- 1School Psychology and Development in Context, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

- 2Research Institute of Child Development and Education, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 3KU Leuven Child and Youth Institute, Leuven, Belgium

It is widely acknowledged that high-quality teacher-student relationships contribute to both student and teacher well-being. However, research shows that building these relationships can be challenging for teachers and signals opportunities for teacher education to better prepare them for building high-quality teacher-student relationships. As teachers’ relationship-building competence allows them to establish high-quality relationships with students, even those typically at-risk for conflictual relationships, we propose a learning trajectory targeting teachers’ dyadic relationship-building competence to be implemented in initial teacher education. Such a learning trajectory allows for progressively deepening the level of understanding and self-reflection throughout the three-year initial education program. To address teachers’ relationship-building competence in teacher education, relevant competencies, selected in previous research by an independent expert panel, were translated into specific learning goals, learning activities, and materials in close collaboration with partner university colleges. An overview of planned quantitative and qualitative data collection is presented. The learning trajectory could strengthen initial pre-primary and primary teacher education programs in supporting pre-service teachers’ relationship-building competence.

1 Introduction

High-quality teacher-student relationships contribute to both student and teacher well-being (Aboagye et al., 2020; Ansari et al., 2020a; Haldimann et al., 2023). Teachers’ relationship-building competence allows them to establish high-quality dyadic relationships with students, especially in the face of challenging student behavior (Borremans and Spilt, under review). However, research shows that teacher education currently does not sufficiently prepare teachers for building high-quality relationships with students (Jensen et al., 2015; Borremans and Spilt, under review). We therefore propose a learning trajectory targeting teachers’ relationship-building competence, to be implemented in initial pre-primary and primary teacher education. The aim of the current paper is to show how existing theory and research were translated into a comprehensive learning trajectory.

1.1 The importance of teacher–student relationships

From 2004 until 2019, the number of educators in Flanders, the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium, reporting psychological fatigue and stress has consistently increased; simultaneously, their job satisfaction has steadily decreased (Bourdeaud’hui et al., 2019). In Flanders and beyond, approximately one in six teachers reports significant stress and burnout symptoms, surpassing other professions (Bourdeaud’hui et al., 2019; OECD, 2021). These elevated levels of stress and burnout symptoms constitute a primary factor driving educators to leave the teaching profession (Liu and Meyer, 2005; Skaalvik and Skaalvik, 2011; OECD, 2021; Mombaers et al., 2023). The majority of primary school teachers who have left the profession cite occupational stress as a contributing factor (de Jonge and de Muijnck, 2002).

One important factor contributing to teachers’ experience of stress, declined job satisfaction, and attrition, is their relationships with students (Aboagye et al., 2020). Conflictual teacher-student relationships can be emotionally demanding and result in burnout symptoms such as emotional exhaustion (Alamos et al., 2022; Haldimann et al., 2023). Conversely, close relationships foster a sense of self-efficacy, personal accomplishment and contribute to teachers’ job motivation (Zee et al., 2017; Corbin et al., 2019; Haldimann et al., 2023).

In addition to teachers’ well-being, the affective quality of dyadic teacher-student relationships can significantly impact student development and well-being. Students who maintain close relationships with their teacher are more likely to be engaged in school, achieve better, and build positive peer relationships (Nguyen et al., 2020; Ansari et al., 2020a; Engels et al., 2021; Endedijk et al., 2022; ten Bokkel et al., 2022). Conversely, students facing conflict in their relationship with the teacher are at risk for peer victimization, delinquency and externalizing problems (Bosman et al., 2018; Ansari et al., 2020a; Kim, 2021; Obsuth et al., 2021; Roorda and Koomen, 2021; ten Bokkel et al., 2022). Improving dyadic teacher-student relationship quality might thus positively impact both teacher and student well-being.

1.2 Improving teacher–student relationship quality

As teachers often report challenges in establishing high-quality dyadic teacher-student relationships (Jensen et al., 2015; Aspelin et al., 2020; Borremans et al., under review), it is important to note that several intervention studies have demonstrated the potential for enhancing relationship quality (for reviews, see Kincade et al., 2020; Poling et al., 2022). The most noteworthy interventions targeting dyadic teacher-student relationships (Spilt et al., 2022) are Banking Time (and adapted versions; Driscoll and Pianta, 2010; Vancraeyveldt et al., 2015), the Establish-Maintain-Restore (EMR-method Cook et al., 2018; Duong et al., 2019), and LLInC (Leerkracht Leerling Interactie Coaching in Dutch or Teacher Student Interaction Coaching; Spilt et al., 2012; Bosman et al., 2021; Koenen et al., 2021). A common elements analysis revealed several practices, both direct and indirect, that contribute to the effectiveness of these interventions (Kincade et al., 2020). For instance, the teacher regularly spending one-on-one time with a student and choosing child-led activities can foster closer and less conflictual relationships.

Whereas curative interventions hold promise for enhancing dyadic teacher-student relationship quality in case problems have arisen, preventive measures could potentially have an even greater impact. Equipping teachers with the essential skills to foster high-quality relationships proactively, before issues arise, could help mitigate the detrimental effects of conflictual relationships on the well-being of both teachers and students. Importantly, Bosman et al. (2021) found support for transfer effects across students when implementing a dyadic relationship-focused reflection program targeting one specific student. These transfer effects support the idea of an overarching relationship-building competence of teachers, which has been shown to contribute to high-quality teacher-student relationships (Borremans and Spilt, under review). Teachers’ relationship-building competence refers to their ability to establish and maintain close dyadic relationships and to restore conflictual relationships as well as to effectively cope with the (emotional) consequences of these relationships (Cook et al., 2018; McGrath and Van Bergen, 2019; de Ruiter et al., 2021; Borremans and Spilt, 2022; Borremans and Spilt, under review). We propose to proactively strengthen teachers’ relationship-building competence during initial teacher education, to reduce the occurrence of conflictual relationships when novice teachers enter the profession.

2 Pedagogical framework: conceptualization of teachers’ relationship-building competence

The teacher competence model developed by Blömeke and Kaiser (2017) provided a valuable framework to structure our understanding of relationship-building competence. Blömeke and Kaiser (2017) conceptualize teacher competence as a multidimensional construct, including teachers’ dispositions (professional knowledge and affect-motivation) and situation-specific cognitive skills (perception, interpretation, and decision-making), which underlie their observable behavior in the classroom. The model highlights the importance of affective-motivational factors such as attitudes, beliefs, self-efficacy… in addition to more cognitive factors (knowledge and skills) in the development of teachers’ competence (Blömeke and Kaiser, 2017). In our conceptualization of relationship-building competence we include these distinct dimensions as well.

Content-wise, our conceptualization of relationship-building is rooted in prominent theories on dyadic teacher-student relationships (for a review see Spilt et al., 2022), specifically attachment theory (Pianta, 1999a; Verschueren et al., 2012) and self-determination theory (Ryan and Deci, 2000). In addition to concepts derived from these theories (e.g., the teacher functions as a secure base and safe haven for the student), we emphasize teachers’ adaptive coping as a core aspect of teachers’ relationship-building competence, as teachers’ ability to cope with negative emotions and conflict is crucial in establishing high-quality relationships (Hastings and Brown, 2002; McGrath and Van Bergen, 2019; Koenen et al., 2019b; de Ruiter et al., 2021).

