- Arabic Language Institute to Non-native Speakers, Teachers Preparing and Training Department, Islamic University of Madinah, Medina, Saudi Arabia

Learning the Arabic language through gamified methods is beneficial, particularly for beginners. Gamification provides an enjoyable and challenging experience for the learners, motivating them to become committed and participate in the classroom activity. The students develop a more competitive spirit and anticipate their chances of achieving high scores for each game level and ranking high against fellow learners. Game elements such as feedback and audio pronunciations assist in user engagement with the teacher and other learners. This systematic literature review critically synthesizes past literature to create an understanding of the application and effectiveness of gamified learning strategies for Arabic language learning. PRISMA technique was used to conduct a systematic review, and after final scrutiny, 15 articles were shortlisted for review. The findings suggested that gamification improves learner motivation, engagement, and achievement in mastery of Arabic vocabulary and grammar among non-native speakers. The degree of motivation is influenced by the teacher’s perception, attitude, enthusiasm, and commitment to gamified learning strategies. The findings of this systematic review can help language instructing institutions to emphasize gamification to enhance the motivation of learners and increase their learning abilities. Moreover, it can be helpful for instructors of the Arabic language, and they can realize the importance of gamification in teaching Arabic to non-native speakers.

1 Introduction

Learning a second language is considered an unpleasant and difficult task for many learners. It requires mastery of vocabulary and reading, speaking, and writing skills (Rieder-Bünemann, 2012). Learning the grammar, vocabulary, and speaking skills of a new language is essential for effective mastery and use of the language. Some tasks, such as language translation, are time-consuming for learners and challenging for teachers. Teachers use grammar and vocabulary to assist learners in reading, speaking, and writing the language in the learning process (Arttırmak et al., 2018). They adapt and implement innovative ways to motivate and engage individuals to learn definitions, context, and vocals of the new language. Common techniques and methods applied in teaching the second language have involved dramatization and illustrative drawings and pictures (Habók and Magyar, 2018).

Many English-speaking countries in Europe and North America have succeeded in creating programs to promote learning of other languages beyond the dominant language and test learners’ proficiency. Similarly, there has been a paradigm shift from single to multilingual languages in many Arabic countries (Alshahrani, 2019). Native Arabic speakers learn English, Spanish, or any other second language, while non-natives learn Arabic as their second language (Al Hejaili and Newbury, 2023). In modern classrooms, students learn languages that are different from their dominant mother tongue.

Arabic as a second language has received significant attention and recognition in the international community, and more countries acknowledge its importance for international communication (Moghazy, 2021). According to Moghazy (2021) the UN accepts and endorses Arabic as a communication language for UN summits in Arabic-speaking countries. Given that Arabic is given the same recognition status as other dominant languages such as English, Spanish, French, and Chinese, there has been increased interest from non-native speakers in learning the language (Najjar, 2020). Learning efficiency and teaching Arabic to non-speakers are affected by many factors, including teaching methods, the teacher, the program, and the language lab (Dajani et al., 2014). Various studies have examined the teaching and acquisition of Arabic as a second language for non-natives. The findings suggest the need to leverage new technology to induce the learning environment and empower learners’ productivity, motivation, and engagement in the learning process (Sahrir and Alias, 2011; Al-Bulushi and Al-Issa, 2017; Ghani et al., 2019; Abdelhamid et al., 2023). For example, Noor et al. (2023) and Al-Bulushi and Al-Issa (2017) suggested integrating games into classrooms to improve learner’s participation and motivation levels when learning the Arabic language.

Non-natives learning the Arabic language face challenges, suggesting a lack of motivation (Zeroual et al., 2018). This notion is widely corresponded by past studies suggesting low proficiency, particularly in Arabic reading and speaking skills, among non-native speakers (Mokhtar, 2020). The lack of motivation and poor proficiency are indications of the difficulties associated with mastering the Arabic language. Noor et al. (2023) also noted that the traditional methods used to teach the Arabic language were less effective and often demotivated learners. This has had a negative impact on the learner’s Arabic language achievement and proficiency. Learners’ attitudes and motivation are important factors that drive their interest and participation in the Arabic language learning process. To create a positive perception and help non-speakers learn Arabic, gamification is the best approach (Zeroual et al., 2018).

The concept of gamification has gained significant attention in the field of education as an alternative learning method. Gamification refers to the utilization of elements of game design in a non-game environment to enhance engagement, enjoyment, and experiences (Sahrir and Alias, 2011; Al-Bulushi and Al-Issa, 2017; Abdelhamid et al., 2023). It involves integrating game mechanics and dynamics in non-game environments such as classroom or home environments. According to Deterding et al. (2011), gamification was first introduced in 2010 to describe the application of game design elements in non-game environments. Zeroual et al. (2018) perceived gamification as a novel IT development that leverages elements of game design, such as points and badges, to guide user behavior. Elements of the game describe the mechanics of the game that influence user participation and engagement, and they may differ from one game to another (Abdelhamid et al., 2023). The user’s desire to play and master the game is essential in raising their motivation and engagement levels. Tomaselli et al. (2015) noted that the challenge of overcoming the game’s obstacles, mastering its dynamics, and completing it in a specific period was important in improving user engagement.

Teaching and learning through gamification is a collaborative and enjoyable process. Implementing gamification in classrooms and other learning environments enhances learners’ motivation and engagement in the learning process. Teachers gamify the learning process to facilitate desirable changes in learners’ behavior (Mazer and Al-Ajlouni, 2023). Yildirim (2017) emphasized that gamified strategies can be integrated into the classroom, learning process, or curriculum, which may positively impact learners’ achievement and motivation. Shahri et al. (2019) corresponded these findings, arguing that gamification improved user understanding and retention of the game dynamics. Riwanda et al. (2021) found that gamification is implemented to resolve learning problems by leveraging game mechanics and components in the learning context to empower learners’ productivity, engagement, and motivation.

Gamification has grown rapidly with the increasing growth of smartphone and technology adoption (Zeroual et al., 2018). In 2019 the global population spent around 3.32 billion for playing video games (Cabeza-Ramírez et al., 2021). Research has shown that gamification has been used in business (Gears and Braun, 2013; Wünderlich et al., 2020), health (Johnson et al., 2016), and education (Kiryakova et al., 2014; Majuri and Hamari, 2018; Hakak et al., 2019; Luo, 2023). The application of gamification in education enhances the learning outcomes, motivations, and engagement of students in the learning process (Tan and Hew, 2016).

Substantial studies have explored the application and effectiveness of gamification in teaching and learning the Arabic language (Jasni et al., 2019; Kotob and Ibrahim, 2019). The studies have leveraged different research designs to examine how teachers in different countries integrated the elements and components of gamification in the classroom learning process to enhance learners’ motivation and engagement in learning the Arabic language. The research has generated huge empirical evidence for understanding the effectiveness of gamification methods in teaching the Arabic language to non-native speakers (Ghani et al., 2019; Kotob and Ibrahim, 2019; Saleh et al., 2022). This study will review peer-reviewed articles and journals from the past 10 years to examine the application of gamification in learning the Arabic language by non-native speakers.

Saudi Arabia is gaining significant attention from businesses around the globe. Moreover, many industries in the country are employing people from different nationalities who are unable to speak Arabic. Therefore, many non-natives are highly interested in learning the Arabic language to cope with the challenges that they may face at their workplace. However, Arabic is generally considered the most difficult language to be understood by non-natives; thus, language instructors always face difficulties while teaching language. The biggest challenges faced by them are the lack of motivation and engagement of learners. These challenges can be countered by gamification. Therefore, this systematic review has focused on highlighting the application of gamification in learning the Arabic language by non-native speakers.

