- 1Department of Cultural Studies and Languages, University of Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway

- 2Norwegian Centre for Learning Environment and Behavioural Research in Education, University of Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway

- 3Stavanger Kommune, Stavanger, Norway

In this article, we will present bias-based bullying episodes shared by Norwegian teachers and preservice teachers when talking about the concept of “discomfort”. We also investigate how “discomfort” and “pedagogy of discomfort” as a tool are reflected in teachers’ and preservice teachers’ prevention and intervention of bias-based bullying episodes. Semi-structured interviews were conducted among seven preservice teachers in their last year of teacher education and seven teachers, with 7–24 years of experience, working in Norwegian schools. Our main findings indicate that the pedagogy of discomfort might be a useful tool to prevent and intervene against bias-based bullying by using the feeling of discomfort that bias-based bullying creates in a constructive way. However, while the preservice teachers are inspired by theories of discomfort and social justice education and are motivated to try those theories out in practice, the teachers are not so familiar with these theories and tend to manage discomfort by avoiding them. By getting more familiar with the pedagogy of discomfort, teachers may improve the classroom atmosphere and make it easier to explore difficult topics in a way that creates room for differences and inclusion, strengthens students’ and teachers’ ability to engage in critical thinking, and thus lowers the risk of bias-based bullying.

Introduction

School bullying and victimization have for several centuries now been a matter of sincere concern among students, teachers, school leaders, parents, and researchers all over the world. Internationally, studies have documented that bullying and victimization have negative consequences on students’ mental health (Reijntjes et al., 2010; Sjursø et al., 2016, 2019) and academic performance (Mark and Ratliffe, 2011; Betts et al., 2017). Although findings in previous studies are somewhat inconsistent, a large body of bullying research has found that racial or ethnic minority and immigrant youth (Pottie et al., 2015; Fandrem et al., 2021), sexual minority youth (Hatchel et al., 2021), youth with disabilities (Blake et al., 2012), and youth living in poverty (Due et al., 2009) are subject to frequent victimization in school. Exposure to such bias-based bullying may be especially damaging, particularly for students who are targeted because of multiple social identities (Mulvey and Cauffman, 2019).

Despite research revealing detrimental outcomes related to bias-based bullying, very few studies have specifically examined what is being done in schools to address bias-based bullying incidents. One recent study has investigated how schools responded to bias-based bullying, indicating that no practical guidance is given on how to manage bias-based bullying (Ramirez et al., 2023). In addition, the study points out that anti-bullying policies against bias-based bullying have focused on protecting minority students in a broad sense by creating inclusive classrooms, focusing on intercultural practices, and having a resource perspective on diversity. Moreover, research has shown that general anti-bullying programs do not succeed in reducing bias-based bullying (Bauer et al., 2007; Espelage et al., 2016), but there is indication that interventions targeting bias-based bullying have shown promising effects (Brinkman et al., 2011). Thus, there is a need for more research that focuses on strategies for preventing bias-based bullying.

Most of the above-mentioned studies have identified bias-based bullying through self-report, and some have included parents (Ansary and Gardner, 2022). However, very few, to the best of our knowledge, use teachers and preservice teachers as informants. Moreover, earlier research has shown that teachers experience discomfort when students express negative or hateful comments against minorities, both regarding racism, immigration, antisemitism, homosexuality, or xenophobia (Røthing, 2007, 2019; Eriksen, 2013; Svendsen, 2014; Thomas, 2016). It is therefore reasonable to assume that bias-based bullying produces feelings of discomfort in educators when they experience it in schools. Hence, this article explores preservice teachers’ and teachers’ experiences with bias-based bullying through their experience with unpleasant or provoking episodes that produce discomfort in diverse school settings. Teachers play a significant role in intervening and preventing bullying and victimization (Baraldsnes, 2021); thus, focusing on strategies for teachers and preservice teachers is important.

The pedagogy of discomfort (Boler, 1999) may be a valuable theoretical resource relevant for gaining knowledge about ways of detecting, preventing, and intervening against bias-based bullying episodes. The pedagogy of discomfort relies on the assumption that feelings of discomfort are important resources that can be utilized to produce change in social processes that sustain social inequities and power imbalances for minorities (Zembylas, 2015). This is relevant since bias-, sometimes also called stigma-based bullying, refers to a form of aggression that stems from social dominance, stereotypes, and prejudice against individuals with socially devalued or stigmatized identities and characteristics, including but not limited to race or ethnicity, sex, sexual orientation disability, physical appearance, weight, and socioeconomic status (Røthing, 2007; Earnshaw et al., 2018; Mulvey and Cauffman, 2019; Fandrem and Skeie, forthcoming). While we subscribe to a resource perspective on teaching in diverse classrooms (Nergaard et al., 2020), we suspect that this approach may prevent us from examining more closely what kinds of topics and situations can create a feeling of discomfort in the classroom. The reflection on discomfort and the context to which it belongs may therefore inform us about how discomfort can be used in a constructive way.

Based on the above-mentioned previous research, gaps in the literature, and arguments, we have outlined the following research questions:

1. How can bias-based bullying be identified as part of teachers’ feelings of discomfort?

2. How are “discomfort” and “pedagogy of discomfort” as tools reflected in teachers and preservice teachers’ prevention and intervention of bias-based bullying episodes?

We hypothesize that knowledge and strategies related to the pedagogy of discomfort can be useful to prevent and intervene against bias-based bullying.

Theoretical framework

Pedagogy of discomfort

“Pedagogy of discomfort” is a concept that can inform work with controversial questions and, as we argue, also be used for preventing and intervening against bias-based bullying. The concept was first introduced by Boler (1999), who emphasized the importance of students learning to question their “cherished beliefs and assumptions” (Boler, 1999, p. 176), and then developed further by Boler and Zembylas (2003). “Pedagogy of discomfort” has been linked to teaching for social justice: “discomforting feelings are important in challenging dominant beliefs, social habits and normative practices that sustain social inequities, and they create openings for individual and social transformation” (Zembylas, 2015). This places the pedagogy of discomfort as a conceptual tool, informing strategies for teaching and learning about social justice and aiming at “social transformation,” thereby including an element of action.

Teaching about social justice

Teaching about social justice is clearly linked to preventing bias-based bullying.

According to Earnshaw et al. (2018), stigma-based bullying refers to power imbalances and can include both intentional and unintentional incidents. Thus, bias-based bullying incidences may also cover more subtle operations of power, such as covert racism (Gillborn, 2006). Kubota (2004) uses the concept of “colorblindness” to describe how many teachers are unwilling to talk about race and racism in their classrooms. A new review study (Fylkesnes et al., 2024) argues that even if there is an increased focus on critical and whiteness studies in the Norwegian context, teacher education still needs to address the question of race and racism in a way that prevents an institutional reproduction of racism.

