- 1Department of Health Professions Education, National University of Medical Sciences, Rawalpindi, Pakistan

- 2Department of Anatomy, Shifa College of Medicine, Shifa Tameer-e-Millat University, Islamabad, Pakistan

- 3Department of Health Professions Education, Shifa College of Medicine, Shifa Tameer-e-Millat University, Islamabad, Pakistan

- 4Department of Biochemistry, Islamic International Medical College, Riphah International University, Rawalpindi, Pakistan

Introduction: Teachers can perceive themselves as a true teacher and act as one only if they have a strong professional identity. This study aimed to identify factors that shape the unique professional identity of basic medical sciences teachers in Pakistan.

Methods: A qualitative study was performed using the concepts of phenomenology and purposive sampling. A 20-item text-based interview was conducted by sharing a Google Form link with basic medical sciences teachers from select institutions. Iterative data collection and analysis were performed until data saturation was attained.

Results: A total of 40 participants took part in the study. Nine categories were identified and grouped into two major themes: four personal and five environmental factors. Personal factors included characteristics, preferences, religious values, and professional development. Environmental factors included community of practice, students' feedback, administrative support, work environment, and societal apathy. Among these factors, aptitude, family preference or work-life balance, hard work, dedication, and effect on parenting were more evident in women. By contrast, passion, experience, complacency, and unique identity were the prominent factors.

Discussion: Community of practice [31 (77%)], passion for teaching [21 (52%)], students' feedback [18 (45%)], work-life balance [16 (40%)], and religious values [13 (32%)] were the primary positive contributors to the identity of basic medical sciences teachers. By contrast, poor administrative support [8 (20%)], negative work environment [11 (27%)], job dissatisfaction [7 (17%)], societal apathy [4 (10%)], and lack of opportunities for professional growth [6 (15%)] negatively impact the professional identity of basic medical sciences teachers.

Introduction

Professional identity formation is a complex and unique process that evolves through tacit knowledge acquisition, societal and cultural values, role models, mentorship, self-reflection, and experiences (Ryan et al., 2022).

The concept of professional identity is not novel. Since Hippocrates, physicians, teachers, and other occupations have acquired and demonstrated their respective identities (Cruess et al., 2014). In 1957, Merton stated, “task of medical education is to shape the novice into a medical practitioner, to give him the best available knowledge and skills, and to provide him with a professional identity so that he comes to think, act, and feel like a physician” (Merton and Reader, 1957).

Professional identity in the medical field is fostered in three parts. In the initial part, factors such as family, friends, culture, sex, religion, and race play their role. In the second part, training begins at medical school entry and next at the start of residency or clinical practice. In the third part, professional culture and the learning environment play a pivotal role (Sarraf-Yazdi et al., 2021). Thus, professional identity develops within the context of individual characteristics of preformed personal identities, continuously shaped by social and cultural values. This process transforms physicians into the professionals they become, evidenced by their attitudes in the workplaces (Ibarra and Barbulescu, 2010; Cantillon et al., 2019).

The social status of doctors encourages parents to persuade their children to enter the medical profession from an early age (Wong and Trollope-Kumar, 2014). In Pakistan, 70% of medical students are women. Among them, 50% do not pursue a career in the physician workforce. Pakistani parents actively guide their daughters toward the medical field because they view it as a means to obtain favorable marriage prospects and perceive a medical degree as a “safety net” in case the marriage fails rather than as a pathway to a medical profession. Moreover, in a Pakistani household, a woman's career is significantly influenced by her husband and his family. Therefore, female doctors face a conflict between their traditional role as homemakers and the professional role as physicians (Moazam and Shekhani, 2018).

In the past two decades, the number of private medical and dental colleges in the country has rapidly increased. Currently, a total of 185 medical institutions, comprising 124 medical colleges (48 public, 76 private) and 61 dental colleges (18 public, 43 private) are registered with Pakistan Medical and Dental Council (PMDC). This development has created numerous job opportunities and career pathways, benefitting individuals who may have otherwise perceived a career in medicine as challenging. Within a larger community of practice (CoP) of doctors, smaller specialist communities exist (Cruess et al., 2019; Orsmond et al., 2022). Teachers in basic medical sciences form their own distinct CoP while being part of a wider medical CoP. Their personality, behavior, and aura (i.e., the distinctive environment that surrounds a person) are distinct from clinical teachers probably because of the differences in their work environment and experiences from those of clinicians.

A medical teacher's identity is critical because it has a powerful effect on the teacher's choices regarding academic roles and responsibilities, career trajectories, motivation, satisfaction, and professional development opportunities (Cantillon et al., 2019). Teachers' identity is defined as their perception of themselves as a teacher. Evidence shows that teachers with a strong identity find joy in their teaching role, stay employed, and exhibit a greater willingness to invest in their professional learning (van Lankveld et al., 2021). Therefore, to achieve excellence in teaching, faculty members must embrace their identities as teachers with the support of their professional peers (Steinert et al., 2019).

Medical teachers play multifaceted roles at their workplaces, including that of educators, researchers, counselors, examiners, and administrators (Steinert, 2014). These roles must be developed during the training period and enhanced through faculty development (Guraya and Chen, 2019). However, little is known about a medical teacher's professional identity or how it (Cruess et al., 2019) is formed, which is central to the aforementioned roles. Research regarding the formation of the professional identity of medical teachers is almost non-existent in Pakistan.

For medical education to make an impact, it is imperative to understand factors that shape the professional identity of medical teachers by recognizing sociocultural learning and evolving interactions (Orsmond et al., 2022) within the CoP, comprising students, educators, professional peers, and organizational leadership. Therefore, we aimed to identify how the professional identity of basic medical sciences teachers is shaped and to determine factors that contribute to the increasing number of women (feminization) in this profession in Pakistan.

