- Department of Pedagogy and Primary Education, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece

Introduction: Since the mid-20th century, the number of adult students enrolled in formal higher education (HE) programs has significantly increased. The profile of non-traditional students differs significantly from that of traditional students in terms of their characteristics, learning methods, obstacles and challenges, motivations for learning, and conditions for effective learning. Unlike traditional students, adult students often balance family, work, and educational responsibilities, necessitating a more nuanced approach to support and guidance. However, most HE institutions primarily serve the needs of traditional student populations, which results in limited support available to adult students. This scoping review aimed to explore and map the existing literature on the role of adult (or non-traditional) students counseling in the context of formal HE.

Methods: We focused on literature related to academic advising for non-traditional students in formal HE, restricting our search to both empirical and non-empirical articles published in peer-reviewed journals between 2010 and 2022. Employing Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping review method and the PRISMA-ScR Checklist, we searched four databases (EBSCOhost, Crossref, Semantic Scholar, and ERIC), supplemented by a manual search.

Results: Of the 1,330 articles identified and screened, 25 studies met the eligibility criteria. Our review included 17 empirical and eight non-empirical studies, with the majority conducted in the USA (21 of 25). Thematic analysis revealed five key research areas (or themes): academic advising practices, perceptions of advising, technology, and advising, advising models, and academic success. The most common research theme, advising practices for adult (undergraduate and doctoral) students, constituted 52% of the studies (n = 13).

Discussion: Drawing from our analysis, we discuss current trends and future development in advising non-traditional students within formal HE settings. The added value of academic advising for adult students is explored, and any potential gaps in research literature knowledge are identified.

1 Introduction

Higher education (HE) is constantly changing and has undergone notable transformations in recent decades (Deardorff et al., 2021). Globally, since the mid-20th century, there has been a significant increase in the number of students enrolled in HE, which has brought substantial benefits to societies but has also created new challenges (Calderon, 2018). Additionally, the participation of women and older students in HE has increased (National Center for Education Statistics, 2021; OECD, 2021).

The idea of an “adult student” began to gain prominence in the early 20th century (Lindeman, 1926). This is especially true in the USA and Europe, where scholars and practitioners have begun to examine the unique characteristics, needs, and motivations of adults engaged in learning. According to data from the NCES (Anderson, 2016), the characteristics of students in HE in the USA have changed significantly since 2006. In 2017, the percentage of nontraditional students in public 4-year HE institutions ranged from 10% to 42%, whereas the corresponding percentage in private institutions ranged from 13% to 81%. Additionally, there was an 11% increase in new enrollment of non-traditional students between 2006 and 2016 (McFarland et al., 2019), and it is projected that the number of non-traditional students will further increase to 14 million by 2024 (Snyder et al., 2018).

No readily available and consistent time-series data on adult learning participation across European Union (EU) countries exist. Three European surveys provide the most reliable sources for cross-country comparisons over time (OECD, 2020): (1) the European Adult Education Survey (AES), (2) the European Union Labour Force Survey (LFS) and (3) the Continuing Vocational Training Survey (CVTS). The AES and CVTS data analysis revealed a significant increase in adult learning involvement over the last 15 years. In contrast, the LFS data suggest a modest increase. Various factors, including differences in reference periods, reference populations, and definitions of adult learning, can explain these divergent results. In almost all countries with available statistics, adult student participation rates (in formal and/or informal education and training) have increased between 2007 and 2016.

Over the decades, as adult education has evolved, various terms have been used to describe adults in learning settings, such as mature students, non-traditional students, post-traditional students, etc. The term non-traditional student was initially coined by Cross (1981) to describe the diverse population of adult students who differed from traditional students as they returned to education while maintaining family and work responsibilities. Non-traditional or post-traditional students encompass a diverse group typically aged 25 and above, though also including younger learners who exhibit adult responsibilities like self-support, family care, and full-time employment (Merriam and Baumgartner, 2020). This population may have delayed entry into HE, financial independence, non-traditional educational trajectories, or other adult obligations such as caring for dependents or being a single parent (Soares, 2013; Chen, 2017). These definitions highlight the varied life experiences and responsibilities within the adult student population, emphasizing the broad spectrum of individuals navigating HE.

The profiles of adult non-traditional students differ significantly from those of traditional students in terms of characteristics, learning methods, obstacles, challenges, motivations for learning, and conditions for effective learning. These students typically have unique needs, challenges, and aspirations in HE, which can be outlined as follows:

1. Diverse learning needs: adult learners possess varying educational backgrounds and life experiences, necessitating flexible learning opportunities, personalized instruction, and recognition of prior knowledge (Merriam and Brockett, 2007).

2. Balancing multiple responsibilities: many adult learners manage work, family, and community commitments, requiring support systems and flexible scheduling options to allocate time for learning (Fairchild, 2003).

3. Career advancement and skill development: adult students often pursue education to enhance career prospects, acquire new skills, or transition to new fields, emphasizing aspirations for professional development (Hiemstra and Sisco, 1990).

4. Social justice and equity: some adult learners encounter systemic barriers related to socio-economic status, race, or ability, necessitating attention to issues of social justice, equity, and inclusivity (Matus-Grossman and Gooden, 2002).

5. Technology integration: with digital learning becoming prevalent, adult learners may require support for digital literacy and accessible technology, considering varying levels of technological proficiency (van Rhijn et al., 2015).

6. Support for non-traditional pathways: adult students may follow non-traditional pathways to education, such as returning after a hiatus or balancing education with work and family commitments, highlighting the importance of recognizing and supporting diverse learning journeys (Ross-Gordon et al., 2017).

However, most HE institutions manage study programs designed for the traditional student population, which limits the support available to adult students. Questions arising from this new educational reality concern the interactions between adult students and tertiary educational institutions for their smooth integration and optimal response to HE, and how advisors should adapt and respond to these new challenges. Adult education and HE are interconnected but distinct fields, each with its own established boundaries that uphold disciplinary uniqueness, values, and epistemologies (Hill et al., 2023). These boundaries not only define professional identity but also foster disciplinary cohesion. In adult education, values such as cultural custodianship, practical knowledge, spiritual interconnectedness, individual/group growth, social reconstruction, and scientific scholarship are emphasized. Conversely, HE often adopts a systemic and administrative approach, concentrating on individual learning experiences. The concept of adulthood within adult education acknowledges the multifaceted roles that adults undertake, leading to a more nuanced and intricate understanding. As the relationship between adult education and HE evolves, the boundaries between these fields become more flexible, reflecting the complexity of contemporary educational landscapes.

As formal HE continues to adapt to changing demographics and educational needs, there is a growing recognition of the importance of counseling tailored specifically to adult students. Unlike traditional students, adult students often balance family, work, and educational responsibilities, necessitating a more nuanced approach to support and guidance. Counseling focused on adult students’ needs in formal HE is essential to address the diverse challenges and opportunities faced by this demographic, ultimately fostering their academic success, personal growth, and overall wellbeing. It is important for advisors to understand adult students’ needs, educational preferences, and work and family obligations to provide them with specific resources to support the continuation and successful completion of their studies. Such initiatives would not only enhance the academic experience and success of adult students but also contribute to broader societal advancement through increased access and inclusivity in formal HE.

In international literature, there is increasing interest in research focusing on access to HE, student persistence, and the graduation of historically underrepresented groups, commonly referred to as non-traditional students (Holmegaard et al., 2017). Despite the recognized global need for initiatives that aim to widen participation and increase diversity among students in HE institutions (Bowes et al., 2013), the available literature on the role of professionals supporting the continuously changing student population is limited (Gazeley et al., 2019), and there is a lack of comprehensive reviews that systematically categorize studies in this research field.

Consequently, there is a need to conduct a literature review on counseling non-traditional HE students to provide researchers and practitioners with insights into the most recent advancements, knowledge, experiences, best practices, and research areas in the field. Therefore, this study employs a scoping review approach to provide a broad and comprehensive overview of the existing evidence rather than conducting a detailed quantitative or qualitative data analysis (Peters et al., 2021). A scoping review aims to identify and map the available literature, explore various characteristics or concepts, and present a comprehensive understanding of the research landscape. This approach allows researchers to examine a wide range of sources without necessarily assessing methodological quality or bias. To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first scoping review to focus on advising non-traditional students within the formal HE context.

2 Materials and methods

The current study employed a scoping review methodology and utilized the five-stage framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005): (1) defining the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) selecting studies; (4) extracting, mapping, and charting the data; and (5) synthesizing, summarizing, and reporting the results.