2 Methodology

This systematic literature review (SRL) aligns with the interpretivism paradigm and inductive reasoning (Campbell, 2014). The approach involves identifying, selecting, and critically appraising relevant research to address the research question. This study has a clear protocol, highlighting the inclusion and exclusion criteria, search terms and keywords, and review process. Explicit and systematic methods were used to locate and retrieve studies related to gamification in learning the Arabic language for non-native speakers. Empirical evidence from the relevant studies selected based on the inclusion criteria was critically reviewed and summarized to address the research question (Moher et al., 2009). Systematic methods reduce researcher bias, providing reliable findings that can be generalized.

2.1 Search strategy

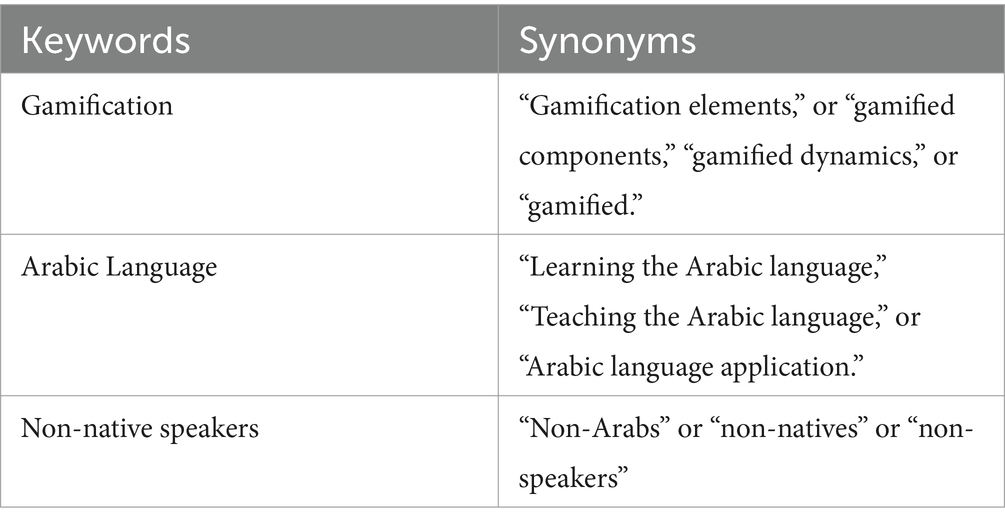

Searching for relevant data is always a difficult task; thus, it is most important to finalize the search strategy after finalizing the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Search strategy development is the second important step in the formulation of any systematic review. PRISMA checklist also highlighted that it is essential to design a search strategy so that relevant information can be entertained. In this systematic review, first, the list of databases was developed, and then they were systematically evaluated for shortlisting peer-reviewed articles published in reputed journals. The relevant databases shortlisted for the study include Google Scholar, JSTOR, CORE, DOAJ, Science Direct, ERIC, ProQuest, SSRN, Master Journal List (MJL), Scopus (SJR), and EBSCO. Second, to search for appropriate data for review, an additional search was conducted to sort the most related articles published in renowned publishers, including Frontiers, MDPI, Elsevier, Academic Pass, Sage, Hindawi, T&F, Emerald, Allen Press, IGI, Wiley, Oxford University Press, Inderscience, Walter De Gruyter, Cambridge University Press, Routledge, and Brill. The whole process of searching took more than 2 months, as no assistance was acquired. The process started in mid-May and ended in July 2023. To search for the most relevant data, a perfect search string was designed, and it was modified according to the requirements of the publisher or database. The keywords in the search string include Arabic learning, Arabic learning by non-natives, Arabic as a second language, gamification and Arabic learning, gamification and non-native Arabic learners, and the latest techniques in Arabic learning by non-native speakers. Multiple search terms were combined to narrow the search and increase the accuracy of the search outcomes. There are many different artificial intelligence tools, such as “Research Rabbit,” which can assist in searching, but no AI tool was used to retain consistency and quality. The comprehensive search strategy provided a huge volume of data, and to process it, the exclusion and inclusion criteria were adjusted again. The whole process of search followed the PRISMA guidelines. The details of exclusion and inclusion criteria are given in Table 1.

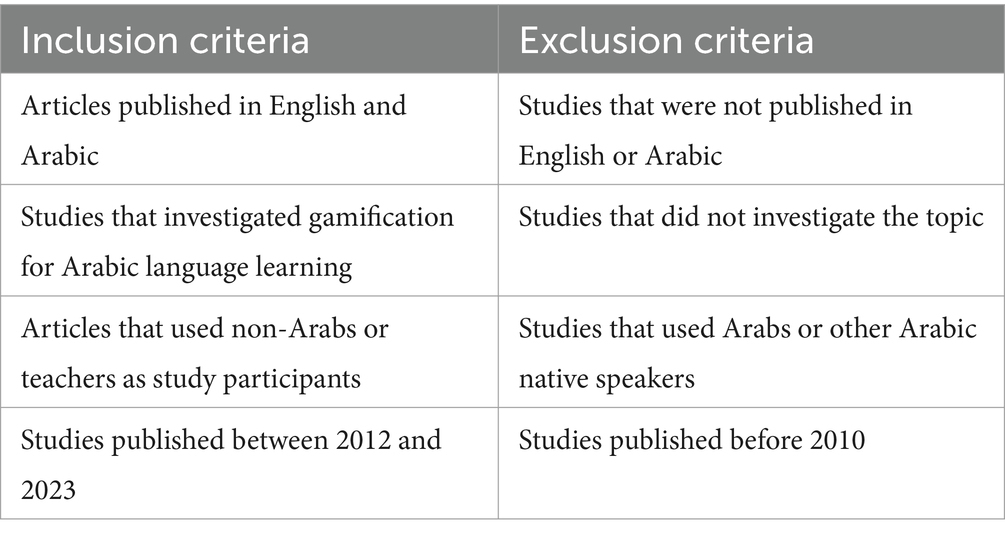

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed, highlighting the predefined factors that determined studies to be included and excluded from the review. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are important for any systematic review. The PRISMA checklist also significantly emphasizes finalizing the inclusion and exclusion criteria before starting the data screening. Thus, to formulate a perfect initial screening strategy, an expert librarian and two Arabic language instructors (i.e., teaching Arabic to non-native speakers) were consulted, and based on their guidelines, I developed a plan to include and exclude the data for initial screening. Following the plan, the aim was to reduce the chances of irrelevant data and maximize the chances of including research publications from renowned publishers/sources. It was finalized to consider only the latest premium quality articles (i.e., published in reputed journals by renowned publishers); thus, for inclusion, the articles published in the English language (i.e., qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method) between 2010 and 2023 were shortlisted for the first screening. In the initial/first screening, it was decided to exclude all the conceptual, descriptive, and literature review articles, as they are never specific to a single theme. Moreover, only the articles on behavioral factors linked to game-based learning by non-native Arabic learners and articles that used non-Arabs or teachers as study participants were included. Furthermore, the research articles focusing on any other language learners were excluded. In addition, the studies published in any other language than English and Arabic, studies focusing on multiple themes, articles that used Arabs or other Arabic native speakers, and articles published before 2011 and after 2023 were not excluded. The details of exclusion and inclusion criteria are given in Table 2.

