- 1The Office for Education Policy, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, United States

- 2The Department of Education Reform, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, United States

On August 11, 2023, the Arkansas Department of Education (ADE) notified schools just before the fall semester’s start that they would no longer support the college-board-approved AP African American Studies (APAAS) course. Subsequently, all five districts offering the course declared their intent to proceed despite the lack of state funding and course credits. We conduct a document and qualitative thematic analysis in this mixed methods study. In documents, we find distinctive shifts in how the significance of APAAS is portrayed within differing contexts. Using interviews with Arkansas superintendents, teachers, students, and stakeholders, we find four major interview themes: the role of education in preserving democratic values, equity concerns, the significance of community support and advocacy, and the impact of political influences. Documents and stakeholders interviewed perceive the ADE’s withdrawal of support as politically motivated, while superintendents, teachers, and students are primarily motivated by the curriculum, student welfare, and community interests in offering APAAS. We conclude by suggesting that greater consideration of factual knowledge, coupled with choice within and between schools, could defuse such controversies.

1 Introduction

“People genuinely wanted to contribute to making this class a reality, not just financially, but also to validate its importance and show their support.”—Arkansas Stakeholder.

“In a conflict situation, all sides usually have legitimate concerns.”—Foster (1971, p. 19)

Theoretical frameworks in education often explore how meaning-making and policymaking processes shape educational and instructional decisions. Notable debates in the literature focus on the tensions between empirical evidence, advocacy, and political influences in educational settings. Key unanswered questions within this field include how different stakeholders perceive and respond to controversial educational policies, and how these perceptions influence policy outcomes. The Arkansas AP African American Studies course offers a strategic case to examine these issues, providing insights into the complexities of educational governance and stakeholder engagement in a politically charged environment.

In the spring of 2023, a notable shift in educational policy emerged in Florida, a state known for its significant control over K-12 public schooling. This shift, potentially influenced by Governor Ron DeSantis’s presidential campaign, which notably focused on curbing the influence of “woke” educational institutions, led to Florida opting out of the AP African American Studies (APAAS) course (Khalid and Snyder, 2023). Concurrently, in Arkansas, Education Secretary Jacob Oliva, a former Florida educator and policymaker, was appointed by Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders, a former White House Press Secretary with likely national political aspirations. During this period, Oliva actively supported Governor Sanders’ LEARNS initiative, a comprehensive educational reform focusing on various aspects, including teacher pay and school choice. Despite these broad educational endeavors, Oliva dedicated significant effort to scrutinizing the adoption of APAAS in school districts and charter schools, seeking detailed curriculum information in the spring of 2023.

However, in a sudden move on August 11, 2023, the Arkansas Department of Education (ADE) blindsided schools at the cusp of the new academic year. ADE announced the cessation of state support for the APAAS course financially and in terms of academic credit recognition. This abrupt decision affected five school districts offering APAAS, which, despite the state’s removal of support, still adamantly chose to continue the course despite the lack of state funding and uncertainty regarding graduation credits. This defiant stance by the schools highlights a complex interplay of educational governance and school autonomy.

Our mixed-methods study explores this contentious scenario through a dual approach: document analysis and interviews with various stakeholders, including Arkansas superintendents, teachers, students, and community members. The findings reveal four predominant themes: preserving democratic values in education, equity concerns, the vital role of community support and advocacy, and the impact of political influences. The withdrawal of ADE’s support for APAAS is perceived by many as politically motivated, contrasting with the motivations of superintendents, teachers, and students, who emphasize curriculum relevance, student welfare, and community interests. In our conclusion, we argue for the potential reduction of polarization in such conflicts through a nuanced understanding of factual knowledge, a deeper discussion on the role of politics in public education, and, ideally, more varied educational choices across schools. Additionally, it is essential to contextualize these contemporary educational conflicts within a broader historical perspective, noting their relative moderation compared to past educational disputes, such as the anti-Catholic school riots of the 19th century (van Raemdonck and Maranto, 2018) and the turbulent periods of the late 1960s and 1970s (Spencer, 2012).

We hypothesize that the defiance by Arkansas schools is driven by a strong commitment to educational values and community support, despite political opposition. We further hypothesize that these actions reflect broader global trends in educational governance, where local decision-making increasingly challenges state-level regulations. These hypotheses will be examined through our mixed-methods approach, providing a comprehensive understanding of the case and its implications for educational policy and practice.

2 Literature review

2.1 School culture wars

When guided by expert consensus and primarily shielded from political interference, Bureaucracies can function effectively in contexts where goals and methodologies are well-established and broadly agreed upon (Hult and Walcott, 1990). In such cases, the objectives—like ensuring safe drinking water—are universally desired, and the means of achieving these objectives are well-understood and stable, facilitated by noncontroversial technologies (Teodoro et al., 2023). This scenario contrasts sharply with the field of education, which is characterized by a lack of consensus on its goals and methodologies. Unlike areas with stable and uncontested objectives and technologies, the education sector is perpetually embroiled in debates and disputes over its aims and approaches, reflecting a fundamental uncertainty and diversity of opinions about the very purpose and methods of education.

2.1.1 Debates in educational methods

The methodologies employed in education have long been a subject of intense debate, reflecting the sector’s inherent complexity and the diversity of its stakeholders. Despite the potential for scientific inquiry to inform effective teaching practices, consensus on the most effective methods remains elusive. As highlighted by Chall (2000), empirical evidence suggests that teacher-centered instruction mainly benefits low-income children, aligning more closely with parental preferences (Lareau, 2003). However, this perspective is often contrasted with the advocacy for child-centered approaches by influential educational theorists like Freire and Ramos (1970), approaches that resonate with the ideological and pedagogical preferences of many educators (Hirsch, 1996).

This dichotomy is exemplified in the domain of reading instruction. While extensive research indicates the effectiveness of phonics instruction, especially when compared to methods like ‘three-cueing’ or other whole language approaches (Hanford, 2022; Hirsch, 1996, 2009), a significant faction within the education community has criticized and even condemned phonics teaching as overly prescriptive. This rejection reflects a broader skepticism within the field of education, particularly since the Progressive era, towards applying scientific methods, a skepticism that has served to differentiate the field from other academic disciplines (Maranto and Wai, 2020).

Moreover, education goals are even more contentious than the methods employed. Educational theorists, policymakers, and the public engage in ongoing debates about the extent to which schools should promote patriotism and common knowledge (Allen, 2015; Hirsch, 2009), foster a love for academic learning (Hirsch, 1996; Mehta and Fine, 2019), impart historical knowledge for citizenship, with an emphasis on comparative analyses between the U.S. and other countries (Civic Alliance, 2023), replicate the diverse cultures and faiths of students’ families and communities (Fox and Buchanan, 2014; Koganzon, 2020), teach social interaction in ways that are resilient and nonjudgmental (Lukianoff and Haidt, 2018), focus on narrowly defined vocational skills (Wagner, 2008), encourage Antiracist thought and action (Kendi, 2019), or even inspire proletarian revolution (Freire and Ramos, 1970). These debates are not new; they have persisted for millennia in Western education and globally (Hess, 2010; Taylor and Guyver, 2012), underscoring the deeply embedded and complex nature of educational objectives.

2.1.2 Historical and contemporary school culture wars

Zimmerman (2022) seminal work on the history of education in the United States illustrates how the goals of schooling have frequently been at the center of cultural conflicts. In a nation marked by its freedoms and diversity, the debates in education often revolve around defining and understanding our collective identity – who we are, who we have been, and who we aspire to be. These culture wars have been particularly pronounced in history and social studies education, where the inclusion, exclusion, or denigration of historical figures often reflects efforts to cater to specific constituencies.

