- Faculty of Education, Department of Pedagogy, Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences, Lillehammer, Norway

The number of forcibly displaced people, including refugees, has been increasing exponentially over the last few decades. Refugees settled in Western destination countries face several challenges in successfully accessing and participating in higher education and in becoming knowledge producers. This is in sharp contrast to uncritical assumptions that refugees settled in these countries are better off in terms of pursing higher education. To shed more light on this issue, I aim to address the research question ‘How does the integration process in a Western destination country contribute to the exclusion of refugees from knowledge production?’ The article uses an education pipeline analogy and human agency theory as the theoretical framework. I conduct narrative interviews with six refugees who planned to pursue higher education but could not realize their plans in Norway. The findings indicate that the refugee education pipeline is broken and stuffed with various restrictive factors that weaken the refugees’ agency to make informed decisions. These factors included a long waiting time for settlement, withholding relevant information about higher education, demotivating and misplaced advice about higher education and language training programmes for non-academic purposes. The article ends with a conclusion and several implications.

Introduction

The global number of forcibly displaced people reached 108.4 million, including 35.3 million refugees, by the end of 2022 (UNHCR, 2023). Refugees live in different places under varying circumstances. Some are in protracted situations with few or no civic rights and opportunities for self-development through higher education (Ramsay and Baker, 2019). Other refugees live in relatively stable and high-income contexts. While it can be assumed that refugees in the latter context have better possibilities in many areas, including higher education, their trajectories to access, participate in and succeed in higher education are not necessarily straightforward (Abamosa, 2023a). In fact, refugees—particularly those from non-Western countries—living in many Western destination countries are considered as ‘disposables’ and are often at the bottom of the social hierarchy (Vlachou and Tlostanova, 2023, p. 204). Moreover, they are perceived as security risks (Skodo, 2020), a burden on welfare benefits, such as unemployment compensation (Friberg and Midtbøen, 2018), opportunists and bogus claimants (Kmak, 2015; Haw, 2020).

Therefore, it is not surprising that immigration policies in many Western destination countries have become stricter in recent years with many restrictions on the rights and privileges of asylum seekers and refugees (FitzGerald, 2019; Parveen, 2020; Crawley, 2021; Murry and Gray, 2023). One of the (direct or indirect) effects of such restrictions and ill-informed perceptions about refugees is to literally push refugees to ‘low-wage, unskilled’ sectors on the pretext of helping them become economically self-sufficient (Koyama, 2015, p. 610; Darrow, 2015; Abamosa, 2023b). In addition, refugees face multi-layered challenges in their trajectories to higher education. Lack of sufficient academic language (training), financial burdens, difficulty getting their pre-arrival qualifications recognized, complex academic systems, discrimination and racism, lack of reliable information and traumatic experiences are some of the challenges (Achiume, 2014; Détourbe and Goastellec, 2018; Lambrechts, 2020; Sobczak-Szelc et al., 2021; Kondacki et al., 2023).

All these things make it difficult for many refugees to become knowledge producers in many destination countries (Arar, 2021; Olsson et al., 2023). This in turn reproduces and sustains the knowledge production systems characterized by epistemological hegemony and asymmetrical power relationships by further excluding refugees, “silencing unwanted voices and shutting out perspectives that expose the injustice” (Davies et al., 2023, p. 169).

Even though the literature on refugee higher education has been increasing, particularly since 2016, more research is needed to better understand the ‘structural and institutional issues that create obstacles’ for refugees in their journeys to become knowledge producers (Berg, 2023, p. 2). Such understanding is vital, particularly in Western countries such as Norway that are otherwise known for their high human development index (United Nations Development Programme, 2020) and that are perceived to be exceptional ‘in terms of equality and egalitarianism’ (Dankertsen and Lo, 2023, p. 19). In practice, however, some groups of people, including refugees, may ‘come face-to-face with national systems shaped by inequalities foreign to them that determine their access to resources as they rebuild their lives and imagine their future’ (Gowayed, 2022, p. 3). This article explores the integration experiences of refugees to cast light on the structures and practices that exclude them from higher education in Norway. To this end, I aim to address the research question, ‘How does the integration processes in a Western destination country contribute to the exclusion of refugees from knowledge production?’

Refugees and the settlement process in Norway

The Norwegian Immigration Act (2008) defines a refugee as a foreigner who, in the realm or at the border of Norway, applies for and is granted protection due to:

a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of ethnicity, origin, skin colour, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or for reasons of political opinion, and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself or herself of the protection of his or her country of origin (§28a).

Foreigners may also be recognized as a refugee in Norway without falling within the scope of the above definition if they face a real risk of being subjected to the death penalty, torture or other inhumane or degrading treatment or punishment upon return to their country of origin (The Norwegian Immigration Act, 2008, §28 b). Norway resettles a specific number of refugees decided by the Storting (the Norwegian Parliament) annually in cooperation with the UNHCR. These refugees are often referred to as ‘quota refugees’ (Adserà et al., 2022). Family members living with all the above-mentioned groups fall in the refugee category.

Compared with many European countries, Norway was ‘a slow starter when it came to the new immigration’, seeing the arrival of significant numbers of refugees later than other countries (Brochmann and Hagelund, 2012, p. 162, emphasis in original). Even though there were refugees in Norway before the1960s (Østby, 2013), the number and diversity of refugees increased dramatically after the 1970s (Cooper, 2005). Refugees from many countries, such as Afghanistan, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Chile, Eritrea, Iran, Iraq, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Syria, Ukraine, Vietnam and Yugoslavia have arrived in Norway ever since (Cooper, 2005; Østby, 2017; Bjånesøy and Bye, 2023). As of January 1, 2023, there were 280,000 people with a refugee background in Norway, making up 5.1% of the country’s population (Statistics Norway, 2020).

Settlement processes for refugees vary based on the types of refugees. Asylum seekers generally stay at asylum seekers reception centres or sometimes with friends or relatives until the Norwegian Immigration Directorate (UDI) assesses their requests for protection and/or they are settled in municipalities. The reception centres are often located in the countryside or other peripheral areas to ensure the geographical and social isolation of asylum seekers and refugees (Willmann-Robleda, 2020). Following a positive decision on their case and before moving to a municipality for settlement, refugees are invited to a ‘settlement interview’ at the reception centres. The purpose of the interview is ostensibly to outline each refugee’s future goals, particularly regarding employment and education and to find a suitable municipality for settlement (Strøm et al., 2020, p. 9). The waiting time for settlement in municipalities also varies depending on the refugees’ situations. In some cases, refugees with significant health issues or other conditions (such as having a disabled child) may wait for many years to be settled in municipalities. These refugees are often referred to in the media as ‘refugees no municipality/one wants (to settle)’ (Malmo, 2020; Olsen, 2022). However, it is not uncommon for refugees without any conditions to wait ‘for prolonged periods’ at reception centres (Willmann-Robleda, 2020). Quota refugees ‘generally do not wait in reception centres’ because they are directly settled in municipalities upon arrival in Norway (OECD, 2022, p. 2). Adult asylum seekers and refugees—with some exceptions—residing in reception centres must attend 200 h of Norwegian language instruction and civic education (IMDi, 2023).

The Directorate of Integration and Diversity coordinates the settlement of refugees in the municipalities. Once settled there, refugees aged 18–55 years have the right and duty to participate in a basic full-time training programme or introduction programme. The programme came into effect nationally in 2004 with the aim of ‘enabling participants to become self-sufficient members of Norwegian society’ (Hagelund, 2005, p. 670). The content and duration of the programme have changed over time. Currently (in 2023/2024), refugees can attend the programme for a minimum of three months and a maximum of 4 years based on their educational background, goals in Norway, age and other factors. Refugees get basic training in the Norwegian language, civic studies and internship (or even apprenticeship) as the main components of the introduction programme. Refugees who participate in the programme receive a monthly allowance, and any unjustified absenteeism can result in a deduction from the allowance. Municipalities are responsible for providing the introduction programme to all entitled refugees (Steien and Monsen, 2023). Refugees can opt out of settling in state-assigned municipalities, but they may not be entitled to the monthly introduction programme allowances in such cases (IMDi, 2021).