Materials and methods

Context

This study was conducted in Pakistan, which has a population of ~230 million, ranking fifth among the most populous countries of the world. It has the world's second-largest Muslim population, distributed across a vast area of 881,913 km, having diverse historical, geographical, and political history with a varied cultural and ethnic background. It has been politically unstable for most of its history; however, citizens continue to show strong resilience in the face of continuous challenges of poverty, illiteracy, corruption, and terrorism.

In Pakistan, medical schools offer a curriculum spanning over 5 years for medicine and 4 years for dentistry. The initial 2 years cover the basic health sciences, including anatomy, biochemistry, and physiology. During the third year, students are taught pharmacology, community medicine, and pathology as basic science subjects. Meanwhile, students are gradually exposed to clinical rotations at affiliated teaching hospitals. Educators who teach medical students in their initial undergraduate years are called basic medical sciences teachers. These teachers do not typically engage in clinical practice, which may be because they are prohibited from it, for which they may receive a non-practicing allowance, or because their busy schedule and multiple responsibilities at workplace prevent them from engaging in clinical practice.

Setting and duration of the study

This study was conducted in colleges affiliated with the National University of Medical Sciences from February to July 2023. With nine medical (one public, eight private) and three dental (one public, two private) colleges under its umbrella, the total number of basic medical sciences faculty was over 1500. The faculty is highly qualified and has experience working in various private and public institutions across the country.

Study design and sampling

This exploratory study was based on phenomenology, which is an appropriate choice for the research aimed at explaining a process by exploring a phenomenon through participants' lived experiences. The theoretical perspective underlying this study is interpretivism, wherein the knowledge and meaning shared by the researcher, participants, and the world around them are interpreted to construct reality. The theoretical process of sampling was completed, i.e., the study sample was not finalized before starting data collection, but participants were selected purposively as the analysis progressed (Creswell and Miller, 2000; Merriam and Tisdell, 2015).

Data collection tool

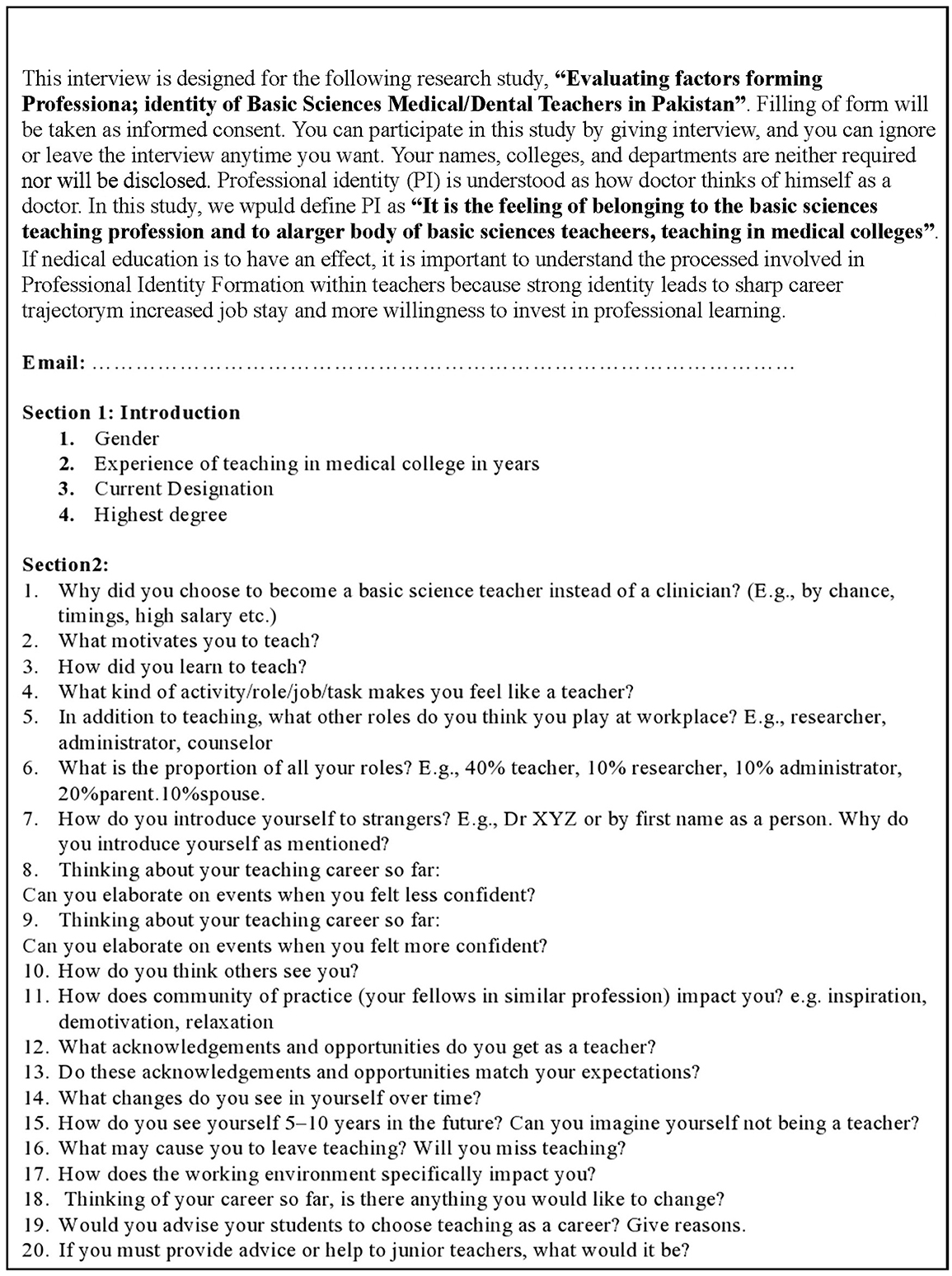

As the geographical distance was superfluous, responses needed elaborated reflections and sensitive personal views. Therefore, instead of conducting face-to-face interviews, we decided to conduct online, open-ended, text-based interviews (Saarijärvi and Bratt, 2021). A 20-item text-based interview questionnaire was designed, pilot-tested on five participants, finalized, and uploaded online using Google Forms (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Text-based interview questions of basic medical sciences teachers in Pakistan via google form.

