- 1Departamento de Terapia Ocupacional y Fonoaudiolgía - Facultad de Salud, Universidad de Antofagasta, Antofagasta, Chile

- 2Departamento de Educación Diferencial - Especialidad Educación de Personas Sordas, Facultad de Filosofía y Educación, Universidad Metropolitana de Ciencias de la Educación, Santiago, Chile

Introduction: The incorporation of narratives in Chilean Sign Language enriches classroom practices, preserving and transmitting Deaf culture. However, that within the Chilean educational context, the narratives used for instructing Deaf students are translations from written Spanish. This study aims to describe and analyze the narrative structure and the use of Highly Iconic Structures in these translations conducted by Deaf co-teachers into Chilean Sign Language.

Method: The research adopts a qualitative approach and a descriptive case study design, involving two deaf teachers from an Inclusive Education Program in a school. The data analyzed focus on the video-recorded LSCh translations of the short story “The Greedy Squirrel”. Manual annotations were made on the corpus gloss transcription to first segment by narrative structure for description and then to identify the transfer operations.

Results: The co-teachers make variations to the narrative structure of the translated text and incorporate specific visual-gestural elements such as the change of narrator to first person; the 45% of the translation is composed of transfer operations.

Discussion: These findings suggest that the variations in structure and the new visual-gestural information provided by the co-teachers reflect their understanding and use of sign language narrative norms for translation. The use of transfer operations enhances the storytelling experience, although it cannot be conclusively stated how and why teachers decide to use them in translation. The results are limited, as they require comparison with other corpora on translations from written Spanish to LSCh and software-assisted analysis to standardize data, which implies further research on the topic. For now, it is essential that the time allocated to the preparation of educational materials in LSCh be more extensive and better planned.

1 Introduction

The translation of stories from written language to sign language involves a process that goes beyond mere linguistic transposition. This process requires not only understanding and recognizing the communicative and cultural aspects of both languages, but also developing intercultural sensitivity and relational empathy toward the different linguistic and cultural communities involved. These considerations are essential in any translation process, whether between spoken languages or from written Spanish to Chilean Sign Language (LSCh). Specifically, in the context of sign language translation, it is crucial to adapt visual and gestural elements to reflect the cultural and emotional context of the story accurately. This approach underscores the relationship between communication, culture, education, and inclusion for Deaf people (Vite and Fernández-Viader, 2017; Yasar-Akyar et al., 2022). Furthermore, engaging with the Deaf community ensures that translations are culturally appropriate and accepted by the target audience (Chen, 1997; Cuxac, 2000).

The act of telling children's stories in LSCh sign language their translation from written Spanish implies that Deaf co-teachers, support professionals in the educational fields who have the task of transmitting LSCh and Deaf culture, must use not only their linguistic skills and cultural experience of their own language but also apply cognitive, behavioral, and affective skills in the interaction with the second language. This intricate process of transferring stories across cultures aligns with the concept of cross-cultural translation, where cultural nuances, idiomatic expressions, and context-specific meanings are adapted to fit the cultural framework of the target language (Chen, 1997).

Furthermore, this process aligns with Hans Vermeer's Skopos Theory, which emphasizes the significance of purpose and context in translation. According to Vermeer, translation is not merely a linguistic transposition, but an intentional action designed to fulfill a specific objective within a particular context. Consequently, the function that the translated text is intended to serve for the target audience guides the translator's decisions, ensuring that the translation is not only linguistically accurate but also culturally appropriate and effective for the intended audience (Reiß and Vermeer, 2015). This approach enables the translation of children's stories into Chilean Sign Language (LSCh) to adapt not only linguistically from written Spanish but also to consider cultural nuances and the educational needs of Deaf children, thus ensuring the effective transmission of both content and culture (Chen, 1997).

In this sense, Deaf co-teachers must have this competence, which is enhanced by being native LSCh signer and translating from written Spanish as a second language. Among the strategies, co-teachers rely on images to understand the message and meanings of the written text when reading a story. They consult teachers and/or interpreters when they are not sure of the meaning of terms or situations to express them in their native language to ensure an accurate translation. Therefore, a collaborative approach is proposed with possibilities of knowledge transfer that enhance the relationships of intercultural sensitivity between sign language and written language with the interaction between Deaf and hearing people in the classroom.

The perspective of Eichbaum et al. (2023) is more flexible and broader, highlighting that no single form of empathy can be applied universally. Thus, instead of adopting an egological approach focused on the individual, they advocate an ecological approach to relational empathy that considers the cultural and social context in which the interaction occurs. According to this perspective, intercultural empathy is not simply about developing a personal understanding of cultural differences, but about actively adapting to the specific context and needs of each cultural interaction. This involves recognizing and valuing cultural differences in the expression and perception of empathy, as well as the importance of cultural sensitivity and adaptability in intercultural communication.

This means that Deaf co-teachers, as well as native LSCh signers should be competent in intercultural sensitivity. When translating and narrating a story from written Spanish as their second language, they must consider not only the literal translation of the words, but also the adaptation of expressions, signs, and intonation appropriate to reflect the cultural and emotional context of the story. They must be sensitive to the cultural differences between written Spanish and LSCh sign language, making sure to faithfully transmit the message and emotions of the story in the visual-gestural format of sign language.

The competence in different narrative structures of Deaf people is expressed visually through sign language and is preserved and transmitted through video recordings. The incorporation of narratives in LSCh enriches classroom practices, preserving and transmitting Deaf culture (Martínez and Astrada, 2010; Reyes, 2019). However, the authors of this article have identified that the reality of the educational context in Chile is that the narratives used in teaching for the Deaf are mostly translations from written Spanish taken to video formats, with the subtitle “accessible for the Deaf” or interpreted in sign language and with accessibility tools for Deaf people, such as the initiatives of the Ministry of Education of Chile, the University of Chile and Natacha Valenzuela López, a journalist recognized for producing content in LSCh, including video storybooks.

The Ministry presents a compendium of curricular videos in LSCh in the areas of Language and Communication, Mathematics, Natural Sciences, History, Geography, and Social Sciences; these videos initially began with 40 in 2017 and have increased significantly each year (Ministry of Education of Chile, 2017, 2024). The visual material is considered as supplementary and supports content from 1st to 12th grade. Although the material covers all levels of primary and secondary education, and the Ministry periodically creates new material in collaboration with interpreters, Deaf individuals, and teachers, it does not manage to cover all contents and remains within the framework of inclusive education.

The production of visual material for Deaf individuals has also been carried out by other organizations. For example, in 2021, the University of Chile presented a series of twelve video stories translated into LSCh about astronomy entitled Cuentos con-ciencia, and the journalist Valenzuela was a creator of accessible content, including video books in LSCh (Valenzuela López, 2024).

Although these translations of curricular material and children's literature into LSCh represent progress in providing access to information, they can also create communication barriers and contribute to language deprivation when they are the only teaching materials available, that is, in the absence of narratives created and produced directly in LSCh as well as representations that reflect the and cultural aspects of Deafness in Chile. The situation becomes more complex in the school context when educational materials are available mostly in written Spanish, from the dominant hearing culture, and co-teachers and interpreters must translate these materials on the spur of the moment during the daily teaching process at the school.

Studies have shown that language deprivation in Deaf people influences narrative structure and the use of enriched iconic structures (Hall, 2017; Humphries et al., 2012). Language acquisition for deaf children is crucial, as it is acquired within dyadic deaf mother-deaf child relationships, but in the case of deaf infants with hearing mothers these relationships are restricted and become formalized in bilingual schools (Cuxac, 2000; Cheng et al., 2019; Hall et al., 2017; Pérez Aguado and Fernández-Viader, 2018). However, educational challenges persist for Deaf adults with limited understanding of written language as a second language, due to the late acquisition of sign language and consequently a restricted linguistic base that does not allow always them to make complex mental representations to enable them to translate confidently from written Spanish (Prinz and Strong, 1998; Acuña Robertson et al., 2012).

Language deprivation in Deaf people refers to the lack of timely access or exposure to rich, complete language during early development, including the denial or omission of strategies or methods to facilitate timely access. This phenomenon may be associated with factors that contribute to its manifestation. For example, Hall (2017) highlights the risk that language deprivation impedes sign language development in Deaf children, resulting in deficits in their language acquisition. Humphries et al. (2012) emphasize the importance of allowing the use of alternative approaches to language development in Deaf children, suggesting that the exclusion of these methods may contribute to language deprivation.

Language deprivation in Deaf people can affect linguistic structure and, consequently, comprehension and storytelling. Cheng et al. (2019) explore the effects of language deprivation on brain connectivity and find differences in language pathways between Deaf people who acquired sign language early and those who learned it later. These findings suggest that the lack of access to a complete language from birth may affect language-related brain organization and, therefore, the linguistic structure of Deaf people. This can influence their ability to understand and tell stories effectively, as language deprivation may limit their proficiency in sign language and affect their ability to express complex ideas and abstract concepts in narrative form.

Given this problem, co-teaching emerges as a strategy endorsed by the Ministry of Education of Chile (2009, 2013) to promote inclusion and learning (Rodríguez, 2014). Deaf co-teachers play a fundamental role as linguistic models, promoting Deaf culture, awareness of sign language and the integration of its use in educational environments (National System of Labor Skills Commission, 2018). Thus, as in the implementation of curricular management tools, teaching planning, classroom didactics (kinesthetic/tactile strategies and auditory/visual) and evaluation-monitoring of the use of the LSCh are essential (Rodríguez, 2014). Co-teaching serves as an inclusion tool, reducing communication barriers for the Deaf community in education (Ustrell-Ibarz, 2015). It is necessary to explain that co-teachers in Chile often lack teacher training and their evaluation as co-teachers, specifically as linguistic models, is primarily based on their level of proficiency in sign language.

While the integration-inclusion model in Chile involves Deaf co-teachers as educational aides, bilingual education offers distinct advantages, such as the opportunity to have Deaf teachers in various subjects who directly teach Deaf students in sign language. Bilingual education involves the use of sign language as the first language (L1) and the oral language written format as the second language (L2), allowing deaf students to acquire linguistic and cognitive competencies in both languages (Grosjean, 2008). Additionally, bilingual education promotes the social and cultural inclusion of deaf students by valuing and respecting their linguistic identity (Humphries and Allen, 2008; Livingston, 1997). This model also facilitates the use of methodologies and materials adapted to the specific needs of deaf students, significantly improving their educational experience. Furthermore, bilingual education encourages the participation of a multidisciplinary team, ensuring comprehensive and effective support for the academic and personal development of deaf students (Humphries and Allen, 2008). In this sense, it is essential to empower Deaf people in educational spaces, highlighting their role as teachers and valuing the identity of Deafness to move toward bilingual education (Morales-Acosta, 2019).

The narrative structure in sign languages, characterized by its rich organization and pivotal role in discourse cohesion and coherence, aligns with the role of Deaf co-teachers in transmitting Chilean Sign Language and Deaf culture within the educational field. These professionals work across various educational settings, particularly in initial education, where sign language acquisition and reinforcement are crucial for the educational development of Deaf students. Their experiences as Deaf individuals contribute significantly to this task. The recent certification of this occupation in 2018 by the Commission of the National System of Labor Skills underscores its emergence as a distinct professional profile associated with the educational sector in Chile, with only one training program available in the country. By 2024, there were forty-two certified co-teachers registered throughout Chile, highlighting the growing importance and presence of these professionals in the educational landscape (National System of Labor Skills Commission, 2018).

