- School of Education, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou, China

Objective: Grounded in theories of globalization, this qualitative case study aimed to explore the understanding of play among Chinese teachers in private, for-profit Western style early learning centers.

Methods: The study encompassed 16 Chinese teachers working in four Western-style early learning centers. Data were gathered through semi-structured interviews. Following separate thematic analyses of each case, a cross-case analysis was conducted to compare and contrast the emerging themes, elucidating both commonalities and distinctions across the four cases.

Results: The findings from all four cases revealed a categorization of play into two main types: “play in class’” and “play out of class.” “Play out of class” was characterized as unstructured, enjoyable, and creative, emphasizing child autonomy and spontaneous learning. In contrast, “play in class” pertained to play-based curricula that were thoughtfully designed to align with specific teaching goals and learning objectives. It was seen as a structured method for fostering learning, highlighting the developmental appropriateness of such approaches.

Conclusion:: These findings underscore the educators’ recognition of the significance of play; however, it also illustrates that their perceptions have been shaped by the prevailing emphasis on children’s achievements in Chinese society.

Introduction

Over the past two decades, China has experienced profound transformations in its societal, cultural, economic, and legislative frameworks, impacting various sectors, including early childhood education. A pivotal shift in this domain is the growing acknowledgment and integration of “learning through play” within the educational policies and practices, tracing back to the early 2000s. The Ministry of Education Guidelines for Early Childhood Education, released in 2001, marked an early formal recognition of play’s critical role, introducing terms like “wan” for play and “Youxi” for rule-based play or games (Rao and Li, 2009). This foundational emphasis on play has been progressively reinforced in subsequent policies, including the comprehensive vision laid out in “The Fourteenth Five Year Plan for Preschool Education (2022).”

Further legislative developments, such as the proposed Preschool Education Law of the People’s Republic of China (2023), under deliberation, continue to emphasize play as central to preschool education, reflecting an ongoing commitment to cultivating high-quality, play-based learning environments. These evolving guidelines have catalyzed a significant shift in early childhood education across China, encouraging kindergartens to transition from traditional, teacher-led instructional methods toward more child-centric, play-based approaches. Examples of such transformative practices include Anji Play in Zhejiang Province, Lijin Play in Shandong Province, and the gamification of curricula in Jiangsu Province, showcasing the diverse implementation of play-based learning across both private and public educational settings. These initiatives, present in both private and public kindergartens, signify a transition away from “traditional group teaching”—a teacher-led instructional approach where children are frequently organized into large groups. This method is distinguished by a consistent teaching strategy focused on imparting knowledge through direct instruction. The teacher generally controls the pace of the lesson, content delivery, and interaction, offering minimal chances for individual participation or children’s input—toward an emphasis on child-led exploration and learning through play (Niu, 2023). However, while this topic has received academic attention, there has been limited exploration of how educators, particularly those in Western-style early childhood settings, perceive culturally divergent attitudes toward play.

Drawing on globalization theories (Latta and Field, 2005), this qualitative multiple-case study explores early childhood education (ECE) teacher’ understanding of play in China. We specifically focus on ECE teachers in early learning centers, considering the widespread establishment of such centers across the country (Ma, 2010) and their adoption of Western-style curriculum designs to appeal to parents (Yan, 2009). The research questions are as follows:

1. How do ECE teachers in private, for-profit Western-style early learning centers in China understand and conceptualize play within their educational contexts?

2. How do cultural and societal influences, particularly the emphasis on academic achievement prevalent in Chinese society, shape ECE teachers’ approaches to and valuations of play in early childhood education?

Literature review on play typology

Theories of play

Play, often viewed as a dynamic knowledge system, teeters on the edge of a child’s capabilities, and it has been the subject of multifaceted theoretical exploration concerning its diverse purposes, values, meanings, nature, effects, and influences (Bergen, 2014). Numerous classical theories of play, including those by Freud, Erikson, Piaget, and Vygotsky, have laid the groundwork for more contemporary theories that associate play with factors such as culture, environment, child development, and learning.

The notion of play as an educational vehicle can be traced back to ancient times, with Plato making early observations on the phenomenon (Morris, 1998). Subsequently, the typology of play has evolved, with Bergen (2014) categorizing theories of play into four historical periods: early theories encompassing Plato’s ideas, Enlightenment perspectives, late nineteenth-and early twentieth-century theories, and mid-to late twentieth-century theories.

During the Renaissance, Comenius (1632) and Locke (1693) delved into the educational implications of play and its positive impact on childhood development. These early perspectives laid the foundation for later theories of play. Figures like Froebel (1887), Pestalozzi (1894), Dewey (1910), and Montessori (1914) emphasized the educational value of play, while Schiller (1875), and Spencer (1873), and Groos (1898) explored its purpose.

In the mid-twentieth century, theories of play shifted their focus to defining play and understanding its purpose, conceptualizing it as a socio-cultural phenomenon. Influential thinkers such as Freud (1917/1956), Mead (1934), Piaget (1945), Huizinga (1950), Bateson (1955), Erikson (1963), and Vygotsky (1967) contributed significantly to these discussions. Their work underpins contemporary theories related to the stages of play and the cultural diversity of play, shedding light on how play fosters child development and learning (Gaskins, 2014).

Types of play in early childhood education

The concept of play within early childhood education encompasses a diverse range of definitions and frameworks, reflecting the complexity of its role in child development. Scholars have extensively explored play, highlighting its multifaceted nature and the critical role of child initiative (Pellegrini, 1991; Sutton-Smith, 1997; Meckley, 2002; Broadhead, 2004). Garvey (1991) champions child-led play, emphasizing the importance of children’s autonomy in choosing their play activities, which supports problem-solving, language acquisition, and social development. In contrast, Wood and Attfield (2005) present a continuum of play activities, ranging from free play, initiated entirely by the child, to non-play, directed solely by adults.

A significant debate in the field of Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) revolves around the distinction between play and work. Sutton-Smith (1997) views play as a voluntary, enjoyable activity driven by intrinsic motivation, whereas work is seen as obligatory. Montessori (1964) blurs these boundaries by suggesting play is “the child’s work,” highlighting the developmental importance of play activities. Elkind (2001) further articulates that play and work are not mutually exclusive but are complementary and can coexist, enhancing the learning experience.