2.1 Affect-motivation

First, to establish high-quality relationships with students, teachers must invest time and effort. Several affect-motivational dispositions contribute to teachers’ continuous effort to establish qualitative relationships with students. For instance, both attachment theory and self-determination theory highlight the importance of the universal need to belong, which motivates each person to establish relationships with others (Spilt et al., 2011; Klassen et al., 2012). Importantly, day-to-day interactions between the teacher and the student are considered to be at the foundation of the teacher-student relationship. In order to engage in meaningful interactions, the teacher requires a basic attitude of empathy, respect, and non-prejudice (Driscoll et al., 2011; Cook et al., 2018; Aspelin and Jonsson, 2019; McGrath and Van Bergen, 2019; Kincade et al., 2020). More specific attitudes are at play as well. For instance, teachers who believe that they themselves can do something to change the quality of their relationships might be more motivated to invest time and effort compared to teachers who attribute negative relationship quality mainly to stable student characteristics (Yoon, 2002; Spilt et al., 2012; McGrath and Van Bergen, 2019; Bosman et al., 2021; Koenen et al., 2021). Likewise, teachers who are convinced of the importance of teacher-student relationships for their own and the student’s well-being (e.g., McGrath and Van Bergen, 2015) could be more inclined to persist in their attempts to build high-quality relationships. Teachers’ attitude toward teacher-student relationships has indeed been shown to predict closeness in their relationships with students (Borremans and Spilt, under review). Furthermore, teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs on practices that support relationship-building might influence how likely they are to (successfully) implement these practices and consequently improve relationship quality (Zee and Koomen, 2016). Moreover, teachers’ self-efficacy in building closeness (e.g., knowing how to calm a student when they are upset) was found to predict more closeness and less conflict and teachers’ self-efficacy in coping with conflict (e.g., keeping your energy even when repeatedly confronted by disruptive behavior) was shown to predict less conflict (Borremans and Spilt, under review). Finally, teachers’ self-efficacy in reflective functioning (e.g., reflecting on the perspective of the student) might help teachers to recognize dependency in what might at first sight seem disruptive behavior (Borremans and Spilt, under review) and allow them to respond appropriately to the needs of the student.

2.2 Professional knowledge

Second, teachers require sufficient professional knowledge on teacher-student relationships and coping to inform their perceptions, interpretations, and decisions made in the classroom. We opted to focus on attachment theory and self-determination theory, as these frameworks are predominantly used in research on dyadic teacher-student relationships (Roorda et al., 2017; Spilt et al., 2022) and were prioritized above for instance interpersonal theory in preparatory research (Borremans and Spilt, 2023). Although the learning trajectory does not aim to provide teachers with a thorough knowledge of theories, we argue that a basic understanding of relevant concepts can help teachers to understand, discuss, and reflect on their relational experiences in the classroom (Pianta, 1999a; Aspelin et al., 2021; Koenen et al., 2022; Borremans and Spilt, 2023; Borremans et al., under review).

Attachment theory conceptualizes the quality of teacher-student relationships based on three dimensions: closeness, conflict, and dependency (Pianta, 2001). Closeness reflects the degree of openness and affection and conflict reflects the presence of resistance and discord in the relationship. Dependency reflects the extent of excessive dependent behavior of the student toward the teacher (Verschueren et al., 2012). In an effective relationship, characterized by high levels of closeness and low levels of conflict and dependency, the teacher functions as a “secure base” and “safe haven” for the student, which supports the student’s autonomous exploration and cognitive, social, and emotional development (Pianta, 2001; Verschueren et al., 2012). Next, self-determination theory states that every person has three fundamental, psychological needs: the need for autonomy, relatedness, and competence. All three needs must be fulfilled in order to be motivated and engaged (Deci et al., 1991; Ryan and Deci, 2000). When one of these needs is frustrated (e.g., no possibility to interact with others and fulfill the need for relatedness), students’ motivation and engagement in class might decrease (Opdenakker, 2014). The teacher can offer autonomy support, involvement, and structure to fulfill the basic needs of the students. This need fulfillment could in turn result in higher motivation, engagement, and achievement in class (Stroet et al., 2013; Reeve and Cheon, 2021). Teachers’ knowledge of these concepts can aid them in interpreting student behavior in the classroom and inform their decision-making when reacting to this behavior.

The theories discussed above mainly focus on the relational needs of the student. However, the teacher also has a fundamental need to belong and the relational or emotional needs of the teacher should thus be addressed as well (Baumeister and Leary, 1995; Spilt et al., 2011; Koomen, 2022). Fulfillment of teachers’ need for relatedness with students has been shown to uniquely contribute to their wellbeing (Klassen et al., 2012). Moreover, teaching is an inherently emotional task and teachers’ emotional experiences with students have been shown to greatly contribute to their well-being (Keller et al., 2014; Becker et al., 2015; Taxer et al., 2019). We therefore argue that teachers’ knowledge of adaptive coping strategies (e.g., problem solving, reflecting upon ones emotions) contributes to their competence in building high-quality relationships with students. Maladaptive coping strategies (e.g., avoidance) not only place teachers at greater risk of experiencing burnout symptoms, such as emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, but also diminishes their prospects of establishing high-quality relationships with students (Hastings and Brown, 2002; Beltman et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2019; de Ruiter et al., 2021). Knowledge of adaptive coping strategies, such as positive reappraisal, is a first step in successfully coping with negative emotional experiences in the classroom in general and in interactions with students in particular (Hastings and Brown, 2002; Beltman et al., 2011; Chang, 2013; Gustems-Carnicer et al., 2019).

2.3 Situation-specific skills

Third, teachers require a sufficient situation-specific skills to flexibly use effective practices supporting teacher-student relationships. Attachment theory highlights teachers’ reflective functioning, their ability to reflect upon their own and the student’s cognitions and emotions, as well as teachers’ sensitivity, their ability to take the student’s perspective and respond adequately to the student’s needs, as important levers in establishing close relationships (Pianta, 1999b; Sabol and Pianta, 2012; Spilt et al., 2012; McGrath and Van Bergen, 2019; Bosman et al., 2021; Spilt and Koomen, 2022). Self-determination theory states that teachers can support students in fulfilling their needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competence, by offering autonomy support, involvement, and structure, respectively (Ryan and Deci, 2000; Opdenakker, 2014). Additional relevant situation-specific skills for establishing high-quality teacher-student relationships can be derived from effective interventions (often based on attachment or self-determination theory, Driscoll and Pianta, 2010; Vancraeyveldt et al., 2015; Cook et al., 2018; Kincade et al., 2020; Poling et al., 2022). The common elements analysis by Kincade et al. (2020) emphasizes the importance of pro-active and direct practices such as spending one-on-one time with students, coaching emotions, and positive greetings and farewells.

Additionally, applying adaptive coping strategies in the classroom can support teachers in coping with conflicts with students and pursuing high-quality relationship. Being able to cope with negative emotions and conflicts in interactions with students allows teachers to remain sensitive to the students’ needs (Koenen et al., 2019b; Ansari et al., 2020b). During a conflict, teachers first need to cope with their own emotions before they are able to reconcile with the student and tend to the student’s needs. Adaptive coping strategies that have been shown to increase (pre-service) teachers’ resilience include positive reappraisal, seeking guidance and support, and problem-solving (Beltman et al., 2011; Gustems-Carnicer et al., 2019).

