95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 15 May 2024

Sec. Teacher Education

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1389661

This article is part of the Research Topic Navigating Trends and Challenges in Educational Professionalism View all 11 articles

Linus Mwinkaar*

Linus Mwinkaar* Jane-Frances Yirdong Lonibe

Jane-Frances Yirdong LonibeIntroduction: The needs of today’s higher education have changed and higher education does not need a one-way communication from teacher to student but rather learn to appreciate the new role of the teacher as a facilitator with mutual responsibilities toward the creation of knowledge. Heutagogy, which emphasizes learner autonomy and the creation of self-determined learners, has garnered attention as a potential solution to address the evolving needs of teacher preparation. However, empirical research on the beliefs and attitudes of Heutagogy within the teacher education context remains limited. This study aimed to fill this gap by exploring the beliefs and attitudes of lecturers and pre-service teachers of the School of Education and Life-Long Learning (SoELL) at SDD-UBIDS.

Methods: Convergent mixed method design with both quantitative and qualitative data analysis, the study collected both quantitative and qualitative data on 513 Pre-service teachers and 30 Lecturers from SoELL, SDD-UBIDS using a four-point Likert scale questionnaire and interview.

Results: The findings revealed diverse perspectives among Lecturers and Pre-service Teachers regarding Heutagogy, with varying levels of understanding, acceptance, and readiness for implementation. Lecturers expressed enthusiasm for Heutagogy’s potential to foster learner autonomy and critical thinking skills, while pre-service teachers demonstrated varying levels of readiness and comfort with self-directed learning approaches.

Discussion: Lecturers and Pre-service teachers expressed willingness to embrace a self-determined approach in which the learner reflects on what is learned and how it is learned and where the Lecturers teach the learners how to learn by themselves. The cognitive conflict and the inadequacy of pre-service teachers’ preparedness will necessitate a shift in their attitudes toward developing autonomy skills to effectively navigate the challenges of the 21st-century knowledge economy.

Education has traditionally been viewed as a pedagogic relationship between the teacher and the learner where the teacher has to impart knowledge to learners. It was always the teacher who decided what the learner needed to know, and indeed how the knowledge and skills should be taught. However, the 21st-century teaching and learning environment requires a shift from the pedagogical (teacher-centered/teacher-directed) learning approach to a more holistic teaching and learning approach. Educators need to rethink existing teaching approaches to prepare students for future careers that Industry 4.0 will change and create. How we teach and learn needs to be “re-imagined for the emerging futures of work” (Hussin, 2018; Salmon, 2019) including the alignment of technology and human teaching and learning.

Learning has become more aligned with what we do rather than what we know, making traditional methods of disciplined-based knowledge inadequate to prepare learners to live and work in communities and workplaces (Davis and Hase, 2001). Adult learners and workers who are long-life learners expect flexible and agile learning experiences that match the needs of the future (Salmon, 2019; Blaschke, 2021). Skills that are most valuable in an Industry world are those that are human-centric such as leadership, social influence, emotional intelligence, collaboration, creativity, critical thinking, flexibility, and adaptation to change (Salmon, 2019; World Economic Forum, 2020).

Recent educational reforms coupled with pandemics of the world on the educational system of Ghana suggest that educators and learners need to think beyond traditional pedagogy and andragogy and embrace a holistic professional practice of development of our students through lifelong learning and personalization of learning. Patel and Khanushiya (2018) argue that the needs of today’s higher education have changed and higher education does not need a one-way communication from the teacher to the student anymore but rather learn to appreciate the new role of the teacher as an intermediary of a double loop communication with mutual responsibilities and scopes toward the creation of knowledge.

The National Teacher Education Curriculum Framework (2018), stressed that teacher education systems face challenges in adequately preparing teachers for the current global realities brought about by the rapid pace of economic, social, technological, and environmental challenges. There is a debate on how these challenges can be overcome. Traditional approaches to teaching and learning that put subject content in ‘silos’ are being challenged by ‘modern’ approaches that enable the student teachers to create a more holistic and integrative environment, one that aids them to become more productive. The tertiary education sector is expected to produce cadres of highly qualified individuals to support economic and social development in Ghana. However, the sector faces challenges in terms of limited provision, severe inequities, and low quality. This situation has been partly blamed for the high graduate unemployment in the country (Ghana’s Education Strategic Plan, 2018–2030).

Learners are now lifelong learners, learning their profession throughout life, in chunks and when they need it (Blaschke and Hase, 2015). Considering the current trends in education, pedagogical and even andragogical educational methods are no longer fully sufficient in preparing students for thriving in the place of work requiring a more self-directed and self-determined approach in which the student reflects upon what is learned and how it is learned (Patel and Khanushiya, 2018).

Heutagogic approaches to learning are reported as facilitating entrepreneurial skills both for university students and entrepreneurs (Barton, 2012; Kapasi, 2016; Fearon et al., 2020). Kapasi (2016, p. 20) suggests that “complex and changing environments require today’s Higher Education Institutions (HEI) students to take ownership and control of their (lifelong) learning. The process of exercising ownership over the learning journey develops creative thinking, analytical, communication, and teamwork skills.

While the theoretical underpinnings of Heutagogy have been extensively discussed in the literature, there remains a paucity of empirical research examining its application and effectiveness in teacher education settings. Recent studies have highlighted the potential of Heutagogy to cultivate critical thinking, problem-solving abilities, and self-regulated learning skills among students (Stoten, 2020; Blaschke, 2021; Koul and Nayar, 2021; Lapele et al., 2021; Lynch et al., 2021). However, there is a need for an in-depth exploration of how Heutagogy is perceived, understood, and implemented by key stakeholders such as Lecturers and Pre-service teachers in teacher education.

This study seeks to address this gap in the literature by investigating the conceptions of lecturers and beliefs and readiness of pre-service teachers regarding Heutagogy as an alternative approach to teacher education in the School of Education and Life-Long Learning, SDD-UBIDS. By examining their attitudes, beliefs, and experiences, this research aims to provide valuable insights into the acceptance and implementation of Heutagogy within the teacher education landscape.

Heutagogy a concept coined by Stewart Hase of Southern Cross University and Chris Kenyon in Australia is the study of self-determined learning. As it is noted that andragogy grew out of the term pedagogy, heutagogy is an offshoot of andragogy (Patel and Khanushiya, 2018).

