94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

METHODS article

Front. Educ., 21 June 2024

Sec. Assessment, Testing and Applied Measurement

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1372142

This article is part of the Research TopicMotivation in Learning and Performance in the Arts and SportsView all 11 articles

The basic finding uniting the researchers is that motivation is the weakest educational component, which prompted us to create and suggest a practical model of motivational competence. The project is based on the researchers’ descriptions of students’ motivational leading variables. Our main finding is lack of a value system and moral virtues in the foundation of motivation. The constructive components of the model cognition, cogitation, and skills were built on that basis. The main functional approaches in the study with the model are communication, feedback, and critical thinking. The model aims: (1) to direct teachers in creating and maintaining students’ motivation through motivational competence based on human values and virtues and (2) to strongly recommend that educational policies must pinpoint a value system and moral criteria for schools and universities so that educators can rigorously develop them in students through motivation. The contributions of the model are: (1) it is based on the crucial need for a strong value system and moral virtues in the foundation of students’ motivation and behavior; (2) it is bidirectional—developing students’ motivational competence, in parallel it increases teachers’ motivational competencies; (3) it argues that motivational competence must be the professional imperative leading to the curriculum purposes of teaching–learning process on the foundation of competence, high spiritual qualities, and morality.

The rationale of this project is that the issue of motivational competence measured upon society is an adequate frame to describe the degree of success in any life practice. That premises the role of motivational competence as a significant factor in the development of responsibility and accountability of education. The concern is that motivation has waned in effectiveness over recent decades and become the weakest educational component. School teachers encounter difficulties in engaging students in the classwork and are helpless to encourage them with the homework. University lecturers generally accept that students are naturally motivated due to their intrinsic desire to study a speciality as a future profession. However, this is less likely to be the general case of motivation. The decrease in motivation in many countries worldwide is more likely because the applied motivational methods and approaches do not have sufficiently encompassing expediency at their core, which necessitates education in motivational competence and motivational approaches to be laid on a new converting basis through the perspective of human spiritual development.

We summarized the motivation variables in the research study (see Section 2) and classified them into three groups, namely, lacks, obstacles, and needs. Our main finding is the lack of a value system and moral criteria at the core of the motivation structure. Although, there are scientists who marked this issue [Han, 2015; Kristjánsson, 2021, etc. see subsections 2.3. and 3.4.]. To overcome the shortage of strictly necessary spiritual values and virtues nowadays, MMC suggests ideas for strategic communication, feedback, and critical thinking as functional approaches (see subsections 3.1, 3.2, and 3.3).

The model depends on the methodological validity of the studies and the resources used. Considering the broad perspective of motivation, the purpose of the model is to assist educators in gradually increasing learners’ motivational competence in the direction of human value system and moral criteria. They can create and support students’ motivation in decision-making and subsequent behavior based on values and virtues. The model functions in any educational setting from pre-school to tertiary levels of education. Referring to the vital human values and virtues, for meeting students’ needs and achieving the curriculum purposes, it will provide a good foundation for the further flourishing of morality. Hence, the main tasks of the model are to fill the gap of values and virtues in the motivational character through:

• Infusion of human values and moral virtues in students’ motivational competence for substantiation and inciting to spiritual evolution;

• Gradually teaching motivational competence on the foundation of a value system and moral virtues;

• Fast acquisition of values and virtues and using them in the motivation arguments;

• Development of students’ motivation skills in the motivation argumentation;

• Maintaining the achieved motivation level and upgrading it;

• Simultaneously, the model develops educators’ attention to the value system and moral criteria in the essence of motivation argumentation during teaching.

Hereof, the highlighted question is: “How can teachers engage students in learning and create and maintain their motivation for achieving curriculum purposes, premised on a value system, and moral criteria through critical thinking?” In brief, the MMC gives educators’ information about the valuable constructs of motivational competence. The model derives knowledge through communication—interpersonal, individuality-oriented, and emotionally dynamic; integrates elements of students’/educator’s cognition, cogitation, skills, and behavioral systems; directs critical thinking at values and virtues to fulfill the learning objective. The model brings these ideas together through a set of open-ended questions and directs the subsequent answers and arguments to a moral- and value-based educational purpose. The extent to which the model is operationally defined, and can be utilized and evaluated, is across all stages of education—from kindergarten to tertiary levels.

The creation of the Model of Motivational Competence (MMC) is literature-based and is restricted to motivation learning theories and articles that researched multiple motivation variables in education through the perspectives of those theories.

We applied a comprehensive approach to generalize the findings on motivation for learning from the perspective of motivation learning theories and practices. Gopalan et al. (2017), Al-Harthy (2016), Schunk et al. (2020), Schunk et al. (2020), Weiner (1985), Elliot and Dweck (2005, 2017), and Lai (2011) have provided broad literature reviews of motivation theories and motivation. All theories group under this name a substantial number of variables characterizing various aspects, ideas, and conceptions. Weiner’s (1985) attributional theory of achievement motivation is one of the recent theories which has been followed by numerous researchers.

What expands the issue of motivation are many studies on multiple aspects of motivation learning theories for achievement motivation: achievement goal theory (Pintrich, 2000), expectancy-value theory (Wigfield and Eccles, 2000), and the role of self-determination theory in understanding the educational process (Ryan and Deci, 2000, 2018; Bieg et al., 2011; Ten Cate et al., 2011; Deci and Ryan, 2012; Reeve and Su, 2014). Schunk (1991), Zimmerman (2000a), and Artino (2012) emphasize the significance of self-efficacy in fostering motivation for learning. Pajares (2008) integrates both perspectives by acknowledging the motivational influence of self-efficacy and advocating for self-regulated learning. Other researchers, such as Artino et al. (2012) and Lahey (2016), predicate their ideas on the control-value theory and the role of emotion for motivation or as Broussard and Garrison (2009), Eccles (2005), and Steinmayr et al. (2019) predicate on achievement-related choices, as Eccles underlines psychologically measured “subjective task value.”

Elliot and Dweck’s (2005) concept of “competence as the core of achievement motivation” is essential to our model. The same authors (2017) illuminated the “competence” wider as the “conceptual core of the achievement motivation literature,” which involves a shift in terminology “from achievement motivation to competence motivation” (p. 3). They wrote about some factors’ impact on achievement motivation such as “competence acquisition (learning goals)” and “competence validation (performance goals)” (p. 135). We consider Elliot and Dweck’s term “competence motivation” important to general competence in education. However, we establish our concept of “motivational competence” (MC) as a single aspect of “competence motivation.” Our concept includes a particular content regarding a level, quality, and scope of knowledge in terms of motivation. Therefore, we called our project Model of Motivational Competence. In other words, MC acts in the interactive field of general cognition (Cgn), collecting knowledge of motivation, and here the impact of mindsets on competence is an important factor (Dweck and Molden, 2017). The valuable constructs of MC are presented in Section 4. The MMC’s Structural Composite Parts.

Generally, society, unnoticedly or overt, always fosters one’s motivation, and in turn, the motivation effect is reflected in society in the short- or long-term period. Respectively, some authors trace the problem of motivation from the social viewpoint. Zimmerman (2000b) examines motivation within the framework of self-regulation theory from a social-cognitive perspective. Others research the triad “school-students-teachers. Ferreira et al. (2011) consider the social aspect of school as a motivational variable and state that “a positive sense of school belonging may improve students’ academic motivation” (p. 1713). Boström and Bostedt (2020) consider students’ and teachers’ perspectives on motivation; Schlosser (1992) researches the correlation between teacher distance and student disengagement, which influences motivation; Turner (1995) shows the influence of classroom contexts on motivation which is a specific social setting. From the contemporary standpoint of motivation for learning and performance, Keller’s (2010) ARCS model approach (Attention, Relevance, Confidence, and Satisfaction) is useful and helps work on students’ motivation individually aimed at achievement and psychological support.

