- Li Ka Shing School of Professional and Continuing Education, Hong Kong Metropolitan University, Hong Kong, China

Background: Despite promising emerging evidence on the protective properties and interrelationships of posttraumatic growth, career adaptability and psychological flexibility, no studies have reported interventions that promote these positive personal resources among higher education students. Nurturing these positive personal resources in future interventions is recommended to holistically address students’ developmental, academic and career-related challenges associated with major transitions. This paper describes (a) the rationale for and development of a tailored growth-based career construction psychosocial intervention, ‘Sailing through Life and My Career Path’ (SLCP) for higher education students; and (b) a mixed-method non-randomised pre-post study to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed psychosocial intervention in achieving positive participant outcomes.

Methods and analysis: Over a 12-week period, higher education students will be recruited to take part in group and independent learning activities that are tailored to nurture positive personal resources to overcome challenges related to developmental, academic and career-related transitions. Quantitative data will be collected before and after the intervention and will be analysed using SPSS v26. Follow-up semi-structured interviews with participants (students), interventionists (group facilitators), and administrators will be conducted to explore perceptions of the intervention, to understand its process of change, and to determine its feasibility and acceptability in the higher education setting. All interviews will be transcribed and analysed using thematic analysis.

Discussion: By filling in a gap in existing intervention research and practice, the proposed study serves to generate new knowledge and insights by evaluating the effectiveness of a tailored psychosocial intervention that responds to the complex needs associated with major life transitions of higher education students.

1 Introduction

1.1 Transitions into, during and beyond higher education

Life transitions involve significant changes in one’s physical, social, and/or economic environments that often require them to make adjustments in their roles, responsibilities, and routines. Described as a distinct period of profound change and importance, emerging adults (aged 18–25) constantly explore academic, social and career possibilities that suit their interests, values, personality traits, strengths and worldviews, gradually moving towards enduring choices and decisions (Arnett, 2000).

Although gaining entry to college or university offers students opportunities for personal and professional growth and development, the transition from high school to higher education can be a highly psychologically demanding experience that has been described as a ‘mental health crisis’ (Kadison and DiGeronimo, 2004), with heightened psychological distress levels that some students may not rebound from (Bewick et al., 2008; Conley et al., 2020). The transition has also been described as a ‘loss experience’ (van Herpen et al., 2020), where students undergo identity changes and significant adjustment in personal, social, academic, and finanical responsibilities (Christiaens et al., 2021), with previous studies having reported academic underperformance and increased dropout rates (Pascoe et al., 2020), and mental-health related issues and lower levels of wellbeing (Bruffaerts et al., 2018; Choi, 2018). The higher education experience itself has been described as a risk factor associated with suicide in this student population (Lageborn et al., 2017).

Whether going into employment or further study, transitions continue after graduation as students navigate a new identity beyond their prior university life (Grosemans et al., 2020). The experience of transition from student to employee involves the navigation of new identities which is psychologically demanding, irrespective of existing mental health conditions (Cage et al., 2021). Transitions continue to occur during one’s career, with individuals undergoing several career-related transitions throughout their lives, whether planned or unplanned (Masdonati et al., 2022). Life transitions are thus lifelong, impacting both personal and professional development.

1.2 The paradox of the impact of lifetime trauma

As higher education students face a variety of transition-related stress, research indicates that having a history of traumatic life event is common in this student population, estimating the prevalence to range between 67 and 84% (Read et al., 2011). also Having a history of traumatic life events was a significant risk factor for a number of mental health issues among higher education students, most notably, increased anxiety and depression (Cámara and Calvete, 2021), posttraumatic disorder symptoms (Read et al., 2011), and suicidal ideation (Macalli et al., 2020). Trauma has been shown to be adversely associated with one’s educational and employment outcomes (Hardcastle et al., 2018), such as negative thoughts and beliefs about one’s career outcomes (Chronister et al., 2012), risk of burnout (Mather et al., 2014), developmental work personality and vocational identity (Strauser et al., 2006; Zeligman et al., 2020), and overall life opportunities (Metzler et al., 2017).

Although traumatic experiences are commonly linked to poor psychological outcomes, or even irreversible functional damage, considerable studies suggest symptom severity and duration vary significantly among respondents from minimal or no adverse effects to brief or chronic symptomatology (Kessler et al., 2005; Breslau, 2009). Such inconsistent findings have generated growing research efforts to examine resilience after trauma, nevertheless, most research on resilience has focused on returning to baseline functioning and preserving mental health after a traumatic experience (Bos et al., 2016). More recently, the possibility of transformative positive changes, beyond mere recovery, namely, posttraumatic growth (PTG; Tedeschi and Calhoun, 1995, 1996, 2004), following psychological trauma has attracted considerable attention. Similar to other concepts within positive psychology such as hope, optimism, and gratitude, PTG has been recognised as a buffer for the detrimental effects of life adversities (Nik Jaafar et al., 2022; Confino et al., 2023).

PTG is a multidimensional concept that has been widely used to describe the subjective experience of transformative psychological change resulting from the struggle with a highly challenging experience that overwhelms one’s coping resources and contradicts one’s worldview (Tedeschi and Calhoun, 1995, 1996, 2004). PTG is generally understood to be manifested in five major domains – (1) greater appreciation of life with changed philosophies and priorities, (2) greater awareness and utilisation of personal strengths, (3) strengthening of close relationships, (4) openness to new possibilities, and (5) a deeper spiritual and existential sense. The rates of positive changes following life crises typically outnumber reports of psychiatric disorders, ranging from 29.0 to 97.6% (Linley and Joseph, 2004). Since the introduction of the PTG concept, previous studies have consistently shown that the phenomenon has been experienced by higher education students worldwide (Taku et al., 2007; Brooks et al., 2016; Young and Yujeong, 2018; Oshiro et al., 2023), with one study reporting the rates as 55% (Yanez et al., 2011).

1.3 Posttraumatic growth, career adaptability and psychological flexibility: positive psychological resources

A growing literature has shown that adaptability is a key source of internal resources that is positively linked to psychological wellbeing (Holliman et al., 2021), academic (Holliman et al., 2020) and occupational outcomes (Collie and Martin, 2017), and life satisfaction (Zhou and Lin, 2016). Adaptability is a construct that broadly refers to a personal attribute (a relatively stable, trait-like cluster of characteristics) and a performance construct (cognitive, behavioural and affective adaptation to situations of change) that influence an individual’s ability and willingness to cope with circumstances characterised by novelty and uncertainty (Martin et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2020). Parallels have been drawn between adaptability and a related construct, psychological flexibility (PF), which refers to the extent to which an individual “adapts to fluctuating situational demands, reconfigures mental resources, shifts perspective, and balances competing desires, needs, and life domains” (Kashdan and Rottenberg, 2010, p. 866). Emerging evidence shows that PF is associated with a number of positive outcomes among higher education students such as smooth integration and progression into studies and better academic progress (Asikainen, 2018), greater self-efficacy (Jeffords et al., 2020), less task avoidance (Hailikari et al., 2022), more psychological flow (Abu Asa’d, 2016), weaker negative emotions (Marshall and Brockman, 2016; Uğur et al., 2021), and better relationship quality (Twiselton et al., 2020). Waldeck et al. (2021) conducted a confirmatory factor analysis and found that there was an overlap between adaptability and PF. However, adaptability was found to predict psychological wellbeing, but not a significant predictor of psychological distress after accounting for the effects of PF, suggesting adaptability and PF are related but distinct constructs.

Adaptability has been contextualised to career construction and vocational contexts, and the related concept of career adaptability (CA) has attracted increasing attention from researchers in the last decade (see Johnston, 2018 for the see first qualitative systematic review and Rudolph et al. (2017) for the first quantitative meta-analytic review). The career construction theory (CCT; Savickas, 1997; Savickas, 2005; Savickas and Porfeli, 2012) is a modern approach to career development that provides a holistic framework to understand what, how, and why individuals make sense of their work and life experiences in order to develop a cohesive identity that empowers them to effectively adapt to the changing environment and achieve positive outcomes. Grounded in this approach, CA is a multidimensional psychosocial construct that represents an “individual’s readiness and resources for coping with current and imminent vocational development tasks, occupational transitions, and personal traumas” (Savickas, 2005, p. 51). As a valuable recourse that is not limited to their career development but also all aspects of their lives, CA consists of four dimensions, including concern (preparation and planning for one’s future), control (awareness and behaviour exerted to control one’s future), curiosity (the willingness to explore one’s identity and options), and confidence (self-efficacy to overcome obstacles to pursuing desired goals). Research shows that CA is related to wellbeing (Savickas et al., 2009; Ramos and Lopez, 2018), positive attitude toward the future (Öztemel, 2021), quality of life (Soresi et al., 2012), flourishing (Lodi et al., 2020), and meaning and purpose in life satisfaction (Santilli et al., 2014).

