94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Educ. , 25 January 2024

Sec. Higher Education

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1330456

Service-learning integrates community service with academic study. Students apply skills and knowledge in practical situations and reflect on their experiences. Our 3000-level service-learning college course, Leadership Development in Agricultural Sciences, involved student-led development and execution of a one-day event, “AgCamp,” held on a university campus for high school students. The objective of this study was to evaluate if an intervention (i.e., a service-learning project) changed undergraduate students’ perceptions of their ability to collaborate, ability to lead, and overall perceptions of the usefulness of service-learning. An electronic mixed methods questionnaire-based survey was developed, tested for validity and reliability, and distributed to college students enrolled in Leadership Development in Agricultural Sciences as a pre- and post-test at the beginning and end of two semesters. Data were analyzed in SPSS 26.0 using measures of central tendency and paired sample t-tests. Undergraduate students’ (n = 74) had positive perceptions of service-learning entering the semester, all measures of which improved as a result of their experiences in the course. In comparison with traditional courses, students felt service-learning courses have more societal benefits and should be increasingly offered. Participating in the service-learning project significantly increased students’ comfort working with people from different cultures or backgrounds and empowered them in different ways, including with decision-making. Ultimately, our data indicate that students enjoyed service-learning and received soft skill development through the course. We recommend service-learning be increasingly integrated into post-secondary curriculum.

Service-learning is an experiential pedagogy that combines learning through action, structured engagement with community partners, and reflection to facilitate deep learning and increase skill transfer (Bringle and Hatcher, 1995; Charity Hudley et al., 2017; Turk and Pearl, 2021). As a “high-impact practice,” service-learning helps students develop real-world skills through hands-on learning and delivers outcomes that reflect those of our complex world (Kuh, 2008).

The skills and ideals developed during participation in service-learning courses are not only those that are valued in a democratic society, but are also those that our education systems were created to foster (Dewey, 2001; Wahlström, 2022), and are critical for college student success (e.g., self-regulation, leadership, civic engagement). Therefore, there is a sense of urgency for research that not only explores the outcomes of service-learning courses, but also assesses student perceptions of these courses. If students have poor perceptions of service-learning and its potential outcomes, then enrollment in courses could suffer and these critical skills would need to be fostered through other modalities.

While there is vast research on the outcomes of service-learning (Celio et al., 2011; Gupta et al., 2011; Anderson et al., 2019; Bastida-Escamilla et al., 2022; Narong and Hallinger, 2023), there is a deficit of literature that assesses student perceptions about service-learning and/or their service-learning experiences (Matthews and Zimmerman, 2009; Colvin, 2020). Our research seeks to build on the limited repository of literature on student perceptions of service-learning to address this knowledge gap. While most of the existing perception-based research seeks student perceptions on the service-learning program or course itself (Currie-Mueller and Littlefield, 2018; Keles and Altinok, 2020; Xavier and Jones, 2021; Williams, 2022), it is also important to ask students about their perceived benefits of service-learning as compared to the benefits of a traditional course. By focusing on student perceptions, it is possible to portray apprehensions and outlooks regarding service-learning to better inform course and program practices (Xavier and Jones, 2021). To this end, the objective of this study was to evaluate if an intervention (i.e., a service-learning project) changed undergraduate students’ perceptions of their ability to collaborate, ability to lead, and overall perceptions of the usefulness of service-learning—particularly as it compares to traditional coursework.

There are various theoretical frameworks related to service-learning. In John Dewey’s seminal book, Experience and Education (1938), he advocated for learning by doing. He posited that students must be able to put into practice what they learn as a means of connecting theory to practice but that students lacked the experience to contextualize abstract concepts of the classroom. Therefore, Dewey (1938) indicated that classrooms were responsible for training students for the real world via experiential learning. Kolb (1984) extended Dewey’s focus from primary/secondary school to higher education. Kolb (1984) argued that learning happens when one experiences knowledge being created during a transformative experience. His experiential learning cycle emphasized the routine of engaging in an activity and then actively reflecting on what was learned and how it related to oneself and one’s goals. Although several other theoretical frameworks have been created for service-learning, the frameworks from Dewey (1938) and Kolb (1984) remain the most widely utilized (Salam et al., 2019).

