences between individuals of different age groups (Lyons and Kuron, 2014). These variations in formal schooling have been shown to increase structural differences, resulting in an unequal distribution of resources and authority between generations. It is evident from the literature that different steps have been taken, including the exchange of ideas and cooperation between individuals of different age groups, to reduce these intergenerational gaps in the last four decades in developed and underdeveloped countries (Giraudeau and Bailly, 2019).

Intergenerational repair in the classroom involves addressing and managing generational differences and inequalities through educational procedures and practices (Escobar-Galvez et al., 2023). For example, Blanden et al. (2023) argued that generational gaps lead to educational inequalities in terms of attitudes, resources, conceptual understanding, mobility, and performance. Intergenerational repair recognizes past and structural injustices that have led to contemporary educational differences between students and teachers. It aims to narrow the gap between younger and older generations by promoting understanding, respect, and cooperation. Schools can establish a more inclusive and fair learning environment by incorporating both generations' awareness, experiences, and values into the curriculum. This may include integrating local knowledge and traditions into the classroom, fostering intergenerational discussions, and establishing mentorship programs to link students with older community members. This integration might improve the educational experience by offering a more diverse and enriched learning environment (Trujillo-Torres et al., 2023). In addition, they contribute to social cohesion by fostering links between different age groups.

With the advantages of intergenerational repair, it becomes essential to equip students with the skills to navigate and contribute to a rapidly evolving world (Thaning, 2021). Students can gain greater awareness of the world and their role in it by studying the knowledge and mistakes of past generations. This approach promotes students' critical thinking on past and current issues, humanizing a sense of responsibility in building a better and more enduring future (Yembuu, 2021). Furthermore, it enables older people to recognize their value and participate in societal development, confronting age-related misconceptions and fostering a culture that values continuous learning (Christoforou et al., 2021).

2 Literature review

The impact of the intergenerational gap on educational achievement has been extensively studied, yet the results have been inconsistent (Carolan and Lardier, 2018). Several studies indicate that when older people establish connections with their children, it leads to an enhanced level of satisfaction and understanding (Carolan and Lardier, 2018; Giraudeau and Bailly, 2019; Geven and van de Werfhorst, 2020). Education and inequality have been a critical concern in schools since the 1960s (Windle and Fensham, 2024). Research has focused on topics including socioeconomic class, race, ethnicity, age, and gender inequalities in schools, the reasons behind educational inequalities, and the impact of education on either reducing or perpetuating these inequalities (Merolla and Jackson, 2019). Compared to people without disabilities, people with disabilities typically have lower education levels, lower wages, fewer resources in the home, and poorer health. The inclusion of people with disabilities in sociological studies of inequality is rare, even though they constitute more than one-eighth of the US population (Shandra, 2018).

Educational inequalities are influenced by the intergenerational gap between students and teachers (Sadovnik and Semel, 2010). These inequalities pose significant challenges to efficient teaching and learning, resulting in unequal possibilities for academic activities. The effect of the intergenerational gap on educational performance is critical and of pertinent importance. It affects student-teacher communication, class engagement, students' retention, and their performance in class. Teachers and students face challenges in establishing positive interactions and frankness due to variations in age, culture, values, and experiences (Lee and Kim, 2019). Lack of awareness regarding intergenerational gaps and repair hinders student involvement, performance, and motivation and fosters an unfriendly classroom environment.

In addition, intergenerational differences can also promote the continuation of prejudices and biases. Many people do not recognize age prejudice well when they experience it, and some may perpetuate it themselves (Levy, 2009). Prejudice against older adults is a widespread and institutionalized problem in the US (Nelson, 2005). In a societal ecosystem, intergenerational age prejudice creates generational divides between older and younger people because of the isolation of elderly adults and the separation of older and younger generations (Gothing, 2018).