Amidst these discussions, the concept of “pedagogical play” emerges as a bridge between free play and structured learning. Initially introduced by Edwards and Cutter-Mackenzie (2013), pedagogical play is characterized by a collaborative approach between the child and the educator, integrating educational objectives within a playful context. This form of play is designed to maintain the intrinsic motivation and enjoyment characteristic of free play while achieving specific learning outcomes.

Further elaborating on this concept, Stewart and Pugh (2007) and Rogers (2011) describe pedagogical play as an environment where educators strategically incorporate learning goals within play activities. This approach respects children’s interests and agency, leveraging their natural curiosity and engagement for educational purposes.

The terminology surrounding pedagogical play varies among scholars, reflecting the diversity of its applications. Epstein (2007) and Duncan (2009) refer to it as “intentional teaching,” emphasizing strategic educator involvement in play to meet learning objectives. Fleer (2011) introduces “conceptual play,” where imagination and cognition converge in play-based learning, actively fostering children’s conceptual understanding. Hardman (2008) uses “pedagogical activity” to describe the introduction of new experiences within a familiar context, expanding children’s knowledge base. Postman and Weingartner (1969) advocate for “educational inquiry” within play, encouraging a questioning and exploratory approach.

Wood (2014) categorizes pedagogical play into three types: child-initiated, adult-guided, and technical, each differing in the level of educator involvement and pedagogical intent. Building on this, Edwards and Cutter-Mackenzie (2013) delineate pedagogical play into open-ended (minimal teacher involvement), modeled (moderate involvement), and purposefully framed play (high involvement), each varying in structure and educational objectives.

The rhetoric and reality of play

The definition and interpretation of play vary across economic, social, and cultural contexts (Wood and Attfield, 2005; Rogers and Evans, 2008). It’s worth noting that the idealized concept of play is not always reflected in practice. For instance, while official documents worldwide promote play-based learning as a fundamental principle in early childhood education, practical guidelines to support play-based teaching are often lacking (Wood and Bennett, 1997). Additionally, individual teachers may have varying understandings and interpretations of the value of play and play-based curricula, leading to disparities between play rhetoric and classroom reality in many Western countries (Bennett et al., 1997; Wood and Bennett, 1997; Badzis, 2003; Wood, 2010).

Several factors contribute to this divide between theory and practice. Play is inherently spontaneous and unpredictable, making it challenging to assess. Yet, teachers are often required to demonstrate children’s learning and progress to parents through systematic documentation. There can also be misconceptions about how to teach and learn through play, the impact of play activities, and the relationship between play and play-based curricula (McAuley and Jackson, 1992; Wood and Bennett, 1997).

Kagan (1990) identifies three common barriers hindering the implementation of play in early childhood classrooms:

1. Attitudinal barriers: These relate to the attitudes of parents, educators, and community members toward play.

2. Structural barriers: These encompass the curriculum, policies, regulations, and mandates within educational contexts.

3. Functional barriers: These involve physical and bureaucratic constraints that limit educators’ ability to engage children in play, such as a lack of time and funding for training, insufficient benefits and wages, and limited community support.

The context of early learning centers

Early Learning Centers (ELCs) represent a pivotal component within the global early childhood education spectrum, characterized predominantly by a “learning through play” pedagogy. This approach, which is foundational to playgroups, center-based programs, and ELCs, underscores the integration of play in learning processes (Dadich and Spooner, 2008). In the context of China, ELCs have rapidly evolved into prominent educational entities. Distinct from conventional kindergartens, they provide a blend of academic and play-oriented learning, with a pronounced emphasis on the latter to foster holistic child development. Despite their commercial orientation, these centers primarily aim to deliver an encompassing educational experience that harmonizes imported educational philosophies with indigenous expectations (Britto et al., 2013; Woodhead and Streuli, 2013).

The emergence of ELCs in China mirrors a broader inclination toward adopting Western educational frameworks, particularly the play-based curricula favored by the Chinese middle class (Tobin et al., 2009; Crabb, 2010). Unlike traditional kindergartens that incorporate play as a component of their curriculum, ELCs are distinguished by their unwavering commitment to a play-centered educational model. This distinction makes them especially appealing to parents desirous of a Western-style education for their offspring (Ma, 2010).

Notably, Chinese ELCs cater to a wide age range, starting from infancy, which sets them apart from the standard kindergarten age group of three to 6 years (Vaughan, 1993). The significant presence of over 274,400 registered kindergartens across China in 2023 underscores the burgeoning market for ELCs, particularly among urban middle-class families (Strandell, 2013). The proliferation of ELC chains, exemplified by a network exceeding 1,000 branches in Beijing alone in 2023, attests to the escalating demand for such educational services (RYB Education Institute, 2023).

The private-for-profit sector’s role in the global early childhood care and education (ECCE) landscape, as highlighted by Woodhead and Streuli (2013), encompasses service provision, funding, and innovation. This sector has attracted attention due to quality concerns in certain public early childhood settings, leading to a notable expansion in countries with a pronounced emphasis on education, including China (Sosinky et al., 2007; Britto et al., 2013). The fusion of imported and local educational ideologies within Chinese ELCs offers a unique lens to explore the dynamics of cultural hybridity in education (Tikly, 1999; Pence and Shafer, 2006). As facilitators of academic and experiential learning, ELCs play a crucial role in shaping the educational trajectories of children, providing both academic instruction and enriching play-based experiences (Owen and Moss, 1989; McFarland-Piazza et al., 2012, cited by Statham and Brophy, 1991).

Theoretical framework

Globalization, defined as the integration of economies, politics, and cultures across nations (Burbules and Torres, 2000; Al-Rodhan and Stoudmann, 2006), encompasses the concept of cultural globalization (Robertson, 1992; Robertson and White, 2007). This aspect of globalization can lead to the emergence of transcultural patterns, altering perspectives and behaviors (Cannella and Soto, 2010). Cultural globalization challenges existing thought systems rooted in specific historical and socio-cultural contexts, particularly in social relationships (Appelbaum and Robinson, 2005). It’s important to recognize that while globalization can be bidirectional (where two countries mutually influence each other’s cultures), it often manifests unidirectionally, with more powerful nations setting cultural norms and affecting less powerful ones. In the cultural exchange between the West and China over the last three decades, China has often been influenced by the West (Bai, 2005). This phenomenon is especially evident in early childhood education (Tobin et al., 2009).