The service-learning classroom provides access to customized and contextualized learning opportunities, which are demonstrably effective in both developmental- (Turk and Pearl, 2021) and college-level (Narong and Hallinger, 2023) coursework. Previous research indicated that service-learning increases sense of responsibility (Gupta et al., 2011; Turk and Pearl, 2021), diversity of thought (Zlotkowski, 1996; Narong and Hallinger, 2023), communication (Celio et al., 2011; Gupta et al., 2011; Anderson et al., 2019), professional ethics (Gupta et al., 2011; Narong and Hallinger, 2023), deep learning (Gupta et al., 2011; Turk and Pearl, 2021), collaboration (Celio et al., 2011; Gupta et al., 2011; Anderson et al., 2019), and value for civic engagement (Celio et al., 2011; Eppler et al., 2011; Gupta et al., 2011; Battistoni, 2013). Increases in affect and self-regulatory behavior (e.g., self-esteem, motivation) have also been documented as service-learning outcomes (Matthews and Zimmerman, 2009; Celio et al., 2011; Gupta et al., 2011). A recent systemic review from Salam et al. (2019) indicated that there were course content specific outcomes such as concept application (Hart, 2015), academic learning (Salam et al., 2017), self-directed learning, problem-solving, and critical thinking (Fullerton et al., 2015; Bowie and Cassim, 2016) associated with service-learning. Other benefits, relevant to engagement in society, were also present and include enhanced civic responsibility (Fullerton et al., 2015), personal growth (Rutti et al., 2016), communication competencies (Sass and Coll, 2015), and community self-efficacy (Gerholz et al., 2017).

The Texas State University Institutional Review Board approved this research (#7980) and participants provided written consent prior to participation. This research was integrated into a graded course and students were given a completion grade for taking the surveys described here, but were allowed to opt out of research by selecting “I do not consent.” Those responses were not included in the final dataset.

We assessed the impact of developing and hosting an event, “AgCamp,” through a service-learning platform on undergraduates enrolled in a credit-bearing 3000-level course, Leadership Development in Agricultural Sciences, in the Department of Agricultural Sciences at Texas State University. This course is required for all majors in the department (i.e., Agriculture, Agricultural Business and Management, Animal Science) and ∼30–40 students generally enroll in the course per semester.

The service-learning intervention in this research was called AgCamp, a free one-day event where high school students visited a university campus to learn about agriculture and engage with the university community. AgCamp included an introductory address; lessons and hands-on demonstrations in animal science, horticulture, and agriculture mechanics; lunch; a lesson on United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) career pathways; campus/facility tours; and small groups where college and high school students had unstructured interactions.

This intervention (i.e., AgCamp) was developed and implemented because of the known value of service-learning for college students, as discussed above, and based on other literature that demonstrates the benefits of short-term programming for increasing youth’s knowledge of agriculture in our daily lives (Luckey et al., 2013; Ongang’a et al., 2020) and of agricultural sciences and natural resources careers (Jean-Philippe et al., 2017). We also wanted to provide high school students with opportunities to interface with their college near-peers as these interactions could shape their views of themselves in college (Detgen et al., 2021; Hooker and Brand, 2010; Swanson et al., 2021), with potential to build confidence in pursuing a post-secondary degree.

All AgCamp activities were developed and delivered by college students enrolled in the Leadership Development course. Early in the semester, enrolled students were divided into one of ten cohorts (i.e., Demonstrators or Lecturers of: animal science, horticulture, or agricultural mechanics; Marketing and Communication Coordinators; Event Fundraisers and Coordinators; Logistics Coordinators; and Event Moderators). Each cohort included ∼3–5 students; the instructor provided cohorts with a few defined outputs for AgCamp and allowed each cohort freedom to define additional outputs. For example, the instructor may have provided a defined output of “Document the entire AgCamp event” for the Marketing and Communication Coordinators and the students in that cohort may have defined additional outputs of “Develop a social media channel” or “Send thank you postcards to our funders.” Students worked within and between cohorts to ensure continual progress toward the required outputs and were given freedom to determine what progress needed to be made, including when and how—i.e., students dictated when their cohort outputs would be graded and the point allocation for each. Throughout the semester, each cohort gave in-class presentations on their progress toward AgCamp and asked for or offered help from/to other cohorts or the instructor.

Lectures were delivered by the instructor throughout the semester that complemented the skills needed to develop AgCamp (e.g., emotional intelligence, teamwork). Reflection was fostered through weekly journals and a written preflection at the beginning of the semester that corresponded with a written reflection at the end of the semester.