During the World Wars, for instance, elite historians underscored the continuity between U.S. founding principles and British governance, a narrative that sought to strengthen the U.S.-Anglo alliance against Germany. This interpretation was countered by some, notably Catholic politicians, who highlighted the contributions of German and Irish Americans in the American Revolution, sometimes leveraging these perspectives for electoral gain. More profoundly concerning, however, has been the treatment of slavery in the context of the U.S. Civil War. Historians, both progressive and conservative, have been known to downplay or misrepresent the centrality of slavery as a causative factor in the war. For instance, progressive historians like Charles and Mary Beard equated the conditions of slavery with those of industrial capitalism. At the same time, some conservative writers romanticized slavery as a benevolent institution, the so-called ‘Lost Cause’ narrative. This narrative found resonance particularly among southern white people, despite being widely discredited by scholars and contradicted by the historical record of enslaved people taking significant risks to escape bondage and the lack of evidence of any free persons of color seeking re-enslavement.

The adherence to the ‘Lost Cause’ paradigm by many in the South, as Zimmerman (2022, pp. 37–38) notes, has had a lasting impact on race relations and regional identity in the United States. Criticism of this narrative, therefore, has not merely been a matter of historical accuracy but has also become a flashpoint in the broader cultural conflicts within the educational sphere. The persistence of these cultural battles over history and social studies education indicates the deep-seated nature of school culture wars, which continue to shape contemporary debates in education (Maranto, 2021b).

2.1.3 Expert autonomy vs. public and political influence

Maranto (2022), drawing on his experience on a school board, articulates that school culture wars, both historically and in the contemporary context, possess distinct characteristics that set them apart from more routine educational disputes:

First, they involve identity, with social groups battling other social groups over who we are. These questions are not quickly settled by standard decision rules like splitting the difference over budgets because the stakes are less material than ideological and social. Compromisers face charges of disloyalty to their group identity when they are just practicing everyday democracy. Relatedly, these are zero-sum conflicts: to the degree one side wins, another loses. Agreements are fragile since some people want to keep on fighting. Even well-educated participants overlook facts that fail to resonate emotionally. Third, particularly in the age of social media, conservative think tanks, and liberal foundations, conflicts often become national in scope. With variations, the same battles play out before local school boards in Missouri, Massachusetts, and Colorado. Finally, key combatants often have no children in schools and are thus less motivated to find acceptable compromises so that, over the long run, we can all work together. Nonetheless, as taxpayers (and grant givers), they must be taken seriously.

Furthermore, school culture wars frequently feature confrontations between public and political entities and institution-based experts. This dynamic, highlighted by Zimmerman (2022), Koganzon (2020), McCluskey (2022), and Knox (2015), involves experts — ranging from Ivy League professors to state bureaucrats and local educators — who often strive to maintain their professional autonomy against the pressures exerted by the public and political figures. A notable example of this tension surfaced in the 2021 Virginia gubernatorial race, where candidate Terry McCauliffe, suggesting that parents should not have a role in shaping school curricula, became a pivotal issue. This incident exemplifies the distrust between parent activists and educational experts, rooted in past interactions or broader societal narratives (Izumi et al., 2022).

Moreover, education experts, whether dealing with the teaching of history (Maranto, 2021a, 2021b, 2022) or reading instruction (Hanford, 2022), have sometimes clung to erroneous positions, sometimes for decades. The reluctance to acknowledge errors or embrace corrections is often motivated by fears of losing professional credibility, employment, or seeming disloyal to their field. This tendency underscores a fundamental aspect of the ongoing culture wars in education: the complex interplay and sometimes the clash between professional expertise and the influences of public opinion and political forces.

2.1.4 Black history in culture wars

The role of Black History in the educational landscape, particularly in the context of cultural wars, has been a periodically contentious topic. This discussion has gained renewed momentum following the racial reckoning triggered by the murder of George Floyd. The teaching of Black History and its more activist-oriented counterpart, Black Studies, has been a subject of debate and methodological scrutiny. Wood and Randall (2023) argue that the first revisions to the APAAS course by the College Board reflect a shift towards activism rather than a focus on Black history, raising concerns about the course’s adherence to a balanced historical perspective. As outlined by Zimmerman (2022) and others (Foster, 1971; Spencer, 2012; Woodson, 2021), the initial intent behind integrating Black history into the curriculum was to acknowledge significant historical figures previously overlooked due to racial biases and to affirm the presence and contributions of Black individuals in the narrative of U.S. history.

However, this approach was not without its critics. Notably, some Black intellectuals (Sowell, 1972) and politicians (Zimmerman, 2022, pp. 113–114) in the 1960s and 1970s expressed concerns about the segregation of Black history into separate courses, fearing it might lead to a form of educational and political apartheid, exacerbated by student and parent choices. Wood and Randall (2023) further critique the framing of African American Studies, which they claim has evolved into a pseudo-discipline focused more on political activism than providing a comprehensive and fact-based account of African American history and culture. The debate extends to the broader issue of school choice and local control. While Zimmerman (2022) suggests that such decentralization could fragment U.S. education, McCluskey (2022) and van Raemdonck and Maranto (2018) argue that it could foster political and social peace by accommodating diverse perspectives and reducing coercion in education.

Central to the discourse on Black history is its fundamental nature as history. Carter G. Woodson, a Harvard-trained historian and a pivotal figure in establishing Black History as a scholarly field in the U.S., emphasized the importance of adhering to rigorous historical methods to ensure accuracy. He critiqued attempts to politicize Black history, such as claims asserting the African ancestry of a wide range of historical figures without empirical evidence. Woodson advocated for a fact-based approach to Black history, positioning it as a legitimate subfield of history, distinct from the politically motivated narratives like the ‘Lost Cause’ paradigm prevalent in U.S. education in the early and mid-20th century. As noted by Zimmerman (2022) and Maranto (2021a, 2021b, 2022), this emphasis on factual accuracy and methodological rigor is often less prevalent in culture wars within education, where emotional resonance can overshadow empirical evidence. Flynn (2020) and Pluckrose and Lindsay (2020) argue that the shift away from empirical rigor in academia has further complicated the landscape, underscoring the challenges faced in ensuring that the teaching of Black history and studies remains grounded in factual accuracy and scholarly integrity.

2.1.5 Educational conflicts and implications

Political science research has extensively demonstrated that constituencies frame conflicts differently, influencing their perceptions and interpretations. This is evident across various groups, from bureaucracies (Allison, 1971) to political leaders (Jervis, 1976) and even voters (Haidt, 2012; Popkin, 1991). These frames serve as heuristics, shaping how new information is processed and understood, thereby placing ongoing events within a broader context (Pratkanis, 2007). Such framing is crucial in education, where stakeholders often have divergent views and priorities.

The framing of educational conflicts is particularly salient when considering the historical and contemporary dynamics of school culture wars. As chronicled by Zimmerman (2022), these conflicts have roots stretching back to the 1890s and highlight the perennially contested nature of schooling (Hult and Walcott, 1990). The implications of these debates are far-reaching, affecting aspects such as local educational autonomy, control, racial equity, national identity (Lepore, 2018, 2019), and school choice (Maranto and McGee, 2023; McCluskey, 2022). Understanding these frameworks and the historical context in which they are situated is crucial for comprehending the complex landscape of educational conflicts and their broader societal implications.

2.2 This study

This study explores the recent Arkansas incident involving the APAAS course, a subject of national discussion and an exemplar of contemporary school culture wars. By conducting textual analyses of documents and news articles, we aim to discern the frameworks used by national media and local educators in interpreting this high-profile educational conflict. The APAAS course, undergoing development and pilot testing by the College Board, became spotlighted following modifications made in February 2023. These changes were an attempt to accommodate concerns from Florida and other conservative states with significant market influence but also led to subsequent adjustments in response to academic professionals (College Board, 2023; Eden, 2023). This situation has created some ambiguity regarding the course’s content and parallels past controversies, such as those surrounding AP U.S. History (Zimmerman, 2022, pp. 218–222).