Social aspects of motivation are becoming crucial rapidly since the geopolitical situation is becoming increasingly dangerous, and European countries and mankind are threatened with war. In these conditions, the increasing prevalence of the phenomena of “moral disengagement” has substantial social significance. Chugh et al.’s (2014) “withstanding moral disengagement” is not only alarming but ominous as social behavior (McCreary, 2012) and evil for society (Brendel and Hankerson, 2022). Psychologists are concerned about business ethics in parallel with that phenomenon (Schaefer and Bouwmeester, 2020), and sociologists are concerned about behavior in the workplace organizational practices for social justice (Rashkova et al., 2023). This proves the importance of the connection between the social and moral aspects of motivation.

In the last decades, moral education has appeared to be an interdisciplinary section of education science bound to positive psychology, psychology of education, moral philosophy, and virtue ethics. Tangney et al. (2007) researched moral emotions such as shame, guilt, and embarrassment, and how they influence the link between moral standards and moral behavior, which confirms the idea that moral education should start with preschool education because of the collapse of traditional moral values and the degradation of moral virtues that we have all witnessed in recent decades. Ljubetić (2012) wrote about “reigning―valuelessness and disorientation” (p. 82), Damon (1990) suggested how to nurture the growth of a “moral child,” and Krettenauer et al. (2013) developed the idea of the relationship between moral emotions and the development of the moral self in childhood. Accepting purpose as a moral virtue for flourishing, Han (2015) wrote what could inspire moral education is ‘the developmental goal of moral education aiming at flourishing’ (p. 6). Kristjánsson (2021) reasons about the present and future of moral education and is concerned about “a balance of virtues within a life ordered according to a ‘golden mean’” (p. 119). Hamby (2014), looking at the issue from a different perspective, shared an important view regarding critical thinkers’ moral virtues.

We consider for a good start authors’ research where they posed the issue of morality in education. However, researchers do not set the value system and the moral criteria as an evolutionary foundation of motivation and for educational system development. We devoted the subsection 3.4. Morality at the core of motivation to this issue. We highlight the placement of the value system and moral coordinates as an approach to MC because they lead to humanizing and moralizing the trend of cognition and cogitation in education as a prerequisite for well-motivated behavior, which widens the scope of the main contribution of the model, and some essential arguments support it.

We broadly summarized motivation learning theories and practices and their social and moral aspects in the literature above (and References). However, we could not single out those criteria in the canvas of the research study which set generally valid coordinates to unite learners in motivation (albeit through the perspective of different theories). Shortage fostered us to infuse the pursuit of universal human values and moral virtues into the core of motivation. Human values and virtues are the parameters setting the coordinates of a generally valid value system and unitive moral criteria. Awareness, focused on values and virtues, enables individuals to draw reasonable, substantiated, and justified inferences. In view of this, our MMC firmly emphasizes the value system and moral criteria as a vital functional component in the motivation canvas. As valuable coordinates, they will humanize the direction of cognition (Cgn) and cogitation (Cgt), which is needed for education to achieve.

Why Cgn and Cgt must have a moral and humanizing direction in education? First, knowledge (Cgn) is a prerequisite in the foundation of any development—educational, individual, spiritual, physical, cultural, esthetical, social, political, and religious. Second, through knowledge, mankind can develop reasoning faculties (Cgt) and expand their reasoning capacity and can evolve. Third, knowledge and reasoning faculties are fundamental constituents of the model which can be naturally saturated with human values and moral virtues throughout education. Furthermore, they give coordinates, through which a human being will or will not be placed in the correct sector of the coordinate system of mankind’s evolutionary development.

Consequently, the value system and moral virtues must be taught at all educational levels. This is a pressing need for the education of the generation. Therefore, educational policies ought to define their emergent priorities for humanizing the trend of cognition; not to make changes based on which lies the insidious idea of hybridization (between AI-artificial intelligence and OI-original intelligence), and hence, dehumanization. The latter processes are proceeding in a gradual, subtle way but with much more harmful and long-term effects. Through a variety of means, good education policies can help the next generations grow up morally with a strong value system. Education in morals and virtues is available to the powerless in the fight against the powerful.

The above information in Section 2 and its subsections is a compelling premise that our idea of motivational competence, based on a value coordinate system and moral criteria, deserves special attention in the teaching–learning process at all educational levels. Additionally, Meece et al. (2006) noted a direct relationship between classroom goal structure, student motivation, and academic achievement. We agree and insist that such a relationship builds educational success and the morality of adolescents and the young generation, as well as motivated behavior in life. Therefore, values and virtues ought to be embodied in the purpose structure through expedient communication, productive feedback, and effective critical thinking, acting to achieve the goal. The new in MMC is that it can develop the moral aspect of education by appealing to values and moral virtues in the purpose structure. It can cultivate morality through value motivation, willpower, self-regulation, and self-expression only on the right track. The process comprehends kindergarten (Ljubetić, 2012) and motivation in primary, secondary, and higher school and at tertiary levels of education (Schunk, 1991; Steinmayr et al., 2019; Schunk et al., 2020, etc.), which is obligatory because the fight against “reigning valuelessness,” in other words, against degenerate-depraved-perverted “values” nowadays, begins even before birth.

For this literature-based research, we applied a set of methods and approaches. Initially, we applied the literary research method to 47 articles on motivation in education—26 about motivation in school and 21 about motivation in university. Then, we used the methods of analysis and synthesis of the key variables of motivation presented by the researchers in their findings. By the method of summary, we excerpted the most significant variables for students’ motivation and classified them into main three groups of variables, namely, lacks, obstacles, and needs. The picture of the model was built by applying the relational approach that investigates the relationships between the four composite parts of the model (see Section 4. The MMC’s Structural Composite Parts), which potentially contain those variables. The description method and function analysis method were utilized to elucidate the three composite parts, namely, Cgn, skills (Sk), and Cgt as a special reasoning ability. The purpose (P) of a learning setting is the main goal of the model’s function. Everything is depicted, described, and explained in Figures 1–5 in Section 4.

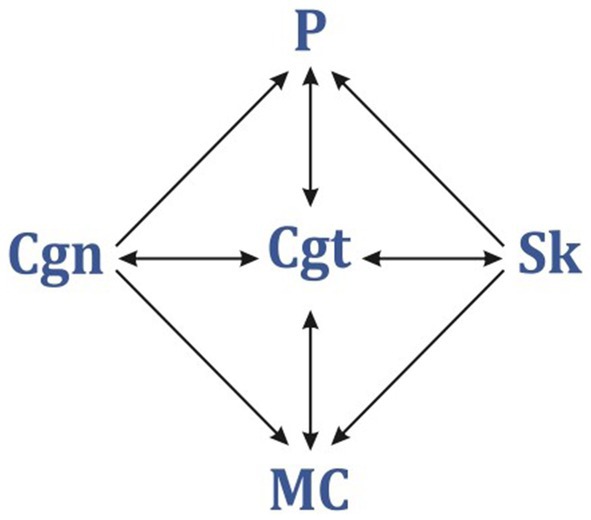

Figure 1. The Model of Motivational Competence. MC, motivational competence; Cgn, cognition; Cgt, cogitation; Sk, skills; P, purpose.