Even though there are variations among different groups of refugees, in general terms, refugees in Norway fare worse than other immigrant groups in many areas, including labor market participation and (higher) education attainment (Steinkellner, 2017; Djuve and Kavli, 2019; Kobberstad, 2023). The overall integration policy encourages refugees to be economically self-sufficient as soon as possible rather than, for example, pursing higher education (Abamosa et al., 2020). Moreover, the state advises municipalities in Norway to use refugees to fill vacant positions not wanted by others (Justis-og beredskapsdepartementet, 2016, p. 58). It is therefore not surprising that refugees are overrepresented in low-skill, low-wage, labor-intensive and often temporary positions (Friberg and Midtbøen, 2018). Strikingly, there is less emphasis on refugee higher education in Norway (Abamosa, 2023b) despite the documented positive impact of (higher) education received in Norway on refugees’ upward social mobility (Olsen, 2019).

There are many state and non-state actors directly or indirectly involved in the refugee integration processes. Some of these include the UDI, the Norwegian Immigration Appeals Board, Norwegian Organisation for Asylum Seekers, IMDi, asylum seekers reception centres, health centres, adult education centres, refugee centres in municipalities, the Norwegian Labor and Welfare Administration, the Norwegian Red Cross, the Norwegian Agency for Quality Assurance in Education, Lånekassen (Norwegian State Educational Loan Fund), higher education institutions and schools (Askim and Steen, 2020; Abamosa, 2023b). This indicates that refugees may come face to face with a number of street-level bureaucrats, that is, ‘public service workers who interact directly with citizens in the course of their jobs, and who have substantial discretion in the execution of their work’ (Lipsky, 2010, p. 3).

Literature review

In contemporary Western society, which is characterized in part by significant cross-border movement of ideas and people (immigration), overly racist criteria to exclude refugees from higher education is generally not acceptable. As a study from Canada indicates, it is rather the ‘subtler forms of racialized exclusion [that are] integrated into admission policies for refugee claimants” that hinder refugees’ advancement to higher education (Villegas and Aberman, 2019, p. 75). For instance, refugees are streamed into non-academic fields and pushed out of schools over time. This corroborates an earlier study from New Zealand (O’Rourke, 2011), which states that some policies ‘constrict pathways to and through university study for students from refugee backgrounds’ (O’Rourke, 2011, p. 26). In the same vein, Lenette et al. (2019) indicate that the Australian government intentionally proposes policies to close pathways to higher education for refugees by making it difficult for them to attain the necessary proficiency in English. A mixed-methods study from Australia has found that refugees, particularly those from Africa, are quite underrepresented in higher education for various reasons, some of which are structural in nature (Molla, 2021). For example, there is a lack of recognition of refugees from certain areas as more disadvantaged; recognising this could enable policymakers and other actors to devise relevant policies to alleviate challenges faced by such refugees. Naidoo et al. (2018) convincingly argue that avoiding defining refugees as belonging to distinct equity groups based on their particular experiences is not necessarily an act of social justice. Quite the opposite, it may be ‘a mechanism’ by which dominant groups oppress refugees (Naidoo et al., 2018, p. 105).

Research from Austria shows that the government has put in place policies to deter the integration of refugees into host society (Verwiebe et al., 2019). These restrictive policies negatively influence initiatives aimed at refugee inclusion in higher education in Austria (Bacher et al., 2020). Molla (2021) notes that there is reluctance on the part of the authorities in some destination countries, such as Australia, to fight ‘structural unfreedoms such as racial vilification of Black Africans in the public sphere’ (p. 345, italics in original). Molla (2021) and other researchers (e.g., Stewart and Mulvey, 2014) argue that such negative experiences may impede the educational attainment of refugee youth by exposing them to stress and feelings of powerlessness.

For example, at the individual level, one refugee who participated in an ethnographic study in Sweden narrated,

My dream is to study at the university. But when you go to [the caseworkers], they do not listen to your ambitions and dreams. They make you believe that you can tell them what you want. In the end they will write in their plans what they want … (Amir quoted in an ethnographic study by Gren, 2020, p. 161, italics and brackets in original).

This statement from an apparently frustrated refugee who wanted to pursue higher education and perhaps become a knowledge producer indicates the introductory programme he was participating in did not help refugees ‘to pursue their dream of upward social mobility through reassuming or starting their higher education’ (Gren, 2020, p. 165). Based on an ethnographic study, Koyama (2015) similarly finds that integration programmes for refugees in the US perpetuate the exclusion of refugees from (higher) education by placing them in entry-level and low-wage positions because they ‘have the potential not only to delay their further learning of English, but also to diminish their long-term social mobility’ (p. 618). Another study from the US (McBrien, 2019) indicates that language teachers do not provide the necessary language training to refugees, partly because many teachers are not certified to teach English to speakers of other languages. This finding closely related to the findings of an autobiographical study from Norway (Abamosa, 2024), indicating that refugees are enrolled in mediocre language courses designed for unskilled positions rather than for academic purpose.

An analysis of various legal and policy documents, including data for 71,781 people who participated in the introduction programme over a 20-year period in Norway, shows that even though adult refugees have a formal right to education, a number of challenges prevented the implementation of that right (Aspøy et al., 2023). For example, refugees who wanted to complete upper secondary education during the introduction programme could not because the time allotted for the introduction programme expired before they could finish school. Moreover, the poor design of the training programmes prevented refugees from advancing in education. However, other scholars from different contexts (Austria, Germany, the US and Norway) indicate that some refugees and other stigmatized groups actively challenge negative behaviors and oppressive systems. In other words, they are not just passive recipients of stressors (McBrien, 2005; Mucchi-Faina, 2009; Heinemann, 2017; Abamosa, 2024).

The studies discussed above indicate the importance of a broader understanding of the sophisticated, often hidden but intentional mechanisms of excluding refugees from higher education (on the pretext of labor market participation) in high-income countries such as Norway. However, there is a dearth of literature on the experiences of refugees to become knowledge producers by accessing and succeeding in higher education in Norway. This article contributes to knowledge on this topic by exploring the experiences of refugees in Norway.

Theoretical framework

In this article, I employ a theoretical framework consisting of two elements: agency theory and an education pipeline analogy relating to the context of the refugee integration in a high-income Western country. This enables me to explore the experiences of refugees (agency) in given social structures (of which the education pipeline is one) in ways that relate to the research question. Agency is an elusive term that has various definitions and categories (Ahern, 2001). Here, the focus is delimited to human or individual agency.

Parsell et al. (2017) define human agency as ‘an individual’s capacity to determine and make meaning from their environment through purposive consciousness and reflective and creative action’ (p. 239). Similarly, Van Nijnatten (2010) defines individual agency as ‘the power of individuals to manage their lives, to maintain their authenticity and autonomously make a living’ (p. 7). According to these definitions, individuals—as an agent of their life—must be able to intentionally influence their ‘function and life circumstances’ (Bandura, 2006, p. 164). Based on all this, in this article, human or individual agency may be understood as the unhindered possibilities and power individual refugees have to make informed decisions regarding access to higher education during the early integration process in Norway to become knowledge producers in the future (Elder, 1994; Bandura, 2006; van Nijnatten, 2010; Parsell et al., 2017).

