- 1SARChI Teaching and Learning, Faculty of Education, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

- 2School of Education, Faculty of Arts and Design, Durban University of Technology, Durban, South Africa

While questions continue to be asked about teachers’ content and pedagogical content knowledge to ensure quality education systems, less consideration has been placed on teachers’ ability to teach for citizenship and social cohesion that contributes equally to quality education systems. This paper illuminates the understandings of citizenship and social cohesion held by South African and Zimbabwean teachers, their experiences of Continuous Professional Development (CPD) that promote the values of citizenship and social cohesion, and how they practice these learnings in their school contexts. The South African study presents the views of eleven high school teachers where data was procured through semi structured interviews. The Zimbabwean study presents the views of seventeen high school teachers, where data was procured through an open- ended questionnaire. The two studies suggest that teachers in South Africa and Zimbabwe share similar perspectives on citizenship and social cohesion, emphasizing nation-building and respect as key drivers. Teachers also report aligning their teaching practices with citizenship and social cohesion values with a limited focus on political participation, possibly due to fear of negative repercussions. Further, CPD for citizenship and social cohesion is fragmented, inconsistent and mostly absent. This study is an important contribution to debates about improving quality education and ensuring deliberative democracies in post-conflict and post-colonial states in the Global South. Teachers play a critical role in socializing schoolchildren for citizenship. As such, they need to be equipped with the skills that allow them to do so. Further to this, teachers also need the freedom and autonomy to discuss politics in the classroom without fear of negative repercussions, including alienation and fear of losing their jobs.

Introduction

The positive effects of good-quality teachers and teaching cannot be overstated. Teachers not only have the ability to improve the quality of education systems in general but, as agents of citizenship and social cohesion, they are able to mold and influence the actions and beliefs of learners as these youths embark on their journey to becoming participatory citizens in society (Araujo et al., 2016). Whilst there are several factors that may realize the objective of quality education, including school context, teaching and learning resources, working conditions and teacher governance, it is teacher training that is the most impactful (Sayed et al., 2018). As a continuous process, the beginning of developing a teacher does not necessarily start at the onset of Initial Teacher Education (ITE), instead, teacher development starts when the teacher-to-be is still a learner in school. As such, given that what teachers do or do not do is in response to their early learning experiences (Allender and Allender, 2006). These beliefs are then sharpened, reinforced, or disrupted by formalized training.

This paper is concerned with the process of teacher training and development once students have graduated and have commenced their journeys as professionals. Training in this phase of teacher development is referred to as Continuous Professional Development (CPD), often interchanged in the literature as Continuous Professional Teacher Development (CPTD) or Teacher Professional Development (TPD). Popova et al. (2022, 108) note that “the principal tool that countries across the income spectrum use to improve the knowledge and skills of their practicing teachers is professional development (PD), which refers to on-the-job training activities ranging from formal, lecture-style training to mentoring and coaching.”

In this paper, CPD is defined as “activities that increase the knowledge and skill base of teachers” (Sayed and Bulgrin, 2020, 8). In drawing on empirical data from two studies, one in South Africa and one in Zimbabwe, this paper aims to ascertain teachers’ understanding of citizenship and social cohesion as well as teachers’ experiences of CPD for citizenship and social cohesion, and how these learnings are realized in practice.

Social justice orientated, (see Rawls, 1971; Bell, 2007; Connell, 2014; De Sousa Santos, 2014), the findings suggest that, firstly, teachers’ understandings of citizenship and social cohesion are influenced by varied training experiences, opportunities and socio-political contexts. Secondly, these affective elements of teaching and learning are rarely discussed and promoted through CPD programmes and, thirdly, despite very little exposure to CPD for citizenship and social cohesion, teachers still claim to promote and incorporate these values in their teaching practices and pedagogical approaches. The paper argues that equal emphasis should be placed on CPD for citizenship and social cohesion (and non-cognitive aspects in general) as this may support learners as they develop into adulthood to become participatory citizens who effectively utilize their agency to build strong democracies. This is particularly important in countries, such as South Africa and Zimbabwe, where the lived reality is suggestive of a crumbling democracy.

This paper is divided into seven sections. After the introduction, the paper commences with a discussion of the theoretical underpinnings of citizenship and social cohesion and how this often materializes in post-conflict and post-colonial states such as South Africa and Zimbabwe. This is followed by a situational analysis of CPD in the SADC region by discussing the latest CPD framework. The paper then discusses the provision of CPD in South Africa and Zimbabwe, with a specific emphasis on CPD for citizenship and social cohesion. The last three sections discuss the methodology, the findings, and the conclusions, respectively.

Citizenship and social cohesion as foundational to democracy

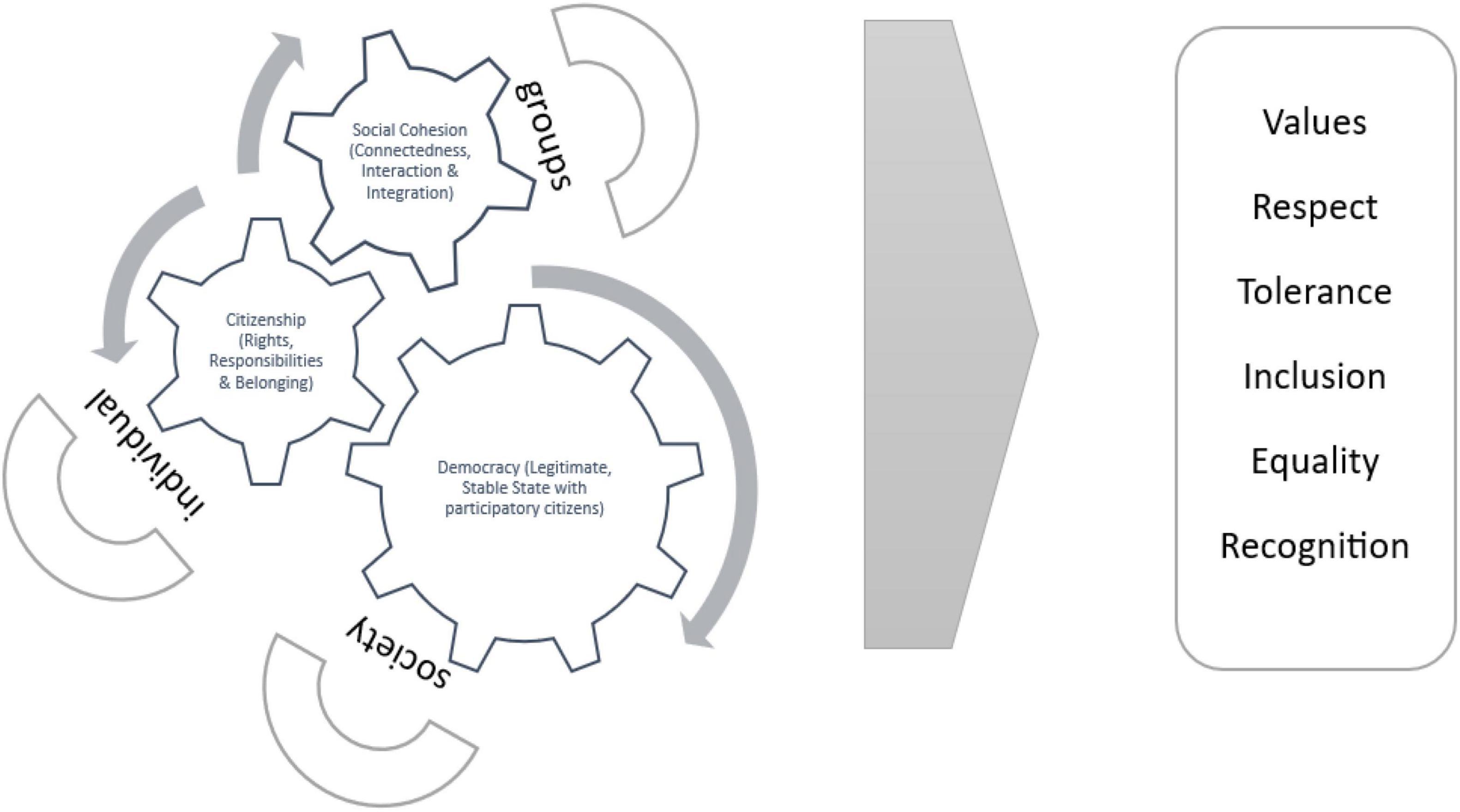

Citizenship, social cohesion and democracy are interrelated, but interdependent for their full realization. They also operate at different levels. Citizenship has a focus on individual rights, responsibilities and belonging (Marshall, 1950; Westheimer and Kahne, 2004; Yuval-Davis, 2006; Singh, 2020); social cohesion focuses on group dynamics (Durkheim, 1893; Rudiger and Spencer, 2004; Barolsky, 2016); and democracy operates at a societal level (Rawls, 1971). Cuellar (2009, 5) argues that “democracy and social cohesion promote the establishment of citizenship with rights and responsibilities differently but in a complementary manner.” Social cohesion is foundational to a stable democracy (Rawls, 1971) because it acknowledges the diversity of society, and promotes the values of citizenship, including the reduction of inequality. Whilst social cohesion can be defined as “the extent of connectedness and solidarity among groups in society” (Manca, 2014, 6026), citizenship is about individual rights, responsibilities and belonging to those groups (Singh, 2020). As such, the link between social cohesion and citizenship is that “social cohesion refers to people’s relationships and interactions in society, including the role of citizenship” (Cuellar, 2009, 3). Citizenship and social cohesion together are required to realize a flourishing democracy and are all underpinned by the values of respect, inclusion, tolerance, equality, and recognition. Figure 1 below depicts the interrelated nature of citizenship, social cohesion, and democracy with their common embedded values.