In summary, the important conceptual trend of MMC is a recovery of morality in education (school and university) as a personal and public value. The argument is that the present, strained by armed events in Europe and worldwide recently, is in danger of war. Contemporary geopolitical events impinge on the sociopolitical variables and morality of every country. We are witnessing vandalism, aggression, and murder of students and teachers by teenagers and young men. Those factors and the variety of national sociocultural and socioeducational traditions, religions, the role of social media on mental health, specific local, and individual features logically predetermine the issue of morality in education, hence in motivation, to be viewed in a holistic context. For the reasons above, and because education is the moral corrective of society, it is mandatory to make a deeper humanization of education in the sense of human existence based on human values and the spirituality and morality which define and distinguish mankind. The contribution of our model is in four aspects: (1) the need for education to address the spiritual essence of the human being, (2) the function of education as upbringing must be based on a value system and moral criteria, (3) the need for goal-setting of values and virtues in the roots of motivation and at the core of the learning purpose, and (4) the new generation of 21st century needs to be educated to think humanely and generate decisions through the perspective of spiritual evolution.

The implementation of the model in teaching practices requires expedient scientific approaches. The theory and practice of the competency-based approach, extended at the beginning of the XXI century and presented by Makulova et al. (2015), aim to find out one’s core competence. The core competence in our model is motivational competence (MC). Readiness to work with that special knowledge for a given purpose (P) requires a certain level of reasoning faculties (Cgt), as well as the teacher’s skills (Sk) such as language use, strategies use, intonation, body language, personal manners of influence, awareness, and confidence. Additionally, to build motivational competence following the model, educators need to use three essential functional approaches, which are the main success determinants of MMC: expedient communication, productive feedback, and effective critical thinking, respectively, presented in Sections 3.1, 3.2, and 3.3. They aim to generate appropriate human values and moral virtues in the motivation purpose structure, in the possible student’s choice and behavior due to their social and cultural contextual factors.

Generally, it is necessary to employ a communication-based approach to the learning process (Hovland, 2005; Richards, 2006; Hunt, 2007) through questions, respectively, the main lacks, obstacles and needs to be found out, expounded on and interpreted properly. Hunt’s report (2007) provided evidence from all over the world of the role of communications in education, their successfulness and weaknesses and underlined the importance of “prioritizing communications” for development principles and methodologies in all problematic areas (p. 2). His idea emphasized the need for communication to be expanded with the involvement of parents’ opinions (p. 30). Richards (2006) underlined that one important aspect of knowledge is “knowing how to maintain communication” despite having limitations (p. 3). Hovland (2005) considered the issue of a successful communicative toolkit for researchers. Those viewpoints support the MMC’s idea that motivational competence requires educators to manifest good communicative competence and communicative skills in their relationships with learners and, in particular, with school students’ parents.

In research of numerous sources, Morreale et al. (2000) gave evidence of the importance of communication education. As Morreale and Pearson (2008) later asserted, communication instruction is a “pressing need” at all levels of the educational system in the USA. They summarized four major themes supporting the importance of communication education: (1) the development of the whole person, (2) the improvement of the educational enterprise, (3) being a responsible participant in the world, both socially and culturally, and (4) succeeding in one’s career and the business enterprise (p. 225). Additionally, the fifth theme in the 2000 study highlighted the need for communication education provided by specialists. The authors concluded that competence in oral communication is “a prerequisite to academic, personal, and professional success” (ibid). Importantly, the authors underlined that one can have “the ability to vocalize”; however, it cannot be a condition for “a full accoutrement of the knowledge, attitudes, and skills” (p. 225) that constitute communication competence, which unequivocally illuminates MMC’s assertion of the glaring need for achieving a higher level of communicative competence and communicative skills in education. It raises the idea that communication education to be included in the school curriculums where there is a gap, which can support education in a valuable worldview.

The study of communication can be from different points of view and aspects: due to the participators’ communicative traits, e.g., students’ (Martin and Myers, 2006), or the influence of the instructor’s in-class communicative behaviors on the student’s participation in out-of-class communication (Myers et al., 2005); the importance of the processes of listening (McCracken, 2006), speaking, understanding, reasoning, as well as the quality of communication such as clarity, caution when analyzing, persuasiveness, comprehensiveness, etc. Keeping in mind that communicative competence starts developing from the kindergarten educational level, goes through all educational levels, and continues during the lifetime, which underlines the all-pervasive educator’s influence on learners in the communicative process.

What aspects of communication do the model develop? In the MMC, the concept of expedient communication was formed for several reasons. First of all, in broad outline, communication is a sharing of interests. Due to our model, communication is expedient because educators focus on human values and virtues (their interest in upbringing), and simultaneously, their focus is on the individual’s needs for self-expression and self-realization (his/her interests). Second, communication operates in an individual’s Cgn, Cgt, and Sk fields. It makes the process of finding the expedient questions to motivate the student easier, faster, and more productive. Third, expedient communication may derive the values and virtues from the task, the subject, or the curriculum purpose. Finally, when a teacher works on students’ MC, communication is not just a smart dialog—teaching information on motivation and receiving students’ feedback on how information is reflected. On the contrary, communication as an expedient approach directs the received information to spiritual values through psychological attitudes, inclinations, and intrinsic needs.

Moreover, the concept of expedient communication is used and applied as a key functional approach due to three of the functional spheres of interrelationships—education, administration, and social sphere: (1) in education—to state explicitly that communication lacks the essential and much-needed topic on issues of value system and moral criteria in the learning process; (2) in administration: we insist that the value system and the moral criteria must be institutionalized, implemented, and consolidated in education by educational policies at all stages of education administration; and (3) in the social sphere: the recovery of morality, through a thorough study the discipline of Ethics and the spiritual upbringing in education, will have an impact on society to make a progress in the morality and the spirituality in the long-term. Otherwise, as Jansen (2002) shows beyond doubt, we will witness “political symbolism as policy craft” to explain the insignificant efforts in the implementation.

Additionally, applied to the MMC, this communication is motivational with value-laden and virtue-directed content, emanating from curriculum purposes and an individual’s needs. Finally, all those content elements are managed through the instructor’s communicative skills, motivational competence level, and high-value system level.

After identifying an individual’s level of MC, the teacher should use it properly. As already explained, data are collected through questions over the three substantial variables: lacks, obstacles, and needs. Teachers can develop learner-centered approaches to motivate an individual with moral virtues toward a given P. The P is the reached vitality of the impulse. The nature of an impulse reflects the motivational sense of the impulse giver. The impulse giver should interpret those MC elements which are compatible with the concrete individuality and incite activity toward the P. Concurrently, the teacher should not forget to extract the relevant moral values from the P in advance.

The pursued results of the expedient communication as a functional approach in the learning process are:

• To ensure quick and effective communication on learning issues;

• To provoke self-knowledge, self-esteem, and self-expression through values and virtues;

• To present new motivational knowledge about a value system and moral criteria;

• To train skills for expedient communication;

• To build an informed and motivated decision for a value-driven behavior;

• To disclose the learner’s capacity to achieve the purpose through values and virtues;

• To achieve proper, practicable, and learner’s solution to the problem with values and virtues in the rationale;

To identify the target results in advance.

The MMC claims that communication is bound up with productive feedback which is the second significant component for building and constantly developing motivational competence. The problem with the definition of feedback (FB)—its function and especially the content—is still an excavated but unshaped field with blurring boundaries. Some authors presented general feedback literature (Hattie and Timperley, 2007; Lipnevich et al., 2016). Walsh (2014) summarizes that students’ feedback “can be a crucial way to evaluate teaching, assess a new curriculum, and improve classroom achievement” (p. 1). Developing the idea of a “feedback culture,” Gehlbach et al. (2018) applied the psychological principle of cognitive dissonance to “cultivating teachers’ support” by using student-perception surveys as a component of teacher evaluations. Their findings about building the culture of feedback go through a bilateral and consistent process, centered on teachers: 1. teachers’ FB→for the principal’s work, 2. teachers’ FB→for the students’ work, and finally 3. students’ FB → for teachers’ work. However, the norm of evenhandedness will stay relative.