Our analysis is centered on understanding the educational conflicts surrounding APAAS by examining the rhetoric and language used in public discourse (Gándara and Daenekindt, 2022). This approach will help us explore the themes emerging from various narratives and perspectives in this case. Specifically, our research is guided by four key questions:

RQ1: What prominent themes emerge from the content analysis of documents related to AP African American Studies (APAAS), documents about the Arkansas attempt to remove APAAS, and interviews conducted with Arkansas stakeholders regarding APAAS? How do these themes differ in their portrayal and understanding of APAAS’s significance within the educational context?

RQ2: What motivated Arkansas districts to continue offering AP African American Studies despite state opposition?

RQ3: How did community engagement and public sentiment influence the schools’ decision to maintain AP African American Studies?

RQ4: How does Arkansas schools’ defiance in offering AP African American Studies relate to global education trends and the dynamics between state regulation and local decision-making?

These questions aim to unravel the complex layers of this educational conflict, contributing to a broader understanding of how such controversies are framed and understood in the context of current educational trends and the ongoing interplay between state policies and local educational decision-making.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Study design

Our study utilized an unsupervised machine learning coding program in MAXQDA for topic modeling for our document analysis to explore coding possibilities for our qualitative analysis (Daenekindt and Huisman, 2020; Fesler et al., 2019). Our study’s approach allows for inductive mapping of actual lexical content without researcher bias by our position in our field or our assumptions of what we expect to find (Daenekindt and Huisman, 2020). Topic models are a collection of automatic content analyses that map the structure of extensive text data by identifying topics (Daenekindt and Huisman, 2020). This research approach consisted of two primary data collection methods: document analysis and stakeholder interviews. The results from our interviews allowed us to gain insights into the motivations, decision-making processes, and perspectives of those directly involved in the controversy. This study’s approach allowed us to triangulate data from multiple sources, enhancing the depth and richness of our analysis (Carter et al., 2014). We can discover the latent themes across all documents that allow us to find answers to our research questions (Blei et al., 2003).

3.2 Data collection

The data collection for this study involved two distinct methods. Initially, we gathered 63 articles and documents from online sources that discussed the topic of Arkansas removal. We specifically excluded documents behind paywalls that did not offer free access. To facilitate this process, we established Google Alerts using relevant keywords such as “Arkansas,” “AP African American Studies,” “History,” or “Oliva.” It is worth noting that including these keywords was crucial, as they significantly increased the likelihood of relevant documents appearing in the search results. Subsequently, the first author reviewed the content obtained through le Alerts and saved the web pages containing the identified documents. All documents meeting our criteria were included, with the sole exception being those inaccessible due to paywalls.

Using a similar approach, we also collected 47 documents that predated the Arkansas removal topic. To gather these documents, we set up alerts for keywords such as “AP African American Studies” and applied the same exclusion criteria, filtering out documents hidden behind paywalls. In addition to document collection, we conducted eight interviews involving 17 stakeholders closely associated with the Arkansas incident. We extended interview invitations to all five Arkansas superintendents; three responded and participated. Only one of the six APAAS teachers agreed to participate in the interviews, reflecting some teachers’ insecurity, particularly given that the recently passed LEARNS Act has weakened teacher tenure. Furthermore, one school permitted us to interview 10 students after obtaining parental consent.

To ensure a diverse range of perspectives, we invited additional Arkansas stakeholders to participate in interviews as part of a purposeful sampling approach (Palinkas et al., 2015). This explored whether similar themes emerged across various political and ideological stakeholder views. We extended invitations to an Arkansas historian, a Left-leaning stakeholder and activist, and a Right-leaning stakeholder and activist. We also contacted the Arkansas Department of Education (ADE) for participation, but they declined to respond to our invitations. All eight interview sessions were recorded and subsequently transcribed into documents, facilitating the creation of memos. These interview documents were then imported into our analysis system, MAXQDA, for further examination and analysis.

3.3 Data analysis

3.3.1 Document analysis

We gathered 47 documents on the former debate around APAAS before ADE removed support of Arkansas offering APAAS. We place the list of these “Pre-Arkansas APAAS” documents in the Supplementary Appendix Table 1a. We gathered 63 documents that pertained to Arkansas’s Department of Education removing support for the APAAS course in August 2023. We place the “Arkansas APAAS” document list in the Supplementary Appendix Table 1b. Lastly, we transcribed the eight interviews from the qualitative portion of our analysis, totaling speaking to 17 participants, and labeled these in the Supplementary Appendix Table 1c.

These 118 documents allowed for a content analysis of 90,733 total words. We exported and ordered these 7,334 unique words by frequency count and started grouping them into topics by meaning and word choice of text. Our approach was guided by an iterative method described by Fesler et al. (2019), where we decided which topics to discuss from the documents, selected the words to include from the documents highly associated with the issues, and used this iterative method to create our bag-of-words responses. As Fesler et al. (2019) outlined, topic modeling relies on observable terms in documents to determine the topics being discussed, which may be latent and unobservable. Throughout this iterative process, we started to uncover words we believed did not denote particular meanings within specific categories for the scope of our research. Importantly, we did not code these words into final categories. As we continued throughout our category-creating and parent codes, eight categories emerged as the main topic themes for our document analysis. From these eight categories and parent codes, we retained 419 words for our analysis, and these words were organized under their respective topic themes in the Supplementary Appendix Table 2a.

In our methodology, it is essential to note that some words in the documents were initially categorized in ways that might not immediately convey their intended meaning. To address this, we included a list of such phrases in Supplementary Appendix Table 2b. The decision to recategorize these words was based on our deep familiarity with the documents and the specific context in which these words were used (Gándara and Daenekindt, 2022). In cases where the initial categorization did not align with the overall context, we collectively determined new categories. For example, “pilot,” which would be “Curriculum,” was often used in a critical context by politicians on the right, implying that the course was not yet ready for widespread implementation.

Consequently, we categorized it under “Politics and Ideology” to capture its critical connotation. Additionally, words listed in Supplementary Appendix Table 2b were excluded from our primary content analysis as they exhibited versatility and were not limited to a single category. This approach ensured the accuracy and context-awareness of our categorization process.

3.3.2 Qualitative analysis

In addition to our document analysis, we qualitatively analyzed the data gathered from 8 interviews with 17 Arkansas stakeholders regarding the APAAS course. To facilitate this analysis, we transcribed the interviews and imported them into MAXQDA for coding and thematic exploration. This approach allowed us to examine the significance of themes about participants’ perspectives and the recurring topics identified in the documents.

For our qualitative analysis, we employed in-vivo coding (Onwuegbuzie and Ojo, 2021; Saldaña, 2021) and thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006) to scrutinize the interview responses. In the initial round of open coding, we used the interviewees’ own words as our coding basis. We applied the same parent codes, categories, and topics presented in Supplementary Appendix Table 2a during this initial open coding phase. Subsequently, we engaged in group discussions to identify commonalities among codes and their corresponding examples, ultimately consolidating them into four coherent and interpretable themes while addressing any overlaps that arose during the discussion. We upheld a reflective and critical posture throughout the process, ensuring we captured the full spectrum of the stakeholders’ perspectives and enhanced our results’ depth and credibility (Whittemore et al., 2001).

4 Results

4.1 Document analysis

4.1.1 Descriptive tabulations

To provide an overview of our 118 documents, we ran a word combination tabulation in MAXQDA to identify the most frequently occurring word combinations. Among these combinations, “African American Study,” “AP African American,” and “American Study Course” emerged as the most common. Notably, “Critical Race Theory” was the top word combination across all 118 documents, appearing in 64%. The results for the top 20 3-word combinations are presented in Supplementary Appendix Table 3a.