2.4 Observable behavior

Finally, following the competence model of Blömeke and Kaiser (2017), teachers’ affect-motivation, professional knowledge, and situation-specific skills give rise to observable behavior, that is qualitative interactions with students. Such interactions in turn support the development of high-quality affective relationships. Feedback and reflection on teachers’ own behavior in interactions with specific students can further enhance teachers’ affect-motivation, professional knowledge, and situation-specific skills and improve future interactions.

3 Targeting relationship-building competence in teacher education

As teachers gain their first experience in the classroom during initial teacher education, their relationship-building competence starts developing already in the pre-service phase. Initial teacher education programs are thus an ideal starting point for supporting the development of teachers’ relationship-building competence. Equipping teachers with the necessary affect-motivation (e.g., attitudes, self-efficacy beliefs), knowledge, and skills already before they enter the classroom, might increase their resilience as starting teachers (Blömeke and Kaiser, 2017). However, both researchers and teachers argue that current teacher education programs might not sufficiently prepare teachers for the at times challenging task of building high-quality relationships with their students. Teacher education programs have been criticized for addressing pedagogical and relational competencies to a lesser extent compared to (subject) knowledge and didactical skills which receive ample attention and focus (Jo, 2014; Jensen et al., 2015; Korpershoek et al., 2016; Rucinski et al., 2018; Aspelin and Jonsson, 2019; Borremans et al., under review).

Some efforts toward including relational competence in teacher education have been initiated, particularly in Denmark and Sweden (Jensen et al., 2015; Aspelin and Jonsson, 2019). In various, mainly qualitative, studies (pre-service) teachers’ conceptualizations and experiences of relational competence in the classroom were investigated (Jensen et al., 2015; Aspelin and Jonsson, 2019; Aspelin et al., 2020; Aspelin and Eklöf, 2022). Additionally, video-based intervention research showed opportunities for improving pre-service teachers’ relational competence, specifically shifting their attention to relational aspects of the classroom (Aspelin et al., 2021; Ewe and Aspelin, 2021). For instance, pre-service teachers used more relational language to discuss a video after receiving a presentation on the concept of relational competence and analyzing a similar video with support of a researcher (Ewe and Aspelin, 2021).

3.1 Research in Flanders

Within Flanders, efforts to investigate teachers’ relationship-building competence in teacher education have only recently started. Research suggests four limitations in the way that relationship-building competence is targeted in current teacher education curricula in Flanders.

First, teacher-student relationships are included in initial teacher education, yet addressed to a lesser extent compared to other domains of teaching such as didactical skills (Borremans et al., under review; Weltens, 2022). More importantly, more attention is being paid to classroom-level relationships than to dyadic teacher-student relationships (Van der biesen, 2022; Weltens, 2022; Borremans et al., under review). Considering the teacher’s role as a group educator, paying attention to the classroom-level is inherently warranted. Moreover, classroom-level relationships can indeed be of significance for students’ development as well as for the development of high-quality dyadic teacher-student relationships (Buyse et al., 2008; Moen et al., 2019; Walker and Graham, 2021). However, the influence of dyadic teacher-student relationships on students’ development can be differentiated from the effects of classroom-level relationships and low-quality dyadic teacher-student relationships can undermine the advantages of high-quality classroom environments (Buyse et al., 2009; Crosnoe et al., 2010; Rucinski et al., 2018; Nguyen et al., 2020). Similarly, classroom-level emotional support cannot serve as a remedy for low-quality dyadic teacher-student relationships (Rucinski et al., 2018). Within teacher education, the importance of dyadic teacher-student relationships should not be overlooked (Koomen, 2022).

Second, (dyadic) teacher-student relationships seem to be addressed rather implicitly and diffuse throughout the program (Van der biesen, 2022; Weltens, 2022; Borremans et al., under review). Teacher educators, pre-service teachers, and internship mentors agree that (dyadic) teacher-student relationships are important, yet only limited targeted courses, classes or assignments are included to convey this importance (Van der biesen, 2022; Weltens, 2022; Borremans et al., under review).

Third, teacher-student relationships are currently addressed mainly when pre-service teachers initiate the conversation, often triggered by conflictual relationships during the internship (Borremans et al., under review). However, an absence of conflict does not automatically correspond to a high level of closeness in the teacher-student relationship (Koomen et al., 2012). A more proactive approach, strengthening pre-service teachers before problems arise, might be valuable in establishing high-quality relationships and preventing negative classroom experiences.

Fourth, when teacher-student relationships are addressed, not all dimensions of competence are targeted. Current teacher education curricula in Flanders seem to mainly focus on applying relationship-building skills (Van der biesen, 2022; Weltens, 2022; Borremans et al., under review). Even so, pre-service teachers in their final year do report more knowledge compared to pre-service teachers in their first year of teacher education (Borremans and Spilt, 2022). Their growth in attitude and self-efficacy, however, appears to be rather limited (Borremans and Spilt, 2022).

While these results need to be replicated (for instance, in a longitudinal design), this research indicates that there is room for improvement within Flemish teacher education to target teachers’ relationship-building competence. There is a need for more explicit and structural attention to dyadic teacher-student relationships, targeting pre-service teachers’ knowledge, affect-motivation, as well as situation-specific skills.

To address these concerns and opportunities, we aimed to develop a learning trajectory targeting teachers’ dyadic relationship-building competence, to be implemented in pre-primary and primary initial teacher education in the Flemish context. Initial teacher education serves as an optimal starting point to help beginning teachers develop the necessary attitudes, knowledge and skills to build high-quality relationships with their students. Recognizing the fundamental role of teacher-student relationships in education, we chose to develop a comprehensive, three-year, learning trajectory. This trajectory allows for ongoing exploration and reflection on the topic, progressively deepening the level of understanding and self-reflection with each subsequent year of initial teacher education.

4 Learning environment and learning objectives and materials

4.1 Context

The learning trajectory was developed to align with the Flemish context of teacher education. In Flanders, initial teacher education is offered at the professional bachelor level, spanning three years. The program consists of both theoretical courses and internships. Internships become more prominent and extensive with each subsequent year of the program. Separate programs cater to different compulsory education levels (pre-primary, primary and secondary education). The learning trajectory was developed to correspond to three years of education, with specific materials tailored to different levels (particularly pre-primary and primary education). Pre-primary and primary teacher education curricula typically include courses on subject contents, didactics, and psycho-pedagogical topics (including for instance developmental psychology and classroom management). As discussed above, dyadic teacher-student relationships are currently only scarcely addressed (Van der biesen, 2022; Weltens, 2022; Borremans et al., under review).

The learning trajectory was developed by researchers at a university in close collaboration with teacher educators from five partner university colleges (out of 11 university colleges offering teacher education in Flanders). Researchers contributed with their advanced knowledge of the scientific literature on relationship-building, while teacher educators provided valuable insights into how this knowledge can be translated to learning activities and materials, tailored to pre-service teachers.

4.2 Selecting learning objectives and developing activities

In a previous study within the overarching research project (Borremans and Spilt, 2023), learning objectives were carefully identified. First, a list of competencies, derived from diverse theoretical frameworks and interventions targeting teacher–student relationships was compiled. Next, using the Delphi method, an expert panel consisting of nine researchers and teacher educators selected competencies deemed essential for inclusion in initial teacher education. Appendix A presents the 36 competencies that were selected as “need to know”, as well as an overview of the frameworks from which each competence was derived and example references. We structured the selected competencies into five themes: the importance of teacher-student relationships for students (four competencies), key concepts to understand and describe relationships (seven competencies), attitudes and reflective functioning (six competencies), specific strategies to establish and maintain relationships (17 competencies), and building relationships in the context of student diversity (two competencies). Additionally, the expert panel rated the desired level of mastery of the selected competencies at the end of initial teacher education (see Appendix A, target mastery level year 3). Based on the Delphi study, we outlined specific competencies to be addressed in each year of the teacher education program. This strategic plan (Appendix A) supports the progressive development of essential attitudes, skills, and knowledge, by setting a target mastery level for each year of teacher education, ultimately leading to the desired level of mastery by the end of the three-year program.

