- 1Research Centre on Didactics and Technology in the Education of Trainers, Department of Education and Psychology, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal

- 2Retired, Westerville, OH, United States

The increase of the number of students with disabilities in Higher Education, including students with intellectual disability, emphasizes the need for Higher Education Institutions to provide support for their inclusion and learning. Within inclusive Higher Education peers can have a fundamental role through Peer Mentoring Circles. This qualitative study aims to understand the perceived experiences of members of Peer Mentoring Circles, within the scope of a program that provided academic support, during an academic semester, to mentees with intellectual disability. Data collection included semi-structured interviews with members of the Circles (two mentees and seven mentors), and the facilitator’s field notes. Content analysis was used to analyze the data. Through the data analysis, two categories were identified: components of the Peer Mentoring Circles program and experiences of the members of the Circles. The data generated suggest that both mentors and mentees had positive experiences, contributing to the development of the mentees’ skills. Based on literature and the data generated emerged the proposal for the Peer Mentoring Circles program with a broad set of guidelines for its implementation, which can set the baseline for developing future peer mentoring programs in Higher Education aimed not only at students with disabilities, but also at other students with support needs such as international students.

1 Introduction

The increase of the number of students with disabilities in Higher Education, including students with Intellectual Disability (ID), has emphasized the need for Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) to provide support for their inclusion and learning.

According with American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD), the oldest and largest professional society concerned with this disability, intellectual disability is characterized by significant limitations in both intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior that originates before the age of 22″ (AAIDD, 2024).

The movement toward inclusive Higher Education for students with ID continues to progress; however, merely opening the doors of the university is not enough, as their academic success requires support for their inclusion and learning at this level of education (Lewis, 2017).

In this regard, peers can have an important role in this process by performing numerous functions in supporting these students, as observed in various inclusive university programs in the United States (Carter et al., 2019), with Peer Mentoring Circles standing out (Griffin et al., 2016). Nevertheless, questions persist regarding the support of these students for their participation in university life (Carter et al., 2019; Araten-Bergman and Bigby, 2022; Heron et al., 2023).

Heron et al. (2023) recommends that, to address the existing gaps in the literature on peer mentoring for students with ID, it is important to understand the perceived experiences of those involved in this process. In line with these ideas, Griffin et al. (2016) also reinforce the need for descriptions of promising practices related to peer mentoring in Higher Education. According to the same authors, this lack of information causes HEIs to work largely through trial and error, instead of benefiting from previous successes and lessons learned at other HEIs.

Therefore, to address this identified need, and after presenting the theoretical background and the adopted methodology, this article describes the Peer Mentoring Circles program developed as part of an inclusive pilot program at an HEI to support the participation of individuals with ID in the selected undergraduate courses (fully included in the university courses). Subsequently, the presentation and interpretation of the data are discussed. Finally, conclusions are drawn, addressing both limitations and recommendations for future research, and the proposal for the Peer Mentoring Circles program is presented.

2 Peer mentoring in higher education

The increase of the number of students with disabilities in Higher Education, including students with ID, has emphasized the need for the university system to provide support for their inclusion and learning (Cardinot and Flynn, 2022; Bussu and Burton, 2023). According to Carter et al., (2019), mentoring is a promising mechanism that can contribute to this process, where peers can offer support and strategies for the academic, professional, social, and personal development of these students.

Crisp and Cruz (2009) describe mentoring as a collaborative, formal or informal, short, or long-term, dynamic, and reciprocal relationship that can focus on individual development and include various types of support. The literature (e.g., Terrion and Leonard, 2007; Wilt and Morningstar, 2020) recommends peer mentoring for providing support in Higher Education.

According to Terrion and Leonard (2007), peer mentoring is a significant opportunity for the development of skills for both mentees and mentors. They mention that its implementation is considered an effective intervention to ensure the success of students with support needs (Terrion and Leonard, 2007) in the university context. Darwin and Palmer (2009) highlight alternative mentoring methods that can offer advantages over the traditional dyadic approach, with Mentoring Circles being an innovative example of these alternative methods.

2.1 Peer Mentoring Circles: a peer mentoring model in higher education

One of the peer mentoring models suggested for Higher Education is Mentoring Circles (e.g., Darwin and Palmer, 2009; Griffin et al., 2016; Davis, 2019; Araten-Bergman and Bigby, 2022; Krech-Bowles and Becht, 2022; Bussu and Burton, 2023). According to Araten-Bergman and Bigby (2022), the term Mentoring Circles is highlighted in the literature from North America and Australia, in the context of network-building initiatives.

Peer Mentoring Circles are an innovative strategy to develop support networks in Higher Education (Darwin and Palmer, 2009; Felton-Busch et al., 2013; Griffin et al., 2016). Articulating the challenges faced by students in Higher Education with the concept of Mentoring Circles could be a tool to create an environment where students are best supported (Davis, 2019).

Griffin et al. (2016) mention that the group of mentors supporting a mentee is called a Support Circle or Mentoring Circle, where each circle has a mentor responsible for mediating with the facilitator and the members of the Circle. According to the authors, a Mentoring Circle structure supports each mentee, and mentors are matched based on individual goals and the type of support needs of the mentee. The number of mentors in each circle varies; some mentees may progress with a smaller circle, while others prefer a larger number of mentors in their Circles.

The main difference between group mentoring and Mentoring Circles is the existence of a facilitator in the latter, whose main role is to guide the mentoring process. Therefore, Mentoring Circles are small groups of peers guided on a variety of topics under the direction of a qualified professional facilitator.

The required characteristics of mentors can vary depending on the type of support. Terrion and Leonard’s (2007) taxonomy of mentor characteristics consists of a framework describing effective characteristics in building authentic relationships with mentees. Consulting this taxonomy can be crucial for decisions about the selection, training, and evaluation of mentors, as it is essential to understand the type of mentor most suitable for the role.

Mentoring Circles have been described as useful for a wide range of students with support needs for participation in university life, including vulnerable students (Terrion and Leonard, 2007), students with and without disabilities (Athamanah et al., 2020; Cardinot and Flynn, 2022; Rooney-Kron et al., 2022), including students with ID (Griffin et al., 2016; Araten-Bergman and Bigby, 2022), indigenous students (Felton-Busch et al., 2013), and international students (Davis, 2019).

This study focuses on Mentoring Circles involving students with disabilities, particularly those with Intellectual Disability.

2.2 Peer Mentoring Circles in the context of inclusive higher education for students with intellectual disability

The movement toward inclusive Higher Education for students with ID, aligned with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations, 2006) and Sustainable Development Goal 4 - Quality Education (United Nations, 2015), continues to advance.

However, merely opening the doors of HEIs to this population is not enough, as their academic success requires support for their inclusion and learning at this level of education (Lewis, 2017). In this sense, peers can have a fundamental role in supporting this population (Carter and McCabe, 2021), as observed in various inclusive university programs in the United States (Carter et al., 2019), with Mentoring Circles standing out (Griffin et al., 2016).

According to Jones et al. (2015), inclusive Higher Education commits to valuing all individuals and providing opportunities for students to interact, collaborate, and learn from each other. These authors emphasize that an inclusive campus generates natural support within the academic community to engage all students significantly in university life, offering students with disability, including those with ID, the same opportunities, and choices.

Peer mentoring programs in Higher Education provide an opportunity for students with and without ID to learn, socialize, and work together in inclusive support environments (Athamanah et al., 2020). Araten-Bergman and Bigby (2022) note that the Peer Mentoring Circles model has been used as a broad set of practices and strategies to create and maintain networks for people with ID. The translation of these peer support practices into the context of inclusive Higher Education for students with ID is a relatively recent initiative (Wilt and Morningstar, 2020).