Emerging evidence suggests that PTG, CA and PF may be valuable psychological resources that interact to facilitate positive outcomes for higher education students. A recent study found that adaptability bolstered PTG in higher education students, enabling students to feel actively involved in their own education, and to positively reinterpret novel and unexpected situations (including those that are considered stressful), as opportunities for positive personal growth (Feraco et al., 2022). Although there is limited research that has linked PTG to career development, one study found that PTG moderated the relationship between trauma and CA among university students, suggesting growth after trauma may play an important role that enables individuals to become more adaptive in their careers (Prescod and Zeligman, 2018). The empowering property of CA was also found in a more recent study where CA mediated the relationship between personality traits (openness, neuroticism and conscientiousness) and PTG among adolescents coping with trauma (Salimi et al., 2022). In a recent study that explored the relationship between PF, CA and wellbeing among adults (mean age = 26.43 with 45.58% being students), PF was a significant predictor of CA, and CA mediated the relationship between PF and well-being (Russo et al., 2023). The emerging evidence on the interrelated positive effects of PTG, CA and PF therefore suggests that nurturing these qualities may strengthen higher education students’ capacity to adapt, change, or even thrive, during major life challenges and beyond. Together, the psycho-social–emotional, academic and career-related needs of higher education students are complex and cannot be seperated. While trauma remains to be one of the most common presentation of issues in counselling (Mailloux, 2014), and higher education students have the tendency to discuss mental health issues and career when they seek counselling support (Hinkelman and Luzzo, 2007), the literature in this area is sparse. Career is a lifelong process, and higher education plays a critical role in preparing students for their future careers. As the risk-oriented paradigm is shifting towards a more resilience-oriented perspective, the application of positive psychology, which embraces human strengths and potential, positive aspects of functioning, and the importance of purpose and meaning (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi, 2000), may have a promising role to play in enhancing the welfare and growth of higher education students, and fostering long-term optimal functioning, wellbeing, and flourishing in their future life and career.

1.4 Psychosocial interventions and socioemotional support in higher education

Higher education is a critical life stage where students set the foundation for their future career and life while managing a range of interrelated psycho-social–emotional academic, and career-related challenges that go beyond the study years. Appreciating the unique developmental challenges faced by this student population is an important step to nurture students’ resources holistically that address their complex needs and solidly prepare them for an increasingly unsettled and unpredictable future world. Not long ago, researchers have criticised that there has been less attention paid to the specific needs and issues of higher education students compared to high school students, both locally and globally. As Wong (2011) criticised, there is an ‘abundance of universal adolescent prevention and positive youth development programmes specifically designed for high school students, similar programs are grossly lacking in the university educational context’ (p. 353). Nevertheless, increasingly noticeable efforts have been made by higher institutions worldwide to develop and evaluate interventions and initiatives that address the complex needs of students in recent years (see Worsley et al., 2022, for a systematic review of review-level evidence of interventions). Some examples include strengths-based initiatives and positive education (Lefevor et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2018), psychological interventions (Barnett et al., 2021; Franzoi et al., 2022), interventions that promote social and emotional competencies (Conley, 2015), mental health-related programmes (Conley et al., 2015), social support interventions (Mattanah et al., 2010), career-related interventions (van der Horst et al., 2021; Soares et al., 2022), self-help interventions (Charbonnier et al., 2022), curriculum-embedded interventions (Shek and Sun, 2012; Upsher et al., 2022), assessment design and practice (Chan, 2022), and recreation and extracurricular activities (Finnerty et al., 2021). Collectively, the significant efforts demonstrate the pressing need to respond to the interrelated psycho-social–emotional aspects of personal and professional development of higher education students in the rapidly changing 21st century.

1.5 The current study

To contribute to the growing research base on the value of holistic student learning and support in higher education, this study details a growth-based career-construction psychosocial intervention for higher education students which is underpinned by the conceptual and empirical foundations of the PTG model (Tedeschi and Calhoun, 1995, 1996, 2004) and the Career Construction Theory (Savickas, 1997; Savickas, 2005). To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no studies have reported interventions that promote PTG, CA, and PF as personal resources among higher education students. Kou et al. (2021) conducted a bibliometric analysis on the research trends of PTG from 1996 to 2020 and found only a small number of intervention studies, with cancer and natural disasters being the focus of trauma. For CA, a recent systematic review on studies (k = 26) focusing on career interventions for higher education students revealed that CA was assessed in one study only (Soares et al., 2022). PF has been studied less in higher education than in workplace settings (Asikainen and Katajavuori, 2023). Nevertheless, evidence has emerged that PF can be enhanced through psychotherapy-based group intervention among higher education students (Levin et al., 2016; Katajavuori et al., 2023).

To address limitations of previous research and inform practice, this paper outlines a mixed-methods study that evaluates the effectiveness of the tailored growth-based career construction psychosocial intervention aimed at addressing the developmental, academic and career-related needs associated with major transitions of higher education students. The primary outcomes of the study are PTG, CA, and PF. These variables are considered valuable personal resources with promising potential for preparing higher education students for developmental, academic and career-related challenges related to major life transitions. We hypothesise that the intervention will lead to greater levels of self-reported PTG, CA, and PF in the post-intervention period than those in the pre-intervention period.

2 Methods and design

2.1 Study design and setting

This study uses a mixed methods non-randomised pre-post design to (i) evaluate the effectiveness of the growth-based career construction psychosocial intervention in achieving positive changes in its desired participant outcomes (ii) understand the process of change during the intervention (iii) determine the feasibility and acceptability of implementing the proposed intervention in the higher education setting. Participants will be full-time students at an urban community college in Hong Kong. An opportunity sample of students who sign up to take part in the proposed intervention, ‘Sailing through Life and My Career Path’, will be recruited. A priori sample size calculation indicated that 90 participants are required to detect an effect size of 0.3, using an α of 0.05, single group with 80% power (Kadam and Bhalerao, 2010). Thus, 100 participants will be recruited to participant in the proposed intervention study.

2.2 Participant recruitment and eligibility

Participants will be recruited via either classroom promotion or the use of recruitment materials such as flyers sent to all students’ e-mail via the Student Affairs Office. To be eligible to participate, students will need to (i) be aged 17 years or above, (ii) be a current full-time higher diploma student, (iii) have registered for the SLCP intervention, and (iv) be proficient in English language. Individuals who consider themselves to be in a psychologically unstable state (i.e., currently receiving psychological treatment) will be excluded.

Participant Information Sheet will be given to all students who choose to take part in the SLCP intervention as an invitation to participate in this research. They are allowed at least 24 h to consider whether to take part in the present study. Participation will be entirely voluntary. For students who do not wish to take part in the study, they have the right to decline research participation. Such an agreement is incorporated into the Participant Consent Form for students who are 18 years or above, or Parental Consent Form for those who are aged 17. Most importantly, those students will still be eligible to complete the SLCP intervention even if they do not choose to participate in this study.