In mainland China, two waves of curriculum reform (the 1989 Regulations on Kindergarten Education Practice-trial version by the National Education Commission and the 2001 Guidance for Kindergarten Education by the Ministry of Education) have drawn from Western-style, child-centered models like Montessori, Reggio Emilia, and High Scope (Li et al., 2011). The philosophy of Developmentally Appropriate Practice (DAP) (National Association for the Education of Young Children, 1997) has also influenced Chinese early childhood education by emphasizing the importance of considering children’s abilities in play-based teaching and learning (Li et al., 2011). Although play-based curricula, imported from the West, may be unfamiliar to many Chinese teachers, they are generally regarded as more beneficial than traditional, lecture-based curricula—which involve a curriculum heavily focused on academic instruction and rote learning. Lessons in these curricula are structured around specific educational objectives, with a pronounced emphasis on literacy, numeracy, and other academic skills — for supporting children’s learning and development (Cheng and Wu, 2013).

Methodology

To investigate how teachers comprehend play in Western-style, play-based Chinese early learning centers, this study employed a multiple-case qualitative approach. This methodology, chosen to enhance data richness, accuracy, and findings’ generalizability, was well-suited for examining several cases (four centers with four teachers each) in-depth and longitudinally (Creswell, 1998; Stake, 2006). It was favored over a single-case study as it accentuated the distinctiveness of each case (Yin, 2014). A pilot study (Wang and Lam, 2017) preceded this research and involved interviews with two teachers from an American-style early learning center in Shenzhen. This pilot study aimed to understand how these teachers perceived and put into practice play-based teaching.

Participants

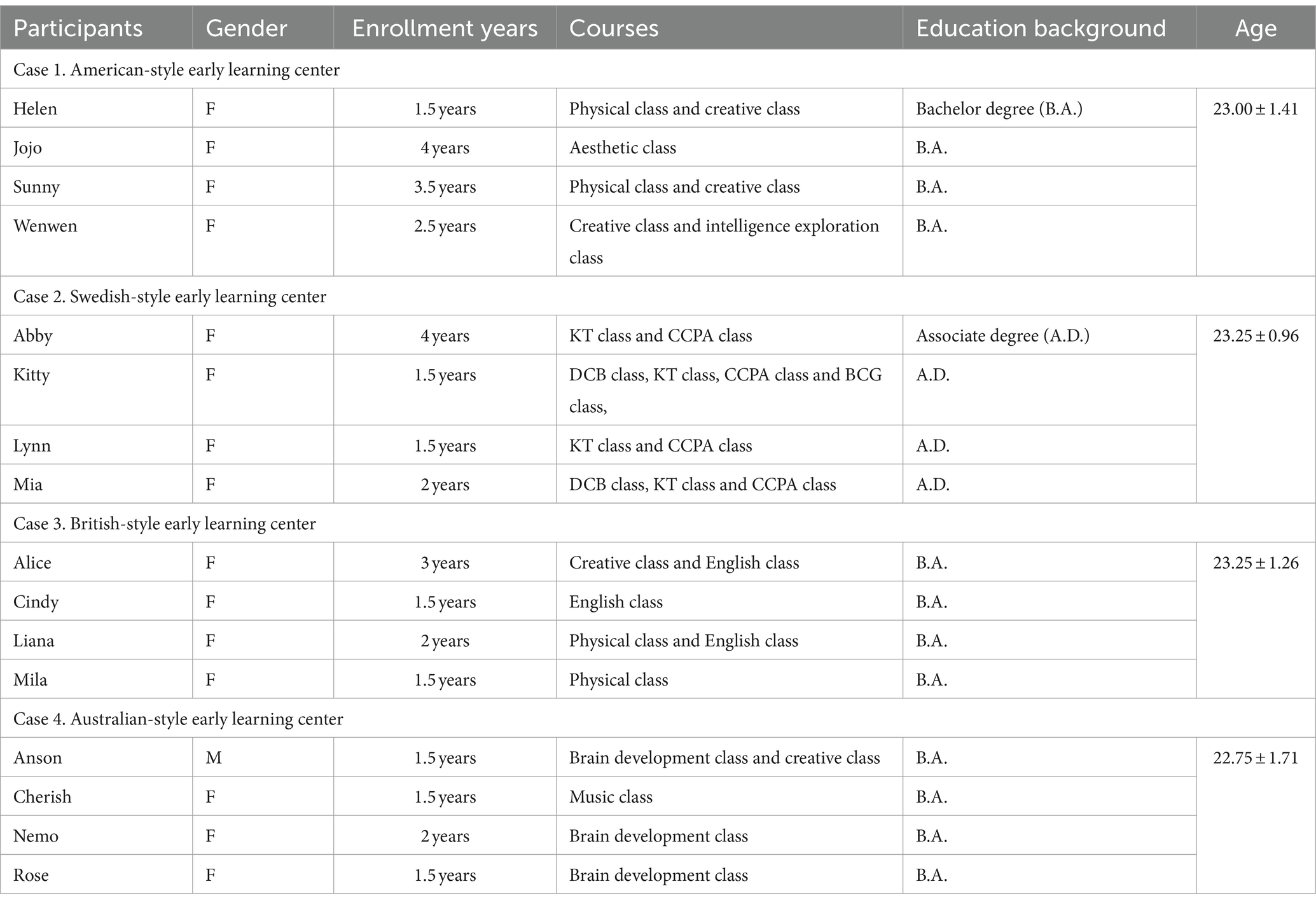

To gain insights into teachers’ perspectives, the study employed a purposive sampling strategy, selecting subjects based on specific criteria (Creswell, 2013). The research took place in four Western-style, play-based early learning centers located in Shenzhen, mainland China. Each center constituted an individual case, and the case boundaries encompassed full-time teaching staff. Sixteen participants, four from each center, were chosen according to the following criteria: (a) Chinese teachers instructing children aged 0–6 years; (b) Chinese teachers with at least 1 year of experience in the center (ensuring familiarity with the center’s curriculum); and (c) teachers who had received pre-service teacher training before joining the center but had not worked or studied overseas (ensuring their perspectives and practices were influenced by Chinese education rather than Western ideologies, aligning with the research questions). The participant group consisted of 15 female teachers and one male teacher, all of whom had worked in their respective centers for over a year. For participants in Cases 1–4, the mean and standard deviations (Mean ± standard deviations) for Enrollment Years are as follows: 2.88 ± 1.11, 2.25 ± 1.19, 2.00 ± 0.71, and 1.63 ± 0.25, respectively. To protect their anonymity, pseudonyms were used for all participants. A brief introduction of each participant is presented in Table 1.