2.1 Stage 1: defining the research question

The scoping review was guided by the following research questions (RQs):

1. What trends are observed in counseling non-traditional students in formal HE?

2. What are the main areas of research and outcomes revealed by the studies on counseling nontraditional students in formal HE?

The primary objective of the first question was to offer a comprehensive overview and analysis of the trends in counseling nontraditional students in formal HE. This includes providing specific information, such as author details, publication year, country location, subject disciplines, research methodology, study design, and participants. In doing so, we aimed to create a detailed field map.

The second research question sought to summarize and disseminate the various approaches and results related to counseling nontraditional students in formal HE. This review aims to provide a concise understanding of the diverse perspectives and findings of the studies discussed.

2.2 Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

Search terms were formulated and classified into three dimensions aligned with the purpose of the review. One dimension focused on counseling, specifying the activity under investigation; the second dimension was related to HE, while the third dimension focused on nontraditional students, identifying the participants involved in the activity. This categorization aimed to narrow the search within the field of nontraditional students. Each search term was connected using the Boolean OR operator, and each dimension was connected using the Boolean AND operator, as detailed in Table 1. Different institutions use terms such as advising, counseling, advisors, and counselors to refer to various functions and individuals. Although the mixture of advising and counseling terms may imply a lack of clear distinctions, there appears to be a continuum of responsibilities across these roles (Kuhn et al., 2006). In our review, we used these terms interchangeably. Similarly, in the current study context, we employed the terms “adult students” and “non-traditional students” interchangeably.

The purpose of this review guided the development of the inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in Table 2. In alignment with previous research, this review focused on literature on counseling adult students in HE published within the last 12 years, starting in 2010 (Henschke, 2012). The criteria included selecting peer-reviewed articles and prioritizing studies conducted in English, including empirically driven research and theoretical papers (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005; Munn et al., 2018). Empirical articles must have a clear methodological approach to data collection and analysis, whereas theoretical articles must rigorously construct arguments, utilize logical reasoning, and draw from the existing literature. As the current scoping review’s research area has not been thoroughly examined, the decision was made to incorporate a wide array of literature types, including theoretical papers.

Four electronic databases were searched: EBSCOhost, Crossref, Semantic Scholar, and the Education Resources Information Center (ERIC). Moreover, a manual search or “hand-searching” (Chapman et al., 2010) was conducted after searching the databases to locate relevant studies missing in the databases searches.

2.3 Stage 3: selecting relevant studies

The four stages of study selection were based on title, abstract, and full-text searches, according to the relevant sections of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines (Tricco et al., 2018; Figure 1).

The most recent search of the electronic databases was conducted on 23 October 2022. Overall, 1,330 articles were initially identified using the four databases, of which 260 duplicate articles were excluded. Subsequently, 1,070 articles underwent a two-phase review. The first phase involved excluding irrelevant articles by scrutinizing their titles and abstracts. The second phase examined the full texts of the remaining articles to remove those that were not relevant. Finally, 25 articles were further analyzed, and the authors reviewed and verified their full texts for inclusion in the study.

2.4 Stage 4: extracting, organizing, and charting the data

Summaries of the 25 included studies were developed based on indicators, including authors, year of publication, country location, research design and methods, study population, sample size (for empirical studies), and brief descriptions of the outcomes (Table 3).

3 Results

3.1 Stage 5: synthesizing, summarizing, and reporting the results

Following Arksey and O’Malley (2005) framework for scoping reviews, the following sections summarize, report, and discuss the findings of the 25 included studies. Each of the reviewed studies is represented by the letter S (Study), followed by a number (Table 3) (e.g., S1 represents the first study in the reviewed list). The coding and analysis system included three main categories (i.e., general characteristics, research methods, and thematic areas), each with several subcategories. Thematic analysis was performed in the following six steps (Braun and Clarke, 2012): familiarization with the data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing potential themes, defining and naming themes, and producing reports.

3.2 General characteristics of included studies

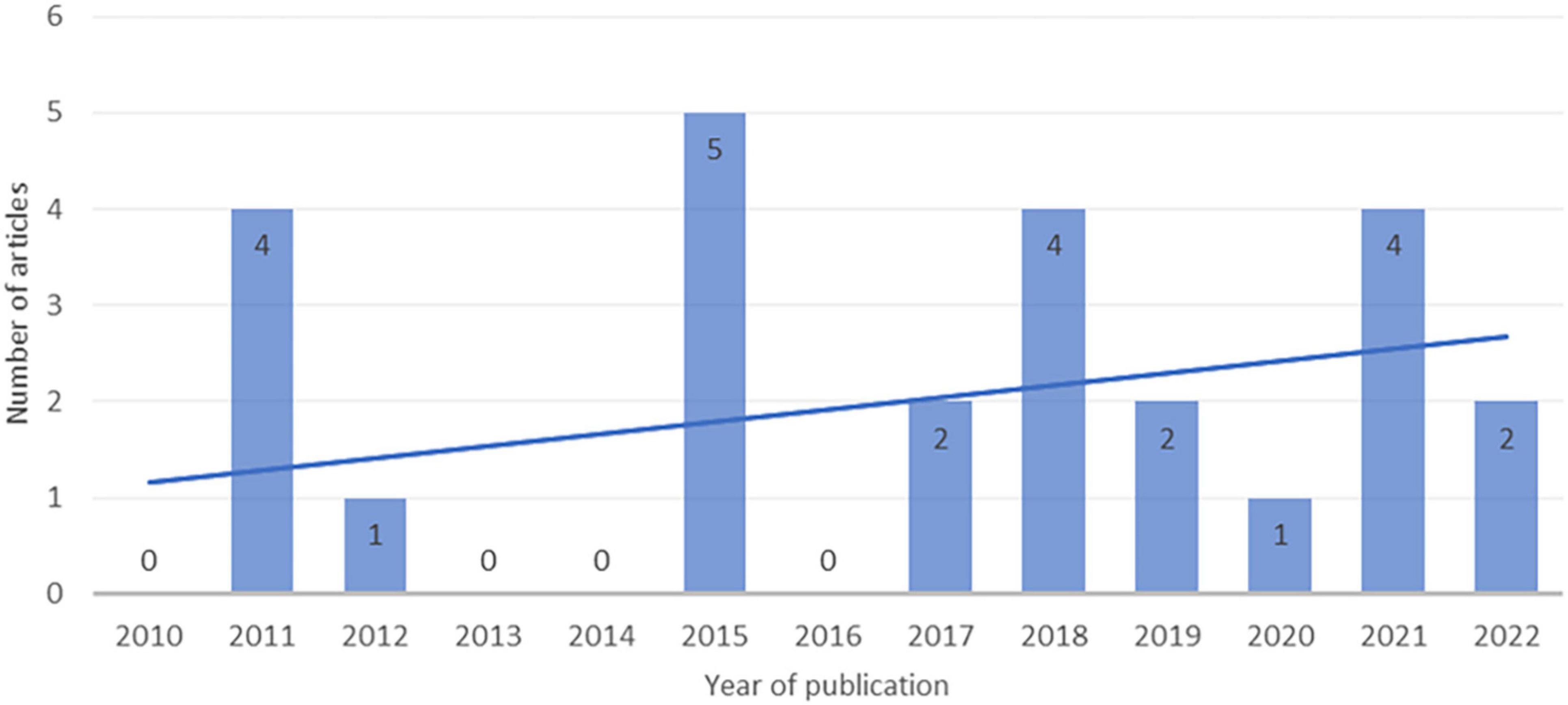

We identified 25 peer-reviewed articles relevant to counseling adult HE students between 2010 and 2022. Most studies (80%, n = 20) were published between 2015 and 2022 (Figure 2), indicating increased popularity among scholars after 2015. Table 3 shows that 21 of the 25 reviewed studies were conducted in the USA (84%), one was conducted in Israel, one study was conducted in Colombia, one was conducted in Slovenia, and one was conducted in the USA and Ireland.

3.3 Research methods of included studies

Ten of the 25 reviewed articles did not explicitly identify their research designs or methodologies. Therefore, we use the information provided in the methods section to classify the methodological paradigms used in these studies. As shown in Table 3, our review included 17 empirical and eight non-empirical studies. In the empirical studies group, six (24% of the total studies) used qualitative methods for data collection, four (16% of the total studies) used quantitative methods, five (20% of the total studies) used mixed methods, and two (8% of the total studies) were case studies. The non-empirical studies included four literature reviews, two theoretical papers, one discussion paper, and one comparative study.

