- 1Faculty of Law, Department of Public Law, University of Applied Science Private University, Amman, Jordan

- 2Language Center, University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan

Introduction: The study addresses the phenomenon of referential gaps between Arabic and English, highlighting the distinct referential behaviors each language employs during communication. These differences pose challenges to both language recipients and educators, creating obstacles for Arabic and English teachers and learners alike. Understanding these gaps is crucial for improving language learning and teaching processes.

Methods: The study investigates referential gaps by analyzing their manifestations across four linguistic levels: phonetic, lexical, morphological, and syntactic systems in both Arabic and English.

Results: The findings demonstrate that the distinct referential behaviors in Arabic and English differ significantly across the analyzed linguistic levels. These differences contribute to the challenges faced by language learners and educators.

Discussion: The study underscores the importance of understanding referential gaps to address the challenges they present. By highlighting these differences, it provides insights into improving teaching strategies and fostering better communication between Arabic and English speakers.

1 Introduction

The current study is considered significant because it highlights the linguistic gaps between Arabic and English as these gaps form a major problem that makes it difficult for both teachers and learners to spontaneously handle linguistic obscurity since it is a major obstacle to the educational process. When the teacher or the learner does not understand how language works, s/he applies the logic of his/her first language to the target language they teach or learn, and then they face problems and feel disappointed. This is a very serious and important subject as it creates opportunities for improving the methods of teaching Arabic to non-native speakers and helps in developing rich scientific material and an accurate method to facilitate the educational process, identify educational obstacles and the teaching problems that are resulted from some behaviors of learned languages, and then face them in the most appropriate way that brings them closer to understanding. Moreover, the Arab Library’s need for practical studies in this crucial field motivated conducting this research. This study also aims to collect a good number of words, expressions, and methods that can be labeled as referential gaps in order to draw the attention of Arabic or English teachers and learners to them, so they pay more attention to how such words and expressions are taught to second language learners. This will also help Arabic and English teachers and learners to pay attention to the different systems of each language (vocabulary, expressions, and methods) so that it is easier for them to deal with them and take into account the logic of each language. It also aims to analyze each language’s vocabulary and classify it according to what the analysis conducted leads to.

2 Literature review

In this field, Al-Dilaimy (1998) conducted a study that examined the concept of reference in English and Arabic, focusing on the use of definite and indefinite expressions to identify entities in discourse. Reference, as a semantic relationship between an expression and its referent, was identified as critical for recognizing entities in both written and spoken contexts. Traditionally, linguistic research had focused on definite references, as they provided more explicit information about the referent. In contrast, indefinite references, which played a less prominent role in identification, had received comparatively less attention. Findings indicated that Arabic more frequently used definite articles for both specific and generic references, whereas English often employed pronouns, pro-forms, and ellipses. Additionally, English used both definite and indefinite expressions for generic references, while Arabic relied primarily on definite expressions. The study also involved a contrastive analysis with 80 Arabic-speaking undergraduate students at Al-Anbar University. It investigated how these students handled English referential expressions in written performance. Results indicated that students struggled with distinguishing between definite and indefinite references in English, often misusing articles without regard to semantic or syntactic restrictions. Despite extended study of English, students demonstrated a low accuracy rate in using definite and indefinite articles, particularly for generic and specific references.

Another study was conducted by Flege and Port (1981), which compared the phonetic implementation of stop voicing contrasts in Arabic and English, produced by Saudi speakers of Arabic and by both Saudi and American speakers in English. The study analyzed temporal acoustic correlates of stop voicing, such as Voice Onset Time (VOT), stop closure duration, and vowel duration, and found that English stops produced by Saudi speakers exhibited phonetic patterns similar to Arabic stops. This transfer of phonetic characteristics from Arabic to English suggests an influence of the native language on second language production. Despite this phonetic interference, American listeners generally had little difficulty identifying the English stops produced by Saudi speakers, with the notable exception of the phoneme /p/. Because Arabic lacks this phoneme, it was often produced by Saudi speakers with glottal pulsing during the stop closure interval, a pattern that deviates from native English production norms. The study indicates that while Saudi speakers appeared to understand the phonological contrast between /p/ and /b/—similar to other stop contrasts in English such as /t-d/ and /k-g/—they faced challenges in fully mastering the articulatory control required to produce /p/ accurately in all phonetic dimensions.

For an accurate and productive analysis, our study adopted the contrastive approach because this approach provides tools that help identify the main concept of these gaps and the problems they impose and bring them closer to the mind of teachers and learners by comparing both languages in relation to the stylistic features. This would make the educational process easier and less adventurous in the Arabic and English languages. To this end, the study is divided into two main sections: a theoretical section that defines the concept of linguistic gaps and shows the importance of revealing it in applied studies in the field of teaching Arabic and English to non-native speakers, and an applied section that traces such gaps in both languages at all lexical, phonetic, morphological, and structural levels.

3 Methodology

To achieve an accurate and comprehensive analysis, this study used a contrastive analysis approach to systematically compare the stylistic features of Arabic and English. This approach provided a structured framework for identifying linguistic gaps and stylistic challenges that may affect language learning and teaching in both languages.

3.1 Data collection methods

The study began by identifying specific stylistic features in Arabic and English that are relevant to language instruction, including syntactic structures, vocabulary, idiomatic expressions, figurative language, sentence construction, and tone. Selecting these features involved a careful review of the existing literature on stylistic differences between the two languages, alongside consultations with experienced language educators. These educators offered valuable insights into the specific stylistic challenges that learners typically encounter, helping to ensure that the study’s focus would be highly relevant to real-world language learning contexts.

To support this analysis, a bilingual corpus was compiled, containing a representative sample of authentic Arabic and English texts. This corpus included educational materials, literary excerpts, and formal writing samples that reflect various registers and styles in each language. Texts were chosen from diverse contexts and genres, including academic, professional, and informal, to capture a broad spectrum of stylistic features. Care was taken to ensure that these texts were appropriate for learners at various proficiency levels, making the results applicable across a range of educational contexts. Additionally, the study gathered data from surveys and interviews with language instructors who specialize in Arabic and English, providing direct insights into the stylistic features that frequently pose challenges for learners. Observations of language classes also helped identify specific gaps in comprehension, revealing how stylistic features are currently taught and highlighting areas where learners tend to struggle.

3.2 Data analysis methods

The contrastive analysis phase involved a systematic comparison of stylistic features across the Arabic and English texts in the corpus. This process involved isolating and categorizing different linguistic elements, such as syntax, idioms, and metaphors, to identify recurring contrasts and similarities. Each feature was examined in its natural context to understand how it might be interpreted by learners from either language background. Special attention was given to elements that did not translate directly between languages, as these features often pose significant challenges in language acquisition.

Quantitative analysis was employed to further investigate these stylistic features, particularly those that could be measured, such as sentence structure and idiomatic expressions. Frequency counts helped determine how often certain features appeared in each language, providing insight into patterns that could contribute to comprehension difficulties. Statistical methods were applied to assess the significance of these patterns, quantifying the stylistic distance between Arabic and English and identifying the most challenging features for learners.

In addition, qualitative analysis of data from educator interviews and classroom observations provided rich contextual insights. This qualitative data was thematically analyzed to identify recurring challenges and instructional strategies that address stylistic differences. Educator insights helped contextualize the findings from the contrastive analysis, highlighting practical approaches for bridging stylistic gaps and improving pedagogical practices. By combining these data collection and analysis methods, the study generated a detailed picture of the stylistic contrasts between Arabic and English, leading to actionable recommendations for enhancing language teaching practices and learner comprehension.

4 Result

The study concludes that there are ambiguous linguistic areas between the Arabic and English languages, which contribute to the disruption of linguistic communication among non-native Arabic and English learners. The study found many referential gaps between Arabic and English at the four levels of both languages: phonetic, semantic, morphological, and syntactic levels. The study found many referential gaps between the Arabic and English languages at the level of vocabulary, structure, and style. The study classified these gaps for the ease of dealing with them by teachers and learners. They were presented in an easy and clear way, which contributed to facilitating the educational process and alleviating the frustration of the learners of those languages. Therefore, the study hopes that it will widen the horizons for serious studies that offer effective solutions to receive these gaps and present them in various forms.