Activities on the day of AgCamp and the intended outcomes are outlined in Table 1. While this agenda was adopted across multiple semesters of AgCamp, the lesson or activity may have differed. For example, during one semester, students who delivered the Animal Science demonstration may have led high school students in dissecting fetal pigs while, during another semester, students may have chosen to conduct fecal egg counts with goats. Activities of certain cohorts are not reflected in Table 1 as their outputs were non-student-facing. For example, students in the Marketing and Communications cohort developed fliers to advertise for AgCamp and documented the day-of event while Logistics Coordinators balanced the budget and ordered items for the other cohorts.

To analyze the impact of participating in this service-learning course, we developed and distributed a questionnaire-based survey instrument at the beginning of the semester as a pre-test and at the end of the semester as a post-test. There was a demographics section on the pre-test; a common section related to participants’ perceptions of service-learning and of self on both the pre- and post-test; and a section related to engagement in the service-learning course relative to traditional, lecture-based courses on the post-test. Non-demographics sections were scored on a 5-point Likert-scale where 1 = Strongly agree, 3 = Neutral, and 5 = Strongly disagree.

Prior to distribution, a panel of content area experts (n = 11) were consulted to establish face, construct, and criterion validity of the survey instruments. These experts were faculty with survey development and/or service-learning research expertise. The instrument was revised until approved by the entire panel.

The surveys were distributed to college students enrolled in Leadership Development in Agricultural Sciences in the fall 2021, spring 2022, and fall 2022 semesters. Each of these were “long” semesters comprised of 15 weeks of instruction with AgCamp falling around week 13. Fall 2021 was the “pilot” semester to establish instrument reliability for the target population (n = 42). Cronbach’s alpha for the survey instruments was α = 0.77, which was interpreted as acceptable reliability (George and Mallery, 2003). The final dataset included data from the spring and fall of 2022, but not the pilot (fall 2021), semesters. Data were analyzed with SPSS 26.0 using paired sample t-tests and measures of central tendency with significance at α = 0.05.

We received 79 responses to our pre-test and 81 responses to our post-test. Data were cleaned for participants who provided consent, completed both the pre- and post-tests, and answered at least 75% of survey questions; those who did not meet these criteria (n = 5) were removed from the dataset for a final convenience sample of 74.

Participants were 71.1% female, 25.0% male, 3.5% non-binary; and were White or Caucasian (42.1%), Hispanic or Latino (38.2%), Black or African American (9.2%), Asian (7.9%) and other or not listed (2.6%). Level of study was college freshmen (9.2%), sophomores (34.2%), juniors (46.1%), and seniors (10.5%).