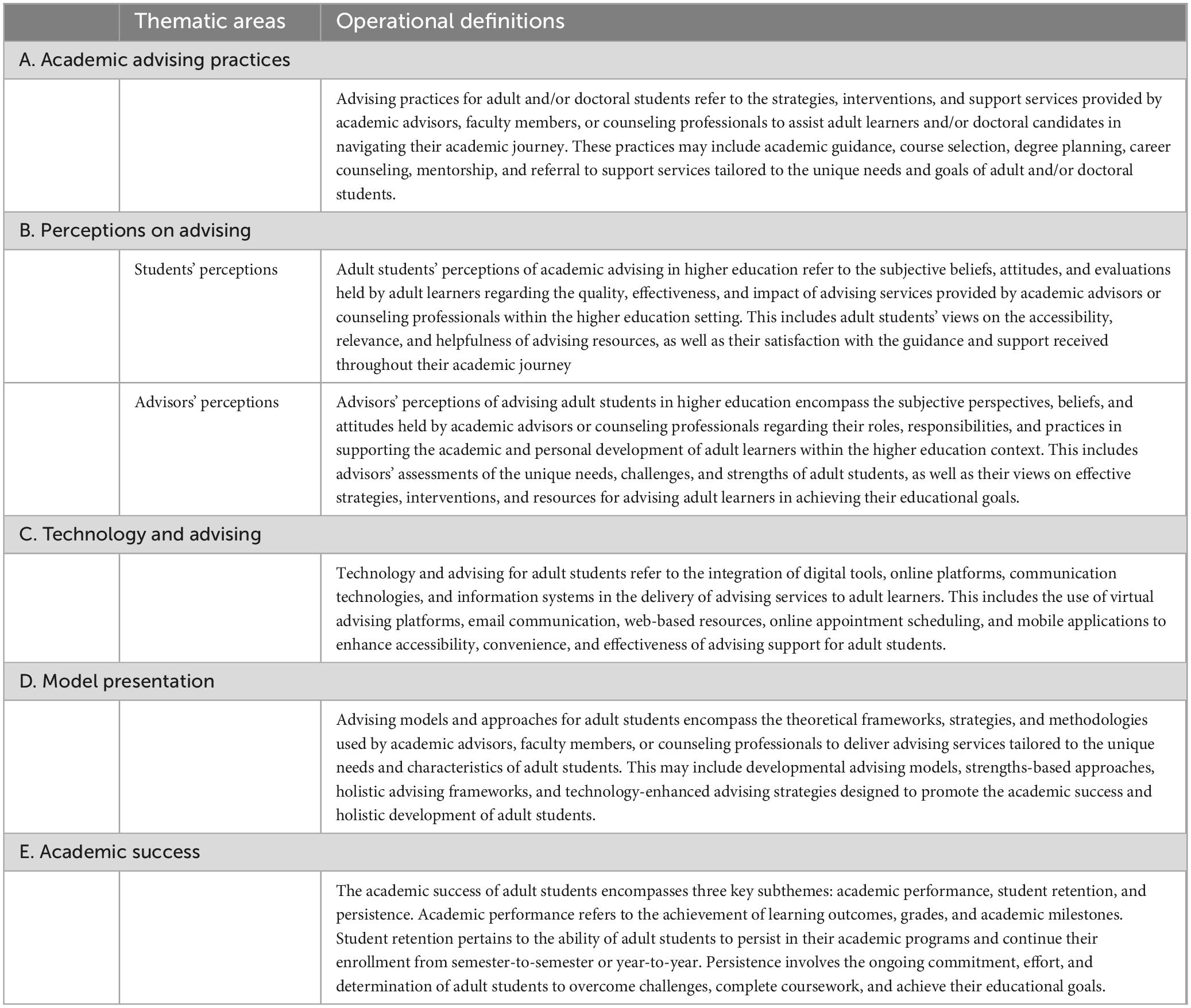

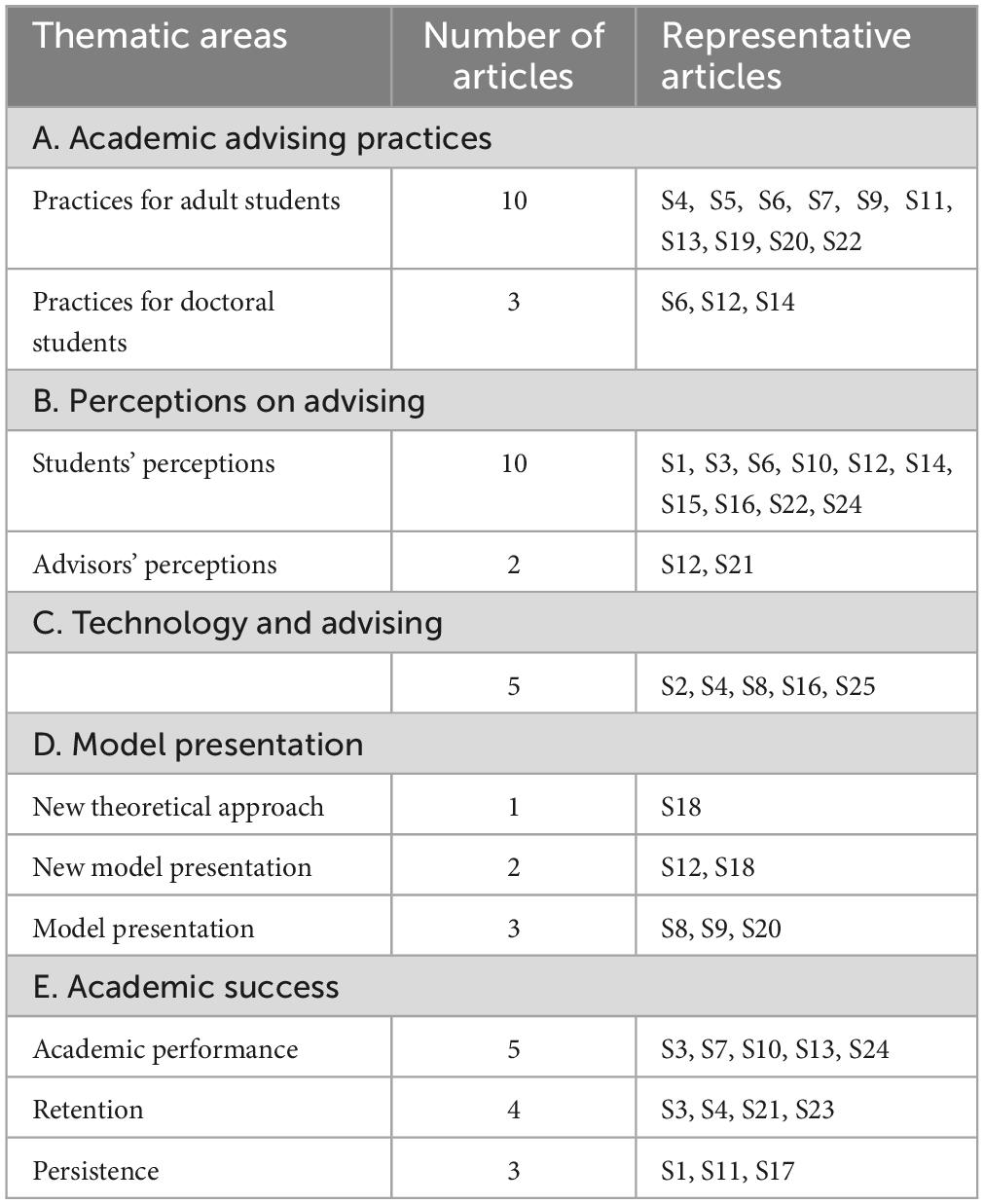

3.4 Thematic areas of included studies

Five thematic areas emerged from this review, as outlined in Table 4. Additionally, Table 5 provides detailed information on the various research themes and their corresponding articles. Our analysis revealed similarities across the various themes and concepts explored in the reviewed studies. The most common theme was advising practices for adult and doctoral students (52%, n = 13). The second most common theme was the academic success of adult students (48%, n = 12) (containing three key subthemes: academic performance, student retention, and persistence), followed by adult students’ and advisors’ perceptions of academic advising (48%, n = 12). Other themes examined were advising models and approaches (24%, n = 6) and technology and advising (20%, n = 5).