Case 1: American-style early learning center

This center, guided by a member associated with the Asian Development Research Institute and the NAEYC, adopts a curriculum influenced by US early childhood education principles. Termed as the “three-dimensional comprehensive curriculum,” it encompasses physical, intellectual, musical, artistic, and literary elements, focusing on holistic child development with a strong emphasis on play. Teacher qualifications, particularly in music, dance, and English, are highly prioritized. All educators hold bachelor’s degrees but lack specific training in Developmentally Appropriate Practice (DAP) or American early childhood curriculum. The curriculum includes:

• Physical Class (0–8 years): Focused on classic American physical games, with variations involving parents and children, emphasizing nature-based development.

• Aesthetic Class (2–8 years): Offers over 300 materials, promoting experiential learning in music, dance, drama, literature, and drawing.

• Creative Class (0–8 years): Awarded the “Education Industry Award,” it nurtures multifaceted thinking and environmental awareness.

• Intelligence Exploration Class (0–8 years): Recognized for stimulating cognitive development, this class employs tabletop games to enhance various cognitive skills.

Case 2: Swedish-style early learning center

In the context of the Chinese educational landscape, this center adopts principles inspired by Karl Witt, placing a unique emphasis on utilizing tabletop games, colloquially referred to as “chess games” (which are actually various types of board games), to foster talent discovery and enhance hands-on learning experiences. These games are designed to support overall child development by engaging them in strategic thinking and problem-solving activities.

The center’s pedagogical approach, termed the “TCL teaching philosophy,” builds on the integration of three core elements: the teacher, the child, and the learning process. This approach aims to create a cohesive educational environment that involves not only educators and children but also parents, promoting a collaborative learning experience.

The curriculum is structured to cover seven fundamental developmental domains: knowledge, critical thinking, cultural norms, character building, psychological well-being, artistic expression, and physical education. It is delivered through a variety of classes tailored to different age groups:

• The DCB Class, designed for infants aged 6 months to 3 years, focuses on early language acquisition and socialization through interactive singing and dancing activities.

• The KT Class, for children aged 3–7 years, aims to bolster cognitive development and enhance critical thinking skills through engaging board games.

• The CCPA Class, also for the 3–7 age group, is dedicated to supporting children’s psychological and artistic growth, utilizing sand play as a medium for creative expression.

• The BCG Class, targeting the same age range, leverages chess and similar strategic games to develop cognitive abilities and social skills, emphasizing the value of strategic play in early learning.

Case 3: British-style early learning center

This center prioritizes holistic development over academic success, focusing on self-development, social–emotional literacy, resilience, and aesthetics. It aims to enhance logical thinking, creativity, and social skills through six core competencies: freedom, positive judgment, meta-learning, socialization, refining values, and self-awareness. The curriculum includes:

• Physical Class (8 months-3 years): Develops basic motor skills.

• Artistic Class (0–3 years): Promotes artistic skills through creative activities.

• Creativity Class (3–7 years): Encourages inventive thinking using various educational tools.

• English Classe (3–12 years): Follows the UK National Curriculum with innovative teaching methods.

Case 4: Australian-style early learning center

Based on Williams and Shellenberger’s pyramid of learning, the curriculum focuses on brain development, creativity, and music, aligning with children’s learning sensitivities. The three main strands are:

• Brain Development Class (0–3 years): Enhances sensory and physical skills through structured activities.

• Creative Development Class (2–5 years): Encourages creativity through food and globe art.

• Music Class (0–3 years): Aims to develop rhythm, self-expression, and music appreciation.

In all cases, while the curriculum draws from international models, the implementation is predominantly managed by local educators, with limited direct training from Western experts.

Data collection and analysis

Interviews with 16 participants were conducted, each lasting about 45 min. These interviews probed into the teachers’ perceptions of play, alongside gathering background information such as age, gender, educational qualifications, and prior experiences in early childhood education (see Table 2).

The analysis involved three stages:

• Initial Coding with NVivo 10: NVivo 10 software facilitated initial coding. The software processed interview transcripts and field notes, automatically categorizing raw data into preliminary topics. Through inductive coding, guided by our research questions and theoretical framework, these topics were continuously compared and contrasted, leading to the emergence of basic patterns.

• Within-Case Analysis: Following the six-phase approach of Clarke et al. (2015), the analysis began with familiarization with the data, generating initial codes, and immersing in each transcript. This led to the identification and refinement of patterns relevant to the research questions into meaningful themes, drawing upon theories of globalization, post-colonialism, and cultural dimensions.

• Cross-Case Analysis: This phase involved examining similarities and differences across cases, focusing on commonalities. The themes identified were compared across different cases, prioritizing findings in relation to their relevance to the research questions. This facilitated the development of tentative assertions to deepen our understanding of Chinese teachers’ perceptions of play.

Findings

To explore teachers’ perspectives on play, specific questions were posed, including their definition of play, initial thoughts on the term, and its role in children’s learning and development, such as: “Could you please share with me your definition of play?,” “When it comes to the term ‘play’, what comes to your mind?,” and “What role do you think play has in children’s learning and development?.” The discussions revealed both shared and unique insights, emphasizing the significance of enjoyment, autonomy, interactive experiences, and organic learning. These key themes, as outlined in Table 3, underscore the multifaceted nature of play in educational settings.

