- Department of Educational Planning and Management, College of Education and Behavioral Studies, Madda Walabu University, Bale Robe, Ethiopia

Introduction: Recently, women have been taking leadership positions in the hope of reducing gender inequality. However, it is unclear whether these female leaders have made a significant contribution to closing the gender gap. Guided by social role theory, this research explored the roles of female principals in reducing gender inequality in primary schools.

Methods: The study used a multisite case study design. Data were collected from 39 respondents: female directors, male and female students, and male and female teachers. Focus group discussions and interviews were the tools for gathering relevant data. The study utilized a six-staged thematic analysis approach with the help of NVivo 11 versions of qualitative analysis software.

Results: The study revealed that, besides being role models and counselors to female students, the role of female directors in minimizing gender inequality was insufficient due to the deeply entrenched traditional discrimination against women.

Discussion: Gender inequality in education stems from social roles, and female principals are assumed to help avoid or minimize gender disparity in a male-dominated world. However, achieving gender equality requires the collective efforts of parents, principals, society, and the government. Future quantitative or mixed-method research is important to determine the extent to which female principals have contributed to reducing gender inequality.

1 Introduction

Gender inequity is not merely a problem to be solved; it is a mechanism of oppression that permeates daily social interactions and reflects power imbalances, with men historically holding positions of authority that shape societal norms and institutions (Ernst, 2022). Throughout history, women have been systematically marginalized, relegated to secondary roles, and faced with undervaluation of their contributions and barriers to advancement (Dragana et al., 2021; Ware, 2010). Patriarchal structures perpetuate this inequality, resulting in a sex-based division of labor that is exacerbated by environmental influences and the passage of time (Karoui and Feki, 2018; Klasen, 2018). Cultural beliefs underpin this unequal system, fostering status disparities and resulting in the emergence of gendered features and prejudices within societal roles (Ridgeway, 2014; Wood and Eagly, 2012). Traditional gender roles, rooted in genetic variances, historically delineated women as caretakers and men as hunters, farmers, and leaders, perpetuating these norms and impacting individuals' ability to exhibit diverse characteristics (Eagly and Wood, 2012). Gender-based violence further reinforces this oppression, subjecting women to physical, emotional, and economic violence due to their gender, while socialization from childhood conditions girls to accept their subordinate status, perpetuating the cycle of inequity (Stanley and Devaney, 2017).

During socialization, individuals are conditioned to adhere to gender norms associated with their biological sex, perpetuating these stereotypes (Belingheri et al., 2021; Eagly and Wood, 2012). People's assumptions about gender characteristics further contribute to the development of prejudices when they encounter individuals in different societal positions (Belingheri et al., 2021; Wood and Eagly, 2012). Modern occupational categorization reinforces specialization, with agentic traits such as power and dominance associated with men and communal traits like kindness and caring linked with women (Koenig and Eagly, 2014; Wood and Eagly, 2012). Initial socialization to gender norms, observed in homes and media, perpetuates these norms, impacting individuals' ability to exhibit diverse characteristics (Schneider and Bos, 2019).

While the traditional gender-based division of labor has somewhat diminished due to women's higher education and reduced emphasis on physical strength (Koenig and Eagly, 2014), a modern division persists, with men occupying agentic positions like leadership and women filling communal roles like childcare (Blau et al., 2012). Even in male-dominated fields, women often gravitate toward disciplines emphasizing communal characteristics (Spector et al., 2014).

Despite women's increasing representation in administrative roles, men continue to dominate powerful organizational positions, perpetuating gender inequality (Groeneveld et al., 2020; Tabassum and Nayak, 2021; Wroblewski, 2019). Numerous studies explore the “glass ceilings” preventing women from reaching top roles, with the assumption that increasing female representation in management will mitigate workplace gender inequity (Smith et al., 2012; Tabassum and Nayak, 2021). Furthermore, gender biases may be reinforced by teachers favoring boys, interrupting girls, and holding different expectations for each sex in the classroom (Gunderson et al., 2012). Additionally, gender inequalities may stem from the differing games and activities engaged in by boys and girls, as well as the gender roles observed within families and communities (Tak and Catsambis, 2023). Efforts to narrow the gender gap in schools have seen women appointed to school headship roles (Guthridge et al., 2022).

However, research on the roles of female school heads or principals in reducing gender inequality within educational institutions remains limited. Existing studies primarily focus on gender issues in business organizations. For instance, Cohen and Huffman (2007) investigated the gender wage gap in their study “Working for a woman? Female managers and the gender wage gap,” finding that income inequality decreases with more women in management positions. Similarly, Abraham (2013) explored whether having women in power reduces gender inequality in organizations in their study “Does having women in positions of power reduce gender inequality in organizations? A direct test” and the study concluded that women managers mitigate wage disparities between genders, particularly for lower-level employees. However, these studies were conducted in developed nations and outside of the educational context, highlighting the unique contribution of this study in exploring gender equality within schools across different socio-economic and cultural settings.

Despite extensive research on gender-related issues in Ethiopia, such as women's empowerment in leadership positions (Molla and Cuthbert, 2014), women and development (Semela et al., 2019), and women's leadership styles (Mekasha, 2017), there is a lack of studies examining the roles of female principals in enhancing gender equality at the school level. This study aims to fill this gap by investigating how female principals, appointed by the government, contribute to reducing gender inequality in primary schools. It also evaluates the influence of educational leaders in shaping social dynamics and effecting positive social change within educational settings, assessing the alignment between theory and the practice of gender equality.

1.1 Theoretical perspective and research questions

Gender inequality is a pervasive and persistent problem in many societies, especially in developing countries like Ethiopia, where girls face multiple barriers and disadvantages in accessing and completing quality education (Kefale et al., 2021; Tekleselassie and Roach, 2021). Social role theory (SRT) suggests that gender roles are shaped by the division of labor between men and women in a given society, which in turn influences the development of gender stereotypes and expectations (Blau et al., 2012; Eagly and Wood, 2012). Traditionally, men's roles were related to hunting and laboring, which encouraged the emergence of agentic characteristics; women's roles, on the other hand, were related to caring for others, which fostered the creation of communal traits (Wood and Eagly, 2012). Despite societal shifts brought about by developments in post-industrialized nations and greater educational achievement for women, discrimination in employment persists, causing men and women to take on occupations that call for agentic and communal traits, respectively (Heymann et al., 2023; Kunz and Ludwig, 2022). Stemming from gendered roles in society, schools are also perpetuators of gender disparity (Eagly and Wood, 2012). Gender inequality in education not only violates the human rights of girls, but also hampers the social and economic development of the country (Iqbal et al., 2022; Girón and Kazemikhasragh, 2022). Therefore, it is imperative to understand and address the factors that contribute to or hinder the achievement of gender equality in education.

One of the factors that may influence the educational opportunities and outcomes of girls is the role of female leaders in the school system (Archard, 2013). Female leaders, such as principals, teachers, and gender club coordinators, may have the potential to challenge and change the traditional gender norms and stereotypes that limit girls' aspirations and achievements (Beaman et al., 2012). However, it is unclear how effective and influential these female leaders are in reducing gender inequality in their schools and communities.

To explore this issue, the study adopts SRT as a theoretical framework. SRT is a theory that explains the origins and consequences of gender differences and similarities in social behavior. SRT provides a useful lens to examine the role of female leaders in reducing gender inequality in education, as it helps to understand how gender roles are formed and maintained, how they affect the perceptions and behaviors of individuals and groups, and how they can be modified or challenged. SRT also helps to identify the factors that enable or constrain the female leaders in their leadership roles, such as the social and cultural context, the organizational structure, and the individual characteristics. Hence, the study tries to answer the following specific questions:

• How do principals, teachers, and students experience gender inequality in the primary schools of the Sheka zone?

• How do principals, teachers, and students perceive female directors' roles in battling gender inequality at primary schools in Sheka Zone?

• This study highlights the importance of revisiting gender equality concerns seriously for policy planners, as gender segregation is a deeply rooted social phenomenon. It is assumed that placing women in leadership positions will reduce gender inequality. However, this study sheds light on the difficulty of avoiding or minimizing gender inequality by female principals alone, and the urgency of revisiting the roles of parents, school principals, society, and government to address gender disparity in schools.

