95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 20 March 2024

Sec. Higher Education

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1348775

Background: This study investigates the nuanced experiences of faculty members in higher education institutions during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Focusing on family–work conflict, job satisfaction, and personal wellbeing, the research aims to provide comprehensive insights into the challenges and adaptations encountered by faculty members amidst unprecedented disruptions.

Method: A mixed-method approach was employed, encompassing both quantitative and qualitative measures. The quantitative facet involved 82 participants who responded surveys distributed to faculty members across diverse regions of India. Concurrently, qualitative data were collected through interviews with 30 faculty members in three states. The quantitative study utilized standardized tools, while the qualitative inquiry followed a semi-structured interview schedule.

Result: Quantitative findings revealed a significant upswing in job satisfaction after institutional reopening compared to the lockdown period. However, no significant differences were observed concerning work–family conflict and personal wellbeing. Notably, faculty members reported heightened work–family and family–work interference compared to national statistics. Qualitative responses highlight a notable shift in teaching methodologies, incorporating multimedia and online tools. Faculty members exhibited mixed sentiments about returning to the office, expressed a deepened appreciation for social relationships post-reopening, and emphasized the positive impact of institutional hygiene protocols.

Conclusion: This study offers crucial insights into the multifaceted experiences of faculty members in higher institutions during the COVID-19 lockdown and subsequent reopening. The research contributes valuable perspectives to the evolving discourse on post-pandemic academia, providing a foundation for further exploration and understanding of the challenges and opportunities faced by faculty members in the changing scenario of higher education.

In March 2020, the world experienced unprecedented uncertainty, with one of the significant concerns being the disruption of the teaching-learning process due to the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the World Bank (2022), the global impact was extensive, affecting the education of approximately 1.6 billion students across 180 countries. In response, India decided to close all educational institutions in March 2020 and implement remote learning through digital platforms. This shift presented new challenges for teachers worldwide, particularly in higher education (Neuwirth et al., 2020). First, it tested teachers’ proficiency in computer and information technology, revealing a dissatisfactory status despite specific policies governing the use of information communication technologies in the Indian higher education system (Mukhopadhyay and Parhar, 2014; Irrinki, 2021). Second, the preparation of online materials, especially in non-English languages, proved to be a daunting task. Issues such as the lack of necessary Internet connectivity and smart devices added to teachers’ dissatisfaction with online education (Dayal, 2023; Singh et al., 2023). Third, teachers found themselves with the ethical responsibility of delivering teaching at their own expense, covering costs for the Internet, digital materials, equipment, and even fees for acquiring new online/digital skills. Fourth, due to a shortage of staff, many administrative responsibilities were shouldered by teachers alongside their teaching duties (Rawal, 2021; Christian et al., 2022), ranging from syllabus completion to result preparation. Certainly, it has impacted teachers’ wellbeing adversely.

The importance of a teacher’s wellbeing cannot be overstated as it plays a crucial role in their performance in the classroom. A teacher’s mental and physical health has a significant impact on their ability to establish a positive learning environment, encourage student participation, and offer effective support (Harding et al., 2019). Considering this, promoting teacher wellbeing is essential for the success of the educational system and the wellbeing of students (Evans et al., 2022). Teaching is widely acknowledged to be a demanding profession, often leading to high levels of burnout and attrition rates (Gadermann et al., 2023). However, the unprecedented and far-reaching modifications brought on by the pandemic have further compounded the already-stressful nature of the job. Studies on teacher mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic have revealed elevated levels of stress and emotional depletion among educators across several nations (Sokal et al., 2020; Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2021b; Silva et al., 2021). A notable proportion of teachers experienced physical symptoms such as neck pain, back pain, headaches, and eyestrain. Additionally, they are faced with psychological issues including stress, anxiety, and loneliness, attributed to the demands of online teaching (Dayal, 2023). Variables such as gender, age, job stability, the educational level at which they taught, and parental status negatively impacted their teaching efficiency (Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2021a; Besser et al., 2022). Overall, their enthusiasm for teaching was adversely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic (Voss et al., 2023).

The COVID-19 pandemic compelled most office-based professionals to transition to remote work, a trend that persists across various sectors (Bick et al., 2023). This transformation emphasizes the enduring impact of the pandemic on traditional work arrangements (Galanti et al., 2021). It is intuitive, as well as proven in numerous studies (Byron, 2005), that while staying at home, performing both home and office duties may interfere with each other. Work–family conflict refers to the challenges individuals face when the demands and responsibilities of their work role interfere with their family or personal life, and vice versa (Frone et al., 1997). When employment demands infiltrate family functioning, and family obligations encroach upon the workplace, it gives rise to significant work–family conflict (WFC) and family–work conflict (FWC), respectively. It involves a struggle to balance the requirements of work and family responsibilities, leading to stress and potential negative impacts on both domains (Strandh and Nordenmark, 2006). Similar to other professionals, teachers encountered the challenge of adjusting to shifts in their families and personal lives alongside changes in educational activities (Erdamar and Demirel, 2014; Solís García et al., 2021). Reports from various countries, including India, highlighted alterations in work patterns and family activities among teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic. These studies suggested that the duration of teaching and other academic work increased during COVID-19, leading to disruptions in family and social relationships (Schmidt-Crawford et al., 2021; Dayal, 2023). Studies in Western countries indicated that job stress, family conflict, and poor mental health are interconnected. WFC has been identified as a source of decreased wellbeing in several studies, and some research has also highlighted the negative impact of FWC on wellbeing, transcending cultural boundaries (Lu et al., 2006). In a study involving 12,461 married or cohabiting individuals employed in Swedish organizations, researchers explored the relationships between various factors and mental wellbeing. Although the results revealed significant associations with psychosocial working conditions, family circumstances, and WFC, it was WFC that emerged as the most influential factor in mental wellbeing (Nordenmark et al., 2020). Specific to the teaching community, Toprak et al. (2022) found that work–family conflict heightened teachers’ job stress. An Australian study with a large sample of university employees has reported that after considering job demands, the presence of work–family conflict significantly contributed to explaining the variability observed in both physical symptoms and psychological strain among individuals (Winefield et al., 2014). Zhao et al. (2022) identified that work–family conflict mediated the relationship between job stress and job burnout, with an individual’s self-efficacy for work–family playing a moderating role in this relationship.

To overcome the challenges posed by COVID-19 and maintain a semblance of normalcy, many employees transformed their homes into offices. However, this adaptation came at the cost of several compromises, with job satisfaction being one of them (Martin et al., 2022). While the shift to home offices or remote work situations has been challenging for many, leading to diminished wellbeing and a poor balance between home and family responsibilities, some argue that there may be a bright side. Previous research has presented evidence that the primary benefits of teleworking from home include increased flexibility and autonomy (Harpaz, 2002; Diab-Bahman and Al-Enzi, 2020). Thus, some studies found that employees were satisfied under remote or teleworking (Karácsony, 2021; Ahmadi et al., 2022; Prodanova and Kocarev, 2022). However, job satisfaction during COVID-19 depended on several factors (such as longevity, home workspace space, autonomy, digital social support, and monitoring mechanisms) (Petcu et al., 2021; Sousa-Uva et al., 2021; Yu and Wu, 2021), and if these were not catered, it resulted in poor job satisfaction (Feng and Savani, 2020; Balasundran et al., 2021). Furthermore, several previous studies had found that decreased job satisfaction was associated with WFC and FWC (Kalliath and Kalliath, 2015) including poor wellbeing of the workers (Armstrong et al., 2015; Haji Matarsat et al., 2021; Lim et al., 2021). Among Indian social workers, a positive relationship exists between work and family aspects. When social workers experience an improvement in their work–life balance, it correlates with higher levels of job wellbeing. Additionally, this positive impact extends further, leading to increased job satisfaction, especially when there is strong support from their families (Kalliath et al., 2019). A similar result was also seen in the Information Technology sector in India, where WFC and FWC predicted job satisfaction and wellbeing of the employees (Aboobaker and Edward, 2017). Therefore, it can be concluded that there is a close association between wellbeing, work–family conflict (including family–work conflict), and job satisfaction. Similar to other work sectors, these variables are equally crucial for understanding the work experience of the teaching community (Rahman et al., 2020).

