- University of Limpopo, Mankweng, South Africa

Preparing subject teachers for understanding and implementation of curriculum and Assessment policy statement in schools has become a concern in nations as a way to strive for excellence. Yet, there is a little known about the understanding of curriculum policy than its effectiveness in the school. This study explored teacher understanding of Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) document implementation. The study employed a qualitative approach, utilizing a case study research design. The interpretivism paradigm was applied to gain an in-depth understanding secondary of teachers’ perspectives on the implementation of the CAPS. The population of the research study consisted of 100 teachers in Capricorn District, and the sample of this study consisted of ten (10) teachers who were selected using a convenient sampling technique. Data was collected using individual, semi-structured interviews and focus group interviews, and was analyzed using thematic data analysis method. The study concluded that internal and external workshops could serve the purpose of implementing the CAPS document in the classroom. In addition, movable resources, for better implementation of the CAPS document in the classroom. Lastly, for researchers, these findings may help with further research on strategies to be implemented in schools to encourage constant use of the CAPS document. The unique contribution of this article to existing research on the classroom implementation of CAPS guidelines is to address the gap identified by ineffectiveness of the subject policy to the secondary teaching.

1 Introduction

Teachers work by a multitude of policies on different levels, not only national but also of the local policies in the landscapes of the diverse schools with international influences. Mølstad et al. (2018) assert that multiple policy put demands on teachers who must serve as interpreters and implementers of the educational policies whose practices are crucial to learners learning outcomes. However, in the international perspective, curriculum policy is used to make practices and bring competition between schools with different pedagogical profile to improve the overall educational system (Dieudé and Prøitz, 2024). Researcher like Apple (2018) argue that policy guides teachers on how to transfer and enhance the knowledge about practices in the organization. In Australia, a study by Watt (2020) found that Queensland uses the Australian curriculum as a base, where teachers develop their own teaching and learning programs to respond to learners’ needs. In Tanzania, Ishemo (2019) found that teachers in the country are now implementing Outcome-Based Curriculum (OBC), which supports a learner-centered approach to help learners acquire significant or required knowledge and skills to help the country improve its national examination quality results. Nationally, policy such as curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) was developed for each subject to replace subject statements, learning program guidelines, and subject assessment guidelines in Grades R–12 (Alex and Mammen, 2014). This document has been designed in order to guide the teaching and learning of teachers in the school context. South Africa has introduced a number of educational reforms, such as Outcome-Based Education (OBE), the National Curriculum Statement (NCS), and CAPS (Bantwini, 2010). Factors such as limited resources, teacher understanding and readiness, alignment with learners’ needs, and assessment practices contributed to the challenges faced in achieving the desired outcomes of the document (Fomunyam, 2016). Such information is significant in South African schools.

2 Curriculum and assessment policy statement

South Africa has had numerous curriculum reforms that were intended to level the past inequalities and injustices caused by apartheid policies (Gumede and Biyase, 2016). Van Der Nest (2012) argues that a change in curriculum is a necessity for the functionality of teachers. However, instead of better implementation of the CAPS to improve its effectiveness in the classroom, some teachers might tend to focus more on the changed content knowledge. Whereas, they have to deal with a change in educational knowledge, which results in numerous challenges concerning the effective implementation of CAPS as the amended curriculum.

The implementation of CAPS was a significant step toward achieving educational outcomes between resource- and under-resourced schools (Maharaj et al., 2016). The CAPS brings about important changes in the plan of teaching, methods of assessment, and time frame for the classroom from grades R–12. However, the challenge with regard to the teachers’ understanding and Implementation of its effectiveness in the classroom is still challenging for numerous teachers in the field of education. Nevenglosky (2018) argues that teachers lack the theoretical knowledge and familiarity with the principles that inform the implementation of curriculum change. The change brought about affects the implementation of its effectiveness in South African schools.

With regard to the present study, the comprehensive and concise policy documents that replace NCS Grade R–12 were introduced (Department of Basic Education, 2011). This curriculum was aimed at replacing the NCS in order to improve the quality of teaching and learning. Secondly, to provide teachers with a clear understanding of topics that must be covered in each subject (Mbatha, 2016). However, even though it had proper intentions with regard to teaching and learning in South African schools, the implementation of CAPS by teachers in the classroom is still not satisfactory.

3 Teacher’s policy implementation

To reveal more perspective on the CAPS implementation in the classroom and toward teaching and learning. Ayua (2017) argues that effective planning by teachers and understanding of the CAPS guidelines contribute to teaching and learning, which allows teachers to focus on the objectives or goal of teaching, but teachers still fail to understand and comply with the requirements. Scholars like Yang and Li (2018) argue that classroom planning is more significant than any other level of planning since it emanates from curriculum planning that makes an impact on the learners in the classroom.

Chaudhary (2015) asserts that the influence of teachers in curriculum implementation cannot be argued or debated in the school context. Killen (2015) further argues that teachers must ensure that their structure of learning activities guides and leads learners to understand the content taught in the classroom. Without any form of good understanding, teachers are likely not to implement the desired curriculum (Galvan and Coronado, 2014). Beside the provision of resources to the subject teachers, training and support that is significant to the school do not reach teachers, and this makes the teachers not adapt to a change and teach content as stipulated by the policy document (Tus, 2020). Teachers’ attitudes, values, and beliefs play a major role, and teachers need to be transparent (Chowdhury, 2018). Without transparency maintained about the understanding of curriculum, teachers are likely not to feel comfortable teaching certain topics because it clashes with their values and beliefs (Sepadi, 2018). This entails that implementation will never be fruitful in the teaching and learning context as teachers fail to comprehend the subject content of the curriculum and assessment policy.