Narrative structure in sign languages is characterized by its rich organization and structure, pivotal for the cohesion and coherence of discourse. This organization not only follows a temporal sequence of events but also incorporates specific visuo-gestural elements that enrich the narrative and facilitate comprehension. Narrative discourse is defined as the situation in which the sender narrates a sequence of events, whether real or imaginary, following the temporal order in which they are presumed to have occurred (Dahl, 1985, p. 112). This means that a narrative aims to depict a succession of events, providing temporal and structural coherence, regardless of the nature of the story being told. The nature of narrative discourse, both in the temporal sequence of events and the organization of details, is intimately linked to the coherence and cohesion of the text. Coherence refers to the semantic connection that encompasses the entire narrative content, while cohesion is concerned with establishing links between various discursive structures, connecting elements, and ensuring the flow of the story (Halliday and Hasan, 1989; Morales López et al., 2019).

Two types of structures have been identified in the narratives of Deaf people: classic and event-based, allowing Deaf narrators to structure a story with cohesion and coherence, ensuring understanding by the interlocutor (Otárola and Crespo, 2016). Cohesion and coherence in sign language narrative, developed at the visuo-gestural level, manifest through the repetition of lexical elements, with or without discourse topics. Topic persistence, directional use of gaze, and spatial modification as a role change, are elements that strengthen referential cohesion, simultaneously contributing semantic nuances to the discourse (Morales López et al., 2019).

Manual discourse markers in Venezuelan Sign Language (LSV), as described by Pérez (2006), play fundamental roles in narratives. They function as elements that emphasize, organize, and structure information in visual stories, providing crucial signals for the production and comprehension of the narrated stories. These markers not only add emphasis or structure to the narrative but also function as linguistic bridges that connect parts of the discourse, clearly delineating changes in sequence of events within the narration.

In Swedish Sign Language (SSL), the introduction of referents in narrative texts is distinguished using descriptive nominal phrases or the use of proper names, as pointed out by Ahlgren and Bergman (1993). These linguistic elements serve as a central axis for structuring visual narratives, allowing the precise identification and location of characters, objects, or situations within the story. The use of detailed descriptions or specific names provides accuracy and details in the delineation of key elements, facilitating the visualization of coherence and understanding in the narrative plot.

Massone and Machado (1994) emphasize the importance of the visuospatial organization of signs in sign languages narratives. They suggest that this organization is formed through a matrix that encompasses segmental and articulatory features. Segmental characteristics are linked to elements such as shift, stopping, movement, and speed during manual expression, including gesticulations and hand and finger movements. Articulatory features refer to the hand's arrangement, location, direction, orientation, and non-manual elements corresponding to facial and body expressions.

Drawing from Massone and Machado's (1994) emphasis on the visuospatial organization of signs in sign language narratives, one can leverage Cuxac's (2000); Cuxac (2001) theory of Highly Iconic Structures (HIS) and the utilization of transfer operations. This theory elucidates how sign languages employ iconic expressions and cognitive operations to vividly represent narratives at the visuospatial level. Precisely, one of the competencies of Deaf co-teachers involves Cuxac's (2000); Cuxac (2001) theory on Highly Iconic Structures (HIS) and the use of transfer operations that illustrate how sign languages utilize iconic expressions and cognitive operations to depict narratives vividly. These structures allow for a deeper connection with the audience, demonstrating the inherent adaptability and expressiveness of sign languages in narrative discourse. The analysis of HIS in narratives, especially within the LSCh, provides insights into the unique challenges and opportunities or Deaf co-teachers in accompanying Deaf students in inclusive educational environments.

For the analysis of HIS it is necessary to refer to classifiers, which are elements closely related to specifiers, the latter concept being linked to size and shape specifiers studied by Klima and Belluggi (1979). These elements allow the development of complex forms that Cuxac calls descriptors, and in HIS, he describes them as transfer operations of size and/or shape (Bras, 2002). Classifiers are visualized as closed homogeneous classes of handshapes grouped according to their shared referential property (Cuxac, 2000). In other words, they can represent classes of objects based on the characteristics of the referent. Cuxac's transfer operation structures are based on their iconicity, attempting to see the visual similarity between the referent and the sign; they are not conceived as closed classes like classifiers but as non-discrete signs. Transfer operations are complex structures involving both manual and non-manual elements governed by the linguistic system's rules. HIS are mental operations where the functions of visuogestural discourse are identified to present the dimensions of the real world in the presentation of an utterance (Sallandre and Cuxac, 2002). These structures appear in stories, tales, narrations, and spontaneous situations in the discourse of Deaf signers.

Cuxac's presents HIS, fundamental in this type of discourse, as recurring manifestations that follow intrinsic rules of these languages. These HIS, defined as meaningful iconic expressions, represent the iconic intent by showing, demonstrating, and illustrating, acting as structural traces in sign language discourse. Cuxac identifies the transfer operations as functional groupings of cognitive processes underlying these structures, allowing the transfer of experiences from the signer to the discourse in sign language. These cognitive operations enable the expression of spatial referential constructions and descriptions of places through the three-dimensional signing space. It is necessary to differentiate between classifiers and HIS, the difference lies in the function and form of construction of the signs: classifier signs focus on representing elements in space and spatial relationships, while signs with highly iconic structures seek the visually similar representation of objects, actions, or concepts.

For transfer operations in sign languages to be understandable to interlocutors, the presence and specific use of gaze are required. Each type of transfer, identified by Cuxac (2000) in his study, relates to a specific gaze direction for proper interpretation. Cuxac points out three types of transfer operations: transfer of form and/or size, representing and describing dimensional aspects of objects, characters, or places, devoid of any procedural elements; transfer of situation, recreating scenes in the space, as if observing the scene from afar; and transfer of person, where the speaker identifies with a transferred character, whose gaze and facial expressions characterize the action (Sallandre and Cuxac, 2002).

The transfer of situation and transfer of person can be combined, resulting in what is known as double transfer. These double transfers have two main characteristics: (a) they enable the representation of an action in transfer of person linked to a fixed reference space, usually indicated by the non-dominant hand. In bimanual signs, which are performed with both hands, one hand is the dominant hand, also called active, and the other is the passive or non-dominant hand. The active or dominant hand is the one used to perform natural actions, such as writing, picking up objects, etc. The passive or non-dominant hand serves as support. (b) They are related to transfer of situation by representing movements or displacements of an actant, where the dominant hand indicates the transferable character's movement with respect to the body, functioning as a reference point. In this case, the transferred character can move in relation to a stable locative (Cuxac, 2000; Sallandre and Cuxac, 2002).

Cuxac (2000) identifies that these HIS have a constant presence in the narratives of Deaf people, and transference operations can be analyzed not only in French sign language (LSF), but in any sign language. These HIS play a fundamental role in marking coherence in discourse, working together with standard signs and being highly iconic. Standard signs establish the thematic context, while highly iconic signs add an additional layer of details and enrichment to the narrative. This close connection between both types of signs broadens the communicative spectrum, allowing greater depth and clarity in expression within sign languages.

The push toward creating narratives tailored for the Deaf community confronts traditional communicative norms, which are established by the hearing majority. These norms typically involve linear storytelling with a strong emphasis on spoken or written text, which may not fully accommodate the visual-spatial nature of sign languages (Hall, 2017; Cheng et al., 2019), and thus underscoring the importance of thorough training for Deaf co-teachers, as well as for sign language interpreters and educators specializing in Deaf studies. Such training should encompass the diverse types, structures, and forms characteristic of sign language storytelling (Morales-Acosta et al., 2020). This endeavor to craft narratives in the Deaf community's native language represents an act of resistance, which goes beyond the mere preservation of identity to become a transformative force that challenges entrenched views on Deaf communication and cultural representation within broader society.

While such initiatives are acknowledged as ideal, the reality for the Deaf community in Chilean schools tells a different story. Here, access to authentic narratives is limited. Educational materials, including children's books, are often hastily translated from written Spanish by interpreters or co-teachers. Against this backdrop, we propose a critical analysis of the narrative structures employed by Deaf co-teachers in Chilean Sign Language (LSCh), comparing these with the original texts.

The primary goal is to investigate the nature of translating a widely utilized Spanish children's story into LSCh for educational use among the Deaf, focusing on the dominant spoken language. This exploration aims to identify potential barriers or enablers to accessing information and communication in the educational setting for Deaf co-teachers and by extension Deaf students. Furthermore, this analysis aligns with the burgeoning research opportunities in Chile concerning bilingualism in the Deaf community (having written Spanish as their second language), essential interpretation and translation strategies, and the linguistic, cultural, and contextual awareness required.

2 Materials and method

This study adopts a qualitative research approach with a design based on the descriptive case study scope.

2.1 Population and sample

The choice of school as the context for selecting participants in this study was deliberate due to its inclusion of Deaf students and the team of professionals from the School Integration Program (PIE) of the Ministry of Education of Chile. This team consists of four interpreters and two Deaf co-teachers, with approximately 16 Deaf students enrolled at the institution and assigned to the PIE.

Sample selection was done by convenience, choosing to include participants who were easily accessible and willing to participate. This approach was based on proximity and availability of subjects, without attempting to make the sample random or representative of a broader population. Such a strategy allowed for faster and more resource-efficient data collection but carries inherent limitations regarding the generalizability of the results. The choice of this methodology was justified by the context and specific objectives of the research, prioritizing practicality over representativeness, which is characteristic of convenience samples (Yin, 2009).

The sample population comprised two Deaf co-teachers of the LSCh who are considered native signers within the context of this study. For the purposes of this research, a “native signer” is defined as an individual who has achieved fluency and deep cultural understanding of LSCh, regardless of the age at which they began learning the language. This includes individuals who, despite starting to learn LSCh later in life, have immersed themselves in the Deaf community and achieved an elevated level of proficiency and cultural competence. Co-teacher 01, for example, began using LSCh with Deaf peers at an early age, while Co-teacher 02 began learning LSCh formally at the age of sixteen and has since become deeply integrated into the Deaf community and its cultural practices. Their professional relationship extends beyond individual responsibilities, as they collaborate closely within the same instructional team.

Co-teacher 01: 43 years old, daughter of hearing parents, with no other deaf family members. As a child she was forced to learn to speak orally at school, but when she went to the bathrooms with her Deaf classmates, they used sign language, so she began to acquire the language with them. With her family she communicates orally, and she lipreads. She began studying education in a professional institute affiliated with a university. She has been working as a co-educator for about 10 years.

Co-teacher 02: 43 years old, seven years of co-teaching in the inclusive school (2016–2023) and is part of the Center for Deaf Educators of Chile—CES. She is the only Deaf person in the family, although her mother became deaf 3 years ago. She says that her parents forced her to speak until she was 16 years old, when she went to learn LSCh in a school in Valparaiso for the Deaf, where she finished her fourth year of high school. She is currently studying to be a Special Education Technician.

2.2 Instrument

Data collection focused on corpus in LSCh generated through elicitation based on the delivery of the written story “The Greedy Squirrel”. The steps followed were (a) explanation of the research and its objectives along with the signing of a participation consent form with the support of an LSCh interpreter from the same school; (b) in-person delivery of the mentioned story text included a 2-week period for participants to read and review, during which the LSCh interpreter from the school examined the vocabulary of the text and to ensure accurate translation. This process emulated the usual dynamics of work organization for the class; (c) individual presentation of the narration in LSCh by each participant ensuring that there was no interference in the discursive narratives during the recording of the translation.