South Africa and Zimbabwe are technical democracies in that their constitutions reflect states that subscribe to the values of democracy. However, in practice, the majority of their populations are not benefitting from this, putting these countries and their citizens in disarray. South Africa and Zimbabwe are regional neighbors, both situated in sub-Saharan Africa, and they also share some historical similarities, such as being colonized by the British, leaving behind a legacy that impacted and still impacts language and the provision of education. Howell et al. (2018, 127) note that “the provision of education in both South Africa and Zimbabwe has been strongly shaped by the inequalities of their colonial pasts and the efforts by their post-liberation governments to build new education systems where all children have equitable access to quality education.”

South Africa, currently in its third decade of democratic rule, has been plagued with high levels of inequalities to such an extent that it has been listed one of the most unequal countries in the world. Coupled with high levels of crime and violence, poor leadership, infrastructural challenges, such as water and electricity outages, corruption, high levels of unemployment, and distrust in authority, it is obvious that the country needs a socially cohesive society. Similarly, in Zimbabwe, Gavin (2022, Para. 1) notes that “conditions for the people of Zimbabwe continue to go from bad to worse”. Politically, the electoral process has been critiqued for inconsistencies and a lack of credibility given the outcomes over the past several decades. With the merging of the military and the ruling party, Zimbabwe has often been referred to as a “military dictatorship” (Grignon, 2008). Sigauke (2019, 246) also mentions that Zimbabwe has “been characterized by hyperinflation, social hemorrhage, and political conflict … [and for] most of the 1990s and beyond, Zimbabwe has been characterized by a gradual economic decline characterized by rising unemployment, underdevelopment, and disillusionment with elite corruption.”

In countries where there is a history of violence and conflict, the pursuit of quality education is challenging when contexts remain shaped by inequality, exclusion, injustice and marginalization. However, despite this, education remains the key medium through which social cohesion, social justice, citizenship and social solidarity can be mobilized and promoted therefore interventions that seek to realize this remain important (Durkheim, 1964). Social cohesion is increasingly recognized, in policy and academic discussions, as an important determinant of communities’ ability to absorb shocks, particularly in conflict and post-conflict affected contexts, where limited state capacity often meets extensive urgent needs.

In order to restore dignity, respect and recognition in post-conflict or post-colonial states, fostering the values of citizenship and social cohesion becomes a social justice imperative. Social cohesion, in particular, addresses critical development challenges where collective action is required to (re) build societies and regain trust in authorities. This is particularly important in conflict or post-conflict states, where values of citizenship and activities that foster social cohesion are under threat from being realized.

The state of CPD in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region

This section provides an overview of CPD developments in the SADC region as a way of providing a situational analysis for countries within this consortium.

The professional development of teachers has piqued the interest of governments and researchers alike as they acknowledge the positive effect CPD has on learner performance and teacher and teaching quality. As such, multilateral organizations, such as UNESCO, have engaged heavily with African states as a mechanism for improving the provision of public education on the continent. The UNESCO Regional Office for Southern Africa (ROSA) has, since 2015, initiated a series of meetings, workshops and consultations with SADC countries to generate evidence about the importance of improving the quality of teachers. From these initial discussions, two key priorities emerged−teacher standards and competencies, and CPD (UNESCO, 2020). In the context of CPD, the SADC countries, represented by senior government officials in charge of teachers, agreed that:

• “countries needed to systematize and harmonize their teacher training policies and practices on CPD”

• “research was needed to collect more information and have a more in-depth understanding of the status of CPD practices for teachers in SADC countries”; and

• “a SADC regional framework would help countries develop and/or strengthen their own national CPD programmes”, which includes a focus on TVET education (UNESCO, 2020, 5).

In 2019 and 2020, UNESCO commissioned an investigation into the state of CPD in the SADC region (SADC and UNESCO, 2019). The study was focused on Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe, where each presented a country case study that would inform the CPD Framework to improve CPD in the region. A synthesis of the country reviews, drawn from the draft SADC Regional Framework on Continuing Professional Development (CPD) for Teachers, is described below:

“All countries have documents that declare and acknowledge the importance of CPD in the region, as a way of improving the quality of education and working toward realizing SDG4. However, not all documents are presented as policies. A CPD policy overview in the region ranges from clear stand-alone CPD policies, to draft policies, or no policies. Where CPD policies are available, the governance structures differ ranging from autonomous institutions to Ministries of Education, with the overall responsibilities for implementing CPD in most countries residing with the Ministry or Department of Education. In some instances, authority is also given to quasi-governmental organizations, teacher training institutes and local government departments. At this stage, the synthesis could not establish the efficacy of centralized versus decentralized models and it was highlighted that more research needed to be commissioned to explore these differences. Whilst there is clear evidence in most states of training to improve teacher knowledge and skills, irregular and unpredictable funding remains a challenge, as only a few states have dedicated CPD budgets. Many states in the region depend on donor or external funding, and this has implications for how CPD is defined and what is prioritized. With the exception of Mozambique and Namibia, no reference was made to TVET sector or intersectional issues. Overall, the review found that CPD in the region is either [sic] inadequate, ineffective, not available or completely absent. There was also no evidence of rigorous monitoring and evaluation of CPD” Adapted from the Draft SADC Regional Framework on Continuing Professional Development (CPD) for Teachers.