4.1 Referential gaps: term and concept

Prior to this study, this concept was not examined or investigated, and in order to ingrain it, it was necessary to consult “fajawa” entry in Lisan Al-Arab, where it found that it means the space between two things. In the hadeeth of Ibn Masoud, “None of you can pray if there is a gap between him and the Qibla, that is, he does not move away from his Qiblah or his jacket, so no one walks in front of him” (Ibn et al., 2003, p. 34).

Thus, the term “linguistic gaps” emerges from the combination of “language” and “gap” which both indicate that there is a separation, so one of the two languages (Arabic or English) is unable to literally convey a semantic, phonetic, morphological, or synthetic conception without getting help from other linguistic aspects (Al-Raini, 1992, p. 67). This is not because one of them lacks alternatives, but because the logic of each language differs in terms of its linguistic systems. If there are alternatives in a language’s system, they remain insufficient and unable to meet the requirements of the concept or idea (Al-Qurtubi, 2006, p. 78), and this forces the language to which the concept or idea is communicated to use other linguistic means to bridge this gap; however, it may not be able to grasp the meaning to be embodied or conveyed accurately, and this is confirmed by the Italian proverb that says, “The translator is a traitor” (Awwad, 2000, p. 35).

Some words in Arabic, for example, do not fully cover similar words in English, and vice versa. This makes English, for example, resort to many words, methods, and expressions to fill this deficiency, which often cannot be filled. One of the linguistic gaps between Arabic and English is the word /aʕwr/ in Arabic, which means (one-eyed) in English, and it is an expression that does not imply in its connotation the meaning of one-eyed in Arabic. In other words, the word /aʕwr/ in Arabic means (one-eyed) in English, and there is a big difference between (one-eyed) and /aʕwr/ as the latter can be used to refer to the bad manners of a man. At the same time, there are words, methods, and expressions that are available in English, but it is impossible for Arabic to come up with an equivalent that suits them completely. An example is the word ‘deconstruction’ which was translated into Arabic using several terms, including التفكيكية /Ɂltafki:kjəh/, التقويضية /Ɂltqwi:dˁjəh/, and التشريحية /Ɂltaʃri:ħjəh/. All words cannot be relied on to understand the real meaning of what it means in English as it means “demolition in order to rebuild,” which is a concept that none of the Arabic terms above correctly conveys (Na’al, 2003, p. 6).

4.2 The importance of identifying the referential gaps

Referential gaps between Arabic and English appear as obstacles and barriers that lead to wasting time and effort and inherit suffering in the learning process, and it is worth realizing the nature of those blurry areas between Arabic and English and removing their darkness by highlighting them in advance, as colliding with them without prior knowledge constitutes an obstacle and a burden in front of the educational process in the language field. This also establishes a kind of waste in the learning process that may cause a shock that repels one from learning the target language. The teachers and learners who are aware of referential gaps avoid wasting time and effort and quickly reap the fruits of the educational process (Bogrand, 1988, p. 56).

Collecting a fair number of words, expressions, and methods and putting them in the hands of Arabic and English teachers and learners provide caution while teaching students these words and methods. In addition, providing Arabic and English non-native speakers learners with a good number of these gaps helps them start learning the second language, and it provides the best way to represent these vocabulary, expressions, and styles, as it makes it easier for them to deal with them. Analyzing and classifying these words and examining the best ways to deal with them and appropriately presenting them for students design optimal teaching methods that help students and guide them. Exposing these gaps also contributes to setting standards for correct translation, as Robert de Beaugrande believes that the central study of translation is contrastive linguistics because the equality between the text and its translation cannot exist in relation to form or lexical meaning, but it is found in the experiences of those who receive the text. Accordingly, translation is a matter of intertextuality, and this stems from the principle that people are partners in the world of experiences, and they may also be partners in comprehensive formulations. The risk comes from the fact the translator may impose his/her experience as a description of the future of the text, and s/he sees it as the only experience of the text. That is, s/he may link, fill a gap, or bridge a conflict in a way that makes those who receive the translated language lack informativeness. It can also be noted that there is a real contrast between a translation based on the understanding of the translator, and a translation based on understanding the future of the text, and only the latter can claim equality in communication, and it is not possible to judge the issue of how and the possibility of preserving the meaning except in such a framework (Bogrand, 1988, p. 577).

4.3 Referential gaps in Arabic and English

Referential gaps can be found in the Arabic and English levels as follows:

4.3.1 Phonetic level

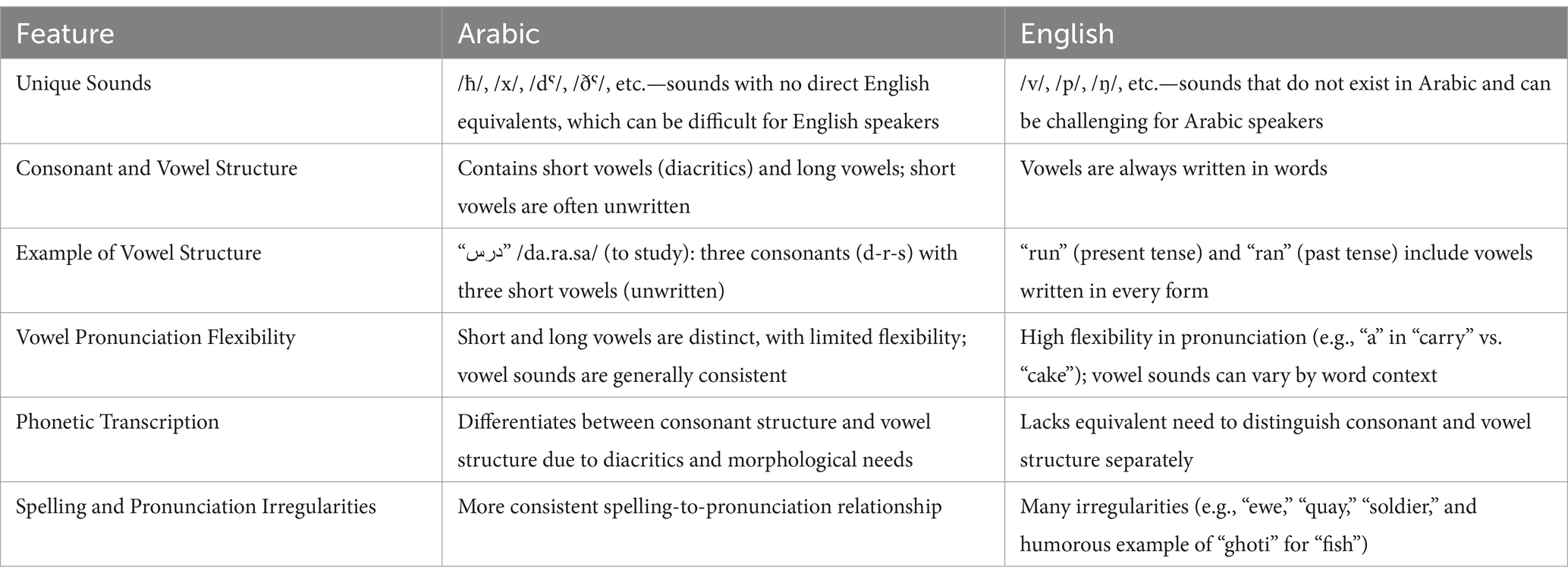

The phonetic level can be found in many differences and disparities between Arabic and English at the level of pronouncing the sounds. There are sounds in Arabic that have no equivalent and alternatives in English and vice versa. Among these sounds in English are v, p, x, and q, which are unparalleled sounds in Arabic. This prompts non-native English learners to build a delusional perception about these sounds, and, in return, there are no analogues of Arabic sounds such as /ħ/, /x/, /dˁ/, and /ðˁ/, among others in English. Such sounds illustrate complexities for the people of English, which constitutes an obstacle for the beginners of English learners, if they are not alerted in advance and focused on during the educational process. It is difficult to pronounce these sounds by learners, and they usually confuse them for ease, convenience, and agreement with the sounds of their mother tongue, especially when the multiplicity of the ways some sounds in Arabic can be written, such as alif maqsura and alif mamdoda, Hamzat Alwasl, disjunctive hamza, and Nounation, among others.