Kumashiro’s strategies for teaching about oppression

The pedagogy of discomfort draws on various anti-discriminatory and anti-racist traditions that emphasize work for social justice but do not outline direct education strategies.

We will therefore argue the relevance of the work of Kumashiro (2002), identifying four strategies that are used to teach about oppression. These four strategies are: (1) “education for the other,” (2) “education about the other,” (3) “education that is critical of privilege and othering,” and (4) “education that changes students and society.”

Teaching for and about “the other” focuses on promoting empathy and knowledge about minorities. Both of these strategies have strengths since they focus on the school’s responsibility for being aware of and facilitating a diverse classroom. However, for Kumashiro (2002, p. 33), such strategies are also problematic because they indirectly tell us that if minorities had not been present in school, the “problem” would not have been there. That implies a marginalization of students, which makes this strategy counterproductive. He also criticizes the promotion of ‘empathy’ with ‘the other’ for (a) not leading to systemic or structural change and (b) reinforcing a distance between the majority as the “normal” and the minorities as the “suffering other” (Kumashiro, 2002, p. 39). Therefore, he argues that the strategies “education that is critical of privileging and othering” and “education that changes students and society” are more efficient when teaching about oppression. These last two strategies rely on the assumption that understanding and counteracting oppression require more than merely adjusting for—and gaining knowledge about—“the other.” In addition, it is necessary to examine how some groups in society are favored and educate students about strategies to combat oppression outside of school (Kumashiro, 2002). To do so, he argues that teachers must ban all stereotypes and hate speech and, at the same time, train the students’ ability to resist and challenge existing structures. The emphasis must therefore be on self-reflection (where the student asks how he or she is involved in the dynamics of oppression) and self-reflexivity (where the learner brings this knowledge to his or her own sense of self), since knowledge, understanding, and criticism do not necessarily lead to action and social change (Kumashiro, 2002, p. 44).

Kumashiro uses the term “the other” for marginalized groups, a term used to emphasize social, psychological, and symbolic differences in positions and power (Faye, 2021, p. 186). All four strategies are based on a common premise: Oppression is about the fact that some ways of being (or identities) are privileged in society while others are marginalized, and it tries to identify ways to counteract it (Kumashiro, 2002, p. 31). Since bias-based bullying can be seen in relation to social dominance, stereotypes, and prejudice against individuals with socially devalued or stigmatized identities (Earnshaw et al., 2018; Mulvey and Cauffman, 2019; Fandrem and Skeie, forthcoming), the four strategies may make important contributions to the complex task of preventing and intervening against bias-based bullying. This may also be the case when teaching about controversial topics.

The role of teaching controversial issues in addressing bias-based bullying

Because the mechanism behind bias-based bullying can be a controversial topic, teaching about controversial issues and strategies for doing so may complement Kumashiros’ strategies. Trysnes and Skjølberg (2022) identified the following five teaching strategies teachers use when addressing controversial issues: (1) “the conflict avoider,” (2) “the provocatory,” (3) “the discussion leader,” (4) “the empathetic/understanding,” and (5) “the bridge-builder” (our translation). Furthermore, social injustice is often linked to controversial issues, which are defined as ‘issues which arise strong feelings and divide opinion in communities and society’ (Council of Europe, 2015, p. 8). This may require knowledge about complex societal processes, as emphasized by Kumashiro, who argues that to be able to conduct “education that changes society,” teachers need knowledge about both the complex processes that contribute to the maintenance of oppression and about anti-oppressive education (Kumashiro, 2002, p. 68). Such tasks may be complex and challenging but could, however, lead to knowledge that can be used to tackle incidences of bias-based bullying. In the process of developing the competence required to utilize discomfort as a means of preventing bias-based bullying, teachers may acquire insights into the nature of such bullying, including more subtle mechanisms that impede minority groups (Gillborn, 2006). Such enhanced understanding may enable the teachers to identify and intervene in instances of such bullying more effectively. Consequently, this underscores the significance of incorporating the concept of ‘discomfort’ in research related to bias-based bullying.

Limitations of pedagogy of discomfort

There are, however, potential limitations to employing a pedagogy of discomfort that need to be examined critically. Kumashiro (2002) emphasizes that “education that changes society and students” may create crises for the students since it will confront their worldview. Zembylas (2015) discusses the ethical implications of creating and exposing students to discomfort in opposition to a “safe classroom,” which in the Norwegian context is statutory by law (The Education Act, 1998). Røthing (2019) emphasizes the complexity of the concept of “discomfort” and how created (planned) discomfort can be experienced very differently among students. She also recognizes that when “actively working with discomfort as a resource, both for teachers, preservice teachers, and students, it is also important to develop an awareness to meet and take care of students’ discomfort, both when it is planned for and expected and when it rises unexpectedly in daily collaboration” (Røthing, 2019, p. 53, our translation). Røthing (2019) also discusses the dilemma when the aim of creating comfort in the classroom is challenged by creating discomfort. She argues for the importance it can have to create critical reflection and inclusion, even if it may cause discomfort for students and teachers.

Methods

Our first research question focuses on how discomfort is experienced by preservice teachers and teachers. This assumes that “discomfort” can be used as an experience-near concept, capturing the everyday situation of educators. We also draw on ‘discomfort’ as an experience-distant concept with the potential to inform both the analysis of empirical data and the discussion of normative approaches to bias-based bullying. A qualitative design with personal interviews was employed. Since discomfort within a teaching situation may bring personal experiences that can be sensitive, we chose individual interviews, aiming to create a space for sharing more. The research process followed standard procedure (Kvale and Brinkmann, 2015): formulating the research question, selecting the sample, defining the categories to be applied, outlining the coding process, implementing the coding process, determining trustworthiness, and analyzing the result of the coding process.

Procedure

A semi-structured interview guide developed by the researchers in the project was created to ensure consistency in the line of enquiry during each interview (Patton, 2014). The interviews started with some background information about the informants, whether they were teachers or preservice teachers, what kind of teaching experience they had, and which grades they taught (age of pupils). Then we introduced the concept of discomfort, how the informants defined the concept, and various aspects concerning the concept of discomfort in the diverse classrooms. We were interested in their experience, or thoughts about, when planning for controversial topics and how informants had witnessed or experienced and handled situations related to discomfort—either concerning teachers, pupils, or both. We were also interested in the way the preservice teachers and teachers expressed their feelings connected to discomfort. We also asked the informants about how systemic factors related to discomfort were handled in their schools. Did they have time and “space” to talk about these matters? What kind of routine did the administration have to handle cases? What resources are schools given (time, staff) to handle situations that may occur?