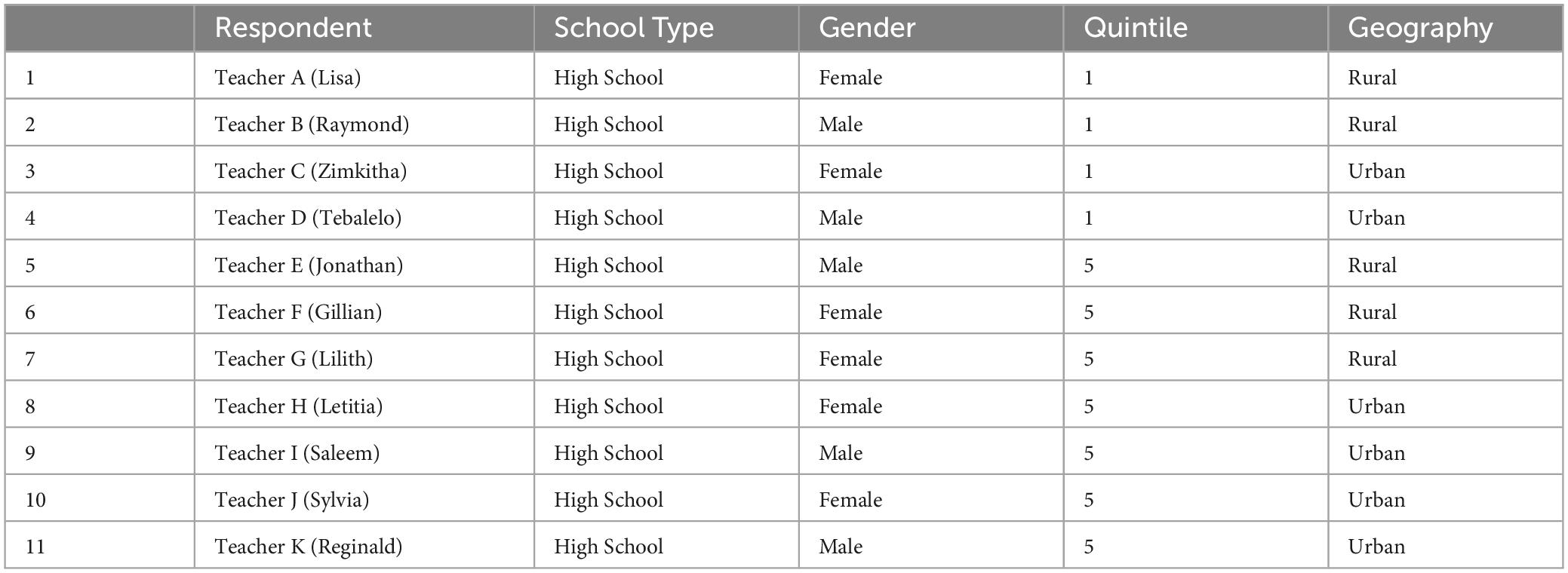

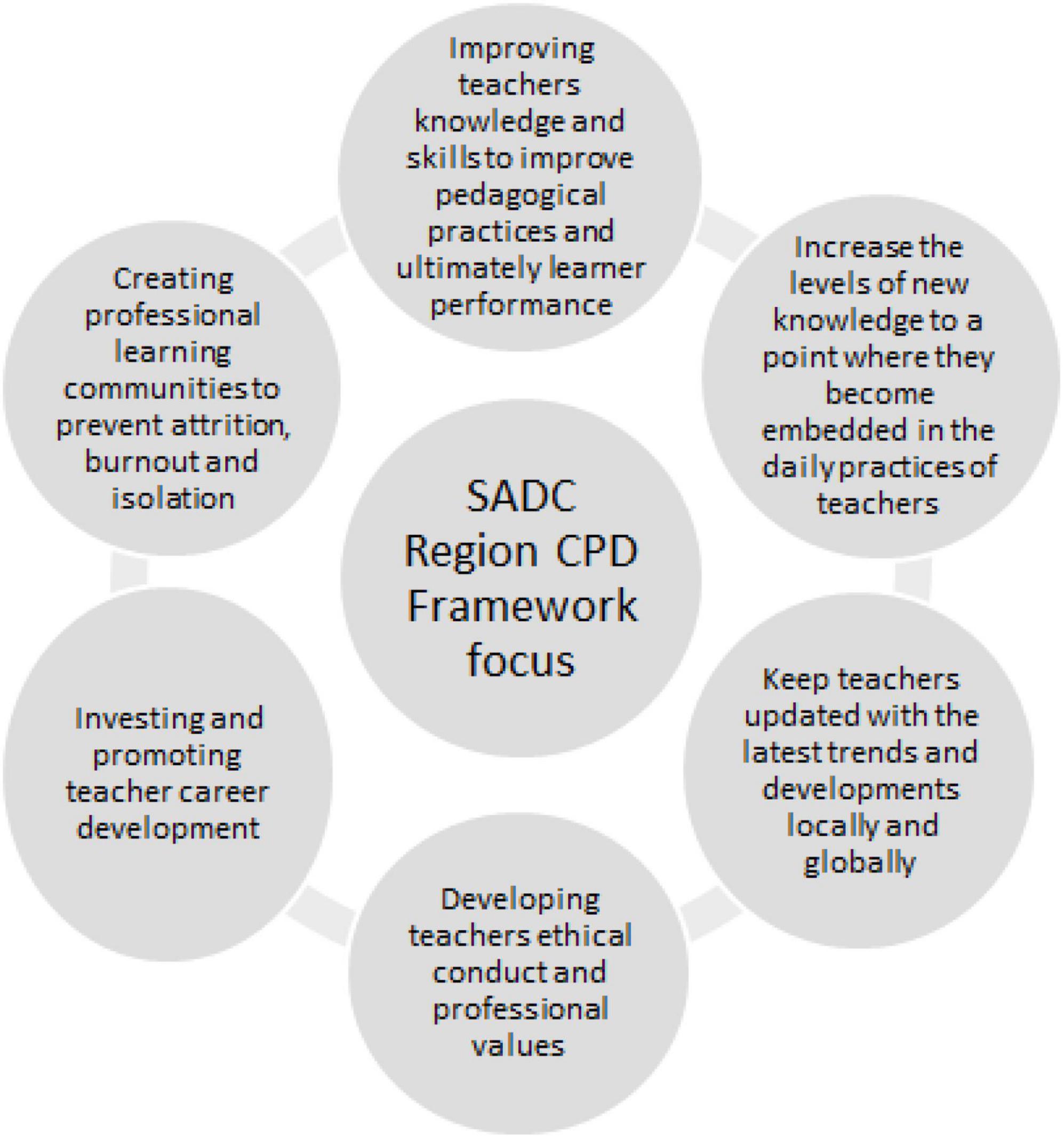

The framework is and continues to be developed in consultation with departments of education, teaching unions, teaching councils, civil society organizations, and the private sector. The framework aims to support the following functions (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Core functions supported by the SADC Regional Framework on Continuing Professional Development (CPD) for Teachers (UNESCO, 2020).

The review of CPD for teachers in the SADC region illuminates essential gaps in the professional development of teachers, which is a crucial indicator of the state of teacher support for professional development in these countries. Although there have been numerous developments instituted to improve the professional development of teachers who are currently in the classroom, these efforts are often fragmented and occur predominantly in affluent pockets, which highlights the levels of inequality within and between these education systems.

Continuous professional development in South Africa and Zimbabwe: policy frameworks and learning opportunities to promote citizenship and social cohesion in schools

South Africa

South Africa has an impressive policy landscape dedicated to the professional development of teachers. This is due to the prevailing consensus that teachers are central to transformation in a post-apartheid context. Policy frameworks in the country distinguish between the professional development of teachers and how the profession is governed. Initial teacher education is governed by the Minimum Requirements for Teacher Education Qualifications (MRTEQ) and professional development for qualified teachers is governed by the Integrated Strategic Planning Framework for Teacher Education and Development (ISPFTED). In terms of teacher governance, there are several frameworks that provide an oversight of the workload of teachers (Department of Basic Education [DBE], 2003), the roles, competencies and standards for teachers (Department of Education [DoE], 2000), evaluation of teacher performance (Department of Basic Education [DBE], 2013), and the teachers’ conditions of service (South Africa [SA], 1998), amongst others.

With regards to citizenship, social cohesion, and democracy, several policies are specifically geared toward realizing this. Firstly, the Manifesto on Values, Education and Democracy (Department of Education [DoE], 2001), which directly addresses the need to unite citizens through processes of social cohesion after many years of separate development in the country. The National Policy Framework for Teacher Education (Department of Education [DoE], 2006) employs schools to impart the necessary, skills, knowledge and dispositions to learners that promote the values of citizenship, social cohesion and democracy. More recently, the Department of Arts and Culture (2012) released a National Strategy for Developing an Inclusive and Cohesive Society and the Department of Justice (2016) released a National Action Plan to combat racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance. Both these policies advocate strongly for the values of citizenship and social cohesion to be upheld. Citizenship, social cohesion, democracy and social justice are transversal themes in most of the country’s policies. Thus, the realizing of citizenship and social cohesion is seen as a systemwide challenge, with various departments of government advocating for this, not making it the sole responsibility of the Department(s) of Education, through the institutions and the work of teachers.

From a curriculum perspective, citizenship and social cohesion are predominantly housed in a subject called “Life Orientation” or “Life Skills.” Although this subject has aspects of citizenship and social cohesion as part of its content, these values and concepts also arise in history and languages and also serve as carrier subjects. CPD for citizenship and social cohesion for teachers in the country does not meet the enthusiasm of the policy landscape. Recent training and interventions in CPD for citizenship and social cohesion include the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation’s Teaching Respect for All programme, a UNESCO initiated endeavor. Similarly, the Cape Town Holocaust Center runs a programme called “The Holocaust: Lessons for Humanity,” which emphasizes the importance of tolerance and mutual respect. The National Professional Teachers Organization of South Africa (NAPTOSA), a teacher union, also provides programmes to schools, but this is often at a fee, thus only for schools that can afford to pay. Their programme offering also provides training on teaching and learning in diverse contexts and how to achieve quality education with a values approach. Shikaya is another organization that offers various programmes all aimed at citizenship, social cohesion and social justice. Their programmes include “Facing History, Facing Ourselves” in collaboration with the USA programme of the same name; they also run the Creating Inclusive and Caring Schools Programmes, which has similar objectives. Whilst there may well be several other offerings, often at school or district level, few opportunities exist for teachers in the country and, in many cases, the CPD is delivered by an NGO which often requires payment, making access a challenge for most schools. In summary, CPD for citizenship and social cohesion in the country is fragmented, inconsistent with no cemented national offering.

Zimbabwe

In 2019, the Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education initiated discussions with various educational stakeholders, including teachers, about the need to develop a CPD Framework in the country. The intended purpose of this framework, as noted by the Ministry, is to “… guide the design and implementation of continuing professional development programmes for the teachers and learners … [and] to improve the quality of teaching and learning practices, and raise student learning outcomes at all levels of the education system … to contribute toward the attainment of the Sustainable Development Goal Four (SDG4)” (Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education, 2019, Para. 2). The need for a CPD framework also emerged from the newly instituted curriculum, launched in 2017, that now required teachers to “acquire a whole set of new competencies based on the principles” of this new curriculum (Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education, 2019, Para. 4).

The Ministry notes that it has put in place a number of effective in-service training programmes to capacitate teachers to teach the new curriculum. However, these programmes tend to be ad hoc with an overemphasis on certain subjects and an underemphasis on others. Thus, the new framework will be able to identify gaps in the development of teachers and supervisors, which should culminate in better and more impactful CPD opportunities for teachers (Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education, 2019).

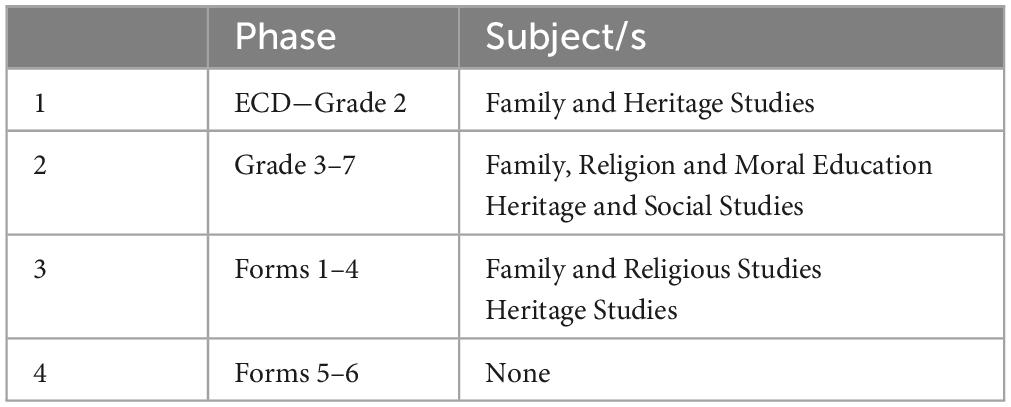

Regarding the new curriculum, between Early Childhood Education and Form 6, there is evidence of several learning areas that tend to focus on citizenship, nationhood, heritage and social cohesion. Table 1 below provides an overview of these curriculum offerings:

Table 1. Overview of specific carrier subjects for citizenship and social cohesion in the Zimbabwean Curriculum.

The recently revised Zimbabwe Education Amendment Act (2020) has also focused attention on contextual and affective challenges. For example, the Act prohibits pregnant girls from being expelled; requires schools to provide menstrual health facilities to learners; ensures that parents do not deprive their children from receiving an education; forbids corporal punishment; upholds respect for learners’ human dignity; and makes provision for schools to have infrastructure to support disabled learners. Despite all these progressive developments, there is no mention of inclusive and equitable education as a priority, despite this being a cornerstone of the SDG4.

These frameworks and amendments emphasize the state’s dedication to providing quality education and promoting the ideals of democracy−including citizenship and social cohesion. However, Hapanyengwi-Chemhuru and Shizha (2011, 108) caution that “citizenship attainment cannot be separated from the political ideology of the state”. The authors further note that the repressive nature of the current regime has led to many citizens, including teachers, avoiding engaging in policy issues and challenging the state due to fear of repercussions as noted in the extract below:

“The content knowledge required to teach pupils about alternative forms of government, democracy, freedoms and human rights and to expand their knowledge of politics beyond the politics of coercion introduced by ZANU PF is lacking in schools. While teachers might be aware of other alternative forms of government and ideologies, they are afraid of informative and critical pedagogy that frees learners from developing a narrow tunnel vision of the political and governance system in Zimbabwe. Teachers who might want to develop rational and critical thinking and analytical skills are afraid of being labeled “enemies of the state” (Hapanyengwi-Chemhuru and Shizha, 2011, 117).