Study design and data collection

This qualitative study design was based on phenomenology in which information on the lived experiences of participants was gathered by sharing the Google Form link that comprised the text-based interview questionnaire with the participants. Phenomenology provided valuable insights into the phenomenon of professional identity formation and feminization of the profession, influenced by the specific context and culture (Merriam and Tisdell, 2015). Participation was purely voluntary; therefore, responding to the interview was considered as participants' informed consent. Later, certain responses that required clarification were further explored via phone calls and/or WhatsApp.

Sampling and participants' characteristics

Purposive sampling was obtained. This study included all the basic medical sciences faculty members who had a minimum of 18 years of education, were working at the level of assistant professor or above, had a minimum experience of 3 years, received the Google Form link with the description of the study, and responded to the interview. The study excluded all those who met the abovementioned criteria but did not respond to the interview.

Sample size

Participants were recruited iteratively until data saturation was achieved at the 40th participant, with further data collection eliciting no new categories, theoretical insights, or any additional properties of the identified core categories (Merriam and Tisdell, 2015).

Data analysis

Closed-ended questions employed descriptive statistics, whereas qualitative data was analyzed in seven phases to achieve trustworthiness (Creswell and Miller, 2000; Merriam and Tisdell, 2015).

Thick description

Initially, the process started by reading the interview transcripts to gain familiarity with the content and context within the text-based data. In the second phase, meaningful phrases from the text were captured and initial codes were generated. After coding a portion of the data, the codes were reviewed to check if they accurately captured the information. In the third phase, codes were assigned to the entire dataset, systematically identifying patterns, categories, and themes emerging from the data. Subsequently, all relevant coded data excerpts were collected, organized, and categorized. In the fourth phase, the extracted data were re-read to comprehend the newly extracted data relevant to the research objectives, and the experiences were reviewed and reorganized into two main themes: personal and environmental. In the fifth phase, the extracted data were re-read iteratively. Next, the categories and themes were defined and refined, ensuring an accurate representation of the content of the data. A visual representation (diagram) of codes, categories, and themes was created to depict their relationship. In the sixth phase, a consensus on categories and themes was reached and finalized after discussion. Next, researchers were triangulated. An in-depth analysis of the categories was performed, considering the relationships between codes and categories that culminated into two overarching themes, clarifying the significance of each and how they align with the research question. The analysis was documented, elucidating the categories under each theme, and meaning and relevance of these categories and themes to the research. The quotes and excerpts from the data were used to support the findings. In the seventh phase, some of the participants were contacted via WhatsApp to clarify certain interpretations, a process known as member checking. The corresponding reflective opinions were rephrased following the discussion (Creswell and Miller, 2000; Merriam and Tisdell, 2015).

Audit trail

To minimize inaccuracies and to visualize the processing of raw data into final themes, process logs were maintained to form an audit trail (Merriam and Tisdell, 2015).

Reflexivity

Reflexivity was managed by taking the following measures: The interviews were conducted asynchronously. Instead of direct interaction with participants, the online Google Form link to the text-based structured interview was sent (Saarijärvi and Bratt, 2021), which provided them ample time to contemplate and reflect before answering questions. Participants' anonymity was maintained by assigning identifiers before reading their responses and quoting their excerpts (Olmos-Vega et al., 2022).

Results

Descriptive statistics

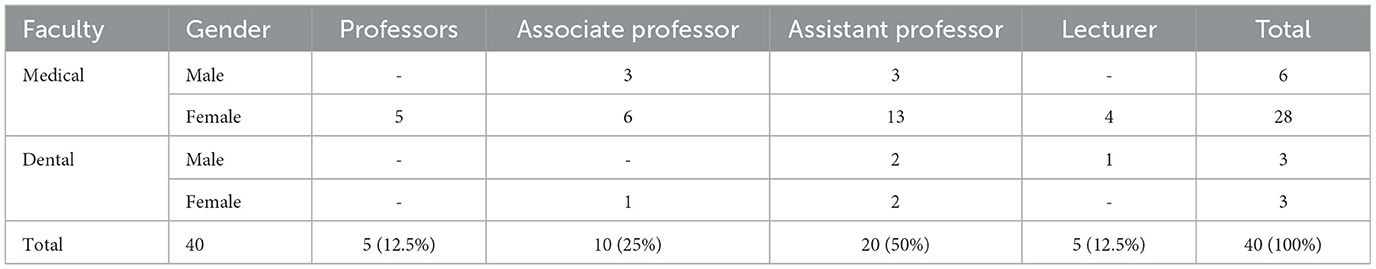

A total of 40 teachers participated in the study; 34 were from the medical faculty and 6 from dental.

Of the total respondents, 9 (22%) were men and 31 (78%) were women (see Table 1). Most had a Master's degree [33 (84%)], whereas a few had PhD or equivalent [7 (16%)].