We opted to utilize the narrative The Greedy Squirrel, featured in the Narrative Discourse Comprehension Assessment (EDNA), implemented in educational settings across Chile (Pavez et al., 2008), due to its alignment with the following criteria: (a) it is a widely recognized and accessible tale for hearing Chilean children; (b) it exhibits a lucid narrative structure, incorporating components such as introduction, development, and conclusion, rendering it suitable for translation in sign language. Having a clearly defined narrative organization, the story aids translators in preserving the cohesion of the original message and ensuring a smooth reading experience for users of LSCh; (c) It holds relevance for hearing Chilean students at large, with potential translation to the Chilean Deaf community, due to its ability to convey universal lessons, cultural values, or simply entertain; (d) It show cases adaptability thanks to its clear narrative structure and potentially universal themes.

Consequently, the widespread appeal of the story, and its transparent narrative structure, pertinence, and adaptability within Chilean educational contexts served as pivotal factors in its inclusion within the study. Additionally, a text in written Spanish is used for the research because it is part of the daily life of the co-teachers since they do not have adapted materials to conduct their activities. Thus, every day that they need to support the students' learning processes, they must translate the academic texts available in written Spanish, and this story which is used to assess reading and writing skills of hearing students is representative as it is widely used by teachers in the school context.

The Children's story was written by the Argentine author Héctor Germán Oesterheld in 1962 under the pseudonym Inés and published by Editorial Sigmar, in Buenos Aires—Argentina It belonged to the series of stories known as Colección Mis Animalitos with the original title of Rolita, la ardillita glotona (Rolita, the greedy squirrel). Given the author's historical context, the story can be interpreted as a subtle criticism of capitalism. The widespread dissemination and utilization of the Argentine children's story The Greedy Squirrel in Chile is the result of a combination of cultural affinities between the countries, the recognized quality of Argentine children's literature, as well as editorial and commercial strategies that have enabled Argentine authors to establish a presence in the Chilean literary market.

2.3 Data collection and analysis procedure

The recording of the corpus was conducted in the television studio of the University of Antofagasta, using three video cameras on tripod, at three meters from the co-teachers: one full body frontal and two half body lateral cameras for focus; black backdrop in the background and with the support of two professional technicians. Prior to recording the corpus, image and lighting tests were conducted, along with rehearsals of different shot formats, to determine the time required for preparation and recording per person. One of the researchers behind the recording console gave advice to the co-teachers on where to position themselves and start the recording, since she had a basic command of the LSCh; she also gave avisad to the camera operators on how to approach the co-teachers while they were translating the story into the LSCh.

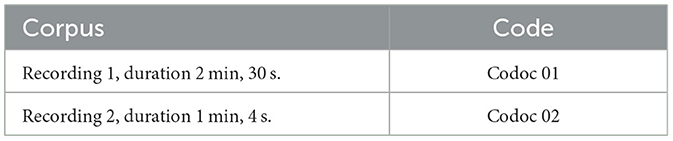

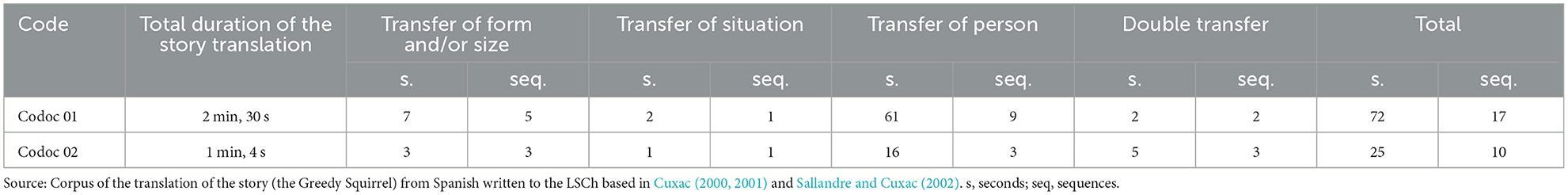

Visual data was collected on a single recording day in the studio. Two recordings of the linguistic corpus were obtained from Deaf co-teachers, each of them was assigned with a code for subsequent analysis, as described in Table 1.

The analysis was conducted in the following steps: (a) preliminary viewing of the complete videos to get a general idea of the content and structure of the translation made by the co-teachers of the written text; (b) breakdown of the content, first segmenting the video into manageable segments that referred to significant ideas or scenes of the story where there was a noticeable change in the action; (c) transcription in gloss of the sequences of signs used in each segment, with the translation into Spanish and then identification of the narrative structure made by each of the co-teachers; (d) comparative analysis of each co-teacher in relation to the structure of the base story in written Spanish, then between co-teachers, and subsequently the identification of transfer operations was made and classified by each co-teacher and compared. For this analysis, manual annotations were made on the gloss of the corpus. Due to technical limitations, software-assisted annotation was not used.

The LSCh gloss transcription was done by the author Pamela Lattapiat Navarro, who has a background in LSCh linguistics, and it was reviewed by the second author, who has a background in speech therapy, deaf interculturality and LSCh. Conventions used in the transcription of the LSCh gloss of the translation of the story are the following: (capital letters) = standard signs; (lowercase between quotes) = description or meaning of the signed expression; (2 m) = Use of two hands;(MD) = dominant hand;(mnd) = non-dominant hand; (izq) = left; (der) = right; (mov) = movement; (izq-der) = from left to right; (+) = number of repetitions of the sign; (00:00) = time; (prof) = proform1 (handshape); (1) = handshape in 1; (C) = handshape in C; (TP) = transfer of person; (TFS) = transfer of form and/or size; (TS) = transfer of situation and (DT) = double transfer.

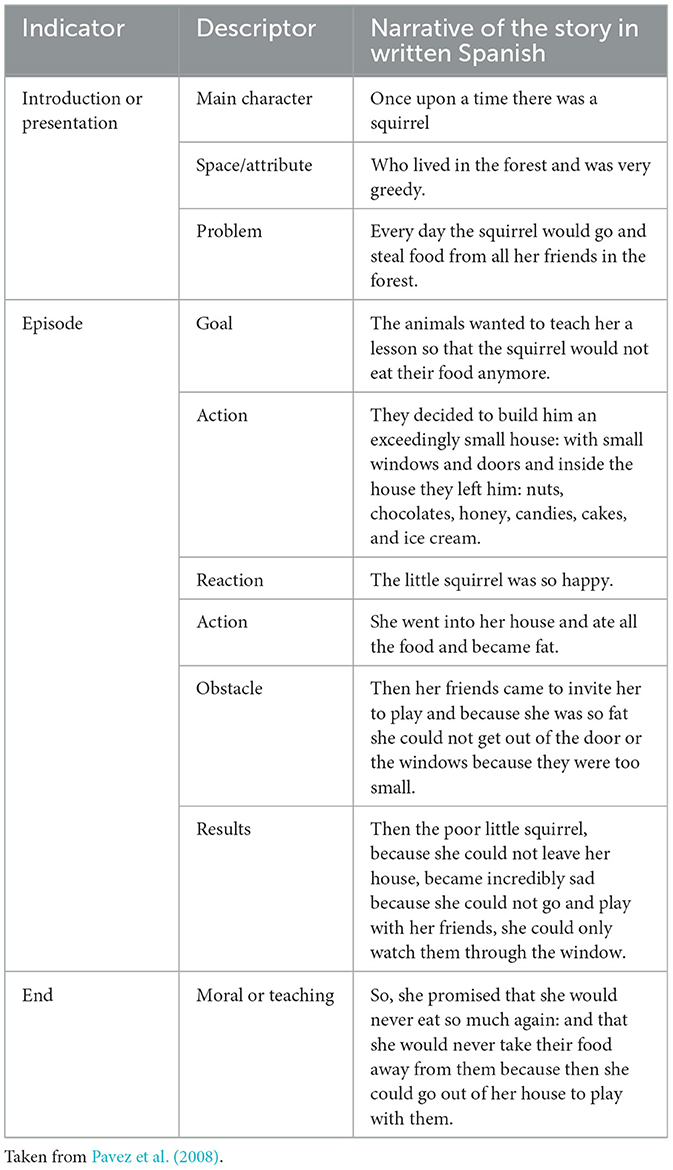

The recordings in LSCh were transcribed using glosses to identify the parts of the narrative structure of retellings (narrative schema) and later translated into Spanish. The content of the stories in LSCh was then analyzed in comparison with the source text, following the guidelines proposed by Pavez et al. (2008), regarding the presentation indicator and its descriptors of the main character, space, and attribute; the episode indicator and its descriptors of purpose, action, reaction, action, obstacle, and results; and the final indicator with the descriptor of moral or lesson. These guidelines are detailed in Table 2, which outlines the criteria used to analyze the translation of the children's story from written Spanish to sign language.

In a second stage, transfer operations were identified and classified according to Cuxac (2000) and Sallandre and Cuxac (2002) description transfer of form and/or size, transfer of situation, transfer of person and double transfer. The HIS were analyzed, identifying their occurrence and duration, as well as the use given in the translation of the story in LSCh.

In the gloss transcription, the transfer operations for each co-teacher were annotated with the abbreviations TF, TS, TP, and DT, as observed in each example presented in the results. For each transfer operation, the start and end times of the signed utterance sequence were marked to determine the total time spent on each type of transfer operation.

The series of time intervals taken to perform an utterance per transfer operation was termed a sequence. Each sequence contains a structure of manual and non-manual expressions that can collectively be identified as a type of transfer operation. It is essential to understand that the sign itself does not indicate the type of transfer; rather, it is the combination of linguistic elements articulated by the signer that indicates the type of transfer operation used.

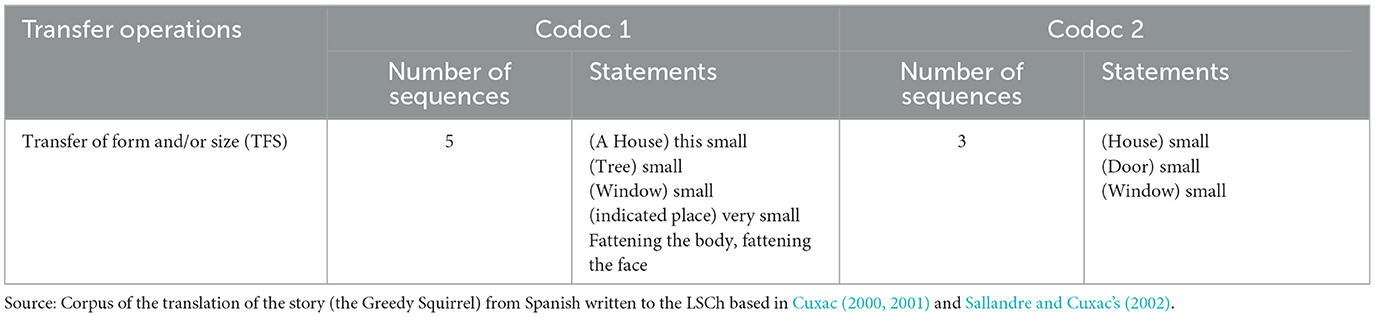

A description of the transfer operations for analysis was provided. In Table 3, an example extract is presented to describe the transfer operation of form and/or size for each co-teacher. Determining the number of sequences and their duration was deemed important to visualize how these operations occur and their significance in the co-teachers' translation of the story. Table 4 presents the corresponding analysis of the categories and subcategories of the narrative structure for each co-teacher. In Table 5, of the results section, the total time in seconds for each type of transfer operation is shown, along with the corresponding number of sequences each participant expressed in the translation of the story.