Furthermore, we tabulated the most frequent root combinations in MAXQDA. The most prevalent root combination in our 118 documents pertained to phrases like “the course is a pilot program” and “the course is still in the pilot stage.” These phrases often quoted Arkansas’s Secretary of Education Jacob Oliva’s statement, “The course is a pilot program and not ready to be certified as an AP course.” The second most frequent root used in the documents featured Kimberly Mundell from ADE, quoting her statement, “We cannot approve a pilot that may unintentionally put a teacher at risk of violating Arkansas law.”

4.1.2 All documents

In our comprehensive analysis of various documents related to the APAAS controversy, we examined 118 themes and topics. Our analysis yielded significant insights into the frequency of specific words and the prevalence of certain topic categories across different types of documents. We have summarized these findings in two comprehensive tables, Supplementary Appendix Tables 3b,c, presented in the Appendix.

Supplementary Appendix Table 3b details the frequency and prominence of the top 20 words across all pre-Arkansas APAAS documents, Arkansas APAAS documents, and APAAS interview documents. Key terms such as “African,” “American,” “school,” and “student” featured prominently across all documents, highlighting their central role in the APAAS discourse. The table also reveals variations in word frequency and rank across different document types, offering insights into the shifting focus areas and themes throughout the development of the APAAS controversy.

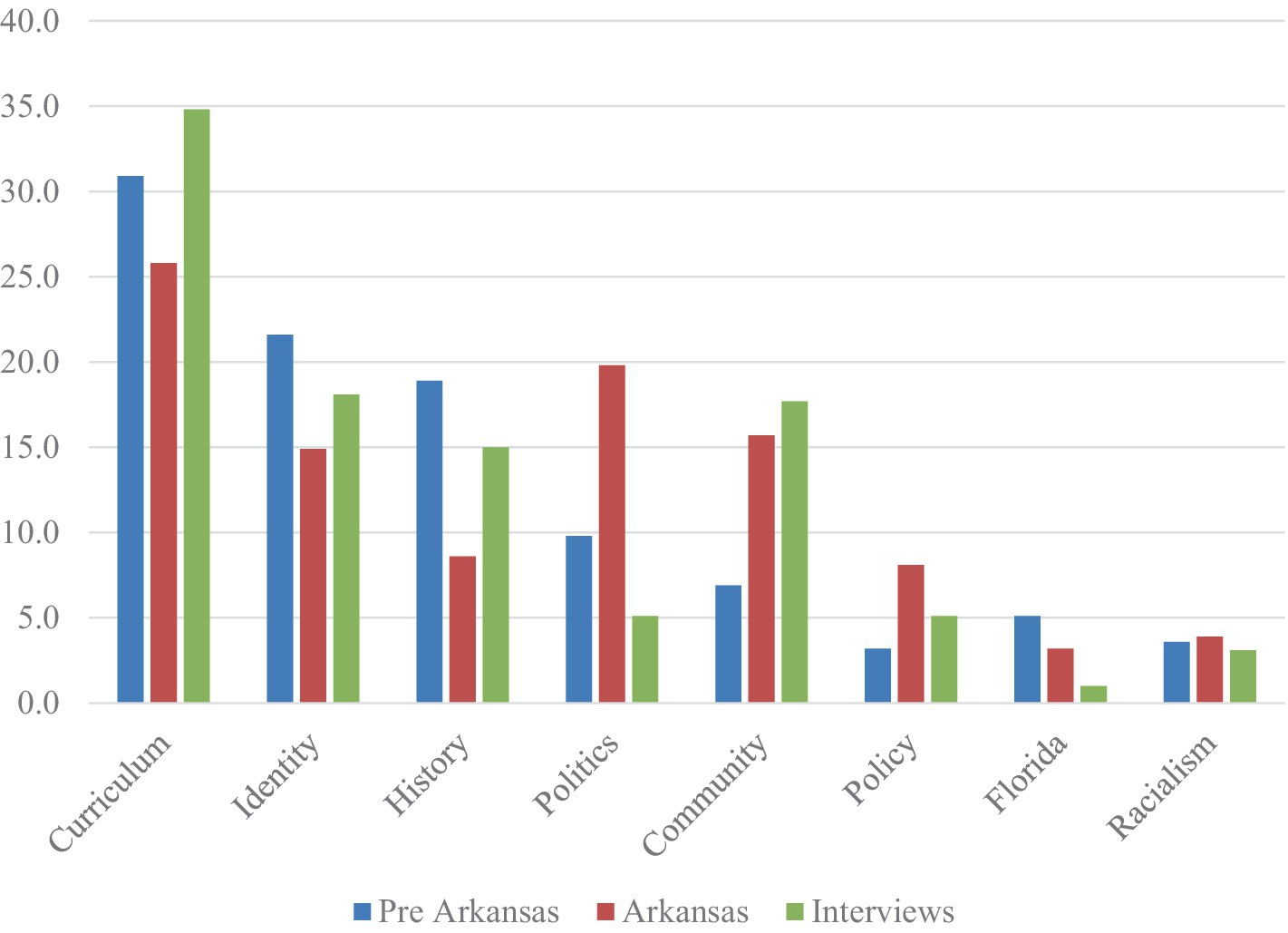

Supplementary Appendix Table 3c presents the distribution of various topic categories within the documents. The categories range from “Curriculum” and “Identity” to “Politics” and “Community.” The table shows the percentage representation of each category across all documents and in specific subsets of the document analysis (pre-Arkansas APAAS, Arkansas APAAS, and APAAS interviews). The prevalence of the “Curriculum” category across all document types underscores the centrality of educational content in the discourse. The table also indicates a significant representation of topics like “Identity,” “History,” and “Politics,” reflecting the multifaceted nature of discussions surrounding APAAS.

4.1.3 Contrasting content

Supplementary Appendix Tables 3b,c provide a detailed overview of key themes and topics from our document analysis, showcasing the complexity of the APAAS discourse. To complement this, Figure 1 will contrast the thematic variations across the three main groups. This figure offers a visual representation of the shifts in topic prominence throughout the various stages of the APAAS discussion, enhancing our dynamic understanding of the evolving narrative.

The analysis of documents related to APAAS, documents concerning the direct Arkansas attempt to remove APAAS, and interviews with Arkansas stakeholders reveals distinct themes and variations in how APAAS’s significance is portrayed within the educational context. Firstly, the theme of “Curriculum” is central across all document groups, indicating a consistent focus on educational content. However, interviews with stakeholders place a heightened emphasis on curriculum discussions (34.8%) compared to pre-Arkansas and Arkansas documents. Secondly, “Identity” is another prominent theme, but there are notable shifts in emphasis across document groups, suggesting evolving discussions and perceptions regarding identity-related aspects of APAAS. Thirdly, “History” is a central theme, particularly in the pre-Arkansas documents, although it sees a decrease in the Arkansas phase before resurging in the interviews. Fourthly, “Politics” plays a substantial role in the Arkansas documents (19.8%), indicating the influence of political factors on APAAS, but it receives comparatively less emphasis in the interviews.

“Community” emerges as a more pronounced theme in the Arkansas phase (15.7%), signifying the community’s growing role in shaping APAAS’s significance. Though less prominent, themes like “Policy,” “Florida,” and “Racialism” exhibit variations across document groups, reflecting changing focus and context. These findings provide nuanced insights into APAAS’s significance, highlighting how themes evolve and are portrayed differently within different contexts, contributing to a richer understanding of this educational issue.