Heutagogy maintains the andragogical student-centered emphasis but takes it a step further by highlighting the importance of developing the skills necessary to learn on one’s own, so it is often described as the study of self-determined or self-directed learning. It is not just about learning content but also learning how to learn. It is a particularly relevant approach in institutions of higher learning such as universities, as the digital age has given enormous content and resources available to anyone with a technological device and internet access.

For example, Ashton and Newman (2006) studied a group of academics in a university program preparing new teachers. They found that “heutagogy provides an enriched teaching methodology for lifelong learning in universities in the 21st century” (p. 826) and Lock et al. (2021) recognized that the complexities of a changing world require people to be lifelong learners. This corroborates the claims from heutagogy and Education, in which both emphasize the importance of developing lifelong learners to prepare them for an ever-changing work world (World Economic Forum, 2020; Blaschke, 2021).

As per Canning (2010), the heutagogical approach can be viewed as a progression from pedagogy to andragogy to heutagogy, with students likewise progressing in maturity and autonomy.

At the Pedagogy Level: Instructors are firmly in control of the learning process, working toward motivating students to engage in learning content.

At the Andragogy Level: The instructor begins to cultivate the learner’s ability to self-direct his or her learning, allowing him or her more freedom in directing how learning occurs and providing less structure in the course design. However, the instructor is still the primary agent in the learning process, continuing to scaffold and construct the learning experience, while allowing a higher degree of learner autonomy.

At the Heutagogy Level: The learner assumes full control of his or her learning and is granted complete autonomy in deciding how he or she will learn (Canning, 2010, p. 62).

More mature students require less teacher control and course structure and can be more self-directed in their learning while less mature students require more teacher guidance and course scaffolding. With its base in andragogy, heutagogy further extends the andragogical approach and can be understood as a continuum of andragogy.

Blaschke and Hase (2015) explained the overview of attributes that help demonstrate ways in which heutagogy builds upon and extends andragogy has been viewed as a continuum of andragogy as given below.

Higher education has a particular resemblance to the heutagogical approach due to higher education’s inherent characteristics of requiring and promoting student autonomy, its traditional focus on adult students, and its evolutionary and symbiotic relationship with technology. Because of this resemblance higher education is in a unique position to provide a sustainable environment for studying and researching this teaching and learning method and for assessing and evaluating the theory’s appropriateness as a theory of higher education.

Varenhorst and Marsick (2018) proposed a pedagogic learning design framework for teacher education, aiming to empower teachers as self-directed learners actively shaping their professional development journeys. Overall, Varenhorst and Marsick’s framework provides a valuable foundation for designing heutagogic teacher education programs that empower teachers, promote knowledge sharing, and cultivate lifelong learners who can thrive in dynamic educational environments.

In the exploration of heutagogy in teacher education, Mantovani and Jarvis (2023) advocate for venturing beyond its standalone application and fostering its integration with other pedagogical approaches. This broadened perspective promises a more holistic teacher education experience that leverages the strengths of various methods to address diverse learner needs and educational contexts. Mantovani and Jarvis (2023) call for further research and experimentation to explore effective models for integrating heutagogy with other pedagogical approaches. This requires collaboration between researchers, teacher educators, and practitioners to design, implement, and evaluate innovative teacher education programs that leverage the strengths of diverse methodologies and empower teachers to become self-directed, lifelong learners who can thrive in the complexities of contemporary education. By embracing an integrative approach, teacher education can move beyond rigid, one-size-fits-all methods and cultivate well-rounded, adaptable educators equipped to navigate the ever-evolving landscape of teaching and learning.

While heutagogic approaches in teacher education hold immense potential for empowering self-directed learning and fostering adaptability, Fisher (2022) highlights the crucial need to consider cultural contexts and individual learning styles for their successful implementation. Fisher (2022) emphasizes the dynamic nature of cultural contexts and individual learning styles. Heutagogic programs need to be continuously adapted and refined to remain culturally relevant and cater to the diverse needs of educators. This requires ongoing reflection, evaluation, and collaboration between program designers, facilitators, and participating teachers to ensure successful and equitable implementation of heutagogic approaches in teacher education.

By embracing cultural sensitivity and individual learning styles, heutagogic programs can unlock the full potential of self-directed learning, empowering teachers to become culturally responsive and adaptable educators who can effectively cater to the diverse needs of their students in an increasingly interconnected world.

While promising potential surrounds heutagogic approaches in teacher education, Korthagen et al. (2021) highlight the critical need for more research on their long-term impact on teacher practice and student learning outcomes. By addressing the call for further research, we can unlock the true potential of heutagogic approaches in teacher education. Understanding their long-term impact will guide program development, refine implementation strategies, and ultimately inform decisions about scaling up heutagogy to empower future generations of educators and cultivate self-directed, lifelong learners. This exploration highlights the multifaceted nature of evaluating the effectiveness of educational interventions. It is crucial to move beyond short-term measures and delve into the lasting influence of innovative approaches like heutagogy to ensure we are truly preparing teachers and students for success in the complexities of the 21st century.

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) is a psychological framework developed by Deci and Ryan in 1985 that focuses on intrinsic motivation and the factors that drive human behavior by Ryan and Deci (1985). Self-Determination Theory (SDT) provides valuable insights into understanding the underlying motivations and psychological needs of individuals, which are pertinent to the implementation of Heutagogy in teacher education. SDT posits that individuals have three basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. When these needs are satisfied, individuals are more intrinsically motivated and likely to engage in self-directed learning.

SDT emphasizes the importance of autonomy, which refers to the need to feel in control of one’s actions and decisions. Heutagogy, as discussed in the article, is an educational approach that emphasizes self-directed learning. It empowers learners to take control of their learning processes, set their own goals, and choose their learning strategies. In the context of teacher education, embracing heutagogy means giving pre-service teachers autonomy in their learning journey, allowing them to explore topics of interest, and encouraging them to take ownership of their professional development.

SDT suggests that individuals have an inherent drive to develop their skills and capabilities. Heutagogical approaches can support this need for competence by providing opportunities for pre-service teachers to engage in meaningful learning experiences that enhance their knowledge, skills, and understanding of teaching practices. By actively participating in their learning process, pre-service teachers can gain confidence in their abilities and develop the competencies necessary for effective teaching.

The need for relatedness refers to the desire to feel connected to others and to have meaningful relationships. In the context of teacher education, heutagogy can foster a sense of community and collaboration among pre-service teachers and lecturers. By encouraging peer learning, group discussions, and collaborative projects, heutagogical approaches can create opportunities for meaningful interactions and supportive relationships within the learning environment.