Essential information about feedback in a concise review of feedback models, their descriptions, and definitions is presented by Lipnevich and Panadero (2021). They provided comprehensive information about 14 feedback working models which may be utilized, assessed, estimated, and enriched. They integrated the 14 models and selected the most prominent elements of message, implementation, student, context, and agents. However, this generalized model does not include elements of human values and moral virtues. This gives us reason to be more categorical regarding the spiritual values to be the starting point for the feedback. As we said before, feedback is always bound with cognition, where cognitive processes act (Narciss and Huth, 2004). For education, pedagogical aspects of feedback are of paramount importance (Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick, 2006; Hattie and Timperley, 2007), how to activate feedback effectiveness (Carless and Boud, 2018), or student responses to feedback, moreover, they generate feedback, and both are crucial for the educational process (Lipnevich et al., 2016).

We agree that information delivered to students cannot be regarded as feedback (Boud and Molloy, 2013), and it is transferred by the teacher/lecturer or through various sources. However, the education process, through which one makes sense of the received information and uses it to enhance their work or learning strategies (Boud and Molloy, 2013), ensuring an individual response to the perceived information. In this sense, the interactive feedback educator-student builds loops, chains, and spirals forward through time (Carless et al., 2011; Carless, 2018).

In terms of motivational competence, we generally share the sense of Hattie and Timperley’s (2007) definition of “feedback as information provided by an agent (e.g., teacher, peer, book, parent, and self-experience) regarding aspects of one’s performance or understanding.” However, the issue of the difference between interpretation and feedback stays open. For the functions of the MMC, we conceptualize the feedback content as a motivation stimulus of paramount importance for learners to understand and encompass the new information about the two systems of human values and moral virtues so that they can utilize them for their purpose. The result of the feedback can be ascertained in the effectiveness of the decision and the behavioral response.

The survey analysis of the collected feedback information in class needs educators to apply an effective critical thinking approach. The MMC offered here was not created to unfold the concept of critical thinking (CT) in a new light but to confirm that education is in dire need of CT. As we have already cited (Section 3), the nature of critical thinking definitions is quite complicated (Cuban, 1984); there are policy and research dilemmas in the teaching of reasoning. However, from ancient times, it is well-known that Socratic Questioning is a CT teaching strategy (Beach, 2004). His questions are systematic and urge students to be aware of their steps in reasoning—not to make wrong assumptions, ignorance, misconceptions, and finally, false conclusions. The questions stimulate thinking but do not require a definite answer.

How to understand the concept of critical thinking? It has plenty of definitions from the perspectives of various scholars. On that occasion, Davies (2015) noted simply: “Critical thinking cannot be all things to all people.” Cuban (1984) more metaphorically and vividly evaluated the nature of the definitions as “being mired in a conceptual swamp” (p. 686). In support of the communication approach of our model, teachers can start with Benesch’s (1999) article about the significant skill of “thinking dialogically” to achieve CT and Brookfield’s (2012) suggestions on how to teach CT, and also dispositions toward CT should be considered (Facione, 2000). Contemporary researchers try to clarify the difficulties in teaching CT (Willingham, 2008) or show major factors such as elementary clarification, reasoning skills, judgment, assessment, and as a final step inference. Gelder (2005) presents some lessons from the view of cognitive science; Rasool et al. (2002) study how to apply CT in the diverse world today. For Cottrell (2005), developing effective analysis and argument is the main factor for CT skills.

Recently, a variety of models of critical thinking have been created, which is useful for teachers to have the possibility to choose any that is appropriate for a certain task and purpose. Davies (2015) suggests an easy-to-perceive and -understand model for teaching CT; Kuhn’s (1999) model is for developing CT; Case (2005) suggests how to move CT to the main stage. The model by Garrison et al. (2001) points out features such as triggering events, exploration, provision, and resolution.

Critical thinking is an “uncontested” essential skill in the 21st century within educational and professional settings (Heard et al., 2020). In addition to the curriculum goals of every subject, any education level is characterized by plenty of complementary objectives depending on the subjects studied. Accordingly, it is a huge undertaking to compose a self-sufficient CT model across various contexts—scientific, educational, social, psychological, personal, emotional, cultural, and linguistic. On the other hand, successful practices in various disciplines have normative force, so critical thinking must be closely tied to sound educational policies (Wain, 2017).

Our vision for CT is to focus on values and moral issues in the foundation of CT arguments in parallel with the other goals. This offers an additional asset for personal enhancement through the educational stages. Concurrently, the value system and moral virtues assert themselves as significant for educational policies. In brief, the MMC assumes the fundamental critical thinking skills offered by Facione (2023) as practical and easily achievable in education—analysis, explanation, evaluation, self-regulation, interpretation, and inference (p. 5). He also underlines the dispositions toward critical thinking (2000). In her literature review on critical thinking, Lai (2011) counts the components of critical thinking such as “analyzing arguments, making inferences, using inductive and deductive reasoning, judging or evaluating, and making decisions or solving problems” which involve cognitive skills and dispositions and some individual characteristics (p. 2).

Teachers can excerpt the decisive information through CT for education needs (Bieg et al., 2011). Applying CT in parallel with the relational approach, educators can build a more precise picture of learners’ MC levels and needs. The teacher should single out and pinpoint the characteristics of the level. The relational approach necessitates a better teacher to lead with questions and foster students in class.

The critical issue and limitation of MMC is the relative personal ability (student’s or teacher’s) of critical thinking that features a certain range of Cgt, which points to Cgn as a significant component. Knowledge is of paramount importance because skills without sufficient knowledge are semi-productive and semi-beneficial. An individual ought to make an achievement-related choice, parallel to personal, psychological, social, cultural, religious, ethnic, and ethical characteristics, as Eccles (2005) includes the “sense of competence for various tasks” (p. 108). As we have already discussed, competence is strongly associated with Cgn. While Cgn reflects sociocultural differences, Cgt reflects one’s intellectual reasoning abilities. Both underline the idea of the MMC that relevant educational tasks are covered by an individual’s Cgn, Cgt, and Sk, especially through CT.

Concurrently, we state that expedient communication and productive feedback in education need effective critical thinking to balance between them. If an educator wants to foster a student’s cogitation, which is bound to critical thinking. When collaborating with MMC, we point out the need for a parallel between the communication-based approach and the critical-thinking approach.

In our view, every definition can be just an aspect of wholeness since critical thinking in Western education has “wide endorsement” with “no proper account of it” (Barnett, 1997:1). There are also models of critical thinking more likely philosophical ones. Philosophical definitions are not of assistance in our case just to become a critical student and citizen in future but not to be taught critical thinking.

Our concept of effective critical thinking, as a functional approach for motivating, is about (a) having skills in reasoning (Cgt), which is a reach system of skills pointed out by researchers above, and (b) making inferences premised on a value system and moral criteria which have been proven traditionally over the centuries of our civilization. However, the concept has individual and social aspects depending on the scope of one’s worldview. The value-laden function of MMC cannot be realized without critical thinking. We do not have in mind critical thinking, approaching the ideal critical thinker, as philosophers write about, or their virtues (Hamby, 2014). We suggest teaching the skills listed by Facione (2023) and Lai (2011), through which teachers can excerpt the decisive information and build a precise picture of a student’s MC scope. Moreover, they can identify one’s MC level and construct a way to use it properly.

On the one hand, the critical thinking approach should aim at two important components of critical thinking: (a) students’ feeling of freedom when expressing individual opinions, needs, and wishes and (b) their needs to reveal, perceive, and be aware of themselves, which helps their development. On the other hand, by employing the critical thinking approach, the lecturer can consider the difference between the learner’s logic of wishes in relation to abilities, which will allow the educator to balance them with a proper motivation approach. In addition, plenty of professional, pedagogical, psychological, and management approaches can be used individually when seeking the most functional ways of creating motivation, such as validation of the broad creative functional approaches to the MMC’s purpose, such as expedient communication, productive feedback, and effective critical thinking in the human values coordinate system is the model’s success.