2.3 The intervention

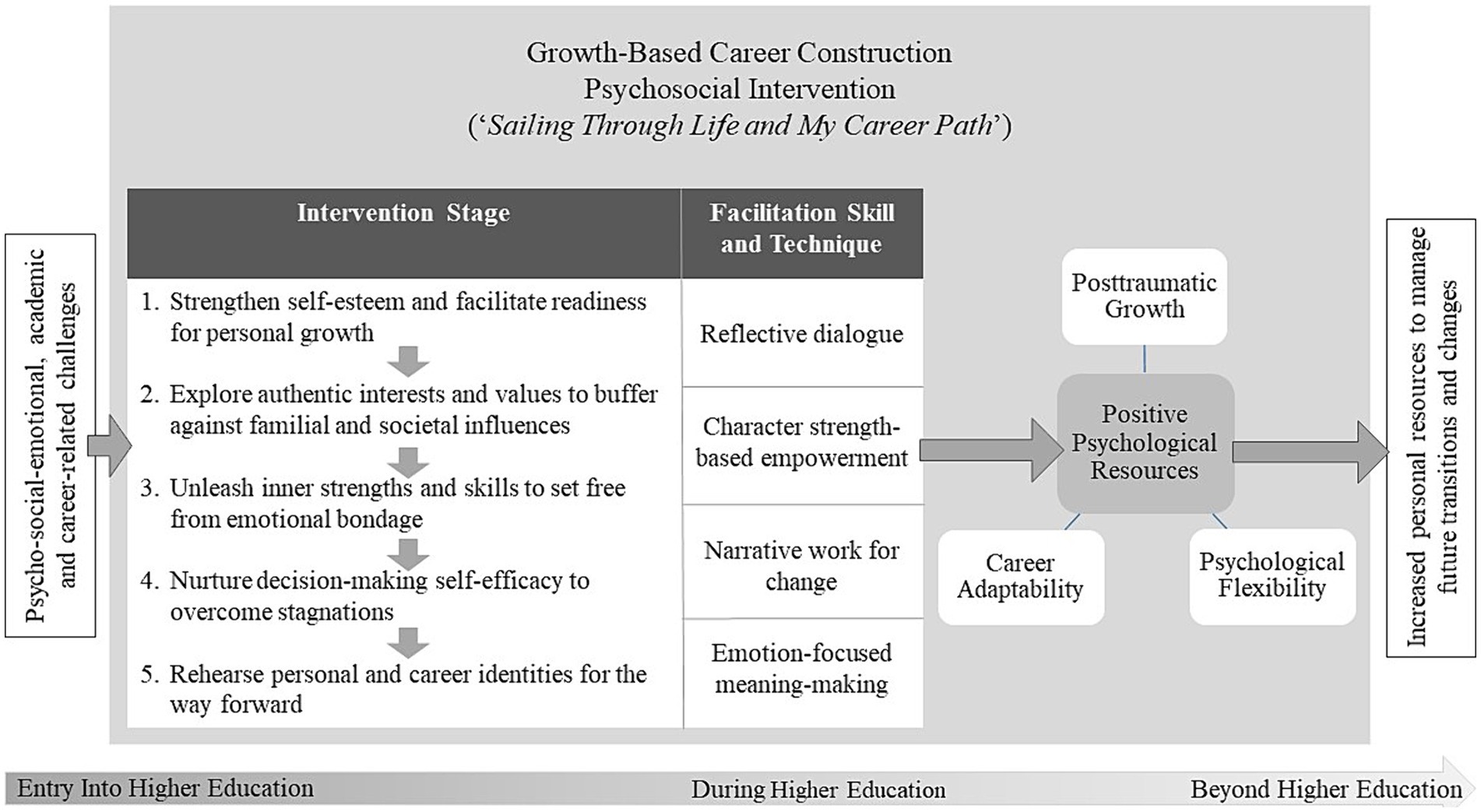

The content of the intervention protocol is developed based on the theoretical and empirical underpinnings of the PTG model (Tedeschi and Calhoun, 1995, 1996, 2004) and the Career Construction Theory (Savickas, 1997; Savickas, 2005), incorporating their respective evidence-based intervention activities, i.e., the Posttraumatic Growth Workbook (Tedeschi and Moore, 2016) and My Career Story Workbook (Savickas and Hartung, 2012). Theories and research evidence that have contextualised their applications in overcoming major challenges in life and career transitions will also be used. The finalised protocol covers five consecutive intervention stages and are explicitly designed and formulated to increase participants’ positive personal resources, i.e., PTG, CA, and PF. A set of skills and techniques are recommended to create a nurturing learning atmosphere and to guide and facilitate group processes effectively throughout the intervention. Figure 1 shows the framework and process of the proposed growth-based career construction psychosocial intervention.

2.3.1 Stage 1: strengthen self-esteem and facilitate readiness for personal growth

The sequence of an individual’s adaptation starts with his/her adaptive readiness, “flexibility of willingness to change” (Savickas and Porfeli, 2012, p. 662). By signing up for the intervention, it indicates participates are willing to change. To maximise their adaptation outcomes, they will be first guided to identify their individual barriers to successful life transitions and identify how the intervention may prepare them for positive coping of transitions and optimal self-development. Based on self-directed learning theory, this initial reflective process will help participants gain control and autonomy in the intervention activities and increase their intrinsic motivation to work towards their personalised choices and goals (Knowles, 1975; Geng et al., 2019).

2.3.2 Stage 2: explore authentic interests and values to buffer against familial and societal influences

Self-understanding has been evident as a crucial predictor of resilience (Beardslee, 1989). In face of external demands during life transitions, when participants can translate a normative or prescriptive life task to an individual action that is personally meaningful, they would find the goal more rewarding to work on, although not altogether easy to solve (Cantor et al., 1987). Hence, the current intervention will enhance participants’ awareness on their personal goals, interests, and most importantly, their cognitive appraisal of underlying values and meanings (Savickas and Hartung, 2012). Participants will also be guided to explore the influences of familial influence, market pressures, and societal expectations (Savickas et al., 2009), and to reexplore their goals based on enhanced understanding and ownership of personal strengths, needs, and wants. They are believed to be more independent and less likely to please others when they reformulate their goals. Such regulation process of increasing students’ career concern, control, curiosity, and confidence also lies at the foundation of psycho-socioemotional development in higher education.

2.3.3 Stage 3: unleash inner strengths and skills to set free from emotional bondage

Apart from one’s cognitive appraisal, emotional reactions to traumatic events are also considered a barrier to successful transitions (London, 1997). The heightened negative feelings (despair, anxiety, fear, lack of security) about the world and one’s own future often acts as an emotional bondage that interrupts their interpretation processes (internal maps) and so affects their academic and career choices (Bulut and Sülük, 2021). Ironically, when these emotions are externalised, reorganised in a state of “psychological disequilibrium,” and restructured to reach new synthesis of meanings (Mahoney, 1982), the individuals can achieve PTG (Tedeschi and Calhoun, 1995). The current intervention, therefore, will accompany participants to go through such change processing, and most importantly, to recognise the role of their strengths (e.g., character strengths) in setting themselves free from the emotional bondage (Tedeschi and Moore, 2016). When this occurs, it provides a basis for an individual’s new understanding of the personal strengths and perceived self-efficacy that serves as a springboard for self-actualisation, self-compassion, and hope (Jerusalem and Mittag, 1995).

2.3.4 Stage 4: nurturing decision-making self-efficacy to overcome stagnations

Participants’ general belief of self-efficacy during transitions will be further reinforced to target at academic or career-related stagnations. Reasons for the stagnations can be manifold (Abele et al., 2012). A major individual factor is a person’s lack of career decision self-efficacy, “degree of belief that he or she can successfully complete tasks necessary to making career decisions” (Betz et al., 1996, p. 46), which results in indecisions and dilemmas that reduce his or her security, satisfaction, and quality of life. To nurture participants’ confidence in capabilities and motivation to overcome their stagnations, the current intervention will guide participants to explore their decision-making strategies (e.g., rational, intuitive, dependent) (Argyropoulou and Kaliris, 2018) and their relations to self-concepts, goals and career choices. They will also construct successful stories of how they have used their strategies to solve previous life and career tasks (Savickas, 2005). After the contemplative discussion, participants will not only develop their career decision-making adaptability, but also begin to construct their identity, i.e., a personal narrative of who they are (Newark, 2014). Becoming an identity-bound decision maker (March, 1994) will help them endure and feel confident and content to cope with future transitions and uncertainties with integrity.

2.3.5 Stage 5: rehearse personal and career identities for the way forward

The final intervention stage will facilitate participants to weave together disparate life stories unfolding their internal resources (i.e., self-concepts, unique strengths, PTG, and CA) into broader life themes, and use them to construct their personal and career identities. According to Alvesson (2010), this identity work allows participants to metaphorically understand their holistic values and motivation and produces a sense of coherence and distinctiveness. Doing so, participants will build their own “compass” (Fugate et al., 2004) or “career anchor” (Schein, 1978) which helps navigate themselves through uncertainties in the increasingly protean and boundaryless career environment (Arthur and Rousseau, 2001; Hall, 2004), yet still stay true to a sense of self. Additionally, participants will be introduced the future time perspective in career development (Husman and Shell, 2008). By forming a mental representation of their future, as well as having a better understanding of how their current behaviour serves a direct role in attaining future goals, the participants will be more inspired and confident to take the necessary steps to achieve their desired life and career outcomes (Savickas and Lent, 1994).