In the view of Griffin et al. (2016), the Mentoring Circles model represents an approach to supporting the academic and social development of university students with ID. According to same authors, this model accommodates various support needs of these students while promoting their inclusion in the academic community and minimizing the need for formal support provided by HEIs facilities.

The nature of these programs varies widely within and between campuses. Carter and McCabe (2021) note that some programs invite peers to provide academic support, while others focus on social support. These mentoring experiences may differ in terms of time commitment (e.g., daily, weekly, occasionally), structure (e.g., individually, in groups), and compensation (e.g., paid work or rewarded with credits or voluntary).

According to Krech-Bowles and Becht (2022), the main components of a mentoring program for students with ID in Higher Education include: (i) mentoring orientations, (ii) regular supervision, (iii) communication and collaboration system, (iv) partnership/peer relations, (v) high expectations for students with ID, (vi) identification of natural supports, (vii) encouragement of self-determination. Peers can have various roles depending on the type of support and the needs of each student with ID, in facility of their inclusion and learning in the university context (Carter et al., 2019; Workman and Green, 2019). Some of the mentors’ roles included: (i) academic in-class support (e.g., providing assistance such as note-taking, re-explaining concepts, creating on-the-spot adaptations, ensuring recording of assignment due dates, clarifying for comprehension, and encouraging participation); (ii) academic outside-of-class support (e.g., assisting with tasks such as staying organized, reviewing class notes, preparing for assessments, clarifying concepts, checking homework deadlines, proofreading assignments, offering editing suggestions, creating study aids like graphic organizers or note cards, highlighting key concepts in texts, and studying together); (iii) support in daily campus life (e.g., helping mentees navigate the campus and manage their finances); (iv) social support (e.g., encouraging involvement in university clubs, organizing activities like pick-up basketball games, sharing meals together, and facilitating introductions to other individuals) (Jones, 2010; Griffin et al., 2016; Workman and Green, 2019).

The literature highlights several benefits of Mentoring Circles, such as expanding social networks, reducing feelings of isolation, increasing commitment, acquiring knowledge, better understanding of academic culture (Darwin and Palmer, 2009), building meaningful relationships (Griffin et al., 2016; Davis, 2019), developing communication skills (Darwin and Palmer, 2009; Cardinot and Flynn, 2022), self-esteem and self-efficacy, reducing stress in adapting to university, better awareness of how to achieve academic success (Cardinot and Flynn, 2022).

3 Purpose of the study

Peer Mentoring Circles is an innovative strategy for developing support networks in Higher Education (e.g., Darwin and Palmer, 2009; Griffin et al., 2016). However, the literature on this support model for students with ID is scarce (e.g., Griffin et al., 2016; Heron et al., 2023).

Both mentees and mentors have a unique perspective from which they can address various aspects of this growing movement—peer mentoring (Carter and McCabe, 2021): e.g., program components, nature of relationships established, functioning of support, and perceived outcomes. Each of these aspects would be challenging to discern in the absence of the perceptions of Circle members.

Therefore, the following guiding research question was formulated:

How were perceived the experiences of the members of Peer Mentoring Circles in the university context?

To operationalize the stated question, the objective is to understand the perspectives of mentees (individuals with ID) and their mentors regarding their participation in Peer Mentoring Circles within a university context.

This study aims to broaden the research lens on Peer Mentoring Circles by capturing the voices of the mentees and their mentors, seeking to understand the perceived experiences regarding support in curricular activities in the university context.

4 Materials and methods

The evidence presented in this qualitative study (Bogdan and Biklen, 2013; Bryman, 2012) is an integral part of a broader investigation framed within a doctoral thesis, aiming to understand the supported participation of persons with ID in university life.

The Higher Education Institution, where the study was conducted, is a public institution located in Portugal. To preserve anonymity, it was assigned the pseudonym “Portuguese University,” acronym UPor.

4.1 Participant recruitment

As part of an inclusive university pilot program, two female individuals with ID attended undergraduate courses (fully included in the university courses), chosen by themselves, during the second semester of the academic year 2018–2019. They were designated as Participant-Students (PS).

The undergraduate courses chosen by Participant-Students, based on Person-Centered Planning (PCP) were:

• TEC - undergraduate course in the scientific area of Technologies, part of the third year of a bachelor’s degree.

• ART - undergraduate course in the scientific area of Arts, part of the second year of a bachelor’s degree.

Both PS were invited to participate in the study, and both agreed. To ensure anonymity, the following codes were assigned:

• PS1 – Participant-Student attending TEC and ART course.

• PS2 - Participant-Student attending ART course.

To provide support in curricular activities inside and outside the classroom, two Peer Mentoring Circles were developed for both PS:

• TEC Circle - Academic support for PS1 in the TEC course.

• ART Circle – Academic support for PS1 and PS2 in the ART course.

Each Circle had a facilitator to oversee the mentoring process and guide the roles of mentors.

For mentor recruitment, at the beginning of the 2018–2019 academic semester, the facilitator, with the consent of the respective faculty, presented the Peer Mentoring Circles program to students in TEC and ART courses, inviting them to voluntarily take on the role of mentors. Seven students, three from TEC (students of a third year of a bachelor’s degree) and four from ART (students of a second year of a bachelor’s degree), accepted the role for one academic semester.

All mentors were invited to participate in this study, and all agreed. To ensure the mentors’ anonymity, the following codes were assigned:

• TEC Mentors - M1_TEC, M2_TEC, M3_TEC.

• ART Mentors - M1_ART, M2_ART, M3_ART, M4_ART.

The Peer Mentoring Circles were composed by:

• TEC Circle (n = 4) - PS1, M1_TEC, M2_TEC, M3_TEC.

• ART Circle (n = 6) - PS1, PS2, M1_ART, M2_ART, M3_ART, M4_ART.

All members of the circle were female and their age range was 19–28.

4.2 Methodological options

The methodological options adopted are qualitative, aiming to capture the essence of the phenomenon (Coutinho, 2011), with a descriptive and interpretative character to understand the processes inherent in peer mentoring.

This study is based on semi-structured individual and/or group interviews with two mentees and seven mentors, as well as the facilitator’s diary (FD) records to explore the perceptions of mentees and their mentors about the mentoring experiences. Interviews were considered the most suitable data collection instrument for mentees due to potential difficulties in responding to questionnaires by persons with ID (Cardinot and Flynn, 2022). Content analysis (Amado, 2013) was the technique adopted for data analysis.

4.3 Data collection procedures

The first step involved obtaining consent from the Institutional Ethics Council. All participants provided written consent, ensuring the anonymity of their testimonies.

Two interview scripts were developed—one for mentees and another for mentors—composed of guiding questions to collect perceptions about their mentoring experiences. The scripts were reviewed and validated by a research specialist.

Before the interview, explicit informed consent was obtained.

Data collection took place between June and October 2019. All interviews were conducted in person, lasted a maximum of about an hour, were digitally recorded, and fully transcribed.

4.4 Data analysis procedures

For data analysis, general procedures outlined by Amado (2013) and Cresswell (2009) were followed. Transcriptions were inserted into the webQDA software for analysis, following Costa and Amado (2018) guidelines.

To ensure research credibility were adopted strategies: triangulation, peer review, and member check (Merriam, 2009).

4.5 Contextualization of the Peer Mentoring Circle program

To identify the support needs of mentees, Person-Centered Planning was used in a meeting with the mentees at the beginning of the 2018–2019 academic year. This study focuses on academic support and the Peer Mentoring Circle model for the provision of this type of support.