Interestingly, when inquiring about specific questions from Table 2, such as questions 12–16, most participants felt that their perceptions of play were influenced by local culture and their own backgrounds, even within Western-style centers. Although they work in the specific center for at least 1 year, they have lived in China for more than 20 years, where they are immersed in Chinese culture. Furthermore, they did not receive training specific to other countries’ philosophies or education. This suggests a blend of cultural and personal factors shaping their understanding of play. Teachers in domestic early childhood education centers indeed have their understanding of play shaped by their cultural context and personal educational and professional backgrounds. This interplay aligns with the theory of globalization, which suggests that local practices and global influences converge, leading to a nuanced interpretation of concepts like play in educational settings.

Case 1: In this case, teachers believed that the global influence of Western philosophy on early childhood education shaped their perception of play. They categorized play into two types: in-class play and out-of-class play. Extracurricular play or free play, was seen as having specific characteristics, including happiness, child autonomy, and interaction.

Case 2: Teachers in this case divided play into classroom and extracurricular contexts. “Free play” was associated with having fun and enjoyment, yet they also recognized its educational benefits in facilitating natural learning processes. Teachers in this center stressed the importance of enjoyment, child autonomy, play versus game distinctions, and self-expression.

Case 3: Teachers in this case asserted that play defies a single definition and can vary among individuals. They echoed the appreciation for the primary benefits of enjoyment and child autonomy seen in the previous cases. Play, for them, was a means to nurture children’s curiosity, holistic development, and spontaneous learning.

Case 4: Similar to previous cases, participants in this center emphasized the significance of happiness and child autonomy in their concept of play. They believed children should have the freedom to choose their play activities independently. Play, for them, encompassed various activities driven by children’s interests. Three key characteristics of play were identified, emphasizing that nearly anything a child does could be regarded as play. Moreover, they emphasized that children naturally learn through play, which should align with real-world experiences. Play served as a spontaneous outlet for processing emotions and engaging in various activities. They emphasized the value of integrating real-world experiences into play, whether through role-playing, storytelling, or artistic creation.

As presented in Table 3, several common themes emerged across these cases, underlining the importance of happiness, child autonomy, interactions, and spontaneous learning in their perceptions of play.

Happiness and fun in play

In the perspective of nearly all participants, play was synonymous with “free play,” characterized by delight and enjoyment, driven by intrinsic motivation without explicit external objectives, and characterized by active and engaging participation. Across all four cases, teachers unanimously agreed that play is fundamentally about having fun, emphasizing that anything that brings joy and happiness to children can be considered play. Happiness and fun were deemed paramount aspects of play, with participants valuing the positive emotions, especially happiness, that children experience during play.

For example, from case1, Helen posits that play is defined by pleasure, suggesting that a child’s happiness is the essence of play. JoJo equates playing to having fun, noting that children are in a state of play continuously. Sunny emphasizes that play extends beyond structured activities, encompassing any action that brings joy to children, even reading outside of class. WenWen broadens the definition further, stating that any activity that makes a child happy qualifies as play, happening anytime and anywhere. From case 2, Abby emphasized the importance of happiness in play, stating, “happiness that is created in play is significant for human beings, especially for children.” She believes that personal joy is paramount, and without enjoyment in activities, one cannot be truly happy. Lynn expanded on this idea by advocating for play as a medium to sustain happiness and fun, which she considered crucial for a better life. She stressed the value of children’s happiness in play and the role of adults in amplifying this joy by engaging with and encouraging children during play, suggesting that such shared joy can enhance the play experience and keep children focused and involved. As Anson, Cherish, Nemo, and Rose from case 4 mentioned, play encompasses a wide range of activities that bring joy to children, whether it’s playing baseball with friends, climbing trees, enjoying outdoor time, or even observing the world around them. Essentially, any activity that children engage in with joy can be considered play.

In summary, the participants shared a consensus that happiness and fun are fundamental components of play. They stressed the importance of creating a joyful environment for children and allowing them the freedom to engage in activities that bring them happiness and enjoyment.

Child autonomy in play

In all cases, the teachers acknowledged the importance of child autonomy as a defining characteristic of play. They agreed that allowing children the freedom to make choices was crucial. However, there were slight variations in their perspectives.

In Case 1, child autonomy was explored at multiple levels. This included granting children the freedom to make choices, recognizing their readiness to engage in play, and avoiding imposing strict teaching goals or learning objectives during playtime. This approach aligned with Bruce (1991) belief that children should have the ability to choose what they want to do, how they want to do it, and when to transition to a different activity during play. Importantly, it was noted that even activities resembling work, such as reading and writing, could be considered play if children engaged in them willingly.

Teachers in the other cases also emphasized child autonomy but placed a stronger focus on understanding children’s interests and providing options for them to select from. This approach was rooted in recognizing children’s perspectives, interests, needs, desires, individual experiences, and likes and dislikes. Participants in Cases 2, 3, and 4, such as Alice, Cindy, and Lynn, stressed the importance of children’s willingness to participate in play. They believed that teachers should facilitate an environment where children could freely choose from a set of options.

Some participants highlighted that although children should have choices, they may not always have complete control over their activities. Instead, teachers could present a limited number of options to encourage children to develop self-control and decision-making skills. This perspective aligned with the concept of “modeled play,” where teachers minimally intervene, present various objects for exploration, demonstrate different approaches, and allow children to decide how to engage with them.

Abby: Teachers, particularly Chinese teachers, tend to make decisions for their students. However, it's essential to remember that children need options. This doesn’t mean children should always make every decision themselves. Instead, we should provide opportunities for them to choose. Some children may need encouragement to think independently and make decisions, while others naturally prefer to choose what and how to play. In either case, we must demonstrate our respect and trust in their choices.

Mia: Giving children choices empowers them, allowing them to feel a sense of control over their actions, how they do things, and where they do them. This is a significant developmental milestone, as the ability to make appropriate decisions is a crucial skill that children can carry with them throughout their lives. It’s important to remember that sometimes choosing not to do something is also a valid choice.

Cindy: Children should be the ones creating the rules, deciding how long they want to play, and choosing the direction of their play. When a teacher instructs students to do something, they have no choice but to complete it.

The significance of interactions in play

In all the cases discussed, the teachers emphasized the vital role of interactions, whether with people, objects, or the environment, in the context of play-based learning.