4 Discussion

4.1 Academic advising practices

4.1.1 Advising practices for adult students

Effectively advising adult students in HE presents unique challenges due to the diversity of their life experiences, responsibilities, and educational aspirations. Our review highlighted various practices and strategies essential for providing tailored guidance to adult students. These included holistic approaches, developmental advising methods, proactive interventions, and the pivotal role of flexibility and accessibility in counseling services. Recognizing and addressing the multifaceted needs of adult students in HE is essential for offering comprehensive support that not only promotes academic success but also nurtures personal growth. Regardless of their learning environment, adult students in HE required a complex and holistic advising model that should be individualized for their specific learning group, taking into consideration their unique life experiences, challenges, and needs (Schroeder and Terras, 2015; Mier, 2018). Recognizing adult students’ diverse challenges and aspirations, advisors should provide guidance that spans the personal, professional, and academic realms. This entailed understanding their life experiences, career goals, and academic aspirations to offer tailored advising. Advisors needed to be equipped with a comprehensive understanding of adult students’ backgrounds, ensuring that guidance was academically focused and considered their personal and professional lives. The findings by Schroeder and Terras (2015) indicated that quality and effective advising for graduate learners was holistic, encompassing five essential characteristics (themes): guidance on program requirements, trust in the advisor, personalized advice, recognition of the importance of advising, and the use of electronic communication for timely responses. Adult students benefited from programmatic guidance that included direction, scheduling, course selection, and assistance with program policies (Schroeder and Terras, 2015; Esposito et al., 2017). Non-traditional students benefited when instructors established clear expectations at the onset of a course. Providing formal and informal feedback on assignments and daily progress can foster a positive learning experience (MacDonald, 2018). A holistic approach to advising was especially beneficial for adult students belonging to racial and ethnic minority groups who might feel marginalized, as it acknowledges their unique needs and individual situations (Mier, 2018).

Mier (2018) also recognized the unique life experiences that shape adult students’ educational desires and experiences and suggested that adult students might benefit from a more developmental approach to advising. This approach considers their life experiences and problems and shapes their educational desires and experiences. A caring and thoughtful advisor should be available to provide extra support, direct them toward proper resources, and offer concrete solutions to problems. Furthermore, Roessger et al. (2019) suggested offering additional non-planning advising sessions for adult students who sought a developmental approach and an attitude of care from their advisors tailored to the specific needs and preferences of the adult students in the study. Similarly, Jelenc-Krašovec (2011) and MacDonald (2018) emphasized lifelong learning and highlighted the multifaceted nature of guidance and counseling adult students in HE. Adult students have diverse goals and embark on education at different life stages, requiring varied guidance and counseling options tailored to their needs (Jelenc-Krašovec, 2011). Advisors should recognize adult learners’ experiences, validate their prior knowledge and skills, and guide them on their continuous learning journey. This recognition empowers adult students and makes them feel valued and understood.

The importance of continuous positive and extrinsic motivation for non-traditional students was emphasized by MacDonald (2018). Given adult students’ emotional vulnerabilities and past experiences, advising could provide structure, specific learning objectives, immediate feedback, and constant access to their grades and records, all of which could help build student motivation, reduce anxiety, and help students persist. These students often developed a self-concept and lacked positive internal motivation for school due to past negative experiences (MacDonald, 2018). The positive and frequent involvement of instructors and advisors could significantly impact student self-efficacy, perception, satisfaction, and learning motivation, leading to better retention. Establishing personal connections between instructors and students can enhance students’ motivation, accountability, and school investment. Many older students might be apprehensive or resistant towards being “told” what to study by an academic advisor, especially if the advisor is younger. Community college leaders should be sensitive to this issue and ensure that academic planning information reaches adult students respecting their autonomy and experience (Roessger et al., 2019).

The importance of proactive advising methods for adult students was further emphasized by Mier (2018). This approach is also known as intrusive advising, as it involves advisors intruding into a student’s personal space by contacting students, pushing them to stay connected with campus resources, such as scholarships and internship opportunities, and making them accountable for their academic progress. The proactive approach aims to catch problems before they happen and intervene in a way that motivates students to address these problems on their own. It brings together the best aspects of prescription and developmental methods, allowing advisors to pay attention to students as a whole, be aware of student needs, and predict instances where a student might be struggling and in need of assistance. Additionally, there has been a debate on whether academic advising should be mandatory for older students. While some evidence suggests that mandatory advising could help older students with program completion, other research has indicated that different types of advising may have varying effects on different students (Roessger et al., 2019).

Garzón-Umerenkova and Gil-Flores (2017) focused on adult students’ unique challenges and experiences, particularly academic procrastination. This study hypothesized that nontraditional students, owing to their additional responsibilities, might exhibit higher levels of procrastination than traditional students. Guiding interventions for procrastinating behaviors should be personalized, adapted to each student’s profile, and based on the reasons for procrastination. For nontraditional students, who often have less time available for study, guidance should help optimize time management. This can be achieved by setting realistic goals, establishing priorities, and using tools for task planning and monitoring execution.

The importance of advisor availability and responsiveness has been emphasized, and immediate responses from advisors are particularly valued. The study by Schroeder and Terras (2015) highlights the varying expectations of graduate learners in different learning environments regarding the response time of advisors. For example, classroom learners expected to hear from their advisors within 2 days, cohort learners were willing to wait 24 h for a response, and online learners required notification from their advisor within hours, would be frustrated after 24 h, and would begin to significantly worry by the 48th hour. The study also emphasizes the importance of advisors being readily available and willing to communicate frequently through electronic means, such as email, as per the preferences of graduate learners. For adult students, guidance and counseling should be accessible within their local environment, ensuring they are not solely tied to job centers or employment-focused entities (Jelenc-Krašovec, 2011).

In his study, MacDonald (2018) underscored the significance of early intervention, flexibility, and support in retaining adult students, as nearly half dropped out before receiving a degree. The study suggested that early intervention is crucial for non-traditional students who often need remediation upon arrival to reduce anxiety and fear related to attending classes with younger students, missing family events, feelings of guilt, and self-esteem. It also highlights the need for differentiated instruction by offering flexible schedules and programs that can adjust to the lives of adult learners. Several other researchers discuss the need for flexibility in advising adult students. Dikhtyar et al. (2021) recommended that academic advising services be available outside of regular business hours, well-promoted, and integrated with academic and occupational/career advising. Academic advising, career services, and tutoring are typically only available during regular business hours, making it difficult for students who have other commitments during the day. This poses a challenge for older students who may be juggling work, family responsibilities, and their education. Flexible and accessible advising services for older adults and working students should be provided through web-based resources, extended hours, and drop-in/walk-in advising (Mier, 2018; Roessger et al., 2019). Similarly, counseling centers should offer online support services through self-help literature and Facebook and Twitter connections to cater to non-traditional students (Bruce-Sanford et al., 2015).

4.1.2 Advising practices for doctoral students

In our literature review, we identified specific advising practices that have been highlighted by researchers, and were intended to address the challenges non-traditional doctoral students encounter, such as isolation and identity conflicts. Advisors must understand and address the unique needs of these students, fostering environments of trust and offering proactive guidance. Group mentoring models, culturally sensitive advising practices, and recognition of intense transferences in the advisor–student relationship are crucial for supporting doctoral students’ holistic growth and success.

Esposito et al. (2017) described doctoral programs as difficult and complex, with students entering these programs often unprepared for isolation, the feeling of always balancing, and standing on the margins. These feelings can be exacerbated when class discussions challenge their beliefs about race, class, gender, and sexuality. Advisors must understand the unique needs and challenges that their doctoral students face. Recognizing the potential for power imbalance is crucial, and advisors should strive to create an environment of mutual respect and trust. Advisors should be aware of their students’ diverse backgrounds and experiences and address any potential biases or prejudices that may arise. The advisors were encouraged to be proactive, providing timely feedback and guidance. This included setting clear expectations and boundaries and being available for regular meetings and check-ins (Morrison Straforini, 2015).

Esposito et al. (2017) emphasized the importance of mentors who can provide “culturally appropriate” guidance. This type of culturally informed and empathetic support would address academic concerns and the unique challenges faced by doctoral students due to their identities and backgrounds. Morrison Straforini (2015) stressed that advisors should be culturally sensitive and recognize the diverse backgrounds of their students. Advisors must be attuned to their students’ unique experiences and backgrounds, offering culturally sensitive and psychologically informed support. This includes addressing potential bias and ensuring the advising process is inclusive and equitable. Culturally sensitive advising practices were also recommended by Ryan et al. (2011) to support and guide nontraditional students better, especially those transitioning from the military. Advisors were encouraged to understand the military culture and the transition challenges associated with moving from a military to an academic setting. Applying attentive listening, recognizing the value of diverse experiences, and understanding and promoting the importance of social and family support could significantly enhance students’ academic journeys, making the transition smoother and more successful.

