- 1Department of Curriculum & Method of Instruct, College of Education (CEDU), United Arab Emirates University (UAEU), Al Ain, United Arab Emirates

- 2Leadership & Policy Studies in Education, Zayed University (ZU), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Criticism, or critical feedback, is considered rich bits of information about the student’s weaknesses, thinking, and learning. Despite its importance as part of formative assessment processes, this type of feedback is especially challenging for teachers to communicate as well as for students to uptake. The current conceptual analysis therefore highlights the substantial role that criticism plays in advancing students’ learning and progress. It presents a wide range of contrasting perspectives toward criticism to show how it is perceived differently. Lastly, the article identifies key provisions that are necessary for critical feedback to be constructed, presented, interpreted, and utilized in constructive and nonthreatening ways, which subsequently help trigger learner’s positive reactions and engagement with the received information. These provisions help create a community of practice where objective, informative, transparent, and engaging criticism can be given, respected, negotiated, and benefited from. The implications of these provisions for practice are discussed.

1 Introduction

A substantial body of research has widely acknowledged the centrality of feedback in formative assessment processes (Hattie and Timperley, 2007; Carless et al., 2011; McLean et al., 2015; Black and Wiliam, 2018; Ryan and Henderson, 2018; Strijbos et al., 2021). Practically speaking, teachers employ formative assessment activities regularly to obtain diagnostic data about the student’s progress toward attainment of learning objectives, as well as to identify gaps in their current learning (Harrison, 2015). They communicate this data to their students through feedback to guide and support their continuous development (Furtak, 2009). As such, formative assessment and feedback interplay with each other to enhance learning-in-process; making teaching more responsive to student’s learning needs (Black and Wiliam, 2018). Therefore, great emphasis has been given to effective feedback practices due to being one of the most powerful instructional tools that influence the development of quality teaching and learning (Zhang and Zheng, 2018; Strijbos et al., 2021). Besides, it is increasingly becoming an area of focus for educators in educational policy documents and professional development programs (Winstone et al., 2019).

Generally, there are different types of feedback according to the purposes they serve. These are well documented in the literature and have been categorized by many scholars (e.g., Hattie and Timperley, 2007; Cengiz and Ayvaci, 2017; Pollari, 2017; Rabbani et al., 2023). For instance, explanatory feedback is used to justify errors, demonstrate ideal answers or model approaches, challenge student’s preconceptions, engage in thinking, and provide supportive guidance for improvement. Whereas positive feedback acknowledges and appreciates the strengths in the students’ work for encouragement. In contrast, criticism, which is known as negative or critical feedback, targets the student’s mistakes and weaknesses so they become aware of the problems and shortcomings in their work or performance (Elsayed and Cakir, 2023). Surprisingly, some students may tend to value criticism more than positive feedback and consider it far more useful although the latter is more pleasant to hear (Zhang and Zheng, 2018). This is possibly because critical comments draw students’ attention to the gaps in their learning (Brookhart, 2008), which fulfills their curiosity to know what was wrong compared to receiving confirmatory feedback on what was done right (Can and Walker, 2014). When students capitalize on the criticism they build new learning experiences, expand their skills, and develop more sophisticated understandings (Han and Xu, 2021). There is even evidence implying that most dramatic improvements in student performance often occur because of critical comments (Alt et al., 2023).

Although criticism may act as powerful and supportive information, some students might find it difficult to accept (Esterhazy and Damşa, 2019), even for those comments that are subtly crafted and well-intended. For instance, many teachers across different learning stages and academic subjects experienced cases in which their students took their critique personally and failed to deal with it objectively (Nash and Winstone, 2017; Carless and Boud, 2018). The situation becomes more complicated when the criticism is accompanied by an unexpected grade or unjustified evaluation, which may cause students to lose motivation to improve (Weaver, 2006). It’s therefore logical to expect that students may demonstrate different feelings and divergent attitudes toward critical comments, both positive and negative (Zhang and Zheng, 2018). Accordingly, criticism might be especially challenging for teachers to communicate as well as for students to uptake when compared to the other types of feedback. This is problematic because negative and unproductive engagement with criticism limits its contribution as a formative assessment tool with concerning students’ learning (Strijbos et al., 2021).

Taking this concern as a base, the student’s unproductive engagement with criticism, the current conceptual analysis confines its attention to criticism as one common form of feedback. It begins by highlighting the substantial role that criticism plays in advancing student’s learning and progress as part of formative assessment processes. The next section attracts attention to the controversy that surrounds criticism by presenting the different standpoints toward it to showcase how it might be perceived differently, along with a discussion of how the students’ mindset may contribute to these variations. Lastly, and to aid the professional practice, one significant contribution of this work involves identifying key provisions that support the enactment of criticism in an efficient way. These highlight best practices and courses of action that are necessary for critical feedback to be constructed, presented, interpreted, and utilized in constructive and nonthreatening ways. Subsequently, they help trigger learner’s positive reactions and foster their productive engagement with criticism. These objectives can therefore be restated as follows:

highlight the importance of criticism as part of formative assessment processes,

(1) present contrasting perspectives on criticism,

(2) discuss how the students’ mindset may contribute to variations toward criticism,

(3) list key provisions for improving criticism practices.

For the purposes of our analysis, this review draws on literature pertaining to engagement with feedback in the teaching and learning contexts as situated within the larger domain of formative assessment (e.g., Ali et al., 2015; Carless and Boud, 2018; Han and Xu, 2021; Man et al., 2021; To, 2022; Carless and Winstone, 2023). A specific focus has been paid to findings relevant to criticism that is given by educators (e.g., teachers or university lecturers) to learners. Within this scope, peer-reviewed studies conducted at the school, college, or higher education settings were considered. Studies that targeted criticism practices with the aim of improving teacher’s performance or those relating to employees at the workplace were however beyond the remit of this work.