This sentiment is echoed by Sigauke (2011), whose study notes that individuals rarely discuss political issues because there is suspicion that talking about politics may result in victimization. This means that, although there are policies available or currently being developed that advocate for citizenship and social cohesion, the practice of this remains a challenge. This has two implications. Firstly, it will impact how aspects of citizenship and social cohesion are taught and, secondly, it will also impact how teachers are trained to teach it. With widespread fear of speaking out against the government, teachers limit the content of their discussions about citizenship and social cohesion in the classroom which hampers the development of what Westheimer and Kahne (2004) refer to as “authentic citizens.” The authentic citizen can move beyond a passive understanding of citizenship toward a more justice-orientated position in which citizens can analyze and address social injustices. The political turmoil that occurred after the 2000s has resulted in the erosion of democracy and an increase of populist rhetoric from the ruling party justifying its position, which has silenced the public from openly voicing their views against the economic challenges and corruption in the country (Sigauke, 2019). Further to this, the current political regime disallows teachers from fulfilling their role as transforming agents by pursuing social justice. The current civics curriculum does not contain any controversial topics to ensure that teachers do not contradict the views of the state. Attempts to make human rights a standalone subject “failed due to the same reason that teachers are hesitant to teach issues they regard as politically sensitive that would get them in trouble with the ruling party” (Sigauke, 2011). The narrow view of nation building, citizenship and social cohesion is also reflected in teacher professional development, both in initial teacher education and in CPD programmes and is thus inconsistent with the true values of citizenship and social cohesion. Matereke (2012, 97) notes that this political rule renders “both the school system and teachers as mere functionaries of the status quo, thus constricting the public sphere and eroding civil liberties, these being the very elements which enable citizens to fully participate in the political process and to hold public officials and institutions accountable. It is these developments that bring the dual crisis of citizenship and education into purview.”

The overview presented here suggests that Zimbabwe’s education system, through its curriculum and teacher pedagogies, conveys a distilled version of citizenship and social cohesion to learners which can threaten a deliberative democracy and lead to passive citizenship having catastrophic social, economic and political consequences.

Methodology

This section discusses the methodologies used in procuring the data and the analysis process. It also provides an overview of each of the studies presented in this paper.

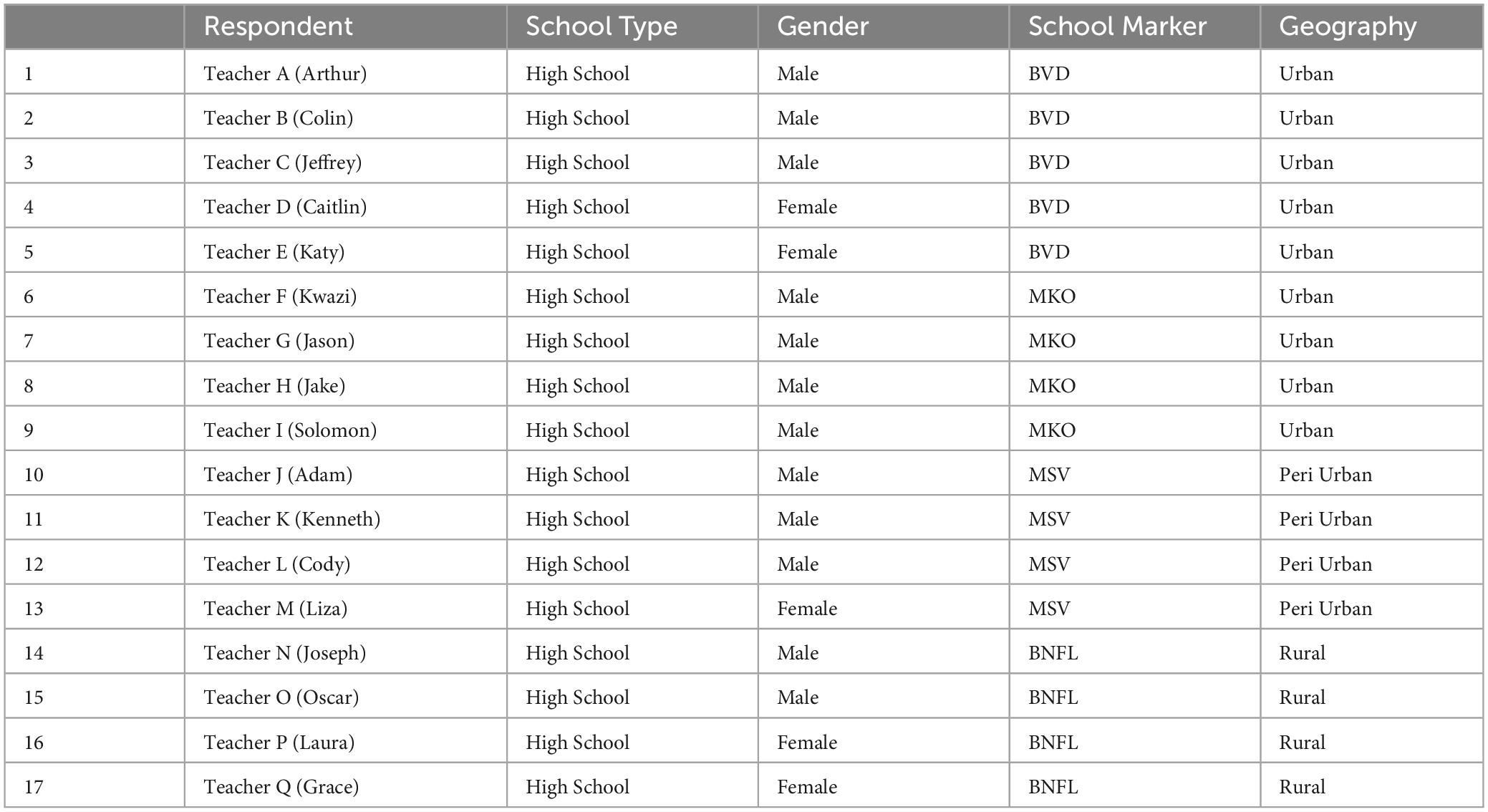

Study A: South African teachers’ understanding and practices of citizenship

The data for the first study on citizenship were part of a larger study that investigated learners’ and teachers’ understanding and experiences of citizenship in four high schools in South Africa (Singh, 2020). These four public high schools were stratified by quintile (poverty index) and geography. A total of eleven teachers participated in this study. The sample was purposive as it selected teachers who taught English, Life Orientation or History as subjects that are often noted as being carrier subjects for concepts such as citizenship and social cohesion and are often part of the curriculum. This study did not ascertain any views relating to teachers’ understanding of social cohesion as the study was citizenship-focused; as such, the findings presented will only reflect their views, practices, and CPD experiences relating to citizenship. Teachers participated in face-to-face semi-structured interviews. Each interview was recorded and then transcribed using professional transcribers. Respondents had the option of having the interview done in English, Afrikaans or isiXhosa as these were the dominant languages in the Western Cape Province. Some guiding questions included:

1. What is their understanding of citizenship and how is this depicted in practice?

2. What kind of professional development activities do teachers at the school participate in?

3. Has there been specific training on citizenship, social cohesion, or similar? Elaborate?

Table 2 below provides an overview of the respondents in Study A.

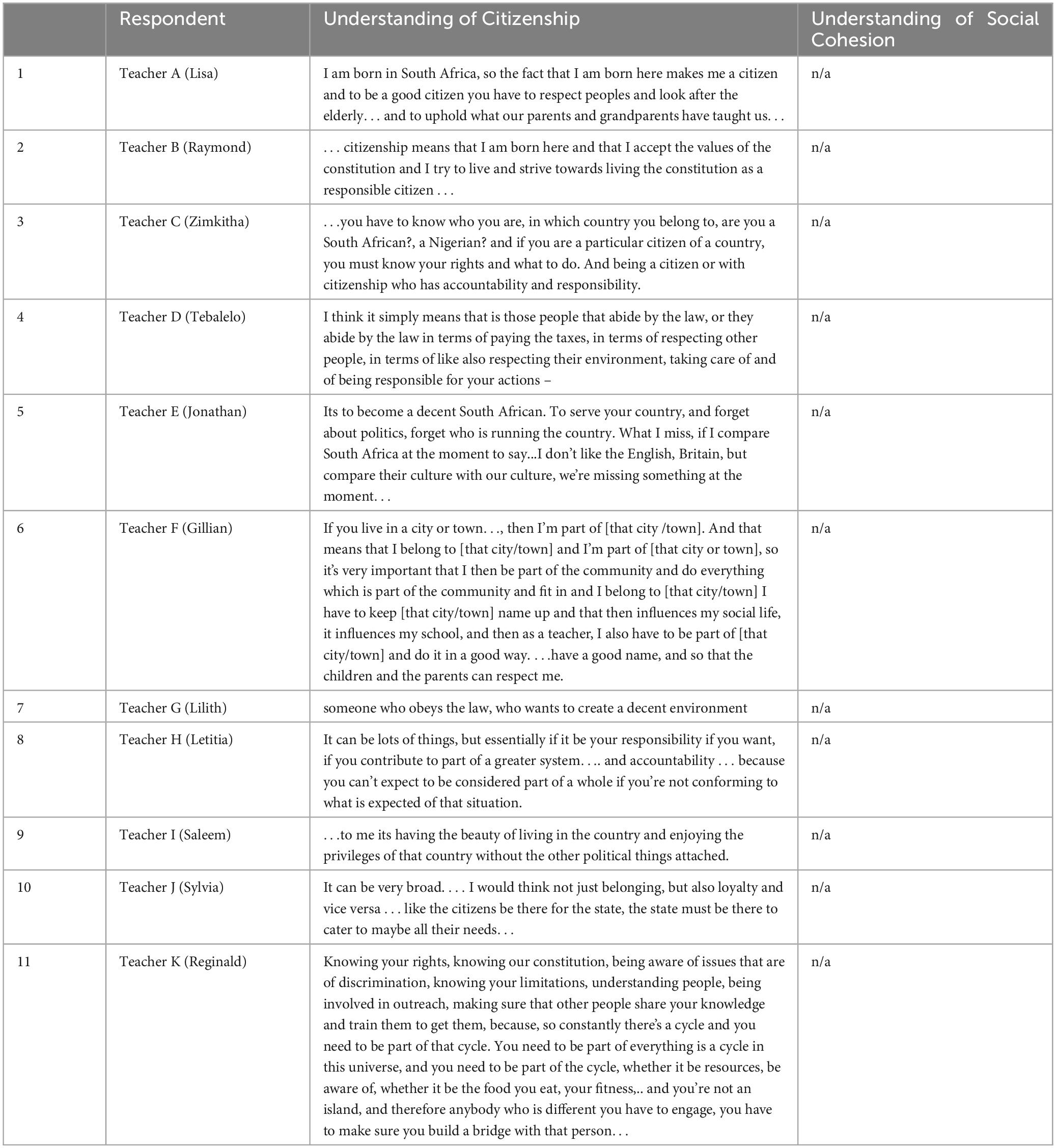

Study B: Zimbabwean teachers’ understanding and practices of citizenship and social cohesion