After being closed since March 2020, institutes of higher education in India reopened for academic activities in physical mode in the second week of February 2022. Contrary to the expectation of normalization and reduction in the negative impact caused by COVID-19, teachers initially showed fear of contamination, other health-related concerns, and family- and work-related concerns in different parts of the world (Wakui et al., 2021; Ryan et al., 2023). A qualitative survey of Australian teachers (Ryan et al., 2023) reported increased workload and diminished wellbeing. Policy implementation, seen as inconsistent and burdensome, made teachers feel like ‘guinea pigs’ in the government’s public health response. This frustration was evident as teachers faced strict isolation rules in their private lives but had to teach in person, facing challenges such as inadequate hygiene measures and uncertain transmission risks from children. However, it is not clear whether almost one and half years after the reopening of the educational institutions, which were shut down due to COVID-19, what amount of normalcy has prevailed among teachers.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the experiences of faculty members in higher education in India during the COVID-19 institutional shutdown and reopening. Our review revealed a gap in the literature, with most studies focusing on the experiences of teachers in elementary or school levels, while the experiences of faculty in higher education (i.e., college and university levels) remain largely unexplored. While some studies have probed into teachers’ experiences after reopening (Wakui et al., 2021; Awwad-Tabry et al., 2023a,b; Ryan et al., 2023), the duration of observation in these studies did not exceed 6 months. This limited timeframe might be a contributing factor to the continued reporting of negative impacts by a significant portion of the teaching faculty. Thus, this study was guided by following research questions:

RQ1: Have there been any significant differences in personal well-being, family-work interference, and job satisfaction among faculty members in higher education after institutional reopening compared to the COVID-19 imposed closure?

RQ2: What are the subjective experiences of faculty members regarding post-lockdown work changes and challenges, work-life balance after returning to the office, the impact of the pandemic on work and career outlook, post-lockdown psychological status and coping, the institution’s adaptation to the post-lockdown work environment, and post-pandemic future work perspectives and views on remote work?

The COVID-19 pandemic led to a surge in online studies due to restrictions on physical contact and the convenience of distributing survey instruments digitally (Hlatshwako et al., 2021). Following this trend, our study was also designed to collect data online. However, online data collection has its drawbacks; it is susceptible to selection bias (De Man et al., 2021), careless responses (Jones et al., 2022), and low response rates (Yu et al., 2022). These limitations of the online data collections prompted us our next research question about faculty experiences with online surveys.

RQ3: What was the faculty members’ experience with online surveys?

The findings from mixed-method research studies tend to be more comprehensive than those from studies using a single method (Wisdom et al., 2012), and it provides the advantage of covering the complexity of the phenomena that cannot be tackled by a single method alone (Östlund et al., 2011). In the scenario, when quantitative and qualitative data do not match, it is an opportunity to dig deeper into each set and get stronger results (Moffatt et al., 2006). A convergent parallel design is a type of mixed-methods research design in which qualitative and quantitative data are collected concurrently but analyzed separately (Creswell and Clark, 2011). The goal is to compare or corroborate findings from both types of data to provide a comprehensive understanding of the research problem. Hence, looking at its advantages, and for a deeper understanding of the experience of the faculty members, a convergent parallel mixed-method approach was adopted in this study.

The targeted sample for this study was faculty members who were regular (permanent) employees and were working at least 2 years before the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., must have been employed since 2018 or before) in institutes of higher education (i.e., universities). For the quantitative phase of data collection, one public university was randomly drawn for sampling across all states of India from the list given on the website of the University Grant Commission (regularity bodies of Indian universities). Then, the email addresses of the faculty members were searched on the websites of the selected universities. Some states (union territory) have only one university, and, in some cases, the details of the faculty members were not available on the university website. In the case where the email addresses of the faculty members were not given on the website, another university was drawn for those particular states. Hence, faculties of 31 universities from 31 states and union territories in India were invited to participate in this study through emails.

For the qualitative inquiry, 10 faculty members who responded to the quantitative measures and 20 new faculty members were contacted in person or via telephone. All the contacted faculty members responded positively, and all the 30 faculty members were then interviewed.

This scale measures the extent of conflicting interests between work and family life (Breyer and Bluemke, 2016). It is a four-item rating scale with 4-point rating categories labeled as 1 = “several times a week,” 2 = “several times a month,” 3 = “once or twice,” and 4 = “never.” There are two items for work–family (WF) conflict because of the negative impact of work on family life, and the other two items are for conflict because of the negative impact of family life on work (FW). Items were reverse-scored such that higher scores represent higher conflict. Reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) ranges for this scale and subscales between 0.50 and 0.94 across samples of different countries as reported by Breyer and Bluemke (2016). The validity of the scale was established through criterion validity (e.g., female gender, working hours, negative impact on family, and health). In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.78 and 0.75 for WFC and FWC during the lockdown phase and 0.82 and 0.86 for WFC and FWC after reopening, respectively.

The generic job satisfaction scale measures various facets of job satisfaction, including aspects such as job stress, boredom, isolation, and danger of illness or injury (Macdonald and Maclntyre, 1997). It is a 10-item rating scale with 5-point rating categories labeled as 1 = “strongly disagree,” 2 = “disagree,” 3 = “do not know,” 4 = “agree,” and 5 = “strongly agree.” The total score is interpreted such that higher scores represent higher job satisfaction. Cronbach’s alpha for these items was 0.77 during the development of the scale. Criterion (i.e., correlation with job stress, boredom, isolation, and danger of illness or injury) validity for this scale was established. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89 during the lockdown phase and 0.92 after reopening.

Participants’ personal wellbeing was assessed using the Australian Unity Index of Subjective Well-Being (Cummins et al., 2003). Participants responded to the question “How satisfied are you with…?” in seven domain-specific areas of satisfaction (standard of living, health, achievement in life, personal relationships, how safe you feel, community connectedness, and future security) using a scale of zero to 10 (0 = completely dissatisfied to 10 = completely satisfied). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95 in both the conditions—during the lockdown phase and after reopening—in this study.

The qualitative inquiry was guided by a semi-structured interview consisting of seven questions. The questions are as follows:

Q1: How has your work style and routine changed since the lockdown restrictions were lifted? Have you found it difficult to transition back to work in the office setting? What challenges have you faced?

Q2: How have you maintained work-life balance after returning to the office?

Q3: How has the pandemic affected your overall outlook of work and career goals?