Thaanyane and Thabana (2019) further argues that successful implementation of the policy document implies that teachers have to understand, interpret, and implement it as intended to support its implication. In addition, the theoretical underpinnings and classroom application of the changed curriculum must be well understood. The educational system has experienced many changes in the curricula in an attempt to address challenges related to inequality and a lack of quality within the education system attributed to the apartheid dispensation (Ogunniyi and Mushayikwa, 2015). The transition from apartheid to democracy was quickly accompanied by a series of curriculum changes, including the 2005 curriculum and most recently the CAPS, which brought some changes to the classroom (Nkosi, 2014).

Curriculum implementation requires the practice prescribed by the official program of academic studies, which translates CAPS into practice for teachers in the classroom and learners in South African schools (Mandukwini, 2016). Chaudhary (2015) argues that curriculum policy implementation occurs when learners acquire planned or intended experiences, knowledge, skills, ideas, and attitudes that aim to enable those learners to participate and function effectively in society. However, Mishra (2020) argue that implementation of curriculum is done by individual teachers in the classroom by teaching learners as they learn. The implementation requires adjustments to personal habits, ways of behaving, learning space, and existing curricula and schedules (Tomlinson, 2014).

In addition, curriculum implementation in the classroom is concerned with how best teachers can understand its principles in order to meet the teaching and learning needs of the learners (Tyler, 2013). This concern is echoed in the South African classroom, which represents learners of different subjects and learning materials. Tshidaho and Otukile-Mongwaketse (2018) argues that this curriculum brought challenges such as poor initial orientation of the new approach, overly complicated terminologies, and limited resources. The implementation challenges, such as outcomes, are open to different policy interpretations, and OBE was not addressing the coherence of the subject content, sequence, and progression of the learners (Richards, 2013).

The purpose of this brief literature review on the state of knowledge on the topic was to backtrack the moments and review the key perspective of the study that dominated toward the underlying assumptions in order to reconceptualise the theoretical and methodological approaches for curriculum implementation.