While advising prepares students for graduation requirements, mentoring offers psychological, emotional, professional, and academic support (Mansson and Myers, 2012). Building upon this concept, Esposito et al. (2017) proposed a multilayered group mentoring model that served both advising and mentoring roles to provide a supportive, nurturing, and empowering environment for its members, especially those who might feel marginalized in traditional academic settings. Alternate pedagogies, particularly home pedagogies, provide a foundation for mentoring groups’ approaches. This pedagogy identified culturally specific ways of organizing educational experiences in non-traditional settings, such as at home. A key aspect of the mentoring relationship is reciprocity, in which both parties (mentor and mentee) receive tangible and emotional benefits from the association. Members served as role models for one another, and more experienced students helped mentor newer students. This group-mentoring model requires participants, including faculty advisors, to be vulnerable, open, and loving. Traditional boundaries between advisors and advisees do not exist in this model. This approach recognizes and celebrates its members’ diverse backgrounds, experiences, and roles, fostering an environment of mutual support and growth. The authors believe that other institutions could benefit from adopting or adapting a similar approach to support their students, especially those who might feel marginalized in traditional academic settings.

Doctoral students, especially during the dissertation-writing process, might experience intense transferences from their advisors, viewing them as parental or authority figures (Morrison Straforini, 2015). Students might unconsciously view this phase as a chance to secure the ideal mentor they have always yearned for or rebel against an unfavorable figure from their past. While positive transference can motivate and heal, negative transference can significantly impede the academic journey. Additionally, advisors might experience counter-transference, viewing students as representations of their younger selves or as vehicles for their unfulfilled aspirations. Advising is multifaceted in addressing intense transfer between doctoral students and their advisors. Advising is instrumental in cultivating healthy and productive relationships between students and their advisors by fostering effective communication, promoting professional development, building trust and implementing proactive interventions.

The research training environment significantly affected students’ attitudes toward research and their research self-efficacy. Advisors are pivotal in shaping this environment, fostering positive attitudes, and enhancing students’ confidence in their research abilities. Effective communication is the backbone of advising relationships. Advisors should offer mentoring and collegial support, affecting faculty success and student outcomes. Key elements for a successful advising relationship, as highlighted by Mansson and Myers (2012), include support behaviors, information adequacy, and communication apprehension. Additionally, relational maintenance behaviors are vital for maintaining and strengthening the bonds between students and advisors, encompassing actions such as demonstrating appreciation, performing tasks, offering protection, extending courtesy, using humor, and setting goals.

4.2 Perceptions of advising

4.2.1 Students’ perceptions

Students’ perceptions of advising refer to adult students’ attitudes, beliefs, opinions, and overall views regarding academic advising services provided by educational institutions. These perceptions are shaped by the interactions and experiences students have with their academic advisors and by their own goals, expectations, and needs. In general, non-traditional students and adult doctoral students emphasized the importance of genuine engagement, active listening, and validation from their advisors. Recurring perceptions among adult students consistently underscored the significance of effective academic advising, trust, individualized attention, prompt communication, understanding student narratives, and the potential advantages of online academic advising and counseling. These insights highlighted the demand for personalized, comprehensive, and technology-driven approaches to academic advising and counseling tailored to the distinct needs of adult students in HE. Moreover, the beliefs and perceptions of adult students about advising were influenced by their cultural backgrounds and diverse learning environments. In particular, insights from doctoral students shed light on the intricate emotional, relational, and psychological journeys they underwent during the dissertation process. At the doctoral level, the student–advisor relationship transformed into a mentoring relationship, where the advisor served as a source of academic guidance and a role model, coach, and advocate for the student. Their relationships with their advisors, personal struggles with perfectionism, and challenges in managing time and emotions substantially shaped their experiences and perceptions of the academic advising process.

Sogunro (2015) emphasized the importance of effective academic advising practices for adult students. Adult students consider effective academic advising crucial for guiding them in the right direction, opening opportunities for success, and sustaining their motivation. They valued academic practices such as working with students to select courses relevant to their study area, developing a “Planned Program of Study,” and regularly providing valuable information. Non-traditional students viewed competent advisors as playing guiding and mentoring roles. Without effective advising, students may experience stress, discomfort, and unnecessary delays in graduation.

Bennett et al. (2021) examined the significance of academic advising programs such as TRIO Student Support Services (SSS) for adult students. Non-traditional students valued the support and guidance provided by academic advising programs such as TRIO SSS. The program offered academic advising assisted by degree planning and played a key role in fostering self-confidence through motivation and mentoring. Participation in the TRIO SSS program early in the academic journey was considered beneficial for adult students. They felt the program helped them transition to self-advocacy, become more engaged in the learning community and feel respected. Adult students felt a strong connection to the TRIO SSS program, considering it an extended family. This connection increases their engagement on campus and enhances their overall college experience. All participants’ positive experiences indicated that they were likely to recommend the TRIO SSS program to their peers, indicating a strong commitment.

Karmelita (2020) explored adult students’ perspectives on academic advising, highlighting the importance of a narrative approach and early involvement in the advising process. The adult students in Karmelita (2020) study viewed academic advising as essential for their successful transition to college. They valued advisors using a narrative approach and considered early involvement in academic advising crucial. The adult students also expected advisors to assist them in linking their past experiences to their current learning. Adult students desired comprehensive advising support to help them access available resources and understand their educational paths. They wished for a personalized approach acknowledging their unique challenges, past experiences, and aspirations.

Pullan (2011) identified a gap between the need for and availability of online academic advising and personal counseling and revealed gender differences in the need for certain services. The study also emphasized the importance of online academic advising and the need for a website that clearly describes counseling resources, including self-help materials. Adult students believed an online counseling system could provide a much-needed alternative or supplemental service, especially for crisis students. They also believed that online academic advising could offer opportunities for those who might not benefit from traditional face-to-face advising and present opportunities for students, staff, and advisors to establish connections outside the classroom.

Auguste et al. (2018) examined how advising interactions influenced non-traditional female students’ perceptions of their place within the academic landscape. Advising interactions significantly influence how non-traditional women students perceive their place within the academic landscape (Auguste et al., 2018). Non-traditional female students valued advisors who constructively engaged with their intersectional identities, provided guidance and advocacy, and offered constructive feedback. Some students shared experiences of negative interactions with advisors who seemed disinterested, failed to listen, or did not offer solutions to challenges. Sometimes, advisors functioned more as gatekeepers than advocates, resulting in frustrated and betrayed students. Positive interactions can strengthen a sense of belonging and support, whereas negative interactions can intensify feelings of marginalization.

Interview data by Parks et al. (2015) explored the experiences of student-veterans transitioning to HE, focusing on academic advising. The major themes from the interviews were recognition, knowledge, research, education and integration. The theme of recognition was particularly prominent, with participants expressing a desire to be viewed and treated as individuals with unique experiences and challenges. The article concludes that academic advisors often do not understand their student-veteran advisees or military experience. This lack of understanding could lead to reliance on stereotypes, negatively affecting the advising process. This study emphasizes the importance of academic advisors educating themselves about military culture to better connect with and support student veterans to ensure their successful transition and integration into HE.

Schroeder and Terras (2015) provided insights into adult graduate students’ advising experiences and needs in various learning environments, including online, cohort, and classroom settings. Adult students in all these environments emphasized the crucial role of academic advising for their success. They underscored the importance of trustworthy advising, describing it as “informative, clear, concise, and accurate,” and recognized its practical application in providing valuable guidance. All the students emphasized the value of a personalized plan, including timelines and course selection, over standardized and uniform program-completion plans. Despite the common desire for a comprehensive and holistic advising system, learning environments have significantly shaped individual needs. For example, online students highlighted the importance of an advisor as their primary connection to a university, with email as their preferred mode of communication. They placed high importance on prompt responses within 24–48 h. By contrast, cohort students prioritized advisors who could provide clear requirements, indicating that their advising preferences might be influenced by their cohort peers’ collective knowledge and experiences. In their in-person mode of study, classroom students appeared to have expectations more aligned with the traditional advising dynamics.