Themes and sub themes

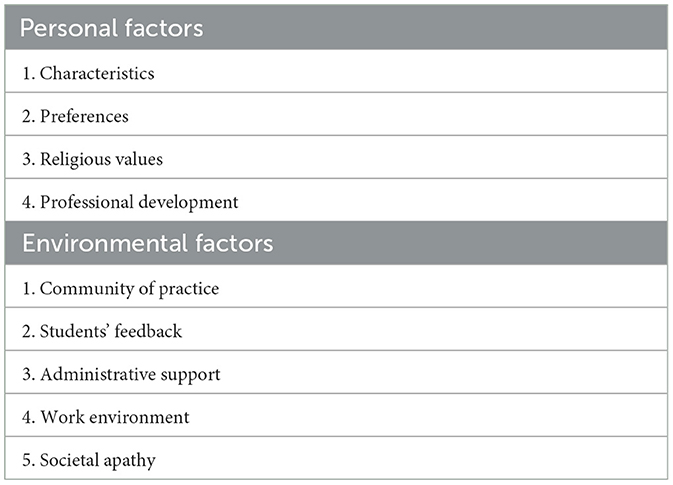

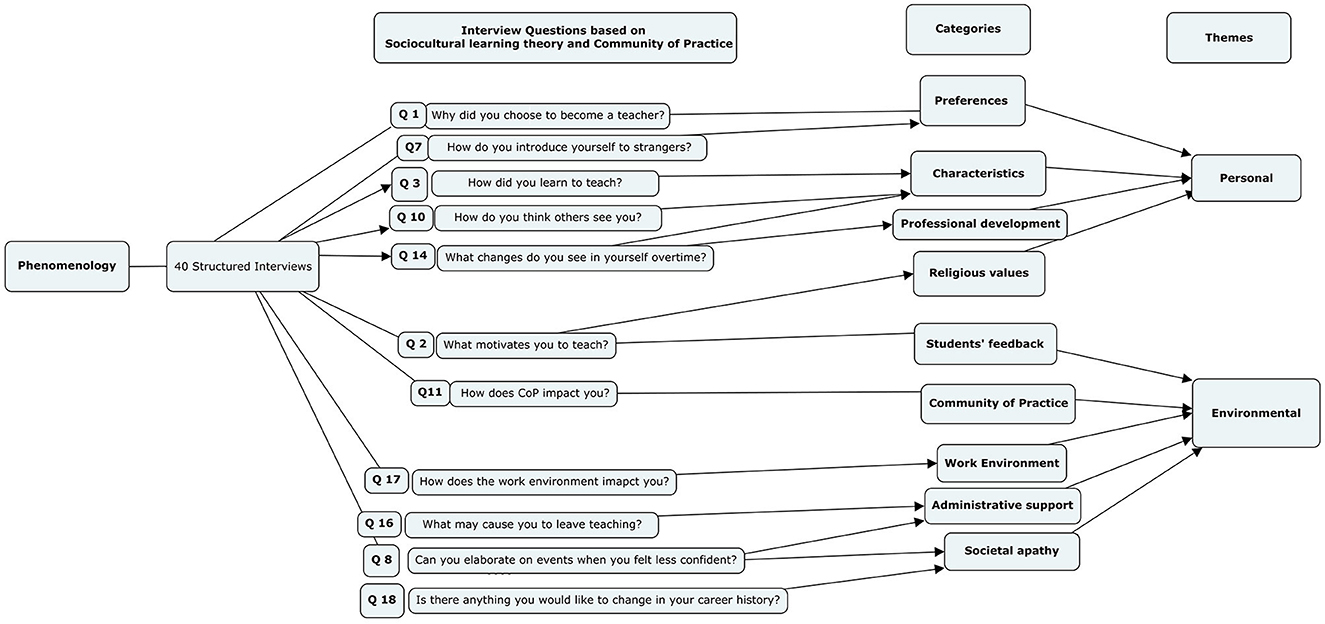

Inductive analysis of participants' reflective responses to interview questions was performed iteratively. A total of 83 codes were extracted, which were grouped into nine categories under the umbrella of two major themes: personal and environmental factors (see Figure 2). The personal factors theme comprised four categories and the environmental factors theme comprised five categories (see Table 2).

Figure 2. Factors affecting formation of professional identity of basic medical sciences teachers in Pakistan.

Identifiers for research participants

The identifiers used for the quotes of faculty members were as follows: F and M denote the gender female and male, respectively; P, AP, AsP, and L denote the faculty positions professor, assistant professor, associate professor, and lecturer, respectively; and D and M for dental and medical faculty, respectively. For example, MM1AP denotes male medical faculty 1, who is an assistant professor. The faculty requested their department name be omitted from the interview as the community of basic sciences teachers is small, making it easy for their identity to be revealed. Therefore, no identifier was used for the department.

Personal factors

I. Characteristics: Certain characteristics of the teachers are inherent and exhibit a strong aptitude for teaching. Most teachers [21 (52%)] considered teaching their “passion.” Despite low wages compared to a clinician, they were passionate about teaching [M = 5 (55%), F = 16 (40%)]. Their passion and commitment were evident from phrases such as “Once you are a teacher, it is forever. You can't leave teaching but can leave the employment of a teacher” (MF7P), “can't imagine doing anything else” (MM4AP), and “my students live in me” (DF3AsP). They perceived that they had an aptitude [M = 1 (11%), F = 4 (13%)] for this field. According to most participants, the aptitude for teaching was innate and later enhanced by observations, role models, workshops, and courses. A small number of teachers explained it as “inborn skill” (MF6L), “kinda comes naturally” (MMF13AP), and “instinctively” (MF3AP).

Most male teachers considered themselves as dynamic [M = 1(11%), F = 0], mature [M = 1 (11%), F = 0], confident [M = 1 (11%), F = 0], resourceful [M = 1 (11%), F = 0], facilitative [M = 1(11%), F = 0], humble [M = 2 (22%), F = 0], internally motivated [M = 2 (22%), F = 2 (6%)], and having a sense of purpose [M = 3 (33%), F = 2 (6%)]. By contrast, female teachers considered themselves as hardworking [M = 0, F = 5 (12%)], dedicated [M = 0, F = 3 (7%)], and having an effect on parenting [F = 5 (16%), M = 0].