Q4: Have you noticed any changes in your mood or stress levels since returning to your office? How have you managed this situation?

Q5: How has your institution adapted to the changing work environment post-lockdown? What new policies and initiatives have been implemented?

Q6: What do you think the future of work looks like post-pandemic? Do you think that remote work will continue to be prevalent?

Q7: Have you refused any request to be a respondent to an online survey? If yes, what is your opinion? What makes faculty members respond to this?

To collect quantitative data, general information about the study, consent forms, and questionnaires were prepared in Google Form. This form was circulated by email. The first section of the form included general details of the study and information about the researcher. Interested faculty members would read the consent form and provide consent by clicking the designated tab. Afterward, they proceeded to the participant information page and the questionnaire page one by one. We aimed to collect information on measures (work–family conflict, job satisfaction, and personal wellbeing) during the COVID-19-imposed lockdown when all the educational institutes were shut along with information on the same measures after reopening of the institutions in physical mode. Thus, instructions and some of the items of the measures were modified and converted in the past tense. For example, the instruction “Recall your experience during the COVID-19 Lockdown Period (roughly between March 2020–February 2022) when your academic activities were not physically operational and answer the below given questions” was used to collect the information on measures during the COVID-19-imposed lockdown, whereas the instruction “Answer below given questions on the basis of your experience in last 10–12 months” was used to collect the information after reopening of the institutions in physical mode. The data collection took place between January 2023 and April 2023.

For qualitative inquiry, interviews were conducted by the first three authors in their respective states through one-to-one contact. Initially, participants were contacted telephonically to inquire about their readiness to participate. All contacted participants agreed to participate, and the interviews were conducted in their agreed places (i.e., office in all cases). The interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed later for further evaluation by the respective authors.

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Research Ethics and Publication Committee, S.N. Sinha College, Jehanabad, Bihar (INDIA) (Ref. No.: RP/01/SNSC).

Quantitative data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 21.0. Transcribed interviews were thematically analyzed following the guidelines outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006). This involved familiarizing ourselves with the data, generating initial codes, identifying themes, reviewing the themes, and defining and naming the themes before producing the report.

Out of the 3,987 emails sent to the faculty members, 379 could not be delivered due to various reasons, such as incorrect email IDs or being blocked by email domains. Therefore, out of the 3,608 emails that were successfully delivered, responses were obtained from only 82 faculty members of 25 states, resulting in a turnout of 2.27%. These complete responses were collected from 82 faculties, out of which 48 (58.5%) were male faculties. These faculty members held different positions: 50 (61%) were assistant professors, 18 (22%) were associate professors, and 14 (17%) were full professors. They belonged to diverse disciplines: 37 (45%) were from Arts, 9 (11%) from Engineering, and 36 (44%) from Science. The participants’ ages ranged between 28 and 63 years, with a mean age of 44.46 (SD 7.61). Regarding their experience as faculty, it varied between 48 months (4 years) and 420 months (35 years), with a mean experience of 177.94 months (SD 101).

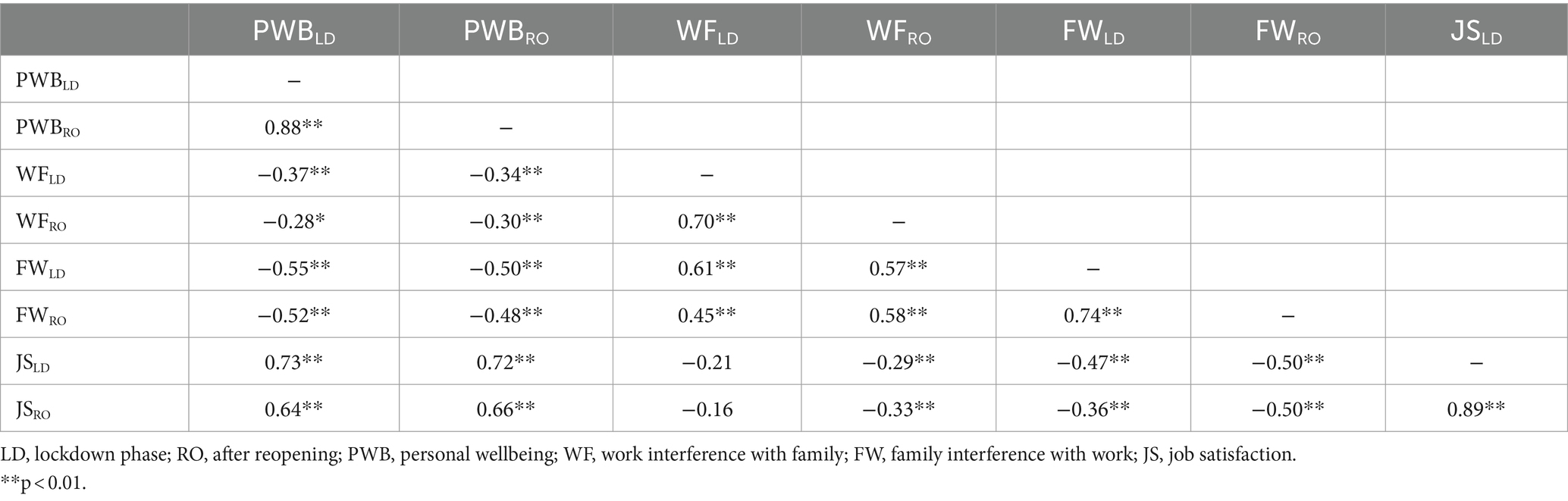

Pearson’s correlation coefficient (Table 1) for all the measured variables [viz., personal wellbeing (PWB), work interference with family (WF), family interference with work (FW), and job satisfaction] between lockdown phase and after reopening of the institutions was significantly high (r ≥ 0.70, p < 0.01). Personal wellbeing was significantly negatively correlated with WFC and FWC both during the lockdown phase and after reopening. Conversely, as expected, personal wellbeing was significantly positively correlated with job satisfaction during both the lockdown phase and after reopening.

Table 1. Correlation among measured variables at lockdown phase and after reopening of the institutions.

Comparison between the lockdown and reopening phase on PWB index, WFC, FWC, and job satisfaction suggests that there was a significant difference only in job satisfaction (Table 2). Job satisfaction was high after reopening (mean 39.34) compared to the lockdown phase (mean 38.16) [t = −3.43, p < 0.01].

As population statistics were available for work–family conflict from Breyer and Bluemke (2016), we also compared our sample participants with national data using z-test (Table 3). The result suggests that work–family conflict was significantly inflated among faculty members, compared to national data, during lockdown and after reopening.

A total of 30 faculty members [17 (57%) female members] were interviewed, who were working in different positions [15 (50%) assistant professors, 9 (30%) associate professors, and 6 (20%) full professors] and were from three Indian states [7 (23%) from Nagaland, 8 (26%) from Bihar, and 15 (50%) from West Bengal]. The age of the participants ranged between 26 and 60 years [mean 42.77 (SD 9.31)]. Initial themes and subthemes, derived from the qualitative inquiry conducted on seven questions (further details provided in Supplementary Table S1), are represented in seven major themes outlined below.