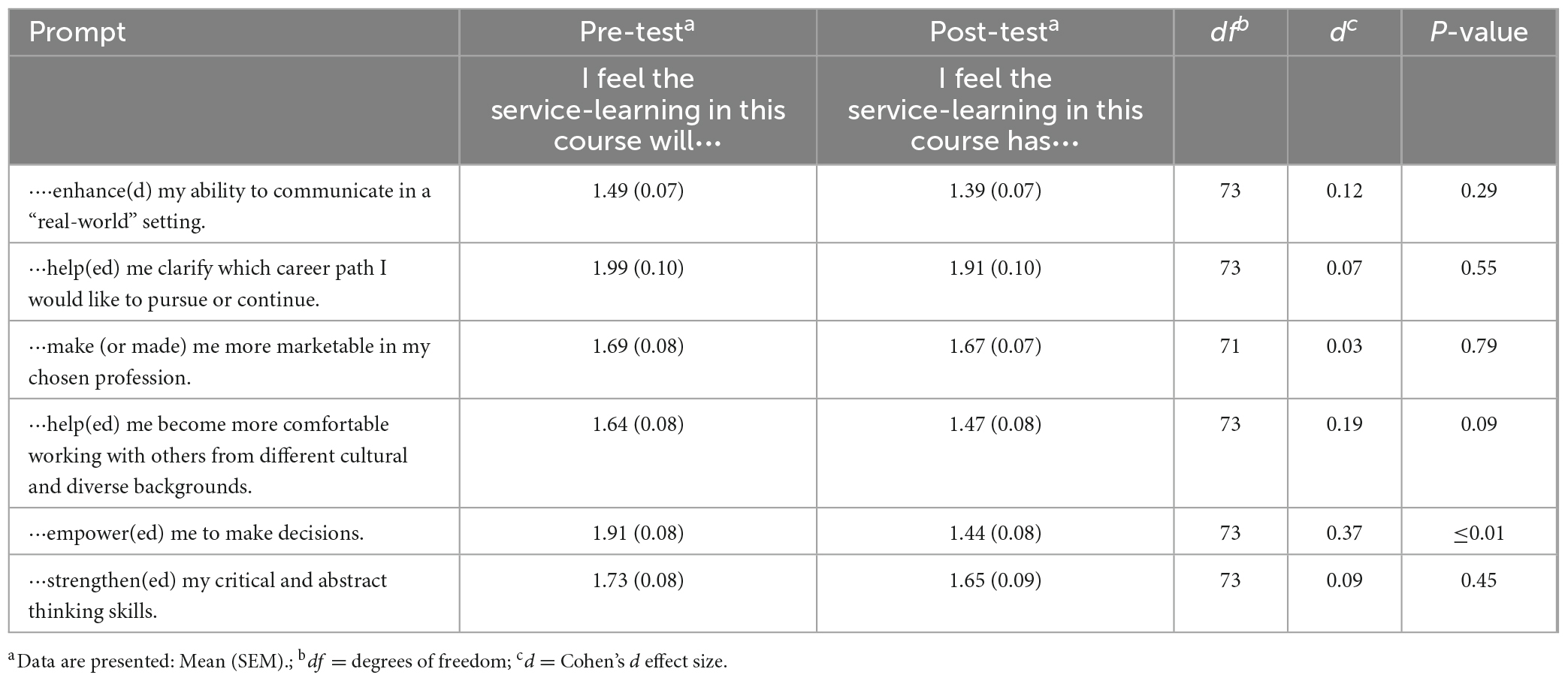

On the pre-test, which was administered at the beginning of the semester, participants perceived the service-learning they would participate in during the course would enhance their ability to communicate in a real-world setting, clarify the career path they would like to pursue or continue, make them more marketable in their chosen profession, and strengthen their critical and abstract thinking skills (Table 2). Pre-test means ranged from 1.49 to 1.99 and, although there were numerical improvements for the linked questions on the post-test administered at the end of the semester (means ranging from 1.39 to 1.91), differences from the pre- to post-test were not significant (P ≥ 0.29).

Table 2. Change in college students’ (n = 74) perceptions of the benefit of service-learning for their personal and professional development.

There was a trend (P = 0.09) for a change in participants’ perceived ability of service-learning to make them more comfortable working with others from different cultural and diverse backgrounds, from a pre-test mean of 1.64 (SEM = 0.08) to a post-test mean of 1.47 (SEM = 0.08) (Table 2). Further, while student participants perceived service-learning would empower them to make decisions at the beginning of the semester, with a pre-test mean of 1.91 (SEM = 0.08), there was a significant improvement (P ≤ 0.01) for their post-test responses (1.44, SEM = 0.08) at the end of the semester.