4.2 Qualitative interviews

4.2.1 Theme 1: educational values and democracy

The interviews underscored education’s vital role as a cornerstone of democracy, emphasizing its responsibility to preserve democratic values. This belief aligns with historical principles advocating mandatory public education for upholding democracy. Interviewees stressed the importance of informed citizenship and viewed education as the bedrock of democracy. They emphasized prioritizing students’ welfare in educational decisions, transcending partisan politics. Education emerged as a potent tool for nurturing and safeguarding democratic societies, highlighting its timeless significance. The interviews also illuminated the delicate balance between state regulation and local decision-making, expressing concerns about blurred lines and their implications for democracy and civil rights. They emphasized transparent and accountable educational decision-making as essential for upholding democratic ideals. We place the selected quotes that describe this theme in the Supplementary Appendix Table 4a.

4.2.1.1 Superintendents

In the interviews with the superintendents, the theme of “Educational Values and Democracy” resonated strongly, with all superintendents emphasizing the crucial role of education in upholding democratic ideals. One superintendent stressed that education is the cornerstone of democracy. It is the foundation upon which our democratic society thrives.” Another superintendent highlighted the historical context, reminding us of the roots of public education, which was established to ensure an informed citizenry capable of participating in the democratic process. These sentiments collectively underscored the belief that education is the linchpin for sustaining democratic principles and fostering informed citizenship.

Furthermore, interviewees emphasized the importance of decisions in the best interest of students, transcending political considerations. They viewed education as a vital tool for preserving democracy. They were concerned about the blurred control lines between state regulation and local decision-making, seeing it as a potential threat to democracy and civil rights. Their actions in response to the incident demonstrated a commitment to doing the right thing and protecting students and staff, solidifying their role as stewards of education in nurturing and sustaining democratic societies.

4.2.1.2 Teacher and students

Insights from the teacher and students at the school district strongly align with the theme of “Educational Values and Democracy,” further emphasizing the pivotal role of education in democratic societies. The teacher’s belief that it is beneficial when school districts genuinely listen to their students and provide courses that align with their interests resonates with the concept of responsive education. The teacher said, “I believe it is beneficial when school districts genuinely listen to their students and provide what aligns with their interests.” The students’ perspectives underscore the significant impact of student voices in shaping their educational experiences. They highlighted the role of youth in ensuring that valuable courses like AP African American Studies are retained and continue to thrive. Their active involvement, including social media advocacy and petitioning, demonstrated the power of youth engagement in influencing educational policy. One student stated, “I think student voice played a large part in it. They were posting on social media a bunch, starting petitions. Moreover, once you see that the youth of your state are fighting against what the policies are, you cannot help but take notice.”

Furthermore, the students conveyed how this course added depth and perspective to their understanding of history, emphasizing the importance of a well-rounded education that presents diverse viewpoints. They believe a comprehensive education is essential, as expressed in the sentiment, “I do not think you can have a well-rounded education with one side of history.” One student passionately articulated the importance of learning about their history, recognizing that it extends beyond the narrative of slavery to include African Americans’ rich and meaningful contributions to American culture. Their enthusiasm for sharing their newfound knowledge with others reflected a commitment to becoming informed and engaged citizens; as one student stated, “I think it is essential to learn about your history, to know that we were not just slaves, that we fought back, and we did many things that are very meaningful to American culture as it is today.” In summary, the teacher’s perspective on responsive education and the students’ passionate advocacy for a comprehensive, inclusive curriculum reinforces the theme, highlighting the vital role of education in nurturing democratic values and fostering an informed citizenry.

4.2.1.3 Stakeholders

Stakeholders overwhelmingly stressed the critical role of education as a fundamental pillar of democracy. They emphasized the profound significance of an educated populace in safeguarding and preserving the ideals of a democratic society. One interviewee echoed this sentiment: “I am excited that the local community stood up. I am excited that they said we will not deal with this silliness. We are going to offer the course.” This sentiment reflected a shared commitment to ensuring that education remains a powerful tool in nurturing democratic values. These discussions harkened back to historical beliefs that advocated for mandated public education to uphold and strengthen democratic principles. Just as administrators emphasized the importance of communication in their context, our interviewees stressed that education is the bedrock upon which democracy stands. The collective commitment to informed citizenship is paramount for sustaining democratic ideals. The theme of ‘Educational Values and Democracy’ underlines the conviction that education plays an indispensable role in nurturing and sustaining democratic societies, a sentiment eloquently expressed by one stakeholder: “Public education is like the best thing I think our country has going for it.”

4.2.2 Theme 2: challenges and equity in education

In education, our interviewees engaged in a candid discussion about the theme of “Challenges and Equity in Education.” This multifaceted theme delves into the myriad challenges educational institutions and stakeholders encounter. Among these challenges is the palpable impact of political pressures on the freedom of speech within education. Our interviewees described their constraints, highlighting how political influences can stifle open dialogue and hinder the free exchange of ideas within educational contexts. Moreover, these discussions illuminated deep concerns surrounding equity in curriculum decisions, particularly in history education. Interviewees underscored the gravity of these equity issues, viewing them through civil rights and social justice lenses. They emphasized the importance of teaching an accurate and truthful account of history, especially about the experiences of marginalized communities. The theme of “Challenges and Equity in Education” thus emerges as a powerful call for educational reform, echoing those who advocate for a more equitable, inclusive, and just educational landscape. We place the selected quotes that describe this theme in the Supplementary Appendix Table 4b.

4.2.2.1 Superintendents

The superintendents illuminated the “Challenges and Equity in Education” theme with valuable insights. They firmly acknowledged the importance of aligning educational offerings with students’ preferences, echoing, “Students want to take it. The teacher wants to continue teaching it, which is a no-brainer. We are going to push forward and ensure we offer it.” This commitment to student-centered decision-making was juxtaposed with their apprehensions about the potential repercussions of their choices. As one superintendent said, “When I made the decision, I worried how that decision would impact our school district.” In navigating the intricate landscape of education, these superintendents emphasized the significance of staying well-informed and proactive, as they noted, “Being attentive to educational developments in other regions, both nationally and internationally, is crucial. It is about staying informed, being proactive, and avoiding a reactive approach to emerging challenges.” Their concerns extended to the realm of equity, particularly regarding resource allocation. One superintendent expressed, “I still have a problem with them taking state funds from an equity standpoint. You brought up from one race, and that, conversely, taking it from other AP courses, I think it is a huge equity issue.” Amid these challenges, the superintendents grappled with balancing state-level regulations and local autonomy, recognizing the delicate dance of decision-making. They echoed, “I have seen the pendulum swing in many different directions regarding how much decision-making occurs at the state level versus how much occurs at the local level.” Ultimately, their experiences and perspectives underscored the intricate web of challenges and equity concerns that education leaders face, aligning closely with addressing these issues within the educational landscape.

4.2.2.2 Teacher and students

The perspectives of both teachers and students shed light on the theme of “Challenges and Equity in Education,” emphasizing the intricate challenges that permeate the educational landscape. The teacher’s remarks, such as, “One thing I have found that is always constant is the policy process,” reflect the perpetual nature of policy dynamics that influence education. They also touched upon the nuanced nature of curricular content, acknowledging, “I know that when you look at the curriculum, there probably are a couple of lessons that someone could take out of context.”

On the other hand, the students provided poignant insights into the equity aspect of education. They expressed their desire for a more inclusive curriculum, with one student lamenting, “There are many history classes that they offer here, but they do not usually talk about black history until this, like Black History Month… I just really wanted to learn more about us.” They grappled with the paradox of learning about their history, highlighting the unique opportunity presented by the course, remarking, “It is actually kind of a little messed up in a way. I have to learn my history for my class, but it is a perfect opportunity to get a class to learn about myself.”