2 Fostering student engagement with criticism feedback

2.1 Importance of criticism as part of formative assessment

In the teaching and learning context, formative assessment, which is commonly known as Assessment for Learning (AFL), is considered a highly impactful teaching tool and a routine-based practice in classrooms across different learning stages (Winstone et al., 2021). It aims at gathering data to tackle the learners’ current state of learning and on-going progress (Winstone et al., 2021). Unlike summative assessment which measures the students’ academic achievement at the end of an instructional unit, term, or school year against standardized criteria or benchmarks (Black and Wiliam, 2018), formative assessment is a day-to-day practice that assesses the student’s knowledge and skill on particular concepts or areas of the learning subject. It enables teachers to identify gaps in learning that need immediate support (Walker, 2009), which in turn, informs teaching and guides their instructional decisions (Ryan and Henderson, 2018). It may target either the individual student, a group of students, or the class as a whole and it can be conducted through various strategies such as questioning, learning activities, and short quizzes, besides peer and self-assessment.

Importantly, providing responsive and targeted information to students based on assessment data is the most vital action in the formative assessment processes (Sadler, 2010). This is because students need to be aware of how well they are doing and what they ought to do next to improve (Price et al., 2010). As such, informing learners about their results fosters their improvement in an ongoing and incremental manner (Carless, 2019). Teachers communicate this post-response information through feedback (Carless, 2019) whether it is written manually (text-based feedback), provided face-to-face (oral feedback), or posted online (e.g., digital audio or computer-based feedback) (Sadler, 2010). Feedback may also come in the form of a grade an explanation, advice, praise, or criticism.

Specifically, criticism feedback is used to acknowledge students about the mistakes and weaknesses in their work or performance (Price et al., 2010). It informs the student whether or not what they are doing is correct and is on the right path (Gamlem and Smith, 2013). This type of feedback is powerful because it signals errors which are considered critical bits of information about the students’ thinking (Zhang and Zheng, 2018). In principle, errors help reveal misconceptions in understanding (Ryan and Henderson, 2018), point out inconsistencies in thinking, as well as reflect incomplete or disorganized knowledge (Furtak, 2009). In support of that, Bennett (2011) explained that errors in student’s work may be an indication of having a misconception (a naïve view) or may result from misunderstanding (confused knowledge). Critically, teachers need to attract the student’s attention to these errors in the criticism. This practice can guide students to notice their own errors so they can intentionally and thoughtfully analyze them (Man et al., 2021). Criticism therefore fosters students to perform self-correction while trying to figure out the reasons for the addressed errors, which has important implications at the short and long run. For instance, when students start to perceive their errors and weaknesses as obstacles that could potentially impede their forward movement and impact their grades, they would give them the proper attention while working out on the received criticism to avoid making these errors again in the future work or assignments (Pollari, 2017). Accordingly, providing criticism feedback is indeed a valuable opportunity to encourage students to regulate their own learning while detecting and recovering their deficiencies to attain progress (Cengiz and Ayvaci, 2017). Under this condition, they become more confident in making evaluative judgements about the quality of their work (Carless and Winstone, 2023).

2.2 Contrasting perspectives on criticism

Students may have conceptual distinctions toward different kinds of feedback (Gamlem and Smith, 2013). Specifically, considerable arguments are going in the literature over the advantages and disadvantages of criticism (Nash and Winstone, 2017; Dawson et al., 2019; Adams et al., 2020). This was attributed to the existence of a wide range of standpoints and contrasting views toward criticism, which is common in academia. Addressing these multiple ways of thinking and behaving concerning criticism illuminates a better understanding of the controversy that surrounds criticism.

Noticeably, positive perspectives about criticism are well grounded in research. The most commonly embraced belief is that criticism is a powerful means of improvement as it directs the students to learn from and build on their own mistakes, which is an integral aspect of the learning process (Dawson et al., 2019). Thus, criticism is seen as the sprout of new or alternative ideas (Cengiz and Ayvaci, 2017). It is a great opportunity to extend lines of thought and reach for unexpected solutions (Adams et al., 2020). Criticism was also considered advantageous because it questions the information from a different point of view, allowing the students to view the different dimensions of the problem being addressed (Ryan and Henderson, 2018). It was also perceived as an individually-matching challenge (McLean et al., 2015) and it should be taken objectively and constructively. Ideally, students who value criticism openly listen to it and seek to argue and discuss its validity further with the teacher (Dawson et al., 2019). Having such an understanding is necessary to be able to internalize and deal with criticism, which is an indicator of positive engagement, as well as reflects active curiosity about learning and striving for progress (Ryan and Henderson, 2018).

Nevertheless, criticism might be seen in a negative sense, even if it contains justifiable analysis and insightful information. Findings from previous research have demonstrated that criticizing own work and revealing learning errors and defects is not always welcomed by the students (Cengiz and Ayvaci, 2017). For instance, criticism might be taken as a judgement of academic potential and success, or as a sign of weakness (Pitt et al., 2020). This should not be a surprise because encountering own weaknesses may stimulate feelings of embarrassment, frustration, discouragement, and anger (Mahfoodh, 2017), thus, could be transformed into a painful experience that is challenging at the emotional level (Zhang and Zheng, 2018). In this regard, Gibbs and Simpson (2005) found that critical comments might cause a loss of confidence and diminish the student’s self-esteem and their perceived self-efficacy. This is especially true in the case of receiving criticism over and over again, which reinforces the negative beliefs the students might have about their abilities (Carvalho et al., 2014). Eventually, these negative experiences contribute to the student’s disengagement with feedback (Ryan and Henderson, 2018).