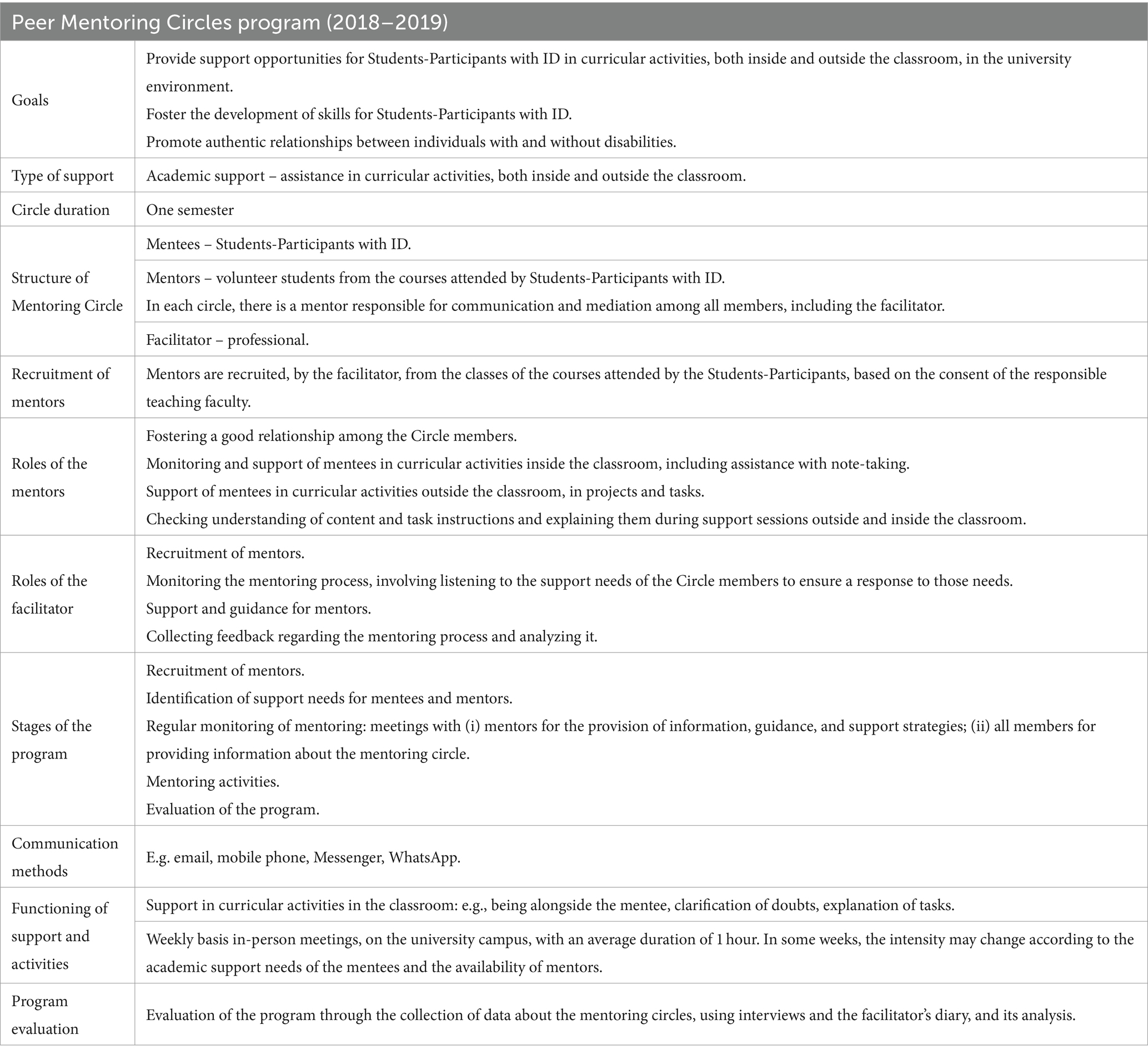

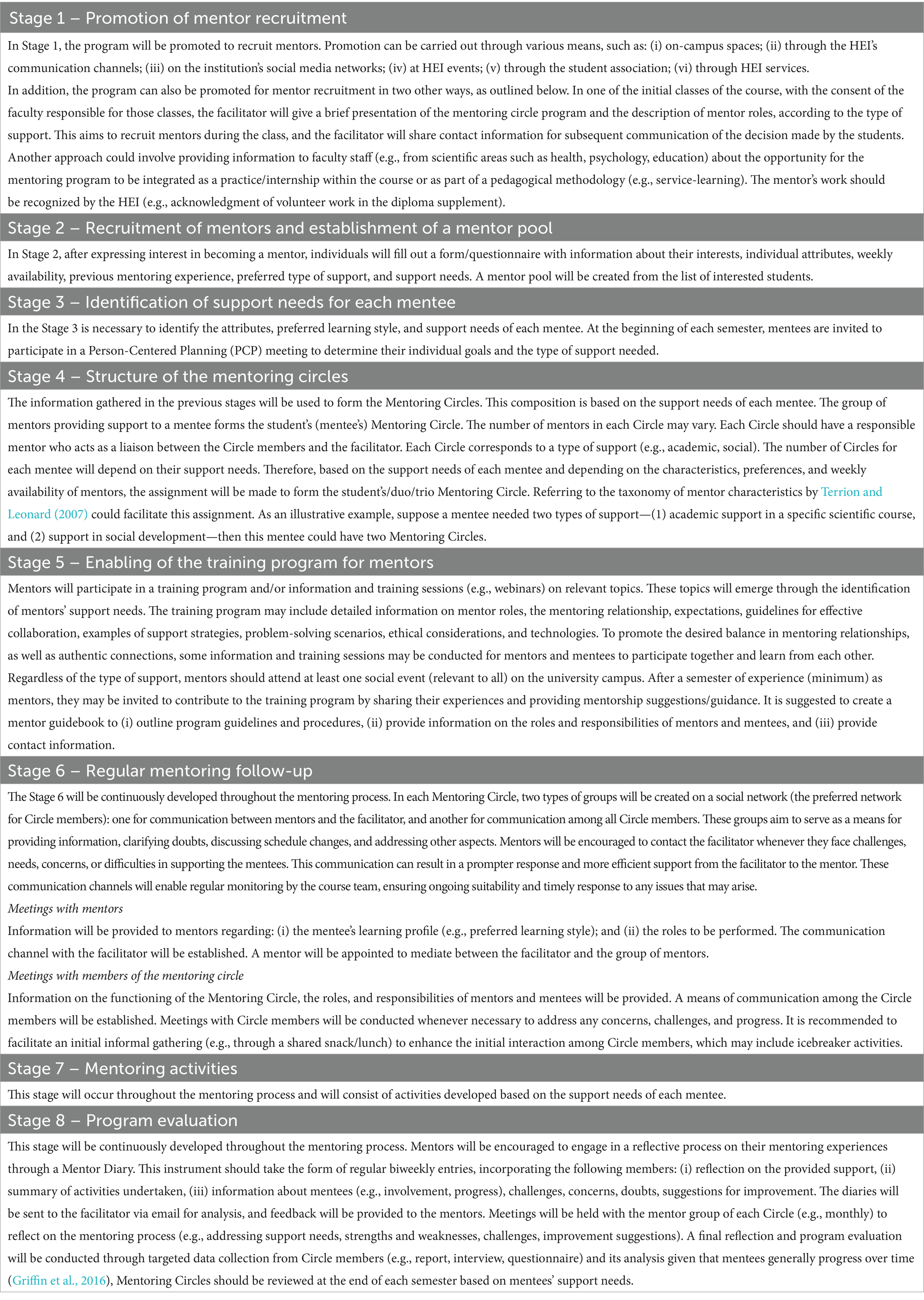

A program was developed to implement this model, with components detailed in Table 1.