II. Preferences: Despite a strong desire to engage in clinical practice, most female teachers opted the teaching profession owing to work–life balance [F = 16 (52%), M = 0] and aptitude [F = 4 (13%), M = 1 (11%)]. Some opted for the profession as they had previous experience [9 (22%), M = 3(33%), F = 6 (19%)] of teaching younger siblings or peers. Others were inspired by their teachers who were their role models [15 (37%), M = 6 (66%), F = 9 (29%)]. Most responses were as follows: “I liked the working hours and flexibility with which I can balance work and family life” (MF14AP) and “It syncs well with family life but of course at the cost of monetary affluence” (MF7P). The work–life balance is often the only motivating factor, as a teacher states, “Only motivating factors are that my evenings and weekends are spent with family” (MF26P). It is also recognized that teaching millennial learners helps the teachers in parenting their own children, as a teacher states, “my job helped me to be a better parent” (MF14AP).

On the contrary, male teachers entered the teaching profession, predominantly owing to passion [M = 5 (55%), F = 16 (52%)], experience [M = 3 (33%), F = 6 (19%)], and complacency [M = 3 (33%), F = 0] and to maintain their unique identity [M = 1 (11%), F = 0]: “There were already many individuals in the clinical fields, and I wanted to do something new that was required by the profession and beneficial to the public” (DM1AP). In addition, they did not express any intention of pursuing part-time clinical practice and expressed satisfaction about the working hours. A teacher hinted complacency as the reason for him to enter this profession: “a very relaxed life as compared to clinicians” (MM2AsP). One remarked satirically on the complacency of his few colleagues: “I've become more accepting of the reality that people being comfortable and seeking comfortable teaching careers is a human normal, and that it's very difficult to get them to change their behaviors no matter how educated they may be” (DM1AP). Only a few teachers [5 (12%)] entered this field by chance [M = 2 (22%), F = 3 (10%)].

For introducing themselves to others, only a few teachers [3 (7%)] use their designation, 12 (30%) use their name, and 22 (55%) use the prefix of doctor. A teacher stated, “I feel the use of Dr. is increasing as it softens others' attitude” (DM1AP). Most teachers [22 (55%)] view their teaching role as secondary to their primary role of a physician: “Being a doctor is my prime identity” (DF2AP); “I am proud to be a doctor” (MF19AsP). Although a few [4 (11%)] were interested in part-time clinical practice, either institutional policy or the constraints placed by family life prevented them from pursuing it. A teacher stated her wish to “do clinics side-by-side to have that feeling of being a valuable doctor” (MF19AsP). However, a male teacher expressed, “I wonder why female doctors do not go for clinical practice. They spend whole 8 h in college and consider it compatible with their family life. I think they lack initiative and awareness; they can earn more by doing only 3-h practice in evening clinics” (DM9AP).

III. Religious values: The aspiration to leave a legacy, contribute to society, and help others (driven by religious values) influenced individuals [F = 9 (31%), M = 4 (44%)] to choose the teaching profession. The teachers who recognize the positive connections between their various intersecting roles experience professional development and job satisfaction and contribute to students' development. They are aware of the significant societal impact they hold as role models. Consequently, associate professors and professors exhibit higher levels of acceptance and contentment, as stated by a teacher: “A teacher can be an influencer. It's a snowball effect and a beautiful way of Sadqa I jaria(legacy). The biggest one is the opportunity to help the ailing community if not directly, then indirectly by teaching the future doctors” (MF7P). The transcendence is obvious among some teachers, as one teacher stated, “My passion is to do something for students that would bring a positive change in their lives” (MF28AsP). The desire to leave a legacy behind was expressed by a teacher: “I want to keep a record of all innovative strategies and compile it as a book or a chapter to make others learn” (MF19AsP). In addition to altruism, there were other noticeable traits in them. Their emotional quotient also increased over time. They were well aware of their personal transformation and believed that they had become more tolerant, confident, and patient as well as stronger spiritually. A few teachers realized that the changes in their personality brought significantly more pleasant experiences: “I have become more humble, more stable, more confident and more thankful to Allah Almighty” (MM2AsP). Another teacher stated, “I have learned how to handle stress and stay calm in stressful situations” (MF22AsP).

Despite facing challenges, the teachers were highly passionate about their job. A young woman advised her junior colleagues solemnly, “Never consider your job a burden. If it feels like one, it's time to leave” (MF15AP). A male teacher advised, “Try to improve yourself, your surroundings, and the system. Be positive and dedicated toward teaching as it's a very noble job” (DM2L).

IV. Professional growth: A few teachers struggled with tensions in their identity [3 (7%)]: “I have become more solitary” (MM2AsP). “Overcrowding of faculty seats in limited medical colleges in the city, no acknowledgment of hard work, overwork; all these factors have made me short tempered. I wish I was an insensitive person” (MF26P).

Regardless of gender, the teachers [6 (15%)] longed for higher education/PhD but were restricted by the limited opportunities available in the country. A male teacher said, “The delay in my postgraduate degree affected my career badly” (MM2AP). Another teacher complained, “Very few opportunities have been provided by the university to expose us to international studies or new methods of teaching skills” (MM5AP). A female teacher advised students the following: “Chose subject like pathology in basic sciences. This will give another employment opportunity of working in labs when you don't want to do job in a medical college” (MF26P).