Finally, but substantially, is the idea of the new coordinate system of values and virtues in the canvas of the MMC and its application in education. More precisely, all methods and approaches utilized ought to be located in this coordinate system, since education is the field of knowledge, upbringing, and personality building of all learners at all educational levels. Our concern for the moral perspective of education, already mentioned above, is developed in the next section.

Nowadays, we are witnessing the accelerating slippage or decline of morality. Therefore, it is crucial to intensify our joint efforts in building student’s moral system from infancy. Krettenauer et al. (2013) developed the idea of the relation between moral emotions and the development of the moral self in childhood. Taking in mind that children usually start sports in middle childhood (even earlier), we find some important research studies: Kingsford et al. (2021) noticed that moral identity emerges at the age of 8–12 years; Etxebarria et al. (2015) considered pride as a moral motive which proves the link between moral pride and positive prosocial behavior in life. Their conclusion highlights the idea of exploring how moral pride “exerts its motivating effect in real life” (conclusion). Hence, the idea of pride as a moral motive can be successfully utilized to motivate and create morality among learners, especially those involved in sports and art. Kristjánsson (2021) wishes for better political research on moral education to take more place in the JME (Journal of Moral Education), which sounds indicative of the political significance of the issue.

Researchers continue studying morality from different aspects. Han’s (2015) idea of how a purpose can be turned into a moral virtue and the analysis of theoretical frameworks of moral education (Han, 2014) can help teachers develop their moral competence when collaborating with the MMC. Hamby (2014) highlights the virtues that lecturers of critical thinking should recognize the “conceptual importance” and should seek to “foster them in their students” (p. 170). The author underlines the most promising avenue for success in fostering critical thinking virtues, which is “to instruct for them explicitly as an independent track” within the existing curriculum (p. 174).

A very important concept of our model is that spiritual well-being is always based on moral engagement and critical thinking. From the moral point of view, the motivational considerations when giving instructions should be the energy of the purpose that can prompt the spirit to moral values. In this sense, the MMC is tolerant of both the individual’s Cgn, Sk, and Cgt and the needs and values which create morality. Exactly moral strength spiritually supports individuality. Collaborating with the model is an intervention for moral development that points to an individual’s characteristic along with their education, which can change the future virtually. Following Damon’s (1990) views on moral children’s growth in school and their moral commitment at all ages of life, we insist that MMC can be an educational tool that collaborates with the participants in the educational process, from preschool to tertial levels, to build the moral future of education and life. Why?

An important concept in moral studies relates to moral disengagement. The study by Malley-Morrison et al. (2009) of moral disengagement and engagement among adults showed an anxious picture of widespread moral indifference. Turner (2008) warned that moral disengagement could predict further “bullying and aggression,” which are some of the implications in civil society. However, where does it start? Definitely, in education. Sagone and Caroli (2013) reported civic moral disengagement in law (!) and psychology (!) university students which is a dangerous tendency. In their explanatory study, Cory and Hernandez (2014) were troubled by the moral disengagement in humanities majors (!) and business. George (2014) directed the interest to digital technology and moral disengagement as a predictive factor for digital aggression and cyberbullying (!). Detert et al. (2008) showed moral disengagement in ethical decision-making (!).

The list of researchers investigating the matter of morality in education is increasing in number, which is listed above as an insignificant number. The question is: How many researchers should prove the urgent need for changes in education in the direction of human values and moral virtues in order not to lose our future? Through our model, we strongly claim that educational policies are obliged to society to take measures to drastically change education at all levels toward its humanization, sound value system, and moral virtues leading to spirituality.

The model takes into account both occupational and general Cgn and Sk, respectively educators’ and students’ (and parents’ if needed). From a social-cultural point of view, the model is also a good approach to the assessment of both professional and common MC, which has practical utility for education. In this study, we propose MMC for educational goals. It can develop a motivational mindset and support teachers in motivating students more successfully. The model will be introduced both descriptively and analytically. First, let us look at it in Figure 1.

Our concept of MС is functional in three main directions: (a) movement and interaction of different individual knowledge (Cgn); (b) activation and development of individual independent reasoning (Cgt); (c) manifestation and growth of individual Sk. MC is ruled by a vast number of experiences and Cgn, Sk, and Cgt—how we can comprehend, think deeply, consider, and reflect on the components of these fields of information and how we can reason on correlations between them. The correlations between the fields in the horizontal line interrelate with both MC and P. Notwithstanding the information fields’ variety, there is a reason for thinking that MC has some common features that enable us to view it as a unitary whole of Cgn and Sk, and the process of Cgt, and that ensemble we called MC. Its functional role is to be the starting point to reach the main P, i.e., it delivers the language arguments and the possibility for an act to motivate others convincingly in achieving the motivational P. In general, Figure 1 indicates the relational approach to defining better ways to motivate.

From Figures 2–5, let us describe and analyze the individual fields and their interrelations and interactions. Figure 2 shows the base of the three fields—Cgn, Sk, and Cgt—that MC is modeled from. Cgn is a bank of knowledge one has gained in life. The field of Sk contains all abilities for applying the information gained. The content on this horizontal line is organized and interpreted by the core field of Cgt. Cgt is the main scientific approach as a process of analysis, comparison, synthesis, and generalization of the collected information in both fields. The main function of Cgt is to determine and classify the correlations between Cgn and Sk in order of importance and terms for motivation.

The bidirectional vectors illustrate the impact of Cgn and Sk on Cgt and its responses. It is the teacher’s verbal discourse with the other two fields, and in this network of cogitations, the extent of MC is clarified. Undoubtedly, the level of Cgt is an individual teacher’s and student’s characteristics, hence the result of all the reasoning, consideration, and reflection is consistent with the Cgt level.

Every field of Cgn, Cgt, and Sk can have multiple directions depending on the number of participants under investigation in certain circumstances. In other words, every direction surveys only one participant’s knowledge, skills, and thinking. For example, applied to the level of primary school especially (but not exclusively), the model is used in three directions: teacher, student, and parent. It can be used in the education (and not only) of all degrees, and then, the number of directions would be much greater due to the increased number of teachers at secondary schools or universities. We take ‘three directions’ in the sense of three vectors, each of which models particular competence viewed, respectively, as the teacher’s, student’s, and parent’s abilities to “fill in” their three fields of information—Cgn, Cgt, and Sk—undoubtedly, with some degree of relative certainty.

Figure 3 denotes the importance of interconnection and interaction between Cgn, Cgt, and Sk in seeking significant and pertinent information to achieve the P. Purpose is the goal that a teacher must be aware of. Unfortunately, most educators lose the “guiding light” to the P somewhere in the layers of the school subject material in which they immerse themselves deeply. As per our model, we observe the reason for that in the low degree of MC awareness. From this point of view, the higher the MC level, the clearer the approaches for motivating students to achieve the P. Another adverse impact can be observed in the shortage of good critical thinking that Cgt needs.

As the most important individual or teamwork component in learning and leadership in education, P is the last point of all participants’ efforts. P is on top of the pyramid as an expression of the essential function of the model. But in what way can it be reached? It is presented in Figures 4, 5.

In Figure 2, we observed that one’s general competencies encompass the entirety of knowledge and abilities within, respectively, the domains of Cgn and Sk. Figure 4, represented as shaded sectors, visualizes how MC is formed through the focused and purposeful efforts of Cgt to select just the expedient information from the two fields in favor of motivation. We have already observed how the contents of the Cgn and Sk fields are correlated and interact due to the Cgt field. The important function of Cgt has already been discussed in Section 3. Cgt appears to be the “leading activator” and “scholar-like conductor.” How does Cgt implement these functions? First of all, according to the characteristic of its nature, Cgt performs the most active thought processes—these are an individual’s reasoning skills. By Cgt, an individual (educator, learner) can deeply analyze and synthesize, depending on the level of their reasoning capacity, the important information about motivation in the Cgn field. In parallel, by induction, Cgt activates the appropriate action Sk and needs to make a decision and fulfills it. In addition, during the communication-feedback processes, both educator and learner can select and generalize the expedient data to form the picture of the learner’s MC field.