Taken together, the five-stage intervention process focuses on increasing participants’ connection with their inner world (e.g., self-concepts, strengths, interests and goals), in addition to the external world (e.g., others’ influences and expectations, career opportunities and limitations). Through this emerging connection, they begin to think beyond their past life stories and to adapt to the continuously changing developmental path using their PTG and CA. The ultimate desired goal of the entire process is to nurture participants’ PTG, CA, and PF, enabling them to take self-motivated, task-focused, and sustained actions towards future success.

2.4 Facilitation skills and techniques

To promote the expected process of change in the proposed intervention stages, the following facilitation skills and techniques are incorporated in the implementation of intervention activities:

2.4.1 Technique 1: reflective dialogue

Reflection has been seen as a crucial cognitive practice that enables individuals to turn back onto the self, to actively observe and to be observed (Steier, 1995), and to gain an awake stance about their lived experience (Mortari, 2015). Specifically, reflectivity regarding life and career tasks allows the individuals to explore their identity aspects in the past, the present and the future. By doing so, they can identify authentic aspects and make life and career choices by clarity (Di Fabio et al., 2019). Reflectivity, hence, is increasingly recognised as a good predictor of students’ career adaptability (Ran et al., 2023). Viewing this, several of our intervention strategies will engage participants in reflective dialogues to uncover their authenticity and aspirations. Examples of these strategies include Socratic questioning, structured and scaffolded journal writing, and reflective career dialogue (Ryan and Ryan, 2013; Meijers and Lengelle, 2016).

2.4.2 Technique 2: character strength-based empowerment

Character strengths is referred to as positive virtues for thinking, feeling, and behaving (Park et al., 2006). According to Peterson and Seligman (2004), they compose personality and identity. Everyone has a unique combination or constellation of strengths, creating a sense of who we are. Notably, character strengths also have a buffering role in adversity and suffering (Niemiec, 2020) and predict resilience, self-efficacy, and optimism (Martínez-Martí and Ruch, 2016). They also help individuals to make more meaningful career decisions (Luthans et al., 2007). To achieve this, facilitators will first help participants increase awareness on personal strengths they were previously unaware of, and then explore and grow them toward positive action, i.e., by applying their character strengths to overcome challenges and achieve their personal and career goals. Facilitators themselves will also embody and exhibit their own character strengths as they interact with participants. Overall, the process is empowering, energising, and connecting (Niemiec and Pearce, 2021), and provides a supportive vibe to cultivate change among participants.

2.4.3 Technique 3: narrative work for change

In many of the intervention activities, participants will be guided to tell multilayered narratives to deepen their self-understanding, to make sense of their life transitions, and to formulate their directions and desired strategies. From a constructivist perspective, narrative refers to a form of self-construction of meaning, knowledge, and experience. Its focus is not about the series of events, but how a person interprets the course of the events within and outside oneself (Kelly, 1955). Most importantly, the interpretation is not fixed once and for all time. Through collaborating with the facilitators, it is possible for participants to change their narratives, i.e., to refine or reconstruct their interpretation, and discover alternatives that they can synthesis in their new life directions (Neimeyer, 1995). This narrative change work allows students to locate their personal and career concerns in the bigger pattern of lived meaning, and therefore strengthening their self-confidence, independence, and autonomy to develop themselves in their expanded world (Savickas et al., 2009).

2.4.4 Technique 4: emotion-focused meaning-making

During the intervention activities, facilitators will frequently encourage participants to recognise and express their emotions and initiate dialogues to obtain timely and meaningful understanding of their presence. Emotion words in individuals’ narratives often indicate the presence of a boundary experience, i.e., a significant life theme that forms the foundation of their self-directedness (Savickas et al., 2009). Rather than ignoring or denying the emotions due to uncomfortable feelings, facilitators will demonstrate how the emotions can be valued and understood. Only by paying concentrated attention to illuminate their underlying messages, the strong motives for a behaviour, choice or decision of participants can be revealed and constructed to become an integral part of their personal and career identities.

2.4.5 Implementation of the intervention

This study will translate its five major intervention stages into five respective face-to-face group sessions. The first session will take the format of an interactive seminar. It aligns with the theme of stage 1 and includes provision of psychoeducation and information about the intervention content. Experiential activities will also be used to help them develop readiness to participate in the intervention activities. Participants will be divided into small groups. For each group, participants will receive four face-to-face group sessions in the theme of stages 2 to 5. All sessions will include ice-breaking games, signature activities using specific facilitation skills and techniques based on its intervention stage and targeted themes, and session conclusions and debriefings which focus on consolidating participants’ intervention experience and progress. All face-to-face sessions will be led by trained professionals with a background in Psychology, Counselling Psychology and Career Counselling. Throughout the intervention, the above-described facilitation skills and techniques will be used by the trained professionals to achieve the desired learning outcomes.

After each of the second, third and fourth face-to-face group sessions, an independent learning session will be arranged to invite participants to complete a worksheet tailored to strengthen the introduced attributes. In total, three worksheets will be distributed. Participants will be invited to continue their self-discovery outside the classroom setting, symbolising the expansion of reflective practices from classrooms to daily living, and from a one-off intervention to a lifelong practice. In addition, intended learning outcomes (ILOs) based on the intervention stages and themes will be specifically designed for each session. The group facilitators will align the content of activities and materials to the ILOs, to assure the quality and effectiveness of the intervention. The total duration of the entire intervention will be 12 h over 8 weeks. Table 1 shows a summary of the session themes, learning model, duration, and intended learning outcomes.

2.5 Data collection

Questionnaire data will be collected from participants at baseline, i.e., the first session and 1 week after the last session of the intervention to evaluate its effectiveness. In addition, semi-structured interviews with the participants (students), interventionists (group facilitators), and administrators (intervention coordinators) will be conducted to supplement the quantitative findings with insights obtained from interviewee’s experiences. Approximately 10% of intervention participants will be recruited.

2.5.1 Questionnaires

The participant outcome measures will be change from baseline in intervention participants’ positive personal resources to be collected at baseline and after participating in the intervention using the following questionnaires:

2.5.1.1 Post-traumatic growth inventory

Participants’ PTG will be assessed by the post-traumatic growth inventory (PTGI) developed by Tedeschi and Calhoun (1996), a 21-item scale which measures the extent to which individuals report positive life changes in the aftermath of a major life crisis. Items assess each of the five domains of PTG, while total scores are also reported. Example items of each of the five domains are “I have a greater feeling of self-reliance” (personal strength), “I more clearly see that I can count on people in times of trouble” (improved relationships), “I have developed new interests (new possibilities), “I changed my priorities about what is important in life” (appreciation of life), and “I have a better understanding of spiritual matters” (spiritual growth). Item ratings can range from 0 (I did not experience this change as a result of the event) to 5 (I experienced this change to a very great degree as a result of the event). The inventory has good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90) and test– retest reliability (r = 0.71; Tedeschi and Calhoun, 1996).

2.5.1.2 Career adapt-abilities scale

Participants’ overall career adaptability and career adaptability dimensions were measured with the 24-item international version of the career adapt-abilities scale (CAAS) (Savickas and Porfeli, 2012). The CAAS is composed of four subscales, each containing six items. These subscales assess concern, control, curiosity, and confidence, which are considered psychosocial resources that contribute to individuals’ career development. Example items for each of the subscales are “Thinking about what my future will be like” (concern), “Making decisions by myself” (control), “Exploring my surroundings” (curiosity), and “Performing tasks efficiently” (confidence). Participants will be asked to rate how strongly they have developed each of the above abilities on 5-point scales ranging from 1 (not strong) to 5 (strongest). The overall scale has been shown to have good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.95; Zacher, 2014).

2.5.1.3 Psychological flexibility measure

Participants’ process of psychological flexibility will be assessed using the 6-item self-reported psychological flexibility measure (PsyFlex) questionnaire developed by Gloster et al. (2021). It focuses on assessing psychological flexibility in a state form, capturing experiences from the past week with high temporal specificity. Sample items include “I engage thoroughly in things that are important, useful, or meaningful to me.” Each item is rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (very often) to 5 (very seldom). The total score can range from 6 to 30, with higher scores indicating greater psychological flexibility. The questionnaire demonstrates a one-factor structure and exhibits excellent reliability (r = 0.91; Gloster et al., 2021), as well as validity (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87; Browne et al., 2022) in previous studies.