3 Results

The results are presented in two parts: the first part corresponds to the narrative structure resultant in translation of the participants based on the qualitative differences in content among them (Pavez et al., 2008). Secondly, the transfer operations of highly iconic structures used are identified (Cuxac, 2000, 2001; Sallandre and Cuxac, 2002), showing differences and similarities of use between the participants for the translation of the story.

3.1 Narrative structure in co-teachers

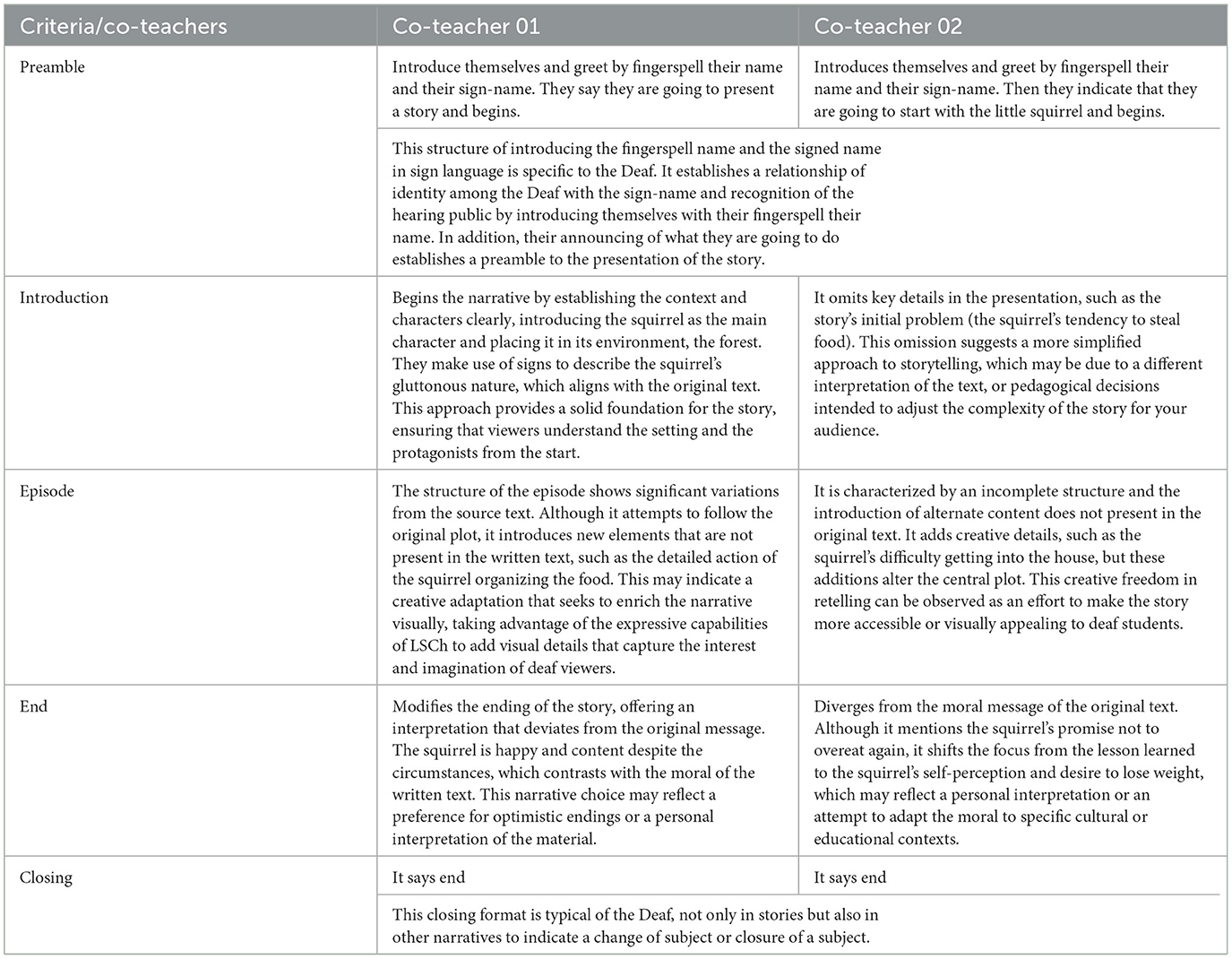

Before starting the story, the co-teachers introduce themselves and greet by fingerspell their name and their sign-name. One of them states that she will tell a story.

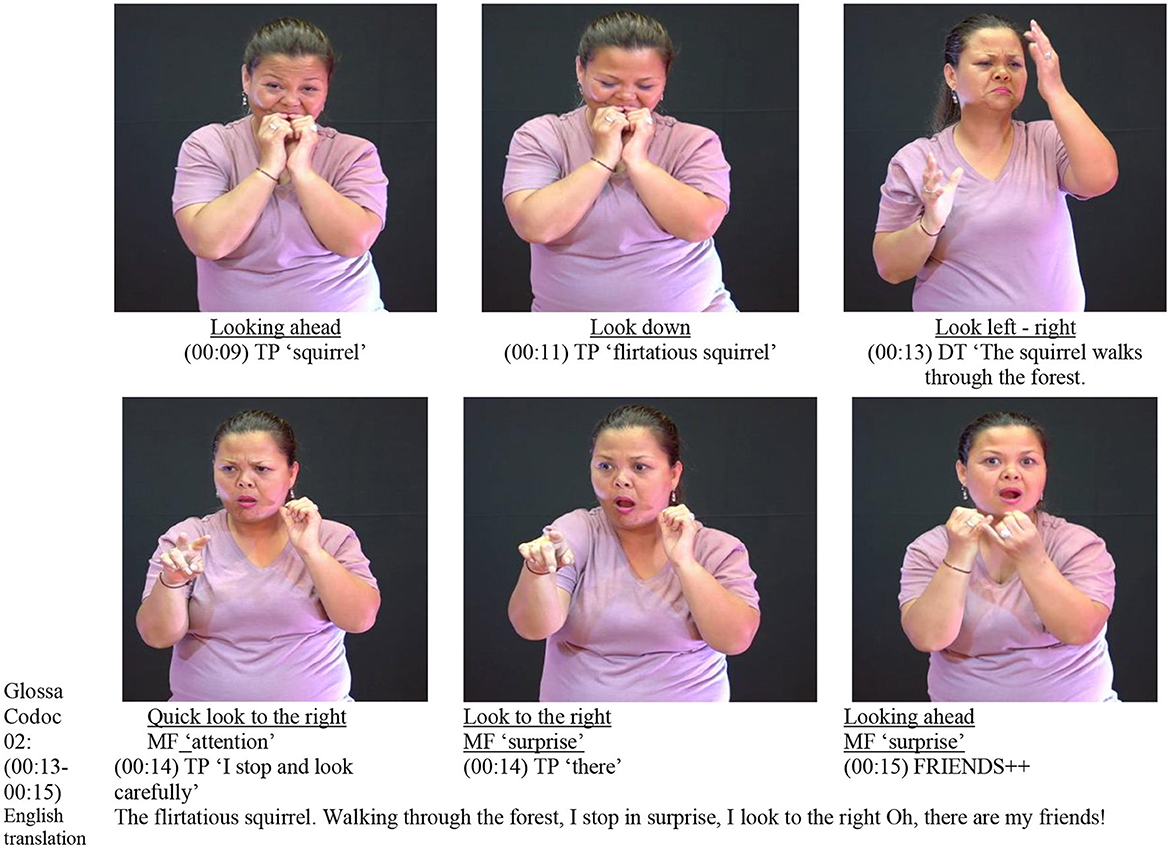

Regarding the narrative structure, co-teacher 01 provides a complete introduction or presentation of the story: she shows the character, the setting, the attribute and the initial problem or event, unlike co-teacher 02, who does not refer to the initial problem or event. This latter narrator introduces the main character, adding the attribute of being flirtatious, placing it walking through the forest. What stands out in her narrative is that there is no problem; she never mentions that the little squirrel stole from her friends as in the original story.