As every field has its level of different dimensions, the MC level can range from the most common to high professional, it depends on the content of the three fields which form it— Cgn, Cgt, and Sk. Following their capacity, the teacher or researcher can define the range of MC and classify it from low, through usual, to professional and their sublevels as well. MC is unitary of all expedient constructive elements of the three fields. MC can contain information, to the appropriate extent, about motivation theories, methods, approaches, means, cultural characteristics, belief-ethnical features, psychology, personal experience, and individual characteristics, as well as relevant skills for applying all this knowledge in practice. As we have already stated, the approach to recognizing the individual scale of MC must be applied in a holistic context.

Moreover, the recognition and elicitation of human values and moral virtues from the purpose of the task (in schools or university curriculums) are of paramount importance at this stage of the motivational process. They must be highlighted by the teacher.

Since the MC contains essential information about motivation, the P (educational or managerial) is the point where the MC accomplishes its goal-directed manifestation. In this manifestation, Cgt is of paramount importance again. Cgt adheres to the principles of interrelations and congruence between the Cgn-shaded-sector and Sk-shaded-sector and comes out its functions through three distinct phases, namely, analysis, synthesis, and generalization. This systematic approach allows for the extraction and transformation of substantial information into a highly effective motivational strategy for P. The next steps are making a decision and performing through action. The model implies the creative application of individual professional, pedagogical, psychological, and management approaches, as well as the personal charisma of a leader when one creates or supports motivation in others.

Cgt implements selecting, organizing, and correlating processes between Cgn and Sk fields. Cgt looks for the substantial and beneficial components of both fields that can be united by the relational approach to form the MC field to perform its role.

Figure 5 denotes the ultimate and crucial interaction in the vertical between the obtained MC and the covering processes of Cgt. Cgt executes its essential goal-directed function, which is the educational and leading sense of the model. The bidirectional vectors in the vertical MC↔Cgt↔P indicate the correlations between the excerpted expedient MC, the goal-directed reasoning (Cgt), and the impact of the P on Cgt to find the desired approach to P.

As the figure shows, the achieving of the P passes through an impulse. But what exactly is the impulse? MC is an interaction between the information of Cgn and Sk fields, which means MC is power and energy (information is equivalent to energy). These interrelationships reveal that the MC content—collected, cleared, and classified—reflects the choice of the impulse, pointed at P, energetically. Consequently, the higher the level of MC, i.e., the higher the level of information energy, the more impactful the impulse.

Our project supposes three important ascertainments: (a) teachers have to choose from varying degrees of MC displayed by students; (b) while, imaginably, children in primary school have a low level of MC, and the work with them is much more, students at tertiary educational levels ought to be thought into higher skills; (c) therefore, teachers’ MC is the fundamental one, since motivational considerations for the given instructions indicate the educator’s MC level. In this sense, our model comprehends the feedback of all participants in the learning process and relates their fields of MC to each other by correlating organizer Cgt. Cgt is the core process of working through questions for feedback so that motivational competence can be described and developed.

East philosophy respects three important questions for the enlightenment of individuality: know-what, can-how, and wish-why. Generally, questions of What, How, and Why may aim to investigate the unknown learners’ MC. However, in education, the MMC emphasizes their reference to finding better or new ways to upbringing, creation, and support motivation through values and virtues. Therefore, we divided the questions into two groups according to their goals: (a) pointed to achieving the curriculum purposes (implementing the curriculum) and (b) pointed to the achievement purpose. The latter questions are oriented toward values and virtues as purposes to be achieved in education.

What- and how-questions commonly help with achieving certain goals in the learning process. However, pointing to the achievement purpose, why-questions may accomplish the much more substantial function of developing a moral value system. Usually, teachers follow what- and how-questions which are good for task implementation in class. However, the feedback by why-questions provides ample opportunity for training in morality. Teachers should pay attention to how closely related the questions, feedback, and purpose are to each other and what moral virtues can be derived from them.

For work with the MMC, initially, teachers should have basic Cgn on MC. On the foundation of that knowledge, they can realize the task if the student has the Sk to achieve the P. Meantime, teachers ought to lead learners to the human values and moral virtues at the heart of the P. By giving questions, the teacher should go as deeply as possible into the components, constituting the variables to summarize the MC. For example, when the model is being applied to a learner, variables ensue from individuality and a certain educational setting. As a result, the clarified variables may be the concrete lacks, obstacles, or needs pointed out by the respondent and perceivable by the educator. The teacher excerpts those which are of crucial importance for the individual and the seeking P. After tracking the problem, the teacher, as the conductor of the teaching process, can give instructions to lead one’s motivation due to the combination of those variable components that are expedient.

This process in education is conducted through making free conversation with precisely selected questions for feedback and proficiency, which was led by the teacher. The attention is on the respondent’s reflexive reasoning so that the way of motivation to be clarified as a path to the P. Consequently, the most functional factor of the model is the selection of the questions.

The key questions ought to make sure that the investigation process is successful. They are aimed at describing the components of the variables—lacks, obstacles, needs—in the circumstances under investigation, such as teaching and learning situation, participants, social surroundings, cultural-ethnical climate, time, topics, tasks, and purposes. The questions help participants explore what they may do to fill in the identified lacks and how to overcome the obstacles (if possible) and realize the indicated needs in the light of some moral virtues. The questions can improve the perceived ideas of motivation and further develop the proper goal-achieving ideas.

For example, you can ask students and parents key questions on lacks, referring to the teacher or lecturer:

• What are the main lacks in class?

• What is lacking in the teacher’s instructions for students’ better preparation?

• How does the teacher make you feel confident in class?

• Is the teacher always available for your questions? Why not?

• Is the communication with your teacher fruitful? Why? Why not?

• How does the teacher listen to each student—absently, carelessly, carefully, smiling?

• Does the teacher recognize the patterns of individuals’ behaviors?

• Does the teacher talk about human values and moral virtues in life?

• How many human values and virtues can you count?

• Does the teacher explain to you how you can get motivated?

• What support does the teacher give to students’ motivation?

• How does the teacher raise the students’ morale?

• Is your teacher a good pedagogue/leader/person?

Here, questions beginning with “If you were a teacher, what/how/why/which would you …?” are substantial for the feedback. They make students grow in their reasoning skills (Cgt) and express themselves more freely. This manner of seeking feedback is an appropriate two-pronged approach: teachers ascertain their students’ reasoning faculties levels and critical thinking skills. In parallel, students’ responses give convincing information about the teacher’s level of motivational skills, i.e., whether they can create, incite, stimulate, and support learners’ motivation, premised on a value system and moral virtues. Here are some examples:

“If you were a teacher, …

• What instructions would you give your students to motivate them to study?

• How would you make your students feel free to express themselves?

• How would you motivate your students to be good people?

• Why teaching students human values and virtues are important?

• Which values and virtues would you teach first? Why?

Under obstacles, we understand primarily technical and technological hindrances such as electricity, internet connection, computers, laptops, platforms, appropriate mobile devices, educational materials, and time sufficiency. Facing such conditions, which are mostly administered by officials, institutions, departments, and locally, for financial reasons., teachers can do almost nothing to solve the problems or improve the conditions in the short term.