When teachers and students are of different generations, prejudices and biases are more likely to influence their interactions (Wagner and Luger, 2021). Stereotypes and prejudices can influence teachers' perceptions and evaluations of students, resulting in reduced expectations and unequal treatment based on age. Furthermore, the difference in age between generations can directly influence educational opportunities and results (Kranz et al., 2021). Research indicates that children from underprivileged backgrounds are more prone to being taught by older and less experienced teachers. These teachers may lack the necessary skills to understand and tackle the distinct issues encountered by students facing intergenerational gaps from varied backgrounds (Parth et al., 2020).

2.1 Structural injustices

Structural injustice, or systemic inequity, describes how societal systems maintain disadvantages linked to race, gender, class, age, and disability. These structures hinder access to opportunities and achievements, particularly in underprivileged communities. As applied to our current debate, structural injustice expresses itself in several forms, including inadequate access to high-quality teaching, restricted exposure to varied perspectives, and insufficient chances for professional development (Sriprakash, 2023).

The National Center for Education Statistics reported that the average age of teachers in public schools in the United States increased from 42.5 years in 2003-2004 to 44.5 years in 2015–16. Projections suggest that by 2028, ~33% of teachers will be 55 or older (Ingersoll et al., 2021). Similar trends are observed in developed and underdeveloped countries. For example, the first researcher (part of the school education department in Punjab, Pakistan) has witnessed that teachers have not been recruited since 2017. This further reinforces the argument for increasing the age gap between teachers and students. Demographic change has significant consequences for intergenerational interactions in the classroom since older teachers may find it challenging to relate to younger students with varying values, views, and technological skills. Based on our opinion, we presented the details of intergenerational gaps and differences in Figure 1.

The nature of the intergenerational gaps and repairs are interpreted below.

2.2 Generational gap

Generational gaps in schooling are complex phenomena shaped by various socioeconomic, cultural, age, gender, and technological competence-based factors. Older teachers sometimes have traditional views on teaching techniques and curriculum, whereas younger students are more adept at using digital technology and are comfortable with innovative technologies. These differences hinder collaborative learning environments and negatively affect the development of students and teachers.

Martzoukou et al. (2020) revealed that digital competence, which refers to using digital technologies successfully and effectively, significantly differs between older and younger generations. They argue that people who grow up with digital technology, known as digital natives, have an obvious advantage over those who do not, referred to as digital settlers. This gap may cause older schoolteachers to worry about the rapidly changing technology environment.

2.3 Intergenerational repair

The intergenerational gap refers to differences in knowledge, values, opinions, and experiences between individuals of different age groups (Lyons and Kuron, 2014). Intergenerational Repair aims to bridge the gap between students and teachers by fostering collaboration and mutual understanding. This approach promotes respect, understanding, compassion, and shared accountability among individuals to establish a fair and inclusive learning atmosphere. Essential elements of intergenerational repair consist of the following areas that must be focused on.

2.3.1 Cross-generational discussion

Promoting open discourse and attentive listening between older teachers and younger students can foster trust and relationships, allowing the sharing of valuable knowledge and perspectives.

2.3.2 Interdisciplinary learning

Incorporating a more inclusive range of subjects, schools of thought, and perspectives in the classroom can promote critical thinking and creativity among students and teachers, reducing the intergenerational gap.

2.3.3 Mentor relationship

Developing positive interactions between younger students and older teachers can facilitate knowledge exchange and support, improving personal and academic development.

2.3.4 Continuous improvement

Promoting continuous professional development and lifelong learning can also foster flexibility and durability in response to changing situations.

Burger et al. (2020) argued that transmission between different age groups individuals is critical in reducing educational inequalities and social class differences by passing down knowledge and values from one generation of people to the next. We also believe that teachers can address and disrupt these disparities and establish more equitable educational environments for all children by encouraging intergenerational repair.

