- 1Department of Language and Literature, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Yazd University, Yazd, Iran

- 2Department of English Language and Literature, Yazd University, Yazd, Iran

As artificial intelligence (AI) increasingly permeates educational landscapes, its impact on academic writing has become a subject of intense scrutiny. This research delved into the nuanced dimensions of authorship and voice in academic writing, specifically focusing on the application of OpenAI’s ChatGPT. In this study, the research team compared and contrasted an essay written by one second-year English student for a course on English literature with a similar essay produced by ChatGPT. The current research also, tried to clarify whether artificial intelligence can satisfy the formal requirements of academic writing and maintain the distinctive voice inherent in human-authored content. The examination hinges on parameters such as assertiveness, self-identification, and authorial presence. Additionally, the researchers shed light on the challenges inherent in producing AI-generated academic text. While ChatGPT presented an ability to generate contextually relevant content, the results highlighted its need for support in guaranteeing factual accuracy and capturing the complex aspects of authorship that are common in human writing. Notably, when compared to human-generated text, the AI-generated text was deficient in terms of specificity, depth, and accurate source referencing. While AI has potential as an additional tool for academic writing, this study’s findings indicated that its current capabilities—particularly in producing academic text are limited, and remain constrained. This study emphasizes upon the imperative for continued refinement and augmentation of AI models to bridge the existing gaps in achieving a more seamless integration into the academic writing landscape.

1 Introduction

In November 2022, OpenAI introduced the public with ChatGPT, the Generative Pre-trained Transformer, marking a significant milestone in the landscape of artificial intelligence (AI). Since its release, ChatGPT has garnered widespread attention and emerged as a representative case study for large language models (LLMs). As a testament to its impact, an openly acknowledged ChatGPT user at a Swedish university for academic purposes, signaling a potential challenge for educators (Hellerstedt, 2022).

The media discourse surrounding ChatGPT, extensively covered by news outlets such as The BBC (Shearing and McCallum, 2023) and the New York Times (Schulten, 2023), has primarily focused on its mechanics, limitations, and transformative potential in education. Of particular concern is the influence of ChatGPT on written assessments, raising questions about its advantages, disadvantages, and the future of traditional evaluation methods. This study, however, delves deeper into the heart of academic writing, scrutinizing the impact of ChatGPT on fundamental concepts of authorship and voice.

Traditionally, academic writing has been characterized by the individual’s expression of understanding, critical thinking, and a distinct voice that encapsulates the author’s attitude and intellectual journey. Authorship, extending beyond the act of writing, encompasses ownership, accountability, and the integrity of ideas. As AI-generated text, exemplified by ChatGPT, becomes increasingly relevant in educational contexts, it challenges these longstanding principles.

By comparing an essay written by a student for an English literature course with a comparable essay created using ChatGPT, this study seeks to further the current conversation. By synthesizing insights from the incident at media discussions, and scholarly literature, the researchers seek to explore the boundaries of authorship and voice in the context of AI-generated text and its implications for the field of English literature. Through this exploration, the research team aims to gain a deeper understanding of the evolving dynamics between human-authored and AI-generated academic writing, navigating the intricate landscape where technology intersects with the traditions of scholarly expression.

2 Literature review

The intersection of artificial intelligence (AI) and academic writing has sparked a nuanced dialog that transcends traditional boundaries of authorship and creativity. This literature review synthesizes key contributions from scholarly works to provide a comprehensive understanding of the landscape, focusing on the comparative analysis between AI-generated text, particularly represented by ChatGPT, and human-authored academic writing in the context of English literature.

2.1 The nature of writing and authorship

The foundations of writing as a form of personal expression, intertwined with creativity, cognitive processes, and the responsibility of effective communication, are expounded by Elbow (1983), Barthes (1992), and Paul and Elder (2006). The delicate balance of imagination and innovation in writing shapes a distinct voice, reflecting the author’s intellectual journey and attitude (Eagleton, 2011). This serves as the backdrop against which the advent of AI-generated text challenges traditional perspectives on authorship and the act of creation (Boden, 1998).

2.1.1 Evolution of authorship in the digital age

The statement made by McLuhan in “The Medium is the Massage” (Fiore and McLuhan, 1967) that authorship became prominent with print technology is juxtaposed with Barthes (1992) later philosophical exploration of the “death of the author.” These historical perspectives emphasize the transformative influence of technology on authorship concepts, laying the groundwork for understanding how AI might further reshape these dynamics.

2.1.2 Ethical considerations and academic integrity

Peacock and Flowerdew (2001) emphasize how critical it is to cultivate academic literacy, encompassing critical thinking and writing skills. The rise of AI-generated texts in academic settings raises ethical concerns, particularly surrounding authorship, plagiarism, and originality (Anders, 2023; Khalil and Er, 2023). The inquiry into writing essays with ChatGPT becomes crucial to evaluate its impact on students’ abilities and to address potential challenges in maintaining academic integrity (Lo, 2023).

2.1.3 Writing, technology, and AI

The interplay between technology and writing has long fascinated scholars. Foundational work by Bolter (2001) and Ong (2013), examined how emerging technologies redefined writing practices while more recent studies by Hayles (2012) and Baron (2015) evaluated the impact of digital technology on reading habits and literary creation. However, until recently, there was a gap in understanding the unique implications of AI-generated texts on academic writing (Riedl, 2016).

A recent study by Bašić et al. provided insight into this area by conducting a comparison of student-composed essays and those written with the help of ChatGPT (Basic et al., 2023). Their research centered on the efficacy of ChatGPT-3 as an essay-writing assistance tool. Interestingly, they found no significant improvement in essay quality, writing speed, or authenticity when students used ChatGPT. On the contrary, those students who wrote essays independently of the tool achieved slightly better overall scores, a phenomenon potentially attributed to overreliance of the other group on the tool or unfamiliarity with it. These findings corroborate a previous study on GPT-2 (Fyfe, 2023), where students found using the tool more challenging than simply writing directly and expressed concerns about the sources of the generated text.

This line of research resonates with principles from corpus linguistics (McEnery and Brezina, 2022), a field committed to systematically comparing language patterns across texts. A significant aspect of this comparison involves analyzing how authorship is created through voice, a key linguistic feature that contribute to originality, creativity, and adherence to academic writing conventions (Hyland, 2009).