There is another gap between Arabic and English at the phonetic level in consonants and vowels, as there is no verb in English that does not include one vowel or more, or one consonant or more. The general structure of English verbs is, like Arabic verbs, formed from a mixture of consonants and vowels, but in Arabic, there are short vowels and long vowels. Short vowels in Arabic are diacritics, but they are not usually written in words. For example, if we want to analyze the phonetic structure of the verb /da.ra.sa/, it has three consonants and three vowels.

In English, vowels are always written in English words. For example, (ran) is formed from a consonant, a vowel (a long vowel that corresponds to the alif sound in Arabic), and a consonant. The verb (run), which is the present verb of (ran) has a consonant, a vowel (a short vowel that corresponds to the fatha sound in Arabic), and a consonant. So, (u) corresponds to the Arabic fatha, and (a) corresponds to the Arabic alif or the long fatha. However, this case is not the same in all cases. For example, (a) may be pronounced as a short fatha such as in the word (carry), i.e., (a) may be pronounced as a short or a long vowel in English. This also does not always apply. For example, the (o) sound can be pronounced to the short Arabic fatha such as in (done).

All these issues lead to two things, mainly the phonetic transcription of the English vowels does not depend on the pronunciation standard, and it is not possible to make a comparison between the Arabic actual structure and the English actual structure according to the criterion of correctness in both structures. In Arabic, we need to distinguish between the correct verbal structure and its vowel counterpart due to morphological considerations, and because vowels—whether they are present or not—represent a diacritic sign, especially if they come at the end of the verbal structure. In English, however, there is no counterpart for such matters, and therefore they do not need to distinguish between the correct structure and the vowel structure, which constitutes a burden on non-native learners of Arabic and English (Al-Aqtash, 2009, 65). The English language is also famous for a different spelling method than the written one in the sense that, in many cases, the correct pronunciation of a word has nothing to do with the letters that make it up, such as (ewe), (quay), and (soldier), etc. This prompted the Irish satirist George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950) to ridicule the spelling of English words, asking why the word fish is not written as ghoti, saying that (f) should be written using (gh) as in enough, the (o) as in women, and (ti) as in nation. This is something that can be found in Arabic but to a lower extent, such as /amro/ which is pronounced as /amr/ (Table 1).

4.3.2 Semantic level

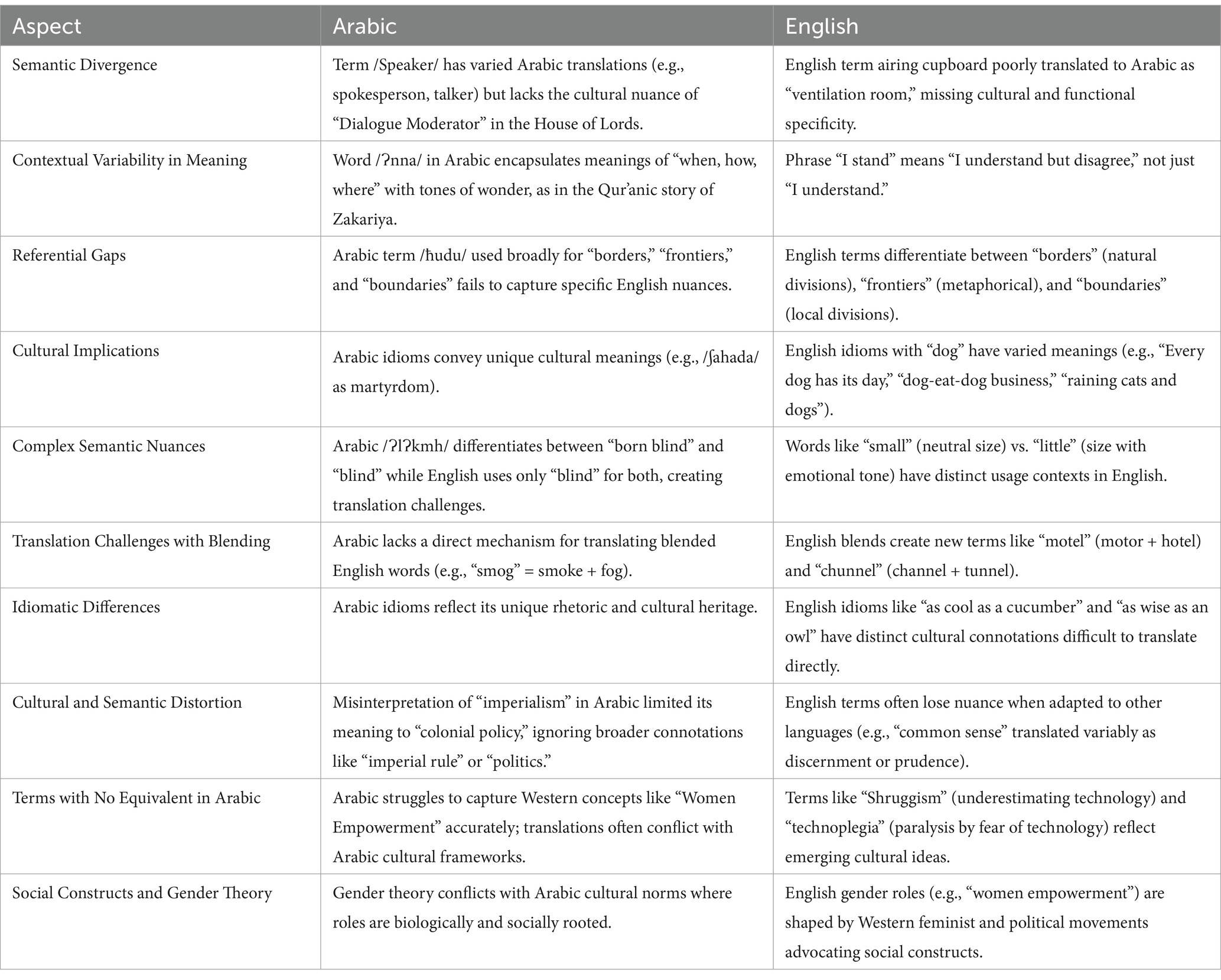

The semantic level between Arabic and English is overflowing with linguistic gaps, and several formations have taken place, including those related to the origin of the semantics, where the semantics diverge between two apparently similar terms in the two languages, such as the word (speaker), which carries in its semantic origin in English shadows of a meaning that is difficult to achieve in Arabic, which means Dialogue Moderator in the English House of Lords (Al-Baalbaki, 2010, p. 23). This term was translated into Arabic by several concepts, which in English mean spokesperson and talker, among others, and all of them are concepts that do not touch the linguistic reality of the word used by English people today. Another example is the term (atring cupboand), which has been translated into Arabic as a ventilation room; however, its linguistic reality among its people carries a special concept that has many determinants and features in the English linguistic reality. It specifically means a special room in the house that has specific uses that cannot be found in Arab culture. It is difficult, if not impossible, to embody these determinants and features in the Arabic linguistic reality, so it was transferred to Arabic with an approximate undefined translation, trying to represent the true meaning that remained something specific to the English mindset.

Other terms are related to the semantic multiplicity in their relationship to the contexts of use, such as the word (I stand) in the translated Arabic language requires a concept that is almost constant and clear in the sense of ‘I understand you,’ but, in fact, in English, it is used differently from the way it is used in Arabic. It means I understand and hear what you say, and I do not agree with you, and I cannot tell you what is inside my mind, so I will let you suffer by not answering your comments (Al-Baalbaki, 2010, 23). In addition, there is Arabic vocabulary that has distinctive features that make it difficult for English to express what is meant by them. An example is the word /Ɂnna/ which means (when, how, and where) all at once, so English does not have these three words combined in one word. Although the Arabic word can be translated using three words, they still lack the tones of wonder, amazement, and astonishment, such as in the Qur’anic context, when Zakariya, may Allah be pleased with him, entered Mary’s mihrab and found grapes in winter, he said to her: “How did you get this?” (Al-Suyuti, 1987, p. 67).