There is evidence also indicating an association between criticism and negative attitudes (Pitt et al., 2020). Weaver (2006) pointed out that students might misinterpret criticism, take it personally, or suspect it to be biased. They may show defensive or aggressive reactions against the teacher who provided the comments (Ryan and Henderson, 2018). In other scenarios, they may simply decide to ignore or reject the feedback in order to protect their self-image at the expense of improvement (Molloy et al., 2020). Such dispositions, overall, result from the lack of emotional maturity and resilience in dealing with critical feedback (Molloy et al., 2020).

Different views also exist between written criticism and oral in terms of practical applications and impact. Some views find written criticism is superior to oral because it allows the student to take their time to absorb the information. They can even record the comments and keep them as a point of reference to refer to in the future whenever needed, especially for quality remarks (Brookhart, 2008). Written criticism is also beneficial for teachers since they can write the message at their convenience. Meaning that it can be revised or rewritten; resulting in deeper reflection and a more precise selection of the words (Bruno and Santos, 2010). Additionally, privacy can be better ensured when criticism is written directly on the student’s work or when the comment is posted to the individual student in the case of E-feedback (online feedback). Providing individual-based written criticism however is time-consuming because each message should convey a great deal of informative and differentiated information in a few little words as much as possible (Mutch, 2003). Generally, written comments should be constructed with caution because they are not supported by visual elements (e.g., the tone of the voice, body language, and facial expressions) (Cengiz and Ayvaci, 2017) which are necessary to ensure that the message is correctly conveyed as intended and not misinterpreted. On the other hand, when criticism is communicated orally and face-to-face, students can receive instant responses and on-the-spot information. Likewise, they can respond to the teacher right away. Therefore, oral criticism helps facilitate direct interaction which generates empathy and creates trust (Carless and Boud, 2018). Nevertheless, oral feedback is more likely to be forgotten especially when it contains many details and is being said in a hurry, such as in the middle of an activity. Regardless of these advantages and disadvantages, providing constructive written and oral criticism is challenging and needs to be dealt with carefully. Indeed, the teachers’ competence, experience, and feedback literacy determine the degree to which criticism can be impactful (Winstone et al., 2019).

Overall, the different perspectives and attitudes toward criticism, whether positive or negative, have important pedagogical implications as they suggest several courses of action for the use of criticism as part of formative assessment processes in the classroom.

2.3 The students’ mindset and variations toward criticism

As explained above, it becomes clear that some students may have more informed perceptions and positive behaviors toward criticism than others. It is therefore critically important to aim at understanding why criticism is not always welcomed and acted upon (Pitt and Norton, 2017). Such an inquiry is seemingly straightforward, but the answer is not always the case as many factors appear to have a role in shaping student’s perceptions of criticism and influencing their reactions toward it. In this regard, it’s assumed that perception of feedback is associated with engagement with feedback as both constructs are theoretically related (Lizzio and Wilson, 2008). This is precisely because the way how students perceive feedback mediates their approach to feedback uptake, and subsequently, directs their subsequent interactions with the received information (Carless and Boud, 2018; Han and Xu, 2021). In general, multiple factors are believed to constitute and frame perceptions of feedback such as the characteristics of the feedback message (Dowden et al., 2013), the impressions the student might have toward the feedback provider (e.g., teacher or peer) (Strijbos et al., 2021), the students’ feedback literacy (Winstone et al., 2017), and expectations of assessment results (Carless and Boud, 2018). Moreover, the student’s academic achievement, personality, and prior experiences with feedback also impact their conceptualizations of feedback (Winstone et al., 2019). Other factors relate to the context in which the feedback is used (e.g., the class atmosphere) (Ryan and Henderson, 2018).

Given the current focus, and to stimulate new perspectives for thinking about how perceptions impact behaviors with respect to criticism feedback in particular, we draw on Carvalho et al. (2014) argument that the student’s mental images of mistakes and failure are possibly a major contributor to variations in their interpretations and reactions toward criticism. Dweck (2007) has profoundly elaborated on this matter by articulating the notion of growth/fixed mindset which relates to the beliefs that students may have about their own learning and abilities. Dweck (2007) explained that our mindset shapes our thoughts in terms of the way how we learn, cope with setbacks, and progress, which leads to having different sets of actions. For instance, learners adopting a growth mindset accept challenges and tend to see mistakes as something from which they can bring about improvement, as well as consider failure as a signal that redirects them toward another path to success. They are more resilient and often do not hide their mistakes or get embarrassed by their deficiencies, instead, they positively reflect on those. Possessing such mental and psychological capabilities enable them to easily deal with criticism while being less oppositional or defensive. In support of these notions, Edgerly et al. (2018) explained that students with a growth mindset have the awareness that mistakes are powerful indicators of the obstacles that stand up in front of their progress, thus, it is a chance to problem-solve their weaknesses. Similarly, Orosz et al. (2023) concluded that growth mindset is positively and directly related to the student’s motivation to learn from criticism. With these ideas in mind, for students with a growth mindset, criticism becomes more like a “powerful corrective knowledge” or a “coach” from which they can always consult and learn, but not a judgment, a threat, or a destruction of self-concept.

Dweck (2007) further made a clear distinction between learners with a growth mindset and those with a fixed mindset. Comparatively, students with a fixed mindset see mistakes as setbacks but not as a turning point that helps them move forward in a direction that supposedly works better. They are fearful of facing difficult problems or challenging situations because they lack confidence in their potential and doubt their ability to deal with them. They usually aim for perfection, therefore, they avoid taking risks and making mistakes because they want to protect themselves (self-image) or to prove themselves in front of others like their teachers and peers (proving their worth) (Dweck, 2007), which shifts their thinking toward the “self” or “others” rather than “learning and improvement.” By implication, they become more focused on the evaluation results, as described by Carless (2006), are grade-oriented, rather than focusing on knowing why their answers went wrong, and so, may aggressively defend the marks lost.