2.1.4 Computational linguistics and authorship in the AI era

Large language models like ChatGPT are becoming more and more prominent due to recent developments in computational linguistics, especially in natural language processing (Jurafsky and Martin, 2023). The ability of these models to generate coherent and contextually appropriate text outputs prompts an investigation into their distinct voice and its implications for authorship (Brown et al., 2020). This is consistent with corpus linguistics concepts (McEnery and Brezina, 2022), emphasizing the analysis of language patterns and the creation of authorship through voice.

2.2 ChatGPT: architecture and functionality

ChatGPT, a sophisticated language model, operates on the Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT) framework, renowned for its prowess in comprehending and producing text responses that are human-like (Brown et al., 2020). Natural language processing is ChatGPT’s area of expertise as a Large Language Model (LLM) within the larger field of Artificial Intelligence (AI) (Radford et al., 2018). ChatGPT uses layers of neural networks to learn from extensive pre-training and fine-tuning on large datasets, enabling it to predict and generate text sequences (Radford et al., 2018).

With the help of an attention mechanism, ChatGPT can generate text that is both coherent and relevant to the context. This is one of its primary features. According to Vaswani et al. (2017), this mechanism allows the model to assign different weights to words in a sentence depending on their contextual relevance. It is essential to acknowledge, however, that ChatGPT lacks real-time understanding and operates solely based on pre-learned patterns and information. Despite its ability to generate impressive outputs, the model may produce inaccuracies or nonsensical responses, demonstrating awareness of context and wording in input (Bender et al., 2021).

The current iteration, ChatGPT-4, operates on a subscription basis, with earlier versions like ChatGPT-3 and 3.5 freely accessible to the public. Users typically interact with ChatGPT through a chat window-like text-based interface, where user inputs initiate text generation. Notably, ChatGPT-4 has an arbitrary limitation of 5,000 characters per prompt, posing a challenge for generating longer texts such as a 2,000 to 3,000-word essay. This limitation necessitates multiple prompts, introducing complexities in the text generation process.

2.3 Authorship in the context of ChatGPT

2.3.1 The evolving landscape

Authorship, as emphasized by Charmaz and Mitchell (1996), encapsulates the core of the writer’s voice and presence in written works. Ivanič (1998) extends this notion, positing that writing serves as a socio-political medium for expressing identity. The academic realm, however, introduces complexities, notably around the contested concept of “voice.” Tardy (2012) acknowledges the broad spectrum of meanings attributed to “voice,” while Atkinson (2001) and Biber (2006) consider it a critical language aspect shaped by genre and community constraints in academic writing.

2.3.2 ChatGPT and altered authorship dynamics

While traditional perspectives on voice and authorship highlight the human dimension, the study at hand delves into a distinctive realm— assessing voice in a ChatGPT-generated text as an authorship marker. Conventional aspects of authorship will unavoidably change as AI becomes more prevalent in writing tasks, challenging the notion of voice as an extension of the human author. As ChatGPT generates text, the representation of voice undergoes a significant transformation, raising questions about the role of individual identity in AI-authored content. This exploration into the altered dynamics of authorship in the context of ChatGPT expands the discourse on the evolving nature of writing and creativity in the era of artificial intelligence.

2.4 The voice intensity rating scale, or VIRS

To render authorial identity quantifiable, measuring the elusive concept of voice in writing becomes imperative. Methodological recommendations are provided by Tannen (1993) and Ivanič (1994), who support the use of lexical selections, syntactic structures, hedges, boosters, and personal pronouns as measurable indicators of an author’s presence and position.

This theoretical framework is operationalized in Helms-Park and Stapleton (2003) empirical study of undergraduate argumentative writing in second languages (L2). They utilize a “Voice Intensity Rating Scale” to measure voice and introduce a more comprehensive evaluation framework that includes elements such as content, structure, language use, vocabulary, mechanics, self-identification, assertiveness, repetition of the main idea, and authorial presence.

“Voice Intensity Rating Scale” has four main parts. The first, assertiveness, measures the author’s self-assurance in their writing by taking into account linguistic cues such as intensifiers and hedges that indicate conviction when making arguments. The second, self-identification, assesses how much the writer shares their point of view and focuses on how they utilize first-person pronouns and other expressions to represent their unique opinions. The third, “reiteration of the central point,” evaluates emphasis and clarity by focusing on how clearly the passage restates the main argument. The fourth factor, authorial presence and autonomy of thought, assesses how much the author’s voice is present overall as well as how autonomous their thinking is, taking into account the inclusion of opposing points of view.

Two assessors are trained to use the rating scale and provide ratings for writing samples in order to guarantee the reliability of the scale. To sum up, the instruments used in this study measure assertiveness, self-identification, reiteration of the main point, and authorial presence in addition to evaluating the overall quality of a written passage. The “Voice Intensity Rating Scale,” specifically designed for this research, proves to be an invaluable instrument for assessing the identity-related, expressive, and personal aspects of writing.

2.5 Voice in academic writing

An author’s “voice” in academic writing is a reflection of their distinct style and method of presenting data and arguments. Through vocabulary, sentence structure, tone, and point of view, this aspect reveals their character, attitude, and commitment to the topic. Academics like Matsuda and Tardy (2007) and Hyland (2018) have made substantial contributions to our comprehension of this idea.

Matsuda and Tardy promote a thorough comprehension of “voice,” stressing its subtle facets that go beyond language use and include non-discursive elements influenced by readers’ interpretations and interactions with the text. Hyland explores the function of voice in academic writing and discourse communities, suggesting that in order to build credibility and promote efficient scholarly communication, academic writing needs to have a distinct and coherent voice. The “voice” of the author thus becomes an important component of academic writing, lending the discourse a distinct identity and point of view.

2.6 Theoretical framework

The theoretical underpinning of this study is grounded in the “Voice Intensity Rating Scale” developed by Helms-Park and Stapleton, adapted to suit the specific constraints of the research. The framework is streamlined into three core concepts, each playing a pivotal role in the comparative analysis of the two texts that serve as the study’s foundation (Table 1).