Referential gaps at the semantic level may take another pattern in which a single word in a language carries accurate and specific meanings when the other language lacks them. An example is the following three words in English with their nuances: borders, frontiers, and boundaries. These three words have all been translated into one Arabic word, i.e., /ħudu:d/, although there are many differences in the meaning and usage between the three words as follows:

The words ‘borders’ and ‘frontiers’ agree that they both mean the borders between two countries or two states, while they differ in that the word ‘borders’ is usually used to mean the natural borders between two countries or states, while the word ‘frontiers’ is used in metaphorical expressions, such as when we say, ‘Frontiers of knowledge/ science,’ and this does not apply to the word ‘borders.’ As for the word ‘boundaries,’ it is used to refer to regions or administrative divisions less than a country or state, such as the borders between counties (provinces) and parishes, such as “The boundaries of my garden.”

The semantic dimension may be a result of the implicature relationships related to metaphor and simile, such as the word table, as in ‘This is a large table,’ as it refers to the table and food together. This linguistic characteristic exists in Arabic as an aesthetic, rhetorical, and artistic value that presents a sophisticated linguistic level and a high style of eloquence. This is a feature that can be also found in English, as sometimes we have to translate one word in a line or even in a paragraph, such as the word “picket” which means a person assigned by a labor union to stand outside a workplace in order to discourage workers or customers from entering the building during a strike.

Referential gaps also exist at the semantic level if various cultures and international relations camouflage words with emotional meanings such as “martyrdom” that has a connotation slightly different from the Arabic equivalent /ʃahada/. In other cases, the original words such as “jihad” and “sharia” can be used. Here, it can be assumed that the reader needs the necessary background to understand the meaning, and the importance of these decisions cannot be underestimated because of their impact (Cook, 2008, p. 69).

Sometimes, English words refer to more than one person such as the word ‘uncle’ which refers to the father’s brother and mother’s brother, and this indicates that there are some words that do not have a single equivalent in Arabic, and the reason is that Arabic is based on the derivation and that the Arab social circumstance focuses on the details of human relations. This reflects the nature of society, while the philosophy of Western and English society, in particular, does not give much attention to this issue, as it has a word and applies it to many relatives. Moreover, English has many words that consist of parts of two or more other words, which is called “blending.” Some examples are the word “smog” which is composed of (smoke + fog), the word motel which is composed of (motor + hotel), the word brunch, which is composed of (breakfast + lunch), and the word chunnel, which is the tunnel under the sea to connect England and France, and it is composed of (channel + tunnel).

There are some linguistic and semantic differences in the Arabic language that are not reflected in the words of the English language. For example, the word /ɁlɁkmh/ in Arabic is the person who was born blind, but the English language uses the word ‘blind’ in exchange for the two words. This is inaccurate, and this is one of the semantic differences that caused difficulty for the Qur’an translators who eventually agreed to use “blind” and “born blind (Tawfiq, 2012, p. 56)”. There are some simple semantic differences between the English words that are not considered during translation into Arabic, and at that time, make a gap that contributes to the failure of delivering the message, such as the difference between the uses of the words ‘small’ and ‘little.’ The word ‘small’ is used if we are talking about something in a neutral manner that is not accompanied by feelings of love or hate, such as in “This room is smaller than the old one.” As for the word ‘little,’ it is used when the speaker’s words are accompanied by feelings, such as in “We have a lovely little house,” or “I hate that little thing.”

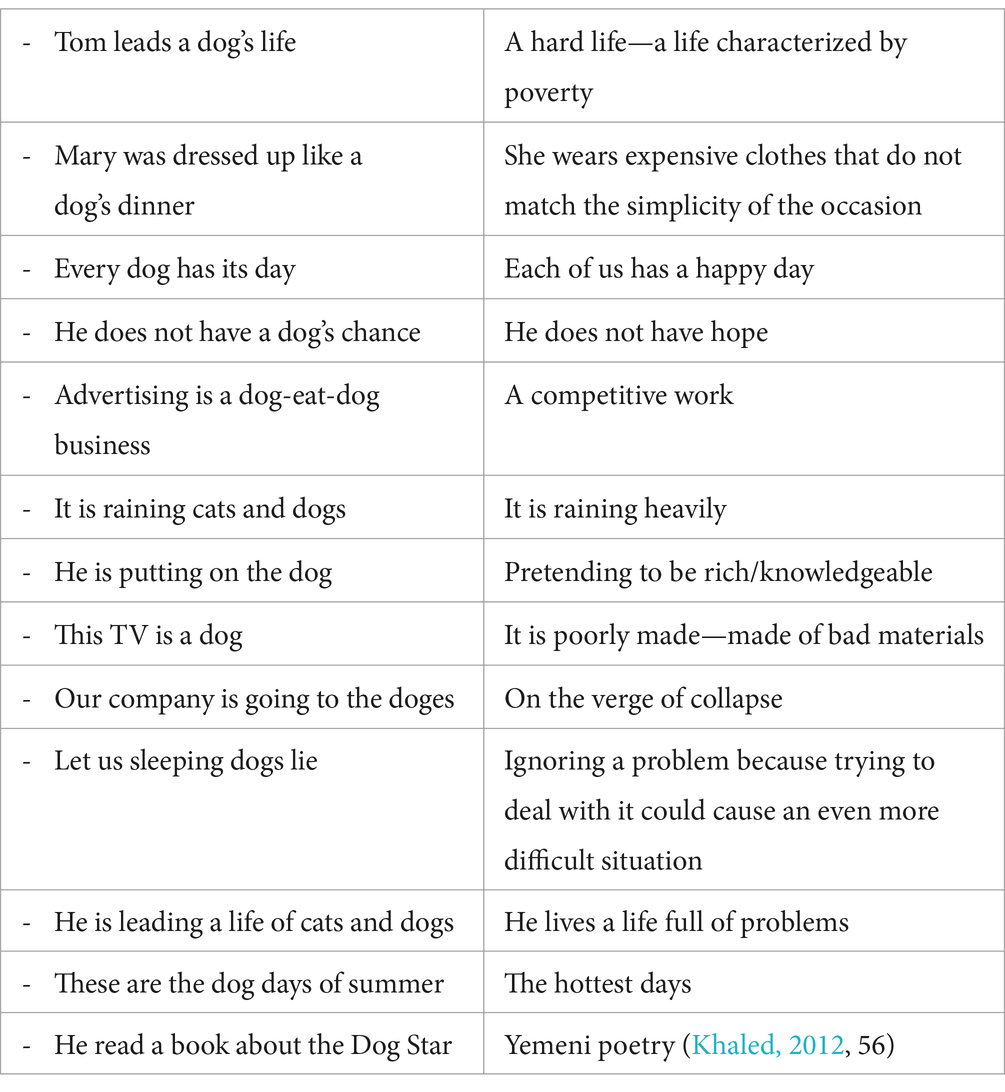

Some referential gaps have emerged as a result of expressions that are difficult to translate despite the translator’s knowledge of them. An example is the expression (common sense) which has been translated into Arabic as discernment, prudence, social intelligence, sound mind, good intuition, and mindfulness, among others (Tawfiq, 2012, p. 56). In addition, some gaps were formed due to idioms, where one word may be used in different expressions to refer to different connotations of a word. An example is the word (dog), and below are some of the idioms in which the word ‘dog’ is used and has different meanings:

Gaps may also occur at the semantic level because of the exposure of some words to distortion, which is called semantics degradation. Among the English words that were misused in the Arabic language is the word “imperialism,” and it was only used to mean colonial policy; therefore, TV channels and Arab radio started cursing imperialism every day, so that the meaning of this word in people’s minds is limited to this direction only, although this word can be directed to “imperial rule” or “imperial politics,” which are important expressions that are usually used when talking about civilizational expansion or how the concept of the modern state emerged.

The linguistic gaps at the semantic level caused the emergence of some expressions that may not be accepted in the Arab culture due to the different symbols and connotations of some creatures in the English culture from those in the Arab culture, such as (Tawfiq, 2012, p. 56):

1. As graceful as a swan

2. As blind as a beetle

3. As merry as a cricket

4. As cool as a cucumber

5. As wise as an owl

6. As quite as a mouse

7. As silly as a goose

Furthermore, some terms did not keep up with the Arabic novelty and lacked their meaning, but the Oxford Dictionary added them, such as “Shruggism” which means underestimating the seriousness of technology, and “technoplegia” which means fearing technology to the point of being paralyzed and unable to think or act.