Overall, the principles of Self-Determination Theory provide a valuable framework for understanding the potential benefits of heutagogy in teacher education. By promoting autonomy, competence, and relatedness, heutagogical approaches can empower pre-service teachers to become lifelong learners who are capable of adapting to the demands of the teaching profession and making meaningful contributions to education.

The design for the study was the Convergent mixed method design. Creswell and Creswell (2023) indicated that convergent mixed methods design is the design in which the researcher converges or merges quantitative and qualitative data to provide a comprehensive analysis of the research problem. In this design, the investigator typically collects both forms of data at roughly the same time and then integrates the information into the interpretation of the overall results. The first author adopted a census approach to select a total of 543 participants, comprising 513 pre-service teacher students and 30 lecturers, respectively. Ten participants from each group were also interviewed by the second author for qualitative data.

Quantitative data was collected using a four-point Likert scale questionnaire with both closed-ended and open-ended questions which was developed by the researcher. The first part of the questionnaire was a five-point Likert scale which involved “5 = Strongly Agree, 4 = Agree, 3 = Neutral, 2 = Disagree, and 1 = Strongly. Qualitative interviews lasted 20 min on average per participant involving open-ended questions about individuals’ beliefs and perceptions about the principles of heutagogy as a training approach.

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the ethics committee of the School of Education and life-long Learning. Participant’s consent was also obtained as well as confidentiality and anonymity assured that all the information obtained would only be used for the stated purposes and no other person had access to them Pseudonyms are used where necessary and other identifiable features concealed to protect participants.

Quantitative data collected through the questionnaires were analyzed through. Descriptive statistics in the form of percentages, mean, and standard deviation with the help of Statistical Product for Service Solution (SPSS) software version 22. Directed content analysis was used to process the qualitative interviews.

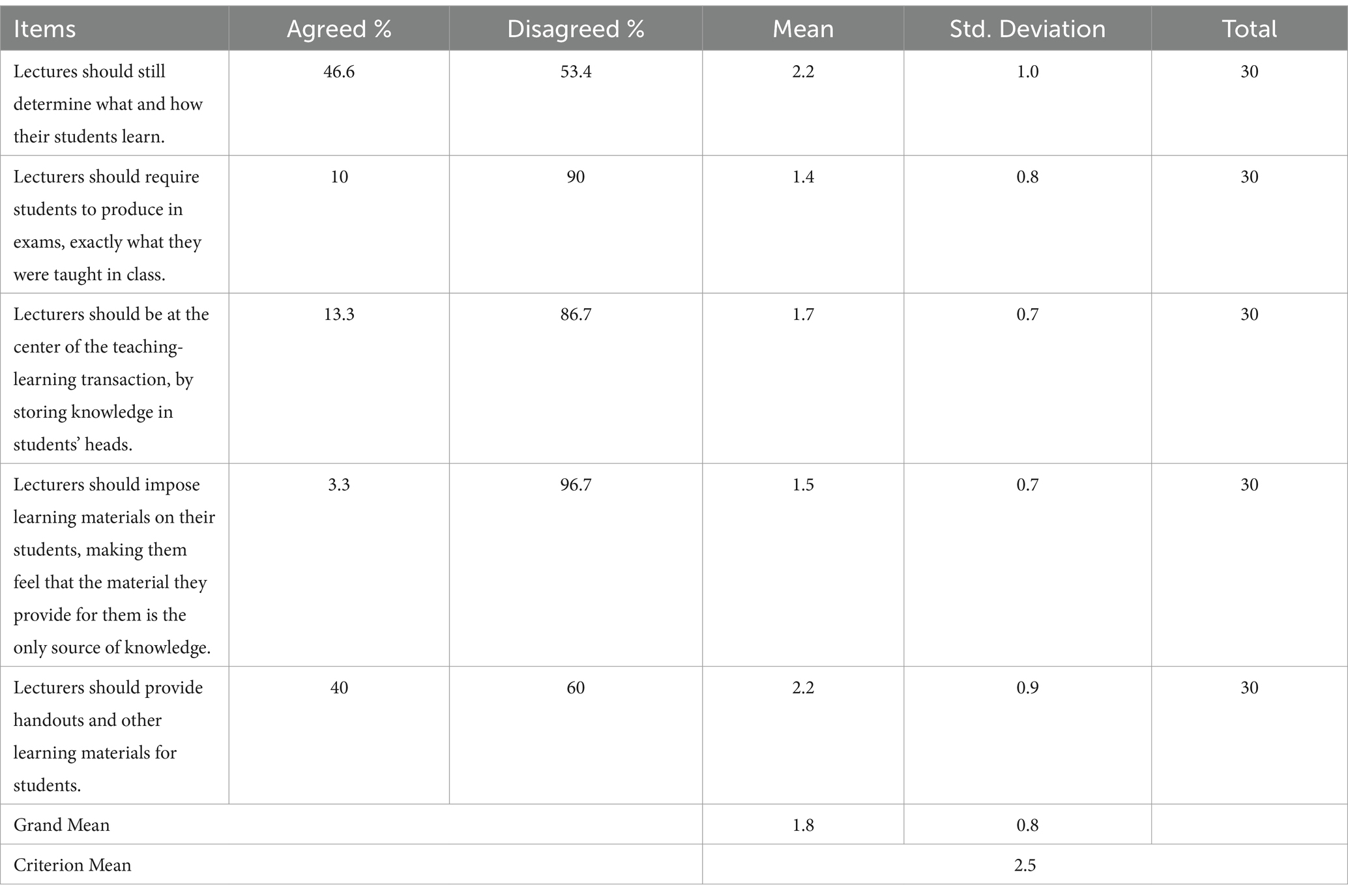

As illustrated in Table 1, Findings indicated that lecturers demonstrated negative responses toward the notion of being more active in directing teaching and learning experiences. There was a prevailing sentiment among lecturers discouraging the idea of taking center stage and exerting control over the learning experience in higher education. Instead, lecturers expressed a belief that they should refrain from imposing learning experiences and materials on students, thereby avoiding the creation of an impression that lectures are the sole source of knowledge and learning experiences. Additionally, there was a consensus among lecturers that pre-service teachers should not solely rely on handouts provided by lecturers as the primary source of knowledge. Rather, lecturers should focus on creating a conducive learning environment and serve as facilitators, guiding and correcting misconceptions that may arise during the learning process of learners.