Fourteen interviews were conducted in neutral meeting rooms near the informants by two of the researchers in the project. The interview lasted from 30 to 60 min and was recorded and fully transcribed by one of the participants in the research group. The interviews were conducted and transcribed in Norwegian, and the quotes used in this article are translated by the authors.

Sample

The sample consisted of seven preservice teachers in their last year of teacher education and seven teachers working within Norwegian schools with 7–24 years of experience. The reason for choosing these two groups was to give us the possibility to compare possible differences between preservice teachers and teachers and to gain different perspectives that could enrich the data.

Due to practical reasons, the informants were recruited by self-selection. However, this strategy also provided an opportunity to talk to the “meatiest, most reliable sources” (Miles and Huberman, 1994). The preservice teachers were chosen through one of the researcher’s networks because they enrolled in programs that are linked to the topic of this study. The teachers were recruited through another of the researcher’s contacts in primary schools in the region and chosen because they had been teachers for many years.

However, to avoid ethical considerations, the interviewer who interviewed the preservice teachers did not know the students personally and had not been part of any evaluation process of their work. The interviewer who interviewed teachers knew some of the respondents, but none of the informants are close friends with the interviewer. A disadvantage here may be that the informants are perhaps not so willing to be critical of the questions and topics discussed because there is this personal link. On the other side, it created intimacy where the teachers talked about episodes of discomfort that they usually do not talk about. Despite the possible disadvantages, both for practical reasons and because we think that the informants will more easily share their experience with this person than with a complete stranger, we chose this way of getting informants.

Analyses

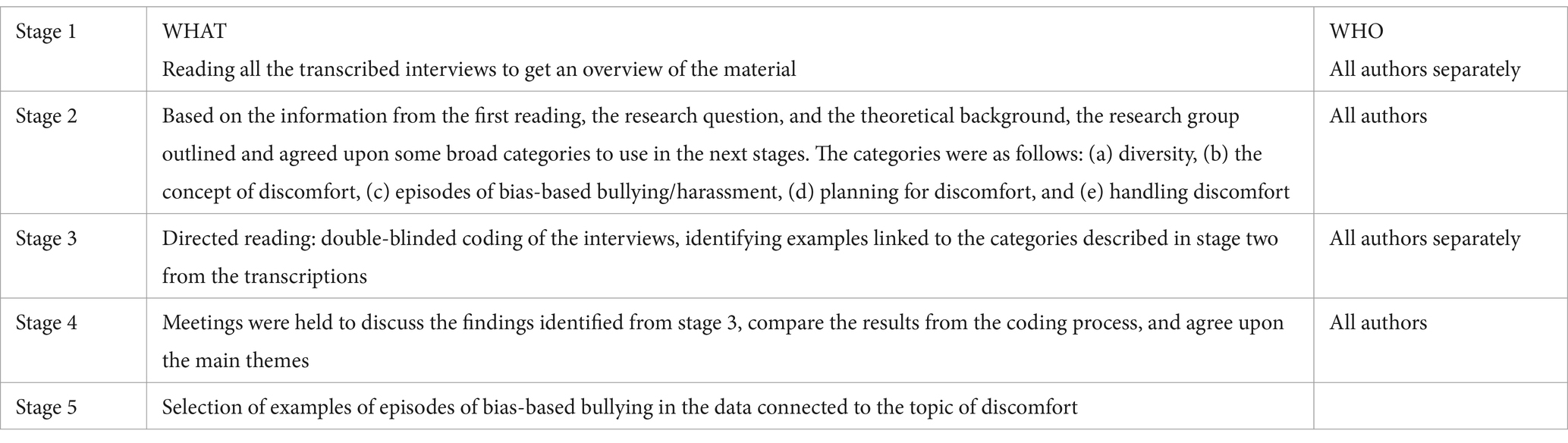

The process was guided by a theory-driven content analysis approach (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005), and we have described the different stages closer in Table 1.

Validity

The fact that we have been a group of researchers working together through the different stages of the study can increase the study’s validity. According to Kvale (1996), validity in qualitative research has to do with questioning, checking, and theorizing the findings. He also says that dialog is a central concept in the validation process. Johnson and Christensen (2017) use the concept “critical friend” as important for the validity of different stages of a study, and we have been acting as critical “friends” for each other throughout the process.

We have also tried to describe the study as accurate and detailed as possible (Johnson and Christensen, 2017). Moreover, both the researchers conducting the interviews have a form for shared experiences with the informants that may strengthen the emic validity. The researcher who interviewed the preservice teacher has a teacher education background herself and has experience from teaching in teacher education. The researcher who interviewed the teachers has the same background as them: extensive experience working as a teacher in primary education and experience from teaching in teacher education. All researchers are from the field of educational research, which strengthens the emic validity.

Ethics statement

The study is conducted according to the National Guidelines for Research (NESH), reported, and approved by the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research (SIKT). All informants were informed about the implications of participating in the interviews, about the formalities of data collection and storage, and about their right to withdraw from the study at any point they liked. When citing the informants, we have aimed to do this in a respectful way, also taking into consideration the difference between oral and written language. As Johansen and Vetlesen (2000, p. 188) emphasize, word-by-word representations can also be unethical if they are presented out of context and from the intentions of the speakers.

The content of the study deals with highly value-laden issues, which means that ethical considerations have been a central part of the collaborative work with setting up the study and writing the article. We are well aware of the normative aspects involved, and they are treated as explicitly as possible throughout the article.

Results

The diverse classroom—overview of findings

Today’s classrooms are diverse in unpredictable ways. In our data, we found examples of informants giving examples of different types of diversity. Some talked about individual differences between pupils—pupils with different diagnoses—and others referred to the different academic levels pupils have. Some other group-based categories that came up were nationality, ethnicity, culture, religion, and sex. Some of these categories can potentially lead to bias-based bullying, as argued in the introduction and theoretical presentation.

With this as a background for what “our” diverse classrooms were like, the results will be outlined by first detailing certain situations reported by our informants inducing discomfort, which we categorized as instances of different kinds of bias-based bullying. Then we will present some findings we have categorized related to our research questions. We intentionally refrained from direct queries regarding bias-based bullying or victimization, opting instead to pursue a more expansive exploration of the overarching concept of discomfort. We did, however, ask the preservice teachers and teachers if they had examples of episodes that had created the feeling of discomfort, either for them or their students (or observed episodes), and these episodes gave us some valuable insights and findings to help us answer our research questions.

Examples of bias-based bullying episodes

Race and ethnicity were detected in some of the examples we found in the data as something that caused bias-based bullying, as we interpret it. Our informants mentioned several episodes where students were given comments about their appearance (afro hair, brown skin, etc.). Some of the informants commented that this may be described as a micro-aggression because it was not repeated over time.