2.6.1 Assertiveness

A strong commitment to one’s claims is reflected in assertiveness, which is demonstrated by the use of linguistic devices called boosters and hedges. While affirmatives like “clearly,” “definitely,” and “undoubtedly” indicate high confidence, hedges like “might,” “perhaps,” and “could” indicate uncertainty (Hyland, 2018). Determining the author’s position and the strength of their voice in the text is made possible by analyzing the frequency and presence of hedges and boosters.

2.6.2 Self-identification

Self-identification is the process through which writers utilize active voice constructions and personal pronouns in their writing. First-person pronouns (“I,” “we,”, “my,” and “our”) indicate a more intimate and involved voice, while their absence or low frequency might indicate a more objective or detached voice (Hyland, 2002).

2.6.3 Authorial presence

Authorial Presence evaluates the unique qualities and independent thought in written works that demonstrate a strong sense of individuality. While acknowledging and engaging with “counter voices,” authors express their points of view (Ramanathan and Kaplan, 1996). Engaging with multiple voices is regarded as a persuasive tactic that reinforces the reasoning behind one’s position. Additionally, unique writing features, intentional or unintentional, are scrutinized, along with the type-token ratio—a statistical measure indicating lexical diversity.

2.6.3.1 Counter voices engagement

Examines the extent to which authors engage with alternative perspectives, enhancing the persuasiveness of their arguments. As noted by Ramanathan and Kaplan, “...being able to position and advance one’s voice along with other “counter voices” is seen as a persuasive strategy that strengthens the rationality of one’s stand.” In addition to this engagement with various voices, we also study the strategies authors employ to captivate readers.

2.6.3.2 Unique writing features

Takes into account both inadvertent errors and intentional eccentricities as elements contributing to authorial presence. Consideration is given to unique writing features, including both purposeful idiosyncrasies and unintentional mistakes, as well as the type-token ratio, which is a statistical measure which can indicate the lexical diversity of a text. This measures the ratio of the number of different words (types) against the total number of words (tokens). The ratio is the number of types divided by the number of tokens.

2.6.3.3 Type-token ratio

Utilizes statistical calculation to measure the ratio of different words (types) to the total number of words (tokens), indicating lexical diversity in the text. For counting hedges, boosters, pronouns as personal markers, and the type-token ratio, an online tool called Text Inspector has been used. According to Text Inspector, it analyses your text based on the metadiscourse markers first listed by Hyland (2002), then modified by Bax et al. (2019). Hedges, boosters and pronouns are markers of meta-discourse. The type-token ratio is a statistical calculation done separately by this tool.

2.6.3.3.1 Diversity of origin

The selection of two distinct types of texts, one authored by a student (“STUDENT”) and the other generated by GPT-4 (“GPT”), ensures a comparative analysis between human-generated and AI-generated content. This diversity allows for an exploration of how authorship and voice differ in these two contexts.

2.6.3.3.2 Relevance to academic genres

The chosen texts cover six sections; introduction, realism, modernism, postmodernism, graphic novel, and conclusion, reflecting a diverse range of topics within the realm of academic writing. This breadth ensures a comprehensive evaluation of the selected parameters across different subject matters.

2.6.3.3.3 Consistency in length and structure

Ensuring both texts are divided into the same sections with a consistent structure enhances the comparability of the analysis. This allows for a focused examination of each section’s adherence to assignment requirements and the construction of authorship.

2.6.3.3.4 Practicality for evaluation

The practicality of assessing both texts using the chosen theoretical framework and tools is crucial. The texts should be manageable for analysis within the scope of the study, considering factors such as time constraints and the availability of resources.

2.6.3.4 Voice intensity rating scale (VIRS-mini) selection

2.6.3.4.1 Adaptation for simplicity

The original Helms-Park and Stapleton “Voice Intensity Rating Scale” might be extensive, potentially requiring a panel of trained assessors for a detailed evaluation. The adaptation into the VIRS-mini simplifies the framework into three primary concepts—Assertiveness, Self-Identification, and Authorial Presence. This adjustment is made to suit the scope of the study and the available resources.

2.6.3.4.2 Theoretical foundation

The Helms-Park and Stapleton framework provides a theoretical foundation for assessing voice intensity. By maintaining the core concepts while streamlining them into three key components, the VIRS-mini retains the essence of the original scale while making it more accessible for the study’s objectives.

2.6.3.4.3 Relevance to authorship construction

The three primary concepts of the VIRS-mini-Assertiveness, Self-Identification, and Authorial Presence—are chosen because they align with the study’s focus on evaluating the construction of authorship in the selected texts. These concepts offer a nuanced perspective on how authors express themselves and engage with their audience.

2.6.3.4.4 Application to different texts

The chosen concepts of Assertiveness, Self-Identification, and Authorial Presence are adaptable to various texts, making them suitable for assessing both human-generated and AI-generated content. This flexibility allows for a comparative analysis that captures the unique characteristics of each type of text.

2.6.3.4.5 Quantitative and qualitative assessment

The VIRS-mini provides a structured framework for both quantitative and qualitative assessments. It incorporates counts, frequencies, and type-token ratios for quantitative analysis, while also allowing for a qualitative evaluation of author engagement and presence.

This literature review provides a multifaceted lens through which to examine the boundaries of authorship in the context of AI-generated text and human academic writing in English literature. It underscores the historical evolution of authorship, the ethical considerations posed by AI in education, and the intricate interplay between technology and writing. As this exploration unfolds, the study positions itself at the nexus of computational linguistics and academic writing, offering a comprehensive foundation for the comparative analysis and theoretical framework that guides this research.

The research team tried to find the suitable answers for the following research questions:

1. To what degree can ChatGPT generate text that conforms to the formal requirements inherent in academic essays, including structural elements, citation protocols, and other essential components that define scholarly writing standards?