The program focused on providing support in curricular activities inside and outside the classroom.

5 Results

The data was generated based on the analysis of the perceptions of two mentees and seven mentors from the two Peer Mentoring Circles – TEC Circle and ART Circle, along with the facilitator’s diary records.

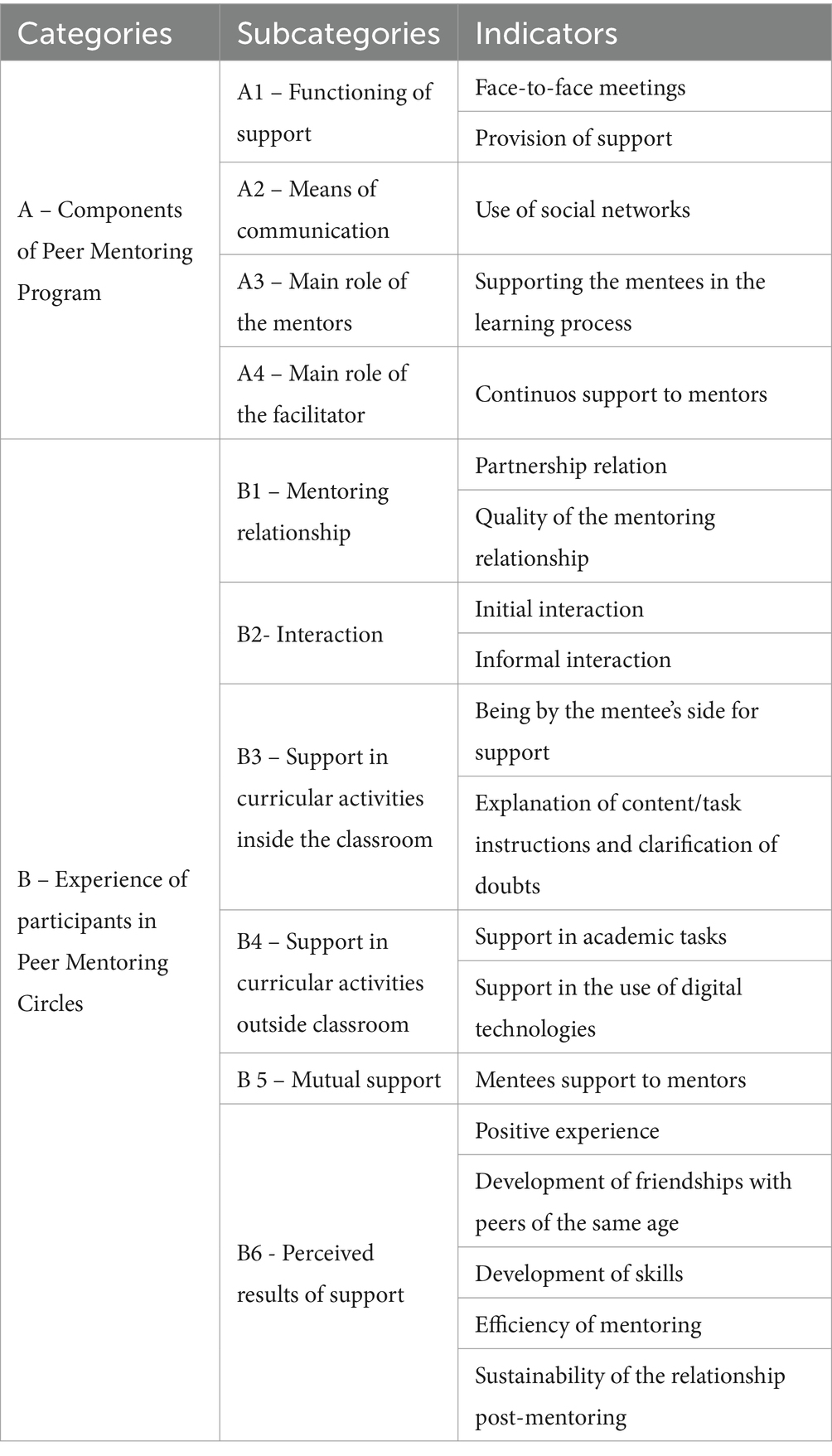

Through the data analysis, two categories emerged:

• A – components of the peer mentoring circle program.

• B – experiences of the members in the peer mentoring circles.

Within category A, four subcategories were found: Support Operation, Communication Medium, Role of Mentors, Role of the Facilitator, and their respective indicators.

The category B was branched into six subcategories: Mentoring Relationship, Interaction, Support in Curricular Activities Inside the Classroom, Support in Curricular Activities Outside the Classroom, Mutual Support, Perceived Results of Support, and their respective indicators.

The Table 2 illustrates the matrix of categories, subcategories, and indicators.

5.1 A – components of the Peer Mentoring Circle program

5.1.1 A1 – functioning of support

5.1.1.1 Face-to-face meetings

The Circles’ meetings were in-person meetings on weekly basis, in the university campus, with an average duration of 1 hour. In some weeks, the frequency could change according to the academic support needs of the mentees and the availability of mentors.

In this context, one mentor reported, “we always tried to have a meeting” (M3_TEC), continuing to state that “we were always with PS1.”

5.1.1.2 Provision of support

Concerning on the provision of support, one mentor from the TEC Circle mentioned, “I do not think a separate support, you already had yours, from your mom, and then ours” (M3_TEC). Her discourse highlights the support provided (i) by the facilitator (who also had the role of a tutor in the project of which this study is a part), (ii) by the mentee’s mother (at home, as mentioned by the mentee herself), and (iii) by the mentors.

5.1.2 A2 – means of communication

5.1.2.1 Use of social networks

Various means of communication were used like as email, mobile phone, Messenger, WhatsApp.

The use of social networks as a communication among the members of the Peer Mentoring Circles was evidenced in the narrative of PS1, saying, “I ended up talking to M3_TEC and M2_TEC on Facebook” (PS1_10_09_19).

5.1.3 A3 – main role of the mentors

5.1.3.1 Supporting mentees in the learning process

Mentors were assigned various roles such as fostering a good relationship among the Circle members, as well as support of mentees in curricular activities inside and outside the classrooms.

In the perception of one mentor, her main role was “I am here to help” (M3_TEC), supporting the mentee. Helping to learn, a mentor of the other Circle said, “we helped her learn” (M3_ART).

5.1.4 A4 – main role of the facilitator

5.1.4.1 Continuous support to mentors

The facilitator had diverse roles such as monitoring the mentoring process, involving listening to the support needs of the Circle members to ensure a response to those needs, support, and guidance for mentors, collecting feedback regarding the mentoring process and analyzing it.

The main role of the facilitator was witnessed by one of the mentors in regarding a continuous support. One mentor said that the facilitator “always made herself available to help us. I think it was the most appropriate. She supported us all the time, she was always willing and supportive” (M1_TEC).

5.2 B – experiences of members in the Peer Mentoring Circles

5.2.1 B1 – mentoring relationship

The partnership relation and the quality of the mentoring relationship are indicators of the mentoring relationship.

5.2.1.1 Partnership relation

The intention was for the Circle members to establish authentic and equal partnerships through mentoring. As noted in the narratives of some mentors from both Circles, treating everyone equally seems to have contributed to the development of a genuine partnership. One mentor indicated, “they [PS1 and PS2] should be treated exactly like anyone else, so I think we always tried that they did not, did not feel left out” (M1_ART). Consistently, a mentor from the other Circle mentioned that it is important to “not be treated like ‘oh poor girl for having this,’ but to be treated the same way” (M3_TEC).