2 A literature review

2.1 Glass ceiling

As cited by Heijstra et al. (2017), Hymovitz and Schellhard published a scholarly work in the Wall Street Journal that emphasized the challenges women encounter when aspiring to attain top positions within organizations. They referred to a “glass ceiling” or “glass ceiling syndrome” (Cho et al., 2014), and the “glass ceiling phenomenon” (Hoobler et al., 2013). They suggest that women employees face more obstacles than men in the same capacity regarding their rights and have begun to appear more heavily in publications since the 1980s. The glass ceiling effect, regarded as a significant impediment in companies, can be overcome by quite a few women today (Acker, 2009; Glass and Cook, 2016). Glass ceilings are associated with women's access to management levels to obtain earnings and recognition. The glass ceiling effect can manifest itself in either leadership or lower-level roles at a worksite (Öztürk and Simşek, 2019).

Scholars were drawn to the difficulties women face in advancing their roles in the workplace. Women face a glass ceiling regarding access to organizational levels, earnings, and recognition (Glass and Cook, 2016). The glass ceiling refers to a hidden and insurmountable obstacle that prohibits women from advancing to the top of managerial, judgmental, or academic career paths, irrespective of their successes and capabilities in these careers (Jalalzai, 2008). Individual, organizational, and social interactions can all play roles in developing the glass ceiling phenomenon (Smith et al., 2012). Gender discrimination and unfairness can be examples of social factors (Jalalzai, 2008). Organizational factors, including company rules and culture (Öztürk and Simşek, 2019) perpetuate gender inequality. Time management could illustrate a personal element since wives and mothers are crucial roles that women play (Smith et al., 2012).

2.2 Overview of gender inequality in developing countries

Notably, developing nations are far behind developed countries in various ways. One of the a significant marker is gender equality (Paprotny, 2021). Accomplishing gender equality is anything but a simple undertaking since its prosperity depends on different variables, including the social, political, and financial activities of countries (Belingheri et al., 2021). While activities began in the mid-twentieth century, the issue of sexual orientation bias has received the consideration of many individuals since the 1995 Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing (Klasen, 2018).

Gender imbalance is one of the various difficulties facing non-industrial nations. Family, community, and culture distress women in developing countries. At the family level, women have less access to and command over resources (Zeng et al., 2014) and less influence over family decisions (Kemp and Zhao, 2016). Beyond the family, women have limited access to generating resources (Blattman et al., 2014), are under-represented in government decision-making bodies (Abraham, 2013), and frequently require freedom to advance their financial situation (Harner et al., 2017). Besides, monetary and social factors primarily suffocate women in developing countries (Zeng et al., 2014). As a result, efforts to reduce gender imbalance are required in various ways (Rammohan and Vu, 2018).

Gender equality has not been achieved in most countries, and the area is not doing well in achieving Education for All (Unterhalter et al., 2014). Given the circumstances, female students attending elementary schools in developing nations, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, are considered lower than boys (Grant and Behrman, 2010). Overall, gender bias is widespread in Africa, and perceiving this is a significant initial step. However, it is vital to recognize the causes of gender inequality through research and attempt to address them (Belingheri et al., 2021).

2.3 Gender inequality in education in Ethiopia: causes and consequences

Ethiopia has experienced notable economic growth and poverty reduction over the past decade, though challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic (Arega, 2020). The country has invested significantly in education, particularly in expanding access to primary education in rural and disadvantaged regions (MoE, 2016). However, persistent gender inequalities continue in education, with girls trailing behind boys in literacy, secondary and higher education enrollment, and learning outcomes (UNESCO, 2017). These disparities are unsurprising given Ethiopia's deeply rooted male-dominated culture and traditions that shape societal norms regarding the roles of women and girls (Tekleselassie and Roach, 2021; Woldegebriel and Mekonnen, 2023).

The available literature on gender inequality in Ethiopia can be categorized into cultural, familial, and educational factors. First, cultural norms restrict girls' access to education due to historical discrimination and violence against women at both community and peer levels (Kassa and Abajobir, 2020; Kedir and Admasachew, 2010). Practices like female genital mutilation (Fite et al., 2020; Setegn et al., 2016), early marriage (Erulkar, 2013), and sexual violence (Kefale et al., 2021; Le Mat, 2016) are prevalent. Women's roles have traditionally been confined to the domestic sphere, leaving a lasting impact on future generations (Webster-Kogen, 2013). Rural and impoverished girls face additional challenges, such as household chores, hindering their educational potential (Camfield and Tafere, 2011; Cuesta, 2018). Changing these norms requires legislative efforts and time (Gretland et al., 2014).

Second, parents in rural and impoverished areas negatively impact girls' education, particularly compared to boys' (Hailu, 2019). They rely on child labor for household income, assigning more work to girls than boys (Cuesta, 2018). This results in girls arriving late, feeling fatigued, and having less study time at school (Hailu, 2019). Additionally, families often struggle to afford education-related costs, such as supplies, uniforms, and shoes (Gretland et al., 2014). Parents tend to prioritize sending boys to school over girls, widening the educational gap (Gretland et al., 2014).

Third, educational factors also hinder female education in Ethiopia, beginning with low expectations for girls, especially in primary education (Hailu, 2019). Textbooks and media reinforce gender stereotypes, confining girls to domestic roles, while the absence of female educators limits access to mentors and role models (Tekleselassie and Roach, 2021). These factors, coupled with household and cultural pressures, contribute to lower academic achievement for girls (Cárcamo et al., 2021). Women also score lower on exams than men (Tirussew et al., 2018) and encounter gender bias in assessments for secondary and higher education. Another obstacle is the distance to schools, as girls must travel long distances to reach secondary schools in rural areas. This leads to tardiness and exposes them to safety risks like rape and abduction, jeopardizing their education (Hailu, 2019).

2.4 School-related factors that perpetuate gender bias

Numerous school-related factors perpetuate gender bias. Some of these include inadequate schools, teachers, textbooks, and other educational resources; insufficient focus on the unique needs of girls; the lack of an educational plan to promote gender equality; and inappropriate behavior within schools (Belingheri et al., 2021). Besides, factors that perpetuate gender inequality include the absence of education role models at various levels, academic help, a lack of propelled educators, and an absence of girls' well-disposed school conditions (Baten et al., 2021). Aware of this impact, the public authorities of Ethiopia have gone to different lengths to address the gender inequality issue in the country. The government has enshrined this in the existing education and training policy of 1994. Additionally, girls' education was supported by numerous government strategies, such as the National Girl's Education Strategy, the Ethiopian Women's Empowerment Package, etc.

2.5 The school administrators' role in promoting gender equality

Schools are one of the social foundations where gender imbalance is generally predominant. As a result, those in positions of authority in schools must take the situation seriously and attempt to devise and implement various solutions to the problem (Bertocchi and Bozzano, 2019). Following this, scholars such as Karlsson and Simonsson (2008) presented the accompanying significant systems that managers and teachers in primary and secondary schools can use to advance gender fairness in schools: making a sex-evenhanded school culture by handling gender imbalances (Bertocchi and Bozzano, 2019), applying the high achievement assumption to all people (Karlsson and Simonsson, 2008), using a wide variety of strategies as a vehicle for documenting and challenging gender segregation (Bertocchi and Bozzano, 2019), and providing well-targeted assistance for those in need (Karlsson and Simonsson, 2008).

The role of men and parents in reconciling women's private and professional lives is now the focus of European Union regulations (Scambor et al., 2014). Concerning the school principals' jobs, scholars do not appear to have settled on whether a male or female is the most viable candidate to address sexual orientation-related issues in schools. The current standard and conviction are that female principals are more worried than males. Late exploration (Blunch and Das, 2015) contradicts recent belief, and discoveries keep showing no massive contrast between males and females, intending to cause gender gap awkwardness. Mutuality and collaboration among diverse stakeholders are crucial, so both genders are the most effective methods of promoting equality between the genders (Scambor et al., 2014).