Additionally, some men between the ages of 35 to 45 start behaving childishly, which is called nowadays “adult scent,” and there is a funny English expression “tea bag,” which, if translated, would not mean a (tea bag), but it was translated into the Egyptian dialect as a funny translation, which is [tea Abu Fatla (Tawfiq, 2012, p. 45)], in addition to the English term (female empowerment), which is a vague term that has no synonym in any language of the world, according to the words of one of the Russian translators. It is a controversial term that is translated inaccurately in the official documents of the United Nations (Al-Masoudi, 2012, p. 65).

Likewise, the term Women Empowerment is translated as /tamki:n ɁlmarɁa/ which is a wrong translation that changes the meaning and content and directs understanding in a completely different direction. The word /tamki:n/, i.e., “empowerment,” is a Qur’anic word that is positively accepted by the Arab and Islamic mentality: empowering women with the rights granted to them by Islamic law, and there is nothing wrong with that. While the synonym for the word /tamki:n/ in English is the word ‘enabling,’ not ‘empowerment,’ so, the correct translation of the term (Women Empowerment) is /ɁstiqwaɁ ɁlmarɁa/ which means empowering women to overcome men in the conflict that governs the relationship between them according to the Western culture that produced that term (Faydouh, 2009, p. 67). This term also goes in line with the radical feminist movement, which adopted the principle of conflict between the two sexes—female and male—based on the claim that hostility and conflict are the root of the relationship between them, and called for a revolution against religion, God, language, culture, history, customs, and traditions. It also sought a world in which the female centered on herself, completely independent of the world of men (Al-Kurdistan, 2004, p. 67), and empowerment resulted from the radical feminist movement that sought to eliminate what it called “male domination,” so it developed a political theory that focused on standardizing gender roles by separating the human race from its role in life and disengaging the human race from a specific role in life. That is the theory of “gender.”

The theory of “gender” is summarized in the fact that it is society that divides roles between men and women, and these roles have nothing to do with the innate biological structure of each. The woman, according to that theory, raises the children, takes care of the family, and obeys the husband, while the man bears the responsibility of hard work, spending, and guardianship within the family because it is society that divided those roles through family education (choosing a name, activities, toys, clothes, and sports for the girl different from the boy) and societal culture. Then, if it is possible, according to that theory, to change the pattern of family education and societal culture, then it is possible to change the roles of both men and women within the family and society! This is the basic idea on which “gender” is based (Table 2).

4.3.3 Morphological level

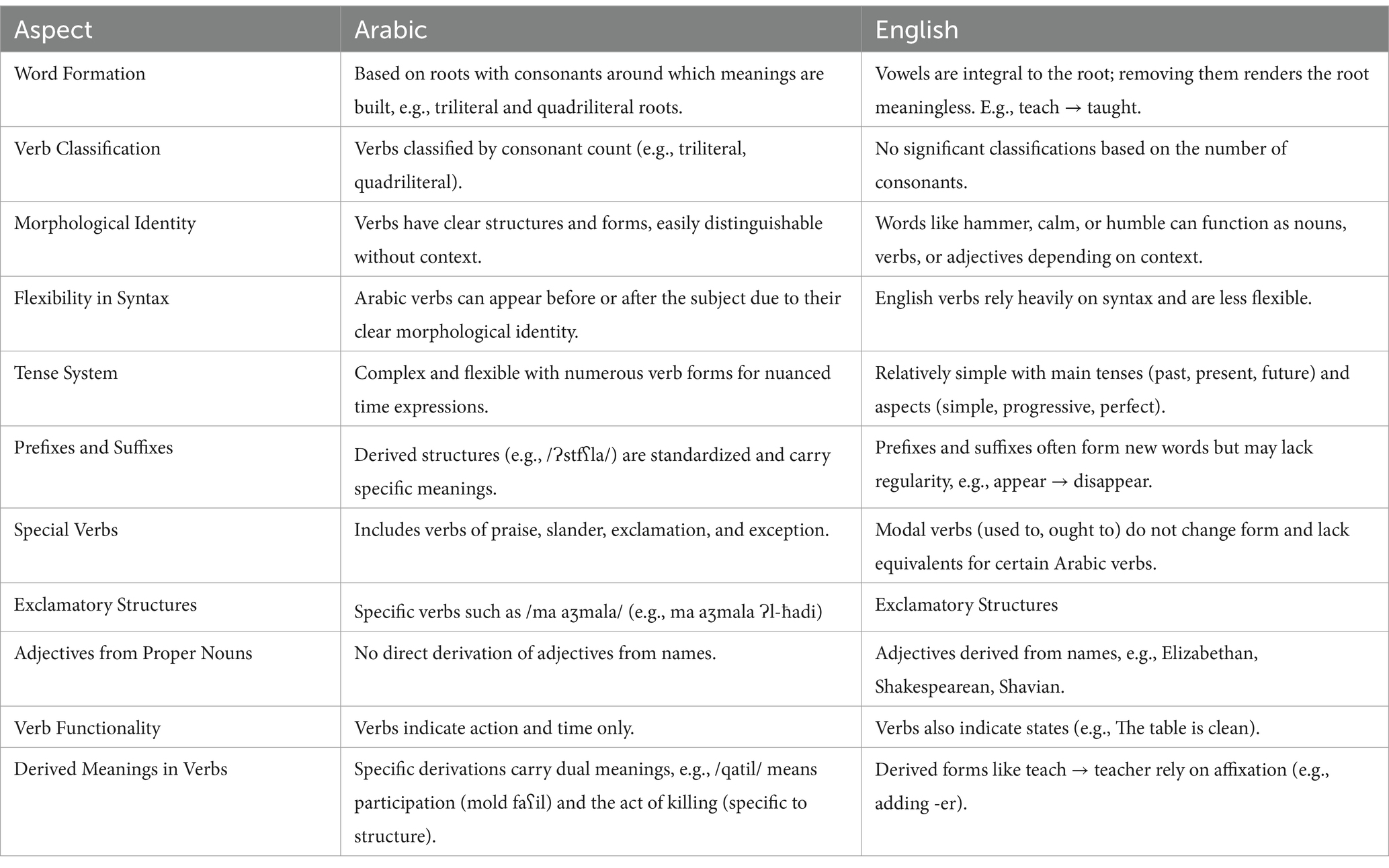

The linguistic gaps appear at the morphological level in what distinguishes the structure of the Arabic word from the possibility of returning the origin of its formation to a group of consonants around which a general connotation can be drawn, and from which formulas branch out with other connotations according to what is required by the nature of the pairing between consonants and vowels such as the root.

Conversely, in English, we cannot refer to the origin of the word as a group of consonants around which a connotation can be drawn. The word ‘teach,’ for example, is a lexical root, and if vowels or diacritics are removed, we will have two silent phonemes (t, ch), and these two have no significance. This applies to roots that have three consonants or more. Accordingly, the vowels in the structure of an English word are part of the root, i.e., the root of the English word is only by the mixture of the vowels and the consonants together. So, vowels in English do not play the main role in the root of other words, so if we want to formulate the structure of the past tense from the verb ‘teach,’ we need to use a technique that has two elements: substitution and addition, as we replace the vowels (ea) with the vowel (au), and we add the silent (t) to the end of the structure so that the past structure becomes (taught), and, in many forms, the prefix or the suffix is relied upon to generate other forms. The word (teacher) was formed by adding the suffix (er) to the verb (teach).

The structure of Arabic verbs is also divided in terms of the number of consonants in it, so there are triple verbs, quadruple verbs, more triples, and more quadruples if the structure of the verb has one of the additional letters. In English, there are no such classifications, as the number of verb consonants has no significant morphological advantage, whether these consonants are few or many.