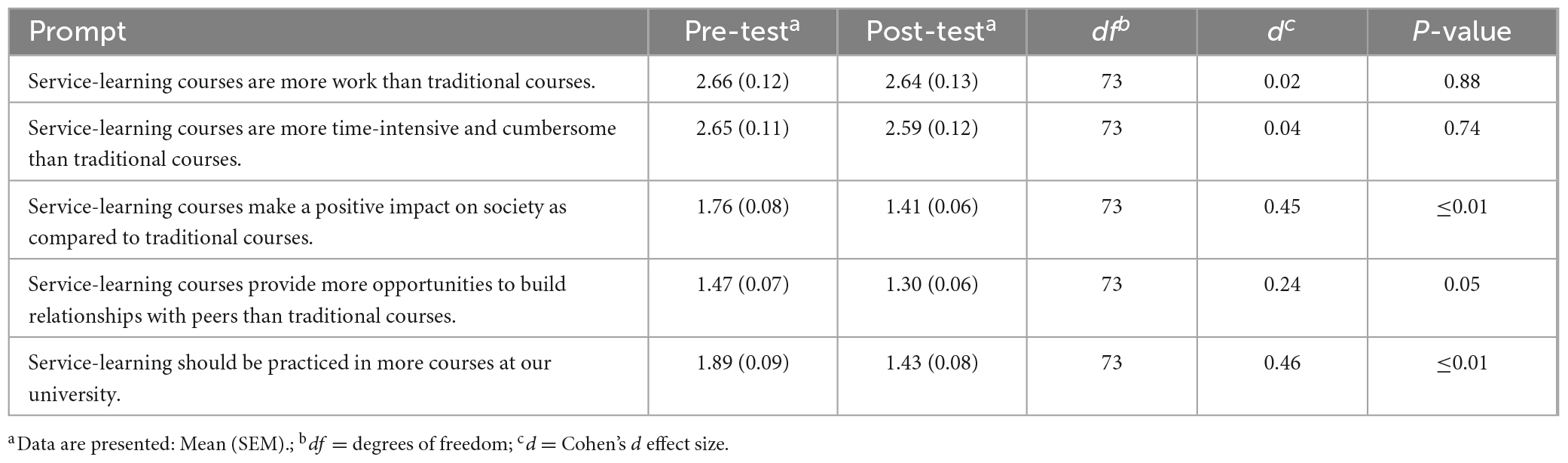

College students were asked about their perceptions of service-learning courses versus traditional, lecture-based courses at the beginning and at the end of the semester. For the pre-test, their perceptions of service-learning courses being more work than traditional courses were fairly neutral, with a pre-test mean of 2.66 (SEM = 0.12), and for service-learning courses being more time-intensive and cumbersome, with a pre-test mean of 2.65 (SEM = 0.11) (Table 3). There was not a significant shift from the pre- to the post-test (P ≥ 0.74), with a post-test mean of 2.64 (SEM = 0.13) for service-learning courses being more work and 2.59 (SEM = 0.12) for service-learning courses being more time-intensive and cumbersome than traditional courses.

Table 3. Change in college students’ (n = 74) perceptions of service-learning versus traditional courses.

At the beginning of the semester, the participants perceived the service-learning they would perform would positively impact society more than their traditional courses, with a pre-test mean of 1.76 (SEM = 0.08) (Table 3). Post-test responses indicate that, after performing the service-learning, perceptions of the societal benefits of service-learning significantly increased (P = 0.01) to 1.41 (SEM = 0.06). Further, when entering the course, participants perceived service-learning would provide more opportunities to build relationships with their peers, with a pre-test mean of 1.76 (SEM = 0.08). There was a significant increase (P = 0.05) from the pre- to post-test, with a post-test mean of 1.30 (SEM = 0.06). There was also a significant improvement (P ≤ 0.01) in the response to “Service-learning should be practiced in more courses at our university,” from a pre-test mean of 1.89 (SEM = 0.09) to a post-test mean of 1.43 (SEM = 0.08).

Participants were asked if they believed they could make a difference in the world. Their responses significantly increased (P = 0.04) from the beginning to the end of the semester, from a pre-test mean of 1.93 (SEM = 0.09) to a post-test mean of 1.66 (SEM = 0.08) (Table 4). At the beginning of the semester, college students responded to the prompt “I believe I have strong leadership skills” with weak agreement and fair neutrality, for a pre-test mean of 2.35 (SEM = 0.08). After performing service-learning, the perception of oneself as a leader significantly increased (P ≤ 0.01) to a post-test mean of 1.53 (SEM = 0.07). On the pre-test, participants reported that they believed it was important to find a career that is beneficial to society (1.49, SEM = 0.07) with no change (P = 0.18) on the post-test (1.37, SEM = 0.07).

The post-test included questions to gauge college students’ experience in the service-learning course as compared to traditional courses; these questions were not linked to pre-test questions. Participants agreed that, compared to traditional courses, they had a voice in classroom discussions (1.72, SEM = 0.76), what they learned in the course would be valuable for their future (1.59, SEM = 0.09), they developed a greater sense of responsibility (1.59, SEM = 0.09), and they developed a sense of purpose of direction in life (2.08, SEM = 0.11).

Our objective was to evaluate if participating in a service-learning course changed undergraduate students’ perceptions of their ability to collaborate and lead, in addition to their overall perceptions of the usefulness of service-learning. Undergraduates developed and hosted a one-day workshop, AgCamp, for high school students over one semester while enrolled in a credit-bearing 3000-level course, Leadership in Agricultural Sciences. Complementary pre- and post-tests were administered at the beginning and end of the semester to evaluate the change in the college students’ perceptions and compare their self-reported experiences in the service-learning course versus traditional, lecture-based courses.