5.2.1.2 Quality of the mentoring relationship

Regarding the TEC Circle, according to PS1, the relationships “were good” (PS1_10_09_19). One of the mentors corroborated by expressing, “the relationship we created with PS1, without a doubt, with PS1” (M2_TEC), was considered good.

One of the mentees from the ART Circle said about her mentors, “I love them” (PS2_eg1). This mentee reinforced at another time, “I like my colleagues. They make me laugh. They are very playful, say a lot of jokes, I like everything” (PS2_27_05_19). Two mentors from this Circle expressed agreement with PS2’s narrative by saying, “I really liked PS2 because she talked a lot, was very dear to us, always wanted to share her food with us” (M3_ART). Another mentor reported that PS2 “always asked if we were okay” (M2_ART).

5.2.2 B2 – interaction

Although interaction occurred throughout the semester in the Peer Mentoring Circles, the narratives emphasized the interaction at the beginning of the semester and the informal interaction experienced outside of mentoring, as evidenced by the extracts presented below.

5.2.2.1 Initial interaction

One mentor said, “at first, it was difficult, but as the conversation unfolded” (M2_TEC), continuing to say that “then the interaction with her became much easier.” Another mentor from the same Circle reported that PS1 was initially more reserved, however, “in the end, she talked about everything and anything” (M3_TEC). This mentor believes that “maybe she was afraid to speak because we could reprove her comments.”

This judgment, although hypothetical, seems to reflect the possibility that PS1 considered a hierarchical mentor-mentee relationship; however, this was not evident. On the other side, as mentioned earlier, evidence of a partnership relationship emerged. According to a mentor from the other Circle, PS1 and PS2 “were a bit shy at the beginning, but I think it’s normal because in the end, they were more comfortable with us” (M3_ART).

5.2.2.2 Informal interaction

PS2 described one of the moments experienced with the mentors during the break of one of the classes, expressing: “first, we went to have a coffee, then we went to the ATM, and then we went to buy chewing gum for a girl who was sick, but there were no chewing gums. Then we went back to the room” (PS2_27_05_19).

5.2.3 B3 – support in curricular activities inside the classroom

Concerning support in curricular activities inside the classroom, evidence related to the roles had by the mentors emerged, which is quoted below.

5.2.3.1 Being by the mentee’s side to support

Regarding the support provided in the classroom, one of the mentors indicated, “I am by her side to support her, for whatever she wants” (M3_TEC).

5.2.3.2 Explanation of content/task instructions and clarification of doubts

Throughout the semester, the facilitator had the opportunity to observe the support provided by the mentors inside the classroom of the ART course. In some classes, the facilitator observed the mentors’ answering questions from the mentees; in other classes, she noticed the mentor’s providing information and explaining resources of the course to the mentees (e.g., FD_Apr19; FD_May19). In one class, the facilitator observed one of the mentors explaining to the mentees how to synthesize the text Homero by Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen for use in the theatrical piece (FD_May19).

In this scope, PS1 shared that: “I was talking to M3_TEC and talking to M2_TEC and M1_TEC, looking for a way to get the work done and also to present it” (PS1_10_09_19).

5.2.4 B4 – support in curricular activities outside the classroom

The support provided by the mentors in curricular activities outside the classroom was evident in the narratives of both mentees and mentors.

5.2.4.1 Support in academic tasks

The narrative of PS1 revealed support in academic tasks when she mentioned, “I joined them to talk about children,” adding in her speech, “I had the conversation with M3_TEC and talked to M2_TEC and M1_TEC, figuring out a way to do the work to present it too” (PS1_10_09_19).

At another time, PS1 said, “I would agree with M3_TEC and M2_TEC, talking about the work” (PS1_eg2).

5.2.4.2 Support in the use of digital technologies

Support in the use of digital technologies was evident in a mentor’s account when she indicated, “one of us would always stay to help her with the computer” (M2_TEC).

5.2.5 B5 – mutual support

5.2.5.1 Mentee’s support to mentors

In the mentoring circles, in addition to the support from mentors to mentees, there was also support from mentees to mentors, as revealed in the following quoted excerpts. PS1 said, “I also calmed down the colleagues who were always a bit nervous, helped them” (PS1_10_09_19). This testimonial was corroborated by two mentors, as seen in the speech of M1_TEC when mentioning that “in the end, she was always ‘calm, calm, it will go well,’“and in the narrative of M3_TEC when she said, “she was the one who calmed us in those situations,” particularly before oral presentations in class. Another mentor from the same Circle also mentioned, “all the help she gave us” (M2_TEC).

5.2.6 B6 – perceived results of the support

There is evidence regarding the outcomes of the support provided by the mentors to the mentees.

5.2.6.1 Positive experience

The narratives reflect that the Mentoring Circle experience was positive for both: the mentees and the mentors.

One mentor affirmed, “PS1 was almost always happy, and it’s very good to see that” (M2_TEC). In turn, PS1 shared, “since I met M3_TEC and the others, it has been the best experience of my life” (PS1_eg1).

One of the mentors TEC Circle revealed that “it was a new life experience that I had” and “it was very enriching; I loved this experience” (M3_TEC).

One mentor of the ART Circle said that “it’s a good experience for them as much as it is for us” (M2_ART). These testimonies suggest positive feelings regarding the role played as mentors.

5.2.6.2 Development of friendships with peers of the same age

In a broad set of discourses, there is evidence of the development of a friendship relationship among the members of the mentoring circles. PS1 said, “I made friends” (PS1_10_09_19). When asked again, the same mentee reinforced, “since I met them [mentors], they are in my heart” (PS1_eg1).

The perceptions of the mentors corroborate this, indicating that “she could have friends her age,” and she gradually felt at ease with these new friends, as “she came to us and shared her news” (M1_TEC). Specifically, “she told us about her work and having a boyfriend she likes a lot and all the conversations she had with us and that we had with her” (M2_TEC). The same mentor said that created “a very good friendship” with PS1.

5.2.6.3 Development of skills

There is evidence of the development of mentees’ skills, particularly in communication and increased self-confidence. One mentor mentioned that the mentees improved “communication with other people” (M3_ART). One of the mentors of other Circle stated in relation to PS1 that “I think she has evolved a lot in being in front of an audience and talking” (M1_TEC). The same mentor reiterated that “she gained public speaking skills, I think that was all positive points for PS1.”

In this context, PS1 shared that she felt “more confident” (PS1_10_09_19).

5.2.6.4 Efficiency of mentoring

There is evidence indicating the efficiency of mentoring. One mentor testified, “I think we managed” (M1_TEC) to support PS1 in curricular activities. Another mentor from the same Circle reported on the progress of the mentee, saying, “her process was noticeable” (M2_TEC). Recognizing the mentoring as a process in evolution, PS1 mentioned that it was a process “gradually, over time” (PS1_eg2). In a final comment on the mentoring process, the other mentee affirmed, “I did it” (PS2_25_03_19).

• Continuity of the relationship after mentoring.

• Sustainability of the relationship post-mentoring.

There are obvious signs of the continuity of the relationship developed after the Mentoring Circle ended at the end of the semester. One mentor from the ART Circle shared that one of the mentees “always says hello to me when she meets me,” adding that “recently I met her, and she said hello, she talked to me” (M2_ART). The narrative of a mentor from the other Circle corroborated the continuity of the relationship, saying, “it was good because besides being classmates, she is a friend that we will take for life, as she has already told us” (M3_TEC). This student further emphasized in her speech that PS1 “now sees us on the street, and it’s a party.”

6 Discussion

The literature shows that the Peer Mentoring Circles model is a way to assist students with support needs through peers. The group of mentors providing support forms the Mentoring Circles. Each circle corresponds to a specific type of support and may have a variable number of mentors. In turn, the number of circles depends on the support needs of the mentee.