2.3 Assessment of studies’ quality

Quality assessment was done using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses. Two independent reviewers assessed all domains, including whether the sample was clearly defined, ensuring a detailed explanation of subjects and settings, analyzing the standards and criteria, findings cofounding factors, analyzing the strategies to deal with confounding factors stated, examining the outcomes measured validly and reliably, and checking the appropriate statistical analysis used. Each risk of the bias point obtains a “low,” “some concerns,” or “high” risk of bias.

2.4 Data extraction

The keywords and synonyms developed were entered into electronic databases, including IEEE Xplore Digital Library, Scilit, and ACM Digital Library to locate and retrieve relevant peer-reviewed journal articles.

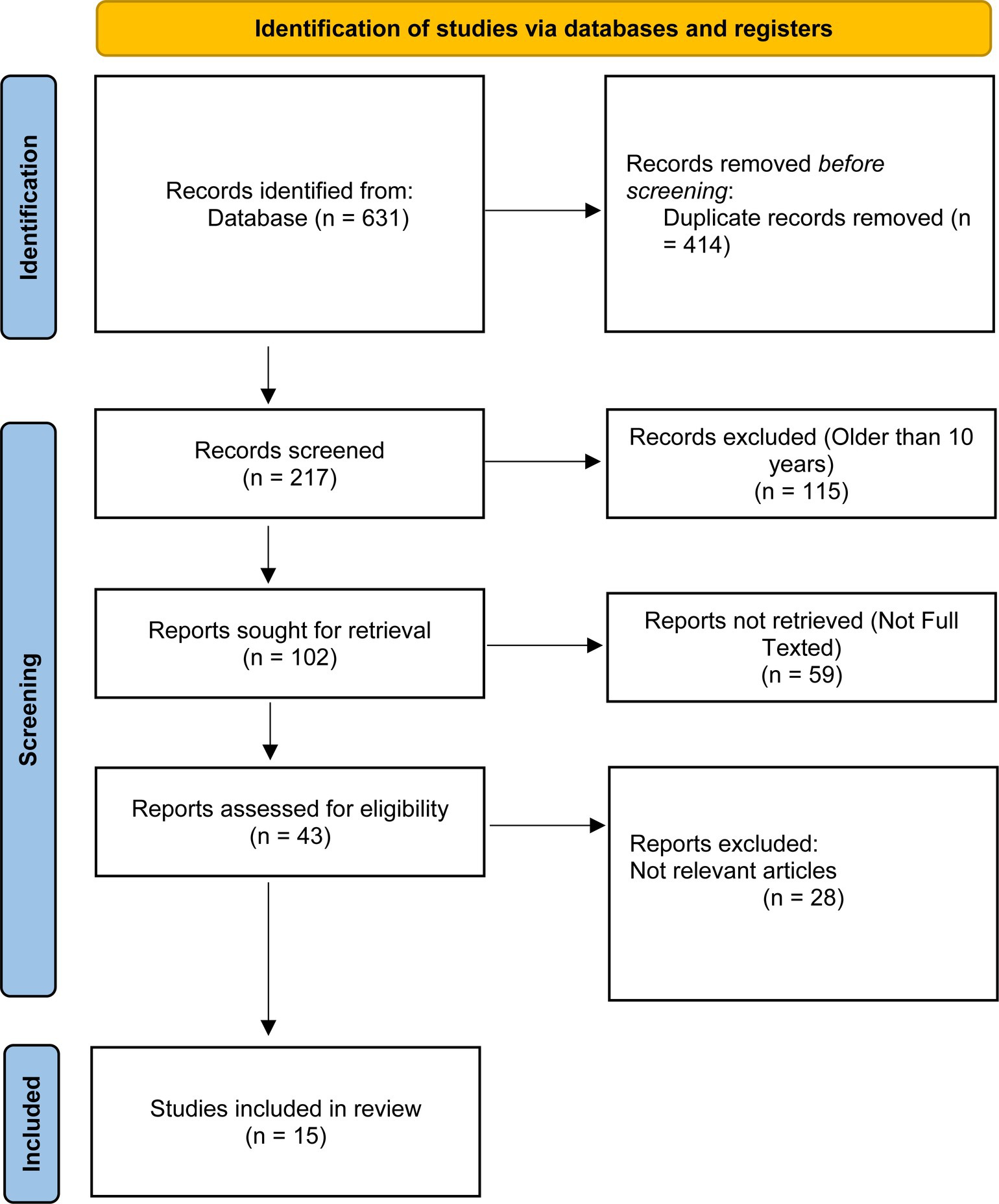

Figure 1 shows the search and selection process where the initial search resulted in 631 articles. Their titles and abstracts were examined to determine their relevance and eligibility for inclusion in the review, where 414 articles did not meet the inclusion criteria. Further scrutiny of the texts and content of the remaining articles led to the removal of 215 articles because they did not meet the publication date criteria or did not clearly indicate their research design and study results. Another 59 articles that did not meet the quality of content criteria were also excluded. The final sample had 15 articles. The texts and content of articles in the sample were critically analyzed to identify common themes that described gamification for Arabic language learning.

3 Results

The review aimed to create insights into the utilization and effectiveness of gamification in Arabic language learning for non-native speakers. Therefore, the emphasis was mainly paid to literature focusing on gamification in learning the Arabic language. The results highlighted that two focused on learners’ behaviors and attitudes toward online games for learning the Arabic language, four on learning via mobile games, five on classroom-based games, and four on online games. Previously, there was a paucity of research focusing on all these themes together; thus, this review emphasized indicating all the relevant studies that partially or fully focused on all themes.