Environmental factors

I. Community of Practice: When asked about the effect of CoP, most found their peers cooperative and motivating [M = 3(33%), F = 22 (55%)], whereas a few found senior faculty to be sabotaging or intimidating [M = 2 (22%), F = 3 (10%)]. A teacher communicated, “Most of us hold one another up. Some seniors are………” (MF15Ap). One teacher stated, “Mostly demotivate as they remain shut in their old ways” (MF20AsP). A younger female teacher responded, “Free hand and liberty to exercise new things is a motivation to work but red-tape culture and hierarchy-conscious bosses put me off” (MF16AP). Nevertheless, some teachers appreciated the “inspiring role models” (MM6AP) and “Motivated, brilliant, hardworking, well-qualified colleagues” (MF28L).

II. Students' feedback: Teachers thrive on feedback they receive from their students. A majority of the teachers [18 (45%)] perceived students' feedback as the respect and love of their students and as a motivation for them to continue teaching. “Whenever an older student reaches out and tell how they he been influenced by me and that changed him for good. When older students recognize immediately and tell that they loved my teaching. When I find my students successfully placed in life and progressing. That's the biggest boost” (MF7P). In most cases, feedback is the only form of reward they receive for their hard work: “Respect and honor given to me by my dear students. A smile on faces of my students when I teach them, and they get through the final examination and acknowledge my role in their success” (MF37AsP). Their efforts are acknowledged by their students: “My students acknowledge my hard work evident by excellent feedback I receive” (MF26P). They experienced a sense of accomplishment when they see their students' progress professionally: “Whenever I am able to turn around a student by encouragement and mentoring” (MF7P).

III. Administrative Support: Integrated modular curriculum practice has made learning and assessment a full-time job. One faculty member expressed as follows about the workload: “I am 40% teacher, 5% researcher, 30% administrator, 10% parent, 10% spouse, 5% recreation” (MM2AsP). Moreover, teachers prepare for their teaching sessions at their homes as well. However, the multiple roles they play are not acknowledged at their workplace [4(10%)], and they perform their job with a single-role salary; this could lead to the feeling of frustration among them. A male teacher who was passionate and motivated stated, “The low salary structure coupled with the high stress workload could force me into full time clinical work” (DM1Ap). Another teacher advised her juniors as, “If you are more inclined toward earning, then this is not the right place!” (MF12AP). Regarding the institutional leadership role, one narrative mentioned, “We have little support from institutional leadership…we're asked to do the impossible in very little time” (DM1AP). A teacher who had experience teaching in the private sector explained, “there is overcrowding of faculty seats in medical colleges. This gives an edge to private organizations. Their concern is money saving by increasing workload on faculty; not quality of teaching” (MF26P). A faculty member stated, “Delayed promotions for decades and lack of proper facilities demoralize the teachers” (MMF13AP). Although a few teachers received acknowledgment, it was not in the form of promotion or monetary gain: “When my input was featured in national curriculum” (DM1AP) and “I once received letter of appreciation for my services” (MF19AsP).

IV. Work environment: Most teachers liked the positive work environment [21 (52%)]. The factors that contributed to the positive work environment were “opportunity to add to research,” “energy and motivation from colleagues” and “interaction with younger generation,” “cooperative seniors,” “appreciation by seniors,” and “respect and love of students.” However, a few [15(37%)] recognized a negative work environment and its impact on them. The common demotivating factors that cause stress in the work environment were “no salary raise,” “no culture of acceptance or appreciation,” “no opportunities and acknowledgment,” lack of students' interest in studies.”

V. Societal apathy: Teaching is not as much appreciated in our society [4 (10%)] as clinical practice. Loyalty and dedication to family life [16 (52%)] were factors that diverted most teachers away from the clinician profession. “Public think that those who are associated with medical education are not doctors. Comparing teachers in medical institute with primary school teacher and thinking that both are at the same level so there is no use of doing this job” (MF18AP). A male teacher endorsed, “Teachers are least admired or acknowledged by our society” (MM4AP).

Discussion

Factors forming the unique professional identity of basic medical sciences teachers in Pakistan have not been previously documented. Therefore, this study attempted to determine factors that influence the development of peculiar attributes and feminization of the medical teacher profession in Pakistan. In Pakistan, female doctors face several challenges in pursuing a medical profession. Shahab et al. (2013) observed that 44% of the female medical students wished to continue medical practice and specialize, whereas 48% were uncertain about it as such a decision primarily relies on their husbands' families. In a patriarchal society like Pakistan, pursuing a teaching career may be relatively easier for a female doctor as it aligns well with their family life.

Research has found that teachers are the most prone to burnout and emotional distress due to the challenges they encounter (Ilaja and Reyes, 2016). Our study findings align with another study conducted in 2021, which concluded that teachers work under high pressure within limited times, exceeding their designated hours to meet increased work demands, handling many students, and enduring work environments with poor interpersonal relationships, job instability, and lack of resources to perform their tasks (González-Palacios et al., 2021).

A study in China concluded that numerous challenges and setbacks in teaching cause teacher attrition, demotivation, stress, and burnout, especially during the vulnerable period of the first 5 years of a job, during which 40%−50% quit their jobs (Gallant and Riley, 2014). This attrition may be due to high workload, fear of challenges, lack of time management, lack of experience and knowledge, or student behavior (Kelly et al., 2018). This finding agrees with our study results, which show that a few faculty members, despite having the passion for teaching, wanted to switch to clinical practice because of non-fulfillment of financial and self-esteem needs, multi-tasking, and workload. In addition, our research shows that family preference and religious values help teachers endure and thrive in their profession, emphasizing the significance of resilience and/or self-actualization (Taormina and Gao, 2013).