To understand the perceptions of mentees and their mentors about the experiences in the Mentoring Circles, two categories emerged: components of the Mentoring Circles program and experiences of the Mentoring Circles.

The generated data show evidence of the main components of a mentoring program in Higher Education, such as the functioning of support, means of communication, and the roles of mentors and the facilitator.

The perceived experiences within the Mentoring Circles were branched into mentoring relationship, interaction, support in curricular activities both inside and outside the classroom, mutual support, and perceived outcomes of the support provided by mentors.

It is observed that the Circles were homogeneous as their members were all female. However, the classes they belonged to were also predominantly composed of female students. The systematic review conducted by Carter and McCabe (2021) revealed that among 2,670 mentors, the majority were female. In this context, Griffin et al.’s (2016) study showed a reduced number of male students volunteering for the mentor role. Since this study focused on academic support, it seems that gender was not a significant characteristic of the mentor that influenced the outcomes, as no references to this data emerged. However, this characteristic may become a challenge in mentoring, as mentioned by Terrion and Leonard (2007). For example, if a male student (mentee) requires support in daily campus activities, it may need a mentor of the same gender to assist (e.g., accompanying to the restroom). In such cases, having male volunteers may be essential to assign mentors of the same gender.

It is noted that one of the means of communication used by a mentee was Messenger. This data seems to be related to the expansion of her social networks, as the use of this platform can contribute to the continuation of social interactions between former mentors and mentees.

The perceived experiences of the Circle members included the mentoring relationship. In this context, it appears that the developed partnership may be due to recognizing Circle members as individuals with similar interests and/or goals, equalizing the relationship and promoting a natural partnership, as shown by the generated data. These findings are consistent with the results of studies by Jones and Goble (2012) and Krech-Bowles and Becht (2022).

The facilitator, in the initial meeting with the mentors, by providing information about the learning profiles and individual attributes of the mentees, as well as support strategies, may have led the mentors to become familiar with some of the characteristics of the mentees, which may have contributed to the good relationship developed by the Circle members. Kelley and Westling’s (2013) study emphasize this correlation, highlighting the importance of mentors being informed about the people they will support from the beginning of the process.

The generated data suggest that the initial interaction may have been a challenge for the Circle members because one of the mentees appeared reserved, and, on the other hand, one of the mentors thought she might fear reprimands. This assumption may be due to the mentee’s nervousness, as well as the mentor’s lack of knowledge of how to “break the ice.” However, it is evident from the perceived experiences that this situation only occurred at the beginning of the mentoring process. Thus, to facilitate the initial interaction, the study by Workman and Green (2019) recommends organizing an informal initial meeting so that mentees can get to know their mentors. This meeting can promote “ice-breaking” activities, as well as an opportunity for exchanging information (e.g., contacts) among Circle members.

Kelley and Westling (2013) mention that many mentors start mentoring with some hesitation, but over time, the majority express satisfaction in interacting with mentees, finding more similarities than differences. Spontaneous and natural interaction observed between a mentee and her mentors, occurring informally outside mentoring, can act as a catalyst for promoting a more significant partnership.

The generated data highlight support in curricular activities both inside and outside the classroom. The perceptions of the Circle members emphasize the reciprocity in the mentor-mentee relationship through mutual support, in line with the findings of the study by Rillotta et al. (2022). The mentees’ support for the mentors may have contributed to the partnership relationship, where they helped each other, regardless of their roles.

In this study, mentoring appears to be a positive experience for all members of both mentoring Circles, in accordance with the results of studies by Kelley and Westling (2013) and Rillotta et al. (2020, 2022).

Perceived outcomes of support include some of the mentoring benefits mentioned in the literature (e.g., Griffin et al., 2016; Cardinot and Flynn, 2022), such as relationship and skill development.

These demonstrated benefits may have facilitated the authentic inclusion of mentees in university life.

The generated data reveal that mentoring Circles support the development of communication skills, as corroborated by the results of studies by Cardinot and Flynn (2022), Felton-Busch et al. (2013), and Rillotta et al. (2020) and self-confidence in line with the mentoring base mentioned by Klamma et al. (2022).

Data analysis evidenced the development of friendships among Circle members, in line with the results of studies by Kelley and Westling (2013) and Griffin et al. (2016). The mentees had the opportunity for regular interaction, during an academic semester, with peers of the same age who guided them. It seems that this interaction contributed to the development of friendships, as perceived through their experiences.

With evidence of the efficiency of the support, it is believed that the mentoring Circles program is an effective way to address the diverse needs of university students with and without disabilities.

Overall, the generated data seem to converge both within and between the two mentoring Circles. Through the perceived experiences of Circle members, it appears that a “space” was created where authenticity, reciprocity, and empathy served as a foundation for creating friendships and their continuation after the conclusion of mentoring.

The generated data indicate that the Peer Mentoring Circles contributed to the development of mentees’ skills, as well as the formation of friendships that are expected to endure beyond mentoring. However, it is noted that the perceived challenge in the experienced mentoring process was in the initial interactions. Thus, it is recommended to initiate the Circles with an informal meeting involving “ice-breaking” activities to facilitate interaction among the members.