It must be borne in mind that many factors mediate individuals’ agency in different ways (Ahern, 2001). Therefore, people may not be successful in achieving what they want on their own. In Bandura’s (2006) words, ‘people do not have direct control over [some] conditions that affect their lives’ (p. 165). An individual’s agency can be thin or thick over time and space based on the type of (power) structures, contexts and relationships that constrain or expand her individual’s range of feasible choices (Klocker, 2007). According to Klocker (2007), thin agency refers to ‘decisions and everyday actions that are carried out within highly restrictive contexts, characterized by few viable alternatives’ (p. 85). For example, an individual from a marginalized ethnic group, a marginalized gender, a peripheral geographical area or a lower socio-economic background or intersection of these can, against all odds, actively negotiate ‘the expectations and power relations that surround’ her and make decisions to improve her own life and even the lives her family members (Klocker, 2007, p. 85). In this case, the marginalized ethnic group and gender, the peripherality of the geographical location, the lower socio-economic status and/or intersectionality of these serve to thin out the agency of the individual. Robson et al. (2007) argue that the concept of thin agency is useful to overcome challenges related to the portrayals of certain groups of people as victims. Thick agency refers to ‘having the latitude to act within a broad range of options’ (Klocker, 2007, p. 85). The agency refugees exercise can be seen in relation to the education pipeline.

The analogy of the education pipeline is relevant in this context because refugees experience ‘controlled’ immigration processes, and by extension a controlled education system, just like a pipeline. Watson (2023) defines a pipeline as ‘a meso organizational form of procedural standardization that facilitate controlled, predictable, and efficient institutional practice’ (p. 705). For example, in a higher education context, higher education institutions in some countries can establish pipelines with certain upper secondary schools to fill annual admission spots. Dryden-Peterson and Giles (2012) define the higher education pipeline as ‘educational continuum […] beginning with early childhood education and continuing through primary and secondary education’ (p. 4). Drawing on this, the refugee education pipeline may be understood in this article as the educational continuum—including language courses—refugees must travel along as a part of their integration in Norway. As mentioned above, refugees in Norway must participate in some obligatory activities that are pre-designed in the form of a pipeline. Not participating in these activities may result in negative consequences, such as the inability to get a permanent residence permit and the withdrawal of monetary allowances. Thus, refugees are necessarily put in a pipeline-like integration process. Here, I concur with Nayir and Taner (2015) in that the challenge is not about getting refugees into the pipeline per se, but ‘rather it is about giving them the “support needed to reach their full potential,” once they get there’ (p. 19).

Researchers from various fields have used the education pipeline analogy. For instance, Young (2005) used the concept of a leaky science education pipeline to analyze the underrepresentation of African Americans and Hispanics in science and technology occupations. Wotipka et al. (2018) used a higher education pipeline perspective to investigate the participation rate of women in faculty positions in higher education institutions globally. Others used the analogy to explore the participation of students in science and engineering in the Netherlands (van den Hurk et al., 2019), the academic pipeline of marginalized groups, including refugees (Cooper, 2011) and the refugee reception pipeline in Botswana (Parsons, 2008). The first descriptive analysis of the literature in this regard reveals an unbalanced concentration of literature in the US within the fields of science, engineering, technology and mathematics. Therefore, much of the previous literature differs from the current framework, which relates to refugee higher education.

Materials and methods

In this article, I employed a narrative inquiry, which is best suited for exploring the life experiences of a ‘small number of individuals’ (Creswell, 2013, p. 74). Narrative inquiry suits the purpose of this article because it is an appropriate method to elucidate the stories of ‘the relatively unknown, such as the ignored or oppressed groups whose agenda and meanings have often been neglected in theoretical, practical, and policy issues’ (Tzemopoulos, 2014, p. 276). This article is based on narrative interviews with six refugees from five different countries currently living in Norway.

Recruitment of interlocutors

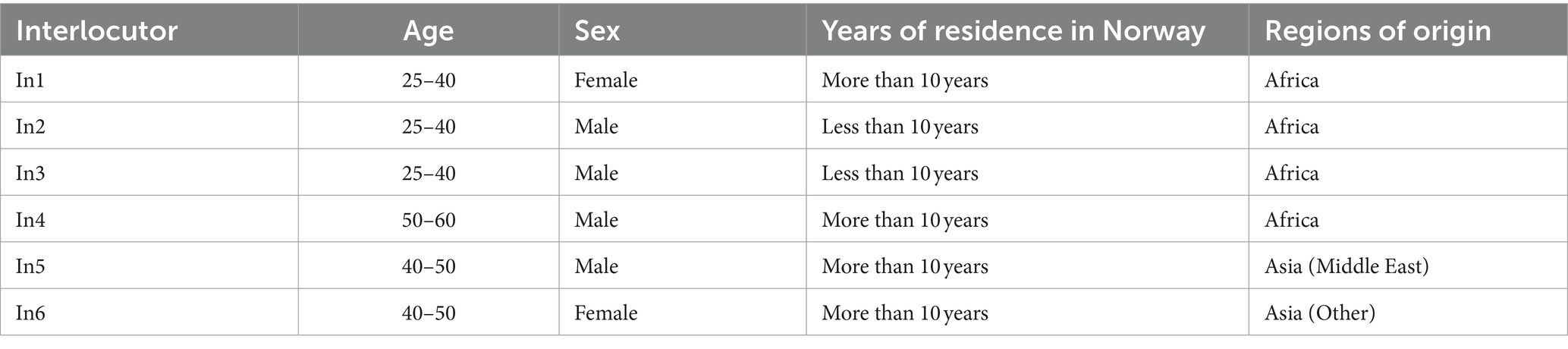

I used a combination of purposive and snowball sampling methods to approach my interlocutors (Merriam and Tisdell, 2016). The purposive sampling helped me to recruit refugees who fulfilled certain criteria. In this case, the target group was refugees who had a plan to pursue higher education but could not do so it in Norway. I directly contacted three refugees with whom I had previous discussions about higher education due to my social position as an associate professor from a refugee background. The motivation for this research was in part the discussions I had with these and other refugees. The snowball sampling method was quite effective in recruiting other refugees. I recruited one of the other three refugees through a refugee from Africa with whom I am personally acquitted. The refugee and I knew each other for quite some time because of our participation in various common social gatherings. I recruited the remaining two refugees through the first refugee. I used pseudonyms from (In1–In6) to represent the interlocutors. “In” stands for interlocutor (Table 1).

The narrative interviews

All interviews but one were conducted face-to-face at places chosen by the interlocutors. I conducted the remaining interview via the encrypted multiplatform messaging app WhatsApp. The interlocutor preferred WhatsApp to other social media platforms. Before I began the interviews, I explained the purpose of the interview and the interlocutors’ rights to remain anonymous and to withdraw from the interview at any time (Burgess, 1989; Mason, 2002). Next, the interlocutors gave informed consent indicating their agreement to be interviewed and audio recoded. The interlocutor whom I interviewed via WhatsApp received the consent form via email and agreed to participate. All interviews but one were conducted in Norwegian based on the preferences of the interlocutors. I audio-recorded all interviews and took field notes during the interviews. However, I translated the transcripts into English to use the verbatim quotes in this article. I did all the translations. The average interview time was about 50 min, and I conducted the interviews during the period June–August 2023.

Data analysis

Narrative data can be represented in many forms such as text, ‘records of interviews’, experiences, pictures and oral records (Creswell, 2013; Mertova and Webster, 2020). Creswell (2013) notes that narrative stories can be analyzed thematically as far as the analysis focuses on what was said. Accordingly, I analyzed the interlocutors’ recoded narratives using thematic analysis and a constructionist framework (Braun and Clarke, 2006). According to Braun and Clarke (2006) thematic analysis is ‘a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data’ (p. 79). I chose the constructionist approach because I wanted to place the refugees’ narratives within sociocultural contexts and explore the structural conditions that had shaped the refugees’ narratives. The version of thematic analysis I employed involved six steps.