The variable need is significant to the greatest extent. Questions about needs receive the largest responses because: (1) MMC emanates from the learner’s personality, (2) it creates a sense of talent in students, and (3) learners will fulfill their potential to express themselves, which enriches our understanding of the importance of students’ feedback about their needs. The content of needs gives perspective for the future of education.

Now, let us propose some tentative questions about the learners’ needs; however, there can be a variety of questions depending on the learners’ personalities:

• What are your three most important needs at school/university—ask questions, be confident, express yourself, overcome your shyness, give your opinion, show your talents, be free to show your opinion, and develop your critical thinking?

• What do you need to do more in class: (a) reading, writing, drawing, painting, role plays, playing funny games, and conversations about life (at school); (b) more practice in new knowledge, communicating, discussing, disputing, arguing, and developing critical thinking (mainly at university, to a possible level at school)?

• What of your abilities do you need to show in front of an audience?

• What kind of support do you need?

• Do you go in fear of the consequences of failure?

• Do you need to be more encouraged by your teacher? What for?

“Why”-questions ought to lead to the formation and strengthening of moral virtues, which may be elicited from the meaningful elements at the purpose core. “Why”-questions should be adapted to the learning task and the individual characteristics. Using social-cultural realities, a teacher can develop students’ intellectual capacity and educate them in the moral virtues of critical thinkers. About the virtues of critical thinkers, Hamby (2014) reminds us that important “emotional virtues” such as tolerance, patience, empathy, goodness, and love are basic in life.

There are a few limitations to this article: (a) The application of the model is limited to communication interactions in teaching–learning contexts that are specific to education at all levels. However, the idea of spiritual development through motivation transcends this limit and affects educational policies and policymakers; (b) The theoretical basis covered was limited to free materials available in English from different sources; (c) We announced that this article is literature-based and depends on the methodological validity of the studies and resources used. In respect to the spiritual development of human beings, there are no limitations to models, methods, and approaches.

The contributions of the model will be unfolded in several points.

• We expanded the general concept of motivational competence with a focus on a value system and moral criteria. The model proposes a new trend of motivational competence development toward human values and virtues in its foundation. The reason for this is the recent tendency toward weakening students’ motivation more likely because of a lack of values and virtues on which they may convincingly justify themselves.

• We laid the two systems of values and virtues in the essence of motivational argumentation. So, they fill in the indicated lack that we found in motivation learning theories and research studies. These two systems can bring together cognition and reasoning skills and focus them on spirituality.

• Since every process in education is a reflection of educational policy, the model upholds the opposite idea as well: educational policies ought to make profound and purposeful changes in the realm of spiritual education incited by the rank-and-file employees in the hierarchy of education.

• The above motives are unified by a spirituality which affects the young generation’s ability to make solidly reasoned decisions. A clear awareness of the moral value gives a sense of right and the individual can convincingly manifest the decision in their behavior. Reasoning faculties and effective critical thinking build the individual into a citizen of society.

• The model of motivational competence has a non-limited demographic focus on education—from kindergarten, preschool, school, and university, with perspective in life.

Our concern is whether methods within the curriculum disciplines are adequate for the problems of morality and human values. This persists as a concern for society and an obligation for educational policies. However, the model itself is an approach to values and moral principles in education aimed at the final act—moral and valuable behavior. MMC relies on the premise that a human being has innate inclinations and the inner ability to acquire moral virtues and live due to values that can provide spiritual prosperity.

Over the years, learners have been established as “impersonal material” in the educational system. Their adaptation to the educational doctrine has been a process of internal emigration for an individual from themselves. Here, structured model of motivational competence can help learners come back to their individualities through educational and communicative procedures for motivation based on values and virtues. They lead to natural and inherent emotional feedback and critical thinking. Moreover, we consider the recovery and in-depth study of the ethics discipline as a sociocultural and moral imperative for education in the 21st century. The emphasis on the value system and moral criteria is paramount in the present time, which is saturated with cruelty, war, and murder.

Teaching and learning human values and moral virtues for motivation can enable an individual in vital aspects: (a) to be aware of social facts, (b) to compare and reasonably assess through critical thinking, (c) to demonstrate abilities to cogitate on human values and virtues and embody them into the argumentative part of the motivation, (d) to make well-reasoned decisions, and (e) to build motivated behavior. Competence in the value system and moral criteria and the mental process of critical thinking and making decisions develop self-identity, increase self-awareness, and enhance a person’s spiritual growth. The acquisition of moral qualities such as responsibility, empathy, compassion, and goodness provides the basis for the success rate in society.

The MMC is a functional model that can make a genuinely innovative contribution to the morality and humanization of education. However, the question that worried us is: Would teachers appreciate an approach to the fulfillment of teaching and learning processes in motivational competence that involved not only just traditional teaching but also their personal growth in morality and motivational competence, i.e., cognition, cogitation, communicative skills, and reasoning abilities? Future research that can determine the trend is forthcoming.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

FS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Discussion, Writing – original draft preparation, Visualization. EG: Conceptualization, Methodology, Discussion, Writing – original draft preparation, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Al-Harthy, I. S. (2016). Contemporary motivation learning theories: a review. Int. J. Learn. Manag. Syst. 4, 99–117. doi: 10.18576/ijlms/040205

Artino, A. R. Jr. (2012). Academic self-efficacy: from educational theory to instructional practice. Persp. Med. Educ. 1, 76–85. doi: 10.1007/s40037-012-0012-5

Artino, A. R., Holmboe, E. S., and Durning, S. J. (2012). Can achievement emotions be used to better understand motivation, learning, and performance in medical education? Med. Teach. 34, 240–244. doi: 10.3109/0142159x.2012.643265

Barnett, R. (1997). Higher education: A critical business. McGraw-Hill Education (UK). Available at: http://books.google.ie/books?id=pWpEBgAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=Higher+Education:+A+Critical+Business&hl=&cd=1&source=gbs_api

Beach, D. (2004). The role of Socratic questioning in thinking, teaching, and learning. Available at: http://www.criticalthinking.org?resources/articles/the-role-socraatic-questioning-ttl.shtml

Benesch, S. (1999). Thinking critically, thinking dialogically. TESOL Q. 33, 573–580. doi: 10.2307/3587682

Bieg, S., Beckes, S., and Mittag, W. (2011). The role of intrinsic motivation for teaching, teachers’ care and autonomy support in students’ self-determined motivation. J. Educ. Res. Online 3, 122–140. doi: 10.25656/01:4685

Boström, L., and Bostedt, G. (2020). What about study motivation? Students´ and teachers’ perspectives on what affects study motivation. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 19, 40–59. doi: 10.26803/ijlter.19.8.3

Boud, D., and Molloy, E. (2013). Rethinking models of feedback for learning: the challenge of design. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 38, 698–712. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2012.691462

Brendel, W. T., and Hankerson, S. (2022). Hear no evil? Investigating relationships between mindfulness and moral disengagement at work. Ethics Behav. 32, 674–690. doi: 10.1080/10508422.2021.1958331

Brookfield, S. D. (2012). Teaching for critical thinking. John Wiley & Sons. Available at: http://books.google.ie/books?id=r7DG2e41pZMC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Teaching+for+Critical+Thinking+-+Tools+and+Techniques+to+Help+Students+Question+Their+Assumptions&hl=&cd=1&source=gbs_api

Broussard, S. C., and Garrison, M. E. B. (2009). The relationship between classroom motivation and academic achievement in elementary-school-aged children. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 33, 106–120. doi: 10.1177/1077727x04269573

Carless, D. (2018). Feedback loops and the longer-term: towards feedback spirals. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 44, 705–714. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2018.1531108

Carless, D., and Boud, D. (2018). The development of student feedback literacy: enabling uptake of feedback. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 43, 1315–1325. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354

Carless, D., Salter, D., Yang, M., and Lam, J. (2011). Developing sustainable feedback practices. Stud. High. Educ. 36, 395–407. doi: 10.1080/03075071003642449

Chugh, D., Kern, M. C., Zhu, Z., and Lee, S. (2014). Withstanding moral disengagement: attachment security as an ethical intervention. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 51, 88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2013.11.005

Cory, S., and Hernandez, A. (2014). Moral disengagement in business and humanities major: an explanatory study. Res. High. Educ. J. 23, 1–11.