The Zimbabwean case study was carried out in four schools across three provinces−Harare, Midlands and Masvingo. Two schools were urban, one was rural (50 km) and the fourth was in a peri-urban (11 km) setting. This was a qualitative case study where data were generated through an open-ended questionnaire. This study sought to understand teachers’ understanding, their practices, and CPD experiences related to citizenship and social cohesion. Participants were selected through snowball sampling. One teacher was identified at each school and asked to distribute the open-ended questionnaire to their colleagues in the History department who were teaching National Social Security Studies (NASS). Seventeen secondary school teachers participated in the study. Some guiding questions for the study included:

1. What is your understanding of citizenship and social cohesion?

2. Have you received any training or staff development on citizenship and social cohesion?

3. How do you implement the values of citizenship and social cohesion in your classroom?

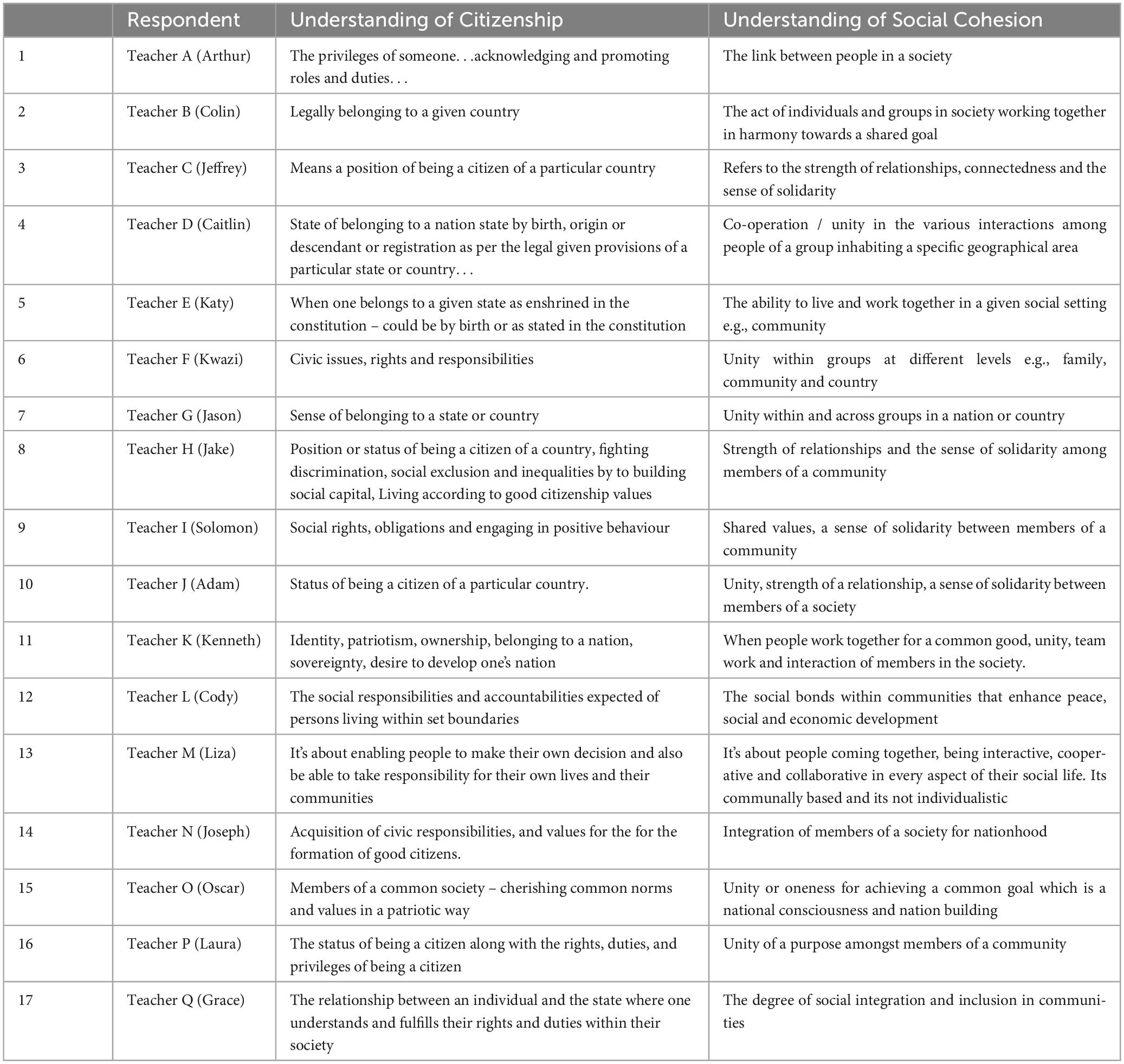

Table 3 below provides an overview of the sample for Study B:

Both studies received ethical clearances through the Cape Peninsula University of Technology Ethics Board and the South African study also received ethics through the Western Cape Education Department. At all times, the research protocol was observed, and respondents participated voluntarily. They were also informed that they could withdraw their participation at any time without fear of repercussions.

The data were analyzed using content analysis (see Patton, 2014) as this was the most effective way to ascertain keywords, themes, and concepts from qualitative data. Within the domain of content analysis, the authors selected a conceptual analysis approach as the main goal was to investigate occurrences of phrases and terms as well as incidences (Krippendorff, 2018). Further to this, content analysis was used because “qualitative content analysis is not linked to any particular science, and there are fewer rules to follow … therefore, the risk of confusion in matters concerning philosophical concepts and discussions is reduced” (Bengtsson, 2016, 8). This analytic technique was paired with Braun and Clarke’s (2006) iterative thematic analysis process for thoroughness. The authors favored qualitative techniques for this research because it “is uniquely positioned to provide researchers with process-based, narrated, storied data that is more closely related to the human experience” (Stahl and King, 2020, 26).

The data for the interviews conducted in Study A was validated through the process of triangulation, as Brown (2018) laments it is often used as a safeguard in education research to ensure the research is valid and credible. At least three teachers at each school were interviewed, which helped confirm the school context, availability of CPD, and what teachers do in the classroom.

The data for the questionnaire administered in Study B was also validated using triangulation. Teachers from various geographical contexts (urban, peri-urban, and rural) were included in the study, and all their responses, as it relates to the focus of this paper, were included in the analysis and presented in this paper. As such, all voices were included, and any outliers or inconsistencies would have been highlighted and discussed. Further to this, the questionnaires only used open-ended questions, which means respondents were not limited in how they could respond, which is often a limitation of closed-ended questionnaires.

A key difference in validation techniques between qualitative and quantitative is where the responsibility of the validation lies. In quantitative research, much emphasis is placed on having “faultless” instruments. In the context of qualitative research, the responsibility for validation and credibility lies with the researcher. Here, the work of Guba and Lincoln (1985) remains a useful checklist for establishing the trustworthiness of data. These authors contend for a research study to be evaluated as trustworthy; it needs to establish credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability (Guba and Lincoln, 1985).

Credibility refers to how “true” the findings are. In this research, teachers’ views from various schools and geographical spaces were triangulated to establish credibility. Transferability refers to the extent to which the study could be adapted for another context. Whilst qualitative research does not necessarily allow for replicability, patterns, descriptions, and experiences may be observed if the study was conducted in another context, and the findings would highly likely align. The findings of Study A and Study B align with other studies relating to teachers’ experiences of CPD and citizenship and social cohesion, such as Raanhuis (2022) and Sayed et al. (2018). Dependability refers to the accuracy of the interpretation of the findings. In this research, each author looked at and interpreted the findings, and the analysis was compared to ensure there was no intended bias in the reporting process and that the experiences and responses of participants were accurately represented. Lastly, Guba and Lincoln (1985) speak about confirmability, which refers to the degree to which the findings are shaped by the participant’s responses and not the researcher’s own bias and personal agendas. In this research, the authors ensured to follow a sound analysis of the data by using a double approach of content analysis and iterative thematic analysis. The triangulation of the findings also supports the neutrality in how the data was represented.

Findings

This section discusses the findings that responded to the following research questions:

(1) What are teachers in South Africa and Zimbabwe’s understanding of citizenship and social cohesion?

(2) Have teachers in South Africa and Zimbabwe been exposed to CPD for citizenship and social cohesion?

(3) How do teachers in Zimbabwe and South Africa incorporate the values of citizenship and social cohesion in their classroom?

Teachers’ understanding of citizenship and social cohesion

Investigating teachers’ views and understanding of citizenship and social cohesion is important because it has implications for their teaching practices. Pajares (1992) notes that the beliefs and views teachers hold influence their judgment and directly impact their behavior in the classroom. Hannula (2004) maintains that the affective dimensions that impact the quality of teaching and learning include beliefs, emotions, attitudes, values, ethics and morals. The studies on which this data was procured aimed to ascertain what teachers understood citizenship and social cohesion to mean and what values they associated with these terms. The findings that respond to the first research question are depicted in the two tables below. Table 4 depicts the responses for Study A (South Africa) and Table 5 depicts the responses for Study B (Zimbabwe).