3.1 Study characteristics

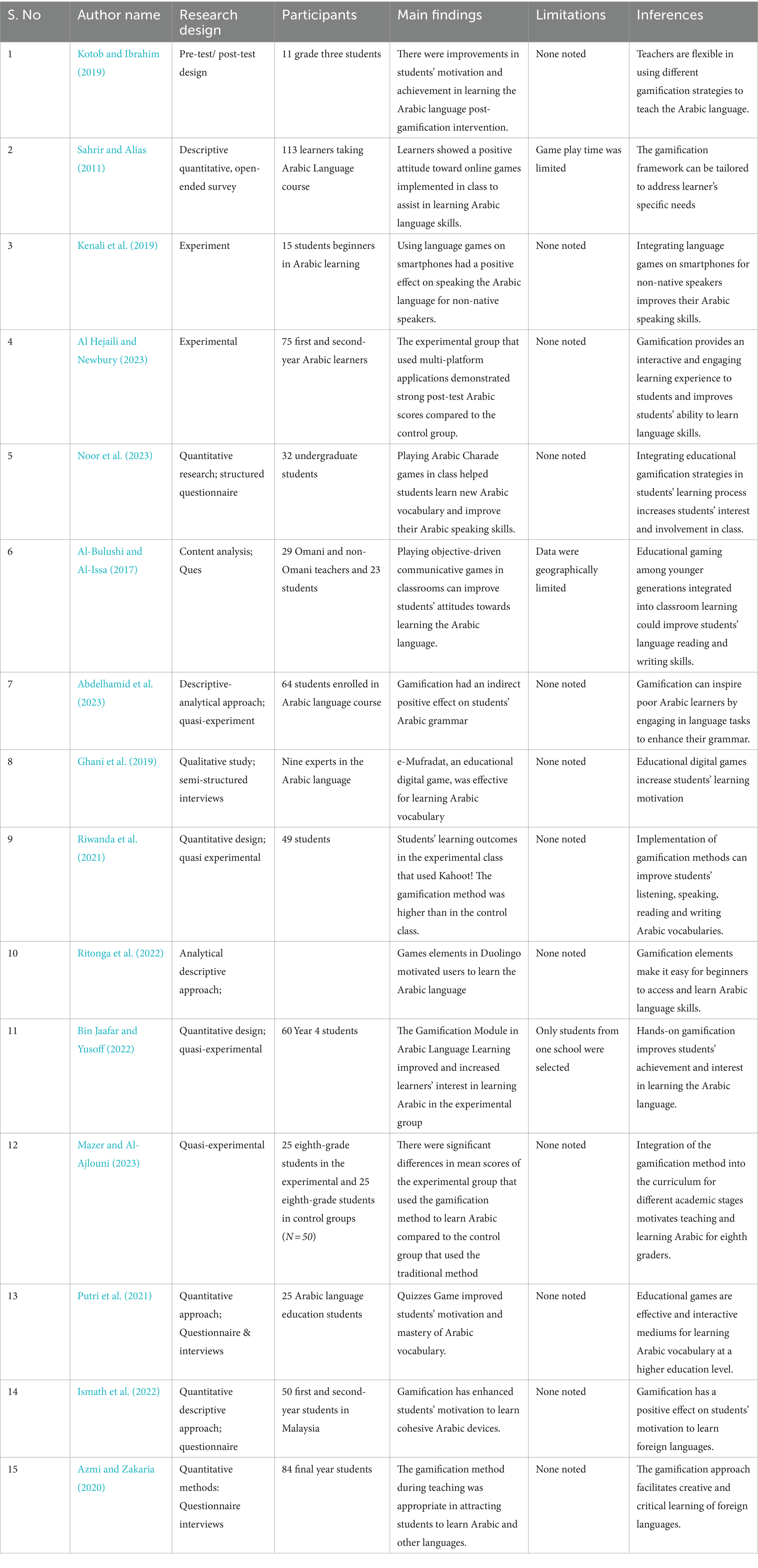

The review has highlighted different characteristics of studies, including year of publication, research design, participants, main findings, limitations, and inferences. These characteristics are explained and classified in Table 3.

This study aimed to create insights into the utilization and effectiveness of gamification in Arabic language learning for non-native speakers. Table 3 shows a summary of the study characteristics and key findings.

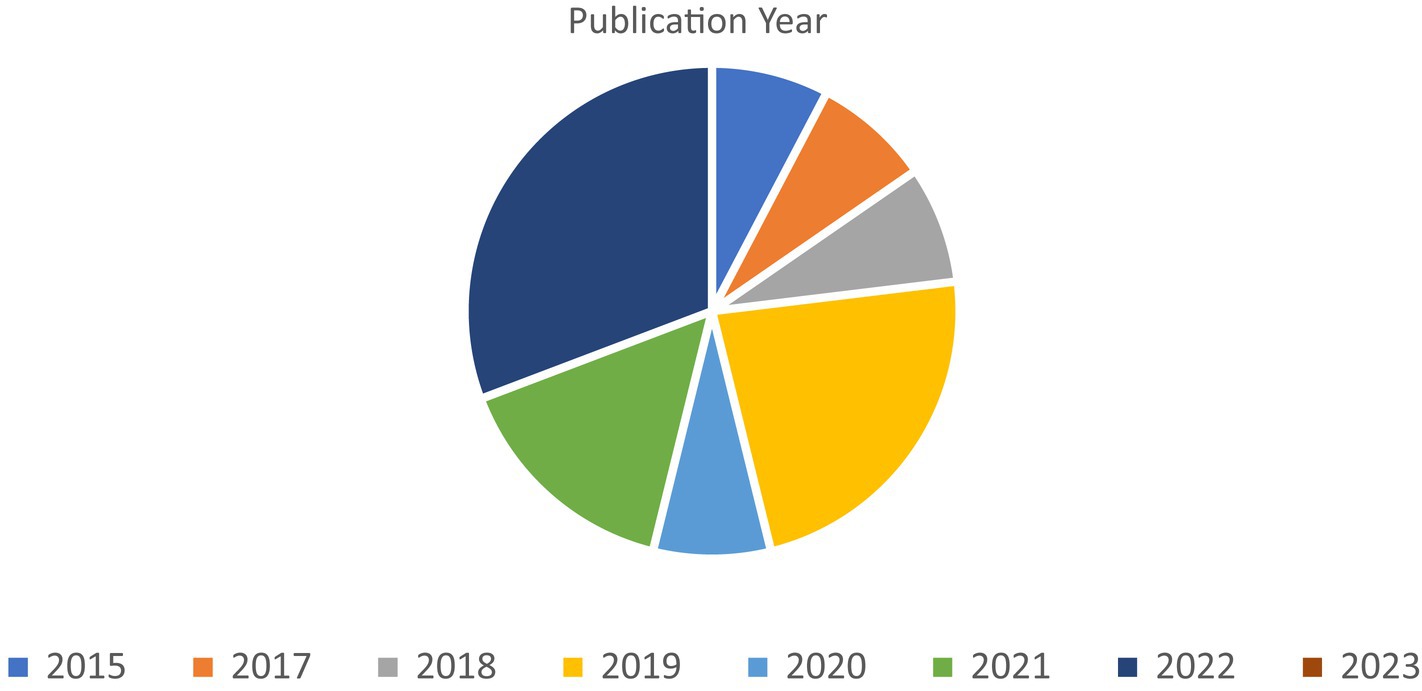

3.1.1 Year published and country of origin

Among the 15 articles considered for the review, one article was published in 2011 (1/15), one in 2017 (1/15), one in 2018 (1/15), three in 2019 (3/15), one in 2020 (1/15), two in 2021 (2/15), four in 2022 (4/15), and two in 2023 (2/15). Most of the studies did not focus on any single country; thus, the review has not classified the country of origin. The details of the year of publication are also given in Figure 2.