In addition, word divisions can accommodate the morphological identity of all words in English, including verbs, as some verbs share their structure with other parts of speech (Huddleston, 106). For example, the word ‘hammer’ can be a noun and a verb. In addition, the word ‘calm’ can be an adjective as in ‘The sea is calm,’ and a verb in ‘You must calm down.’ Another example is the word ‘humble,’ which can be an adjective as in ‘He is very humble,’ and a verb in ‘We must humble them.’ Here, context is what is mainly used to distinguish the morphological identity of many words in English.

There is no problem for the Arabic student in distinguishing the verb from other parts of speech, as it is, in general, molded within a group of abstract and additive forms. These are standard formulas, where each of which retains features of form and meaning, but in English, the student may be lost in defining the morphological identity for the word, as the structures of many verbs use nouns, adjectives, and gerunds, and, in this case, the English student has no choice but to resort to the context in distinguishing the verb from other parts of speech.

Likewise, the structure of the verb in the Arabic and English languages is divided into abstract and compound, and the abstract structure in both is the root, except that the abstract structure in Arabic is different from its counterpart in English in terms of the morphological meaning. In general, one can distinguish the Arabic verb from its structure, form, and conjugation, without needing contextual clues. Perhaps this is the reason why it enjoys a free position in the context, as it can precede the subject or come after it, but in English, it is not easy to distinguish the verb through its free and absolute structure, whether abstract or not, so the actual structure in English may indicate the noun, adjective, or gerund (Mazban, 2004, p. 56).

The English time system is based on a balanced engineering basis. This system adopted the philosophical division of tenses, i.e., the past, the present, and the future. From these main tenses, there are aspects: progressive, perfect, and simple. For example, there are progressive verbs in the past, present, and future tenses. It seems that the general linguistic system in English does not need more than these tenses and their aspects, but in Arabic, the case is not the same. Perhaps the flexibility of Arabic in expressing time in different verb forms has caused modern grammarians to get confused when they try to enumerate the Arabic time aspects. So, the terms and directions varied until it becomes difficult for learners to deal with (Al-Kurdistan, 2004, p. 45).

Words in English can have prefixes and suffixes, and it is basically what forms a new word, and it mostly does not have a meaning related to the lexical root that is part of it. The ‘appear’ root has a meaning that opposes the derived word ‘disappear.’ On the other hand, the prefix that comes at the beginning of a lexical verb does not have a regular form, i.e., the prefix (dis) cannot be combined with other root verbs such as act, miss, and build. In Arabic, however, the derived structure, like root verbs, is also molded. For example, we have many verbs with /Ɂstfʕla/. In addition, the molded word has two specific meanings. For example, the verb /qatil/ (in English: a killer) carries the meaning of participation, which is the connotation of the mold “faʕil,” and it carries the meaning of the act of killing, which is the connotation specific to the structure, contrary to what is the case in English (Al-Aqtash, 2009, p. 33).

In addition to the above, we find, at the morphological level in English, verbs that do not change, i.e., modal verbs, such as used to and ought to, while in Arabic there are many verbs described as ‘solid,’ such as verbs of praise and slander, verbs of exclamation, and verbs of exception. They are the same verbs that some modern scholars, such as Tammam Hassan, called for reconsideration to change its classification from general verbal structures, which reinforces the view that many of these verbs have no equivalent in the English verbal form. For example, if we want to translate a sentence such as /ma aʒmala Ɂl-ħadi:qa!/, we have no choice but to say: what a beautiful garden! So, the form /ma aʒmala/ is equivalent to (what a), which is a purely emotional exclamatory form, which has nothing to do with verbs (Al-Aqtash, 2009, p. 171).

There is an adjective that is specific to English in terms of derivation, which is the presence of adjectives derived from the names of politicians, writers, authors, and wise men. For example, the adjective from Elizabeth, Queen of England, is Elizabethan, the adjective from Shakespeare is Shakespearean, and the adjective from the name of the famous writer “Bernard Shaw” is Shavian (Tawfiq, 2012, 95). In addition, English verbs, in addition to their indication of event and time, are distinguished for the state as in the sentence ‘The table is clean,’ while in Arabic it denotes the event and its time only (Al-Zarkali, 1923, p. 78; Table 3).

4.3.4 Structural level

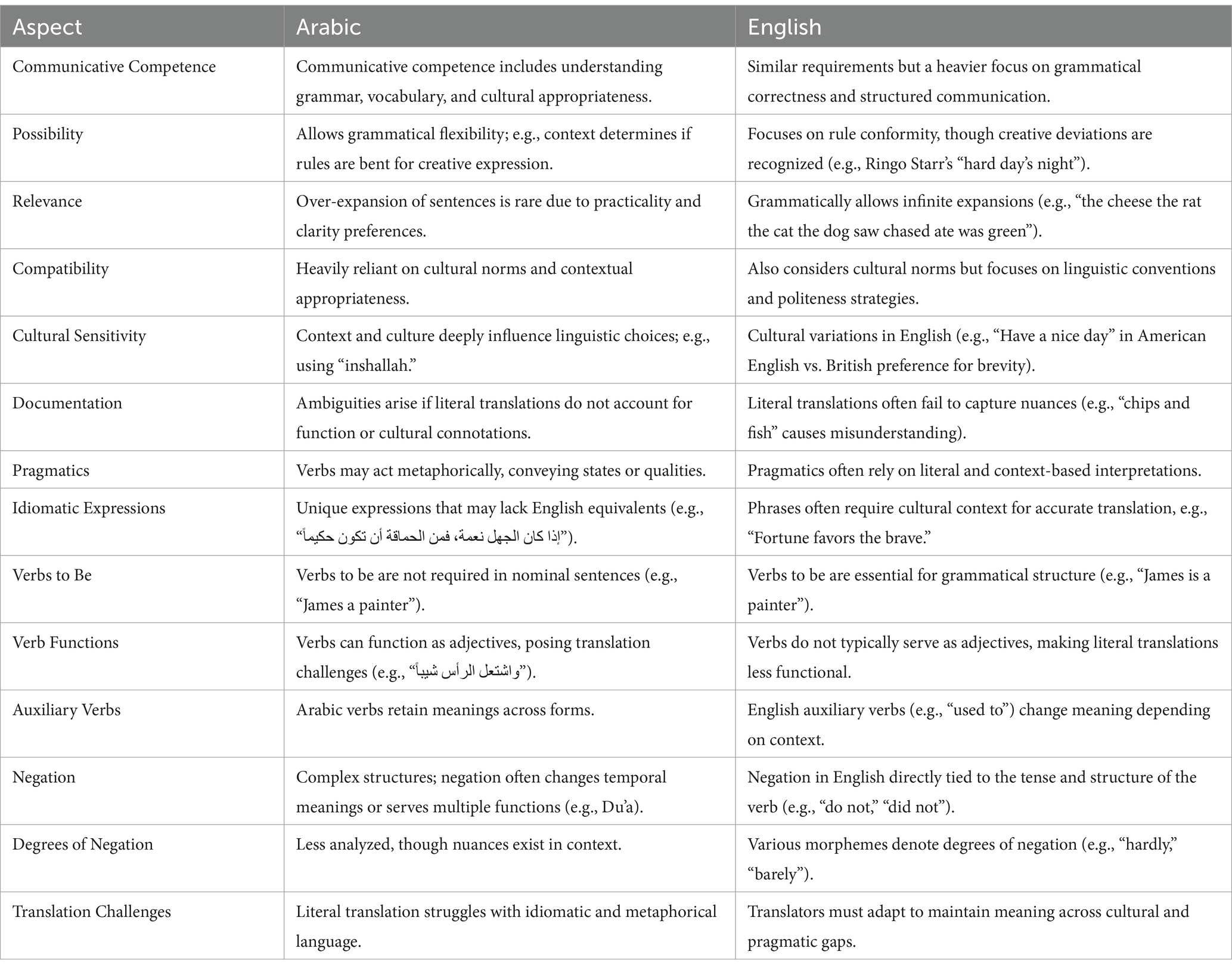

Linguistic gaps emerged at the structural level of the Arabic and English languages first in what can be called Communicative Competence (Cook, 2008, 63). Understanding the rules and vocabulary of the language, despite its necessity, is only a step to achieving communication. In other words, the ability to put the rules and vocabulary into use requires other types of knowledge and skill, and some things are more important to use language than knowing grammar. These types are possibility, relevance, compatibility, and documentation, and without them, there will be a kind of social miscommunication that tries to produce grammatical sentences that are not compatible with language grammatical structures.