Most participants (70%) felt that their use of multimedia and information communication technologies (e.g., PowerPoint presentation: PPT and use of Internet available or self-made video tutorials) increased significantly. All these measures which they adopted during the COVID-19 lockdown, due to the closing of educational institutions in physical mode, to continue the teaching-learning process actually have now taken the form of ‘habit’ as one of the participants (female, assistant professor, 28 years old) expressed it:

“During the COVID situation, I used to teach students through PowerPoint presentations, and after this COVID, I found myself using the same PPTs in the classroom. Sometimes, I think that why I am using the same PPT, I should teach the students in more interactive ways and should use PPT less, but the habit of using PPT and online teaching is still sustaining. Now I am in the habit that before classes I should have PPT in my hand.”

Participants expressed the need to be well-equipped to address students’ diverse needs and enhance their skills in a formidable position. Feeling unrecognized during the pandemic expressed a desire for career enhancement and growth and suggested their preparations for academic recognition.

Participants (47%) highlighted increased stress levels, anxiety, and mood swings during the lockdown. This is generally related to strict university regulations and increased family responsibilities. One male associate professor (47 years) said the following:

“We were trying our best, dealing with challenges moment by moment, without dwelling too much on the future. Simultaneously, we felt a significant responsibility to complete academic and administrative assignments within the given timeframe, ensuring that service delivery reached the stakeholders. After reopening, in the physical mode, my stress level is not above normal.”

Participants experienced low stress levels because of a healthy work environment and positive relationships with colleagues. They found support from institutions and colleagues, which reduced stress, indicating the impact of a supportive work atmosphere. They also learned from others’ effective stress management, motivating them to overcome stress.

Many participants (80%) expressed that although they had adapted technology-based teaching and learning methods, which had eased their teaching, they felt that it had made their classes less interactive. They have adapted to new schedules post-lockdown and appreciated the return to official working hours, contrasting the uncertainties during the lockdown period; however, they found an increased workload at the workplace. They also expressed relief that, after reopening of the institution, their work schedule was more predictable. However, they are still apprehensive about contamination, and concerns regarding hygiene and cleanliness have significantly increased.

The participants (40%) also experienced changes in their social dynamics. COVID-19-imposed lockdown gave them the opportunity to re-establish, strengthen, and re-explore their family and social relationships, which were now missing after reopening.

One of the female assistant professors (32 years) said, “I think our kids also get adapted to the fact that mother works, office work, at home. So yes, with the support of family and adjustment from the part of everyone – kids, spouse, self – I think somehow the work-life balance is there. But yes, sometimes I do feel overwhelmed.”

The experiences regarding work–life balance after returning to the office varied widely. Challenges arise from changes in routines, commuting difficulties, and the psychological toll of balancing multiple responsibilities. Strategies such as organizational skills (time scheduling and diary maintenance), multitasking, and family support play essential roles.

“Now it is easy to maintain work like balance because I and my family know what are the different roles they can expect and what are the different time frame they can expect for me. During lock down, I was doing all sorts of work in my home apart from my official work.” (Assistant Professor, Male, 40 years).

The participants (70%) highlighted a newfound appreciation for their work and human connections. The pandemic has made them value the working culture, students, and interpersonal relationships more deeply. The subject specifically mentioned the realization of being a social animal and appreciating interactions and relationships. A female faculty from the north-east reflected the following:

“In (name of the place is masked), the lockdown felt like an unprecedented experience, akin to being confined in a jail. Although many people worldwide face daily challenges, this situation has profoundly affected us. Personally, it has transformed my perspective, fostered empathy and understanding. Now I have come to the realization that, in one word, we are social animals. I now realize the profound truth that humans are inherently social beings; we cannot thrive in closed confines. This experience has deepened my appreciation for interactions and relationships, highlighting the fundamental importance of human connection.”

Hygiene practice has improved in all institutions compared with the pre-COVID-19 situation. The institution implemented strict hygiene measures, including hand sanitization, mask-wearing, and maintenance of a clean environment.

“The humanitarian aspect was on another level, which honestly, I did not know was part of our teachers’ agenda. The teachers really helped, and the authorities ensured that. Now, we have this, I see… They were providing us with good, filtered drinking water [before COVID], but now they have given us a cooler and better facilities, including new toilets for girls… So, all these changes happened because of the COVID situation; now they understand that hygiene is very important. The staff working area has also improved, so in a way, I can say that this COVID situation has changed us for the better.” (Female, Associate Professor, 44).

Participants (70%) mentioned the institution’s emphasis on mental health by providing counseling services and resources through apps, demonstrating a proactive approach to supporting students’ mental wellbeing. As another 30-year-old female assistant professor mentioned:

“In my personal opinion, the institution has adapted very well to the post-lockdown working environment by implementing a student-friendly atmosphere, promoting awareness of personal hygiene and mental health, and enforcing a stricter policy toward misbehavior. There’s also a heightened emphasis on the academic performance of the students.”

Institutions continued to implement the online measures adopted during the lockdown period as an option for their faculty and students, as indicated by 90% of the participants. Assignments, student attendance, and numerous classes are conducted online, a practice highly valued by the participants due to the flexibility it offers, a feature lacking in the physical mode.

The majority of the participants acknowledged that remote work and hybrid (partial online work) work are likely to continue in some form post-pandemic. They pointed out the convenience, cost-effectiveness, and opportunities it offers, particularly for individuals in remote areas and working mothers. They highlighted that remote work has opened new opportunities and made work culture more flexible, leading to continued growth.

“… I think in a way this pandemic has opened opportunities and also avenues for remote working, and people have learned and adapted. So, in a way new opportunities and new work culture have come up, and I think it is to be appreciated because that makes life more flexible,” a male professor, answered.

However, 70% of participants raised concerns about the effectiveness of remote work, emphasizing that it might not be suitable for every employee or business.

Participants (47%) highlighted the inundation of online surveys, indicating that a sheer number of requests can lead to selective participation. Time constraints play a significant role in the decision-making processes. This reflects the challenges of managing a busy schedule, especially in academia where faculty members often have multiple commitments. A male assistant professor (32 years) expressed:

“To be completely honest, yes, I’ve simply ignored numerous requests for online surveys. There have been far too many of them, appearing in my inbox or in WhatsApp groups every other day. Yes, I’ve responded to those sent by people I know, but the ones from unknown senders, I’ve ignored. I believe many people lack the time or motivation to respond to all the surveys they receive, especially those from unfamiliar sources.”

However, some (30%) participants indicated their selective approach based on the relevance of the survey topic. If the subject matter aligns with their interests or expertise, they are more likely to respond accordingly. This suggests that the perceived importance and relevance of the research topic influence their participation decisions. A female assistant professor (40 years) shared her experience:

“I believe there have been occasions when I’ve said ‘yes’ and times when I’ve said ‘no’, perhaps depending on the subject matter. If the topic is not necessarily of personal interest but something I can contribute to, I’ve declined such surveys.”

Some participants (30%) also refused to participate because of doubts about the survey’s methodology, consent forms, and information about the research. This highlights the importance of transparent communication and clear explanations of the survey invitations. Faculty members, as researchers themselves, are likely to scrutinize the research design and ethical aspects before participating. It can be sensed from the expression of a male assistant professor (40 years):

“Yes, I have declined participation in online research surveys because most of the time I doubted their methodology or found the consent forms and research information lacking in detail. Since the lockdown, our emails have been inundated with numerous messages daily, making it impossible to reply to or read them all, so we must prioritize.”