4 Theoretical framework

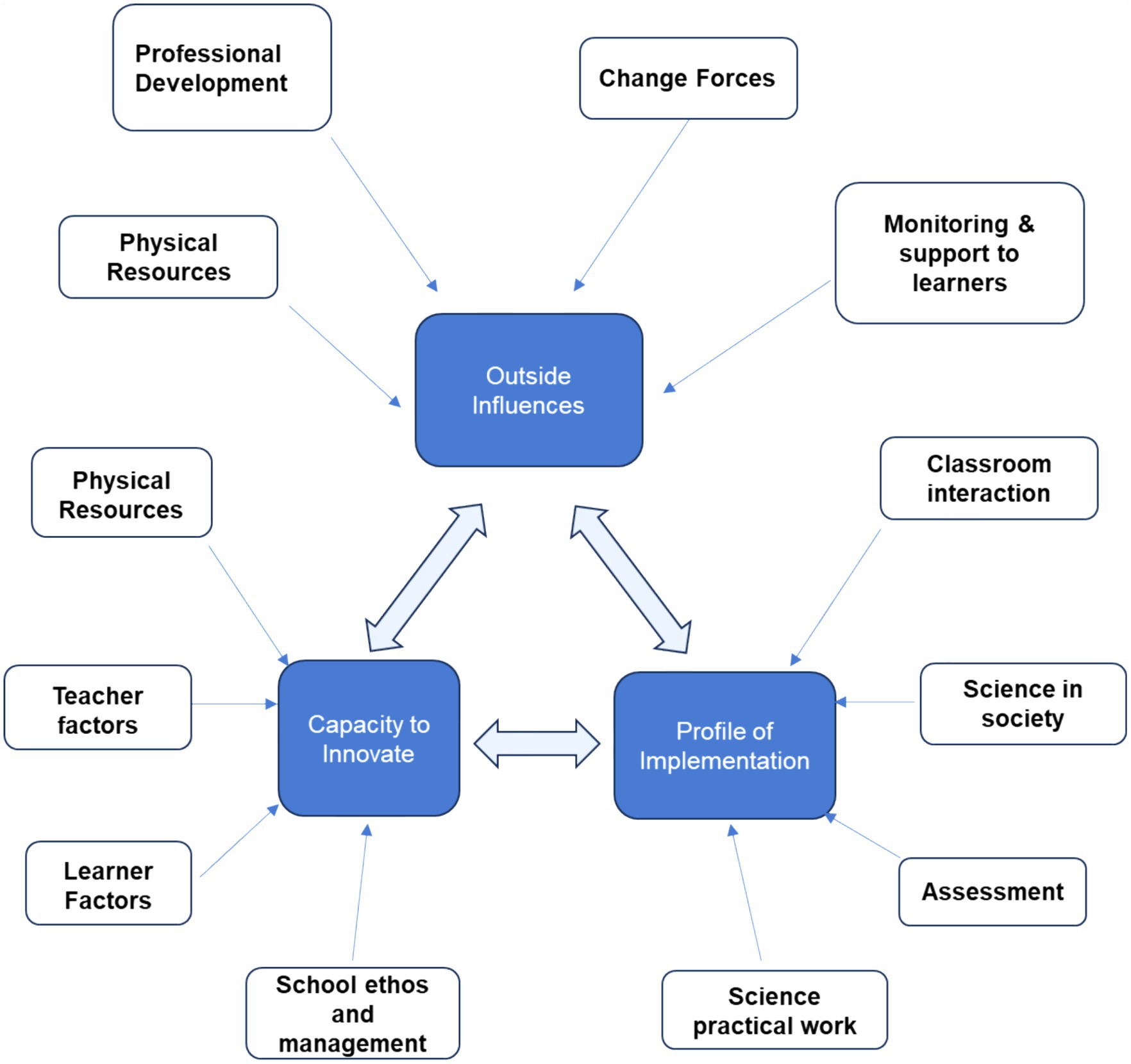

To gain a better understanding of the implementation of the CAPS document in the classroom, we applied the theory of curriculum implementation by Rogan and Grayson (2003) in an attempt to dwell more on the implementation of the curriculum in South African schools. This theory was developed to improve the previous models of curriculum implementation, as they were unclear about the nature of curriculum implementation (Mathura, 2019). Rogan and Grayson's (2003) theory of curriculum implementation is intended particularly for low- to middle-income countries, and it fits well with the South African context because of the new curriculum, which embraces all the South African races and cultures introduced. With the previous curriculum, it was more focused on gaining knowledge, while the current curriculum focuses more on a learner being in totality, where knowledge and skills are emphasized (Juliani, 2014). Moreover, the people who are supposed to implement curriculum, such as teachers in the classroom, are still trying to come up with the best or proper strategy for better implementation, leading to better academic performance (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Theoretical framework by Rogan and Grayson (2003).

This theory is referred to as a theory of curriculum implementation because it is about how teachers implement a new curriculum and factors that influence the way it is implemented in the school context (Palestina et al., 2020). Literature has proven that the chosen theoretical framework is relevant to the curriculum implementation in science education and the context of low-to-middle-income countries like South Africa (Rogan and Aldous, 2005). This framework draws from school development, educational change, and science education literature in order to develop three constructs and their sub-constructs. The main three constructs as components of the theory are the profile of implementation (in the classroom), capacity to support innovation, support and outside agencies on which the theory is based.

5 Research methodology

We adopted a qualitative research approach, employing a case study research design as recommended by scholars such as Creswell and Poth (2016). They describe the research approach as the step used to acquire and analyze the data. The use of a qualitative approach was the most appropriate technique intended to comprehend teachers’ experiences in their daily lives with regard to their understanding of the CAPS implementation in the classroom.

5.1 Sampling

A sample number of 10 teachers for all teaching subjects in secondary schools was conveniently selected from a population of 100 teachers from the Limpopo Provincial Department of Education. The teachers sampled were recruited from Capricorn District in the Limpopo Province Department of Education. In qualitative research, the researcher recruits’ participants who provide rich and deep data to understand the phenomenon studied, not the volume of numbers involved (Moser and Korstjens, 2018). In the present study, the researcher selected participants based on the data required for the phenomenon. The researcher chose secondary school because it is where she works and participants are easily accessible. The decision was made with the explicit purpose of obtaining possible information to answer a research question.

5.2 Data collection

Data was collected through individual semi-structured interviews and focus group interviews conducted in the schools. The choice of data collection instruments in this research study was not arbitrary, random, or automatic, as emphasized by Cohen et al. (2018). Instead, it involved a deliberate and thoughtful process, considering the appropriateness of the instruments to generate the intended results. The selection of individual semi-structured and focus group interviews as data collection instruments yielded information about teachers’ understanding of CAPS implementation. Moser and Korstjens (2018) describes data collection as the process of collecting the necessary information on a research issue. In this study, data was triangulated with individual semi-structured interviews and focus group interviews. Furthermore, the present study used different approaches and strategies for collecting data.

5.3 Procedures for data collection

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Turfloop Research Ethics Committee (TREC/249/2023: 07/20). The nature and purpose of the study were explained to teachers as participants in the study. Further to this, we also clarified that those who did not want to participate in the study were free to disengage from participation in the research. Consent for participation was obtained from teachers. The individual semi-structured and focus group interviews were administered in the schools.

5.4 Data analysis

The data were analyzed using a thematic data analysis method, involving the transcription of collected data from participants. Thematic analysis served as the method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns or themes in the existing data, following the approach outlined by Miles and Springgay (2020). The researchers employed thematic analysis primarily to identify trends and patterns that recurred across different data sets within the study. Scholars like Cohen et al. (2017) further explain data analysis as a manner of processing information so that the data generated is transferred to others. The process of data analysis was carried out using different sources, such as descriptive ones. Data from the participant interviews were analyzed by making sense of worded text by discovering and giving explanations for phenomena from different interviews that yield patterns, categories, and themes as a result of linking sets of relationships. The process is referred to as content analysis in qualitative research studies (Cleaver et al., 2017).