3.1.2 Focus, aim, and approach

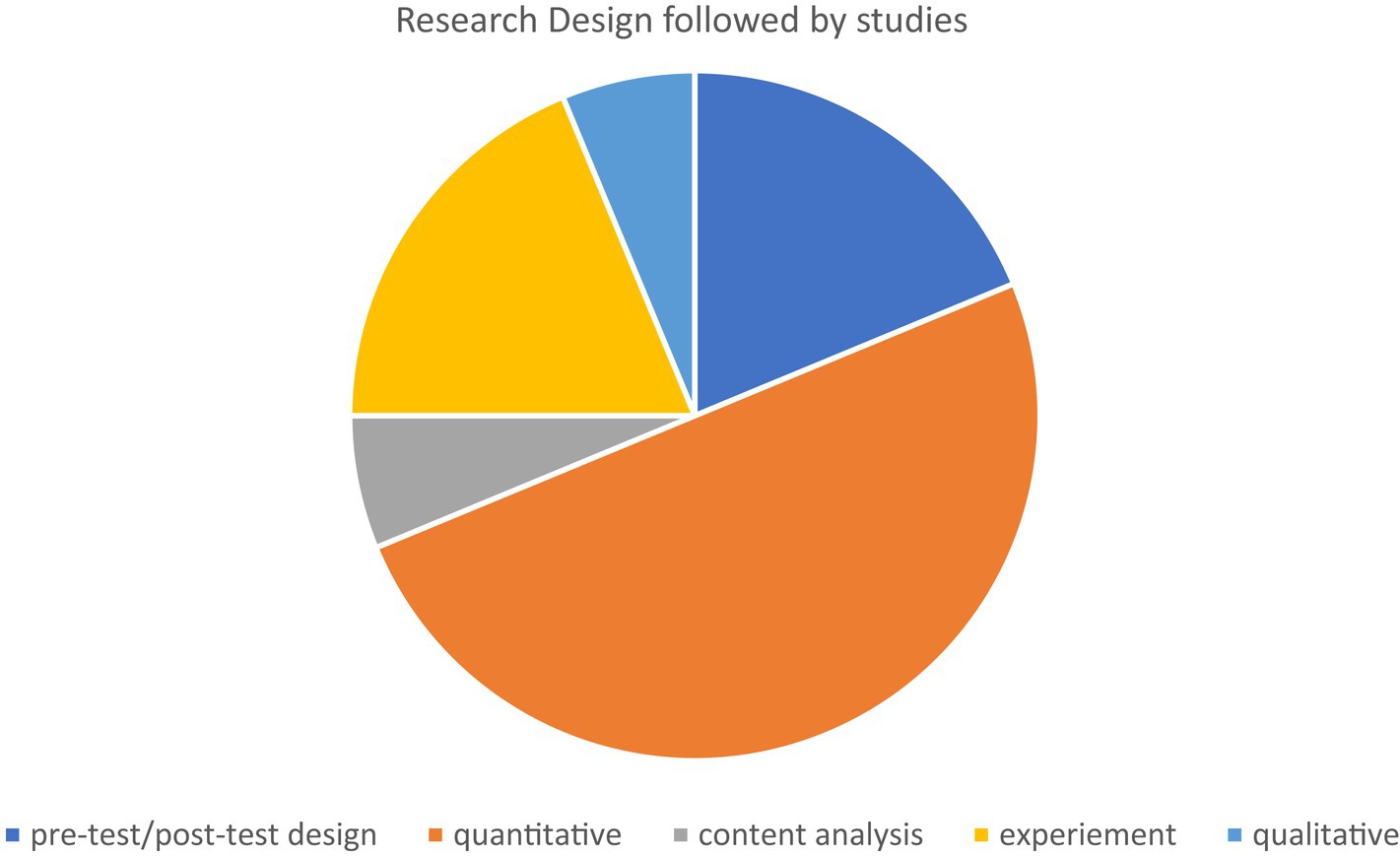

All six studies focused on game-based Arabic language learning, but the target group and research design of the studies were different depending on the nature. They followed pre-test/post-test design (i.e., 3/15) (Kotob and Ibrahim, 2019; Ritonga et al., 2022; Abdelhamid et al., 2023), quantitative approach (i.e., 8/15) (Sahrir and Alias, 2011; Yan Mei et al., 2018; Azmi and Zakaria, 2020; Putri et al., 2021; Riwanda et al., 2021; Bin Jaafar and Yusoff, 2022; Ismath et al., 2022; Noor et al., 2023), content analysis (i.e., 1/15) (Al-Bulushi and Al-Issa, 2017), experiment (i.e., 3/15) (Kenali et al., 2019; Al Hejaili and Newbury, 2023; Mazer and Al-Ajlouni, 2023), and qualitative approach (i.e., 1/15) (Ghani et al., 2019). The details of the research design are also shown in Figure 3.

Two out of 15 focused on learners’ behaviors and attitudes toward online games for learning the Arabic language (Sahrir and Alias, 2011; Kotob and Ibrahim, 2019). Others focused on learning via mobile games through quizzes (Ghani et al., 2019; Kenali et al., 2019; Ismath et al., 2022; Mazer and Al-Ajlouni, 2023), classroom games (Al-Bulushi and Al-Issa, 2017; Azmi and Zakaria, 2020; Riwanda et al., 2021; Ritonga et al., 2022; Noor et al., 2023), and online games (Yan Mei et al., 2018; Putri et al., 2021; Bin Jaafar and Yusoff, 2022; Ritonga et al., 2022).

3.1.3 Study design and sample

Among the 15 studies considered for review, eight were quantitative, three were experimental, one qualitative, one content analysis-based research, and two focused on pre-post testing. The number of participants (i.e., students of different grades) ranged from 11 to 84, but one study focused on 29 teachers and 23 students.

3.1.4 Outcomes

The outcomes of the studies revealed that gamification can accelerate the language learning process. It can help the teachers and students. Furthermore, the outcomes highlighted that teachers are flexible in using different gamification strategies to teach the Arabic language (Kotob and Ibrahim, 2019), the gamification framework can be tailored to address learner’s specific needs (Sahrir and Alias, 2011), the integration of language games on smartphones for non-native speakers improves their Arabic speaking skills (Kenali et al., 2019), gamification provides an interactive and engaging learning experience to students and improves students’ ability to learn language skills (Al Hejaili and Newbury, 2023), and the integration of educational gamification strategies in students’ learning process increases students’ interest and involvement in class (Noor et al., 2023). Moreover, the outcomes revealed that educational gaming among younger generations integrated into classroom learning could improve students’ language reading and writing skills (Al-Bulushi and Al-Issa, 2017), gamification can inspire poor Arabic learners by engaging in language tasks to enhance their grammar (Abdelhamid et al., 2023), educational digital games increase students’ learning motivation (Ghani et al., 2019), and implementation of gamification students’ listening, speaking, reading, and writing Arabic vocabularies (Riwanda et al., 2021). In addition, the studies also reported that gamification elements make it easy for beginners to access and learn Arabic language skills (Bin Jaafar and Yusoff, 2022; Ritonga et al., 2022; Mazer and Al-Ajlouni, 2023).

4 Discussion

In education, different gamified strategies are increasingly being integrated into the learning process to aid in learning languages. Teachers have considered serious games, phone-based games, and other 3D game simulations to teach languages in classrooms. In this regard, three concepts were common in the review. Gamification refers to the integration of games into a non-gamified environment such as a classroom or other learning environment (Kotob and Ibrahim, 2019; Riwanda et al., 2021; Bin Jaafar and Yusoff, 2022; Abdelhamid et al., 2023). Game-based strategies involve integrating phone or computer-based games into the learning process (Ju and Adam, 2018; Ghani et al., 2019; Al Hejaili and Newbury, 2023). Serious games focused on incorporating physical games in the classroom to aid in simulations during the learning process (Al-Bulushi and Al-Issa, 2017).

In learning the Arabic language, gamification is applied to enhance learners’ engagement and motivation in the learning process. Gamifying the classroom environment by incorporating different games or phone-based games increases learners’ attentiveness and participation in learning (Azmi and Zakaria, 2020; Noor et al., 2023). From the teacher’s perspective, games offer rankings, badges, levels, points (Putri et al., 2021), and storytelling (Al-Bulushi and Al-Issa, 2017) elements that assist learners in mastering language vocabulary and grammar.

4.1 Gamified strategies for Arabic language learning

Numerous gamified strategies have been adopted for Arabic language learning. Kahoot! is a quiz-based platform with game elements such as competition, ranking, and points (Riwanda et al., 2021). The platform allows teachers to use learning images and audio to teach the Arabic language and develop collective scores based on quizzes. The teacher has access to and control of the game, scores for each quiz, and score display in competitions. Animated digital game quizzes such as Quizizz and Fun Easy Learn Apps have also been employed to enable learners to master Arabic language vocabulary (Ju and Adam, 2018; Putri et al., 2021). The animated games provide convenience and motivate them to participate in the mastery of Arabic vocabulary and grammar presented through learning games. Multiple players can participate in a Quizizz using phones or computers as a game-based classroom activity, allowing learners to practice together and compete for mastery of Arabic vocabulary. In the game, points are awarded, scores are aggregated, and learners are ranked based on their scores. The process makes learning interactive, enjoyable, and fun for the learners (Putri et al., 2021).