Building on the discussion above, it is logical to speculate that the way how students deal with critical feedback could possibly be more a conceptual issue that appears to depend on their frame of mindset, which as a consequence, directs their behavioral actions.

2.4 Key provisions for improving criticism practices

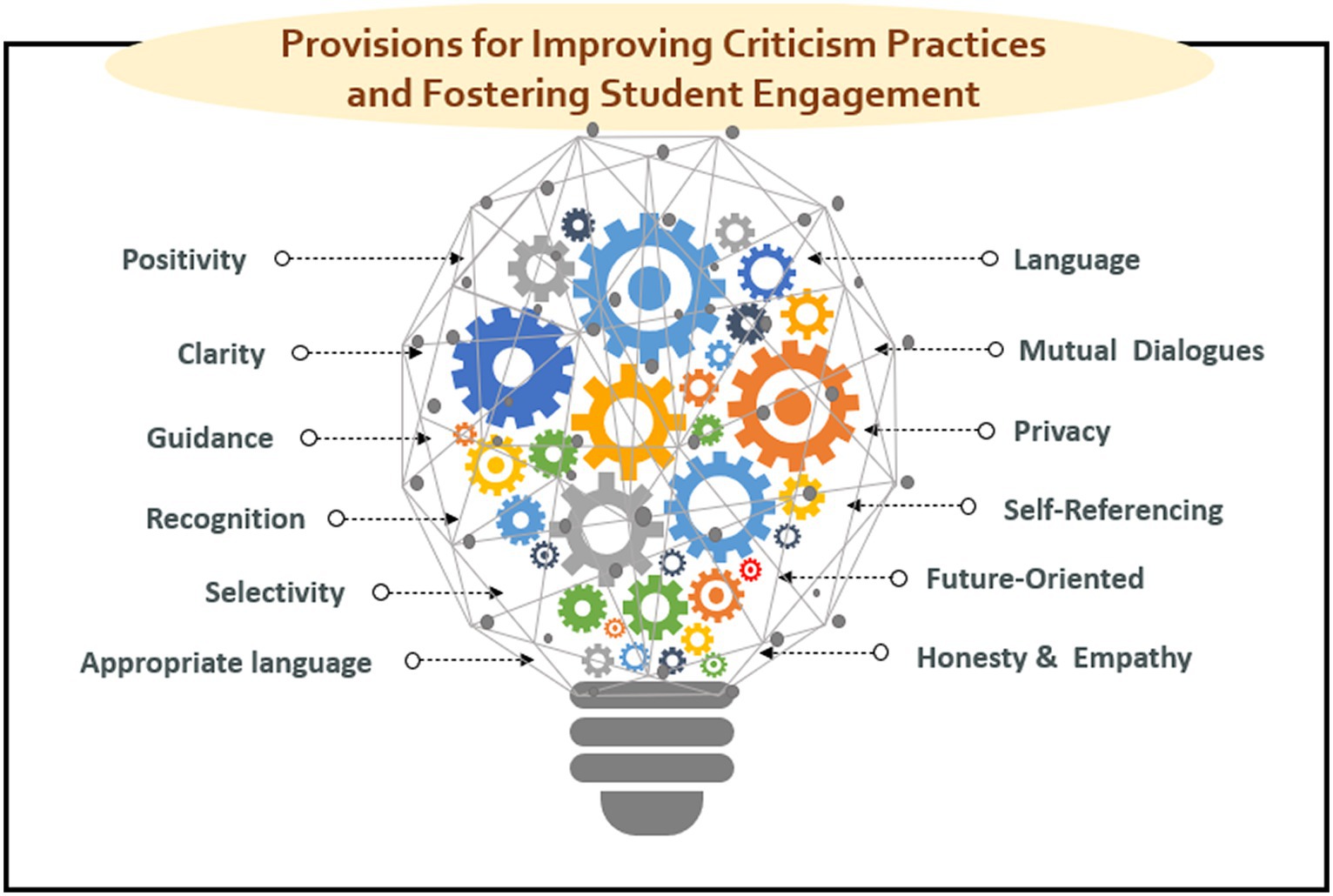

Serval strategic approaches and interventions have been stressed in the literature to improve criticism practices and foster deeper levels of acceptance and engagement with this type of feedback. These key provisions are illustrated in Figure 1 and discussed.

2.4.1 Connection to a meaningful purpose

learning from criticism needs to be by itself intrinsically rewarding. Teachers are recommended to make clear to students that acting on criticism information, eventually, contributes to their improvement (To, 2022). This creates a connection between criticism and a valuable purpose or larger goal; progress and success, which in turn, generates a worthwhile desire to learn from it. Only under this condition, students will have an inner motive to benefit from criticism, of their own accord, and for their own sake, hence, would consider the effort devoted to improvement worthwhile (Knight and Yorke, 2003).

2.4.2 Positivity in the criticism

Feedback that mixes equal parts of positive and negative comments, in other words, is cushioned by positivity, and is more welcomed by the students (Can and Walker, 2014; Elsayed and Cakir, 2023). This model of criticism is referred to as “sandwiched feedback” in which the negative judgmental information is placed between positive information (Weaver, 2006) in order to mentally redress the imbalance between effort and gains, therefore, easing criticism and softening its impact. Expectedly, criticism that starts with a pleasing compliment is most likely preferred because it empowers the students and conveys the message that they are still doing well (Gibbs and Simpson, 2005). Controversial views however exist over the sequence at which praise and criticism should be introduced, as well as over how much focus each should receive (Alt et al., 2023). Overall, having a mixture of and a balance between praise and criticism is encouraged.