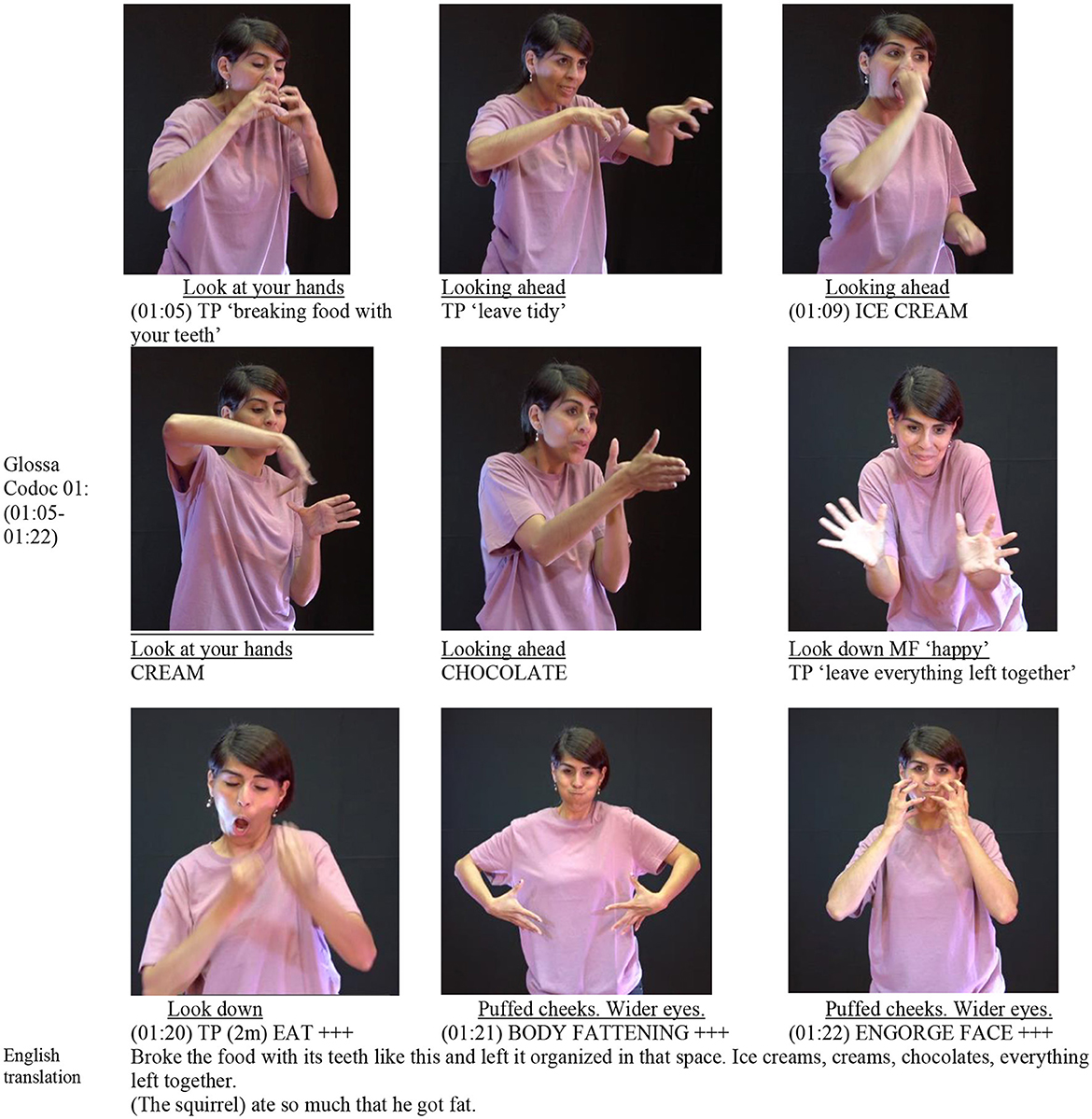

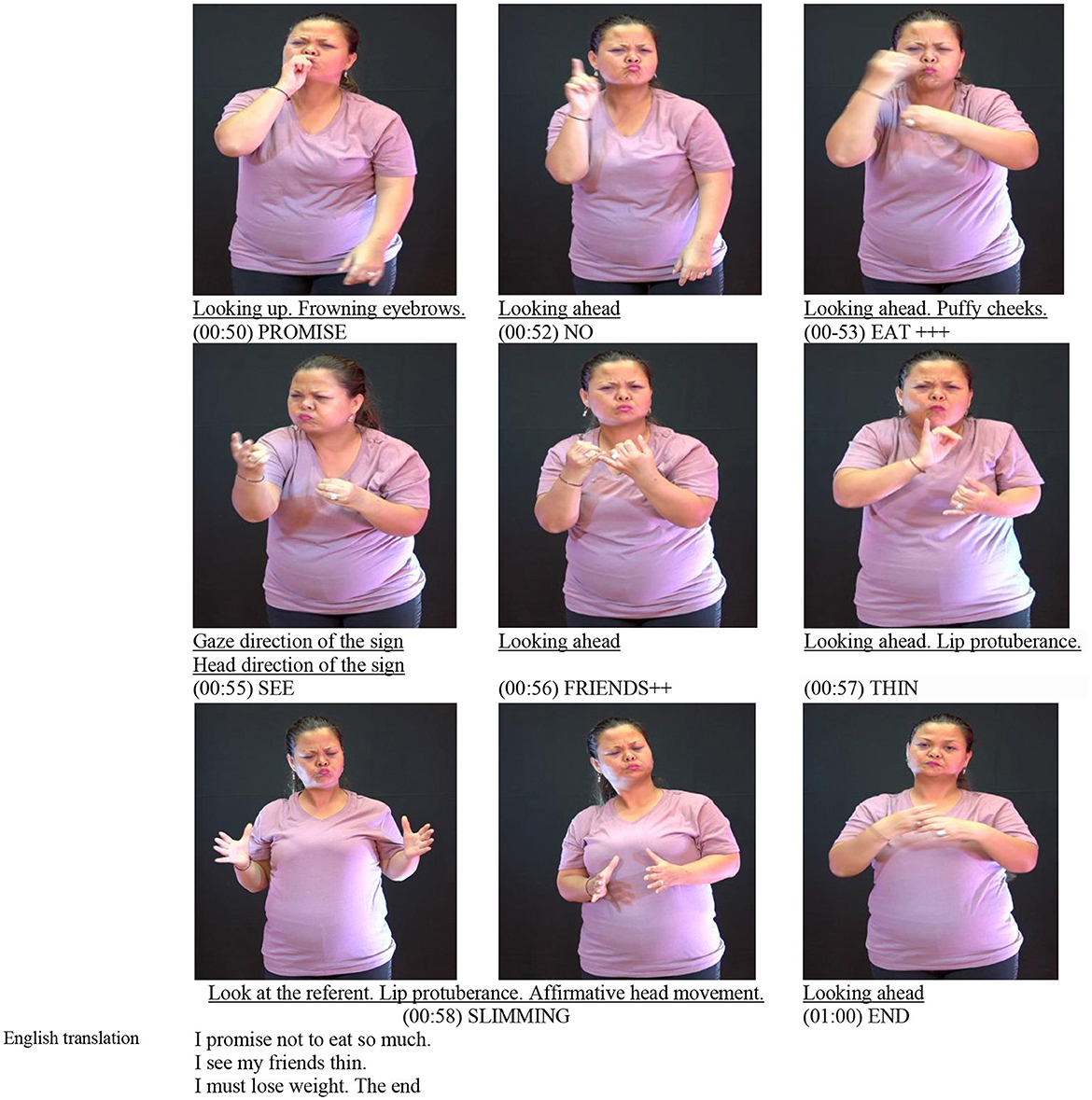

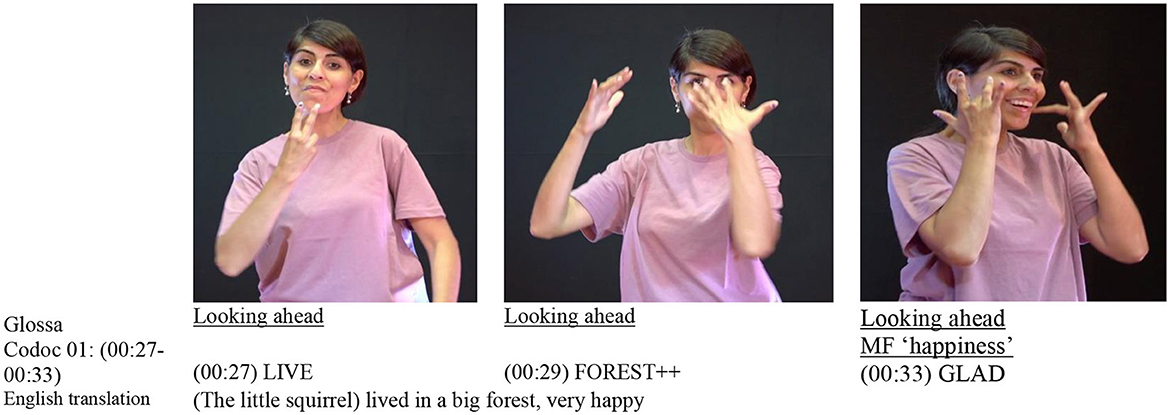

Regarding the episode, in both co-teachers, it is shown to be incomplete. Neither of them expresses the goal of the narration. In this sense, in co-teacher 01, the episode consists of a creative action, a reaction, an obstacle, and a result. See images sequence of Figure 1.

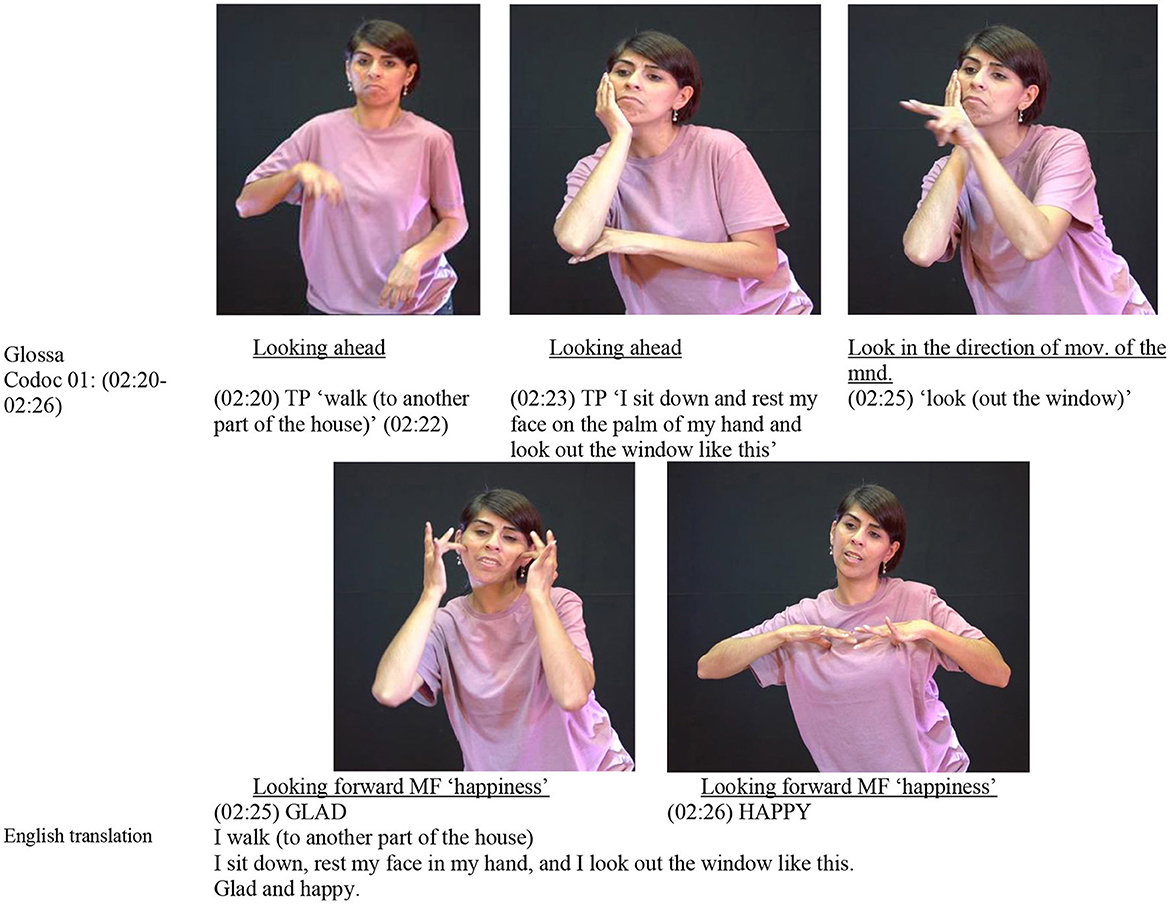

In the obstacle, co-teacher 01 recounts that her friends went to look for her, and that, due to her fatness, she had difficulty getting out through the window and the door, which aligns with the source text. The result in her narrative structure corresponds to the source text by stating that the little squirrel stays bored, swears not to eat again, is upset about her condition, insists that she needs to lose weight, and watches her friends play through the window. She is sad and remorseful about her fatness. However, she changes the ending in relation to the source text, contradicting the result, by ending happily looking at her friends through the window. See image sequence Figure 2.

In this translation, even though co-teacher 01 expresses the problem of theft, she does not explain how it is solved. What is reflected in her narration is the problem of eating too much, gaining weight, and not being able to leave her house to play with her friends, and because of this, she swears not to eat that much again, changing the sense of the original text, which does have a moral or lesson.