In this study, we have used a mixed-method approach to understand the reflections of the faculty members working in higher education on their experience with the COVID-19-imposed shutdown of academic institutions and after the reopening of the academic institutions in physical mode. Eighty-two faulty members’ experiences on personal wellbeing index, work–family conflict, and job satisfaction were quantitatively measured with the help of standardized questionnaires for both the lockdown period and after reopening. Additionally, thirty faculty members shared their experiences of post-COVID-19 institutions reopening while reflecting upon their COVID-19 lockdown experiences in a semi-structured interview.

The study faced challenges in survey distribution, resulting in a low response rate of 2.27%. While this rate raises concerns about representativeness, it is crucial to consider the context of academia during and after the pandemic. In a survey involving 658 teachers and 945 students, 66.1% of the respondents indicated their workplace as their primary location for Internet usage, while only 19% reported using the Internet at home (Kumar and Kaur, 2006). However, back then Internet service was not so prevalent in India. Additionally, research has shown that the enforcement of mandatory stay-at-home and isolation policies amid the COVID-19 pandemic has led to increased dependence on smartphones and the Internet. This heightened reliance has, in turn, given rise to problematic Internet usage, which has been linked to sleep disturbances and psychological distress among teachers (Lee and Chen, 2021). As reported by faculty members in our study, they were inundated with various commitments, along with several requests for participation in various online surveys, which might have affected their interest and ability to engage in online research surveys comprehensively. This argument is further supported by the fact that when they were requested in person, they all volunteered to be a participant in this study.

High paired correlations for all constructs between lockdown and after reopening phases were observed. It indicates a more precise estimate of the true difference between the group means (Moore and McCabe, 1989). Our study confirms the research findings of previous studies (Lu et al., 2006; Nordenmark et al., 2020; Toprak et al., 2022) in terms of negative correlation between personal wellbeing and work–family as well as family–work conflict. Moreover, personal wellbeing was positively correlated with job satisfaction (Armstrong et al., 2015; Kalliath et al., 2019; Haji Matarsat et al., 2021; Lim et al., 2021). Interestingly, WFC during the lockdown phase was not correlated significantly with our participants’ job satisfaction at any phase (during the lockdown and after reopening). However, after reopening, WFC was significantly negatively correlated with job satisfaction after institutional reopening at both phases. For this, family support in performing official duties from home, until it was not interfering with family responsibilities, may be the plausible reason. Acceptance of the teacher’s role as an institutional tied worker by the family members was expressed by the participants in the qualitative inquiry (“I think our kids also get adapted to the fact that mother works, office work, at home. So yes, with the support of family and adjustment from the part of everyone – kids, spouse…,” a female assistant professor expressed). Contrary to this supporting scenario, when faculty members returned to their respective workplaces, they found themselves burdened again with work responsibility interfering with family. A male professor expressed:

“I am not able to manage my personal and office life has become a mess. Even after returning from the office there are lot of official work which I have to do at my home. There is no space for myself.”

Another female assistant professor expressed:

“…one good thing about the lockdown was that we were free from worries about leaving the kids at home when we were at work.”

In a comprehensive elaboration, a female professor depicted a typical Indian home scenario:

“…now I have three children so [it is] like juggling along with them; their school work, my husband, you know, and I have to keep my housekeeper happy also, that’s also a work okay, and my workplace and now because of this new educational policy again everything has changed. So, you know, sometimes it’s very difficult obviously, I am stressed out, and you know, I am in a tense situation….”

Thus, for the collective conscious Indians, family is of prime importance. The diluting role of family support in WFC to enhance job satisfaction has been also confirmed in previous studies (Kalliath et al., 2019).

Although studies have reported the negative impact of COVID-19-imposed lockdown on work–life balance (Hjálmsdóttir and Bjarnadóttir, 2021; Lonska et al., 2021; Uddin, 2021; Adisa et al., 2022), psychological wellbeing (O’Connor et al., 2021; Hutchison et al., 2022), and job satisfaction (Hong et al., 2021; Yu and Wu, 2021), in our study, we did not find any significant change after reopening in work–family conflict as well as the personal wellbeing of our participants. Quantitative measure, however, suggests that work–family interference and family–work interference among faculty members were significantly high compared to the national statistics. So, it might be the case that they already had a work–family conflict, irrespective of the pandemic lockdown. The conflict between work responsibility and family and vice versa among teaching professionals (Cinamon et al., 2007; Erdamar and Demirel, 2014), especially for female teachers (Cinamon and Rich, 2005), is not new. However, to date in India, this aspect of university teachers has not been explored well (Gopalan et al., 2020). Our study has shown that both the work to family and family to work conflict levels are significantly higher among the university faculties. Their voice became clearer as they insisted, during the qualitative inquiry, that they faced challenges in maintaining work–life balance, especially, after returning to the office. As a curative measure, faculty members mentioned that family support played vital roles in their coping. The study emphasizes the importance of recognizing and addressing the psychological toll of balancing professional and personal responsibilities, especially considering the evolving work dynamics.

A meta-analysis (Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2021a) suggested that the level of anxiety, depression, and stress was elevated among teachers during COVID-19, whereas Asian teachers have more anxiety compared to the rest of the world. Our research revealed increased stress levels, anxiety, and mood swings during the lockdown phase. However, after reopening, the stress levels normalized for most participants due to a supportive work environment and positive relationships with colleagues. This highlights the critical role of social support and a conducive workplace atmosphere in mitigating stressors.

Since COVID-19, online teaching has been made essential, especially, in higher education; it raised concern over whether traditional faculty members are ready for this rapid transition (Cutri et al., 2020; Valsaraj et al., 2021). Our qualitative inquiry suggests that there is a significant shift in teaching methods, with 70% of participants embracing multimedia and online tools. This adaptation, initiated during the lockdown, became habitual even after the reopening phase. While these tools streamlined the teaching process, concerns were raised about reduced interactivity in classrooms. In the past, it was expected that mandatory transition to online teaching could be a major issue of stress for sincere teachers willing to deliver effective learning to the students (Crawford-Ferre and Wiest, 2012; Howard et al., 2021). Faculty members in our study echoed the same and indicated a need for balanced approaches in pedagogy.

While job satisfaction among teachers in some countries, such as Turkey (Aktan and Toraman, 2022), remained high during COVID-19, this may not hold for Indian teachers. Previous studies suggested subaverage job satisfaction among Indian higher education teachers, ranging from poor to average (Katoch, 2012; Nayak and Nayak, 2014; Tahir and Sajid, 2014). The pandemic appears to have exacerbated this situation, with participants expressing a decline in job satisfaction, missing work culture, feeling unrecognized, and facing hindrances in their career goals during lockdown. However, post-reopening, they found support from institutions and colleagues, reducing stress and emphasizing the positive impact of a supportive work environment.

This first attempt, capturing the COVID-19 pandemic and aftermath experiences of Indian faculty members involved in the higher education system, has some limitations. Although effort was made to get representation from every state, including union territories, of India, the response rate in our study was very low. Previous research that employed email-based recruitment has similar findings (Murphy et al., 2020), whereas another research suggests a better response rate by email than postal mail (Tai et al., 2018). This limitation highlights the need for a cautious interpretation of the findings. Despite these challenges, the study provides valuable insights into the complex interplay between work dynamics, personal lives, and psychological wellbeing during and after the pandemic.