Student perceptions of the value of service-learning were high entering the semester as pre-test means for how service-learning could positively impact the students’ own personal and professional development were in the “Strongly agree” to “Agree” range. However, after developing and executing AgCamp, students felt they got more value out of the course than expected. This is evident as numerically improved means for each item on the post-test with a statistical improvement in comfort working with people from different cultures or backgrounds and for empowerment in decision-making.

Students entered the semester with strong value for service-learning courses. They did not perceive service-learning courses to be more work or require more time than their traditional courses, which contrasts with findings from recent literature. Xavier and Jones (2021) reported that, of their 80 Master’s level students, mean scores for the pre-service-learning survey indicated that students thought it moderately likely they would have less time to work on their other schoolwork, have less free time, and less time to spend with their families because of the service-learning course. Colvin (2020) also noted that approximately half of undergraduate students enrolled in a service-learning course felt strongly about the perceived workload and time consumption of the service-learning project. Differences between our findings and the findings of other studies could be related to student classification (i.e., undergraduate versus graduate), field of study, or previous volunteer experiences as seen in Xavier and Jones (2021).

Institutions that want to implement service-learning programs or courses may benefit from conducting a needs assessment with students in particular departments, degree plans, and grade levels, about their perceptions of service-learning and volunteer work prior to creating a program. This could help institutions uncover preconceived notions that are positive—as is the case in our study—which can be utilized for recruitment and curriculum building to increase enrollment. Potential negative preconceptions may also be uncovered that institutions can proactively assuage during recruitment and advertising for the course to assist with enrollment.

College students in our study believed service-learning courses have greater societal benefits than traditional courses and felt that service-learning should be practiced in more courses at their university, which had strong agreement on the pre-test but even stronger support on the post-test. Specifically, our participants noted that the program was beneficial for developing leadership skills, building connections, and making an impact on society. Further, although we did not observe statistically significant changes, pre- and post-test means demonstrate that students strongly agreed that service-learning would benefit their ability to engage in the real world and communicate with people different from themselves. Perhaps an underlying reason for this was that students strongly agreed that service-learning courses provide more opportunities to build relationships with their peers than traditional courses, which allowed more space for deeper personal engagement with new people. Similar results were observed in Colvin (2020), Keles and Altinok (2020), and Xavier and Jones (2021). Cumulatively, this indicates that service-learning is effective for cultivating soft skills needed to navigate in the real world by giving students the space to practice communicating with a variety of people in a multitude of contexts. This is critical as the world becomes more complex and multicultural and could be attractive for students who wish to enroll in courses that will grant them life skills in addition to practicing course content.

Participation in the service-learning course seems to have been empowering as the college students felt more strongly that they could make a difference in the world and that they have strong leadership skills on the post-test. However, the course was “Leadership Development in Agricultural Sciences” and, thus, lectures and discussions centered around leadership. We cannot determine if participation in the service-learning project or simply being in a classroom discussing topics about leadership explain our findings. The service-learning project provided an opportunity to take declarative knowledge from the course and turn it into procedural knowledge, so a potential combined effect may also be observed here.

On the post-test, students strongly agreed that they had a voice in course discussions, the course content was valuable for their future, and they developed a greater sense of responsibility in the course as compared to traditional courses. This indicates students pursuing science-based degrees understand the value of soft skills, also known as employability skills, in their careers and lives, and received them through the service-learning project described here. Soft skills are highly desired by employers and most employers are more likely to consider a job candidate who has participated in a variety of activities (e.g., senior projects or a project in a diverse community setting with individuals from different backgrounds) (Association of American Colleges and Universities [AACU], 2015). Initiatives such as AgCamp are critically important to prepare graduates to be competitive in the job market.

Research limitations are lack of follow-up after the semester of enrollment in the service-learning course. More specifically, it would be interesting to determine if positive benefits noted on the post-test persisted long-term, if students were more inclined to enroll in more service-learning courses, or if students sought a civic service career or hobby. Future research should analyze these long-term outcomes of service-learning.