At baseline, socio-demographics such as age, gender, marital status, religion, level of education, work experience, and socio-economic status will be collected. In addition, due to the nature of the current project which examines the positive aspects of challenging life experiences (PTG), participants will be asked to complete to additional measures to evaluate their level of psychological distress. The collection of such research data will provide a better understanding of the trauma profile of our target group. The two questionnaires include:

2.5.1.4 Life stressor checklist-revised

The life stressor checklist-revised (LSC-R) developed by Wolfe et al. (1997) will be included as a measure of exposure to major life crises to allow a wider range of possible highly stressful life events that may have been experienced by the participants before attending the intervention programme. The LSC-R is a self-report measure that assesses exposure to 30 highly stressful life events during the course of life, in particular, a focus on events relevant to women such as abortion and miscarriage is included. The LSC-R was chosen to assess a wide range of events rather than decide a priori that certain events were or were not perceived traumatic. No events were excluded, even though some events might not be considered traumatic by most people who have experienced them (e.g., abortion). Participants will be required to answer yes or no to the items. To recognise the diversity range of life stressors individuals can experience during their life time, item number 29 was included to allow respondents to report an event that is not included in the measure. For endorsed events, participants will be asked to provide further details. A sample item includes ‘Were you ever put in foster care or put up for adoption?’ (item 6). The LSC-R can be used for clinical or research purposes. Permission was granted by the by National Center for PTSD at www.ptsd.va.gov to use the measure in this study for research purposes.

2.5.1.5 Short form of posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5)

The PCL-5 is a brief self-report assessment tool used to evaluate the severity of symptoms associated with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). It originally consists of 20 items that are divided into four major clusters representing different symptom categories of PTSD: intrusion, avoidance, negative alterations in cognition and mood, and alterations in arousal and reactivity (Blevins et al., 2015). The current study will use its abbreviated version which is 4-item integer-scored short-form developed by Zuromski et al. (2019). Sample items include “Suddenly feeling or acting as if stressful experience were actually happening again (as if you were actually back there reliving it)?” Each item is rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). The total score can range from 4 to 20, with higher scores indicating higher risk of suffering from PTSD. The 4-item short-form can generate diagnoses that closely align with those obtained from the full PCL-5 and exhibits similar psychometric properties than the original version (Zuromski et al., 2019).

The estimated total completion time of the pre-and post-intervention questionnaire sets will be about 30 and 20 min, respectively. All instruments will adopt English version and be used with permission from the authors.

2.5.2 Interviews

At the end of the intervention period, semi-structured group interviews will be conducted with the participants (students), interventionists (group facilitators), and administrators (intervention coordinators). Interviewees will be invited to share (i) their experiences on the process of change during the SLCP intervention, and (ii) the feasibility and acceptability of implementing the SLCP intervention in the higher education setting.

An interview guide will be drafted in advance to provide a structure to the interview process, to facilitate a natural flow of conversation, and to anticipate and prepare for possible difficulties in eliciting information and addressing sensitive issues. Each group interview, including a briefing and a debriefing session, is expected to take approximately 60 min, and will be conducted in Chinese via zoom. The qualitative data will be audio-recorded and subsequently transcribed to provide insights.

2.6 Data analysis

Quantitative data will be analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics v.26 software to first perform a range of descriptive analysis tests to report the socio-demographic information of the intended sample and to investigate participant outcomes led by the intervention. To further examine the efficacy of taking the proposed intervention programme, paired-sample t-tests will be used to evaluate changes in participants’ post-traumatic growth, career adaptability and psychological flexibility before and after the intervention within group, with p < 0.05 to be considered significant.

Qualitative data will be audio-recorded and analysed according to the principles of thematic analysis, in addition to the criteria of feasibility and acceptability of an intervention as suggested by Eldridge et al. (2016). To illustrate, examination of the feasibility of the proposed intervention will encompass various aspects of intervention delivery. These aspects will include determining whether there is a demand for the intervention, assessing whether it can be implemented as planned, evaluating its practicality in light of resource and time limitations. The acceptability of the intervention will be examined by understanding how the recipients of the intervention, as well as those delivering it, perceive and respond to it.

Using a mixed methods design, quantitative and qualitative results will be integrated for analysis and interpretation to generate confirmed, discordant, or expanded findings. The combination of the two analytical methods will help to generate a research report that illuminates insight into a more holistic understanding of the effectiveness, feasibility, and acceptability of the proposed intervention.

2.7 Ethical issues and dissemination

This research study was approved by the Hong Kong Metropolitan University Research Ethics Committee (approval code: HE-SOL2022/02). Study participants will be asked for informed written consent before data collection. Although it is normal and not necessarily harmful that some participants may feel upset during and/or after research and intervention participation, the process may naturally cause some level of psychological discomfort to participants and such foreseeable risks and discomforts are clearly explained in the Participant Information Sheets. Contact details of local psychological support services are also provided at the end of the Participant Information Sheet in case if participants may wish to seek support following the sharing of such information. Participants who consider themselves to be psychologically unstable will be advised not to take part in the study.

Participants will be offered full anonymity and the rights to withdraw at any time. In the Participant Information Sheets, participants will be advised that they can choose to withdraw from the study for any reason at any time and they will not be penalised in any way. This message will be reiterated at the start and the end of the collection of both quantitative (questionnaires) and qualitative (semi-structured group interviews) data.

All data collected will remain confidential and protected according to the university guidelines. Only the research team will have access to study data. All research participants will be provided with a research code, known only to the principal investigator, to ensure that their identity remains anonymous and confidential. Hard paper copies of data, including the consent forms, will be stored in a locked filing cabinet accessed only by the principal investigator. All publications of data will be written in a way to disguise the identity of the research participants involved.

3 Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first protocol created for a psychosocial intervention specifically tailored to promote PTG, CA and PF for higher education students. The findings of this study will provide preliminary empirical evidence for creating growth-based career construction psychosocial interventions that specifically address the identified needs of higher education students, and this initiative will encourage knowledge and experience exchange for student services administrators, educators, psychologists, counsellors, and specialists on career-related interventions and student learning and support in the higher education sector.

Individuals use work and other life roles to construct, experiment and implement a stable self, enabling them to become who they are, people that they themselves like and that others value, and live the lives they have desired (Savickas, 2005). A career is a lifelong journey of self-exploration, and emerging adulthood is an important period that sets its foundation while students face a wide range of past, present, and anticipated stressors. Higher education students tend to discuss career and mental health issues when seeking support services (Hinkelman and Luzzo, 2007); nevertheless, as two related but distinctive disciplines, mental health and career counselling are often discussed as separate entities (Prescod and Zeligman, 2018). With the tailored focus of the SLCP intervention described in this protocol, it is expected that the interconnected psycho-social–emotional, academic and career-related needs of higher education students can be addressed more holistically. The suggested SLCP intervention therefore serves to fill a research gap in the literature and other existing psychosocial interventions developed for higher education students. The findings of this study will provide directions for future growth-and career-related research and practice in higher education settings.

The authors adopted a pragmatic approach in the design (e.g., broad inclusion criteria) to allow its potential applicability to other higher education settings. Given the widespread mental health and lifetime trauma associated with this life stage, nurturing students’ capability to recognise and gain inner strengths through life struggles may enable them to become more adaptable about their career and life in general. The higher education setting provides different opportunities for intervention, and the education environment is a powerful place for the acquisition of enduring learning and thinking skills, influencing students’ academic, career and life outcomes. In wider applications, integrating trauma and PTG with adaptability resources such as CA and PF into the curriculum and pedagogy can benefit students going through this pivotal life stage. A wide-scale, preventative approach to the provision of tailored student support can also help alleviate the enormous pressure placed on teaching staff who, whether before or after the pandemic, feel ill-equipped to deal with student mental health issues (Gulliver et al., 2018; Payne, 2022). The seamless approach may also be helpful when mental health stigma can inhibit help-seeking behaviour and disclosure (voluntary sharing of personal information), both for staff and students (Payne, 2022).