An example from the data was a question like “Do you use a turban?” While such inquiries may ostensibly be driven by genuine curiosity, our analysis underscores the nuanced dimension whereby such questioning may also be deemed “unnecessary,” thereby instigating discomfort for the individual subjected to such inquiries.

Additional instances discerned within the dataset include observations where remarks could be linked to cultural backgrounds, such as a student commenting “Ni Hau” repeatedly to a girl of Asian background:

He says “Ni hau”, in a teasing way, and repeat it for the whole class to hear—probably around twenty times … And she (the girl) gives me (sighs), a resigned glance, in a way … like she is a little disappointed, resigned … and that is the pupil (the boy saying this comment). I have heard a lot about in that class, that can be difficult, this is a class where many of the pupils—especially the girls—have problems staying—they eat in another room instead of in the classroom—because actually there are many cases of bullying in that class, but I thought—when she gave me that glance … so much sympathy for her, in a way—it must be hard to deal with … especially in a class that most pupils are ethnic Norwegian, you are more different, in a way, so it was, like … ah…. (Preservice teacher, 7)

This example shows a feeling of discomfort both for the students and the preservice teacher and can be defined as an example of bias-based victimization.

Some episodes that can be more linked to racism also surfaced within the dataset. In one class, a student said that he would just have “light-skinned pupils” on his birthday, and that resulted in one of the dark-skinned students in class going home and trying to “wash away” his skin color.

Other episodes were about topics like politics and religion. There were examples of students saying non-acceptable words and utterances in class, like the n-word, and in one situation, a student was shouting “Heil Hitler” in class.

Some other examples were connected to religion: a preservice teacher wore a hijab, and students started to shout “Allah Akbar” during a break. This created a strong feeling of discomfort in a fellow preservice teacher (our informant). Another example was a student laying down and pretending to pray in an Islamic way. In one classroom, the children were playing, and one boy acted as the boyfriend of a girl in the class. Another student commented that “a Muslim cannot be a boyfriend to a non-Muslim.” The informant reported that this created discomfort in the student who was given this comment, and the teacher felt uncomfortable when considering how to react.

How are “discomfort” and “pedagogy of discomfort” as tools reflected in teachers and preservice teachers’ prevention and intervention of bias-based bullying episodes?”

To be able to react to bias-based bullying, they first need to be detected, and one of the teachers commented that this is not always easy:

Those glances (…) are very hard to catch because this usually happens behind the teacher’s back. So, one needs to be very observant and skilled at it because it is very challenging. For some reason, I am very good at it. (Teacher, 3)

When examples of bias-based bullying episodes were talked about in the interviews, different strategies for handling them also came up.

The overall impression was that teachers appeared to really want to intervene against bullying. Here is an example of this:

You do everything you can to protect the other students. Often, you step in, especially student against student, as that's where things often happen—whether with racist remarks or physical aggression. You have to intervene, and then it's us who receive the violence that was originally meant for that student. (Teacher, 1)

There were also reported incidents where teachers can be interpreted as wanting to intervene against bullying but do not see them as examples of what we would categorize as bias-based bullying connected to race/racism:

Some new students arrived … they had black skin … one of them faced some teasing. He did not understand what they were saying … so when the teacher came in and explained that one of the insults he used was 'You, brown cheese' to the others (hahaha). because he did not realize it was an offensive term. So, he continued to use it (hahaha) then that word did not have an effect in that sense. He didn't feel that it was the skin color that made a difference. (Teacher, 3)

That time when the student who said so many nasty things and tried to kick and hit the other students (that were colored) I had to have a long conversation with them afterward, so that they wouldn't take it personally. I tried to say that you were a random target. I had to try to say it so that they wouldn't feel that it was very racist. (Teacher, 1)

We also found interesting reflections in the teacher interviews about discomfort being a “natural” element related to being in the teacher profession—something one had to learn to cope with—and that students also had to learn to be able to cope with discomfort.

Some of the preservice teachers emphasized how they would provide information when incidents that were not directly bias-based bullying episodes occurred but which may be interpreted as bias-based bullying by some:

Once when someone said 'Heil Hitler' … It is about providing information, making them aware of what this actually means, and that it's not something we want in the classroom.' (Preservice teacher, 2).

Another preservice teacher said:

A student shouted 'Allahu Akbar' in class all the time. He was not religious himself. So, I explained to him why he could not say that, why it could be uncomfortable or derogatory for someone who follows this religion. (Preservice teacher, 3)

The actions reported by the preservice teachers can be interpreted as using an approach to episodes of bias-based bullying in the classroom where they intervened by adding a knowledge component to the situation. This component consisted of information about what types of social processes could provoke prejudices.

Related to one of the findings above, some students were bullying a preservice teacher wearing a hijab during her field practice placement in a school, shouting “Allah Akbar.” This happened during the preservice teachers’ “practice period” in recess:

Some students shouted «Allah Akbar»; and I looked at her and asked: Did they say what they said?! and she answered, «yes, but is ok»; and I answered, «no, it is not ok». And I thought at once that this is not just about her, it is more about the school’s culture, that you should feel safe. And is actually one of the pupils in that group who ran to the stairs and said «it wasn’t me»; and I noticed that he had dark skin himself, and he probably felt that he had to say it wasn’t him, so he shouted it…. (Preservice teacher, 3)

The preservice teacher explains further that the incident was reported to the department leader subsequently for the current grade level in the school. Initially, this teacher displayed unease and reluctance to address the issue. However, later that evening, he sought the contact information of the preservice teacher involved, and the following day, he convened a meeting with the students implicated in the incident. Consequently, prompted by the preservice teacher’s intervention, the school initiated the meeting and engaged the administration. Instances in our dataset also revealed that the preservice teachers expressed surprise at the perceived inadequacy of existing protocols in practice schools for addressing such occurrences.

Preventing bias-based bullying episodes: teaching using the pedagogy of discomfort or planning for discomfort

To explore how discomfort could be used as a source to prevent bias-based bullying, the respondents were asked whether they had used discomfort as a constructive source when they were planning their teaching. Here, an evident discrepancy emerged within the dataset between the teachers and the preservice teachers. Most of the teachers had not planned for or thought about planning for discomfort in the classroom, commonly responding, “(…) have not thought about that” (Teacher 1). Other teachers explained the reason for not incorporating discomfort in their teaching by referring to the subjects they were teaching (often science or religion) or that other professionals (such as the school nurse) were teaching the subject/theme that was perceived as discomfortable (e.g., abuse; Teacher 2, pp. 2–4).