In Case 1, teachers emphasized the significance of interactive experiences, especially in the context of human relationships, within playful environments. They highlighted the necessity of creating playful opportunities for children to interact with peers, thereby bolstering their sense of security and social competencies. An example provided to illustrate this point was the act of shaking hands, which, despite the variety of customs across different cultures, universally represents politeness and civility. Introducing children to the practice of shaking hands within play settings was advocated as a method to nurture their interpersonal skills, demonstrating how structured play activities can serve as a conduit for teaching valuable social norms and behaviors.

Case 3 participants emphasized the significance of interactions, especially with objects and the surrounding environment. They believed that children could connect their personal beliefs to their understanding of the world. Through such connections, children could explore the functions of the world and objects within it. Play was viewed as the primary way children made sense of their surroundings, discovering wonders, investigating object properties, and gaining an understanding of how the world functions and evolves. Exploring objects and their environment during play often led to new discoveries.

Case 4 teachers regarded real-life experiences as a crucial element of play. They highlighted the importance of integrating children’s real-life experiences into play to help children make sense of their lives. Using tangible objects like food, fruit, and animals in play was considered motivating and engaging.

The following are some examples:

Jojo: Teachers play a significant role in creating opportunities for children to explore through interactions, be it with others or their environment. This interaction helps in developing problem-solving skills by allowing children to express their emotions and feelings. Being around others, whether adults or peers, contributes to children's sense of security and social skills. Encouraging children to greet strangers by shaking hands, or introducing activities like our 'shaking hands, ' can be beneficial.

Sunny: Children find joy in conveying ideas through sound effects, body language, and conversation, which facilitates experiential learning. They should engage with their peers to discover new and unique things and should also have opportunities to express themselves to adults. Interactions, whether with peers or adults, enable children to learn about others’ perspectives and feelings, fostering the ability to consider different viewpoints. Additionally, interactions with objects were recognized as a crucial aspect of play.

Spontaneous learning in play

The concept of spontaneous learning in play was seen as a crucial element by teachers in both Case 3 and Case 4. They believed that young children could learn spontaneously and freely through play, with a particular focus on the development of creativity, imagination, communication, and problem-solving skills.

In Case 3, Alice provided an example to illustrate how play, particularly block building, could foster problem-solving skills. Children, through multiple attempts, figured out how to construct a stable house by stacking blocks of various shapes and sizes in precise ways. This process of trial and error allowed them to develop critical thinking and problem-solving abilities.

In Case 4, Cherish emphasized that socio-dramatic play enabled children to learn about acceptance, understanding of others, and social responsibilities. Children could also use this type of play to explore and learn how to address social issues by pretending to take on roles like a postman, a salesperson, or a waiter.

While Case 2 did not explicitly describe play as a process of spontaneous learning, they recognized the educational value of activities like role play and sand play. These activities were believed to enhance children’s self-expression, imagination, and self-confidence. For instance,

Alice: Play, when examined closely, offers more than just growth for children. It also facilitates spontaneous learning. Exploring and discovering new materials and experiences lead to the formation of new neural connections. Children are learning even when they are unaware of it. For instance, when children engage in block play, they are essentially building a house out of wooden blocks. They experiment with stacking blocks of varying sizes and shapes. They might use a rug as a surface, stack smaller blocks on top of larger ones, or place rectangular blocks on triangular ones. The house might collapse, but through these experiments, they generate fresh ideas. After several attempts, they may discover that smaller blocks are more stable when placed atop larger blocks. They might learn to place larger blocks at the bottom and experiment with different shapes and sizes to create taller structures. The beauty of this is that they don't always need adult assistance; they learn through play independently.

Cindy: I came across a book titled “The Power of Play: Learning What Comes Naturally,” which stated that learning can occur at any time and in any place during children’s play. Children can learn through freely chosen and unplanned play. For instance, children can learn to dance even if they don’t attend a formal dance class; they can dance to random music. It’s no surprise that a balance of child-initiated and teacher-initiated activities can facilitate learning. When children engage in activities like running races or playing with different types of balls, they stimulate their large motor skills. They can also enhance creativity and imagination by inventing stories or engaging in role-play. Furthermore, social skills can benefit from group activities or games.

The consensus across these cases was that play provides a fertile ground for spontaneous learning across various domains, contributing to children’s holistic development.

Conclusion and reflections

This study has illuminated the diverse yet interconnected perspectives of early childhood education teachers on the concept of play, underscoring its critical role in fostering happiness, fun, and autonomy among children. The consensus among participants is that play should be a source of joy, driven by intrinsic motivation, and provide a platform for engaging exploration. It is perceived as the educators’ duty to cultivate an environment that nurtures positive emotions during play without imposing undue interference, thereby respecting and promoting child autonomy.

Teachers highlighted the significance of allowing children the freedom to select their activities and engage in play at their own pace, free from strict educational objectives. This autonomy is crucial in enabling children to develop self-regulation and decision-making capabilities. The study also underlines the importance of interactions—be it with peers, adults, objects, or the environment—in enriching the play experience and contributing to the holistic development of social skills, cultural understanding, and emotional security.

A key finding is the natural learning that occurs through play, where creativity, imagination, communication, and problem-solving skills flourish in an unstructured setting. The distinction between free play and pedagogical play emerged, revealing variations in the perceived roles of play in and outside the classroom setting and the adaptive roles of teachers within these contexts.

Cultural nuances, particularly the influence of Chinese cultural values emphasizing academic achievement, were observed to shape the teachers’ understanding and implementation of play-based learning. This cultural backdrop provides a unique lens through which the concept of play is interpreted. At the beginning, considering that teacher beliefs are developed through a myriad of experiences over the course of their lives including social interactions with other individuals (i.e., parents, family, children, colleagues, through training, etc.) as well as personal practice (Richards and Lockheart, 1994), there is no denying the fact that teachers’ understanding is normally established by the time they enter their training programs (Sanger and Ogusthorpe, 2011). Therefore, both pre-service training and in-service training, as well as their individual learning experiences have shaped teachers’ understanding of play, and shaped how they interpret and respond to knowledge and experience in terms of the way of teaching. The teachers needed to adjust their planning and interpretation of the classes to fulfill the parents’ expectations, and the center needed to satisfy the clients—parents by highlighting their adherence with the Western pedagogy and philosophy and how they differ from other centers to keep themselves more competitive in this market. Last but not least, the trend of globalization in the field of early childhood education, which in a way brings about the cultural conflict and differences highly impacted Chinese teachers’ beliefs. As a consequence, the teachers across the four centers have taken new ideas with the consideration of the information they obtained by self-learning or in-service training in order to make the class developmentally and culturally appropriate (Woodhead, 1996, 1998; National Association for the Education of Young Children, 1997).