Some studies have experimented with the application of e-learning tools for learning the Arabic language. Ghani et al. (2019) experimented with the application of e-Mufradat, a digital-based e-learning platform for learning the Arabic language. E-Mufradat is designed for non-native speakers seeking to learn the Arabic language. Therefore, instructional icons are necessary to assist the learners in navigating and using the platform to learn Arabic vocabulary. The game was found to improve learner engagement, fantasy, and motivation in Arabic language learning. Different levels and challenges of the game allow players to earn points and unlock new challenges, providing fantasy and enjoyment experiences to users.

4.2 Gamification drives learner engagement and motivation

Motivation arises from increased self-interest, self-esteem, self-expectations, and satisfaction with the learning process (Kotob and Ibrahim, 2019). Evidence from past studies suggested that gamified learning strategies enhance learners’ motivation, achievement, and satisfaction with the learning process. Gamification methods are designed to assist learners in navigating the motivation and engagement challenges associated with learning the Arabic language through gamified elements that make the learning process enjoyable (Sheldon and Lyubomirsky, 2012; Noor et al., 2023).

Learners’ motivation in the learning process is critical for successful mastery of the Arabic language. Mazer and Al-Ajlouni (2023) demonstrated the ability of game-based learning strategies such as Kahoot, Quizizz, and Lego education to motivate and stimulate learner engagement in the classroom. The study noted that the motivational factor in gamified learning approaches can be linked to the collaborative, competition, and communication aspects of gamification activities in the classroom. These insights align with previous findings by Osipov et al. (2015) and Reis et al. (2023), suggesting that teachers motivate students to play and achieve higher scores in the games for higher scores and ranking. Kotob and Ibrahim (2019) noted that the enthusiasm and commitment of teachers are critical factors that drive learners’ motivation to engage and participate in gamified activities.

Gamification influences learners’ intrinsic motivation to participate in Arabic language learning. Gamified environments and game elements stimulate internal motivation among learners (Mazer and Al-Ajlouni, 2023). This drive originates from the individual’s self-interest, hobbies, and self-assurance. This innate desire is often more powerful and has the potential to endure for longer periods. The points, reward, competition, and ranking elements of digital games tend to influence a sense of competition among learners, motivating them to achieve the maximum score in each game level (Ghani et al., 2019; Putri et al., 2021). For example, playing e-Mufradat and the Educational Charade games was found to improve learners’ motivation and commitment to speak and read Arabic vocabulary (Ismath et al., 2022; Noor et al., 2023). The games provided an interactive learning environment, increasing learners’ interest and involvement in classroom activities. The environment boosted their innate drive to complete and achieve success in mastery of the Arabic language.

Students can also draw motivation from teacher perception and attitudes toward gamified learning strategies. Bin Jaafar and Yusoff (2022) noted that the degree of motivation is influenced by the instructor’s enthusiasm and commitment to their work. Teachers need to motivate the learners to master Arabic language skills. The instructor’s commitment plays an inspiring role for students in building the appropriate mindset for learning the Arabic language (Ghani et al., 2019; Putri et al., 2021). Students believed that instructors should possess particular attributes, such as politeness and friendliness, the ability to comprehend students’ challenges and provide assistance, proficiency in explanation, and the ability to make instruction more engaging and enjoyable (Ismath et al., 2022). This perspective corresponds to past findings suggesting a significant correlation between instructor commitment and students’ motivation and achievement in Arabic language learning (Kotob and Ibrahim, 2019).

Generally, learning the Arabic language through gamified methods is beneficial, particularly for beginners. Gamification provides an enjoyable and challenging experience for learners, motivating them to become committed and participate in the classroom activity. The students develop a more competitive spirit and anticipate their chances of achieving high scores for each game level and ranking high against fellow learners (Sahrir and Alias, 2011; Kotob and Ibrahim, 2019; Azmi and Zakaria, 2020). The feedback and audio elements integrated into the gamified strategies and mobile digital games facilitate user engagement with the teacher and other learners (Saleh et al., 2022; Abdelhamid et al., 2023). The audio function in many games assists in correctly pronouncing Arabic words, thus improving their reading and speaking skills (Al Hejaili and Newbury, 2023). As a result, the games reduce feelings of boredom and tiredness while also motivating mastery of the Arabic language.

4.3 Effectiveness and acceptance of gamification

The effectiveness and impact of gamification for Arabic language learning have been widely investigated in past literature. Sahrir and Alias (2011) revealed that non-native Arabic language learners in Malaysia reported a significant impact of gamified learning strategies on their mastery of Arabic vocabulary. The learners demonstrated good impressions and perceptions about employing language games in learning Arabic rhetoric. Mazer and Al-Ajlouni (2023) focused on gamification in Arabic language learning in Jordan. They reported a positive relationship between using language game-based learning strategies for languages and learners’ improvement in Arabic reading and writing skills. However, there were no significant differences in developing reading skills among non-native-speaking Arabic language learners.

Numerous research studies have generated positive outcomes of gamification in learning Arabic speaking, writing, and listening skills. Bin Jaafar and Yusoff (2022) reported positive acceptance and value of online games in learning the Arabic language among primary school learners. Kenali et al. (2019) found that smartphone-based games positively influenced learners’ motivation and ability to speak and write Arabic. Gamified learning strategies facilitate learning of Arabic vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation (Mazer and Al-Ajlouni, 2023), and students are required to play an active role in the Arabic language game (Saleh et al., 2022). The class can be subdivided into various groups, and each group is required to play against each other in a game garnering point, which are aggregated, and scores are given. Literature evidence has shown that playing and practicing as a group enhances students’ participation in the learning process and mastery of vocabulary. This strengthens their speaking (Riwanda et al., 2021) and verbal (Putri et al., 2021; Saleh et al., 2022) abilities.

Vocabulary mastery is an important aspect of Arabic language learning. Gamified strategies and smartphone-based games have been applied to improve learner’s mastery of Arabic vocabulary. The application of the Quizizz game in Arabic language learning enabled learners to improve their vocabulary achievement and mastery significantly (Riwanda et al., 2021; Bin Jaafar and Yusoff, 2022). The game’s elements and instructions are designed to match Arabic words and grammar, enabling the user to read and master the vocabulary. Some studies reported using animated games, such as Quizzes and 3D gamification of Arabic words and pictures, to teach Arabic vocabulary (Putri et al., 2021). Quizzes are designed to facilitate verbal delivery and assist a user or multiple users in answering correct questions, focusing on mastering vocabulary. Riwanda et al. (2021) argued that learning Arabic vocabulary through games increased learners’ ability to memorize, master, and speak the vocabulary. In other words, gamification provides the convenience for non-natives to read, write, and understand Arabic text (Baharudin and Din, 2022).

The increase in students’ vocabulary achievement and experience may be influenced by the unique characteristics of educational games, such as the elements of fun and entertainment (Ghani et al., 2019). Users can accomplish each game’s learning goal by following the straightforward and uncomplicated flow. Learners can share their thoughts about mobile digital games, particularly concerning the ability of these games to alleviate their worries, which was particularly prevalent among students unfamiliar with the Arabic language (Sahrir and Alias, 2011; Azmi and Zakaria, 2020).