The possibility is that the speaker with communicative competence knows what is formally possible in the language, i.e., the sentence conforms to the rules of grammar and pronunciation. Speakers should know, for example, that the phrase ‘Sleep now me go’ violates these rules, while the phrase ‘I am going to sleep now’ is considered grammatical. Knowledge of the possibility alone is not sufficient for communication. For example, the phrase ‘I am going to sleep now’ may be grammatically, semantically, and logically correct, but it may not make sense in a certain situation, while the phrase ‘Me go to sleep,’ although it is grammatically incorrect, it may be meaningful and appropriate. Moreover, speakers with communicative competence may understand the rules and can follow them efficiently, yet they sometimes violate them on purpose. This may be the case when one tries to appear clever and creative, to be a close friend, or to talk about something for which the language does not contain a synonym. An example is the well-known saying made by Ringo Starr, a member of the Beatles, after he spent many hours preparing a movie which is “That was a hard day’s night,” and it became the title of a song and a movie, despite her violation of semantic rules, it expressed the idea wonderfully.

As for relevance, it is a psychological concept that is concerned with the limits of what can be processed in the mind. For example, in English grammar, it is possible to expand the nominal phrase to make it more specific, so the phrase ‘the cheese’ could become ‘the cheese the rat ate,’ and likewise, ‘the rat’ can be expanded to become ‘the rat the cat chased,’ and, theoretically, this can allow expanding the sentence infinitely such as the following sentences:

The cheese was green.

The cheese the rat ate was green.

The cheese the rat the cat chased was green.

The cheese the rat the cat the dog saw chased ate was green.

The cheese the rat the cat the dog the man beat saw chased ate was green.

The last two sentences are almost impossible to use in communication as they sound even more ridiculous than the impossible example ‘Me go sleep now.’ They are possible, but they are incongruous and cannot be used, not because of a grammatical error, but for the difficulty in addressing them. The criticism of this statement is not on the grounds that it violates grammatical rules, but on the grounds that it is inappropriate, and thus makes important information unnecessarily vague.

The third component of communicative competence is compatibility. This component deals with language or behaviour’s relationship with context and its importance in view of its opposite: incompatibility. For example, something may be incompatible with a particular relationship (when you call a police officer ‘dear’ or caress him when he reprimands you), a specific script (such as the use of slang or taboo words in a formal speech), or a specific situation (when you answer your mobile phone during a funeral, for example), or, generally, it does not agree with a certain culture (disregarding the elderly). Appropriateness involves the observance of social norms and the need to observe society’s traditions when they are incompatible with another society. Therefore, European women are advised when they go to the Gulf countries to wear gowns to avoid any abuse, and Muslim women who visit or live in the West may be under pressure to stop covering their heads, i.e., wearing Hijab (Al-Isfahani, 2009, p. 57).

While ignoring or not knowing cultural norms, people will not only suffer from a lack of understanding but also misunderstanding in some cultures. For example, nodding the head indicate acceptance of something, while the same gesture means rejection in other cultures. People are accustomed to physical contact when getting acquainted—kissing as a greeting, for example—which is what makes them judge those who do not share the same style as not welcoming. Another example is when people who are accustomed to being calm even in the most difficult situations see the most talkative and gossipy cultures as impulsive and insensitive. In other words, some gestures make some indications, with the possibility of disastrous results that may affect understanding in multicultural communication situations. One of the main goals of applied linguistics is to raise awareness of the degree of compatibility of behavior with culture, which is necessary to confront intolerance and contribute to improving community relations and resolving conflict in general.

Such issues, though easy to see in nonverbal behaviour, do arise with the use of language. Should learners of a particular language adopt the way it is used? Can a Japanese speaker, for example, keep to the polite norms of his culture, even when speaking English? Should an Arabic speaker not mention his references to Allah while speaking in English, will it be considered incompatible, for example, when he says, “inshallah” to answer a question about the possibility of something happening in the future? Such cultural differences occur even between speakers of the same language as many British English speakers find phrases used in the United States wrong or stilted, such as “Have a nice day” and “Your call matters to us.” In contrast, many American English speakers find the English used in Britain laconic and dry (Al-Anbari, 1960, p. 47).

The fourth component of communicative competence is knowledge of documentation. For example, “chips and fish” is a possible statement as it does not violate any grammatical rule, is appropriate as it is easy to understand, and is compatible as it does not conflict with any social norms, yet it does not communicate meaning but causes misunderstanding (Al-Baalbaki, 2010, p. 89).

These gaps also came in the structural (pragmatic) study, which is the field of study that tackles the knowledge and procedures that enable individuals to understand the words of others. Such studies do not mainly focus on the literal meaning, but on what the speaker generally intended to communicate. For example, a grammatically simple and usual question such as “How are you” is an interrogative sentence in the English language, and when looking at the literal meaning, we will find that it is a question about a person’s health, and it may be, more hypothetically, a greeting where it is answered reciprocally with words such as “Fine. Thanks, how are you?” It can also refer, depending on the context, to other connotations that may be answered through any of the following examples: “Mind your own business” (where you deny the undue care from a stranger), “Do not make me sick” (after an argument), “Deeply Depressed (while thinking of a recent bad situation), or “Thanks be to God” (usually by Muslims speaking English). In other words, the significance varies according to the circumstances, and it is easy to think of situations where all these responses would be effective and appropriate.

This level includes what is called the clash of ideologies, such as the ‘self-sacrificing operation’ and the ‘martyrdom operation,’ although Western radio and TV channels use other expressions that reflect what they believe, such as ‘terror operation,’ ‘terrorist operation,’ ‘self-bombing,’ and ‘suicidal operation.’ In addition, the person who carries out these operations is translated by Arab radio stations as ‘martyr’ or ‘self-sacrifice,’ which are the closest translations for the word ‘martyrdom,’ while Western stations translate it as ‘terrorist’ or ‘self-bomber,’ which is the closest translation of the word ‘terrorist’ or ‘suicidal.’

The Arab media uses the term “separation wall,” while Israel calls it the “security wall,” as follows:

• Separating Wall/Fence/Barrier

• Separation Wall/Fence/Barrier

• Apartheid Wall/Fence/Barrier

• Isolating Wall/Fence/Barrier

• Isolation Wall/Fence/Barrier

Linguistic gaps at the level of the structural level appear when the structure of a sentence does not have an equivalent in Arabic, at the meaning or the verbal level, so it would be translated as it is. Below are some examples:

When ignorance is a bliss, it is folly to be wise. الجهلإذا كان نعمة، فمن الحماقة أن تكون حكيماً.

Ill news travels fast. تنشرالأخبار السيئة بسرعة.

No news is good news. هوأفضل خبر عدم وجود خبر.

Fortune favours the brave. الجُسوروفاز باللذة.

A stich in time saves nine. فيعمل غرزة وقتها يوفر تسعاً من أمثالها.

Among the structural gaps is what is related to the verbs to be, as the ‘verbs to be’ are included in English to express the state, and it is known that this function can be performed by the nominal sentence in Arabic. Perhaps this discrepancy results from the necessity of each sentence in English to include a verb, such as in ‘James is a painter.’

The verb to be (is) was used to express the state of the subject James, while the Arabic equivalent of this sentence consists of a subject + predicate: (James a painter). The sentence here does not need a verb in Arabic, and if the Arab learner wants to translate a nominal phrase from his language into English, he may not use ‘verbs to be’ that fit the sentence, so he translates the sentence ‘the morning is beautiful,’ for example, into ‘the morning beautiful.’

Verbs in Arabic are also distinguished in that they can perform the function of an adjective, and this is evident in metaphorical expressions, and there is no doubt that this matter raises a problem at the level of translation, whether to translate the verb in terms of its function or in terms of the literal meanings of the verbs and words used to express an adjective.