In our study, due to the small number of participants, we could not see the effect of faculty rank and gender. It can be expected that work responsibilities may vary rank-wise (assistant, associate, and professor). Similarly, work and family expectations may also differ between male and female participants. In future research, these limitations should be overcome for a deeper understanding and the generality of the findings.

The study identified common reasons for faculty members’ reluctance to participate in online surveys, including time constraints, relevance, and methodological concerns. Addressing these issues, such as minimizing survey frequency and ensuring transparent communication about research goals, could enhance future survey response rates.

Faculty members highly valued the implementation of rigorous hygiene protocols, which significantly enhanced the safety of their work environment. Furthermore, institutions took proactive steps to support mental health, offering counseling services and promoting a comprehensive approach to faculty wellbeing. These measures and practices should be permanently integrated into institutional frameworks, rather than being seen as temporary or precautionary initiatives.

The study participants expressed a mixed outlook regarding the future of work post-pandemic. While remote and hybrid work options were appreciated for their flexibility, concerns were raised about their effectiveness for all employees and businesses. Striking a balance between remote and physical work models emerged as a challenge, indicating the need for tailored approaches based on individual roles and preferences. Future research could explore targeted interventions to support faculty members’ mental health and work–life balance. Investigating the long-term effects of the pandemic on academic productivity and collaboration could provide valuable insights for institutions aiming to create adaptive work environments.

In conclusion, this study sheds light on the multifaceted challenges faced by faculty members during the pandemic, emphasizing the importance of supportive work environments, adaptive teaching methodologies, and a holistic approach to wellbeing. Addressing these challenges can pave the way for resilient and sustainable academic work practices in the post-pandemic era.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: Quantitative data pertaining to this study can be accessed from https://data.mendeley.com/preview/92g4pthx4p. However, qualitative data could not be made public to protect the identity and other sensitive information pertinent to the study participants.

The studies involving humans were approved by the College Ethics and Publication Committee, S.N. Sinha College, Jehanabad, Bihar (INDIA). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

RD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. IL: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. SG: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SP: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2024.1348775/full#supplementary-material

Aboobaker, N., and Edward, M. (2017). Work-family conflict and family-work conflict as predictors of psychological wellbeing, job satisfaction and family satisfaction: a structural equation model. ZENITH Int. J. Bus. Econom. Manag. Res. 7, 63–72.

Adisa, T. A., Antonacopoulou, E., Beauregard, T. A., Dickmann, M., and Adekoya, O. D. (2022). Exploring the Impact of COVID-19 on Employees’ Boundary Management and Work–Life Balance. Br. J. Manag. 33, 1694–1709. doi: 10.1111/1467-8551.12643

Ahmadi, F., Zandi, S., Cetrez, Ö. A., and Akhavan, S. (2022). Job satisfaction and challenges of working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic: a study in a Swedish academic setting. Work 71, 357–370. doi: 10.3233/WOR-210442

Aktan, O., and Toraman, Ç. (2022). The relationship between technostress levels and job satisfaction of teachers within the COVID-19 period. Educ. Inf. Technol. 27, 10429–10453. doi: 10.1007/s10639-022-11027-2

Armstrong, G. S., Atkin-Plunk, C. A., and Wells, J. (2015). The Relationship Between Work–Family Conflict, Correctional Officer Job Stress, and Job Satisfaction. Crim. Justice Behav. 42, 1066–1082. doi: 10.1177/0093854815582221

Awwad-Tabry, S., Kfir, Y., Pressley, T., and Levkovich, I. (2023a). Rising strong: the interplay between resilience, social support, and post-traumatic growth among teachers after the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID 3, 1220–1232. doi: 10.3390/covid3090086

Awwad-Tabry, S., Levkovich, I., Pressley, T., and Shinan-Altman, S. (2023b). Arab teachers’ well-being upon school reopening during COVID-19: applying the job demands-resources model. Educ. Sci. 13:418. doi: 10.3390/educsci13040418

Balasundran, K., Nallaluthan, K., Yankteshery, V., Harun, K., Lim, P. P., and Gopal, R. (2021). Work from home and work motivation of teachers job satisfaction during pandemic COVID-19. J. Int. Educ. Bus. 14, 124–143. doi: 10.37134/ibej.vol14.2.10.2021

Besser, A., Lotem, S., and Zeigler-Hill, V. (2022). Psychological stress and vocal symptoms among university professors in Israel: implications of the shift to online synchronous teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Voice 36, 291.e9–291.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2020.05.028

Bick, A., Blandin, A., and Mertens, K. (2023). Work from home before and after the COVID-19 outbreak. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 15, 1–39. doi: 10.1257/mac.20210061

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 3, 77–101.

Byron, K. (2005). A meta-analytic review of work–family conflict and its antecedents. J. Vocat. Behav. 67, 169–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2004.08.009

Christian, D. S., Sutariya, H. J., and Kagathra, K. A. (2022). Assessment of occupational stress among high school teachers of Ahmedabad City, India. Indian J. Commun. Heal. 34, 413–417. doi: 10.47203/IJCH.2022.v34i03.017

Cinamon, R. G., and Rich, Y. (2005). Work–family conflict among female teachers. T Teach. Teach. Educ. 21, 365–378. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2004.06.009

Cinamon, R. G., Rich, Y., and Westman, M. (2007). Teachers’ occupation-specific work-family conflict. Career Dev. Q. 55, 249–261. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-0045.2007.tb00081.x

Crawford-Ferre, H. G., and Wiest, L. R. (2012). Effective online instruction in higher education. Q. Rev. Distance Educ. 13, 11–14.

Creswell, J. W., and Clark, V. L. P. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research., designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Cummins, R. A., Eckersley, R., Pallant, J., van Vugt, J., and Misajon, R. (2003). Developing a National Index of subjective wellbeing: the Australian Unity wellbeing index. Soc. Indic. Res. 64, 159–190. doi: 10.1023/A:1024704320683

Cutri, R. M., Mena, J., and Whiting, E. F. (2020). Faculty readiness for online crisis teaching: transitioning to online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 43, 523–541. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2020.1815702

Dayal, S. (2023). Online education and its effect on teachers during COVID-19-a case study from India. PLoS One 18:e0282287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0282287

De Man, J., Campbell, L., Tabana, H., and Wouters, E. (2021). The pandemic of online research in times of COVID-19. BMJ Open 11:e043866. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043866

Diab-Bahman, R., and Al-Enzi, A. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on conventional work settings. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 40, 909–927. doi: 10.1108/IJSSP-07-2020-0262

Erdamar, G., and Demirel, H. (2014). Investigation of work-family, family-work conflict of the teachers. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 116, 4919–4924. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.1050

Evans, R., Bell, S., Brockman, R., Campbell, R., Copeland, L., Fisher, H., et al. (2022). Wellbeing in secondary education (WISE) study to improve the mental health and wellbeing of teachers: a complex system approach to understanding intervention acceptability. Prev. Sci. 23, 922–933. doi: 10.1007/s11121-022-01351-x

Feng, Z., and Savani, K. (2020). Covid-19 created a gender gap in perceived work productivity and job satisfaction: implications for dual-career parents working from home. Gend. Manag. 35, 719–736. doi: 10.1108/GM-07-2020-0202