Some of the preservice teachers, however, shared more reflections around their plans for incorporating discomfort into their practice: “I find that interesting, I remember we read an article about that using discomfort as a source also has positive repercussions, that it is important to show that one dares to talk about those things that are discomfortable. That has positive effects, especially for those students who might not dare to talk about things, and if you don’t talk about those things yourself, you cannot expect the students to do it” (Preservice teacher 3).

To avoid bias-based bullying episodes when teaching discomfortable subjects, both teachers and preservice teachers mentioned that it was important to be well prepared and read a lot in advance of the lectures. However, there were some differences between the groups when they talked about planning lessons on controversial topics that may create possible bias-based bullying episodes.

One of the teachers said:

(…) When I am going to teach about a religion that I know is represented in the class, and that I have read about, the students that is in the class can perceive or experience the religion different than what they learn at home and that makes me want to do things “right (Teacher 6).

Another said:

(…) If I have been teaching religion, I have tried to use the students that know more than me to promote them in a positive way, that they can teach the others, and try to make the other students think wow (Teacher, 1).

These extracts, showing teachers wanting to present a certain religion in a correct way and using pupils representing a certain religion to present it to the class with the intention of boosting these students, can be interpreted to represent the resource perspective on how to deal with diversity.

The preservice teachers mentioned several examples of having planned the use of discomfort to make students reflect critically. Here is one example:

We had a teaching lesson where we created discomfort in the classroom, where we said claims where the students should go to one of the sides of the classroom if they agreed and the other side if they disagreed. One of the examples was that Norwegian employees should not hire workers from other countries. Then we made it really, really clear that this is a safe space, and you are allowed to say your opinion whether you agree or disagree, and you will be allowed to explain why you had that opinion. Many of the students disagreed with the others, so the positive about the discomfort is that you can develop critical thinking and independence…. (Preservice teacher 5)

This is a good example of how to plan for discomfort, to “develop critical thinking and independence,” as the preservice teachers say, and it is different from teaching something “right.”

Discussion

In this article, we have identified episodes of bias-based bullying by asking preservice teachers and teachers about their experiences with discomfort. Our results highlight that first, bias-based bullying (both intentional and unintentional acts) clearly produced a feeling of discomfort for the informants. Second, examples of what we interpret as bias-based bullying episodes were linked to remarks about skin color, cultural backgrounds, ethnicity, religion, and excluding students from social interactions due to skin color. Mostly, it is children who bully each other, but there is also one example mentioned where students bullied a preservice teacher because of her religion.

Thereafter, we used the pedagogy of discomfort as an analytic framework for investigating how the teachers handled these incidences of bias-based bullying to investigate to what extent such pedagogic strategy might be a tool for preventing and intervening against bias-based bullying episodes in schools. The teachers uttered that such incidents might be hard to detect, and despite a great wish to protect their students, there were examples of situations where bias-based bullying episodes were handled without addressing the bias. The preservice teachers showed more awareness and had a more direct approach to addressing the bias in their examples of bias-based bullying episodes.

Our findings also showed that the teachers tried to avoid discomfort in the classroom, while preservice teachers are more motivated to try out the potential of using planned discomfort in their teaching. As an extension of this, we suggest that the pedagogy of discomfort can be used as a tool to increase awareness—and thereby the ability to intervene against bias-based bullying.

Exploring the potential productivity in the relationship between bias-based bullying and discomfort

Being exposed to bias-based bullying may have detrimental outcomes (Mulvey and Cauffman, 2019). Thus, it is concerning, but not surprising, that our findings indicate that bias-based bullying is present within Norwegian schools. Previous research has already confirmed that students with devalued or stigmatized identities are subject to frequent victimization in schools (Due et al., 2009; Blake et al., 2012; Pottie et al., 2015; Hatchel et al., 2021), which is also verified through the findings in this study. The fact that the bias-based bullying episodes found in this study were identified without asking directly about them suggests that bias-based bullying is a matter of sincere concern in Norwegian schools today. Additionally, through this question formulation, we clearly identified that bias-based bullying produced discomfort for the informants. The themes they brought up as discomfortable were in line with previous research on what teachers might experience as uncomfortable to talk about and respond to in the classroom, such as, e.g., ethnicity, hateful comments against minorities, and antisemitism (Røthing, 2007, 2019; Eriksen, 2013; Svendsen, 2014; Thomas, 2016). Thus, bias-based bullying seems to produce feelings of discomfort, enabling a discussion about how pedagogical strategies use discomfort as a constructive source for overcoming this issue.

However, it seemed like there was a difference in what was interpreted as bias-based bullying between teachers and preservice teachers. Some of the examples given by the teachers could be linked to the theory of “colorblindness” (Kubota, 2004): The examples connected to ethnicity and skin color were not seen as bias-based bullying but explained as “random incidents” of non-biased bullying, which may indicate that the teachers handled bias-based bullying episodes like non-bias-based bullying. Such findings may be underscored by previous research stating that racism does not get enough attention, neither in teacher education nor in schools (Dowling, 2017; Osler and Lindquist, 2018; Flintoff and Dowling, 2019; Fylkesnes et al., 2024). Distancing oneself from racism by referring to it as something that can only happen elsewhere or at another time is a typical response from teachers in discussions about what racism entails (Faye, 2021, p. 191). One interpretation of this could be that bias-based bullying produced a feeling of discomfort for the teachers, which hindered them from viewing these episodes as bias-based bullying. Another explanation may be awareness of what might be interpreted as bias-based bullying.

The latter was expressed by one of the teachers, who stated that such incidences are hard to spot (transcription, teacher 3). According to Earnshaw et al. (2018), stigma-based bullying refers to power imbalances and can include both intentional and unintentional incidents. Thus, our understanding of bias-based bullying incidences also covers more subtle operations of power, such as covert racism (Gillborn, 2006), hindering minority students. Such incidences might be hard to detect, and if so, thereby calling for an awareness of what might be interpreted as bias-based bullying.

“You do everything you can to protect the other students”: tackling bullying not specific to bias-based bullying—good intentions with potential harmful outcomes

The teachers’ willingness to protect their students was prevalent in the interviews. Despite the good intention of protecting their students, handling bullying that is not specific to bias-based bullying might be problematic for several reasons. First, as stated, general anti-bullying programs do not succeed in reducing bias-based bullying (Bauer et al., 2007; Espelage et al., 2016), but programs assessing bias-based bullying specifically have shown promising effects (Brinkman et al., 2011). Second, it is emphasized elsewhere that students with minority backgrounds experience more discomfort with not being taken seriously than addressing racism as a topic within the classroom (e.g., Faye, 2021). The teachers’ examples of how they handled the incidence of bias-based bullying in the situations referred to in the interviews could be interpreted as general bullying and are similar to what is found in other studies.