2. How identifiable and unique is the voice manifested in AI-generated text, particularly in the context of ChatGPT?

3. To what extent does the author contribute to the process of generating text through ChatGPT?

3 Methodology

3.1 Research design

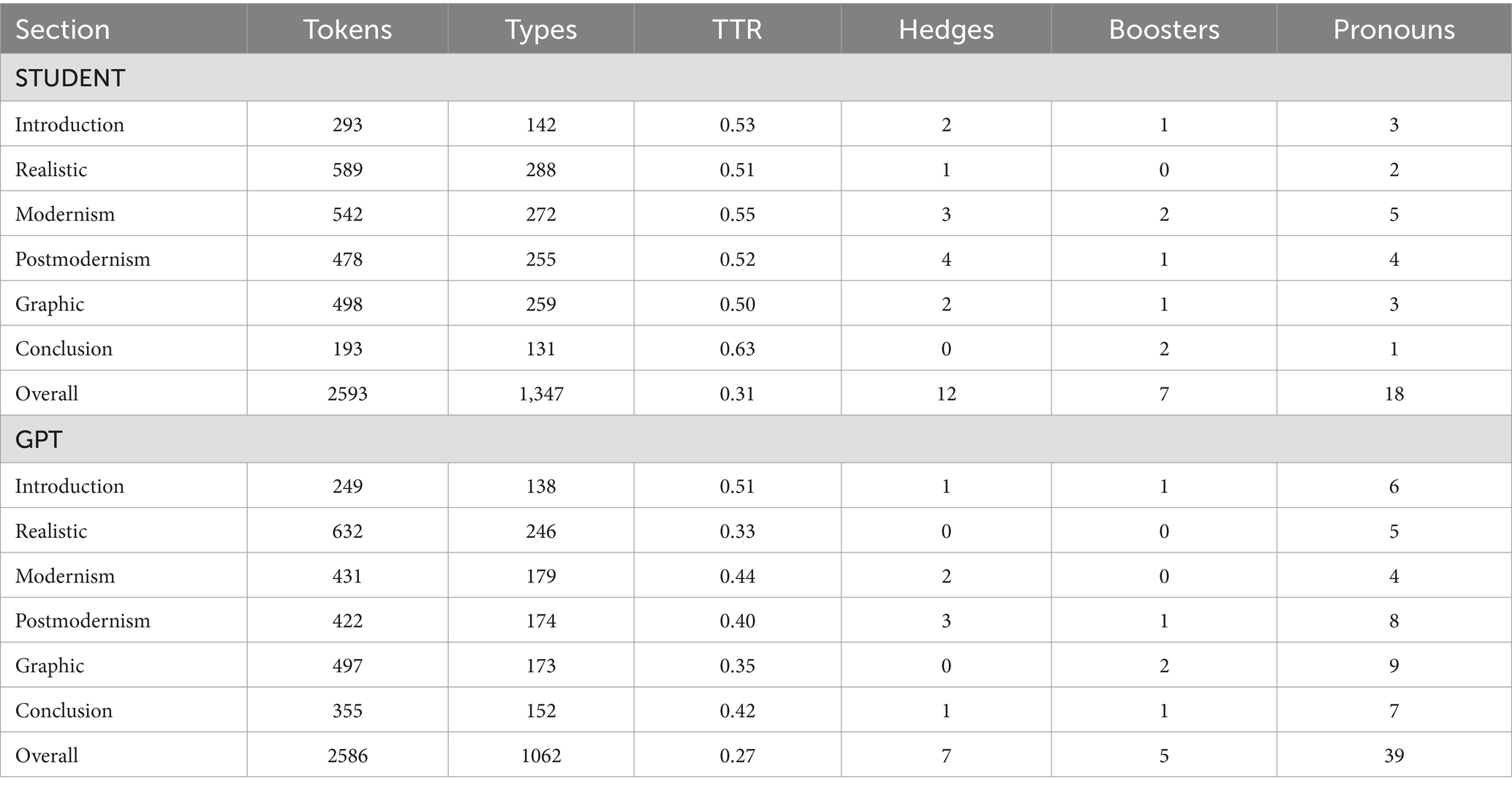

This research compared two different texts: one written by a student (called “STUDENT”) and the other produced by GPT-4 (called “GPT”). The texts were organized into six sections: introduction, graphic novel, postmodernism, modernism, realism, and conclusion. The evaluation was based on two main criteria: compliance with particular assignment requirements, which included correctness of quotes, citations, and references, and authorship construction using the VIRS-mini theoretical framework, which included assertiveness, self-identification, and authorial presence. The text Inspector tool was used to apply quantitative metrics like counts, frequencies, and type-token ratios (TTR), which were then combined with a final qualitative evaluation of the author’s presence and activity.

3.2 Criteria for the assignment and the original essay

The main focus of the study is an essay written by the student that was submitted as the last assignment for a second-year literature course in an English major program. Students were to use Ian Watt’s “apprehension of reality” and the concept of individuality from this angle in their assignment. Determining what constitutes a novel and placing realist, modernist, and postmodernist literary movements within historical periods were the main objectives. Using three novels and a graphic novel as examples, students were expected to demonstrate each literary trend with a reference to a corresponding work of fiction covered in class. Furthermore, Michael McKeon’s critical anthology “Theory of the Novel: A Historical Approach” was an essential resource.

In order to pass, students had to write a 2,000–3,000-word essay that included references from McKeon’s anthology, all three novels, and one of the two graphic novels. The SOLO taxonomy’s “relational” and “extended abstract” levels were followed for grading, with an emphasis on developing a strong thesis that is backed up by convincing data.

Evaluation for this study was based on the completion of formal requirements, which include word count, coverage of assigned novels and at least one graphic novel, development of a thesis about the novels, inclusion of at least three references from McKeon’s anthology, and appropriate referencing of sources.

3.3 How the text was generated by ChatGPT-4

The AI-generated text was produced through seven distinct writing prompts, each devoted to a particular essay section. The prompts were written using a structured formula that pictured a student majoring in English in their second year as they worked on a final essay. The prompts incorporated assignment instructions, specified sources, assumed sections were already written, and outlined the structure of the essay.

ChatGPT-4 was instructed to produce an introduction and realism sections, modernism, postmodernism, and the graphic novel (Corto Maltese), concluding with a final section. Each part was prompted with specific word limits, reference list inclusion, and adherence to MLA-style citations. The generative process was further explored in the section on results, subsection on ChatGPT’s limitations, and creating the essay.