Table 1. Lecturers’ viewpoints regarding their role in determining the teaching and learning experiences.

“I think that lecturers should only create an enabling environment for learning to take place instead of inducing it, besides each individual has his or her way of learning how then can a single person take all these onto himself, the environment has an influence on the performance of learning, so lecturers should, in my opinion, play that guiding role by being enablers of a conducive and smooth environment for learning to strife” (Lecturer interviewee 2. February 2024).

The noticeable shift observed in lecturers’ perspectives, moving away from the traditional approach to teaching and learning toward a new paradigm where students are empowered to determine their learning paths, resonates deeply with Self-Determination Theory (Ryan and Deci, 1985). This theory posits that individuals have innate psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, which are essential for optimal motivation and well-being. By embracing student autonomy and allowing them to take control of their learning, educators fulfill students’ need for autonomy, fostering intrinsic motivation and engagement in the learning process.

The views expressed by Patel and Khanushiya (2018), suggesting minimal changes within higher education environments to accommodate this shift, echo the principles of Self-Determination Theory. Minimal changes imply a recognition of the importance of providing opportunities for autonomy within existing educational structures. In this evolving landscape, higher education teaching methods increasingly emphasize self-directed learning, with lecturers assuming the role of guides rather than sole purveyors of knowledge. By facilitating students’ autonomy in determining their learning paths, educators support their intrinsic motivation, and enhance their overall learning experience, aligning with the principles of Self-Determination Theory.

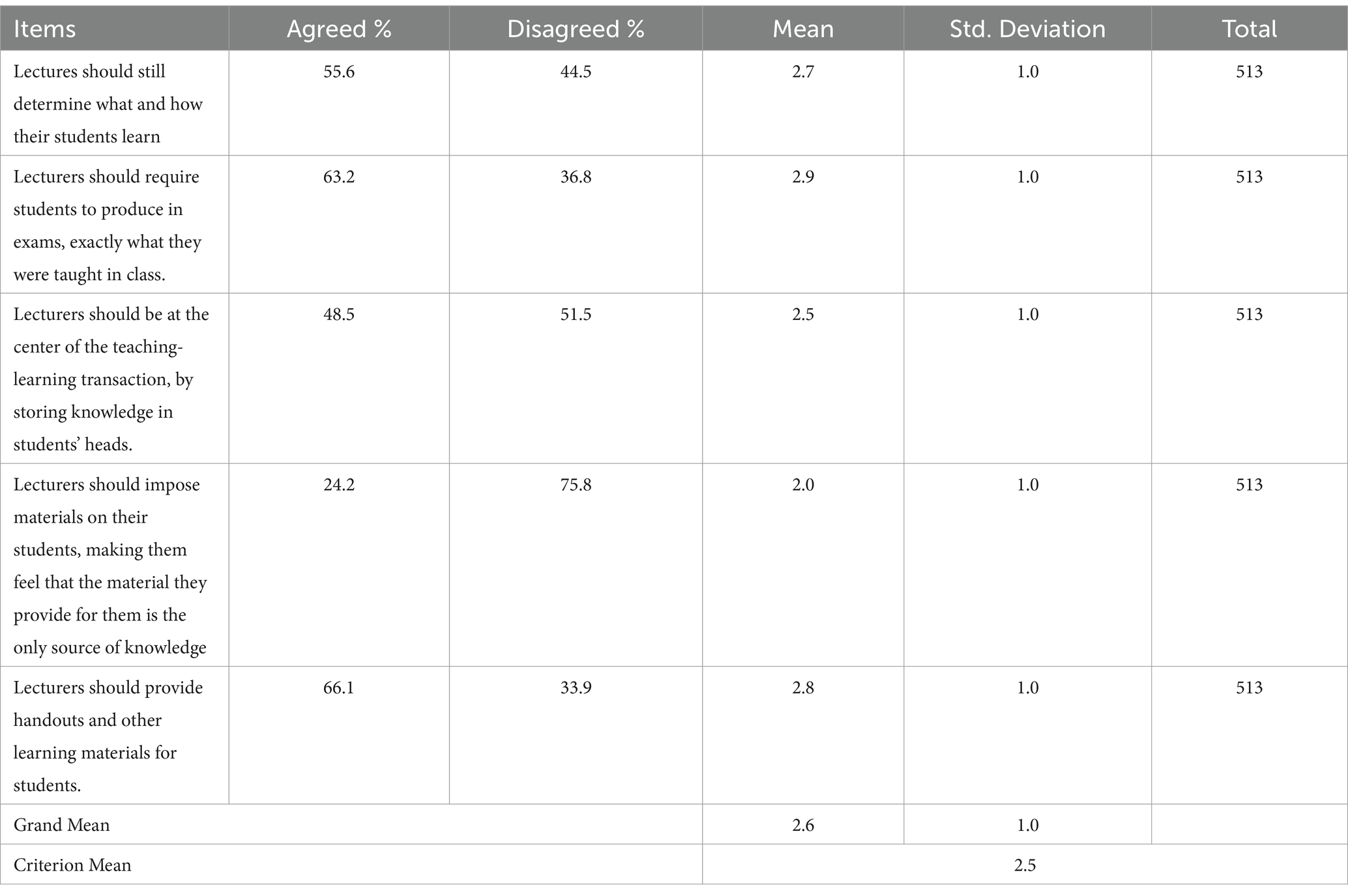

As illustrated in Table 2, findings revealed that pre-service teachers exhibited positive responses toward the idea of lecturers being more active and directive in shaping the teaching and learning experiences. They expressed a preference for lecturers taking center stage and exerting control over the learning process in higher education. SDT emphasizes the importance of autonomy-supportive contexts. When learners feel autonomous and have some control over their learning, intrinsic motivation is fostered. Pre-service teachers’ reliance on handouts from lecturers suggests a desire for external guidance, which may stem from a lack of perceived autonomy in determining their learning paths. Pre-service teachers conveyed a belief that lecturers, as the “experts,” should determine both the content and methodology of learning, viewing them as authorities who possess superior knowledge and understanding. Although SDT acknowledges that individuals often look to authorities (such as lecturers) for guidance(cite). Pre-service teachers viewing lecturers as experts who possess superior knowledge does not reflect this tendency. Indeed, striking a balance between authority and autonomy is essential for fostering intrinsic motivation. Additionally, the research indicated that pre-service teachers demonstrated limited confidence and self-efficacy in autonomously determining their learning paths. They expressed a preference for receiving handouts from lecturers, suggesting a reliance on external materials provided by instructors rather than engaging in self-directed learning. Pre-service teachers’ limited confidence and self-efficacy in autonomously determining their learning paths, coupled with their preference for receiving handouts from lecturers, underscore a proclivity toward external regulation and a reluctance to engage in self-directed learning. This reluctance to embrace autonomy in learning may impede the development of intrinsic motivation and hinder the cultivation of self-determined learners, as emphasized by Self-Determination Theory. This was corroborated by some students interviewed:

Table 2. Pre-service teachers’ perspectives on lecturers determining the teaching and learning experiences.