When looking at the responses from the preservice teachers, even if most of them do not have much experience from the classroom, they report some interesting incidents that indicate that pedagogy of discomfort may be a productive way of increasing awareness and action toward bias-based bullying. The preservice teachers uttered specific components of bias-based bullying, describing experienced situations. They explained that a component of why it is especially damaging to utter hateful comments about minorities is important for effective interventions against such acts of hatred and thereby support the assumption that challenging dominant beliefs, social habits, and normative practices that sustain social inequities are important to achieve social transformation (Zembylas, 2015). The preservice teachers’ examples may thus support the hypothesis that it is important to include specific components addressing social justice to intervene against bias-based bullying.

Regarding racism, research has argued that it should not only be linked to obvious acts of hatred but also to the more hidden and subtle operation of power leading to hindrances experienced by minority groups (Gillborn, 2006). Institutional racism, in this light, is often non-obvious and non-aggressive. Not including discomfort as a source to avoid bias-based bullying in terms of talking to the students about the processes that make some identities privileged might obscure these subtle actions of social exclusion happening in the schoolyard. This can also be explained by the theory of “colorblindness” (Kubota, 2004) and the unwillingness to talk about race and racism in the Norwegian school context (Osler and Lindquist, 2018 and others).

However, it is not only the teacher’s responsibility to handle bias-based bullying. Collaboration with the principal and leader group at the schools is crucial to managing this serious issue. The examples given by the preservice teacher, where the department leader displayed reluctance to address the issue, may be a potential threat to handling bias-based bullying in schools. Ramirez et al. (2023) also argue that no practical guidelines are given on how to manage bias-based bullying, which might shed light on why the teachers addressed the bias-based bullying incidences as non-bias-based bullying. If so, this article also poses an argument for the need for practical guidelines on how to intervene against bias-based bullying both at the teacher level and at the school level.

Pedagogy of discomfort—a way to prevent bias-based bullying?

As the above-mentioned discussion has revealed, there may be a need for increasing awareness about bias-based bullying in Norwegian schools. As argued, one way to do this might be through knowledge and the use of pedagogy of discomfort. Such pedagogy has the potential to strengthen the knowledge base and perspectives needed to detect and act upon both direct and more subtle forms of racism and take actions against them. The teaching strategy “education for and about the other” (Kumashiro, 2002), for instance, may be fruitful, since focusing on students who are “othered” and providing “right” knowledge about minorities, or teaching in culturally sensitive ways that avoids the subjects that can lead to discomfort. In addition, other findings can be analyzed with the help of Kumashiro’s categories.

However, according to the question on how the teachers used discomfort as a resource when planning lectures, in line with Ramirez et al. (2023), our informants focused on minority students in a broad sense by creating inclusive classrooms, focusing on intercultural practices, and having a resource perspective on diversity (Nergaard et al., 2020; Ramirez et al., 2023), and it seems that the pedagogy of discomfort teaching is not something familiar to them. Teachers also articulated instances of high-stress daily situations within the classroom environment, characterized by a multitude of behavioral issues, including instances of physical violence. These exigencies demanded and absorbed most of their attention, potentially contributing to a diminished focus on matters related to bias-based bullying. The fact that the interviewed teachers have worked for many years suggests that these critical perspectives may be more prominent in current teacher education compared to earlier periods due to more awareness of these issues today compared to earlier.

Furthermore, there were several episodes in our data when teaching about religion where teachers seemed concerned that the subject knowledge was “correct.” This seemed to produce unease about their own subject knowledge and the possibility that controversial issues might arise. To solve this, they sometimes used the students as “experts” in the teaching situations. This could be interpreted as an approach to stimulating empathy among the students toward a potentially controversial religious tradition that was on the agenda. This could lead to maintaining oppression and upholding a too strict distinction between “us” that are emphatic and “them” that are suffering (e.g., Kumashiro, 2002, p. 39). Thus, this way of teaching may unintentionally result in the opposite: that one identity appears to be representative of a diverse religion or culture.

According to the tendency to avoid discomfort we found, it is important to challenge the view that meeting one’s own prejudices cannot be equated with the minority experiences of being exposed to bias-based bullying or repeated oppression. It is emphasized elsewhere that students with minority backgrounds experience more discomfort with not being taken seriously than addressing racism as a topic within the classroom (e.g., Faye, 2021). Studies from the Norwegian context show that learning about racism in teacher education and being directly talked about in schools need more attention (Dowling, 2017; Osler and Lindquist, 2018; Flintoff and Dowling, 2019; Fylkesnes et al., 2024). Faye (2021, p. 191) found that distancing oneself from racism by referring to it as something that can only happen elsewhere or at another time is a typical response from teachers in discussions about what racism entails.

The preservice teachers promote the importance of opening up for different opinions as well as the uncomfortable ones, which is a central thought in the pedagogy of discomfort (Boler, 1999). The fact that the preservice teacher emphasizes that this way of teaching can raise independence can be linked to “Education that Changes Students and Society,” which is concerned with the ability to resist and challenge existing structures (Kumashiro, 2002, p. 50). The fact that the preservice teachers in our study are more open to the pedagogy of discomfort tells us that they have some knowledge of this topic and are willing to put it into practice. Our informants, as mentioned, were self-selected for this study, and it can be that they

Obstacles and restrictions—encompassing time constraints and limited resources

On the other hand, there is a need to highlight the potential problematic issues of using the pedagogy of discomfort. One potential limitation uttered by the teachers and preservice teachers with incorporating discomfort as a tool to prevent bias-based bullying is the resources required. This is also emphasized by Kumashiro: the teacher needs knowledge about both the complex processes that contribute to the maintenance of oppression and about anti-oppressive education (Kumashiro, 2002, p. 68), a task that requires a lot of time and available resources. The teachers describe a stressful working environment with many things to handle, and the main impression is that they want to avoid discomfort. The preservice teachers do not yet have the same degree of experience in day-to-day life in the classroom, nor do they have the same responsibilities. But perhaps through their recent teacher education, they are more familiar with the concept of discomfort as a concept that can be used in teaching to work with inclusion and critical thinking and challenge pupils’ attitudes. Considering the fact that bias-based bullying is a matter of serious concern, leading to detrimental outcomes for those exposed to it, it is worrying that the teachers explain these work situations.