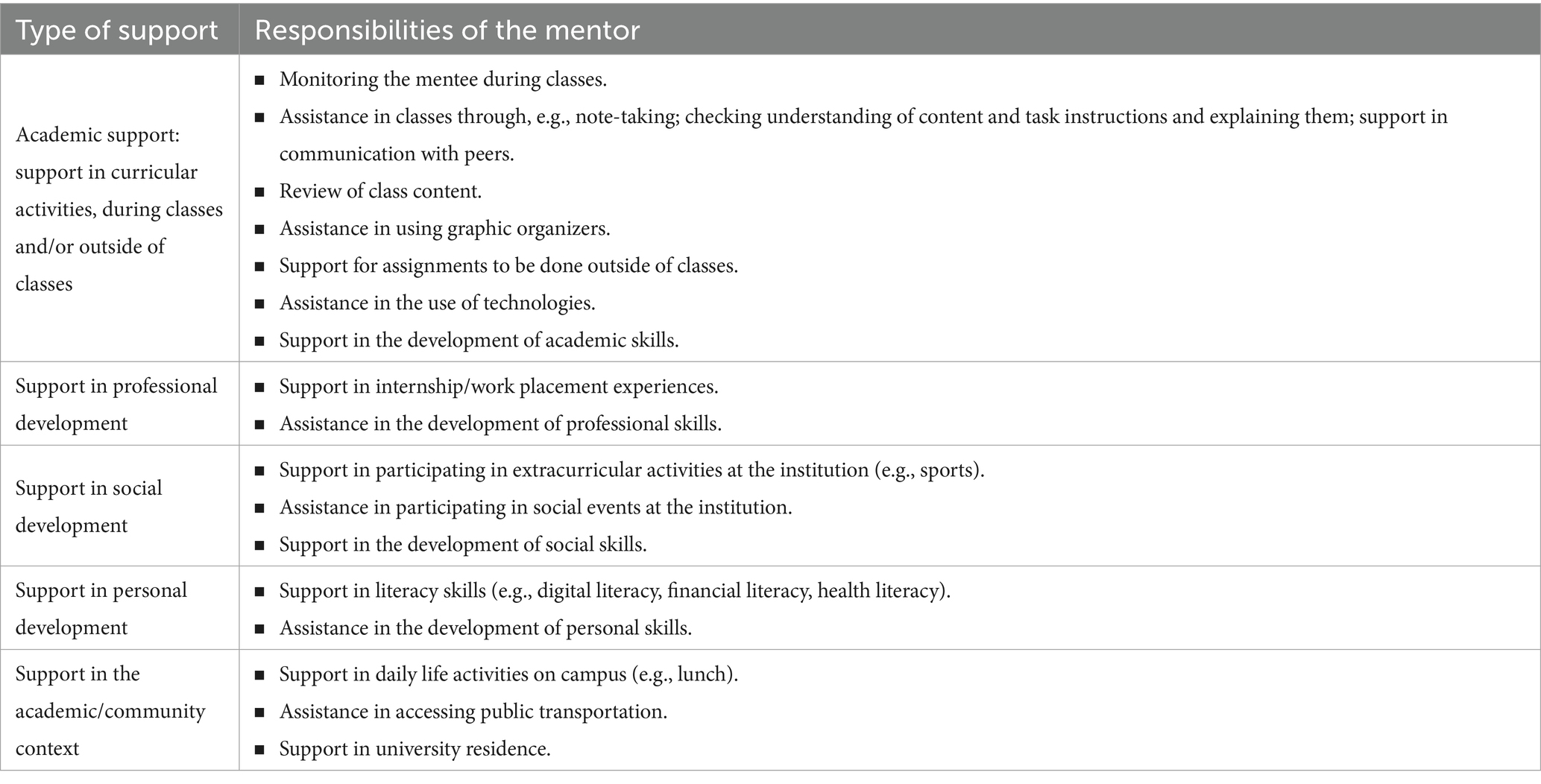

The main aim of this Peer Circle Mentoring was academic support. However, other suppots can be provided by peer mentors such as support in (i) professional development; (ii) social development; (iii) personal development; (iv) the academic/community context. These mentor responsibilities are detailed in the Table 3.

While this study offers insights, it does have limitations. The small number of peer mentors and mentees, as well as their gender homogeneity, along with the specific nature of the HEI where the study was conducted, limit the generalizability of the findings. However, despite these constraints, the study underscores the positive experiences associated with peer mentoring and suggests potential benefits that could inform future research and program implementation in other HEIs. Thus, it is believed that there is a feasibility of transferability in the sense of transferring the knowledge constructed to other academic contexts.

This article focused on the perceived outcomes of the support provided by mentors (and not on the effects on the mentors themselves), with potential implications for the inclusion of students with ID in HEIs, an area in need of development.

However, future research could focus on understanding the effects (immediate and longitudinal) on Mentoring Circles’ members. It would be important to analyze the friendships that develop from mentoring relationships and investigate if these relationships persist over time. Additionally, research could explore whether mentoring influences the professional paths of former mentors, clarifying its impact.

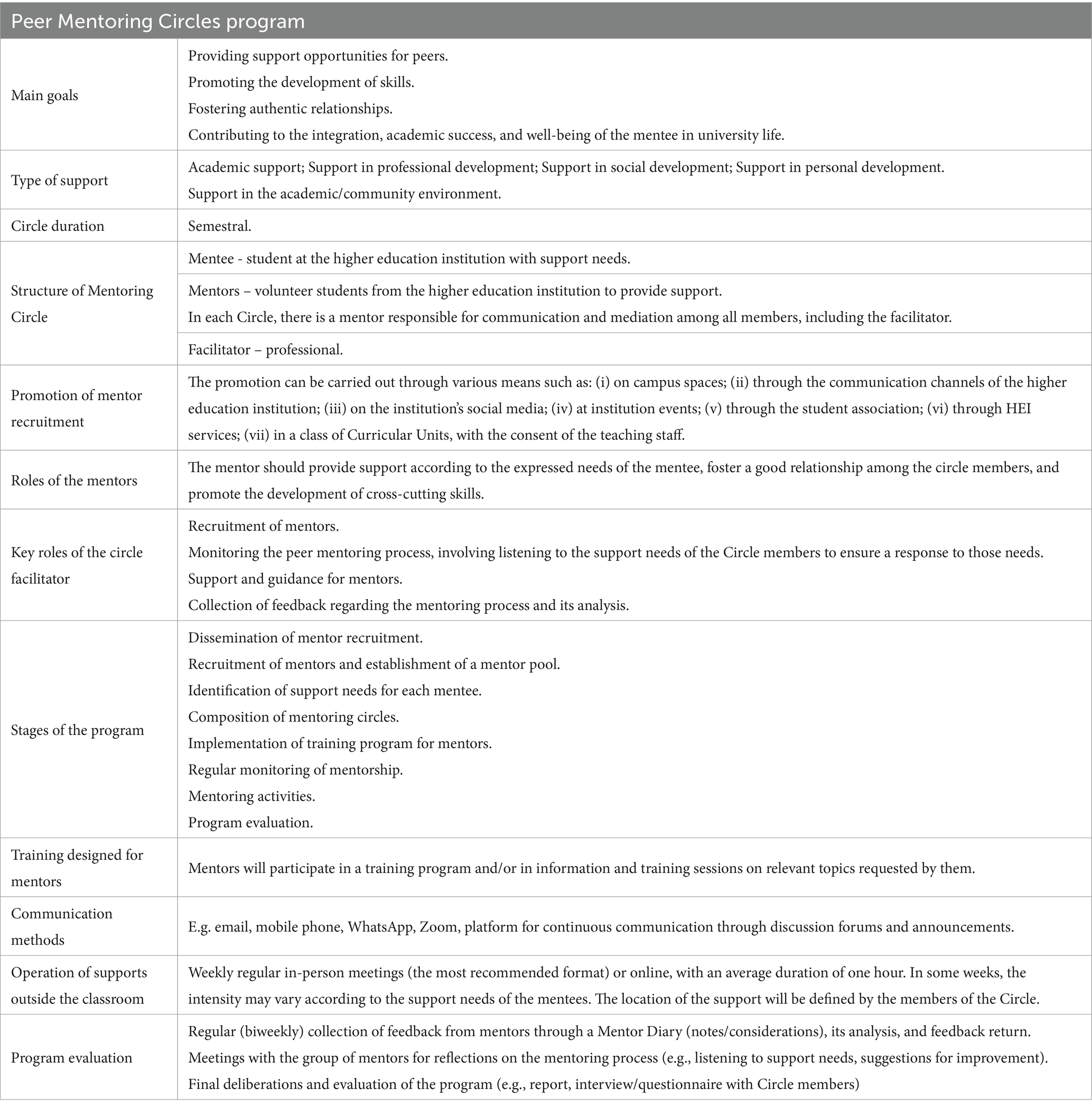

Based on the correlation between the generated data and the literature contributions mentioned in the theoretical context (e.g., Jones and Goble, 2012; Kelley and Westling, 2013; Griffin et al., 2016; Workman and Green, 2019; Krech-Bowles and Becht, 2022), the proposal of the Peer Mentoring Circles program emerges, its components, and stages are detailed in the Tables 4, 5.

7 Conclusion

The number of students with disabilities, including those with intellectual disability, has been increasing in Higher Education. However, merely opening the doors of Higher Education Institutions is not sufficient, as the literature indicates the need to provide support for their academic success. In this regard, peers can have a crucial role in the inclusion and learning of these students in the university context.

Peer Mentoring Circle is one support mechanism that can give to students with ID the opportunity to receive guidance from their peers.

The data from this study suggests that have benefits for the mentees and the experiences of the Mentoring Circles were positive, not only for mentees, but also for mentors.

The benefits for the mentees were emerged in the narratives such as the development of skills and friendships.

From a logistical perspective, according to Griffin et al. (2016), most inclusive university programs for this population have limited capacity in terms of personnel and funding, making volunteer mentors even more valuable. With the commitment of student volunteers, this model reduces the amount of formal support needed from university services, which already have an extensive workload. Additionally, this model facilitates the authentic inclusion of students with disabilities in university life, as mentees not only met for curricular support but also socialized outside mentoring.