Cottrell, S. (2005). Critical thinking skills. Palgrave Macmillan. Available at: http://books.google.ie/books?id=QYOBQgAACAAJ&dq=Critical+Thinking+Skills:+Developing+effective+analysis+and+argument&hl=&cd=3&source=gbs_api

Cuban, L. (1984). Policy and research dilemmas in the teaching of reasoning: unplanned designs. Rev. Educ. Res. 54, 655–681. doi: 10.2307/1170178

Davies, M. (2015). “A model of critical thinking in higher education” in Higher education: Handbook of theory and research. ed. L. W. Paulsen, vol. 30 (Cham: Springer).

Deci, L., and Ryan, M. (2012). “Motivation, personality, and development within embedded social contexts: an overview of self-determination theory” in Oxford handbook of human motivation. ed. M. Ryan (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 85–107.

Detert, J. R., Treviño, L. K., and Sweitzer, V. L. (2008). Moral disengagement in ethical decision making: a study of antecedents and outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 93, 374–391. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.93.2.374

Dweck, C. S., and Molden, D. C. (2017). “Mindsets: their impact on competence motivation and acquisition” in Handbook of competence and motivation: Theory and application. eds. A. J. Elliot, C. S. Dweck, and D. S. Yeager (New York: The Guilford Press), 135–154.

Eccles, J. S. (2005). “Subjective task value and the Eccles et al. model of achievement-related choices” in Handbook of competence and motivation. eds. A. J. Elliot, C. S. Dweck, and D. S. Yeager (New York: The Guilford Press).

Elliot, A. J., and Dweck, C. S. (2005). “Competence and motivation: competence as the Core of achievement motivation” in Handbook of competence and motivation. eds. A. J. Elliot, C. S. Dweck, and D. S. Yeager (New York: The Guilford Publications), 3–12.

Elliot, A. J., and Dweck, C. S. (2017). Handbook of competence and motivation. 2nd Edn. New York: Guilford Publications.

Etxebarria, I., Ortiz, M. J., Apodaca, P., Pascual, A., and Conejero, S. (2015). Pride as moral motive: moral pride and prosocial behaviour/El orgullo como motivación moral: orgullo moral y conducta prosocial. Infancia Y Aprendizaje 38, 746–774. doi: 10.1080/02103702.2015.1076267

Facione, P. A. (2000). The disposition toward critical thinking: its character, measurement, and relation to critical thinking skills. Informal Logic 20, 61–84. doi: 10.22329/il.v20i1.2254

Facione, P. A. (2023). Critical thinking: what it is and why it counts – insight assessment. Available at: https://insightassessment.com/iaresource/critical-thinking-what-it-is-and-why-it-counts/

Ferreira, M., Cardoso, A. P., and Abrantes, J. L. (2011). Motivation and relationship of the student with the school as factors involved in the perceived learning. Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 29, 1707–1714. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.416

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., and Archer, W. (2001). Critical thinking, cognitive presence, and computer conferencing in distance education. Am. J. Dist. Educ. 15, 7–23. doi: 10.1080/08923640109527071

Gehlbach, H., Robinson, C. D., Finefter-Rosenbluh, I., and Benshoof, C. And Schneider, J. (2018). Questionnaires as intervention: can taking a survey increase teachers’ openness to student feedback survey? Educ. Psychol., 38, 350–367. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2017.1349876

Gelder, T. V. (2005). Teaching critical thinking: some lessons from cognitive science. Coll. Teach. 53, 41–48. doi: 10.3200/ctch.53.1.41-48

George, R. (2014). Moral disengagement: an explanatory study of predictive factors for digital aggression and cyberbullying (order no. 3691153) [doctoral dissertation]. Denton, TX: University of North Texas.

Gopalan, V., Bakar, J. A. A., Zulkifli, A. N., Alwi, A., and Mat, R. C. (2017). A review of the motivation theories in learning. AIP Conf. Proc. 1891:20043. doi: 10.1063/1.5005376

Hamby, B. (2014). The virtues of critical thinkers [doctoral dissertation]. Hamilton: McMaster University.

Han, H. (2014). Analysing theoretical frameworks of moral education through Lakatos’s philosophy of science. J. Moral Educ. 43, 32–53. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2014.893422

Han, H. (2015). Purpose as a moral virtue for flourishing. J. Moral Educ. 44, 291–309. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2015.1040383

Hattie, J., and Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 77, 81–112. doi: 10.3102/003465430298487

Heard, J., Scoular, C., Duckworth, D., Ramalingam, D., and Teo, I., (2020). Critical thinking: definition and structure. Australian Council for Educational Research. Available at: https://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1039&context=ar_misc

Hovland, I. (2005). Successful communication. A toolkit for researchers and civil society organisations, RAPID (research and policy in development). London: Overseas Development Institute.

Hunt, F. (2007). Communications in Education. University of Sussex, Centre for International Education. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED501789.pdf (Accessed April 4, 2023)

Jansen, J. D. (2002). Political symbolism as policy craft: explaining non-reform in sought African education after apartheid. J. Educ. Policy 17, 199–215. doi: 10.1080/02680930110116534

Keller, J. M. (2010). Motivational Design for Learning and Performance. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media.

Kingsford, J. M., Hawes, D. J., and de Rosnay, M. (2021). The development of moral shame indicates the emergence of moral identity in middle-childhood. J. Moral Educ. 51, 422–441. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2021.1898936

Krettenauer, T., Campbell, S., and Hertz, S. (2013). Moral emotions and the development of the moral self in childhood. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 10, 159–173. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2012.762750

Kristjánsson, K. (2021). Awaiting the owl of Minerva: some thoughts on the present and future of moral education. J. Moral Educ. 50, 115–121. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2021.1907074

Kuhn, D. (1999). A developmental model of critical thinking. Educ. Res. 28, 16–46. doi: 10.2307/1177186

Lahey, J. (2016). To help students learn, engage the emotions. Well. Available at: https://archive.nytimes.com/well.blogs.nytimes.com/2016/05/04/to-help-students-learn-engage-the-emotions/

Lai, E. R. (2011). Critical thinking: a literature review. Pearson Available at: http://www.johnnietfeld.com/uploads/2/2/6/0/22606800/motivation_review_final.pdf (Accessed December 21, 2023)

Lipnevich, A. A., Berg, D., and Smith, J. K. (2016). “Toward a model of student response to feedback” in Handbook of human factors and social conditions in assessment. eds. G. T. L. Brown and L. R. Harris (New York: Routledge), 169–185.

Lipnevich, A. A., and Panadero, E. (2021). A review of feedback models and theories: descriptions, definitions, and conclusions. Front. Educ. 6:720195. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.720195

Ljubetić, M. (2012). New competences for the pre-shool teacher: a successful response to the challenges of the 21st century. World J. Educ. 2:82. doi: 10.5430/wje.v2n1p82

Makulova, A. T., Alimzhanova, G. M., Bekturganova, Z. M., Umirzakova, Z. A., Makulova, L. T., and Karymbayeva, K. M. (2015). Theory and practice of competency-based approach in education. Int. Educ. Stud. 8:183. doi: 10.5539/ies.v8n8p183

Malley-Morrison, K., Oh, D. Y., Wu, T., and Zaveri, T. (2009). Moral Disengagement and Engagement. Beliefs Values 1, 151–167. doi: 10.1891/1942-0617.1.2.151