While these findings offer valuable insights, it is important to acknowledge the study’s scope and the contextual factors that might influence its broader applicability. The perspectives captured, derived from a purposive sample within a specific cultural setting, offer a snapshot rather than a comprehensive overview of early childhood educators’ views on play. Future explorations could extend this work by examining the interplay between these perspectives and actual classroom practices across varied cultural and educational landscapes.

This study’s reflections on the essence of play in early childhood education contribute to a deeper understanding of its multifaceted role in child development, emphasizing the need for environments that honor children’s autonomy, creativity, and innate capacity for learning.

Expanding on these conclusions to consider globalization, we can delve deeper into how global educational trends and ideologies shape ECE practices in China. The adoption of Western-style play-based learning reflects a global shift toward child-centered education, yet it is intertwined with China’s cultural emphasis on academic achievement. This blend creates a unique educational landscape where traditional and global educational philosophies coexist. Understanding this dynamic can provide insights into the evolving nature of early childhood education in a globalized context, offering a broader perspective on how cultural and societal influences shape educational practices.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Guangzhou University Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

XW: Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization. PY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Funding acquisition, Software, Writing – review & editing. TQ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Project administration, Visualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Al-Rodhan, N. R., and Stoudmann, G. (2006). Definitions of globalization: a comprehensive overview and a proposed definition. Prog. Geopolit. Implic. Glob. Transnatl. Secur. 6, 1–21.

Badzis, M. (2003). Teachers’ and parents’ understanding of the concept of play in child development and education. Doctoral dissertation, Coventry: University of Warwick.

Bai, L. (2005). Children at play: a childhood beyond the Confucian shadow. Childhood Glob. J. Child Res. 12, 9–32. doi: 10.1177/0907568205049890

Bennett, N., Wood, L., and Rogers, S. (1997). Teaching through play: teachers thinking and classroom practice. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Bergen, D. (2014). Foundations of play theory. The SAGE handbook of play and learning in early childhood, 9–21. doi: 10.4135/9781473907850.n2

Britto, P. R., Engle, P. L., and Super, C. M. (2013). Handbook of early childhood development research and its impact on global policy, New York, NK: Oxford University Press.

Broadhead, P. (2004). Early years play and learning: developing social skills and cooperation. London: Psychology Press.

Bruce, T. (1991). Time to play in early childhood education. Edward Arnold, London: Hodder & Stoughton.

Burbules, N. C., and Torres, C. A. (2000). Globalization and education: critical perspectives. New York, NY: Routledge.

Cheng, D. P., and Wu, S. (2013). “Serious learners or serious players? Revisiting the concept of learning through play in Hong Kong and German classrooms” in Varied perspectives on play and learning: theory and research on early years education. eds. O. F. Lillemyr, S. Dockett, and B. Perry (Charlotte, NC: IAP Information Age Publishing), 193–212.

Comenius, J. A. (1632). Didactica Magna. Translated into Chinese by Fu, R. Beijing: People’s Education Press. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/7516198/Jan_Amos_Comenius_Didactica_Magna

Crabb, M. (2010). Governing the middle-class family in urban China: educational reform and questions of choice. Econ. Soc. 39, 385–402. doi: 10.1080/03085147.2010.486216

Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dadich, A., and Spooner, C. (2008). Evaluating playgroups: an examination of issues and options. Austr. Commun. Psychol. 20, 95–104.

Duncan, J. (2009). Intentional teaching: early childhood education educate. New Zealand: Ministry of Education.

Edwards, S., and Cutter-Mackenzie, A. (2013). Pedagogical play types: what do they suggest for learning about sustainability in early childhood education? Int. J. Early Child. 45, 327–346. doi: 10.1007/s13158-013-0082-5

Epstein, A. S. (2007). The intentional teacher: choosing the best strategies for young children's learning. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Fleer, M. (2011). ‘Conceptual play’: foregrounding imagination and cognition during concept formation in early year's education. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 12, 224–240. doi: 10.2304/ciec.2011.12.3.224

Froebel, F. (1887). The education of man. (W. N. Hailmann, Trans.). D Appleton & Company. doi: 10.1037/12739-000

Groos, K., and Baldwin, J. M.. (Ed.). (1898). The play of animals. (E. L. Baldwin, Trans.). D Appleton & Company. doi: 10.1037/12894-000

Gaskins, S. (2014). “Children's play as cultural activity” in The SAGE handbook of play and learning in early childhood. Eds. L. Brooder, M. Blaise, and S. Edwards, London: SAGE Publications Ltd. Available at: https://uk.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-binaries/62655_Brooker__Ch3.pdf

Huizinga, J. (1950). Homo Ludens: a study of the play element in culture. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Kagan, S. (1990). The Structural Approach to Cooperative Learning. Educational Leadership, 47, 12–15. Available at: https://files.ascd.org/staticfiles/ascd/pdf/journals/ed_lead/el_198912_kagan.pdf

Li, H., Wang, X. C., and Wong, J. M. S. (2011). Early childhood curriculum reform in China. Chinese Education and Society, 44, 5–23. doi: 10.2753/CED1061-1932440601

Latta, M. M., and Field, J. C. (2005). The flight from experience to representation: seeing relational complexity in teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 21, 649–660. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2005.05.004

Locke, J. (1693). “Some thoughts concerning education” in English philosophers. ed. C. W. Eliot , vol. 37 (New York, NY: Methuen)

McAuley, H., and Jackson, P. (1992). Educating young children: a structural approach David Fulton Pub.

McFarland-Piazza, L., Lord, A., Smith, M., and Downey, B. (2012). The role of community-based playgroups in building relationships between pre-service teachers, families and the community. Australas. J. Early Childhood 37, 34–41. doi: 10.1177/183693911203700206

Meckley, A. (2002). Observing children's play: mindful methods. International Toy Research Association, London.