3 Materials and methods

The multisite case study design helped the researcher explore the lived experiences of respondents about women leaders' contributions to lessening gender bias in an academic environment (Tomaszewski et al., 2020). The researcher selected a multisite qualitative case study for three compelling reasons. First, the design helps to study the phenomenon in different settings, researchers can identify common themes and patterns that may extend beyond the specific cases studied (Jenkins et al., 2018). Second, the design allows one to draw attention to patterns and discrepancies while establishing a thorough description of every situation (Tomaszewski et al., 2020). Finally, the design allows for direct comparison but emphasize description, discovery, and theory building (Tomaszewski et al., 2020). The study was accomplished by exploring how respondents felt about the role of female school heads in reducing gender inequality in primary schools (Jenkins et al., 2018).

3.1 Sampling

The Sheka zone in the newly emerged Southwestern People's Region serves as a distinctive backdrop for examining social role theory principles within the educational system. Despite having 95 primary schools, only 13 are led by female principals, prompting purposeful sampling aligned with social role theory. This targeted approach focuses on the 13 female-led primary schools, seeking to capture the unique perspectives and roles of female principals, harmonizing with social role theory principles.

In tandem, the study recruits 13 experienced and newly deployed teachers, utilizing a snowball sampling technique to address challenges in identifying assertive teachers, aligning with social role theory's recognition of varied teacher roles shaped by authority figures. Similarly, the recruitment of seven male and six female students from all selected schools using a snowball sampling technique reflects social role theory principles, recognizing students' social dynamics and their ability to express ideas.

Principals nominated key informants, ensuring representation from each school and acknowledging students as vital contributors. The study engages one female school head, one female or male teacher, and one male or female student in each school, mirroring social role theory's emphasis on recognizing diverse roles within each educational setting. The multisite case study design, coupled with the decision to generalize findings (Benzer et al., 2013), aligns with social role theory by acknowledging context-specific role variations in different educational settings. This comprehensive approach integrates sampling techniques that capture the nuanced roles of female principals, teachers, and students within the Sheka zone's educational context, contributing to a holistic understanding informed by social role theory principles.

3.2 Data collection

In this study, the researcher used both interviews and focus group discussions for complementary purposes. In this integrated approach, interviews provide detailed individual insights, while FGDs capture broader group dynamics and diverse perspectives, both essential for a comprehensive understanding of the roles and challenges faced by female principals in addressing gender inequality in schools.

3.2.1 Interview

The study conducted interviews with 13 female principals tasked with minimizing gender gaps. The choice of female principals for interviews was deliberate, considering their busy schedules and limited availability for participating in focus group discussions. Consequently, the researcher interviewed them at their convenience. The interview guide, designed for flexibility, facilitated the detection of respondents' non-verbal behaviors and yielded a higher response rate compared to a questionnaire (Audet and d'Amboise, 2001). Interviews were also instrumental in probing respondents' responses (Jiménez and Orozco, 2021).

The content of the interviews delved into various aspects, including how gender inequality manifests in the school system, the government's support for female principals to enhance their effectiveness, how female principals address gender equality issues, and the acceptance of their role by society and the school community. To ensure the robustness of the interview protocol, three experts from Addis Ababa University in the fields of education and psychology were invited to provide feedback, and their concerns were duly considered.

The interviews were conducted in the Amharic language, the official language of Ethiopia, as both the researcher and respondents communicated more effectively in Amharic than in English. To bridge any language gaps, two language experts were enlisted to translate the English version of the interview guide to Amharic and vice versa. The interview sessions took place between December 10, 2019, and December 30, 2019, with an average duration of 40 min per session. The researcher obtained permission from each participant before recording the interview responses.

3.2.2 Focus group discussion

The study conducted focus group discussions (FGDs) with 13 male and female students and 13 male and female teachers, as the interaction of these respondents provided an in-depth understanding of the roles of female principals. Regarding the number of FGDs, there are no specific requirements, but it can be determined by the research objectives and available resources (Rabiee, 2004). Hennink et al. (2019) suggest using 6–10 participants in one group, as this size is large enough to promote diverse perspectives and small enough for effective group dynamics. Following these recommendations, the 13 students were divided into two groups, with one group having six members and the other group having seven members. The same grouping approach was applied to the teachers' groups.

Focus groups can illuminate disparities in viewpoints across various groups and reveal a variety of opinions and feelings about specific topics (Rabiee, 2004). FGDs are cost-effective and data-rich, stimulating participants and assisting them in recalling significant incidents, allowing for a more comprehensive exploration than the responses of a single individual interviewed (Scheelbeek et al., 2020). However, FGDs have limitations when one individual acts as an interviewer and note-taker throughout interviews (Scheelbeek et al., 2020). To address this drawback, the researcher recruited an expert to record the group interview responses without additional responsibility for the entire FGD.

To prevent data loss, the sessions were recorded with permission from all group interviewees. The researcher served as the facilitator, prepared structured discussion guides, and managed the group interviews. The FGDs comprised four sessions: two group interviews for teachers and two for students. The topics of discussion included how gender inequality manifests in the school system, how the government supports female principals to enhance their effectiveness, how the society and school community accept their role as principals, and how female principals mitigate gender equality problems.

Like the interviews, the researcher employed Amharic as the medium of discussion, and language experts performed forward and backward translations from Amharic to English and vice versa. The FGDs were conducted from January 5, 2020, to January 30, 2020, with an average duration of 2 h.

The methodological rigor was assured by the following mechanisms: first, the data was gathered from different groups of people (female principals, teachers, and students). Second, data was gathered using different research methods (interviews and focus group discussions). Finally, after transcribing the data, the researcher provided the transcriptions to female principals and teachers to see if the transcriptions matched their responses. Therefore, the researcher's job was to describe each participant's viewpoint with as much detail and honesty as he could.