Frone, M. R., Yardley, J. K., and Markel, K. S. (1997). Developing and Testing an Integrative Model of the Work–Family Interface. J. Vocat. Behav. 50, 145–167. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.1996.1577

Gadermann, A. M., Gagné Petteni, M., Molyneux, T. M., Warren, M. T., Thomson, K. C., Schonert-Reichl, K. A., et al. (2023). Teacher mental health and workplace well-being in a global crisis: learning from the challenges and supports identified by teachers one year into the COVID-19 pandemic in British Columbia, Canada. Plos one 18:e0290230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0290230

Galanti, T., Guidetti, G., Mazzei, E., Zappalà, S., and Toscano, F. (2021). Work from home during the COVID-19 outbreak: the impact on employees’ remote work productivity, engagement, and stress. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 63:e426, –e432. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002236

Gopalan, N., Pattusamy, M., and Gollakota, K. (2020). Role of support in work–family interface among university faculty in India. South Asian J. Bus. Stud. 9, 323–338. doi: 10.1108/SAJBS-11-2019-0211

Haji Matarsat, H. M., Rahman, H. A., and Abdul-Mumin, K. (2021). Work-family conflict, health status and job satisfaction among nurses. Br. J. Nurs. 30, 54–58. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2021.30.1.54

Harding, S., Morris, R., Gunnell, D., Ford, T., Hollingworth, W., Tilling, K., et al. (2019). Is teachers’ mental health and wellbeing associated with students’ mental health and wellbeing? J. Affect. Disord. 242, 180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.080

Harpaz, I. (2002). Advantages and disadvantages of telecommuting for the individual, organization and society. Work Study 51, 74–80. doi: 10.1108/00438020210418791

Hjálmsdóttir, A., and Bjarnadóttir, V. S. (2021). I have turned into a foreman here at home: families and work–life balance in times of COVID-19 in a gender equality paradise. Gender Work Organ. 28, 268–283. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12552

Hlatshwako, T. G., Shah, S. J., Kosana, P., Adebayo, E., Hendriks, J., Larsson, E. C., et al. (2021). Online health survey research during COVID-19. Lancet Digit. Health 3, e76–e77. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(21)00002-9

Hong, X., Liu, Q., and Zhang, M. (2021). Dual stressors and female pre-school teachers’ job satisfaction during the COVID-19: the mediation of work-family conflict. Front. Psychol. 12:691498. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.691498

Howard, S. K., Tondeur, J., Siddiq, F., and Scherer, R. (2021). Ready, set, go! Profiling teachers’ readiness for online teaching in secondary education. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 30, 141–158. doi: 10.1080/1475939X.2020.1839543

Hutchison, S. M., Watts, A., Gadermann, A., Oberle, E., Oberlander, T. F., Lavoie, P. M., et al. (2022). School staff and teachers during the second year of COVID-19: higher anxiety symptoms, higher psychological distress, and poorer mental health compared to the general population. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 8:100335. doi: 10.1016/j.jadr.2022.100335

Irrinki, M. K. (2021). Learning through ICT – role of Indian higher education platforms during pandemic. Libr. Philos. Pract., 1–19.

Jones, A., Earnest, J., Adam, M., Clarke, R., Yates, J., and Pennington, C. R. (2022). Careless responding in crowdsourced alcohol research: a systematic review and meta-analysis of practices and prevalence. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 30, 381–399. doi: 10.1037/pha0000546

Kalliath, P., Kalliath, T., Chan, X. W., and Chan, C. (2019). Linking Work–Family Enrichment to Job Satisfaction through Job Well-Being and Family Support: A Moderated Mediation Analysis of Social Workers across India. Br. J. Soc. Work. 49, 234–255. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcy022

Kalliath, P., and Kalliath, T. (2015). Work–Family Conflict and Its Impact on Job Satisfaction of Social Workers. Br. J. Soc. Work. 45, 241–259. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bct125

Karácsony, P. (2021). Impact of teleworking on job satisfaction among Slovakian employees in the era of COVID-19. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 19, 1–9. doi: 10.21511/ppm.19(3).2021.01

Katoch, O. R. (2012). Job satisfaction among college teachers: a study on government colleges in Jammu (J&K). Asian J. Res. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2, 164–180.

Kumar, R., and Kaur, A. (2006). Internet use by teachers and students in engineering colleges of Punjab, Haryana, and Himachal Pradesh states of India. E-JASL Electron. J. Acad. Spec. Librariansh. 7:67.

Lee, Z.-H., and Chen, I.-H. (2021). The association between problematic internet use, psychological distress, and sleep problems during COVID-19. Sleep Epidemiol. 1:100005. doi: 10.1016/j.sleepe.2021.100005

Lim, T. L., Omar, R., Ho, T. C. F., and Tee, P. K. (2021). The roles of work–family conflict and family–work conflict linking job satisfaction and turnover intention of academic staff. Aust. J. Career Dev. 30, 177–188. doi: 10.1177/10384162211068584

Lonska, J., Mietule, I., Litavniece, L., Arbidane, I., Vanadzins, I., Matisane, L., et al. (2021). Work-life balance of the employed population during the emergency situation of COVID-19 in Latvia. Front. Psychol. 12:682459. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.682459

Lu, L., Gilmour, R., Kao, S. F., and Huang, M. T. (2006). A cross-cultural study of work/family demands, work/family conflict and wellbeing: the Taiwanese vs British. Career Dev. Int. 11, 9–27. doi: 10.1108/13620430610642354

Macdonald, S., and Maclntyre, P. (1997). The generic job satisfaction scale: scale development and its correlates. Empl. Assist. Q. 13, 1–16. doi: 10.1300/J022v13n02_01

Martin, L., Hauret, L., and Fuhrer, C. (2022). Digitally transformed home office impacts on job satisfaction, job stress and job productivity. COVID-19 findings. PLoS One 17:e0265131. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0265131

Moffatt, S., White, M., Mackintosh, J., and Howel, D. (2006). Using quantitative and qualitative data in health services research – what happens when mixed method findings conflict? [ISRCTN61522618]. BMC Health Serv. Res. 6:28. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-28

Moore, D. S., and McCabe, G. P. (1989). Introduction to the practice of statistics. New York, NY, US: W H Freeman/Times Books/ Henry Holt & Co.

Mukhopadhyay, M., and Parhar, M. (2014). ICT in Indian Higher Education Administration and Management BT - ICT in Education in Global Context: Emerging Trends Report 2013–2014. in (eds. R. Huang, Kinshuk, and J. K. Price) (Springer Berlin Heidelberg), 263–283.

Murphy, C. C., Craddock Lee, S. J., Geiger, A. M., Cox, J. V., Ahn, C., Nair, R., et al. (2020). A randomized trial of mail and email recruitment strategies for a physician survey on clinical trial accrual. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 20:123. doi: 10.1186/s12874-020-01014-x

Nayak, N., and Nayak, M. (2014). A study of job satisfaction among university teachers in India. ZENITH Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 4, 30–36.