6 Results

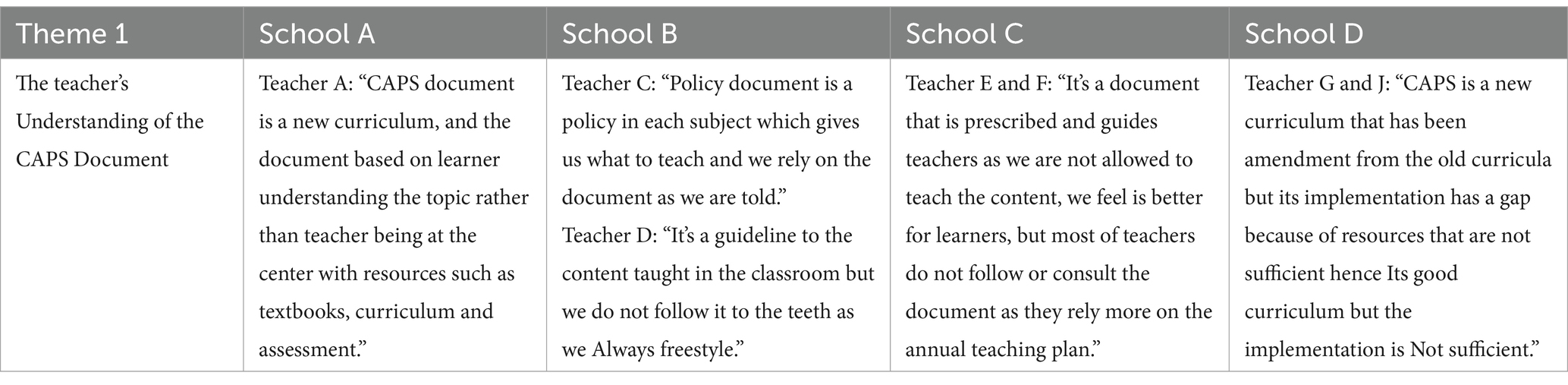

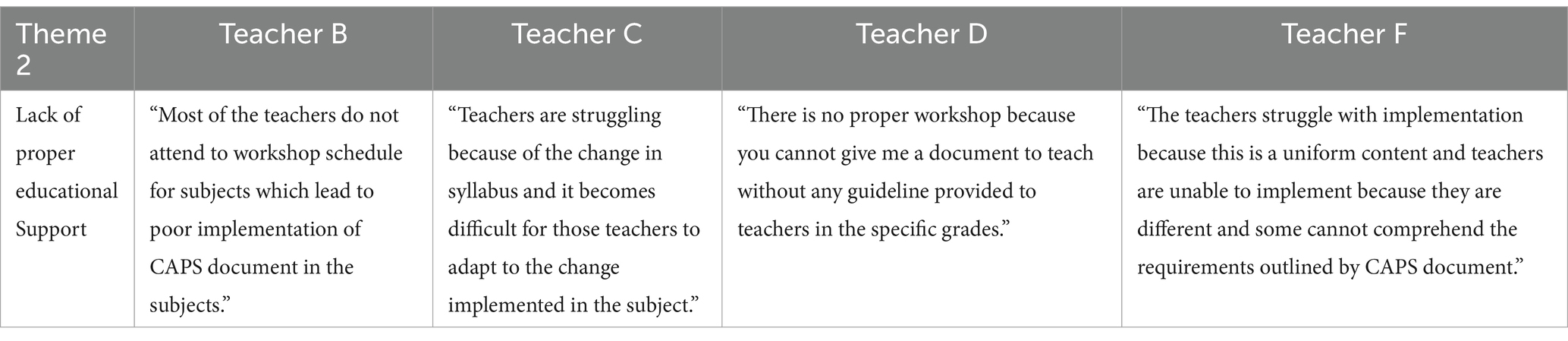

Tables 1–3 display the data for this study. Table 1 provides insights into CAPS implementation in the classroom. Table 2 outlines the challenges faced by teachers when implementing the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement Document. Table 3 presents strategies to be employed for the effective implementation of the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement Document. The themes represented on the table: teacher’s understanding of the CAPS document, lack of proper educational support and regular training of teachers.

Table 1. An understanding of the CAPS (Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement) implementation in the classroom.

Table 2. The challenges faced by teachers when implementing the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement document.

Table 3. Strategies to be employed for effectively implementation of the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement document.

On Table 1, participants remarked that Teacher A: “CAPS is a new curriculum, and the document is based on learners understanding the topic rather than the teacher being at the center with resources such as textbooks.” Teacher D noted that “It is a guideline to the content taught in the classroom, but we do not follow it to the teeth as we always freestyle.” Teacher E and Teacher F remarked that “It’s a document that is prescribed and guides teachers as we are not allowed to teach our very own content, which we feel is better for learners, but most teachers do not follow or consult the document as they rely more on the annual teaching plan. It seems like teachers have diverse meanings about the meaning of CAPS. This reveals that teachers do not use the guidelines in the teaching process but focus more on the annual teaching plan.

On Table 2, participants had this to say: Teacher A noted that “most of the teachers do not attend the workshop schedule for subjects, which leads to poor implementation of the CAPS document in the subjects.” Teacher C remarked that “teachers are struggling because of the change in syllabus, and it becomes difficult for those teachers to adapt to the change implemented in the subject. On the other hand, some participants had views as follows: Teacher D: “There are no proper workshops because you cannot give me a document to teach without any guidelines provided to teachers in the specific grades.” Teacher F noted that “the teachers struggle with implementation because this is uniform content, and teachers are unable to implement because they are different and some cannot comprehend the requirements outlined by the CAPS document.” This could be in an internal and external way to support teachers in the implementation and proper understanding of the CAPS document in line with subject content.