3.3 Data analysis

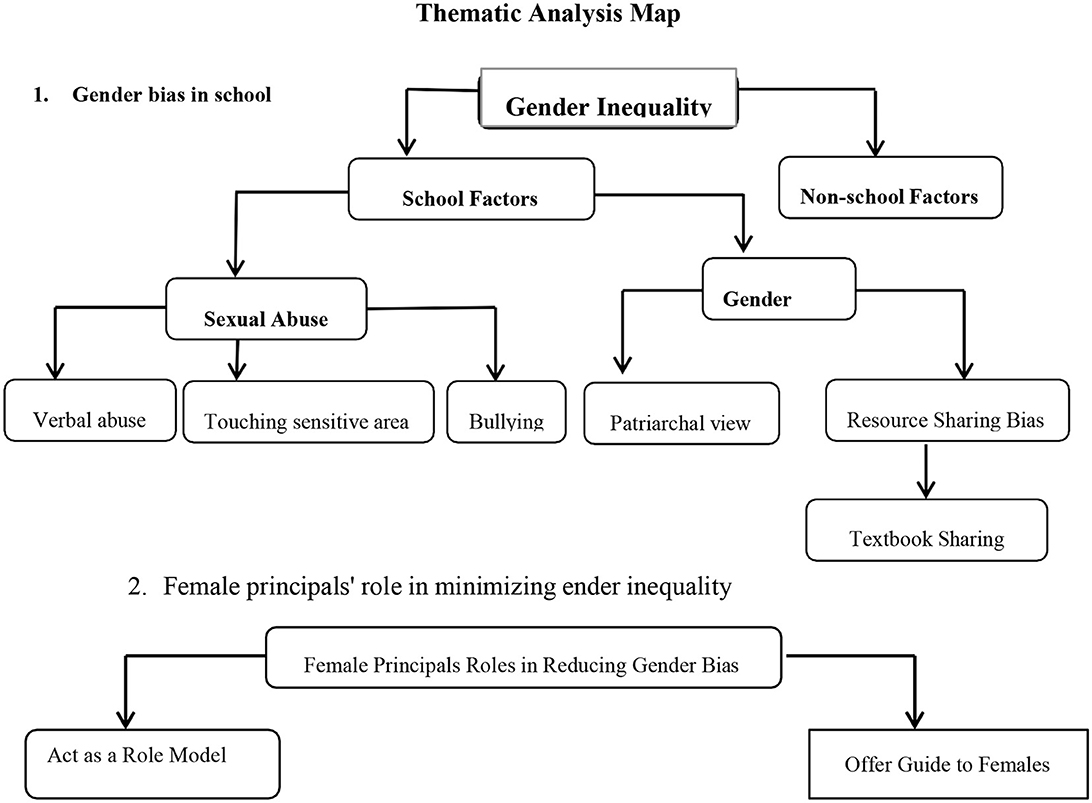

The qualitative analysis software known as NVivo 11 was used in this study. The data analysis was divided into six stages (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Firstly, two linguistic scholars converted the transcribed Amharic version into English and handed over 150 pages. The interview transcripts were loaded into the NVivo 11 application in the second phase, and 400 codes emerged. After listening to the recording and rereading the transcription in step three, these 400 codes emerged as 18 themes with 12 themes with gender inequality in schools and 6 themes with women's roles as principals. Fourth, the researcher identified themes and sub-themes, and different themes with similar ideas developed. Stage five involved differentiating every theme's nature, recognizing the themes' cruxes, and defining the type of data every theme apprehended. This stage, which Braun and Clarke (2006) refer to as a subsequent refining stage, is where various themes are explored to determine the stories that each informs. When refining, the study examined how each theme fit with the overall goals of the research and how the information supported the research questions. The refinement process was created to reduce excessive theme crossover. Consequently, two major themes were found: sexual abuse and teacher gender bias for the first research question, and acting as a role model and offering guidance for the second question. In stage six, the researcher used direct quotations to support the themes in the reports. For details, please refer to the thematic analysis map presented in Figure 1 below.

The researcher identifies interviewees and discussants by using groups of respondents' initial letters (“P” for female principal, “MT” for male teacher, “FT” for female teacher, “MS” for male students, and “FS” for female student), along with consecutive numbers to locate everyone to enhance the confidentiality and anonymity of the informants in the study.

3.4 Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The research was approved by the Sheka Zone Education Bureau and by the principal of each participating school. Written informed consent for participation in the study was obtained from the participants.

4 Findings

The responses gathered from both interviews and focus group discussions underscore that gender equality in education faces obstacles arising from factors within schools as well as those external to the school environment. However, this study specifically centers on presenting school-related factors. The researcher has categorized these factors into two overarching themes: gender bias in school practices and sexual abuse. Moreover, the theme elucidating the role of female principals in mitigating gender inequality is presented after the sexual abuse theme. Consequently, the subsequent section offers a detailed explanation of each theme.

4.1 Gender bias in school practices

Female students have observed a prevalent inclination among most teachers, including females, toward boys, perceiving them as more intelligent than their female counterparts. According to these sources, teachers hold the belief that female students rely on their male counterparts for academic support. Discussant FS#3 expressed disbelief, stating, “I am always amazed at our teachers' opinions because when they enter the classroom, they often ask male students to remind them where they left off from yesterday's lesson.”

In line with social role theory, discussants highlight the manifestation of gender bias in education, emphasizing how teachers consistently assign leadership roles to boys, thereby perpetuating traditional gendered roles within the classroom dynamics. For instance, Discussant FS#10 asserted, “The bias against female students becomes more apparent when teachers consistently assign boys to lead group activities, reserving only 5%−7% of leadership roles for female students.” Female students also reported that teachers generally favor male students, reacting differently when boys and girls answer questions. Discussant FS#1 noted, “Teachers use expressions like tremendous or superb when boys correctly answer questions. Conversely, females' responses lead the teachers to be perplexed.” Social role theory contributes to understanding how deeply rooted societal beliefs about gender roles impact the educational environment, perpetuating biases that female students encounter. Based on female students' experiences, the researcher foresees a challenging future for improving the education system in the country.

Male students' responses affirmed the existence of gender bias related to textbook utilization. Discussant MS#7 stated, “Homeroom teachers form groups of male and female students due to a shortage of books. However, male students consistently use the books and hand them over to female students at the 11th hour when assignment deadlines approach.” Female principals acknowledged the lack of textbooks and the resultant grouping, but they do not recognize that such practices foster gender bias. Female teachers argued that mixing males and females in one group is unfair, reflecting societal beliefs in gender inequality. Male students, influenced by societal norms, replicate this behavior due to the prevalent male dominance over resources.

Gender bias persists in examination and assignment results as well. Discussant MS#13 argued, “When female students score high in an examination, teachers question if she copied from a male student.” Male teachers confirmed this perception, with one stating, “Since female students have limited time to study due to household responsibilities, doubts arise when a female student excels in examinations” (Discussant MT#5). Even female teachers expressed skepticism about the capabilities of female students. One of them remarked, “In my experience, female students often cheat in exams, and when a female student scores high, I am amazed by her performance” (Discussant FT#8).

Female principals' reactions to these challenges aligned somewhat with other groups' responses. Teachers' undermining of female students' efforts perpetuate traditional gendered phenomena. Interviewee P#9 emphasized, “Nobody should deny the prevalence of teacher bias in schools, although the seriousness of the issue varies from department to department.” This suggests that gender discrimination is rooted in society and deeply embedded in the school community. While female principals are tasked with minimizing gender bias, the lack of awareness about the importance of female students' education among families, society, and teachers poses a significant challenge.

4.2 Sexual harassment

Various factors impact the academic achievement of female students, with sexual harassment playing a predominant role. Within the school compound, male teachers and boys engage in practices of sexual harassment, manifested through verbal abuse and intimidation directed at female students. The involvement of teachers in such behaviors is deemed disreputable and indecent by female students. Discussant S#6 revealed, “Some teachers use inappropriate language with females, encouraging sexual advances and touching sensitive areas like breasts. I am ashamed of such teachers as they forget the ethical standards of their profession.”

Another distressing aspect is the accusation by female students that boys contribute to their low academic achievements. Discussant S#4 stated, “In grades 7 and 8, male students often pressure female students for sexual intercourse. When females refuse, the consequence is public insult and sometimes bullying by male students in front of their peers.”

Male students, influenced by societal expectations, acknowledge the prevalence of sexual harassment, with Discussant MS#3 explained, “Verbal abuse is common in our school; I grew up in a society that believes beautiful girls should be verbally abused and groomed for future wives.” This reflects the impact of social role theory on normalizing abusive behavior toward females. Similarly, male teachers contribute to the discourse, with Discussant MT#10 admitted, “Some teachers also engage in sexual assault when there are no eyewitnesses,” revealing power dynamics influenced by societal norms. The affirmation of the issue's gravity by female teachers, as expressed by Discussant FT#4, underscores social role theory, emphasizing deeply ingrained gender roles victimizing females in various educational roles and the need for a comprehensive approach to foster a safe educational space.

Many female teachers revealed that they often receive harassment complaints from female students. The researcher sought to understand if reports of sexual assault increased during the tenure of female principals compared to male principals. Most female teachers confirmed that female students feel more comfortable reporting assault cases to female principals. Discussant FT#13 stated, “In my seven years at this school, reports of sexual assault were fewer when male principals held positions compared to when women were in charge.” Female teachers explained that female students trust female principals more and report harassment freely, even if there are no human witnesses.

Despite this positive contribution of female principals, the difficulty in combating sexual harassment is emphasized. Female teachers reported incidents of male teachers and boys assaulting female students to female principals, but the progress in minimizing harassment remains insufficient. Discussant FT#9 asserted, “While we discuss sexual assault issues in staff meetings, our efforts have not brought improvement in minimizing sexual harassment.”

Female principals also acknowledged the prevalence of sexual harassment faced by female students within school settings. Directors receive 5–10 grievances related to female sexual harassment per week. When asked about measures taken to reduce sexual harassment, most female principals highlighted the challenges in combatting such behavior. Interviewee P#7 noted, “Male teachers and boys often bully female students in secluded areas, making it difficult for victims to have witnesses. Accusing teachers and boys becomes challenging due to the lack of human witnesses.”

The respondents acknowledged that reporting of sexual assault cases has increased since female principals assumed positions, reflecting a positive change. However, eliminating sexual harassment at the school level remains challenging due to its deep-rooted nature in society. Male teachers and boys often target female students away from witnesses, and the lack of CCTV cameras in schools, compounded by societal constraints, hinders the disclosure of such hidden issues. Ethiopian law requires three eyewitnesses to accuse an individual, making it difficult to hold perpetrators accountable. The educational environment for females appears inhospitable as both teachers and students contribute to unethical behaviors initiated against the students.