Our data demonstrate that undergraduate students have positive perceptions of service-learning and value these courses for their professional development. These findings have theoretical implications for higher education as they indicate that service-learning can be an effective pedagogy to enhance soft-skill development in undergraduates, creating more well-rounded graduates. The positive views expressed by participants suggest that integrating academic coursework with civic engagement aligns well with learning theories, including experiential learning and social constructivism. Further research exploring the underlying mechanisms by which service-learning fosters skill acquisition and professional or personal development would contribute to refining these theoretical frameworks. Practically, our findings directly impact educators and institutions of higher education aiming to integrate high-impact practices into their pedagogy to enhance the educational experiences of undergraduates. As participants in our study expressed a willingness for more service-learning offerings, there is an opportunity to meet this demand while also providing students with real-world applications of their knowledge and establishing partnerships with community organizations to facilitate mutually beneficial service-learning opportunities. Future research should evaluate the effectiveness of service-learning in different academic disciplines and cultural contexts. Further, longitudinal tracking of participants’ skill acquisition, competencies, and career trajectories would give further insight into the long-term value of service-learning experiences. Continued exploration and refinement of service-learning practices will contribute to the ongoing evolution of higher education, fostering the holistic development of students in preparation for their roles as engaged and socially responsible citizens.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Texas State University Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

MD: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. JL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding was received by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Hispanic Service Institutions (HSI) Education Grants program, award number 1002337. The funder provided funds used to purchase materials and supplies for the service-learning project described here.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Anderson, K., Boyd, M., Ariemma Marin, K., and McNamara, K. (2019). Reimagining service-learning: Deepening the impact of this high-impact practice. J. Exp. Edu. 42, 229–248. doi: 10.1177/1053825919837735

Association of American Colleges and Universities [AACU] (2015). Falling short? College learning and career success. Washington, DC: Hart Research Associates.

Bastida-Escamilla, E., Elias-Espinosa, M., and Franco-Herrera, F. (2022). “Service-learning as a bridge to connect theory and practice: A case study,” in Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, Piscataway, NY.

Battistoni, R. (2013). “Civic learning through service learning,” in Research on service-learning: Conceptual frameworks and assessment. Volume 2A: Students and faculty, eds P. Clayton, R. Bringle, and J. Hatcher (Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing), 111–132.

Bowie, A., and Cassim, F. (2016). Linking classroom and community: A theoretical alignment of service learning and a human-centered design methodology in contemporary communication design education. Edu. Change 1, 1–23. doi: 10.17159/1947-9417/2016/556

Bringle, R., and Hatcher, J. A. (1995). A service-learning curriculum for faculty. Michigan J. Comm. Serv. Learn. 2, 112–122.

Celio, I., Durlak, J., and Dymnicki, A. (2011). A meta-analysis of the impact of service-learning on students. J. Exp. Edu. 34, 164–181.

Charity Hudley, A., Dickter, C., and Franz, H. (2017). The indispensable guide to undergraduate research: Success in and beyond college. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Colvin, J. (2020). Perceptions of service-learning: Experiences in the community. Int. J. Res. Serv-Learn. Comm. Engage 8:10. doi: 10.37333/001c.18783

Currie-Mueller, J., and Littlefield, R. (2018). Embracing service learning opportunities: Student perceptions of service learning as an aid to effectively learn course material. J. Scholar Teach. Learn. 18, 25–42. doi: 10.14434/josotl.v18i1.21356

Detgen, A., Fernandez, F., McMahon, A., Johnson, L., and Dailey, C. (2021). Efficacy of a College and Career Readiness Program: Bridge to Employment. Career Dev. Q. 69, 231–247. doi: 10.1002/cdq.12270

Eppler, A., Ironsmith, M., Dingle, S., and Errickson, M. (2011). Benefits of service-learning for freshman college students and elementary school children. J. Scholar Teach. Learn. 11, 102–115.

Fullerton, A., Reitenauer, V., and Kerrigan, S. (2015). A grateful recollecting: A qualitative study of the long-term impact of service-learning on graduates. J. High. Edu. Outreach Engage 19, 65–92.

George, D., and Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference. 11.0 update. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Gerholz, K., Liszt, V., and Klingsieck, K. (2017). Effects of learning design patterns in service learning courses. Active Learn. High. Edu. 19, 47–59.

Gupta, K., Grove, B., and Mann, G. (2011). Impact of service learning on personal, social, and academic development on community nutrition students. J. Comm. Engage High. Edu. 13, 1–16.