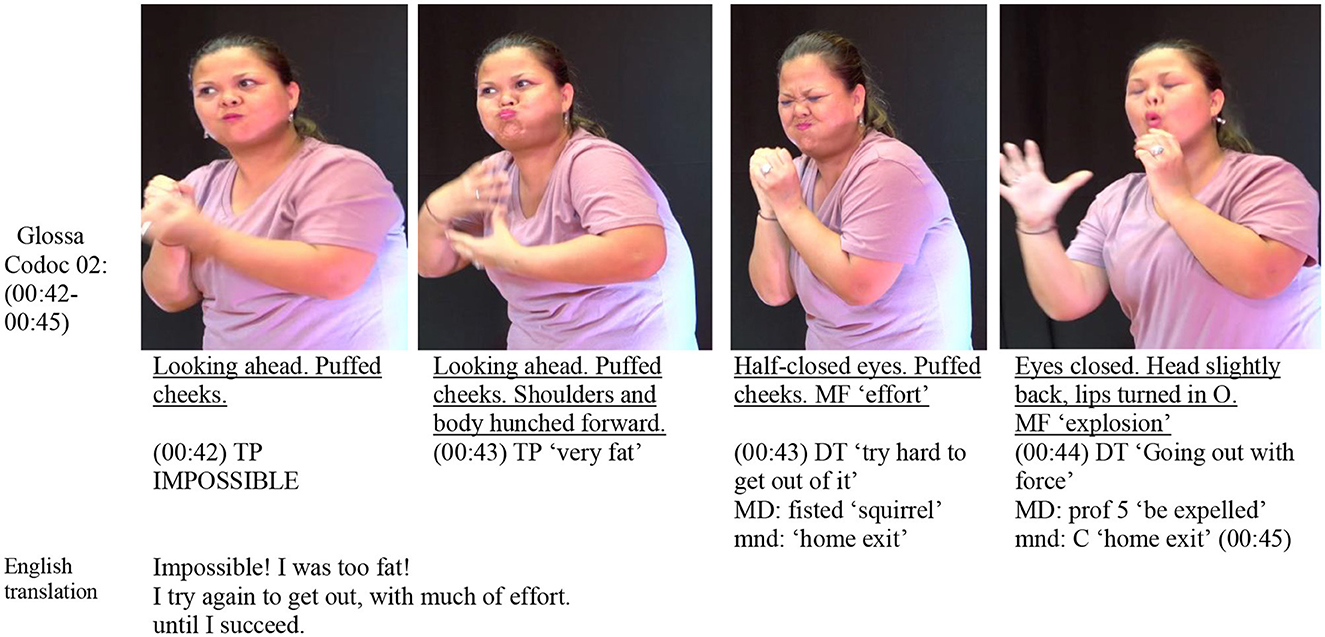

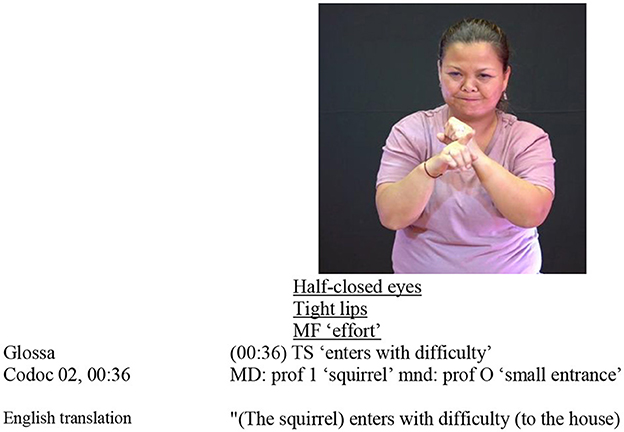

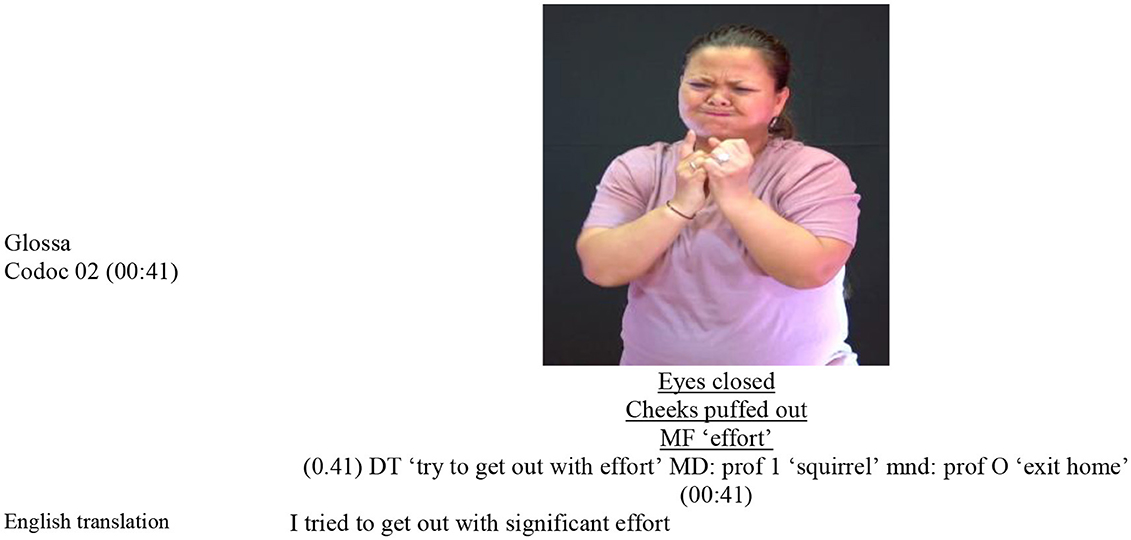

In the case of co-teacher 02, the episode is presented incomplete since she does not express a goal, altering the sense of the story. The co-teacher refers to the construction of a small house in a small tree, with a small door and small window, continuing the description of what was in that place, ice cream, candy, and different foods. Then the little squirrel comes in with difficulty and eats much. Friends were playing all over the place. Then he tries to get out with significant effort (see Figure 3).

The result is also different from the source text because in the original text, the little squirrel cannot get out of the house. Additionally, the ending has been altered. Although there is a promise not to eat in enormous quantities, as in the original text, this promise does not have the same reasons as the original story (see Figure 4).

Both narrators announce the end of their narration with the expression “END” at the end of the story. In neither of the two Deaf narrators is the moral of the story observed. Although a structure can be seen that does not have all the parts of the original story, regardless of adding other elements, the meaning of the story changes in relation to the original.

The main finding of the story translation in terms of narrative structure is related to the ability of the co-teachers to recursively adapt the original story to make it more visual, accessible, and attractive to the audience of Deaf students, who were the potential audience, according to their understanding of a second language, i.e., written Spanish. The following table summarizes and compares elements of the narrative structure resulting from the translation of the story among the co-teachers (see Table 4).

Recursive adaptation manifests in various aspects of the translation, from the preamble and introduction, where both co-teachers establish a personal and cultural connection with their audience using hand spelling and their sign-names, to the introduction of the story, where variability in the narrative approach used in the translation is evident. Neither of the two co-teachers alludes to the goal of the source text and the endings are also different. One of them comes closer to the original text in its translation, while the other opts for a simplification that omits key details, reflecting an effort to adjust the complexity of the narrative to the possible needs and preferences of the deaf audience or their possible limited understanding of the text in a second language.

In the development and conclusion of the narrative, the differences in structure and moral message between the co-teachers apparently highlight an intentional adaptation that takes advantage of the expressive capabilities of LSCh to present elements of the story, such as the size of the house, which may contribute to capturing the interest of deaf viewers.

3.2 Transfer operations

Within the Highly Iconic Structures (HIS), the co-teachers exhibit a diverse range of transfer operations. Initially, the duration of each type of transfer operation performed by each co-teacher was identified and subsequently presented in Table 5.

Table 5 displays the duration of transfer operations, including transfer of form and/or size, transfer of situation, transfer of person, and double transfer. Co-teacher 01, for instance, dedicates a massive portion of the translation time to the transfer of person, accounting for almost 40.6% of the total translation time and 84.7% of the total time allocated to transfer operations (72 s). On the other hand, Co-teacher 02 allocates a total percentage of 39% to transfer operations in relation to the total translation time, a percentage similar to Co-teacher 01.

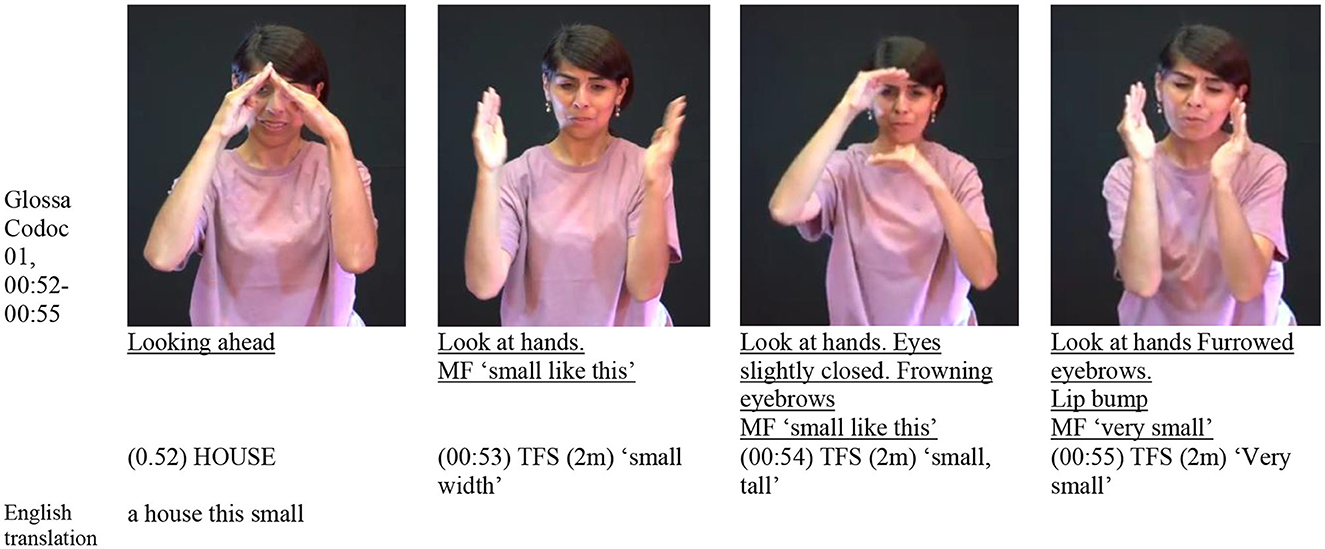

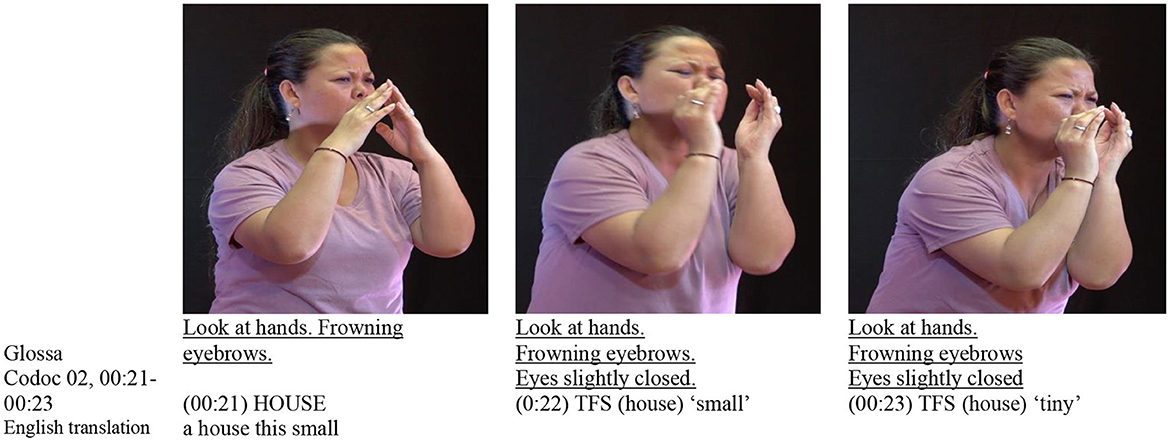

However, Co-teacher 02 exhibits a greater use of double transfer compared to Co-teacher 01, which involves combining situational and personal transfer. In co-teacher 01, the use of transfer operations of form and size is evident when the narrator describes the shape of the house, the tree, and the windows. It also appears when expressing the shapes of the body and face of the squirrel when she gains weight (see Table 2; Figure 5).

Co-teacher 01 and 02 coincide in the use of transfer of form and/or size when describing the small house. The use of the sign to describe small objects by co-teacher 01 shows the shape and size of those objects that are referred, while co-teacher 02 does it with an adaptation of the object sign in relation to its size. Both co-teachers' facial and body expressions are relevant to accompany the meaning of the sign they express of “small”, highlighting the slightly closed eyes, furrowed eyebrows, and lip protrusion in both narrators, with co-teacher 02 adding the gathering of her shoulders and bringing her hands close to her face (see Table 2; Figure 6).

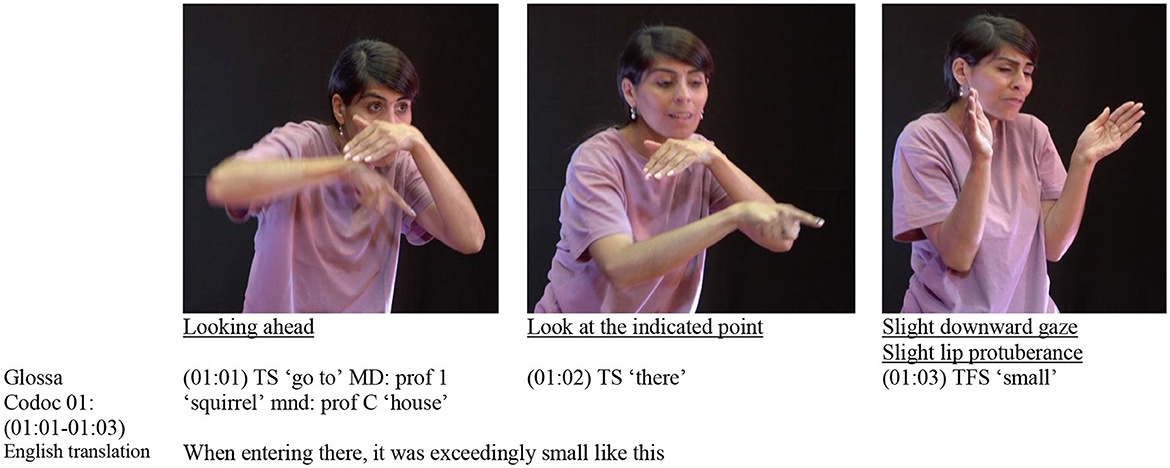

Regarding transfer of situation, the narrators coincide in the episode when the squirrel enters the house (see Figures 7, 8).

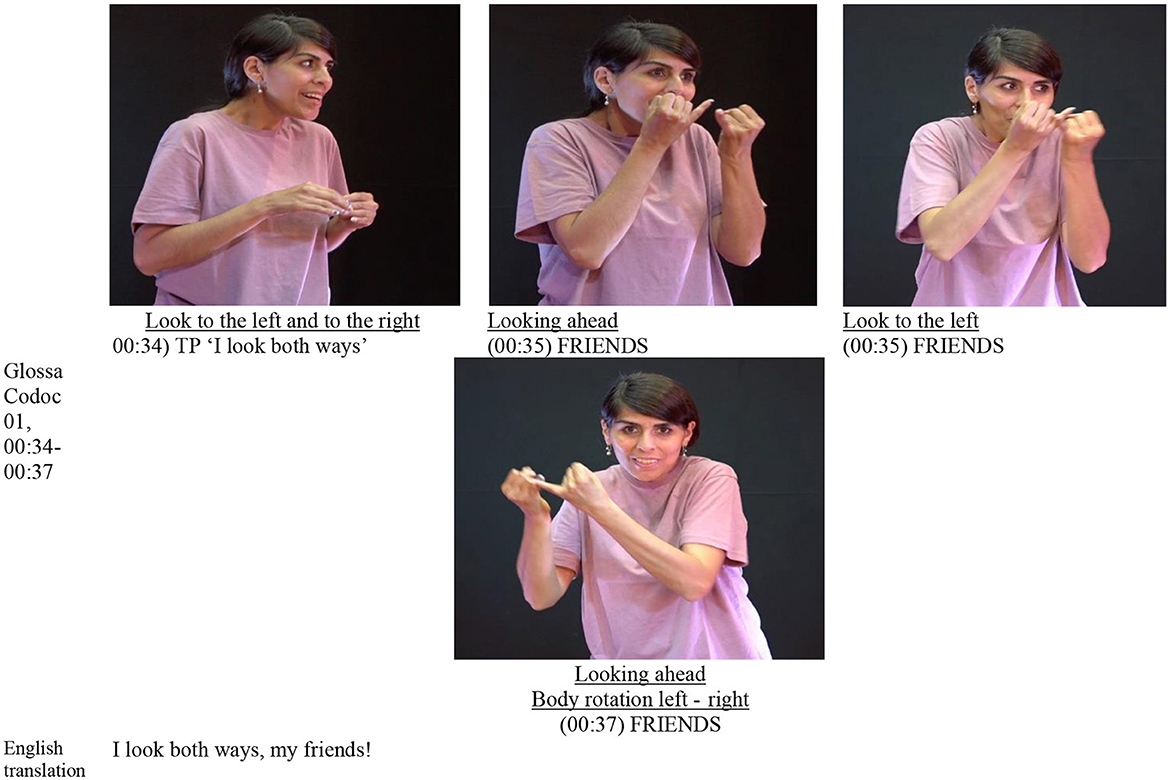

For both co-teachers, the dominant hand indicates the actant and the non-dominant hand represents the space where they enter. For co-teacher 01, the importance lies in the squirrel's entry into a small space in the house, denoting it not only with the sign “Small” at the end but also at the beginning, when she points out how she enters the house, she lowers her head. For co-teacher 02, this part of the narrative focuses on the difficulty of entering the house, demonstrating it with the handshape of her non-dominant hand, the fingers are more closed, and her facial expression denotes “effort”. The co-teachers also coincide in the use of transfer of personal in the presentation., although with variations in content (see Figures 9–11).

Co-teacher 01 begins by telling where the little squirrel lived and in what emotional state it was in with standard signs (Figure 9. Subsequently, she takes on the role of the character (Figure 10), where the gaze, facial and body expression become relevant in personifying the squirrel. The narrator's body and head turn to the left, it is here where the transfer of personal begins to manifest.

It is important to note that the narrator's gaze is not on the interlocutor but in the space where they have placed the different referents. The narrator becomes the character in the story, narrating in the first person.

The translation of the sequence of photos of Figure 11 of the LSCh gloss to Spanish was complex, because the looks and the body indicate when the transfer of person begins, however the narrator looks at the camera, she does not have a turn of body or head that indicates the beginning of the transfer operation. That is, it is subtle and what the co-teacher does is that her shoulders and arms draw together, giving the meaning, in addition, of “flirtatious,” coupled with the way she moves her hips that does not indicate just walking. Next, the gaze moves downward, which suggests that the transfer of person can begin with the gaze toward the interlocutor to indicate the character that enters the scene.

In the double transfer, the narrator uses transfer of person and transfer of situation. The co-teacher 02 use double transfer to express the squirrel's movement in the obstacle episode.

This narrator uses double transfer when expressing the small space to get out with her non-dominant hand and with her dominant hand to portray the character trying to get out, transfer of situation (Figure 12). Simultaneously, she uses a transfer of person representing the squirrel character with her body and facial expressions. These transfer operations provide details of the events. It is also possible to appreciate how referential elements are in space and how they reappear throughout the narration.

The deaf co-teachers, when translating the story from written Spanish to LSCh, not only used HIS with the transfer operations of shape and/or size, situation, person, or double transfer, but also made use of standard signs. In the examples presented, standard signs are identified for house, live, forest ice cream, cream, chocolate, glad, happy, impossible, promise, no, eat, see, friends, thin, slimming, end, among others, and which in the gloss transcription are presented in capital letters. Also, they fingerspell their name and their sign-name.

4 Discussion

The results of this study provide an example and its insight into the translations in Chilean Sign Language (LSCh) of the story The Greedy Squirrel. Firstly, the presence and cohesive function of transfer operations, classified according to Cuxac's (2000); Cuxac (2001) and Sallandre and Cuxac's (2002) functional regrouping for FSL, is employed in the translation of a story from written Spanish into LSCh. This observation emphasizes the importance and utility of these transfer operations in sign language that are utilized in translation, supporting their relevance in sign language and the need for their application to translations to make narratives relevant to the Deaf.

The consistent use of transfer by the narrators, as discussed in the results, corresponds to Cuxac's (2000) findings on gaze direction in sign language narratives. By directing their gaze toward created spatial elements and embodying both character and narrator roles, the co-teachers effectively engage in storytelling. This echoes Cuxac's emphasis on gaze direction for conveying meaning and enhancing audience comprehension. Highly Iconic Structures enrich the storytelling experience and showcase the co-teachers' nuanced grasp of sign language storytelling norms, bolstering the effectiveness of their translation.

The analysis of the use of transfer operations reveals that approximately one third of the translation is composed of Highly Iconic Structures (HIS). Without a comparison to other types of discourse, it is difficult to ascertain whether this proportion of HIS is substantial. It is possible that the utilization of HIS is related to the narrative structure of children's stories, aimed at creating an impactful experience for the young audience, or to the textual typology that influences how information is presented. This uncertainty underscores the necessity of conducting research with natural corpora in Chilean Sign Language (LSCh) and translations from written Spanish performed by Deaf individuals. Such studies would facilitate a more accurate assessment of the LSCh translation competence of Deaf co-teachers, considering the discursive form and function of these transfer operations. This could lead to a deeper understanding of their role in translating academic texts that they routinely manage in educational settings.

Although the results suggest an incomplete narrative structure in stories translated by Deaf individuals relative to the original text, it is crucial to emphasize that Deaf co-teachers incorporate specific visuo-gestural elements that enrich the narrative and enhance comprehension. These elements not only preserve a temporal sequence of events but also integrate intensified visual and gestural components that augment the narrative and bolster the cohesion and coherence of discourse in Chilean Sign Language, thereby offering an immersive narrative experience.

These findings underscore the need for further attention and research to understand how Deaf individuals translate stories from written Spanish, particularly focusing on the methods and reasons behind their reorganization of narrative structures. This research is essential to supplement or complement written Spanish narratives with images, or to rearrange them into different narrative structures of Spanish, thereby facilitating access for Deaf audiences.

The results illuminate the complexity of narrative translations within Deaf contexts and emphasize the necessity of future research focused on the unique elements Deaf individuals incorporate into translations. These elements reflect the language, thought, and visuo-gestural structure intrinsic to Deaf culture. Such research is crucial to promoting equitable access to narratives and, importantly, to advancing the production of narratives by and for the Deaf community, thus reducing their reliance on narratives from the hearing community for educational development.

Divergences among the narrators are evident, both in content and expression. These differences may reflect diverse narrative styles, but they also suggest a different linguistic command and comprehension among the narrators of the Spanish base text written for translation into LSCh without picture support, as they sought to replicate the everyday situation of the school context they face. This aspect highlights the need to consider linguistic variability, comprehension and the use of visual aids when translating and analyzing LSCh narratives.