First, I familiarized myself with data at different levels—during the interview by listening and taking notes, during transcription and by reading and rereading the transcripts. Second, I began coding the data. Coding was conducted manually using different colors and handwritten notes at the margins of the printouts of the transcripts. At this stage, I reduced the data set to a manageable size by generating codes. For example, I coded narrative stories that dealt with many years of waiting time at reception centres as ‘long waiting time’. I did the same thing with the whole dataset, assigning various codes. Third, I searched for themes. At this stage, I began to collate similar codes to form an ‘overarching theme’. For example, codes that had to do with waiting at reception centres were categorized as ‘time is used as a weapon, and refugees just wait for settlement’. I then further reduced the data set size. Fourth, I reviewed the categorized themes to exclude those that were either not supported by sufficient codes or that did not ‘reflects the meanings evident in the dataset as a whole’ (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p. 91). Fifth, I defined and named the themes, which I expressed in terms of findings. Once I established the essence of the overarching theme, I went back to the data set to support it with verbatim quotes or data extracts. For example, the finding ‘Reception centres as the silent reservoir where time is killed’ was developed from the code I fist called ‘long waiting time’. Finally, I wrote up the findings. During this stage, I applied what Creswell (2013) calls ‘restorying’, which is ‘the process of reorganizing the stories into some general type of framework’ (p. 74). This helped me to create chronological order by taking spatial and temporal elements into consideration (Clandinin and Cain, 2016), a common practice when researchers deal with narrative data (Creswell, 2013). However, it must be noted that that the entire process was iterative rather than linear.

My social position

Savin-Baden and Major (2013) note that qualitative research should facilitate ‘acknowledging and allowing the researcher to have a place in the work’ (p. 71). I am writing this article as an associate professor with a refugee background who came from an African country and who is living in a Western country. My experiences have informed several of my previous studies on refugee higher education in destination countries. During the integration process, as one of my colleagues said, I ‘broke out’ of the pipeline and earned a PhD. However, I remain curious about other refugees’ experiences in the education pipeline in Norway. I cannot claim neutrality or objectivity in the processes of this research. However, I made sure that the article includes the voices of my interlocutors—even when the opinions are against my deep convictions about a given system—rather than it being all about my subjective experiences. To this end, I tried to ensure transparency and fair justification at each stage of the research and avoided pre-established categories or themes during data analysis (Merriam and Tisdell, 2016, p. 212).

Ethical considerations

I obtained ethical approval for the study from the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research. Moreover, as mentioned above, the interlocutors consented to participate and received written information about the purpose of the study, the measures to ensure confidentiality (including secure storage of data obtained through narrative interviews) and their unconditional right to withdraw at any time. I conducted this research in ways that ensured the security and welfare of the interlocutors.

Findings

There is at least one common theme that emerged from the narratives and post-narrative conversations with the interlocutors. Irrespective of their experiences presented below, all interlocutors are grateful for the protection they get in Norway. However, critical questions beg critical responses; and the narratives should be read with this note in mind.

Reception centres as the silent reservoir where time is killed

Reception centres are among the first ‘formal’ institutions many asylum seekers—and by extension refugees—interact within destination countries. Therefore, highlighting the experiences of refugees in these institutions is vital to understand the overall education trajectories of refugees. During the interviews, the refugees stated that the waiting time at reception centres was longer than they expected and that the situations at the centres were characterized by passiveness and the absence of meaningful activities. In this sense, the reception centres in the pipeline context can be thought of as ‘silent reservoirs’. One refugee stated,

I got a residence permit after about six months of my application for protection. However, I had to wait at the reception centre for about two years to get settled [in a municipality] […] During this period, I did not get any information about higher education at all. There was not much to do at the centre either (In1).

As this narrative indicates, the delayed settlement process can reduce the possibility of accessing good quality language courses and relevant information on higher education. This is mainly because it is a prerequisite for refugees to be settled in municipalities to participate in the introduction programme. It is also important to note that lengthy stays at reception centres are negatively correlated with good language acquisition in destination countries (van Tubergen, 2010). Coupled with the lack of information about higher education, this makes the waiting time dull from the refugees’ perspective.

Another refugee reflected retrospectively on her experiences of staying at an asylum seekers reception centre. She stated,

I waited for my residence permit for about three years. It took so long time. In my case, [during the waiting time] I could not go to school. I could not work. It was tiring and stressful. But after three years, I got a residence permit while I was at a reception centre. Then I had to wait for settlement in a municipality. However, those who work at the centre did not care about my settlement. They just say, ‘no, you will get, wait, wait’. I knew there were many who waited. Then I went to [anonymised name of an organisation] and said to them ‘I live with children at a reception centre, it was very difficult, can you come and see how I live?’ They came and took pictures. Then, they helped me to find a municipality and I moved out of the reception centre in few months to settle in a municipality. I never heard about higher education opportunities when I was in the reception centre, never (In6).

This statement is a good example of how time can be used by authorities to keep asylum seekers in limbo. Waiting for a decision for 3 years without the right to work or study is not well received by refugees. This had a psychological impact on the interlocutor as it can be seen from her description of the waiting as ‘tiring and stressful’. It is important to note that waiting a long time is quite common for many asylum seekers and refugees. Given the time of the experience, which was some years back, many may think it has little relevance today. Unfortunately, it seems little has changed, particularly when it comes to non-European refugees. On 30 January 2024, The Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation reported that asylum seekers from an African country waited for 2 years just to get their first asylum interview (Korsvoll, 2024). The statement of the interlocutor also highlights that the intentional involvement of people with authority and decision-making power can shorten the waiting time for settlement in municipalities.

Another refugee found his reception centre stay to be not ‘too long’ as he only stayed there for about one year. Moreover, he mentioned that he began learning Norwegian there. Nevertheless, he witnessed other asylum seekers who waiting for many years. He narrated,

[To live at] the reception centre is difficult because there are many different languages, and you cannot communicate with others because of that. You also share many things including the kitchen, bathroom, living room, and sleeping room with others. There is also an economic challenge for me. I saw also many asylum-seekers who had to wait for many years in the centre [and that] was difficult, but I waited only about one year (In3).

This interlocutor has highlighted how difficult it is to wait for many years based on his observations of others who waited longer than he did. Of note, the diversity of asylum seekers’ and refugees’ languages at the reception centres may pose a challenge in fostering a sense of community at the centres.

Another refugee did not directly mention about the impact of the length of the stay, but it is possible to infer it from the life-changing experiences he went through based on the following statement:

I came as a minor asylum-seeker, and I was sent to an asylum seeker reception for minors. I shared a room with another three minors. Then I moved to another reception centre for adults because I turned 18 and it was no longer allowed to stay at the first reception centre. [After some time] one day I got a message that I got a municipality willing to settle me […] (In5).

Even though the precise time was not mentioned, the fact that the interlocutor transitioned from one age group to another while he was living at a reception centre should not go unnoticed. When refugees who are minors move from one reception centre to another because they become adults, it is inevitable that they also leave their previous school (if any). This may result in lower perceived (school) belonging because they miss out on having consistent friendships, which is ‘especially valuable during early adolescence’ (Ferguson et al., 2022, p. 951). The above narratives indicate that a lengthy waiting time is a common phenomenon but not the only one characterising refugees’ (educational) experiences.

Language schools in municipalities as diverter valves in the pipeline and means of exclusion

The language courses for refugees are double-edge swords, as it can be seen from the narratives of the interlocutors. As important as the processes of learning and acquiring sufficient language proficiency are for refugees in their integration in destination countries, they can be used to deter refugees from progressing to higher education in different ways. A refugee who moved from a reception centre to a municipality and enrolled in a language school narrated that the advice she got from teachers at the school regarding higher education created an ‘impossible picture’ in her mind and discouraged her from pursing higher education in Norway. The refugee narrates,

My goal was to study and advance in education. When you speak with the teachers [of language courses] about higher education, they say ‘no, you should focus on job, it is difficult to study, it is better to work. It is difficult for you [plural form translated from “dere”] to study in Norway. First, you are not born here [in Norway], and second, if you are not born in Norway, it is difficult and it takes time. You must also first learn the language. It is better for you to work. They pushed us out … they scared us when it comes to higher education […] They say, ‘you have children, just focus on work and find a job. Your children can study, but not you’ […] not only me, but there were many who had to change their goals after we completed the introduction programme. I thought also, ‘yes, I must work’. Now, I realise that listening to the advice was the biggest mistake I have done in my life (In6).