Other researchers have explored doctoral students’ perceptions of academic advising and counseling. Esposito et al. (2017) investigated the experiences of non-traditional doctoral students. In the context of this article, non-traditional students refer to those who might not fit the typical mold of a graduate student because of various personal, social, or economic factors. Nontraditional doctoral students face challenges such as faculty underestimating their abilities, unfamiliarity with academic norms, and balancing academic life with personal responsibilities. These students felt that they benefited from mentors who provided culturally appropriate guidance and emotional and psychological support. Mentoring is a supportive socialization process, helping students develop their academic, professional, and personal identities. Doctoral students recognized and celebrated their various roles (e.g., parents, partners, and teachers) and therefore valued the mentoring group that provided a space for observation, sharing, and encouragement, recognizing the challenges of the doctoral journey.

In a study by Mansson and Myers (2012), the advisor–advisee relationship in graduate school was characterized as a mentoring relationship. This relationship typically extends over several years and progresses through various stages, including initiation, cultivation, separation, and redefinition. Doctoral students emphasized the importance of guidance and support from their advisors, along with expectations for collegiality, involvement, dedication, honesty, empathy, and compassion. These behaviors were seen as invaluable for facilitating students’ socialization into the academic department, retention, timely program and dissertation completion, as well as enhancing their perceptions of the academic climate. Furthermore, advisors were described as advocates, sources of information, socializers, and role models, underscoring their multifaceted roles in students’ academic and professional development.

Furthermore, Mentoring Enactment Theory (MET) was employed to understand the dynamics of this relationship, particularly focusing on communication behaviors and interactions that contribute to its initiation, maintenance, and repair. The study found that advisees reported using six main relational maintenance behaviors: appreciation, tasks, protection, courtesy, humor, and goal setting, which align with MET theory and help sustain successful mentoring relationships. These behaviors not only contribute to academic success but also provide both career and psychosocial support to advisees. Overall, the findings emphasize the critical role of the advisor–advisee mentoring relationship in the academic and professional development of adult students in HE.

The article by Morrison Straforini (2015) provided insights into the challenges dissertation candidates face, especially those from nontraditional backgrounds. The author emphasizes that the doctoral dissertation was a pivotal developmental milestone and represented a transition from studenthood to the professional world. The dissertation students often struggled with their dual roles as adults in various aspects of their lives (e.g., as teachers, partners, and parents). The dissertation process could be a transformative experience, but it could also bring unresolved conflicts and emotions to the surface, especially among nontraditional students. One of the challenges highlighted was the tendency of candidates to overidealize their advisors. This could lead to an intense fear of criticism, paralyzing their progress. When combined with low self-esteem, this idealization could be particularly obstructive during the most creative phases of the dissertation process.

4.2.2 Advisors’ perceptions

Our review has identified only two articles (Mansson and Myers, 2012; Sapir, 2022) that explore advisors’ perceptions of advising adult students in HE. Both articles highlight the pivotal role of advisors in shaping the academic experiences of non-traditional students, emphasizing the importance of understanding, empathy, and proactive guidance.

In the context of doctoral studies, as examined by Mansson and Myers (2012), advisors often perceived their relationship with doctoral students as a mentoring connection. This identification stems from the fact that advisors typically exhibit the characteristics and behaviors associated with mentors. Specifically, advisors viewed themselves as academically and professionally supportive advocates who were deeply invested in the academic and professional development of their advisees. They offered academic guidance and focused on the holistic growth of their advisees, fostering a professional and personal relationship. Advisors served as role models, embodying the skills and attributes their advisees aimed at acquiring, and underscoring the importance of comprehending academia’s formal and informal rules. This relationship was established based on mutual respect, trust, and shared commitment to academic and professional advancement.

Sapir (2022) investigated the perspectives of student support practitioners in Israeli HE institutions, particularly their interactions with nontraditional students. These practitioners, equipped with professional expertise and local practice-based knowledge, emphasized the critical stages of a student’s academic journey, namely, enrollment and potential withdrawal. They believed that proactive support and guidance at the enrollment stage could preemptively address many challenges, thus reducing the chances of course changes or withdrawals. Moreover, they advocated for a nuanced understanding of student withdrawal, recognizing that sometimes leaving might be in the student’s best interest. In such cases, they often navigated beyond their formal roles, offering advice on alternative educational paths and ensuring a smooth transition for the student, whether within or outside the institution.

4.3 Technology and advising

In recent years, the growing integration of technology in the advising process has emphasized the significant role that technological tools can play in counseling and advising, particularly for adult students. As evidenced by the literature, there is an evident shift toward online support modalities and synchronous communication technology in addressing the unique needs of adult students and promoting their academic success and mental wellbeing. However, specific approaches may vary depending on the context and individual needs, thus emphasizing the importance of personalized, meaningful, and technology-based advising and counseling for adult students.

The study conducted by Pullan (2011) highlights the crucial role of online academic advising and personal counseling, particularly for adult students. These services were identified as essential in addressing the unique needs and challenges faced by adult students and fostering their academic success and mental wellbeing. Institutions are encouraged to prioritize and expand these services to ensure holistic support for the adult student population. This study emphasizes the transformative potential of online academic advising and personal counseling for adult students. This underlines the growing demand among adult students for digital advising platforms, highlighting a discernible gap between the current availability of such services and their actual needs. Additionally, this study highlights that academic disengagement is a prevalent challenge, particularly among adult students. These students might be present in classes but often do not interact significantly with professors or advisors outside the classroom. By offering online academic advising to counter academic disengagement, institutions can foster deeper connections and ensure that adult students, who often have varied schedules, can benefit from guidance at their convenience.

College students’ mental wellbeing, including adults, is a growing concern. The study pointed out that while online personal counseling and career services might be rated with a lower need than other services, their implementation is crucial. With increasing reports of students facing issues such as stress, depression, and anxiety, online counseling platforms could provide timely and accessible support. Such platforms should clearly describe the available counseling resources, maintain confidentiality, and provide links to counseling centers from other institutions.

This article also highlights the pivotal role of counseling centers in supporting students and emphasizes the need for enhanced digital resources. It is recommended that counseling centers maintain a comprehensive website detailing the available resources, including self-help materials. Access to referral information, staff contact details, and clear confidentiality guidelines were essential. Furthermore, the article suggests counseling center websites should link to other institutions’ counseling services, ensuring a broader support network. There was also a call for immediate counseling or referral services for students facing mental health crises. The availability of self-help tools, information on local counseling services, and details about health and wellness programs were also highlighted as crucial components of the holistic counseling approach. The overarching theme was the importance of transparency, accessibility, and comprehensive support in counseling centers, especially in today’s digital age.

Bruce-Sanford et al. (2015) also emphasize the importance of counseling centers providing online support services, including self-help literature and connections through Facebook and Twitter, to accommodate non-traditional students. They highlight the use of various technological communication tools by counseling centers, such as iPad, iPhone, Skype, blogs, Blackboard for online classes, and Instant Messaging, as means for non-traditional students to access information and establish connections. Additionally, it is suggested that promoting a more active online community for non-traditional students and their support systems could be beneficial to address any feelings of disconnection.

A self-directed advising model was developed by faculty members from the adult education and training specialization at the School of Education at Colorado State University (CSU), USA to effectively and meaningfully advise graduate students remotely (Gupta, 2018). This model was conceptualized based on previous theories of advising and adult learning, incorporating elements such as a comprehensive perspective on adult development, self-directed learning, and an integrative advising approach, all aligned with the program’s teaching philosophy. A self-directed advising approach was developed to effectively and meaningfully advise graduate students remotely. The authors further explain how the model was transformed into an interactive online advising portal from its conceptual stage. This portal allows students to engage in tasks, make decisions about course sequencing, engage in reflective journals, and communicate with peers and faculty. The more they engaged in tasks within the portal, the more they developed self-directed skills and behaviors, and became more responsible for their educational journey. The creation of this structure aimed to motivate advisees to utilize all portal features and cultivate self-directed behaviors while navigating the advising process. The self-directed advising model and the online advising portal were specifically designed to empower advisees and foster a transition toward becoming self-directed learners.