Furthermore, they acknowledged the controversial aspects of the course while emphasizing its role in progress, with one student noting, “I believe that this class, despite its controversial aspects and the tolerance of teaching a certain racist history, represents progress. It is like a million pieces of a puzzle coming together. Having this class is a small step forward towards reaching that place.” Their voices underscored the need for a more comprehensive and equitable approach to education, aligning closely with addressing challenges and equity concerns within the educational landscape.

4.2.2.3 Stakeholders

The perspectives of the three stakeholders resonate with the theme of “Challenges and Equity in Education” as they reflect on the intricate dynamics surrounding education policies and curriculum decisions. One stakeholder voiced concerns about the potentially dangerous implications of compromising the state’s constitutional role in setting curricula, stating, “In many ways, we have reached a real dangerous place.” They emphasized that allowing school districts to offer a particular course for local credit could erode equity and unified instruction, raising questions about the fundamental structure of the state constitution. Furthermore, the stakeholder noted the moment’s significance in shaping the nation’s trajectory, saying, “I believe this moment will be pivotal.” They suggested that this could mark a turning point away from traditional narratives and that a coalition of governors has chosen to step back and embrace the narrative of African American struggles for freedom.

Additionally, the stakeholder’s observation about the combination of enthusiasm and inertia in decision-making processes highlights the complex nature of policymaking, noting, “So yeah, they took some combination of fervor and inertia.” This complexity extends beyond education into the broader scope of human behavior, underscoring the challenges of addressing controversial educational concepts like Critical Race Theory (CRT). Lastly, the stakeholder’s acknowledgment of the challenges related to state bureaucracy highlights the practical difficulties in implementing and managing educational policies, as they remarked, “State bureaucrats are not always timely and efficient.” These stakeholder perspectives, woven into the analysis, collectively emphasize the multifaceted challenges and equity issues within the educational landscape, aligning closely with the overarching theme of addressing these intricate dynamics.

4.2.3 Theme 3: community support and advocacy

The theme of “Community Support and Advocacy” emerged prominently in our interviews, shedding light on the pivotal role played by community engagement and solidarity in shaping educational decisions. At its core, this theme underscores the profound impact of community support on educational choices. Our interviewees highlighted the unwavering backing from various community segments, including parents, community members, clergy, faith-based organizations, community groups, and local media outlets. While some adults expressed wholehearted support, students shared instances of skepticism and pushback, particularly from older individuals and peers. This widespread support bolstered the decisions and exemplified diverse stakeholders’ unity and collaborative spirit. Notably, the theme emphasizes the need for inclusive engagement with various voices, including parents, community members, and local media outlets. By involving these stakeholders, educational institutions comprehensively understand complex situations, garner invaluable perspectives, and collect vital feedback. “Community Support and Advocacy” encapsulates a resounding call for collective action, collaboration, and community involvement in addressing the challenges and opportunities within the educational landscape. We place the selected quotes that describe this theme in the Supplementary Appendix Table 4c.

4.2.3.1 Superintendents

The superintendents’ comments underscore the significance of community support and advocacy as a driving force behind their decisions. One superintendent remarked, “It is one of the most remarkable examples of collaborative educational decision-making for healthy support I have ever witnessed,” highlighting the extraordinary collaboration. They collectively praised the community’s resounding support, with another superintendent describing it as “amazing.” Their accounts reveal that the community’s backing was so strong that there was never a need to seek additional support to continue the class actively. They appreciated the diversity of voices that rallied behind them, with one asking, “How can we support? What can we do? How can we share your message?” These sentiments were further echoed by numerous phone calls and messages expressing pride in their district’s decision to move forward. However, they also acknowledged the diversity of responses, with one superintendent noting, “But not everyone is to that extent of bravery and support,” highlighting the complexities within the community’s reactions. Overall, their remarks, woven with direct quotes, align with the “Community Support and Advocacy” theme, emphasizing the crucial role of community engagement and solidarity in shaping educational decisions.

4.2.3.2 Teacher and students

In the realm of “Community Support and Advocacy,” the experiences of the teacher and students reflect a notable contrast in perspectives. The teacher shared their experience, “I have not received any negatives at all… Nobody has been unsupportive.” This positive sentiment highlights a lack of opposition or resistance to their role in teaching African American history.

On the other hand, the students’ encounters with adults and peers tell a different story. They recounted instances where they faced skepticism and pushback, with some adults deeming the class a “waste of time.” Additionally, students noted that they encountered resistance primarily from older individuals with a limited view of African American history. Among their peers, there was discouragement and advice to drop the course. However, within their families, the students found unwavering support, and they expressed a desire for a more robust dialogue and recognition of African American history. This contrast underscores the theme of “Community Support and Advocacy,” emphasizing that while adults may have differing opinions, it is crucial to acknowledge and engage in meaningful discussions around the subject to foster inclusivity and support in the educational community.

4.2.3.3 Stakeholders

The “Community Support and Advocacy” theme resonated strongly among our stakeholders, reflecting their profound involvement and dedication to the cause. As one stakeholder noted, “I was pleased to see that not only more schools allowed, I guess allowed, to continue to offer this class but that the schools very much seemed like they were going to do this for their communities.” They expressed satisfaction in witnessing more schools continuing to offer the course and noted the schools’ commitment to serving their communities. Moreover, stakeholders shared their experience of receiving numerous emails from individuals outside the state offering financial support to cover the costs of the course, reflecting a culture war aspect that national voices sometimes equal local voices (Maranto, 2022). While grateful for the support, they emphasized clarifying that state funding was unavailable for these tests. One stakeholder expressed, “People genuinely wanted to contribute to making this class a reality, not just financially, but also to validate its importance and show their support.” This outpouring of financial support underscored the commitment of people to contribute not only monetarily but also to validate the importance of the course and demonstrate their unwavering support. The stakeholders expressed gratitude for the collective efforts that emerged from a diverse community, highlighting the significance of community engagement in shaping educational decisions.

4.2.4 Theme 4: political influences on education

The theme of “Political Influences on Education” emerged as a pivotal aspect of our interviews, revealing the intricate interplay between politics and curriculum decisions. Our interviewees voiced concerns about the significant role of politics in shaping educational choices, drawing attention to the ideological influences that guide these decisions. They highlighted shifts in education governance, noting changes in the balance of power between state and local authorities. This shift raised questions about the implications of centralized decision-making. The theme also brought to light concerns about the politicization of education and the need for transparent and accountable decision-making processes. These discussions underscored the importance of depoliticizing education and ensuring that educational considerations rather than partisan interests drive curriculum choices. “Political Influences on Education” captures the multifaceted dynamics that shape the educational landscape, urging a thoughtful examination of the political forces in educational policy and curriculum development. We place the selected quotes that describe this theme in the Supplementary Appendix Table 4d.

4.2.4.1 Superintendents

The theme of “Political Influences on Education” resonated significantly among superintendents, with one noting, “It was a big political black eye for her (Sarah Huckabee Sanders),” highlighting the political dimension. However, they also recognized that “America still has leaders that, no matter their political affiliation, know what is right.” They viewed this issue as multifaceted, as another superintendent explained, “So it is an education issue. It is a civil rights issue. It is an advocacy issue. Moreover, it is a corruption issue. We superintendents just did the right thing.” Some felt that their actions had a tangible impact, slowing down a potentially aggressive push for dogmatic platform issues: “But I do feel that we slowed a process that was about to be very aggressive and assertive with some of these very dogmatic platform issues.” Despite their commitment, some superintendents described feeling constrained, as one shared, “I felt like somebody had tied my hands and feet together, put a sock in my mouth, and put me in a closet. So I did not feel like I was in America, this place of free speech, because there was some fear from my board members for me.” This emphasized the delicate balance between political influences and educational decision-making in their roles.