2.4.3 Clarity

Criticism needs to be clear, transparent, relevant to the current assignment, and made against shared grading criteria (Nash and Winstone, 2017). It is considered instructive when it explicitly states reasons why the work falls short of the mark and what exactly the teacher wants the student to adjust or strengthen (To, 2022), or as expressed by one student “teachers should tell me what is missing” (Gamlem and Smith, 2013, p.10). This means that the response should not only say “this part is wrong,” but needs to provide precise and detailed information that enables students to know the criteria for improvement, so they can approach the right answers more profoundly with understanding (Dunworth and Sanchez, 2016).

2.4.4 Guidance

Research emphasizes that feedback is considered effective only when it includes guidance that clarifies the way forward toward learning progression and achievement (Gamlem and Smith, 2013). Therefore, the “how” element should be made explicit so criticism can become constructive and actionable. From a practical standpoint, teachers need to make sure that students understand what they are supposed to do next and know how to accomplish the tasks demanded in the feedback (Han and Xu, 2021). For instance, criticism may provide supportive justification to enable students to get a better sense of their thinking or may suggest complementary learning resources (such as a video or extra readings) to help them approach the right answers with better understanding (Winstone et al., 2016). It may guide students with detailed instructions or appropriate mechanisms to recheck the validity of the information they have (Carless et al., 2011). In other cases, criticism may offer alternative ways of thinking or unfamiliar solutions to help students develop new ideas and think outside the box (To, 2022). Teachers are also encouraged to guide students with appropriate approaches for articulating individual improvement plans and monitor them while pursuing the performance goals (Han and Xu, 2021). Such guidance and support make clear to students how they are expected to interact and engage with the feedback, which in turn, builds their commitment toward improvement (Knight and Yorke, 2003). This provision is critical when providing criticism because it pushes students to move beyond reading feedback to acting on it. It is therefore the mediating point between receiving and using assessment feedback (Sargeant et al., 2009). Under this condition, improvement feedback can influence the next steps of progress while being used as information for longitudinal development (Gamlem and Smith, 2013).

2.4.5 Recognizing and embracing effort

Given that the effort dimension in the feedback was found to be closely related to motivation (Pitt and Norton, 2017), educators need to consider acknowledging the effort devoted by the student to accomplish the task regardless of the final results or outcomes, which are usually judged based on standardized rubrics. Teachers are encouraged to scout for the good aspects of the student work and not just to honor the significant achievements. For instance, Carless (2006) noted a comment on a failed assignment in which the teacher praised the way how the student integrated his own experiences with the written text, which was the only thing done right! Supporting Weaver (2006) position, any slightest good comments no doubt make the student feel good. Indeed, tracing and pulling out the students’ strengths and successful attempts, salient or hidden, big or small, as expressed by Zhang and Zheng (2018), provides emotional support and demonstrates empathy and respect, all of which foster feelings of trust toward the assessor (Carless, 2019). In principle, putting a value on the student’s effort and showing interest in their work is stressed as a good practice in the feedback literature (Pitt and Norton, 2017) because it motivates the students and leads to personal satisfaction (Zhang and Zheng, 2018).

This provision is especially important to the low-performing students who may become depressed because of receiving criticism after putting in tremendous effort and who have literally tried their best. The literature therefore suggests several strategies to consider the follow-up effort that is taken by the student to further improve the work upon the provided feedback as part of the assessment marks. Given for example the second-draft submission or multistage assignments in which the student further attempts for enhancements after the first submission are also graded (Winstone et al., 2017; Han and Xu, 2021). Such a practice encourages students to take on more challenging tasks that might require extra effort. Otherwise, the assignment will be simply seen as a finished product with a determined score (Carless, 2019)—as one participant student expressed “What’s the point then of using the feedback if it will not change the mark” (Winstone et al., 2017, p. 2037).

2.4.6 Targeting the most critical shortcomings

Researchers have also grappled with the problem of overwhelming a struggling learner with a large number of critical comments instead of addressing the most significant shortcomings (Gibbs and Simpson, 2005). Criticism needs to be selective in order to direct the student’s effort more effectively toward what they need to focus on the most (Elsayed and Cakir, 2023). Focused elaboration in criticism allows students to become aware of their preconceptions and misconceptions while being engaged in critical reflection, self-error correction, and problem-solving, all of which facilitate long-term retention of the information (To, 2022).

2.4.7 Toning the language

Regardless of the good intentions, the tone of the criticism language and expressions should be expressed politely and respectfully (Gibbs and Simpson, 2005). This is very critical to make sure it places no threat to the student at the emotional level (Hattie and Timperley, 2007). When judging the student’s work, the extent to which the teacher might be using their power over the student needs to be taken into consideration (Alt et al., 2023). It is recommended therefore to deliver criticism in a formal way, yet with a friendly sense, not with anger or harsh words so it becomes more appreciated (Alt et al., 2023).