3.4 Methodological tools

The research team used an online tool called Text Inspector for the quantitative analysis of hedges, boosters, pronouns as personal markers, and the type-token ratio. Using meta discourse markers that were first enumerated by Hyland (2009) and later updated by Bax et al. (2019), this tool analyzes the text. Pronouns, hedges, and boosters were used as meta discourse markers, and the tool computes the type-token ratio on its own. This method ensures a systematic and standardized approach to the quantitative assessment of the identified linguistic features.

3.5 Analytical method

3.5.1 Text labeling

Text labeling involved systematically categorizing and marking different components or segments within a given text to better understand its structure, content, and functions. Text labeling can be applied to identify and differentiate between the various sections, headings, and subheadings. It facilitated a systematic analysis of each section, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the content and meeting the objectives outlined in the study design. Two texts were analyzed: one created by the student (referred to as “STUDENT”) and the other by GPT-4 (referred to as “GPT”). A conclusion, a graphic novel, modernism, postmodernism, realism, and an introduction are among the sections.

3.5.2 Compliance with assignment requirements

Examining both texts closely to make sure they complied with the formal specifications outlined in the study design was the first step. This entailed evaluating the word count, discussing the assigned books and the graphic novel, incorporating McKeon’s anthology references, creating a thesis regarding the novels, and properly citing sources. The researchers carefully reviewed the references, citations, and quotes for accuracy by cross-referencing them with both digital and hard copy versions of the original sources.

3.5.3 Analysis of authorship construction using VIRS-mini-framework

The VIRS-mini framework was employed to evaluate authorship construction, focusing on assertiveness, self-identification, and authorial presence.

3.5.3.1 Assertiveness and self-identification

Linguistic markers: Text Inspector was used to count the instances of personal pronouns, boosters, and hedges. Hedges and boosters indicated the author’s level of certainty, while personal pronouns convey the level of personal engagement.

Type-token ratio: Calculated using Text Inspector, TTR provided insight into the lexical diversity in each section. The ratio was derived by dividing the number of unique words (types) by the total number of words (tokens). A lower TTR in larger texts suggests a decrease in lexical diversity.

3.5.3.2 Authorial presence

Frequency of Author’s voice: evaluating the frequency with which the author’s voice was juxtaposed with “counter voices” and other sources.

Engagement strategies: Evaluating techniques used to draw the reader in, like the use of active and passive voice, rhetorical devices, and the incorporation of unique idiosyncrasies.

Examples: Due to size constraints, a selection of examples from the texts was presented in the Results section to illustrate the analysis.

3.5.4 Cross-referencing and editing

To ensure accuracy and consistency, the text generated by the GPT has been edited and cross-referenced quotes presented in the Results to create a coherent whole.

This comprehensive analytical approach aimed to provide a nuanced understanding of how each text fulfills assignment requirements and constructs authorship across various linguistic and stylistic dimensions.

4 Findings

4.1 Regarding ChatGPT Use

This study depicts the exclusive accessibility of ChatGPT through its interface, emphasizing the pivotal role of prompts in shaping its responses. As an unfamiliar users initially, the researchers attempted to prompt ChatGPT for an entire essay faced challenges, yielding generic answers without the desired depth. Recognizing the need for detailed prompts, researchers adopted a role-playing strategy, instructing ChatGPT to simulate a second-year English student addressing the historical development of the novel.

4.1.1 Limitations of ChatGPT

Initial struggles: In our early interactions with ChatGPT, researchers encountered challenges in prompting it effectively. Initial attempts to instruct it to generate an entire essay based on the assignment instructions proved futile, resulting in generic and disconnected text lacking the required depth and supporting quotes.

Prompting strategies: To enhance the complexity and cohesion of ideas, researchers gave ChatGPT instructions to pretend to be a second-year English student. While this approach led to more intricate structures, the tool still required additional prompts for generating quotes, aligning with the assignment criteria.

Challenges in continuity: Efforts to prompt ChatGPT to “continue” often led to inconsistent results. The model either restarted from the last paragraph or initiated writing from a random point in the essay structure.

Generic outputs: Despite multiple queries to expand on generated paragraphs, ChatGPT-3.5 consistently produced general and schematic literature on the intricate literary topic. The outputs lacked the necessary depth, citations, and quotes, deviating from the task requirements.

Plagiarism concerns: In an attempt to guide ChatGPT toward the desired output, the researchers provided it with the student-written text. However, the generated text closely resembled the original, raising concerns about potential plagiarism. Even after prompting consideration for plagiarism detection, the output remained uncomfortably close to the original material.

Here is an example of ChatGPT simply rewriting the given sample:

“In contrast to its narrative predecessors, like the epic or legends, the novel dispensed with the formal conventions, and in this process, it became “formless”. In other words, the novel does not have a set structure and a checklist of points in building its narrative. The plot was transformed from repeating the same mythological or historical traditional narrative forms to being entirely made up or partially based on contemporary events.” (STUDENT, Realism).

Contrasted with:

“In comparison to earlier narrative forms, such as epics or legends, the novel broke away from traditional structures and embraced a more “formless” approach. The novel does not adhere to a specific template or list of criteria to construct its story. Instead, it shifted from retelling mythological or historical tales to creating stories based on, or inspired by, contemporary events.” (ChatGPT-3.5-generated).

Repetition of reasoning: ChatGPT-3.5 exhibited a tendency to recycle reasoning from the original essay, even in instances where it had not previously appeared in its generated text. This recurrence raised concerns about the model’s ability to generate truly original content.

These limitations underscore the challenges associated with using ChatGPT for essay generation, emphasizing the need for careful guidance and consideration of potential pitfalls such as plagiarism concerns and the model’s inclination toward repetitive content.

4.1.2 Generating the essay

Refinement in prompting strategy: The “GPT” text was exclusively generated using the ChatGPT-4 model, representing an improvement in guiding the AI through more effective prompts. A second-year English major student was writing a literature class essay on the development of the novel within its historical context, so the process involved a series of experiments with step-by-step instructions.