Lecturers play a key role in what and how the student should study. It is the lecturers who provide students with the course outline for the trimester, the course outline will then create the boundaries within which students study the course. Also, without the lecturers' guidance on how and what students should study, students will learn haphazardly. Each student will study from where he or she thinks is suitable. Again, to the mode of assessment, how will the lecturer assess students at the end of the day? Without the lecturer determining what students should learn, setting exam questions becomes a tag of war as the lecturers will end up favoring others to the detriment of others. I will conclude by stating emphatically that lecturers are at every liberty to determine what students should learn (Student Interviewee 1. February 2024).

I believe that lecturers have a better understanding of the requirements of employees as they are often in constant research. From my observation, our courses are always designed with knowledge of what employers want. Sometimes students don't even know what courses they're to do before they report. It'll be impractical to allow them to make any input (Student interviewee 4. February 2024).

Pre-service teachers, however, expressed opposition to the notion of lecturers imposing learning materials on them or relying solely on these materials as the primary source of knowledge. While they acknowledged their comfort in receiving learning materials from lecturers, they disapproved of the idea of these materials being the sole source of knowledge for their learning. SDT recognizes the role of self-efficacy in motivation. Pre-service teachers demonstrating limited confidence in autonomously determining their learning paths may benefit from autonomy-supportive environments that build their self-efficacy.

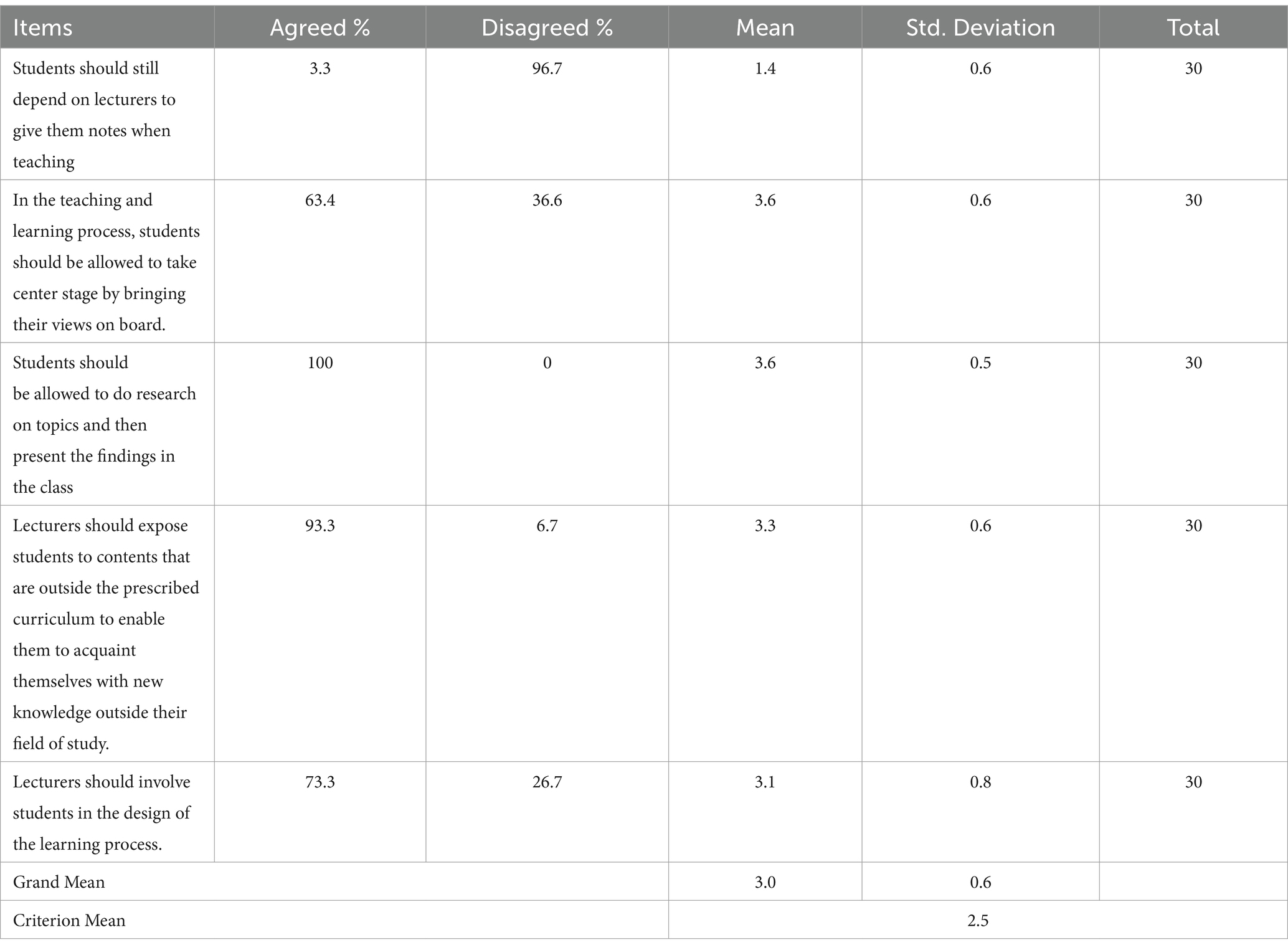

Findings from Table 3, regarding lecturers’ perceptions of pre-service teachers’ active participation in teaching and learning experiences revealed a notable trend. Mentors consistently scored a grand mean score of 3.0, exceeding the criterion mean of 2.5, with a corresponding standard deviation of 0.6. This indicates a positive response among lecturers, suggesting that they endorse the idea of students being more active and self-determined in their teaching and learning experiences.

Table 3. Lecturers’ viewpoints regarding the role of pre-service teachers in determining the teaching and learning experiences.