2.4.8 Opening channels for mutual dialogues

Engaging students in discussions over criticism feedback is necessary to facilitate the co-construction of knowledge (Carless, 2022). This is especially important because learning is a social activity not an individual process (Osborne, 2014). As such, recent feedback literature underpins the importance of stimulating teacher-student dialogues (Carless and Boud, 2018; Vattøy et al., 2020; Carless, 2022). Generally, post-feedback discussions are beneficial as they open new horizons of thinking for both the teacher and the student, as well as help reconcile any conflict or disagreement (McLean et al., 2015). This, in turn, restructures thinking and shapes ideas while generating more deeper understanding (Boud and Soler, 2016). For example, it provides space to negotiate the made judgment on the student’s work and can help resolve any misunderstanding. Furthermore, such communicative interactions allow students to ask for further clarification or to verify any doubts regarding feedback. Most importantly, they strengthen the relationship between the teacher and the student (Carless, 2022). Accordingly, when mutual dialogues between the student and the teacher are available and welcomed, criticism becomes open to discussion but not a final judgment (McLean et al., 2015). It is worth noting here that the online learning platforms that are increasingly used to perform online assessment activities incorporate features that help activate this practice. For instance, they allow the student to reply to the teacher’s feedback; leading to more direct dialogic feedback interaction.

2.4.9 Securing privacy

The importance of being careful when criticism is shared with a student publicly in front of the other classmates is also stressed. The assumption that the teacher has the right to disclose the student’s ideas to others in the classroom is questionable (Pitt et al., 2020) especially if it exposes the student to any potential harm. Expectedly, students will not feel safe sharing their gaps in learning or incorrect thinking (Han and Xu, 2021). However, Pollari (2017) believes this could be acceptable when the feedback information is shared with the class for summative purposes without referring to the individual student so he or she is not demoralized. This ensures greater respect for the privacy and the self-worth of the student, and therefore, establishes a psychologically healthy environment in the feedback practice (To, 2022).

2.4.10 Self-referencing

Similar attention needs to be paid when using criticism as a base for comparison. According to McLean et al. (2015), when feedback is “norm-referenced,” meaning that it compares one’s performance to another’s performance, it makes the student feel inferior and discouraged. Such a practice may convey an embedded message that the prime purpose is competition, not personal improvement, which could be counterproductive in helping students to achieve and progress (Gibbs and Simpson, 2005). Conversely, when feedback is “self-referenced,” it increases expectations about own performance since it compares one’s performance to other measures of one’s ability, such as against the students’ individual improvement plan or learning goals (McLean et al., 2015).

2.4.11 Future-oriented

Besides using criticism to highlight the current performance gap that concerns how things are going at the moment, it should also feed-forward (Sadler, 2010). The concept of “feed-forward,” or so-called, future-oriented feedback (Pollari, 2017) entails feedback that is helpful or applicable to other types of tasks or future work. Smart criticism is both specific (adapted for a particular content or assignment), as well as general (addresses general guidelines or standard rules that apply to other settings); signaling the two-fold impact of feedback within and outside its current use (Elsayed and Cakir, 2023). For instance, criticism needs to clarify the error in the students’ thinking not only to pinpoint the wrong answers so the student can adopt more valid ways of thinking in their next attempts (Boud and Molloy, 2013). Neglecting the long-term dimension of criticism, which is usually undermined by formative assessment practices (To, 2022), weakens the formative value of criticism as an instrumental means to generate further progress. Students are generally not aware of the future use of feedback information (Ali et al., 2018).

2.4.12 Honesty and empathy

Feedback needs to be honest and credible based on objective criteria (Gamlem and Smith, 2013). However, while the teacher attempts to provide the truest expressions in their criticism, they need to reflect a sense of being understanding, and empathetic (Elsayed and Cakir, 2023). For instance, when giving criticism, students can be encouraged to share their perspectives and concerns, as well as to express their feelings and needs, and the teacher shall listen attentively to these responses to show care for their point of view (Orosz et al., 2023). In this manner, criticism will not appear as a sort of personal attack when a collaborative and supportive tone is used not blaming (Orosz et al., 2023).

3 Conclusion

In sum, the current conceptual analysis contributes to the discussion about the substantial role that criticism plays in advancing student’s learning and progress as part of formative assessment processes in the teaching and learning context. It draws attention to variations in student’s interpretations and reactions toward criticism. It also highlights areas that educators could strengthen to improve criticism practices by identifying key provisions that are necessary for critical feedback to be constructed, presented, interpreted, and utilized efficiently. These best practices are stressed in literature and are highly considered by the students. They help make criticism become less of a command and more of a constructive advice that can be easily accepted, allowing the beauty of criticism to overcome its downsides, which subsequently, help trigger learner’s positive reactions and foster their productive engagement with criticism.

4 Limitation and implication

There will be always much space to generate new understanding that can enrich the literature on criticism feedback practices. Although the literature discussed various factors that are believed to impact students’ perceptions and interactions toward criticism, these were not taken further here because it is secondary to the main theme. Nevertheless, the article discussed a set of provisions and functional tactics that provide useful insights and ideas on how to support student engagement with criticism. The provisions help create a community of practice where objective, informative, transparent, and engaging criticism can be given, respected, negotiated, and benefited from. Although the discussed provisions targeted criticism in particular, they can be applied to different feedback situations, such as oral, written, or online.

Overall, Educators from different parts of the world can potentially benefit from these provisions of criticism across different learning subjects and stages since they serve shared purposes. Importantly, the provisions can be promoted via training endeavors. This is needed for both teachers and students as the current argument showed how the establishment of effective criticism practices is not a simple goal to facilitate by the teacher nor an easy task to fulfill by the student (Winstone et al., 2019). It is not solely the responsibility of the teacher or the student but rather a shared responsibility.

To do so, and as part of teacher education programs or teachers’ professional development activities, teachers can be guided on how to design quality criticism while building on these provisions. This can be accompanied by strategies on how to contain students’ emotional sensitivity to criticism (Carless and Winstone, 2023). Similarly, applications of these provisions that relate to the student’s role can be incorporated into the study skills program in schools. For instance, students can be guided on how to envision the true value of criticism as part of their improvement, understand what it is for, how it can be best utilized, and how to respond to it (Winstone et al., 2017). Taken collectively, these steps are of utmost importance given that the implementation of provisions for effective criticism practices is still lacking in many classrooms.