4.2.4.2 Teacher and students

In the “Political Influences on Education” realm, teachers and students voiced concerns about the potential for misinterpretation and discomfort associated with specific lessons. A teacher noted, “There are some lessons people who do not know could take out of context,” underscoring the need for careful consideration in the classroom. Students also expressed their perspectives, emphasizing, “It is like the comfort thing. No matter how helpful it could be to them if something is too far out of a person’s comfort zone, they will not want to accept it.” Another student suggested that the term “indoctrination” might arise from a discomfort rooted in issues related to white supremacy: “So my thing is, I think why she called it indoctrination was because a form of white supremacy has to do with feeling uncomfortable.” These remarks highlight the intricate dynamics surrounding politically influenced educational decisions, where the potential for misinterpretation and discomfort becomes a relevant factor to consider.

4.2.4.3 Stakeholders

In the context of “Political Influences on Education,” the perspectives of our stakeholders shed light on various aspects of the political landscape. One stakeholder with decades of experience lamented, “I have been watching the Arkansas State Board of Education closely for 25 years. Whether it is a Democratic or Republican administration, I have never seen anyone on the State Board of Education who knows a blessed thing about education.” Expressing concerns about the academic implications, another stakeholder remarked, “In terms of academics and educational experts, anybody that’s looked at this, I have not heard anybody say, oh, you know what, there is some questionable stuff in here.”

Additionally, there was apprehension about the potential ramifications of allowing political influence to dictate curriculum, as one stakeholder pondered, “But I am also concerned. What if we elect a governor that says, you know, geometry is not real; we should not have geometry? So, if you want to offer geometry, you can do that locally. However, we will not require that at the state level anymore.” These sentiments underscore the complexity of political influences on education, ranging from concerns about expertise and academic integrity to the potential consequences of politicizing curriculum decisions.

5 Discussion

Our mixed-methods study, incorporating document analysis and qualitative interviews, reveals a nuanced portrayal of the APAAS course controversy in Arkansas. This controversy garnered national attention and exemplified the complexities of contemporary school culture wars. The document analysis indicated shifting emphases in themes such as “Curriculum,” “Identity,” “History,” “Politics,” and “Community,” reflecting the evolving narrative of APAAS and its broader significance in various contexts. Notably, “Critical Race Theory” emerged as a dominant term in the document analysis, underscoring the political undercurrents influencing the discourse. Furthermore, our qualitative interviews with Arkansas superintendents, teachers, students, and stakeholders highlighted four significant themes: the preservation of democratic values in education, equity concerns, the importance of community support and advocacy, and the impact of political influences. These themes align with the findings from the document analysis, painting a complex picture of the motivations and perceptions surrounding the ADE’s withdrawal of support for APAAS. Together, these findings point towards a broader dialogue that intertwines factual knowledge, educational choice, and the tension between state regulation and local autonomy in shaping the future of educational policies and practices.

5.1 Differing themes in discourse

RQ1: What prominent themes emerge from the content analysis of documents related to AP African American Studies (APAAS), documents about the Arkansas attempt to remove APAAS, and interviews conducted with Arkansas stakeholders regarding APAAS? How do these themes differ in their portrayal and understanding of APAAS’s significance within the educational context?

The document analysis of our study, encompassing 118 documents, highlights the diversity of discourse and themes surrounding the APAAS controversy. The differing word combinations underscore the deep political and ideological dimensions across sectors. The descriptive tabulations focus on the course as a pilot program, reflecting concerns about its readiness and compliance with state laws. The central theme of “Curriculum” consistently highlighted the focus on educational content across all document types. At the same time, the prominence of “Identity,” “History,” and “Politics” varied, reflecting the multifaceted nature of the debate.

Miles (1978) assertion, “Where you stand depends on where you sit,” is particularly relevant in understanding the results for our RQ1 in our study. Political leaders like Florida Governor DeSantis and Arkansas Governor Huckabee Sanders play pivotal roles in shaping educational policies as they navigate the balance between portraying history accurately and fostering a sense of national connection and political agency among students. This resonates with the findings from our documents, where “Critical Race Theory” and other politically charged themes emerged prominently. Our study aligns with the perspectives of African American critics and proponents of institutional racism-based approaches (Woodson, 2021; Yancey, 2022), highlighting the ongoing debate about the role of critical theory in education. This debate is crucial in understanding the political influences on education, as our analysis indicates the APAAS decision’s impact on Arkansas’s educational profile, particularly among non-conservative circles. Politicians have a legitimate role in shaping education, but this incident highlights the potential dangers of political interference in curriculum decisions.

Moreover, echoing Zimmerman (2022) and Maranto (2022), the evolving nature of school culture wars is evident. As suggested by Kogan (2022), with fewer Americans having direct ties to schools, perceptions of education increasingly depend on ideological stances rather than on-ground realities. This ideological lens is crucial in understanding the thematic variations in our study, from the emphasis on “Curriculum” and “Identity” to the significant role of “Politics” and “Community” in shaping the discourse. Our analysis also points towards the potential resolution of these conflicts through educational choice, a concept supported by scholars like Hess (2023) and McCluskey (2022). Allowing students to choose between different educational approaches, be it African American Studies or a more traditional history course, offers a way to navigate these complex cultural and political dynamics. The differing themes in the discourse surrounding the APAAS controversy reflect the intricate relationship between education, politics, and community. This relationship underscores the need for a nuanced approach in educational policy-making that considers the diverse perspectives and historical contexts influencing the current educational landscape.

5.2 Motivated by students and communities

RQ2: What motivated Arkansas districts to continue offering AP African American Studies despite state opposition?

RQ3: How did community engagement and public sentiment influence the schools’ decision to maintain AP African American Studies?

Our qualitative interviews reveal a deep commitment among Arkansas districts to offering APAAS, motivated by a profound respect for educational values, democracy, and the well-being of students. This commitment addresses our RQ2 and RQ3 by highlighting the driving forces behind the decision to continue offering APAAS despite state opposition and the impact of community engagement on these decisions.

The theme “Educational Values and Democracy” was recurrent in our superintendent interviews. They viewed education as a foundational element of democracy, echoing the historical principles that mandate public education to uphold democratic values. This perspective aligns with the observations of Miles (1978), emphasizing that educational decisions should transcend political affiliations and focus on what is fundamentally suitable for the students and the democratic process. Even in the face of state opposition, the superintendents’ determination to uphold these values underscores their commitment to an informed citizenry and nurturing democratic societies.

Teachers and students echoed these sentiments, emphasizing the importance of responsive education that aligns with students’ interests and promotes an understanding of diverse historical perspectives. The student’s active involvement in advocating for the course through social media and petitioning highlights the power of student voices in educational policy decisions. This advocacy, as noted by one student, played a significant role in retaining the course, demonstrating the influence of youth engagement in shaping educational outcomes.

Stakeholders reinforced the importance of community support in educational decisions. Their commitment to upholding educational values and democracy was evident in their enthusiastic backing for the course. This aligns with the work of Woodson (2021) and Yancey (2022), who argue for a balanced approach to education that acknowledges different perspectives and upholds democratic values.

The theme of “Challenges and Equity in Education” revealed concerns about the impact of political pressures and the importance of equity in curriculum decisions. Superintendents and teachers highlighted the necessity of aligning educational offerings with students’ preferences and the challenges of navigating state-level regulations versus local autonomy. These concerns reflect the broader educational landscape, where politics and policy intertwine, often leading to complex decision-making scenarios.

“Community Support and Advocacy” emerged as a vital theme, with widespread backing from various community segments. This support was crucial in bolstering the decisions made by educational leaders, exemplifying the unity and collaborative spirit among diverse stakeholders. This theme echoes the arguments of Hess (2015) and Maranto and Wai (2020), emphasizing the need for educational choices that reflect community norms and preferences.