Based on the strategic plan, specific learning goals for each of the selected ‘need to know’ competencies were formulated. For all goals, learning activities and materials were developed, targeting both pre-service teachers (e.g., accessible texts, assignments) and teacher educators (e.g., academic texts, suggestions for learning activities, audio and video case materials, ready-to-use PowerPoint presentations). In Appendix B an example of this translation from competence description to specific materials is presented. Importantly, teacher educators can choose for instance different learning activities, or use additional case materials, at their own discretion. Learning goal descriptions and associated activities and materials were presented to teacher educators from partner university colleges for feedback. Several adaptations were made pre-implementation to address concerns or incorporate suggestions. An overview of learning activities and materials is provided in Appendix C. Completing all learning activities would take approximately 14 h for pre-service teachers (including preparation time and time spent in class, excluding observation time; 6.5 in year 1, 4 h in year 2, and 4 h in year 3).

5 Assessment: data collection planned

5.1 Quantitative evaluation

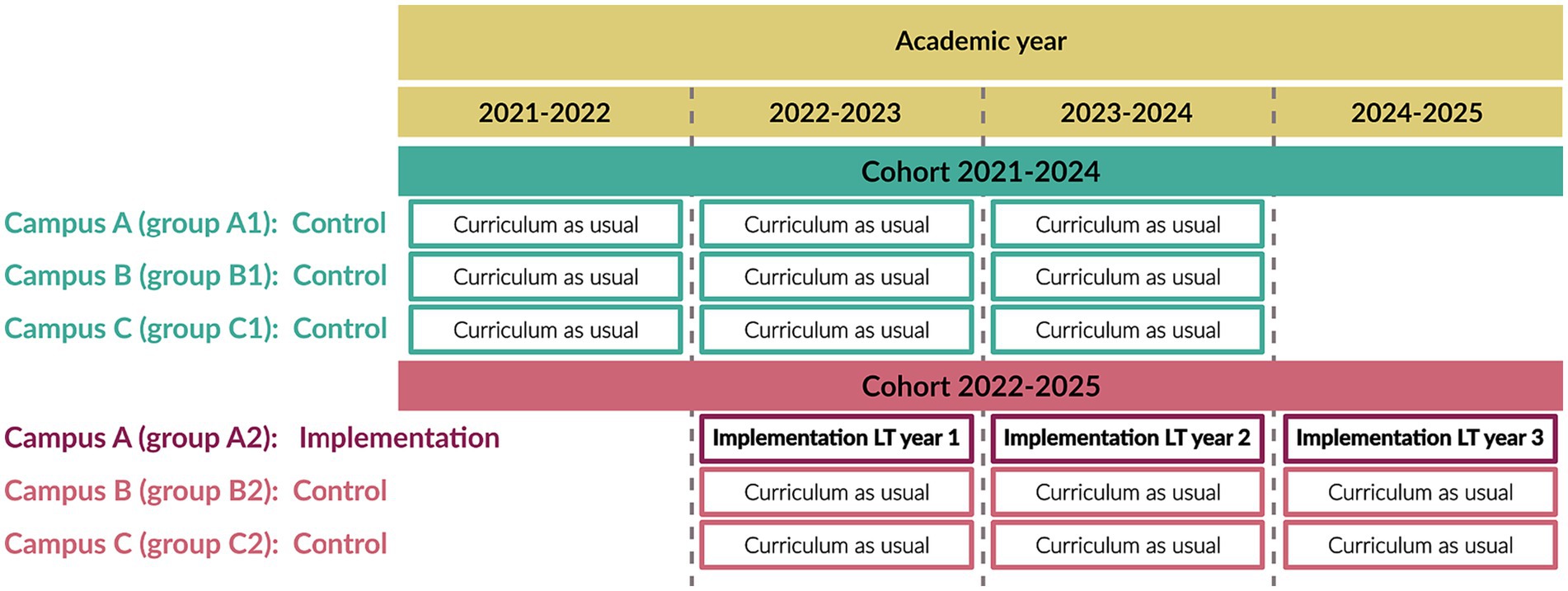

We planned a longitudinal, multi-cohort study employing a quasi-experimental design. Data collection is currently ongoing in two cohorts of pre-service teachers (cohort 1 and cohort 2) at three university college campuses (labeled A, B and C). This design resulted in six groups (see Figure 1) with one group serving as the intervention group (group A2). At each campus, both the pre-primary and primary teacher education programs participate in the project. Data collection started in September 2021 in the first cohort, expected to graduate in June 2024. Data collection started in September 2022 in the second cohort, expected to graduate in June 2025. Around 300 pre-service teachers per cohort were reached in the first year of teacher education. However, drop-out is expected throughout the longitudinal study. No elements of the learning trajectory will be implemented in the 2021–2024 cohort. Campus A’s primary teacher education program volunteered to act as intervention condition and agreed to implement the three-year learning trajectory in the second cohort (group A2, 2022–2025). The other groups serve as control groups.

We will be able to compare groups both within-cohort but between campuses (A2 compared to B2 and C2; different curriculum, same cohort), and between-cohorts yet within campuses (A2 compared to A1; same curriculum, different cohorts). In this way, we address both cohort effects and curriculum effects.

Pre-service teachers report on their relationship-building competence through an online questionnaire at the start and end of each academic year. The COMpetence Measure of Individual Teacher–student relationships (COMMIT; Borremans and Spilt, 2022) was developed within the overarching research project to assess teachers’ relationship-building competence dispositions. Associations with emotional intelligence, teacher beliefs, job motivation, burnout symptoms, (student-specific) teacher self-efficacy beliefs and teacher–student relationship quality supported construct validity of the questionnaire both in a pre-service (Borremans and Spilt, 2022) and in-service sample (Borremans and Spilt, under review). Furthermore, teachers’ relationship-building competence dispositions were shown to predict relationship quality (Borremans and Spilt, under review). Teachers’ attitude, knowledge of teacher–student relationships, and self-efficacy in building closeness, coping with conflict, and reflective functioning were found to be especially important in establishing close and less conflictual relationships, in particular with disruptive students (Borremans and Spilt, under review).

Additionally, pre-service are asked to provide some demographic information and to complete questionnaires targeting teacher self-efficacy beliefs (Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk Hoy, 2001; Robinson, 2020; cf. Zee et al., 2016).

Finally, at the end of their teacher education program, pre-service teachers’ situation-specific skills will be assessed. Situation-specific skills are predominantly assessed using case materials (Weyers et al., 2023). While most test instruments are video-based, vignettes or paper cases have been used as well. In line with these practices, pre-service teachers will read a case description and answer three accompanying, open questions (see Appendix D). The case description outlines a particular student’s behavior at school and the challenges the student is facing (e.g., frequently distracted, problems connecting with peers) as well as indicators of a conflictual relationship with the teacher. The first question assesses whether pre-service teachers spontaneously identify issues related to the teacher–student relationship. The second question assesses pre-service teachers’ ability to identify and apply relevant theoretical constructs as they analyze the case description. The third question assesses pre-service teachers’ ability to select relevant classroom practices to enhance relationship quality. Additionally, two yes-no questions assess whether the case description was believable.