4.3 Female principals' role in minimizing gender imbalances

In discerning the role of female principals in mitigating gender bias, respondents' insights were categorized into two themes: acting as role models and providing guidance and counseling for female teachers and students. The details of these themes are presented as follows.

4.3.1 Female principals as role models

Most female directors contend that the appointment of female principals has significantly contributed to addressing gender disparities. Interviewee P#12 noted, “Since assuming an administrative role, female teachers have admired me and sought insights into how I navigated traditionally assigned male roles. Moreover, I have observed that female teachers have been inspired to take on leadership roles in primary schools.”

Similarly, another interviewee, P#11, stated, “Female teachers often approach my office seeking advice on effectively managing schools. They request recommendations for books that have guided me in efficient school management.” Additional female principals shared that women inquire about training opportunities for female teachers aspiring to lead schools, inspired by the presence of women in top positions. Overall, directors emphasized that their ascent to leadership positions has positively influenced gender imbalances in schools.

Female students echoed the importance of having female principals in top positions. Discussant FS#5 asserted, “While walking to school, I frequently hear comments from people suggesting that I, as a girl, cannot contribute significantly to society. Nevertheless, witnessing women in top positions encourages me to pursue my education. A female principal serves as my role model.” Other female students expressed similar sentiments, with one sharing her experience. Discussant FS#1 stated, “Male students discourage me from continuing my education, claiming I am old enough to marry and bear children. I consistently assert my importance to society's development, with female principals serving as my references during these arguments.” Male students also acknowledged the role of female principals as role models. Discussant MS#2 stated, “Female principals undoubtedly serve as role models for girls, having overcome various obstacles to reach their positions.”

Both male and female teachers recognized the significant impact of female school heads as role models, illustrating the role of social role theory in reshaping perceptions of gendered roles in educational leadership. Discussant FT#6 acknowledged the commitment of female principals and highlights, “In a society with gendered roles, women are assigned the role of school head. Despite societal attitudes, she leads the school. Inspired by her example, I aspire to become a school leader.” This statement reflects how social role theory contributes to understanding the transformative influence of female leaders breaking societal norms. Male teachers affirm the role-model status of female principals, emphasizing the necessity of competent female leaders to challenge traditional stereotypes of gendered roles. Social role theory underscores the importance of competent appointments to address the gender gap effectively, preventing inadvertent reinforcement of traditional gendered roles that perpetuate exclusive leadership positions for males.

4.3.2 Providing guidance and counseling to women

Female principals offer valuable advice to female students, acting as mentors and providing solutions to various challenges. Female teachers and students shared their experiences, with some male teachers adhering to traditional gender norms.

One female teacher acknowledged female principals as older sisters, seeking their guidance on personal and professional matters. Discussant FT#12 stated, “When facing challenges in my life and job, I consult my principal for solutions, viewing her as a source of guidance.” Another female teacher attested to the supportive interactions during tea breaks, appreciating the female principal's perspectives that aided in problem-solving. However, male teachers tend to consult their male colleagues due to ingrained gender norms.

Female students also seek guidance from female principals, especially during significant life events. Discussant FS#4 argued, “When I experienced the initial menstruation, I was disturbed and cried, and I approached the principal and told her what happened to me, and the director told me that the situation was normal, and she guided me to feel free.” Another female student appreciated her principal's support and emphasized how a female perspective can relate to menstrual issues.

Conversely, some female students expressed dissatisfaction, perceiving the female principal's appointment as exacerbating their concerns. One student cited instances of inappropriate language as follows “Female students, burdened by home responsibilities, arrive late.” The female principal, noticing a student, employs harsh discipline and uses inappropriate language, undermining female student's worth, saying, “You are useless” (discussant FS#12).

While female principals exhibited strength in enforcing rules, the criticism points to unmet expectations. Respondents desire additional efforts from female principals in addressing gender inequality, expecting measures like tutorial classes and discussions on sexual harassment to be consistently implemented. However, the challenges arise from the multiple roles female principals navigate, including political involvement, leading to unmet expectations and dissatisfaction among teachers and students.

The discussion on unmet expectations led the researcher to probe further. Some respondents suggested that political obligations and the political nomination process contribute to female principals prioritizing political matters over educational responsibilities. The perception that political connections influence appointments that leads to less competent individuals occupying leadership positions.

High expectations persist among female students, reflecting a desire for female principals to address various issues. However, the challenging nature of reducing gender inequality is attributed to the prioritization of political matters in a predominantly male-dominated realm. In summary, while female principals play crucial roles as mentors and counselors, the unmet expectations stem from political obligations, less competent appointments, and the challenging environment of working in a male-dominated political landscape.

5 Discussions

This study's findings, revealing teachers' gender biases favoring male students and undermining female students' exceptional performances, align with social role theory. The notion of women's predisposition to underperform in the classroom reflects societal expectations, in line with Adeosun and Owolabi (2021). Cognitive science results, emphasizing the influence of early self-concept formation and post-primary school norms, resonate with the theory (Levorsen et al., 2023). This is consistent with cognitive dissonance theory (Jouini et al., 2018), as individuals facing stereotyping may lack confidence and underperform. Despite evidence that educating women is more valuable (Patrinos and Psacharopoulos, 2020), societal expectations persist, reinforcing traditional gender roles.

The study also found that sexual harassment is a severe problem that hinders female students' academic achievements. Male teachers and students harass female students. When female students deny their male counterparts' proposals, they will be insulted or bullied in front of their friends. This finding resonates with Mekonnen and Wubneh (2022) findings. They examined the aggregate incidence of sexual misconduct among female students in Ethiopia using an extensive review and meta-analysis. They discovered that around half of Ethiopia's female pupils had been victims of sexual assault. Additionally, the findings of these scholars (Worke et al., 2020) align with this discovery, indicating that sexual harassment is prevalent in their respective study regions.

However, many schools struggle with inadequate and poorly enforced policies on sexual misconduct, exacerbating the issue. Reporting mechanisms are often lacking, and clear procedures for handling complaints are not in place. Students and staff frequently do not know how to report incidents, leading to a culture of silence and fear of retaliation. Without proper education on recognizing, preventing, and responding to sexual abuse, the school community remains at risk. Teachers and administrators may not be sufficiently trained to handle disclosures of abuse or provide appropriate support to victims. Additionally, enforcement of existing policies is often weak. Even when policies exist, there may be a lack of accountability and follow-through, fostering a culture of impunity. This failure to enforce consequences can discourage victims from coming forward, knowing that their complaints may not result in meaningful action.

One serious problem with sexual assault in the study area was that female students claimed the behavior but had no human witnesses, and it is impossible to accuse a man without eyewitnesses. The school environment in emerging regions is completely different from developed ones that have installed cameras everywhere. Hence, the only option is eyewitnesses, but the harassers do not commit such unwanted behavior in front of other people. Hence, scholars such as Gerke et al. (2023), Gruber and Fineran (2016), and Morais et al. (2018) condemned the fact that sexual assault has more adverse effects on learning outcomes because it more strongly arouses sexist and heterosexist stereotypes, lowers pupil participation in school, and isolates pupils from instructors.

The literature highlighting the potential of female leaders to alleviate workplace gender imbalances aligns with social role theory. Studies propose that women in leadership diminish the significance of gender identity, reducing discrimination (Blau et al., 2012; Glass and Cook, 2016). However, this study reveals the nascent stage of female school principals' role in reducing gender inequality. Political affiliations determine leadership in Ethiopian schools (Aklilu et al., 2021), leading to a lack of education management expertise (Aklilu, 2022). The appointment of principals before leadership training and inadequacies in the training's breadth and depth further hinder their impact (Gurmu, 2020). This underscores the need to revisit assumptions in nominations, advocating for competitive female leaders in education. Additionally, female principals face obstacles like work-life balance (Smidt et al., 2017), fear factors (Tomàs et al., 2010), insufficient support (Diehl, 2014), and social stigma (Maheshwari et al., 2023), as documented in global literature. As these factors are widely stated in the literature and prevalent throughout the globe, Ethiopia is not free from the stated obstacles for female principals' effectiveness in discharging their responsibilities. Understanding and addressing these factors are crucial for enhancing the effectiveness of female principals, aligning with social role theory's emphasis on societal expectations and roles.