Author contributions

LR: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. SH: Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adams, A.-M., Wilson, H., Money, J., Palmer-Conn, S., and Fearn, J. (2020). Student engagement with feedback and attainment: the role of academic self-efficacy. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 45, 317–329. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2019.1640184

Ali, N., Ahmed, L., and Rose, S. (2018). Identifying predictors of students’ perception of and engagement with assessment feedback. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 19, 239–251. doi: 10.1177/1469787417735609

Ali, N., Rose, S., and Ahmed, L. (2015). Psychology students’ perception of and engagement with feedback as a function of year of study. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 40, 574–586. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2014.936355

Alt, D., Naamati-Schneider, L., and Weishut, D. J. (2023). Competency-based learning and formative assessment feedback as precursors of college students’ soft skills acquisition. Stud. High. Educ. 48, 1901–1917. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2023.2217203

Bennett, R. E. (2011). Formative assessment: a critical review. Assessment in education: principles, policy & practice, 18, 5–25. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2010.513678

Black, P., and Wiliam, D. (2018). Classroom assessment and pedagogy. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 25, 551–575. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2018.1441807

Boud, D., and Molloy, E. (2013). Rethinking models of feedback for learning: the challenge of design. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 38, 698–712. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2012.691462

Boud, D., and Soler, R. (2016). Sustainable assessment revisited. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 41, 400–413. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2015.1018133

Bruno, I., and Santos, L. (2010). Written comments as a form of feedback. Stud. Educ. Eval. 36, 111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2010.12.001

Can, G., and Walker, A. (2014). Social science doctoral students’ needs and preferences for written feedback. High. Educ. 68, 303–318. doi: 10.1007/s10734-014-9713-5

Carless, D. (2006). Differing perceptions in the feedback process. Stud. High. Educ. 31, 219–233. doi: 10.1080/03075070600572132

Carless, D. (2019). Feedback loops and the longer-term: towards feedback spirals. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 44, 705–714. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2018.1531108

Carless, D. (2022). From teacher transmission of information to student feedback literacy: activating the learner role in feedback processes. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 23, 143–153. doi: 10.1177/1469787420945845

Carless, D., and Boud, D. (2018). The development of student feedback literacy: enabling uptake of feedback. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 43, 1315–1325. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354

Carless, D., Salter, D., Yang, M., and Lam, J. (2011). Developing sustainable feedback practices. Stud. High. Educ. 36, 395–407. doi: 10.1080/03075071003642449

Carless, D., and Winstone, N. (2023). Teacher feedback literacy and its interplay with student feedback literacy. Teach. High. Educ. 28, 150–163. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2020.1782372

Carvalho, C., Santos, J., Conboy, J., and Martins, D. (2014). Teachers’ feedback: exploring differences in students’ perceptions. Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 159, 169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.12.351

Cengiz, E., and Ayvaci, H. Ş. (2017). Analysing the feedback that secondary school science teachers provide for student errors that show up in their lessons. J. Turkish Sci. Educ. 14, 109–124. doi: 10.12973/tused.10207a

Dawson, P., Henderson, M., Mahoney, P., Phillips, M., Ryan, T., Boud, D., et al. (2019). What makes for effective feedback: staff and student perspectives. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 44, 25–36. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2018.1467877

Dowden, T., Pittaway, S., Yost, H., and McCarthy, R. (2013). Students’ perceptions of written feedback in teacher education: ideally feedback is a continuing two-way communication that encourages progress. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 38, 349–362. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2011.632676

Dunworth, K., and Sanchez, H. S. (2016). Perceptions of quality in staff-student written feedback in higher education: a case study. Teach. High. Educ. 21, 576–589. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2016.1160219

Edgerly, H., Wilcox, J., and Easter, J. (2018). Creating a positive feedback culture: eight practical principles to improve students’ learning. Sci. Scope 41, 43–49. doi: 10.2505/4/ss18_041_05_43

Elsayed, S., and Cakir, D. (2023). Implementation of assessment and feedback in higher education. Acta Pedagogia Asiana 2, 34–42. doi: 10.53623/apga.v2i1.170

Esterhazy, R., and Damşa, C. (2019). Unpacking the feedback process: an analysis of undergraduate students’ interactional meaning-making of feedback comments. Stud. High. Educ. 44, 260–274. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2017.1359249

Furtak, E. M. (2009). Formative assessment for secondary science teachers. United States: Corwin Press.

Gamlem, S. M., and Smith, K. (2013). Student perceptions of classroom feedback. Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 20, 150–169. doi: 10.1080/0969594X.2012.749212

Gibbs, G., and Simpson, C. (2005). Conditions under which assessment supports students’ learning. Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, 1, 3–31. Available at: https://eprints.glos.ac.uk/id/eprint/3609

Han, Y., and Xu, Y. (2021). Student feedback literacy and engagement with feedback: a case study of Chinese undergraduate students. Teach. High. Educ. 26, 181–196. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2019.1648410

Harrison, C. (2015). Assessment for learning in science classrooms. J. Res. STEM Educ. 1, 78–86. doi: 10.51355/jstem.2015.12

Hattie, J., and Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 77, 81–112. doi: 10.3102/003465430298487

Knight, P., and Yorke, M. (2003). Assessment, Learning and Employability. McGraw-Hill Education. Available at: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uaeu-ebooks/detail.action?docID=290354

Lizzio, A., and Wilson, K. (2008). Feedback on assessment: students’ perceptions of quality and effectiveness. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 33, 263–275. doi: 10.1080/02602930701292548