4.4 Teacher’s perspective on gamification for Arabic language learning

Few studies have provided a teacher perspective of gamified learning strategies for Arabic language learning. Findings from the study revealed that gamified learning strategies strengthened the relationship between instructors and students (Azmi and Zakaria, 2020). While some teachers supported traditional methods of teaching the Arabic language, the majority acknowledged the effectiveness of gamification in helping students improve their logical thinking and critical analysis skills (Sahrir and Alias, 2011; Al Hejaili and Newbury, 2023). Teachers identified the huge cost of implementing gamified learning strategies into the learning process as a key barrier to applying gamification in Arabic language learning. Instead, they suggest implementing serious games to overcome the cost barrier (Al-Bulushi and Al-Issa, 2017).

Mastering Arabic grammar can be a tedious and challenging task. Teachers leverage game elements and components to create gamified instructions and pictures for learners to play in grammar lessons (Sahrir and Alias, 2011). The gamified instructions help draw students’ attention, increasing their participation in the learning process, which increases their grammar proficiency. There was a direct connection between instructor feedback and students’ improvement in the Arabic language in gamified environments (Kotob and Ibrahim, 2019). Gamification strengthens the teacher–student connection, allowing for the real-time provision of feedback on students’ achievements and performance (Al-Bulushi and Al-Issa, 2017; Saleh et al., 2022).

Instructors educate and communicate with students during gamified activities, enabling students to overcome challenges in learning Arabic language skills. In addition, the teacher identifies challenges with the digital games used for learning Arabic, allowing them to alter and enhance the provision of Arabic instructions to users (Ju and Adam, 2018). The teacher may adapt questions and presumptions by basing them on problems pupils have already answered. This way, students can identify and analyze their replies, which is essential in improving the effectiveness of the game (Azmi and Zakaria, 2020).

4.5 Challenges of gamification for Arabic language learning

The usage of technology in games and applications for Arabic language learning has several significant shortcomings. Some gamified learning strategies and digital games do not encourage teacher involvement or presence when playing the games (Azmi and Zakaria, 2020; Ismath et al., 2022). This reduces teacher–student interaction, hence denying students necessary feedback which would otherwise benefit students in improving their Arabic language mastery. It also increases uncertainties for game users when executing a challenging task. Some teachers possess poor technology skills, hence creating a barrier to the application of digital-based games into the learning process. As such, the teachers rely on traditional methods to teach Arabic vocabulary and grammar. Vario’s studies reported that traditional methods were less effective in teaching and learning the Arabic language (Sahrir and Alias, 2011; Ju and Adam, 2018; Noor et al., 2023).

Studies have reported gaps in teacher’s digital skills (Al-Bulushi and Al-Issa, 2017). In addition, there are many standard curricula for many schools and other educational establishments (Ghani et al., 2019; Kotob and Ibrahim, 2019). The educational system constantly evolves, and adjusting successfully to digital learning methods might be challenging. Many gamification techniques rely on technology to disseminate Arabic language instructions (Ghani et al., 2019). Some educators may not have a complete understanding of the rules that govern Arabic language games. As a result, they may be unable to optimize the game elements to provide Arabic language learning solutions in the classroom (Mazer and Al-Ajlouni, 2023).

5 Conclusion and recommendations

This systematic literature review examined the application and effectiveness of gamified learning strategies in teaching the Arabic language to non-native speakers. Gamification for learning the Arabic language has been widely discussed and explored in past research. Literature evidence suggests that gamification improves students’ overall motivation, engagement, and achievement in the learning process. A gamified learning environment, or playing digital-based games in class, stimulates learners’ commitment and participation in classroom activities. It encourages players to become attentive and actively engage other students and teachers to accomplish gamified tasks. It also encourages them to work together while playing these games.

Students involved in gamified learning methods often demonstrate an excessive level of ambition and achievement in learning Arabic vocabulary and grammar. Introducing these games is one of the most effective strategies to manage competitiveness among peers. Students are encouraged to compete against one another while playing these activities. The scores, ranking, and reward elements of the game encourage users to compete, creating a fantastic and enjoyable medium to teach Arabic vocabulary. Future research should focus on developing more innovative gamified strategies for beginners in learning the Arabic language.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SA: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdelhamid, I. Y., Yahaya, H., and Shaharuddin, H. N. (2023). Assessing the impact of gamification on academic achievement and student perceptions of learning Arabic grammar: a quasi-experimental study. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 13, 760–773. doi: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v13-i5/16862

Al Hejaili, A., and Newbury, P. (2023). LAA: learn the Arabic alphabet: integrating gamification elements with touchscreen based application to enhance the understanding of the Arabic letters forms. Electron. J. e-Learn. 21, 353–365. doi: 10.34190/ejel.21.4.3043

Al-Bulushi, A. H., and Al-Issa, A. S. (2017). Playing with the language: investigating the role of communicative games in an Arab language teaching system. Int. J. Instr. 10, 179–198. doi: 10.12973/iji.2017.10212a

Alshahrani, A. (2019). Teaching Arabic as a second language (TASL): simulation of the Canadian/American exemplary TESL models. A feasibility study in promoting a Saudi-owned TASL Programme. Arab World Engl. J. 10, 298–313. doi: 10.24093/awej/vol10no1.25

Arttırmak, O. D., KB, Ö., and Samet, B. A. L. (2018). Using Quizizz.com to enhance pre-intermediate students’ vocabulary knowledge. Int. J. Lang. Acad. 6, 295–303. doi: 10.18033/ijla.3953

Azmi, N. H., and Zakaria, Z. M. (2020). Gamification among of UPSI training teacher during teaching practice in school. Int. J. Mod. Educ. 2, 56–67. doi: 10.35631/IJMOE.24005

Baharudin, H., and Din, Z. (2022). Level of Arabic text reading skills in the integrated dini curriculum. Ijaz Arabi J. Arabic Learn. 5, 59–71. doi: 10.18860/ijazarabi.v5i1.14260

Bin Jaafar, M. N., and Yusoff, N. M. R. N. (2022). Experimental study of the effectiveness of gamification module for Arabic language in primary school. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 12, 2102–2117. doi: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v12-i6/14220

Cabeza-Ramírez,, Luis Javier,, Guzmán Antonio Muñoz-Fernández,, and Luna Santos-Roldán, (2021). Video Game Streaming in Young People and Teenagers: Uptake, User Groups, Dangers, and Opportunities. Healthcare, 9, 1–16. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9020192

Campbell, S. (2014). What is qualitative research?. Clinical Laboratory Science, 27, 3. doi: 10.29074/ascls.27.1.3”10.29074/ascls.27.1.3

Dajani, B., Mubaideen, S., and Omari, F. (2014). Difficulties of learning Arabic for non-native speakers. Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 114, 919–926. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.808

Deterding, S., Khaled, R., Nacke, L., and Dixon, D. (2011). Gamification: toward a definition, pp. 12–15.

Gears, D., and Braun, K. (2013). Gamification in business: designing motivating solutions to problem situations. In Chi-Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (p. 5).