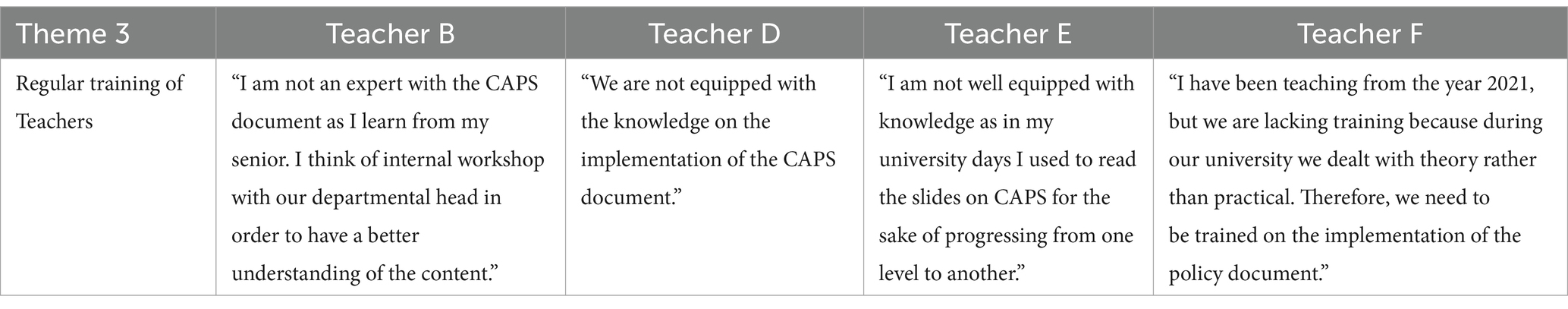

On Table 3, participants had this to say: Teacher B: “I am not an expert with the CAPS document, as I learned from my senior. I think of an internal workshop with our departmental head in order to have a better understanding of the content.” Teacher E noted that “I am not well equipped with knowledge, as in my university days I used to read the slides on CAPS for the sake of progressing from one level to another.” Teacher F noted that “I have been teaching since the year 2021, but we are lacking training because during our university days we dealt with theory rather than practical. Therefore, we need to be trained on the implementation of the policy document.”

7 Discussion

This study explored how the implementation of CAPS by teachers in the classroom can be improved. The study was guided by the following three research questions: How do teachers in Capricorn districts (South Africa) understand the content and structure of the Curriculum and Assessment Policy document? What are the challenges that teachers face when implementing the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement in Capricorn district schools? What strategies do teachers use to effectively integrate the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement guidelines into their teaching practices? To answer these questions, a qualitative case study design and analyses were conducted using descriptive data analysis as a lens through which the researcher analyzed the data collected.

7.1 Theme 1: the teacher’s understanding of the CAPS document

Our findings in the school context revealed that teachers in this study show an understanding of the CAPS document regardless of the challenges identified through its implementation in the school. In addition, teachers are the main resources in the teaching and learning process, where learner performance is determined by the knowledge, skills, qualifications, and motivation of other teachers within the field (Pamuji and Limei, 2023). Researchers like Lutovac and Assuncao Flores (2021) argue that a teacher’s understanding is vital to the teaching and learning of the subject. The CAPS document should be well understood by teachers in the school to ease the teaching of any subject found in a specific school.

7.2 Theme 2: lack of proper educational support

Letshwene and du Plessis (2021) argues that workshops do not adequately prepare teachers for the challenges they experience in the classroom; they mainly ensure that teachers understand the policy. Therefore, teachers should engage in different programs to understand the policy document and its application to the subject regularly. Falloon (2020) argues that most teachers, even though they understand the mandate of the policy document, are not prepared to put into practice the new curriculum. Motsoeneng and Moreeng (2022) also argue that the benefits of a proper understanding of the curriculum policy led to improved learner performance. Furthermore, the study revealed that teachers need more than to attend the workshop scheduled to give or enlighten their way to a proper understanding of the content in line with the CAPS document. Admiraal et al. (2021) argues that curriculum implementation is categorized into three levels, which are formal, informal, and personal. If teachers lack educational support for the implementation of curriculum policy documents, CAPS documents will not be well applied in the classroom (Mølstad et al., 2021). Taylor and Richards (2018) asserted that principals do not emphasize the formal rationale of curriculum management; they do not monitor or supervise the implementation of the CAPS document in the school. However, guidance is provided on various ways of learning, thinking, and acquiring knowledge for the future development of learners. Efendi (2022) further contends that support in terms of curriculum-management activities needs to be supervised as a way to provide guidance to a teacher in order to fully understand the curriculum implementation.

7.3 Theme 3: regular training of teachers

Moreover, our findings rely more on the need for teachers to be provided with appropriate support to be well enforced in educational institutions, and stakeholders should focus on providing skills to teachers and providing the necessary expertise to act professionally (Sancar et al., 2021). The study further revealed that a lack of proper training in line with the curriculum leads to stagnation and insufficient scholastic results. It is believed that training is a key feature of educational transformation (Abbott et al., 2019). Keddie (2019) argues that teachers should be positioned toward educational innovation in order to understand and make sense of the concepts found in the subject in line with the policy document. Nsengimana (2020) concludes that skills and training should always be available to ensure the requirements of curriculum implementation in the classroom. In addition, support, training for teachers, and monitoring processes are necessary in order to comprehend what is happening in classroom situations (Lunenburg and Ornstein, 2021). It shows that teachers have the policy documents, but implementing or using the guide regularly becomes a problem that is not yet addressed (Fleisch et al., 2019). Teachers have the perception that documents are provided, but training is not regularly administered or monitored by the senior office-bearers. This entails that teachers need to be trained and reminded about the proper implementation of the CAPS document.