Finally, “Political Influences on Education” highlighted the role of politics in shaping educational choices. This theme is particularly pertinent to our study, reflecting the tension between political influences and the educational mission. Stakeholders and educators expressed concerns about the politicization of education and the necessity for depoliticizing educational decisions.

In summary, the motivation to continue offering APAAS in Arkansas districts was deeply rooted in a commitment to educational values, democratic principles, and the well-being of students. Community support played a pivotal role, providing a solid backing for these decisions. The findings suggest that educational decisions, while inevitably influenced by political factors, are most effective when they prioritize student welfare, uphold democratic values, and are supported by the community.

5.3 Mirroring global trends

RQ4: How does Arkansas schools’ defiance in offering AP African American Studies relate to global education trends and the dynamics between state regulation and local decision-making?

Our analysis of the defiance by Arkansas schools in offering APAAS provides a microcosm for understanding broader global education trends and the dynamics between state regulation and local decision-making. In democracies, public schools are typically governed by public bodies, indicating that elected officials and their appointees play a significant role in curriculum decisions. Such trends are not unique to Arkansas or the United States but resonate globally, where political agendas often intersect with educational policies. The defiance by Arkansas schools in offering APAAS despite state opposition embodies this tension. It reflects a growing global trend where local educational authorities and communities increasingly assert autonomy in response to top-down regulatory approaches. This dynamic is evident in the words of African American critics like Woodson (2021) and Yancey (2022), who advocate for a balanced educational approach that accommodates diverse perspectives without succumbing to political pressures.

The situation in Arkansas also exemplifies the challenges in balancing accurate historical portrayal with fostering national connection and political agency in education. The debate over APAAS in Arkansas mirrors global discussions on how history and identity are taught in schools, often influenced by political ideologies and cultural narratives. Our findings suggest that resolving such conflicts might require innovative approaches like the one proposed by Lindblom and Cohen (1979), where the role of social scientists is to elevate the level of debates and bring analytical tools and facts into discussions. In the case of APAAS, few participants in the controversy might be aware of the differences between African American history and more activist-oriented African American Studies courses, reflecting a global issue where ideological biases can sway educational content.

Furthermore, the defiance in Arkansas speaks to the need for more localized control in educational decisions, as theorists like Elazar (1967) advocated. This approach aligns with global trends towards educational decentralization, allowing for experimentation and adaptation to local community norms. It also resonates with the suggestions of Hess (2023), advocating for choice within and between schools to resolve educational conflicts. In conclusion, the situation in Arkansas with APAAS indicates broader global education trends where the interplay between state regulation and local autonomy is increasingly prominent. As school culture wars continue, as noted by Zimmerman (2022), the resolution might lie in empowering local decision-making and embracing diverse educational models to cater to varied community needs and perspectives. This approach, while challenging, holds the potential for creating a more balanced and inclusive educational landscape, both in the United States and globally.

5.4 Recommendations

To address these challenges, we propose a multifaceted approach to make legitimate political controversies like the one over APAAS in Arkansas more productive and less polarizing. First, to constructively engage with political controversies such as the APAAS debate in Arkansas, a nuanced approach is necessary to enhance productivity and minimize polarization. Echoing Lindblom and Cohen (1979), the function of social scientists should be to elevate the quality of discourse, employing analytic tools and introducing often-neglected facts into the conversation. A significant aspect of this controversy is the lack of widespread understanding of the distinctions between African American history and the more activist-driven African American Studies, like the APAAS program.

A thorough review of the College Board (2023) APAAS frameworks reveals selective inclusions and omissions. Notably absent is the recognition of African Americans as one of the most devout demographic groups in the West (Carter, 1991), and the monumental role of Black churches in civil rights movements. Additionally, the frameworks overlook the history of interracial collaboration that has been pivotal to progress, such as the formation of abolitionist groups, the construction of HBCUs, and the Rosenwald Schools that advanced literacy (Yancey, 2022). Such omissions perpetuate a zero-sum narrative, which activists like Kendi (2019) have been known to advance, and which has been subject to critique (Yancey, 2022). The exclusion of figures like Marcus Foster, the first Black superintendent of a major city school system who was tragically assassinated and did not align with the Black Panthers—a group portrayed positively in the frameworks—also points to a biased historical representation. The near absence of Black intellectuals and politicians from centrist or conservative viewpoints, contrasted with the prominent inclusion of figures and collectives with limited mainstream impact, further skews the narrative presented in APAAS courses.

Highlighting these concerns is not an argument against the offering of APAAS but rather a call for a resolution through educational choice. By allowing students to engage with both African American Studies and a more traditional African American history course, educational institutions can foster a richer and more comprehensive historical understanding. This would allow for a more inclusive representation of African American history, accommodating a fuller spectrum of perspectives and contributions.

Secondly, adopting a local control approach in educational decision-making (Elazar, 1967) can lead to a more representative and responsive educational system that aligns with the values of the local community. This approach questions the way Arkansas state government mandated decisions upon local school districts without consulting them. Prioritizing local school districts and providing choices within schools (Hess, 2023), can create a more inclusive and diverse educational environment, while also preventing conflicts.

Finally, as McCluskey (2022) suggests and as seen in Europe (van Raemdonck and Maranto, 2018), expanding school choice between schools can be an effective way to address long-standing educational conflicts. By providing a variety of educational options, ranging from activism-based to knowledge-based curricula, schools can cater to diverse educational preferences and reduce polarization.

5.5 Limitations

While its approach to examining the Arkansas APAAS controversy is comprehensive, this study has limitations. First and foremost, focusing on a single state’s response to a specific educational policy may limit the generalizability of our findings to other contexts or broader educational trends. Additionally, while valuable, our reliance on document analysis and qualitative interviews inherently presents a subjective lens through which the controversy is interpreted. Although insightful, the views and insights of superintendents, teachers, students, and stakeholders may not capture the full spectrum of opinions and experiences related to the APAAS course. Furthermore, our analysis may not have fully explored the potential long-term impacts of the decisions made by Arkansas’s education department and local schools, thus offering a somewhat limited temporal perspective.

6 Conclusion

The APAAS controversy in Arkansas, as revealed by our study, highlights the complex interplay between state policymaking and local educational autonomy. This situation reflects broader trends where decisions made at higher levels of governance can have unforeseen and sometimes unwelcome impacts at the grassroots level. Schools’ resistance to state decisions underscores a growing sentiment that local educational needs and perspectives may not align with broader political agendas.

Our analysis demonstrates that while state policymakers hold legitimate authority in shaping curricula, their decisions may inadvertently undermine fundamental educational values such as equity, informed citizenship, and respect for local decision-making preferences. This misalignment, particularly evident in the Arkansas case, has negatively increased the state’s educational profile, as perceived by non-conservative stakeholders.

In conclusion, while school culture wars are not new, as Zimmerman (2022) illustrates, they are likely to persist. However, by adopting these approaches, there is potential to make these controversies more productive and less polarizing, aligning educational policies with communities’ diverse needs and values. This approach addresses the current dilemma in Arkansas and sets a precedent for managing similar conflicts in the evolving educational landscape.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of identifiable data. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to c3JtMDQxQHVhcmsuZWR1.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Arkansas Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

SM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RM: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge and thank the participating schools and stakeholders for their contributions to our study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1369770/full#supplementary-material

References

Allen, D. (2015). Our declaration: A reading of the declaration of Independence in defense of equality. New York: W.W. Norton.

Allison, G. T. (1971). Essence of decision; explaining the Cuban missile crisis. Boston Massachussetts: Little Brown.

Blei, D. M., Ng, A. Y., and Jordan, M. I. (2003). Latent Dirichlet allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 3, 993–1022.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa