- 1Faculty of Sociology, VNU-Hanoi University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Hanoi, Vietnam

- 2Faculty of Psychology, VNU-Hanoi University of Social Sciences and Humanitiese, Hanoi, Vietnam

Taking that higher education is career-oriented, this study examines how Vietnamese undergraduate students engage with their study and how the factors related to the training program and occupation’s prospects contribute to students’ engagement with their study. The study applies a mixed-method approach. Self-administered questionnaire survey is used to collect data from 973 Vietnamese undergraduate students, of which 48.2% are social work students and 51.8% are non-social work students. In addition, the study conducts 27 semi-structured interviews with students and lecturers to explore their perspective and experiences with regard to students’ study engagement and the factors involved. The results show that social work students are more engaged with their study than non-social work students, even though they feel more worried about job opportunity and income. Approximately one-third of social work students consider not to pursue social work profession when they graduate mostly because they believe that working in social work cannot provide them the income they need for their living. However, the results also show that students’ satisfaction/dissatisfaction with income in their field was not statistically related to their study engagement. Instead, feeling of personal growth, opportunity to perform personal ability, sense of significance, convenient access to study materials and activities, and feeling proud of their school and lecturers’ prestige are found positively associated with students’ level of study engagement. The study hence provides some recommendations for educators to strengthen students’ study engagement at higher education level.

1 Introduction

Student’s study engagement is one of the key factors affecting the outcome quality in higher education (Hart et al., 2011; Boulton et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2019). Studies explain that when students are engaged with their study, they invest more time and energy in academic effort and professional and extracurricular activities in school, tend to develop coping mechanisms to help them maintain and self-regulate their own learning process, and thus increase the quality of their education outcomes. Research also shows that study engagement results in increasing satisfaction and self-confidence and reduces the risk of failures and dropouts. Importantly, study engagement is a multidimensional ability that can be trained, developed, and improved over time (Assunção et al., 2020). Therefore, creating a learning environment that promotes study engagement has been a concern in the higher education sector (Bowden et al., 2021).

However, studies also point out that promoting study engagement is increasingly a challenge for higher education sector. Nowadays, students tend to be less committed to their studies in all cognitive, emotional, and behavioral dimensions (Collaco, 2017). In this context, understanding students’ study engagement and identifying the factors related to study engagement is of great importance. Therefore, not only university lecturers and researchers but also policymakers are paying more and more attention to students’ study engagement as a key to solving problems, such as student’s poor academic performance, classroom boredom, and dropping out of school (Fredricks and McColskey, 2012). What is study engagement? Unfortunately, there is no consensus in conceptualizing study engagement. Along with the increasing interest of stakeholders (educators, researchers, and policymakers) in the issue of study engagement, study engagement has been explored under various conceptualizations and many different names, such as academic engagement, class engagement, or school engagement (Fredricks and McColskey, 2012). Even the concept of ‘engagement’ remains instinctive (Schaufeli, 2013).

The concept of ‘engagement’ originally, however, does not only come from educational studies but also from studies of occupation and employment. This concept has recently been adapted to the field of education (Assunção et al., 2020). Assunção et al. (2020) detect conceptualization and measures of “engagement” and find that it originates from the concept of “burnout,” which is introduced by Maslach and Leiter (1997). According to these two authors, whereas burnout is a concept that refers to the erosion of cohesion, engagement is observed as the opposite state of exhaustion and is defined with dimensions of (1) the feeling of energy, (2) commitment, and (3) fulfillment. When engagement wears off, energy drains, commitment turns to skepticism, and productivity becomes ineffective, burnout comes in. According to this perspective, employees are assessed on the burnout-engagement axis in relation to work. However, according to Assunção et al. (2020), this way of conceptualization has a shortcoming that some people are neither exhausted nor necessarily engaged in their work.

In educational research, the concept of study engagement is first built on two components: behavior (e.g., participation, effort, and positive behaviors) and emotion (such as interest, feelings of belonging, value, and positive emotions). Cognitive factor (e.g., self-discipline, investment in learning, and learning strategies) is later supplemented as the third component of study engagement (Fredricks and McColskey, 2012). Currently, the Glossary of Education Reform defines study engagement as “the degree of attention, curiosity, interest, optimism, and passion that students show when they are learning or being taught, which extends to the level of motivation they have to learn and progress in their education”1. In the same line with these conceptualizations, Schaufeli et al. develop the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale for Students (UWES-S) to measure students’ engagement with their learning. The scale was first developed to measure work engagement and then quickly became the most popular instrument applied in various populations. As its original construct, this UWES-S is also composed of three factors: vigor, dedication, and absorption. Since it was introduced, the UWES-S scale has been popularly used to measure tertiary students’ study engagement in various contexts (Carmona-Halty et al., 2019).

Study engagement of social work students in Vietnam is an interesting case for understanding study engagement at higher education level and its relations with factors at micro level (e.g., personal factors), mezzo level (higher education programs), and macro level (job market). In Vietnam, social work remains a new profession. Even though the literature shows that professional social work was introduced to Vietnam during French colonization period (Tran, 2015), social work was absent during war times, the first period of building the united socialist Vietnam. Social work has just become prominent in modern Vietnam recently due to efforts of the Vietnam Government to boost the role of social work profession to meet the growing demands from society. Within just a decade after Vietnam Prime Minister issued the Decision to boost social work profession in Vietnam in 2010 (often known as ‘Project 32’), BSW program has been rapidly initiated in many higher education institutes in Vietnam. Up to now, approximately 50 universities in Vietnam provide bachelor’s degree in social work (BSW) program. However, little is known about how these programs are operated in meeting students’ demand for their occupation training, in particular, and preparing for social work profession, in general.

We started our study from a perspective that higher education is essentially occupational education. When a student applies for a program at university, she/he is aiming at and investing in a certain profession for her/his future. Therefore, program-related and job-related factors may be significant factors that affect students’ study engagement. In the field of occupation studies, work engagement is often investigated under job demand-resource (JD-R) framework. JD-R theory emphasizes the impact of organizational environment on employees’ wellbeing and performance and focuses on two categories of organizational factors: efforts that the job demand the employees to make to accomplish their roles and the resources that the job and working environment provide for employees to achieve their goals (Tummers and Bakker, 2021). In this study, since our study objects are tertiary students who are investing in their future career, we approach study engagement from Kahn (1990) theory because this theory helps explore how personal expectations interact with de facto conditions, and these interactions contribute to students’ engagement with their study.

According to Kahn (1990), engagement is internally constructed. Kahn (1990), p.700 proposed that ‘people have dimensions of themselves that, given appropriate conditions, they prefer to use and express in the course of role performances… Engaging behaviors simultaneously convey and bring alive self and obligatory role. People become physically involved in tasks, whether alone or with others, cognitively vigilant, and empathically connected to others in the service of the work they are doing in ways that display what they think and feel, their creativity, their beliefs and values, and their personal connections to others’. With this conceptual approach, Kahn (1990) asserts that engagement is a state where a person’s personal and social dimensions are activated to complete their jobs, and this completion is, in return, to perform their own self and social connections. Furthermore, Kahn claims that engagement is constructed upon the meeting of three psychological needs, including meaningfulness, psychological safety, and availability. To be more specific, how engaged a person is when carrying out a task depends on the answers of three questions: (1) How meaningful it is for me to bring myself into this performance, (2) how safe it is to do so, and (3) how available I am to do so (p. 703).

Meaningfulness refers to how individuals perceive their investment of their physical, cognitive, and emotional energy into tasks as worth, valuable, and useful (i.e., whether what they receive deserves what they give) so that they can feel the meaning of their work and life. It is worth noting that Kahn, though likely referring to the ‘cost and benefit’ model, stresses not only on the rational calculation of cost and benefit but also on individuals’ perception of meaningfulness. Safety refers to students’ perception of their ability to show and employ themselves into doing tasks without the fear of any harm to their self-image, or status means that individual is able to show himself without fear of negative consequences. Kahn (1990) proposes that the sense of safety is created in an environment/situation which is predictable, secure, and trustworthy. Meanwhile, availability refers to students’ belief if they possess required physical, emotional, and psychological capacity to invest into role performance.

Based on Kahn (1990)‘s proposition, when examining the training program, we focus on the way the training program can bring to students what Kahn called ‘meaningfulness’, ‘safety’, and ‘availability’ so that students can feel their ‘self-in-role’ and examine how this contributes to students’ engagement.

To deepen the understanding of study engagement at higher education, this study focuses on social work major and makes comparisons between social work and some other majors provided in the same universities. The study aims at answering two core questions: (1) how social work students are engaged with their study and (2) how some training factors (such as course designs, course assessment, and lecturers) and job market factors (such as income and job opportunity) relate to students’ study engagement.

2 Research methods

2.1 Methodological approach and research procedure

Because little research on study engagement has been conducted in Vietnam, this research applied an exploratory sequential mixed-method approach, aiming at capturing the strengths of both qualitative and quantitative approaches (Creswell and Creswell, 2018), to explore tertiary students’ study engagement and how study engagement is related to their training program at university and job issues. The research was deployed in three phases. In the first phase, we conducted 22 semi-structured interviews with students and university lecturers. We used thematic analysis to identify common factors related to students’ study engagement. In phase two, we developed an online self-administered questionnaire to measure study engagement and the factors involved, based on the qualitative findings and Kahn (1990) theory. We then delivered the questionnaires to undergraduate students of 13 universities in Vietnam. In the last phase, we conducted five more semi-structured interviews with undergraduate students and lecturers to cross-check the quantitative data.

All participants participated in this study on a voluntary basis. An invitation letter together with a leaflet introducing the study was sent to participants first, and then, researchers approached them to check if they agreed to participate in the study.

The research design, ethical proposal, and research tools were reviewed and approved by IRB at VNU-Hanoi University of Social Sciences and Humanities.

The two research methods (semi-structured interviews and questionnaire survey) are described in detail in the following sections.

2.2 Semi-structured interviews

The study conducted 27 semi-structured interviews with tertiary students and lecturers. We followed five steps to develop interviewed guide suggested by Kallio et al. (2016). After identifying the prerequisites for using semi-structured interviews in this current study, a literature review of study engagement in higher education was conducted to formulate the preliminary interview guide. We piloted this interview guide with five undergraduate students before finalizing the interview guide.

In each interview session, participants were reminded about confidentiality and participants’ rights (e.g., the right to withdraw from the interview at any time) before the interview was conducted. Each interview often lasted from 60 to 75 min. Most of the interviews were conducted at a quiet café which was selected by the participants. All of the interviews were recorded with the permission of the participants.

2.3 Questionnaire survey

2.3.1 Questionnaire survey sample

There were 973 students from 13 universities who participated in the survey. In total, 469 students (48.2% of the total) are social work students, the remaining are from other majors, such as law, business, philosophy, and psychology. Of all undergraduate students who participated in the survey, 29.8% were first year students, 34.6% were on their second year, 16.8% on third year, and 18.8% on fourth year. All BA programs examined in this study lasted for 4 years.

Among 469 social work students who participate in the study, 80% are women, 19% are men, and 1% are LGBTQ+. Regarding living areas, 42.6% of participants came from rural areas, and the remaining 57.4% of participants came from urban areas.

2.3.2 Instruments

2.3.2.1 Study engagement scale

Upon the permission of Prof. Schaufeli, we use the version UWES-9S developed by Schaufeli and Bakker (2004). Research documents that this short form of study engagement scale has equivalent psychometric properties with the 17-item version (Carmona-Halty et al., 2019). The scale consists of three factors. The first factor is named ‘vigor,’ refers to students’ concentration in study, being ready to invest their effort in the study and being resilient when facing difficulty in studying. Vigor is measured in UWES-S via three items: ‘When I’m doing my work as a student, I feel bursting with energy’; ‘I feel energetic and capable when I’m studying or going to class’; ‘When I get up in the morning, I feel like going to class’. The second factor is called ‘dedication’, refers to students’ feeling of meaningfulness, enthusiastic, pride, and inspiration in their study. In the 9-item version of UWES-S, dedication is measured via three items: ‘I am enthusiastic about my studies’; ‘My studies inspire me’; and ‘I am proud of my study’. The last factor is named ‘absorption’ which means being fully and happily sunk in their study so that they may find it difficult to separate themselves from studying. This factor is measured via three items: ‘I feel happy when I am studying intensely’, ‘I am immersed in my studies’; and ‘I get carried away when I am studying’. Each item was measured on a five-point Likert scale with 0 = never and 4 = always. The higher score represents the higher level of study engagement. Cronbach’s alpha value is 0.83 for vigor, 0.86 for dedication, 0.87 for absorption, and 0.93 for the total scale, showing a good internal consistency of the scale.

2.3.2.2 Factors related to study engagement

Based on semi-structured interviews with social work students, this study assesses four sets of factors identified by thematic analysis of qualitative data as factors contributive to students’ study engagement: sociodemographic characteristics, students’ major; training program organization; and job market issues. Except for sociodemographic factors, students are asked to assess how they agree with the statements describing the aspects of the factors on a five-point Likert scale from 0 = ‘I totally disagree’ to 4 = ‘I totally agree’.

1. Sociodemographic factors of students: sex, living area (rural vs. urban), and students’ academic performance (assessed by their GPA).

2. Factors related to the training program: meaningfulness (‘my major has a high social recognition’, ‘my major is contributive to social development’, ‘Course assessment helps me to understand my ability’, ‘Course design allows me to show my ability’, ‘Studying my major contributes to my personal growth), safety (‘Course materials are accessible’; ‘Many of the lecturers in my major program are well-known experts’; ‘When I meet difficulty in my study, lecturers are quite supportive’; ‘The assessment is fair’); availability (‘the training program help connect me with job opportunity’; ‘the training program prepares me well to do my job in the future’; (4) ‘what I have learnt from this program is practical and applicable to my daily life’). All factors are assessed on a five-point Likert scale with 0 = ‘I totally disagree’ and 4 = ‘I totally agree’

3. Factors related to job-market: income (jobs in my field are low paid) and job opportunity (‘it is not easy to find a job in my field’). All factors are assessed on a five-point Likert scale with 0 = ‘I totally disagree’ and 4 = ‘I totally agree’.

2.3.3 Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 23.0. We resorted to descriptive statistics (frequency, mean-value, and standard deviation) to describe the central tendency of study engagement and inferential statistics (independent sample t-test, paired sample t-test, one-way ANOVA, chi-square test, and Pearson’s test) to compare between social work (SW) and non-social work (NSW) majors and test the relationship between variables.

3 Results

3.1 How Vietnamese social work students engage with their study

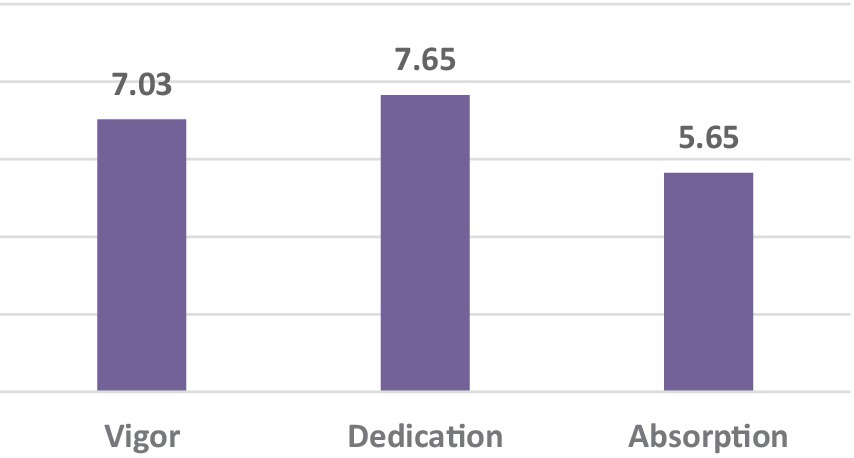

In a [0:36] scale, it appears that Vietnamese social work students are quite engaged with their social work education (mean = 20.3; SD = 7.7). The following (Figure 1) shows the specific mean scores of each dimension of study engagement, as reported by social work students.

On UWES-9S, each dimension of study engagement has a range of 0–12, and the results show that Vietnamese social work students score highest on dedication dimension (M = 7.65, SD = 2.72) followed by Vigor (M = 7.03, SD = 2.78). They score lowest in absorption dimension (M = 5.65, SD = 3.09). Paired sample t-test shows that the differences between these dimension scores are statistically significant: Vigor–Dedication has t(468) value = 7.27 (p < 0.001); Vigor–Absorption has t(468) value = 12.33 (p < 0.001); and Dedication–Absorption has t(468) value = 18.36 (p < 0.001).

Comparing between social work and non-social work students about their study engagement, one-way ANOVA analysis showed that the difference in the level of study engagement between social work students and non-social work students is significant (F(1,973) = 9.051; p < 0.01). It is interesting that whereas the mean score of social work students’ study engagement is a little bit higher than that of students from other majors (20.3 and 18.8, respectively), standard deviation is also higher (7.7 and 7.4, respectively).

Result shows that Vietnamese social work students are more engaged with their study than their non-social work counterparts.

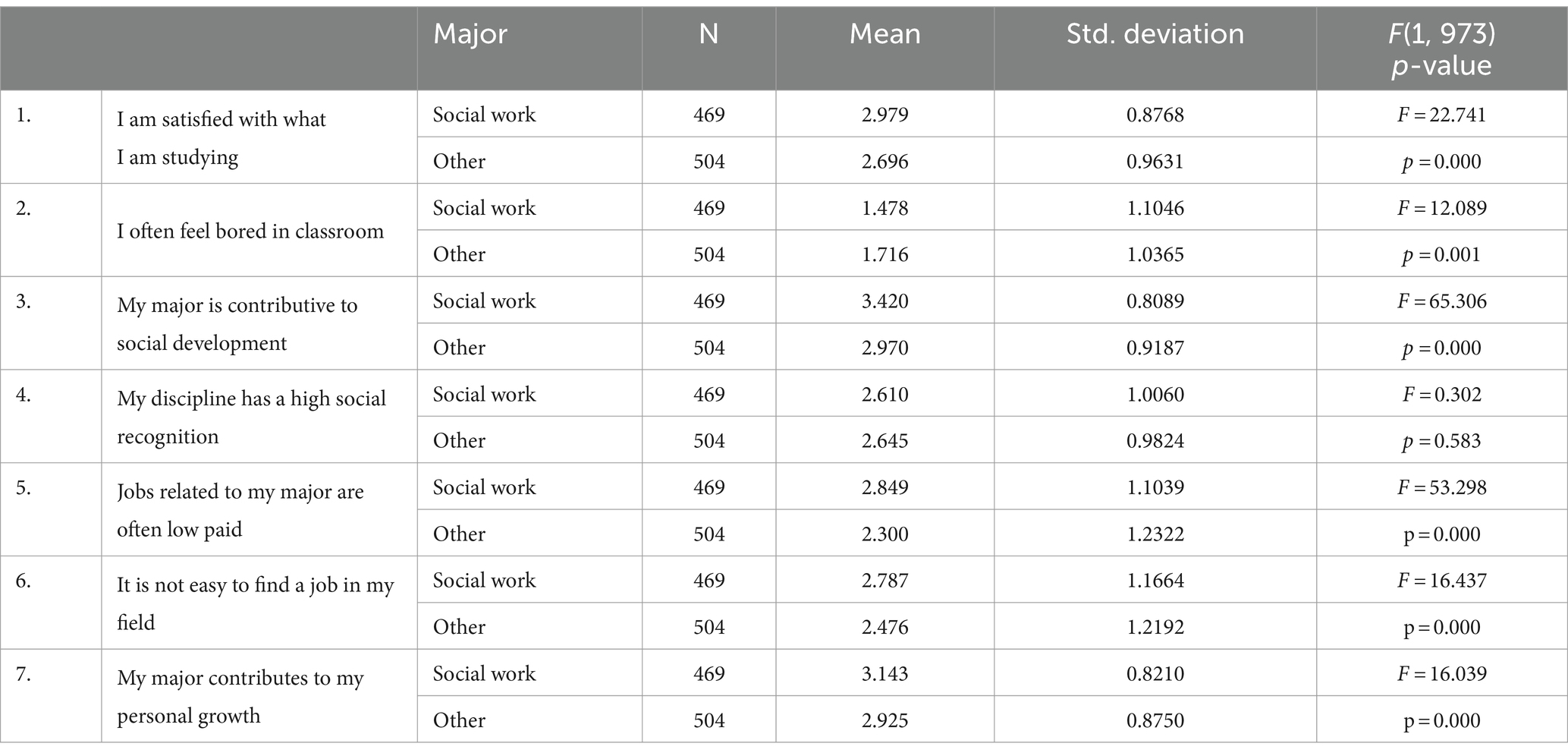

To further understand students’ study engagement, we also compare between social work students and non-social work students in the way they perceive their major and assess job prospects in their field. The score for each item ranges from 0 to 4, with 0 = ‘totally disagree’ and 4 = ‘totally agree’. The higher the score the more the students agree with the statement (Table 1).

Table 1. Students’ perception of their majors: comparison between social work students and students from other majors.

One-way ANOVA test results show that except for ‘My discipline has a high social recognition’, the differences between social work students and other majors are statistically significant. Students from social work major and the other majors assessed social recognition of their major at the same level (mean scores are approximately 2.6 point on a five-point Likert scale). Compared with students from other majors, social work students are more satisfied with their major (higher mean score, lower SD, F(1,973) = 22.741, p < 0.001). Social work students feel less bored in classroom than their counterparts (lower mean score, however a little bit higher SD, F(1,973) = 12.089). Social work students also perceive that their discipline is significant for society (their major is significantly contributive to social development), and that studying in their major help contribute to their personal growth at a higher level than students from other majors (higher mean score, lower SD, F(1,973) = 65.306 and 16.039, respectively, p < 0.001). However, social work students also highly agree that it is difficult to find a job in their discipline and jobs in social work area are low paid than students from other disciplines (higher mean scores, lower SDs, F(1,973) = 16.432 and 53.298, respectively, p < 0.001).

The study finds that Vietnamese social work students are more satisfied with their major than non-social work students; however, they assess job prospects (income and job opportunity) in their field more negatively than their non-social work counterparts.

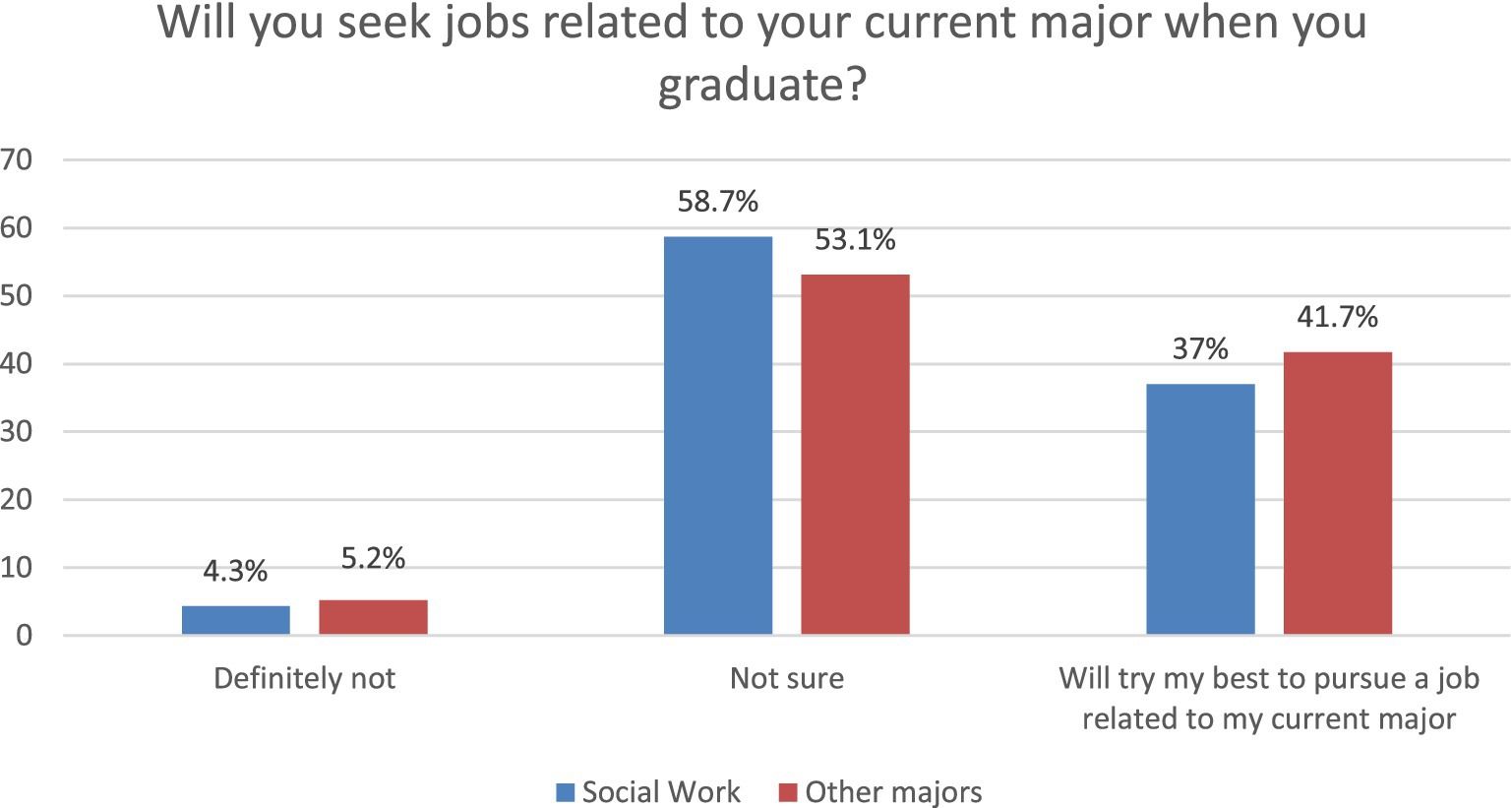

When being asked if they would pursue jobs related to their current major, the proportion of social work students who intended to pursue social work job after graduation is lower than that of students from other majors, as presented in Figure 2.

Results show that whereas 41.7% students of other majors determined to pursue major-related job when they graduate, this rate among social work students is only 37%, as presented in Figure 2. This result is consistent with the above result that according to social work students, compared with non-social work students, social work jobs are normally lower paid, and it is not easy to find a job in social work field. In addition, Vietnamese social work students are, in general, from families with more disadvantaged economic conditions. They received less financial support from their family than their counterparts. In total, 26.2% of social work students reported that they had to pay for the expenses for their tertiary education by themselves, whereas the rate among students of other majors is 19.1%. The differences between social work students and other-major students in financial burden is statistically significant (X2 = 11.820; df = 4; p < 0.05).

On one hand, I want to do social work when I graduate. I long to apply what I have learnt from my program in work. On the other hand, I need to earn money. My parents and my little siblings rely on me [financially]. I have to take care of them. I need to find a job that helps me to feed my family. But I also don’t want to give up social work. I feel really stressed about that. (Student, 4th year, Social Work major)

Our study document that, unfortunately, the more Vietnamese social work students are close to graduate, the more uncertain they are in pursuing social work jobs in their discipline (Pearson R = −0.125; p < 0.05, n = 468).

As presented in Table 2, more than 40% of Year 1 and Year 2 social work students reported that they were determined to do social work after graduation, and this proportion of Year 3 students decreased to 37.9%. Remarkably, only 29.4% of Year 4 students wanted to pursue the job they were being trained in.

Table 2. Students’ intention to pursue their major-related jobs and their school year by their school year.

It seems that Vietnamese social work students are engaged with their study but less engaged with social work profession.

3.2 Factors associated with social work students’ study engagement

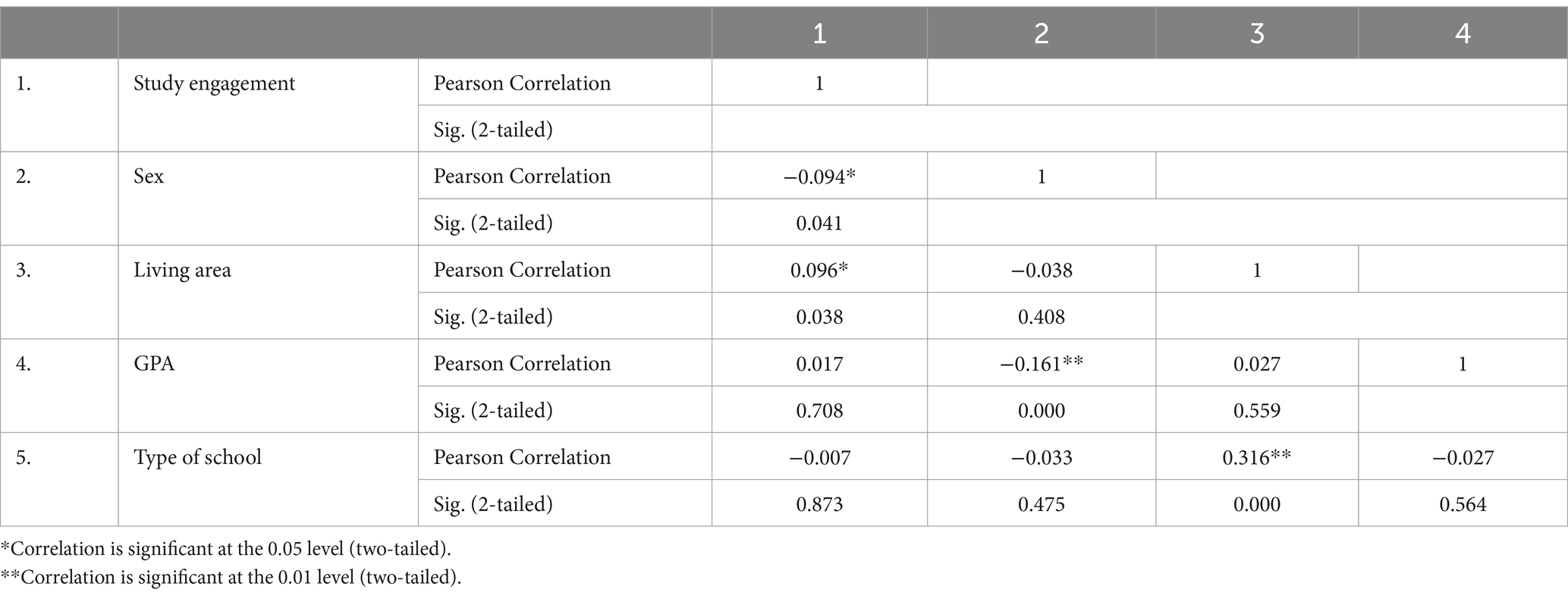

This part focuses on the factors contributive to study engagement as reported by the students during semi-structured interviews and clarifies how they are related to students’ engagement with their study (Table 3).

Different from our expectation that the more the students are engaged with their study, the higher GPA they may achieve; our results show that GPA is not statistically related to study engagement. However, it means that the students are engaged with their study, and engagement has no effect on their academic results.

However, the lecturers we interviewed in phase 3 seem not to be surprised with this result.

I think the result [no relationship between study engagement and GPA] is understandable. You know, GPA is of great significance to us Vietnamese, so that since early education [primary and secondary education] the kids are well trained to be able to achieve good scores in exams. Sometimes they may be technically good at getting good scores rather than being good at studying. I mean, they don’t need to love study to be good at studying (Lecturer, public university)

Another surprising finding is that type of school (whether the school is public or private) also does not relate with students’ study engagement. The social work curriculum in public universities in Vietnam tend to be more academic, knowledge-based training, whereas private universities offer a more practice-based training with more opportunities for students to connect with social work agencies and projects. In addition, the properties and facilities of the private universities sampled in this study are much more modern, large, comfortable, and convenient for students and their study than their public counterparts. Hence, we proposed that students at private school would be more engaged with their study. Actually, semi-structured interviews show that students at private schools do highly appreciate the modern and convenient properties and facilities of the school. Otherwise, students at public universities report that they are proud of their school’s history, reputation, and well-known faculties.

Yes, my university is too crumped. But I am proud of being enrolled in this university. It is one of the oldest and the best universities in my field. Best faculty, too. (Student, 2nd year, public university).

However, there is a statistically significant association between students’ study engagement and their sex and living area. Our study finds that female social work students are slightly more engaged with their study than their male counterparts, and rural students are more engaged with their study than urban students.

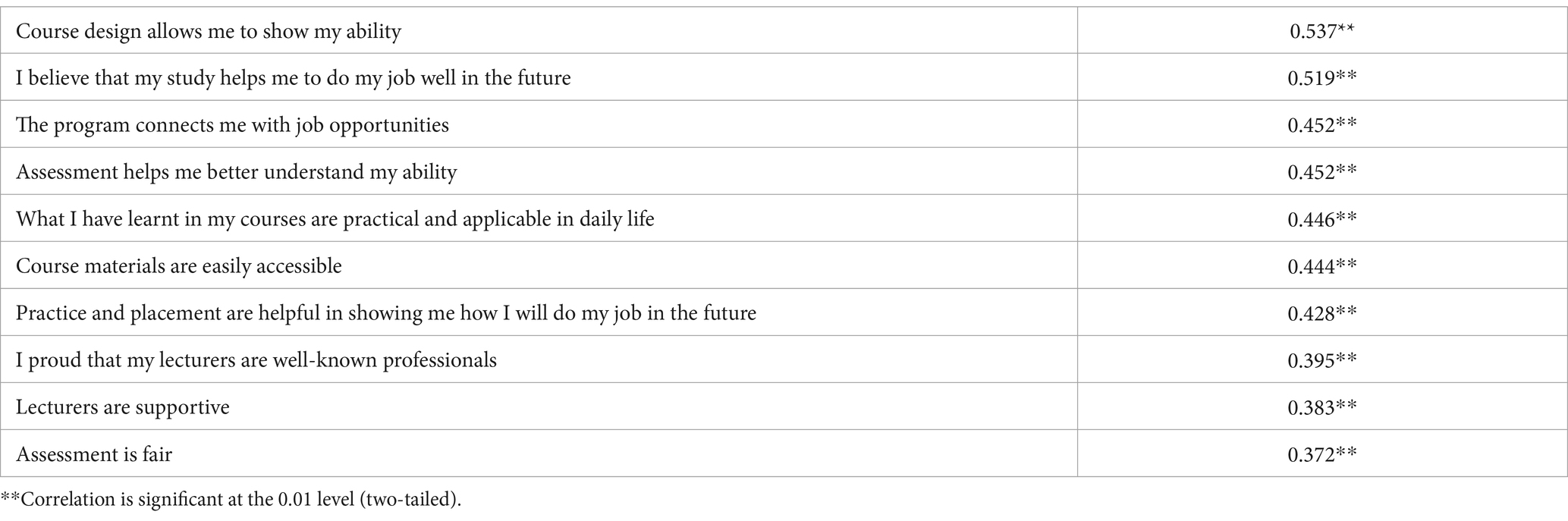

To better understand what underlies social work students’ engagement with their study, we test the correlation between social work students’ study engagement and some job-related and program-related factors. The results are as follows:

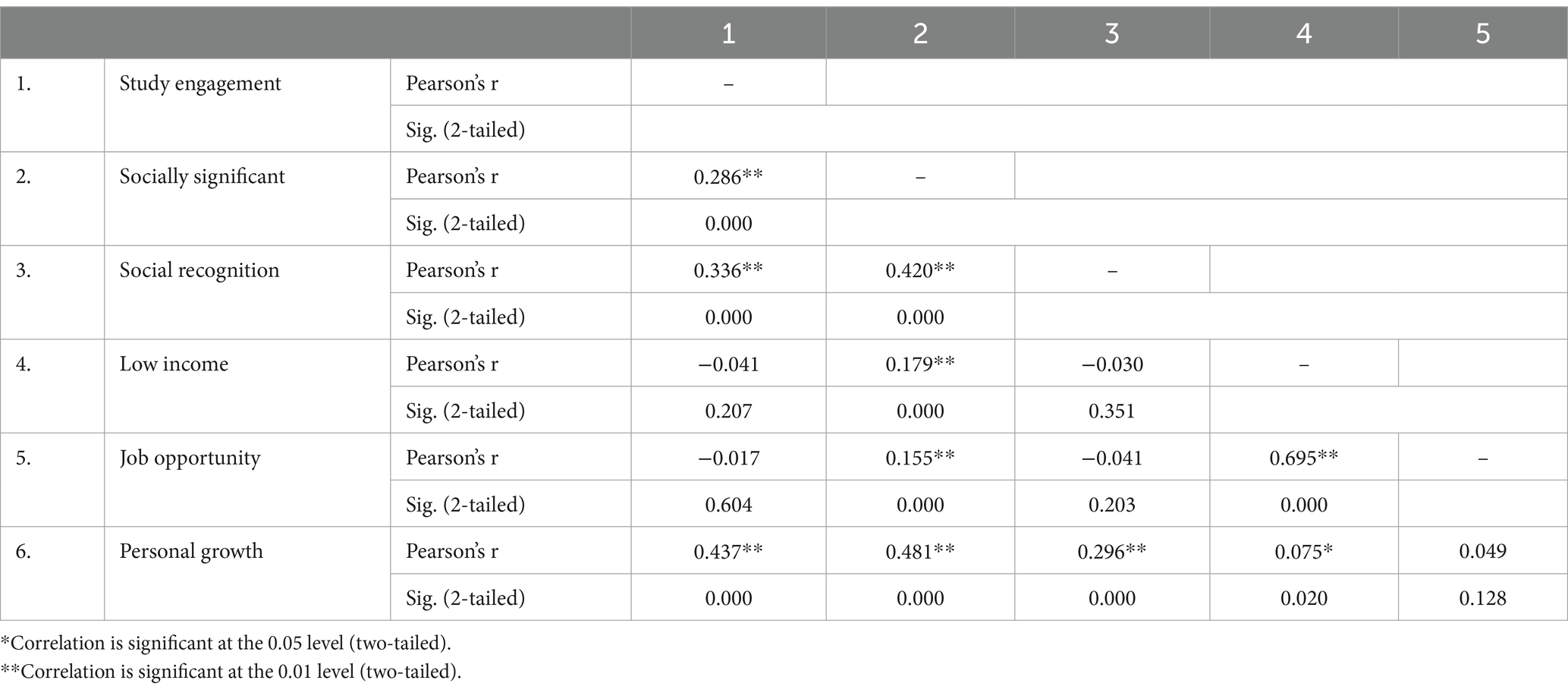

Contrary to our expectation, low income and difficulty in finding job in social work have no effect on students’ study engagement. However, the study finds a strong and positive association between study engagement and students’ perception of how social work education contributive to their personal growth (Pearson’s r = 0.437, p < 0.001), showing that the more students perceive that their education program helps them improve themselves, the more they are engaged with their study. Similarly, students are feeling proud that their major has high social recognition, and students’ perception that their major is socially significant (contributive to social development) is found positively associated with students’ study engagement (Table 4).

The following table presents the results of the correlations between social work students’ study engagement and factors related to program organization.

Among the factors related to the way social work program is organized in university (faculty, course materials, assessment, and relationships between lecturers and students), bivariate correlation results show that course designed in a way that allows students to show their ability which is the factor and has strongest and positive relationship with students’ study engagement (r = 0.537, p < 0.01), followed by students’ perception that their study prepares them well for doing social work jobs (r = 519; p < 0.01). If the program connects students with job opportunities, assessment helps them understand their ability, the knowledge, and skills they learn are practical and applicable in their daily life, course materials are accessible, and placement helps students to be aware of how social workers do their job; the students’ level of study engagement is positively and strongly strengthened. In addition, lecturers’ good reputation and being supportive to students and fair assessment also positively contribute to students’ study engagement with a moderate strength (Table 5).

Table 5. Bivariate correlation coefficients between study engagement and factors related to program organization.

4 Discussion

In general, the results show that Vietnamese social work students are quite engaged with their study. Specifically, their dedication score is highest among the three dimensions of study engagement, followed by vigor, whereas their absorption score is remarkably lower than the above dimensions. The differential magnitude of each dimension is also documented in a research on Chilean undergraduate students, according to Carmona-Halty et al. (2019). These results are reasonable because dedication and vigor reflect students’ affection and passion for the profession that they have chosen, while absorption dimension requires intensive efforts and concentration which young persons as undergraduate students may lack. According to Erikson (1950), young adulthood is a developmental stage when individuals focus on establishing and building upon relationships. Career is of great importance; however, building up intimacy is also at the center of concern for individuals of this age, which may reduce their concentration for study. However, more study on different populations is needed to observe how different sociodemographic groups may differ in each dimension of engagement.

Our results further acknowledge that Vietnamese social work students are more engaged with their study than their non-social work counterparts. Social work students report a higher level of satisfaction with what they have learnt from their major, they feel less bored in classroom, and they find that their major is significant. However, higher value of standard deviant suggests that the level of study engagement is quite varied among Vietnamese social work students.

Our findings strongly support Kahn (1990) theory. When the training programs can bring about the sense of meaningfulness, safety, and availability, it is more likely that students may develop higher level of study engagement. How social work students perceive the social significance and social recognition of their major represents what Kahn calls ‘meaningfulness’. The reasons for why these factors significantly explain social work students’ engagement with their study are that social work has been demonstrated as a profession attached with positive values as “empowerment and respect,” “social justice,” and “compassionate vocation” (Levesque et al., 2019) or “work for the good of other” (Millington, 1981). Our results documented a statistically significant and positive association between students’ study engagement and their perception of major as being socially significant and having positive social recognition.

In addition, as a helping profession, social work education provides students with knowledge, skills, and values necessary to support their clients. While doing so, social work education also helps students better understand themselves and work better with their personal and social life. It is demonstrated that experiences during studying social work help increase students’ self-awareness (Bartkeviciene, 2014) and hence increase their sense of personal growth. Therefore, studying social work can boost students’ sense of meaningfulness, which, in turn, strengthens students’ engagement with their study. This study found that correlations between factors such as ‘courses contribute to my personal growth’, ‘courses allows me to show my ability’, ‘assessment helps me better understand my ability’; and ‘what I have learnt in my [social work] courses are practical and applicable in daily life’ and students’ level of study engagement are positive and strong.

Unanimously, our findings show that students’ perceptions of ‘course materials are easily accessible’, ‘lecturers are well-known professionals in the field’, ‘lecturers are supportive’, and ‘assessment is fair’ positively contribute to students’ study engagement. These are factors that create a learning environment which is trust-worthy, secure, supportive, and predictable. As claimed by Kahn (1990), such an environment boosts the sense of safety and hence strengthens personal engagement with their tasks.

In the same line with this proposition, our findings document that students’ belief that ‘study helps me to do job well in the future’, ‘the program connects me with job opportunities’, and ‘course design allows me to show my ability’ are positively associated with students’ study engagement, and these associations are at moderate level. It appears that students’ sense of availability—whether the training program can help them find themselves able to do their trained profession in the future—is also significantly contributing to their study engagement at a lower level of magnitude if compared with meaningfulness.

Contrary to our expectation, job prospects such as income and job opportunity are not related to students’ engagement with their study. Vietnamese social work students perceive that social work profession is low paid job. They also report a stronger belief that it is uneasy to find a job in their field than their non-social work counterparts. Accordingly, a remarkably smaller proportion of social work students confirm that they will pursue social work profession after graduation, whereas non-social work students report a much stronger commitment with the profession in which they are being trained. In addition, the more social work students are close to graduation, the more they are uncertain about pursuing social work job. These results suggest that social work program is attractive to Vietnamese students, however social work jobs are however unattractive. In fact, this finding is understandable because social work remains a new profession in Vietnam. Recently, Vietnam Government has paid many efforts to boost social work education and social work profession via national projects such as the commonly known ‘Project 32′ signed by Prime Minister in 2010, and then, Prime Minister’s Decision No.112 was signed in 2021 to develop social work profession in 2010–2020 and 2021–2030, respectively. These efforts help make social work more well-known to the public, resulting in an increase in students’ applications to BSW programs. However, work positions for social workers in Vietnam have still been limited and low paid.

In summary, we started our study with a premise that higher education was career-oriented training, and since we human beings were rational, the students’ study engagement would be associated with occupation-related calculation (whether I can get job in this field, whether salary in this field is adequate) and learning benefits provided by the program. However, our results show that study engagement is not related much to rational calculation. Instead, students’ study engagement is more associated with emotional and social experiences and students’ motivation to improve themselves and perform their strengths. Therefore, the results suggest that in order to boost students’ engagement with their higher education, the training program should pay attention to create more opportunities to help students perform their personal strength, let the students perceive the social significance of their major, and increase students’ sense of safety and availability.

As mentioned above, another remarkable finding of this study is that ‘low income’ (students perceive that social work jobs are low paid) and ‘job opportunity’ (students perceive that it is difficult to get a job in their field) are not significantly associated with students’ study engagement. In occupation studies, low income has been demonstrated to be a condition reducing employees’ work engagement (Siegrist, 1996). However, our findings show that financial rewards and accessibility to labor market have no relationship with students’ engagement with their major. We believe that the reason for this result is although higher education is occupational training and career-oriented, students mostly interact with learning process and conditions rather than occupation-related factors. Therefore, their study engagement depends on mostly training factors rather than occupational factors. However, in this study, it is worth noting that social work students reported a higher level of hesitation to pursue social work job when they come closer to graduation. This means though social work students are more engaged with their study than students from other majors, social work profession remains unattractive for them. In the long run, this situation may negatively affect social work education at tertiary level because education at tertiary level is basically occupation-oriented. Hence, the study suggests that policymakers should pay more attention to reduce the gap between study engagement and profession commitment in the field of social work in Vietnam.

To better understand this finding, it should be noted again that social work is still a new profession in Vietnam. Therefore, the findings that students love studying social work but do not want to do social work may be also a result of situation. Due to the national projects promoting social work profession in Vietnam, social work becomes more well known to the public, so it attracts high number of students enrolling in social work program in universities. However, the more they know about social work career, the less they are committed to social work profession because of the limitedness of job opportunity and low income.

5 Practical implication

The findings of this study suggest that, in order to boost students’ study engagement, universitiesand educators should develop strategies to boost the students’ perception of meaningfulness, safety, and availability. Students will find meaningfulness if they perceived that their major program has high social recognition and is contributive to social development. In addition, the more the courses provided in the program can help students understand and show their ability and help them to improve themselves, the more the students will be engaged with their study. Meanwhile, students’ perception of safety can be reached if course materials are made accessible; lecturers show their supportive attitude to students’ learning if the faculty staff is well-known experts in the field. Finally, the training program can increase their students’ study engagement by ensuring their perception of availability. Strategies to increase students’ perception of availability is creating more chances to connect students with job opportunity, ensuring that knowledge, skills, and professional attitudes provided in each courses are practically related to occupation so that students can feel that they are well prepared to do their job in the future. Moreover, if the training program can provide knowledge and skills which students can applied in their daily life, they will be more interested in and engaged with study.

6 Limitations of the study and recommendations for future research

As an exploratory study, the current study has some limitations. The study is limited in providing a more rigorous and comprehensive understanding of how program-related and job-related factors contribute to students’ study engagement, especially when conceptualizing program-related factors into three aspects as meaningfulness, safety, and availability, as suggested by Kahn (1990). We developed the items for examining program-related and job-related factors based on qualitative interviews with undergraduate students in combination with Kahn (1990)’s suggestions in an exploratory approach. Our results suggest that it is worth for future research to develop a more reliable and rigorous measure of program effect in accordance with Kahn’s theory. Moreover, we used convenient sampling strategy for questionnaire survey; even though the sample size is quite high, the findings are not generalizable. However, the findings of this study provide some considerable suggestions for future research in establishing an explanatory framework for study engagement at higher education level.

7 Conclusion

In comparison to students from some other majors, Vietnamese social work students are more engaged with their study and show a more positive perception of their major. However, they perceive that social work profession brings lower income, and it is more difficult to find a job in social work than in other fields. However, the study documents that job prospects such as income and job opportunity have no association with Vietnamese tertiary students. The study strongly supports Kahn (1990) proposition that if the training program can provide students’ sense of meaningfulness, safety, and availability, it can increase students’ engagement with their study. However, further analysis acknowledges that this engagement seems not strong enough to motivate students’ commitment to the profession which the students are being trained at universities. The exploration of social work education in Vietnam suggests that low income and limited job opportunities may neutralize the effect of study engagement on profession commitment. This might heighten the risk that students give up the profession in which they are trained at university to seek different occupations, despite how engaged they feel to their study at university.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Author contributions

TN: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TB: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. LN: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing. HD: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. NN: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. HM: Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. HN: Data curation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by VNU-Hanoi University of Social Sciences and Humanities. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study is funded by Vietnam National University under Project code QG.21.34.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Assunção, H., Lin, S. W., Sit, P. S., Cheung, K. C., Harju-Luukkainen, H., Smith, T., et al. (2020). University student engagement inventory (Usei): transcultural validity evidence across four continents. Front. Psychol. 10:2796. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02796

Bartkeviciene, A. (2014). Social work students’ experiences in “self” and professional “self” awareness by using the art therapy method. Eur. Sci. J. 10, 12–23.

Boulton, C. A., Hughes, E., Kent, C., Smith, J. R., and Williams, H. T. P. (2019). Student engagement and wellbeing over time at a higher education institution. PLoS One 14:e0225770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225770

Bowden, J. L.-H., Tickle, L., and Naumann, K. (2021). The four pillars of tertiary student engagement and success: a holistic measurement approach. Stud. High. Educ. 46, 1207–1224. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2019.1672647

Carmona-Halty, M. A., Schaufeli, W. B., and Salanova, M. (2019). The Utrecht work engagement scale for students (Uwes-9S): factorial validity, reliability, and measurement invariance in a Chilean sample of undergraduate university students. Front. Psychol. 10:1017. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01017

Collaco, C. (2017). Increasing student engagement in higher education. J. High. Educ. Theory Prac. 17, 40–47.

Creswell, J. W., and Creswell, D. J. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches, California, Sage Publications.

Fredricks, J., and Mccolskey, W. (2012). “The measurement of student engagement: a comparative analysis of various methods and student self-report instruments” in Handbook of research on student engagement. eds. S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, and C. Wylie (New York: Springer)

Hart, S. R., Stewart, K., and Jimerson, S. R. (2011). The student engagement in schools questionnaire (Sesq) and the teacher engagement report form-new (Terf-N): examining the preliminary evidence. Contemp. Sch. Psychol. 15, 67–79. doi: 10.1007/BF03340964

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 33, 692–724. doi: 10.2307/256287

Kallio, H., Pietil, A. A.-M., Johnson, M., and Kangasniemi, M. (2016). Systematic methodological review: developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 72, 2954–2965. doi: 10.1111/jan.13031

Kim, H. J., Hong, A. J., and Song, H.-D. (2019). The roles of academic engagement and digital readiness in students’ achievements in university e-learning environments. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 16:21. doi: 10.1186/s41239-019-0152-3

Levesque, M., Negura, L., Gaucher, C., and Molgat, M. (2019). Social representation of social work in the Canadian healthcare setting: negotiating a professional identity. Br. J. Soc. Work., 1–21. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcz005

Maslach, C., and Leiter, M. P. (1997). The truth about burnout: How organizations cause personal stress and what to do about it, San Francisco, Jossey-Bass.

Millington, G. (1981). The selection and personality development of social work students. J. Furth. High. Educ. 5, 69–75. doi: 10.1080/0309877810050208

Schaufeli, W. B. (2013). “What is engagement” in Employee engagement in theory and practice. eds. C. Truss, K. Alfes, R. Delbridge, A. Shantz, and E. Soane (London: Routledge)

Schaufeli, W. B., and Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 25, 293–315. doi: 10.1002/job.248

Siegrist, J. (1996). Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1, 27–41. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.1.1.27

Tran, K. (2015). Social work education in Vietnam: trajectory, challenges and directions. Int. J. Soc. Work Human Ser. Prac. 3, 147–154. doi: 10.13189/ijrh.2015.030403

Keywords: study engagement, UWES-9S, higher education, program organization, major significance, job market

Citation: Nguyen TTN, Bui TTH, Nguyen LT, Dao HT, Nguyen NL, Mai HT and Nguyen HTT (2024) ‘Love, Love not’—a discovery of study engagement at higher education and the factors involved. Front. Educ. 9:1367465. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1367465

Edited by:

Ana B. Bernardo, University of Oviedo, SpainReviewed by:

Celia Galve González, University of Oviedo, SpainMartina Blašková, Police Academy of the Czech Republic, Czechia

Anggun Prasetyo, Diponegoro University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2024 Nguyen, Bui, Nguyen, Dao, Nguyen, Mai and Nguyen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nguyen Thi Nhu Trang, Maiphivn@yahoo.com

Trang Thi Nhu Nguyen1*

Trang Thi Nhu Nguyen1* Thai Thi Hong Bui

Thai Thi Hong Bui Lan Thi Nguyen

Lan Thi Nguyen