Remote academic advising (RAA) is a method that uses synchronous communication technologies like Zoom, MS Teams, Google Meets, Adobe Connect, etc. This approach has proven particularly beneficial for adults, online, and graduate students (Wang and Houdyshell, 2021). Using synchronous communication technology through video conferencing can cultivate personal connections, enhance social presence, and promote emotional and cognitive engagement in academic advising. Wang and Houdyshell (2021) found a strong preference among study participants for the use of synchronous communication technology for academic advising. The authors noted significant disparities in the perceptions of RAA across sex and age groups. For instance, female students generally held a more positive view of RAA than male students and students aged 21 years and older preferred RAA over traditional in-person academic advising. New students who have not experienced face-to-face interactions with their academic advisors may encounter additional obstacles to effectively adopting RAA. Academic advisors should leverage the video functions of synchronous communication technology to establish personal relationships and foster greater rapport, particularly with new students. Synchronous communication technology is considered a valuable alternative, particularly for students facing challenges in visiting campus offices or requiring prompt responses. The students appreciated the university’s swift adaptation to this mode of advising and hoped it would remain an option even after the pandemic.

Advising and counseling adult students in HE institutions necessitates a modern approach integrating technology, especially given the increasing reliance on online support modalities (Baruah et al., 2022). Given the evident shift toward online support modalities, university counseling centers are encouraged to offer online and offline support mechanisms. Telemedicine visits, encompassing telephone, text, and video conferencing methods, have been highlighted as efficient tools, often allowing for rapid scheduling when required. This article also emphasizes the development of workshops and interventions tailored to specific student demographics, such as age, gender, and roles as traditional or non-traditional students. Online support platforms such as social networking sites, online forums, and instant messaging allow immediate social support and eliminate the need for physical proximity. These were highly beneficial to students, particularly nontraditional ones, in managing stress. Institutions were also urged to identify and support female students with higher course loads, as they were found to be more vulnerable in terms of perceived stress. Integrating technology, especially online platforms, was crucial to support adult students’ academic journey effectively.

4.4 Model presentation

This review discusses several advising models that offer unique insights and strategies for advising adult students on HE. By understanding and applying these models, advisors can cater to adult learners’ specific needs, motivations, and challenges, thus ensuring a more effective and tailored advising process. While each model presents a distinct approach to academic advising, they all share a common emphasis on understanding and addressing the unique needs of adult learners. These models are designed to support various populations, such as military veterans and doctoral students, underscoring the importance of personalized guidance. Across these models, there is a shared emphasis on flexibility, understanding, and empowerment to ensure that adult learners receive the necessary support to thrive on their academic journeys.

Ryan et al. (2011) introduced Schlossberg’s transition model, which addresses general life transitions, as a framework for understanding the transition of military veterans to HE. This model is a theoretical framework Schlossberg et al. (1995) developed to understand how individuals cope with and adapt to life transitions. The model assumes that how individuals respond to transitions is influenced by a combination of factors, categorized into the “4 Ss”: Situation, Self, Support, and Strategies. In the context of HE, this model is particularly pertinent for advising adult students, who often face unique challenges and transitions compared to traditional students. By understanding these factors, advisors can provide tailored support to students, thereby promoting personal and academic success. From the perspective of Schlossberg theory, the goals of advising are to help students gain a greater sense of control and hopefulness about academic transitions (situations), develop academic motivation and skills (self), build and utilize support networks (support), and develop effective coping skills (strategies). Schlossberg’s transition model provides a holistic view of transitions, emphasizing that the experience of change is multifaceted and influenced by a combination of situational, personal, social, and coping factors.

Jelenc-Krašovec (2011) provided a comprehensive overview of guidance and counseling in adult education, specifically focusing on situations in Slovenia, England, and Ireland. This article introduces a model presented by Rivis in 1992 (unpublished work) within the context of guidance and counseling activities in Slovenia. This model serves as a foundational framework for advancing guidance and counseling activities, particularly in the adult education domain in Slovenia. The model proposed by Rivis could potentially serve as a starting point for further advancements in guidance and counseling activities in Slovenia. It is based on three appearance forms of developing guidance and counseling activities: employment-oriented, education-oriented, and “independent” guidance. Employment-oriented guidance focuses on guiding adults toward careers and professions, and aligning their educational pursuits with job market demands. Education-oriented guidance emphasizes adults’ educational journeys, ensuring they are informed about educational opportunities and can effectively navigate their academic pursuits. “Independent” guidance is broader and more holistic, addressing adult learners’ personal and social aspects, not just their career or educational goals. The model recognizes the diverse needs of adult students and emphasizes the importance of local community engagement. This study concluded that the Rivis model offers a robust and comprehensive framework for advising adult students in HE. Its emphasis on diversity, holistic guidance, and community engagement makes it particularly suitable for addressing adult learners’ unique challenges and aspirations.

Mansson and Myers (2012) presented the Advisee Relational Maintenance Scale (ARMS), a novel measure developed in the context of Mentoring Enactment Theory (MET) (Kalbfleisch, 2002). The ARMS aims to assess the relational maintenance behaviors employed by doctoral advisees in their interactions with their advisors. The advisor–advisee relationship was considered a mentoring relationship in this study. The ARMS identified six key behaviors: appreciation, tasks, protection, courtesy, humor, and goals. The development of the ARMS marked an initial step in advancing the literature on advisor–advisee mentoring. The ARMS holds potential utility in counseling and advising contexts as a tool for evaluating the current state of the advisor–advisee relationship. This study indicates that advisees’ use of relational maintenance behaviors with their advisors is more closely linked to their perceptions of the quality of the advisor–advisee mentoring relationship than the duration of the relationship. This implies that understanding the relationship’s current state allows tailored interventions to address specific challenges or areas of improvement.

A self-directed advising model was presented by Gupta (2018) to address the need to advise graduate-level students from a distance more effectively and meaningfully. The model was designed to reflect the diverse needs of students, faculty, and the global competencies expected of graduates. It incorporated various advising theories as its theoretical foundation and was grounded in heutagogy, a self-directed, self-determined approach that builds on constructivist and humanistic learning philosophies. The model was transformed from a conceptual stage into an interactive online advising portal. This portal allows students to decide course sequencing, engage in reflective journals, and communicate with peers and faculty. This study addresses the need to advise adult students engaged in graduate-level distance learning. The self-directed advising model aims to empower advisees, including adults, to become self-directed learners by engaging them in building self-directed behaviors and transferable skills through the advising process. Ultimately, the model enabled advisees to become self-directed learners by transforming the advisee’s role from passive to active learner and the advisor’s role from authoritative leader to mentor, making the advising process both outcome- and growth-based. This holistic approach ensured that adult students gained academic knowledge, skills, and insights that were helpful and useful in many aspects of life.

Reynolds (2021) of the University of California introduced an existentialist advising approach grounded in applying Jean-Paul Sartre’s existentialist philosophy to academic advising. Existentialist advising highlights students’ freedom and responsibility, fostering an advising relationship that encourages authentic choices. This approach prioritizes students’ freedom and responsibility, urging them to make genuine decisions regarding their academic and personal paths. This underscores the notion that students have the agency to shape their identities and futures, and bear responsibility for their choices. Reynolds discussed how existentialist advising can effectively address common issues in academic advising such as identity foreclosure, in which students prematurely commit to their identity without exploring other options. For adult students who often seek personal or professional fulfillment, this approach encourages the introspection of values, beliefs, and life objectives. Advisors can guide students through existential questions about career shifts, life transitions, and personal growth, aligning academic paths with broader life goals. The author also compared existentialists advising on other approaches and responded to potential critiques of existentialist advising. The author introduces existentialist advising as a novel theoretical approach to academic advising. This approach offers a distinctive perspective on advising and provides advisers with new tools and strategies for assisting students.

4.5 Academic success

4.5.1 Academic performance

Based on the research reviewed, a tailored, holistic, and proactive advising approach that considers academic and personal aspects is essential for adults’ academic performance and overall wellbeing. By understanding their unique challenges, needs, and life experiences, advisors can offer more effective guidance, ensuring that students achieve their educational goals and feel supported throughout their academic journey.

Academic advising plays a crucial role in the success of adult or nontraditional students. Mier (2018) emphasized the importance of proactive advising, which involves anticipating student needs and identifying potential challenges before they arise. Particularly for distance learning and adult students, the quality of advising directly correlated with academic outcomes. Tailored advising was identified as a crucial element in helping these students navigate their academic journey more effectively, leading to improved performance and deeper understanding of their field. Mier (2018) specifically addressed the challenges faced by distance learning and adult students, emphasizing the pivotal role of effective advising in enhancing their academic performance. Sogunro (2015) further underscores the significance of academic advising in motivating adult students. By employing effective advising practices including developmental and prescriptive methods, adult students can better navigate their academic journeys, ensuring they remain on track and achieve their educational goals.