Our study results resonate with a study conducted by Wahid et al. (2021) (from Indonesia); it demonstrated that medical teachers' professional identity is positively influenced by religious beliefs and family values. However, this study differed from ours in that societal recognition was found to be a motivating factor for their faculty. Our study presented a different result because people in Pakistan, as evidenced in another study, do not generally consider the teaching profession to be highly respectable (Nadir, 2022). Many other studies conducted in different parts of the world have similarly endorsed the notion that clinicians and researchers are more valued than academicians, which results in a sense of conflict in the latter's identity (Sabel and Archer, 2014; Nadir, 2022). This disparity can be attributed to the financial influence due to which society compartmentalizes clinicians as doctors and gives them a hierarchical status, consequently considering them with respect (Sabel and Archer, 2014; Nadir, 2022). This conflict and tension in identity is called hierarchical and compartmentalized identity (van Lankveld et al., 2021).

Bandura's social learning theory provides a strong basis for understanding factors shaping the professional identity of basic medical sciences teachers (Bandura, 2001). The theory posits that people learn by observing other individuals' interaction with their living environment, i.e., people study other's behavior and cognition while engaging in reciprocal interactions with each other. In the context of teaching, teachers construct their identity not in isolation but by continuous exchanges of ideas with their colleagues. The recognition, support, and reward they receive for their role affect the formation of their identity. They evaluate and view their actions from the perspectives of the members of their own community and seek validation through the responses of society (Wong and Trollope-Kumar, 2014). To nurture teachers' identity, a recent study in Pakistan highlighted the critical role of CoP to develop favorable attributes in individuals through positive role modeling and foster an enabling institutional environment (Bashir and McTaggart, 2022). When they are given autonomy in their work and are supported by other members of their community, teachers feel “related” to their peers, their competence flourishes, and they form a merged identity with their professional peers (van Lankveld et al., 2021).

Prime contributors to the professional identity of basic medical sciences teachers include CoP [31 (77%)], passion for teaching [21 (52%)], students' feedback [18 (45%)], work–life balance [16 (40%)], and religious values [13 (32%)]. CoP considerably affects their career either by modeling or sabotaging. Though they do get motivated via positive feedback from their students 18(45%) and religious values 13(32%), they need close and supportive relationships with their colleagues for professional growth. In addition, teachers are recommended to assert control over their lives by learning coping mechanisms within their environment. Institutions can facilitate their professional growth by acknowledging their hard work and dedication, fostering an enabling environment for their growth, and institutionalizing resilience-building programs (Fullerton et al., 2021) in their training to help them cope with realities of their work (Wang, 2021). Merged and intersecting identity serve as an enabler, whereas compartmentalized and hierarchical identity hinders professional growth, job continuity, and career trajectory (Cantillon et al., 2019; van Lankveld et al., 2021). Therefore, it is not uncommon for teachers to feel demotivated when their strong influential role in society is not appreciated by society itself. However, this demotivation can be countered by providing them with an attractive salary package and opportunities for them to pursue part-time clinical practice. These measures can enhance teachers' social status and garner the acknowledgment they deserve.

Conclusion

The most critical factor affecting the formation of the professional identity of basic medical sciences teachers is their community of practice [30 (75%)]. There were more motivating and inspiring role models [25 (62%)] than negative ones [5 (12%)]. Teachers have a strong passion [21 (52%)] for teaching and contributing to society (driven by religious values) [13 (32%)], as evidenced by the strong resilience they exhibit in the face of challenges at their workplaces and society. This finding is reinforced by students' feedback [18 (45%)] and work–life balance [16 (40%)]. These characteristics can be further strengthened by designing faculty development programs containing personal narratives or guided reflective writings, resilience-building models, mentorship, and strong organizational policies favoring the professional growth of junior teachers, and acknowledgment of their efforts through rewards and incentives.

Limitations

The study aimed to obtain a panoramic view on the issue of the professional identity of basic medical sciences and identify individual subthemes that could be explored in future studies. Even though the findings were insightful, the sample size is not sufficiently large to generalize them to the whole population of basic medical sciences teachers in Pakistan. The participants were recruited from a limited number of institutions; however, conducting similar studies by including more participants from other institutions in the country can provide better data triangulation.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethical Committee of National University of Medical Sciences, Pakistan (06/IRB&EC/NUMS/02/10682). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin because answering text based interview was taken as informed consent; it is mentioned in start of interview format.

Author contributions

FK: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AJ: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SI: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. AZ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. FF: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the faculty members who participated in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 52, 1–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

Bashir, A., and McTaggart, I. J. (2022). Importance of faculty role modelling for teaching professionalism to medical students: individual versus institutional responsibility. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 17, 112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.2021.06.009

Cantillon, P., Dornan, T., and De Grave, W. (2019). Becoming a clinical teacher: identity formation in context. Acad. Med. 94, 1610–1618. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002403

Creswell, J. W., and Miller, D. L. (2000). Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Prac. 39, 124–130. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2

Cruess, R. L., Cruess, S. R., Boudreau, J. D., Snell, L., and Steinert, Y. (2014). Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Acad. Med. 89:1446–1451. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000427

Cruess, S. R., Cruess, R. L., and Steinert, Y. (2019). Supporting the development of a professional identity: general principles. Med. Teach. 41, 641–649. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1536260

Fullerton, D. J., Zhang, L. M., and Kleitman, S. (2021). An integrative process model of resilience in an academic context: RESILIENCE resources, coping strategies, and spositive adaptation. PloS ONE 16:e0246000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246000

Gallant, A., and Riley, P. (2014). Early career teacher attrition: new thoughts on an intractable problem. Teach. Dev. 18, 562–580. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2014.945129

González-Palacios, Y. L., Ceballos-Vásquez, P. A., and Rivera-Rojas, F. (2021). Mental workload in faculty and consequences in their health: an integrative review. Braz. J. Occup. 29:e2808. doi: 10.1590/2526-8910.ctoar21232808