This detailed narrative captures several vital points. First, adult education centres or language programmes may be used as platforms to discourage refugees from pursing higher education. Second, not all language teachers have positive attitudes toward refugees, as some teachers stereotypically categorize refugees as people who cannot study at higher levels. This is particularly evident from the word ‘dere’ in Norwegian, which is a plural of ‘you’ in English in this context. By using ‘dere’, the teacher talks about refugees as a group rather than considering them as individuals with unique backgrounds, capabilities and dreams. Third, the language itself is used as a tool of exclusion. There is no reason not to assume that teachers may make it difficult for refugees to learn the language to confirm the self-fulfilling prophecy about how ‘difficult’ it is to learn Norwegian (see Abamosa, 2024). Finally, children are used as scarecrows by teachers to push refugees with small children into low-paying jobs by diverting them from pursuing higher education.

Another refugee talked about how the length of language courses he attended and the topics covered during the language training affected his decision to purse higher education. He stated,

Previously, I saw higher education as a way to self-awareness through which you can change both yourself and your country for better […]. I think there is a huge problem when it comes to Norwegian language teaching process. For example, I went to the language course for about four months […]. Language courses should focus more on communication skills. In the classroom, I did not learn about the skills. I learned about how to make bed, how to take care of the older people, characteristics of dementia […]. I do not need all this. I only need to learn the langue deeply because I believe it could change me for better […]. When you tell them about your high ambitions of studying [at higher level], they say ‘it is better if you forget that’. When you ask ‘why?’, they say, ‘it takes minimum 9 years to graduate, to get job … Why don’t you work in the homecare service? It is better for you’. Eventually, you believe as if your fate is in their hand. This demoralised me (In2).

This indicates the role of the language training centres or schools in diverting refugees’ focus from pursuing higher education. This can be done in at least two ways, as indicated in the statement. First, the language programmes refugees attend are designed for specific areas of the labor market rather than to equip refugees with the skills necessary to navigate the higher education system. Second, the people working in the schools discourage refugees from pursuing higher education by scaring them about how long it takes to complete a degree programme at a university. Unfortunately, some refugees may fall for this and let go of their dream of enrolling at a higher education institution. This shows that language learning centres can in fact be areas where refugees are deskilled.

Another refugee vividly remembers her experiences of a language course (school). She stated,

When you say you will study at a university, the teachers say ‘you [plural translated from dere] need time, it is not easy […] you are foreigners and you cannot speak and write the Norwegian language, it takes time to go further.’ But [I know] it is not because we are foreigners that we cannot study. There are many foreigners in higher education. Now I say, if you are interested, you can achieve what you will. No one is born dump. All have a thinking brain […] but you give up when people tell you that it takes long time, you are a foreigner and the like. You hear many negative things, and all this has influenced me (In1).

This is another indication of the role language schools play in hindering and demotivating refugees who aspire to pursue higher education. Despite negative experiences, many refugees are ready to advise other refugees not to give up if they plan to pursue higher education.

Another refugee who acknowledges the importance of higher education stated how difficult it is to navigate the system in Norway.

Higher education is much better for us. However, to go to a university you need a better Norwegian proficiency level. When I came to Norway, there was no opportunity to attend a Norwegian language course for the purpose of higher education […]. Then, I tried to enrol in normal school to learn the language, they said ‘it is full, there is no place’. They then said to me, ‘you can apply to [name of an organisation] on your own’. But it was very difficult for me to attend courses at the [name of the organisation] because the time at which they offer the courses did not fit with my plan. Also, they advised me to go to apprenticeship and get job rather than focusing on education. I had a job at that time, and finally I continued to work […]. I used to work in different places for 2, 3, or 4 hours as a janitor […]. It is much better to study at a university, but the government must help those [refugee] who want to study. I wish I went back in time and purse higher education until PhD. If you have a PhD, you can help many people (In4).

This statement confirms the value refugees place on higher education and their awareness of the importance of mastering the Norwegian language for admission to higher education institutions. However, refugees’ awareness and high ambitions alone are not enough to realize their dream of pursing higher education because the path to higher education is far from straightforward. Refugees have to navigate complex and opaque systems that are not necessarily in favor of refugee higher education. The above statement indicates that schools are used as diverting places by advising refugees to search for job at the expense of pursing higher education. By the time the refugees realize the difficulty of getting out of the downward mobility circle of unsecure jobs, they wish to go back in time and choose a different path than the one they were advised to take. It is not only about telling refugees what is ‘best’ for them that is stuffing the education pipeline. Equally damaging is the (implicit) effect of repressing or holding back relevant information about higher education.

Withholding information about higher education as a means of exclusion

All the refugees narrated that they have never got any information about higher education from the organizations they were in contact with during their integration process. One refugee stated that he got relevant information about the possibility of studying further in Norway on his own. Even so, he said that all his friends (or classmates) have not got any information about higher education as far as he recalls. He recounted,

I am lucky. No one from my classmates went further to study and complete upper secondary school or higher level because no one knew that it was possible. Before I came to Norway, my goal after I got protection was to work. But once I was in Norway, I understood that I had few opportunities without further education. Then I tried to look for information about education, and that was how I got information. I used the information to complete upper secondary education but could not continue further (In3).

The lack of timely and correct information on the possibility of pursing higher education in Norway may pose a serious challenge to refugees wishing to pursue higher education. The fact that the interlocutor mentioned above got information about higher education indicates that it is not necessarily the unavailability of information that is an issue. Rather, it is the withholding of relevant information at schools that is a challenge and that may lead to the exclusion of refugees from higher education. Another refugee’s experiences were quite different from those of In3 and more similar to his classmates’ experiences. When asked about any information and help she gets from different organizations, some of which I mentioned in the section ‘Refugees and the Settlement Process in Norway’ section in this article, she narrated,

I have not got any information and any help about higher education from any organisation. They just said, ‘go to apprenticeship, search for job, find job’. This was what I used to hear (In6).

This is another indication that access to relevant information on higher education is not something to be taken for granted by refugees. The above narrative clearly indicates that the organizations involved in the integration of refugees not only fail to provide refugees with necessary and clear information on higher education, but they also suggest (low-skilled) employment is the only option and thereby block the path to refugee higher education.

One refugee felt he was forced—in part due to a lack of correct information—into training programmes, which, in his words, ‘did not help him to realize his dreams’. He stated,

I had to spend two years and four months in different courses and apprenticeship. I feel I was forced to kill my time. During all this time, I did not get information on higher education. Even when you mention about higher education, they demoralise you (In2).

The scarcity of information on higher education is therefore not accidental. It is rather a systemic issue. The fact that refugees do not get enough information after spending more than 2 years in the integration process is a clear indication of this. It is also noteworthy that mentioning higher education may have negative implications for refugees.

Another refugee reflected on her mixed experiences and mentioned a lack of information from concerned bodies. She had to say,

I can say I did not get any information about higher education particularly at reception centre[…]. After I moved from the reception centre to a municipality, I got vague information about the requirements and the route to higher education in Norway. If you ask me now, I cannot tell you what is required to go to a university in simple terms; [and] this is because of lack of information (In1).

The reception centres are devoid of information on higher education. Once refugees settle in municipalities, they may get information. However, even when there is a piece of information on the possibilities of pursing higher education, it may not be well defined and clear, leaving refugees confused.

However, it should be noted that some refugees may intentionally not ask for information due to experiences they had before their arrival in Norway. One refugee stated,

I never tried to talk about my story [to] anybody and ask for information about education or health because of negative experiences I had to endure in my home country. But I think I would have got information had I asked for information (In5).