Karmelita (2020) emphasized a holistic approach to advising. Advisors can offer more tailored guidance by considering both the academic and personal aspects of a student’s life. This comprehensive approach could significantly affect the academic performance of adult learners, ensuring that they achieve their desired outcomes and feel supported throughout their academic journeys. Garzón-Umerenkova and Gil-Flores (2017) emphasized the need to understand the diverse needs of students, especially adults. By offering tailored academic advising, institutions can improve student outcomes. Recognizing adult students’ unique challenges and life experiences can lead to more effective advising strategies, ultimately contributing to their success in HE. Finally, Bennett et al. (2021) highlight several aspects of academic performance that improved through the TRIO SSS program. This suggests that a student-centric approach that considers academic and personal aspects is essential for the success of adult students. In summary, the TRIO SSS program was pivotal in improving various aspects of academic performance, including retention rates, 3-year graduation rates, cumulative GPAs, and overall academic success, especially for nontraditional students.

4.5.2 Student retention

The literature indicates that academic advising is essential for retaining adult students in HE. Critical stages such as enrollment and withdrawal necessitate rethinking support strategies, and the dynamics of the advisor–advisee relationship influence retention. Emphasis is placed on tailored support strategies at the faculty or department levels, with institutions encouraged to offer continuous support, extending beyond student withdrawal.

Academic advising has emerged as a crucial factor in student retention in HE, particularly for non-traditional students, as highlighted by Sibson et al. (2011). Nontraditional students often grapple with feelings of loneliness, alienation, and mistrust within the academic culture, and effective academic advising, as noted by Sapir (2022), could mitigate these challenges. Institutions have recognized the significance of retaining adult learners, often emphasizing the education affordability for these students (Bennett et al., 2021). The role of student support practitioners, providing personal counseling and academic advising, was integral to retaining non-traditional students, offering insights and practice-based knowledge developed through their work experience (Sapir, 2022).

Critical stages, such as enrollment and withdrawal, have been identified as pivotal moments for rethinking support strategies, potentially reducing student challenges significantly (Sibson et al., 2011). The dynamics of the advisor–advisee mentoring relationship and the behaviors sustaining it, as explored by Mansson and Myers (2012), also play a role in student retention. Practitioners have underscored the importance of considering support at the faculty or department levels, leading to more tailored and effective support strategies (Sapir, 2022). Importantly, institutions were viewed as responsible for accompanying students, even during transitions, with a commitment that extended beyond student withdrawal (Sibson et al., 2011).

4.5.3 Student persistence

The quality and nature of advising, combined with institutional support and flexibility, are paramount for the persistence of adult or non-traditional students. The combination of personalized guidance, strong instructor connections, institutional support, and historical adaptability created an environment conducive to the success and persistence of adult or nontraditional students in HE.

For adult or non-traditional students, advising is vital to their academic path and essential for their persistence in HE. Auguste et al. (2018) emphasized the importance of personalized guidance and support in advising adult students. The study highlighted positive and negative advising experiences, emphasizing how indifference or a lack of advisor engagement could demotivate students. Conversely, clear guidance, identity recognition, and advocacy were identified as factors that could significantly enhance motivation and a sense of belonging. The advisor’s capacity to understand and validate the unique challenges faced by nontraditional students emerged as a key element influencing their persistence in HE.

MacDonald (2018) further focused on the role of instructors and institutional support in the persistence of adult learners. This research emphasizes the significance of establishing a strong connection between students and their instructors and with school facilities. When adult students form personal connections with their instructors, they demonstrate increased motivation, accountability, and investment in academic pursuits. Continuous positive motivation from instructors, tailored learning strategies, and the regular involvement of instructors and advisors profoundly impact various aspects of student life, including self-efficacy, perception, satisfaction, and motivation. These factors collectively contribute to the persistence of adult students during their academic journeys.

Remenick (2019) provided a historical perspective on non-traditional HE students. This study emphasized how institutions have adapted their policies and procedures over time to cater to these students’ unique needs. Emphasis on flexibility, recognition of non-academic activities, and provision of resources tailored to nontraditional students’ specific needs ensured they felt supported. This historical trend of adapting to adult learners’ needs has played a vital role in enhancing their persistence in HE.

5 Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first scoping review to focus on advising non-traditional students within a formal HE setting. This study analyzed 25 peer-reviewed articles related to academic advising and counseling of adult students in HE in terms of their general characteristics, research methods, and research areas. The findings of this review provided insights into the research questions outlined in the methods section.

The observed trends suggest a scarcity of literature on counseling non-traditional students in formal HE, despite a gradual and consistent increase in the number of publications on this topic. The majority of these studies conducted in English originated from the USA and mixed methods were more commonly used than a single quantitative or qualitative method. This trend aligns with a prior report by Jennings (2021), which highlighted the substantial influence of the United States and the United Kingdom on the international literature concerning academic advising, with the contributions to research from these two countries forming the largest bodies of work on the subject. However, this fact represents a significant gap in peer-reviewed literature, potentially introducing bias in the perspectives and experiences reflected in the literature on advising adult students.

In addressing the second research question, the study identified five principal research areas that received significant attention among researchers. Predominantly, researchers were interested in exploring perceptions of advising and academic advising practices, with subsequent attention given to technology and advising, advising models, and academic success.

This scoping review provided an overview of studies conducted in the domain of counseling adult students in formal HE since 2010. The categories developed in the review could serve as a framework to guide future reviews on counseling adult students in formal HE. Additionally, the findings of this study may suggest valuable directions for future research endeavors, particularly in addressing the knowledge gaps identified.

Our research has identified a gap about advisors’ perceptions with only two articles (Mansson and Myers, 2012; Sapir, 2022) exploring their dynamic interactions and relationships with non-traditional students. Given the scarcity of research on advising non-traditional students in HE, future research should prioritize investigating this area. Investigating advisors’ perceptions and capturing both sides of this relationship will allow a more holistic view of the advising process. This dual perspective ensures that nontraditional students’ unique needs, challenges, and aspirations are addressed comprehensively, leading to better outcomes for both nontraditional students and institutions. It could also provide valuable insights into the increasing concern for the professionalization of academic advising (McGill, 2019) and a radical reassessment of roles and practices within the institution of academic advising. Today, counseling has evolved from the periphery of HE to the core of student success, necessitating continuous training for academic advisors to stay informed about international best practices in counseling an increasingly diverse student population (McGill et al., 2020).

Another gap in the literature has been identified regarding counseling practices for doctoral students. Three studies (Mansson and Myers, 2012; Morrison Straforini, 2015; Esposito et al., 2017), one of which was a discussion paper (Morrison Straforini, 2015), explored the role of counseling for doctoral students throughout their academic journey. Considering the profound significance of completing doctoral studies for both individual students and society at large, further research in this area should be conducted.

Interestingly, the use of technology for counseling adult students in HE has gained notable attention among researchers, especially since 2015, as evidenced by the five articles included in this review (Pullan, 2011; Bruce-Sanford et al., 2015; Gupta, 2018; Wang and Houdyshell, 2021; Baruah et al., 2022). The evolving landscape of advising and counseling adult students in HE calls for a contemporary approach that integrates technology, particularly considering the growing reliance on online support modalities (Baruah et al., 2022). In light of this evident trend toward online support modalities, university counseling centers are encouraged to provide a range of both online and offline support mechanisms. Nevertheless, as technology advances and gains popularity as the HE landscape evolves, certain aspects must be clarified, including the quality, efficacy, and student satisfaction associated with online academic advising sessions, particularly for nontraditional students. Clear guidelines and best practices are essential to ensure consistency and quality across institutions and address considerations such as informed consent, confidentiality, and the security of online academic advising sessions (Ohrablo, 2016). Some researchers argue that online advising may lack the personal touch and rapport building that face-to-face interactions offer, which can be crucial for effective advising (Steele and Carter, 2002). The virtual nature of the interaction should not limit the depth or breadth of an advising session (Lowenstein, 2005). This underscores the importance of adopting a holistic, learning-centered approach to advising that specifically addresses adult students’ personal and professional aspirations in online environments.

In summary, this review highlights both the scarcity of literature on advising adult students in HE and the importance of understanding and responsiveness. It emphasizes the necessity for tailored, holistic, and technology-driven approaches to academic advising and counseling to meet the specific needs of adult students in HE. Furthermore, it underscores the significance of nurturing, culturally sensitive, and group-based mentoring approaches, particularly for doctoral students compared to other adult students.

6 Limitations and contribution