2.4 Critical analysis

Intergenerational repair has the potential to address structural inequities in education, but several challenges must be overcome before it can be widely implemented. Firstly, a large number of teachers are unaware of the importance of intergenerational repair and its impact on student achievement. Secondly, institutional regulations and policies often do not pay attention to intergenerational equity, leading to a continuous disregard for the needs and issues of marginalized groups of society. Furthermore, incorporating technology in the classroom can reduce issues concerning digital literacy, privacy, and security. Lastly, effectively carrying out intergenerational repair requires a significant allocation of resources for teacher development and training programs, requiring enormous financial and human resources.

To overcome these challenges, stakeholders, including policymakers, students, and teachers, must actively discourage the typical prevailing situation and adopt innovative ways of intergenerational repair. By taking this action, they can break down the systemic inequalities that persist in obstructing the educational goals of young school students worldwide.

3 Conclusion

To eradicate structural inequities in schools, we must repair intergenerational gaps. Schools must focus on fostering respect and mutual understanding between students and their teachers by engaging in cross-generational dialogue, interdisciplinary learning, mentoring relationships, and promoting a culture of continual development. This can contribute to a society developing a more equitable and just learning environment. However, achieving intergenerational repair requires collaborative actions from students, teachers, and stakeholders dedicated to changing the current situation and adopting creative solutions to enduring issues.

Author contributions

AA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. SA: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Software, Writing—review & editing. SH: Writing—review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank UNITAR International University Malaysia for supporting this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Blanden, J., Doepke, M., and Stuhler, J. (2023). Educational inequality. Handb. Econ. Educ. 6, 405–497. doi: 10.1016/bs.hesedu.2022.11.003

Burger, K., Mortimer, J., and Johnson, M. K. (2020). Self-esteem and self-efficacy in the status attainment process and the multigenerational transmission of advantage. Soc. Sci. Res. 86:102374. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2019.102374

Carolan, B. V., and Lardier, D. T. Jr. (2018). Adolescents' friends, parental social closure, and educational outcomes. Sociol. Focus 51, 52–68. doi: 10.1080/00380237.2017.1341247

Christoforou, A., Makantasi, E., Pierrakakis, K., and Tsakloglou, P. (2021). Intergenerational transmission of resources and values in times of crisis: shifts in young adults' employment and education in Greece. Int. Trans. Econ. Self-Sufficiency 12, 237–261. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-17498-9_10

Escobar-Galvez, I., Yanouri, L., Herrera, C. N., Callahan, J. L., Ruggero, C. J., and Cicero, D. (2023). Intergenerational differences in barriers that impede mental health service use among Latinos. Prac. Innov. 8:116. doi: 10.1037/pri0000204

Geven, S., and van de Werfhorst, H. G. (2020). The role of intergenerational networks in students' school performance in two differentiated educational systems: a comparison of between-and within-individual estimates. Sociol. Educ. 93, 40–64. doi: 10.1177/0038040719882309

Giraudeau, C., and Bailly, N. (2019). Intergenerational programs: What can school-age children and older people expect from them? A systematic review. Eur. J. Ageing 16, 363–376. doi: 10.1007/s10433-018-00497-4

Gothing, A. L. (2018). Ageism, Passed Down From Generation to Generation. Available online at: https://scholarworks.merrimack.edu/soe_student_ce/4/

Ingersoll, R., Merrill, E., Stuckey, D., Collins, G., and Harrison, B. (2021). The demographic transformation of the teaching force in the United States. Educ. Sci. 11:234. doi: 10.3390/educsci11050234

Kranz, D., Thomas, N. M., and Hofer, J. (2021). Changes in age stereotypes in adolescent and older participants of an intergenerational encounter program. Front. Psychol. 12:658797. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.658797

Lee, O. E. K., and Kim, D. H. (2019). Bridging the digital divide for older adults via intergenerational mentor-up. Res. Soc. Work Prac. 29, 786–795. doi: 10.1177/1049731518810798

Levy, B. (2009). Stereotype embodiment: a psychosocial approach to aging. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 18, 332–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01662.x