Neuwirth, L. S., Jović, S., and Mukherji, B. R. (2020). Reimagining higher education during and post-COVID-19: challenges and opportunities. J. Adult Contin. Educ. 27, 141–156. doi: 10.1177/1477971420947738

Nordenmark, M., Almén, N., and Vinberg, S. (2020). Work/family conflict of More importance than psychosocial working conditions and family conditions for mental wellbeing. Societies 10:67. doi: 10.3390/soc10030067

O’Connor, R. C., Wetherall, K., Cleare, S., McClelland, H., Melson, A. J., Niedzwiedz, C. L., et al. (2021). Mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: longitudinal analyses of adults in the UK COVID-19 Mental Health & Wellbeing study. Br. J. Psychiatry 218, 326–333. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2020.212

Östlund, U., Kidd, L., Wengström, Y., and Rowa-Dewar, N. (2011). Combining qualitative and quantitative research within mixed method research designs: a methodological review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 48, 369–383. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.10.005

Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N., Idoiaga Mondragon, N., Bueno-Notivol, J., Pérez-Moreno, M., and Santabárbara, J. (2021a). Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and stress among teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid systematic review with meta-analysis. Brain Sci. 11:1172. doi: 10.3390/brainsci11091172

Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N., Berasategi Santxo, N., Idoiaga Mondragon, N., and Dosil Santamaría, M. (2021b). The psychological state of teachers during the COVID-19 crisis: the challenge of returning to face-to-face teaching. Front. Psychol. 11:620718. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.620718

Petcu, M. A., Sobolevschi-David, M. I., Anica-Popa, A., Curea, S. C., Motofei, C., and Popescu, A. M. (2021). Multidimensional assessment of job satisfaction in telework conditions. Case study: Romania in the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustain. For. 13:8965. doi: 10.3390/su13168965

Prodanova, J., and Kocarev, L. (2022). Employees’ dedication to working from home in times of COVID-19 crisis. Manag. Decis. 60, 509–530. doi: 10.1108/MD-09-2020-1256

Rahman, M. M., Ali, N. A., Jantan, A. H., Mansor, Z. D., and Rahaman, M. S. (2020). Work to family, family to work conflicts and work family balance as predictors of job satisfaction of Malaysian academic community. J. Enterp. Commun. 14, 621–642. doi: 10.1108/JEC-05-2020-0098

Rawal, D. M. (2021). Work life balance among female school teachers [k-12] delivering online curriculum in Noida [India] during COVID: empirical study. Manag. Educ. 37, 37–45. doi: 10.1177/0892020621994303

Ryan, J., Koehler, N., Cruickshank, T., and Stanley, M. (2023). Teachers are the Guinea pigs: teacher perspectives on a sudden reopening of schools during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aust. Educ. Res., 1–17. doi: 10.1007/s13384-022-00577-6

Schmidt-Crawford, D. A., Thompson, A. D., and Lindstrom, D. L. (2021). Condolences and congratulations: COVID-19 pressures on higher education faculty. J. Digit. Learn. Teach. Educ. 37, 84–85. doi: 10.1080/21532974.2021.1911556

Silva, D. F. O., Cobucci, R. N., Lima, S. C. V. C., and de Andrade, F. B. (2021). Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and stress among teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a PRISMA-compliant systematic review. Medicine 100:e27684. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000027684

Singh, A., Gupta, K., and Yadav, V. K. (2023). Adopting e-learning facilities during COVID-19: exploring perspectives of teachers working in Indian public-funded elementary school’s. Education 51, 26–40. doi: 10.1080/03004279.2021.1948091

Sokal, L., Trudel, L. E., and Babb, J. (2020). Canadian teachers’ attitudes toward change, efficacy, and burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Educ. Res. 1:100016. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedro.2020.100016

Solís García, P., Lago Urbano, R., and Real Castelao, S. (2021). Consequences of COVID-19 confinement for teachers: family-work interactions, technostress, and perceived organizational support. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:11259. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182111259

Sousa-Uva, M., Sousa-Uva, A., e Sampayo, M. M., and Serranheira, F. (2021). Telework during the COVID-19 epidemic in Portugal and determinants of job satisfaction: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 21:2217. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12295-2

Strandh, M., and Nordenmark, M. (2006). The interference of paid work with household demands in different social policy contexts: perceived work–household conflict in Sweden, the UK, the Netherlands, Hungary, and the Czech Republic. Br. J. Sociol. 57, 597–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-4446.2006.00127.x

Tahir, S., and Sajid, S. M. (2014). Job satisfaction among college teachers: a comparative analysis. IUP J. Organ. Behav. 13, 33–50.

Tai, X., Smith, A. M., McGeer, A. J., Dubé, E., Holness, D. L., Katz, K., et al. (2018). Comparison of response rates on invitation mode of a web-based survey on influenza vaccine adverse events among healthcare workers: a pilot study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 18:59. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0524-8

Toprak, M., Tösten, R., and Elçiçek, Z. (2022). Teacher stress and work-family conflict: examining a moderation model of psychological capital. Irish Educ. Stud. 1–17. doi: 10.1080/03323315.2022.2135564.

Uddin, M. (2021). Addressing work-life balance challenges of working women during COVID-19 in Bangladesh. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 71, 7–20. doi: 10.1111/issj.12267

Valsaraj, B. P., More, B., Biju, S., Payini, V., and Pallath, V. (2021). Faculty experiences on emergency remote teaching during COVID-19: a multicentre qualitative analysis. Interact. Technol. Smart Educ. 18, 319–344. doi: 10.1108/ITSE-09-2020-0198

Voss, T., Klusmann, U., Bönke, N., Richter, D., and Kunter, M. (2023). Teachers’ emotional exhaustion and teaching enthusiasm before versus during the COVID-19 pandemic. Z. Psychol. 231, 103–114. doi: 10.1027/2151-2604/a000520

Wakui, N., Abe, S., Shirozu, S., Yamamoto, Y., Yamamura, M., Abe, Y., et al. (2021). Causes of anxiety among teachers giving face-to-face lessons after the reopening of schools during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 21, 1050–1010. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11130-y

Winefield, H. R., Boyd, C., and Winefield, A. H. (2014). Work-family conflict and well-being in university employees. J. Psychol. 148, 683–697. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2013.822343

Wisdom, J. P., Cavaleri, M. A., Onwuegbuzie, A. J., and Green, C. A. (2012). Methodological reporting in qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods health services research articles. Health Serv. Res. 47, 721–745. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01344.x

World Bank. (2022). Education and technology. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/edutech

Yu, T., Chen, J., Gu, N. Y., Hay, J. W., and Gong, C. L. (2022). Predicting panel attrition in longitudinal HRQoL surveys during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 20:104. doi: 10.1186/s12955-022-02015-8

Yu, J., and Wu, Y. (2021). The impact of enforced working from home on employee job satisfaction during COVID-19: an event system perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:13207. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182413207

Keywords: work–family conflict, job satisfaction, higher education, post-pandemic, internet use

Citation: Dewangan RL, Longkumer I, Gupta S and Pathak S (2024) Beyond (COVID-19) lockdown: faculty experiences in the post-pandemic academic landscape. Front. Educ. 9:1348775. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1348775

Received: 03 December 2023; Accepted: 05 March 2024;

Published: 20 March 2024.

Edited by:

Nilüfer Ülker, Istanbul Technical University, TürkiyeReviewed by:

Dennis Arias-Chávez, Continental University, PeruCopyright © 2024 Dewangan, Longkumer, Gupta and Pathak. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Roshan Lal Dewangan, cm9zaGFuLmRld2FuZ2FuQGtudS5hYy5pbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.