The study revealed that female principals act as role models for female students because education in Ethiopia is male-dominated. Out of active teachers at primary schools (grades 1–8), only 40% are female teachers (MoE, 2021). Comparing the homogeneous leadership styles of male and female leaders in higher education, coworkers, colleagues, and students seem more likely to have favorable fundamental experiences with female leaders (Madsen, 2012). According to an investigation into Latin American Hispanic women leaders in school, these women identified as role models as a part of their culture. Most participants acknowledged having some sense of obligation to serve as a good example (Montas-Hunter, 2012). The findings underscore the importance of involving many competent females in leadership positions, which neutralizes gender-socialized roles such as caring for entire families and house chore activities because girls and female teachers began to think about the possibility of managing a large organization traditionally assigned to men.

6 Conclusions

The study highlights the pervasive nature of gender inequality in the primary schools of the Sheka zone, deeply rooted in societal expectations and traditional gender roles. Teachers' gender biases favor male students, undermining the achievements of female students, while female students face significant challenges such as sexual harassment, which severely impacts their academic success. The lack of comprehensive policies and reporting mechanisms exacerbates these issues, creating a hostile environment for female students.

Additionally, the study underscores the crucial yet underutilized role of female school principals in combating gender inequality. Despite their potential to reduce gender imbalances and serve as role models, female principals face numerous obstacles, including political influences on appointments, work-life balance challenges, insufficient support, fear of failure, and societal stigma. These barriers limit their effectiveness in addressing gender inequality. To enhance their impact, there is a need for greater support, training, and a shift in societal attitudes toward women in leadership roles.

7 Implication of the study

Female principals contribute to minimizing gender inequality in school settings by being role models and counselors for female students. However, there are issues that cannot be solved by female or male principals, such as gendered roles in the society that manifest in school settings, sexual assault in the absence of eyewitnesses, and the security of female principals if they take measures on disciplinary issues. In a society that believes smart girls should be verbally abused and groomed for future wives, what can women principals do in an insecure environment? Therefore, to minimize gender inequality in schools, potential stakeholders such as female principals, parents, society, and government should take their responsibilities. The study has implications for the stated stakeholders as follows.

7.1 Implication for female principals

This study highlights the challenges female principals face in addressing gender biases and fostering a favorable educational environment. Persistent biases among teachers influence students' self-concepts, requiring female principals to confront these ingrained issues, including the pervasive problem of sexual harassment. To ensure a safe and secure environment for students, schools must implement comprehensive measures against sexual abuse, such as establishing clear policies, mandatory training, and accessible reporting mechanisms. Empowering female leadership is crucial for reducing gender inequality and advocating for protective measures. Overcoming obstacles like work-life balance, social stigma, and political affiliations is essential for female principals to effectively serve as role models, challenge gender-socialized roles, and cultivate a positive school culture that supports all students. Additionally, engaging the broader community to reinforce these efforts is vital in creating a supportive and inclusive educational environment.

7.2 Implication for parents

Parents are key agents in creating a more fair and inclusive education system. They can challenge gender biases, celebrate both male and female achievements, and encourage their children to pursue academic excellence and support each other. They can also communicate openly about sexual harassment, educate their children on respect and consent, and empower them to speak out. Moreover, they can support their daughters' leadership ambitions, advocate for female school principals' training, and challenge work-life balance issues and gender stereotypes. Thus, parents can foster a culture of effective female leadership and gender equality in education.

7.3 Implications for society

Society should confront gender bias in education by changing norms and policies that sustain it. This involves advocating for equal opportunities, anti-harassment measures, and safe reporting systems for all students. Society should also reform leadership appointments to prioritize competency and diversity, and support female leaders in education by challenging stereotypes, addressing obstacles, and fostering inclusivity. This would enhance leadership effectiveness and diversity, and provide diverse role models for students and educators.

7.4 Implication for government

The study shows the government's challenges in transforming education. A strategic approach is needed to address gender biases in education. Educators should be trained to raise awareness of biases and ensure equal opportunities for all students. The government should also fight sexual harassment in schools by enforcing policies, reporting systems, and security measures. Moreover, the government should reform leadership appointments to prioritize competency and diversity, and support female leaders in education by addressing their challenges, enhancing their training, and promoting their representation. These steps are essential for creating a more fair and effective education system.

Future research is crucial in proving or disproving this study's findings because the research region for this study was only one zone with 39 respondents. It is also recommendable to conduct a quantitative survey that involves various samples and research regions and leads to the generalization of female principals' roles in minimizing gender inequality in Ethiopian educational contexts.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The research was approved by the Sheka Zone Education Bureau and by the principal of each participating school. Written informed consent for participation in the study was obtained from the participants.

Author contributions

AA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abraham, M. L. B. (2013). Does having women in positions of power reduce gender inequality in organizations? A direct test. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Acker, J. (2009). From glass ceiling to inequality regimes. Sociol. Trav. 51, 199–217. doi: 10.1016/J.SOCTRA.2009.03.004

Adeosun, O. T., and Owolabi, K. E. (2021). Gender inequality: determinants and outcomes in Nigeria. J. Bus. Socio-economic Dev. 1, 165–181. doi: 10.1108/jbsed-01-2021-0007

Aklilu, A. (2022). Experts' perception of secondary education quality management challenges in Ethiopia. Educ. Plan. 29, 35–50. Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1344730

Aklilu, A. A., Dabi, K., and Chan, T. C. (2021). Stakeholders' perception of political influences on quality management of secondary education in Ethiopia. Educ. Plan. 28, 35–53. Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1284818

Archard, N. (2013). Women's participation as leaders in society: an adolescent girls' perspective. J. Youth Stud. 16, 759–775. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2012.756974

Arega, M. (2020). The impact of human capital on economic growth in Ethiopia: evidence from time series analysis. Stud. Humanit. Educ. 1, 51–73. doi: 10.48185/she. v1i1.95

Audet, J., and d'Amboise, G. (2001). The multi-site study: an innovative research methodology. Qual. Rep. 6, 1–18. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2001.2001

Baten, J., de Haas, M., Kempter, E., and Meier zu Selhausen, F. (2021). Educational gender inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa: a long-term perspective. Popul. Dev. Rev. 47, 813–849. doi: 10.1111/padr.12430

Beaman L. Duflo E. Pande R. and, Topalova, P. (2012). Female leadership raises aspirations and educational attainment for girls: a policy experiment in India. Science 335, 582–586. doi: 10.1126/science.1212382

Belingheri, P., Chiarello, F., F. Colladon, A., and Rovelliid, P. (2021). Twenty years of gender equality research: a scoping review based on a new semantic indicator. PLoS ONE 16:e0256474. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256474

Benzer, J. K., Beehler, S., Cramer, I. E., Mohr, D. C., Charns, M. P., and Burgess, J. F. (2013). Between and within-site variation in qualitative implementation research. Implement. Sci. 8, 1–14. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-4

Bertocchi, G., and Bozzano, M. (2019). Gender Gaps in Education. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 1–31.

Blattman, C., Fiala, N., and Martinez, S. (2014). Generating skilled self-employment in developing countries. Q. J. Econ. 129, 697–752. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjt057.Advance

Blau, F. D., Brummund, P., and Liu, A. Y. H. (2012). Trends in occupational segregation by gender 1970-2009: Adjusting for the impact of changes in the occupational coding system. Massachusetts. Available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w17993 (accessed February 22, 2022).

Blunch, N. H., and Das, M. B. (2015). Changing norms about gender inequality in education: evidence from Bangladesh. Demogr. Res. 32, 183–218. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2015.32.6

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Applied qualitative research in psychology. Appl. Qual. Res.Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1057/978-1-137-35913-1

Camfield, L., and Tafere, Y. (2011). Community understandings of childhood transitions in Ethiopia: different for girls? Child. Geogr. 9, 247–262. doi: 10.1080/14733285.2011.562385

Cárcamo, C., Moreno, A., and del Barrio, C. (2021). Girls do not sweat: the development of gender stereotypes in physical education in primary school. Hum. Arenas 4, 196–217. doi: 10.1007/s42087-020-00118-6

Cho, J., Lee, T., and Jung, H. (2014). Glass ceiling in a stratified labor market: evidence from Korea. J. Jpn. Int. Econ. 32, 56–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jjie.2014.01.003

Cohen, P. N., and Huffman, M. L. (2007). Working for the woman? Female managers and the gender wage gap. Am. Sociol. Rev. 72, 681–704. doi: 10.1177/000312240707200502

Cuesta, A. (2018). Child work and academic achievement: Evidence from Young Lives in Ethiopia. Univ. Minnesota. Available at: http://www.younglives.org.uk/ (accessed September 5, 2022).