At the university level, students are mature and for this reason, lecturers should not dictate to students what they should learn but rather, guide students on what and how to learn (Lecturer interviewee 4. February 2024).

When students are allowed to do discovery learning, it will help them build the spirit of teamwork and good interpersonal relationships with the people in their environment” (Lecturer interviewee 1. February 2024).

Findings indicated that lecturers hold the belief that pre-service teachers at higher levels of education, such as universities, possess a level of maturity that enables them to take charge of their learning process. Consequently, lecturers advocated for an approach where they refrain from adopting a one-size-fits-all method of teaching. Instead, they emphasized the importance of allowing students to actively discover and determine their learning paths, albeit under the guidance of lecturers.

By recognizing the capacity of pre-service teachers to exercise autonomy in their learning, lecturers implicitly acknowledge and support the fulfillment of their need for autonomy, thereby fostering intrinsic motivation and engagement in the educational endeavor.

The advocacy by lecturers for an approach that eschews a rigid, one-size-fits-all method of teaching in favor of one that prioritizes student agency in discovering and determining their learning paths further underscores a commitment to promoting autonomy within the educational context. This approach resonates with the principle of autonomy within Self-Determination Theory, which emphasizes the importance of individuals’ ability to make choices and exert control over their actions. By affording students the freedom to actively participate in knowledge acquisition and skill development, albeit within the framework of guidance provided by lecturers, educators facilitate the fulfillment of students’ intrinsic psychological needs, thereby enhancing their motivation and fostering a deeper engagement with the learning process.

In essence, the stance taken by lecturers reflects a recognition of the pivotal role of autonomy in promoting optimal motivation and learning outcomes, as espoused by Self-Determination Theory. By embracing an approach that empowers students to actively shape their educational experiences, lecturers not only support the development of self-determined learners but also contribute to the cultivation of a dynamic and enriching educational environment characterized by intrinsic motivation and meaningful engagement. Patel and Khanushiya (2018), further argue that implementing a self-determined learning environment necessitates a shift in teaching approach. Specifically, educators must prioritize and foster student self-direction in the learning process. Whether lecturers’ perspectives about learners’ self-determination reflect the actual opportunities granted to students for self-directed learning is yet to be determined, but suffice to say that educators’ positive orientation toward SDT is a welcome idea.

Moreover, the findings suggested that lecturers recognized the diversity among pre-service teachers and the need to accommodate varied learning preferences and styles. By adopting a flexible and student-centered approach, lecturers aim to empower pre-service teachers to engage meaningfully with the course material and take ownership of their learning journey. This approach not only promotes deeper understanding and retention of content but also cultivates essential skills such as critical thinking, problem-solving, and self-regulation.

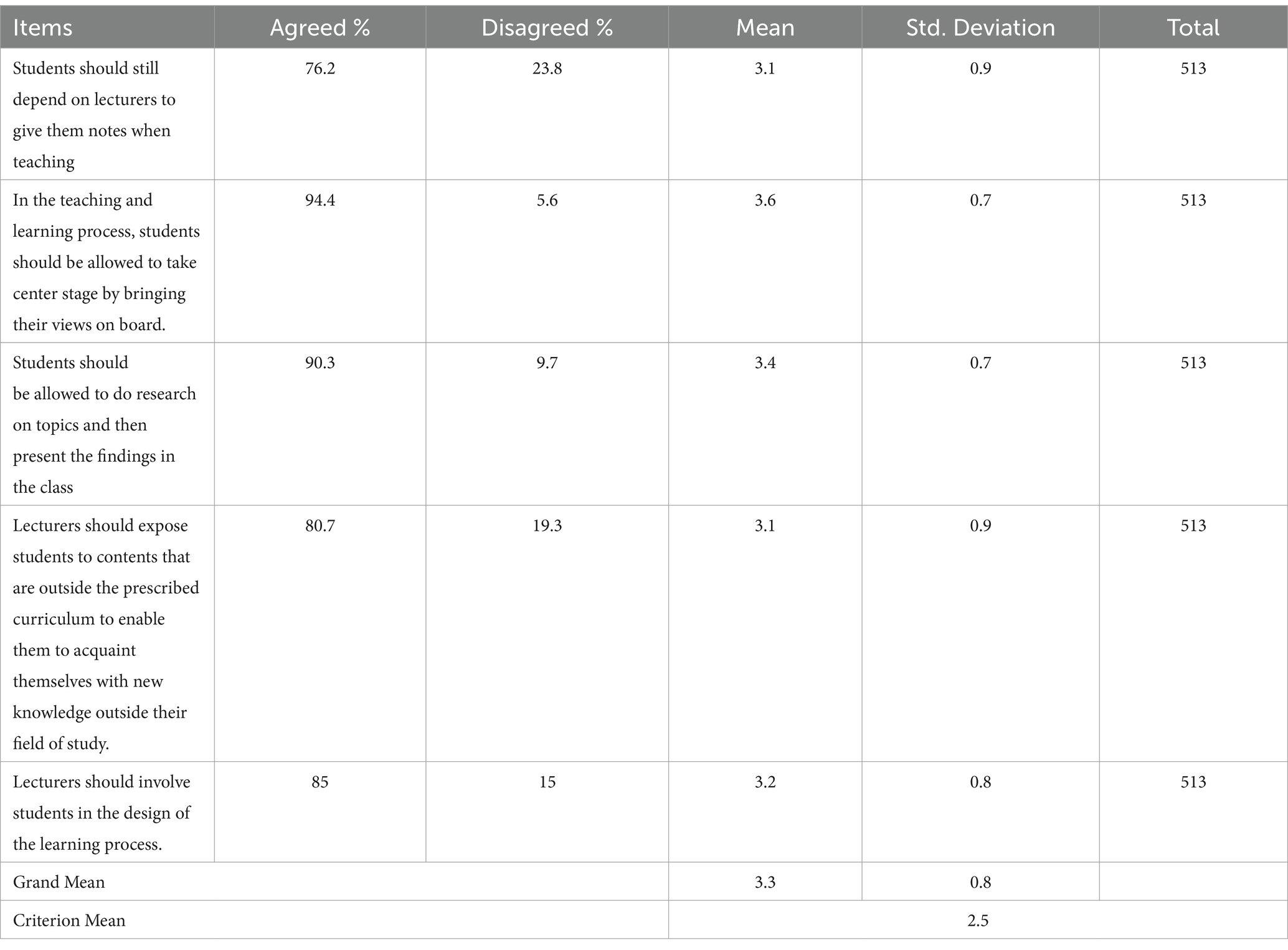

Findings from Table 4, which presented students’ responses regarding their active participation in teaching and learning experiences, revealed a significant trend. The results showed a grand mean score of 3.3, accompanied by a corresponding standard deviation of 0.8. This indicates a positive response among students, suggesting a strong inclination toward being more active and self-determined in their teaching and learning experiences.