Finally, some of the refugees end their journey through the pipeline with employment, although not necessarily positions that are decent or secure. Worryingly, they consider it as the final phase of their integration journey in Norway. This indicates how layers of systems can result in irreversible decisions even when the decisions are not in favor of the personal development of refugees.

Work as an imaginative final destination of the journey through the pipeline

The experiences refugees have had over time in Norway have left the impression that getting a job—irrespective of the nature of the job—is the final destination they should or even could reach through the integration pipeline. One refugee narrated,

I got job at [name of the company] after the manager of the company visited us at our school looking for employees. I was relatively better in speaking Norwegian at that time. Then, I started working there and later stopped everything, including getting economic benefit from the government and attending Norwegian language. At that time, they did not need high proficiency in Norwegian because of the nature of the work (In5).

This statement highlights how refugees may be wanted to fill some vacancies, primarily to benefit the employers. It also seems that finding an employment was not always difficult for refugees. However, the harsh reality is that employment means the interruption of language courses, which in turn can be interpreted as explicit exclusion from higher education.

As mentioned above, the labor market which refugees join is not necessarily favorable in terms of their upward social mobility, as is higher education. One refugee related,

Since I came to Norway, I have worked in different companies, including a cleaning job on temporary basis. Now, I am working as a cleaner (In3).

Another refugee uses this opportunity to send a message to another refugees. She stated,

I had a vision of being a medical doctor. But I had no choice. I was forced to work in canteen… But at the end, I say to other refugees ‘Don’t listen to people who say to you, “you cannot!”’ (In6).

Another refugee narrated,

I had no choice. When you have no one to help you with many issues, you just pick the nearest opportunity. So, I had to choose the current job I am working (In1).

All these narratives indicate that refugees may be forced (or may be desperate enough) to take up any employment opportunity they come across irrespective of their ambitions for higher education and the nature of the job. This may not be surprising given the refugee integration system that stresses the economic self-sufficiency of refugees as quickly as possible (Abamosa, 2023b). However, the question of at what cost must not be underemphasised. For example, the following statement by a refugee who sustained a permanent injury while working and cannot continue in his job as a result is a case in point. He stated, ‘I got injured while I was working, and I can no longer continue working. Now, I am unemployed as a result’ (In4).

Discussion

The findings I presented above yield some interesting points that need to be discussed in light of the theoretical framework.

The reality of the refugee education pipeline

Most of the restrictive challenges presented in the findings that hamper refugees’ possibilities of becoming knowledge producers do not exist in a vacuum. They are embedded in social systems, such as the education systems, including language training programme for refugees. However, language training programmes or even primary or secondary schools alone do not constitute a complete refugee higher education pipeline. They are just part of the whole picture. Therefore, it is not an exaggeration to claim that the refugee education pipeline stretching from reception centres to higher education institutions is virtually non-existent or at the very least vague for many of the refugees in Norway. Dryden-Peterson and Giles (2012) argue that refugees often face a broken higher education pipeline, mainly because the ‘provision of higher education for refugees has been overshadowed by persistent challenges to access and quality in primary and secondary education’ (p. 7). This is undoubtedly a sound argument, but in contexts such as Norway where access to (and the relative quality of) primary and secondary education is not an issue, the broken pipeline can be explained by other factors.

At least three factors can explain the broken education pipeline that refugees in Norway may (not) pass through. First, refugees are exposed to a vicious circle of downward mobility. Refugees move from apprenticeship to apprenticeship or temporary job to temporary job before they finally end up with more permanent low-skilled positions (some of them against their will or due to a lack of alternatives) rather than moving upward through a ‘normal education pipeline’. This corroborates the findings of a study from the US that states, ‘refugees are often placed in entry-level and low-wage positions’ and remain marginalized in American society (Koyama, 2015, p. 618). Strikingly, language teachers, and even advisers, ‘encourage’ refugees to take up those positions at the expense of pursing higher education. This raises the question of whether the main driving force for Norway to accept (adult) refugees is to fill the vacant low-skilled positions. Indeed, a 2016 White Paper (Justis-og beredskapsdepartementet, 2016) encourages such an approach. Therefore, the teachers and advisers are serving as switchmen in determining which parts of the pipeline should be opened and closed based on the interests that integration policy is designed to serve (Murphy, 1988).

Second, refugee integration is characterized by, among other things, the nonexistence of a pure education pipeline from lower-level education to higher-level education mainly for refugees. The main argument behind the importance of such a pipeline is the unique and complex challenges refugees face in their educational trajectories (Mayr and Oppl, 2023), ‘which cannot be overcome without deliberate changes to outreach and support’ (Lambrechts, 2020, p. 820). The absence of such a well-designed pipeline leaves refugees in tangle of activities such as language training, social civic education and work apprenticeship, mainly aimed at directing them to the employment positions described above. This might confuse refugees who are new to the country and its many systems, as also documented by another study concerning other European countries (Koehler and Schneider, 2019).

In addition, street-level bureaucrats may channel refugees to the low-skilled labor market by capitalising on the confusion of refugees or on the vagueness of the system. One of the motivations for doing this might be the pressure ‘to meet performance standards’ by getting as many refugees as possible into the world of ‘employment’ (Darrow, 2015). However, this constitutes no less than denying refugees the right to realize their potential through higher education, particularly when it is done without the willingness of and in consultation with the refugees themselves.

Finally, the current broken pipeline may be the continuation of previous practices. There is a huge difference between the current labor market situation in Norway and the one that existed several decades ago. There were comparatively much more vacant positions that required a lower educational level some years ago. However, this trend has been changing, as the number of vacant positions that require no higher education is getting smaller and smaller (Kitterød, 2002). In other words, even from a neoliberal perspective, refugees must access higher education to secure a safe and better position in the labor market (Abamosa, 2023b). However, this necessarily requires adjustment of the ‘integration pipeline’ in general and of the education pipeline in particular. The interlocutors’ narratives, alas, indicate the broken education pipeline leads refugees nowhere near higher education. In fact, language classes or schools are used as diverter valves to direct refugees to low-skill employment. This is evident from the refugees’ statements indicating the various techniques language teachers use to divert the attention of refugees from higher education.

Threatening refugees’ agency

Refugees’ pathways to be successful in achieving their dreams of pursing higher education and to eventually become knowledge producers are not straightforward in Norway, similar to many other destination countries (e.g., Gren, 2020). One of the main challenges refugees face in their trajectories to become knowledge producers is threatened agency. As the above narratives indicate, the more powerful actors—in this case street-level bureaucrats—threaten refugees’ agency by undermining their goal of further study. Refugees, by virtue of their immigration background, are obliged to make decisions in restrictive situations that characterize thin agency. Based on the findings, at least four factors can be said to restrict refugees’ agency.

First, time is used as a main weapon to weaken refugees’ agency. By making refugees wait for various decisions (e.g., the decision about a residence permit and the decision about settlement in a municipality), those with power put refugees in a helpless situation. In such cases, refugees may succumb to the authorities’ demands—including letting go of the dream of higher education—to get out of the limbo in which they are stuck, or they may even become inactive and docile. This is in line with a study from Germany indicating that German authorities use time to infantilise refugees, relegating them to ‘a life of waiting and sleeping’ (Stan, 2018, p. 796). Second, withholding information about higher education is used to weaken refugees’ agency. The fact that refugees do not get clear and timely information about higher education in the integration process may weaken their agency in terms of making informed decisions as early as possible. This is a significant challenge during settlement in a new country (Bajwa et al., 2017). Third, demotivation and misplaced advice are used to weaken refugees’ agency Demotivating refugees and advising them not to pursue higher education during their language training programme is also a threat to refugees’ agency. Many refugees may listen and eventually give up their dreams because some other opportunities are at stake. For example, they miss out on the opportunity of attending language courses in full and may be sanctioned financially if they do not follow the advice to search for low-skilled and often insecure positions. Even though some studies show some refugees fight back in such cases (e.g., Abamosa, 2024), this is not the case in the current study. Finally, language programmes for non-academic purposes are used to weaken refugees’ agency. The provision of language training programmes that do not necessarily prepare refugees for academic purposes is another threat to refugees’ agency. This in line with the findings of a study by Djuve and Kavli (2019) from Norway that indicate the language training programmes incorporated in the introductory programme for refugees focus on employment and that there is minimal focus on the formal education of refugees. Refugees often have little or no choice to opt out of the state-sponsored language training programmes. Therefore, as one refugee said, they would learn ‘how to make bed, how to take care of the older people, [and about] characteristics of dementia’ rather than learn skills that would enable them to enrol and succeed in higher education institutions.