Lyons, S., and Kuron, L. (2014). Generational differences in the workplace: a review of the evidence and directions for future research. J. Org. Behav. 35, S139–S157. doi: 10.1002/job.1913

Martzoukou, K., Fulton, C., Kostagiolas, P., and Lavranos, C. (2020). A study of higher education students' self-perceived digital competences for learning and everyday life online participation. J. Doc. 76, 1413–1458. doi: 10.1108/JD-03-2020-0041

Merolla, D. M., and Jackson, O. (2019). Structural racism as the fundamental cause of the academic achievement gap. Sociol. Comp. 13:e12696. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12696

Nelson, T. D. (2005). Ageism: prejudice against our feared future self. J. Soc. Issues 61, 207–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00402.x

Parth, S., Schickl, M., Keller, L., and Stoetter, J. (2020). Quality child–parent relationships and their impact on intergenerational learning and multiplier effects in climate change education. Are we bridging the knowledge–action gap? Sustainability 12:7030. doi: 10.3390/su12177030

Sadovnik, A. R., and Semel, S. F. (2010). Education and inequality: historical and sociological approaches to schooling and social stratification. Paedagogica Histor. 46, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/00309230903528421

Shandra, C. L. (2018). Disability as inequality: social disparities, health disparities, and participation in daily activities. Soc. Forces 97, 157–192. doi: 10.1093/sf/soy031

Sriprakash, A. (2023). Reparations: theorising just futures of education. Disc. Stu. Cult. Polit. Educ. 44, 782–795. doi: 10.1080/01596306.2022.2144141

Thaning, M. (2021). Resource specificity in intergenerational inequality: the case of education, occupation, and income. Res. Soc. Strat. Mob. 75:100644 doi: 10.1016/j.rssm.2021.100644

Trujillo-Torres, J. M., Aznar-Díaz, I., Cáceres-Reche, M. P., Mentado-Labao, T., and Barrera-Corominas, A. (2023). Intergenerational learning and its impact on the improvement of educational processes. Educ. Sci. 13:1019. doi: 10.3390/educsci13101019

Wagner, L. S., and Luger, T. M. (2021). Generation to generation: effects of intergenerational interactions on attitudes. Educ. Gerontol. 47, 1–12. doi: 10.1080/03601277.2020.1847392

Windle, J. A., and Fensham, P. J. (2024). Connecting rights and inequality in education: openings for change. The Austr. Educ. Res. 51, 89–101. doi: 10.1007/s13384-022-00564-x

Woodman, D. (2022). Generational change and intergenerational relationships in the context of the asset economy. Distinktion J. Soc. Theor. 23, 55–69. doi: 10.1080/1600910X.2020.1752275

Keywords: intergenerational gaps, intergenerational repairs, mutual respect, opinions, value difference

Citation: Amjad AI, Aslam S and Hamedani SS (2024) Exploring structural injustices in school education: a study on intergenerational repair. Front. Educ. 9:1395069. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1395069

Received: 04 March 2024; Accepted: 10 May 2024;

Published: 30 May 2024.

Edited by:

Wang-Kin Chiu, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, ChinaReviewed by:

Lorella Terzi, University of Roehampton London, United KingdomCopyright © 2024 Amjad, Aslam and Hamedani. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sarfraz Aslam, c2FyZnJhem1pYW5AbmVudS5lZHUuY24=; U2FyZnJhei5hc2xhbUB1bml0YXIubXk=

†ORCID: Amjad Islam Amjad orcid.org/0000-0002-4250-7526

Sarfraz Aslam orcid.org/0000-0001-7414-7572

Sharareh Shahidi Hamedani orcid.org/0000-0003-1179-2202

Amjad Islam Amjad

Amjad Islam Amjad Sarfraz Aslam

Sarfraz Aslam Sharareh Shahidi Hamedani

Sharareh Shahidi Hamedani