5.2 Qualitative feedback

Each year post-implementation, focus group interviews are planned. Teacher educators and pre-service teachers will be invited to provide feedback on the materials in separate groups. This feedback will be used to adapt the activities and materials to ease implementation in existing teacher education programs. Additionally, the focus groups will provide us with information on implementation quality (e.g., fidelity, dosage, user adoptation; Durlak and DuPre, 2008; Meyers et al., 2012).

6 Discussion and limitations

Researchers have repeatedly voiced concerns stating that the focus of teacher education programs is too often on the classroom level rather than on relational and emotional competencies (e.g., Rucinski et al., 2018; Aspelin and Jonsson, 2019). To address these concerns, we developed a learning trajectory specifically targeting dyadic teacher-student relationships in initial (pre-)primary teacher education. Contents of the trajectory were predominantly based on attachment theory and self-determination theory and selected by experts in earlier research (Borremans and Spilt, 2023). To investigate effects of the trajectory a longitudinal, multi-cohort, quasi-experimental study is currently being conducted.

Throughout the development and implementation process so far, some limitations and opportunities for improvement have come to our attention. For instance, the trajectory was based on a specific selection of theories, including attachment theory and self-determination theory. We argue that the selected theories are the most crucial ones in targeting teachers’ dyadic relationship-building competence, as the included theories and related competencies were strategically selected by an expert panel (see Borremans and Spilt, 2023). While the learning trajectory is not exhaustive, it does provide a strong foundation for beginning teachers. Yet, additional frameworks (e.g., the theory of interpersonal teacher behavior Wubbels et al., 2012) might be valuable in courses on teacher-student relationships. Similarly, teacher educators frequently noted that the classroom context should not be overlooked. We acknowledge that it is important to consider the broader classroom climate and context in which dyadic relationships are embedded and address the distinction between classroom-level relationships and dyadic relationships within the learning trajectory. However, we chose to focus the learning trajectory specifically on dyadic teacher-student relationship as this is what is lacking most in current curricula in Flanders (Weltens, 2022). Additional frameworks and initiatives which can broaden teachers’ perspective from dyadic relationships to classroom climate, classroom management, peer relationships… might be valuable to deepen teachers’ understanding of teacher-student relationships and can for instance be included in specialized training (e.g., bachelor-after-bachelor programs) or within professional development initiatives. Relatedly, whereas the current developed learning trajectory specifically targets pre-service teachers during initial teacher education, in-service teachers might profit from preventive programs as well. The learning trajectory and related learning activities could be adapted into a professional development program to target in-service teachers and proactively strengthen their relationship-building competence.

With regard to the implementation of the trajectory, some environmental and methodological constraints need to be considered. First, we collaborated with partner university colleges for implementation of the program. These partners voluntarily participated in the project and development and implementation of the learning trajectory. The learning trajectory is currently being implemented in ‘real-life’ circumstances rather than first tested in more controlled conditions (e.g., separate components implemented by experts, ensuring fidelity). Importantly, not all teacher educators are equally familiar with the contents of the learning trajectory, nor equally convinced of the importance of including the topic of dyadic teacher-student relationship explicitly in initial teacher education, which can influence their willingness and ability to implement the learning trajectory. While the planned focus groups will provide us with some information on implementation dosage and fidelity, no specific targeted measures (e.g., recordings of lectures) were included in the design (Durlak and DuPre, 2008). To increase fidelity, we suggest adding a “train-the-trainer” module, accompanying the learning trajectory materials, as this might improve implementation quality.

A second limitation of the implementation in real-life circumstances is the risk of contamination between the two cohorts. Teacher educators are responsible for courses over multiple years of the teacher education program. Educators involved in implementing the learning trajectory might, inadvertently, refer to contents of the learning trajectory when teaching pre-service teachers in another year, possibly our control condition. However, we address this limitation by including control conditions in two different teacher education programs, where the learning trajectory will not be implemented and thus no contamination can occur.

Third, the learning trajectory is being implemented within the regular teacher education curriculum of a volunteer university college. To fit within the existing curriculum and schedule, not all parts (activities and materials) of the trajectory will be implemented in the intervention condition. Teacher educators will each year select which activities and materials they think are most valuable and feasible to include given the existing curriculum. The option to integrate the learning trajectory within existing curricula is both a strength and a potential risk. On the one hand, the learning trajectory materials can be flexibly used and adapted to the needs of the existing teacher education program. This adaptability increased the chance of the learning trajectory being implemented within an existing curriculum (Durlak and DuPre, 2008). On the other hand, “cherry-picking” might undermine the integrity and continuity of the learning trajectory. As a result, we might expect smaller effects of the learning trajectory on pre-service teachers’ relationship-building competence when it is adapted compared to when all aspects of the learning trajectory are implemented. The suggested “train-the-trainer” module might also be valuable in underscoring the importance of all aspects of the learning trajectory, to motivate teacher educators to implement the whole trajectory rather than a selection of learning activities.

Finally, although a learning trajectory can, proactively, strengthen novice teachers’ ability to establish high-quality relationships with students, these teachers could still experience challenges in building relationships with specific students, for which more targeted intervention might be necessary. In these challenging cases, the teacher should be able to receive additional support, for instance from colleagues, the care coordinator within the school, or the principal. Moreover, in some individual cases it might be necessary to consider the broader (school) system to understand the interactions between teacher and student or to target the student directly (Kranzler et al., 2020). For instance, experiences with a previous teacher can significantly impact the student’s relationship with a new teacher (Hughes et al., 2012; Spilt and Koomen, 2022). Importantly, providing pre-service teachers with a foundation of professional knowledge, situation-specific skills, and the necessary affect-motivation may decrease the barrier to ask school psychologists for help during their in-service career and may facilitate future implementation of targeted interventions such as Banking Time (Driscoll and Pianta, 2010; Williford and Pianta, 2020) or LLInC (Leerkracht Leerling Interactie Coaching in Dutch or Student Teacher Interaction Coaching, Bosman et al., 2021; Spilt et al., 2012).

7 Conclusion

It has been widely acknowledged that high-quality teacher-student relationships contribute to the well-being of students and teachers (e.g., Ansari et al., 2020a; Haldimann et al., 2023). However, research shows that building relationships with individual children can be challenging and that teacher education might need to better prepare teachers for building these relationships by sufficiently addressing dyadic teacher-student relationships during initial teacher education (Jensen et al., 2015; Borremans et al., under review). We therefore propose explicitly targeting dyadic teacher-student relationships in teacher education programs, to foster teachers’ relationship-building competence. To this end, we developed a three-year learning trajectory including several theoretical lectures as well as (observation and reflection) assignments on the topic of teacher-student relationships. The learning trajectory was developed to address teachers’ affect-motivation, knowledge, as well as situation-specific skills (Blömeke and Kaiser, 2017). Goals of the learning trajectory were selected by an independent expert panel (Borremans and Spilt, 2023) and translated into specific materials in close collaboration with partner university colleges. Quantitative and qualitative longitudinal data are being collected in a quasi-experimental multi-cohort study to assess effectiveness, implementation quality, and user satisfaction. In sum, the developed learning trajectory focusing on building high-quality relationships addresses a gap in initial (pre-)primary teacher education programs in Flanders. The trajectory therefore has the potential to strengthen initial teacher education programs, which in turn can support beginning teachers in establishing high-quality relationships with their students.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Social and Societal Ethics Committee, KU Leuven. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HK: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. JS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Research Foundation Flanders grant 1SE4921N to LB.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all participants and partners in the project for their valuable contribution, particularly Arteveldehogeschool, Hogeschool West-Vlaanderen, Odisee Hogeschool, University Colleges Leuven, and PXL Hogeschool. The authors thank Eline Wygers for her contribution to the development of specific learning materials.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1349532/full#supplementary-material