The findings for teachers in South Africa suggest that citizenship is predominantly about belonging, as noted by Lisa, Raymond, Zimkitha, Sylvia and Gillian; about rights, as noted by Reginald; and about responsibilities, as noted by Tebalelo, Lilith and Letitia. The value of respect for others was also a recurring theme amongst participants. Sylvia’s comment suggests that her understanding of citizenship involves a social contract and a mutually beneficial relationship between the citizen and the state. The responses from Jonathan and Saleem request that one should “forget the politics, forget who is running the country” and to enjoy the privileges of the country “without the political things attached”. It is quite concerning for educators to hold these views because political participation is key to realizing full citizenship (see Marshall, 1950; Veldhuis, 1997). For Marshall (1950), citizenship, as a right, includes civil, social and political rights, the latter which require citizen engagement, not disengagement, as noted by Saleem and Jonathan. Similarly, Veldhuis (1997) notes that citizenship has four dimensions including the social, the cultural, the economic and the political with each needing to be exercised equally for citizenship to be fully realized. Whilst Jonathan and Saleem seemingly dismiss any discussion or engagement with the political element of citizenship, this could be due to the possible negative repercussions and backlash that may occur if they did engage in these discussions. This omission is of concern as schools are learning and socializing institutions and what learners learn (or don’t learn) can shape and cement the ideas and values they hold as adults. Therefore, we reiterate the importance of fostering the values of citizenship and social cohesion in schools, with CPD for teachers being one of these mechanisms to support this process.

The findings for teachers in Zimbabwe suggest that citizenship is fundamentally about belonging as noted by Caitlin, Katy, Jason, Jake, Adam, Kenneth and Oscar. Others noted that it is about roles and duties of the citizen (Kwazi, Arthur, Solomon, Cody, Joseph, Laura and Grace) as well as a relationship with the state (Grace), civil rights (Kwazi), identity and patriotism (Kenneth), inclusion (Jake) and enabling choice and decision making abilities (Lisa). Although none of the respondents overtly mentioned political engagement as key to their understanding of citizenship, it could be that their understanding of the concept may be more tangential and diverse rather than them dismissing the political dimension as important. Alternatively, teachers disengage due to the potential negative backlash. For social cohesion, all respondents noted relationships, connectedness, interaction and integration. Working toward a national consciousness and nation building (Oscar), anti-individualistic behavior (Lisa) and solidarity (Solomon, Adam) also emerged as viewpoints.

In comparison, in both studies, the manner in which citizenship and social cohesion is understood classifies these concepts as an on-going, daily, interactive process (such as respecting others, helping others, helping the elderly and the community, and being inclusive, etc.) but also as a goal to be achieved (solidarity, peace, and economic development). For both the South African and Zimbabwean teachers, the political foundations of citizenship and social cohesion are weak. This means that teachers either overtly disengage from politics, as in the case of South Africa, or subtly disengage by not mentioning this in their understanding of these concepts, as in the case of Zimbabwe.

Singh et al. (2018) argue that it is important to understand the views that teachers hold because, once known, interventions can be developed to improve practice. If teachers are disengaging from politics and transferring these disengaged views onto learners, this may lead to catastrophic consequences for enabling a democracy. Studies conducted in South Africa about the political engagement of youth found that, although youth are pro-democracy, their civic and political engagement is very low (Mattes and Richmond, 2014). Booysen’s (2015) study is also illustrative of South African youth’s views of political participation. Booysen’s study included focus groups with youth in three different provinces in South Africa about their views on political participation and revealed that learners will only vote if they “get” something in return, such as jobs. In the absence of this, they do not see the necessity. Similarly, in the study conducted by Singh (2020) learners noted that “…distrust of leadership, corruption, high levels of unemployment, poverty, and apathy as reasons why they chose to not participate politically” (p, 222–223). This was also evident in the results of the 2019 national elections, where the youth turnout was very low. Similarly, in Zimbabwe, where the 2012 National Population Census revealed that 76.1% of the population are under the age of 34 and about 68% of this group are between the ages of 15 and 34. Although being the largest demographic segment, their civic participation is very low (Future Africa Forum, 2023). The Zimbabwe Electoral Commission notes that, out of about 5.6 million registered voters, 44% constitute youth between the ages of 18 and 34. Booysen (2015) maintains that a reason for this could be due to youth social rights and basic needs that are not being met. Another explanation could be the socialization process at school where teachers do not readily engage learners about politics. This is substantiated by Willeck and Mendelberg (2021) who believe that formal education is fundamental to encouraging political participation. Several others also echo this sentiment, for example, Nie et al. (1996, 2) note that there is a consistent and overwhelming correlation between formal education and political participation of youth and that, in formal educational attainment, “the primary mechanism behind citizenship characteristics is basically uncontested”). Willeck and Mendelberg (2021, 89) mention that “the link between education and political engagement is among the most replicated and cited findings in political science” and Verba et al. (1995) state that, if scholars could use one variable to predict voting patterns, the most reliable and variable would be the level of education.

There is also an assumption that individuals who are teachers are all good and wholesome individuals who are passionate about advancing democracy. This is not the case as teachers have their own histories, life experiences, political, religious and cultural beliefs that may mitigate against the values of democracy. As such, to ensure learners are being socialized for a democratic society, teachers require focused professional development to guide this process.

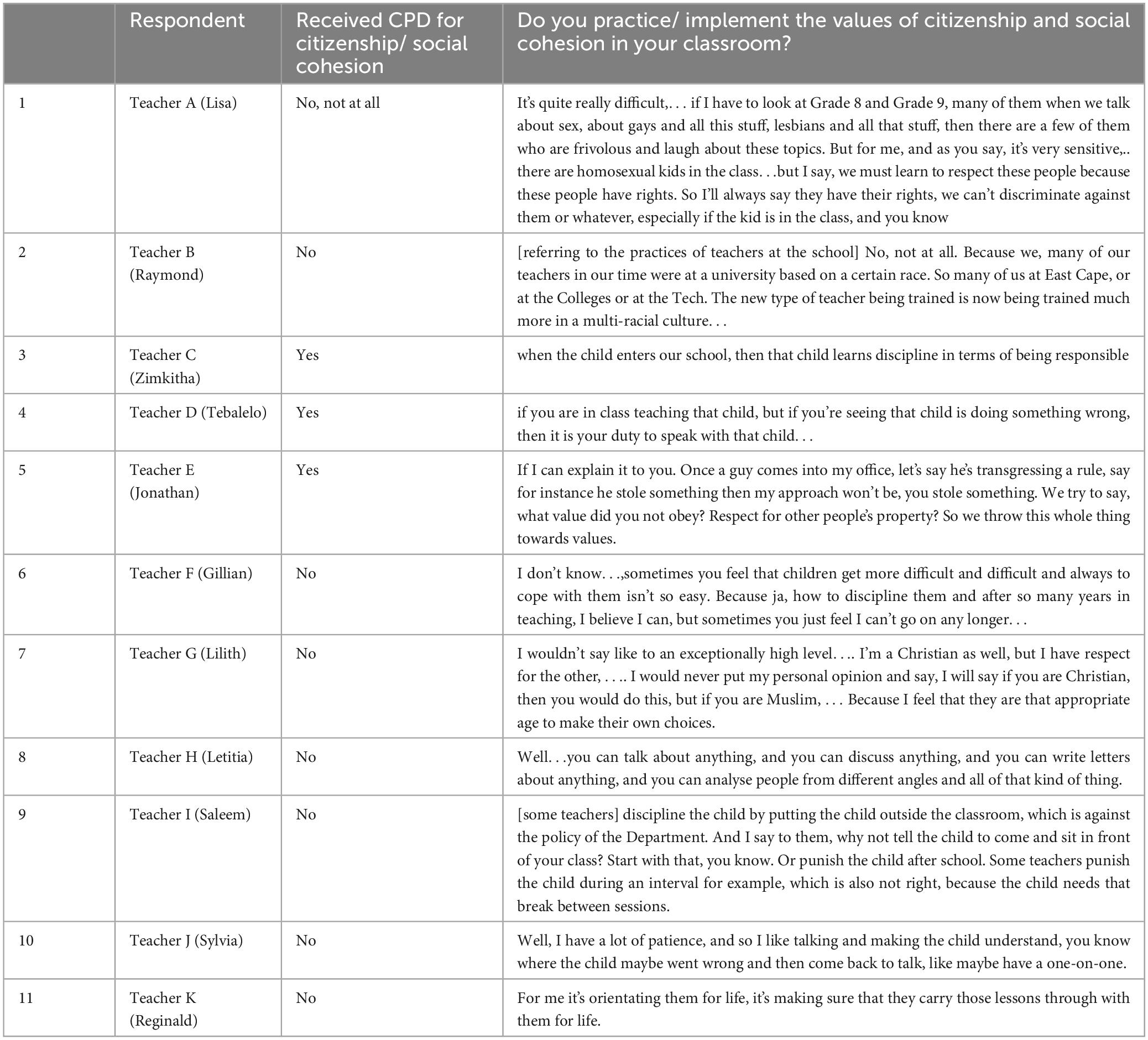

Teachers’ exposure to CPD for citizenship and social cohesion and associated classroom practices