The findings in this study have outlined three implications. We conclude that the lack of education support in our sampled schools could be improved by addressing issues among teachers regarding curriculum implementation. The study revealed that a lack of proper training in line with the curriculum leads to stagnation and bad scholastic results. The limited success to some of the scheduled continuous teacher development by the DBE as a way to provide training to teachers affects the effectiveness for the implementation of the CAPS document.

For this reason, it is necessary for the school management team and DBE (Department of Basic Education) to support the in-service training facilities and encourage teachers to apply the policy document daily (Freeman et al., 2014). With the insufficient resources, it is crucial for the department and policy designers to ensure that movable resources are provided together with regular workshops in place. In addition, some teachers believe that the support received from district officials and seniors in schools is not sufficient. This resulted in a lack of consistency in the use of the CAPS document in the classroom (Matsepe and Maluleke, 2019). As such, this entails that the department should ensure continuous educational support for both subject specialists and teachers.

The limitations of the study were time constraints as participants were only available during a certain period. In the light of these limitations, future researchers in curriculum should focus on the effectiveness of the policy on teaching and learning in the classroom by using a sample of participants with inclusion of the subject advisors, principals and teachers. The unique contributions of the study to the existing knowledge are that more is known about challenges of curriculum implementation but little is known of the teachers understanding of the CAPS document.

Other limitations of this study include the use of a convenience sampling technique, which may not be representative of the entire teacher population and means that interpretations should be treated with caution. Furthermore, the study only focused on the Capricorn District, which may not be representative of other districts in South Africa.

8 Conclusion

This article was aimed at exploring how the implementation of CAPS by teachers in Capricorn district (South Africa) schools can be improved. The study was pursued to provide guidance on how teachers can address the challenges that teachers face when implementing CAPS in Capricorn district schools. Furthermore, the study provided guidance to serve as a revelation to the DBE with respect to the significance of teachers’ understanding of CAPS. The contributions of this study to the existing knowledge landscape on policy implementation at school level is that continuous activities such internal and external workshops could serve the purpose of implementing the CAPS document in the classroom. Thus, DBE is in the responsibility to provide proper resources for the subject offered, even if they can be movable resources, for better implementation of the CAPS document in the classroom.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Limpopo ethical clearance commitee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We want to acknowledge the voluntary participation of subject teachers in secondary schools in Limpopo province. We also appreciate the Limpopo Department of Education, which permitted us to conduct the fieldwork study at the public schools.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbott, I., Rathbone, M., and Whitehead, P. (2019). The transformation of initial teacher education: The changing nature of teacher training. London: Routledge.

Admiraal, W., Schenke, W., de Jong, L., Emmelot, Y., and Sligte, H. (2021). Schools as professional learning communities: what can schools do to support professional development of their teachers? Prof. Dev. Educ. 47, 684–698. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2019.1665573

Alex, J. K., and Mammen, K. J. (2014). An assessment of the readiness of grade 10 learners for geometry in the context of curriculum and assessment policy statement (CAPS) expectation. Int. J. Educ. Sci. 7, 29–39. doi: 10.1080/09751122.2014.11890167

Apple, M. W. (2018). “The challenge of critical education” in Ideology and curriculum (New York: Routledge), 234–245.

Bantwini, B. D. (2010). How teachers perceive the new curriculum reform: lessons from a school district in the eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 30, 83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2009.06.002

Chaudhary, G. K. (2015). Factors affecting curriculum implementation for students. Int. J. Appl. Res. 1, 282–284. doi: 10.22271/allresearch.2015.v1.i12d.10454

Chowdhury, M. (2018). Emphasizing morals, values, ethics, and character education in science education and science teaching. MOJES 4, 1–16. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301747346_Chowdhury_Mohammad_2016_Emphasizing_Morals_Values_Ethics_And_Character_Education_In_Science_Education_And_Science_Teaching_The_Malaysian_Online_Journal_of_Educational_Science_4_2_1-16 (Accessed June 16, 2024).

Cleaver, E., Wills, D., Gormally, S., Grey, D., Johnson, C., and Rippingale, J. (2017). “Connecting research and teaching through curricular and pedagogic design: from theory to practice in disciplinary approaches to connecting the higher education curriculum” in: Developing the higher education curriculum: research-based education in practice. Eds. Carnell, B., and Fung, D. (UCL Press).145–159.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2017). “The ethics of educational and social research” in Research methods in education (London: Routledge), 111–143.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (eight). Oxon: Abingdon, 532–533.

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. London: Sage Publications.

Department of Basic Education (1997). Education white paper 3:A programme for the Transformation of Higher Education. Pretoria, South Africa.

Department of Basic Education (2009). Education Statistics in South Africa 2007. Pretoria, South Africa.

Department of Basic Education (2011). Curriculum and assessment policy statement. Pretoria: Government Printers.

Dieudé, A., and Prøitz, T. S. (2024). Curriculum policy and instructional planning: teachers’ autonomy across various school contexts. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 23, 28–47. doi: 10.1177/14749041221075156

Efendi, N. (2022). Implementation of Total quality management and curriculum on the education quality. J. Soc. Stud. Educ. Res. 13, 120–149.

Falloon, G. (2020). From digital literacy to digital competence: the teacher digital competency (TDC) framework. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 68, 2449–2472. doi: 10.1007/s11423-020-09767-4

Fleisch, B., Gultig, J., Allais, S., and Maringe, F. (2019). Background paper on secondary education in Africa: Curriculum reform, assessment, and national qualifications frameworks. South Africa: University of the Witwatersrand.