Limitations of pedagogy of discomfort to prevent and intervene against bias-based bullying can be the lack of sufficient resources schools are given to work with this, both when it comes to staff and time. There is also a lot of pressure on teachers to reach the different learning goals, and to stop and take time to answer “difficult questions” might seem difficult. The fact that there are so many daily challenges that teachers meet that need their immediate attention might be a reason that teachers might be reluctant to create discomfort—or to see this as a useful way to cope. The findings in our data that preservice teachers were more positive about using the pedagogy of discomfort in their teaching may be explained by the fact that this is knowledge they have gained through their recent teacher education, and the motivation newly educated professionals often bring with them to be eager to try out their theories in practice.

The recourse situation in Norwegian schools with students with different diagnoses and behavioral issues expressed by the teachers that they are not followed up by insufficient resources can play a part and hinder teachers from teaching and reacting in the way they would have wanted to, having time and access to more staff, for example. The preservice teachers also reported the importance of having time to build good relations with students before one would start to use pedagogy of discomfort to address controversial issues. As Røthing (2019) pointed out, teachers must be able to know how to help students who may experience a feeling of crisis when getting their beliefs challenged. The ethical implications of the pedagogy of discomfort are also something discussed by Zembylas (2015), as we have referred to earlier, and are something that is important to bear in mind when using this approach in the classroom.

Limitations and further research

One limitation of this study is that it consists of a limited number of informants, all of whom were self-selected. In addition, the fact that there were two different interviewers conducting the interviews for the two groups may lead to different follow-up questions and perspectives than if both interviewers had been present in all interviews.

For further research, it would be interesting to increase the knowledge of how teachers in Norway define and have experienced bias-based bullying, and how this phenomenon is handled both on a systemic level and by the individual teacher. It would also be interesting to study more experiences with using the pedagogy of discomfort in classes and the effect it may have, both on critical thinking from a general perspective and on the possible effect it might have to reduce bias-based bullying. Even though the interview guide was used as a base for the interviews, the interactions between informants and interviewers, and the fact that there were two different interviewers conducting the preservice teachers’ interviews may have caused differences in the answers from the respondents.

Conclusion and practical implications

The findings in our study strengthen our hypothesis that pedagogy of discomfort might be a useful approach to prevent and intervene against bias-based bullying, and using pedagogy of discomfort as an analytic framework gave us the possibility to explore bias-based bullying from a new perspective. The prevention part can be strengthened by creating a classroom atmosphere where controversial issues are not avoided but are something that pupils learn about, learn to be aware of, reflect on, and act upon. The pedagogy of discomfort can also help teachers to be more aware of different power relations and systemic factors that can cause discrimination and, in this way, be better prepared to detect bias-based bullying. To intervene against bias-based bullying, it is important to acknowledge and accept the fact that bullying episodes in fact are bias-based (as in racism, for example) and to be able to handle them in a different way than other bullying episodes. Strategies for teaching about controversial topics can also be useful as strategies for tackling bias-based bullying episodes. In a concrete bias-based bullying episode, the teacher might not be so afraid of confronting the one who bully with the attitude the behavior is an expression of. In essence, we thus argue that the pedagogy of discomfort may play a pivotal role in creating more inclusive learning environments in the diverse classroom.

In addition, as our study shows that preservice teachers are more aware of the pedagogy of discomfort than teachers, this pedagogy could be a topic for in-service training for teachers. It could also be used more directly in field practice periods as a theoretical approach for tasks for preservice teachers to try out (working with controversial topics), and then the practice schools would also be more familiar with this way of working. It is also important to constantly argue for more resources for schools (time and personnel) and that awareness about racism and othering is something the whole school must have—even if it creates discomfort. To ensure that there are good systemic administrative practices to handle situations that may occur, it is also important.

Finally, more knowledge about what bias bullying is, how it differs from “ordinary” bullying, and how to prevent and intervene against it is something that should receive more attention, both in teacher education and in-service training and among experienced teachers generally.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by SIKT—Kunnskapssektorens tjenesteleverandør. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

WT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration. AM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Formal analysis. KL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis. GS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Formal analysis. HF: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Formal analysis.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ansary, N. S., and Gardner, K. M. (2022). American Muslim youth and psychosocial risk for bullying: an exploratory study. Int. J. Bullying Prev., 1–18. doi: 10.1007/s42380-022-00142-w

Baraldsnes, D. (2021). Bullying prevention and school climate: correlation between teacher bullying prevention efforts and their perceived school climate. Int. J. Dev. Sci. 14, 85–95. doi: 10.3233/DEV-200286

Bauer, N. S., Lozano, P., and Rivera, F. P. (2007). The effectiveness of the Olweus bullying prevention program in public middle schools: a controlled trial. J. Adolesc. Health 40, 266–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.005

Betts, A., Bloom, L., Kaplan, J. D., and Omada, N. (2017). Refugee economies: forced displacement and development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Blake, J. J., Lund, E. M., Zhou, Q., Kwok, O. M., and Benz, M. R. (2012). National prevalence rates of bully victimization among students with disabilities in the United States. Sch. Psychol. Q. 27, 210–222. doi: 10.1037/spq0000008

Boler, H., and Zembylas, M. (2003). “Discomforting truths: the emotional terrain of understanding differences” in Pedagogies of difference: rethinking education for social justice. Ed. P. Tryfonas (New York: Routledge Falmer) 117–131.

Brinkman, B. G., Jedinak, A., Rosen, L. A., and Zimmerman, T. S. (2011). Teaching children fairness: decreasing gender prejudice among children. Analyses Soc. Issues and Public Policy, 11, 61–81.

Council of Europe (2015). Teaching Controversial Issues. Available at: https://edoc.coe.int/en/human-rights-democratic-citizenship-and-interculturalism/7738-teaching-controversial-issues.html

Dowling, F. (2017). «‘Rase ‘og etnisitet? Det kan ikke jeg si noe særlig om–her er det ‘Blenda-hvitt’!» Lærerutdanneres diskurser om hvithet, «rase» og (anti) rasisme. Norsk pedagogisk tidsskrift 101, 252–265. doi: 10.18261/issn.1504-2987-2017-03-06

Due, P., Merlo, J., Harrel-Fisch, Y., Dalsgaard, M. T., Soc, M. S., Holstein, B. E., et al. (2009). Socioeconomic inequality in exposure to bullying during adolescence: a comparative, cross-sectional, multilevel study in thirty-five countries. Am. J. Public Health 99, 907–914. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.139303

Earnshaw, V. A., Reisner, S. L., Menino, D. D., Poteet, V. P., Bogart, L. M., Barnes, T. N., et al. (2018). Stigma-based bullying interventions: a systematic review. Dev. Rev. 48, 178–200. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2018.02.001

Eriksen, I. M. (2013). Young Norwegians. Belonging and becoming in a multiethnic high school. Dissertation for the degree of PhD. University of Oslo, Faculty of Humanities.