Table 4. Pre-service teachers’ viewpoints regarding their role in determining the teaching and learning experiences.

Qualitative data of students’ expressions corresponds with this response as some students had this to say.

Students at that stage need to do more research on their course of study. When lectures spoon-feed them with everything, the spirit of researching for information will die off in them (Student Interviewee 5, February 2024).

No, because at this level, students know what they want and how to learn. Lecturers should rather guide students in learning by providing them with the necessary conditions for learning (Student Interviewee 7, February 2024).

Findings from Table 4 showed that pre-service teachers exhibited a strong belief in their ability to determine what and how they learn, particularly when provided with appropriate guidance from their lecturers. By expressing confidence in their ability to self-direct their learning, pre-service teachers exhibit a sense of autonomy, fulfilling one of their fundamental psychological needs as posited by SDT. They perceived self-determined learning as an opportunity to enhance their research skills and other essential competencies. This reflects the pursuit of competence, another intrinsic need highlighted in Self-Determination Theory, which indicates that individuals are motivated to engage in activities that allow them to experience a sense of mastery and efficacy. By viewing self-determined learning as a means to develop and refine their skills, students demonstrate a proactive approach to fulfilling their need for competence, thereby enhancing their intrinsic motivation and engagement in the learning process.

Moreover, students expressed a desire to expand their learning beyond the confines of the prescribed curriculum, recognizing the value of exposure to broader content within their field of study. This sentiment aligns with arguments put forth by Blaschke (2021) and the World Economic Forum (2020), emphasizing the importance of learner agency and student-driven learning in education and heutagogy.

Furthermore, the research revealed that students view self-determined learning as a pathway to lifelong learning, where they have the autonomy to decide how and when to learn. This assertion underscores the significance of providing students with opportunities to exercise their voice and choice in the learning process. Additionally, insights from Glassner and Back (2019) shed light on the transformative nature of self-determined learning experiences. Students not only gain a deeper understanding of themselves as learners but also develop essential skills to navigate the challenges inherent in self-directed learning. Moreover, they leverage the benefits of collaborative and cooperative learning in small groups to enhance their learning outcomes.

The findings gathered from this study provide compelling evidence of the collective disposition of both lecturers and pre-service teachers toward endorsing a self-determined approach to learning. This approach encompasses a paradigm in which learners are encouraged to actively participate in the processes of content selection, methodological exploration, and environmental adaptation. Within the discourse surrounding self-determined learning, the concept of heutagogy emerges as a salient theoretical framework. Heutagogy is recognized as an instrumental pedagogical framework capable of nurturing the cultivation of vital competencies requisite for autonomous learning.

Heutagogy, often juxtaposed with traditional pedagogical models, emphasizes learner-centeredness and places a premium on the development of metacognitive skills, critical thinking, and self-regulation. Scholars such as Hase and and Kenyon (2003) and Ryan and Deci (1985), have championed heutagogical principles as essential for fostering the capacity for autonomous learning, positing that learners, under the auspices of heutagogy, become adept at navigating complex learning environments and assuming ownership of their educational trajectories. Patel and Khanushiya (2018) indicate that heutagogy is increasingly recognized as a practical solution in professional higher education institutions, such as nursing, engineering, and education. Educators in these fields have acknowledged the importance of incorporating Heutagogy into their teaching practices to address the critical challenges faced by students in real-world work settings.

The empirical findings of the present study resonate with extant literature, as they underscore the perceived value attributed to heutagogy by both educators and learners. The mutual acknowledgment of heutagogy’s efficacy in fostering essential competencies for autonomous learning suggests a convergence of perspectives toward the cultivation of learner agency and self-directedness. By engaging in reflective practices and exercising choice in content selection and methodological approaches, learners not only enhance their academic proficiency but also fortify their capacity for self-directed inquiry and lifelong learning, an outcome congruent with the foundational tenets of Self-Determination Theory (Ryan and Deci, 1985).

Moreover, the study illuminates the imperative of transcending traditional conceptions of learning, which prioritize the mere acquisition of content knowledge, to embrace a more holistic view that emphasizes the cultivation of independent learning capabilities. This shift underscores a departure from passive reception of knowledge toward an active engagement with the learning process, an evolution epitomizing the principles of autonomy and competence posited within Self-Determination Theory.

This study’s emphasis on a self-determined approach using Heutagogy aligns with SDT and contributes to the understanding of effective learning practices in teacher education. By fostering autonomy, competence, and potential relatedness through a supportive learning community, educators can empower pre-service teachers to become lifelong, self-directed learners. However, the study also noted a cognitive disagreement among students regarding who determines and directs their learning. While expressing a desire for increased autonomy, self-determination, and independence in their learning, students also responded positively to lecturers taking a central role in directing their learning.

This multifaceted response underscores a potential incongruity between students’ professed desires for autonomy and their readiness to fully embrace the responsibilities inherent in self-determined learning paradigms.

This cognitive disagreement aligns with the concept of autonomy support within Self-Determination Theory (SDT) as described by Ryan and Deci (1985). While students desire autonomy (increased self-determination and independence), their positive response to a lecturer-centered approach suggests a potential lack of experience or confidence in fully self-directed learning. This could be due to a history of teacher-directed learning environments, leading to a state of learned helplessness.

Research by Deci and Ryan (2000) suggests that autonomy support fosters intrinsic motivation when it allows learners to feel a sense of choice, competence, and relatedness. In the context of this study, creating a supportive Heutagogical environment involves not only offering opportunities for self-directed learning but also scaffolding student development toward greater autonomy. The World Economic Forum (2020) calls for a shift from process-based learning, characterized by teachers imparting direct knowledge through demonstrations of processes and formulas, to a problem-based approach. This approach involves assigning collaborative projects to preservice teachers and providing opportunities to explore multiple solutions to real-world problems.