5 Conclusion

The results illustrate differences in narrative structure and transfer operations employed by Deaf co-teachers when translating stories. These variations may impact narrative cohesion and the comprehension of the original message within the text. This highlights the significance of assessing proficiency in written Spanish during translation and storytelling in LSCh. It prompts valuable inquiries into how such distinctions might influence narrative comprehension and their potential effects on intercultural teaching for Deaf students.

The co-teachers use these transfer operations to represent both the setting and the actions of the characters in the story. These transfer operations serve to enhance the narrative and provide visual details of the events described. The transfer operations enrich the translation by providing visual details and enhancing comprehension. It is also necessary to understand that these Highly Iconic Structures have rules of production in LSCh discourses, where the gaze becomes a highly significant element, guiding and clarifying the diverse types of Transfers. It is also necessary to focus on the movements of the body, head and facial expressions that play a determining role in the discursive cohesion of the texts.

The identification of partial narrative structures highlights the need to develop specific educational materials and adapted strategies to improve the comprehension of narrative texts. It also highlights the importance of collaborative work between Deaf individuals, interpreters, and educational professionals, emphasizing the need for educational institutions to facilitate this collaboration and promote an interdisciplinary approach in Deaf education. In this context, it is crucial that the time allocated for the preparation of educational materials in LSCh be more extensive and better planned, allowing for a more effective and appropriate development of these resources.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Comité de Ética del Proyecto de Investigación Científica bajo el expediente 376/2022. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

GM: Writing – review & editing. PL: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was financially supported by a FONDECYT for Research Initiation Grant #11230383/2024, Virtual Communication and Language Laboratory, University of Antofagasta, Chile.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the Deaf Community and Chilean Sign Language interpreters for their participation in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Linguistic element with anaphoric or cataphoric function, which serves to provide cohesion to the text and reduce redundancy, while still indicating what or who is being talked about (Centro Virtual Cervantes, 1997–2024).

References

Acuña Robertson, X., Adamo Quintela, D., Cabrera Ramírez, I., and Lissi, M. R. (2012). Descriptive study of the development of narrative competence in Chilean Sign Language. Onomázein 26, 193–219. doi: 10.7764/onomazein.26.07

Ahlgren, I., and Bergman, B. (1993). Preliminary considerations of narrative discourse in Swedish Sign Language. Signo y Seña (Special Issue: Visual Speech. Linguistics of Sign Languages), 61–71. Available at: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6914121 (accessed October 9, 2023).

Bras, G. (2002). Descripteurs, classificateurs et morphosyntaxe en Langue des signes française (LSF). Revue Linguistique didactique langues 26, 63–80. doi: 10.3406/lidil.2002.1825

Centro Virtual Cervantes (1997–2024). Tácticas y Estrategias pragmáticas. Glosario de términos. Available at: https://cvc.cervantes.es/Ensenanza/Biblioteca_Ele/plan_curricular/niveles/06_tacticas_pragmaticas_glosario.htm (accessed May 16, 2024).

Cheng, Q., Roth, A., Halgren, E., and Mayberry, R. I. (2019). Effects of early language deprivation on brain connectivity: language pathways in deaf native and late first-language learners of american sign language. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 13, 13–320. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2019.00320

Cuxac, C. (2000). La Langue des Signes Française (LSF): les voies de l'iconicité, Bibliothèque de Faits de Langues (Evry), (15–16). Paris: Ophrys, 391.

Cuxac, C. (2001). Les langues des signes: analyseurs de la faculté de langage. Acquisition et interaction en langue étrangère. 15, 11–36. doi: 10.4000/aile.536

Eichbaum, Q., Barbeau-Meunier, C. A., White, M., Ravi, R., Grant, E., Riess, H., et al. (2023). Empathy across cultures - one size does not fit all: from the ego-logical to the eco-logical of relational empathy. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 28, 643–657. doi: 10.1007/s10459-022-10158-y

Hall, M. L., Eigsti, I. M., Bortfeld, H., and Lillo-Martin, D. (2017). Auditory deprivation does not impair executive function, but language deprivation might: evidence from a parent-report measure in deaf native signing children. J. Deaf Stud. Deaf Educ. 22, 9–21. doi: 10.1093/deafed/enw054

Hall, W. C. (2017). What you don't know can hurt you: the risk of language deprivation by impairing sign language development in deaf children. Matern Child Health 21, 961–965. doi: 10.1007/s10995-017-2287-y

Halliday, M. A. K., and Hasan, R. (1989). Language, Context, and Text: Aspects of Language in a Social-Semiotic Perspective, 2nd Edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Humphries, T., and Allen, B. (2008). Reorganizing teacher preparation in deaf education. Sign Lang. Stud. 8, 160–180. doi: 10.1353/sls.2008.0000

Humphries, T., Kushalnagar, P., Mathur, G., Napoli, D., Padden, C., Rathmann, C., et al. (2012). Language acquisition for deaf children: reducing the harms of zero tolerance to the use of alternative approaches. Harm Reduct. 9:16. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-9-16

Livingston, S. (1997). Re-thinking the Education of Deaf Students: Theory and Practice from a Teacher's Perspective. Michigan: University of Michigan.

Martínez, R., and Astrada, L. (2010). “Narrative discourse in Argentine Sign Language (LSA): analysis of a life story,” in IV International Congress Cultural Transformations: Debates of Theory, Criticism, and Linguistics in the Bicentennial, Buenos Aires. Available at: https://www.conicet.gov.ar/new_scp/detalle.php?keywords=&id=38242&congresos=yes (accessed October 11, 2023).

Massone, M. I., and Machado, E. M. (1994). Argentine Sign Language. Analysis and Bilingual Vocabulary. Buenos Aires: Edicial.

Ministry of Education of Chile (2009). Supreme Decree 170 Norms to Determine Students WITH Special Educational Needs Who Will Benefit From Special Education Grants. Available at: https://bibliotecadigital.mineduc.cl/handle/20.500.12365/17433?show=full (accessed October 13, 2023).

Ministry of Education of Chile (2013). Technical Guidelines for School Integration Programs (PIE). Santiago: MINEDUC. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12365/2077 (accessed October 15, 2023).

Ministry of Education of Chile (2017). Curricular Videos in Chilean Sign Language (LSCh). Available at: https://rural.mineduc.cl/videos-curriculares/ (accessed May 16, 2024).

Ministry of Education of Chile (2024). RED with Chilean Sign Language. Available at: https://especial.mineduc.cl/recursos-apoyo-al-aprendizaje/recursos-educactivos-digitales/ (accessed September 14, 2024).

Morales López, E., Mallo García, B., and Bobillo García, N. (2019). Cohesion and coherence mechanisms in the organization of a narrative in sign language. J. Sign Lang. Stud. 1, 91–125. Available at: https://revles.es/index.php/revles/article/view/21/41

Morales-Acosta, G. (2019). Perceptions about Chilean Sign Language in the education of Deaf students: teacher and co-teacher as historically situated communicative subjects in the classroom. Education 43, 65–83. doi: 10.15517/revedu.v43i2.31169

Morales-Acosta, G., Lenis, M., and Aguilar, A. (2020). “Post-agreement and Deaf Diversity: towards narratives of conflict in Colombian Sign Language (LSC),” in Inclusion of Cultural and Social Diversity in Education [Center for Latin American Studies of Inclusive Education (CELEI)], 129–145. Available at: https://celei.cl (accessed October 19, 2023).

National System of Labor Skills Commission (2018). Profile Deaf Co-Educator in Chilean Sign Language and Deaf Culture. Available at: https://certificacion.chilevalora.cl/ChileValora-publica/home.html (accessed May 3, 2024).

Otárola, F., and Crespo, N. (2016). Characteristics of narrative structures in personal experience stories of bilingual Deaf students in Chilean Sign Language. Lang. Speech 20, 47–71. Available at: https://www.redalyc.org/journal/5119/511954843004/html/

Pavez, M., Coloma, C., and Maggiolo, M. (2008). Narrative Development in Children: A Practical Proposal for Assessment and Intervention in Children With Language Disorders. Barcelona: Ars Médica.

Pérez Aguado, N., and Fernández-Viader, M. (2018). “The importance of the Deaf teacher in the teaching-learning processes of written language with Deaf students,” in Proceedings of the CNLSE Congress on Spanish Sign Language: Madrid, October 26-27, 2017, 24–41. Available at: https://www.siis.net/documentos/ficha/539016.pdf (accessed October 11, 2023).

Pérez, Y. (2006). Manual markers in narrative discourse in Venezuelan Sign Language. Letters 48, 349–363. Available at: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/ejemplar/156889

Prinz, P. M., and Strong, M. (1998). ASL proficiency and English literacy within a bilingual deaf education model of instruction. Top. Lang. Disord. 18, 47–60. doi: 10.1097/00011363-199808000-00006

Reiß, K., and Vermeer, H. (2015). “The priority of purpose (skopos theory),” in Towards a General Theory of Translational Action: Skopos Theory Explained (London: Routledge), 85–93.

Reyes, J. (2019). Visuo-Gestural Configurations for Naming and Configuring Physical Terms in Sign Language: a Comparative Study (Bachelor's Thesis in Physics). National Pedagogical University. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12209/10512 (accessed October 27, 2023).

Rodríguez, F. (2014). Co-teaching, a strategy for educational improvement and inclusion. Latin Am. J. Incl. Educ. 8, 219–233. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12365/18059

Sallandre, M.-A., and Cuxac, C. (2002). “Iconicity in sign language: a theoretical and methodological point of view,” in Gesture and Sign Language in Human-Computer Interaction. GW 2001. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 2298, eds. I. Wachsmuth, and T. Sowa (Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer), 173–180.

Ustrell-Ibarz, M. (2015). Co-teaching as an Inclusion Tool (bachelor's thesis). International University of La Rioja. Available at: https://acortar.link/8ER7jc (accessed November 13, 2023).

Valenzuela López, N. (2024). Stories for Everyone. Available at: https://www.historiasparatodos.cl/videoteca.html.Instagram:~@historiastodos (accessed May 15, 2024).

Vite, I. M., and Fernández-Viader, M. P. (2017). Deafness and the fourth Sustainable Development Goal (SDG4): proposal for a RED project for bilingual education of the Deaf under the European framework. Reg. Cohes. 7, 19–39. doi: 10.3167/reco.2017.070104

Yasar-Akyar, O., Rosa-Feliz, C., Sunday-Oyelere, S., Muñoz, D., and Demirhan, G. (2022). Special Education Teacher's professional development through digital storytelling. Comunicar 71, 93–104 doi: 10.3916/C71-2022-07

Keywords: sign language, translation, structure narrative, transfer operations, deaf teachers

Citation: Morales Acosta GV and Lattapiat Navarro P (2024) Translation of a story into Chilean Sign Language: productions by deaf co-teachers. Front. Educ. 9:1368082. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1368082

Received: 09 January 2024; Accepted: 28 August 2024;

Published: 01 October 2024.

Edited by:

Jie Zhang, SUNY Brockport, United StatesReviewed by:

Cristina Gil, Instituto Politecnico de Setubal (IPS), PortugalRachel Sutton-Spence, Federal University of Santa Catarina, Brazil

Paulo Vaz De Carvalho, Catholic University of Portugal, Portugal

Copyright © 2024 Morales Acosta and Lattapiat Navarro. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gina Viviana Morales Acosta, Z2luYS5tb3JhbGVzQHVhbnRvZi5jbA==

Gina Viviana Morales Acosta

Gina Viviana Morales Acosta Pamela Lattapiat Navarro

Pamela Lattapiat Navarro