References

Aboagye, M. O., Boateng, P., Asare, K., Sekyere, F. O., Antwi, C. O., and Qin, J. (2020). Managing conflictual teacher-child relationship in pre-schools: a preliminary test of the job resources buffering-effect hypothesis in an emerging economy. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 118:105468. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105468

Alamos, P., Corbin, C. M., Klotz, M., Lowenstein, A. E., Downer, J. T., and Brown, J. L. (2022). Bidirectional associations among teachers' burnout and classroom relational climate across an academic year. J. Sch. Psychol. 95, 43–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2022.09.001

Ansari, A., Hofkens, T. L., and Pianta, R. C. (2020a). Teacher-student relationships across the first seven years of education and adolescent outcomes. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 71:101200. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2020.101200

Ansari, A., Pianta, R. C., Whittaker, J. V., Vitiello, V. E., and Ruzek, E. A. (2020b). Preschool teachers’ emotional exhaustion in relation to classroom instruction and teacher-child interactions. Early Educ. Dev. 33, 107–120. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2020.1848301

Aspelin, J., and Eklöf, A. (2022). In the blink of an eye: understanding teachers’ relational competence from a micro-sociological perspective. Classroom Discourse 14, 69–87. doi: 10.1080/19463014.2022.2072354

Aspelin, J., and Jonsson, A. (2019). Relational competence in teacher education. Concept analysis and report from a pilot study. Teach. Dev. 23, 264–283. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2019.1570323

Aspelin, J., Östlund, D., and Jönsson, A. (2020). ‘It means everything’: special educators’ perceptions of relationships and relational competence. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 36, 671–685. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2020.1783801

Aspelin, J., Östlund, D., and Jönsson, A. (2021). Pre-service special educators’ understandings of relational competence. Front. Educ. 6:678793. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.678793

Baumeister, R. F., and Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 117, 497–529. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Becker, E. S., Keller, M. M., Goetz, T., Frenzel, A. C., and Taxer, J. L. (2015). Antecedents of teachers’ emotions in the classroom: an intraindividual approach. Front. Psychol. 6:635. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00635

Beltman, S., Mansfield, C., and Price, A. (2011). Thriving not just surviving: a review of research on teacher resilience. Educ. Res. Rev. 6, 185–207. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2011.09.001

Blömeke, S., and Kaiser, G. (2017). “Understanding the development of teachers' professional competencies as personally, situationally and socially determined” in The SAGE handbook of research on teacher education. eds. D. J. Clandinin and J. Husu (London, UK: SAGE Publications) doi: 10.4135/9781529716627

Borremans, L. F. N., Deryck, A., and Spilt, J. L. (under review). "It's a way of being for a teacher": Multiple perspectives on relationship-building competencies in teacher education.

Borremans, L. F. N., and Spilt, J. L. (2022). Development of the competence measure of individual teacher-student relationships (COMMIT): insight into the attitudes, knowledge, and self-efficacy of pre-service teachers. Front. Educ. 7:831468. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.831468

Borremans, L. F. N., and Spilt, J. L. (2023). Towards a curriculum targeting teachers’ relationship-building competence: results of a Delphi study. Teach. Teach. Educ. 130:104155. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2023.104155

Borremans, L. F. N., and Spilt, J. L. (under review). Committing to all students: The role of teachers’ relationship-building competence in relationships with (non)disruptive students.

Bosman, R. J., Roorda, D. L., van der Veen, I., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2018). Teacher-student relationship quality from kindergarten to sixth grade and students' school adjustment: a person-centered approach. J. Sch. Psychol. 68, 177–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2018.03.006

Bosman, R. J., Zee, M., de Jong, P. F., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2021). Using relationship-focused reflection to improve teacher–child relationships and teachers' student-specific self-efficacy. J. Sch. Psychol. 87, 28–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2021.06.001

Bourdeaud’hui, R., Janssens, F., and Vanderhaeghe, S. (2019). Rapport: Vlaamse werkbaarheidsmonitor 2019 - werknemers [report: Flemish workability monitor 2019 - employees].

Buyse, E., Verschueren, K., Doumen, S., Van Damme, J., and Maes, F. (2008). Classroom problem behavior and teacher-child relationships in kindergarten: the moderating role of classroom climate. J. Sch. Psychol. 46, 367–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2007.06.009

Buyse, E., Verschueren, K., Verachtert, P., and Van Damme, J. (2009). Predicting school adjustment in early elementary school: impact of relationship quality and relational classroom climate. Elem. Sch. J. 110, 119–141. doi: 10.1086/605768

Chang, M.-L. (2013). Toward a theoretical model to understand teacher emotions and teacher burnout in the context of student misbehavior: appraisal, regulation and coping. Motiv. Emot. 37, 799–817. doi: 10.1007/s11031-012-9335-0

Cook, C. R., Coco, S., Zhang, Y., Fiat, A. E., Duong, M. T., Renshaw, T. L., et al. (2018). Cultivating positive teacher–student relationships: preliminary evaluation of the establish–maintain–restore (EMR) method. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 47, 226–243. doi: 10.17105/spr-2017-0025.V47-3

Corbin, C. M., Alamos, P., Lowenstein, A. E., Downer, J. T., and Brown, J. L. (2019). The role of teacher-student relationships in predicting teachers' personal accomplishment and emotional exhaustion. J. Sch. Psychol. 77, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2019.10.001

Crosnoe, R., Morrison, F., Burchinal, M., Pianta, R., Keating, D., Friedman, S. L., et al. (2010). Instruction, teacher-student relations, and math achievement trajectories in elementary school. J. Educ. Psychol. 102, 407–417. doi: 10.1037/a0017762

de Jonge, J. F. M., and de Muijnck, J. A. (2002). Waarom leraren de sector verlaten: Onderzoek naar de uitstroom uit het primair en voortgezet onderwijs [why teachers are leaving the sector: Examining the outflow from primary and secondary education]. Onderzoek voor Bedrijf en Beleid.

de Ruiter, J. A., Poorthuis, A. M. G., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2021). Teachers’ emotional labor in response to daily events with individual students: the role of teacher–student relationship quality. Teach. Teach. Educ. 107:103467. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103467

Deci, E. L., Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., and Ryan, R. M. (1991). Motivation and education: the self-determination perspective. Educ. Psychol. 26, 325–346. doi: 10.1207/s15326985ep2603&4_6

Driscoll, K. C., and Pianta, R. C. (2010). Banking time in head start: early efficacy of an intervention designed to promote supportive teacher–child relationships. Early Educ. Dev. 21, 38–64. doi: 10.1080/10409280802657449

Driscoll, K. C., Wang, L., Mashburn, A. J., and Pianta, R. C. (2011). Fostering supportive teacher-child relationships: intervention implementation in a state-funded preschool program. Early Educ. Dev. 22, 593–619. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2010.502015

Duong, M. T., Pullmann, M. D., Buntain-Ricklefs, J., Lee, K., Benjamin, K. S., Nguyen, L., et al. (2019). Brief teacher training improves student behavior and student-teacher relationships in middle school. Sch. Psychol. 34, 212–221. doi: 10.1037/spq0000296