Mahfoodh, O. H. A. (2017). “I feel disappointed”: EFL university students’ emotional responses towards teacher written feedback. Assess. Writ. 31, 53–72. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2016.07.001

Man, D., Chau, M. H., and Kong, B. (2021). Promoting student engagement with teacher feedback through rebuttal writing. Educ. Psychol. 41, 883–901. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2020.1746238

McLean, A. J., Bond, C. H., and Nicholson, H. D. (2015). An anatomy of feedback: a phenomenographic investigation of undergraduate students’ conceptions of feedback. Stud. High. Educ. 40, 921–932. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2013.855718

Molloy, E., Boud, D., and Henderson, M. (2020). Developing a learning-centred framework for feedback literacy. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 45, 527–540. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2019.1667955

Mutch, A. (2003). Exploring the practice of feedback to students. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 4, 24–38. doi: 10.1177/1469787403004001003

Nash, R. A., and Winstone, N. E. (2017). Responsibility-sharing in the giving and receiving of assessment feedback. Front. Psychol. 8:2529. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01519

Orosz, G., Evans, K. M., Török, L., Bőthe, B., Tóth-Király, I., Sik, K., et al. (2023). The differential role of growth mindset and trait mindfulness in the motivation of learning from criticism. Mindfulness 14, 868–879. doi: 10.1007/s12671-023-02117-4

Osborne, J. (2014). “Scientific practices and inquiry in the science classroom,” in Handbook of Research on Science Education, Eds. Abell, S. K., and Lederman, N. G., 593–613. Routledge.

Pitt, E., Bearman, M., and Esterhazy, R. (2020). The conundrum of low achievement and feedback for learning. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 45, 239–250. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2019.1630363

Pitt, E., and Norton, L. (2017). ‘Now that’s the feedback I want!’ Students’ reactions to feedback on graded work and what they do with it. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 42, 499–516. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2016.1142500

Pollari, P. (2017). To feed back or to feed forward? Students’ experiences of and responses to feedback in a Finnish EFL classroom. Apples J. Appl. Lang. Stud. 11, 11–33. doi: 10.17011/apples/urn.201708073429

Price, M., Handley, K., Millar, J., and O’Donovan, B. (2010). Feedback: all that effort, but what is the effect? Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 35, 277–289. doi: 10.1080/02602930903541007

Rabbani, L. M., AlQuwaitaei, R. S., Alarabi, K. S., and Alsalhi, N. R. (2023). Feedback revisited: definitional, structural, and functional issues. J. Stat. Appl. Probabil. 12, 1039–1044. doi: 10.18576/jsap/120313

Ryan, T., and Henderson, M. (2018). Feeling feedback: students’ emotional responses to educator feedback. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 43, 880–892. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2017.1416456

Sadler, D. R. (2010). “Beyond feedback: developing student capability in complex appraisal” in Approaches to assessment that enhance learning in higher education, Eds. S. Hatzipanagos and R. Rochon, (United Kingdom: Routledge), vol. 35 535–550.

Sargeant, J. M., Mann, K. V., van der Vleuten, C. P., and Metsemakers, J. F. (2009). Reflection: a link between receiving and using assessment feedback. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 14, 399–410. doi: 10.1007/s10459-008-9124-4

Strijbos, J.-W., Pat-El, R., and Narciss, S. (2021). Structural validity and invariance of the feedback perceptions questionnaire. Stud. Educ. Eval. 68:100980. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2021.100980

To, J. (2022). Using learner-centred feedback design to promote students’ engagement with feedback. Higher Educ. Res. Dev. 41, 1309–1324. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2021.1882403

Vattøy, K.-D., Gamlem, S. M., and Rogne, W. M. (2020). Examining students’ feedback engagement and assessment experiences: a mixed study. Stud. High. Educ. 46, 2325–2337. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2020.1723523

Walker, M. (2009). An investigation into written comments on assignments: do students find them usable? Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 34, 67–78. doi: 10.1080/02602930801895752

Weaver, M. R. (2006). Do students value feedback? Student perceptions of tutors’ written responses. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 31, 379–394. doi: 10.1080/02602930500353061

Winstone, N., Bourne, J., Medland, E., Niculescu, I., and Rees, R. (2021). “Check the grade, log out”: students’ engagement with feedback in learning management systems. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 46, 631–643. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2020.1787331

Winstone, N. E., Mathlin, G., and Nash, R. A. (2019). Building feedback literacy: students’ perceptions of the developing engagement with feedback toolkit. Front. Educ. 4:39. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00039

Winstone, N. E., Nash, R. A., Rowntree, J., and Menezes, R. (2016). What do students want most from written feedback information? Distinguishing necessities from luxuries using a budgeting methodology. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 41, 1237–1253. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2015.1075956

Winstone, N. E., Nash, R. A., Rowntree, J., and Parker, M. (2017). ‘It’d be useful, but I wouldn’t use it’: barriers to university students’ feedback seeking and recipience. Stud. High. Educ. 42, 2026–2041. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2015.1130032

Keywords: formative assessment, feedback, criticism, feedback best practices, engagement with feedback

Citation: Rabbani LM and Husain SH (2024) Fostering student engagement with criticism feedback: importance, contrasting perspectives and key provisions. Front. Educ. 9:1344997. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1344997

Edited by:

Siv Gamlem, Volda University College, NorwayReviewed by:

Meerita Segaran, Østfold University College, NorwayPernille Fiskerstrand, Volda University College, Norway

Copyright © 2024 Rabbani and Husain. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lutfieh M. Rabbani, 980227160@uaeu.ac.ae

†ORCID: Lutfieh M. Rabbani, http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2170-1554

Salwa Habib Husain, http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5563-4188

Lutfieh M. Rabbani

Lutfieh M. Rabbani