Refugees and knowledge production or higher education

The discussion based on the pipeline analogy and agency theory confirms the common assumption about refugees in many Western destination countries, which is that they are incapable of pursuing higher education to become knowledge producers (Gren, 2020). Instead, they are expected to fill positions deemed suitable for them under the pretence of economic self-sufficiency (Koyama, 2015; Vlachou and Tlostanova, 2023; Abamosa, 2023b). However, both the assumptions and positions have little to do with what refugees could achieve under normal circumstances. Mistry (2024) argues that refugees should be viewed as ‘knowledge producers and historical narrators in their own right […] capable of authoritatively speaking to structures, norms, and processes that condition their lived experience’ (p. 33) (see also the edited volume by Reed and Schenck, 2023 and the work by Kmak and Björklund, 2023 for more). In fact, this may not always be possible because knowledge production is mediated by various factors. For instance, Teferra (2023) finds that refugees are offered substandard education because ‘their refugeeness matters more to the educational system rather their achievement or their potential’ (p. 64). In similar vein, Abamosa (2024) argues that refugees are offered mediocre language courses so that they cannot acquire the language proficiency necessary for admission to higher education. In other words, refugees may be subject to certain social arrangements or systems that force them to remain outside the realm of knowledge production through higher education.

Conclusion

In this article I aimed to address the research question, ‘How does the integration process in a Western destination country contribute to the exclusion of refugees from knowledge production?’ Let me draw a parallel between my concluding remarks and the statement of Sue V. Rosser, Director of Women’s Studies at the University of South Carolina: ‘The pipeline is leaking women. And unless this country does something to plug those leaks, women will continue to be denied opportunities in rewarding, high-paying careers and this country is going to be worse for it’ (Alper, 1993, p. 409). In this article, I recontextualise the statement to refer to refugees, irrespective of gender. The refugee education pipeline is broken and stuffed with various elements, some of which force refugees to change their goal of pursing higher education to searching for low-paying positions. Even though refugees are people with agency, their abilities to make informed decisions regarding higher education are weakened by layers of factors embedded in the integration processes. Long waiting times, the withholding of information about higher education, demotivating and misplaced advice and language training programmes for non-academic purposes are examples of factors that stuff the refugee education pipeline in Norway. Therefore, it should not be surprising that refugees are underrepresented in both higher education and faculty in Norway.

The study has some implications. The state should consider establishing a clear refugee education pipeline from the lower levels of education to higher education. All street-level bureaucrats must take the goals and ambitions of refugees seriously and work with refugees so they can achieve their goals. All refugees who have the willingness and the capacity to pursue higher education must make it clear and fight for their right to realize their potential. Future research should focus on intersectional dimensions to explore the role various characteristics such as disability, nationality and gender play in refugees’ journey to become knowledge producers through higher education.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research. All have been informed and have given consent to participate. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

JA: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the interlocutors for sharing their experiences with me. I am also grateful to German Institute of Development and Sustainability (IDOS) in Bonn for the facilities they provided me during my fellowship stay in Fall 2023. Finally, I thank all my colleagues who gave me critical feedback on the draft of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abamosa, J. Y. (2023a). “Navigating hostile environments: refugees’ experiences in higher education institutions in Western countries” in Global perspectives on the difficulties and opportunities faced by migrant and refugee students in higher education. eds. S. Tawfeeq and M. Zhang (Pennsylvania, PA: IGI Global), 31–56.

Abamosa, J. Y. (2023b). The Peripherality of social inclusion of refugees into higher education: insights from practices of different institutions in Norway. High Educ. Pol. 36, 73–92. doi: 10.1057/s41307-021-00249-7

Abamosa, J. Y. (2024). Challenging false generosity through disruptive pedagogy in Western countries’ education systems–the case of Norway. Nordic J. Pedagogy Critique 10, 83–98. doi: 10.23865/ntpk.v10.5887

Abamosa, J. Y., Hilt, L. T., and Westrheim, K. (2020). Social inclusion of refugees into higher education in Norway: a critical analysis of Norwegian higher education and integration policies. Policy Futures Educ. 18, 628–647. doi: 10.1177/1478210319878327

Achiume, E. (2014). Beyond prejudice. Structural xenophobic discrimination against refugees. Georgetown J. Int. Law 45: 2, 323–382. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2294557

Adserà, A., Andersen, S., and Tønnessen, M. (2022). Does one municipality fit all? The employment of refugees in Norway across municipalities of different centrality and size. Eur. J. Popul. 38, 547–575. doi: 10.1007/s10680-022-09618-3

Ahern, L. M. (2001). Language and agency. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 30, 109–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anthro.30.1.109

Alper, J. (1993). The pipeline is leaking women all the way along. Science 260, 409–411. doi: 10.1126/science.260.5106.409

Arar, K. H. (2021). Research on refugees’ pathways to higher education since 2010: A Systematic Review. Rev. Education 9:e3303. doi: 10.1002/rev3.3303

Askim, J., and Steen, A. (2020). Trading refugees: the governance of refugee settlement in a decentralized welfare state. Scand. Polit. Stud. 43, 24–45. doi: 10.1111/1467-9477.12158

Aspøy, T.M., Kavli, H.C., and Tønder, A.H. (2023). “Da Klokka Klang…Utdanningens Plass i Integreringspolitikken” [“When the Bell rang… Education’s place in the integration policy”], in Ulikhetens Drivere og Dilemaer [the causes and dilemmas of inequality], eds. T. Fløtten, H.C. Kavli, and S. Trygstad Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 239–257.

Bacher, J., Fiorioli, E., Moosbrugger, R., Nnebedum, C., Prandner, D., and Shovakar, N. (2020). Integration of refugees at universities: Austria’s MORE initiative. High. Educ. 79, 943–960. doi: 10.1007/s10734-019-00449-6

Bajwa, J., Couto, S., Kidd, S., Markoulakis, R., Abai, M., and McKenzie, K. (2017). Refugees, higher education, and informational barriers. Refuge 33, 56–65. doi: 10.7202/1043063ar

Bandura, A. (2006). Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 1, 164–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00011.x

Berg, J. (2023). Higher education for refugees: relevance, challenges, and open research questions. SN Soci. Sci. 3, 1–25. doi: 10.1007/s43545-023-00769-6

Bjånesøy, L., and Bye, H. H. (2023). Norwegian citizens’ responses to influxes of asylum seekers: comparing across two refugee crises. Soc. Influ. 18:2242619. doi: 10.1080/15534510.2023.2242619

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brochmann, G., and Hagelund, A. (2012). “Comparison: a model with three exceptions?” in Immigration policy and the Scandinavian welfare state 1945–2000. eds. G. Brochmann and A. Hagelund (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 225–275.

Burgess, R. G. (1989). “Ethics and educational research: an introduction” in Social research and educational studies series. ed. R. G. Burgess (New York: The Falmer Press), 1–11.