The proposed SLCP intervention recognises the nature and potentialities of being human. The intervention adopts the humanistic psychological perspective which focuses on recognising and maximising positive human potentialities (Sutich and Vich, 1969), while acknowledging the importance of understanding a balance between positives and negatives and how the negatives and the positives are related, a perspective now commonly known as positive psychology 2.0 (Wong, 2011; Joseph, 2021). This balanced, holistic approach in the SLCP intervention acknowledges shared vulnerabilities, respects individuality and diversity, embraces lifelong changes and challenges, and appreciates the power and purpose of human suffering and strengths, thus contributing to the shifting paradigm of a primary focus on risk mitigation toward personal development and growth. Future research should investigate the implementation of multifaceted interventions that focus on nurturing positive personal resources to understand and respond to the interrelated developmental, academic and career-related challenges associated with major life transitions of higher education students.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Research Ethics Committee at Hong Kong Metropolitan University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants will provide their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

KC: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Small Project Grant (SOL-SPG2022/02), Quality Enhancement Measures (Q1102), and Financial Support for Research Paper Publication of Hong Kong Metropolitan University.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of all personnel at Li Ka Shing School of Professional and Continuing Education, Hong Kong Metropolitan University, for providing all the necessary resources for the project. We are grateful to Dr. Benjamin T. Y. Chan for reviewing the initial draft of our manuscript, and for the stimulating discussions and his invaluable guidance and support during different stages of our project. We would also like to thank The Academy of Play and Psychotherapy for their support with the design and alignment of intervention activities with the proposed framework. We also wish to express our appreciation to Hong Kong Metropolitan University for funding this work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

CA, Career adaptability; PF, Psychological flexibility; PTG, Posttraumatic growth; SLCP, Sailing through life and my career path.

References

Abele, A. E., Volmer, J., and Spurk, D. (2012). “Career stagnation: underlying dilemmas and solutions in contemporary work environments” in Work and Quality of Life: Ethical Practices in Organizations. eds. N. P. Reilly, M. J. Sirgy, and C. A. Gorman (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 107–132.

Abu Asa’d, A. (2016). Level of Psychological Flow and its Relationship with Psychological Flexibility among Mu'tah University Students in Al-Karak Governorate/South Jordan. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 46, 119–130.

Alvesson, M. (2010). Self-doubters, strugglers, storytellers, surfers and others: Images of self-identities in organization studies. Hum. Relat. 63, 193–217. doi: 10.1177/0018726709350372

Argyropoulou, K., and Kaliris, A. (2018). From career decision-making to career decision-management: New trends and prospects for career counseling. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 5, 483–502. doi: 10.14738/assrj.510.5406

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 55, 469–480. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

Arthur, M. B., and Rousseau, D. M. (2001). The Boundaryless Career: A New Employment Principle for a New Organizational Era. USA: Oxford University Press.

Asikainen, H. (2018). Examining indicators for effective studying–The interplay between student integration, psychological flexibility and self-regulation in learning. Psychol. Soc. Educ. 10, 225–237. doi: 10.25115/psye.v10i2.1873

Asikainen, H., and Katajavuori, N. (2023). Exhausting and difficult or easy: the association between psychological flexibility and study related burnout and experiences of studying during the pandemic. Front. Educ. (Lausanne) 8:1215549. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1215549

Barnett, P., Arundell, L. L., Matthews, H., Saunders, R., and Pilling, S. (2021). Five hours to sort out your life: Qualitative study of the experiences of university students who access mental health support. Br. J. Psychiatry 7:e118. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2021.947

Beardslee, W. R. (1989). The role of self-understanding in resilient individuals: The development of a perspective. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 59, 266–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1989.tb01659.x

Betz, N. E., Klein, K. L., and Taylor, K. M. (1996). Evaluation of a short form of the career decision-making self-efficacy scale. J. Career Assess. 4, 47–57. doi: 10.1177/106907279600400103

Bewick, B. M., Gill, J., Mulhern, B., Barkham, M., and Hill, A. J. (2008). Using electronic surveying to assess psychological distress within the UK university student population: a multi-site pilot investigation. E-J. Appl. Psychol. 4, 1–5. doi: 10.7790/ejap.v4i2.120

Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K., and Domino, J. L. (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J. Trauma. Stress. 28, 489–498. doi: 10.1002/jts.22059

Bos, E. H., Snippe, E., de Jonge, P., and Jeronimus, B. F. (2016). Preserving subjective wellbeing in the face of psychopathology: buffering effects of personal strengths and resources. PLoS One 11:e0150867. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150867

Breslau, N. (2009). The epidemiology of trauma, PTSD, and other posttrauma disorders. Trauma Violence Abuse 10, 198–210. doi: 10.1177/1524838009334448

Brooks, M., Lowe, M., Graham-Kevan, N., and Robinson, S. (2016). Posttraumatic growth in students, crime survivors and trauma workers exposed to adversity. Personal. Individ. Differ. 98, 199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.04.051

Browne, A., Stafford, O., Berry, A., Murphy, E., Taylor, L. K., Shevlin, M., et al. (2022). Psychological flexibility mediates wellbeing for people with adverse childhood experiences during COVID-19. J. Clin. Med. 11:377. doi: 10.3390/jcm11020377

Bruffaerts, R., Mortier, P., Kiekens, G., Auerbach, R. P., Cuijpers, P., Demyttenaere, K., et al. (2018). Mental health problems in college freshmen: Prevalence and academic functioning. J. Affect. Disord. 225, 97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.044

Bulut, S., and Sülük, İ. (2021). Effect of life events on career choice: trauma sampling. Academixs J. Clin. Psychiatry Ment. Health 1, 1–4.

Cage, E., James, A. I., Newell, V., and Lucas, R. (2021). Expectations and experiences of the transition out of university for students with mental health conditions. Eur. J. High. Educ. 12, 171–193. doi: 10.1080/21568235.2021.1917440

Cámara, M., and Calvete, E. (2021). Early maladaptive schemas as moderators of the impact of stressful events on anxiety and depression in university students. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 34, 58–68. doi: 10.1007/s10862-011-9261-6

Cantor, N., Norem, J. K., Niedenthal, P. M., Langston, C. A., and Brower, A. M. (1987). Life tasks, self-concept ideals, and cognitive strategies in a life transition. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 53, 1178–1191. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.53.6.1178

Charbonnier, E., Trémolière, B., Baussard, L., Goncalves, A., Lespiau, F., Philippe, A. G., et al. (2022). Effects of an online self-help intervention on university students' mental health during COVID-19: A non-randomized controlled pilot study. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 5:100175. doi: 10.1016/j.chbr.2022.100175

Choi, A. (2018). Emotional Well-Being of Children and Adolescents: Recent Trends and Relevant Factors. OECD Education Working Papers No. 169.

Christiaens, A. H. T., Nelemans, S. A., Meeus, W. H. J., and Branje, S. (2021). Identity development across the transition from secondary to tertiary education: A 9-wave longitudinal study. J. Adolesc. 93, 245–256. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.03.007

Chronister, K. M., Harley, E., Aranda, C. L., Barr, L., and Luginbuhl, P. (2012). Community-based career counseling for women survivors of intimate partner violence: a collaborative partnership. J. Career Dev. 39, 515–539. doi: 10.1177/0894845311401618

Collie, R. J., and Martin, A. J. (2017). Teachers' sense of adaptability: examining links with perceived autonomy support, teachers' psychological functioning, and students' numeracy achievement. Learn. Individ. Differ. 55, 29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2017.03.003

Confino, D., Einav, M., and Margalit, M. (2023). Post-traumatic growth: the roles of the sense of entitlement, gratitude and hope. Int. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol. 8, 453–465. doi: 10.1007/s41042-023-00102-9

Conley, C. S. (2015). “SEL in Higher Education” in Handbook of Social and Emotional Learning: Research and Practice. ed. J. A. Durlak (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 197–212.