In the Quranic verse {{رَبِّ إِنّيِ وَهَنَ الْعَظْمُ مِنّيِ شَيْباً الرَّأْسُ وَاشْتَعَلَ, in English {My Lord! Indeed, my bones have grown feeble, and grey hair has spread on my head} [Maryam: 4], the two verbs (وَهَنَ—have grown feeble) and (اشْتَعَلَ—has spread) indicate the characteristic of the speaker Zakariya, peace be upon him, which means old age. So, the translation did not consider the functional meaning of the verb, so it may be appropriate to translate the verse in light of that, so we say: My Lord! I became too old. The Arabic verb retains its lexical meaning in the compound structure, while the form of the verb and its meaning can change in English, and examples of that are the past tense (used), as it is a lexical verb and its conjugation: Use—used—used, and if we add the morpheme (to) to it, it turns into an auxiliary verb that means habituated, not made use of. The following two sentences show both uses.

• We used pencils in writing (made use of)

• I used to drink Coffee every morning (habituated)

Linguistic gaps also have the difficulty of teaching negation in Arabic in the absence of the temporal morphological meaning of the structure of the main verb when some morphemes of negation are combined, as the structure of the present tense with the morpheme of negation can express the past or future time in many forms, while the negative context in English acquires its temporal significance is that of the verb that forms part of the interrogative form, and something like this should be taken into account on the theoretical and practical levels.

Perhaps one of the most prominent expected difficulties in teaching the Arabic negation method is that the structure of “no verb” in most of its uses deviates from the meaning of negation and is useful for making Dua’a (prayers), and there is a big difference between both functions that should be considered during the learning process.

In English, the degrees of negation are different from in Arabic. In many contexts, negation is not complete, and the affirmation is not complete as well, and there are certain morphemes in English that measure the degree of negation in the context. It seems that this matter does not have a sufficient presence in Arabic literature at the study and analysis level (Table 4).

5 Discussion

The findings on linguistic gaps between Arabic and English highlight the need for a pedagogical framework that addresses both structural and cultural differences, offering practical insights into curriculum development. For instance, the structural contrasts in verb usage, such as the omission of “to be” in Arabic nominal sentences and the metaphorical use of verbs, emphasize the importance of explicit instruction on sentence construction and meaning negotiation. Language curricula should include targeted exercises that address these gaps, such as activities that train Arabic learners to incorporate auxiliary verbs into English sentences and encourage English learners to grasp the contextual flexibility of Arabic verbs. Incorporating visual aids, comparative sentence structures, and functional grammar lessons could bridge these structural differences effectively.

Cultural pragmatics, as discussed, also have profound implications for language teaching strategies. The varying uses of expressions like “inshallah” in Arabic and “Have a nice day” in English underscore the importance of teaching language in context. Curriculum developers should integrate modules on sociocultural norms and their impact on language use, helping learners navigate cultural appropriateness and communicative competence. For example, role-playing scenarios or cross-cultural simulations could prepare students to adapt their speech in diverse settings, fostering an understanding of context-sensitive language use. Additionally, training in pragmatic functions, such as how to address politeness, directness, and idiomatic expressions, can improve learners’ ability to interpret and respond appropriately across linguistic boundaries.

Finally, the implications for translation studies and advanced language pedagogy are particularly noteworthy. Translation curricula should emphasize the challenges posed by ideological and idiomatic differences, equipping learners with strategies to handle sensitive or culturally loaded terms like “martyr” or “terrorist.” Pedagogical approaches could include comparative analysis of texts in Arabic and English, highlighting ideological shifts and encouraging critical thinking about word choice. Moreover, addressing pragmatic and structural gaps through translational theory can inform bilingual education programs, promoting linguistic and cultural fluency. By prioritizing these theoretical insights in curriculum design, educators can enhance not only learners’ language proficiency but also their ability to engage meaningfully in multilingual and multicultural contexts.

6 Conclusion

The study concludes that ambiguous linguistic areas between Arabic and English present substantial challenges for learners of both languages, leading to disrupted communication and comprehension among non-native speakers. These issues arise from significant referential gaps at multiple levels: phonetic, semantic, morphological, and syntactic, as well as in vocabulary, structure, and style. The study’s classification of these gaps is intended to aid educators and learners in addressing these linguistic differences more effectively. Presented in a clear and accessible format, these findings aim to streamline the educational process, mitigate learner frustration, and provide a foundation for instructional improvements.

The study’s findings carry significant theoretical implications for understanding language transfer and cross-linguistic interference in second language acquisition. The identification of referential gaps at phonetic, semantic, morphological, and syntactic levels supports the notion that language learners often carry over linguistic structures and phonetic characteristics from their native language, affecting their proficiency in a target language. This research contributes to contrastive linguistics by highlighting how certain structural, phonetic, and referential elements are uniquely expressed or omitted in each language. By examining these differences systematically, the study lays the groundwork for further investigations into how specific linguistic gaps may hinder comprehension and production in bilingual contexts. Moreover, the classification of these gaps may inspire additional research into how language typology affects learner expectations, particularly in cases where linguistic structures lack direct equivalents between languages.

Practically, these findings offer substantial benefits for curriculum development, instructional strategies, and assessment design in Arabic and English language teaching. The categorization of referential gaps provides a framework that teachers can use to anticipate common areas of learner difficulty and design targeted interventions. Furthermore, the study’s recommendations for presenting linguistic concepts clearly and accessibly can guide the development of educational materials that are more intuitive for learners. For example, language textbooks, digital resources, and interactive tools can incorporate the study’s gap classifications, making explicit the areas where learners may struggle and providing exercises that reinforce correct usage in both spoken and written language. Finally, by demonstrating that learners’ frustrations can be alleviated through targeted instruction, the study encourages the adoption of learner-centered methods that prioritize clear explanations, scaffolded practice, and direct comparisons between Arabic and English linguistic features. These methods can reduce the cognitive load on learners, enhancing their confidence and motivation. In doing so, the study offers a foundation for additional pedagogical studies aimed at creating more adaptable, evidence-based language learning programs that address referential gaps in innovative ways.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

NA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AB: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Al-Aqtash, I. (2009). Verbs and their applications between Arabic and English. Amman: Dar Al-Yazuri for Publishing and Distribution.

Al-Dilaimy, H. H. (1998). Reference in English and Arabic: A contrastive study (Doctoral Dissertation, Council of the College of Arts, University of Baghdad).

Al-Qurtubi, A. (2006). The collector of the rulings of the Qur’an. Abdullah Al-Turki, Al-Risala Foundation: Edited by.

Al-Raini, S, (1992). Tariq Al-Hillah, and healing the illness, edited by: Rajaa El-Gohary, university culture foundation, Alexandria.

Al-Suyuti, J, (1987). Al-Mizhar in linguistics, edited by: Muhammad Abu Al-Fadl and others, Beirut, Al-Babi Press.

Awwad, S. (2000). The beautiful contract in the art of the beautiful, edited by: Hassan Noureddine. Beirut: Dar Al-Mawasim.

Bogrand, R. (1988). Text, discourse and procedure, translated by: Tamam Hassan. Cairo: World of Books.

Cook, I (2008). Applied linguistics, translated by:

Faydouh, Y. (2009). The problem of translation in comparative literature. Amman, Jordan: Pages for Studies, and Publishing.

Flege, J. E., and Port, R. (1981). Cross-language phonetic interference: Arabic to English. Lang. Speech 24, 125–146. doi: 10.1177/002383098102400202

Na’al, M. (2003). Legal recognition of electronic signature in commercial transactions: a copparision between the Jordanian electronic transaction’s law of 2015 and the United Arab Emirates electronic transactions and trust services law of 2021. Int. J. Semiot. Law Rev. 36, 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11196-022-09967-6

Keywords: referential, gaps, Arabic, English, comparison

Citation: Alhendi N and Baniamer A (2024) Referential gaps between Arabic and English. Front. Educ. 9:1384130. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1384130

Edited by:

Haroon N. Alsager, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, Saudi ArabiaReviewed by:

Himdad Abdulqahhar Muhammad, Salahaddin University, IraqAbeer Asli-Badarneh, The Arab Academic College for Education in Israel, Haifa, Israel

Copyright © 2024 Alhendi and Baniamer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Noor Alhendi, bl9hbGhlbmRpQHlhaG9vLmNvbQ==

Noor Alhendi

Noor Alhendi Asem Baniamer

Asem Baniamer