Diehl, A. B. (2014). Meaning of barriers and adversity: experiences of women leaders in higher education. Adv. Women Leadersh. 34, 54–63. doi: 10.21423/awlj-v34.a118

Dragana, S., Stephanie, S, and Beate, V. (2021). The gender gap in workplace authority: variation across types of authority positions. Soc. Forces 100, 599–621. doi: 10.1093/sf/soab007

Eagly, A. H., and Wood, W. (2012). “Social role theory,” in The Wiley Blackwell encyclopedia of gender and sexuality studies, ed. N. A. Naples (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons), 458–476.

Ernst, S. (2022). “Hidden gender orders: socio-historical dynamics of power and inequality between the sexes,” in The Palgrave Handbook of the History of Human Sciences, ed. D. McCallum (Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan), 749–773. doi: 10.1007/978-981-16-7255-2_52

Erulkar, A. (2013). Early marriage, marital relations and intimate partner violence in Ethiopia. Int. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 39, 6–13. doi: 10.1363/3900613

Fite, R. O., Hanfore, L. K., Lake, E. A., and Obsa, M. S. (2020). Prevalence of female genital mutilation among women in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon 6:e04403. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04403

Gerke, J., Gfrörer, T., Mattstedt, F. K., Hoffmann, U., Fegert, J. M., and Rassenhofer, M. (2023). Long-term mental health consequences of female- versus male-perpetrated child sexual abuse. Child Abus. Negl. 143:106240. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2023.106240

Girón, A., and Kazemikhasragh, A. (2022). Gender equality and economic growth in Asia and Africa: empirical analysis of developing and least developed countries. J. Knowl. Econ. 13, 1433–1443. doi: 10.1007/s13132-021-00782-1

Glass, C., and Cook, A. (2016). Leading at the top: understanding women's challenges above theglass ceiling. Leadersh. Q. 27, 51–63. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.09.003

Grant, M. J., and Behrman, J. R. (2010). Gender gaps in educational attainment in less developed countries. Popul. Dev. Rev. 36, 71–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2010.00318.x

Gretland, E., Robinson, B., and Baig, T. (2014). An investigation into the barriers to female education in Link Ethiopia schools. Barriers-To-Girls-Education. Available at: http://linkethiopia.org

Groeneveld, S., Bakker, V., and Schmidt, E. (2020). Breaking the glass ceiling, but facing a glass cliff? The role of organizational decline in women's representation in leadership positions in Dutch civil service organizations. Public Adm. 98, 441–464. doi: 10.1111/padm.12632

Gruber, J., and Fineran, S. (2016). Sexual harassment, bullying, and school outcomes for high school girls and boys. Violence Against Women 22, 112–133. doi: 10.1177/1077801215599079

Gunderson, E. A., Ramirez, G., Levine, S. C., and Beilock, S. L. (2012). The role of parents and teachers in the development of gender-related math attitudes. Sex Roles 66, 153–166. doi: 10.1007/s11199-011-9996-2

Gurmu, T. G. (2020). Primary school principals in Ethiopia: selection and preparation. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 48, 651–681. doi: 10.1177/1741143219836673

Guthridge, M., Kirkman, M., Penovic, T., and Giummarra, M. J. (2022). Promoting gender equality: a systematic review of interventions. Soc. Justice Res. 35, 318–343. doi: 10.1007/s11211-022-00398-z

Hailu, M. F. (2019). Examining the role of girl effect in contributing to positive education ideologies for girls in Ethiopia. Gend. Educ. 31, 986–999. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2018.1440284

Harner, H. M., Wyant, B. R., and da Silva, F. (2017). Prison ain't free like everyone thinks”: financial stressors faced by incarcerated women. Qual. Health Res. 27, 688–699. doi: 10.1177/1049732316664460

Heijstra, T. M., Steinthorsdóttir, F. S., and Einarsdóttir, T. (2017). Academic career making and the double-edged role of academic housework. Gend. Educ. 29, 764–780. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2016.1171825

Hennink, M. M., Kaiser, B. N., and Weber, M. B. (2019). What influences saturation? Estimating sample sizes in focus group research. Qual. Health Res. 29, 1483–1496. doi: 10.1177/1049732318821692

Heymann, J., Varvaro-Toney, S., Raub, A., Kabir, F., and Sprague, A. (2023). Race, ethnicity, and discrimination at work: a new analysis of legal protections and gaps in all 193 UN countries. An Int. J. 42, 2040–7149. doi: 10.1108/EDI-01-2022-0027

Hoobler, J. M., Hu, J., and Wilson, M. (2013). Do workers who experience conflict between the work and family domains hit a ‘glass ceiling?': a meta-analytic examination” J. Vocat. Behav. 83:280. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2013.05.008

Iqbal, A., Hassan, S., Mahmood, H., and Tanveer, M. (2022). Gender equality, education, economic growth and religious tensions nexus in developing countries: a spatial analysis approach. Heliyon 8:e11394. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11394

Jalalzai, F. (2008). Women rule: shattering the executive glass ceiling. Polit. Gend. 4, 205–231. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X08000317

Jenkins, E. K., Slemon, A., Haines-Saah, R. J., and Oliffe, J. (2018). A guide to multisite qualitative analysis. Qual. Health Res. 28, 1969–1977. doi: 10.1177/1049732318786703

Jiménez, T. R., and Orozco, M. (2021). Prompts, not questions: Four techniques for crafting better interview protocols. Qual. Psychol. 44, 507–528. doi: 10.1007/s11133-021-09483-2

Jouini, E., Karehnke, P., and Napp, C. (2018). Stereotypes, under confidence and decision-making with an application to gender and math. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 148, 1–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2018.02.002

Karlsson, I., and Simonsson, M. (2008). Gender watch: still watching, by Kate Myers and Hazel Taylor and Revisiting gender training: the making and remaking of gender knowledge. A global sourcebook, edited by Maitrayee Mukhopadhyay and Franz Wong. Gend. Educ. 20, 409–411. doi: 10.1080/09540250802211135

Karoui, K., and Feki, R. (2018). The impacts of gender inequality in education on economic growth in Tunisia: an empirical analysis. Qual. Quant. 52, 1265–1273. doi: 10.1007/s11135-017-0518-3

Kassa, G. M., and Abajobir, A. A. (2020). Prevalence of violence against women in Ethiopia: a meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abus. 21, 624–637. doi: 10.1177/1524838018782205

Kedir, A., and Admasachew, L. (2010). Violence against women in Ethiopia. Gender Place Cult. 17, 437–452. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2010.485832

Kefale, B., M, Y., Damtie, Y. A. M., and Adane, B. (2021). Predictors of sexual violence among female students in higher education institutions in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 16:e0247386. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247386

Kemp, L. J., and Zhao, F. (2016). Influences of cultural orientations on Emirati women's careers. Pers. Rev. 45, 988–1009. doi: 10.1108/PR-08-2014-0187

Klasen, S. (2018). The impact of gender inequality on economic performance in developing countries. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 10, 279–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev-resource-100517-023429

Koenig, A. M., and Eagly, A. H. (2014). Evidence for the social role theory of stereotype content: observations of groups' roles shape stereotypes. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 107, 371–392. doi: 10.1037/a0037215

Kunz, J., and Ludwig, L. M. (2022). Curbing discriminating human resource practices-a micro founded perspective. Schmalenbach J. Bus. Res. 74, 307–344. doi: 10.1007/s41471-022-00136-w

Le Mat, M. L. J. (2016). Sexual violence is not good for our country's development. Students' interpretations of sexual violence in a secondary school in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Gend. Educ. 28, 562–580. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2015.1134768

Levorsen, M., Aoki, R., Matsumoto, K., Sedikides, C., and Izuma, K. (2023). The self-concept is represented in the medial prefrontal cortex in terms of self-importance. J. Neurosci. 43, 3675–3686. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2178-22.2023

Madsen, S. R. (2012). Women and leadership in higher education: current realities, challenges, and future directions. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 14, 131–139. doi: 10.1177/1523422311436299

Maheshwari, G., Gonzalez-Tamayo, L. A., and Olarewaju, A. D. (2023). An exploratory study on barriers and enablers for women leaders in higher education institutions in Mexico. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 1–17. doi: 10.1177/17411432231153295

Mekasha, K. G. (2017). Women's role and their styles of leadership. Int. J. Educ. Adm. Policy Stud. 9, 28–34. doi: 10.5897/ijeaps2015.0415

Mekonnen, B. D., and Wubneh, C. A. (2022). Sexual violence against female students in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex. Cult. 26, 776–791. doi: 10.1007/s12119-021-09899-6

MoE (2016). Education Statistics Annual Abstract. Addis Ababa. Available at: http://www.moe.gov.et/ (accessed June 7, 2020).