Structured prompts: When asked to recommend 10 pertinent sources for the essay, the AI did so, and those suggestions were added to the reference list. Subsequently, the AI was instructed to suggest word counts for every pre-established essay section. The last step was to give ChatGPT instructions on how to write each of these pre-written sections.

Usable output: Unlike previous restrictions, the generated text worked as intended, as demonstrated by the first sentence that discussed Ian Watt’s viewpoint regarding the novel’s representation of the individual’s understanding of reality.

4.2 Compliance with the assignment requirements

Formal requirements: Both “STUDENT” and “GPT” texts fulfilled key formal requirements of the assignment, including the specified word count, coverage of the required novels, presentation of arguments related to the novels, and a minimum of three McKeon’s anthology references were included.

Identification of issues: Manual cross-referencing revealed a critical issue in “GPT”—the presence of invented or “ghost” quotes. Despite the appearance of accurate citations, certain quotes, such as “The graphic novel tells a story using both text and images.,” could not be traced back to McKeon’s anthology or any other identifiable source.

Need for improved referencing: “GPT” lacks accurate referencing, as demonstrated by citing a passage from a purported 1813 publication that was attributed to Virginia Woolf. The passage was taken from Jane Austen’s book “Pride and Prejudice,” which was released in 1813, but the GPT text fails to reference this work accurately.

Requirement for accuracy: While “STUDENT” adheres to MLA format, although “GPT” had authentic quotes and appropriate referencing in the works cited section, it did not satisfy the assignment’s criteria for precise quotes and proper referencing.

These findings underscored the need for improved accuracy and reliability in ChatGPT’s ability to generate content in adherence to academic standards and assignment criteria. Addressing the identified issues was crucial for ensuring the credibility of AI-generated texts in academic settings.

4.3 Analysis of authorship construction

Type-Token ratio (TTR): TTR is a measure of lexical diversity, and the STUDENT text exhibited a higher TTR (0.31) compared to GPT (0.27). A higher TTR indicated a more diverse and richer vocabulary. The presence of the singular noun “apprehension” contributed to a lower TTR in GPT due to its frequent repetition (14 times) compared to twice in the STUDENT text.

Sectional differences: The largest difference in the number of unique words occurs in the “Graph” section, with the STUDENT text using 82 more unique words than GPT. The TTR difference in the “Conclusion” section was likely influenced by the disparity in token count, with the STUDENT conclusion being 162 tokens shorter than GPT’s.

4.3.1 Assertiveness and self-identification

The way hedges and boosters were used in the STUDENT and GPT texts varies greatly, indicating variations in assertiveness and certainty. The STUDENT text employed hedges more frequently (12 instances) compared to GPT (7), demonstrating a higher level of uncertainty. In terms of boosters, the STUDENT text features twice as many (7) as GPT (5), indicating a higher level of assertiveness.

Examples of hedges and boosters: In the STUDENT text, phrases like “almost indistinguishable” and “could be any girl” showcase the use of hedges, introducing a nuanced and tentative tone. Boosters like “clearly” in “Desiderio’s senses were clearly unreliable” enhance assertiveness. In GPT, the use of “demonstrate” in “Farewell to the Emma offered two distinct perspectives”.

Pronoun usage: Compared to the STUDENT text, which has 18 personal pronouns, GPT has nearly twice as many (39). “We” and “our” are used by both texts, creating a shared space with the reader. GPT consistently used more pronouns overall, maintaining a more personalized authorial voice. The Postmodernism section in GPT lacks “we” but includes “our,” indicating a lack of consistency in style.

Compliance with genre norms: Both texts adhered to genre norms in using personal pronouns. “We” and “our” in STUDENT create a sense of community, and the GPT’s use of “I” in the Introduction aligns with the expected personal stance prompted in its context.

Implications of pronoun usage: GPT’s higher use of personal pronouns, especially “I,” in the Introduction suggests an authorial voice that is more direct and individualized. “We” and “our” as used by the STUDENT reflects adherence to academic writing norms, maintaining neutrality and signaling less assertiveness.

These findings illuminated nuanced differences in the assertiveness, certainty, and authorial presence between the STUDENT and GPT texts, emphasizing the importance of examining linguistic markers in understanding the construction of authorship.

4.3.2 Authorial presence

Quotations and references: GPT did not have a direct quote from the novels and inaccurately attributes quote to McKeon, the editor of the anthology. In contrast, the STUDENT text correctly cited McKeon as an editor and incorporates direct quotes from various authors within the anthology. The use of accurate quotes in the student’s essay enhances its credibility and persuasiveness.

Active and passive voice: GPT predominantly used the active voice, with only one instance of passive voice in the Conclusion. The STUDENT text utilized both active and passive constructions strategically. While GPT’s limited use of passive voice may contribute to a more straightforward and direct style, the STUDENT’s varied use indicates a nuanced approach for specific emphasis and analysis.

Examples of passive constructions: The passive constructions in the STUDENT text contributed to a detailed analysis, emphasizing transformations in plot and characters. While some preferred an active voice in academic writing, the STUDENT’s use of both active and passive constructions showcases versatility and adaptability to suit content and audience.

Engaging the Reader: The student employed rhetorical questions in the introduction to prompt reader contemplation about the nature of the novel. While a grammatical error was present in a fragment sentence, it contributed to the creation of a unique authorial voice. GPT, on the other hand, exhibited factual errors, such as referencing Gormenghast in relation to Desiderio, leading to inaccuracies in content.

Modalities of engagement: GPT did not use rhetorical questions and exhibited factual errors. In contrast, the student engaged the reader with thought-provoking questions and exhibits adaptability to style, authorial presence, and versatility in writing.

Grammatical mistakes and authorial presence: The grammatical mistake in the student’s text contributed to the creation of a unique authorial voice. GPT’s factual errors, while not grammatical, diminished its credibility and highlight the importance of accurate information in maintaining a strong authorial presence.

the STUDENT text exceled in accurate citations, varied voice usage, rhetorical engagement, and maintaining a nuanced authorial presence. GPT, while generating content, struggles with accuracy in quotes, factual errors, and lacks the depth and authenticity exhibited by the student’s essay. These factors significantly impacted the overall authorial presence and effectiveness of the generated text.