Fomunyam, K. G. (2016). Theorising student constructions of quality education in a South African university. Southern Afr. Rev. Educ. Product. 22, 46–63.

Freeman, J., Simonsen, B., Briere, D. E., and MacSuga-Gage, A. S. (2014). Pre-service teacher training in classroom management: a review of state accreditation policy and teacher preparation programs. Teach. Educ. Special Educ. 37, 106–120. doi: 10.1177/0888406413507002

Galvan, M. E., and Coronado, J. M. (2014). Problem-based and project-based learning: promoting differentiated instruction. Nat. Teach. Educ. J. 7, 39–42.

Gumede, V., and Biyase, M. (2016). Educational reforms and curriculum transformation in post-apartheid South Africa. Environ. Econ. 7, 69–76. doi: 10.21511/ee.07(2).2016.7

Ishemo, R. (2019). Improving the provision of education by borrowing policies and practices from a foreign country. Available at: https://www.suaire.sua.ac.tz/handle/123456789/4027

Juliani, A. J. (2014). Inquiry and innovation in the classroom: Using 20%-time, genius hour, and PBL to drive student success. London: Routledge.

Killen, P. O. C. (2015). Reflections on Core curriculum, Mission, and Catholic identity in our time. J. Cath. Higher Educ. 34, 77–90.

Letshwene, M. J., and du Plessis, E. C. (2021). The challenges of implementing the curriculum and assessment policy statement in accounting. S. Afr. J. Educ. 41, S1–S10. doi: 10.15700/saje.v41ns2a1978

Lunenburg, F. C., and Ornstein, A. (2021). Educational administration: Concepts and practices. United Kingdom: Sage Publications.

Lutovac, S., and Assuncao Flores, M. (2021). ‘Those who fail should not be teachers’: pre-service teachers’ understandings of failure and teacher identity development. J. Educ. Teach. 47, 379–394. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2021.1891833

Maharajh, L. R., Nkosi, T., and Mkhize, M. C. (2016). Teachers’ experiences of the implementation of CAPS in three primary schools in KwaZulu Natal. Afr. Public Service Deliv. Perform. Rev. 4, 371–388. doi: 10.4102/apsdpr.v4i3.120

Mandukwini, N. (2016). Challenges towards curriculum implementation in high schools in mount Fletcher District, Eastern Cape (doctoral dissertation).

Mathura, P. (2019). Teachers’ perspectives on a curriculum change: a Trinidad and Tobago case study. Int. J. Innov. Bus. Strat. 5, 252–263. doi: 10.20533/ijibs.2046.3626.2019.0035

Matsepe, D., and Maluleke, M. (2019). Constraints to optimal implementation of curriculum and assessment policy statement (CAPS) in the north west province in South Africa. Afr. J. Peace Conflict Stud. 27, 177–195.

Mbatha, M. G. (2016). Teachers' experiences of implementing the curriculum and assessment policy statement (CAPS) in grade 10 in selected schools at Ndwedwe in Durban (Doctoral dissertation, University of South Africa.

Miles, J., and Springgay, S. (2020). The indeterminate influence of Fluxus on contemporary curriculum and pedagogy. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 33, 1007–1021. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2019.1697469

Mishra, N. R. (2020). Curricular issues in school education: critical analysis of understanding about the implemented curriculum. Res. Manag. 3, 84–92. doi: 10.3126/rupantaran.v3i0.31744

Mølstad, C. E., Pettersson, D., and Prøitz, T. S. (2018). “Soft infusion: constructing ‘teachers’ in the PISA sphere” in Education policies and the restructuring of the educational profession: global and comparative perspectives, Eds. Normand, R., Liu, M., Carvalho, L., Oliveira, D., and LeVasseur, L. (Singapore: Springer) 13–26.

Mølstad, C. E., Prøitz, T. S., and Dieude, A. (2021). When assessment defines the content—understanding goals in between teachers and policy. Curric. J. 32, 290–314. doi: 10.1002/curj.74

Moser, A. , and Korstjens, I. (2018). Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur J Gen Pract, 24, 9–18.

Motsoeneng, T. J., and Moreeng, B. (2022). Accounting Teachers' understanding and use of assessment for learning to enhance curriculum implementation. J. Stud. Soc. Sci. Human. 8, 288–302.

Nevenglosky, E. A. (2018). Barriers to effective curriculum implementation (Doctoral dissertation, Walden University).

Nkosi, T. P. (2014). Teachers' experiences of the implementation of the curriculum and assessment policy statement: A case study of three primary schools in KwaZulu- Natal Province (doctoral dissertation).

Nsengimana, V. (2020). Implementation of competence-based curriculum in Rwanda: opportunities and challenges. Rwandan J. Educ. 5, 2312–9239.

Ogunniyi, M. B., and Mushayikwa, E. (2015). “Teacher education in South Africa: issues and challenges” in: Teacher education systems in Africa in the digital era, Africa Books Collective. 71.