MoE (2021). Education Statistics Annual Abstract (ESAA). Addis Ababa. Available at: http://www.moe.gov.et (accessed March 25, 2022).

Molla, T., and Cuthbert, D. (2014). Qualitative inequality: experiences of women in Ethiopian higher education. Gend. Educ. 26, 759–775. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2014.970614

Montas-Hunter, S. S. (2012). Self-Efficacy and Latina Leaders in higher education. J. Hispanic High. Educ. 11, 315–335. doi: 10.1177/1538192712441709

Morais, H. B., Alexander, A. A., Fix, R. L., and Burkhart, B. R. (2018). Childhood sexual abuse in adolescents adjudicated for sexual offenses: mental health consequences and sexual offending behaviors. Sex. Abus. J. Res. Treat. 30, 23–42. doi: 10.1177/1079063215625224

Öztürk, I., and Simşek, A. H. (2019). Systematic review of glass ceiling effect in academia: the case of Turkey. OPUS Int. J. Soc. Res. 13, 481–499. doi: 10.26466/opus.592860

Paprotny, D. (2021). Convergence between developed and developing countries: a centennial perspective. Soc. Indic. Res. 153, 193–225. doi: 10.1007/s11205-020-02488-4

Patrinos, H. A., and Psacharopoulos, G. (2020). “Returns to education in developing countries,” in The Economics of Education: A Comprehensive Overview, eds. S. Bradley, and C. Green (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 53–64. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-815391-8.00004-5

Rabiee, F. (2004). Focus-group interview and data analysis. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 63, 655–660. doi: 10.1079/pns2004399

Rammohan, A., and Vu, P. (2018). Gender inequality in education and kinship norms in India. Fem. Econ. 24, 142–167. doi: 10.1080/13545701.2017.1364399

Ridgeway, C. L. (2014). Presidential address why status matters for inequality. Am. Sociol. Rev. 79, 1–16. doi: 10.1177/0003122413515997

Scambor, E., Bergmann, N., Wojnicka, K., Belghiti-Mahut, S., Hearn, J., Holter, Ø. G., et al. (2014). Men and gender equality: European insights. Men Masc. 17, 552–577. doi: 10.1177/1097184X14558239

Scheelbeek, P. F. D., Hamza, Y. A., Schellenberg, J., and Hill, Z. (2020). Improving the use of focus group discussions in low-income settings. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 20, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12874-020-01168-8

Schneider, M. C., and Bos, A. L. (2019). The application of social role theory to the study of gender in politics. Polit. Psychol. 40, 173–213. doi: 10.1111/pops.12573

Semela, T., Bekele, H., and Abraham, R. (2019). Women and development in Ethiopia: a sociohistorical analysis. J. Dev. Soc. 35, 230–255. doi: 10.1177/0169796X19844438

Setegn, T., Lakew, Y., and Deribe, K. (2016). Geographic variation and factors associated with female genital mutilation among reproductive age women in Ethiopia: a national population-based survey. PLoS ONE 11, 1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145329

Smidt, T. B., Pétursdóttir, G. M., and Einarsdóttir, Þ*. (2017). How do you take time? Work–life balance policies versus neoliberal, social and cultural incentive mechanisms in Icelandic higher education. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 16, 123–140. doi: 10.1177/1474904116673075

Smith, P., Caputi, P., and Crittenden, N. (2012). A maze of metaphors around glass ceilings. Gend. Manag. An Int. J. 27, 436–448. doi: 10.1108/17542411211273432

Spector, N. D., Cull, W., Daniels, S. R., Gilhooly, J., Hall, J., Horn, I., et al. (2014). Gender and generational influences on the pediatric workforce and practice. Pediatrics 133, 1112–1121. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3016

Stanley, N., and Devaney, J. (2017). Gender-based violence: evidence from Europe. Psychol. Violence 7, 329–332. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000120

Tabassum, N., and Nayak, B. S. (2021). Gender stereotypes and their impact on women's career progressions from a managerial perspective. IIM Kozhikode Soc. Manag. Rev. 10, 192–208. doi: 10.1177/2277975220975513

Tak, S., and Catsambis, S. (2023). Video games for boys and chatting for girls: gender, screen time activities and academic achievement in high school. Educ. Inf. Technol. 28, 15415–15443. doi: 10.1007/s10639-023-11638-3

Tekleselassie, A. A., and Roach, V. (2021). Leveraging women's leadership talent to promote a social justice agenda in Ethiopian schools. Teach. Coll. Rec. 123, 176–201. doi: 10.1177/01614681211048656

Tirussew, T., Amare, A., Jeilu, O., Tassew, W., Aklilu, D., and Berhannu, A. (2018). Ethiopian education development roadmap (2018-30). Available at: https://5y1.org/download/f80344e9046fa0346fc402c29dd76288.pdf (accessed March 18, 2022).

Tomàs, M., Lavie, J. M., del Mar Duran, M., and Guillamon, C. (2010). Women in academic administration at the university. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 38, 487–498. doi: 10.1177/1741143210368266

Tomaszewski, L. E., Zarestky, J., and Gonzalez, E. (2020). Planning qualitative research: design and decision making for new researchers. Int. J. Qual. Methods 19, 1–7. doi: 10.1177/1609406920967174

Unterhalter, E., Arnot, M., Lloyd, C., Moletsane, L., Murphy-Graham, E., North, A., et al. (2014). Girls' Education and Gender Equality: Education Rigorous Literature Review. London: DfID.

Ware, S. (2010). Writing women's lives: One historian's perspective. J. Interdiscip. Hist. 40, 413–435. doi: 10.1162/jinh.2010.40.3.413

Webster-Kogen, I. (2013). Engendering home land: migration, diaspora and feminism in Ethiopian music. J. African Cult. Stud. 25, 183–196. doi: 10.1080/13696815.2013.793160

Woldegebriel, M. M., and Mekonnen, G. T. (2023). Leadership experience and coping strategies of women secondary school principals: lesson from Ethiopia. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 1–15. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2023.2267009

Wood, W., and Eagly, A. H. (2012). Biosocial Construction of Sex Differences and Similarities in Behavior, 1st Edn. Amsterdam: Elsevier Inc. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394281-4.00002-7

Worke, M. D., Koricha, Z. B., and Debelew, G. T. (2020). Prevalence of sexual violence in Ethiopian workplaces: systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod. Health 17, 1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12978-020-01050-2

Wroblewski, A. (2019). Women in higher education management: agents for cultural and structural change? Soc. Sci. 8:172. doi: 10.3390/socsci8060172

Keywords: discrimination, female principal, gender inequality, glass ceiling, social role theory, women leaders

Citation: Alemu A (2024) How female principals in Ethiopia fight for gender justice: a qualitative study of their challenges and strategies. Front. Educ. 9:1383942. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1383942

Received: 08 February 2024; Accepted: 28 August 2024;

Published: 14 October 2024.

Edited by:

Margaret Grogan, Chapman University, United StatesReviewed by:

Fernando Barragán-Medero, University of La Laguna, SpainFrancis Thaise A. Cimene, University of Science and Technology of Southern Philippines, Philippines

Copyright © 2024 Alemu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.