Hart, S. (2015). Engaging the learner: The ABC’s of service–learning. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 10, 76–79. doi: 10.1016/j.teln.2015.01.001

Hooker, S., and Brand, B. (2010). College knowledge: A critical component of college and Career Readiness. New Dir. Youth Dev. 127, 75–85. doi: 10.1002/yd.364

Jean-Philippe, S., Richards, J., Gwinn, K., and Beyl, C. (2017). Urban youth perceptions of agriculture. J. Youth Dev. 12, 1–17. doi: 10.5195/jyd.2017.497

Keles, H., and Altinok, A. (2020). The impact of service learning approach on students’ perception of good citizenship. Int. J. Eurasia Soc. Sci. 39, 23–52. doi: 10.35826/ijoess.2596

Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Kuh, G. (2008). High-impact educational practices: What they are, who has access to them, and why they matter. Washington, DC: Association of American College and Universities.

Luckey, A., Murphey, T., Cummins, R., and Edwards, M. (2013). Assessing youth perceptions and knowledge of agriculture: The impact of participating in an AgVenture program. J. Ext. 51:30. doi: 10.34068/joe.51.03.30

Matthews, C., and Zimmerman, B. (2009). Integrating service learning and technical communication: Benefits and challenges. Tech Comm. Quart. 8, 383–404. doi: 10.1080/10572259909364676

Narong, D., and Hallinger, P. (2023). A keyword co-occurrence analysis of research on service learning: Conceptual foci and emerging research trends. Edu. Sci. 13, 339–363. doi: 10.3390/educsci13040339

Ongang’a, P., Ochola, W., Odhiambo, J., and Basweti, E. (2020). Improving knowledge gain in secondary School Agricultural Education through supervised agricultural experience programme (SAEP) in Migori County, Kenya. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2, 6–18. doi: 10.37284/ijar.2.2.230

Rutti, R., LaBonte, J., Helms, M., Hervani, A., and Sarkarat, S. (2016). The service learning projects: Stakeholder benefits and potential class topics. Educ. Train 58, 422–438. doi: 10.1108/ET-06-2015-0050

Salam, M., Awang Iskandar, D., Ibrahim, D., and Shoaib Farooq, M. (2019). Service learning in higher education: a systematic literature review. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 20, 573–593. doi: 10.1007/s12564-019-09580-6

Salam, M., Iskandar, D., and Ibrahim, D. (2017). Service learning support for academic learning and skills development. J. Telecomm. Elec. Comp. Engr. 9, 111–117.

Sass, M., and Coll, K. (2015). The effect of service learning on community college students. Comm. Coll. J. Res. Prac. 39, 280–288. doi: 10.1080/10668926.2012.756838

Swanson, E., Kopotic, K., Zamarro, G., Mills, J., Greene, J., and Ritter, G. (2021). An evaluation of the educational impact of college campus visits: A randomized experiment. Am. Educ. Res. J. 7, 1–18. doi: 10.1177/2332858421989707

Turk, J., and Pearl, A. (2021). Improving developmental learning outcomes in community colleges through service-learning. New Dir. Comm. Coll. 195, 91–106. doi: 10.1002/cc.20469

Wahlström, N. (2022). School and democratic hope: The school as a space for civic literacy. Eur. Edu. Res. J. 21:994. doi: 10.1177/14749041221086721

Williams, C. (2022). Student perceptions of open pedagogy and community-engaged service learning. IntechOpen doi: 10.5772/intechopen.107099 [Epub ahead of print].

Xavier, N., and Jones, P. (2021). Students’ perceptions of the barriers to and benefits from service-learning. J. High Edu. Theory Prac. 21:4514. doi: 10.33423/jhetp.v21i8.4514

Keywords: service-learning, college students, higher education, high-impact practices, experiential learning, post-secondary education, professional development

Citation: Drewery ML and Lollar J (2024) Undergraduates’ perceptions of the value of service-learning. Front. Educ. 9:1330456. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1330456

Received: 30 October 2023; Accepted: 08 January 2024;

Published: 25 January 2024.

Edited by:

Wang-Kin Chiu, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, ChinaReviewed by:

Buratin Khampirat, Suranaree University of Technology, ThailandCopyright © 2024 Drewery and Lollar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Merritt L. Drewery, TV9kNTUzQHR4c3RhdGUuZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.