Palestina, R. L., Pangan, A. D., and Ancho, I. V. (2020). Curriculum implementation facilitating and hindering factors: the Philippines context. Int. J. Educ. 13, 91–104. doi: 10.17509/ije.v13i2.25340

Pamuji, S., and Limei, S. (2023). The managerial competence of the madrasa head in improving teacher professionalism and performance at mi Al-Maarif Bojongsari, Cilacap District. Pengabdian 1, 66–74. doi: 10.55849/abdimas.v1i2.158

Richards, J. C. (2013). Curriculum approaches in language teaching: forward, central, and backward design. RELC J. 44, 5–33. doi: 10.1177/0033688212473293

Rogan, J., and Aldous, C. (2005). Relationships between the constructs of a theory of curriculum implementation. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 42, 313–336. doi: 10.1002/tea.20054

Rogan, J. M., and Grayson, D. J. (2003). Towards a theory of curriculum implementation with particular reference to science curriculum education in developing countries. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 25, 1171–1204. doi: 10.1080/09500690210145819

Sancar, R., Atal, D., and Deryakulu, D. (2021). A new framework for teachers’ professional development. Teach. Teach. Educ. 101:103305. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103305

Sepadi, M. D. (2018). Student teachers' preparation for inclusive education: The case of the University of Limpopo (Master’s dissertation).

Taylor, P. H., and Richards, C. M. (2018). An introduction to curriculum studies. London: Routledge.

Thaanyane, M., and Thabana, J. (2019). Exploring curriculum implementation in response to labour markets. SJIF. Maseru, Lesotho.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2014). The differentiated classroom: responding to the needs of all learners United states: ASCD.

Tshidaho, M., and Otukile-Mongwaketse, M. (2018). Teacher's understandings of implementing curriculum: a comparative study between Botswana and South African rural primary schools education system. Botswana: University of Botswana.

Tus, J. (2020). The influence of study attitudes and study habits on the academic performance of the students. Int. J. Res. Writ. 2, 11–32.

Tyler, R. W. (2013). Basic principles of curriculum and instruction. Chicago: University of Chicago press.

Van der Nest, A. (2012). Teacher mentorship as professional development: Experiences of Mpumalanga primary school natural science teachers as mentees (Doctoral dissertation, University of South Africa).

Watt, M. G. (2020). The national school reform agreement: its implications for stage – Level curriculum reforms. Tasmania, Australia: Institute of education sciences.

Yang, W., and Li, H. (2018). A school-based fusion of east and west: a case study of modern curriculum innovations in a Chinese kindergarten. J. Curric. Stud. 50, 17–37. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2017.1294710

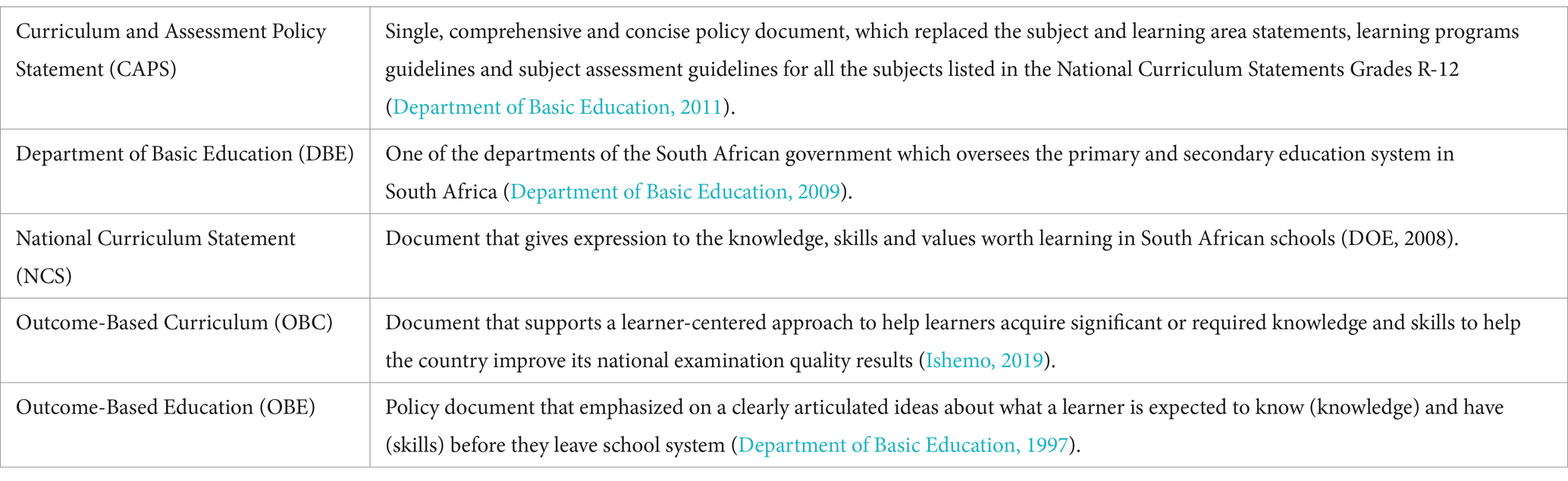

Glossary

Keywords: curriculum, implementation, policy, teacher, South Africa

Citation: Sepadi M and Molapo K (2024) Exploring teacher understanding of curriculum and assessment policy statement document implementation in South African schools. Front. Educ. 9:1354959. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1354959

Edited by:

Ivan Müller, University of Basel, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Asma Shahid Kazi, Lahore College for Women University, PakistanGodsend Chimbi, University of the Free State, South Africa

Copyright © 2024 Sepadi and Molapo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Medwin Sepadi, bWVkd2luLnNlcGFkaUB1bC5hYy56YQ==

Medwin Sepadi

Medwin Sepadi Karabo Molapo

Karabo Molapo