Morris, S. R. (1998). “No learning by coercion: paidia and paideia in platonic philosophy” in Play from birth to twelve and beyond: contexts, perspectives, and meanings. eds. D. P. Fromberg and D. Bergen (New York, NY: Garland), 109–118.

National Association for the Education of Young Children (1997). Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs. rev. Edn. Washington, DC: Cambridge: Pembroke Pub Ltd.

Niu, C. (2023). Research on play-based kindergarten curriculum reform in China: based on the analysis of three typical play modes. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 31, 401–418. doi: 10.1080/09669760.2023.2168520

Owen, C., and Moss, P. (1989). Use of preschool daycare and education, 1979-86. Child. Soc. 3, 296–310.

Pence, A., and Shafer, J. (2006). Indigenous knowledge and early childhood development in Africa: the early childhood development virtual university. J. Educ. Int. Dev. 2:3.

Postman, N., and Weingartner, C. (1969). Teaching as a subversive activity. New York, NY: Delacorte.

Preschool Education Law of the People’s Republic of China (2023). Available at: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/s5147/202308/t20230829_1076670.html

Rao, N., and Li, H. (2009). “Eduplay”: Beliefs and Practices Related to Play and Learning in Chinese Kindergartens, in Play and Learning in Early Childhood Settings. International Perspectives on Early Childhood Education and Development, Eds. Pramling-Samuelsson, I., Fleer, M. vol 1. Springer, Dordrecht. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-8498-0_5

Richards, J. C., and Lockhart, C. (1994). Reflective teaching in second language classrooms. The Modern Language Journal, 79, 121. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511667169

Robertson, R., and White, K. (2007). What is globalization? In G. Ritzer (Ed.), The Blackwell companion to globalization (pp. 54–67). Malden, MA: Blackwell. doi: 10.1002/9780470691939.ch2

Rogers, S. (2011). Rethinking play and pedagogy in early childhood education: concepts, contexts and cultures. London: Routledge.

Rogers, S., and Evans, J. (2008). Inside role play in early childhood education: researching young children's perspectives. London: Routledge.

RYB Education Institute . (2023). The footsteps of RYB education institute. Available at: http://www.rybbaby.com/about-12082.html

Sanger, M. N., and Osguthorpe, R. D. (2011). Teacher education, preservice teacher beliefs, and the moral work of teaching. Teaching and teacher education, 27, 569–578. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.10.011

Sosinky, L., Lord, H., and Zigler, E. (2007). For-profit/non-profit differences in center-based child care quality: results from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development study of early child care and youth development. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 28, 390–410. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2007.06.003

Statham, J., and Brophy, J. (1991). The role of playgroups as a service for preschool children. Early Child Dev. Care 74, 39–60. doi: 10.1080/0300443910740104

Stewart, N., and Pugh, R. (2007). Early years vision in focus, part 2: exploring pedagogy. Shropshire County Council.

Strandell, H. (2013). After-school care as Investment in Human Capital-from Policy to practice. Child. Soc. 27, 270–281. doi: 10.1111/chso.12035

Tikly, L. (1999). Post-colonialism and comparative education. Int. Rev. Educ. 45, 603–621. doi: 10.1023/A:1003887210695

Tobin, J., Hsueh, Y., and Karasawa, M. (2009). Preschool in three cultures revisited [electronic resource]: China, Japan, and the United States/Joseph Tobin, Yeh Hsueh, and Mayumi Karasawa. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Vaughan, J. (1993). Early childhood education in China. Childhood Education, 69:, 196–200. doi: 10.1080/00094056.1993.10520931

Vygotsky, L. S. (1967). Play and its role in the mental development of the child. Sov. Psychol. 5, 6–18. doi: 10.2753/RPO1061-040505036

Wang, X., and Lam, C. B. (2017). An Exploratory Case Study of an American-Style, Play-Based Curriculum in China. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 31, 28–39. doi: 10.1080/02568543.2016.1243175

Wood, E. (2010). “Developing integrated pedagogical approaches to play and learning” in Play and learning in the early years. eds. J. H. Broadhead and E. Wood (London: SAGE), 9–26.

Wood, E. A. (2014). Free choice and free play in early childhood education: troubling the discourse. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 22, 4–18. doi: 10.1080/09669760.2013.830562

Wood, E., and Attfield, J. (2005). Play, learning, and the early childhood curriculum. London: Paul Chapman.

Wood, L., and Bennett, N. (1997). The rhetoric and reality of play: teachers' thinking and classroom practice. Early Years 17, 22–27. doi: 10.1080/0957514970170205

Woodhead, M. (1996). In Search of the Rainbow: Pathways to Quality in Large-Scale Programmes for Young Disadvantaged Children. Early Childhood Development: Practice and Reflections Number 10. Bernard van Leer Foundation, PO Box 82334, 2508 EH, The Hague, Netherlands (Single copies free of charge).

Woodhead, M. (1998). ‘Quality’in Early Childhood Programmes—a contextually appropriate approach. International Journal of Early Years Education, 6, 5–17. doi: 10.1080/0966976980060101

Woodhead, M., and Streuli, N. (2013). Early education for all: Is there a Role for the Private Sector? in Handbook of early childhood development research and its impact on global policy. Eds. Britto, P., Engle, P., and Super, C. New York, NK: Oxford University Press.

Yan, Z. L. (2009). Colonialism and post-colonialism in preschool education. Stud. Presch. Educ. 4, 27–31. doi: 10.13861/j.cnki.sece.2009.04.007

Keywords: multiple-case study, early childhood educator, teacher, play, globalization

Citation: Wang X, Ye P and Qiao T (2024) Free play and pedagogical play: a multiple-case study of teachers’ views of play in Chinese early learning centers. Front. Educ. 9:1359867. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1359867

Edited by:

Evi Agostini, University of Vienna, AustriaReviewed by:

Theresa Hauck, University of Vienna, AustriaAstrid Wirth, University of Vienna, Austria

Copyright © 2024 Wang, Ye and Qiao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xinxin Wang, Y3ludGhpYS53YW5nQGN5bnRoaWEtZWR1LmNvbQ==; Tianqi Qiao, cWlhb3RpYW5xaUBlLmd6aHUuZWR1LmNu

Xinxin Wang

Xinxin Wang Pingzhi Ye

Pingzhi Ye Tianqi Qiao

Tianqi Qiao