Durlak, J. A., and DuPre, E. P. (2008). Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am. J. Community Psychol. 41, 327–350. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0

Endedijk, H. M., Breeman, L. D., van Lissa, C. J., Hendrickx, M. M. H. G., den Boer, L., and Mainhard, T. (2022). The teacher’s invisible hand: a meta-analysis of the relevance of teacher–student relationship quality for peer relationships and the contribution of student behavior. Rev. Educ. Res. 92, 370–412. doi: 10.3102/00346543211051428

Engels, M. C., Spilt, J., Denies, K., and Verschueren, K. (2021). The role of affective teacher-student relationships in adolescents’ school engagement and achievement trajectories. Learn. Instr. 75:101485. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2021.101485

Ewe, L. P., and Aspelin, J. (2021). Relational competence regarding students with ADHD – an intervention study with in-service teachers. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 37, 293–308. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2021.1872999

Gustems-Carnicer, J., Calderón, C., and Calderón-Garrido, D. (2019). Stress, coping strategies and academic achievement in teacher education students. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 42, 375–390. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2019.1576629

Haldimann, M., Morinaj, J., and Hascher, T. (2023). The role of dyadic teacher-student relationships for primary school teachers' well-being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20, 1–22. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20054053

Hastings, R. P., and Brown, T. (2002). Coping strategies and the impact of challenging behaviors on special educators' burnout. Mental Retard. 40, 148–156. doi: 10.1352/0047-6765(2002)040<0148:CSATIO>2.0.CO;2

Hughes, J. N., Wu, J. Y., Kwok, O. M., Villarreal, V., and Johnson, A. Y. (2012). Indirect effects of child reports of teacher-student relationship on achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 104, 350–365. doi: 10.1037/a0026339

Jensen, E., Skibsted, E. B., and Christensen, M. V. (2015). Educating teachers focusing on the development of reflective and relational competences. Educ. Res. Policy Prac. 14, 201–212. doi: 10.1007/s10671-015-9185-0

Jo, S. H. (2014). Teacher commitment: exploring associations with relationships and emotions. Teach. Teach. Educ. 43, 120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2014.07.004

Keller, M. M., Chang, M. L., Becker, E. S., Goetz, T., and Frenzel, A. C. (2014). Teachers' emotional experiences and exhaustion as predictors of emotional labor in the classroom: an experience sampling study. Front. Psychol. 5:1442. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01442

Kim, J. (2021). The quality of social relationships in schools and adult health: differential effects of student-student versus student-teacher relationships. Sch. Psychol. 36, 6–16. doi: 10.1037/spq0000373

Kincade, L., Cook, C., and Goerdt, A. (2020). Meta-analysis and common practice elements of universal approaches to improving student-teacher relationships. Rev. Educ. Res. 90, 710–748. doi: 10.3102/0034654320946836

Klassen, R. M., Perry, N. E., and Frenzel, A. C. (2012). Teachers' relatedness with students: an underemphasized component of teachers' basic psychological needs. J. Educ. Psychol. 104, 150–165. doi: 10.1037/a0026253

Koenen, A.-K., Borremans, L. F. N., De Vroey, A., Kelchtermans, G., and Spilt, J. L. (2021). Strengthening individual teacher-child relationships: an intervention study among student teachers in special education. Front. Educ. 6:769573. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.769573

Koenen, A.-K., Spilt, J. L., and Kelchtermans, G. (2022). Understanding teachers’ experiences of classroom relationships. Teach. Teach. Educ. 109:103573. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103573

Koenen, A.-K., Vervoort, E., Kelchtermans, G., Verschueren, K., and Spilt, J. L. (2019b). Teacher sensitivity in interaction with individual students: the role of teachers’ daily negative emotions. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 34, 514–529. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2018.1553876

Koomen, H. M. Y. (2022). Professionele pedagogische relaties vragen meer dan een warm hart [professional pedagogical relationships require more than a warm heart; oration]

Koomen, H. M. Y., Verschueren, K., van Schooten, E., Jak, S., and Pianta, R. C. (2012). Validating the student-teacher relationship scale: testing factor structure and measurement invariance across child gender and age in a Dutch sample. J. Sch. Psychol. 50, 215–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2011.09.001

Korpershoek, H., Harms, T., de Boer, H., van Kuijk, M., and Doolaard, S. (2016). A meta-analysis of the effects of classroom management strategies and classroom management programs on students' academic, behavioral, emotional, and motivational outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 86, 643–680. doi: 10.3102/0034654315626799

Kranzler, J. H., Floyd, R. G., Bray, M. A., and Demaray, M. K. (2020). Past, present, and future of research in school psychology: the biopsychosocial ecological model as an overarching framework. Sch. Psychol. 35, 419–427. doi: 10.1037/spq0000401

Liu, X. S., and Meyer, J. P. (2005). Teachers' perceptions of their jobs: a multilevel analysis of the teacher follow-up survey for 1994-95. Teach. Coll. Rec. 107, 985–1003. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9620.2005.00501.x

McGrath, K. F., and Van Bergen, P. (2015). Who, when, why and to what end? Students at risk of negative student-teacher relationships and their outcomes. Educ. Res. Rev. 14, 1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2014.12.001

McGrath, K. F., and Van Bergen, P. (2019). Attributions and emotional competence: why some teachers experience close relationships with disruptive students (and others don’t). Teach. Teach. 25, 334–357. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2019.1569511

Meyers, D. C., Durlak, J. A., and Wandersman, A. (2012). The quality implementation framework: a synthesis of critical steps in the implementation process. Am. J. Community Psychol. 50, 462–480. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9522-x

Moen, A. L., Sheridan, S. M., Schumacher, R. E., and Cheng, K. C. (2019). Early childhood student–teacher relationships: what is the role of classroom climate for children who are disadvantaged? Early Childhood Educ. J. 47, 331–341. doi: 10.1007/s10643-019-00931-x

Mombaers, T., Van Gasse, R., Vanlommel, K., and Van Petegem, P. (2023). ‘To teach or not to teach?’ An exploration of the career choices of educational professionals. Teach. Teach. 29, 788–820. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2023.2201425

Nguyen, T., Ansari, A., Pianta, R. C., Whittaker, J. V., Vitiello, V. E., and Ruzek, E. (2020). The classroom relational environment and children’s early development in preschool. Soc. Dev. 29, 1071–1091. doi: 10.1111/sode.12447

Obsuth, I., Murray, A. L., Knoll, M., Ribeaud, D., and Eisner, M. (2021). Teacher-student relationships in childhood as a protective factor against adolescent delinquency up to age 17: a propensity score matching approach. Crime Delinq. 69, 727–755. doi: 10.1177/00111287211014153

OECD . (2021). Building teachers’ well-being from primary to upper secondary education (teaching in focus, issue). Available at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/paper/722fe5cb-en

Opdenakker, M. C. J. L. (2014). Leerkracht-leerlingrelaties vanuit een motivationeel perspectief: Het belang van betrokken en ondersteunende docenten [teacher-student relationships from a motivational perspective: the importance of engaged and supportive teachers]. Pedagogische Studieën 91, 332–351.

Pianta, R. C. (1999a). Enhancing relationships between children and teachers. Washington: American Psychological Association.