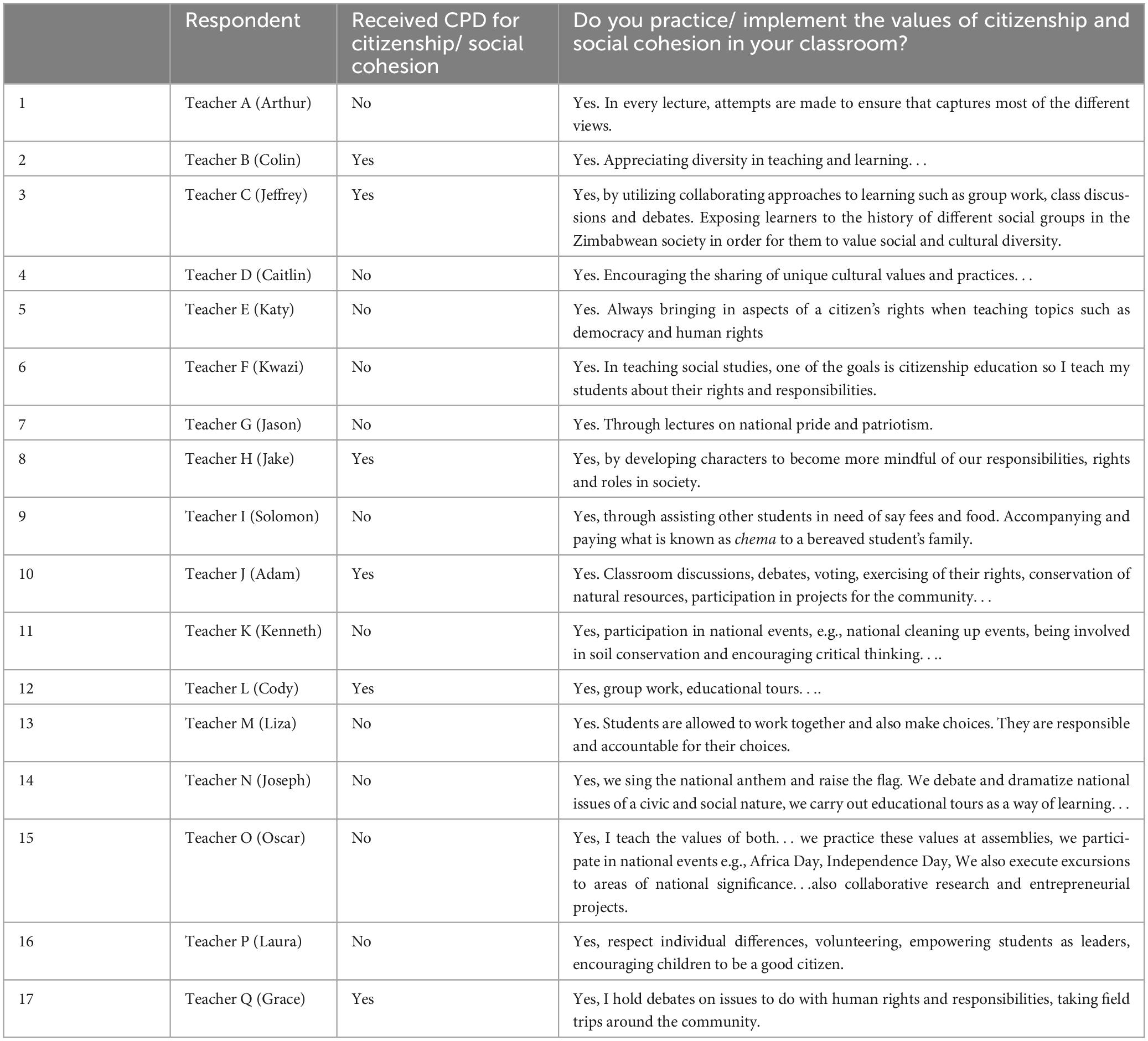

This section responds to the research questions 2 and 3 which are: “Have teachers in South Africa and Zimbabwe been exposed to CPD for citizenship and social cohesion?” and “How do teachers in Zimbabwe and South Africa incorporate the values of citizenship and social cohesion in their classroom?” Tables 6, 7 respond to these questions from Study A (South Africa) and from Study B (Zimbabwe) respectively.

Table 6. Teachers’ exposure to CPD for citizenship and their self-reported associated classroom practices (Study A).

Table 7. Teacher’s exposure to CPD for citizenship and social cohesion and their self-reported associated classroom practices (Study B).

The findings from the South African teachers demonstrate that, out of the eleven teachers, only two teachers (from an urban, quintile one school) noted that they had received CPD that focused on citizenship. Most of the teachers had not received any form of CPD on these topics. However, when teachers were asked whether they teach in a manner that promotes the values and practices of citizenship, all the responses were positive and examples of these strategies were provided. For example, one teacher explained that fostering tolerance in her class is her way of enacting these values (Lisa), others noted that it is enacted through positive disciplining techniques (Saleem, Zimkitha, Tebalelo, Jonathan and Sylvia), and Reginald believed in creating a class environment that allows learners to develop life skills. These pedagogical and classroom practices are essential for socializing learners toward enacting the democratic values. Goren and Yemini (2017) suggest that the characteristics and the approach of the adults involved in this socialization can determine the degree to which youth participate in public discourses and imbibe the values of citizenship and social cohesion. As such, all teachers, regardless of the subject, need to be consistently trained to ensure their classroom practices and pedagogies are consistent with the values of citizenship and social cohesion as their own understandings and views of these concepts may be misaligned. Although CPD is only one way of challenging teachers’ beliefs, it becomes impactful if the CPD is consistent.

The findings from Study B demonstrate that, of the 17 teachers, only six noted that they had received CPD focused on citizenship and social cohesion. In this case, all teachers responded positively when asked whether they implement the values of citizenship in their classrooms. The methods used included: considering multiple viewpoints (Arthur); using a collaborative teaching style; having debates and encouraging discussions (Jeffery, Adam, Lisa); national pride and patriotism (Jason); and participating in national events and educational tours (Kenneth, Cody).

This shows that teachers are implementing their understanding of citizenship and social cohesion in the classroom, informed by their own beliefs and views and not necessarily formal training. This begs the question: Are these teachers’ enacting values that are consistent with the values of democracy or are they perpetuating behaviors that encourage silencing of voices? A study by Leek (2019) also suggests that teachers themselves recognize the importance of being trained in the effective dimensions of teaching and learning to encourage youth to become more active citizens. Leek’s (2019, 181) study notes that “the teachers expressed their concern about the lack of training on a whole spectrum of civic participation, including classroom psychology [and noted that] the times are changing, and the youth changes over time too, so each generation has different needs as far as teaching is concerned. [As] a result, the teachers need to update their teaching methods accordingly and knowledge of how to teach in general.”

For learners to become active citizens who utilize their agency and embody the values of citizenship and social cohesion, one or two lessons a week on values and society from the civics curriculum is not sufficient. Learners need these values to pervade every aspect of their schooling lives, facilitated by teachers who are professionally trained and equipped to do so.

This section discussed the findings that respond to the three research questions as noted earlier in this paper. The next section concludes the paper by summarizing the two studies, noting the contribution and limitation of the study, synthesizing the main findings, and reiterating the importance of teachers receiving consistent, good quality CPD on affective concepts such as citizenship and social cohesion in order to build and support a flourishing democracy.

Conclusion

The aim of this paper was to illuminate South African and Zimbabwean teachers understanding of citizenship and social cohesion, their experiences of CPD relating to these concepts as well as the ways in which they implement these concepts in their classrooms. This paper is a reflection on and a response to the dire political challenges and inefficiencies experienced in these nations, where democracy is being threatened and its values are eroding. Teachers remain beacons of hope in these challenging times as their agentic nature is catalytic in socializing youth about democracy. However, when teachers are silenced and threatened through political interference, limiting how and what they can and cannot discuss in the classroom, democracy is undermined and weakened. The findings draw from two separate studies. The findings from the South African case draw from a larger study investigating learners’ and teachers’ understandings and experiences of citizenship in South Africa, where the discussion of CPD was a subset (see Singh, 2020). This study only focused on the concept of citizenship, not social cohesion, and is presented in this paper as such. The Zimbabwean case draws on a study that investigated teachers’ understanding of citizenship and social cohesion, their experiences of CPD relating to this, and the ways in which they implement this in their classrooms. A critical limitation of the study is that in some instances, the instruments posed leading questions. This limitation was overcome by ensuring the analysis was more nuanced, acknowledging that it is quite possible that a differently phrased question may yield a different response.

Nonetheless, the findings demonstrate that in these studies, both South African and Zimbabwean teachers’ understanding of citizenship promotes the ideals of the “Responsible Citizen” (see Westheimer and Kahne, 2004), who privilege the ideals of respect for each other and the environment. Teachers in both counties also find belonging to be an important aspect. Teachers avoid discussing politics and, in some instances, note that one should “forget the politics and forget who is running the country,” demonstrating either their political disengagement with the state or fear of discussing politics due to the possible negative repercussions. For the teachers in Zimbabwe, social cohesion is about solidarity, togetherness, patriotism, integration, unity and cooperation. Most teachers in these studies had not received training on citizenship or social cohesion. However, all teachers declared that they teach in a way that is consistent with their views of citizenship and social cohesion. Both countries have evidence of policies that promote the values of citizenship and social cohesion, with South Africa’s landscape being the more sophisticated of the two, but the offering for CPD does not meet policy objectives in practice. Reasons for the inconsistent and fragmented offering of CPD for citizenship and social cohesion include financial challenges, departmental capacity and political interference.

Teachers need to receive focused CPD on understanding and enacting the values of citizenship and social cohesion in the classroom because schools, through teachers, exercise a particular influence on the development of young people’s democratic knowledge and political literacy skills (Kisby and Sloam, 2014). Learners in South Africa and Zimbabwe have the right to be taught the full meaning of citizenship and social cohesion and to understand the practices associated with this. By doing so, they will know when democracy and democratic values are not being upheld. Well-trained and suitably equipped teachers are a critical factor to realize this because quality teachers beget quality education systems. Raanhuis (2021, 44) reiterates this by saying that “teachers in all contexts should be supported as agents of change, through CPD”. Thus, professional development for teachers, particularly in post-conflict and post-colonial states, becomes an issue of social justice and is critical in creating deliberative democracies.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Cape Peninsula University of Technology Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

MS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing−original draft, Writing−review and editing. TM: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing−original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of the article. This research would not have been possible without the funding of the National Research Foundation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Allender, J., and Allender, D. (2006). “How did our early education determine who we are as teachers?,” in Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices, eds L. M. Fitzgerald, M. L. Heston, and D. L. Tidwell (Cedar Falls, IA: University of Northern Iowa), 14–17.