Ghani, M. T. A., Hamzah, M., Romli, T. R. M., Eltigani, M. A. M. A., and Daud, W. A. A. W. (2019). E-Mufradat: a digital game application for learning Arabic vocabulary among non-native Arabic speakers. Int. J. Acad. Res. Progress. Educ. Dev. 8, 58–69. doi: 10.6007/IJARPED/v8-i3/6261

Habók, A., and Magyar, A. (2018). The effect of language learning strategies on proficiency, attitudes and school achievement. Front. Psychol. 8, 1–16. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02358

Hakak, S., Noor, N. F. M., Ayub, M. N., Affal, H., Hussin, N., and Imran, M. (2019). Cloud-assisted gamification for education and learning–recent advances and challenges. Comput. Electr. Eng. 74, 22–34. doi: 10.1016/j.compeleceng.2019.01.002

Ismath, N. H. M., Jalil, S. Z., and Rahman, T. A. F. T. A. (2022). The effectiveness of gamification in learning Arabic cohesive devices. Attarbawiy: Malaysian online. J. Educ. 6, 28–36. doi: 10.53840/attarbawiy.v6i2.96

Jasni, S. R., Zailani, S., and Zainal, H. (2019). Pendekatan Gamifikasi dalam Pembelajaran Bahasa Arab: Gamification Approach in Learning Arabic Language. J. Fatwa Manage. Res. 13, 358–367. doi: 10.33102/jfatwa.vol13no1.165

Johnson, D., Deterding, S., Kuhn, K. A., Staneva, A., Stoyanov, S., and Hides, L. (2016). Gamification for health and wellbeing: a systematic review of the literature. Internet Interv. 6, 89–106. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2016.10.002

Ju, S. Y., and Adam, Z. (2018). Implementing Quizizz as game-based learning in the Arabic classroom. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Res. 12, 208–198.

Kenali, H. M. S., Yusoff, N. M. R. N., bt Mat Saad, N. S., Abdullah, H., and Kenali, A. M. S. (2019). The effects of language games on smartphones in developing Arabic speaking skills among non-native speakers. Creat. Educ. 10, 972–979. doi: 10.4236/ce.2019.105073

Kiryakova, G., Angelova, N., and Yordanova, L. (2014). Gamification in education. In Proceedings of 9th International Balkan Education and Science Conference. Dubrovnik, Croatia.

Kotob, M. M., and Ibrahim, A. (2019). Gamification: the effect on students’ motivation and achievement in language learning. J. Appl. Linguist. Lang. Res. 6, 177–198. doi: 10.4995/eurocall.2020.12974

Luo, Z. (2023). The effectiveness of gamified tools for foreign language learning (FLL): a systematic review. Behav. Sci. 13:331. doi: 10.3390/bs13040331

Majuri, J. K., and Hamari, J., (2018). Gamification of education and learning: A review of empirical literature. In Proceedings of the 2nd International GamiFIN Conference, Pori, Finland.

Mazer, M. A., and Al-Ajlouni, K. (2023). The effect of using gamification on motivating learning Arabic in the E-learning environment for eighth-grade students in Amman, Jordan. Dirasat: Educ. Sci. 50, 256–266. doi: 10.35516/edu.v50i3.3086

Moghazy, M. (2021). Arabic vocabulary builder for beginners: The unspoken Arabic. Cairo, Egypt: Independntly Published.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., and Altman, D. G.PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 151, 264–269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Mokhtar, M. (2020). Lower secondary students’ Arabic speaking anxiety: a foreign language literacy perspective. Int. J. Educ. Literacy Stud. 8:33. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.8n.4p.33

Najjar, M. (2020). Teaching Arabic syntax for non-speakers: a pragmatic approach. Int. J. Learn. Teach. 6, 252–256. doi: 10.18178/ijlt.6.4.252-256

Noor, M. L. A. H. B. M., Gani, M. Z. B. A., Ismail, N. S. B., binti Ahmad, N. Z., Mohd, K., and Shamsudin, J. M. (2023). Implementing Arabic educational charade game in acquiring Arabic vocabulary and improving Arabic speaking skills. Sciences 13, 291–305. doi: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v13-i6/17406

Osipov, I., Nikulchev, E., and Prasikova, A. (2015). Study of gamification effectiveness in online e-learning systems. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 6, 71–77. doi: 10.14569/IJACSA.2015.060211

Putri, A. H., Permatasari, F. E., Hijriyah, A. L., and Mauludiyah, L. (2021). Arabic quizzes game to improve Arabic vocabulary. Tanwir Arabiyyah Arabic Foreign Lang. J. 1, 45–54. doi: 10.31869/aflj.v1i1.2484

Reis, S., Linck, A., Figueiredo, M., and Pfeifer, D. (2023). Gamification into the design of the e-3D online course. Front. Educ, 8, 1152999. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1152999

Rieder-Bünemann, A. (2012). “Second language learning” in Encyclopedia of the sciences of learning. ed. N. M. Seel (Boston, MA: Springer)

Ritonga, M., Febriani, S. R., Kustati, M., Khaef, E., Ritonga, A. W., and Yasmar, R. (2022). Duolingo: an Arabic speaking skills’ learning platform for andragogy education. Educ. Res. Int. 2022, 1–9. doi: 10.1155/2022/7090752

Riwanda, A., Ridha, M., and Islamy, M. I. (2021). Increasing Arabic vocabulary mastery through gamification is Kahoot! Effective? LISANIA J. Arabic Educ. Lit. 5, 19–35. doi: 10.18326/lisania.v5i1.19-35

Sahrir, M. S., and Alias, N. A. (2011). A study on Malaysian language Learners' perception towards learning Arabic via online games. GEMA Online J. Lang. Stud. 11, 129–145.

Saleh, M., Arifin, Z., and Hanefarezan, L. (2022). Language games in learning Arabic rhetoric for non-Arab. Ijaz Arabi J. Arabic Learn. 5, 671–689. doi: 10.18860/ijazarabi.v5i3.16211

Shahri, A., Hosseini, M., Phalp, K., Taylor, J., and Ali, R. (2019). How to engineer gamification: the consensus, the best practice, and the grey areas. J. Organ. End User Comput. 31, 39–60. doi: 10.4018/joeuc.2019010103

Sheldon, K. M., and Lyubomirsky, S. (2012). The challenge of staying happier: testing the hedonic adaptation prevention model. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 38, 670–680. doi: 10.1177/0146167212436400

Tan, M., and Hew, K. F. (2016). Incorporating meaningful gamification in a blended learning research methods class: examining student learning, engagement, and affective outcomes. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 32, 19–34. doi: 10.14742/ajet.2232

Tomaselli, F., Sanchez, O., and Brown, S. (2015). How to engage users through gamification: the prevalent effects of playing and mastering over competing. ICIS-international conference on information systems (ICIS 2015), Texas

Wünderlich, N., Hogreve, J., Ilma Nur Chowdhury, I., Fleischer, H., Mousavi, S., Julia Rötzmeier-Keuper, J., et al. (2020). Overcoming vulnerability: channel design strategies to alleviate vulnerability 26 perceptions in customer journeys. J. Bus. Res. 116, 377–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.027

Yan Mei, S., Yan, J. S., and Adam, Z. (2018). Implementing quizizz as game based learning in the Arabic classroom. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Res. 5, 194–198. doi: 10.26417/ejser.v12i1.p208-212

Yildirim, I. (2017). The effects of gamification-based teaching practices on student achievement and students' attitudes toward lessons. Internet High. Educ. 33, 86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2017.02.002

Keywords: gamification, gamified learning strategies, learning Arabic language, teaching, non-native speakers

Citation: Almelhes SA (2024) Gamification for teaching the Arabic language to non-native speakers: a systematic literature review. Front. Educ. 9:1371955. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1371955

Edited by:

Muhammad M. M. Abdel Latif, Cairo University, EgyptReviewed by:

Wahyu Widada, University of Bengkulu, IndonesiaReza Kafipour, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Iran

Copyright © 2024 Almelhes. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sultan A. Almelhes, cy5hbG1lbGhlc0BpdS5lZHUuc2E=

Sultan A. Almelhes

Sultan A. Almelhes