Pianta, R. C. (1999b). “Supporting teachers: the key to affecting child-teacher relationships” in Enhancing relationships between children and teachers (Washington: American Psychological Association)

Pianta, R. C. (2001). Student-teacher relationship scale: Professional manual. Lutz, Germany: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Poling, D. V., Van Loan, C. L., Garwood, J. D., Zhang, S., and Riddle, D. (2022). Enhancing teacher-student relationship quality: a narrative review of school-based interventions. Educ. Res. Rev. 37:100459. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100459

Reeve, J., and Cheon, S. H. (2021). Autonomy-supportive teaching: its malleability, benefits, and potential to improve educational practice. Educ. Psychol. 56, 54–77. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2020.1862657

Robinson, C. D. (2020). I believe I can connect: Exploring teachers' relational self-efficacy and teacher-student relationships [doctoral dissertation, Harvard University]. Cambridge: Massachusetts.

Roorda, D. L., Jak, S., Zee, M., Oort, F. J., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2017). Affective teacher–student relationships and students’ engagement and achievement: a meta-analytic update and test of the mediating role of engagement. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 46, 239–261. doi: 10.17105/SPR-2017-0035.V46-3

Roorda, D. L., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2021). Student-teacher relationships and students' externalizing and internalizing behaviors: a cross-lagged study in secondary education. Child Dev. 92, 174–188. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13394

Rucinski, C. L., Brown, J. L., and Downer, J. T. (2018). Teacher–child relationships, classroom climate, and children’s social-emotional and academic development. J. Educ. Psychol. 110, 992–1004. doi: 10.1037/edu0000240

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Sabol, T. J., and Pianta, R. C. (2012). Recent trends in research on teacher-child relationships. Attach. Human Dev. 14, 213–231. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2012.672262

Skaalvik, E. M., and Skaalvik, S. (2011). Teacher job satisfaction and motivation to leave the teaching profession: relations with school context, feeling of belonging, and emotional exhaustion. Teach. Teach. Educ. 27, 1029–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2011.04.001

Spilt, J. L., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2022). Three decades of research on individual teacher-child relationships: a chronological review of prominent attachment-based themes. Front. Educ. 7:920985. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.920985

Spilt, J. L., Koomen, H. M. Y., and Thijs, J. T. (2011). Teacher wellbeing: the importance of teacher-student relationships. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 23, 457–477. doi: 10.1007/s10648-011-9170-y

Spilt, J. L., Koomen, H. M. Y., Thijs, J. T., and van der Leij, A. (2012). Supporting teacher's relationship with disruptive children: the potential of relationship-focused reflection. Attach. Human Dev. 14, 305–318. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2012.672286

Spilt, J. L., Verschueren, K., Van Minderhout, M. B. W. M., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2022). Practitioner review: dyadic teacher-child relationships: comparing theories, empirical evidence and implications for practice. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 63, 724–733. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13573

Stroet, K., Opdenakker, M.-C., and Minnaert, A. (2013). Effects of need supportive teaching on early adolescents’ motivation and engagement: a review of the literature. Educ. Res. Rev. 9, 65–87. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2012.11.003

Taxer, J. L., Becker-Kurz, B., and Frenzel, A. C. (2019). Do quality teacher–student relationships protect teachers from emotional exhaustion? The mediating role of enjoyment and anger. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 22, 209–226. doi: 10.1007/s11218-018-9468-4

ten Bokkel, I. M., Roorda, D. L., Maes, M., Verschueren, K., and Colpin, H. (2022). The role of affective teacher–student relationships in bullying and peer cictimization: a multilevel meta-analysis. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 52, 110–129. doi: 10.1080/2372966x.2022.2029218

Tschannen-Moran, M., and Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2001). Teacher efficacy: capturing an elusive construct. Teach. Teach. Educ. 17, 783–805. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1

Van der biesen, M. (2022). Relatievaardigheden in het curriculum van de Educatieve bachelor van Vlaamse hogescholen [relationship skills in the curriculum of the initial teacher education program of Flemish university colleges] [Unpublished master's thesis]. KU Leuven.

Vancraeyveldt, C., Verschueren, K., Wouters, S., Van Craeyevelt, S., Van Den Noortgate, W., and Colpin, H. (2015). Improving teacher-child relationship quality and teacher-rated behavioral adjustment amongst externalizing preschoolers: effects of a two-component intervention. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 43, 243–257. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9892-7

Verschueren, K., and Koomen, H. (2012). Teacher-child relationships from an attachment perspective. Attach. Hum. Dev. 14, 205–211. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2012.672260

Walker, S., and Graham, L. (2021). At risk students and teacher-student relationships: student characteristics, attitudes to school and classroom climate. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 25, 896–913. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1588925

Wang, H., Hall, N. C., and Taxer, J. L. (2019). Antecedents and consequences of teachers’ emotional labor: a systematic review and meta-analytic investigation. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 31, 663–698. doi: 10.1007/s10648-019-09475-3

Weltens, A. (2022). Leerkracht-leerling relaties in Vlaamse opleidingen kleuter-en lager onderwijs: Analyse van de formele curricula en competentiebeleving van studenten [teacher-student relationships in Flemish pre-primary and primary teacher education: Analysis of formal curricula and pre-service teachers' perceived competence] [unpublished master's thesis]. KU Leuven.

Weyers, J., König, J., Santagata, R., Scheiner, T., and Kaiser, G. (2023). Measuring teacher noticing: a scoping review of standardized instruments. Teach. Teach. Educ. 122:103970. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103970

Williford, A. P., and Pianta, R. C. (2020). “Banking time: a dyadic intervention to improve teacher-student relationships” in Student engagement - effective academic, behavioral, cognitive, and affective interventions at school. eds. A. L. Reschly, A. J. Pohl, and S. L. Christenson (Springer, eBook).

Wubbels, T., den Brok, P., van Tartwijk, J., and Levy, J. (2012). Interpersonal relationships in education: An overview of contemporary research. Rotterdam, the Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

Yoon, J. S. (2002). Teacher characteristics as predictors of teacher-student relationships: stress, negative affect, and self-efficacy. Soc. Behav. Pers. 30, 485–493. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2002.30.5.485

Zee, M., de Jong, P. F., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2017). From externalizing student behavior to student-specific teacher self-efficacy: the role of teacher-perceived conflict and closeness in the student–teacher relationship. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 51, 37–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.06.009

Zee, M., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2016). Teacher self-efficacy and its effects on classroom processes, student academic adjustment, and teacher well-being: a synthesis of 40 years of research. Rev. Educ. Res. 86, 981–1015. doi: 10.3102/0034654315626801

Keywords: relationship-building competence, teacher–student relationships, teacher education, curriculum development, teacher attitude, teacher self-efficacy, teacher situation-specific skills, teacher knowledge

Citation: Borremans LFN, Koomen HMY and Spilt JL (2024) Fostering teacher–student relationship-building competence: a three-year learning trajectory for initial pre-primary and primary teacher education. Front. Educ. 9:1349532. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1349532

Edited by:

Benjamin Dreer-Goethe, University of Erfurt, GermanyReviewed by:

Angelica Moè, University of Padua, ItalyZselyke Pap, West University of Timișoara, Romania

Copyright © 2024 Borremans, Koomen and Spilt. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Liedewij F. N. Borremans, bGllZGV3aWouYm9ycmVtYW5zQGt1bGV1dmVuLmJl

Liedewij F. N. Borremans

Liedewij F. N. Borremans Helma M. Y. Koomen

Helma M. Y. Koomen Jantine L. Spilt

Jantine L. Spilt