Clandinin, D. J., and Cain, V. L. (2016). Engaging in narrative inquiries with children and youth. New York: Routledge.S., and Huber, J

Cooper, B . (2005). Norway: Migrant quality, not quantity. Migration policy institute. Available at: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/norway-migrant-quality-not-quantity (Accessed September 16, 2023).

Cooper, C. R. (2011). Bridging multiple worlds: Cultures, identities, and pathways to college. New York: Oxford University Press.

Crawley, H. (2021). The politics of refugee protection in a (post)COVID-19 world. Soc. Sci. 10:81. doi: 10.3390/socsci10030081

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dankertsen, A., and Lo, C. (2023). “Introduction” in The end of Norwegian egalitarianism? Limits and challenges to a cherished idea. eds. A. Dankertsen and C. Lo (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget), 9–24.

Darrow, J. H. (2015). Getting refugees to work: a street-level perspective of refugee resettlement policy. Refug. Surv. Q. 34, 78–106. doi: 10.1093/rsq/hdv002

Davies, T., Isakjee, A., and Obradovic, J. (2023). Epistemic Borderwork: violent pushbacks, refugees, and the politics of knowledge at the EU border. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 113, 169–188. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2022.2077167

Détourbe, M., and Goastellec, G. (2018). Revisiting the issues of access to higher education and social stratification through the case of refugees: a comparative study of opportunity for refugee students in Germany and England. Soc. Sci. 7:186. doi: 10.3390/socsci7100186

Djuve, A. B., and Kavli, H. C. (2019). Refugee integration policy the Norwegian way–why good ideas fail and bad ideas prevail. Transfer 25, 25–42. doi: 10.1177/1024258918807135

Dryden-Peterson, S., and Giles, W. (2012). Higher education for refugees. Refuge 27, 3–9. doi: 10.25071/1920-7336.34717

Elder, G. H. Jr. (1994). Time, human agency, and social change: perspectives on the life course. Soc. Psychol. Q. 57, 4–15. doi: 10.2307/2786971

Ferguson, S., Brass, N. R., Medina, M. A., and Ryan, A. M. (2022). The role of school friendship stability, instability, and network size in early adolescents’ social adjustment. Dev. Psychol. 58, 950–962. doi: 10.1037/dev0001328

FitzGerald, D. S. (2019). Refuge beyond reach. How rich democracies repel asylum seekers. New York: Oxford University Press.

Friberg, J. H., and Midtbøen, A. H. (2018). Ethnicity as skill: immigrant and employment in hierarchies in Norwegian low-wage labour markets. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 44, 1463–1478. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2017.1388160

Gowayed, H. (2022). Refuge: How the state shapes human potential. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Gren, N. (2020). “Living bureaucratisation: Young Palestinian men encountering a Swedish introductory Programme for refugees” in Refugees and the violence of welfare bureaucracies in northern Europe. eds. D. Abdelhady, N. Gren, and M. Joormann (Manchester: Manchester University Press), 161–179.

Hagelund, A. (2005). Why it is bad to be kind. Educating refugees to life in the welfare state: a case study from Norway. Soc. Policy Adm. 39, 669–683. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9515.2005.00463.x

Haw, A. L. (2020). Duelling discourses: a rhetorical device for challenging anti-asylum sentiment in Western Australia. J. Aust. Stud. 44, 303–317. doi: 10.1080/14443058.2020.1737178

Heinemann, A. M. B. (2017). The making of ‘good citizens’: German course for migrant and refugees. Stud. Educ. Adults 49, 177–195. doi: 10.1080/02660830.2018.1453115

IMDi . (2021). Bosetting av Flyktninger Wom Finner Bolig på Egen Hånd. [Settling of Refugees Who Find Housing On Their Own]. Available at: (https://www.imdi.no/planlegging-og-bosetting/bosettingsprosessen/selvbosetting/).

IMDi . (2023). Opplæring i Norsk og Samfunnskunnskap for Asylsøkere i Mottak–Integreringsloven. [training in Norwegian and civics for asylum seekers in reception – The integration act]. Available at: https://www.imdi.no/kvalifisering/regelverk/kvalifisering-i-mottak/opplaring-i-norsk-og-samfunnskunnskap-for-asylsokere-i-mottak---integreringsloven/ (Accessed September 23, 2023).

Integreringsloven . (2020). Lov om Integrering Gjennom Oplæring, Utdanning og Arbeid. [law on integration through training, education and work] (LOV-2020-11-06-127). Available at: https://lovdata.no/lov/2020-11-06-127/§13 (Accessed September 14, 2023).

Justis-og beredskapsdepartementet . (2016). Fra Mottak til Arbeidsliv: En Effektiv Integreringspolitikk [white paper] [from reception to employment: An effective integration policy]. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld.-st.-30-20152016/id2499847/ (Accessed September 20, 2023).

Kitterød, R. H. (2002). Hjemmearbeid Blant Foreldre-Stor Oppmerksomhet, men Beskjedent Omfang [homework among parents-great attention, but modest scope]. Samfunnsspeilet 16, 65–77.

Klocker, N. (2007). “An example of ‘thin’ agency: child domestic Workers in Tanzania” in Global perspectives on rural childhood and youth: Young rural lives. eds. R. Panelli, S. Punch, and E. Robson (New York: Taylor & Francis), 83–94.

Kmak, M. (2015). Between citizen and bogus asylum seeker: Management of Migration in the EU through the Technology of Morality. Social Ident. 21, 395–409. doi: 10.1080/13504630.2015.1071703

Kmak, M., and Björklund, H. (Eds.) (2023). Refugees and knowledge production: Europe’s past and present. Abingdon: Routledge.

Kobberstad, J. H. (2023). “Labor market integration of refugees: a blind spot of Norwegian egalitarianism?” in The end of Norwegian egalitarianism? Limits and challenges to a cherished idea. eds. A. Dankertsen and C. Lo (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget), 77–101.

Koehler, C., and Schneider, J. (2019). Young refugees in education: the particular challenges of School Systems in Europe. Comp. Migr. Stud. 7, 1–20. doi: 10.1186/s40878-019-0129-3

Kondacki, Y., Kurtay, M. Z., Kasikci, S. K., Senay, H. H., and Kulakoglu, B. (2023). Higher education for forcibly displaced migrants in Turkey. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 42, 619–632. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2022.2106946

Korsvoll, A.S . (2024). Bifituu og Dibora Har Venta i to Ǻr På å Få Søkje Asyl. [Biftu and Dibora have waited for two years to apply for asylum]. NRK. Available at: https://www.nrk.no/vestland/asylsokarar-ma-vente-i-to-ar-pa-a-fa-asylintervju-1.16728748 (Accessed March 3, 2024).

Koyama, J. (2015). Learning English, working hard, and challenging risk discourse. Policy Fut. Educ. 13, 608–620. doi: 10.1177/1478210315579547

Lambrechts, A. (2020). The super-disadvantaged in higher education: barriers to access for refugee background students in England. High. Educ. 80, 803–822. doi: 10.1007/s10734-020-00515-4

Lenette, C., Baker, S., and Hirsch, A. (2019). “Systemic policy barriers to meaningful participation of students from refugee and asylum seeking backgrounds in Australian higher education neoliberal settlement and language policies and (deliberate?) challenges for meaningful participation” in Educational policies and practices of English-speaking refugee resettlement countries. ed. J. L. McBrien (Liden: Brill Sense), 88–109.

Lipsky, M. (2010). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Malmo, V.K . (2020). Nytt Avslag for Familien Som Ingen Vil Bosette [new rejection for the family that no one wants to settle]. NRK, 19 June. Available at: https://www.nrk.no/tromsogfinnmark/nytt-avslag-for-familien-som-ingen-vil-bosette-1.15059553 (Accessed September 17, 2023).

Mayr, A., and Oppl, S. (2023). Higher education at the margins - success criteria for blended learning systems for marginalized communities. Educ. Inf. Technol. 28, 2579–2617. doi: 10.1007/s10639-022-11282-3