5 Discussion

This study delved into the comparison between AI-generated text and human-authored text, specifically examining concepts of authorship and voice. The exploration sheds light on the challenges and limitations associated with AI tools like ChatGPT in generating coherent and nuanced academic content.

Quantitative and qualitative analyses of authorship highlight the difficulties faced by AI-generated text in preserving a recognizable and unique authorial presence. The tool, while capable of using personal pronouns like “I,” lacks genuine self-identification. The use of “I” merely reflects a prompted stance rather than an innate recognition of the tone or meaning of the text. In contrast, the type-token ratio indicates that the student’s writing has a more complex and unique style with more lexical diversity. The student’s essay has a strong sense of authorship and is written in a unique, subtle, and personalized style. When sources are used well, they fit the academic genre, leading to successful grading. The nuanced use of hedges, boosters, and a mix of active and passive voice constructions contributes to a sophisticated and balanced discourse. Repetition strategically reinforces the main thesis without compromising vocabulary diversity or nuance.

Even though the opening uses the first-person pronoun quite a bit, the AI-generated text lacks uniqueness. The overreliance on active voice constructions, limited use of hedges and boosters, and repetitive phrases contribute to a straightforward and less nuanced voice. The tool fails to present diversity and generate a sufficiently nuanced analysis of the topic. The study underscores the inherent difficulties of using AI tools for generating academic content, particularly in maintaining a nuanced authorial presence. While AI can replicate certain stylistic elements, genuine self-identification, nuanced voice, and sophisticated discourse remain challenging for these tools. Students and scholars should approach AI-generated content with caution, recognizing its limitations in capturing the intricacies of academic writing.

In the balance between human-authored and AI-generated text, this study emphasizes the unique strengths of human-authored content, characterized by a nuanced voice, diverse vocabulary, and effective use of rhetorical elements. AI-generated text, while a valuable tool for certain tasks, falls short in replicating the depth and individuality inherent in human academic writing. As technology continues to evolve, understanding these limitations becomes crucial for maintaining the integrity and authenticity of academic discourse. The current study’s conclusions, which highlight the limitations of AI-generated text in academic writing, are consistent with earlier research (Basic et al., 2023; Fyfe, 2023). Together, these studies imply that, as of the study’s time frame, artificial intelligence (AI)-generated text may not provide advantages over human-authored content in terms of essay quality, writing speed, or authenticity. Acknowledging the rapid advancements in ChatGPT and similar Large Language Models since the study’s commencement, it’s essential to recognize the dynamic nature of AI technologies. Continued improvements in these models may impact their capabilities, potentially influencing their performance in academic writing tasks. Regular reassessment through periodic studies, similar to the present one, becomes crucial to staying abreast of these developments.

The study emphasizes the challenges associated with maintaining academic integrity when incorporating AI-generated text into academic assignments. The lack of a genuine authorial presence and the potential for repetitive language highlight the risk of compromising the authenticity and originality of student work. Understanding the limitations of AI-generated text provides educators with insights into the areas where students excel in comparison. This knowledge can guide the development of educational strategies aimed at fostering nuanced writing, encouraging stylistic diversity, and promoting a more authentic authorial voice. Educators play a crucial role in assessing and grading student work.

The study suggests that reliance on AI-generated content may not necessarily result in improved essay quality. Therefore, instructors need to be discerning in their evaluation processes, considering factors such as individuality, nuance, and vocabulary diversity. Recognizing the distinct and nuanced voice present in human-generated text highlights the importance of promoting writing skills development. Institutions can focus on activities and assignments that encourage students to develop their unique writing style, enhance lexical diversity, and express complex ideas with nuance.

The study underscores the evolving nature of AI models and the need for periodic reassessment of their impact on academic writing. Educational programs should remain adaptable, incorporating new findings and adjusting curricula to equip students with the skills needed to navigate an environment where AI tools may be prevalent. Students need to develop a level of technological literacy that includes an awareness of the strengths and limitations of AI-generated text. This understanding will empower them to leverage such tools effectively while preserving their individuality and authorial voice. The call for examining AI-enabled software for identifying and classifying text has direct implications for maintaining academic integrity. If successful, these tools could assist educators in quickly identifying the origin and originality of a text, contributing to more efficient and accurate assessments.

6 Conclusion

As technology advances, the relationship between AI-generated and human-authored text in academic settings remains a dynamic field of inquiry. Continued research, adaptability to evolving AI capabilities, and exploration of innovative assessment tools will contribute to a nuanced understanding of the role AI can play in academic writing and the ongoing pursuit of academic integrity.

The study underscores the intricate nature of working with ChatGPT, emphasizing the challenges faced in attempts to generate desired outputs. It points out that the skill of effectively prompting ChatGPT is comparable to the art of writing itself. In the context of an English literature class, ChatGPT’s limitations become evident, particularly in its inability to provide accurate quotes and sources, and its tendency to introduce factual errors. The need for meticulous cross-referencing and proofreading to obtain usable text from ChatGPT makes it a challenging avenue to pursue at the present time.

The study delves into the intersection of authorship, voice, and technology in academic writing. While acknowledging the capability of AI-generated text to produce seemingly coherent outputs, the research highlights the challenges AI faces in replicating the nuanced authorship characteristics inherent in human writing, such as accurate referencing and contextual appropriateness. Despite the outward appearance of human-like writing, closer scrutiny reveals issues with register, clichéd language, and a lack of nuance.

The study suggests that the generated text, while appearing human-like at a glance, lacks the depth and authenticity of a human-authored piece. Despite efforts to get it to produce in a less generic style, the output is often cliched and generic due to the off-key register. The study raises an important question: Is it unexpected that a text produced by a machine would be referred to as having a robotic voice? The evident challenges faced in generating text for comparison underscore the current limitations of AI-generated text.