Espelage, D. L., Rose, C. A., and Polunin, J. R. (2016). Social-emotional learning program to promote prosocial and academic skills among middle school students with disabilities. Remedial Spec. Educ. 37, 323–332. doi: 10.1177/0741932515627475

Fandrem, H., and Skeie, G. (forthcoming). “What is a safe and good learning environment in a diverse classroom? Bias-based bullying and religious education in Norwegian schools” in Handbook of school violence, bullying, and safety. eds. J. S. Hong, A. L. C. Fung, and J. Lee (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing).

Fandrem, H., Strohmeier, D., Caravita, S. C. S., and Stefanek, E. (2021). “Migration and bullying,” in The wiley blackwell handbook of bullying: a comprehensive and international review of research and intervention. Eds. J. O. Norman and P. K. Smith (Wiley Blackwell), 361–378.

Faye, R. (2021). “Rom for ubehag i undervisning om rasisme i klasserommet” in Hvordan forstå fordommer? Om kontekstens betydning–i barnehage, skole og samfunn (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget).

Flintoff, A., and Dowling, F. (2019). ‘I just treat them all the same, really’: teachers, whiteness and (anti) racism in physical education. Sport Educ. Soc. 24, 121–133. doi: 10.1080/13573322.2017.1332583

Fylkesnes, S., du Plessis, D., and Massao, B. P. (2024). What can critical perspective on whiteness do for post-racial teacher education? A review of studies from the “nice” Norwegian context. Teach. Teach. Educ. 140. April 2024:104487. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2024.104487

Gillborn, D. (2006). Citizenship education as placebo: ‘standards’, institutional racism, and education policy. Educ. Citizensh. Soc. Just. 1, 83–104. doi: 10.1177/1746197906060715

Hatchel, T., Polanin, J. R., and Espelage, D. L. (2021). Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among LGBTQ youth: Meta-analyses and a systematic review. Arch. Suicide Res. 25, 1–37. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2019.1663329

Hsieh, H. F., and Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 15, 1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

Johnson, B., and Christensen, L. (2017). Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Kubota, R. (2004). Critical multiculturalism and second language education. Critical pedagogies and language learning, 30–52. Chapter 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kumashiro, K. K. (2002). Troubling education: Queer activism and antioppressive pedagogy. New York/London: Routledge Falmer/Psychology press.

Kvale, S. (1996). InterViews: An introduction to qualitive research interviewing. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Mark, L., and Ratliffe, K. T. (2011). Cyber worlds: new playgrounds for bullying. Comput. Sch. 28, 92–116. doi: 10.1080/07380569.2011.575753

Miles, M. B., and Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Mulvey, E. P., and Cauffman, E. (2019). “The inherent limits of predicting school violence” in Clinical forensic psychology and law (New York/London: Routledge), 395–400.

Nergaard, S. E., Fandrem, H., Jahnsen, H., and Tveitereid, K. (2020). “Inclusion in multicultural classrooms in Norwegian schools: a resilience perspective” in Contextualizing immigrant and refugee resilience: Cultural and acculturation perspectives. (Springer International Publishing), 205–225.

Osler, A., and Lindquist, H. (2018). Rase og etnisitet, to begreper vi må snakke mer om. Norsk pedagogisk tidsskrift 102, 26–37. doi: 10.18261/issn.1504-2987-2018-01-04

Patton, M. Q. (2014). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage publications.

Pottie, K., Dahal, G., Georgiades, K., Premji, K., and Hassan, G. (2015). Do first generation immigrant adolescents face higher rates of bullying, violence and suicidal behaviours than do third generation and native born? J. Immigr. Minor. Health 17, 1557–1566. doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-0108-6

Ramirez, M. R., Gower, A. L., Brown, C., Nam, Y. S., and Eisenberg, M. E. (2023). How do schools respond to biased-based bullying? A qualitative study of management and prevention strategies in schools. Sch. Ment. Heal. 15, 508–518. doi: 10.1007/s12310-022-09565-8

Reijntjes, A., Kamphuis, J. H., Prinzie, P., and Telch, M. J. (2010). Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: a meta-analysis of longitudinal stdies. Child Abuse Negl. 34, 244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.009

Røthing, Å. (2007). Homonegativisme og homofobi i klasserommet. Tidsskrift for ungdomsforskning 7, 27–51.

Røthing, Å. (2019). «Ubehagets pedagogikk» – en inngang til kritisk refleksjon og inkluderende undervisning? FLEKS - Scandinavian Journal of Intercultural Theory and Practice 6, 40–57. doi: 10.7577/fleks.3309

Sjursø, I. R., Fandrem, H., Norman, J. O.’. H., and Roland, E. (2019). Teacher authority in long-lasting cases of bullying: a qualitative study from Norway and Ireland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16:1163. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16071163

Sjursø, I. R., Fandrem, H., and Roland, E. (2016). Emotional problems in traditional and cyber victimization. J. Sch. Violence 15, 114–131. doi: 10.1080/15388220.2014.996718

Svendsen, S. H. B. (2014). Learning racism in the absence of ‘race’. Eur. J. Women's Stud. 21, 9–24. doi: 10.1177/1350506813507717

The Education Act (1998). Ministry of Education and Research. Available at: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1998-07-17-61

Thomas, P. (2016). Exploring anti-Semitism in the classroom: a case study among Norwegian adolescents from minority backgrounds. J. Jew. Educ. 82, 182–207. doi: 10.1080/15244113.2016.1191255

Trysnes, I., and Skjølberg, K. H.-W. (2022). “Ekstreme ytringer i klasserommet,” in Kontroversielle, emosjonelle og sensitive tema i skolen. Eds. B. Goldsmith-Gjerløv, K. Gregers Eriksen, and K. Jore (Universitetsforlaget), 52–69.

Keywords: bias-based bullying, discomfort, pedagogy of discomfort, social justice, teachers

Citation: Thomassen WE, Moi AL, Langvik KM, Skeie G and Fandrem H (2024) Pedagogy of discomfort to prevent and intervene against bias-based bullying. Front. Educ. 9:1393018. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1393018

Edited by:

Sohni Siddiqui, Technical University of Berlin, GermanyReviewed by:

Mark Vicars, Victoria University, AustraliaNicola Hay, University of the West of Scotland, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2024 Thomassen, Moi, Langvik, Skeie and Fandrem. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wenche Elisabeth Thomassen, d2VuY2hlLmUudGhvbWFzc2VuQHVpcy5ubw==

Wenche Elisabeth Thomassen

Wenche Elisabeth Thomassen Anna L. Moi

Anna L. Moi Kjersti Merete Langvik3

Kjersti Merete Langvik3 Hildegunn Fandrem

Hildegunn Fandrem