The “cognitive disagreement” can be addressed by incorporating strategies that promote metacognition; awareness, and understanding of one’s learning processes. Works like (Yuen and Fleming, 2018) emphasize the importance of metacognitive skills in Heutagogy, allowing learners to take ownership of their learning journey. By explicitly teaching metacognitive skills, lecturers can empower students to navigate the transition from teacher-directed to self-directed learning.

Furthermore, fostering a growth mindset, as explored by Dweck (2006), can be beneficial. By encouraging students to view challenges as opportunities for learning and growth, lecturers can cultivate a learning environment where students feel confident in taking ownership of their learning experiences.

In light of the aforementioned considerations, the cognitive dissonance observed among students underscores the need for a nuanced approach to fostering self-determined learning. By recognizing and addressing the developmental gaps in students’ readiness for autonomy, educators can facilitate a more seamless transition toward self-directed learning paradigms, thereby aligning pedagogical practices with the principles of Self-Determination Theory and promoting optimal motivation and engagement within educational contexts.

Despite the positive response from lecturers toward embracing student-driven learning and assuming a facilitator role, there remains resistance to the implementation of Heutagogy-based teaching and learning approaches. Therefore, it is imperative for lecturers to actively promote the adoption of Heutagogy, even amidst perceived threats to their traditional roles and authority in the classroom.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The research was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

LM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft. J-FL: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review and editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ashton, J., and Newman, L. (2006). An unfinished symphony: 21st century teacher education using knowledge creating heutagogies. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 37, 825–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2006.00662.x

Barton, M. (2012). Developing core competencies of SME managers using heutagogy principles. Proc. Int. Conf. Manag. Hum. Resour. 20, 283–288. doi: 10.18515/dBEM.M2012.n01.ch18

Blaschke, L. M. (2021). The dynamic mix of heutagogy and technology: preparing learners for lifelong learning. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 52, 1629–1645. doi: 10.1111/bjet.13105

Blaschke, L. M., and Hase, S. (2015). “Heutagogy: a holistic framework for creating 21st century self-determined learners” in The future of ubiquitous learning: Learning designs for emerging pedagogies. eds. M. M. Kinshuk and B. Gros (Heidelberg: Springer Verlag).

Canning, N. (2010). Playing with heutagogy: exploring strategies to empower mature learners in higher education. J. Furth. High. Educ. 34, 59–71. doi: 10.1080/03098770903477102

Creswell, W. J., and Creswell, D. J. (2023). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 5th Edn. Los Angeles: SAGE.

Davis, L., and Hase, S.. (2001). The river of learning in the workplace. Research to reality: Putting VET research to work. Proceedings of the Australian Vocational Education and Training Research Association (AVETRA) Conference.

Fearon, C., van Vuuren, W., McLaughlin, H., and Nachmias, S. (2020). Graduate employability, skills development, and the UK’s universities business challenge competition: a self-determined learning perspective. Stud. High. Educ. 45, 1280–1297.

Fisher, C. (2022). Reimagining teacher education: towards a heutagogic approach for culturally responsive and adaptable educators. J. Curric. Stud. 54, 739–762.

Glassner, A., and Back, S. (2019). Heutagogy (self-determined learning): new approach to student learning in teacher education. J. Plus Educ. 24, 40–44.

Hase, S., and Kenyon, C. (2003). Self-determined learning: Heutagogy in action. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Hussin, A. A. (2018). Education 4.0 made simple: ideas for teaching. Int. J. Educ. Liter. Stud. 6:92. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.6n.3p.92

Kapasi, I. (2016). “Autonomous student learning: the value of the Finnish approach” in Showcasing new approaches to higher education: Innovations in learning and teaching. ed. C. A. Penman (Edinburgh: Merchiston Publishing).

Koul, S., and Nayar, B. (2021). The holistic learning educational ecosystem: a classroom 4.0 perspective. High. Educ. Q. 75, 98–112. doi: 10.1111/hequ.12271

Lapele, F., Kartowagiran, B., Haryanto, H., and Prihono, W. E. (2021). Heutagogy: the Most holistic approach utilizing technology in learning. Adv. Soc. Sci. Educ. Human. Res. 640, 154–159.

Lock, J., Lakhal, S., Cleveland-Innes, M., Arancibia, P., Dell, D., and De Silva, N. (2021). Creating technology-enabled lifelong learning: a heutagogical approach. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 52, 1646–1662. doi: 10.1111/bjet.13122

Lynch, M., Sage, T., Hitchcock, I. L., and Sage, M. (2021). A heutagogical approach for the assessment of internet communication technology (ICT) assignments in higher education. Int. J. Educ. Technol. 18:55. doi: 10.1186/s41239-021-00290-x

Mantovani, G., and Jarvis, P. (2023). Beyond heutagogy: integrating heutagogic principles with other pedagogical approaches in teacher education. J. Profess. Teach. Educ. 38, 246–265.

National Teacher Education Curriculum Framework (2018). The essential elements of initial teacher education. Accra: Ministry of Education, Ghana.

Patel, J. V. (2018). Paradigm shift-pedagogy to andragogy to Heutagogy in higher education. Essentials of Techno-Pedagogy, 282.

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Springer Science and Business Media.

Salmon, G. (2019). May the fourth be with you: creating education 4.0. J. Learn. Dev. 6, 95–115. doi: 10.56059/jl4d.v6i2.352

Stoten, W. D. (2020). Navigating heutagogic learning: mapping the learning journey in management education through the OEPA model. J. Res. Innov. Teach. Learn. 10, 83–97.

Varenhorst, B., and Marsick, V. J. (2018). A pedagogic learning design framework for teacher education: empowering teachers as self-directed learners. J. Teach. Educ. 69, 239–252.

World Economic Forum (2020). Schools of the future: defining new models of education for the fourth industrial revolution. World Econ. Forum, 1–33.

Keywords: pedagogies, andragogy, Heutagogy teaching, learning, teacher education

Citation: Mwinkaar L and Lonibe J-FY (2024) Heutagogy as an alternative in teacher education: conceptions of lecturers and pre-service teachers of school of education and life-long learning, SDD-UBIDS. Front. Educ. 9:1389661. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1389661

Received: 21 February 2024; Accepted: 30 April 2024;

Published: 15 May 2024.

Edited by:

Arumugam Raman, University of Northern Malaysia, MalaysiaReviewed by:

Asma Shahid Kazi, Lahore College for Women University, PakistanCopyright © 2024 Mwinkaar and Lonibe. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Linus Mwinkaar, bGludXNtd2lua2FhcjkxQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.