As AI-generated text becomes more prevalent, the study emphasizes the centrality of discussions around authorship, plagiarism, and originality. The findings caution against assuming that AI-generated content, while appearing cohesive, necessarily upholds the standards of nuanced and authentic human writing. This has implications for the evolving discourse on the ethical use of AI in academic contexts. Future investigations should consider conducting similar studies as ChatGPT and other AI models evolve. Comparisons using established evaluation criteria could explore the efficacy of AI-generated text against human-authored content across various topics. This approach would facilitate a nuanced understanding of the evolving landscape and the potential application of findings to diverse academic contexts. The study suggests a need for critical examination of AI-enabled software designed to identify and classify text as either human-written or generated. Investigating the methods employed in making such distinctions is vital. Moreover, assessing whether a human can achieve comparable results in discerning the origin and originality of a text would be valuable. If feasible, this capability could significantly aid educators in efficiently evaluating the authenticity of written content.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because the participation in the study was voluntary, and informed consent was provided prior to the commencement of the assignment. The anonymity of the participant was maintained throughout the study. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

FA: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MN: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AN: Investigation, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the participants who participated in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Anders, B. A. (2023). Is using ChatGPT cheating, plagiarism, both, neither, or forward thinking? Patterns 4:100694. doi: 10.1016/j.patter.2023.100694

Atkinson, D. (2001). Reflections and refractions on the JSLW special issue on voice. J. Second. Lang. Writ. 10, 7–124.

Baron, N. S. (2015). Words onscreen: The fate of reading in a digital world. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Basic, Z., Banovac, A., Kruzic, I., and Jerkovic, I. (2023). Better by you, better than me, chatgpt3 as writing assistance in students essays. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:2302.04536.

Bax, S., Nakatsuhara, F., and Waller, D. (2019). Researching L2 writers’ use of metadiscourse markers at intermediate and advanced levels. System 83, 79–95. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2019.02.010

Bender, E. M., Gebru, T., McMillan-Major, A., and Shmitchell, S. (2021). On the dangers of stochastic parrots: can language models be too big?. Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency.

Biber, D. (2006). Stance in spoken and written university registers. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 5, 97–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2006.05.001

Boden, M. A. (1998). Creativity and artificial intelligence. Artif. Intell. 103, 347–356. doi: 10.1016/S0004-3702(98)00055-1

Bolter, J. D. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print. London: Routledge.

Brown, T., Mann, B., Ryder, N., Subbiah, M., Kaplan, J. D., Dhariwal, P., et al. (2020). Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in neural information processing systems, 33, 1877–1901.

Charmaz, K., and Mitchell, R. G. (1996). The myth of silent authorship: self, substance, and style in ethnographic writing. Symb. Interact. 19, 285–302. doi: 10.1525/si.1996.19.4.285

Elbow, P. (1983). Teaching thinking by teaching writing. Magaz. High. Learn. 15, 37–40. doi: 10.1080/00091383.1983.10570005

Fyfe, P. (2023). How to cheat on your final paper: assigning AI for student writing. AI Soc., 38, 1395–1405.

Hayles, N. K. (2012). How we think: Digital media and contemporary technogenesis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Helms-Park, R., and Stapleton, P. (2003). Questioning the importance of individualized voice in undergraduate L2 argumentative writing: an empirical study with pedagogical implications. J. Second. Lang. Writ. 12, 245–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2003.08.001

Hyland, K. (2002). Options of identity in academic writing. ELT J. 56, 351–358. doi: 10.1093/elt/56.4.351

Ivanič, R. (1994). I is for interpersonal: Discoursal construction of writer identities and the teaching of writing. Linguist. Educ. 6, 3–15. doi: 10.1016/0898-5898(94)90018-3

Jurafsky, D., and Martin, J. H. (2023). Speech and language processing: An introduction to natural language processing, computational linguistics, and speech recognition.

Khalil, M., and Er, E. (2023). Will ChatGPT get you caught? Rethinking of plagiarism detection. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:2302.04335.

Lo, C. K. (2023). What is the impact of ChatGPT on education? A rapid review of the literature. Education Sciences 13:410. doi: 10.3390/educsci13040410

Matsuda, P. K., and Tardy, C. M. (2007). Voice in academic writing: the rhetorical construction of author identity in blind manuscript review. Engl. Specif. Purp. 26, 235–249. doi: 10.1016/j.esp.2006.10.001

McEnery, T., and Brezina, V. (2022). Fundamental principles of Corpus linguistics. Cambridge University Press.

Paul, R., and Elder, L. (2006). Critical thinking: the nature of critical and creative thought. J. Dev. Educ. 30:34.

Radford, A., Narasimhan, K., Salimans, T., and Sutskever, I. (2018). Improving language understanding by generative pre-training.

Ramanathan, V., and Kaplan, R. B. (1996). Audience and voice in current L1 composition texts: some implications for ESL student writers. J. Second. Lang. Writ. 5, 21–34. doi: 10.1016/S1060-3743(96)90013-2

Riedl, M. O. (2016). Computational narrative intelligence: a human-centered goal for artificial intelligence. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:1602.06484.

Schulten, K. (2023). Lesson plan: teaching and learning in the era of ChatGPT The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/24/learning/lesson-plans/lesson-plan-teaching-and-learning-in-the-era-of-chatgpt.html

Shearing, H., and McCallum, S. (2023). ChatGPT: Can students pass using AI tools at university? BBC News. Режим доступу. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/education-65316283.

Tannen, D. (1993). What’s in a frame? Surface evidence for underlying expectations. Fram. Disc. 14:56.

Tardy, C. M. (2012). “Current conceptions of voice” in Stance and voice in written academic genres. Eds. K. Hyland and C. S. Guinda (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK).

Keywords: academic writing, AI-generated text, authorship, ChatGPT, educational technology

Citation: Amirjalili F, Neysani M and Nikbakht A (2024) Exploring the boundaries of authorship: a comparative analysis of AI-generated text and human academic writing in English literature. Front. Educ. 9:1347421. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1347421

Edited by:

Carina Soledad González González, University of La Laguna, SpainReviewed by:

Valerie Harlow Shinas, Lesley University, United StatesXindong Ye, Wenzhou University, China

Copyright © 2024 Amirjalili, Neysani and Nikbakht. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Forough Amirjalili, Zi5hbWlyamFsaWxpQHlhemQuYWMuaXI=

Forough Amirjalili

Forough Amirjalili Masoud Neysani

Masoud Neysani Ahmadreza Nikbakht

Ahmadreza Nikbakht