Conley, C. S., Durlak, J. A., and Kirsch, A. C. (2015). A meta-analysis of universal mental health prevention programs for higher education students. Prev. Sci. 16, 487–507. doi: 10.1007/s11121-015-0543-1

Conley, C. S., Shapiro, J. B., Huguenel, B. M., and Kirsch, A. C. (2020). Navigating the college years: Developmental trajectories and gender differences in psychological functioning, cognitive-affective strategies, and social well-being. Emerg. Adulthood 8, 103–117. doi: 10.1177/2167696818791603

Di Fabio, A., Maree, J. G., and Kenny, M. E. (2019). Development of the Life Project Reflexivity Scale: A new career intervention inventory. J. Career Assess. 27, 358–370. doi: 10.1177/1069072718758065

Eldridge, S. M., Lancaster, G. A., Campbell, M. J., Thabane, L., Hopewell, S., Coleman, C. L., et al. (2016). Defining feasibility and pilot studies in preparation for randomised controlled trials: development of a conceptual framework. PLoS One 11:e0150205. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150205

Feraco, T., Casali, N., and Meneghetti, C. (2022). Do strengths converge into virtues? An item-, virtue-, and scale-level analysis of the Italian values in Action Inventory of Strengths-120. J. Pers. Assess. 104, 395–407. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2021.1934481

Finnerty, R., Marshall, S. A., Imbault, C., and Trainor, L. J. (2021). Extra-curricular activities and well-being: Results from a survey of undergraduate university students during COVID-19 lockdown restrictions. Front. Psychol. 12:647402. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647402

Franzoi, I. G., Sauta, M. D., Barbagli, F., Avalle, C., and Granieri, A. (2022). Psychological Interventions for Higher Education Students in Europe: A Systematic Literature Review. Youth 2, 236–257. doi: 10.3390/youth2030017

Fugate, M., Kinicki, A. J., and Ashforth, B. E. (2004). Employability: A psycho-social construct, its dimensions, and applications. J. Vocat. Behav. 65, 14–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2003.10.005

Geng, S., Law, K. M., and Niu, B. (2019). Investigating self-directed learning and technology readiness in blending learning environment. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 16, 1–22. doi: 10.1186/s41239-019-0147-0

Gloster, A. T., Block, V. J., Klotsche, J., Villanueva, J., Rinner, M. T., Benoy, C., et al. (2021). Psy–Flex: a contextually sensitive measure of psychological flexibility. J. Contextual Behav. Sci. 22, 13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2021.09.001

Grosemans, I., Hannes, K., Neyens, J., and Kyndt, E. (2020). Emerging Adults Embarking on Their Careers: Job and Identity Explorations in the Transition to Work. Youth Soc. 52, 795–819. doi: 10.1177/0044118X18772695

Gulliver, A., Farrer, L., Bennett, K., Ali, K., Hellsing, A., Katruss, N., et al. (2018). University staff experiences of students with mental health problems and their perceptions of staff training needs. J. Ment. Health (Abingdon, England) 27, 247–256. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2018.1466042

Hailikari, T., Nieminen, J., and Asikainen, H. (2022). The ability of psychological flexibility to predict study success and its relations to cognitive attributional strategies and academic emotions. Educ. Psychol. 42, 626–643. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2022.2059652

Hall, D. T. (2004). The protean career: A quarter-century journey. J. Vocat. Behav. 65, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2003.10.006

Hardcastle, K., Bellis, M. A., Ford, K., Hughes, K., Garner, J., and Ramos Rodriguez, G. (2018). Measuring the relationships between adverse childhood experiences and educational and employment success in England and Wales: Findings from a retrospective study. Public Health 165, 106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2018.09.014

Hinkelman, J. M., and Luzzo, D. A. (2007). Mental health and career development of college students. J. Couns. Dev. 85, 143–147. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2007.tb00456.x

Holliman, A. J., Collie, R. J., and Martin, A. J. (2020). “Adaptability and academic development” in The Encyclopedia of Child and Adolescent Development. eds. S. Hupp and J. D. Jewell (New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.).

Holliman, A. J., Waldeck, D., Jay, B., Murphy, S., Atkinson, E., Collie, R. J., et al. (2021). Adaptability and social support: examining links with psychological wellbeing among UK students and non-students. Front. Psychol. 12:636520. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.636520

Husman, J., and Shell, D. F. (2008). Beliefs and perceptions about the future: A measurement of future time perspective. Learn. Individ. Differ. 18, 166–175. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2007.08.001

Jeffords, J. R., Bayly, B. L., Bumpus, M. F., and Hill, L. G. (2020). Investigating the relationship between university students’ psychological flexibility and college self-efficacy. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. Res. Theory Pract. 22, 351–372. doi: 10.1177/1521025117751071

Jerusalem, M., and Mittag, W. (1995). “Self–efficacy in stressful life transitions” in Self–Efficacy in Changing Societies. eds. A. Bandura and R. E. Watts (England: Cambridge University Press), 177–201.

Johnston, C. S. (2018). A Systematic Review of the Career Adaptability Literature and Future Outlook. J. Career Assess. 26, 3–30. doi: 10.1177/1069072716679921

Joseph, S. (2021). How humanistic is positive psychology? Lessons in positive psychology from Carl Rogers’ person-centered approach—it’s the social environment that must change. Front. Psychol. 12:709789. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.709789

Kadam, P., and Bhalerao, S. (2010). Sample size calculation. Int. J. Ayurveda Res. 1, 55–57. doi: 10.4103/0974-7788.59946

Kadison, R., and DiGeronimo, T. F. (2004). College of the overwhelmed: the campus mental health crisis and what to do about it. J. Coll. Orientat. Trans. 13, 56–59.

Kashdan, T. B., and Rottenberg, J. (2010). Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 30, 865–878. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.001

Katajavuori, N., Vehkalahti, K., and Asikainen, H. (2023). Promoting university students’ well-being and studying with an acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT)-based intervention. Curr. Psychol. 42, 4900–4912. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01837-x

Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O., and Walters, E. E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62, 617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617

Knowles, M. S. (1975). Self–Directed Learning: A Guide for Learners and Teachers. New York: Association Press.

Kou, W. J., Wang, X. Q., Li, Y., Ren, X. H., Sun, J. R., Lei, S. Y., et al. (2021). Research trends of post–traumatic growth from 1996 to 2020: A bibliometric analysis based on Web of Science and CiteSpace. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 3:100052. doi: 10.1016/j.jadr.2020.100052

Lageborn, C. T., Ljung, R., Vaez, M., and Dahlin, M. (2017). Ongoing university studies and the risk of suicide: a register-based nationwide cohort study of 5 million young and middle-aged individuals in Sweden, 1993-2011. BMJ Open 7:e014264. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014264

Lefevor, G. T., Jensen, D. R., Jones, P. J., Janis, R. A., and Hsieh, C. H. (2018) ‘An Undergraduate Positive Psychology Course as Prevention and Outreach’. To be Published in Psyarxiv. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/G-Lefevor/publication/329439129_An_Undergraduate_Positive_Psychology_Course_as_Prevention_and_Outreach/links/5c79a1d8299bf1268d30a088/An-Undergraduate-Positive-Psychology-Course-as-Prevention-and-Outreach.pdf (Accessed October 27, 2023)

Levin, M. E., Hayes, S. C., Pistorello, J., and Seeley, J. R. (2016). Web-Based Self-Help for Preventing Mental Health Problems in Universities: Comparing Acceptance and Commitment Training to Mental Health Education. J. Clin. Psychol. 72, 207–225. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22254

Linley, P. A., and Joseph, S. (2004). Positive change following trauma and adversity: a review. J. Trauma. Stress. 17, 11–21. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000014671.27856.7e

Lodi, E., Zammitti, A., Magnano, P., Patrizi, P., and Santisi, G. (2020). Italian adaption of self-perceived employability scale: psychometric properties and relations with the career adaptability and well-being. Behav. Sci. 10:82. doi: 10.3390/bs10050082

London, M. (1997). Overcoming career barriers: A model of cognitive and emotional processes for realistic appraisal and constructive coping. J. Career Dev. 24, 25–38. doi: 10.1177/089484539702400102

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., and Norman, S. M. (2007). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 60, 541–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00083.x

Macalli, M., Côté, S., and Tzourio, C. (2020). Perceived parental support in childhood and adolescence as a tool for mental health screening in students: A longitudinal study in the Share cohort. J. Affect. Disord. 266, 512–519. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.02.009

Mahoney, M. J. (1982). “Psychotherapy and human change processes” in Psychotherapy Research and Behavior Change American. eds. J. H. Harvey and M. M. Parks (Washington, USA: American Psychological Association), 77–122.

Mailloux, S. L. (2014). The ethical imperative: Special considerations in the trauma counseling process. Traumatology: An. Int. J. 20, 50–56. Available at. doi: 10.1177/1534765613496649

March, J. G. (1994). A Primer on Decision Making: How Decisions Happen. New York, New York: The Free Press.