Araujo, M. C., Carneiro, P., Cruz-Aguayo, Y., and Schady, N. (2016). Teacher quality and learning outcomes in kindergarten. Q. J. Econ. 131, 1415–1453.

Barolsky, V. (2016). Is social cohesion relevant to a city in the global South? A case study of Khayelitsha Township. S. Afr. Crime Q. 55, 17–30. doi: 10.17159/2413-3108/2016/i55a753

Bell, L. A. (2007). “Theoretical foundations for social justice education,” in Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice, eds M. Adams, L. A. Bell, and P. Griffin (London: Routledge), 1–14.

Bengtsson, M. (2016). How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open 2, 8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.npls.2016.01.001

Booysen, S. (2015). Youth and Political Participation in South Africa’s Democracy: Surveying the Voices of the Youth Through a Multi-Province Focus Group Study. Washington, DC: Freedom House.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brown, J. (2018). “Qualitative research design: Principles, choices and strategies,” in Building Research Design in Education: Theoretically Informed Advanced Methods, eds L. Hamilton and J. Ravenscroft (London: Bloomsbury), 71–86.

Connell, R. (2014). Using southern theory: Decolonizing social thought in theory, research and application. Plan. Theory 13, 210–223. doi: 10.1177/1473095213499216

Cuellar, R. (2009). Social Cohesion and Democracy. Stockholm: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance.

De Sousa Santos, B. (2014). Epistemologies of the South: Justice against Epistemicide. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

Department of Arts and Culture (2012). National Strategy for Developing an Inclusive and Cohesive Society. Ariyalur: Department of Arts and Culture

Department of Basic Education [DBE] (2003). Personnel Administrative Measures (PAM). Available online at: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/202209/46879gon2468.pdf (accessed February 21, 2003).

Department of Basic Education [DBE] (2013). Quality Management System [QMS] for school based educators: Principals’ Association Meeting 21 Feb. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education

Department of Education [DoE] (2001). Manifesto on Values, Education and Democracy. Pretoria: Department of Education.

Department of Education [DoE] (2006). The National Policy Framework for Teacher Education and Development in South Africa: More Teachers, Better Teachers. Pretoria: Department of Education.

Department of Justice, (2016). National Action Plan to Combat Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance. Available online at: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201903/national-action-plan.pdf (accessed January, 2023).

Future Africa Forum (2023). Low Youth Participation: A Ticking Time Bomb For Zimbabwe’s Future. Nairobi: Future Africa Forum

Gavin, M. (2022). Trouble Ahead in Zimbabwe: Zimbabwe’s worsening social, political, and economic landscape means trouble for the Southern Africa subregion. Available online at: https://www.cfr.org/blog/trouble-ahead-zimbabwe (accessed June 1, 2022).

Goren, H., and Yemini, M. (2017). The global citizenship education gap: Teacher perceptions of the relationship between global citizenship education and students’ socio-economic status. Teach. Teacher Educ. 67, 9–22.

Grignon, F. (2008). Tanzania Must Help end Zimbabwe’s Military Dictatorship. Brussels: International Crises Group.

Hannula, M. S. (2004). Affect in Mathematics Education. Annales Universitatis Turkuensis B 273. Finland: University of Turku.

Hapanyengwi-Chemhuru, O., and Shizha, E. (2011). “Citizenship Education in Zimbabwe,” in Education and Development in Zimbabwe, eds E. Shizha and M. T. Kariwo (Leiden: Brill), 107–121.

Howell, C., McKenzie, J., and Chataika, T. (2018). “Building teachers’ capacity for inclusive education in South Africa and Zimbabwe through CPD,” in Continuing Professional Teacher Development in Sub-Saharan Africa: Improving Teaching and Learning, ed. Y. Sayed (London: Bloomsbury Academic), 127–148.

Kisby, B., and Sloam, J. (2014). “Promoting youth participation in democracy: The role of higher education,” in Beyond the Youth Citizenship Commission: Young People and Politics, eds A. Mycock and J. Tonge (London: Political Studies Association), 52–56.

Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Leek, J. (2019). Teachers’ perceptions about supporting youth participation in schools: Experiences from schools in England, Italy and Lithuania. Improv. Schl. 22, 173–190. doi: 10.1177/1365480219840507

Manca, A. R. (2014). “Social cohesion,” in Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research, ed. A. C. Michalos (Dordrecht: Springer), doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_2739

Matereke, K. P. (2012). ‘Whipping into line’: The dual crisis of education and citizenship in postcolonial Zimbabwe. Educ. Philos. Theory 44, 84–99.

Mattes, R., and Richmond, S. (2014). Are South Africa’s Youth Really a “Ticking Time Bomb”?. Cape Town: University of Cape Town

Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education (2019). Continuing Professional Development Framework for Teachers and Supervisors. New Delhi: Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education

Nie, N. H., Junn, J., and Stehlik-Barry, K. (1996). Education and Democratic Citizenship in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Pajares, M. F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Rev. Educ. Res. 62, 307–332.

Patton, M. Q. (2014). Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Popova, A., Evans, D. K., Breeding, M. E., and Arancibia, V. (2022). Teacher professional development around the world: The gap between evidence and practice. World Bank Res. Observer 37, 107–136. doi: 10.1093/wbro/lkab006

Raanhuis, J. (2021). Empowering teachers as agents of social cohesion: continuing professional development in post-apartheid South Africa. Pol. Pract. 33, 28–51.

Raanhuis, J. (2022). Teachers’ Views of Continuing Professional Development Related to Social Cohesion in the Western Cape, South Africa. Cape Town: Cape Peninsula University of Technology.

Rudiger, A., and Spencer, S. (2004). “Meeting the challenge: Equality, diversity and cohesion in the European Union,” in Paper Presented to the Joint European Commission/OECD Conference on The Economic Effects and Social Aspects of Migration, (Brussels).

SADC and UNESCO (2019). SADC Regional Framework for Teacher Professional Standards and Competencies. Gaborone: SADC.

Sayed, Y., Azeem, B., Yusus, O., Eugene, N., Mario, N., Naureen, D., et al. (2018). The Role of Teachers in Peacebuilding and Social Cohesion in Rwanda and South Africa: Synthesis Report. Rwanda: ESRC/DFID.

Sayed, Y., and Bulgrin, E. (2020). Teacher Professional Development and Curriculum: Enhancing Teacher Professionalism in Africa. Belgium: About Education International.

Sigauke, A. T. (2011). Political ideas can only be discussed if they are in the syllabus; otherwise a political discussion is not necessary: Teachers’ views on citizenship education in Zimbabwe. Citizensh. Teach. Learn. 6, 269–285. doi: 10.1386/ctl.6.3.269_1

Sigauke, A. T. (2019). “Citizenship and citizenship education in Zimbabwe: A theoretical and historical analysis,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Citizenship and Education, eds A. Peterson, G. Stahl, and H. Soong (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 243–257. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-67905-1_42-1

Singh, M. (2020). Citizenship in South African Schools: A Study of Four High Schools in the Western Cape. Cape Town: Cape Peninsula University of Technology.

Singh, M., Wessels, H., and Kanjee, A. (2018). “Beliefs about professional knowledge,” in Learning to Teach in Post-Apartheid South Africa: Student teachers’ Encounters with Initial Teacher Education, eds Y. Sayed, N. Carrim, A. Badroodien, Z. McDonald, and M. Singh (Stellenbosch: African Sun Media), 73–105.

Stahl, N. A., and King, J. R. (2020). Expanding approaches for research: Understanding and using trustworthiness in qualitative research. J. Dev. Educ. 44, 26–28.

UNESCO (2020). DRAFT SADC Regional Framework on Continuing Professional Development (CPD) for Teachers. Paris: UNESCO

Veldhuis, R. (1997). Education for Democratic Citizenship: Dimensions of Citizenship, Core Competencies, Variables, and International Activities. France: Council for Cultural Cooperation.

Verba, S., Schlozman, K. L., and Brady, H. E. (1995). Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Westheimer, J., and Kahne, J. (2004). What kind of citizen? The politics of educating for democracy. Am. Educ. Res. J. 41, 237–269.

Willeck, C., and Mendelberg, T. (2021). Education and political participation. Annu. Rev. Pol. Sci. 25, 89–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-051120-014235

Zimbabwe Education Amendment Act (2020). Gazetted on the 6th March 2020. Available online at: https://www.veritaszim.net/sites/veritas_d/files/EDUCATION%20AMENDMENT%20ACT%2C%202019%20%5B%20Act%2015-2019%5D_0.pdf (accessed March 6, 2020).

Keywords: continuous professional development, citizenship, social cohesion, pedagogy, South Africa, Zimbabwe, deliberative democracy

Citation: Singh M and Mukeredzi T (2024) Teachers’ experiences of continuous professional development for citizenship and social cohesion in South Africa and Zimbabwe: enhancing capacity for deliberative democracies. Front. Educ. 9:1326437. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1326437

Received: 23 October 2023; Accepted: 29 January 2024;

Published: 23 February 2024.

Edited by:

Jaime Ibáñez Quintana, University of Burgos, SpainReviewed by:

Caroline Kuhn, Bath Spa University, United KingdomAjay Singh, University of Hail, Saudi Arabia

Copyright © 2024 Singh and Mukeredzi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marcina Singh, bWFyY2luYS5yZXNlYXJjaEBnbWFpbC5jb20=; bWFyY2luYXNAdWouYWMuemE=

Marcina Singh

Marcina Singh Tabitha Mukeredzi2

Tabitha Mukeredzi2