The experiences and perspectives shared by the members of the Circles in this study are valuable because there have been few other studies conducted till the present date. The experiences of these members can be used to inform the development of mentoring programs work in IHEs to support students with ID in universities through undergraduate peer mentors.

It is advocated to invest in the transfer and expansion of the Peer Mentoring Circles program proposal to other HEIs, catering not only to students with disability but also to those with other support needs, such as international students.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: http://hdl.handle.net/10773/34952.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics and Deontology Committee of the University of Aveiro. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was also provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

MM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ME-S: Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work is financially supported by National Funds through FCT -Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under the project UIDB/00194/2020 and by Research Centre on Didactics and Technology in the Education of Trainers (CIDTFF).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all the persons who participated in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

AAIDD (2024). Definining criteria for intellectual disability. Available at: https://aaidd.org/intellectual-disability/definition

Amado, J. (2013). Manual de Investigação Qualitativa em Educação. Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra.

Araten-Bergman, T., and Bigby, C. (2022). Forming and supporting circles of support for people with intellectual disabilities – a comparative case analysis. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 47, 177–189. doi: 10.3109/13668250.2021.1961049

Athamanah, L. S., Fisher, M. H., Sung, C., and Han, J. E. (2020). The experiences and perceptions of college peer mentors interacting with students with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Dis. 45, 271–287. doi: 10.1177/1540796920953826

Bogdan, R. C., and Biklen, S. K. (2013). Investigação Qualitativa em Educação. Portugal: Porto Editora.

Bussu, A., and Burton, S. (2023). Higher education peer mentoring programme to promote student community building using Mobile device applications. Group 30, 53–71. doi: 10.1921/gpwk.v30i2.1636

Cardinot, A., and Flynn, P. (2022). Rapid evidence assessment: mentoring interventions for/by students with disabilities at third-level education. Educ. Sci. 12:384. doi: 10.3390/educsci12060384

Carter, E. W., Gustafson, J. R., Mackay, M. M., Martin, K. P., Parsley, M. V., Graves, J., et al. (2019). Motivations and Expectations of Peer Mentors Within Inclusive Higher Education Programs for Students With Intellectual Disability. Career Development and Transition for Exceptional Individuals, 42, 168–178. doi: 10.1177/2165143418779989

Carter, E. W., and McCabe, L. (2021). Perspectives of peers within the inclusive postsecondary education movement: a systematic review. Behav. Modif. 45, 215–250. doi: 10.1177/0145445520979789

Coutinho, C. P. (2011). Metodologia de Investigação em Ciências Sociais e Humanas: teoria e prática. Coimbra: Edições Almedina.

Cresswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Crisp, G., and Cruz, I. (2009). Mentoring college students: a critical review of the literature between 1990 and 2007. Res. High. Educ. 50, 525–545. doi: 10.1007/s11162-009-9130-2

Davis, B. M. (2019). Peer Mentor circles to support international graduate students: a potential solution. Available at: https://newprairiepress.org/aerc/2019/roundtables/7

Darwin, A., and Palmer, E. (2009). ‘Mentoring circles in higher education’, Higher Education Research & Development. 28, 125–136. doi: 10.1080/07294360902725017

Felton-Busch, C., Maza, K., Ghee, M., Mills, F., Mills, J., Hitchins, M., et al. (2013). Using mentoring circles to support aboriginal and Torres Strait islander nursing students: guidelines for sharing and learning. Contemp. Nurse 46, 135–138. doi: 10.5172/conu.2013.46.1.135

Griffin, M., Wendel, K., Day, T., and McMillan, E. (2016). Developing peer supports for college students with intellectual and developmental disabilities. J. Postsec. Educ. Dis. 29, 263–269,

Heron, L. M., Agarwal, R., and Burke, S. L. (2023). Mentoring postsecondary students with intellectual disabilities: faculty and staff Mentor perspectives. Educ. Sci. 13:213. doi: 10.3390/educsci13020213

Jones, M. M. (2010). Creating mentoring partnerships. Northern Kentucky University. Available at: https://thinkcollege.net/sites/default/files/files/resources/Creating%20Mentoring%20PartnershipsNorthernKentucky.pdf

Jones, M. M., Boyle, M., May, C. P., Prohn, S., Updike, J., and Wheeler, C. (2015). Building inclusive campus communities: a framework for inclusion. Boston, MA: Think College Insight Brief.

Jones, M. M., and Goble, Z. (2012). Creating effective mentoring partnerships for students with intellectual disabilities on campus. J. Policy Pract. Intellect. Disabil. 9, 270–278. doi: 10.1111/jppi.12010

Kelley, K. R., and Westling, D. L. (2013). A focus on natural supports in postsecondary education for students with intellectual disabilities at Western Carolina University. J. Vocat. Rehabil. 38, 67–76. doi: 10.3233/JVR-120621

Klamma, R., Kravčík, M., Pammer-Schindler, V., and Popescu, E. (2022). Editorial: intelligence support for mentoring processes in higher education (and beyond). Front. Artif. Intell. 5:935020. doi: 10.3389/frai.2022.935020

Krech-Bowles, L., and Becht, K. (2022). Mentor models and practices for inclusive postsecondary education. Boston: Institute for Community Inclusion, University of Massachusetts.

Lewis, C. (2017). Creating inclusive campus communities: the vital role of peer mentorship in inclusive higher education. Metrop. Univ. 28:3. doi: 10.18060/21540

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research: a guide to design and implementation. Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass.

Rillotta, F., Arthur, J., Hutchinson, C., and Raghavendra, P. (2020). Inclusive university experience in Australia: perspectives of students with intellectual disability and their mentors. J. Intellect. Disabil. 24, 102–117. doi: 10.1177/1744629518769421

Rillotta, F., Gobec, C., and Gibson-Pope, C. (2022). Experiences of mentoring university students with an intellectual disability as part of a practicum placement. Mentor. Tutor. 30, 333–354. doi: 10.1080/13611267.2022.2070991

Rooney-Kron, M., Regester, A., Lidgus, J., Worth, C., Bumble, J. L., and Athamanah, L. S. (2022). A conceptual framework for enabling risk in inclusive postsecondary education programs. Incl. Pract. 1, 114–123. doi: 10.1177/27324745221078599

Terrion, J. L., and Leonard, D. (2007). A taxonomy of the characteristics of student peer mentors in higher education: findings from a literature review. Mentor. Tutor. 15, 149–164. doi: 10.1080/13611260601086311

United Nations (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Int. Eur. Labour Law 14, 1–28. doi: 10.5771/9783845266190-471

United Nations (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf

Wilt, C. L., and Morningstar, M. E. (2020). Student perspectives on peer mentoring in an inclusive postsecondary education context. J. Incl. Postsec. Educ. 2:1. doi: 10.13021/jipe.2020.2461

Keywords: higher education, inclusive higher education, peer mentoring circle, mentoring, intellectual disability

Citation: Maia M, Santos P and Espe-Sherwind M (2024) Peer Mentoring Circles in higher education: perceptions of their members with and without disability and program proposal. Front. Educ. 9:1362752. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1362752

Edited by:

Huichao Xie, University College Dublin, IrelandReviewed by:

Lorella Terzi, University of Roehampton London, United KingdomMarco Ferreira, Higher Institute of Education and Science (ISEC), Portugal

Copyright © 2024 Maia, Santos and Espe-Sherwind. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marisa Maia, bWFtbUB1YS5wdA==

Marisa Maia

Marisa Maia Paula Santos1

Paula Santos1 Marilyn Espe-Sherwind

Marilyn Espe-Sherwind