Marshall, E. J., and Brockman, R. N. (2016). The Relationships Between Psychological Flexibility, Self-Compassion, and Emotional Well-Being. J. Cogn. Psychother. 30, 60–72. doi: 10.1891/0889-8391.30.1.60

Martin, A. J., Nejad, H. G., Colmar, S., and Liem, G. A. D. (2013). Adaptability: how students’ responses to uncertainty and novelty predict their academic and non-academic outcomes. J. Educ. Psychol. 105, 728–746. doi: 10.1037/a0032794

Martínez-Martí, M. L., and Ruch, W. (2016). Character strengths predict resilience over and above positive affect, self-efficacy, optimism, social support, self-esteem, and life satisfaction. J. Posit. Psychol. 12, 110–119. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2016.1163403

Masdonati, J., Frésard, C. É., and Parmentier, M. (2022). involuntary career changes: a lonesome social experience. Front. Psychol. 13:899051. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.899051

Mather, L., Blom, V., and Svedberg, P. (2014). Stressful and traumatic life events are associated with burnout-a cross-sectional twin study. Int. J. Behav. Med. 21, 899–907. doi: 10.1007/s12529-013-9381-3

Mattanah, J. F., Ayers, J. F., Brand, B. L., Brooks, L. J., Quimby, J. L., and McNary, S. W. (2010). A social support intervention to ease the college transition: Exploring main effects and moderators. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 51, 93–108. doi: 10.1353/csd.0.0116

Meijers, F., and Lengelle, R. (2016). Reflective career dialogues. S. Afr. J. High. Educ. 30, 21–35. doi: 10.20853/30-3-636

Metzler, M., Merrick, M. T., Klevens, J., Ports, K. A., and Ford, D. C. (2017). Adverse childhood experiences and life opportunities: shifting the narrative. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 72, 141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.10.021

Mortari, L. (2015). ‘Reflectivity in research practice: An overview of different perspectives. Int. J. Qual. Methods 14:1609406915618045. doi: 10.1177/1609406915618045

Neimeyer, R. A. (1995). “Constructivist psychotherapies: Features, foundations, and future directions” in Constructivism in Psychotherapy. eds. R. A. Neimeyer and M. J. Mahoney (Washington, USA: American Psychological Association), 11–38.

Newark, D. A. (2014). Indecision and the construction of self. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 125, 162–174. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2014.07.005

Niemiec, R. (2020). Six functions of character strengths for thriving at times of adversity and opportunity: a theoretical perspective. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 15, 551–572. doi: 10.1007/s11482-018-9692-2

Niemiec, R. M., and Pearce, R. (2021). The practice of character strengths: unifying definitions, principles, and exploration of what’s soaring, emerging, and ripe with potential in science and in practice. Front. Psychol. 3863:590220. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.590220

Nik Jaafar, N. R., Abd Hamid, N., Hamdan, N. A., Rajandram, R. K., Mahadevan, R., Mohamad Yunus, M. R., et al. (2022). Posttraumatic growth, positive psychology, perceived spousal support, and psychological complications in head and neck cancer: evaluating their association in a longitudinal study. Front. Psychol. 13:920691. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.920691

Oshiro, R., Soejima, T., Kita, S., Benson, K., Kibi, S., Hiraki, K., et al. (2023). Reliability and Validity of the Japanese Version of the Short Form of the Expanded Version of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI-X-SF-J): A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20:5965. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20095965

Öztemel, K. (2021). The Predictive Role of Happiness, Social Support, and Future Time Orientation in Career Adaptability. J. Career Dev. 48, 199–212. doi: 10.1177/0894845319840437Yıldız–Akyol, E

Park, N., Peterson, C., and Seligman, M. E. P. (2006). Character strengths in fifty-four nations and the fifty US states. J. Posit. Psychol. 1, 118–129. doi: 10.1080/17439760600619567

Pascoe, M. C., Hetrick, S. E., and Parker, A. G. (2020). The impact of stress on students in secondary school and higher education. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 25, 104–112. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2019.1596823

Payne, H. (2022). Teaching staff and student perceptions of staff support for student mental health: a university case study. Educ. Sci. 12:237. doi: 10.3390/educsci12040237

Peterson, C., and Seligman, M. E. (2004). Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification, vol. 1. Washington, USA, New York, NY: American Psychological Association, Oxford University Press.

Prescod, D. J., and Zeligman, M. (2018). Career adaptability of trauma survivors: The moderating role of posttraumatic growth. Career Dev. Q. 66, 107–120. doi: 10.1002/cdq.12126

Ramos, K., and Lopez, F. G. (2018). Attachment security and career adaptability as predictors of subjective well-being among career transitioners. J. Vocat. Behav. 104, 72–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2017.10.004

Ran, J., Liu, H., Yuan, Y., Yu, X., and Dong, T. (2023). Linking career exploration, self-reflection, career calling, career adaptability and subjective well-being: a self-regulation theory perspective. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 16, 2805–2817. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S420666

Read, J. P., Ouimette, P., White, J., Colder, C., and Farrow, S. (2011). Rates of DSM–IV–TR trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder among newly matriculated college students. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 3, 148–156. doi: 10.1037/a0021260

Rudolph, C. W., Lavigne, K. N., Katz, I. M., and Zacher, H. (2017). Linking dimensions of career adaptability to adaptation results: A meta-analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 102, 151–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2017.06.003

Russo, A., Zammitti, A., and Zarbo, R. (2023). Career readiness and well-being: The mediation role of strategies for coping with career indecision. Aust. J. Career Dev. 32, 14–26. doi: 10.1177/10384162221142747

Ryan, M., and Ryan, M. (2013). Theorising a model for teaching and assessing reflective learning in higher education. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 32, 244–257. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2012.661704

Salimi, S., Asgari, Z., Izadikhah, Z., and Abedi, M. (2022). Personality and Post-Traumatic Growth: the Mediating Role of Career Adaptability Among Traumatized Adolescents. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 15, 883–892. doi: 10.1007/s40653-021-00376-8

Santilli, S., Nota, L., Ginevra, M. C., and Soresi, S. (2014). Career adaptability, hope and life satisfaction in workers with intellectual disability. J. Vocat. Behav. 85, 67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2014.02.011

Savickas, M. L. (1997). Career adaptability: An integrative construct for life-span, life-space theory. Career Dev. Q. 45, 247–259. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-0045.1997.tb00469.x

Savickas, M. L. (2005). “The theory and practice of career construction” in Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work. eds. S. D. Brown and R. W. Lent (Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons), 42–70.

Savickas, M. L., and Hartung, P. J. (2012). My Career Story: An Autobiographical Workbook for Life–Career Success. Available at: http://www.vocopher.com/CSI/CCI_workbook.pdf (Accessed October 27, 2023).

Savickas, M. L., and Lent, R. W. (Eds.) (1994). Convergence in career development theories: Implications for science and practice. Palo Alto, CA: CPP Books.

Savickas, M. L., Nota, L., Rossier, J., Dauwalder, J., Duarte, M. E., Guichard, J., et al. (2009). Life designing: a paradigm for career construction in the 21st century. J. Vocat. Behav. 75, 239–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2009.04.004

Savickas, M. L., and Porfeli, E. J. (2012). Career Adapt-Abilities Scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. J. Vocat. Behav. 80, 661–673. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.011

Schein, E. H. (1978). Career Dynamics: Matching Individual and Organizational Needs. Reading, Massachusetts: Addison–Wesley Publishing Company.

Seligman, M. E. P., and Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: an introduction. Am. Psychol. 55, 5–14. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

Shek, D. T. L., and Sun, R. C. F. (2012). Promoting psychosocial competencies in university students: evaluation based on a one-group pre-test/post-test design. Int. J. Disabil. Hum. Dev. 11, 229–234. doi: 10.1515/ijdhd-2012-0039

Soares, J., Carvalho, C., and Silva, A. D. (2022). A systematic review on career interventions for university students: Framework, effectiveness, and outcomes. Aust. J. Career Dev. 31, 81–92. doi: 10.1177/10384162221100460

Soresi, S., Nota, L., and Ferrari, L. (2012). Career Adapt-Abilities Scale-Italian Form: psychometric properties and relationships to breadth of interests, quality of life, and perceived barriers. J. Vocat. Behav. 80, 705–711. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.020

Strauser, D. R., Lustig, D. C., Cogdal, P. A., and Uruk, A. Ç. (2006). Trauma Symptoms: Relationship With Career Thoughts, Vocational Identity, and Developmental Work Personality. Career Dev. Q. 54, 346–360. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-0045.2006.tb00199.x

Taku, K., Calhoun, L. G., Tedeschi, R. G., Gil-Rivas, V., Kilmer, R. P., and Cann, A. (2007). Examining posttraumatic growth among Japanese university students. Anxiety Stress Coping 20, 353–367. doi: 10.1080/10615800701295007