Guraya, S. Y., and Chen, S. (2019). The impact and effectiveness of faculty development program in fostering the faculty's knowledge, skills, and professional competence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 26, 688–697. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2017.10.024

Ibarra, H., and Barbulescu, R. (2010). Identity as narrative: prevalence, effectiveness, and consequences of narrative identity work in macro work role transitions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 35, 135–154. doi: 10.5465/AMR.2010.45577925

Ilaja, B., and Reyes, C. (2016). Burnout, and emotional intelligence in university professors: implications for occupational health. Psicologia Desde el Caribe. 33, 31–46. doi: 10.14482/psdc.33.1.8081

Kelly, N., Sim, C., and Ireland, M. (2018). Slipping through the cracks: teachers who miss out on early career support. Asia Pacif. J. Teach. Educ. 46, 292–316. doi: 10.1080/1359866X.2018.1441366

Merriam, S. B., and Tisdell, E. J. (2015). Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

Merton, R. K., and Reader, G. (1957). The Student Physician: Introductory Studies in the Sociology of Medical Education. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

Moazam, F., and Shekhani, S. (2018). Why women go to medical college but fail to practice medicine: perspectives from the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. Med. Educ. 2018, 1–11. doi: 10.1111/medu.13545

Nadir, M. N. (2022). Tackling Disrespect. Available online at: https://www.dawn.com/news/1692562/tackling-disrespect (accessed December 13, 2022).

Olmos-Vega, F. M., Stalmeijer, R. E., Varpio, L., and Kahlke, R. (2022). A. practical guide to reflexivity in qualitative research: AMEE guide no. 149. Med Teach. 7, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2022.2057287

Orsmond, P., McMillan, H., and Zvauya, R. (2022). It's how we practice that matters: professional identity formation and legitimate peripheral participation in medical students: a qualitative study. BMC Med. Educ. 22, 1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03107-1

Ryan, A., Hickey, A., Harkin, D. W., Boland, F., Collins, M. E., Doyle, F., et al. (2022). Professional identity formation, professionalism, leadership and resilience (PILLAR) in medical students: methodology and early results. Res. Sq. 2022, e1–e11. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-1527305/v1

Saarijärvi, M., and Bratt, E. L. (2021). When face-to-face interviews are not possible: tips and tricks for video, telephone, online chat, and email interviews in qualitative research. Eur. J. Cardiovas. Nurs. 20, 392–396. doi: 10.1093/eurjcn/zvab038

Sabel, E., and Archer, J. (2014). Medical education is the ugly duckling of the medical world” and other challenges to medical educators' identity construction: a qualitative study. Acad. Med. 89, 1474–1480. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000420

Sarraf-Yazdi, S., Teo, Y. N., How, A. E., Teo, Y. H., Goh, S., Kow, C. S., et al. (2021). A scoping review of professional identity formation in undergraduate medical education. J. Gen. Int. Med. 36, 3511–3521. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07024-9

Shahab, F., Hussain, H., Inayat, A., and Shahab, A. (2013). Attitudes of medical students towards their career—perspective from Khyber-Pukhtunkhwa. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 36:27.

Steinert, Y. (2014). “Faculty development: core concepts and principles,” in Faculty Development in the Health Professions: A Focus on Research and Practice, ed. Y. Steiner (Dordrecht: Springer Science+ Business Media), 3–25.

Steinert, Y., O'Sullivan, P., and Irby, D. M. (2019). Strengthening teachers' professional identities through faculty development. Acad. Med. 94, 963–968. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002695

Taormina, R. J., and Gao, J. H. (2013). Maslow and the motivation hierarchy: Measuring satisfaction of the needs. Am. J. Psychol. 126, 155–177. doi: 10.5406/amerjpsyc.126.2.0155

van Lankveld, T., Thampy, H., Cantillon, P., Horsburgh, J., Kluijtmans, M., et al. (2021). Supporting a teacher identity in health professions education: AMEE Guide No. 132. Med Teach. 43, 124–136. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1838463

Wahid, M. H., Findyartini, A., Soemantri, D., Mustika, R., Felaza, E., Steinert, Y., et al. (2021). Professional identity formation of medical teachers in a non-Western setting. Med. Teach. 43, 868–873. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2021.1922657

Wang, Y. (2021). Building teachers' resilience: practical applications for teacher education of China. Front. Psychol. 2021:3429. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.738606

Keywords: professional identity, medical teachers, resilience, Pakistan, community of practice, qualitative, phenomenology, students' feedback

Citation: Kiran F, Javaid A, Irum S, Zahoor A and Farooq F (2024) Factors affecting professional identity formation of basic medical sciences teachers in Pakistan: a phenomenological analysis of interviews. Front. Educ. 9:1307560. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1307560

Received: 04 October 2023; Accepted: 02 May 2024;

Published: 03 June 2024.

Edited by:

Cheryl J. Craig, Texas A&M University, United StatesReviewed by:

William Burton, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, United StatesElsa Ribeiro-Silva, University of Coimbra, Portugal

Catarina Amorim, Faculty of Sport Sciences and Physical Education, University of Coimbra, Portugal, in collaboration with reviewer ER-S

Copyright © 2024 Kiran, Javaid, Irum, Zahoor and Farooq. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Faiza Kiran, ZHJmYWl6YWtpcmFuQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†ORCID: Faiza Kiran orcid.org/0000-0001-6014-1153

‡Present address: Faiza Kiran, School of Health Professions Education, Shifa Tameer-e-Millat University, Islamabad, Pakistan

Faiza Kiran

Faiza Kiran Arshad Javaid2

Arshad Javaid2 Asiya Zahoor

Asiya Zahoor